Abstract

Background

The issue of dual diagnosis continues to be a global health concern. There is a lack of empirical research on mental health nurses’ attitudes toward consumers with dual diagnosis.

Objective

This study aimed to answer the following research question: How do mental health nurses describe their attitude toward consumers with co-existing mental health and drug and alcohol problems?

Design

This qualitative study employed purposive sampling to recruit participants. Semi-structured interviews were conducted to explore mental health nurses’ attitudes toward consumers with dual diagnosis.

Setting

This study focused on mental health nurses employed in mental health settings. It placed a particular emphasis on mental health nurses who had experience in caring for consumers with dual diagnosis. Seventeen mental health nurses participated in the interview.

Methods

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and coded using NVivo™ 12 Plus software. Thematic analysis was used to generate codes and themes inductively.

Results

Three major themes with a total of eight sub-themes were identified: (1) satisfaction and connection, with three subthemes; (2) combating negativity in others, with two subthemes; and (3) working to improve outcomes, with three subthemes.

Conclusions

Participants were concerned about their peers’ sense of fear and frustration, stigmatized language, and lack of consistency in providing dual diagnosis training for mental health nurses. There is a need to investigate effective strategies to address mental health nurses’ stigmatized attitudes, fear, and frustration toward consumers with dual diagnosis.

1. Introduction

Mental, neurological, and substance use disorders affect almost one billion people worldwide (World Health Statistics, Citation2022). As of 2019, this accounts for 10% of the global burden of disease and 25% of the number of years lived with disability. Substance use is a major contributor to ill health and death worldwide settings (WHO, Citation2019). Co-occurring mental health and drug and alcohol problems or dual diagnosis is a term used to describe simultaneous alcohol/drug problems and mental health problems within psychiatric/mental health settings (WHO, Citation2019). Approximately 10% of the global disease burden is attributed to dual diagnosis, while 30% is attributed to non-fatal diseases (WHO, Citation2022).

The prevalence of consumers with dual diagnosis is high (De Ruysscher et al., Citation2019), and caring for these consumers can be complex and challenging (de Waal et al., Citation2019; Lopes & Freitas, Citation2022; Toftdahl et al., Citation2016). The prevalence of mental disorders among Australians aged 16–85 years is estimated to be over two-in-five (43.7% or 8.6 million people) (AIHW, Citation2022). In Australia, an estimated 4.2 million individuals (21.4%) experience mental disorders at some point during their lifetime in 2020–2021 and 3.3% of those aged 16–85 (650,800 people) had a substance use illness within the past 12 months (AIHW, Citation2022). It was reported that there is an influx of emergency admissions of consumers to Australian hospitals in 2014–2015 was due to psychological and behavioral problems caused by illegal substance use (AIHW, Citation2018).

Consumers with dual diagnosis exhibit higher health and social risks, including homelessness, illegal behavior, homicide, and suicide (Hamdan-Mansour et al., Citation2018; Iheanacho et al., Citation2020; Priebe et al., Citation2018). Moreover, these consumers have many health concerns and complex needs (Ortega & Ventura, Citation2013). Due to their complex social and health care needs, people with substance use disorders frequently present in the health services settings (WHO, Citation2022). Although effective and brief treatments are available and recommended, they are not widely covered (WHO, Citation2022) and these consumers also tend to experience more stigma than individuals with any other health problem (Livingston et al., Citation2012).

Nurses generally are the largest professional group within the healthcare system (Garrod et al., Citation2020). Mental health nurses portray a crucial part in providing care to consumers with dual diagnosis (Chicoine et al., Citation2023; Smyth et al., Citation2019). To provide such care, there is a need for mental health nurses to be well-prepared to provide care to consumers with dual diagnosis (Russell et al., Citation2017; Worley, Citation2019). Moreover, the attitudes of mental health nurses toward these consumers can affect the consumers’ involvement in treatment and recovery (Estreet & Privott, Citation2021; Peters et al., Citation2017). According to Farley-Toombs (Citation2012), nurses’ attitudes and stigma surrounding consumers with dual diagnosis influence therapeutic relationships. In addition, discriminating in providing nursing care to these consumers can have long-term consequences, affecting consumers’ life goals, community relations, and support (Lucksted & Drapalski, Citation2015). It is essential to provide specialized treatment for consumers with dual diagnosis; for this to be successful, mental health nurses must have adequate knowledge, skills, attitudes, empathy and self-efficacy. It can be argued that a lack of positive attitudes, empathy, and low self-efficacy may lead to poor nurse-consumer therapeutic relationships and poor therapeutic outcomes.

People’s attitudes are determined by their opinions of acceptable or unacceptable behavior (Maio & Haddock, Citation2012). As a result of one’s attitude, one may respond positively or negatively to an object, person, institution, or event (Ajzen & Fishbein, Citation1980). Different attitudes and traits influence an individual’s specific behaviors (Ajzen & Fishbein, Citation1980). It is possible to evaluate attitudinal behaviors whether it is positive or negative (Ajzen & Fishbein, Citation1980). The present study explored the nature of those behavior-related factors—namely, the attitudes of mental health nurses regarding consumers with dual diagnosis, based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen & Fishbein, Citation2005). The TPB predicts and rationalizes human behavior in selected circumstances.

Before conducting this study, a scoping review of the literature was undertaken. The scoping review followed the Joanna Briggs Institute approach to scoping studies (Peters et al., Citation2015). The scoping review identified twenty studies for final reporting. Key finding is provided in . Studies reported in the scoping review had multiple gaps. Study designs were unbalanced, selection bias existed, attrition rates were high, and there were very low response rates and mental health nurses were underrepresented. Further, the attitudes of mental health nurses toward consumers with dual diagnosis have not been validated in follow-up studies, and most studies were conducted over a decade ago. The literature needs to provide a well-rounded picture of mental health nurses’ attitudes toward consumers with dual diagnosis. It is crucial to ensure that mental health nurses provide equal and unbiased care to all consumers with dual diagnosis, regardless of mental health status. It is socially and economically detrimental to neglect the well-being of these consumers (WHO, Citation2020).

Table 1. Key findings from scoping review of the literature.

2. Study aim

This study aimed to answer the following research question: How do mental health nurses describe their attitude toward consumers with co-existing mental health and drug and alcohol problems?

3. Methods

There were multiple gaps in the studies reported in the scoping review. There is a need to provide a comprehensive picture of mental health nurses’ attitudes toward consumers with dual diagnosis. This qualitative study used an essentialist approach (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) because little is known about mental health nurses’ attitudes toward consumers with dual diagnosis. This research was guided by an essentialist epistemology that informs how data are interpreted and meaning derived from them. It is possible to theorize motivations, experiences, and purpose using an essentialist approach.

3.1. Data collection

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Federation University Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval number: A19-026). Purposive sampling, whereby participants were carefully chosen based on their knowledge and experience of the topic being studied (Lopez & Whitehead, Citation2013), allowed this study to collect valuable information while optimizing available resources (Etikan et al., Citation2016). The study recruited mental health nurses who had experience working with consumers with dual diagnosis. This enabled the researchers to obtain meaningful perspectives from participants with relevant expertise. This study used maximum variation sampling to ensure the representativeness and diversity of individual mental health nurses and mental health settings. This study also used snowball sampling. This approach involved collecting data from initial participants and using their connections to introduce the research to other potential participants (Lopez & Whitehead, Citation2013). This approach helped to expand the sample size and diversity. Information-rich cases may be interpreted more deeply than empirical generalizations (Etikan et al., Citation2016; Lopez & Whitehead, Citation2013).

Mental health nurses who wanted to take part in the research were contacted via email and phone calls. Further, the study was advertised on the website of the Australian College of Mental Health Nurses Inc. (The Australian College of Mental Health Nurses Inc. is Australia’s peak mental health nurses’ association.) and social media. In the invitation letter and plain language statement, it was clearly stated that this study would only recruit mental health nurses with experience working with consumers who have co-occurring mental health and drug and alcohol problems. It was confirmed with the interviewees before the interview process began. A total of 33 mental health nurses agreed to participate in the interview. However, due to COVID 19 restrictions, 17 nurses were interviewed over the telephone. Participants were not provided with any incentives. Data collection took place from 17 July 2020 to 6 October 2020. A detailed information on the research was provided to participants. A semi-structured interview schedule was used (see ). The interviews lasted between 30 and 60 min. Participants were encouraged to share their opinions and experiences regarding consumers with dual diagnosis. Data collection ceased once data saturation was reached.

Table 2. Semi-structured interview questions used to explore mental health nurses’ attitudes toward consumers with dual diagnosis.

3.2. Data analysis

A six-step thematic analysis method was utilized (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). In step one, all interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim via NVivo™ 12 Plus Version (QSR International, Citation2018). To protect participants’ privacy, their names were encoded using pseudonyms. The transcripts were reviewed again to ensure their accuracy. In step two, we generated initial codes via an auto-coding method using NVivo™ 12 Plus. Large amounts of data can be quickly analyzed, and themes identified with NVivo’s automated tools. By importing files automatically, nodes can be created for entire files. The term “node” refers to a collection of references related to certain topics, places, people, or other areas of interest (NVivo™). From interview transcripts, nodes were gathered for this study. The Auto Code Wizard options were used to accomplish this. In step three, 40 auto-coded items were collected, and a search was conducted for potential themes based on these codes. In step four, three major themes were identified. We identified 71 aggregated codes for the first theme, 76 for the second theme, and 130 for the third theme. In step five, the themes were refined and named. In step six, themes were reported and arranged as per the research questions and prior literature. Inductive approaches were incorporated into the theme-building process. All data were stored securely according to university policy. Two researchers proficient in qualitative research examined interview transcriptions and themes, and any inconsistencies were resolved through several discussions.

We followed the guidelines outlined in Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) (Tong et al., Citation2012).

4. Results

4.1. Participant characteristics

Participants’ demographic characteristics are presented in . All participants had at least 10 years of experience working in the area. Participants worked in a range of mental health settings (e.g. acute and community mental health units, emergency departments, homeless services, people with HIV, forensic mental health, youth, adults, adolescents, generalist hospitals, geriatrics, brain disorders units, drug and alcohol units, medically supervised injecting clinics).

Table 3. Attitude interview sample characteristics (n = 17).

5. Themes

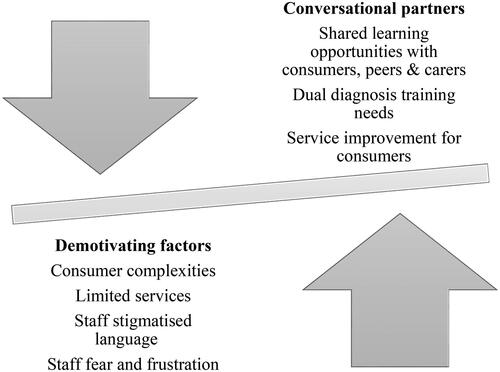

Three main themes and eight subthemes emerged from the data (see ): (1) satisfaction and connection, with three subthemes; (2) combating negativity in others, with two subthemes; and (3) working to improve outcomes, with three subthemes. These themes and subthemes are discussed below.

Table 4. Themes and subthemes.

5.1. Satisfaction and connection

This theme describes participants’ knowledge about dual diagnosis, their job satisfaction, and how they therapeutically engage with consumers with dual diagnosis. This theme had three subthemes: enjoying collaborating with the marginalized community, fascinated to see consumer recovery, and listening to the whole story.

5.1.1. Enjoy collaborating with the marginalized community

This subtheme describes participants’ work satisfaction and confidence when treating consumers with dual diagnosis. Participants stated that they are confident and enjoy working with these consumers, even though it can be challenging at times:

I feel confident with working with people [consumers with dual diagnosis] who present with significant drug and alcohol issues or mental health issues. I prefer working people who have at least hope, the most chaotic, the most challenging, the most difficult clients because I think the bar for improvement is very low. (Austin)

I am very satisfied, especially if I can help them [consumers with dual diagnosis]. I was able to settle them down, settling their emotions or mood, providing the care, is rewarding for me. (Luca)

I have the best team in the world… It took us [the team] a couple of years to break the ice, to get people to feel confident in what we are doing and our recommendations. (Georgia)

5.1.2. Fascinated to see consumer recovery

This subtheme describes participants’ motivation toward treating consumers with dual diagnosis. Participants are motivated to provide high standards of care and treatment, regardless of consumers’ economic status. Participants believe that those with dual diagnosis can improve over time. Therefore, it is crucial to provide these individuals with high-quality services to aid in their recovery:

When they [consumers with dual diagnosis] get discharged, and then, we see that, they are happy and then they have got some independence, then how they move on to their life. (Felicity)

I have seen people improve over time, it might be the first few times of detox, but eventually they do get something from it and make changes to their lifestyle. (Crystal)

5.1.3. Listening to the whole story

This subtheme describes participants’ direct interaction with consumers with dual diagnosis. Participants used an open communication strategy to obtain as much information as possible when interacting with these consumers:

It is our responsibility to personally engage with the person [consumer with dual diagnosis] and help them feel comfortable and build a trusting relationship, so, they tell us as much information as possible. (Henry)

I have met different people [consumers with dual diagnosis]. The problem is, when we look at substances, we think it is their choice to use substances, but sometimes it is not. I am willing to listen to the whole story. I try and say, ‘Look, we have an issue up here’. Until this is resolved, they will always go back to alcohol or to cannabis and sort of things, or whatever issues they are having. (Isabella)

Their [consumers with dual diagnosis] behavior is erratic until we get them settled down with their medication regime. This is the chance to talk to somebody about their drug usage and how it impacts their mental health. Just explanation and communication are the best way to go. (Crystal)

5.2. Combating negativity in others

This theme describes participants’ views on what they perceive to be the negative attitude of some nurses toward consumers with dual diagnosis. Participants claimed that nurses need to be more helpful, and some are not looking at the whole picture of consumers’ illness. It is possible that nurses do not see illness as a result of the consumer’s psychosocial environment. This theme had two subthemes: fear and frustration, and stigmatized language.

5.2.1. Fear and frustration

Participants expressed dissatisfaction with managing consumers who have a dual diagnosis. They were concerned that managing such consumers could prove difficult, especially if they were under the influence of drugs or alcohol during their first referral:

There is a good element of fear, the good element of frustration is there. We can see there is a lack of empathy. I cannot say everyone [nurses] is like that, but some of them are like that. (Emma)

When consumers are angry or upset, nurses take that on board personally, straight away, instead of asking the consumers why they are angry and disappointed. (Nolan)

Nurses take it a little bit personally if somebody [consumers with dual diagnosis] has a slip, most of the time, they [nurse] are little bit avoidant of wanting to deal with the issues of the drug and alcohol. There is a little bit of avoidance. (Tiana)

I have come across some of my fellow nurses coming and telling me, ‘Could you avoid allocating this particular client for me today?’ That particular nurse would be afraid to engage with those kinds of clients. (Nora)

5.2.2. Stigmatized language

This subtheme describes nurses’ judgmental attitudes toward consumers with dual diagnosis. During handovers, nurses may use confrontational, belittling, and disparaging language toward these consumers:

If they [consumers with dual diagnosis] ask for medication, they [nurses] talk about drug-seeking behavior. You can still hear people saying, ‘Oh, he is just another drug seeker!’ (Henry)

Especially at the beginning of the shift allocation, some staff says, ‘I do not want to look after that patient’, because many of these dual diagnosis patients can be challenging. The staff politely refuse to look after them. (Jordan)

It is quite difficult working with other people [nurses] who are stigmatizing and punishing toward a client [consumers with dual diagnosis]. (Nolan)

It is another time, another druggie. Why can the police not just lock them up? (Isabella)

You know, sort of saying, ‘Oh, this is the pure drug and alcohol, they [consumers with dual diagnosis] are not mental health’. (Crystal)

One of my colleagues does not have a good attitude toward consumers [consumers with dual diagnosis], who [nurse] would call ‘drug users’. That particular nurse would lose interest or refuse to even engage with the client. If at all that nurse engages, would have that kind of attitude toward client. Interaction will be negative all the time negative. (Nora)

5.3. Working to improve outcomes

This theme describes the challenges of treating consumers with dual diagnosis. Providing quality mental health services is a crucial aspect of healthcare, and this theme underscores the need for continuous improvement in this area. This theme also highlights the importance of addressing mental health nurses’ educational needs. This is to equip them with the skills and knowledge required to deliver adequate and appropriate services for consumers with dual diagnosis. This theme had three subthemes: difficult to treat, limited services, and dual diagnosis training needs.

5.3.1. Difficult to treat

This subtheme describes participants’ opinions about consumers with dual diagnosis’ complexities and difficulties. According to participants, consumers who are referred to mental health services with drug and alcohol issues face significant challenges:

One of the big grey areas will be when there is any violence involved, it can be tricky. (Christopher)

So, in my experience, working with dual diagnosis, [I] find that very complicated. To be honest with you, it is difficult. (Isabella)

They [consumers with dual diagnosis] use [illicit drugs] as self-medicating, and of course, that goes oppositely. A lot of people who have diagnosed mental illnesses also use drugs and alcohol as a preference to using antipsychotic medications, which can exacerbate the whole situation. (Crystal)

5.3.2. Limited services

Combined with consumer complexities, this subtheme describes the difficulties staff and consumers face. According to participants, more public services should draw from other specialties:

The public service is heavily underfunded and quite often restrictive with their criteria, making it quite hard for people to access their services. People want to look at rehab, especially residential rehab. There are limited places, and COVID-19 has further limited that. (Austin)

The mental health service often focuses on the psychotic symptoms, keeping people [consumers with dual diagnosis] out of the hospital, the medications, some therapy. (Benson)

I have noticed when we [hospital] discharge them [consumers with dual diagnosis] from our facility, that is when they relapse, maybe because they do not get enough support in the community. (Lily)

Look, they [mental health service] are accessible, but the problem with these services is that they are set up more for middle-class sort of people as well as via appointments. (Nolan)

5.3.3. Dual diagnosis training needs

This subtheme describes dual diagnosis training needs for mental health nurses. According to participants, nurses working with consumers with dual diagnosis need encouragement and training in recovery-focused language. Participants indicated that nurses’ confidence could be improved through in-service training; however, participants reported that no consistent education packages were delivered to upskill nurses across various mental health settings:

There is one online package through [mental health service], we do it online once, you know, and that is it! You do not have to do it again through your whole career. (Tiana)

The nurse education team deals particularly with the inpatient unit, the graduate nurses and upskilling them. Once somebody transitions into the community, they [nurses] have to get the skills on the job. Their capacity to learn how to navigate the system and learn what is out there is dependent on the expertise of their colleagues. (Georgia)

I think the other one is learning from the people who have had some lived experience, whether through the work we do or having people with experience come in and teach us. (Henry)

6. Discussion

This qualitative study explored mental health nurses’ attitudes toward consumers with dual diagnosis. Three major themes with a total of eight sub-themes were identified.

The study’s identified themes indicated the importance of nurses feeling satisfied and connected at work, combating negativity in others, and working toward improving the outcomes of the work environment.

The findings show mental health nurses are satisfied and enjoy working with consumers with dual diagnosis. Participants were knowledgeable about caring for consumers with dual diagnosis. Happell et al. (Citation2002) reported that nurses are knowledgeable about alcohol and other drug use, as well as possess adequate problem-solving skills. Previous studies have also reported that nurses’ job satisfaction is related to their experience, knowledge, and skills (Takano et al., Citation2015).

The current study found mental health nurses’ lack of enthusiasm and harmful attitudes toward consumers with dual diagnosis. Researchers have reported that clinicians have a negative attitude toward consumers, treatment options, and society at large (Carey et al., Citation2000; Deans & Soar, Citation2005; Foster & Onyeukwu, Citation2003; Gilchrist et al., Citation2011; Ralley et al., Citation2009). It is worth noting that mental health nurses reported witnessing fear, frustration, and stigma among their colleagues. In addition, participants reported many difficulties and complexities when caring for consumers with dual diagnosis, including frustration, fear, and difficulties coping. Previous studies found similar results (Houghton et al., Citation2021; Zarea et al., Citation2013).

Participants stated that derogatory language is a culture ingrained in their profession; thus, they emphasized that mental health nurses must recognize consumers’ needs and use effective communication strategies when treating consumers. Participants reported that the negative attitudes of nurses can contribute to feelings of helplessness among consumers. To achieve a therapeutic relationship with consumers, mental health nurses must maintain an open dialogue with them. Other studies have reported that staff members’ opposing attitudes may be related to their struggles with developing a therapeutic relationship with consumers (Petersén et al., Citation2021). This study also identified areas by which to improve outcomes in caring for consumers with dual diagnosis. Participants acknowledged that consumers with dual diagnosis can be challenging to treat, and treatment pathways can sometimes be complex. Cleary et al. (Citation2009) reported that consumers with dual diagnosis are more challenging to treat than consumers with one mental illness or substance abuse issue. Brekke et al. (Citation2018) and Cilia Vincenti et al. (Citation2022) reported similar issues. It is necessary to develop effective strategies to manage issues that arise during consumer communication.

According to participants in this study, nursing confidence and attitude are improved by education and practical experience on the ward, as well as working with senior nurses. Previous studies have reported that regular training programs can address stigmatized attitudes, fears, and frustrations (Van Boekel et al., Citation2014) and reinforce staff confidence in providing superior consumer care (Horner et al., Citation2019). Regular education can also change attitudes over time (Bielenberg et al., Citation2021; Wright et al., Citation2022). It is beneficial to educate clinicians about drugs and alcohol issues (Munro et al., Citation2007; Pinderup, Citation2018). However, Barry et al. (Citation2002) recommend that training include a discussion of attitudes and beliefs regarding drug use and mental health problems. Taking training increases clinicians’ motivation, self-esteem, and job satisfaction because they feel more appropriate, legitimate, and supported (Pinderup, Citation2017). The current study indicates that dual diagnosis training remains necessary. Moore (Citation2013) suggests intensive training programs as a means of achieving this.

Nurses’ attitudes are further guided by several factors, including their age, work experience with consumers with dual diagnosis, and work settings (Chang & Yang, Citation2013). In the present study, all participants had extensive work experience (minimum of 10 years) and high job satisfaction and were highly motivated at work. It is likely that the participants with more work experience were more satisfied with their job and motivated since they had more opportunities to interact with consumers with dual diagnosis and provide care to them. According to Kluit et al. (Citation2013), role support, consistent work experience, further training, and open communication all contribute to developing a positive attitude and staff competence. Researchers reported that nurses who received training had more positive attitudes toward people who use illicit drugs regardless of their clinical experience or work setting (Howard & Holmshaw, Citation2010).

The study also found that there are hindrances to service provision that need to be addressed. Nurses’ attitudes may be affected by their lack of experience with successful interventions and recovery processes. More facilities and services are needed to meet the needs of consumers with dual diagnosis so that they can be served more effectively (Kavanagh et al., Citation2000). Providing more opportunities for consumer interaction and care may help mental health nurses develop a more positive attitude toward consumers with dual diagnosis.

7. Study limitations

This study was limited to an Australian context, which may affect the generalizability of the results. It is possible that snowball sampling could have led to sample bias and resulted in a population that represents smaller networks rather than the larger group. However, caring for consumers with dual diagnosis is a global challenge, and the results may apply to international healthcare settings.

8. Conclusion

This study explored attitudes among mental health nurses in caring for consumers with dual diagnosis. The findings suggest that mental health nurses are knowledgeable, motivated, satisfied, role-supported, and possess a variety of self-esteems specific to their roles toward consumers with dual diagnosis. It is however difficult to improve consumer care quality due to stigmatized language, fear and frustration among mental health nurses, lack of consistent dual diagnosis training packages, and limited services for consumers with dual diagnosis. In the view of the TPB, a person’s attitude, subjective norms, and perception of control determine whether or not they will engage in a particular behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1975). illustrates mental health nurses’ demotivational factors and perceived conversational partners. It may be beneficial to address these areas in order to build a positive attitude, which is essential to the success of treatment. It may be possible to contribute to a healthier attitude among nurses by addressing fears and frustrations through consistent education and training with experienced clinicians, consumers, carers, and peer support workers. Treatment outcomes may be improved as a result.

Relevance to clinical practice

The results can be used by teachers, clinicians, and administrators when designing, developing, and delivering training packages for mental health nurses in caring for consumers with dual diagnosis.

Mental health nurses need to be trained in dual diagnosis to ensure they can adequately assess and provide efficient care to consumers with dual diagnosis.

Mental health nurses should be given opportunity to work in multiple mental health settings so that they can familiarize themselves with the needs of these consumers with dual diagnosis.

Mental health nurses should also be provided with access to resources, such as shared learning opportunities, to help them gain a better understanding of consumer complexities.

Mental health nurses should be equipped with access to ongoing professional development opportunities to remain up-to-informed with the modern advances in dual diagnosis care.

Educational programs are needed to address stigmatized language and staff fear and frustration when providing care to consumers with dual diagnosis.

Further interventional research is needed on a larger sample of mental health nurses to assess their attitudes in caring for consumers with dual diagnosis.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Federation University Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval number: A19-026).

Author contributions

All authors listed meet the authorship criteria in keeping with the latest guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, and all the authors agree with the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants for participating in the research and sharing their experiences despite the difficulties associated with COVID-19.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice-Hall.

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (2005). The influence of attitudes on behavior. In D. Albarracín, B. T. Johnson, & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), The handbook of attitudes (pp. 173–221). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2018). Australia’s Health 2018 (Australia’s Health Series Publication No. 16). https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/36cb0f35-1d96-47bf-84f9-1eb8583ad7de/aihwaus-221-chapter-4-7.pdf.aspx

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2022). Mental health: prevalence and impact. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mental-health-services/mental-health

- Barry, K. R., Tudway, J. A., & Blissett, J. (2002). Staff drug knowledge and attitudes towards drug use among the mentally ill within a medium secure psychiatric hospital. Journal of Substance Use, 7(1), 50–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659890110110365

- Bielenberg, J., Swisher, G., Lembke, A., & Haug, N. A. (2021). A systematic review of stigma interventions for providers who treat patients with substance use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 131, 108486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108486

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brekke, E., Lien, L., Nysveen, K., & Biong, S. (2018). Dilemmas in recovery-oriented practice to support people with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders: A qualitative study of staff experiences in Norway. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 12(1), 30–30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-018-0211-5

- Carey, K. B., Purnine, D. M., Maisto, S. A., Carey, M. P., & Simons, J. S. (2000). Treating substance abuse in the context of severe and persistent mental illness: Clinicians’ perspectives. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 19(2), 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-5472(00)00094-5

- Chang, Y.-P., & Yang, M.-S. (2013). Nurses’ attitudes toward clients with substance use problems. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 49(2), 94–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12000

- Chicoine, G., Côté, J., Pepin, J., Dyachenko, A., Fontaine, G., & Jutras-Aswad, D. (2023). Improving the self-efficacy, knowledge, and attitude of nurses regarding concurrent disorder care: Results from a prospective cohort study of an interprofessional, videoconference-based programme using the ECHO model. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 32(1), 290–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.13082

- Cilia Vincenti, S., Grech, P., & Scerri, J. (2022). Psychiatric hospital nurses’ attitudes towards trauma-informed care. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 29(1), 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12747

- Cleary, M., Hunt, G. E., Matheson, S., & Walter, G. (2009). Views of Australian mental health stakeholders on clients’ problematic drug and alcohol use. Drug and Alcohol Review, 28(2), 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3362.2008.00041.x

- De Ruysscher, C., Vanheule, S., & Vandevelde, S. (2019). ‘A place to be (me)’: A qualitative study on an alternative approach to treatment for persons with dual diagnosis. Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy, 26(1), 50–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2017.1375461

- de Waal, M. M., Dekker, J. J. M., Kikkert, M. J., Christ, C., Chmielewska, J., Staats, M. W. M., van den Brink, W., & Goudriaan, A. E. (2019). Self-wise, Otherwise, Streetwise (SOS) training, an intervention to prevent victimization in dual-diagnosis patients: Results from a randomized clinical trial. Addiction, 114(4), 730–740. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14500

- Deans, C., & Soar, R. (2005). Caring for clients with dual diagnosis in rural communities in Australia: The experience of mental health professionals. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 12(3), 268–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2005.00830.x

- Estreet, J. K., & Privott, C. (2021). Understanding therapists’ perceptions of co-occurring substance use disorders using the model of human occupation screening tool. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 9(2), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.15453/2168-6408.1773

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

- Farley-Toombs, C. (2012). The stigma of a psychiatric diagnosis: Prevalence, implications and nursing interventions in clinical care settings. Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America, 24(1), 149–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2012.01.009

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behaviour: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley.

- Foster, J. H., & Onyeukwu, C. (2003). The attitudes of forensic nurses to substance using service users. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 10(5), 578–584. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2850.2003.00663.x

- Garrod, E., Jenkins, E., Currie, L. M., McGuinness, L., & Bonnie, K. (2020). Leveraging nurses to improve care for patients with concurrent disorders in inpatient mental health settings: A scoping review. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 16(3), 357–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/15504263.2020.1752963

- Gilchrist, G., Moskalewicz, J., Slezakova, S., Okruhlica, L., Torrens, M., Vajd, R., & Baldacchino, A. (2011). Staff regard towards working with substance users: A European multi-centre study. Addiction, 106(6), 1114–1125. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03407.x

- Graham, H. L. (2004). Implementing integrated treatment for co-existing substance use and severe mental health problems in assertive outreach teams: Training issues. Drug and Alcohol Review, 23(4), 463–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/09595230412331324581

- Hamdan-Mansour, A. M., Al-Sagarat, A. Y., AL-Sarayreh, F., Nawafleh, H., & Arabiat, D. H. (2018). Prevalence and correlates of substance use among psychiatric inpatients. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 54(2), 149–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12214

- Happell, B., Carta, B., & Pinikahana, J. (2002). Nurses’ knowledge, attitudes and beliefs regarding substance use: A questionnaire survey. Nursing & Health Sciences, 4(4), 193–200. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1442-2018.2002.00126.x

- Horner, G., Daddona, J., Burke, D. J., Cullinane, J., Skeer, M., & Wurcel, A. G. (2019). “You’re kind of at war with yourself as a nurse”: Perspectives of inpatient nurses on treating people who present with a comorbid opioid use disorder. PLOS One, 14(10), e0224335. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224335

- Houghton, B., Bailey, A., Kouimtsidis, C., Duka, T., & Notley, C. (2021). Perspectives of drug treatment and mental health professionals towards treatment provision for substance use disorders with coexisting mental health problems in England. Drug Science, Policy and Law, 7, 205032452110553. https://doi.org/10.1177/20503245211055382

- Howard, V., & Holmshaw, J. (2010). Inpatient staff perceptions in providing care to individuals with co-occurring mental health problems and illicit substance use. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 17(10), 862–872. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01620.x

- Iheanacho, T., Bommersbach, T., Fuehrlein, B., Arnaout, B., & Dike, C. (2020). Brief training on medication-assisted treatment improves community mental health clinicians’ confidence and readiness to address substance use disorders. Community Mental Health Journal, 56(8), 1429–1435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00586-8

- Kavanagh, D. J., Greenaway, L., Jenner, L., Saunders, J. B., White, A., Sorban, J., & Hamilton, G. (2000). Contrasting views and experiences of health professionals on the management of comorbid substance misuse and mental disorders. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 34(2), 279–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/j.1440-1614.2000.00711.x

- Kluit, M. J., Goossens, P. J. J., & Leeuw, J. R. J. (2013). Attitude disentangled: A cross-sectional study into the factors underlying attitudes of nurses in Dutch rehabilitation centers toward patients with comorbid mental illness. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 34(2), 124–132. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2012.733906

- Livingston, J. D., Milne, T., Fang, M. L., & Amari, E. (2012). The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: A systematic review. Addiction, 107(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03601.x

- Lopes, J., & Freitas, R. (2022). Dual diagnosis, double trouble. European Psychiatry, 65(S1), S471. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2022.1197

- Lopez, V., & Whitehead, D. (2013). Sampling data and data collection in qualitative research. Nursing & Midwifery Research, 123, 140.

- Lucksted, A., & Drapalski, A. L. (2015). Self-stigma regarding mental illness: Definition, impact, and relationship to societal stigma. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 38(2), 99–102. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000152

- Maio, G. R., & Haddock, G. (2012). Psychology of attitudes. SAGE.

- Moore, J. (2013). Dual diagnosis: Training needs and attitudes of nursing staff. Mental Health Practice, 16(6), 27–31. https://doi.org/10.7748/mhp2013.03.16.6.27.e801

- Munro, A., Watson, H. E., & Mcfadyen, A. (2007). Assessing the impact of training on mental health nurses’ therapeutic attitudes and knowledge about co-morbidity: A randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 44(8), 1430–1438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.07.024

- Ortega, L. B., & Ventura, C. A. (2013). I am alone: The experience of nurses delivering care to alcohol and drug user. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP, 47(6), 1381–1388. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0080-623420130000600019

- Peters, M. D., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

- Peters, R. H., Young, M. S., Rojas, E. C., & Gorey, C. M. (2017). Evidence-based treatment and supervision practices for co-occurring mental and substance use disorders in the criminal justice system. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 43(4), 475–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/00952990.2017.1303838

- Petersén, E., Thurang, A., & Berman, A. H. (2021). Staff experiences of encountering and treating outpatients with substance use disorder in the psychiatric context: A qualitative study. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 16(1), 29–29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-021-00235-9

- Phillips, P. A. (2007). Dual diagnosis: An exploratory qualitative study of staff perceptions of substance misuse among the mentally ill in northern India. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 28(12), 1309–1322. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840701686468

- Pinderup, P. (2017). Training changes professionals’ attitudes towards dual diagnosis. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 15(1), 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-016-9649-3

- Pinderup, P. (2018). Improving the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of mental health professionals regarding dual diagnosis treatment: A mixed methods study of an intervention. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 39(4), 292–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2017.1398791

- Pinikahana, J., Happell, B., & Carta, B. (2002). Mental health professionals’ attitudes to drugs and substance abuse. Nursing & Health Sciences, 4(3), 57–62. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1442-2018.2002.00104.x

- Priebe, Å., Wiklund Gustin, L., & Fredriksson, L. (2018). A sanctuary of safety: A study of how patients with dual diagnosis experience caring conversations. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(2), 856–865. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12374

- QSR International Pty Ltd (2018). NVivo (version 12). https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- Ralley, C., Allott, R., Hare, D. J., & Wittkowski, A. (2009). The use of the repertory grid technique to examine staff beliefs about clients with dual diagnosis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 16(2), 148–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.606

- Richmond, I., & Foster, J. (2003). Negative attitudes towards people with co-morbid mental health and substance misuse problems: An investigation of mental health professionals. Journal of Mental Health, 12(4), 393–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/0963823031000153439

- Russell, R., Ojeda, M. M., & Ames, B. (2017). Increasing RN perceived competency with substance use disorder patients. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 48(4), 175–183. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20170321-08

- Smyth, D., Hutchinson, M., & Searby, A. (2019). Nursing knowledge of alcohol and other drugs (AOD) in a regional health district: An exploratory study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 40(12), 1034–1039. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2019.1630531

- Takano, A., Kawakami, N., Miyamoto, Y., & Matsumoto, T. (2015). A study of therapeutic attitudes towards working with drug abusers: Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the drug and drug problems perception questionnaire. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 29(5), 302–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2015.05.002

- Toftdahl, N. G., Nordentoft, M., & Hjorthøj, C. (2016). Prevalence of substance use disorders in psychiatric patients: A nationwide Danish population-based study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(1), 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1104-4

- Tong, A., Flemming, K., McInnes, E., Oliver, S., & Craig, J. (2012). Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 12(1), 181–181. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-12-181

- Van Boekel, L. C., Brouwers, E. P., van Weeghel, J., & Garretsen, H. F. (2014). Healthcare professionals’ regard towards working with patients with substance use disorders: Comparison of primary care, general psychiatry and specialist addiction services. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 134, 92–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.09.012

- Wheeler, A., Crozier, M., Robinson, G., Pawlow, N., & Mihala, G. (2014). Assessing and responding to hazardous and risky alcohol and other drug use: The practice, knowledge and attitudes of staff working in mental health services. Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy, 21(3), 234–243. https://doi.org/10.3109/09687637.2013.864255

- World Health Organization (2019). Lexicon of alcohol and drug terms. 1994. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/39461/9241544686_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- World Health Organization (2020). Substantial investment needed to avert mental health crisis. WHO. https://www.who.int/news/item/14-05-2020-substantial-investment-needed-to-avert-mental-health-crisis

- World Health Organization (2022). Mental health. 2022. 10 Facts on mental health (Who.int). Author.

- World Health Statistics (2022). 2022: Monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. World Health Organization. 9789240051140-eng.pdf (who.int)

- Worley, J. (2019). Effective strategies for working with patients with substance use disorders. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 57(9), 11–15. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20190815-02

- Wright, M. E., Parker, V., Demosthenes, L. D., Stevens, M. L., & Litwin, A. H. (2022). Changing nurse practitioner students’ perceptions regarding substance use disorder. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 18(1), 81–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2021.08.014

- Zarea, K., Nikbakht-Nasrabadi, A., Abbaszadeh, A., & Mohammadpour, A. (2013). Psychiatric nursing as ‘different’ care: Experience of Iranian mental health nurses in inpatient psychiatric wards. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 20(2), 124–133. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2012.01891.x