Abstract

Psychiatric intensive care units (PICUs) provide care and treatment when psychiatric symptoms and behaviors exceed general inpatient resources. This integrative review aimed to synthesize PICU research published over the past 5 years. A comprehensive search in MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed and Scopus identified 47 recent articles on PICU care delivery, populations, environments, and models. Research continues describing patient demographics, and high rates of challenging behaviors, self-harm, and aggression continue being reported. Research on relatives was minimal. Patients describe restrictive practices incongruent with recovery philosophies, including controlling approaches and sensory deprivation. Some initiatives promote greater patient autonomy and responsibility in shaping recovery, yet full emancipatory integration remains limited within PICU environments. Multidisciplinary collaboration is needed to holistically advance patient-centered, equitable, and integrative PICU care. This review reveals the complex tensions between clinical risk management and emancipatory values in contemporary PICU settings. Ongoing reporting of controlling practices counters the recovery movement progressing in wider mental healthcare contexts. However, care innovations centered on patient empowerment and humane environments provide hope for continued evolution toward more liberation-focused PICU approaches that uphold both patient and provider perspectives.

Introduction

Earlier research has shown that psychiatric intensive care units (PICUs) are considered when the nursing resources and treatment capacity of general psychiatric and acute care wards cannot meet the needs of patients experiencing severe psychiatric symptoms and engaging in challenging behaviors (Bowers, Citation2012). The complex care required for this patient population exceeds what can be provided on regular inpatient units (Bowers, Citation2012; Bowers et al., Citation2014; Kasmi, Citation2010; Onyon et al., Citation2006). Some key features of PICUs are their small-scale design, lower bed capacity, and higher staff-to-patient ratio as compared to acute wards (Scanlan, Citation2010). PICUs aim to provide a safe environment for both patients and staff in ways that are not possible in acute and general psychiatric wards. Consequently, PICU care requires extensive resources and are 55% more expensive to run than acute care (Bowers et al., Citation2008). Although, few studies have accounted for resources needed in PICU care. A recent study by Wolff et al. (Citation2015) used work sampling to analyze staff time allocation across various inpatient units at a psychiatric hospital in Germany. They found that nursing time represented the largest share of resource use. A considerable portion of staff time was also dedicated to indirect patient care activities like documentation. In a Norwegian population-based study, Evensen et al. (Citation2016) analyzed the societal costs of schizophrenia using national registers. The estimated average yearly cost per patient was 106,000€. Inpatient care was the largest cost contributor at 33% of total costs.

PICUs serve as an important component of psychiatric clinics and hospitals and have gained international acknowledgement during the nearly 50 years of their existence (Björkdahl et al., Citation2006; Citrome et al., Citation1994; Hafner et al., Citation1989; Jones, Citation1985; Pereira et al., Citation1999; Rachlin, Citation1973; Rosen, Citation1975; Sugiyama, Citation2005; Warneke, Citation1986; Wynaden et al., Citation2001). In the first study on psychiatric intensive care, Rachlin (Citation1973) reported that patients were significantly younger compared to patients on other wards at the psychiatric hospital, and that there was an overrepresentation of male patients as well as patients with a history of previous admissions. Treatment was described as liberal regarding the use of pharmaceuticals and as having a high staff presence. It seems that Raclin’s description more or less set a standard for PICUs that persisted for several decades. A plethora of studies have found some agreement on what characterizes the targeted patient group: overrepresentation of men (Dolan & Lawson, Citation2001; O'Brien & Cole, Citation2004; Pereira et al., Citation2005; Wynaden et al., Citation2001), about 30 years old (Cohen & Khan, Citation1990; Cullen et al., Citation2018; Eaton et al., Citation2000; Mitchell, Citation1992), diagnosis group of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder (Brown & Bass, Citation2004; Pereira et al., Citation2005; Wynaden et al., Citation2001) and prevalence of aggression and violence prior to and during admission (Brown & Bass, Citation2004; Ryan & Bowers, Citation2005) as well as challenging behavior without aggression (Onyon et al., Citation2006). Studies have stated that PICU patients are for the most part involuntary admissions (Georgieva et al., Citation2010; Koppelmans et al., Citation2009; Shahpesandy et al., Citation2015). The ongoing debate on length of stay, as a vital parameter for PICUs, indicates that short stays at PICUs are preferrable (AusHFG, Citation2016; NAPICU, Citation2014). However, the data reported in studies display heterogeneity. For example, Brown et al. (Citation2010) reported a mean length of stay of 35 days, with a range of 1–315 days based on 332 patients admitted at seven PICUs in the UK. Two other studies, both from Norway, reported a mean length of stay of 13.5 days for patients who demonstrated violent behavior and 5.3 days for those who did not (Iversen et al., Citation2016). Another study from England showed that the mean length of stay was 21 days 1 year and 16 days the following year (Mustafa, Citation2017). To put these figures in perspective, the national guidelines for PICUs in UK (NAPICU Citation2014) state that length of stay should be determined by patients’ needs and risk assessments, although it is recommended that stays not exceed 8 weeks. Similar national guidelines in Australia recommend even shorter admission durations: 2 to 21 days (AusHFG, Citation2016).

Because this review will synthesize literature on both general and specialty PICUs, including child and adolescent psychiatric intensive care units, this subspeciality is also importance to acknowledge in this background. Child and adolescent psychiatric intensive care units provide specialized inpatient treatment for youth experiencing acute psychiatric crises. Compared to adult PICUs, child and adolescent PICUs serve a more complex patient population, including youth with neurodevelopmental disorders, trauma histories, and failed prior treatment attempts. Lengths of stay tend to be longer, and discharge can be delayed by limited community placement options. The nursing care required spans developmental stages and requires attending to attachment and dependency needs. Evidence on effective treatment approaches in child and adolescent PICUs remains limited (Foster & Smedley, Citation2016).

The concept of recovery-focused care has been touched upon in PICU research, emphasizing a move away from merely ‘fixing patients’ symptoms’ to guiding individuals in their own journey toward finding hope and meaning in life through supportive relationships (Barker, Citation2003; Barker & Buchanan-Barker, Citation2010; Hawsawi et al., Citation2021; Ibrahim et al., Citation2022). Elements of a recovery-oriented approach—such as changing staff attitudes, treatment policies, and the physical environment—have been explored in PICU research (Ash et al., Citation2015; Georgieva et al., Citation2010). A study from Sweden evaluated the implementation of sensory rooms on inpatient wards (also PICUs, but not exclusively) and reported that patients felt the rooms reduced their anxiety (Hedlund Lindberg et al., Citation2019). Moreover, staff appreciated the sensory rooms because they observed relaxation in patients, but they also expressed concerns about the effectiveness of using such rooms for acutely ill patients (Björkdahl et al., Citation2016). Despite these promising attempts, Waldemar (Citation2016) stated that the recovery approach on acute wards tends to be vague and is sometimes simplistically interpreted by practitioners. Nonetheless, a scoping review of humanization on acute psychiatric wards emphasized that, to achieve humanistic practice and ensure that all patients are met with dignity and respect, multifactorial aspects need to be acknowledged: culture, attitudes, staffing levels, etc. (Sanz-Osorio et al., Citation2023). According to earlier research, attempts to develop a person-centered and recovery-oriented care approach are highly palpable. Still, some findings need to be considered, as was reported by McAllister and McCrae (Citation2017) in their mixed-methods study on the therapeutic role of nurses at a PICU. They found that patients did not want longer interactions with nurses, while nurses reported believing they would have more face-to-face interactions if they were not occupied with administrative tasks. The matter of “being present” was also problematized in an ethnographic study conducted at a PICU. It was held that being present did not entail interacting with patients, but rather with being available so that patients could speak to staff if needed. Hence, the staff placed themselves strategically in the environment, for example watching TV, reading a newspaper or laying a dining table (Salzmann-Erikson et al., Citation2011).

The review of existing research indicates that PICU research is divergent, focusing on various aspects and variables and involving multiple professions. Therefore, there is a need for an integrated approach to review recent studies. Although psychiatry intensive care is the level of care in the psychiatric sector that requires ‘top-notch care,’ relatively few studies focus specifically on psychiatric intensive care or PICUs compared to the wider scope of publications in psychiatric care. However, PICU research remains fragmented across disciplines. There is a lack of integration in knowledge regarding contemporary treatment strategies, patient needs, and the care environment. Therefore, the aims of this review are to consolidate evidence on 1) patient characteristics and behaviors, 2), treatments approaches, and 3) the care context in current PICU literature.

Research questions:

What recent evidence exists detailing PICU patient characteristics and behaviors?

What treatment strategies are currently being investigated in PICU research?

How does contemporary literature portray PICU nursing practice and the care environment?

Methods

To consolidate perspectives from multiple disciplines and professions to develop a comprehensive understanding of the PICU evidence base. An integrative review (Whittemore & Knafl, Citation2005) was chosen as it facilitates the incorporation of diverse forms of evidence spanning theoretical and empirical literature. The review questions required analysis at multiple levels, including treatment strategies, care processes, and organizational factors. The flexibility of an integrative review allows for simultaneous analysis of different variables within a complex phenomenon (Torraco, Citation2005). Moreover, the integrative review methodology permits critical analysis of patterns and relationships within the literature, rather than solely aggregating empirical data. The five methodological steps as described by Wittenmore and Knafl were followed: problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis and presenting.

Literature search

The inclusion criteria, based on the Population-Concept-Context (PCC) (Joanna Briggs Institute, Citation2014), are presented in and were formulated from the purpose and the guiding questions. The criteria for selecting the articles were as follows: (a) original research, including brief reports if structured in IMRaD-format, (b) written in English, (c) specific focus on psychiatric intensive care (intensive should be found in title and/or abstract, or journal title). If an article was found in the search that did not have “intensive” in the abstract/journal title or keywords, it was read in full text to further examine why it was found in the search. Exclusion criteria were the following: (a) publication types: review articles, opinions, letters, audits, theses, and editorials, (b) publication prior to 2018. One broad but specific search term was used in all databases: “psychiatric intensive care.” The search was tested by extending it to also include “PICU” as a search term, using the Boolean term OR. The search resulted in thousands of results, as the same acronym is used for “Pediatric Intensive Care Unit” and therefore could not be used. The following four databases were used: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed and Scopus. These were chosen because they cover a broad range of journals with various indexations. The search was executed between 12 September 2022, 2:45pm UTC + +2:45pm UTC + 2 er 2022, 3:20pm UTC + 2. An updated search was conducted in March 2023, but no new articles were found.

Table 1. Inclusion based on Population, Concept and Context (PCC).

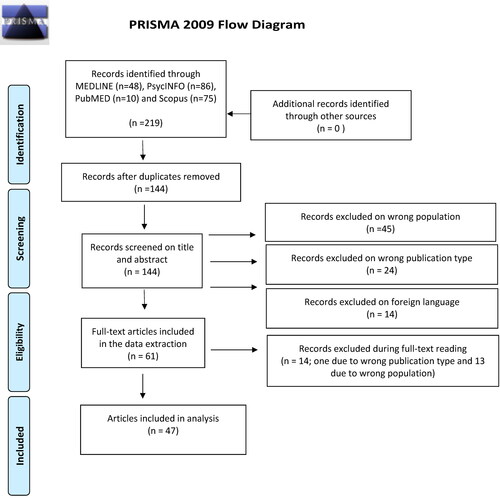

Selection of sources

Two hundred and nineteen articles were found. After removal of duplicates (n = 75), the remaining 144 articles were screened for their title and abstract to ensure that they met the inclusion criteria. Three predetermined reasons for exclusion, per Rayyan, were chosen: (a) wrong population (n = 45); (b) wrong publication type (n = 24); (c) foreign language (n = 14). After the first screening, 61 articles remained. Because a double-blind screening was not possible, as this is a single-author review, all articles were screened once more 3 days after the initial screening to ensure the author’s consistency. Quality assessment was not conducted. Even though critical appraisals are of utmost importance in meta-analysis, it is more complex and difficult to complete this in integrative reviews and mapping reviews (Grant & Booth, Citation2009; Whittemore & Knafl, Citation2005). From the full-text reading, six articles were excluded due to wrong publication type and eight articles were not about PICU; the final number of included articles in the sample was 47 ().

Data extraction

Data were extracted on: authors, year, country, aim/purpose, study population and/or sample size, methodology/methods, and key findings. To add to the map, extra data were extracted on: indexation in databases, availability—due to Open Access publishing—and academic subject area of research.

Data analysis

In addition to present the data extraction in tabular form, the articles were mapped and synthesized. To map the current available research, the integrative review method provides the researcher to make a categorization of available data (Hetrick et al., Citation2010; Khangura et al., Citation2012; Parkhill et al., Citation2011; Whittemore & Knafl, Citation2005). After reviewing the articles, an initial section on the characteristics of the articles was developed. Subsequently, four key themes were identified to structure the rest of the Results.

Each article was assigned to a main theme. Within these main themes, sub-themes were identified to capture the internal heterogeneity. For instance, under the main theme of ‘Improvements,’ sub-themes such as ‘improving the organization’ and ‘improving screening of patients’ were distinguished. visualizes how the articles were distributed across the main themes and their corresponding sub-themes. Since this is a single-author study, the analysis and results were scrutinized in a collegial research seminar. The author of this review is also the author of two articles included in the analysis. The risk of bias was discussed in the research seminar but the reviewers found no conflicting interests.

Table 2. Visualization of how the articles were distributed across the themes and sub-themes.

Results

The Results section begins with an overview of the ‘Characteristics of the Articles,’ detailing aspects such as availability of research, professions and academic subject areas involved, methods used, and settings. Following this, the findings are organized according to the four key themes identified in the data analysis: 1) Treatment Strategies, 2) Everyday Nursing and the Environment, 3) Patients’ Characteristics, and 4) Work Models and Developments. Each of these themes serves as a main heading in the Results section. Within these main headings, more specific aspects are explored as subheadings. In cases where further granularity is necessary, additional levels of headings are introduced. This structure aims to present the findings in a coherent and easily navigable format.

Characteristics of the articles

About half of the articles reported on research from the UK. Norway and the US each had four articles represented in the sample, followed by Italy (n = 3), Sweden (n = 2). The remaining 10 articles were single-country publications from: Austria, Canada, China, Egypt, Indonesia, Ireland, the Netherlands, Spain, Switzerland, and Thailand. The most frequent year of publication was 2021, in which 15 of 47 of the articles were published; 11 were published in 2020, seven in 2019 and 10 publications in 2018. Only four articles were published in 2022, but note that the search was completed in September 2022. Four articles focused on a sample from a female-only PICU, and six articles addressed child- and adolescent-specific PICUs.

Availability of research

Thirteen of the articles were published as Open Access. Only five publications were published in a journal that was indexed in PsychINFO, PubMed and Scopus. About a third of the articles were published in journals that were indexed in only one of the three databases.

Professions and academic subject areas

The articles were sorted into various groups depending on the profession of the authors and/or academic subject areas and implicit/explicit epistemology of the research. From the grouping, the articles were categorized into five groups: psychiatry (n = 23), nursing (n = 11), psychology (n = 3), occupational health (n = 3), and health economy (n = 2).

Methods and methodological concerns

The articles were also grouped into three categories regarding methods used in the research. Qualitative methods were used in 11 articles, but qualitative data were also used in an additional four articles that employed both qualitative and quantitative data (but that necessarily/explicitly categorized the methodology as “mixed-methods”). Most articles (n = 35) used solely quantitative methods. Because experimental study designs are not applicable in qualitative research, only those with quantitative methods were counted as being experimental (n = 15) versus observational (n = 20).

Setting

Participants in the studies reported on in the articles varied owing to the broad research question. Twenty-four of 47 articles had a clear focus on patients in relation to patients’ characteristics and demography, presence of challenging behavior and amount of medication given during admissions. Six articles included both patients and staff as participants, looking at an improvement strategy that was evaluated from ‘both sides.’ Thirteen articles focused solely on staff as study subjects. Those studies were predominantly grouped in the category ‘Nursing.’ Three articles targeted the organization exclusively. Only one article included family members as participants. Most articles (n = 37) used data from a single PICU. In six articles, the included numbers of PICUs were two, three, five, 15, and 21. One outlier included 78 PICUs. Four articles did not explicitly present the number of units. Some examples illustrate the heterogeny in sample size and type of data: qualitative interviews with seven patients; 20 sessions observing staff; questionnaires received from 15 members of the Royal Colleague of Psychiatrists’ PICU quality network; reviewing 300 PICU patients’ charts; and finally, 15 family members who answered a questionnaire and participated in interviews.

Treatment option

Of the articles, five were categorized as dealing with treatment methods and options, which were fairly equally distributed between pharmacological treatment and non-pharmacological treatment.

Winkler and colleagues (Winkler et al., Citation2011) reported that prescribing antidepressants to PICU patients had increased from 29% to 51% over the past 30 years. PICU patients, compared to patients on general acute wards, were more likely to require medical advice from a senior physician (28% vs. 7.5%) (Ward & Prasad, Citation2021). Results from articles in this category show that 59% of the patients were given intramuscular injections of some sort (Gintalaite-Bieliauskiene et al., Citation2020). This is a much higher proportion than reported in Casol et al. (Citation2023) where only 9% were given intramuscular injections, 91% received oral medications, and 25% were given doses that exceeded the daily maximum dosage. Gintalaite-Bieliauskiene (2020) further reported that 100% of patients received antipsychotic medication, and of these 65% were treated with polypharmacy. Forty-four percent were given mood stabilizers and 70% benzodiazepines (Raaj et al., Citation2023).

Regarding non-pharmacological treatment, Gaudiano et al. (Citation2020) found that patients were satisfied with acceptance-commitment therapy (ACT) and that the therapy reduced symptoms significantly. Behavior activation treatment for depression was tested for its feasibility and showed promising outcomes (Myhre et al., Citation2018). Another feasibility study (Mark et al., Citation2021) tested virtual reality on patients. They reported that 94% of patients wanted to try it again and found virtual reality helpful and enjoyable.

Patients’ characteristics

One research focus that remains relevant in PICU research is monitoring and reporting patients’ sociodemographic characteristics, admission patterns, as well as symptoms and behaviors.

Sociodemographic data

The results of most studies show that men are overrepresented as a group, when considering non-single sex units: 71% (Mele et al., Citation2022), 70% (Cooper et al., Citation2018). Three studies reported that men accounted for 48–58% of patients (Okasha et al., Citation2021; Pujol et al., Citation2020; Raaj et al., Citation2023). Mean age was another variable reported in several articles: 37.1 years, with a range of 18–63 (Raaj et al., Citation2023), 29 years (Mele et al., Citation2022), and 44.4 years with a range of 16–92 (Pujol et al., Citation2020). Ward and Prasad (Citation2021) compared PICU patients with patients in a general acute ward and found that the PICU population was younger, 39.7 years with a range of 21–71 compared to 43.7 years with a range of 19-74 (Ward & Prasad, Citation2021). All patients had been admitted involuntarily (Raaj et al., Citation2023), compared to 83% in another study (Ward & Prasad, Citation2021). Thirty-one percent had a forensic history (Raaj et al., Citation2023), and Ward and Prasard (Citation2021) reported that PICU patients had a significantly greater forensic history than did non-PICU patients. Regarding diagnosis in the PICU population: 43% of patients had a schizophrenia diagnosis (Moyes et al., Citation2021), and slightly higher proportions had been reported in other studies: 55% (Howe et al., Citation2018) and 59.7% (Covshoff et al., Citation2023). Howe et al. (Citation2018) reported a prevalence of 41% diagnosed with F30.0-F39.9, and Raaj et al. (Citation2023) reported that 21% had been diagnosed with bipolar affective disorder, 18% with schizoaffective disorder and 9% with acute psychotic disorder (Raaj et al., Citation2023). Covshoff et al. (Citation2023) reported a 32% prevalence for psychotic states. One study (Ward & Prasad, Citation2021) showed that PICU patients scored higher on comorbidity than did non-PICU patients. Substance use was targeted specifically in one article, (Moyes et al., Citation2021) which found that 67% of staff reported that patients had used substances during the past year, most likely cannabis (62%). Due to the heterogeneity of the ways in which diagnoses were reported, it was not possible to pool the data.

Admission patterns

Reasons for admission

The reasons for admission were multifactorial. Assault as the primary risk factor for pre-admission was present in 62% of the cases (Raaj et al., Citation2023). Of the PICU patients, 27.8% had a history of police incidents compared to 19.4% for non-PICU patients (Ward & Prasad, Citation2021). In Gintalaite-Bieliauskiene et al. (Citation2020) study of patients with borderline personality disorder, the authors reported that risk of self-harm was present in 74% of admissions, and threatening aggression and violence in 50%. An Italian study (Tarsitani et al., Citation2022) reported that involuntary admissions were higher among immigrants than among natives (32% vs. 24%). Within the immigrant group, asylum seekers and refugees were more likely to be admitted involuntarily (50%) compared to non-forced migrants (27%). A report from Spain showed that 61.2% of patients had not previously been admitted to the PICU (Pujol et al., Citation2020).

Length of stay

The mean duration of admissions varied: 5 days (Okasha et al., Citation2021), 24 days (Howe et al., Citation2018), 36 days (Pereira et al. (Citation2021)) and 59.3 days (Raaj et al., Citation2023). Chompoosri & Kunchanaphongphan (Citation2020) reported that 44.6% of 112 admissions had stays longer than 5 days as well as that treatment with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), compulsory admission and history of previous admission during the past 12 months were factors that were positively associated with prolonged admission periods. Discharge was reported in some studies. Compared to non-PICU patients, PICU patients were to less likely to be discharged to home, 60% vs. 72.2% (Ward & Prasad, Citation2021). Challinor (2021) implemented a tool to be used by clinicians to reduce delayed transfers of patients when they were no longer in need of PICU care. Implementation resulted in discharges being reduced from 8.3 to 3.5 days.

Readmissions

One article reported that the group of patients with borderline personality disorder was the patient group most likely to return after discharge (Gintalaite-Bieliauskiene et al., Citation2020). Measures of readmission rates were reported at four different time points from discharge: 1 week, 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months. It was found that, at the latter two time points, PICU patients, compared to patients on general wards, were significantly more likely to be readmitted: 33.3% vs. 16.4% (Ward & Prasad, Citation2021).

Symptoms and behavior: Presence of harm and violence

Mele et al. (Citation2022) reported that 65% of all incidents occurred during the first 5 days of admission. Another study reported that 57% of patients self-harmed during the admission period (Gintalaite-Bieliauskiene et al., Citation2020). Accinni et al. (Citation2022) showed that 19.5% attempted suicide at the PICU during their admission, but no correlation was found between such attempts and sex and age. However, they noticed a significant difference in employed patients, who were more likely to attempt suicide than were unemployed patients. Thirty percent expressed aggression and violence toward staff, 30% toward property and 20% toward other patients. One article (Langsrud et al., Citation2018) looked at the association between sleep patterns among PICU patients and risk of violence. They reported that only sleeping a few hours the first night was positively correlated with higher risk of scoring high on the Brøset Violence Checklist (BVC); a six-item observer rating scale used by nurses and staff to assess psychiatric inpatients’ risk of imminent violent behavior over the next 24 h (it is typically completed during each nursing shift). Information on sleep patterns could improve the existing BVC scale (Langsrud et al., Citation2019). A UK study analyzed incidents with a high BVC score (three or more) and found that physical assault on staff and verbal aggression were the most frequent items (Theruvath-Chalil et al., Citation2020). Similarly, Mele et al. (Citation2022) found that staff were most likely to be exposed to violence (65%), that acts of aggression occurred most frequently on Fridays, 18% of the incidents, and that 35% of incidents took place during the period 4 pm to 8 pm.

Use of seclusion and restraints

Six articles indicated that seclusion is practiced at PICUs (Allikmets et al., Citation2020; Cullen et al., Citation2018; Hochstrasser et al., Citation2018; Hughes & Davies, Citation2018; Raaj et al., Citation2023; Salzmann-Erikson, Citation2018a). A few articles reported on the frequency of seclusion and restraint. One study reported that 13% of admitted patients were secluded during the stay and 6% mechanically restrained (Raaj et al., Citation2023). Hochstrasser and colleagues (Hochstrasser et al., Citation2018) used seclusion as an outcome measure in an open-door policy intervention, which resulted in a decrease in use of seclusion.

Everyday nursing care and the environment

Sixteen articles (34.0%) were categorized into the theme addressing everyday care, that is, interactions and interpersonal relations, encounters, nursing practice and ward environment. Characteristic of the articles in this category is having a high proportion of qualitative research methods (11 of 16) and of ‘staff perspectives’ (9 of 16). Only one article reported on relatives’ experiences (Sedgwick et al., Citation2019).

Patients’ view of PICU environment and care

A key message in Allikmets et al. (Citation2020) study on seclusion was that patients experienced lacking communication in the relationship with staff; they felt alone and scrutinized by staff observations. Hughes and Davies (Citation2018) developed a framework that aimed to increase consensus among staff members’ and patients’ view of potential triggers. Patients proclaimed that inconsistency in rules, interventions and policies were sources of frustration. Moreover, patients thought that staff did not reflect on how their way of talking impacted patients; for example, patients could overhear staff talking to each other. In line with this, lack of supporting communication was also found by Allikmets et al. (Citation2020). As regards the ward environment, patients expressed that seclusion rooms could have better decorations and music (Allikmets et al., Citation2020). Similarly, respondents in Hughes and Davies (Citation2018) voiced patients’ perspective that the environment itself is uncomfortable and unhelpful. Even though seclusion rooms are closed areas on a locked ward, Hochstrasser et al. (Citation2018) found that changing the locked-door policy to an “open-door policy” decreased safety measures, seclusion, and forced medication. Walsh-Harrington et al. (Citation2020) introduced 30-minute dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) sessions—called recovery skills group—at a PICU for women. The women found the sessions to be worthwhile and felt they would be helpful to them in the future. Another ward environment modification initiative involved implementing a recovery room at a PICU in the UK. Davies et al. (Citation2020) reported from a project to implement a recovery room equipped with visual, auditory, olfactory and tactile features. Patient feedback was positive, as the rooms facilitated relaxation and the positive experience made the patients want to return. Patients reported frustrations with the restrictions in the PICU environment, which was described as not benefiting the patient and as being uncomfortable (Hughes & Davies, Citation2018). The restrictions were even more palpable during the COVID-19 pandemic when patients had to self-isolate (Harries et al., Citation2021). Pre-pandemic, Butler and colleagues (Butler et al., Citation2020) transformed the interior design at a PICU in collaboration with patients, staff and community artists. Not only did the patients appreciate the artwork, but the collaboration itself also broke down relational barriers and patients reported being proud and finding it meaningful to be involved in the process.

Nurses’ practice

Price et al. (Citation2018) developed a support-control continuum framework in which factors are described that will lead to successful vs. failed de-escalation. Here, the supporting de-escalating techniques are passive interventions. Staff take a step back instead of confronting patients; staff offer reassurance by using phrases that support feelings of safety; staff provide distraction, where the patients’ attention to staff shifts the focus from problems to a conversation about more positive emotions (Foster & Smedley, Citation2019a; Price et al., Citation2018). A nurse-patient relation involves balancing between ward rules and not provoking patients, which is complex. Ward rules were described as being inconsistent, resulting in confusion and complaints (Yusuf et al., Citation2020). In contrast, Foster and Smedley (Citation2019a) reported that rules and expectations helped adolescents at a PICU to navigate the ward’s boundaries, but in a proactive, not reactive way. As nurses are exposed to stress (Yang et al., Citation2018) and patient violence, Foster (Citation2019) investigated the quality of life, while Yang et al. (Citation2018) assessed the effectiveness of mindfulness therapy in reducing stress. Those were the only studies that looked at nurses work-related health.

Intra-professional communication behind the scenes

A continuous dialogue within the nursing teams seems vital to verbalizing what nursing means (Foster & Smedley, Citation2019b). The importance of building a quality and trustful relationship was reported by several studies (Foster & Smedley, Citation2019b; Hughes & Davies, Citation2018; Price et al., Citation2018). Development of successful interaction techniques does not come without introspection and reflection among staff (Foster, Citation2020; Salzmann-Erikson, Citation2018b, Citation2018a). Salzmann-Erikson (Citation2018a) studied ethical meetings among PICU staff, where participants described having ethical concerns about their own impact on patients’ experience of care. In situations involving coercive measures, staff justified these measures by referring to patients’ dignity and creating a safe environment. Another concern that staff expressed was that high workload could lead to increased impatience when responding to patients. Foster (Citation2020) found that, during a Nurse Development Program, staff were able to discuss patients’ challenging behavior, and “to consider their own responses and practice as a staff group” (Foster, Citation2020, p. 487). Communicating “behind the scenes” was also described in a study by Salzmann-Erikson (Citation2018b) based on observing shift reports. It was found that the reports involved nurses’ descriptions of patients’ situation, summarizing staff observations and associating or discussing strategies in forthcoming care for the next shift or following days. However, the formal reports mainly concerned practical tasks and medical-oriented information and dealt less with interactional strategies.

Relatives

Only one article addressed the perspective of relatives or family, that is, included them as study participants. Sedgwick et al. (Citation2019) introduced family meetings on weeknights for relatives of patients admitted at a PICU and reported on the family evaluations. While patients were allowed to participate in these meetings, no patients attended during the study period. All respondents found these meetings ‘very useful,’ as they gained an improved understanding of their ill relatives’ situation and difficulties. Moreover, they reported feeling included in care because they had been heard and their value for the patients had been recognized. The sessions also provided the relatives a space to ask questions that were not always appropriate to pose at the PICU due to the structure of ward rounds, etc.

Work models and developments

Articles in this theme were associated with PICU work models. This theme includes organization structures and developments as well as scales and assessments. Scales varied in focus: some addressed risk of violence and/or aggression, and some assessed and screened patients’ non-psychiatric health.

Organizational development

A nation-wide project in the Netherlands resulted in a new care model called High and Intensive Care (HIC) in psychiatry. The model has many similarities with PICUs, but stresses three features in particular: 1) admissions are a temporary break in out-patients’ care, 2) the practice of least restrictive measures is used, where patients are first admitted in the least restrictive areas ‘High Care Section,’ and if needed, temporarily placed in a ‘High Security Room,’ and 3) the aim is to minimize coercion in care and explicitly focus on recovery (van Melle et al., Citation2019). High Security Rooms are part of a broader HIC model, reserved for crisis situations when other options have failed, while seclusion rooms (in PICUs) are used more readily. Kucera et al. (Citation2022) reported results from an intervention study in which an acuity tool was implemented at a PICU, the intention being to increase nurses’ satisfaction at work. The nurses measured patients’ acuteness of the need for care every four hours on the variables: monitoring, aggression, unpredictable behavior, etc. The outcome of the intervention was measured using the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators (NDNQI); based on the outcome, the authors concluded that both nurses’ satisfaction and patient outcomes improved. The results were partly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. A brief report (Sethi et al., Citation2021) specifically drew attention to the pandemic, describing how COVID-19 changed PICU practice. They proposed an action model based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-testing results and infection symptoms. However, they emphasized the challenges of maintaining the philosophy of least restrictive interventions and adhering to infection protocols of isolation, the latter being especially restrictive for patients at a PICU because they are “heavily deprived of their personal liberty by the nature of being in an inpatient setting.” (Sethi et al., Citation2021, p. 6). Thompson et al. (Citation2021) investigated implementation of a PICU inside an adolescent psychiatric ward to improve care for patients who did not require intensive care and to improve quality of care for those who did. The PICU was evaluated based on safety metrics, and the authors found a significant decrease in restraints and damage of property on the general ward and a minor reduction of restraints at the PICU. In addition, due to implementing the PICU, the acuteness of the need for care of patients on the general ward decreased. Two articles addressed the aspects of healthcare economy. Moss et al. (Citation2023) used a novel approach and conducted a computer-simulated study to assess initiatives to reduce out-of-area admissions. These admissions are undesirable as it disrupts patients and families, higher costs, poor continuity of care and occupying beds from local admissions. Modeling suggested that it would be possible to reduce out-of-area placements by 26%. The negative effects of reduction of bed capacity, from 60 to 40 beds, in the UK was investigated by Cunningham et al. (Citation2021). Post-closure, patients experienced delays in transfer to a general psychiatric ward of 5.89–13.73 days at different measure points in the closure process. Another consequence was that discharges directly to patients’ home and not via a general ward increased from 14% to 32%.

Predicting aggression

Theruvath-Chalil et al. (Citation2020) introduced the Brøset Violence Checklist at a PICU and reported on its effectiveness, showing that scoring patients three times a day not only led to detection of risks, but also created awareness of a risk management plan. Other risk assessment tools were also found in the sample of articles. Pujol et al. (Citation2020) designed a new instrument to assess the risk of violent behavior at PICUs that resulted in a valid and reliable assessment scale: Evaluation of Risk of Aggressiveness. Ruud et al. (Citation2021) developed a checklist to measure seclusion, delineate seclusion elements, compare seclusion practices, and study the effects and experiences of seclusion.

Screening

Some articles focused on screening patients and developing assessment scales. Cooper et al. (Citation2018) investigated whether a standardized physical health assessment form would improve documentation of patients’ health history, lifestyle and examination. The implementation slightly improved documentation of past medical history, family history, quality of diet and exercise habits. The major difference was seen in the increase in systems reviews, which include, for example, neurological and gastrointestinal examinations. Covshoff et al. (Citation2023) explored to what extent sexual reproductive health (SRH) needs were met among female patients at a single-sex PICU. Due to symptom severity, 58.4% of the 77 patients were not able to undergo an SHR assessment. Covshoff et al. (Citation2023) reported that among 32 women who received an SHR assessment, 23 were found to have unmet SRH needs. Another study also reported the challenges involved in completing checklists. Howe et al. (Citation2018) developed the “Valproate checklist” to assess to what extent patients used contraception if they had been proscribed valproate; the research was conducted at a female-only PICU. They found that only three of 15 included patients were offered contraception after being prescribed Valproate. Nine of 15 patients did not complete the checklist, the main reason being that the patient lacked the capacity to do so. Similarly, Meggison et al. (Citation2021) employed a mnemonic-style documentation aid to improve the capture of ligature risk information in a CAMHS PICU setting.

Discussion

This integrative review set out to describe the focus in research on psychiatric intensive care and PICUs published during the past 5 years. A previous literature review found that PICU research has mainly focused on describing the PICU population in relation to sociodemographic variables and prevalence of violence (Bowers et al., Citation2008). The present review confirms that such descriptive studies are still being published and providing similar data (Accinni et al., Citation2022; Brown & Bass, Citation2004; Dolan & Lawson, Citation2001; Eaton et al., Citation2000; Gintalaite-Bieliauskiene et al., Citation2020; Hosalli et al., Citation2021; Jacobsen et al., Citation2019; Moyes et al., Citation2021; Okasha et al., Citation2021; Pereira et al., Citation2005; Saleem et al., Citation2019; Tarsitani et al., Citation2022; Ward & Prasad, Citation2021; Wynaden et al., Citation2001). Although no comparative statistical analysis can support the hypothesis that there are no significant differences between the PICU population publications from the beginning of the current millennium and the included articles, the interpretation of the data is that the population seems to have remained much the same in relation to sociodemographic characteristics, reasons for admission, length of stay, etc. Given the societal changes taking place, it is advisable to continue monitoring the PICU population in future research, especially because economic cutbacks in public healthcare were implemented many years ago and still apply today (Cunningham et al., Citation2021; Laugharne et al., Citation2016). The results indicate that appropriate nurse-patient ratios are essential for enabling the intensive level of care that defines PICUs (Foster & Smedley, Citation2019b; Price et al., Citation2018). However, the economic costs of maintaining high staffing levels creates tensions between clinical and fiscal considerations. The findings of Wolff et al. (Citation2015) and Evensen et al. (Citation2016) demonstrate the substantial economic costs associated with providing inpatient psychiatric care. As found by both studies, staff time is the major driver of direct treatment expenses. Very few studies reported on or examined factors related to staffing ratios in PICUs, representing a gap in the evidence base.

Research and it resulting publications originate from various clinical professions: medicine, nursing, psychology and occupational therapy. It has been highlighted that the clinical practice of psychiatric intensive care is challenging and that collaboration between professions is needed. The present analysis does not reveal to what extent research was multidisciplinary, as that question was beyond the scope of the analysis, but most of the research was conducted within single professions, rather than in multidisciplinary teams. For example, nursing studies tended to be carried out by nurse researchers studying nurses, while physician research was conducted by physicians studying treatment strategies and medical-focused interventions. Thus, it is recommended that researchers from different professions and academic fields join forces to further develop psychiatric intensive care, with a view to promoting the best interest of both patients and staff. Physicians’ focus leans toward pharmacological interventions (Casol et al., Citation2023; Winkler et al., Citation2011), epidemiology (Raaj et al., Citation2023; Tarsitani et al., Citation2022), screening (Cooper et al., Citation2018; Covshoff et al., Citation2023), and organizational issues (Thompson et al., Citation2021; van Melle et al., Citation2019). Nurses tend to focus more on relationships with patients (Foster & Smedley, Citation2019a; Price et al., Citation2018), patients’ perception of care (Allikmets et al., Citation2020), the daily flow at the PICUs (Salzmann-Erikson, Citation2018b), and introspection concerning their own practice (Salzmann-Erikson, Citation2018a). Several articles were brief reports but used experimental study designs. Although such studies do not provide any hard evidence, they do indicate important insights that may push the development of psychiatric intensive care forward. Even though one major problem is that brief reports have been published, few efforts have been made to conduct large-scale studies or RCTs. Another major concern about the publications is that most articles were not published as Open Access, which limits access to them for clinicians and researchers around the world.

Are we facing an era of emancipation for PICUs?

One group of research articles has reported on daily care at PICUs (Butler et al., Citation2020, Citation2020; Davies et al., Citation2020; Foster, Citation2020; Hochstrasser et al., Citation2018; Salzmann-Erikson, Citation2018a, Citation2018b), using the theme ‘everyday care.’ Within this theme, patients’ narratives about their experience of PICU admissions were reported in some articles, where the findings included: feelings of being abandoned, lack communication skills among staff, sense of being scrutinized by staff observations (Allikmets et al., Citation2020), and unclear rules or discrepancies in rules and policies (Hughes & Davies, Citation2018). These unfortunate results—which do not correspond to a recovery-oriented approach to care—have similarities with findings from previous research from the 1990s, which showed that nonprofessional, authoritative cultures existed on locked psychiatric wards (Morrison, Citation1990). It is tempting to believe that such a “tradition of toughness” (p. 32) did not survive the most recent millennium shift, but additional research has demonstrated that staff members’ behavior of disciplining and controlling patients has seeped into contemporary psychiatric care (Eivergård et al., Citation2021; Enarsson et al., Citation2011; Perron & Holmes, Citation2011; Salzmann-Erikson & Söderqvist, Citation2017). As a response to the medicalization of psychiatric care, the recovery movement—which began in the 1980s and gained attention and acceptance in psychiatric care as part of an attempt to upset the traditional power balance between “staff and patients”—opposes an Apollonian worldview as the norm in Anglo-Saxon healthcare, a worldview that promotes governance, logic, truth, and predictability. The recovery movement has been driven by emancipating ideas (Salzmann-Erikson, Citation2013; Slade, Citation2009) in which patients are responsible for the own recovery. In a review of previous research published prior to the articles included in the present review, care models were found that support a mere libertarian view of psychiatric care. This is exemplified in several publications in which the following statements were made concerning the use of seclusion and restraints: “least restrictive measure” or “the last resort” (Steinert et al., Citation2013; Tulloch et al., Citation2022).

A more overarching trend in general psychiatric care is the adoption of a person-centered approach—a trend that has been fueled along with (personal) recovery theories (Ehrlich et al., Citation2022; Slade, Citation2009). Henceforward, ethical concerns and issues have been strongly raised regarding the use of coercive measures, as such measures contradict nursing values (Eren, Citation2014; Happell & Harrow, Citation2010; Stevenson et al., Citation2015; Terkelsen & Larsen, Citation2016) and the idea of libertarianism. The practice of strict ‘nursing regimes’—strict ward rules, controlling, limit setting, zero-tolerance, disrespect and stigmatization—is described in the literature as still existing in contemporary psychiatric nursing (Carlsson et al., Citation2006; Eren, Citation2014; Usher et al., Citation2005; Vatne & Fagermoen, Citation2007). Nonetheless, such ‘toxic cultures’ have not escaped criticism (Crichton, Citation1997; Holmes, Citation2005; Vatne & Fagermoen, Citation2007). In line with authoritarian thinking, the idea of sensory deprivation was presented in two Norwegian studies (Norvoll et al., Citation2017; Vaaler et al., Citation2006). Previous research in the field of PICU has predominantly focused on epidemiological studies of the PICU population, its characteristics, presence of violence and ‘manageable techniques and pharmacological interventions,’ but has only rarely done so from the patients’ perspective. Among the few studies available, Salzmann-Erikson and Söderqvist (Citation2017) reported that being hospitalized in a PICU was a life-changing event. The results showed that patients felt confined, had limited access to information about their own care, limited access to staff, and limited freedom and autonomy. Recently, Berg et al. (Citation2022) published a literature review describing nurses’ and patients’ perceptions of PICU care. They found that patients were not satisfied with care due to feelings of abandonment and insecurity, although patients did express some positive feelings. In stark contrast to sensory deprivation and unappreciated interiors, sensory rooms were introduced as an alternative (Novak et al., Citation2012; Smith & Jones, Citation2014). Björkdahl et al. (Citation2016) reported on staff members’ perceptions of using sensory rooms and found that it not only benefited the individual patient, but also had positive effects on the general ward environment. Lastly, although tensions remain regarding how to integrate emancipatory values within PICUs, as evidenced by ongoing reports of controlling practices counter to ideals of self-direction, PICU initiatives have moved toward more emancipatory, empowerment-focused models that promote patient autonomy and responsibility in shaping their own recovery journey.

Limitations

The search terms were limited to narrow the records. A broader search would have yielded many more articles, potentially including those with PICU in the sample, but not necessarily focused on PICUs. Such findings could have provided additional insights into the field of PICU research. Non-original research papers were excluded, and opinions, discussion papers, and editorials, while likely informative about the current view on PICU, were not aligned with the aim of the review.

In the original search, 219 total articles were identified before applying inclusion criteria, indicating a substantial body of literature exists beyond the 47 articles that met criteria for the 5-year filtered review. Clearly, an expansive publication date range could be justified for a comprehensive portrayal of the evidence. However, it is believed that the current focused review provides value in summarizing current research directions, which can inform future practice and study. The concentrated analysis of 47 carefully selected articles, adhering to clear eligibility criteria allows for an in-depth synthesis and critique of the contemporary literature to be provided. One challenge throughout the present integrative review was that the articles employed different variables and measures, making it difficult to conduct meta-analyses and generate evidence-based knowledge. An additional limitation of the review is that this is a single-author article. Moreover, even though the scope of the review included articles from various academic subjects areas, the nursing database Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL) was not used. Despite this, several articles with a nursing focus were included, as many journals in which nurses choose to publish are also indexed in the chosen databases. Due to this limitation, a consequence analysis of opting out CINAHL was done. A retrospective search in CINAHL resulted in 62 records. After screening for duplications, two were found to meet the inclusion criteria. This is considered a weakness, but the consequences are assessed as minor. This single-author article may reflect inherent biases in interpretation. However, the ontological goal of an integrative review is not to find an objective, synthesized truth within a dataset. Rather, it is to offer a credible interpretation of existing research. To increase the credibility of the present analysis, the research process and findings were scrutinized by research peers external to the project. This form of audit by uninvolved colleagues resembles the external auditing process used to verify research credibility.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this review has synthesized current evidence across disciplines to reveal a complex narrative surrounding contemporary PICU care. While initial recovery-oriented initiatives have emerged, promoting more emancipatory models of patient empowerment and responsibility, substantial tensions persist. Ongoing reports of restrictive, controlling practices counter to ideals of self-direction indicate full integration of recovery values within PICU environments remains limited and inconsistent. However, the increasing attention to humane, person-centered care philosophy in recent literature provides hope for continued evolution toward more liberation-focused approaches that uplift both patients and providers. Realization of truly emancipatory PICU care will require commitment across system levels and disciplines to transform long-entrenched institutional cultures. By illuminating where progress has and has not yet been made, this review provides direction for next steps in research, policy, education, and practice to advance equitable, recovery-oriented psychiatric intensive care.

Relevance to clinical practice

When considering PICU research at an aggregated level, which is done in the present review, it is recommended that more interdisciplinary research is needed to cover areas that are being neglected: patient recovery and involvement in care, staff members’ occupational health, and inclusion of relatives in care planning. In doing so, psychiatric intensive care could leave behind its oppressive and distanced approach and instead move forward to a more integrative level where both patients and staff are valued as human beings. The current review adds to the current body of knowledge that: a) Research and it resulting publications originate from various clinical professions: medicine, nursing, psychology and occupational therapy; b) several articles are brief reports but used experimental study designs; and c) nursing research tend to focus on relationships with patients, patients’ perception of care, the daily flow at the PICUs, and introspection concerning their own practice.

Study registration

None.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not relevant for an integrative review.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

This is a single-author review.

Authorships

Martin Salzmann-Erikson is the only author of this manuscript.

Research ethics and patient consent

This research does not involve human participants.

Acknowledgments

To my reviewing colleagues at the higher research seminar.

Disclosure statement

The author declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Additional information

Funding

References

- Accinni, T., Frascarelli, M., Vecchioni, S., Tarsitani, L., Biondi, M., & Pasquini, M. (2022). Gender modulation of psychopathological dimensions associated to suicidality | Modulazione della variabile di genere sulle dimensioni psicopatologiche associate alla suicidalità. Rivista di psichiatria, 57(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1708/3749.37324

- Allikmets, S., Marshall, C., Murad, O., & Gupta, K. (2020). Seclusion: A patient perspective. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 41(8), 723–735. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2019.1710005

- Ash, D., Suetani, S., Nair, J., & Halpin, M. (2015). Recovery-based services in a psychiatric intensive care unit—The consumer perspective. Australasian Psychiatry: Bulletin of Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, 23(5), 524–527. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856215593397

- AusHFG. (2016). Mental health intensive care unit (0137; Part B - health facility briefing and planning). Australasian Health Facility Guidelines. https://aushfg-prod-com-au.s3.amazonaws.com/HPU_B.0137_2_0.pdf

- Barker, P. (2003). The tidal model: Psychiatric colonization, recovery and the paradigm shift in mental health care. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 12(2), 96–102. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-0979.2003.00275.x

- Barker, P., & Buchanan-Barker, P. (2010). The tidal model of mental health recovery and reclamation: Application in acute care settings. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 31(3), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840903276696

- Berg, J., Noora, G., Kaisa, M., Heikki, E., & Mari, L. (2022). Nurses’ and patients’ perceptions about psychiatric intensive care—An integrative literature review. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 43(11), 983–995. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2022.2101079

- Björkdahl, A., Olsson, D., & Palmstierna, T. (2006). Nurses’ short-term prediction of violence in acute psychiatric intensive care. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 113(3), 224–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00679.x

- Björkdahl, A., Perseius, K.-I., Samuelsson, M., & Lindberg, M. H. (2016). Sensory rooms in psychiatric inpatient care: Staff experiences: Sensory rooms in psychiatric care. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 25(5), 472–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12205

- Bowers, L. (2012). What are PICUs for? Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 8(2), 62–65. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742646412000179

- Bowers, L., Alexander, J., Bilgin, H., Botha, M., Dack, C., James, K., Jarrett, M., Jeffery, D., Nijman, H., Owiti, J. A., Papadopoulos, C., Ross, J., Wright, S., & Stewart, D. (2014). Safewards: The empirical basis of the model and a critical appraisal: Safewards: Evidence and appraisal. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 21(4), 354–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12085

- Bowers, L., Jeffery, D., Bilgin, H., Jarrett, M., Simpson, A., & Jones, J. (2008). Psychiatric intensive care units: A literature review. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 54(1), 56–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764007082482

- Brown, S., & Bass, N. (2004). The psychiatric intensive care unit (PICU): Patient characteristics, treatment and outcome. Journal of Mental Health, 13(6), 601–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638230400017095

- Brown, S., Chhina, N., & Dye, S. (2010). Use of psychotropic medication in seven English psychiatric intensive care units. The Psychiatrist, 34(4), 130–135. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.108.023762

- Butler, S., Adeduro, R., Davies, R., Nwankwo, O., White, N., Shaw, T. A., Skelton, L., Shannon, G., Smale, E., Corrigan, M., Martin, D., & Sethi, F. (2020). Art and mental health in the women’s psychiatric intensive care unit. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 16(1), 15–22. https://doi.org/10.20299/jpi.2019.015

- Carlsson, G., Dahlberg, K., Ekebergh, M., & Dahlberg, H. (2006). Patients longing for authentic personal care: A phenomenological study of violent encounters in psychiatric settings. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 27(3), 287–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840500502841

- Casol, M., Tong, A., Ng, J. C. Y., & McGloin, R. (2023). Characterization of psychotropic PRN medications in a Canadian psychiatric intensive care unit. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 29(2), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078390321994668

- Challinor, A., Lewis, E., Mitchell, A., & Williams, D. (2021). Reducing delays in the transfer of patients from psychiatric intensive care units (PICU) to acute inpatient services: A quality improvement project. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 17(2), 99–106. https://doi.org/10.20299/jpi.2021.001

- Chompoosri, P., & Kunchanaphongphan, T. (2020). Factors associated with prolonged psychiatric intensive care unit admission at Somdet Chaophraya Institute of Psychiatry, Thailand. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 16(1), 9–14. https://doi.org/10.20299/jpi.2020.003

- Citrome, L., Green, L., & Fost, R. (1994). Length of stay and recidivism on a psychiatric intensive care unit. Hospital & Community Psychiatry, 45(1), 74–76. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.45.1.74

- Cohen, S., & Khan, A. (1990). Antipsychotic effect of milieu in the acute treatment of schizophrenia. General Hospital Psychiatry, 12(4), 248–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/0163-8343(90)90062-H

- Cooper, C., Madhavan, G., & Choong, L. S. (2018). Re-audit of physical health monitoring for adult inpatients on a psychiatric intensive care unit. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 14(1), 33–38. https://doi.org/10.20299/jpi.2017.011

- Covshoff, E., Blake, L., Rose, E. M., Bolade, A., Rathouse, R., Wilson, A., Cotterell, A., Pittrof, R., & Sethi, F. (2023). Sexual and reproductive health needs assessment and interventions in a female psychiatric intensive care unit. BJPsych Bulletin, 47(1), 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2021.107

- Crichton, J. (1997). The response of nursing staff to psychiatric inpatient misdemeanour. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry, 8(1), 36–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585189708411993

- Cullen, A. E., Bowers, L., Khondoker, M., Pettit, S., Achilla, E., Koeser, L., Moylan, L., Baker, J., Quirk, A., Sethi, F., Stewart, D., McCrone, P., & Tulloch, A. D. (2018). Factors associated with use of psychiatric intensive care and seclusion in adult inpatient mental health services. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 27(1), 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796016000731

- Cunningham, R., Kranidiotis, L., & Walker, T. (2021). A study of admissions to a PICU in a Trust that has undergone significant bed closures and other service re-design. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 17(1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.20299/jpi.2020.018

- Davies, R., Murphy, K., & Sethi, F. (2020). Sensory room in a psychiatric intensive care unit. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 16(1), 23–28. https://doi.org/10.20299/jpi.2019.016

- Dolan, M., & Lawson, A. (2001). Characteristics and outcomes of patients admitted to a psychiatric intensive care unit in a medium secure unit. Psychiatric Bulletin, 25(8), 296–299. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.25.8.296

- Eaton, S., Ghannam, M., & Hunt, N. (2000). Prediction of violence on a psychiatric intensive care unit. Medicine, Science, and the Law, 40(2), 143–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/002580240004000210

- Ehrlich, C., Lewis, D., New, A., Jones, S., & Grealish, L. (2022). Exploring the role of nurses in inpatient rehabilitation care teams: A scoping review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 128, 104134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.104134

- Eivergård, K., Enmarker, I., Livholts, M., Aléx, L., & Hellzén, O. (2021). Disciplined into good conduct: Gender constructions of users in a municipal psychiatric context in Sweden. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 30(15-16), 2258–2269. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15666

- Enarsson, P., Sandman, P.-O., & Hellzén, O. (2011). “They can do whatever they want”: Meanings of receiving psychiatric care based on a common staff approach. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 6(1), 5296. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v6i1.5296

- Eren, N. (2014). Nurses’ attitudes toward ethical issues in psychiatric inpatient settings. Nursing Ethics, 21(3), 359–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733013500161

- Evensen, S., Wisløff, T., Lystad, J. U., Bull, H., Ueland, T., & Falkum, E. (2016). Prevalence, employment rate, and cost of schizophrenia in a high-income welfare society: A population-based study using comprehensive health and welfare registers. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 42(2), 476–483. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbv141

- Foster, C. (2019). Investigating professional quality of life in nursing staff working in adolelscent Psychiatric Intensive Care Units (PICUs). The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 14(1), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMHTEP-04-2018-0023

- Foster, C. (2020). Investigating the impact of a psychoanalytic nursing development group within an adolescent psychiatric intensive care unit (PICU). Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 34(6), 481–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2020.08.008

- Foster, C., & Smedley, K. (2016). Understanding the nature of mental health nursing within adolescent PICU and identifying nursing interventions that contribute to the recovery journey of yung people (Phase Report 1; pp. 1–53). University of Salford and The Priory Hospital Cheadle Royal.

- Foster, C., & Smedley, K. (2019a). Understanding the nature of mental health nursing within CAMHS PICU: 1. Identifying nursing interventions that contribute to the recovery journey of young people. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 15(2), 87–102. https://doi.org/10.20299/jpi.2019.012

- Foster, C., & Smedley, K. (2019b). Understanding the nature of mental health nursing within CAMHS PICU: 2. Staff experience and support needs. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 15(2), 103–115. https://doi.org/10.20299/jpi.2019.013

- Gaudiano, B. A., Ellenberg, S., Ostrove, B., Johnson, J., Mueser, K. T., Furman, M., & Miller, I. W. (2020). Feasibility and preliminary effects of implementing acceptance and commitment therapy for inpatients with psychotic-spectrum disorders in a clinical psychiatric intensive care setting. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 34(1), 80–96. https://doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.34.1.80

- Georgieva, I., de Haan, G., Smith, W., & Mulder, C. L. (2010). Successful reduction of seclusion in a newly developed psychiatric intensive care unit. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 6(01), 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742646409990082

- Gintalaite-Bieliauskiene, K., Dixon, R., & Bennett, L. (2020). A retrospective survey of care provided to patients with borderline personality disorder admitted to a female psychiatric intensive care unit. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 16(1), 35–42. https://doi.org/10.20299/jpi.2020.002

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Hafner, R. J., Lammersma, J., Ferris, R., & Cameron, M. (1989). The use of seclusion: A comparison of two psychiatric intensive care units. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 23(2), 235–239. https://doi.org/10.3109/00048678909062140

- Happell, B., & Harrow, A. (2010). Nurses’ attitudes to the use of seclusion: A review of the literature. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 19(3), 162–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2010.00669.x

- Harries, B., Skelton, L., Blake, L., Pugh, R., Butler, M., Bolade, A., Rathouse, R., & Sethi, F. (2021). The psychological impact of COVID-19 on staff and patients in a psychiatric intensive care setting. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 17(1), 5–10. https://doi.org/10.20299/jpi.2020.016

- Hawsawi, T., Stein‐Parbury, J., Orr, F., Roche, M., & Gill, K. (2021). Exploring recovery‐focused educational programmes for advancing mental health nursing: An integrative systematic literature review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 30 Suppl 1(S1), 1310–1341. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12908

- Hedlund Lindberg, M., Samuelsson, M., Perseius, K., & Björkdahl, A. (2019). The experiences of patients in using sensory rooms in psychiatric inpatient care. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28(4), 930–939. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12593

- Hetrick, S. E., Parker, A. G., Callahan, P., & Purcell, R. (2010). Evidence mapping: Illustrating an emerging methodology to improve evidence-based practice in youth mental health: Evidence mapping in youth mental health. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 16(6), 1025–1030. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01112.x

- Hochstrasser, L., Voulgaris, A., Möller, J., Zimmermann, T., Steinauer, R., Borgwardt, S., Lang, U. E., & Huber, C. G. (2018). Reduced frequency of cases with seclusion is associated with “opening the doors” of a psychiatric intensive care unit. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9(FEB), 57. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00057

- Holmes, D. (2005). Governing the captives: Forensic psychiatric nursing in corrections. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 41(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0031-5990.2005.00007.x

- Hosalli, P., Cardno, A., Brewin, A., Nazari, J., Clapcote, S. J., Inglehearn, C. F., & Mahmood, T. (2021). Risk of psychosis in Yorkshire African, Caribbean and mixed ethnic communities. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 17(2), 107–111. https://doi.org/10.20299/jpi.2021.005

- Howe, A., Nasreen, R., Brammer, F., Varma, S., & Sethi, F. (2018). The valproate checklist in a female psychiatric intensive care unit. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 14(1), 39–45. https://doi.org/10.20299/jpi.2017.013

- Hughes, J. A., & Davies, B. E. (2018). Developing a ward ethos based on positive behavioural support within a forensic mental health ‘psychiatric intensive care unit. Mental Health & Prevention, 10, 28–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2018.03.003

- Ibrahim, N., Ghallab, E., Ng, F., Eweida, R., & Slade, M. (2022). Perspectives on mental health recovery from Egyptian mental health professionals: A qualitative study. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 29(3), 484–492. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12754

- Iversen, V. C., Aasen, O. H. F., Cüneyt Güzey, I., & Helvik, A.-S. (2016). Incidence of violent behavior among patients in psychiatric intensive care units. European Journal of Psychiatry, 30(1), 67–78.

- Jacobsen, P., McCrum, R. L., Gee, S., & Philpott, R. (2019). Clinical profiles of people with persecutory vs grandiose delusions who engage in psychological therapy during an acute inpatient admission. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 15(2), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.20299/jpi.2019.009

- Joanna Briggs Institute. (2014). Reviewers’ manual. The University of Adelaide. https://nursing.lsuhsc.edu/JBI/docs/ReviewersManuals/ReviewersManual.pdf

- Jones, J. R. (1985). The psychiatric intensive care unit. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 146(5), 561–562. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.146.5.561b

- Kasmi, Y. (2010). Profiling medium secure psychiatric intensive care unit patients. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 6(2), 65–71. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742646409990185

- Khangura, S., Konnyu, K., Cushman, R., Grimshaw, J., & Moher, D. (2012). Evidence summaries: The evolution of a rapid review approach. Systematic Reviews, 1(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-1-10

- Koppelmans, V., Schoevers, R., van Wijk, C. G., Mulder, W., Hornbach, A., Barkhof, E., Klaassen, A., van Egmond, M., van Venrooij, J., Bijpost, Y., Nusselder, H., van Herrewaarden, M., Maksimovic, I., Achilles, A., & Dekker, J. (2009). The Amsterdam Studies of Acute Psychiatry—II (ASAP-II): A comparative study of psychiatric intensive care units in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health, 9(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-318

- Kucera, P., Kingston, E., Ferguson, T., Jenkins, K., Fogarty, M., Sayles, H., & Cohen, M. Z. (2022). Effects of implementing an acuity tool on a psychiatric intensive care unit. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 37(4), 313–318. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000652

- Langsrud, K., Kallestad, H., Vaaler, A., Almvik, R., Palmstierna, T., & Morken, G. (2018). Sleep at night and association to aggressive behaviour; Patients in a psychiatric intensive care unit. Psychiatry Research, 263, 275–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.03.012

- Langsrud, K., Vaaler, A., Morken, G., Kallestad, H., Almvik, R., Palmstierna, T., & Güzey, I. C. (2019). The predictive properties of violence risk instruments may increase by adding items assessing sleep. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10(MAY), 323. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00323

- Laugharne, R., Branch, M., Mitchell, A., Parkin, L., Confue, P., Shankar, R., Wilson-James, D., Marshall, M., Edgecombe, M., Keaney, B., Gill, K., & Harrison, J. (2016). What happens when 55% of acute psychiatric beds are closed in six days: An unexpected naturalistic observational study. JRSM Open, 7(10), 2054270416649280. https://doi.org/10.1177/2054270416649280

- Mark, I., Bell, D., Kirsh, L., & O'Brien, A. (2021). The use of virtual reality in a psychiatric intensive care unit: A pilot study. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 17(2), 123–128. https://doi.org/10.20299/jpi.2021.008

- McAllister, S., & McCrae, N. (2017). The therapeutic role of mental health nurses in psychiatric intensive care: A mixed-methods investigation in an inner-city mental health service. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 24(7), 491–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12389

- Meggison, N., Anyameluhor, F., El-Ahmar, H., & Morley, L. (2021). Ligature Record: improved capture of risk information in CAMHS PICU using a mnemonic-style documentation aid. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 17(2), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.20299/jpi.2021.007

- Mele, F., Buongiorno, L., Montalbò, D., Ferorelli, D., Solarino, B., Zotti, F., Carabellese, F. F., Catanesi, R., Bertolino, A., Dell’Erba, A., Dell’Erba, A., & Mandarelli, G. (2022). Reporting incidents in the psychiatric intensive care unit: A retrospective study in an Italian University Hospital. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 210(8), 622–628. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000001504

- Mitchell, G. D. (1992). A survey of psychiatric intensive care units in Scotland. Health Bulletin, 50(3), 228–232.

- Morrison, E. F. (1990). The tradition of toughness: A study of nonprofessional nursing care in psychiatric settings. Image-the Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 22(1), 32–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.1990.tb00166.x

- Moss, S. J., Vasilakis, C., & Wood, R. M. (2023). Exploring financially sustainable initiatives to address out-of-area placements in psychiatric ICUs: A computer simulation study. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 32(3), 551–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2022.2091769

- Moyes, H. C. A., MacNaboe, L., & Townsend, K. (2021). The rate and impact of substance misuse in psychiatric intensive care units (PICUs) in the UK. Advances in Dual Diagnosis, 14(4), 198–216. https://doi.org/10.1108/ADD-06-2021-0008

- Mustafa, F. A. (2017). Impact of sudden expansion of catchment area on admissions to a psychiatric intensive care unit. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 53(4), 337–341. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12185

- Myhre, M. Ø., Strømgren, B., Arnesen, E. F., & Veland, M. C. (2018). The feasibility of brief behavioural activation treatment for depression in a PICU: A systematic replication. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 14(1), 15–23. https://doi.org/10.20299/jpi.2018.001

- NAPICU. (2014). National minimum standards for psychiatric intensive care in general adult services. https://napicu.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/NMS-2014-final.pdf

- Norvoll, R., Hem, M. H., & Pedersen, R. (2017). The role of ethics in reducing and improving the quality of coercion in mental health care. HEC Forum: An Interdisciplinary Journal on Hospitals’ Ethical and Legal Issues, 29(1), 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10730-016-9312-1

- Novak, T., Scanlan, J., McCaul, D., MacDonald, N., & Clarke, T. (2012). Pilot study of a sensory room in an acute inpatient psychiatric unit. Australasian Psychiatry: Bulletin of Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, 20(5), 401–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856212459585

- O'Brien, L., & Cole, R. (2004). Mental health nursing practice in acute psychiatric close-observation areas. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 13(2), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-0979.2004.00324.x

- Okasha, T. A., Sabry, W. M., Zaki, N. H., Rabie, M. A., & Elhawary, Y. A. (2021). Characteristics and outcomes of patients admitted to the first psychiatric intensive care unit in Egypt. The South African Journal of Psychiatry: SAJP: The Journal of the Society of Psychiatrists of South Africa, 27, 1527. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v27i0.1527

- Onyon, R., Khan, S., & George, M. (2006). Delayed discharges from a psychiatric intensive care unit – Are we detaining patients unlawfully? Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 2(02), 59–64. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742646407000301