Abstract

This review explores the transformative impact of sensory modulation interventions in acute inpatient mental health care setting utilising meta-ethnography. The methodology by Noblit & Hare guided the approach to creating the review. Searches of articles published within the previous 10 years were conducted in Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), MEDLINE, and PsycINFO. Searches aimed to identify rich qualitative data on the area of sensory modulation interventions and acute inpatient mental health care. Seven articles were selected for inclusion and a reciprocal translation synthesis was undertaken. Sensory modulation interventions emerged as a key alternative to traditional inpatient practices, including seclusion and restraint and the use of PRN psychotropic medication. It introduces a new dimension within care strategies that emphasise individual preferences and care plans that empower individuals. Sensory modulation interventions serve as an effective means to de-escalation that promotes shared responsibility between staff and individuals in care. The review highlights this practice as a departure from coercive practices and biomedical interventions, promoting meaningful therapeutic engagement. Our findings show that sensory modulation interventions have the potential to create a culture shift in acute inpatient mental health settings towards person-centred, recovery-orientated, trauma-informed clinical practice.

Introduction

Sensory modulation interventions are therapeutic approaches that utilise the person’s sensory inputs of hearing, smell, taste, sight and touch to promote emotional wellbeing (Wright et al., Citation2023). These sensory experiences are often impacted during periods of distress, and this can be expressed as behavioural disturbance, which can be managed using psychotropic medication and/or seclusion in acute inpatient mental health settings (Lloyd et al., Citation2014). Sensory modulation interventions have been identified as an effective sensory-based treatment for people who are admitted to acute inpatient mental health units and are distressed, agitated, anxious, or potentially aggressive (Hedlund Lindberg et al. Citation2019; Machingura et al., Citation2018). Sensory modulation interventions utilise sensory equipment, environmental modifications and sensorimotor activities to engage the senses (Lipskaya-Velikovsky et al. Citation2015). Items used in interventions can include, but are not limited to, beanbags, lighting systems, herbal teas, bubble tubes, aromatherapy diffusers, music-players and weighted materials, such as blankets (Scanlan & Novak, Citation2015; Wright et al., Citation2023). Interventions can be contained in specific sensory rooms, purposefully designed for sensory modulation, or flexibly provided to people in the form of sensory kits and sensory trolleys (Scanlan & Novak, Citation2015). Sensory modulation interventions have been shown to moderate arousal, allowing people to develop an awareness of their affective state, as well as equipping the person with a strategy and tools for emotional regulation (Sutton et al., Citation2013). These tools and strategies can support people to adapt to the challenges faced by them in their everyday daily lives (Barbic et al., Citation2019). Most of the literature on sensory modulation interventions comes from the area of paediatric occupational therapy, primarily focused on developmental disorders and autism spectrum disorder (Brown et al., Citation2018). However, the approach is used across the lifespan, for a myriad of health and wellbeing issues, by a wide variety of health-care providers.

Sensory modulation interventions are an evolving practice in mental health settings, with an increase in research on the area undertaken over the last decade. It has been identified that it may support trauma-informed, recovery-orientated care (Scanlan & Novak, Citation2015). It has also been reported to improve the relationship between service users and healthcare providers, increasing collaboration in care (Björkdahl et al., Citation2016; Gardner, Citation2016). This collaboration is achieved through engagement with service users in practices such sensory screening and assessment, guided exploration of sensory tools or equipment, collaborative development of personalised sensory plans and sensory kits, environmental modification of the person’s environment, and education (Andersen et al., Citation2017). They can offer a low-cost intervention that has the potential to improve a person’s quality of life (Bobier et al., Citation2015), without the negative side effects associated with many biomedical interventions (Wand et al., Citation2024).

Through an ability to reduce aroused physiological and emotional states, sensory modulation interventions have been identified as lessening coercive responses in acute inpatient mental health units (Cummings et al., Citation2010). They have been linked to reductions in the incidents of seclusion and restraint (Cummings et al., Citation2010; Sutton & Nicholson, Citation2011). These coercive practices can have serious adverse effects on people receiving mental health care, and there is a movement towards their reduction, and where possible, eradication from practice in many countries (Havilla et al., Citation2023). Sensory modulation interventions have been identified as a key area for practice development to support these reforms (Quinn et al., Citation2024). However, Alhaj and Trist (Citation2023) note that findings from quantitative research in this area are conflicting, and there are several limitations in the evidence available to clearly establish whether sensory modulation interventions do reduce coercive practice.

Within the context of the expanding use of sensory modulation interventions and research highlighting their benefits, the authors have undertaken a synthesis of previous qualitative research findings to develop a deeper understanding of the social context of sensory modulation interventions in the acute inpatient mental health environment. The aim of the review is to explore any impacts that sensory modulation interventions may have on clinical practice that are seen across these settings.

Methods

Design

A review protocol was registered with the Open Science Framework (OSF.IO/X5CR6). This review utilised Noblit and Hare (Citation1988) inductive interpretative method of knowledge synthesis, meta-ethnography. This well-established review method interprets qualitative studies to reveal the analogies between them (Noblit & Hare, Citation1988). The seven steps of the method are: getting started (step 1), deciding what is relevant to the initial interest (step 2), reading (and rereading) studies to discover the main concepts (step 3), determining how the studies are related (step 4), translating the studies into one another (step 5), synthesising translations (step 6), and communicating the synthesis (step 7) (Noblit & Hare, Citation1988). The eMERGe reporting guidance for meta-ethnography guides the reporting of the review (France et al., Citation2019). Step 1 is detailed in the aims and rationale for the review.

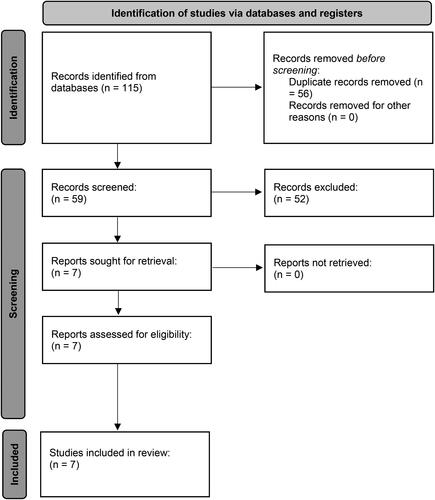

For step 2, the reviewers sought qualitive data that could derive an understanding of the impact of sensory modulation interventions within acute inpatient mental health units, published in English over the previous ten years (2013-2023). We excluded studies that did not have sensory modulation interventions as their primary focus or contain qualitative findings from this clinical setting. We searched three bibliographic databases which contain mental health care-related research: MEDLINE, PsycINFO and CINAHL. Titles and abstract were purposively searched for the words: sensory modulation or sensory approach or sensory-based intervention or sensory intervention or sensory room or sensory-based intervention and mental health or psychiatric. LM and SC screened the titles and abstracts of the search findings, and then the full text of potential studies. The search identified 7 studies that were sufficiently similar in their findings to allow for a reciprocal translation synthesis (Sattar et al., Citation2021). These included qualitative or mixed-methods studies with rich qualitative data. Reciprocal translation focuses in translating the findings of one study into another, in an iterative way, and can develop interpretative metaphors that could best represent the connections across the studies, in concordance with the research aims (Noblit & Hare, Citation1988; Sattar et al., Citation2021). A flow diagram of the search is presented in and an overview of the included studies is provided in (organised chronologically by year of data collection).

Figure 1. The PRISMA 2020 flow diagram showing the study selection process (Page et al., Citation2021).

Table 1. Descriptive details of sensory modulation intervention studies and NICE quality scores.

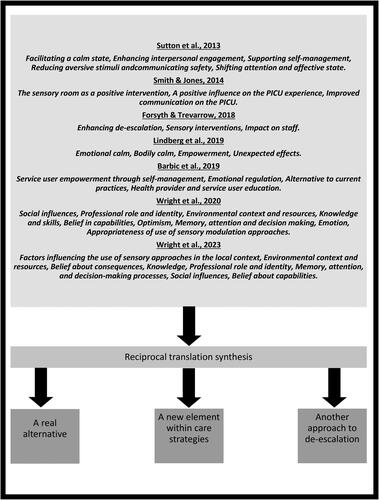

Following step 3, the included studies were read repeatedly to understand the key metaphors in their texts (LM). Data were extracted from the full included studies utilising NVivio 12 plus. This included staff and consumer quotes as first order concepts and the second order concepts of the author’s own interpretations. The reader’s observations were documented, and these led to the development of the review’s third order constructs, the interpretation of this meta-ethnography (SH, LM, JP, PB). A conceptual map of this process covering step 4 of the meta-ethnography is presented in .

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Citation2012) critical appraisal guidelines for qualitative research were used to evaluate the methodological rigour of the included studies. One of three assessments is made to indicate whether all (++), some (+), or very (-) of the quality appraisal criteria were fulfilled. The results of this critical appraisal are included in .

Findings

The review identified seven studies that had rich qualitive data on sensory modulation interventions in acute inpatient mental health settings (see ). Within these studies, we identified three interpretative metaphors that connected the studies and were relevant to its aims and rationale. shows how these third orders constructs link to the second order concepts in the included studies. The metaphors identified were:

A real alternative: Sensory modulation interventions equipped staff with a key replacement practice for PRN medication administration and seclusion and restraint.

A new element within care strategies: Sensory modulation interventions provided staff with an effective extra dimension within their care strategies.

Another approach to de-escalation: Sensory modulation interventions were used proactively by staff to settling escalating affective states.

A real alternative

The meta-ethnography highlighted that sensory modulation interventions could offer a real alternative to traditional practices in the acute inpatient mental health setting. While requiring an increased effort, staff believed that they had the potential to replace PRN medications as first-line response in their practice to some situations in these settings. Rather than administering psychotropic medications as a temporary fix, staff highlighted that utilising sensory modulation interventions could support people to develop new skills that could be used in the future to manage times when they felt overwhelmed. This practice connected positively with their conceptualisation of their therapeutic role, contrasting with beliefs about the limited efficacy of biomedical interventions.

“It did take longer than giving people medication, but it gave people a real strategy of how to help themselves next time. So instead of just sticking a plaster on it, on the problem, which is kind of what PRN does … you’re actually giving somebody a really concrete way of dealing with their problems” (Sutton et al., Citation2013, pp. 506).

“I think it teaches a kind of personal resilience in terms of dealing with what they’re actually feeling and not necessarily just using chemical means of doing so” (Barbic et al., Citation2019, pp. 8).

An enthusiastic endorsement of sensory modulation interventions by staff and their adoption as a preferred strategy underscored their transformative impact. The prospect of a decreased reliance on PRN medication was also seen as both an improvement in the care of the person and a positive change for clinical practice.

“the up-take and use of all the sensory approaches on our floor is great and nursing staff are so on board with it. Every handover, you’re… listening to them give the account of the night before and they always [say] – The patient utilised sensory approaches with good effects – so they’re using that as the first line rather than going straight to PRN” (Wright et al., Citation2020, pp. 613).

As sensory modulation interventions became embedded in practice, staff reported that there was a wider improvement in the milieu. This was perceived by staff to directly impact on both the use of biomedical intervention and the coercive practices of seclusion and restraint.

“it will actually improve the wards a lot, so you wouldn’t have to use the PRN and use seclusion so much” (Wright et al., Citation2020, pp. 612).

“the [sensory] room is really good for… reducing rates of seclusion and restraint because that often is the first line…” (Wright et al., Citation2020, pp. 614).

A new element within care strategies

The studies showed sensory modulation interventions brought a new aspect to inpatient care. Staff used it to create an extra dimension within their care strategies that were viewed as a crucial element in supporting the well-being of service users. They could bring a focus on it into the beginnings of care within the assessment processes. This included staff having a specific focus on the individual’s preferences for sensory modulation intervention.

“…consideration of individual sensory preferences has become a key part of formulation and distress management planning during the assessment process” (Forsyth & Trevarrow, Citation2018, pp. 1695).

Building on assessment, the studies highlighted that sensory modulation interventions could then be utilised within the person’s care planning. These plans could be founded on an understanding of the person’s needs developed by the staff through focused interpersonal relationships, and their knowledge of the sensory interventions available on the units. Sensory modulation interventions were seen to be an effective element of inpatient care, that were judged by staff to be beneficial in managing distress in a personalised way. They allowed for interventions that could be structured in collaboration with the person receiving care, in a way that was meaningful to them. This marked a change to the limitations of past approaches to inpatient care, that were obvious to staff.

“They suggested personal safety plans could be used with consumers to identify individualised sensory strategies, and that individualised sensory kits could be developed collaboratively with consumers.” (Wright et al., Citation2023, pp. 7).

“…it’s about knowing your patients, if your key nurse was around they had built up most rapport with the patient so we would look at strategies… we look at care planning for what those strategies would be but those would be limited before we had the chillout room.” (Forsyth & Trevarrow, Citation2018, pp. 1692).

As care strategies developed, staff identified a belief that sensory modulation interventions could empower and move the nexus of control of inpatient care to the person receiving care. This shift occurred as care plans evolved into self-management, in an approach to care that increasingly emphasised the importance of the person’s autonomy. Staff encouraged people to use it as an early intervention for their challenging experiences and they increasingly appreciated its impact on people taking control of their experiences of mental ill-health.

“The most prevalent theme amongst service users and health provider interviews was utilising [sensory modulation interventions] to empower patients and enable self-management strategies to enhance care experiences… [sensory modulation interventions were] identified as a way to give dignity and control back to people receiving services on the unit.” (Barbic et al., Citation2019, pp. 6-7).

“Several participants specifically commented on the positive attitudes of staff towards the sensory room and the orientation that it provided for patient autonomy.” (Hedlund Lindberg et al., Citation2019, pp. 935).

Another approach to de-escalation

The studies identified that a key area in which sensory modulation interventions had shaped the adaption of practice was in de-escalation in acute inpatient mental health settings. Both staff and people receiving care described it as beneficial in settling escalating affective states, through the provision of spaces where people could re-establish a sense of calm and take time to self-regulate. Sensory modulation interventions also enabled a proactive approach to be taken by staff, that allowed for the effective management of potentially violent situations.

“So, when we notice the aggressiveness in the earlier stage, so we offer then – do you want an environment where you can calm down? And chill out? So that is when we use the sensory room, and it does work.” (Smith & Jones, Citation2014, pp.28).

By transforming the scope of de-escalation practice, it was found that sensory modulation interventions could nurture processes of shared responsibility between staff and people receiving inpatient care.

“By supporting service users to recognize their own sensory sensitivities and triggers and to develop their own strategies, sensory modulation broadened the focus of de-escalation practices and encouraged shared responsibility.” (Sutton et al., Citation2013, pp. 506).

This transformation was seen at times where tense situations were effectively diffused by staff without the need for in-depth verbal engagement, allowing people to relax, experience the sensory modulation intervention and ultimately de-escalate.

“Sometimes it might take the heat out a situation and words aren’t needed in a certain situation, to just sit down and just have these special lights on, sit in the (weighted) chair and listen to certain sounds rather than hearing someone telling you the same stuff, like over and over again”. (Forsyth & Trevarrow, Citation2018, pp. 1693).

A key driver of sensory modulation intervention’s ability to be used in de-escalation was that it created focused engagement time, where staff were near to people in the units. This allowed for activities that nurtured interpersonal engagement, which would otherwise have been difficult to achieve in bustling inpatient environments. In relaxed and safe environments, people receiving care shared their feelings with staff. While staff could work closely with people to foster more supportive, meaningful relationships.

“That rapport building as well … you’re not communicating verbally with them, but you’ve still built up a rapport … they trust you …. talking and building up communication and building up that rapport, it’s kind of just come instantly with that person.” (Sutton et al., Citation2013, pp. 505).

Discussion

While observing the social structure of psychiatric hospitals in the 1950s, Erving Goffman noted that staff found themselves having the contradictory expectations of being both coercive and caring to people in their charge, and that coercive approaches ultimately dominated caring interventions (Goffman, Citation1961). Over the last 70 years, there has been an evolution in the governmental requirements for inpatient mental health services, but contradictions remain for the staff working within them (Gabrielsson et al., Citation2020; Molloy et al., Citation2016). Similar to the psychiatric hospitals of the 1950s, the current use of coercive practices creates a paradoxical system of care (Havilla et al., Citation2023; Maker & McSherry, Citation2019). Their use to realise the current policy expectations of safety, both for the individual and those around them, create this paradox. In this system, seclusion and restraint are utilised within an environment that has requirements for therapeutic engagement, recovery-orientated care, and the minimisation of coercive practices (New South Wales Ministry of Health, Citation2017). Our review highlighted that by implementing sensory modulation interventions in these systems, staff had a practice toolkit that could help them break away from dominant coercive practices and move towards practices that were therapeutic. Sensory modulation interventions allow nurses to provide care that is holistic in focus and personalised in its approach, with the potential to enhance therapeutic engagement between the nurse and service user (Williamson & Ennals, Citation2020). This has clear importance in acute inpatient mental health settings which have been identified as being depersonalising environments, with low utilisation of effective therapeutic practices (Beckett et al., Citation2017; Phipps et al., Citation2019). Our findings highlight, sensory modulation interventions have the potential to broaden the interactions between service users and nurses, providing a clearer foundation to support personal recovery and with the potential to reduce the use of coercive practice. Therefore, sensory modulation interventions are in synergy with the contemporary service requirements for acute inpatient mental health settings.

The purpose of this meta-ethnography was to synthesise qualitative data from research studies focused on sensory modulation interventions within acute inpatient mental health settings. The aim was to explore any impacts that sensory modulation interventions had on clinical practice in these settings. Employing a reciprocal translation synthesis, the review identified articles that illuminated sensory modulation interventions as having shared impacts across a variety of study sites. Sensory modulation interventions offer an alternative to biomedical interventions and coercive practices, providing an extra dimension to acute care strategies and adding to staffs’ repertoire of de-escalation interventions. The last decade has seen increasing interest in sensory modulation interventions as a practice in mental health care, but there is still a relatively small body of knowledge to support evidence-based practice in this area (Hitch et al., Citation2020). Despite this limitation, the practice has been identified as a key approach to reduce the use of coercive practices, including at a policy level and within clinical guidelines (Brown et al., Citation2018; Hitch et al., Citation2020; Väkiparta et al., Citation2019; Wright et al., Citation2020). Quantitative research shows sensory modulation interventions have variable effectiveness in reducing the incidents of coercive practices. Scott (Citation2021) has identified three studies where quantitative data shows that sensory modulation interventions have reduced seclusion rates in adult inpatient populations (Andersen et al., Citation2017; Lloyd et al., Citation2014; Sivak, Citation2012) but notes that there are three studies that show no statistically significant change in seclusion rates after its introduction (Cummings et al., Citation2010; Novak et al., Citation2012; West et al., Citation2017). The importance of this review is that it shows there are positive effects to clinical practice in acute inpatient mental health care due to the introduction of sensory modulation interventions. From these, we can see that sensory modulation interventions have the potential to support the further development of person-centred, recovery-orientated, trauma-informed clinical practice in acute inpatient settings (Wright et al., Citation2020, Craswell et al., Citation2021). Sensory modulation interventions can empower service users and increase their autonomy within the acute inpatient mental health setting through the development of self-management strategies that can enhance their experience of personal recovery (Barbic et al., Citation2019). They also offer treatment alternatives to traditional treatment modalities in mental health care, a key component of recovery-orientated mental health services (Barbic et al., Citation2019). However, it should be noted that these are the findings of seven studies from five countries with well-resourced public health services. The review was carried out by authors with experience of clinical practice in inpatient mental health setting, which has the potential to shape our interpretation of the findings.

Despite advantages stemming from its introduction, reports indicate that sensory modulation interventions have been challenging to implement in inpatient settings (Hamilton et al., Citation2016; Wright et al., Citation2020). There is evidence that there are challenges successfully implementing sensory modulation interventions and sustaining their use (Hamilton et al., Citation2016; Wright et al., Citation2020, Citation2023). Although not consistently reported across the research reviewed, some identified issues could potentially challenge long-term implementation and effective practice change. These included issues related to role confusion about responsibility for the delivery of sensory modulation interventions between nurses and occupational therapists (Forsyth & Trevarrow, Citation2018; Wright et al., Citation2020, Citation2023) and a waning of enthusiasm for sensory modulation interventions post-implementation (Wright et al., Citation2020).

The challenges associated with the effective transfer of evidence into practice have been identified across a wide range of settings, including sensory modulation interventions (Blackburn et al., Citation2016; Burke & Hutchins, Citation2016), including sensory modulation interventions (Blackburn et al., Citation2016). Thornicroft et al. (Citation2016) have described a raft of structural and attitudinal problems that have stymied efforts at mental health practice development. Within the implementation literature, individual staff factors (their attitudes, skills, and motivation) play a significant role in determining the success of practice implementation initiatives (Mashiach Eizenberg Citation2011). Workshop and in-service training remain the primary approach for the transfer of training and the implementation of new practice, despite a lack of evidence for their effectiveness (Jackson-Blott et al., Citation2019; Walker & Baird, Citation2019). Coaching and mentoring provided in the workplace by clinicians who are skilled and experienced in sensory modulation interventions may enhance training transfer (Andersen et al., Citation2017; McSharry & O'Grady, Citation2021). While in-vivo training can enable the demonstration of new practice, and the provision of real-time feedback which can assist learning and development (Reid, Citation2017). For example, Azuela et al. (Citation2023) found that workplace champions and ongoing support from sensory modulation intervention practice consultants, supported sustained changes in staff attitudes and behaviours. While Blackburn et al. (Citation2016) identified a blended approach that included in-vivo training and support from workplace champions was successful in improving staffs’ understanding of sensory modulation interventions and their use in clinical practice.

At the organisational level, effective implementation of sensory modulation interventions can be enhanced by collaborative inter-professional teamwork, and continuous promotional efforts (Andersen et al., Citation2017). The reduction of coercive practice such as seclusion and restraint present a significant challenge to healthcare organisations requiring effective, multi-disciplinary teamwork and leadership (Havilla et al., Citation2023). The involvement of peer workers and advocates is essential in the implementation of sensory modulation interventions (Wright et al., Citation2020; Badouin et al., Citation2023). Other factors including the engagement of clinical leaders, clinical supervision, and stakeholder consultation have been shown to sustain implementation of sensory modulation interventions (Azuela et al., Citation2023).

Conclusion

This synthesis of research highlights that sensory modulation interventions can have a transformative impact on practice within acute inpatient mental health settings. The three interpretative metaphors: A real alternative; A new element within care strategies; and Another approach to de-escalation- illustrate the potential of sensory modulation interventions to offer alternatives to traditional inpatient care practices by providing an extra dimension to care strategies and additional tools for de-escalation. Sensory modulation interventions have the potential to empower people in managing their emotional well-being and its use signifies a cultural shift towards a more person-centred, therapeutic approach. This shift from biomedical interventions and coercive practices can support a departure from the tradition limitations and contradictions of inpatient care, promoting a more recovery-orientated, trauma-informed approach.

Author contributions

Substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Conceptualisation

LM, SC. Data extraction, LM, SC. Data analysis and interpretation: LM, PB, SC, JP. Data checking: LM, SC, PB. Draft writing: LM, SC, PB, JP, SH, DP. Review of final draft: All authors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alhaj, H. A., & Trist, A. (2023). The effects of sensory modulation on patient’s distress and use of restrictive interventions in adult inpatient psychiatric settings: A critical review. Advances in Biomedical and Health Sciences, 2(3), 105–111. https://doi.org/10.4103/abhs.abhs_52_22

- Andersen, C., Kolmos, A., Andersen, K., Sippel, V., & Stenager, E. (2017). Applying sensory modulation to mental health inpatient care to reduce seclusion and restraint: A case control study. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 71(7), 525–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2017.1346142

- Azuela, G., Sutton, D., & van Kessel, K. (2023). Sensory modulation implementation strategies within inpatient mental health services: An organisational case study. Mental Health Review Journal, 28(3), 242–256. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHRJ-06-2022-0035

- Badouin, J., Bechdolf, A., Bermpohl, F., Baumgardt, J., & Weinmann, S. (2023). Preventing, reducing, and attenuating restraint: A prospective controlled trial of the implementation of peer support in acute psychiatry. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1089484. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1089484

- Barbic, S. P., Chan, N., Rangi, A., Bradley, J., Pattison, R., Brockmeyer, K., Leznoff, S., Smolski, Y., Toor, G., Bray, B., Leon, A., Jenkins, M., & Mathias, S. (2019). Health provider and service-user experiences of sensory modulation rooms in an acute inpatient psychiatry setting. PloS One, 14(11), e0225238. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225238

- Beckett, P., Holmes, D., Phipps, M., Patton, D., & Molloy, L. (2017). Trauma-informed care and practice: Practice improvement strategies in an inpatient mental health ward. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 55(10), 34–38. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20170818-03

- Björkdahl, A., Perseius, K.-I., Samuelsson, M., & Lindberg, M. H. (2016). Sensory rooms in psychiatric inpatient care: Staff experiences. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 25(5), 472–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12205

- Blackburn, J., McKenna, B., Jackson, B., Hitch, D., Benitez, J., McLennan, C., & Furness, T. (2016). Educating mental health clinicians about sensory modulation to enhance clinical practice in a youth acute inpatient mental health unit: A feasibility study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 37(7), 517–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2016.1184361

- Bobier, C., Boon, T., Downward, M., Loomes, B., Mountford, H., & Swadi, H. (2015). Pilot investigation of the use and usefulness of a sensory modulation room in a child and adolescent psychiatric inpatient unit. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 31(4), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2015.1076367

- Brown, A., Tse, T., & Fortune, T. (2018). Defining sensory modulation: A review of the concept and a contemporary definition for application by occupational therapists. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 26(7), 515–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2018.1509370

- Burke, L. A., & Hutchins, H. M. (2016). Training transfer: An integrative literature review. Human Resource Development Review, 6(3), 263–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484307303035

- Craswell, G., Dieleman, C., & Ghanouni, P. (2021). An integrative review of sensory approaches in adult inpatient mental health: Implications for occupational therapy in prison-based mental health services. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 37(2), 130–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2020.1853654

- Cummings, K. S., Grandfield, S. A., & Coldwell, C. M. (2010). Caring with comfort rooms: Reducing seclusion and restraint use in psychiatric facilities. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 48(6), 26–30. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20100303-02

- Forsyth, A. S., & Trevarrow, R. (2018). Sensory strategies in adult mental health: A qualitative exploration of staff perspectives following the introduction of a sensory room on a male adult acute ward. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(6), 1689–1697. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12466

- France, E. F., Cunningham, M., Ring, N., Uny, I., Duncan, E. A. S., Jepson, R. G., Maxwell, M., Roberts, R. J., Turley, R. L., Booth, A., Britten, N., Flemming, K., Gallagher, I., Garside, R., Hannes, K., Lewin, S., Noblit, G. W., Pope, C., Thomas, J., … Noyes, J. (2019). Improving reporting of meta-ethnography: The eMERGe reporting guidance. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0600-0

- Gabrielsson, S., Tuvesson, H., Wiklund Gustin, L., & Jormfeldt, H. (2020). Positioning psychiatric and mental health nursing as a transformative force in health care. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 41(11), 976–984. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2020.1756009

- Gardner, J. (2016). Sensory modulation treatment on a psychiatric inpatient unit: Results of a pilot program. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 54(4), 44–51. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20160318-06

- Goffman, E. (1961). Asylums: Essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates. Anchor Books.

- Hamilton, B., Fletcher, J., Sands, N., Roper, C., & Elsom, S. (2016). Safewards Victorian trial final evaluation report. Centre for Psychiatric Nursing.

- Havilla, S., Alanazi, F. K., Boon, B., Patton, D., Ho, Y. C., & Molloy, L. (2023). Exploring the impact of a multilevel intervention focused on reducing the practices of seclusion and restraint in acute mental health units in an Australian mental health service. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 33(2), 442–451. Early view. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.13255

- Hedlund Lindberg, M., Samuelsson, M., Perseius, K. I., & Björkdahl, A. (2019). The experiences of patients in using sensory rooms in psychiatric inpatient care. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28(4), 930–939. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12593

- Hitch, D., Wilson, C., & Hillman, A. (2020). Sensory modulation in mental health practice. Mental Health Practice, 26(6), 10–16. https://doi.org/10.7748/mhp.2020.e1422

- Jackson-Blott, K., Hare, D., Davies, B., & Morgan, S. (2019). Recovery-oriented training programmes for mental health professionals: A narrative literature review. Mental Health & Prevention, 13, 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2019.01.005

- Lipskaya-Velikovsky, L., Bar-Shalita, T., & Bart, O. (2015). Sensory modulation and daily-life participation in people with schizophrenia. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 58, 130–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.12.009

- Lloyd, C., King, R., & MaChingura, T. (2014). An investigation into the effectiveness of sensory modulation in reducing seclusion within an acute mental health unit. Advances in Mental Health, 12(2), 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/18374905.2014.11081887

- Machingura, T., Shum, D., Molineux, M., & Lloyd, C. (2018). Effectiveness of sensory modulation in treating sensory modulation disorders in adults with schizophrenia: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 16(3), 764–780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9807-2

- Maker, Y., & McSherry, B. (2019). Regulating restraint use in mental health and aged care settings: Lessons from the Oakden scandal. Alternative Law Journal, 44(1), 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1037969X18817592

- Mashiach Eizenberg, M. (2011). Implementation of evidence‐based nursing practice: Nurses’ personal and professional factors? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67(1), 33–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05488.x

- McSharry, P., & O'Grady, T. (2021). How coaching can assist the mental healthcare professional in the operationalization of the recovery approach. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 57(2), 844–851. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12625

- Molloy, L., Lakeman, R., & Walker, K. (2016). More satisfying than factory work: An analysis of mental health nursing using a print media archive. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 37(8), 550–555. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2016.1189634

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2012). Methods for the development of NICE public health guidance (3rd ed.). NICE Process and Methods Guides. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg4/chapter/appendix-h-quality-appraisal-checklist-qualitative-studies

- New South Wales Ministry of Health. (2017). Review of seclusion, restraint and observation of consumers with a mental illness in NSW Health facilities. NSW Ministry of Health.

- Noblit, G. W., & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies (Vol. 11). Sage.

- Novak, T., Scanlan, J., McCaul, D., MacDonald, N., & Clarke, T. (2012). Pilot study of a sensory room in an acute inpatient psychiatric unit. Australasian Psychiatry: Bulletin of Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, 20(5), 401–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856212459585

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery (London, England), 88, 105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

- Phipps, M., Molloy, L., & Visentin, D. (2019). Prevalence of trauma in an Australian inner city mental health service consumer population. Community Mental Health Journal, 55(3), 487–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-018-0239-7

- Quinn, M., Jutkowitz, E., Primack, J., Lenger, K., Rudolph, J., Trikalinos, T., Rickard, T., Mai, H. J., Balk, E., & Konnyu, K. (2024). Protocols to reduce seclusion in inpatient mental health units. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.13277

- Reid, D. H. (2017). 2 - Competency-based staff training. In J. K. Luiselli (Ed.), Applied behavior analysis advanced guidebook (pp. 21–40). Academic Press., https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-811122-2.00002-4

- Sattar, R., Lawton, R., Panagioti, M., & Johnson, J. (2021). Meta-ethnography in healthcare research: A guide to using a meta-ethnographic approach for literature synthesis. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-06049-w

- Scanlan, J. N., & Novak, T. (2015). Sensory approaches in mental health: A scoping review. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 62(5), 277–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12224

- Scott, H. (2021). Implementation of sensory modulation for de-escalation on an adolescent, female psychiatric inpatient unit. Doctor of Nursing Practice Papers. Paper 118. https://ir.library.louisville.edu/dnp/118

- Sivak, K. (2012). Implementation of comfort rooms to reduce seclusion, restraint use, and acting-out behaviors. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 50(2), 24–34. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20110112-01

- Smith, S., & Jones, J. (2014). Use of a sensory room on an intensive care unit. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 52(5), 22–30. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20131126-06

- Sutton, D., Wilson, M., Van Kessel, K., & Vanderpyl, J. (2013). Optimizing arousal to manage aggression: A pilot study of sensory modulation. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 22(6), 500–511. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12205

- Sutton, D., Nicholson, E. (2011). Sensory modulation in acute mental health wards: A qualitative study of staff and service user perspectives. The National Centre of Mental Health Research, Information and Workforce Development (Te Pou). https://hdl.handle.net/10292/4312

- Thornicroft, G., Mehta, N., Clement, S., Evans-Lacko, S., Doherty, M., Rose, D., Koschorke, M., Shidhaye, R., O’Reilly, C., & Henderson, C. (2016). Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental-health-related stigma and discrimination. Lancet, 387(10023), 1123–1132. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00298-6

- Väkiparta, L., Suominen, T., Paavilainen, E., & Kylmä, J. (2019). Using interventions to reduce seclusion and mechanical restraint use in adult psychiatric units: An integrative review. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 33(4), 765–778. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12701

- Walker, J. S., & Baird, C. (2019). Using “remote” training and coaching to increase providers’ skills for working effectively with older youth and young adults with serious mental health conditions. Children and Youth Services Review, 100, 119–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.02.040

- Wand, T., Isobel, S., & Kemp, H. (2024). An audit and analysis of electro convulsive therapy patient information sheets used in local health districts in New South Wales Australia. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.13318

- West, M., Melvin, G., McNamara, F., & Gordon, M. (2017). An evaluation of the use and efficacy of a sensory room within an adolescent psychiatric inpatient unit. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 64(3), 253–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12358

- Williamson, P., & Ennals, P. (2020). Making sense of it together: Youth & families co‐create sensory modulation assessment and intervention in community mental health settings to optimise daily life. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 67(5), 458–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12681

- Wright, L., Bennett, S., & Meredith, P. (2020). ‘Why didn’t you just give them PRN?’: A qualitative study investigating the factors influencing implementation of sensory modulation approaches in inpatient mental health units. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29(4), 608–621. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12693

- Wright, L., Bennett, S., Meredith, P., & Doig, E. (2023). Planning for change: Co-designing implementation strategies to improve the use of sensory approaches in an acute psychiatric unit. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 44(10), 960–973. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2023.2236712