Abstract

Implementing sensory approaches in psychiatric units has proven challenging. This multi-staged study involved qualitative interviews (n = 7) with mental health care staff in an acute psychiatric ward to identify the local factors influencing use of sensory approaches, and co-design implementation strategies with key stakeholders to improve their use. Using framework analysis, results revealed that the use of sensory approaches were hindered by: inadequate access to sensory resources/equipment; lack of time; lack of staff knowledge; and belief that sensory approaches are not effective or part of staff’s role. To address identified barriers a systematic theory-informed method was used to co-design implementation strategies to improve the use of sensory approaches.

Introduction

Sensory approaches are therapeutic interventions that use sensory experiences (such as sound, smell, taste, light, touch and movement) to optimise an individual’s physiological and emotional wellbeing through the use of sensory equipment/tools, environmental modifications and sensory activities (Sutton & Nicholson, Citation2011). The use of sensory approaches in psychiatric units are evidence-based interventions (Craswell et al., Citation2021) that are supported by Australian government policy and guidelines (Wright et al., Citation2022). Evidence has demonstrated that the use of sensory approaches with consumers in mental health care can reduce distress and agitation, improve emotional regulation, encourage the development of self-soothing strategies, and reduce the use of seclusion and restraint in psychiatric units (Craswell et al., Citation2021; Scanlan & Novak, Citation2015). Despite the established benefits of using sensory approaches in psychiatric units, there is evidence that mental health services are failing to successfully implement and sustain their use (Hamilton et al., Citation2016; Wright, Citation2017; Wright et al., Citation2020). While emerging research has described the factors influencing the implementation of sensory approaches in psychiatric units (Azuela, Citation2019; Machingura et al., Citation2021; Wright et al., Citation2020; Wright et al., Citation2021), limited research has considered tailoring implementation strategies to overcoming the barriers (Dawson et al., Citation2022). The aim of this research is to identify the barriers to the use of sensory approaches in one psychiatric ward and to co-design a theoretically-informed, tailored implementation strategy to improve the use of sensory approaches.

Background

Sensory approaches commonly utilised in psychiatric units include sensory rooms/spaces, sensory groups, sensory kits/trolleys, weighted modalities (e.g. weighted blankets, toys, or vests), aromatherapy, stress balls, fidget items, and rocking chairs (O’Sullivan & Fitzgibbon, Citation2018). Sensory rooms or comfort rooms in psychiatric units are designed as calming spaces with an array of sensory equipment such as rocking chairs, beanbag chairs, light projectors and aromatherapy diffuser (Champagne, Citation2011) and their use their use has been found to decrease consumer’s arousal levels, anxiety, distress and agitation (Cheng et al., Citation2017; Novak et al., Citation2012). Sensory kits and/or trolleys are portable collections of sensory items or equipment that can be provided to consumers when a sensory room is not available allowing consumers to select personalised sensory tools to improve their emotional regulation (Martin & Suane, Citation2012). Items contained in sensory kits/trolleys include but are not limited to herbal teas, fidget items, stress balls, mindful colouring in books, therapy putty, sleep masks and ear plugs. Weighted modalities such as weighted blankets, weighted vests, or weighted toys can produce a calming or grounding feeling through stimulating the deep touch receptors (Champagne, Citation2018). The use of weighted modalities with consumers with mental health disorders have demonstrated benefits of improved sleep (Ekholm et al., Citation2020), reduction in the use of Pro re nata (PRN) medication and a reduction in anxiety (Eron et al., Citation2020).

An important aspect of using sensory approaches in mental health care is to work collaboratively with consumers to identify their individual sensory preferences and develop personalised sensory strategies to use when they feel distressed or agitated (Martin & Suane, Citation2012). This awareness can be achieved through exploration of sensory experiences, the use of sensory checklists such as personal safety plans (Lee et al., Citation2010), and the use of sensory assessments such as the Sensory Profile (Brown & Dunn, Citation2002). Personal safety plans identify an individual’s triggers and warning signs of distress, and sensory calming strategies (Chalmers et al., Citation2012). The Sensory Profile is a validated assessment used primarily by occupational therapists to identify an individual’s patterns of sensory processing which assist in determining optimal sensory strategies for an individual (Brown et al., Citation2001). The use of sensory approaches in psychiatric care is person-centred, trauma-informed and consistent with the Australian National Framework for Recovery Orientated Mental Health Services (O’Sullivan & Fitzgibbon, Citation2018).

Recovery orientated mental health services should support consumers to develop individualised strategies to self-manage distress and anxiety as an alternative to medication use (Dawson et al., Citation2022). Australian mental health guidelines recommend that psychiatric units have sensory spaces/options such as sensory rooms or sensory equipment available to consumers, and that staff collaboratively identify personalised calming strategies with consumers to reduce distress and arousal through using tools such as personal safety plans (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, Citation2017).

However, failed implementation of sensory approaches in psychiatric units has resulted in sensory rooms being poorly maintained or no longer used, with sensory equipment such as weighted blankets no longer available, and sensory kits/trolleys left unstocked or abandoned in storage cupboards (Bensemann, Citation2018; Wright et al., Citation2020; Wright et al., Citation2017). Consumers admitted to these psychiatric units are then left without access to sensory approaches to manage distress and anxiety. This has resulted in a gap between the evidence-based recommendations for the use of sensory approaches and its actual use in psychiatric units demonstrating an evidence-practice gap (Wright et al., Citation2022).

There is emerging research describing the barriers and facilitators of implementing sensory approaches in psychiatric inpatient units. Wright et al. (Citation2020) interviewed mental health clinicians (n = 15) and identified the following factors influencing the use of sensory approaches in psychiatric units: lack of social support from colleagues; concern regarding perceived risks; lack of sensory tools and equipment; and lack of belief that providing sensory approaches was part of their clinical role. Similarly, Machingura et al. (Citation2021) interviewed people with schizophrenia (n = 13) and occupational therapists (n = 11) about their views on using sensory approaches. They identified additional barriers including organisational concern about perceived risk, lack of accessible training, and lack of sensory resources. Other factors influencing implementation of sensory approaches identified in New Zealand psychiatric units include high acuity of patients admitted to the ward, lack of leadership from management, entrenched organisational culture related to use of seclusion and restraint, and fear of using sensory approaches as an alternative (Azuela, Citation2019). Recommendations to improve the use of sensory approaches include addressing concerns about perceived risks, providing increased education and training, and provision and maintenance of sensory equipment/tools (Machingura et al., Citation2021; Wright et al., Citation2020). In addition, it has been recommended that mental health services address the strong influence of clinicians’ peers (Wright et al., Citation2020) and focus on changing service culture to be more person-centred to achieve better outcomes for consumers (Machingura et al., Citation2021).

The barriers to the use of sensory approaches in psychiatric units have broadly been identified (Azuela, Citation2019; Machingura et al., Citation2021; Wright et al., Citation2020), however, it is emphasised that implementation strategies should be tailored to local context factors to maximise the success of implementation efforts in mental health settings (Girlanda et al., Citation2013). Implementation science theories, models and frameworks have been found to be useful in tailoring implementation strategies to improve clinical practice in health care (Michie et al., Citation2014; Nilsen & Birken, Citation2020). Only one study could be identified that used theoretical approaches to tailored implementation strategies to known barriers to improve the use of sensory approaches in mental health care (Dawson et al., Citation2022). The study conducted by Dawson et al. (Citation2022) focused on improving the use of weighted modalities as an alternative to PRN medication over a period of 4 months in a residential rehabilitation psychiatric unit utilising the COM-B model (capability, opportunity, motivation-behaviour), Theoretical Domain Framework (TDF) and realist evaluation to tailor implementation strategies. This study demonstrated an initial increase in PRN medication use in the first 3 months of implementation followed by a decrease in the second 3 months of implementation. Dawson et al. (Citation2022) found that the key to increasing the use of weighted modalities was making the modalities more available and accessible, and for clinicians to promote the consumer benefits of using weighted modalities to their colleagues. However, there has been no study conducted in an acute inpatient psychiatric unit that has used a theory-informed implementation strategy to address known barriers and to improve the use of a range of sensory approaches. In addition, to tailoring implementation strategies, a key element to achieving success in improving implementation of evidence-based practices is engagement with the local key stakeholders to identify the problem and co-design the implementation strategies (Graham et al., Citation2018).

Integrated Knowledge Translation (IKT) is a collaborative model where researchers work with knowledge users (e.g. managers, clinicians) from the initial identification of the problem to co-designing and evaluating the solution to implementation challenges (Gagliardi et al., Citation2016). Co-designing implementation strategies ensures that the chosen interventions are tailored to the local barriers and facilitators, the setting, and fit with existing work practices (Long et al., Citation2018). The current study was guided by the principles of Integrated Knowledge Translation (IKT) (Kothari et al., Citation2017). Prior to this study, key stakeholders working in the acute psychiatric unit had identified problems with the use of sensory approaches as an issue that needed to be addressed, selected the sensory approaches they wanted to focus on and had discussed how their use could be adapted to the local ward context. However, the barriers and enablers specific to the local context of the inpatient psychiatric unit were unknown and needed to be understood in order to co-design a tailored implementation strategy to address the barriers in the local ward.

The overall aim of this study was to identify the factors influencing the use of sensory approaches in an acute psychiatric ward and co-design a theoretically-informed, tailored implementation strategy to address identified barriers. The specific aims of this study were to:

explore the local barriers and enablers to the use of sensory approaches

explore recommendations to improve the use of sensory approaches in the local ward

co-design a tailored, theory-informed, multifaceted implementation strategy to increase the use of sensory approaches with consumers in one acute mental inpatient ward.

Methods

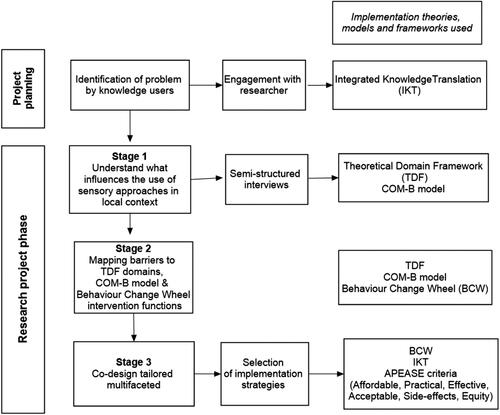

This study consisted of three stages using a multi-staged approach (as described by Fahim et al., Citation2020) to assess the barriers and subsequently co-design a tailored, theory-informed implementation strategy. The first stage of the project used qualitative methods to conduct semi-structured interviews informed by the Theoretical Domain Framework (TDF) to identify barriers, enablers, and recommendations for the use of sensory approaches in the local setting. Secondly, using Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) approach, identified barriers were mapped to COM-B (capability, opportunity, motivation-behaviour) model components, then to the BCW intervention functions to select potential implementation strategies most likely to improve the use of sensory approaches in the local context. Finally, a tailored multifaceted implementation strategy was co-designed with the local key stakeholder committee ensuring the strategies were feasible in the local context (see for description of project). The details of each stage are then described.

Figure 1. Models used for project planning and development of tailored implementation strategy. Adapted from: Porcheret et al. (Citation2014). Adapted with permission under Creative Commons licence: http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/.

This study was approved by ethical review boards of Queensland Health (HREC/17/QPCH/297) and The University of Queensland (#2017001711), Queensland, Australia.

Setting

The acute psychiatric inpatient unit in this study was in a major metropolitan hospital in Queensland, Australia. The unit consists of two wards, both with 30 adult acute inpatient beds including three to five psychiatric intensive care beds. Implementation of sensory approaches in the unit studied had involved installation of two sensory rooms one in each ward (in 2011), training in sensory approaches training for clinical staff (commenced in 2014 with two to three workshops per year), development of sensory kits (in 2015 and 2018) and prescription of weighted blankets by the unit’s occupational therapist (since 2017). One ward elected to participate in the study as clinicians had identified that the sensory room, sensory kits, and weighted blankets had become poorly maintained and were underutilised. The psychiatric ward chosen employed 40 clinical staff including medical officers, nursing staff, social workers, occupational therapists, peer support workers, and a recreation worker.

Stakeholder committee

A key stakeholder committee was established to oversee the project. Committee members consisted of: the ward’s nurse unit manager; Safewards’ nursing champions, inpatient consultant psychiatrist; professional lead occupational therapist; inpatient occupational therapist; community team leader; consumer/carer consultant; and the chief researcher (occupational therapist).

In this study, the key stakeholder committee worked collaboratively with the chief researcher to: 1) oversee the recruitment of participants for the semi-structured interviews; 2) provide expert knowledge relating to local factors influencing the use of sensory approaches in the local context; and 3) collaboratively identify implementation strategies that are acceptable, cost-effective, and practical within the local context and time frame of the proposed implementation project. (Graham et al., Citation2006).

Stage one: interviews

Research design

A qualitative description design as described by Sandelowski (Citation2000) was used to understand potential barriers, enablers and recommendations for the use of three specific sensory approaches in one acute psychiatric ward.

Participants

Participants were mental health clinicians and peer support workers recruited from the intervention ward. Purposive sampling was used to invite staff from different disciplines and with different levels of experience and seniority. Participation was voluntary and written consent gained prior to the interviews.

Data collection

Staff were invited to participate in a semi-structured individual interview at a time and place of their choosing. Interviews lasted approximately 45 min. The interviews were conducted by the first author (LW) who led the subsequent implementation project as it allowed her to gain in-depth understanding of the barriers and participants’ recommendations to improve the use of sensory approaches in the local context.

Interview guide

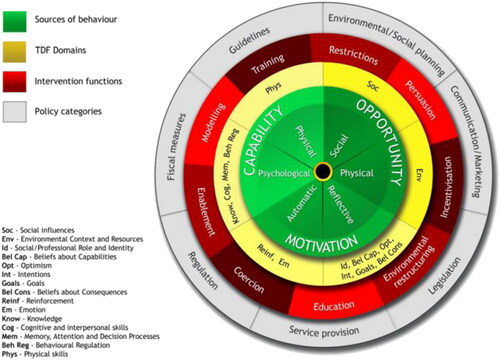

An interview guide was developed, based on the factors known to influence the use of sensory approaches identified in previous studies (Wright et al., Citation2020; Wright et al., Citation2021), and the domains and constructs from the TDF (Cane et al., Citation2012), and COM-B model (Michie et al., Citation2014). The TDF is an integrative framework based on theories of behaviour change and is used to assess barriers and facilitators for complex clinical interventions over 14 domains: 1) Knowledge; 2) Skills; 3) Social/Professional role and identity; 4) Beliefs about capabilities; 5) Optimism; 6) Beliefs about consequences; 7) Reinforcement; 8) Intentions; 9) Goals; 10) Memory, attention and decision-making processes; 11) Environmental context and resources; 12) Social influences; 13) Emotions; and 14) Behavioural regulation (Cane et al., Citation2012). The COM-B model highlights the interaction between a person’s Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation for a Behaviour to be performed (Michie et al., Citation2011). If there is a problem in one of these components, the behaviour will not be performed. The interview questions aimed to explore the local barriers and enablers to the use of sensory approaches and recommendations to improve their use in the local ward. The interview guide contained prompt questions to elicit further information (see Supplementary Table 1 for the Interview Question Guide).

The researcher kept detailed field notes and made detailed reflexive notes on the processes involved throughout all stages of the project.

Data analysis

Data from the interviews were voice recorded, de-identified, and transcribed verbatim for analysis. Framework (Ritchie & Spencer, Citation2002) and thematic analyses (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) were used to analyse the semi-structured interviews, using hybrid methods (both deductive and inductive methods), which is a commonly used approach in implementation research (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, Citation2006) and fitting with the descriptive nature of qualitative description. The data was first analysed using a systematic approach consistent with the framework method (Ritchie & Spencer, Citation2002). One researcher (LW) familiarised herself with two transcripts, and independently coded participants’ responses against the TDF. A second researcher (SB) reviewed the coding. Researchers (LW & SB) then met to discuss any discrepancies in coding. The remaining transcripts were coded by the first researcher (LW) and checked by the second researcher (SB). Data was analysed until no new codes emerged. Thematic analysis was also conducted by researchers to establish any themes that may not fit into the TDF utilising the method described by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006; Braun et al., Citation2019). The data were then charted into the framework matrix including any themes established outside the TDF, with responses categorised as recommendations, barriers, or enablers. The charting of all data was checked by a second researcher (SB) and discrepancies were discussed with the first researcher (LW). The final category structure was checked by two researchers (PM & ED) to enhance rigour and then all authors met to discuss discrepancies and reach consensus. Lastly, the researchers interpreted the data using saliency analysis (Buetow, Citation2010), as described in previous research conducted by Wright et al. (Citation2020). A factor was considered salient if it was determined to be highly important (e.g. “it is essential”) in influencing the use of sensory approaches in the local context or if it was mentioned frequently by participants, or both (Buetow, Citation2010; Shrubsole et al., Citation2019; Wright et al., Citation2020). Researchers decided saliency of the factors influencing sensory approaches in the local ward “if participants emphasised the importance of a factor (e.g. ‘there’s been a lot’) or frequently mentioned in detail a factor” (Wright et al., Citation2020, p. 610). Finally, all researchers decided which factors and TDF domains were salient in influencing the use of sensory approaches in the local context.

Stage two: mapping barriers to behaviour change interventions

The identified TDF domains were mapped to the components of COM-B model to “identify the facet of behaviour requiring intervention (capability, opportunity or motivation)” (Fahim et al., Citation2020, p. 4). The process of linking the TDF with the COM-B model involves firstly identifying the salient TDF domains then mapping these domains to the components of the COM-B model. These are then mapped to the implementation intervention functions of the BCW (see ). The BCW is a robust theoretical approach that describes a systematic theory informed method for linking a model of behaviour to the selection of tailored implementation strategies most likely to address identified barriers (Michie et al., Citation2014; Michie et al., Citation2011). The BCW contains nine intervention functions: “education, persuasion, incentivisation, coercion, training, restriction, environmental restructuring, modelling and enablement” (Michie et al., Citation2014, p. 110). Intervention functions are broad categories of ways an intervention can change behaviour; for example, education can increase knowledge. The final step involves selecting evidence-based behaviour change interventions (implementation strategies) within each intervention function (Michie et al., Citation2014) that will be “most likely to improve” the use of clinical practice in the local context by “addressing, alleviating or reducing the impact of the local barriers” (Straus et al., Citation2013, p. 137).

Figure 2. The behaviour change wheel aligned to the theoretical domain framework. Note: Adapted from: Atkins et al. (Citation2020). Reprinted with permission under Creative Commons licence: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Proposed behaviour change interventions were selected using the Behaviour Change Interventions (BCI) Taxonomy described by Michie et al. (Citation2014). For example, the most frequently used behaviour change interventions for the intervention function of persuasion include credible source, feedback on outcome, and information about social and environmental consequences (Michie et al., Citation2014).

Stage three: co-design of tailored implementation strategy

As the selected behaviour change interventions needed to operate within the local ward, they were evaluated using the APEASE criteria (Michie et al., Citation2014). The APEASE criteria considers whether the behaviour change interventions are affordable, practical, effective and cost-effective, equitable, safe, and free from unintended consequences (Michie et al., Citation2014). These behaviour change interventions were presented to the stakeholder committee to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of the proposed strategies, which were then further refined and a tailored, multifaceted implementation strategy co-designed.

Results

Stage one: interviews

Participant characteristics

Seven semi-structured interviews were conducted in February and March 2020. Additional planned interviews were cancelled due to COVID-19 restrictions so not all disciplines could be included in the interviews. Participants included nursing staff (n = 4, made up of one enrolled nurse, two senior nurses, and one junior nurse), an occupational therapist, and two peer support workers. Six participants were female, and one was male. Their ages ranged from 25 years to 55 years, and their level of experience in mental health care ranged from 5 to 30 years.

Factors influencing the use of sensory approaches in the local context

The most salient data was contained in the TDF domains: Environmental context and resources, Belief about consequences, Knowledge, and Professional role and identity (listed in order of importance). In addition, the domains of Memory, attention and decision-making processes, and Social influences were identified by participants as important in influencing the use of sensory approaches in their work unit. Participants identified barriers, enablers, and provided recommendations to improve the use of sensory approaches in their work unit (See Supplementary Table 2 for further information).

Environmental context and resources

Most barriers were related to this domain of Environmental context and resources. The barriers identified include lack of access and availability of sensory resources and equipment, and workload/time pressures. All participants described the lack, loss, and poor maintenance of sensory equipment and tools. “Sensory items…tend to get lost or misplaced” (Participant 2 - P2).

In addition, all participants identified their high workload and lack of time as a barrier to using sensory approaches with consumers. One participant explained, “It’s [sensory approaches] time consuming” and, similarly, another participant commented “And then unfortunately time constraints—you’d have to just resort to PRN”. When asked about having enough staff, one participant explained, “say if you do it [sensory approaches] with all four or five of your patients… in the afternoon you can have six to seven” (P2). Participants described numerous competing demands, “Pretty much your whole shift is taken up in other tasks. So, time away from your patient is huge” (Participant 3—P3). When another participant was asked how much time they spent with each patient on a shift they explained:

Really depends, … because of the acuity ward is so high, that other things are going to have to slide if your patient really, really needs you. Individually, there’s no way any patient would get an hour of your time. (P3)

Participants’ recommendations focused on providing more sensory equipment (e.g. weighted blankets, furniture, and equipment for the sensory room; smaller consumable sensory items such as fidget items for sensory boxes), and increasing staffing (e.g. introducing minimum patient staff ratios). Participants highlighted the need to improve systems and processes to reduce the loss of, and improve maintenance and restocking of, sensory equipment.

But there’s no record of where things go.…. I think there should be a book that is signed – I know it sounds tedious, but who did that go to and has it been signed back in yet, like any other property…. Especially the blankets… Because they’re so expensive. (Participant 4 - P4)

Recommendations to improve the use of sensory approaches included replacing existing sensory boxes with a sensory trolley in the nurses’ station, clearly labelling and restocking regularly, having logbooks to track who borrowed sensory items, environmental changes to make the ward less clinical and more relaxing, and ongoing funding for sensory tools and equipment. “If it was in a [sensory] trolley or a cupboard in the nurse’s station and it was labelled, we could see everything…”(P2).

Belief about consequences

In this study, participants indicated that their belief that the use of sensory approaches had positive benefits enabled their use. Participants identified numerous benefits for consumers from using sensory approaches on the inpatient unit. These included: reduced use of PRN; improved emotional regulation and promoted a sense of calm; supported a feeling of safety; improved sleep; distracted from mental health symptoms; assisted with withdrawal from cigarettes; and developed self-soothing strategies. One participant commented on the long-term benefits of using sensory approaches:

I think that’s great, because you’re reducing that dependence on solely for their self-soothing to be medication… You’re teaching them other strategies, you know, have a hot drink, try a heat pack, an ice pack, for all those sensations of self-harm, and reducing the stimuli as well for them, in a relaxed environment they feel safe in… (P4)

In this domain, participants thought that if their colleagues didn’t believe sensory approaches were effective, their colleagues may be more likely to use PRN medication. For example, “Some say they don’t believe in it. Some would rather give a PRN because they don’t want trouble on their shift…” (P2). All participants talked about the potential risks of using sensory approaches as being a barrier to their use, including self-harm and harm to the other consumers and staff. “Like, harm, harm to us, harm to themselves. There could be risks of, like, running away with it, losing it, harm to other clients” (P2). In addition, concern was expressed about the risk of weighted blankets for consumers who were medically compromised such as the elderly with co-morbid medical conditions or consumers with eating disorders who were significantly underweight: “…I find particularly around consumers with eating disorders, that they often can be medically compromised quite quickly” (Participant 1-P1).

Participants highlighted the need to improve the use of sensory approaches in their unit, to reduce aggression, self-harm, and PRN use. They suggested personal safety plans could be used with consumers to identify individualised sensory strategies, and that individualised sensory kits could be developed collaboratively with consumers. In addition, participants suggested sensory approaches be used first before PRN medication, “…instead of giving PRN we can just be like, how about you stay in here [sensory room] for a bit. We will come back and check on you” (P2).

Knowledge

Participants identified that having knowledge and an understanding of how to use sensory approaches with consumers enabled their use. “…Good nurses, knowledgeable nurses. There’s a few nurses that know there’s always that other option [sensory approaches]” (2). Conversely, the lack of knowledge and awareness of sensory approaches by staff and consumers was reported as a barrier in their ward. “I’ve had some consumers that have had, I guess, they struggled to understand why we’re developing a sensory plan” (P1). Participants’ recommendations to improve knowledge and awareness of sensory approaches focused on providing more training, education to staff, and orientation to the use of sensory room/tools/equipment for both staff and consumers on the ward. In addition, some participants recommended more promotion of sensory approaches to consumers, so they know what is available to them during their inpatient admission: “…promoting the [sensory room] … because usually it stays locked and it’s quite dark in there, so people don’t really know what it is; it’s just that room next to the laundry…” (Participant 7-P7).

Professional role and identity

Participants generally agreed that providing sensory approaches was part of everyone’s role, including peer support workers: “I think all staff … including doctors” (6). However, some participants felt sensory assessments and plans were the role of the occupational therapist. “I mean, we are not qualified to give, to write the [sensory] plans…” (2). Some participants identified that their colleagues did not believe providing sensory approaches was part of their role; instead, it was the role of the occupational therapist or nurses trained in sensory approaches. The occupational therapist participant commented;

I think it should be a bit more balanced. I’m happy to assist, but I think that particularly …… in PICU [Psychiatric Intensive Care Unit], I feel like it should be the nursing staff. (P2)

Memory, attention, and decision-making processes

In this domain, participants focused on the lack of reminders and prompts to use sensory approaches for staff and consumers on their ward. Participants made recommendations to clearly display prompts and reminders on the ward for the sensory approaches available (i.e. sensory room, weighted modalities, and items available in the sensory boxes), one participant suggested, “I think if we have signs, like, an actual sign that had an arrow that said, if we rename the [sensory] room” (2). Some participants recommended having prompts in the medication room for nurses, for example a sign in the medication room saying, “Before you give medication, have you tried…?”, and they have everything listed for the consumers” (Participant 5—P5). It was also suggested that peer support workers could prompt and promote consumers to use sensory options available on the ward.

Social influences

Participants described how the lack of support from their colleagues could hinder the provision of sensory approaches to consumers. For example, one participant commented how different staff responded to her suggestions to use sensory approaches:

I might say sometimes, “Have you tried sitting with them in the comfort room?” Some are quite open to that, depending on the individual. Others would be like, “Well, piss off, it’s my patient. I’ll do what I want”. (P4)

Belief about capabilities

Most participants discussed how lack of confidence hindered the use of sensory approaches, for example one participant commented “…For me, I think I would promote it but I’m not comfortable enough to promote it enough until I know more about it…” (P5). Increased training and modelling of sensory approaches were recommended by participants to improve clinician’s confidence in using sensory approaches with consumers: “I mean I’d be confident to do the basics …. with more education” (P6).

Stage two: mapping barriers to COM-B model and behaviour change wheel

The results from the COM-B and BCW mapping exercise are presented in . After mapping the TDF to COM-B it could be seen that all six components of behaviour change (psychological and physical capability, physical and social opportunity, reflective and automatic motivation) were identified as influencing the use of sensory approaches in the local context. Six of the intervention functions (Education, Modelling, Enablement, Training, Persuasion and Environmental restructuring) from the BCW were identified as potential intervention categories to improve the use of sensory approaches in the local context. The intervention function of Coercion (e.g. using punishment or cost for not using the approaches) was not acceptable to staff in the ward. In addition, the intervention functions of Restriction (i.e. “using rules to increase the target behaviour”) and Incentivisation (i.e. “creating expectation of reward”) (Michie et al., Citation2014, p. 111) were not practicable in the setting.

Table 1. Theoretical Domain Framework (TDF) domains mapped to COM-B (capability, opportunity, motivation-behaviour) model and behaviour change wheel intervention functions.

Stage three: co-design multifaceted implementation strategy

The proposed strategy, focused on improving the use of weighted modalities, the sensory room, and sensory kits, were assessed using the APEASE criteria and presented to the stakeholder committee. The stakeholder committee requested that a focus on improving the use of the personal safety plans be added to the proposed strategy. The final tailored multifaceted implementation strategy included seven behaviour change interventions: provision and maintenance of sensory equipment/resources; education and training; workplace modelling and demonstration; audit and feedback; prompts and reminders; development of a workplace coalition; and facilitation (see ).

Table 2. Behaviour change interventions mapped to behaviour change wheel (BCW) intervention functions and local barriers.

Discussion

The aim of this research was to assess the local barriers and enablers to use of sensory approaches and co-design a tailored multifaceted implementation strategy to improve their use in one psychiatric ward. This study was guided by the principles of IKT, and drew on the TDF, COM-B model, and the BCW to address the aims.

The use of IKT in this study demonstrates how researchers can partner with clinicians to address implementation problems at the local ward level. While the use of IKT is accepted as a way of improving the implementation of evidence-based practices, however there is need for more research for its use (Graham et al., Citation2018; Nguyen et al., Citation2020). There has been no previous research that has used an IKT approach in acute psychiatric inpatient units, despite calls to address the lack of use of evidence-based psychosocial and psychological interventions in these settings (Evlat et al., Citation2021; Raphael et al., Citation2021). The use of IKT in psychiatric units should be considered to address 1) failure to implement evidence-based interventions such as sensory approaches; 2) the use of harmful interventions such as restrictive practices; 3) the use of ineffective interventions; and 4) the use of interventions with no available evidence such as PRN medication (Wathen & MacMillan, Citation2018). In this study, the use of IKT to engage clinicians had clear advantages to address a problem that related directly to their clinical practice (i.e. the lack of use of sensory approaches); and allowed the researcher to work collaboratively with clinicians to develop tailored strategies to address identified barriers. (Kothari et al., Citation2017).

The use of IKT in mental health settings outside acute settings is also limited to only three previous studies using this approach identified, one focused on community mental health at an organisational level (Bullock et al., Citation2010) and two in child and youth mental health settings (McGrath et al., Citation2009; Preyde et al., Citation2015). For example, Bullock et.al. (2010) focused on using IKT at an organisational level. The principles identified in their research align with this current project, identifying the need to 1) engage with the “right people to do the work”, 2) “formalising, and solidifying relationships, roles and expectations among key stakeholders”; and 3) the need for the “joint identification of issues”. In our study, there was careful consideration of 1) who the right people were to be involved in the stakeholder committee (nurse unit manager, occupational therapists, Safewards nursing champions, carer/consumer consultant, and inpatient psychiatrist consultant); 2) development of formal terms of reference for the stakeholder committee outlining the roles and responsibilities for members; and 3) issues were jointly identified by researcher and local stakeholders. In our study, it was essential to partner with the nursing unit manager from the initial project planning to ensure engagement with nursing staff on the ward and release for nursing staff for sensory training. This aligns with another Australian study that also identified the importance of engaging with the nurse unit manager when implementing sensory approaches (Machingura & Lloyd, Citation2017). In addition, it was considered essential to engage peer and carer support workers in the interviews and the stakeholder committee to ensure people with lived experience were involved in the co-design of implementation strategies.

The importance of engaging people with “lived experience” is well recognised in research in mental health (Byrne & Wykes, Citation2020). Similarly, a study conducted by Dawson et al. (Citation2022) highlighted the importance of hearing the views of people with lived experience to design strategies to improve the use of weighted modalities, however they did not include consumers in the stakeholder committee. The current implementation research which co-designed an implementation strategy to increase the use of sensory approaches involved people with lived experience as members of both the stakeholder committee and ward coalition. While collaborative research in mental health with clinicians and people with “lived experience” is not new, the use of IKT in an Australian psychiatric unit that specifically focuses on implementing recommendations from research provides a unique contribution to research literature.

This study demonstrated the utility of using implementation models, frameworks, and theories to design a targeted implementation strategy. The second stage of this study used the COM-B model and BCW framework to tailor implementation strategies to address identified local barriers (Michie et al., Citation2014). The BCW framework has been previously used in mental health care settings to prioritise the implementation strategies most likely to result in behaviour change (Carney et al., Citation2016; Dawson et al., Citation2022; Faija et al., Citation2021; Mangurian et al., Citation2017; Murphy et al., Citation2014); however, its use in acute psychiatric settings was previously limited to only one study (McAllister et al., Citation2021). Similar to Dawson et al. (Citation2022) the current study used the TDF, COM-B model and BCW to identify barriers and design implementation strategies, however, while Dawson and colleagues targeted only the use of weighted modalities and in a residential rehabilitation psychiatric service, the current study adds to the literature demonstrating the application of a robust, theory-informed approach addressing the use of multiple sensory approaches in an acute psychiatric ward. Importantly, the current study demonstrates the need to understand the specific local contextual factors that hinder or facilitate the use of interventions such as sensory approaches rather than relying on larger-scale surveys of practice, to inform truly tailored implementation strategies. For example, in our research, the lack of sensory kit usage in the acute psychiatric ward was related to their location and lack of maintenance and not primarily related to lack of knowledge as identified by Martin and Suane (Citation2012).

The final stage of this project involved co-designing a multifaceted implementation strategy. A total of seven implementation strategies were selected. Several of the selected strategies have been recommended by previous research when implementing sensory approaches in psychiatric units including:1) provision and maintenance of sensory equipment and resources (Machingura & Lloyd, Citation2017; Sutton & Nicholson, Citation2011); 2) education and training (Azuela & Robertson, Citation2016; Martin & Suane, Citation2012); 3) workplace modelling and demonstration (Blackburn et al., Citation2016); 4) prompts and reminders (Sutton & Nicholson, Citation2011; Wright et al., Citation2020); and 5) audit and feedback (Sutton & Nicholson, Citation2011). The implementation strategies identified in this research that have not previously been described in literature in relation to sensory approaches included the development of a workplace coalition, and facilitation.

The development of a workplace coalition aimed to “recruit and cultivate relationships” with ward staff to improve the use of sensory approaches in the local ward through local collaboration (Powell et al., Citation2012) was well received. Although workplace coalitions have not previously been described to improve the use of sensory approaches, the support of colleagues has been found to influence their use (Blackburn et al., Citation2016; Dawson et al., Citation2022; Machingura & Lloyd, Citation2017; Wright et al., Citation2020; Yakov et al., Citation2018). Previous research has suggested that while the use of sensory champions could provide social support to improve the use of sensory approaches in psychiatric units (Machingura & Lloyd, Citation2017; Yakov et al., Citation2018), the use of champions has been an ineffective implementation strategy in some psychiatric units (Higgins et al., Citation2018).

Facilitation is an implementation strategy that has shown promising results to improve evidence-based practices (Baskerville et al., Citation2012), however, its use to improve the implementation of sensory approaches has not been investigated. An enabler for successful implementation of sensory approaches is having strong leadership to drive change (Azuela, Citation2019; Dorn et al., Citation2020; Sutton & Nicholson, Citation2011; Wright et al., Citation2020) and our study found that the use of facilitation as an implementation strategy provided the support and leadership required to prepare for a change in sensory practice. Further research is required to understand how to best tailor implementation strategies and to evaluate whether they improve the use of sensory approaches in specific mental health settings.

Strengths and limitations

This study had several methodological strengths. Purposive sampling allowed different members of the multidisciplinary team, including peer support workers from different levels of seniority, to express their views about the factors they perceived to influence the implementation of sensory approaches in their ward. The involvement of nursing staff (n = 4) in these interviews allowed the researcher to understand factors that influenced the use of sensory approaches during evening, night, and weekend hours. The use of IKT in this study improved the relevance of this research to the local context. The selection of implementation strategies is strengthened in this study through use of TDF, COM-B model and BCW to systematically select strategies that will most likely achieve behaviour change in the local setting. More research is required to evaluate if the tailored implementation strategy results in improved use of sensory approaches in the local ward.

It is acknowledged that there are several limitations of this research. The participants in this study were from one acute psychiatric unit in a metropolitan mental health service in Queensland, Australia and the factors influencing the use of sensory approaches may not be able to be generalised to other psychiatric units. In fact, the findings of this research, compared to previous research in the broader mental health setting (Wright et al., Citation2020) suggest it is likely that some factors are indeed specific to the local setting. In addition, the implementation strategies selected were tailored to the local context within the service’s budget and resources and transferability to other psychiatric units should be driven by prior, careful consideration of factors and resources within the local ward.

It is acknowledged that there is potential for bias as the researcher had previously worked as an occupational therapist in the psychiatric unit studied. The researcher made detailed reflexive notes in her field notes and used peer debriefing during both data collection and analysis to attempt to remain aware of potential biases. Nevertheless, this potential for bias should be considered.

Conclusion

This study describes the development of a theory-informed, multifaceted, tailored implementation strategy designed to improve implementation of sensory approaches in one acute mental health ward. This is the first study known to authors to use IKT to co-design implementation strategies to improve sensory approaches. It highlights the importance of understanding the demands placed on clinicians and peer workers that compete with providing sensory approaches. It demonstrates the importance of understanding the performance of sensory approaches in a local setting to design implementation strategies that will address local barriers, are relevant, practical, and will facilitate use of sensory approaches. The findings of this study advance the understanding of the barriers and enablers of sensory approaches in acute inpatient psychiatric units and provides mental health services with a theory-informed method to understand and design implementation strategies to address local challenges to implementing sensory approaches. Further research is required to evaluate if the tailored implementation strategies improve the implementation of sensory approaches in the local ward.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (20.8 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (23.4 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and thank staff from The Prince Charles Hospital Mental Health Unit for their participation in the study and The Prince Charles Hospital Foundation “The Common Good” for funding this research.

Disclosure statement

LW, SB and PM participated in the design and planning of this study. LW was responsible for conducting the interviews, meeting with local stakeholders and analysis of the data. PM SB and ED provided guidance on the data analysis. All authors participated in the drafting of the manuscripts and approved the final manuscript. SB, PM and ED declare no competing interests. LW is employed at the Metro North Mental Health and facilitated sensory approaches training across the service.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Atkins, L., Sallis, A., Chadborn, T., Shaw, K., Schneider, A., Hopkins, S., Bunten, A., Michie, S., & Lorencatto, F. (2020). Reducing catheter-associated urinary tract infections: A systematic review of barriers and facilitators and strategic behavioural analysis of interventions. Implementation Science, 15(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-020-01001-2

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2017). National consenus statement: Essential elements for recognising and responding to deterioration in a person’s mental state. Australian Government. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/National-Consensus-Statement-Essential-elements-for-recognising-and-responding-to-deterioration-in-a-person’s-mental-state-July-2017.pdf

- Azuela, G. (2019). The implementation and impact of sensory modulation in Aotearoa New Zealand adult acute mental health service: Two organisational case studies. [Doctoral thesis, Auckland University of Technology] Auckland, New Zealand. https://openrepository.aut.ac.nz/handle/10292/12608

- Azuela, G., & Robertson, L. (2016). The effectiveness of a sensory modulation workshop on health professional learning. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 11(5), 317–331. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMHTEP-08-2015-0037

- Baskerville, N. B., Liddy, C., & Hogg, W. (2012). Systematic review and meta-analysis of practice facilitation within primary care settings. Annals of Family Medicine, 10(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1312

- Bensemann, C. (2018). Zero seclusion: Towards eliminating seclusion by 2020. 12th National Forum: Eliminating Restrictive Practices.

- Blackburn, J., McKenna, B., Jackson, B., Hitch, D., Benitez, J., McLennan, C., & Furness, T. (2016). Educating mental health clinicians about sensory modulation to enhance clinical practice in a youth acute inpatient mental health unit: A feasibility study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 37(7), 517–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2016.1184361

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., & Terry, G. (2019). Thematic analysis. In P. Liamputtong (Ed.), Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences (pp. 843–860). Springer Singapore.

- Brown, C., & Dunn, W. (2002). Adolescent/adult sensory profile. Pearson.

- Brown, C., Tollefson, N., Dunn, W., Cromwell, R., & Filion, D. (2001). The Adult Sensory Profile: Measuring patterns of sensory processing. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy: Official Publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association, 55(1), 75–82. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.55.1.75

- Buetow, S. (2010). Thematic analysis and its reconceptualization as ‘saliency analysis’. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 15(2), 123–125. https://doi.org/10.1258/jhsrp.2009.009081

- Bullock, H., Watson, A., & Goering, P. (2010). Building for success: Mental health research with an integrated knowledge translation approach. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 29(S5), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.7870/cjcmh-2010-0031

- Byrne, L., & Wykes, T. (2020). A role for lived experience mental health leadership in the age of Covid-19. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 29(3), 243–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2020.1766002

- Cane, J., O’Connor, D., & Michie, S. (2012). Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implementation Science: IS, 7(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-37

- Carney, R., Bradshaw, T., & Yung, A. R. (2016). Physical health promotion for young people at ultra‐high risk for psychosis: An application of the COM‐B model and behaviour‐change wheel. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 25(6), 536–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12243

- Chalmers, A., Harrison, S., Mollison, K., Molloy, N., & Gray, K. (2012). Establishing sensory-based approaches in mental health inpatient care: A multidisciplinary approach. Australasian Psychiatry, 20(1), 35–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856211430146

- Champagne, T. (2011). Sensory modulation & environment essential elements of occupation (3rd ed.). Pearson Australia Group.

- Champagne, T. (2018). Sensory modulation in dementia care: Assessment and activities for sensory-enriched care. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Cheng, S. C., Hsu, W. S., Shen, S. H., Hsu, M. C., & Lin, M. F. (2017). Dose-response relationships of multisensory intervention on hospitalized patients with chronic schizophrenia. The Journal of Nursing Research: JNR, 25(1), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/jnr.0000000000000154

- Craswell, G., Dieleman, C., & Ghanouni, P. (2021). An integrative review of sensory approaches in adult inpatient mental health: Implications for occupational therapy in prison-basmental health services. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 37(2), 130–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2020.1853654

- Dawson, S., Oster, C., Scanlan, J., Kernot, J., Ayling, B., Pelichowski, K., & Beamish, A. (2022). A realist evaluation of weighted modalities as an alternative to pro re nata medication for mental health inpatients. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 31(3), 553–566. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12971

- Dorn, E., Hitch, D., & Stevenson, C. (2020). An evaluation of a sensory room within an adult mental health rehabilitation unit. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 36(2), 105–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2019.1666770

- Ekholm, B., Spulber, S., & Adler, M. (2020). A randomized controlled study of weighted chain blankets for insomnia in psychiatric disorders. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine: JCSM: Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 16(9), 1567–1577. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.8636

- Eron, K., Kohnert, L., Watters, A., Logan, C., Weisner-Rose, M., & Mehler, P. S. (2020). Weighted blanket use: A systematic review. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy: Official Publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association, 74(2), 7402205010p1–7402205010p14. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.037358

- Evlat, G., Wood, L., & Glover, N. (2021). A systematic review of the implementation of psychological therapies in acute mental health inpatient settings. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 28(6), 1574–1586. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2600

- Fahim, C., Acai, A., McConnell, M. M., Wright, F. C., Sonnadara, R. R., & Simunovic, M. (2020). Use of the theoretical domains framework and behaviour change wheel to develop a novel intervention to improve the quality of multidisciplinary cancer conference decision-making. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 578. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05255-w

- Faija, C. L., Gellatly, J., Barkham, M., Lovell, K., Rushton, K., Welsh, C., Brooks, H., Ardern, K., Bee, P., & Armitage, C. J. (2021). Enhancing the behaviour change wheel with synthesis, stakeholder involvement and decision-making: A case example using the ‘Enhancing the Quality of Psychological Interventions Delivered by Telephone’ (EQUITy) research programme. Implementation Science, 16(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-021-01122-2

- Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107

- Gagliardi, A. R., Berta, W., Kothari, A., Boyko, J., & Urquhart, R. (2016). Integrated knowledge translation (IKT) in health care: A scoping review. Implementation Science: IS, 11(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0399-1

- Girlanda, F., Fiedler, I., Ay, E., Barbui, C., & Koesters, M. (2013). Guideline implementation strategies for specialist mental healthcare. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 26(4), 369–375. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e328361e7ae

- Graham, I. D., Kothari, A., & McCutcheon, C, Integrated Knowledge Translation Research Network Project Leads. (2018). Moving knowledge into action for more effective practice, programmes and policy: Protocol for a research programme on integrated knowledge translation. Implementation Science: Is, 13(1), 22–22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0700-y

- Graham, I. D., Logan, J., Harrison, M. B., Straus, S. E., Tetroe, J., Caswell, W., & Robinson, N. (2006). Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 26(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.47

- Hamilton, B., Fletcher, J., Sands, N., Roper, C., & Elsom, S. (2016). Safewards Victorian Trial Final Evaluation Report.

- Harvey, G., & Kitson, A. (2015). Implementing evidence-based practice in healthcare. Taylor & Francis.

- Higgins, N., Meehan, T., Dart, N., Kilshaw, M., & Fawcett, L. (2018). Implementation of the Safewards model in public mental health facilities: A qualitative evaluation of staff perceptions. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 88, 114–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.08.008

- Kothari, A., McCutcheon, C., & Graham, I. D. (2017). Defining integrated knowledge translation and moving forward: A response to recent commentaries. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 6(5), 299–300. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2017.15

- Lee, S. J., Cox, A., Whitecross, F., Williams, P., & Hollander, Y. (2010). Sensory assessment and therapy to help reduce seclusion use with service users needing psychiatric intensive care. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 6(02), 83–90. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742646410000014

- Lifvergren, S., Huzzard, T., & Docherty, P. (2008). A development coalition for sustainability in healthcare. In P. Docherty, M. Kira, & A. B. Shani (Eds.), Creating sustainable work systems (pp. 193–211) Routledge.

- Long, J. C., Debono, D., Williams, R., Salisbury, E., O’Neill, S., Eykman, E., Butler, J., Rawson, R., Phan-Thien, K.-C., Thompson, S. R., Braithwaite, J., Chin, M., & Taylor, N. (2018). Using behaviour change and implementation science to address low referral rates in oncology. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 904. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3653-1

- Machingura, T., & Lloyd, C. (2017). A reflection on success factors in implementing sensory modulation in an acute mental health setting. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 24(1), 35–39. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijtr.2017.24.1.35

- Machingura, T., Lloyd, C., Murphy, K., Goulder, S., Shum, D., & Green, A. (2021). Views about sensory modulation from people with schizophrenia and treating staff: A multisite qualitative study. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 84(9), 550–560. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022620988470

- Mangurian, C., Niu, G. C., Schillinger, D., Newcomer, J. W., Dilley, J., & Handley, M. A. (2017). Utilization of the Behavior Change Wheel framework to develop a model to improve cardiometabolic screening for people with severe mental illness. Implementation Science: IS, 12(1), 134. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0663-z

- Martin, B. A., & Suane, S. N. (2012). Effect of training on sensory room and cart usage. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 28(2), 118–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2012.679526

- McAllister, S., Simpson, A., Tsianakas, V., Canham, N., De Meo, V., Stone, C., & Robert, G. (2021). Developing a theory-informed complex intervention to improve nurse–patient therapeutic engagement employing experience-based co-design and the behaviour change wheel: An acute mental health ward case study. BMJ Open, 11(5), e047114. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047114

- McGrath, P. J., Lingley-Pottie, P., Emberly, D. J., Thurston, C., & McLean, C. (2009). Integrated knowledge translation in mental health: Family help as an example. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 18(1), 30–37.

- Michie, S., Atkins, L., & West, R. (2014). The behaviour change wheel. Silverback Publishing.

- Michie, S., van Stralen, M., & West, R. (2011). The Behaviour Change Wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

- Murphy, A. L., Gardner, D. M., Kutcher, S. P., & Martin-Misener, R. (2014). A theory-informed approach to mental health care capacity building for pharmacists. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 8(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-4458-8-46

- Nguyen, T., Graham, I. D., Mrklas, K. J., Bowen, S., Cargo, M., Estabrooks, C. A., Kothari, A., Lavis, J., Macaulay, A. C., MacLeod, M., Phipps, D., Ramsden, V. R., Renfrew, M. J., Salsberg, J., & Wallerstein, N. (2020). How does integrated knowledge translation (IKT) compare to other collaborative research approaches to generating and translating knowledge? Learning from experts in the field. Health Research Policy and Systems, 18(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-0539-6

- Nilsen, P., & Birken, S. A. (2020). Handbook on Implementation Science. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Novak, T., Scanlan, J., McCaul, D., MacDonald, N., & Clarke, T. (2012). Pilot study of a sensory room in an acute inpatient psychiatric unit. Australasian Psychiatry: Bulletin of Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, 20(5), 401–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856212459585

- O’Sullivan, J., & Fitzgibbon, C. (2018). Sensory modulation: Changing how you feel through using your senses. Resource Manual. Sensory Modulation Brisbane.

- Porcheret, M., Main, C., Croft, P., McKinley, R., Hassell, A., & Dziedzic, K. (2014). Development of a behaviour change intervention: A case study on the practical application of theory. Implementation Science, 9(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-9-42

- Powell, B. J., McMillen, J. C., Proctor, E. K., Carpenter, C. R., Griffey, R. T., Bunger, A. C., Glass, J. E., & York, J. L. (2012). A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Medical Care Research and Review: MCRR, 69(2), 123–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558711430690

- Powell, B. J., Waltz, T. J., Chinman, M. J., Damschroder, L. J., Smith, J. L., Matthieu, M. M., Proctor, E. K., & Kirchner, J. E. (2015). A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implementation Science: IS, 10(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1

- Preyde, M., Carter, J., Penney, R., Lazure, K., Vanderkooy, J., & Chevalier, P. (2015). Integrated knowledge translation: Illustrated with outcome research in mental health. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 12(2), 175–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/15433714.2013.794117

- Raphael, J., Price, O., Hartley, S., Haddock, G., Bucci, S., & Berry, K. (2021). Overcoming barriers to implementing ward-based psychosocial interventions in acute inpatient mental health settings: A meta-synthesis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 115, 103870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103870

- Ritchie, J., & Spencer, L. (2002). Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In The Qualitative Researcher’s Companion (pp. 305–329). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Sandelowski, M. (2000). Focus on research methods—Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health, 23(4), 334–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<334::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G

- Scanlan, J. N., & Novak, T. (2015). Sensory approaches in mental health: A scoping review. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 62(5), 277–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12224

- Shrubsole, K., Worrall, L., Power, E., & O’Connor, D. A. (2019). Barriers and facilitators to meeting aphasia guideline recommendations: What factors influence speech pathologists’ practice? Disability and Rehabilitation, 41(13), 1596–1607. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1432706

- Straus, S., Tetroe, J., & Graham, I. D. (2013). Knowledge translation in health care: Moving from evidence to practice. John Wiley & Sons.

- Sutton, D., Nicholson, E. (2011). Sensory modulation in acute mental health wards: A qualitative study of staff and service user perspectives. Te Pou o Te Whakaaro Nui. https://www.tepou.co.nz/resources/sensory-modulation-in-acute-mental-health-wards-a-qualitative-study-of-staff-and-service-user-perspectives

- Wathen, C. N., & MacMillan, H. L. (2018). The role of integrated knowledge translation in intervention research. Prevention Science: The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research, 19(3), 319–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-015-0564-9

- Wright, D. M. (2017). Review of seclusion, restraint and observation on consumers with a mental health illness in NSW health facilities. N. S. W. Government. https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/mentalhealth/reviews/seclusionprevention/Documents/report-seclusion-restraint-observation.pdf

- Wright, L., Bennett, S., & Meredith, P. (2020). ‘Why didn’t you just give them PRN?’: A qualitative study investigating the factors influencing implementation of sensory modulation approaches in inpatient mental health units. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29(4), 608–621. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12693

- Wright, L., Meredith, P., & Bennett, S. (2021). Use of the Theoretical Domain Framework to understand what influences the use of sensory approaches in mental health inpatient units: A survey of mental health clinicians. [Unpublished manuscript] School of Health and Rehabilitation Science, The University of Queensland.

- Wright, L., Meredith, P., & Bennett, S. (2022). Sensory approaches in psychiatric units: Patterns and influences of use in one Australian health region. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 69(5), 559–573. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12813

- Wright, M., Crowe, J., Huckshorn, K. A., Lenihan, K., Mooney, J., Shields, R. (2017). Review of seclusion, restraint and observation of consumers with mental illness in NSW health facilities. http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/patients/mentalhealth/Documents/report-seclusion-restraint-observation.pdf

- Yakov, S., Birur, B., Bearden, M. F., Aguilar, B., Ghelani, K. J., & Fargason, R. E. (2018). Sensory reduction on the general milieu of a high-acuity inpatient psychiatric unit to prevent use of physical restraints: A successful open quality improvement trial. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 24(2), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078390317736136