Abstract

This systematic review aims to synthesise the research on children’s perceptions and experiences of their involvement in a parent’s mental health care. After an extensive search and quality appraisal, 22 articles remained and were included in the review. The results show that children—although resourceful and with good intentions—frequently felt excluded. They hungered for information and felt their questions were abandoned. They also felt caught in a tumultuous life situation and struggled for support. Finally, they expressed the need to be seen and ultimately did not feel involved in their parent’s mental health care.

Introduction

Family involvement in mental health care has received increased attention, and there is a growing consensus in policies and clinical guidelines that families should be involved. Nevertheless, the implementation of involving activities targeting children with a parent in need of care is poorly understood. Children of Parents with a Mental Illness (COPMI) often struggle in their daily life and try to maintain the picture that they have a normal family life. At the same time, they try to understand their parent and often feel responsible for supporting the parent and managing everyday life activities (Aldridge, Citation2006; Gladstone et al., Citation2011). Healthcare staff have a unique and important task in recognising COPMI’s needs and right to information and involving them in their parent’s care. However, healthcare staff perceive it difficult to talk to COPMI about their parent, and this could hinder COPMI’s involvement in care (Foster et al., Citation2018).

Background

COPMI could have difficulties handling their daily life as well as understanding and knowing how to cope with the fact that their parent sometimes displays deviant behaviour (Dam & Hall, Citation2016; Gladstone et al., Citation2011). Previous research has shown that COPMI often have a close relationship with their parents, but some children choose to distance themselves from their parent and begin to act as an independent individual, which could be seen as a risk factor for behavioural problems (Gladstone et al., Citation2011). However, children often take great responsibility in their family when a parent has a mental or physical illness or disability (Gladstone et al., Citation2011; Lewis et al., Citation2023). According to a Swedish report, 72% of adolescent children as next of kin provided care, support, or assistance to their parent and the whole family (Brolin et al., Citation2022). Thus, all children (not only those with a parent with mental illness) are often involved in care at home (Brolin et al., Citation2022; Gladstone et al., Citation2011; Lewis et al., Citation2023). It has also been stated that COPMI experience clinical signs of anxiety during their parent’s hospitalisation, but at the same time, they also feel happy to see their parent/relative in the hospital and are eager to interact with them (Sivec et al., Citation2008). O’Brien et al. (Citation2011) found in their study that mental healthcare staff did believe that children visiting their parent at the hospital was beneficial for both the children and the parent. Nevertheless, staff also experienced that it was difficult to know how to talk to children about their parent’s illness.

COPMI who experience difficulty when their parent is hospitalised provides mental healthcare staff with an opportunity to interact with them and offer some kind of support. In a recent article, Reupert et al. (Citation2022) suggest principles and recommendations for how to support COPMI. They propose that staff in mental healthcare need to engage with the children to identify and respond to their needs and provide them with education and training programmes with a children- and family-centred focus. In an intervention study with a family focus using “Family talk” to reduce the risk of transgenerational psychopathology, Furlong et al. (Citation2021) found that healthcare staff perceived that these talks could reduce worries among family members and that it was important for them to be seen and recognised in their reality.

How the children perceive the information, advice and support they receive from mental healthcare staff is also strongly influenced by how they experience involvement in mental health care. A plethora of concepts is used in the literature to describe various forms of involvement such as participation, engagement, inclusion, and collaboration (Jerofke-Owen et al., Citation2023). In this study, we use the term involvement to include all these terms. However, it can be viewed as complicated to involve COPMI in the parent’s mental health care due to the general perceptions that childhood should be free from extensive caring responsibilities (Gladstone et al., Citation2011; Nap et al., Citation2020). It could also be due to parents’ reluctance to be visited by their children, because of self-stigma, fear, shame, and a deep desire to protect their children from frightening experiences within the mental health care context (Foster et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, mental healthcare staff’s time and resource pressures; as well as limited guidelines, experiences and skills; can hinder the staff from talking to a patients’ COPMI (Foster et al., Citation2018), leaving them to feel sympathy or fear. This can result in difficulties maintaining a dual focus on the needs and experiences of parents and their children (Tchernegovski et al., Citation2018). This may, in turn, lead to keeping the main focus on the logistics and practicalities of, for example, which rooms to use when children visit their parent at the mental health hospital unit (Foster et al., Citation2018).

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) stipulates that all children have the right to be heard in all matters concerning them (United Nations, Citation1989). In addition, some countries have specific legislation concerning children’s rights when their parent has a long-term health-related condition. Examples of such specific legislation can be found in Sweden (SFS, Citation2017), Norway (Helsepersonelloven, Citation1999), Finland (Hälso- och sjukvårdslag, Citation2010), and the United Kingdom (e.g. The Children Order (Northern Ireland) (1995), The Carers Act (Scotland) (2016), The Social Services and Well-being Act (Wales) (2014), The Care Act (England) (2014) and The Children and Families Act (Citation2014) in the UK). However, in many countries, there is a lack of legislation on children’s rights when their parent has a long-term illness. The recognition of the children’s needs is in those cases reliant upon non-specific legislation related to children, education, health and social care (Leu et al., Citation2022).

In sum, despite several legislative acts and recommendations, it can be difficult for COPMI to become involved in their parents’ care due to the lack of routines in mental health care, demanding work environments and healthcare staff’s uncertainty when it comes to approaching COPMI. Previous reviews on involvement have primarily focused on patients’ own perspective concerning their participation in health care or mental health care or applied a health care professional or family perspective (e.g. Doody et al., Citation2017; Jørgensen & Rendtorff, Citation2018; Vahdat et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, those reviews addressing a children’s perspective chose to focus on the experiences of living or having a parent with mental illness (Aldridge, Citation2006; Dam & Hall, Citation2016; Gladstone et al., Citation2011; Yamamoto & Keogh, Citation2018) and did not specifically examine children’s views on their involvement in their parent’s care. To fill this void, this systematic review aims to synthesise qualitative research on COPMI’s perceptions and experiences regarding involvement in a parent’s mental health care.

Method

This review of qualitative research followed the guidelines for systematic literature reviews proposed by Bettany-Saltikov and McSherry (Citation2016) and was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses -PRISMA (Page et al., Citation2021). This systematic review synthesises subjective and narrative data to provide a deeper understanding of COPMI’s perceptions and experiences.

Search strategy

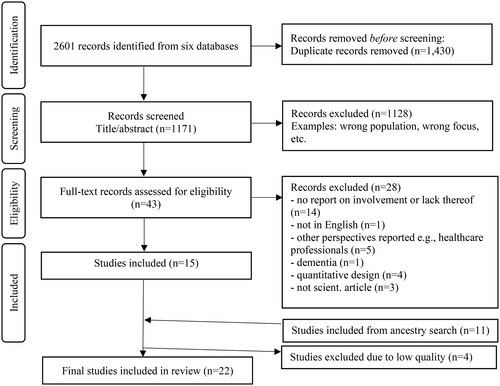

A comprehensive data search was performed in six databases (PsycInfo, Cinahl, Web of Science Core, Medline, Scopus, and Assia) in December 2023 by combining four blocks consisting of free text key words and/or subject headings. Those blocks covered 1) the involvement of, 2) children and young people of, 3) parent with mental illness in, and 4) context of psychiatric and mental health care, as shown in .

Table 1. Keywords/subject headings.

The following criteria were applied: 1) empirical and 2) peer-reviewed articles, 3) written in English, reporting on 4) children of parents with a mental illness and their perspective on their involvement in their parent’s mental health care. Articles were also included when clearly reporting on the lack of involvement in care. Eligible articles considered included any types of empirical qualitative studies and mixed studies where qualitative data and analysis was included as one part of the study.

No time limitations concerning publication years were applied. Moreover, no age limitation was set for the participants, i.e. studies that were based on previous childhood experiences of adult children were also included. In this review, childhood refers to all ages from pre-school and school age, adolescence and young adulthood, up till 25 years (c.f. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Citation2023; United Nations, Citation2023). All types of parental mental illness were included, such as parental mental illness as self-reported by the children. Dementia or Alzheimer’s disease were, however, excluded. If articles reported on children’s experiences of siblings’ mental illness, they were excluded, as were articles investigating children’s experiences of mental illness in family members other than parents. Literature reviews and grey literature were also excluded. If multiple perspectives were reported, the articles were included if it was clearly indicated that the children’s perspective was clearly expressed. Finally, although the search was not limited to any particular study design at the initial stage, later at the screening stage, quantitative studies were excluded (n = 4) since they did not include qualitative data on COMPMI’s perceptions or experiences.

This systematic search resulted in 2601 records. Thereafter, duplications were removed according to Bramer’s et al. guidelines (Citation2016) leaving 1171 potential records. Those records were screened according to title/abstract level, followed by full-text level, by RB, MR and MS. After the final screening, 15 eligible articles were identified as relevant to the review. To be as inclusive as possible, an ancestry search was performed on those 15 articles which resulted in an additional 11 articles. The selection process is shown in .

Quality appraisal

The initial 26 included studies were critically appraised concerning methodological quality using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist for qualitative research (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, Citation2018). The CASP checklist is a generic and commonly used tool in, for example, COCHRANE and World Health Organisation guidelines (Noyes et al., Citation2018). The checklist consists of ten questions with a numeric value representing each answer (yes = 1; no/can´t tell = 0). All numeric values, based on subjective assessments, were summarised to create a quality summary of each study. Four studies were excluded from this review based on the quality. The initial appraisal was conducted by HT and then re-appraised by the remaining authors. The summary of quality assessment for the final 22 included studies is presented in .

Table 2. Included articles.

Analysis

The analysis followed the stepwise analysis proposed by Bettany-Saltikov and McSherry (Citation2016). To start with, all articles were read and reread to become familiar with the content and immerse all authors in the data. In the next step, the relevant data fractions from the articles that answered the review’s aim were identified and marked. Next, all relevant data were extracted into a separate document and openly coded by MS. After this, the data were grouped after patterns that emerged from the data by MS and MR individually. In the next step, MS and MR worked together and compared their patterns, and structured, named and renamed their sub-themes. Finally, HT and MS independently and together re-structured and renamed the sub-themes and generated new themes, which then were presented to the whole research team and discussed. HT then presented the final version of one main theme and sub-themes, which were discussed in the research team until consensus was reached. In order to make the presentation of results easy to read, only examples of references are given.

Results

The 22 included articles had a mix of qualitative designs, whereof six used a retrospective or semi-retrospective design where adults described their childhood experiences. The majority used individual interviews as a data collection method, followed by focus groups. The majority also used various forms of qualitative content analysis to analyse the data. The articles were published between 1993 and 2021 and originated from several different countries, predominately representing high- and middle-income countries such as Australia, Sweden and the UK. In four articles, there were no description of ethical approval/considerations. A summary of the included articles is shown in . The analysis resulted in one theme and three sub-themes, synthesising and abstracting the COPMI’s experiences of their involvement in the mental health care of their parent.

Being resourceful with good intentions but frequently feeling left outside in the dark

COPMI experience a challenging life situation, both at home and during their parent’s hospitalisation. They struggled to understand the parent’s difficulties and conditions and contribute and help their parent to feel better. There were glimpses of supportive environments and healthcare staff, but the COPMI frequently experienced a non-inclusive and non-supportive atmosphere that left them alone and in the dark with uncertainty and unanswered questions. However, they often took matters into their own hands and showed great initiative, capability and resources that could help them to manage their complex life situation better by searching for support and answers on their own. The theme is further illustrated in the three sub-themes “Striving to understand while being abandoned with questions and uncertainty,” “Struggling for support in a tumultuous life situation” and “Wanting to be seen and to contribute in a tangled territory.”

Striving to understand while being abandoned with questions and uncertainty

A core aspect of COPMI experiences of involvement in mental health care for a parent was to be able to understand and gain knowledge of aspects relating to the parents’ mental illness and care. The COPMI felt included in those few instances when they received information and knowledge from mental healthcare staff (e.g. Liu et al., Citation2022). In most studies, a profound desire to acquire information, explanations and knowledge was described. This was expressed as hungering for knowledge and hunting for information. Only two studies described a wish not to receive information and gain more knowledge out of a fear of feeling more burdened (Stallard et al., Citation2004; Strand & Meyersson, Citation2020). The dominant experience was, however, a feeling of being excluded and left alone with questions, rarely receiving any information or explanation regarding the parent’s mental illness, change of behaviour and treatment plan. In addition, vague, ambiguous and difficult information with difficult medical language added to their concerns and questions. Not receiving information and explanations increased their distress and suffering (Knutsson-Medin et al., Citation2007), where not understanding or feeling uncertain caused extra concern and fear (Mordoch, Citation2010; Trondsen, Citation2012). Not knowing was expressed as more scary compared to knowing the truth (O’Brien et al., Citation2011). Fear, uncertainty and a sense of being alone were core experiences resulting in a non-existing involvement in the parent’s care and situation.

Lack of information, knowledge and understanding left the COPMI alone to make sense of their parent’s mental illness and behaviours in their own terms. They could sense that something was wrong and acknowledged a change but did not understand why and for what reason (Metz & Jungbauer, Citation2021; Widemalm & Hjärthag, Citation2015). This could lead to unfortunate misinterpretations of the situation and the parent’s behaviour, for example, that the parent had been “naughty” and gone to prison (Stallard et al., Citation2004). For some, their parent’s behaviour was believed to be caused or worsened by the COPMI, causing concern and guilt (Dunn, Citation1993; O’Brien et al., Citation2011). Others associated the hospital with physical illness and death, which caused unnecessary fear (Mordoch, Citation2010). The lack of initiatives from adults, such as mental healthcare staff, regarding information and explanation made many of the COPMI take matters into their own hands. They contacted the health care or medical support themselves but wished the initiative would come from the adults. They searched for information through varying sources such as online discussion forums, the internet, libraries at school, and open lectures (Garley et al., Citation1997; Tanonaka & Endo, Citation2021; Widemalm & Hjärthag, Citation2015). A desire for psychoeducation in various forms was expressed. Some tried to understand their situation by comparing their family with others, such as those of friends, or by comparing the situation over time, all with the main purpose of gaining better knowledge and understanding of their parent’s mental illness, behaviour and treatment.

Struggling for support in a tumultuous life situation

Having a parent in need of mental health care was difficult and had a profound impact on the COPMI’s life situation and health. The often chaotic life situation and lack of attention and support left the COPMI alone and unable to feel involved in the parent’s care. They often felt alone in the informal caregiving of their parent (Ali et al., Citation2012), and a parent’s hospitalisation was a difficult time with feelings of separation from the parent and a problematic impact on life and school (Metz & Jungbauer, Citation2021). This could, for example, lead to a feeling of being different compared to friends (Foster, Citation2010).

The lonely and chaotic life situation created great needs for COPMI to feel supported and heard. They worried about their own situation and mental health (O’Brien et al., Citation2011), and were sad and lonely, without a needed parent or someone else to discuss it with (Dam et al., Citation2018; O’Brien et al., Citation2011). The COPMI had a great desire for attention and support, which is needed to create feelings of involvement in the parents’ care, but these needs were rarely met. The COPMI wanted to be taken seriously, and receive professional patience and openness (Tabak et al., Citation2016).

Many expressions from the COPMI were related to needs of support in all areas of life such as homebased support, support in school and support by healthcare staff relating to their parent’s care. These could include practical support, financial support, domestic support, logistic support and counselling (e.g. Bee et al., Citation2013). Some preferred anonymous support (Grové et al., Citation2016) and others wanted support in groups (Fudge & Mason, Citation2004). The support was experienced to be more beneficial if the child separated from the parent (Gellatly et al., Citation2019). Family support, for example, family meetings, created mixed feelings with some, who experienced it as embarrassing and fearful, although others saw it as valuable (Dunn, Citation1993; Fudge & Mason, Citation2004). The COPMI were critical of healthcare staff’s lack of initiatives and understanding regarding their needs for attention, support and involvement in care. They welcomed more professional support and staff trained in working with COPMI (Foster, Citation2010; Knutsson-Medin et al., Citation2007; O’Brien et al., Citation2011; Tabak et al., Citation2016). For many, the “only way to handle the situation [was] by helping themselves” (Östman, Citation2008, p. 356).

Wanting to be seen and to contribute in a tangled territory

The physical environment and psychosocial climate at mental health in-patient wards was important for the COPMI’s possibilities to be involved in their parent’s care. The COPMI felt torn with regard to hospitalisation. On the one hand, they felt a relief when the parent was admitted and away from home (Garley et al., Citation1997), yet on the other hand, they felt a reluctance or even fear to visit what was experienced as scary facilities (Dam et al., Citation2018). Nevertheless, in order to be involved in a parent’s care, visits during hospitalisation were needed. For many, having contact with the parent and being able to visit was experienced as valuable, but some had poor access to their parent or were not allowed to visit (Fudge & Mason, Citation2004; Garley et al., Citation1997; Martinsen et al., Citation2019; Stallard et al., Citation2004). The COPMI wanted the parent to feel better and believed that their visit would help and could contribute to recovery (O’Brien et al., Citation2011). Moreover, they thought that their personal knowledge of the parent could help the staff (Ali et al., Citation2012), but this was rarely asked for.

The mental health facilities were often experienced as unsafe, unwelcoming and child-unfriendly (Fudge & Mason, Citation2004; Martinsen et al., Citation2019; O’Brien et al., Citation2011). For some, visits could be experienced as terrifying and led to guilt and pain (Dunn, Citation1993). During visits it could be difficult to see the parent’s mental illness and situation, creating hopelessness with a fear that the parent would never get well (Dam et al., Citation2018). Leaving the parent could also be particularly difficult for some children (Fudge & Mason, Citation2004). The COPMI’s wanted a care environment that enabled a sense of privacy (Fudge & Mason, Citation2004; Martinsen et al., Citation2019) and shed a homily, friendly and happy atmosphere with colours, art and spacious rooms (Fudge & Mason, Citation2004; Martinsen et al., Citation2019; O’Brien et al., Citation2011), an atmosphere that felt welcoming, inviting the COPMI to be heard, recognised and involved in the care. However, such an atmosphere was only rarely experienced in relation to the (non-existing) relationship with healthcare staff.

The COPMI were often critical to the mental healthcare staff and their lack of effort in involving them. They described an atmosphere of distant and unavailable staff who failed to recognise the COPMI and rarely showed any concern for them (Foster, Citation2010; Knutsson-Medin et al., Citation2007; Martinsen et al., Citation2019). For some, meeting the healthcare staff was described as a positive experience referred to as “secure and nice” and “nice and likeable” (Strand & Meyersson, Citation2020). When visiting the mental health in-patient facilities, the COPMI hoped for natural access to someone to talk to, but instead they felt that the staff was not interested in them, which could create feelings of insecurity, fear and exclusion. Some felt powerless and disappointed by the care given, which created hateful feelings towards mental healthcare (Widemalm & Hjärthag, Citation2015).

Discussion

This systematic review synthesised research concerning COPMI’s perspectives of being involved in a parent’s mental health care in order to enhance our understanding of COPMI’s experiences and needs. When synthesising and analysing the data from the 22 included studies, we discovered rather disheartening results from the COPMI regarding their experiences of involvement in the older as well as the newer studies. Their sense of a lack of involvement was integrated in their overall life situation and their unmet needs for support in all aspects of life, which were not isolated to a specific care situation and their parents’ health and care. There are numerous relevant aspects worthy of discussion and reflection concerning the present results; nevertheless, we concentrate the following discussion on the meaning of involvement related to a child’s perspective.

We used a broad understanding of the concept’s involvement due to its complex use and understanding depending on theoretical foundations and different perspectives of who is in focus when describing involvement. The use and understanding of this phenomenon may differ in terms of how various professionals conceptualise the COPMI’s role and needs when it comes to involvement. Therefore, this review strove to emphasise COPMI’s own perspectives regarding their involvement. Considered from different perspectives, the meaning of the term “involvement” appears to vary. Thus, “involvement in health care” does not necessarily mean the same thing to COPMI as it does to the adults around them. From an adult perspective, “involvement in health care” often includes being involved in making decisions about and planning for care and treatment alternatives, and it may be considered inappropriate to involve a child in these matters regarding the parent’s mental health care. Furthermore, adults’ attempts to adopt a child’s perspective are often based on the idea that childhood should be free from extensive caring responsibilities (Gladstone et al., Citation2011; Nap et al., Citation2020) and parents may therefore have a desire to protect their children from being extensively involved (Foster et al., Citation2018).

From COPMI’s perspective, their need to be involved in their parent’s mental health care includes a desire to better understand the parent’s conditions. The COPMI want to have information and knowledge about the parent’s mental illness, and it needs to be presented to them in a way that is easy to understand. The results show that most COPMI are eager to gain as much knowledge as possible to be able to know more about how they can act when their parent suffers from mental illness. They want this information to come from other adults as well as from the mental healthcare staff, but most often they experience that their need of information is sparsely met. When the COPMI visit their parent in a mental health in-patient facility, they quite often feel ignored and that the staff was not interested in talking with them. On the other hand, some COPMI report that mental healthcare staff tried to engage COPMI by asking them if they could be of any help. Also, in a recent study, COPMI have positive experiences of meeting mental healthcare staff (Strand & Meyersson, Citation2020). In previous reviews it has been pointed out that COPMI try to understand their mentally ill parent (Aldridge, Citation2006; Gladstone et al., Citation2011). At the same time, mental healthcare staff find it difficult to know how to talk to the COPMI about the parents’ illness (O’Brien et al., Citation2011). Hence, even though it has been reported that COPMI struggle with understanding and helping their parent, there are studies that show some good examples of when COPMI are taken seriously and have an opportunity to receive help from the healthcare staff.

According to recent research, COPMI are often involved in their parent’s care at home (Brolin et al., Citation2022; Gladstone et al., Citation2011; Lewis et al., Citation2023), and this literature review shows that COPMI want to remain involved during their parent’s hospitalisation. Unfortunately, some COPMI had poor access to or were not allowed to visit their parent at the hospital. According to the UNCRC, all children have the right to be heard in all matters concerning them, but this study’s results show that COPMI’s voices are seldom heard. The lack of attention from adults made COPMI feel, on the one hand, alone in their responsibility concerning the informal care of their parent and left out on the other when it came to formal care. The present review also shows that COPMI often have information about their parent that could be useful for the staff and that they want to contribute with their personal experience and knowledge as a way to assist the staff in understanding the parent better. The COPMI did not express any desire to be involved in decisions about care and treatment alternatives, but they felt they possessed personal knowledge that could be useful in the mental health care for their parent. Therefore, they wanted the healthcare staff to involve them in the care of their parent by listening to the COPMI, taking their experiences and knowledge seriously, and showing a professional openness. In sum, COPMI had a need for an information exchange, especially one where their personal experiences and knowledge of their parent are given as much value as the experiences and knowledge of the healthcare staff.

There is need for tailored educational and supportive interventions targeting COPMI during in-patient hospitalisation, where a child’s perspective on involvement is reflected upon and advocated by nurses. This includes conversations about the COPMI’s whole life situation (Yamamoto & Keogh, Citation2018). Yamamoto and Keogh (Citation2018) implicate further that nurses are in a position where they can offer age-appropriate and timely support and information to COPMI in order to assist in enhancing their coping and resources. Our review also found that the COPMI had resources and capacity that was not used by healthcare staff and forced the COPMI to undergo a strenuous and lonesome journey to find answers, information and support elsewhere. The COPMI developed and used different strategies; and they had resources that healthcare and nurses could use and enhance when involving the COPMI in their parent’s care. Current trends in psychiatric and mental health care, involving fewer in-patient beds and shorter hospitalisations, emphasise an urgent need for the COPMI to be involved and support both planning and the situation at home. Nurses are in a unique position to use both out-patient and in-patient care situations to more effectively support the COPMI in suitable involvement that helps the COPMI and their parents enhance and use existing resources to ensure the situation at home and in school functions between care visits and contacts.

Thus, a central question is how to develop support and common practice, structural work processes, and a way to support COPMI’s learning, understanding, use of resources, etc. A structured and systematic approach in clinical practice might be especially important since nurses and healthcare professionals might feel burdened by a sense of responsibility towards COPMI. Tchernegovski et al. (Citation2018) found that healthcare professionals use different strategies in their encounter with COPMI. Some only focus on COPMI’s well-being if there are signs of abuse or neglect. Others became overwhelmed by sympathy and overly focused on COPMI. Both approaches might be results of a burdensome responsibility and feelings of helplessness towards COPMI’s situation. Thus, there seems to be an urgent need to develop routines and practices in psychiatric and mental health care that can properly support nurses and healthcare staff in their interaction with COPMI.

Strengths and limitations

When conducting a literature review, there is always a risk of missing relevant articles. However, we have tried to be as extensive and exhaustive in our search strategy as possible by including six databases and by performing an ancestry search. The included articles were critically appraised concerning their methodological quality by one researcher, who used the CASP checklist, and this was later re-appraised by the entire team and we believe this to be a strength. A possible limitation could be including studies older than 15 years (n = 5) since the importance of involving children as next of kin in the care have been noticed in legislation, regulations and routines during the last decades. On the other hand in the results of this study we found that there still are a lack of involvement from the children perspective. Notably, several of the studies did not describe any ethical considerations or ethical approval, which is surprising considering the research questions and samples targeted in the studies. Some of the included studies applied a retrospective perspective, which could pose a risk for recall bias and thus impact on the trustworthiness of our review’s results. Finally, we chose to define childhood up until 25 years of age, presumably including young adulthood stage.

Conclusion

To involve COPMI in mental health care could be problematic. As mental healthcare staff there are several aspects to consider. The COPMI need to be seen as having valuable information and experiences that could be of help for the staff in their care of the parent. At the same time, many COPMI need help with understanding their parent’s behaviour and treatment plan. There are studies that show some good examples of when COPMI are taken seriously and have an opportunity to receive help from the healthcare staff, but since we have limited knowledge about how healthcare staff can allow COPMI be involved in the care, there is a need for further studies on how information and knowledge could be presented to and exchanged with COPMI.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aldridge, J. (2006). The experiences of children living with and caring for parents with mental illness. Child Abuse Review, 15(2), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.904

- * Ali, L., Ahlström, B. H., Krevers, B., & Skärsäter, I. (2012). Daily life for young adults who care for a person with mental illness: A qualitative study. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 19(7), 610–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01829.x

- * Bee, P., Berzins, K., Calam, R., Pryjmachuk, S., & Abel, K. M. (2013). Defining quality of life in the children of parents with severe mental illness: A preliminary stakeholder-led model. PloS One, 8(9), e73739. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073739

- Bettany-Saltikov, J., & McSherry, R. (2016). How to do a systematic literature review in nursing: A step-by-step guide. (2nd Ed.). Open University Press.

- Bramer, W. M., Giustini, D., de Jonge, G. B., Holland, L., & Bekhuis, T. (2016). De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA, 104(3), 240–243. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.104.3.014

- Brolin, R., Magnusson, L., & Hanson, E. (2022). Unga omsorgsgivare. Svensk kartläggning – delstudie i det europeiska ME-WE-projektet. Nationellt Kompetenscentrum Anhöriga. Rapport Barn Som Anhöriga, 2022, 1.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2018). CASP checklist. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

- Dam, K., & Hall, E. O. (2016). Navigating in an unpredictable daily life: A metasynthesis on children’s experiences living with a parent with severe mental illness. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 30(3), 442–457. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12285

- * Dam, K., Joensen, D., & Hall, E. (2018). Experiences of adults who as children lived with a parent experiencing mental illness in a small-scale society: A qualitative study. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 25(2), 78–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12446

- Doody, O., Butler, M. P., Lyons, R., & Newman, D. (2017). Families’ experiences of involvement in care planning in mental health services: An integrative literature review. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 24(6), 412–430. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12369

- * Dunn, B. (1993). Growing up with a psychotic mother: A retrospective study. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 63(2), 177–189. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0079423

- * Foster, K. (2010). ‘You’d think this roller coaster was never going to stop’: Experiences of adult children of parents with serious mental illness. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19(21-22), 3143–3151. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03293.x

- Foster, K. P., Hills, D., & Foster, K. N. (2018). Addressing the support needs of families during the acute hospitalization of a parent with mental illness: A narrative literature review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(2), 470–482. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12385

- * Fudge, E., & Mason, P. (2004). Consulting with young people about service guidelines relating to parental mental illness. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 3(2), 50–58. https://doi.org/10.5172/jamh.3.2.50

- Furlong, M., Mulligan, C., McGarr, S., O'Connor, S., & McGilloway, S. (2021). A family-focused intervention for parental mental illness: A practitioner perspective. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 783161. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.783161

- * Garley, D., Gallop, R., Johnston, N., & Pipitone, J. (1997). Children of the mentally ill: A qualitative focus group approach. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 4(2), 97–103. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2850.1997.00036.x

- * Gellatly, J., Bee, P., Kolade, A., Hunter, D., Gega, L., Callender, C., Hope, H., & Abel, K. M. (2019). Developing an intervention to improve the health related quality of life in children and young people with serious parental mental illness. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 155. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00155

- Gladstone, B. M., Boydell, K. M., Seeman, M. V., & McKeever, P. D. (2011). Children’s experiences of parental mental illness: A literature review. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 5(4), 271–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-7893.2011.00287.x

- * Grové, C., Reupert, A., & Maybery, D. (2016). The perspectives of young people of parents with a mental illness regarding preferred interventions and supports. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(10), 3056–3065. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0468-8

- Helsepersonelloven. (1999). The Norwegian Act on Health Personnel, 1999:2, §10a. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/rundskriv/helsepersonelloven-med-kommentarer/krav-til-helsepersonells-yrkesutovelse#paragraf-10a-helsepersonells-plikt-til-a-bidra-til-a-ivareta-mindrearige-barn-som-parorende

- Hälso- och sjukvårdslag. (2010). The Finnish Act on Healthcare, 2010: 8, §70. https://www.finlex.fi/sv/laki/ajantasa/2010/20101326#L8P70

- Jerofke-Owen, T. A., Tobiano, G., & Eldh, A. C. (2023). Patient engagement, involvement, or participation—Entrapping concepts in nurse-patient interactions: A critical discussion. Nursing Inquiry, 30(1), e12513. https://doi.org/10.1111/nin.12513

- Jørgensen, K., & Rendtorff, J. D. (2018). Patient participation in mental health care–perspectives of healthcare professionals: An integrative review. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 32(2), 490–501. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12531

- * Knutsson-Medin, L., Edlund, B., & Ramklint, M. (2007). Experiences in a group of grown-up children of mentally ill parents. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 14(8), 744–752. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2007.01181.x

- Leu, A., Guggiari, E., Phelps, D., Magnusson, L., Nap, H. H., Hoefman, R., Lewis, F., Santini, S., Socci, M., Boccaletti, L., Hlebec, V., Rakar, T., Hudobivnik, T., & Hanson, E. (2022). Cross-national analysis of legislation, policy and service frameworks for adolescent young carers in Europe. Journal of Youth Studies, 25(9), 1215–1235. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2021.1948514

- Lewis, F. M., Becker, S., Parkhouse, T., Joseph, S., Hlebec, V., Mrzel, M., Brolin, R., Casu, G., Boccaletti, L., Santini, S., D’Amen, B., Socci, M., Hoefman, R., de Jong, N., Leu, A., Phelps, D., Guggiari, E., Magnusson, L., & Hanson, E. (2023). The first cross-national study of adolescent young carers aged 15–17 in six European countries. International Journal of Care and Caring, 7(1), 6–32. https://doi.org/10.1332/239788222X16455943560342

- * Liu, S. H. Y., Hsiao, F. H., Chen, S. C., Shiau, S. j., & Hsieh, M. H. (2022). The experiences of family resilience from the view of the adult children of parents with bipolar disorder in Chinese society. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 78(1), 176–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15008

- * Martinsen, E. H., Weimand, B. M., Pedersen, R., & Norvoll, R. (2019). The silent world of young next of kin in mental healthcare. Nursing Ethics, 26(1), 212–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733017694498

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology. (2023). Changes in young adulthood. MIT https://hr.mit.edu/static/worklife/youngadult/changes.html. Accessed 2 February 2023

- Metz, D., & Jungbauer, J. (2021). “My scars remain forever”: A qualitative study on biographical developments in adult children of parents with mental illness. Clinical Social Work Journal, 49(1), 64–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-019-00722-2

- * Mordoch, E. (2010). How children understand parental mental illness: “You don’t get life insurance. What’s life insurance?”. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 19(1), 19.

- Nap, H. H., Hoefman, R., de Jong, N., Lovink, L., Glimmerveen, L., Lewis, F., Santini, S., D'Amen, B., Socci, M., Boccaletti, L., Casu, G., Manattini, A., Brolin, R., Sirk, K., Hlebec, V., Rakar, T., Hudobivnik, T., Leu, A., Berger, F., Magnusson, L., & Hanson, E. (2020). The awareness, visibility and support for young carers across Europe: A Delphi study. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 921. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05780-8

- Noyes, J., Booth, A., Flemming, K., Garside, R., Harden, A., Lewin, S., Pantoja, T., Hannes, K., Cargo, M., & Thomas, J. (2018). Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group guidance series—Paper 3: Methods for assessing methodological limitations, data extraction and synthesis, and confidence in synthesized qualitative findings. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 97, 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.06.020

- * O'Brien, L., Anand, M., Brady, P., & Gillies, D. (2011). Children visiting parents in inpatient psychiatric facilities: Perspectives of parents, carers, and children. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 20(2), 137–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2010.00718.x

- *Östman, M. (2008). Interviews with children of persons with a severe mental illness—Investigating their everyday situation. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 62(5), 354–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039480801960065

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Online), 372, n71–n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Reupert, A., Bee, P., Hosman, C., van Doesum, K., Drost, L. M., Falkov, A., Foster, K., Gatsou, L., Gladstone, B., Goodyear, M., Grant, A., Grove, C., Isobel, S., Kowalenko, N., Lauritzen, C., Maybery, D., Mordoch, E., Nicholson, J., Reedtz, C., … Ruud, T. (2022). Editorial perspective: Prato Research Collaborative for change in parent and child mental health - Principles and recommendations for working with children and parents living with parental mental illness. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 63(3), 350–353. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13521

- SFS. (2017). The Swedish Healthcare Act 2017:30. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/halso–och-sjukvardslag-201730_sfs-2017-30 (in Swedish)

- Sivec, H. J., Masterson, P., Katz, J. G., & Russ, S. (2008). The response of children to the psychiatric hospitalisation of a family member. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 7(2), 121–129. https://doi.org/10.5172/jamh.7.2.121

- * Stallard, P., Norman, P., Huline-Dickens, S., Salter, E., & Cribb, J. (2004). The effects of parental mental illness upon children: A descriptive study of the views of parents and children. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 9(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104504039767

- * Strand, J., & Meyersson, N. (2020). Parents with psychosis and their children: Experiences of Beardslee’s intervention. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29(5), 908–920. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12725

- * Tabak, I., Zabłocka-Żytka, L., Ryan, P., Poma, S. Z., Joronen, K., Viganò, G., Simpson, W., Paavilainen, E., Scherbaum, N., Smith, M., & Dawson, I. (2016). Needs, expectations and consequences for children growing up in a family where the parent has a mental illness. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 25(4), 319–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12194

- * Tanonaka, K., & Endo, Y. (2021). Helpful resources recognized by adult children of parents with a mental illness in Japan. Japan Journal of Nursing Science: JJNS, 18(3), e12416. https://doi.org/10.1111/jjns.12416

- Tchernegovski, P., Hine, R., Reupert, A. E., & Maybery, D. J. (2018). Adult mental health clinicians’ perspectives of parents with a mental illness and their children: Single and dual focus approaches. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 611. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3428-8

- The Care Act 2014 and Children and Families Act 2014 (Consequential Amendments) Order 2015. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukdsi/2015/9780111128626. Accessed 24 April 2024.

- * Trondsen, M. V. (2012). Living with a mentally ill parent: Exploring adolescents’ experiences and perspectives. Qualitative Health Research, 22(2), 174–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732311420736

- United Nations. (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child.

- United Nations. (2023). Global Issues: Youth. Retrieved April 27, 2023, from https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/youth

- Vahdat, S., Hamzehgardeshi, L., Hessam, S., & Hamzehgardeshi, Z. (2014). Patient involvement in health care decision making: A review. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 16(1), e12454. https://doi.org/10.5812/ircmj.12454

- * Widemalm, M., & Hjärthag, F. (2015). The forum as a friend: Parental mental illness and communication on open Internet forums. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50(10), 1601–1607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1036-z

- Yamamoto, R., & Keogh, B. (2018). Children’s experiences of living with a parent with mental illness: A systematic review of qualitative studies using thematic analysis. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 25(2), 131–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12415