Abstract

Mental illness is a growing global health problem affecting individuals and society. In Sweden, the number of people suffering from mental health illnesses, such as anxiety and depression, is increasing and is expected to be one of the largest public health challenges in 2030. As mental illness increases, the area also needs effective forms of treatment. This study aims to investigate if Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET) works as a treatment method for adults suffering from anxiety disorders and depression. A structured literature review based on 24 articles found in the databases PubMed, MEDLINE, CINAHL and PsycInfo. Two reviewers independently reviewed and collectively extracted data from the included articles. The articles have been analyzed by using thematic analysis. The results suggest that Virtual reality exposure therapy can work as an effective treatment method for adults with anxiety disorders. It also indicates that VRET may act as a health-promoting intervention to reduce anxiety disorders, phobias, and depression symptoms. Virtual reality exposure therapy can be an effective treatment method and health-promoting effort against anxiety disorders in adults. An essential factor for the patients who accept VRET as a treatment is the initial information therapists give.

Introduction

Mental illness is a growing problem today. According to the Public Health Agency of Sweden (Public Health Agency [FoHM], Citation2022), about 14 percent of the Swedish population between the ages of 16 and 84 rated their mental well-being as poor in the National Public Health Survey of 2020. The concept of mental illness is broad and includes many different conditions of varying severity for those affected. Milder mental illness can, for example, be worried or anxiety with a low impact on the sufferer, while severe mental illness can, for example, involve schizophrenia with a significant effect on the individual’s functional level (Jacobsen, Citation2019; Patel et al., Citation2018). The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare reported that mental illness had become a public health problem during the Covid-19 pandemic due to many individuals becoming more isolated from the outside world (National Board of Health and Welfare, Citation2021a).

Virtual reality (VR)-based technology allows the user to enter a three-dimensional, interactive environment where psychotherapeutic treatment can be carried out. At the same time, healthcare professionals can monitor and evaluate the patient’s condition. For example, VR-based therapy as Virtual reality exposure therapy (VRET) has become increasingly common in health care, which can be used to reduce stress reactions a patient may experience due to traumatic experiences, relieve depression, anxiety, and feelings of loneliness, and to improve general well-being (Soltani, Citation2019; Swedish eHealth Agency, Citation2020). VRET can also help patients overcome their phobias or treat Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and depression (Emmelkamp & Meyerbröker, Citation2021; Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services [SBU], Citation2021). VR technology allows the patient to experience what scares them, triggers panic feelings or anxiety via a computer-generated three-dimensional and interactive environment where the intensity of the exposure can be controlled and where a therapist can guide the patient through the treatment (Wood et al., Citation2009).

As mental illness risks increase, effective treatment methods will also increase. Although VRET is a relatively new method, there is today a demonstration of good results in treating mental illnesses such as anxiety disorders. However, this method is not used to the extent that it could be used, which may be due to one or more circumstances often based on a lack of knowledge about treatment methods and VR technology itself (Boeldt et al., Citation2019; Linder et al., Citation2018).

Virtual reality-based therapy

VRET is a modern form of exposure therapy that uses digital technology to create a VR environment in which the patient can implement a form of traditional exposure therapy artificially. It becomes a way to experience something physiologically and emotionally that creates stress in a completely individualized and safe environment, where its intensity can gradually increase during the treatment. This is often easier for the patient to accept than to experience stressful moments in real life (Boeldt et al., Citation2019; Emmelkamp & Meyerbröker, Citation2021).

To recreate the VR experience, a headset with an integrated monitor is used, or a room with screens where the experiences that the person treated as traumatic is reproduced visually. It is also possible to produce experiences by treating other sensory organs through smell, sound, and vibrations to make the experience even more realistic (Wood et al., Citation2009). During the exposure, a natural reaction is created in the treated person where they want to escape and avoid the stimuli of the stress reaction. Over time, repeated exposure with increased intensity will reduce the perceived stress reactions, as they become increasingly manageable.

A disadvantage of exposure to VRET is that these exposures can cause dizziness and headaches, usually called cyber-sickness symptoms, which look like motion sickness (Reger et al., Citation2019; Stetz et al., Citation2011). In addition, however, VRET software development is extensive, and VR units are today easily accessible at a relatively low price, which means that once a treatment program has been developed, the treatment can be made available to many patients at a relatively low cost (Buna et al., Citation2016; Emmelkamp et al., Citation2020).

Treatment of anxiety disorders and syndromes has been shown to work well through VRET. In some cases, there are benefits to using the method instead of, or in combination with, conventional treatment methods. This applies, for example, to social anxiety, which is often treated with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) by exposing the patient to the stimuli that give rise to anxiety while eliminating the natural defense mechanisms so that the patient learns that the feared negative consequences are unlikely to occur. But due to the nature of the disorder, it is difficult to find real-life situations where this exposure can be carried out, and it is also difficult to construct or stage these situations. In these cases, the exposure in the VRET treatment functions as a substitute for exposure in real life (Emmelkamp et al., Citation2020).

Theoretical acceptance of digital treatment methods

Studies show openness to treatment technology gives better results from the state of therapy used (Kothgassner et al., Citation2019). For VRET to function as a treatment method for adults diagnosed with some type of anxiety disorder, some factors affect whether the treatment method will be accepted by the person being treated. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) examines generally the factors that influence whether a computer system will be accepted by potential users and the perceived usability (assessment of whether the digital health system is used as intended) and user-friendliness (perception of user-friendliness of VR software/intervention by healthcare professionals and/or patient) (Boeldt et al., Citation2019; European Commission, Citation2019). If a patient is less digitally familiar, this can affect their attitude toward digital tools and then possibly also toward digital care interventions (FoHM, Citation2018). In this context, healthcare professionals have an essential role in explaining and convincing patients of the benefits and potential of the intervention. The theory can function as an explanatory theory to, for example, description of how the care staff’s experiences are within VRET’s usability and user-friendliness.

According to the TAM theory, several factors or barriers can effect the care recipient’s attitude to care interventions, and subsequently, their intention and use of the care intervention. The first factor to mention comprises the patient’s fears and misconceptions of prolonged exposure therapy and its consequences like cybersickness, which can increase the refusal or drop out (Boeldt et al., Citation2019). Secondly, general practical issues can influence the arrangement of exposure therapy in different clinical settings, such as limited time and the logistics for planning the therapy, therapists’ own anxiety and distress related to using exposure-based interventions and lack of dissemination of exposure therapy (Pittig et al., Citation2019). Thirdly, the concerns about exposure-based therapy found among therapists can be distressing for both the therapist and patient, increasing the risk of worsening the patient’s anxiety. A fourth factor is that only a limited number of mental healthcare professionals are clinically and formally trained in this kind of therapy and may have individual barriers to the use of it. Also, mental health providers may be reluctant to the use the latest evidence-based interventions due to individual negative attitudes (Botella et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, confidentiality risks for patients, accessibility and controllability of the stimuli, privacy, and ethical concerns may also exist (Ma et al., Citation2021; Maples-Keller et al., Citation2017).

Anxiety disorders

Anxiety is a natural reaction to something scaring us, where the response can be crucial to the individual’s survival. The brain sends signals to the body via the nervous system to prepare for fight or flight. Consequently, the body sends various stress hormones into the blood, creating several bodily reactions such as increased heart and respiratory rates (Sjöström & Skärsäter, Citation2014).

Anxiety disorders are relatively common today; as many as one in three women and one in five men are affected at some point in their lives (Patel et al., Citation2018), including several diseases and syndromes such as social anxiety, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Anxiety caused by stress is usually temporary and transient, unlike anxiety disorders, which can become chronic if left untreated. Symptoms can vary depending on the diagnosis and the victim’s characteristics, which might be decisive for the treatment methods (Jacobsen, Citation2019; Patel et al., Citation2013).

Traditional treatment methods that have been empirically proven to work are CBT and psychotherapy, where both methods are adapted to the current type of disease. Patients can also receive psychotropic medicine (Patel et al., Citation2013).

Relevance of the study

Mental illness is a growing global public health problem affecting individuals and society (WHO, Citation2022). In Sweden, the number of people with mental illness is increasing, and the area will be one of the biggest public health challenges in 2030 (FoHM, Citation2022). Approximately one in eight people yearly suffer from a depressive illness, anxiety disorder, or other diagnosable mental disorder. Nevertheless, about 71 percent lack access to effective treatment; at the same time as, mental illness is not given sufficient attention by caregivers (Jacobsen, Citation2019; Patel et al., Citation2013; WHO, Citation2022). From an economic perspective, the total costs of mental health problems are estimated at more than 4% of GDP (more than €600 billion) across the 27 EU countries and the United Kingdom annually (European Commission, Citation2018). At the same time, as mental illness is increasing, the demands are growing that the treatments offered are cost-effective and have a good effect on those treated.

Studies show that VRET can work as well as conventional treatment methods in the treatment of anxiety disorders such as PTSD (Kothgassner et al., Citation2016) and social anxiety, which may be since VRET is similar to traditional exposure treatments and is based on the same principle (Emmelkamp et al., Citation2020). For practical reasons, the implementation of the exposure can also be more straightforward via VRET compared with in vivo exposure because, for example, social situations can be challenging to find or recreate (Emmelkamp et al., Citation2020). Studies also show that patient compliance has increased with VRET, which can positively affect how the patient responds to the treatment (Garcia-Palacios et al., Citation2007). This study aims to investigate whether Virtual Reality Exposure therapy (VRET) can be used as a treatment method for adults with anxiety disorders and depression.

Materials and methods

Study design

This is a structured literature review of the published literature, which is defined as one method for performing a structured comprehensive collection of literature which systematically extracts data and via a content or thematic analysis enables discovery of themes, patterns, trends or gaps. The findings result in implications for future research (Rocco et al., Citation2023). It was carried out from April 12, 2022, to April 24, 2022, through the following databases: PubMed, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and MEDLINE, using two research questions;

[RQ1]- Is VRET more effective in treating anxiety disorders and depression than other treatment methods?

[RQ2]- Based on the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), what factors influence patients’ perceptions of VRET’s usability and user-friendliness?

Search strategy

A systematic literature search using the databases of PubMed, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and MEDLINE was conducted from 12 April to 24 April 2022 to identify the most relevant articles which meet the aim and study questions. Additionally, we searched the references of the articles included in our review to identify other pertinent articles that may have been missed. Two independent reviewers (O.H. and J.L.) conducted all the database searches, and any discrepancies were resolved via discussions to obtain consensus, when disagreement was present, the third supervising reviewer (S.S.) was consulted.

We used the Boolean terms “AND” and “OR” to expand and restrict the search spectrum of search conditions. The search terms for each database were: Virtual reality exposure therapy* AND Anxiety disorder; Virtual reality exposure therapy* AND Depression; Virtual reality exposure therapy AND social phobia; Virtual reality exposure therapy AND social anxiety; (Mental health or mental illness or mental disorder or psychiatric illness) AND (virtual reality exposure therapy or VR or virtual reality therapy) AND (adults or adult); virtual reality exposure therapy AND (mental health or mental illness or mental disorder or psychiatric) AND (adults or adult). The initial literature search yielded 783 prospective articles.

Databases were searched for article titles and abstracts; these were then screened, and the full text articles read. A shared DropboxTM was created to bring together all relevant records. Search results were exported into a detailed table shared with Google Docs, where the reviewers could identify duplicates to ensure that both were abstracting the same information, followed by in-person discussions to ensure that the most appropriate variables were identified, and any disagreements could be resolved through ongoing debate.

Selection criteria

Studies of any design that used VRET to promote or treat anxiety disorders and depression were included in the review if; (i) were published in a peer-reviewed journal; (ii) were written in English and carried out any time between 2010 and 2022; (iii) were original articles published in a scientific journal and presented empirical data; (iv) articles included adults participants (aged: 19+ years) diagnosed with any type of anxiety disorders and depression.

Articles were excluded when they were; (i) published in other languages other than English; (ii) were published in languages other than English before 2010; (iii) all types of reviews which did not present original data were excluded; (iv) journal papers that lack ethical considerations were excluded; (v) dissertations, conference proceedings, and other grey literature or unpublished search were excluded.

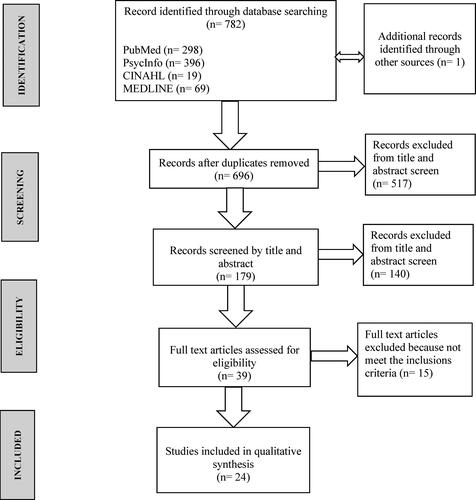

: displays a flow chart of the study search and selection process. The articles’ selection process was conducted in two stages by two independent reviewers; (a) reading the titles and abstracts by both reviewers individually, (b) reading the full-text articles, and the selection performed collectively by both reviewers in agreement. The primary search resulted in 783 records that were properly identified. To finalize the list of eligible articles, 517 papers were screened and excluded according to our pre-defined exclusion criteria after excluding duplicates to reach 179. Of the list of 179 articles, an additional 140 were excluded, resulting in 39 articles that were selected for full-text review. A final 24 articles were deemed suitable for a full review.

Data extraction

A Microsoft Word file shared on Google Docs was created for data extraction. Data was extracted from each article and presented in a summarized table with a brief description of each article (). The data was appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist (CASP, Citation2018).

Table 1. Summary of characteristics of the included studies.

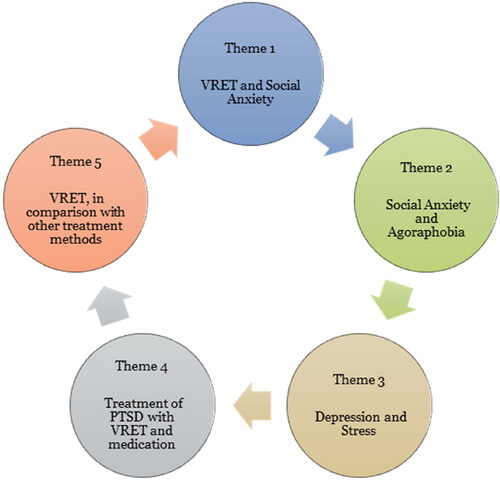

All the included publications were analyzed and categorized into different themes using the thematic analysis according to Braun & Clarke (Citation2006) model. The analysis of the research articles was done in six steps to identify and analyze the most relevant themes ().

Quality assessment

Quality ratings of the 24 studies included were carried out by the two reviewers (O.H. and J.L.), using the quality assessment tool CASP for quantitative studies, which is a tool to check the quality, reliability, and credibility of included articles (CASP, Citation2018). UlrichswebTM was used to check whether these included articles have been peer-reviewed by the experts. Both authors assessed the articles for methodological quality and ethical consideration, in a consultation with the third author (S.S.).

Ethical considerations

In a literature study based on secondary data, the ethical aspects are not directly affected because no sensitive data such as personal data were collected. However, the articles in this review were included if they were ethically approved; this means that included studies must have applied ethical considerations as prescribed in the Declaration of Helsinki and have been approved by an ethics review board.

Results

VRET as a health-promoting initiative against social anxiety

VRET is designed to put patients with social anxiety in social anxiety-provoking situations. Patients with social anxiety often have difficulty in speaking in front of a group of people, for example, to which they are exposed through virtual conversations with several individuals who act negatively (Morina et al., Citation2015). Kishimoto and Ding (Citation2019) have studied the heart rate of patients who talk to virtual individuals who act negatively while the patient speaks in front of a virtual group of people. The patient’s heart rate was examined in a group with social anxiety and in a group that was not led by any social anxiety. The study showed that the group suffering from social anxiety reported higher levels of subjective anxiety than those not suffering from social anxiety. The differences between the groups were more significantly measured with a mild negative response than an intensive negative response. This means that people suffering from social anxiety tend to have a higher heart rate even with gentle social contact than people without social anxiety. The higher heart rate in these cases may indicate a higher perceived stress level in the patient. According to Morina et al. (Citation2015) and Zainal et al. (Citation2021), there are marked differences regarding perceived social anxiety between groups treated with VRET compared with those waiting for treatment too. In these studies, VRET is thus shown to reduce social anxiety symptoms.

Morina et al. (Citation2015) describe that VR technology that contains social interactions can be used for therapeutic purposes, which is also mentioned by Anderson et al. (Citation2013) and Price et al. (Citation2011). When treating social anxiety with VRET, the treatment results were decreased anxiety symptoms, lasting at follow-up after 6 and 12 months. This shows that VRET has a sustained effect even after the end of treatment (Anderson et al., Citation2013; Price et al., Citation2011; Zainal et al., Citation2021). Price et al. (Citation2011) also highlight that patients’ commitment and presence can make treatment with VRET work better. With the proper knowledge, patients can get involved in the treatment. For example, professionals can explain to the patient what will be possible and what the expected result would be. This could make VRET act as a health-promoting measure and treatment method for social anxiety, and that can be used in healthcare to reduce symptoms of social anxiety (Zhang et al., Citation2020).

Covid-19 has caused social anxiety, fear of pandemics, and isolation in many individuals; with the help of VRET, the cognitive components can be improved, and the negative cognitions can be reduced by improving memory (Zhang et al., Citation2020). According to Zhang et al. (Citation2020), VRET can function by modifying the patient’s memory (cognitively), which after treatment allows patients to remember in more detail what happens during a pandemic, and also reduces the level of fear. Zhang et al. (Citation2020) point out that this could provide the patient with reducing anxiety on exposure to news such as the pandemic or the spread of Covid-19. The advantage of VR-based exposure therapy is that it allows the patient to experience their fear in a controlled way.

Zainal et al. (Citation2021) investigated self-guided VRET without using other therapies such as CBT to isolate the effects of VRET treatment. The study showed that the self-guided VRET treatment caused a reduction in social anxiety symptoms in contrast to the participants in the control group, who were on the waiting list (WL). Based on the self-reporting of those participants, the reduction of symptoms through the VRET treatment lasted at 3- and 6-months follow-up.

Treatment of social anxiety and agoraphobia

Social anxiety and agoraphobia are treated the same way with VRET according to the current symptoms, which are usually panic attacks based on phobias. Several studies have treated patients with VRET for panic attacks due to social anxiety and agoraphobia (Levy et al., Citation2016; Malbos et al., Citation2013; Pitti et al., Citation2015). Experiences of social anxiety and panic attacks in agoraphobia decreased after treatment with VRET. The treatment’s effect on reduced symptoms lasted at follow-up, 6 months after the end of treatment (Gebara et al., Citation2016). In VRET treatment for phobias, patients are exposed to what gives rise to feelings of panic through exposure, while a therapist guides the patient through therapy sessions. In the VRET treatment of agoraphobia, patients are exposed to virtual exposure in the form of being placed in a virtual town square with an increasing population (Levy et al., Citation2016; Malbos et al., Citation2013; Pitti et al., Citation2015). According to Levy et al. (Citation2016), this form of treatment is both cost-effective and time-efficient in comparison with in vivo exposure, because the sessions take place on-site, without the patient having to be exposed to their actual phobia, which reduces the risk of a panic attack and thus failed treatment session. Pitti et al. (Citation2015) and Malbos et al. (Citation2013) describe that VRET has a decreasing effect on symptoms of agoraphobia. Exposing patients to a virtual environment makes it easier to handle the amount of exposure given during treatment, for example, the number of people in the square, which cannot be controlled during in vivo exposure; this makes VRET an effective treatment method for phobias as both Malbos et al. (Citation2013) and Pitti et al. (Citation2015) mentioned.

Among other things, Levy et al. (Citation2016) investigated the treatment of phobias. They described that VRET has functioned as a valuable and effective treatment method for both social anxiety and specific phobias such as acrophobia (fear of heights). Moreover, the patients treated with VRET experienced less anxiety during the treatment; besides, these effects last even after the treatment’s end.

Depression and stress

Hartanto et al. (Citation2014) examined stress levels through heart rate during virtual social exposure for patients with social anxiety. They concluded that virtual social exposure could control and improve social stress and anxiety. Social conversations and verbal communication integrated into the virtual environment can be necessary for the treated person’s stress management and response to negative stressors.

Kampmann et al. (Citation2016) conducted a study to compare the treatment of social anxiety through traditional physical exposure therapy (called in vivo exposure therapy- iVET), VRET, and a comparison group that was listed on a WL and did not receive any treatment. The therapy through VRET was to put patients in different social situations where they would speak in front of other people. The results showed that both exposure therapies reduced the patients’ perceived stress level, which could affect the patient’s general anxiety symptoms, and even be sustained at the follow-up.

A study conducted by Geraets et al. (Citation2019) investigated the feasibility and effect of VR exposure on patients diagnosed with severe social anxiety, who were exposed to different social environments, and allowed to move in these virtual environments under the therapist’s guidance. The study showed that the participants experienced improvements in their social anxiety and overall quality of life after treatment with VR-based CBT (VR-CBT); the results were consistent at follow-up, and patients indicated that their depressive symptoms decreased after treatment. Zainal et al. (Citation2021) studied patients diagnosed with severe social anxiety. They were divided into two groups: one group treated with virtual reality exposure (VRE, in the form of job interviews) to reduce depressive symptoms and social anxiety and a comparison group listed on a WL. The results showed that the VRET treatment helped reduce the depressive symptoms among participants, which lasted 3 and 6 months at the follow-up.

Peskin et al. (Citation2019) investigated the relationship between PTSD and depressive symptoms in people who developed PTSD following the World Trade Center attack on September 11, 2001. Participants were divided into two groups: one was treated with VRE and D-cycloserine (VRE-DCS), and the other one was treated with VRE-placebo. The results showed an association between PTSD and depressive symptoms. During and after treatment, both depressive and PTSD symptoms decreased in both groups. However, the VRE-DCS therapy was slightly more effective than the VRE- placebo therapy. McLay et al. (Citation2014) studied changes in self-reported symptoms of combat-related PTSD, depression, and anxiety before and after treatment with VR graded exposure therapy (VR-GET) and the neuropsychological function. The study showed a significant reduction in PTSD symptoms during treatment with VRE and significant improvements in neuropsychological function. However, these improvements did not correlate with reduced depressive symptoms.

Treatment of PTSD with VRET

People who have participated in combat are often at high risk of developing PTSD, and because of the trauma they may be exposed to, they are also often in need of effective treatment (Beidel et al., Citation2019; McLay et al., Citation2017; Reger et al., Citation2016). Several studies have examined the treatment of PTSD with VRET, and the results show that the symptoms of PTSD decreased after completed treatment (McLay et al., Citation2017; Reger et al., Citation2016). In the study conducted by Reger et al. (Citation2016) the results were followed up 3 and 6 months after the end of treatment with consistent positive results for the patients in both follow-ups.

Beidel et al. (Citation2019) investigated differences in PTSD symptoms during treatment with VRET and VRET together with TMT (trauma management treatment). The participants underwent group therapy to manage the experiences they had been traumatized by. The results showed that both groups significantly reduced existing PTSD symptoms, which were permanent at follow-up, after 3 and 6 months. The group that received TMT treatment also showed a significant reduction in social isolation and this was not found among the patients in the group that only received VRET.

A study by Norr et al. (Citation2018) showed that patients who were predicted to have a more significant reduction in PTSD symptoms with VRE were probably younger, did not take antidepressant medication, and had more significant PTSD hyperarousal symptoms. Those patients had a higher risk of suicide. The study’s results suggested that treatment matching based on patient profiles performed meaningfully can improve treatment effectiveness for combat-related PTSD. Norr et al. (Citation2018) also express that future research may build on these results to understand how improvement can occur in treatment matching for PTSD.

Treatment of PTSD with VRET and medication

Rothbaum et al. (Citation2014) described that PTSD symptoms improved significantly from before to after treatment with a six-session VRET therapy and were maintained at both 3-, 6-, and 12-months follow-up for all groups studied. Several combinations have been made in treating PTSD together with different types of medication (D-cycloserine, alprazolam, dexamethasone or other benzodiazepines), which Rothbaum et al. (Citation2014) described as being effective for treating PTSD symptoms compared to VRET treatment alone. Norrholm et al. (Citation2016) and Difede et al. (Citation2014) explain in their studies that VRET combined with D-cycloserine had the best effect on reducing the symptoms of PTSD. VRET and VRET combined with Alprazolam also significantly reduced symptoms compared with the placebo group. Difede et al. (Citation2014) also describe those patients in the VRET drug group showed earlier and more significant improvement in PTSD symptoms compared to the VRET placebo group. This may indicate that the combination of VRET and medication can work as an effective treatment method for PTSD. However, the combination of VRET and dexamethasone showed that patients experienced increased PTSD symptoms during treatment (Maples-Keller et al., Citation2019); even when combined with VRET and benzodiazepine, Rothbaum et al. (Citation2014) state that treatment may diminish recovery from anxiety in secondary analyses and that D-cycloserine for PTSD patients may reduce cortisol and startle reactivity compared with alprazolam and placebo treatment.

VRET, in comparison with other treatment methods

In several studies, VRET has been compared with another form of treatment and often also against a control group with patients who have been placed on a WL and do not receive any treatment for PTSD. Reger et al. (Citation2016) studied the effectiveness of VRET and PE (prolonged exposure) among active soldiers in the United States diagnosed with PTSD. The patients were randomly divided into the VRET, PE, and WL groups. The patients who were part of VRET or PE received 10 sessions of each treatment. Reger et al. (Citation2016) describe that the symptoms of PTSD decrease with both VRET and PE treatment compared with the group of patients on a WL. Most patients in the groups VRET and PE showed a reduction in PTSD symptoms compared to the patients on the WL; these results were consistent for both groups at control after 3 and 6 months. When comparing these two groups that received treatment, the reduction in PTSD was slightly more significant for the PE group. McLay et al. (Citation2017) mentioned that PTSD symptoms improved through treatment with VRET and CET (control exposure therapy) but on the other hand, did not show any statistically significant differences between the groups.

Kampmann et al. (Citation2016), in their study, compared VRET with iVET for the treatment of social anxiety compared to a group on a WL; the results showed that iVET was better than VRET in terms of reduction of social anxiety symptoms, and the consequences for both treatments were consistent at follow-up after treatment. The patients in the group treated with iVET also reported a reduction in fear of negative evaluation, depression, and improved quality of life compared with the WL.

A study by Bouchard et al. (Citation2018) compared treatments of patients with a social anxiety disorder (SAD). They were randomly divided into three groups, VRET, in vivo, and a WL control group. All patients received individual CBT treatment consisting of 14 sessions per week. The results were assessed through a questionnaire (primary) and a behavioral avoidance test (secondary). The results showed that symptoms of social anxiety decreased more for the patients who received VRET than in vivo compared with the WL for both primary and secondary outcome measures. These results were consistent even at follow-up after 6 months. The study also states that VR is significantly more practical for therapists than in vivo exposure.

The result of Anderson et al. (Citation2013); Price et al. (Citation2011), and Zhang et al. (Citation2020) showed that treatment with VRET has a health-promoting and preventive effect in comparison with iVET for the treatment of social anxiety and effects lasting at follow-up after 6 and 12 months. The studies also showed that symptoms of social and general anxiety symptoms were reduced through treatment with VRET.

Discussion

VRET as a health-promoting measure against social anxiety

According to Anderson et al. (Citation2013), Price et al. (Citation2011), and Zainal et al. (Citation2021), VRET is an effective treatment for reducing social anxiety symptoms, which could therefore be applied in health care as a health-promoting initiative for patients suffering from social anxiety. To provide answers as to whether VRET as a treatment method for anxiety disorders is a health-promoting initiative in Sweden or other countries, interventions should be tried in healthcare in a more extensive test group and then implemented as a new treatment method. According to Price et al. (Citation2011), the result of VRET as a treatment method can be improved through the patient’s involvement. However, this requires that patients are aware of the treatment method and are open to digital treatment. According to Boeldt et al. (Citation2019), healthcare professionals have an essential role in demonstrating the benefits and potential of the new initiative to improve mental health. With the theoretical model TAM (Technology Acceptance Model), healthcare professionals can predict what they need to describe and explain to patients why to accept VRET as a treatment method and evaluate its usefulness and user-friendliness. According to the TAM theory, it is the patient’s understanding of VRET that constitutes a central factor that affects the care recipient’s attitude and commitment to, for example, health-promoting care interventions, which in turn affects the outcome of the intention and use of the care intervention (Boeldt et al., Citation2019; Price et al., Citation2011). Factors that could affect the perception of VRET are the preparations, as Zainal et al. (Citation2021) describe in their study; during the first meeting, the patient receives information about what they can expect to see visually and experience emotionally. In addition, the patient receives a comprehensive description of what each session will contain and what increase in stressors will occur in overall treatment sessions.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, large sections of the world’s population have been forced to isolate themselves and avoid physical contact with other people. Isolation has impacted individuals’ mental health (Public Health Agency, 2020). Zhang et al. (Citation2020) describe VRET can function as a treatment to help patients who fear pandemics in general and become infected. The study included three participants.

According to Zainal et al. (Citation2021) study on self-guided VRET, there was an advantage for VRET in reducing anxiety symptoms compared with the patients in the group placed on a WL, and these results lasted after the end of treatment. This self-guided exposure therapy method could relieve therapists’ work as self-guided exposure is more time-efficient and does not require a therapist present compared to both in vivo and CBT. A self-guided exposure therapy session could also be conducted at home with the help of VR and written or recorded instructions from a therapist (Bentz et al., Citation2021).

Social anxiety and agoraphobia

The studies that treated social anxiety and phobias with VRET have significantly reduced anxiety symptoms and fear. All the included studies that treated phobias showed statistically significant improvements in panic symptoms when the patient was treated with VRET. These also point out that phobias are the primary area of use for VRET treatment, which is better in comparison with, for example, depression (Levy et al., Citation2016; Malbos et al., Citation2013; Pitti et al., Citation2015).

The results in this theme show that VRET is well-functioning as a treatment method for agoraphobia and other phobias. However, this is not surprising given that these diseases are traditionally treated with exposure therapy (Pitti et al., Citation2015). Stimuli for fear and panic in phobias are often quite apparent, e.g., crowds in agoraphobia or being at high places in acrophobia. Phobias make it possible to recreate a stimulus in a virtual environment and thus also likely to carry out a virtual exposure treatment with the patient. Therefore, it is perhaps not surprising that phobias are the most explored area using VRET as a treatment method (Pitti et al., Citation2015). The same logic also includes exposure therapy for social anxiety; in several studies, different social situations are recreated, creating stress reactions in the treatment. Upon exposure, many patients showed the same responses as they had shown in an actual social situation (Kishimoto & Ding, Citation2019; Zainal et al., Citation2021), which showed that VR technology has succeeded in recreating the anxiety-triggering factor (corresponding stimuli) in a realistic way.

From the perspective of TAM, the theoretical basis for this review, healthcare professionals and therapists have an essential role in informing the patient about what will happen during the treatment session and what exposure will take place. This information can be an influencing factor with a positive impact on the patient’s perception of the treatment method, as patients with social anxiety often tend to avoid the stimuli that give rise to fear and anxiety. It is reasonable to assume that part of the avoidant behavior is also based on uncertainty resulting from the patient feeling that they cannot control the situation. If the patient becomes aware of what they will be faced with and that they could handle the problem through the therapist and interrupt the session, the number of canceled or interrupted sessions may be reduced. In the long run, this can lead to perfect treatments, and patients would have better mental health (Boeldt et al., Citation2019).

Depression and stress

The results of some of the included articles showed that VRET is a treatment that can work to reduce stress in treated patients (Hartanto et al., Citation2014; Kampmann et al., Citation2016). It should be noted that stress is measured in different ways in the current articles and that stress has not always been what was primarily investigated. In Hartanto et al. (Citation2014), stress was one of the primary study areas with social anxiety; and was measured as increased heart rate during exposure therapy. Kampmann et al. (Citation2016) did not investigate stress as a variable but instead examined the impact of VRET, in vivo and WL control group on symptoms of social anxiety. Stress was measured in this study as the patient’s subjective experience of stress level. Since stress was measured in different ways, where one is an objective measurement of the heart rate and the other is a personal estimate of the self-perceived stress level, it can be challenging to compare these results and draw general conclusions from the impact.

In some of the articles included in this study, the results showed that virtual reality exposure (VRE) could help reduce depressive symptoms in the patients treated (Geraets et al., Citation2019; Peskin et al., Citation2019; Zainal et al., Citation2021). Of the studies, only one had depression as one of the primary study areas, and the conditions for VRE treatment have also been different in the different studies. Zainal et al. (Citation2021) did not examine depression, but how VRE could affect symptoms of social anxiety. Reduced depressive symptoms were a secondary effect measured by a self-assessment model. In the study conducted by Peskin et al. (Citation2019), depression was a primary area of investigation as the purpose was to investigate whether there was a relationship between PTSD and depressive symptoms during VRET treatment. In connection with the VRET treatment, a study group received psychotropic medicine and a group placebo, and both groups were then compared with a group on a WL. Also, in this study, depression was measured through a self-assessment model. Geraets et al. (Citation2019) did not have depression as a primary research area, and his study aimed to compare treatment results with VRE, in vivo, and the WL for symptoms of social anxiety. In this study, depression was a secondary study area measured by self-assessment without any interpretive model. When comparing the results, it is essential to point out that the measures of depression are subjective assessments of one’s mental state and that, where applicable, different models have been used for this. When comparing the results of Peskin et al. (Citation2019) with other studies, it is also important to point out that psychotropic medicine was used in the VRET treatment for one of the groups examined (VRE-DCS). This group showed a more significant reduction in depressive symptoms than the placebo group, indicating that psychotropic medicine strengthens VRET treatment.

In several studies that show that VRET reduces depression, depression has not been the primary area of investigation nor the primary goal of treatment. In these studies, it can be assumed that the reduced depressive symptoms come from a reduction of another disease or symptoms. Unlike the treatment of social or specific phobias where stimuli are often explicit, it can be challenging to point out the root of depression directly; for this reason, it can also be assumed that it is challenging to create a general VRET treatment to treat depression.

Different treatments for PTSD with VRET

PTSD is one of the more investigated disorders during treatment with VRET, and several studies included in this reviews show that symptoms of PTSD decrease during treatment with VRET (Beidel et al., Citation2019; McLay et al., Citation2017; Reger et al., Citation2016). The results show that the reduction of PTSD symptoms was also permanent at follow-up. In some studies, VRET’s effectiveness was compared with other treatments; PE (Reger et al., Citation2016) and CET -control exposure therapy (McLay et al., Citation2017). In these cases, the differences were minor regarding reduced symptoms of PTSD, which means that none of the treatments can be emphasized before. However, the study conducted by Beidel et al. (Citation2019) shows that a supplement with additional treatment in the form of group therapy to manage trauma (TMT) can help patients with other mental barriers. Besides, social isolation decreased among the patients who received TMT and VRET but not those who received VRET alone. Social isolation can cause depression and worsen mental illness, making it desirable to work with this additional treatment to reduce social isolation (National Board of Health and Welfare, Citation2021b).

Several studies that examined combat-related PTSD showed relatively large dropouts from the VRET groups (Beidel et al., Citation2019; McLay et al., Citation2017; Reger et al., Citation2016). The reason for the defections was not stated in the discussion, and it is, therefore, difficult to know whether the defections could be linked to the examined military group, to the treatment VRET or a combination of these in the form of reexperiencing the traumatic experiences. From a TAM perspective, it would be essential to investigate what causes these dropouts to be able to analyze further whether this is an influencing factor related to user-friendliness or usability. As mentioned above, these patients that begin treatment may reeexperience too much of their combat-related trauma. Perhaps this specific patient group needs a more adapted variant of VRET treatment (Boeldt et al., Citation2019).

Combination therapies with VRET and medications such as D-cycloserine, alprazolam, or other types of benzodiazepines, and dexamethasone have, in most cases, reduced PTSD symptoms. Norrholm et al. (Citation2016) and Difede et al. (Citation2014) described VRET in combination with D-cycloserine or alprazolam reduced PTSD symptoms, and this reduction is permanent at follow-up after 3 and 6 months. However, the results of Rothbaum et al. (Citation2014) showed that combining VRET and benzodiazepine resulted in complicated recovery from anxiety disorders and PTSD. Also, Maples-Keller et al. (Citation2019) described those patients experienced symptoms of PTSD to a greater extent during the combination treatment with the medication dexamethasone for therapeutic indications.

Several of the included studies indicate that psychotropic medications can have enhanced effects of an exposure treatment such as VRE or VRET. Practice in Sweden suggests that most patients who seek care via primary care for depressive or anxiety symptoms are only treated with some form of antidepressant medication. Only 20 percent of them are referred to specialized psychiatry, where they can receive another type of treatment such as CBT or group therapy (National Board of Health and Welfare, Citation2021b).

VRET, in comparison with other alternative treatments

In several studies, a VRET treatment has been compared with another therapy and often with a control group (WL) that has not received any treatment. The results are difficult to generalize as the different treatment methods in several cases have been applied to various anxiety disorders or symptoms.

Anderson et al. (Citation2013) and Carl et al. (Citation2019) have in vivo and VRET shown a reduction in symptoms of anxiety disorders such as social anxiety and PTSD, but VRET has been a more acceptable, preferable, and effective alternative in comparison to in vivo. These may be the treatment methods that work most effectively as a health-promoting measure for adults suffering from anxiety disorders, even if the patient’s disease picture significantly impacts the treatment results. Kampmann et al. (Citation2016) have compared the treatment VRET and in vivo to reduce symptoms of social anxiety; both groups showed significant reductions in symptoms from pre- to post- assessment, but post- and follow-up assessments in vivo therapy resulted in a more substantial decrease in symptoms of social anxiety and improvements that were not achieved with VRET. In vivo exposure also reduced the fear of other people’s negative thoughts about themselves, improved their ability to speak in front of others, and improved general anxiety, depression, and improved quality of life compared to those in WL. Bouchard et al. (Citation2018) have compared the treatment methods VRET and in vivo but have also compared these with CBT, aiming to reduce social anxiety disorders. The results showed that VRET could be beneficial as a treatment method over the standard CBT method; unlike other studies, VRET could be even more beneficial compared to in vivo, as it could be more cost-effective and applicable than in vivo exposure.

Several comparisons between VRET and other treatment methods were found in some of the studies to reduce the symptoms of PTSD. Reger et al. (Citation2016) compared VRET and PE, McLay et al. (Citation2017) compared VRET and CET-control exposure therapy, and Beidel et al. (Citation2019) compared VRET with VRET together with TMT. In these studies, there were no significant differences in the outcome between the different forms of treatment, with the exception that TMT seemed to reduce the social isolation of the patients in this group.

Based on the results of several included studies, there appears to be no significant difference in the treatment from VRET compared with other types of treatment. In addition, some studies have come to opposite results even though they have reached the same types of treatment applied to the same disease (Bouchard et al., Citation2018; Kampmann et al., Citation2016). For this reason, it is not possible to generalize the comparisons between different methods regarding whether someone works better. This is also supported by a study by the SBU, which shows comparisons between VRET and other psychotherapeutic treatments showing that social anxiety is equivalent after treatment. On the other hand, other psychotherapeutic treatments had less effect in the long term than VRET, where the result was persistent (SBU, Citation2021).

Cost efficiency and implementation

When implementing a new treatment method in healthcare, it is important to consider its effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. Traditional therapies for anxiety-related disorders, as e.g., CBT have been proven to be effective. However, there have also been long-term problems with these therapies that primarily revolve around the costs and risks associated with the components that make up the therapeutic process (Oing & Prescott, Citation2018). It has also been mentioned by Pitti et al. (Citation2015) that the cost-effectiveness and efficiency of the treatment method are of great importance for implementation. To treat certain types of specific phobias, such as agoraphobia, sessions may need to be held in public, which risks the patient’s confidentiality and the emergence of uncontrollable circumstances, but also involves additional expenses for travel to a particular destination for the patient and therapist (Oing & Prescott, Citation2018).

Oing & Prescott (Citation2018) also describe that the versatility of VR means that different environments can be generated simultaneously, giving the therapist control over other variables that would otherwise be impossible to control in a natural setting. The results from studies have generally been positive despite the limitations of older variants of VR systems. It is then necessary to review these studies to identify how modern VR systems can be improved to treat anxiety symptoms, including phobias, depression, and PTSD (Pitti et al., Citation2015). The studies have shown the excellent and growing effectiveness of VRET as a treatment method for anxiety disorders. Nevertheless, it is also clear that VR technology needs to be improved to provide a sufficient holistic and interactive experience that can blur the boundaries between the real and virtual worlds (Bouchard et al., Citation2018; McLay et al., Citation2017; Oing & Prescott, Citation2018).

Methods discussion

The aim was to capture all those articles relevant to the research questions to provide a holistic view of existing research on this subject; however, this review has several strengths and limitations.

The included articles are taken from PubMed, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and MEDLINE databases, which may reduce the risk of relevant articles being overlooked or missed (Forsberg & Wengström, Citation2016). To reduce the incidence of selection bias, the keywords were first tested in each database to see the number of search results and whether they provided relevant literature. And to narrow and expand the search, we used search tools Boolean operators, truncation, and medical subject headings (MESH) to reduce the risk of missing relevant articles. The records varied between the databases, but according to selected keywords, the number of records was manageable and resulted to only studies of a quantitative method. This type of study can provide an answer the aim of the review which involved totally 1350 participants who were studied based on symptoms of some form of anxiety disorder, stress, or depression.

One requirement for articles to be included was that the reports were peer-reviewed via UlrichswebTM. Quality review of the included articles has been done using the CASP checklist for randomized controlled trials and clinical trials to ensure good quality, and this can be seen as a strength of the study. The analytical method used in this study was thematic analysis. Thematic analysis is used to identify, analyze, and report categories within the collected data and has been carefully described (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006).

One strength of the study was that most of the studies included were randomized controlled trials, which are often studies of high validity and reliability, focusing on the effect of different treatments between different randomized groups. Included studies were from 8 other countries, the USA, Canada, China, Brazil, the Netherlands, Australia, France, and Spain, which are from five different continents, languages, norms, and perspectives; this shows that these studies are performed similarly worldwide. This may mean that the content of the studies is considered relevant, which may make the results of our research more valid and reliable.

A weakness of our method is that a structured literature review is not considered generalizable as only a few articles in the specific area are studied. There is a risk that literature is not included because one’s interest in the field, and only literature that supports the hypothesis is included; therefore, the study may have a systematic error (Bryman, Citation2011; Forsberg & Wengström, Citation2016; SBU, Citation2017). Besides, some of the articles had only a few participants, which means that the results of these studies are not generalizable; this can be seen as a limitation to our study. Although the systematic discussion has been conducted alongside the work process to ensure similar perceptions by the reviewers, there is no guarantee that the reviewer’s perceptions have not influenced the results.

Conclusion

This study aims to investigate whether Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET) can be used as a treatment method for adults with anxiety disorders and depression. The current purpose resulted in the two issues that investigated whether VRET was as effective as a treatment method in treating anxiety disorders and depression compared with other treatment methods. And to examine, based on the TAM, which factors can influence patients’ perceptions of VRET’s usability and user-friendliness.

The study results indicate that VRET has positively affected the symptoms of anxiety disorders such as PTSD, social anxiety, and agoraphobia. There is also evidence that VRET acts as a treatment for depression, although in these cases, it is not clear whether VRET had a direct or indirect effect through the treatment of another disease. These findings suggest that VRET can be used as a health-promoting and as a treatment method initiative for a selected target group. When comparing VRET with other forms of treatment such as in vivo and PE, the results are varied. But reached in vivo, this treatment gave several times better treatment results than VRET.

On the other hand, in vivo treatment requires the patient and therapist to go to different places and thus create sessions; in reality, this creates uncertainty and triggers avoidant behavior in the patient. In this respect, VRET is advantageous because the treatment takes place with the therapist, who can control the environment that induces symptoms. Another strength of VRET is that the study results show that the treatment can work without a therapist, which means that the therapy in the long run could function as self-care for certain diseases and phobias. An additional conclusion from the results is that VRET can work better in combination with other forms of treatment, such as trauma management and psychotropic medicine.

In the results of this study, a component has emerged that can be an influencing factor in the TAM to influence patients’ perceptions of VRET’s usability and user-friendliness. This can be summarized in the information that therapists and healthcare professionals provide to the patient regarding what they can expect from the treatment both visually and what the patient will experience emotionally. This initial information has the potential to both provide security before treatment and a belief that the form of therapy works.

Further research should also include people over 65, as this age group is growing and suffering from mental illness to a greater extent. To help this group, further research is needed on whether VRET is an effective treatment method for improving the mental state of the elderly.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, P. L., Price, M., Edwards, S. M., Obasaju, M. A., Schmertz, S. K., Zimand, E., & Calamaras, M. R. (2013). Virtual reality exposure therapy for social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(5), 751–760. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033559

- Beidel, D. C., Frueh, B. C., Neer, S. M., Bowers, C. A., Trachik, B., Uhde, T. W., & Grubaugh, A. (2019). Trauma management therapy with virtual-reality augmented exposure therapy for combat-related PTSD: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 61(2019), 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.08.005

- Bentz, D., Wang, N., Ibach, K. M., Schicktanz, S. N., Zimmer, N., Papassotiropoulos, A., & Quervain de, J. F. D. (2021). Effectiveness of a stand-alone, smartphone-based virtual reality exposure app to reduce fear of heights in real-life: A randomized trial. NJP Digital Medicine, 4(16), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-021-00387-7

- Boeldt, D., McMahon, E., McFaul, M., & Greenleaf, W. (2019). Using virtual reality to enhance treatment of anxiety disorders: Identifying areas of clinical adoption and potential obstacles. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10(773), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00773

- Botella, C., Serrano, B., Baños, R. M., & Garcia-Palacios, A. (2015). Virtual reality exposure-based therapy for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: A review of its efficacy, the adequacy of the treatment protocol, and its acceptability. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 11, 2533–2545. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S89542

- Bouchard, S., Dumoulin, S., Robillard, G., Guitard, T., Klinger, É., Forget, H., Loranger, C., & Roucaut, F. X. (2018). Virtual reality compared with in vivo exposure in the treatment of social anxiety disorder: A three-arm randomized controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 210(4), 276–283. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.116.184234

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bryman, A. (2011). Samhällsvetenskapliga metoder (2: A uppl.). Liber.

- Buna, P., Gorskia, F., Grajewskia, D., Wichniarkea, R., & Zawadzkia, P. (2016). Low-cost devices used in virtual reality exposure therapy. Procedia Computer Science, 104(2017), 445–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2017.01.158

- Carl, E., Stein, T. A., Levihn-Coon, A., Pouge, R. J., Rothbaum, B., Emmelkamp, P., Asmundson, J. G., Carlbring, P., & Powers, B. M. (2019). Virtual reality exposure therapy for anxiety and related disorders: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 61(2019), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.08.003

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2018). CASP checklista. https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf

- Difede, J., Cukor, J., Wyka, K., Olden, M., Hoffman, H., Lee, F. S., & Altemus, M. (2014). D-cycloserine augmentation of exposure therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: A pilot randomized clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology: Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 39(5), 1052–1058. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2013.317

- Emmelkamp, P., & Meyerbröker, K. (2021). Virtual reality therapy in mental health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 17(21), 495–519. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-081219-115923

- Emmelkamp, P., Meyerbröker, K., & Morina, N. (2020). Virtual reality therapy in social anxiety disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports, 22(32), 2–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-020-01156-1

- European Commission. (2018). Mental Health. Public Health. https://health.ec.europa.eu/non-communicable-diseases/mental-health_en

- European Commission. (2019). Assessing the impact of digital transformation of health services. Report of the expert panel on effective ways of investing in health (EXPH). https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2019-11/022_digitaltransformation_en_0.pdf

- Folkhälsomyndigheten. (2018). Digital teknik för social delaktighet bland äldre personer- Ett kunskapsstöd om möjliga insatser utifrån forskning, praktik, statistik, juridik och etik. https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/contentassets/77f20aba933e42978c44fea69689a7e2/digital-teknik-for-social-delaktighet-bland-aldre-personer.pdf

- Folkhälsomyndigheten. (2020). Covid-19 pandemins tänkbara konsekvenser på folkhälsan. https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/publicerat-material/publikationsarkiv/c/covid-19-pandemins-tankbara-konsekvenser-pa-folkhalsan/?pub=76637

- Folkhälsomyndigheten. (2022). Statistik psykisk hälsa. https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/livsvillkor-levnadsvanor/psykisk-halsa-och-suicidprevention/statistik-psykisk-halsa/

- Forsberg, C., & Wengström, Y. (2016). Att göra systematiska litteraturstudier (4: Uppl.). Natur & Kultur.

- Garcia-Palacios, A., Botella, C., Hoffman, H., & Fabregat, S. (2007). Comparing acceptance and refusal rates of virtual reality exposure vs. in vivo exposure by patients with specific phobias. Cyberpsychology & Behavior: The Impact of the Internet, Multimedia and Virtual Reality on Behavior and Society, 10(5), 722–724. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2007.9962

- Gebara, C. M., Barros-Neto, T. P., Gertsenchtein, L., & Lotufo-Neto, F. (2016). Virtual reality exposure using three-dimensional images for the treatment of social phobia. Revista Brasileira De Psiquiatria (São Paulo, Brazil: 1999), 38(1), 24–29. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2014-1560

- Geraets, C., Veling, W., Witlox, M., Staring, A., Matthijssen, S., & Cath, D. (2019). Virtual reality-based cognitive behavioural therapy for patients with generalized social anxiety disorder: A pilot study. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 47(6), 745–750. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465819000225

- Hartanto, D., Kampmann, I. L., Morina, N., Emmelkamp, P. G., Neerincx, M. A., & Brinkman, W. P. (2014). Controlling social stress in virtual reality environments. PLoS One. 9(3), e92804. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0092804

- Jacobsen, K. H. (2019). Mental health - Introduction to global health (Vol. 3, pp. 381–392). Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Kampmann, I. L., Emmelkamp, P. M., Hartanto, D., Brinkman, W. P., Zijlstra, B. J., & Morina, N. (2016). Exposure to virtual social interactions in the treatment of social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 77, 147–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.12.016

- Kishimoto, T., & Ding, X. (2019). The influences of virtual social feedback on social anxiety disorders. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 47(6), 726–735. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465819000377

- Kothgassner, O. D., Felnhofer, A., Hlavacs, H., Beutl, L., Palme, R., Kryspin-Exner, I., & Glenk, L. M. (2016). Salivary cortisol and cardiovascular reactivity to a public speaking task in a virtual and real-life environment. Computers in Human Behavior, 62(C), 124–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.081

- Kothgassner, O. D., Goreis, A., Kafka, J. X., Van Eickels, R. L., Plener, P. L., & Felnhofer, A. (2019). Virtual reality exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): A meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1654782. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1654782

- Levy, F., Leboucher, P., Rautureau, G., & Jouvent, R. (2016). E-virtual reality exposure therapy in acrophobia: A pilot study. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 22(4), 215–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X15598243

- Linder, P., Alexander, M., Elin, Z., Lena, R., Gerhard, A., & Per, C. (2018). Attitudes towards and familiarity with virtual reality therapy among practicing cognitive behavior therapists: A cross-sectional survey study in the era of consumer VR platforms. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(76), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00176

- Ma, L., Mor, S., Anderson, P. L., Baños, R. M., Botella, C., Bouchard, S., Cárdenas-López, G., Donker, T., Fernández-Álvarez, J., Lindner, P., Mühlberger, A., Powers, M. B., Quero, S., Rothbaum, B., Wiederhold, B. K., & Carlbring, P. (2021). Integrating virtual realities and psychotherapy: SWOT analysis on VR and MR based treatments of anxiety and stress-related disorders. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 50(6), 509–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2021.1939410

- Malbos, E., Rapee, R. M., & Kavakli, M. (2013). A controlled study of agoraphobia and the independent effect of virtual reality exposure therapy. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 47(2), 160–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867412453626.

- Maples-Keller, J. L., Bunnell, B. E., Kim, S. J., & Rothbaum, B. O. (2017). The use of virtual reality technology in the treatment of anxiety and other psychiatric disorders. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 25(3), 103–113. https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0000000000000138

- Maples-Keller, J. L., Jovanovic, T., Dunlop, B. W., Rauch, S., Yasinski, C., Michopoulos, V., Coghlan, C., Norrholm, S., Rizzo, A. S., Ressler, K., & Rothbaum, B. O. (2019). When translational neuroscience fails in the clinic: Dexamethasone prior to virtual reality exposure therapy increases drop-out rates. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 61, 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.10.006

- McLay, R. N., Baird, A., Webb-Murphy, J., Deal, W., Tran, L., Anson, H., Klam, W., & Johnston, S. (2017). A randomized, head-to-head study of virtual reality exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 20(4), 218–224. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2016.0554

- McLay, R. N., Ram, V., Murphy, J., Spira, J., Wood, D. P., Wiederhold, M. D., Wiederhold, B. K., Johnston, S., & Reeves, D. (2014). Effect of virtual reality PTSD treatment on mood and neurocognitive outcomes. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 17(7), 439–446. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2013.0383

- Morina, N., Brinkman, W. P., Hartanto, D., Kampmann, I. L., & Emmelkamp, P. M. (2015). Social interactions in virtual reality exposure therapy: A proof-of-concept pilot study. Technology and Health Care: Official Journal of the European Society for Engineering and Medicine, 23(5), 581–589. https://doi.org/10.3233/THC-151014

- Norr, A. M., Smolenski, D. J., Katz, A. C., Rizzo, A. A., Rothbaum, B. O., Difede, J., Koenen-Woods, P., Reger, M. A., & Reger, G. M. (2018). Virtual reality exposure versus prolonged exposure for PTSD: Which treatment for whom? Depression and Anxiety, 35(6), 523–529. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22751

- Norrholm, S. D., Jovanovic, T., Gerardi, M., Breazeale, K. G., Price, M., Davis, M., Duncan, E., Ressler, K. J., Bradley, B., Rizzo, A., Tuerk, P. W., & Rothbaum, B. O. (2016). Baseline psychophysiological and cortisol reactivity as a predictor of PTSD treatment outcome in virtual reality exposure therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 82, 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.05.002

- Oing, T., & Prescott, J. (2018). Implementations of virtual reality for anxiety-related disorders: Systematic review. JMIR Serious Games, 6(4), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.2196/10965

- Patel, V., Minas, H., Cohen, A., & Prince, M. J. (2013). Global mental health: Principles and practice. Oxford University Press. Incorporated.

- Patel, V., Saxena, S., Lund, C., Thornicroft, G., Baingana, F., Bolton, P., Chisholm, D., Collins, P. Y., Cooper, J. L., Eaton, J., Herrman, H., Herzallah, M. M., Huang, Y., Jordans, M., Kleinman, A., Medina-Mora, M. E., Morgan, E., Niaz, U., Omigbodun, O., Prince, M., … UnÜtzer, J. (2018). The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet (London, England), 392(10157), 1553–1598. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31612-X

- Peskin, M., Wyka, K., Cukor, J., Olden, M., Altemus, M., Lee, F. S., & Difede, J. (2019). The relationship between posttraumatic and depressive symptoms during virtual reality exposure therapy with a cognitive enhancer. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 61, 82–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.03.001

- Pitti, C. T., Peñate, W., de la Fuente, J., Bethencourt, J. M., Roca-Sánchez, M. J., Acosta, L., Villaverde, M. L., & Gracia, R. (2015). The combined use of virtual reality exposure in the treatment of agoraphobia. Actas Espanolas De Psiquiatria, 43(4), 133–141.

- Pittig, A., Kotter, R., & Hoyer, J. (2019). The struggle of behavioral therapists with exposure: Self-reported practicability, negative beliefs, and therapist distress about exposure-based interventions. Behavior Therapy, 50(2), 353–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2018.07.003

- Price, M., Mehta, N., Tone, E. B., & Anderson, P. L. (2011). Does engagement with exposure yield better outcomes? Components of presence as a predictor of treatment response for virtual reality exposure therapy for social phobia. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25(6), 763–770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.03.004

- Reger, G. M., Koenen-Woods, P., Zetocha, K., Smolenski, D. J., Holloway, K. M., Rothbaum, B. O., Difede, J., Rizzo, A. A., Edwards-Stewart, A., Skopp, N. A., Mishkind, M., Reger, M. A., & Gahm, G. A. (2016). Randomized controlled trial of prolonged exposure using imaginal exposure vs. virtual reality exposure in active-duty soldiers with deployment-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(11), 946–959. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000134

- Reger, G. M., Smolenski, D., Edwards-Stewart, A., Skopp, N. A., Rizzo, A. S., & Norr, A. (2019). Does virtual reality increase simulator sickness during exposure therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder? Telemedicine Journal and e-Health: The Official Journal of the American Telemedicine Association, 25(9), 859–861. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2018.0175

- Rocco, T. S., Plakhotnik, M. S., McGill, C. M., Huyler, D., & Collins, J. C. (2023). Conducting and writing a structured literature review in human resource development. Human Resource Development Review, 22(1), 104–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/15344843221141515

- Rothbaum, B. O., Price, M., Jovanovic, T., Norrholm, S. D., Gerardi, M., Dunlop, B., Davis, M., Bradley, B., Duncan, E. J., Rizzo, A., & Ressler, K. J. (2014). A randomized, double-blind evaluation of D-cycloserine or alprazolam combined with virtual reality exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in Iraq and Afghanistan War veterans. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(6), 640–648. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13121625

- Sjöström, N., & Skärsäter, I. (2014). I. Ångestsyndrom. I I., Skärsäter (Red.) Omvårdnad vid Psykisk Ohälsa, på grundläggande nivå. (3 Uppl., S. 77–69). Studentlitteratur.

- Socialstyrelsen. (2021a). Postcovid - kvarstående eller sena symptom efter covid-19. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/ovrigt/2021-4-7351.pdf

- Socialstyrelsen. (2021b). Nationella Riktlinjer för vård vid depression och ångestsyndrom. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/nationella-riktlinjer/2021-4-7339.pdf

- Soltani, P. (2019). A SWOT analysis of virtual reality (VR) for seniors. In G. Guazzaroni (Ed.), Virtual and augmented reality in mental health treatment (pp. 78–93). IGI Global Publisher of Timely Knowledge. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-7168-1.ch006

- Statens Beredning för Medicinsk och Social Utvärdering (SBU). (2017). Välfärdsteknik: Digital verktyg som social stimulans för äldre personer med eller vid risk för psykisk ohälsa. https://www.sbu.se/sv/publikationer/sbu-kartlagger/valfardsteknik–digitala-verktyg-som-social-stimulans-for-aldre-personer-med-eller-vid-risk-for-psykisk-ohalsa/

- Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering (SBU). (2021). Virtual reality i behandlinga av ångestsyndrom. https://www.sbu.se/sv/publikationer/sbus-upplysningstjanst/virtual-reality-i-behandling-av-angestsyndrom/

- Stetz, M. C., Ries, R., I., Folen,., & R., A. (2011). Virtual reality supporting psychological health. In S. Brahnam & L. C. Jain (Eds.), Advanced computational intelligence paradigms in healthcare 6. Virtual reality in psychotherapy, rehabilitation, and assessment (pp. 13–29). Springer.

- Swedish eHealth Agency. (2020). Ökad användning av digitala tjänster under pandemiåret 2020. https://www.ehalsomyndigheten.se/nyheter/2021/e-halsomyndigheten-foljer-upp-den-digitala-utvecklingen-inom-halso--och-sjukvard-och-socialtjanst/

- Wood, P. D., Murphy, J., Mclay, R., Koffman, R., Spira, J., Obrecht, E. R., Pyne, J., & Wiederhold, K. B. (2009). Cost effectiveness of virtual reality graded exposure therapy with physiological monitoring for the treatment of combat related post traumatic stress disorder. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 144(1), 223–229. https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-60750-017-9-223

- World Health Organisation. (2022). World mental health report: Transforming mental health for all. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240049338

- Zainal, N. H., Chan, W. W., Saxena, A. P., Taylor, C. B., & Newman, M. G. (2021). Pilot randomized trial of self-guided virtual reality exposure therapy for social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 147, 103984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2021.103984

- Zhang, W., Paudel, D., Shi, R., Liang, J., Liu, J., Zeng, X., Zhou, Y., & Zhang, B. (2020). Virtual reality exposure therapy (VRET) for anxiety due to fear of COVID-19 infection: A case series. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 16, 2669–2675. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S276203