Abstract

This scoping review brings together existing studies on the use of cats in animal-assisted interventions, as assistance animals and as companion animals for autistic people. A systematic search across PubMed, CINAHL and Scopus in September 2022 identified 13 articles from 12 studies meeting the selection criteria with analysis revealing two key findings, cat-assisted therapeutic interventions, and cats as companion animals. There were five themes that emerged: the characteristics and behaviours of cats that make them suitable for inclusion in homes with autistic people; the bond between the cat and the autistic person; the use of cats as human-substitutes; the multiple ways in which cats improved the lives and social functioning of autistic people; and, some noted drawbacks or considerations of cat ownership. The review generates a comprehensive knowledge base upon which to promote feline therapy in autism and to advocate for further targeted research.

Introduction

The use of animals as a tool to improve outcomes for people with disabilities has a long and positive history. A plethora of research has found positive health and social outcomes for people when a range of animals, including dogs, horses, dolphins and cats, are brought into their lives in various ways. There are animal-assisted interventions, such as horseback riding, swimming with dolphins or conducting occupational therapy with animals included (Nieforth et al., Citation2021). This integrates the animal into the therapeutic interventions being conducted to improve the social, language, motor and behavioural skills or outcomes for those with a disability, or by providing a calming support to facilitate comfort and engagement. There are service or assistance animals, who assist those who are vision or hearing impaired as well as providing physical assistance to those with limited mobility (Parenti et al., Citation2013). And there are companion animals, who can support healthy emotional attachment and development for those with such diagnoses as anxiety (Purewal et al., Citation2017). This is in addition to the large numbers of domestic pets who offer companionship in households both with and without disabilities.

Autism, or autism spectrum disorder (ASD), is one such diagnosis where animals have been used in ever-increasing numbers and ways to aid development and promote positive outcomes. A key feature of autism is a series of deficits, particularly in communication, social functioning and restricted behaviours (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). There are also increased likelihoods of co-occurring mental health conditions (Lau et al., Citation2019), self-harm (Hirvikoski et al., Citation2016), sleep disorders (Reynolds et al., Citation2019) and intellectual impairment (Elsabbagh et al., Citation2012). Considerable research has demonstrated the ways in which animals can improve self-esteem, reduce feelings of loneliness (Purewal et al., Citation2017), increase social interactions (O’Haire, Citation2017) and improve motivation and communication (London et al., Citation2020) for autistic adults and children. These animals have the capacity to bring out social interaction skills, reverse difficulties with processing some stimuli and produce increased attention and eye contact from autistic children and adults (Atherton & Cross, Citation2019; Valiyamattam et al., Citation2020).

While much of the literature focuses on canine and equine interventions for autistic people (Nieforth et al., Citation2021), a small but growing body of research has begun to focus in full or in part on the role cats can play. The aim of this scoping review is to review all studies that have focussed on the role cats can and do play in improving the lives of autistic people whether this be through their use in interventions such as occupational therapy or behaviour support, as assistance animals, or through companionship. This aim includes both studies where cats have been introduced to autistic people and the results are observed and recorded as well as studies that consider how to integrate cats into autistic people’s lives, such a behaviours and traits of these cats.

Methods

Design

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) framework and subsequently advanced by Levac et al. (Citation2010). A five stepped approach was undertaken: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) data charting; and, (5) collecting, summarising and reporting results. Results of the scoping review reported in this article are in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) extension for scoping reviews (Tricco et al., Citation2018).

Review aim

This scoping review brings together existing studies on the use of cats in animal-assisted interventions, as assistance animals and as companion animals for autistic people. The aim of the review is to generate a comprehensive knowledge base upon which to promote feline therapy in autism and to advocate for further targeted research.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are outlined in . Where studies reported on other animals, our review focused on findings that relate specifically to cats.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Search strategy

A comprehensive electronic database literature search was conducted on September 2, 2022, using PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and Scopus. Boolean operators AND/OR were used to design a search strategy combining Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and keywords: Asperger Syndrome OR Autistic Disorder OR Autism Spectrum Disorder OR ASD AND Human-Animal Bond OR Animal Assisted Therapy OR Therapy Animals OR Cats OR Pets OR companion animal (see for PubMed search strategy). The Boolean term NOT was not used as this resulted in the exclusion of articles that met the inclusion criteria e.g., NOT dog.

Table 2. PubMed search strategy.

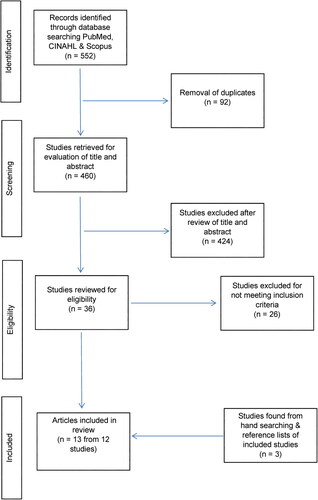

English language, peer-reviewed articles reporting primary research were included, with no parameters placed on the publication date. After duplicates were removed, we identified 460 records. Titles and abstracts were independently screened. This was followed by a review of full text articles by the same identified authors. Free searching and review of reference lists of included studies resulted in the identification of three further studies (). Discrepancies were resolved by consultation within the team. This resulted in 13 articles, which reflected 12 individual studies for analysis, were included in this review.

Figure 1. PRISMA (Tricco et al., Citation2018).

Data charting

The characteristics of the included articles were extracted in the following format: author(s), year of publication and country; the purpose of the study; methods/research design; participants/subjects; and relevant findings (see ).

Table 3. Summary of included studies.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was used as defined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) for the development of themes. This encompassed one of the authors (SW) reading the included articles in detail and then subsequently re-reading the articles using analysis software NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd, Citation2020). It was while re-reading the articles that the articles were coded in alignment to the review aim—to consolidate research and understanding of the benefits of cat ownership or interactions with cats for autistic people. After the primary codes were reviewed accordingly, the themes were identified that included dividing each code into sub themes. Finally, the author (MC) reviewed the themes and sub themes to achieve consensus.

Results

The studies meeting the inclusion criteria are presented in and were published between 2015 and 2022. Of the included articles seven were from the United States of America (Carlisle et al., Citation2018, Citation2020, Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Hart et al., Citation2018; Lamontagne et al., Citation2020; Ward et al., Citation2017), followed by two from South Korea (Kwon et al., Citation2015; Lee et al., Citation2017) and the United Kingdom (Atherton et al., Citation2022; Keville et al., Citation2022), and one from Sweden (Byström & Lundqvist Perssontt, Citation2015) and France (Grandgeorge et al., Citation2020).

The included studies focussed on autistic populations as compared to neurotypical individuals (Atherton et al., Citation2022), only children (Grandgeorge et al., Citation2020; Kwon et al., Citation2015; Lee et al., Citation2017), only parents/caregivers (Carlisle et al., Citation2018, Citation2020; Hart et al., Citation2018; Keville et al., Citation2022), children and parents (Byström & Lundqvist Perssontt, Citation2015; Carlisle et al., Citation2021a; Ward et al., Citation2017), and only cats (Carlisle et al., Citation2021a; Lamontagne et al., Citation2020). Participant numbers ranged from five children (Kwon et al., Citation2015) to 764 parents (Carlisle et al., Citation2020). Three studies used surveys for data collection (Carlisle et al., Citation2018, Citation2020; Ward et al., Citation2017), three used observation (Grandgeorge et al., Citation2020; Kwon et al., Citation2015; Lee et al., Citation2017), one used interviews (Keville et al, Citation2022), two used interviews in addition to a survey (Atherton et al., Citation2022; Hart et al., Citation2018) one involved a randomised control trial (Carlisle et al., Citation2021b), one conducted pathology tests to measure stress levels (Carlisle et al., Citation2021a), one used a focus group (Byström & Lundqvist Perssontt, Citation2015), one used open-ended questions from a cross-sectional survey (Carlisle et al., Citation2018), and one applied a screening tool to measure behaviours of cats (Lamontagne et al., Citation2020). Analysis of the included studies indicated a significant focus on the use of cats as companion animals, with 10 of the 13 studies focussing on this type of relationship and one study (Carlisle et al., Citation2021a) exploring the welfare of cats in families of children with ASD. Two studies looked at the role of robotic cats in interventions such as language therapy and occupational therapy (Kwon et al., Citation2015; Lee et al., Citation2017). No studies were found that discussed a possible role for cats as assistance animals.

Cat-assisted therapeutic interventions

Of the two studies (Kwon et al., Citation2015; Lee et al., Citation2017) that focussed on cats as part of formal intervention sessions, both involved observations of children interacting with a robot cat. A robot cat can be designed to look like and mimic the behaviour of cats and be specifically programmed to engage in behaviours and have therapeutic expressions known to better engage autistic people (Kwon et al., Citation2014; Lee et al., Citation2014; Mun et al., Citation2014). The first study involved video recording autistic children interacting with a robotic cat that had been specifically developed for interaction with autistic people as part of therapy sessions with a language therapist and play therapist (Kwon et al., Citation2015). The results showed increased eye contact by the child over the course of the treatment sessions, increased verbalisation, efforts to assist the robot when it fell, actively approaching the robot, touching and hugging it, and responding to specific questions about the robot cat given by the therapists. Hostility shown by one of the children turned to positive behaviour after a few sessions. Only one child showed a decrease in interest by the third session.

The second study had two stages and occurred at a school specifically for autistic children (Lee et al., Citation2017). In the first stage children eventually showed considerable interest in the robot cat after some initial caution and disinterest. Based on the observations of which functions the children did and did not find easy to engage with, the robot was refined and retested in the second stage. This included adding sounds specific to each child’s individual characteristics. This produced positive reactions including hugging and shaking hands with the robot. However, the facial expressions programming appeared too complex for the children to understand.

Overall, both studies found increased levels of interaction by the child when observed with a purpose-built robot cat.

Cats as companion animals

The ownership of cats among families with an autistic family member was noted as being high (Carlisle et al., Citation2018), with autistic people more likely to own a cat than their neurotypical counterparts (Atherton et al., Citation2022). While cat ownership amongst autistic people was higher than dog ownership in one study (Ward et al., Citation2017) and lower in another (Atherton et al., Citation2022), the perceived benefits of owning a companion animal were highest when families owned both a dog and a cat as opposed to just one or the other (Carlisle et al., Citation2020).

While all studies that focussed on companion animals had at least some discussion of cats, one study was actually meant to be exclusively about dog ownership. However, some participants gave answers in relation to their cats and data relating to cats were included in the analysis (Carlisle et al., Citation2018). Within the findings related to cats as companions there were five themes that emerged: the characteristics and behaviours of cats that make them suitable for inclusion in homes with autistic people; the bond between the cat and the autistic person; the use of cats as human-substitutes; the multiple ways in which cats improved the lives and social functioning of autistic people; and some noted drawbacks or considerations of cat ownership.

Behaviour and characteristics of cats

Understanding the behaviours and characteristics of those cats more suited for adoption by a family with an autistic person is crucial for boosting the quality of the relationship and reducing the chances of relinquishment of the cat. One study noted the importance of matching the characteristics of the cat with the characteristics of the family (Carlisle et al., Citation2018). Only through systematic assessment of a cat’s potential to successfully integrate into the family is the process more readily able to achieve the desired outcome. One study discussed the application of a systematic screening and assessment tool known as the Feline Temperament Profile (FTP), which when used resulted in cats that acclimated to their new homes well (Carlisle et al., Citation2021a). Selection of cats by shelter staff without use of the profile tool resulted in only a 34% suitability rate.

Characteristics of cats that were noted positively by participants included allowing themselves to be carried by the autistic person (Carlisle et al., Citation2018), being affectionate and lacking aggression (Hart et al., Citation2018). Several studies noted that cats often seemed to understand that the autistic person was unique and were more tolerant of that person, often preferring them to others (Carlisle et al., Citation2018; Hart et al., Citation2018; Keville et al., Citation2022).

Lamontagne et al. (Citation2020) reported the applicability of the FTP with cats scoring higher acceptable behaviour in the FTP test associated with decreased the likelihood of being rejected, while questionable behaviour scores increased the likelihood of being rejected. Further, the study indicated a possible relationship between the pre-adoption environment and cat behaviour. One animal shelter that allowed for cat-to-cat and human-to-cat interactions had a higher rate of cats exhibiting acceptable behaviours for adoption into an autism family (Lamontagne et al., Citation2020). This allowed for more successful adoptions and reduced relinquishment.

The human-cat bond

Six of the included studies made explicit mention of the strong mutual bond that developed between the cat and the autistic person, with one study noting that the autistic person appeared to bond more with cats than with dogs (Carlisle et al., Citation2018). The relationship was described as ‘unique, deep and joyful’ (Byström & Lundqvist Perssontt, Citation2015), where the person needed the cat with them often (Keville et al., Citation2022). The autistic person would demonstrate the bond through higher visual attention to the cat (Grandgeorge et al., Citation2020), physical affection such as hugging (Hart et al., Citation2018), reading to the cat (Carlisle et al., Citation2018), and a fear of losing them (Keville et al., Citation2022). This bond appeared to only increase during the COVID-19 pandemic as cats were considered to have provided a consistent and calming influence during considerable change and extended periods of time at home (Keville et al., Citation2022). Interestingly, one study noted that parents with lower incomes perceived more benefits of cat ownership and their children were more strongly bonded with their cat (Carlisle et al., Citation2020).

Cats as substitutes for human interactions

Almost half the studies had findings that demonstrated the use of companion animals, including cats, as substitutes for human companions. Autistic people are more likely to be socially avoidant (Atherton et al., Citation2022; Ward et al., Citation2017) and cats were used as a compensatory mechanism for this. The greater the social impairment the higher the reported quality of the friendship between the person and the cat was found to be (Ward et al., Citation2017). The companion cat was used as a substitute for human companionship as the relationship required fewer rules than human interactions and allowed the person to be themselves and forgo the socially acceptable camouflaging they might otherwise use (Atherton et al., Citation2022). Cats were considered to ‘ask no questions’, give unconditional comfort and offer the person at least one friend to feel connected with and with whom they could experience moments of spontaneous joy (Byström & Lundqvist Perssontt, Citation2015) and talk to (Carlisle et al., Citation2018). These characteristics of the relationship allowed the autistic person to improve their socialisation skills, with one parent making the powerful statement that her daughter’s cats “bring her back to me” (Hart et al., Citation2018, p.6).

Positive effects of cat ownership

Eight included studies had findings that demonstrated the way in which the lives of the autistic person were improved by having a companion cat. These improvements were in the areas of responsibility, social interaction and communication, stress, and self-regulation.

Six studies highlighted that cat ownership had fostered a sense of responsibility in the autistic person (Atherton et al., Citation2022; Byström & Lundqvist Perssontt, Citation2015; Carlisle et al., Citation2018, Citation2021b; Keville et al., Citation2022; Ward et al., Citation2017). There were a number of positive outcomes that followed on from this sense of responsibility. This included feeling motivated to have an active life (Atherton et al., Citation2022), having a better understanding of other people’s needs (Byström & Lundqvist Perssontt, Citation2015), learning about healthy eating through feeding their cat (Keville et al., Citation2022) and fewer depressive symptoms, as measured by linear regression analyses of pet ownership dimensions and depressive symptoms (Ward et al., Citation2017). One study found evidence that the more responsibility an autistic person took of their cat the more likely they were to turn to the cat for companionship and comfort (Ward et al., Citation2017).

A further six studies looked at the ways in which cat ownership improved social interactions and communication. Cats were identified as a form of cost-effective social support (Atherton et al., Citation2022) that helps increase the interactions between the autistic person and others, reduces fear and uneasiness, as reported by parents in one study (Byström & Lundqvist Perssontt, Citation2015), teaches them how to love others and how to trust (Carlisle et al., Citation2018), builds social skills (Carlisle et al., Citation2021b), promotes language development through talking to their cats (Hart et al., Citation2018), and promotes consideration and empathy for others (Keville et al., Citation2022). One study noted that when a child and cat interacted their activities were more social in nature and of a different quality to the often restricted and repetitive activities of the child (Byström & Lundqvist Perssontt, Citation2015).

Another focus of considerable improvement was stress reduction and self-regulation. Cats were considered to have a calming effect on the autistic person (Atherton et al., Citation2022; Carlisle et al., Citation2018; Hart et al., Citation2018; Keville et al., Citation2022; Ward et al., Citation2017), reducing anxiety (Carlisle et al., Citation2021b) and stress, and facilitating the person to better regulate their feelings (Byström & Lundqvist Perssontt, Citation2015). Regulation of self was aided by the sensory benefits of stroking the cat’s fur or the purring sound of the cat (Atherton et al., Citation2022; Keville et al., Citation2022). This was noted as being particularly important and beneficial during the global lockdowns of the COVID-19 pandemic (Keville et al., Citation2022), when consistency for the person was needed.

Negatives, drawbacks, and considerations of cat ownership

While all the included studies demonstrated positive outcomes from interactions between autistic people and cats, either in animal-assisted interventions or through companion animals, five studies did draw attention to some negative outcomes. Cats, like any pet, were identified as being expensive to maintain and demanding a time commitment which some owners did not feel they could responsibly meet (Atherton et al., Citation2022). Some cats, adopted as adult cats from a shelter in one particular study, were noted as eliminating outside their litter trays or crying constantly when the autistic child was not at home, which caused the parents to relinquish these cats (Carlisle et al., Citation2021b). One study highlighted that aggression by the person towards the cat did occur (Carlisle et al., Citation2018) which then required supervision and time limits on their interactions. Alternatively, aggression by the cat towards the person was between 19–27% depending on the severity of the support needs (Hart et al., Citation2018). Fear of cats by the autistic person did not appear to be a significant issue however, with one study putting this at 0.4% with their child being afraid of cats (Carlisle et al., Citation2020).

Discussion

Analysis and synthesis of the included studies resulted in consistent findings on the benefits of cats being introduced into the homes and therapies of autistic people. These benefits included increased skills in socialisation, communication, and self-regulation and reductions in anxiety, stress and social disconnection. Cats offered a substitute or complement to human interaction for autistic people to experience companionship, comfort and sensory enjoyment and the cats appeared often to understand the special needs of the autistic person and to favour them.

However, these findings also pointed to the importance of a rigorous process to ensure cats are suitably prepared for adoption or use in animal-assisted interventions and that screening for certain behaviours and characteristics is important to ensuring the long-term success of these human-animal relationships. Behavioural assessments and screening tools can aid the matching of cats and people, detect unwanted behaviours and monitor cat wellbeing while in the pre-adoption shelter environment (Ellis, Citation2022). Such screening tools need to be evidence-based and specific to species, rather than based on the observations and judgements of shelter staff. One recent study that looked at screening of dogs for adoption found shelter staff looked at 42 most valued characteristics when determining suitability for adoption, yet of these 42 only 10 had a scientific evidence base to support them (Griffin et al., Citation2022).

A unique element of the role that cats can play was the possible use of specially designed robot-like cats. The idea of a robot as a tool for therapeutic interventions has a steadily expanding evidence base. A recent systematic review found no less than 38 articles focussing on the use of robots in autism therapy with these robots being found to offer the unique ability to guide autistic children into more complex forms of interaction that mimic human interactions (Alabdulkareem et al., Citation2022).

Limitations

This scoping review experienced several limitations that restricted our capacity to fully answer the review aims. The search strategy yielded no results discussing cats being used as assistance animals. Assistance animals are trained to complete specific tasks, such as opening and closing doors, navigating a journey safely for the vision impaired, alerting people to a medical risk or episode, or to interrupt anxiety (RSPCA, Citation2022). While cats may be incompatible with opening and closing doors or navigating, the findings of this review do indicate the capacity for cats to positively impact anxiety. The absence of research in this area could therefore reflect a lack of use of cats in assistance roles to interrupt anxiety or it could simply indicate a lack of research examining instances where this has been done.

The review was also restricted by only finding two studies that directly discussed the use of cats in animal-assisted interventions and further by the fact that both articles discussed the use of a robotic cat. The use of animals in interventions or therapies has become increasingly common with autism, dating back to the 20th century (Ang & MacDougall, Citation2022), with consistent findings of increased social interaction for autistic people (O’Haire, Citation2017). Yet despite the increasing focus on the role of animal-assisted therapy there appears to be limited (if any) research focussing on the use of cats in the field and there was an absence of studies that had used real cats to investigate therapeutic interventions.

Future directions

As the first noted review to synthesise research findings relating to the use of cats in therapy and companionship for autistic adults and children, this review provides detail of many opportunities for future research and application. Successful transition of cats into long-term homes or for use in therapeutic interventions can be achieved by the consistent and comprehensive use of evidence-based screening tools, the likes of which need to be accessible and usable by shelter staff. The FTP is a useful screening tool to identify cats with acceptable behaviour and can be shortened with no loss of reliability (Lamontagne et al., Citation2020). This review has also found an absence of any study of cats for use as assistance animals, particularly in the area of interrupting anxiety, as well as an absence of any study that focussed on the use of live cats in therapeutic interventions. Each of these findings and limitations provides scope for future research.

Implications

The use of cats in therapy and companionship for autistic adults and children has multiple implications for the work of health professionals and mental health nurses. At the core of nursing is a role as a consumer advocate and nurses need to be open to, and actively searching for innovations that can aid their advocacy role and outcomes for consumers. The benefits drawn from cats can improve consumer wellbeing and quality care, including reduced negative mental health symptoms (Koukourikos et al., Citation2019), and therefore mental health nurses have a clear role as advocates and champions for consumers and educators of others on the benefits of animal assisted interventions (Sargsyan, Citation2021) which can include reference to cats as one possibility. Additionally, mental health nurses can derive their own benefits from cat-assisted therapies and interventions, with some research finding that the healthcare workers who are exposed to animal-assisted interventions have lower work-related stress levels which serves to protect their own psychosocial health and wellbeing (Acquadro Maran et al., Citation2022).

Conclusion

This scoping review has established that there remains limited research on the use of cats for autistic people but among the research that does exist, the findings are consistent on the benefits that can be realised from promoting cats as an assistant in interventions and as a companion to autistic people. In addition to the behavioural benefits, such as increasing motivation or social skills, cats are also often a low maintenance and cost-effective animal for use as a companion. While more research needs to occur to fully scope the roles that cats may play in autism and to allow for consistent screening, their inclusion as a feasible and desirable animal in autism therapy appears clear and inevitable.

Authors’ contributions

All authors have agreed on the final version and meet at least one of the following criteria recommended by the ICMJE (http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/):

Substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Conceptualisation: MC, SW. Funding acquisition: MC, SW. Systematic search: RK, MC. Screening: MC, RK, SW. Data Charting: MC, RK, DT, SW. Data analysis and interpretation: SW, MC. Data checking: All authors. Draft writing: SW, MC, RK, DT. Review of drafts: All authors. Approval: All authors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acquadro Maran, D., Capitanelli, I., Cortese, C. G., Ilesanmi, O. S., Gianino, M. M., & Chirico, F. (2022). Animal-assisted intervention and health care workers’ psychological health: A systematic review of the literature. Animals, 12(3), 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12030383

- Alabdulkareem, A., Alhakbani, N., & Al-Nafjan, A. (2022). A systematic review of research on robot-assisted therapy for children with autism. Sensors, 22(3), 944. https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/22/3/944

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Ang, C. S., & MacDougall, F. A. (2022). An Evaluation of animal-assisted therapy for autism spectrum disorders: Therapist and parent perspectives. Psychological Studies, 67(1), 72–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-022-00647-w

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Atherton, G., & Cross, L. (2019). Animal faux pas: Two legs good four legs bad for theory of mind, but not in the broad autism spectrum. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 180(2–3), 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2019.1593100

- Atherton, G., Edisbury, E., Piovesan, A., & Cross, L. (2022). ‘They ask no questions and pass no criticism’: A mixed-methods study exploring pet ownership in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-022-05622-y

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Byström, K. M., & Lundqvist Perssontt, C. A. (2015). The meaning of companion animals for children and adolescents with autism: The parents’ perspective. Anthrozoos, 28(2), 263–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2015.11435401

- Carlisle, G. K., Johnson, R. A., Koch, C. S., Lyons, L. A., Wang, Z., Bibbo, J., & Cheak-Zamora, N. (2021a). Exploratory study of fecal cortisol, weight, and behavior as measures of stress and welfare in shelter cats during assimilation into families of children with autism spectrum disorder. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 8, 643803. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2021.643803

- Carlisle, G. K., Johnson, R. A., Mazurek, M., Bibbo, J. L., Tocco, F., & Cameron, G. T. (2018). Companion animals in families of children with autism spectrum disorder: Lessons learned from caregivers. Journal of Family Social Work, 21(4/5), 294–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/10522158.2017.1394413

- Carlisle, G. K., Johnson, R. A., Wang, Z., Bibbo, J., Cheak-Zamora, N., & Lyons, L. A. (2021b). Exploratory study of cat adoption in families of children with autism: Impact on children’s social skills and anxiety. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 58, 28–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2020.11.011

- Carlisle, G. K., Johnson, R. A., Wang, Z., Brosi, T. C., Rife, E. M., & Hutchison, A. (2020). Exploring human-companion animal interaction in families of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(8), 2793–2805. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04390-x

- Ellis, J. J. (2022). Feline Behavioral Assessment. In B. A. DiGangi, V. A. Cussen, P. J. Reid, & K. A. Collins (Eds.), Animal behavior for shelter veterinarians and staff (pp. 384–403). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119618515.ch15

- Elsabbagh, M., Divan, G., Koh, Y. J., Kim, Y. S., Kauchali, S., Marcín, C., Montiel-Nava, C., Patel, V., Paula, C. S., Wang, C., Yasamy, M. T., & Fombonne, E. (2012). Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism Research, 5(3), 160–179. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.239

- Grandgeorge, M., Gautier, Y., Bourreau, Y., Mossu, H., & Hausberger, M. (2020). Visual attention patterns differ in dog vs. cat interactions with children with typical development or autism spectrum disorders. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2047. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02047

- Griffin, K. E., John, E., Pike, T., & Mills, D. S. (2022). What will happen to this dog? A qualitative analysis of rehoming organisations’ pre-adoption dog behaviour screening policies and procedures. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 8, 796596. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2021.796596

- Hart, L. A., Thigpen, A. P., Willits, N. H., Lyons, L. A., Hertz-Picciotto, I., & Hart, B. L. (2018). Affectionate interactions of cats with children having autism spectrum disorder. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 5, 39. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2018.00039

- Hirvikoski, T., Mittendorfer-Rutz, E., Boman, M., Larsson, H., Lichtenstein, P., & Bölte, S. (2016). Premature mortality in autism spectrum disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry, 208(3), 232–238. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.160192

- Keville, S., De Vita, S., & Ludlow, A. K. (2022). Mothers’ reflections on cat ownership for a child with autism spectrum disorder during COVID-19. People and Animals: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 5(1), 8. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/paij/vol5/iss1/8

- Koukourikos, K., Georgopoulou, A., Kourkouta, L., & Tsaloglidou, A. (2019). Benefits of animal assisted therapy in mental health. International Journal of Caring Sciences, 12(3), 1898–1905.

- Kwon, J. Y., Lee, B. H., Mun, K. H., & Jung, J. S. (2015). A study on the effects of using an eco-friendly cat robot to treat children with autism spectrum disorder. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, 8(23), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.17485/ijst/2015/v8i23/79327

- Kwon, J. Y., Mun, K. H., Lee, B. H., Jung, J. S. (2014). Developing an initial model of cat robot utilizing an eco-friendly materials for the use of early treatment of children with autism spectrum disorder. PECCS 2014 - Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Pervasive and Embedded Computing and Communication Systems.

- Lamontagne, A., Johnson, R. A., Carlisle, G. K., Lyons, L. A., Bibbo, J. L., Koch, C., & Osterlind, S. J. (2020). Efficacy of the feline temperament profile in evaluating sheltered cats for adoption into families of a child with autism spectrum disorder. Animal Studies Journal, 9(2), 21–55. https://ro.uow.edu.au/asj/vol9/iss2/3

- Lau, B. Y., Leong, R., Uljarevic, M., Lerh, J. W., Rodgers, J., Hollocks, M. J., South, M., McConachie, H., Ozsivadjian, A., Van Hecke, A., Libove, R., Hardan, A., Leekam, S., Simonoff, E., & Magiati, I. (2019). Anxiety in young people with autism spectrum disorder: Common and autism-related anxiety experiences and their associations with individual characteristics. Autism, 24(5), 1111–1126. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361319886246

- Lee, B. H., Jang, J. Y., Mun, K. H., Kwon, J. Y., Jung, J. S. (2014). Development of therapeutic expression for a cat robot in the treatment of autism spectrum disorders. ICINCO 2014 - Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Informatics in Control, Automation and Robotics.

- Lee, J. G., Lee, B. H., Jang, J. Y., Kwon, J. Y., Mun, K. H., & Jung, J. S. (2017). Study on cat robot utilization for treatment of autistic children. International Journal of Humanoid Robotics, 14(2), 1750001. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219843617500013

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- London, M. D., Mackenzie, L., Lovarini, M., Dickson, C., & Alvarez-Campos, A. (2020). Animal assisted therapy for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: Parent perspectives. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(12), 4492–4503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04512-5

- Mun, K. H., Kwon, J. Y., Lee, B. H., & Jung, J. S. (2014). Design developing an early model of cat robot for the use of early treatment of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). International Journal of Control and Automation, 7(11), 59–74. https://doi.org/10.14257/ijca.2014.7.11.07

- Nieforth, L. O., Schwichtenberg, A., & O’Haire, M. E. (2021). Animal-assisted interventions for autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review of the literature from 2016 to 2020. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-021-00291-6

- O’Haire, M. (2017). Research on animal-assisted intervention and autism spectrum disorder, 2012–2015. Applied Developmental Science, 21(3), 200–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2016.1243988

- Parenti, L., Foreman, A., Meade, B. J., & Wirth, O. (2013). A revised taxonomy of assistance animals. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 50(6), 745–756. https://doi.org/10.1682/JRRD.2012.11.0216

- Purewal, R., Christley, R., Kordas, K., Joinson, C., Meints, K., Gee, N., & Westgarth, C. (2017). Companion animals and child/adolescent development: A Systematic review of the evidence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(3), 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14030234

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2020). NVivo. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- Reynolds, A. M., Soke, G. N., Sabourin, K. R., Hepburn, S., Katz, T., Wiggins, L. D., Schieve, L. A., & Levy, S. E. (2019). Sleep problems in 2- to 5-year-olds with autism spectrum disorder and other developmental delays. Pediatrics, 143(3), e20180492. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-0492

- RSPCA. (2022). What is an assistance animal. https://kb.rspca.org.au/knowledge-base/what-is-an-assistance-animal/

- Sargsyan, A. (2021). Animal assistants in healthcare. American Nurse Today. https://www.myamericannurse.com/animal-assistants-in-healthcare/

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/m18-0850

- Valiyamattam, G. J., Katti, H., Chaganti, V. K., O’Haire, M. E., & Sachdeva, V. (2020). Do animals engage greater social attention in autism? An eye tracking analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 727. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00727

- Ward, A., Arola, N., Bohnert, A., & Lieb, R. (2017). Social-emotional adjustment and pet ownership among adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Communication Disorders, 65, 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2017.01.002