Abstract

Adults with ADHD experience a wide range of difficulties in daily life, and RNs and other healthcare professionals need to know how to support them. The aim was to conduct a systematic review of which selfcare strategies adults with ADHD use and need in order to manage daily life. A literature review based on the PRISMA model was performed, and seven articles with a qualitative design were found. Data were analyzed with thematic analysis. The analysis generated one major theme Enabling ways to manage the consequences of disability in daily life based on three subthemes; Establishing ways of acting to help yourself, Finding encouraging and helping relationships, and Using external aids for managing daily life. Professionals may benefit from knowing about these selfcare strategies when meeting people with ADHD.

Introduction

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is regarded as an inherent disability. The main symptoms include: inattention, lack of concentration, restlessness, impulsivity and hyperactivity (American Psychological Association, Citation2013). Adults with ADHD are a heterogeneous group of individuals with a wide range of needs for treatment and support for managing daily life. Based on their diagnosis of ADHD, the individuals may experience difficulties with their executive functions e.g., memory, organizing their lives, and/or planning and performing activities in daily life (Arellano-Virto et al., Citation2021; Bjerrum et al., Citation2017; Brown, Citation2009). The individuals may also experience difficulties when relaxing and doing nothing, and it may affect their mood and ability to sleep (Bjerrum et al., Citation2017; Friedrichs et al., Citation2012; Gjervan et al., Citation2012). There is insufficient knowledge about how healthcare professionals, e.g., registered nurses (RN), can support adults with ADHD to cope with daily life. Developing interventions that focus on selfcare strategies for managing the vicissitudes of life are thus needed. Information about such useful strategies needs to be collected from those who themselves have ADHD.

The prevalence for ADHD in adults has been estimated to be about 2%–5% (Fayyad et al., Citation2007; Simon et al., Citation2009). Furthermore, the prevalence for ADHD is predicted to rise (Dalsgaard, Citation2013) as has been shown both in recent studies in Sweden (Polyzoi et al., Citation2018) and in the US (Zhu et al., Citation2018). This increase is mainly explained by changes in the diagnostic criteria that have opened up for a broader interpretation of the criteria (Dalsgaard, Citation2013; Zhu et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, ADHD is often linked with comorbid disorders such as anxiety, mood or substance use disorders (Sobanski, Citation2006; Wilens et al., Citation2002). There are, however, many adults with ADHD who do not have any comorbid conditions.

Research about treatment methods recommended for patients with ADHD have mostly focused on medical treatment, which have shown to lead to a reduction in the core symptoms of ADHD (De Crescenzo et al., Citation2017; Safren et al., Citation2010; Sater, Citation2022; Weiss et al., Citation2010). Non-pharmacological interventions, e.g., Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) tailored for ADHD, mindfulness exercises or interventions focusing on organizing, prioritizing and time management in daily life, can either be used as a complement to pharmacological treatment or as a standalone intervention (De Crescenzo et al., Citation2017; Poissant et al., Citation2019; Sater, Citation2022).

The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare recommend psychoeducation, memory training, cognitive facilities, housing support and/or medical treatment in their guidelines (Socialstyrelsen, Citation2014). These are in line with the guidelines stipulated by the European Network Adult ADHD (ENAA), which also state the need for a multimodal and multidisciplinary approach when treating the target group (Kooij et al., Citation2019). A collaboration between patients, relatives to people with ADHD and professionals in social welfare, school and healthcare is vital in order to enhance outcomes. Furthermore, strategies for support and treatment should be carried out for a long period of time (Socialstyrelsen, Citation2014). Different healthcare professionals, with varying competences and skills, are needed for meeting the requirements of the treatment methods, and one category of these is registered nurses (RN).

RNs working in psychiatric contexts use several different caring actions when supporting people with ADHD. Their focus is on enabling patients to become more independent and autonomous, guiding them to manage their disability and its consequences in daily life. RNs need guidelines and customized tools themselves to be able to use these caring actions to support patients to maintain and develop their abilities and level of functioning. The care could become more adapted by using a person-centred approach in these caring actions (Ekman et al., Citation2011). The aim is for the person to be more involved in their own care, which can increase their satisfaction and understanding of the care provided. It can also reduce the risk of the person behind the diagnosis being forgotten (Ekman et al., Citation2011). Interpersonal continuity, a satisfactory emotional climate and social interaction are reported as helping factors when patients within psychiatric care were interviewed (Denhov & Topor, Citation2012), which is in line with the interventions performed by RNs.

No articles focusing on caring interventions toward adults with ADHD were found when searching the literature. Additionally, a search in the Cochrane library was also performed to locate review articles related to the types of interventions or strategies that are provided for supporting daily life for people with ADHD from their own perspective, and also from that of RNs and other healthcare professionals, but none were found. Furthermore, only a few articles were found when searching literature in other databases. We thus decided to conduct a systematic review based on the perspective of the adults with ADHD in order to contribute to the development of interventions and strategies useful for them to manage daily life.

Objectives

The aim of the present study was to conduct a systematic review of the selfcare strategies adults with ADHD use and need in order to manage daily life.

Methods

Design

The present study was a systematic literature review, based on the guidelines of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement (Page et al., Citation2021), (Checklist PRISMA 2020 is available as supplementary material). PRISMA is used as a support when reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses, guided by an evidence-based minimum set of items. PRISMA is primarily used to assess the benefits and harms of healthcare interventions.

Eligibility criteria

Articles were selected in which the participants were diagnosed with ADHD (F90.0B-F90.0X)(ICD-10,10, Citation2022) from 18 years of age and above. The articles had to be written in English and published between January 2000 and February 2022, and include suggestions for interventions and/or selfcare strategies for managing daily life. Articles with a quantitative research approach or integrative or systematic reviews were excluded. Furthermore, articles that focused solely on staff experiences of interventions and treatments were also excluded.

Search strategy

Searches were made in three computerized databases, i.e. CINAHL Plus, PsycINFO and PubMed. These databases were considered as suitable due to their nursing-related content. A hand search was also performed in the reference lists of the articles assessed for eligibility, and thus a total of 80 articles were assessed for reading in full. The databases were searched on two occasions: first in June 2019, and second in February 2022.

The search was divided into three major themes: nurse/healthcare professionals, ADHD and caring actions. Different synonyms and truncated terms (“*”) were used to find as many combinations of these themes as possible ( shows an example from CINAHL Plus).

Table 1. CINAHL Plus. Searchchart.

Selection process

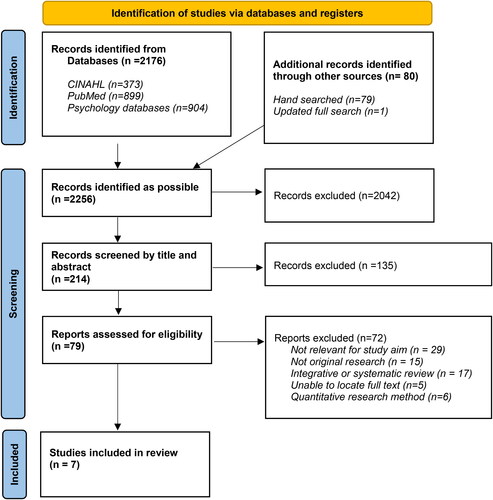

Articles that were deemed to be eligible for review were screened by three of the authors (PB, MR, ABG). All possible articles from the databases (CINAHL Plus, PsycINFO and PubMed) and the reference lists were identified in the first step (n = 2256). Articles, the titles of which did not appear to be relevant, were removed (n = 2042). Screenings were made based on the title and abstract in the second step (n = 214). These articles were divided for screening between three of the authors, so that each article was evaluated by at least two authors independently of each other. The exclusion of articles in this step was based on duplicates, non-adult study participation, non-empirical studies, or aim not in line with present study (n = 135). Eighty articles remained after the second step. The reference lists in these articles were searched by hand for further results and 13 articles were included. These were all removed later due to duplication. Overview of search chart, see .

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 Flow diagram. From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/.

The remaining articles (n = 80) were assessed as eligible and were all read in full by the first author and two of the other authors. Articles were excluded when they were not in line with the aim of the present study, were not original research, were integrative or systematic reviews, had a quantitative research method or were not available in full text versions. Finally, seven articles were included in the present study.

Data collection process

All data relevant to the aims of the study were extracted from the articles and compiled into a data set by the first author (PB). This data set consisted of possible caring interventions for adults with diagnosed ADHD, and also data from the study participants identified as helpful interventions/support measures in their daily lives. The data set was sorted and compared by three of the authors (PB, MR, ABG) independently and when contradictions, questions or uncertainties arose between the authors, further assessment was made to ensure that the data corresponded to the objectives of the study in order to reduce the risk of ambiguity in data occurring.

The articles selected to be included in the present study have been reviewed for quality, by a template designed by Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU) “Assessment of studies with qualitative methodology” and translated to English (Larsson-Lund et al., Citation2022). Questions 1-6 were used for the evaluation. Four of the articles was judged to be of high quality and three of medium quality (see ).

Table 2. Included studies.

The quality of the articles was judged for the following:

The basis of consistency between the philosophical attitude/theory selected and the methodology presented. In five cases, the aim and questions were judged to be related to the chosen theory/philosophical attitude. In two of the cases, it was estimated to be unclear.

The selection was judged to be relevant and well-described for both recruitment and participants in all the articles. No serious doubt that could have affected the reliability of the data collection emerged.

In terms of the analysis methods in the articles, it emerged that there were no references to the referred analysis method in one case, which was considered to be a shortcoming. In another case, it was unclear whether interpretations were validated by more than one coauthor.

The issue that emerged with the greatest ambiguity was the researchers’ background, competence, and relationship to the study participants. This was the category that appeared most obscure and, in three cases, even poorly described. However, the assessment was made that the effect on reliability did not give rise to any serious deficiencies.

Synthesis method

Data was analyzed using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). This method involves a 6-phase process to reveal repeated patterns of meaning in the data and was considered as appropriate for answering the research questions. The first phase included reading and becoming familiar with the text, making notes during the reading about what the data contains and what is interesting about the data. In phase two, the notes are converted and organized into the first initial codes (analytic entities). The codes are sorted in the search for potential themes and a code can be sorted into as many themes as it fits into. The third phase contains the interpretative analysis of the data; themes are checked in relation to the extracted codes of the entire data set, and this process goes on generating a “thematic map”. In the last three phases, all themes are then looked at for further refinement and to identify the essence of each theme. According to Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), it is important that themes ultimately provide an interesting account of the data and through analysis in a concise, logical, non-repetitive and coherent manner.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

Seven articles using a qualitative study design were found using the systematic search. Four of the included studies originated from the USA and three from Europe (The Netherlands and Sweden). A total of 88 participants (44 male and 44 female) were interviewed in the different studies ( Included studies).

Results of syntheses

One major theme Enabling ways to manage the consequences of disability in daily life, and three subthemes Establishing ways of acting to help yourself, Finding encouraging and helping relationships, and Using external aids for managing daily life were identified.

Enabling ways to manage the consequences of disability in daily life

Living with ADHD is not always easy. The consequences of their disability become part of daily life and the ways to manage them vary from person to person. Knowledge and information provide security and opportunities to understand and seek the right help. Supportive and helpful relationships with others, family, friends, or healthcare professionals are highlighted as important facilitators. Having someone, who shares their daily lives and the ups and downs they experience and who understands and listens, eases the burden of difficulties, while external aids make daily life easier in a practical way.

Establishing ways of acting to help yourself

When parents or healthcare professionals did not provide information about ADHD, the participants have obtained the information themselves via friends, information materials or the internet (Waite & Tran, Citation2010). Information via the internet is described as both good and bad, where sites run by recognized national organizations such as “The National Resource Centre on ADHD” were placed in the good category and sites with negative stories in the bad category (Meaux et al., Citation2009). Self-awareness was described as a way to learn how to live with ADHD. Two studies reported that being able to take responsibility for one’s own learning about ADHD was important and helped the participants to gain self-awareness (Meaux et al., Citation2009; Waite & Tran, Citation2010).

Underlying deficiencies in the provision of information and a lack of openness from the staff in communication, or the shame of having difficulties relating to their diagnosis meant that many were cautious talking about their difficulties in daily life, which is why they did not seek any help from healthcare professionals or others. Keeping their difficulties as secrets emerged as obstacles in gaining insight and understanding (Meaux et al., Citation2009).

Participants described that learning from experiences, being responsible and learning from the consequences of their own actions were positive strategies that were considered to contribute to self-learning. In order to remember and as reminders to themselves, the participants described that talking aloud, i.e. named as “self-talk” was considered helpful (Meaux et al., Citation2009).

Staying active during daytime and having a schedule to follow was considered helpful both for keeping routines and structure, and for not returning to earlier behaviors (Kronenberg et al., Citation2015). Removing oneself from distractions or removing the distractive object was also thought of as helpful (Meaux et al., Citation2009). The participants describe that adapting to one’s circumstances was needed in order to achieve good planning, for example, activities took place at the time of day that worked best for them. Due dates or times were set days or hours in advance as reminders so as to get things done (Waite & Ivey, Citation2009).

Finding encouraging and helping relationships

Interpersonal and professional relationships were seen to be essential for helping people with ADHD to manage daily life. The participants describe relationships with parents and friends as supportive and helpful when coping with the symptoms of ADHD. Furthermore, the participants identified teachers and tutors, i.e. academic support and disability services were experienced as supportive (Meaux et al., Citation2009). Restoring broken relationships with relatives and healthcare professionals were shown to be a primary goal for the participants in the study by Kronenberg et al. (Citation2015). Maintaining relationships was experienced as difficult and took a lot of energy, even though they were perceived as helpful to support their daily lives. Having a relationship also entailed having someone that they were accountable to and to whom they could turn when needing help (Meaux et al., Citation2009). Participants described that daily life could be a struggle with loneliness and hopelessness and that meeting people in similar situations was important and was considered to generate strength and energy (Björk et al., Citation2021). Being diagnosed with ADHD was experienced as a change in daily life. It gave the participants insights into and explanations about their experiences making it possible to open up about their difficulties (Zwennes & Loth, Citation2019). The knowledge that others had the same difficulties made the participants more comfortable with themselves and feelings of being embarrassed were reduced. (Waite & Ivey, Citation2009). By sharing their experiences, the participants could instead gain a greater understanding from those they had social contacts with (Kronenberg et al., Citation2015).

The relationships with healthcare professionals were experienced as functional when there was an active collaboration with ongoing support and guidance for helping with, for example, the adjustment of medications (Meaux et al., Citation2006). Non-helpful relationships with healthcare professionals could entail experiences of limited trust in them. This could result in patients having adverse feelings about their medication and thus taking their medication in a way that was not prescribed by their physician (Meaux et al., Citation2009).

The participants in a study by Waite and Tran (Citation2010) expressed thoughts about the difficulties of establishing a good working relationship with their therapist, especially if they needed understanding from more than one perspective, e.g., ADHD and other social and cultural positions. Differences and a perceived lack of sensitivity regarding ethnic, gender or lifestyle, made it more difficult to create and maintain a working relationship. Feelings of being abandoned by healthcare professionals may arise when support was insufficient, reported in places where the staff did not have a health-promoting and person-centred approach (Björk et al., Citation2021).

Using external aids for managing daily life

The use of external aids emerged as one of the areas that the participants were asked about in terms of managing daily lives. Medication, cell phone alarms, clocks, and planning calendars were the most common aids, but also friends and parents were used to help them remember or remind them of due dates for assignments for college studies or meetings or for keeping the structure of daily life, for example, in terms of eating.

Using alarms and reminders on their phones were often cited as the most important support for remembering times, being on time and being able to stay organized. Using different sounds for the alarm or placing the alarm clock at some distance were also considered as good strategies (Meaux et al., Citation2009).

The participants described that medication were the first and only help they were offered since they felt that healthcare professionals did not know of anything else (Waite & Tran, Citation2010). Medication was seen as something positive, it helped to improve their level of concentration and to being able to maintain focus, which led to better study results and to completing study tasks in time (Meaux et al., Citation2006). On the other hand, many of the participants also expressed a concern about medication, having thoughts of becoming addicted and instead tried different complementary medical strategies (Waite & Tran, Citation2010).

Discussion

The present study aimed to identify self-care strategies, which adults with ADHD need to manage their daily lives. Seven articles addressing the topic were found in a systematic review of the literature, and the major theme Establishing ways to manage the consequences of disability in daily life was generated, which emphasized independence, relationships with others and the need for external aids.

In order to find ways to help themselves, adults with ADHD used a variety of approaches, with the intention of gaining deeper insights and knowledge both in general about ADHD and specifically about themselves to be able to make it easier to manage daily life. Information concerning the ADHD diagnosis and its impact on daily life was described in the present study as being important in order to be independent and to manage daily life. A survey including different subjects was performed where adults with ADHD rated ADHD-related information for the purpose of developing a smartphone-based app. The participants in this study considered that important topics about which they needed more information included executive functions, how to deal with procrastination, how to stay focused, time and task management or improving organization (Seery et al., Citation2022). Few of the participants in this study stated that they received information from their healthcare professionals. This concurs with the findings in a study by Aoki et al. (Aoki et al., Citation2020), in which newly diagnosed adults primarily sought information from pamphlets they had picked up in the waiting room, books about ADHD or on the internet. Similar results have been found by Bussing et al. (Bussing et al., Citation2012) who investigated pathways to knowledge about ADHD in young people with ADHD and their parents. They found that young people used fewer sources when seeking information and usually turned to the internet, social networks, teachers/school or television. On the other hand, parents used more sources for gaining information including, healthcare professionals, written information and the aforementioned.

Gaining self-awareness was seen to be important. A lack of self-awareness about their difficulties and disabilities, due to having ADHD, was seen to hinder them from being able to assess their need for help. For people with ADHD, this could be due to their disability in their executive functioning as shown in previous studies (Manor et al., Citation2012; Steward et al., Citation2017), where patients with ADHD often misjudged their actual abilities and need of help. This could lead to them not being able to manage their activities in daily life. By providing information and tools to a person with ADHD, the RN’s or other healthcare professionals can increase the individual’s independency and ability to manage their daily life. Healthcare professionals thus need to gain knowledge of the executive difficulties that a person with ADHD may have. They would also need to be aware of and up to date as to where current knowledge for the patients is accessible, for example, via the internet, patient associations or various types of patient educations.

It is important for people with ADHD to have encouraging and helpful relationships. We found that the relationship includes receiving support, guidance, or information, but relationships could also sometimes be something demanding and took a lot of energy. Relationships with healthcare professionals are rarely described in the articles in the present study and appeared ambiguous. The relationship between the individual and their healthcare professional is to some extent described as nonfunctional because the professionals only ask about the medication and do not provide any opportunities for further discussions. The individual then may choose to have as little contact with the healthcare professionals as possible. A relationship that works was instead described as active and characterized by mutuality between the healthcare professionals and the person with ADHD. This helped the latter to better manage her/his life better and to strengthen her/his ability to self-care. A functional relationship, from a nursing and person-centred perspective (Ekman et al., Citation2011), needs to be characterized by trust and cooperation that strengthens the relationship between the patient and the healthcare professional. This can support the development of the patient’s courage to open up and share their thoughts and experiences about their problems. This was further shown in a study by Adnøy Eriksen et al. (Adnøy Eriksen et al., Citation2014), where the participants describe connectedness with the professionals as being detached, being cautious or being open and trusting. It is important as a RN or other healthcare professional to take time and actively listen to the patient in order to be able to understand and then provide treatments that lead to an improvement in the patient’s ability to take care of themselves. This is in line with a study by Malone (Citation2003) who maintained that RNs need to develop different types of relationships. RNs or other healthcare professionals need to see the person behind the difficulties and give support and guidance that is suitable for each individual person in order to be able to assist them to develop and use their selfcare strategies. Taking the time to build a functioning and trusting relationship will benefit all parties.

The adults with ADHD in the present study often spoke of turning to external aids to be able to manage daily life. The use of different types of reminders and tools for creating structure in life was considered as one of the most important aids in organizing daily life. External aids could be planners, schedules, handheld computers, mobile phones or friends and parents. Ek and Isaksson (Citation2013) found that the use of other people as an initiator or a reminder was beneficial for enabling them to perform everyday activities. Medication as an external aid was mentioned in terms of gaining abilities to concentrate and maintain focus, which is in line with research about ADHD medication treatment (De Crescenzo et al., Citation2017; Sater, Citation2022). Patients’ attitudes toward medication have a major impact on whether they will continue to use medication. This has been shown in a review by McCarthy (McCarthy, Citation2014), where the conclusion is that healthcare professionals have a great responsibility for providing information about diagnosis and drug treatment, but also for supporting the patient and their families and actively working to involve them in the prescribed treatments. RNs and other healthcare professionals need to see it as their task to provide the support that the patient needs in order to be able to decide whether drug treatment is the best option, or if other external aids would be more suitable.

Methodological considerations

The researcher is part of the analysis in qualitative research, which inevitably leads to the analysis being carried out with the commitment and prior knowledge of the researcher. It is thus important that the analysis is carried out in a credible manner and with transparency in the process. Searches for articles were performed more than once as the data collection only revealed a small number of articles that corresponded to the aim for the present study. This may be seen as a limitation, but also demonstrates a knowledge gap. However, based on the researchers’ previous experience and with the support of other research, the themes that were generated, despite the limitations in the selection as stated above, can be considered to strengthen the credibility.

Other strengths in our study are that we have followed the PRISMA step-by-step guide closely. This can facilitate other researchers to conduct a replication of this study. A further strength is that several authors read and reviewed the articles and had a consensus discussion regarding the generated themes.

The data collection only revealed a small number of studies corresponding to the aim of the study. These have been carried out in the western world, either in college or healthcare settings with participation from both men and women. They thus only reflect a limited context, which can be seen as a weakness in terms of transferability to other contexts. However, as the focus of the study is on self-help strategies for managing one’s daily life, it should be possible to transfer the results to other contexts. Further research is needed about the experiences of adults with ADHD concerning which interventions and selfcare strategies that they believe they need to cope with daily life. This can help to strengthen the transferability to other contexts.

Conclusion

A conclusion from this study is that adults with ADHD used a variety of self-care strategies in order to find ways to help themselves. Gaining deeper insights and knowledge in general about ADHD and about themselves enabled them to better manage their daily life. Encouraging and helping relationships and the use of external aids was considered important as a help for organizing daily life. RNs and other healthcare professionals can benefit from knowledge about these self-care strategies when meeting people with ADHD.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (31.5 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adnøy Eriksen, K., Arman, M., Davidson, L., Sundfør, B., & Karlsson, B. (2014). Challenges in relating to mental health professionals: Perspectives of persons with severe mental illness. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 23(2), 110–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12024

- American Psychological Association. (2013). APA Dictionary of Clinical Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/13945-000

- Aoki, Y., Tsuboi, T., Furuno, T., Watanabe, K., & Kayama, M. (2020). The experiences of receiving a diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder during adulthood in Japan: A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 373. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02774-y

- Arellano-Virto, P. T., Seubert-Ravelo, A. N., Prieto-Corona, B., Witt-González, A., & Yáñez-Téllez, G. (2021). Association between psychiatric symptoms and executive function in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychology & Neuroscience, 14(4), 438–453. https://doi.org/10.1037/pne0000271

- Bjerrum, M. B., Pedersen, P. U., & Larsen, P. (2017). Living with symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adulthood: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 15(4), 1080–1153. https://doi.org/10.11124/jbisrir-2017-003357

- Björk, A., Rönngren, Y., Hellzen, O., & Wall, E. (2021). The importance of belonging to a context: A nurse-led lifestyle intervention for adult persons with ADHD. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 42(3), 216–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2020.1793247

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brown, T. (2009). ADD/ADHD and impaired executive function in clinical practice. Current Attention Disorders Reports, 1(1), 37–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12618-009-0006-3

- Bussing, R., Zima, B. T., Mason, D. M., Meyer, J. M., White, K., & Garvan, C. W. (2012). ADHD knowledge, perceptions, and information sources: Perspectives from a community sample of adolescents and their parents. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 51(6), 593–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.03.004

- Dalsgaard, S. (2013). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 22(S1), 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-012-0360-z

- De Crescenzo, F., Cortese, S., Adamo, N., & Janiri, L. (2017). Pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment of adults with ADHD: A meta-review. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 20(1), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2016-102415

- Denhov, A., & Topor, A. (2012). The components of helping relationships with professionals in psychiatry: Users’ perspective. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 58(4), 417–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764011406811

- Ek, A., & Isaksson, G. (2013). How adults with ADHD get engaged in and perform everyday activities/How adults with ADHD get engaged in and perform everyday activities. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 20(4), 282–291. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2013.799226

- Ekman, I., Swedberg, K., Taft, C., Lindseth, A., Norberg, A., Brink, E., Carlsson, J., Dahlin-Ivanoff, S., Johansson, I.-L., Kjellgren, K., Lidén, E., Öhlén, J., Olsson, L.-E., Rosén, H., Rydmark, M., & Sunnerhagen, K. S. (2011). Person-centered care—Ready for prime time. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 10(4), 248–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2011.06.008

- Fayyad, J., de Graaf, R., Kessler, R., Alonso, J., Angermeyer, M., Demyttenaere, K., de Girolamo, G., Haro, J. M., Karam, E. G., Lara, C., Lépine, J. P., Ormel, J., Posada-Villa, J., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Jin, R. (2007). Cross-national prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 190, 402–409. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.106.034389

- Friedrichs, B., Igl, W., Larsson, H., & Larsson, J. O. (2012). Coexisting psychiatric problems and stressful life events in adults with symptoms of ADHD–A large Swedish population-based study of twins. Journal of Attention Disorders, 16(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054710376909

- Gjervan, B., Torgersen, T., Nordahl, H. M., & Rasmussen, K. (2012). Functional impairment and occupational outcome in adults with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 16(7), 544–552. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054711413074

- Poissant, H., Mendrek, A., Talbot, N., Khoury, B., & Nolan, J. (2019). Behavioral and cognitive impacts of mindfulness-based interventions on adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review. Behavioural Neurology, 2019, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/5682050

- ICD-10. (2022). Internetmedicin Göteborg AB. http://icd.internetmedicin.se/diagnos/

- Kooij, J. J. S., Bijlenga, D., Salerno, L., Jaeschke, R., Bitter, I., Balázs, J., Thome, J., Dom, G., Kasper, S., Nunes Filipe, C., Stes, S., Mohr, P., Leppämäki, S., Casas, M., Bobes, J., Mccarthy, J. M., Richarte, V., Kjems Philipsen, A., Pehlivanidis, A., … Asherson, P. (2019). Updated European Consensus Statement on diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD. European Psychiatry: The Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 56, 14–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.11.001

- Kronenberg, L. M., Verkerk-Tamminga, R., Goossens, P. J. J., van den Brink, W., & van Achterberg, T. (2015). Personal recovery in individuals diagnosed with substance use disorder (SUD) and co-occurring attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 29(4), 242–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2015.04.006

- Larsson-Lund, M., Pettersson, A., & Strandberg, T. (2022). Team-based rehabilitation after traumatic brain injury: A qualitative synthesis of evidence of experiences of the rehabilitation process. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 54, jrm00253. https://doi.org/10.2340/jrm.v53.1409

- Malone, R. E. (2003). Distal nursing. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 56(11), 2317–2326. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00230-7

- Manor, I., Vurembrandt, N., Rozen, S., Gevah, D., Weizman, A., & Zalsman, G. (2012). Low self-awareness of ADHD in adults using a self-report screening questionnaire. European Psychiatry: The Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 27(5), 314–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.08.013

- McCarthy, S. (2014). Pharmacological interventions for ADHD: How do adolescent and adult patient beliefs and attitudes impact treatment adherence? Patient Preference and Adherence, 8(default), 1317–1327. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=edsdoj&AN=edsdoj.76fe7077ee274856b9ec231fe6ee5f37&lang=sv&site=eds-live&custid=ns071514

- Meaux, J. B., Green, A., & Broussard, L. (2009). ADHD in the college student: A block in the road. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 16(3), 248–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2008.01349.x

- Meaux, J. B., Hester, C., Smith, B., & Shoptaw, A. (2006). Stimulant medications: A trade-off? The lived experience of adolescents with ADHD. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing: JSPN, 11(4), 214–226. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6155.2006.00063.x

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, L., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, P. M., Bossuyt, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J. M., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L. A.., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10(89). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4

- Polyzoi, M., Ahnemark, E., Medin, E., & Ginsberg, Y. (2018). Estimated prevalence and incidence of diagnosed ADHD and health care utilization in adults in Sweden – A longitudinal population-based register study [Artikel]. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 14, 1149–1161. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S155838

- Safren, S. A., Sprich, S. E., Cooper-Vince, C., Knouse, L. E., & Lerner, J. A. (2010). Life impairments in adults with medication-treated ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 13(5), 524–531. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054709332460

- Sater, P. A. M. (2022). Focus on function: Therapies for adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAAPA: official Journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants, 35(2), 42–47. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.JAA.0000803632.72370.24

- Seery, C., Wrigley, M., O'Riordan, F., Kilbride, K., & Bramham, J. (2022). What adults with ADHD want to know: A Delphi consensus study on the psychoeducational needs of experts by experience [article]. Health Expectations: An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy, 25(5), 2593–2602. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13592

- Simon, V., Czobor, P., Balint, S., Meszaros, A., & Bitter, I. (2009). Prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: Meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 194(3), 204–211. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.048827

- Sobanski, E. (2006). Psychiatric comorbidity in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 256(S1), i26–i31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-006-1004-4

- Socialstyrelsen. (2014). Stöd till barn, ungdomar och vuxna med adhd - Ett kunskapsstöd. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/kunskapsstod/2014-10-42.pdf

- Steward, K. A., Tan, A., Delgaty, L., Gonzales, M. M., & Bunner, M. (2017). Self-awareness of executive functioning deficits in adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 21(4), 316–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054714530782

- Waite, R., & Ivey, N. (2009). Unveiling the mystery about adult ADHD: One woman’s journey. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 30(9), 547–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840902741989

- Waite, R., & Tran, M. (2010). Explanatory models and help-seeking behavior for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among a cohort of postsecondary students. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 24(4), 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2009.08.004

- Weiss, M. D., Gibbins, C., Goodman, D. W., Hodgkins, P. S., Landgraf, J. M., & Faraone, S. V. (2010). Moderators and mediators of symptoms and quality of life outcomes in an open-label study of adults treated for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71(4), 381–390. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.08m04709pur

- Wilens, T. E., Spencer, T. J., & Biederman, J. (2002). A review of the pharmacotherapy of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Attention Disorders, 5(4), 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/108705470100500401

- Zhu, Y., liu, W., Li, Y., Wang, X., & Winterstein, A. G. (2018). Prevalence of ADHD in publicly insured adults. Journal of Attention Disorders, 22(2), 182–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054717698815.

- Zwennes, C. T. C., & Loth, C. A. (2019). “Moments of failure”: Coping with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, sleep deprivation, and being overweight: A qualitative hermeneutic–phenomenological investigation into participant perspectives. Journal of Addictions Nursing, 30(3), 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1097/JAN.0000000000000291.