Abstract

Encompassing many crafts, needlecraft has been popular, particularly amongst women, for centuries. This scoping review mapped and explored primary research on sewing, crocheting, knitting, lacemaking, embroidery and quilting and its impact on mental health and well-being. A comprehensive systematic search across PubMed, CINAHL, Scopus and Google Scholar was conducted in January 2024, identifying 25 studies that met the inclusion criteria. Four themes (and 15 subthemes) emerged from the data: (1) mental well-being; (2) social connection, sense of value and belonging; (3) sense of purpose, achievement and satisfaction; and (4) self-identity, family, culture and legacy. The review showed that needlecraft has an overwhelmingly positive effect on mental health and general well-being. This scoping review may be used to inform mental health nurses and other professionals of the benefits of needlecraft for a wide variety of consumers and may also find application in the well-being of healthcare workers.

Introduction

The use of a needle and thread, or yarn, to create an item is known as needlecraft. Besides sewing, needlecraft includes knitting, crocheting, lace making, embroidery and quilting. Evidence exists that textile techniques using eyed needles dates back to the last ice age (Gilligan, Citation2010). Paleolithic man in Eurasia is believed to have used thread and cord to sew skins together to make clothing (Gilligan, Citation2010). In Western society, preceding the 1970s, needlework was considered essential to the Anglo-speaking woman’s role in the home as she made and mended the clothing for her family (Thompson, Citation2022). The skills were passed through generations from mother to daughter and shared amongst enthusiasts. As more women entered the workforce in the 1970s and globalization made mass-produced ready-made clothing affordable, home sewing practices declined (Thompson, Citation2022), relegated mainly to hobby status.

In recent years, women and men have found empowerment in engaging in needlecraft, which is considered a gender-neutral activity (Kargól, Citation2022). Items produced by hand often still have a practical purpose, such as providing clothing, warmth and comfort, but may also have esthetic value or may commemorate a special occasion such as the birth of a baby (Cheek & Yaure, Citation2017; Kargól, Citation2022). Quilts, in particular, have been created to express personal meaning as a symbol of caring and shared experiences (Cheek & Yaure, Citation2017). Wrapping a person in a knitted item to provide warmth and comfort is a symbolic example of caring (Corkhill et al., Citation2014). Needlecraft is integral to many cultures, finding expression through carefully crafted traditional ware and providing a sense of cultural heritage (Kumar, Citation2021).

The benefits of engaging in needlework extend far beyond the practicalities of providing clothing, expressing caring and commemorating occasions; it can also enhance well-being. For example, Burns and Van Der Meer (Citation2021) state that crocheting is as effective as meditation. Meditation has been shown to improve attention, which plays a pivotal role in advanced cognitive function (Kwak et al., Citation2019.) Knitting, as a daily creative activity, is often cited in the literature as a therapy to relieve symptoms of grief, loneliness and idleness (Kargól, Citation2022). Knitting has also been associated with reducing burnout and compassion fatigue in healthcare workers, temporarily allowing them to escape their profession’s demands (Anderson & Gustavson, Citation2016). Quilting has been used to create art and to learn about oneself with each layer of fabric, akin to digging deeper into one’s thoughts and feelings (Bookbinder, Citation2016). Engaging in needlework has been recognized for its positive effects on mental health, fostering mindfulness, reducing stress levels, and alleviating symptoms of anxiety and depression (Scott & Williams, Citation2024). By focusing on the needlework task, individuals may find a therapeutic outlet that promotes relaxation and mental clarity (Corkhill et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, the handiwork may provide a sense of accomplishment and the opportunity for creative expression. This may enhance emotional well-being, making needlework a valuable tool in maintaining and improving mental health. Such literature suggests a link between needlecraft and mental well-being.

A range of concepts incorporate well-being, such as quality of life, mood enhancement, self-esteem and positive mental health (Mansfield et al., Citation2020). It is known that leisure activities increase resilience and promote mental health and well-being (Bowman & Lim, Citation2023; Mansfield et al., Citation2020; Takiguchi et al., Citation2023). Although there is literature on the effect of needlecraft on well-being and mental health, the evidence has not been systematically mapped and consolidated. Therefore, this scoping review aims to map and explore primary research on sewing, crocheting, knitting, lacemaking, embroidery and/or quilting and its impact on mental health and well-being.

Methods

Design

This scoping review was conducted using the five-step approach developed by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) and enhanced by Levac et al. (Citation2010). The steps included (1) identifying the research question, (2) obtaining relevant studies, (3) selecting the studies for inclusion, (4) extracting the data, and (5) collating, summarizing and presenting the results. Unlike systematic reviews, where all relevant studies are evaluated, analyzed and synthesized (Pollock & Berge, Citation2018), a scoping review allows the inclusion of a broader range of data sources, enabling the mapping of evidence and exploring a range of theories and ideas about the topic (Munn et al., Citation2018). The results are reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) (Page et al., Citation2021).

Review aim

The aim of this scoping review is to map and explore primary research related to sewing, crocheting, knitting, and/or quilting and its impact on mental health and well-being.

Eligibility criteria

Included studies encompassed primary research published in English that explored the act of sewing, crocheting, knitting, embroidery and/or quilting and its impact on people’s mental health and well-being. Excluded were articles that addressed other crafts or hobbies that focused on dementia cohorts, articles in languages other than English and case reports, editorials, abstracts, conference proceedings, systematic reviews and theses.

Search strategy

Using electronic databases PubMed, CINAHL, Scopus, and Google Scholar, a comprehensive literature search was conducted on January 5, 2024. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keywords using Boolean operators AND/OR and NOT were used to formulate a search strategy (see ). The search strategy included primary research published in English that did not impose parameters on the publication date.

Table 1. PubMed Search strategy.

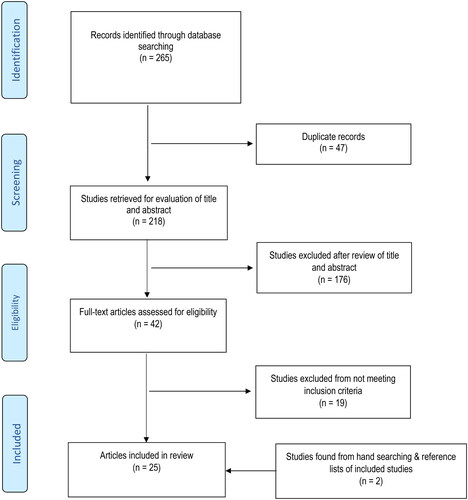

After the 47 duplicates were removed, 218 records were identified. Independently, the titles and abstracts were screened for inclusion, resulting in 42 full-text articles being reviewed. As part of the rigorous search strategy process, free searching and reference lists of included studies were reviewed, resulting in two additional studies being included. The authors resolved disagreements through consultation within the team, resulting in the inclusion of 25 studies in this scoping review (see ).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram describing record inclusion through different stages of screening (Page et al., Citation2021).

Since performing quality ratings when conducting a scoping review is not required, a quality assessment of each included study was not performed. This does not detract from the rigor of this review, as it is necessary for the researchers to critically review both the study methods and results as part of the analysis process (Verdejo et al., Citation2021).

Data extraction and synthesis

A data extraction table (see ) was developed for the 25 included studies, providing an overview of each study’s aims, study cohort, study design, and significant findings. A meta-analysis of the findings was not possible, given the heterogeneity of the included studies.

Table 2. Summary of included studies.

Synthesis of the literature was conducted according to V. Clarke and Braun’s (Citation2017) thematic analysis, a method used to identify, analyze and report themes from a dataset. All team members familiarized themselves with the data by reading and re-reading the included studies. Initial codes were generated for each study and independently verified by three team members. The codes were collated under themes reviewed by team members who collaboratively developed the four overarching themes. A concept matrix was developed to map the themes, subthemes and the alignment of the included studies (see ).

Table 3. Concept mapping of themes and subthemes.

Results

The 25 studies included in this review were from North America (n = 7), Europe (n = 11), Australasia (n = 3), the Middle East (n = 1) and multiple countries (n = 3). Sixteen were qualitative, four were quantitative, three studies included both qualitative and quantitative data and two studies did not describe their methodology but presented both qualitative and quantitative data (Clave-Brule et al., Citation2009; Sjöberg & Porko-Hudd, Citation2019). Eighteen studies were observational, involving respondents who regularly participated in and enjoyed needlecraft. The remaining seven studies used needlecraft as a form of intentional therapy (see ).

Five of the studies collected data through participant interviews, eight used online or paper-based surveys, three used written or spoken narratives, and nine used a combination of data collection methods, including surveys, interviews, narratives, and observations (). Most of the studies involved adult female participants, but two studies focused on adolescent girls (Wolk & Bat Or, Citation2023; York et al., Citation2022).

Themes

The thematic analysis of the data revealed four main themes and 15 subthemes: (1) Mental well-being; (2) Social connection, sense of value and belonging; (3) Sense of purpose, achievement, and satisfaction; (4) Self-identity, family, culture and legacy (see ).

Theme 1: Mental well-being

Calming, relaxation, and managing stress

Almost all studies stated that needlecraft was relaxing, calming, and instrumental in managing stress. Participants referred to knitting as a mentally stimulating stress reliever (Brooks et al., Citation2019), and even in high-stress environments like prison services, knitting was found to significantly lower stress scores (t(81)= −8.015, p < .05) (Maita, Citation2018). The positive impact of needlecraft extends beyond mental well-being to include physical health, such as lowering blood pressure, relieving chronic pain, and helping to modify behaviors such as smoking or alcohol use (Burns & Van Der Meer, Citation2021). The relaxing, healing qualities of needlework were noted by Emanuelsen et al. (Citation2020).

Therapeutic and well-being

Many studies referred to needlecraft as therapeutic, enhancing emotional and mental well-being. Nevay et al. (Citation2019) studied participants’ mental well-being at a needlecraft workshop. They found a statistically significant improvement after participating in textile crafts (t(13)= −3.26, p < .01), with participants commenting on the therapeutic aspects of the techniques used (Nevay et al., Citation2019). For many, needlecraft is a means of surviving life’s events (Burt & Atkinson, Citation2012; Collier, Citation2011; Dickie, Citation2011; Pöllänen & Voutilainen, Citation2018). Dickie (Citation2011) refers to “mundane therapy”, where needlecraft is routinely used to cope with everyday worries, and “exceptional therapy”, where needlecraft is the go-to activity during life’s crises (p. 212). Kenning (Citation2015) refers to the therapeutic nature of lacemaking during bereavement and how lacemaking serves as a catalyst for people to rejoin society. In times of loneliness or isolation, participants find comfort in needlecraft (Mayne, Citation2016), while others base major life decisions, such as where to retire, on the availability of local craft groups (Kenning, Citation2015). Needlecraft is often viewed as an activity for older people, and both Burns and Van Der Meer (Citation2021) and N. A. Clarke (Citation2020) speak of the benefits of needlecraft to enhance well-being in physically less active older people.

Needlecraft has been used as a form of therapy in many studies. Survivors of the Great Japanese Earthquake who participated in a knitting program had a significantly higher subjective happiness score (p < .0001) and quality of life score (p = .013) than those who did not participate (Yuwen et al., Citation2021). Clave-Brule et al. (Citation2009) reported that knitting therapy relieved anxiety and distracted patients with eating disorders. Embroidery has been found to have therapeutic benefits in supporting psychological development in adolescent girls with emotional disorders (Wolk & Bat Or, Citation2023). Quilting has been used as grieving therapy for those affected by HIV/AIDS. Participants reflected that the quilted item captured the memories of their loved ones and allowed them to move on (Kausch & Amer, Citation2007). According to Dickie (Citation2011), when participating in quilting during times of crisis, the end product becomes symbolic of overcoming the crisis.

Diversion and coping

Needlecraft serves as an escape or distraction from daily routines and worries. Being immersed in the task is identified as a divergence from life’s stresses and the “constant barrage of information” (Wolk & Bat Or, Citation2023, p. 11). Needlecraft keeps the brain active while providing mental space to problem-solve (Brooks et al., Citation2019; Emanuelsen et al., Citation2020; Gaspar da Silva, Citation2023) and organize one’s thoughts (Piercy & Cheek, Citation2004; Pöllänen & Voutilainen, Citation2018; Riley et al., Citation2013). Pöllänen and Voutilainen (Citation2018) refer to needlecraft as a mental resource that allows one to deal with past, present, and future worries. Many participants believe that needlecraft focuses one’s mind and prevents thoughts from wandering and dwelling on problems (N. A. Clarke, Citation2020; Gaspar da Silva, Citation2023; Reynolds, Citation2000; Wolk & Bat Or, Citation2023). Burt and Atkinson (Citation2012) describe the creative process as captivating, making participants less self-conscious and helping them relax. Participants describe the craft as rejuvenating (N. A. Clarke, Citation2020; Collier, Citation2011); and focusing on correcting errors in the work is a stress management technique that teaches perseverance (York et al., Citation2022) and helps develop resilience (N. A. Clarke, Citation2020).

Contentment

Almost all study participants expressed an overwhelming joy, happiness, and positive mood when participating in needlecraft. Most were habitual crafters who enjoyed the hobby immensely. Dickie (Citation2011) noted that quilting was a source of great comfort, and Brooks et al. (Citation2019) referred to knitting as dampening negative emotions.

Meditative flow and the sensory aspect of the materials

The meditative, rhythmic nature of needlework is identified as soothing and requires little thought. The soothing repetitive rhythm, often called ‘the flow’ (Burt & Atkinson, Citation2012; Pöllänen & Voutilainen, Citation2018), can create a Zen-like state (Reynolds, Citation2000). Although repetitive motion and static posture can contribute to physical pain, the cognitive and mental benefits were deemed to outweigh the discomfort (Brooks et al., Citation2019). The esthetics and sensory properties of the raw material are thought to relieve stress and appear to be uplifting, while the tangible end product can bring joy to participants (Brooks et al., Citation2019; Kaipainen & Pöllänen, Citation2021; Nevay et al., Citation2019; Pöllänen & Voutilainen, Citation2018). Use of bright colors are reported to bring joy (Burns & Van Der Meer, Citation2021; Collier, Citation2011) and inspiration to the crafters (Pöllänen & Voutilainen, Citation2018).

Theme 2: Social connection, sense of value and belonging

Socializing and a sense of community, friendships, and feeling valued

Many studies suggest that needlecraft provides an opportunity to socialize, whether in person (Court, Citation2020; Kausch & Amer, Citation2007), online (N. A. Clarke, Citation2020; Mayne, Citation2016) or both (Dickie, Citation2011; Pöllänen & Voutilainen, Citation2018). Court (Citation2020) reported that some participants joined knitting groups merely to meet other like-minded women. Being part of a needlecraft group may provide a sense of community (Mayne, Citation2016; Nevay et al., Citation2019), providing external validation even for those who only participate online (N. A. Clarke, Citation2020). Having a common interest promotes conversation with strangers and may lead to new friendships (Clave-Brule et al., Citation2009; Piercy & Cheek, Citation2004), facilitating social interaction (Burns & Van Der Meer, Citation2021; N. A. Clarke, Citation2020; Court, Citation2020; Dickie, Citation2011; Pöllänen & Voutilainen, Citation2018). Connections are reported as strengthened through gifting items (N. A. Clarke, Citation2020; Piercy & Cheek, Citation2004). These handmade items are loaded with emotion, showing mutual care (Emanuelsen et al., Citation2020; Reynolds, Citation2000), and producing a tangible expression of friendship that is perceived to endure even after contact is broken (N. A. Clarke, Citation2020). The role of friendship in social needlecraft is emphasized in several studies (Kausch & Amer, Citation2007; Riley et al., Citation2013).

Many needlecrafters donate their work to charities, making them feel valued in the community (Brooks et al., Citation2019; Reynolds, Citation2000). Needlecraft groups can serve to introduce newcomers to the neighborhood (Court, Citation2020), contributing not only to the crafter’s well-being but also to the health of the community (Emanuelsen et al., Citation2020; Piercy & Cheek, Citation2004). New migrants are often reported to be lonely and marginalized; Gaspar da Silva (Citation2023) used social embroidery to unite immigrant women, help them forge friendships and form a supportive community. Kausch and Amer (Citation2007) used quilting panels to form a supporting community of AIDS survivors, allowing them to share their experiences openly, and facilitating the healing process (Kausch & Amer, Citation2007).

Sharing, collaboration and a sense of belonging

Needlecraft was reported to serve as a vehicle to connect like-minded individuals (Brooks et al., Citation2019; Court, Citation2020), forging supportive friendships (Burt & Atkinson, Citation2012; Piercy & Cheek, Citation2004), and leading to a sense of belonging (Kenning, Citation2015; York et al., Citation2022). For example, Yuwen et al. (Citation2021) used a social knitting program to assist Japanese women in forming friendships and support each other following a natural disaster, and Wolk and Bat Or (Citation2023) used embroidery as a form of art therapy for emotionally vulnerable adolescents who benefited from the social interaction, being able to speak freely while feeling accepted and supported in a non-judgmental environment (Wolk & Bat Or, Citation2023).

Even during periods of social isolation, needlecraft can facilitate supportive virtual communities. According to Mayne (Citation2016), sharing images of needlework items online is not only about the craft; it reveals personal stories and exhibits the needle crafter’s respect and care for their family, embodying a sense of belonging and kinship, central to mental health and well-being.

Mutual learning and encouragement

Socializing through needlecraft groups can provide an opportunity for mutual learning (Kenning, Citation2015; Rusiñol-Rodriguez et al., Citation2020). Participants can obtain technical support and advice from other crafters (Brooks et al., Citation2019; Court, Citation2020; Pöllänen & Voutilainen, Citation2018). They share ideas, learn new skills, encourage and motivate each other (Mayne, Citation2016; Riley et al., Citation2013). According to Reynolds (Citation2000), teaching new skills to others provides a sense of community status and may boost the teacher’s self-esteem. Participants in the Burt and Atkinson (Citation2012) and Nevay et al. (Citation2019) studies stated that seeing other people’s work inspires them. Several studies report that participants take pleasure in others’ successes (Court, Citation2020; Dickie, Citation2011; Kenning, Citation2015; Mayne, Citation2016; Sjöberg & Porko-Hudd, Citation2019), and the praise they receive for their work serves as validation of their skills (N. A. Clarke, Citation2020; Mayne, Citation2016). However, group participation often seems to go well beyond technical support or physical craft activities, with the real value identified in the friendships formed and the support received, which may help participants cope with life’s challenges (Court, Citation2020; York et al., Citation2022). According to Nevay et al. (Citation2019) and Piercy and Cheek (Citation2004), needlecraft groups provide a safe space where participants can share deeply personal experiences. A participant in a knitting group stated that knitting is the “WD-40” in facilitating conversation (Court, Citation2020, p. 289). Needlecraft is instrumental in motivating people to leave their homes and interact with others (Emanuelsen et al., Citation2020; Kenning, Citation2015; Pöllänen & Voutilainen, Citation2018).

Theme 3: Sense of purpose, achievement, and satisfaction

Sense of purpose, achievement, and pride in the resulting handiwork

Almost all the included studies referred to the needlecrafters’ feeling of accomplishment both in the doing and in the completed item. Over 75% of the Burns and Van Der Meer (Citation2021) study participants stated they are motivated to crochet because of the resulting sense of accomplishment. Similarly, other needlecrafters have reported feeling a sense of purpose through their handiwork (Brooks et al., Citation2019; Mayne, Citation2016; Riley et al., Citation2013). Many believe the created item is a tangible and lasting expression of their skills and talents (Emanuelsen et al., Citation2020; Kenning, Citation2015; Reynolds, Citation2000). Nevay et al. (Citation2019) reported that even new needlecrafters are proud to show off their work, and the affirmation they receive from others makes them feel valued (Burt & Atkinson, Citation2012; Nevay et al., Citation2019).

Satisfaction through gifting and creating gifts

Thirteen studies referred to the satisfaction needlecrafters feel in gifting their handiwork. Participants reported feeling proud when recipients expressed joy and elation upon receiving and using the handmade items (N. A. Clarke, Citation2020; Emanuelsen et al., Citation2020). In the Rusiñol-Rodriguez et al. (Citation2020) study, participants felt it more meaningful to create an item for others than oneself. Needlecrafters expressed their regard for others through their handcrafted gifts (Kaipainen & Pöllänen, Citation2021; Pöllänen & Voutilainen, Citation2018; Wolk & Bat Or, Citation2023).

Sense of accomplishment through new learning

Studies suggest that needlecraft provides endless learning opportunities that some participants find most satisfying (Burns & Van Der Meer, Citation2021; Burt & Atkinson, Citation2012; Riley et al., Citation2013). Through needlecraft, participants may develop new ideas (Brooks et al., Citation2019; Sjöberg & Porko-Hudd, Citation2019) and are often stimulated by the many challenges (Kenning, Citation2015; Nevay et al., Citation2019). Although learning new skills can be frustrating (Brooks et al., Citation2019; N. A. Clarke, Citation2020; York et al., Citation2022), participants report feeling a great sense of achievement once the skill is mastered (N. A. Clarke, Citation2020; Kenning, Citation2015; Rusiñol-Rodriguez et al., Citation2020). Some participants in the Pöllänen and Voutilainen (Citation2018) study reported that learning new skills helped them channel their inner feelings, while knitters in the Riley et al. (Citation2013) study claimed that learning new skills helped their problem-solving ability. York et al. (Citation2022) hypothesized that learning new crochet stitches may have assisted participants in opening new pathways to learning and facilitated the discovery of new talents.

Theme 4: Identity, family, culture, and legacy

Self-identity, self-expression through creative work, and creating a legacy

Participants in many of the studies stated that needlecraft provides a sense of self-identity, allowing them to express themselves creatively. The various forms of needlecraft enabled participants to develop their unique personal creative style (N. A. Clarke, Citation2020; Kaipainen & Pöllänen, Citation2021), express themselves freely (Wolk & Bat Or, Citation2023), and may help them reclaim their identity as individuals rather than as mothers, wives, or employees (N. A. Clarke, Citation2020). According to Kaipainen and Pöllänen (Citation2021), each item produced symbolizes the creator’s lived experiences. For some participants in the Brooks et al.’s (Citation2019) study, needlecraft forms part of their daily routine, with one person stating, “losing the ability to knit would significantly impact one’s identity” (Brooks et al., Citation2019, p. 120). Burns and Van Der Meer (Citation2021) found that 82% of participants crochet for its creativity. Through their needlework, some participants state that they create memories, linking their handiwork with specific life events (Collier, Citation2011; Pöllänen & Voutilainen, Citation2018). Needlecraft gives participants a “voice” (Dickie, Citation2011, p. 213), allowing them to “leave a piece of themselves” in their work for the next generation (Piercy & Cheek, Citation2004, p. 28). Several studies refer to the creative item as a legacy (Kausch & Amer, Citation2007; Piercy & Cheek, Citation2004) or a “fingerprint” reflecting the values and character of the creator (Pöllänen & Voutilainen, Citation2018, p. 621).

A purposeful break

Needlecraft is identified as a versatile, portable hobby that can be done anywhere; on public transport, while waiting for an appointment, or while watching television (Clave-Brule et al., Citation2009; Dickie, Citation2011; Riley et al., Citation2013). It can be done alone or in groups (Brooks et al., Citation2019; N. A. Clarke, Citation2020; Dickie, Citation2011), and may require considerable concentration or minimal cognitive input (N. A. Clarke, Citation2020; Wolk & Bat Or, Citation2023). Many participants refer to needlecraft as a productive use of their time, resulting in a useful, functional end product (Burt & Atkinson, Citation2012). Some N. A. Clarke (Citation2020) and Pöllänen and Voutilainen (Citation2018) study participants said they felt guilty taking time away from their daily chores to sew but believed they were entitled to time away. Several studies discussed the importance of taking time from the daily routine to immerse oneself in needlecraft therapy (Collier, Citation2011; Piercy & Cheek, Citation2004; Sjöberg & Porko-Hudd, Citation2019).

Self-development, empowerment, self-confidence, and being in control

Some participants report feeling empowered by their creativity (Emanuelsen et al., Citation2020; Sjöberg & Porko-Hudd, Citation2019), gaining a sense of control (Brooks et al., Citation2019; Kaipainen & Pöllänen, Citation2021) and autonomy (N. A. Clarke, Citation2020; Reynolds, Citation2000). Needlecraft is an activity that most participants undertake for their enjoyment, and are usually free to decide what to create (Pöllänen & Voutilainen, Citation2018; Wolk & Bat Or, Citation2023). For some, needlecraft is a source of financial independence, providing a sense of self-worth as they contribute to the family’s financial security (Emanuelsen et al., Citation2020). However, some find that knitting for others is stressful, worrying about the quality of their work (Rusiñol-Rodriguez et al., Citation2020), while others report feeling anxious about what their peers will think of their work (Mayne, Citation2016).

Participants in the Pöllänen and Voutilainen (Citation2018) studies report that needlecraft provides “mental strength” (p. 634) and “independence” (p. 625), which serves as a cognitive counterbalance to their daily routine. Some believe that needlecraft is a strategy to avoid cognitive decline (Brooks et al., Citation2019), improve concentration, maintain memory, and reduce distractibility (Burns & Van Der Meer, Citation2021; Riley et al., Citation2013). Those who knit and crochet claim that it helps them concentrate during meetings and stay focused during conversations (Brooks et al., Citation2019; York et al., Citation2022). Riley et al. (Citation2013) believe needlecraft helps participants improve their visual and spatial awareness. Several studies report that needlecraft assists participants with their confidence and self-esteem (Burt & Atkinson, Citation2012; Gaspar da Silva, Citation2023; Rusiñol-Rodriguez et al., Citation2020), as it focuses on “strengths and abilities rather than disabilities” (N. A. Clarke, Citation2020, p. 133). Needlecraft can help to overcome self-doubt (Emanuelsen et al., Citation2020), facilitate personal growth (Kaipainen & Pöllänen, Citation2021) and self-determination to support life choices (Kenning, Citation2015).

Connection to family and cultural, past and future generations

Participants in 15 studies reported feeling close to their loved ones and connected to past and future generations through needlecraft. The skills are often passed from generation to generation (Emanuelsen et al., Citation2020; Kenning, Citation2015), helping to strengthen intergenerational relationships (Piercy & Cheek, Citation2004). In Inuit society, the older generation is admired for their needlecraft skills and serves to inspire the younger generation (Emanuelsen et al., Citation2020). According to Mayne (Citation2016), replicating old family patterns evoked nostalgia in the younger generation, connecting them to the previous generations. Many feel part of a culture of needlecrafters, which provides them with an interconnected group identity (Brooks et al., Citation2019; Kaipainen & Pöllänen, Citation2021; Wolk & Bat Or, Citation2023). Others identify with their ethnic culture, lores and traditions through needlecraft (Emanuelsen et al., Citation2020; Gaspar da Silva, Citation2023; Piercy & Cheek, Citation2004), and some state that their craft is an “echo of female solidarity” (Court, Citation2020, p. 287).

Discussion

This review synthesized and mapped the research literature on the impact of needlecraft, in its many iterations, on mental health and well-being. All the included studies supported the notion that needlecraft benefits the participants’ well-being. Although the benefits reside both in the process and the end product, the social aspect of needlecraft makes this activity particularly valuable. Almost all the included studies addressed the social benefits of needlecraft. The act of creating a textile item is usually solitary but often done in groups, or the end product is gifted to others, making needlecraft a social activity (Brooks et al., Citation2019; Corkhill et al., Citation2014). Some studies have found that it is not about the end product; needlecraft is simply the conduit that brings people together (Corkhill et al., Citation2014). It is a common language that unites like-minded people who may have little in common other than their love for needlecraft (Mayne, Citation2016). This connection is particularly important for mental health and well-being, particularly for individuals with low social confidence who can use the common language of needlecraft to connect with others (Corkhill et al., Citation2014). Working in groups can encourage interaction and close contact, which is missing in the lives of many and is important in mental well-being (Corkhill et al., Citation2014). Participation in needlecraft groups is also an opportunity to share skills and ideas, and feel part of a community (Brooks et al., Citation2019). While learning new skills may be challenging, it is stimulating, leaving participants with a sense of mastery, empowerment and renewed confidence (Corkhill et al., Citation2014; Hanania, Citation2020). Many needlecrafters feel a sense of group identity through their common hobby, and some believe they would be lost without their needlecraft (Brooks et al., Citation2019). Since humans are social beings, group identity and belonging are important in maintaining mental health and well-being (Inoue et al., Citation2020).

It is apparent from the included studies that needlecraft is popular amongst mature-aged women. However, there appears to be a growing community of young online needlecrafters who develop strong, supportive virtual networks (N. A. Clarke, Citation2020; Mayne, Citation2016; Pöllänen & Voutilainen, Citation2018; Riley et al., Citation2013). The social connection, be it virtual or physical, provides a sense of belonging and purpose (Kenning, Citation2015; Mayne, Citation2016) but goes beyond the craft itself; participants help each other deal with everyday worries, including during times of crisis (Dickie, Citation2011). According to N. A. Clarke (Citation2020), needlecraft contributes to healthy aging, providing older people with social support and a sense of accomplishment. This is important since loneliness, social isolation, and depression are common mental health problems in older people (Bone et al., Citation2022; Corkhill et al., Citation2014). Needlecraft requires bilateral coordination, engaging more brain function than unilateral activities (Corkhill et al., Citation2014). It may be beneficial in maintaining cognitive function, especially with advancing age (Burns & Van Der Meer, Citation2021; Burt & Atkinson, Citation2012). Needlecraft provides participants, including older people, with a sense of community purpose through gifting their needlework and passing their skills to others (Cheek & Yaure, Citation2017; Emanuelsen et al., Citation2020; Piercy & Cheek, Citation2004).

The therapeutic properties of needlecraft are well documented and have been used to overcome compassion fatigue in nurses (Anderson & Gustavson, Citation2016), depression in the elderly (Bone et al., Citation2022; Corkhill et al., Citation2014), and to promote problem-solving in people with dementia (Gjernes, Citation2017). The act of ‘making’ has been described as calming, relaxing and rejuvenating (Corkhill et al., Citation2014). It is a diversion, a means of escaping life’s worries (Wolk & Bat Or, Citation2023), but it also provides space to think and problem-solve (Pöllänen & Voutilainen, Citation2018). Many studies report that the repetitive rhythmic motion of needlework is meditative, resulting in a calming Zen-like state (Burt & Atkinson, Citation2012; Reynolds, Citation2000). The repetitive motion of needlecraft is thought to release serotonin, which is therapeutic in dealing with fatigue, depression, and anxiety and is calming during challenging times (Kumar, Citation2021). Participants speak of the esthetics, color and texture of the yarn and fabric, uplifting and echoing the crafter’s unique character (Brooks et al., Citation2019; Nevay et al., Citation2019).

The end product validates the creativity and skill of the crafter N. A. Clarke (Citation2020), resulting in a sense of great pride and accomplishment (Burns & Van Der Meer, Citation2021). Creativity is thought to be linked with psychological flexibility and the ability to self-manage, promoting well-being (Corkhill et al., Citation2014). Needlecraft gives voice to the crafter with a tangible item that others can admire in perpetuity (Bookbinder, Citation2016; Hanania, Citation2020). The handiwork is often an expression of the creator’s personality and may reflect their love for the recipient of the item (Pöllänen & Voutilainen, Citation2018). Some crafters convey a message through their work, viewing the item as an enduring memory that outlives the event it represents (Cheek & Yaure, Citation2017; Kausch & Amer, Citation2007). Others speak of the legacy they leave through their handiwork (Bookbinder, Citation2016; Piercy & Cheek, Citation2004), building relationships and strengthening ties between generations (Bookbinder, Citation2016; Burns & Van Der Meer, Citation2021).

The importance of mental health and well-being is internationally recognized, and to our knowledge, this paper is the first scoping review addressing the impact of needlecraft on well-being. We included studies from across the world, representing large cultural variations and diverse methodologies. Our review took a broad view of mental health and did not focus on specific disorders or conditions. We included a range of factors that may contribute to well-being, such as developing strong social networks, having a sense of purpose and achievement in life, and self-identity and being valued by family, friends, and the community. Given the generality of our study, our results may find application in healthcare, such as addressing compassion fatigue in nursing, peer support groups, addressing isolation and alienation and encouraging friendships.

Our review has several limitations; most studies included in our review may hold biases because they recruited participants who enjoy needlework, and most participants were female, indicating a gender bias. Given that our search terms included variations of needlecraft and mental health, many of the included studies aimed to ascertain well-being outcomes which may have contributed to a circular argument bias in our review. Also, our review did not include all textile crafts; the included studies had variable sample sizes, we limited the search to English language publications and did not draw comparisons between the different textile crafts. Additionally, some studies may have been missed due to search terms. Since this is a scoping review, the quality of the included studies was not assessed. Most of the existing literature focuses on mature-aged needle crafters. There is limited information on the prevalence of needlecraft among the younger generations and what attracts them to needlecraft. A recent survey of over 140 countries reported that a quarter of the world’s population disclosed feeling lonely (Maese, Citation2023), with adolescents and young people reporting the highest level of disconnection (Ending Loneliness Together, Citation2023). Involvement in needlecraft may provide an opportunity for young people to reconnect with their community. This warrants further study. Furthermore, this scoping review has revealed the therapeutic benefits of needlecraft amongst people with mental health disorders and those in marginalized groups. This also merits further research.

This scoping review has provided evidence of the benefits of needlecraft for mental health and well-being. Both the physical act of creating a unique item and the item itself provide needlecrafters a sense of purpose and achievement, thereby supporting mental health and well-being. More importantly, needlecraft is a conduit for social interaction and support, providing a sense of identity and belonging. The item created is a legacy of the needlecrafter’s skill, an expression of one’s love for the intended recipient, and an intergenerational bond.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: MC, RK, DLL. Systematic search: RK, MC. Screening: MC, RK, DLL. Data charting: DLL, MC, RK. Data analysis and interpretation: DLL, MC, RK, CJD. Data checking: DLL, MC, RK Draft writing: DLL, MC, RK, CJD. Review of drafts: All authors. Approval: All authors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, L. W., & Gustavson, C. U. (2016). The impact of a knitting intervention on compassion fatigue in oncology nurses. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 20(1), 102–104. https://doi.org/10.1188/16.CJON.102-104

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Bone, J. K., Bu, F., Fluharty, M. E., Paul, E., Sonke, J. K., & Fancourt, D. (2022). Engagement in leisure activities and depression in older adults in the United States: Longitudinal evidence from the Health and Retirement Study. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 294, 114703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114703

- Bookbinder, S. (2016). Fusion of a community using art therapy in long-term care [La fusion d‘une communauté grâce à l‘art-thérapie en soins de longue durée]. Canadian Art Therapy Association Journal, 29(2), 85–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/08322473.2016.1239186

- Bowman, C., & Lim, W. M. (2023). The secrets to aging well: Animal interactions, social connections, volunteerism, and more. Activities, Adaptation, & Aging, 47(2), 107–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2023.2207282

- Brooks, L., Ta, K. N., Townsend, A. F., & Backman, C. L. (2019). “I just love it”: Avid knitters describe health and well-being through occupation. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 86(2), 114–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417419831401

- Burns, P., & Van Der Meer, R. (2021). Happy Hookers: Findings from an international study exploring the effects of crochet on wellbeing. Perspectives in Public Health, 141(3), 149–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913920911961

- Burt, E. L., & Atkinson, J. (2012). The relationship between quilting and wellbeing. Journal of Public Health, 34(1), 54–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdr041

- Cheek, C., & Yaure, R. G. (2017). Quilting as a generative activity: Studying those who make quilts for wounded service members. Journal of Women & Aging, 29(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952841.2015.1021652

- Clarke, N. A. (2020). Exploring the role of sewing as a leisure activity for those aged 40 years and under. Textile, 18(2), 118–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759756.2019.1613948

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 297–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613

- Clave-Brule, M., Mazloum, A., Park, R. J., Harbottle, E. J., Birmingham, C. L., Clave-Brule, M., Mazloum, A., Park, R. J., Harbottle, E. J., & Birmingham, C. L. (2009). Managing anxiety in eating disorders with knitting. Eating and Weight Disorders, 14(1), e1–e5. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03354620

- Collier, A. F. (2011). The well-being of women who create with textiles: Implications for art therapy. Art Therapy, 28(3), 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2011.597025

- Corkhill, B., Hemmings, J., Maddock, A., & Riley, J. (2014). Knitting and well-being. Textile, 12(1), 34–57. https://doi.org/10.2752/175183514x13916051793433

- Court, K. (2020). Knitting two together (K2tog), “If you meet another knitter you always have a friend”. Textile, 18(3), 278–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759756.2019.1690838

- Dickie, V. A. (2011). Experiencing therapy through doing: Making quilts. OTJR: Occupation, Participation & Health, 31(4), 209–215. https://doi.org/10.3928/15394492-20101222-02

- Emanuelsen, K., Pearce, T., Oakes, J., Harper, S. L., & Ford, J. D. (2020). Sewing and Inuit women’s health in the Canadian Arctic. Social Science & Medicine, 265, 113523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113523

- Ending Loneliness Together. (2023). State of the nation report. Social connection in Australia 2023. Ending Loneliness Together. https://ncq.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023-Loneliness-Awareness_State-of-the-Nation-Report.pdf

- Gaspar da Silva, M. (2023). Storytelling embroidery art therapy group with Portuguese-speaking immigrant women in Canada [Groupe d’art-thérapie de récit par la broderie avec des femmes immigrantes lusophones au Canada]. Canadian Journal of Art Therapy, 36(2), 86–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/26907240.2022.2160546

- Gilligan, I. (2010). The prehistoric development of clothing: Archaeological implications of a thermal model. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 17(1), 15–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-009-9076-x

- Gjernes, T. (2017). Knitters in a day center: The significance of social participation for people with mild to moderate dementia. Qualitative Health Research, 27(14), 2233–2243. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732317723890

- Hanania, A. (2020). Embroidery (Tatriz) and Syrian refugees: Exploring loss and hope through storytelling [Broderie [tatriz] et réfugiées syriennes: Exploration de la perte et de l‘espoir à travers le récit]. Canadian Art Therapy Association Journal, 33(2), 62–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/26907240.2020.1844416

- Inoue, Y., Wann, D. L., Lock, D., Sato, M., Moore, C., & Funk, D. C. (2020). Enhancing older adults’ sense of belonging and subjective well-being through sport game attendance, team identification, and emotional support. Journal of Aging and Health, 32(7-8), 530–542. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264319835654

- Kaipainen, M., & Pöllänen, S. (2021). Garment sewing as a leisure craft. Techne Series A, 28(1), 1–15. https://journals.oslomet.no/index.php/techneA/article/view/4021

- Kargól, M. (2022). Knitting as a remedy: Women’s everyday creativity in response to hopelessness and despair. Cultural Studies, 36(5), 821–839. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2021.2011933

- Kausch, K. D., & Amer, K. (2007). Self-transcendence and depression among AIDS memorial quilt panel makers. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 45(6), 44–53. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20070601-10

- Kenning, G. (2015). “Fiddling with threads”: Craft-based textile activities and positive well-being. Textile: The Journal of Cloth and Culture, 13(1), 50–65. https://doi.org/10.2752/175183515x14235680035304

- Kumar, S. (2021). Fostering mindfulness through embroidery and reverse community engaged learning in higher education. Journal of Contemplative Inquiry, 8(1), 48–72. https://digscholarship.unco.edu/joci/vol8/iss1/11

- Kwak, S., Kim, S. Y., Bae, D., Hwang, W. J., Cho, K. I. K., Lim, K. O., Park, H. Y., Lee, T. Y., & Kwon, J. S. (2019). Enhanced attentional network by short-term intensive meditation. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 3073. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03073

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H.,& O'brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Maese, E. (2023, October 24). Almost a quarter of the world feels lonely. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/opinion/gallup/512618/almost-quarter-world-feels-lonely.aspx

- Maita, S. (2018). Effect of hook/knitting activities against decreased stress levels in Class II-a Medan women’s laps. Science Midwifery, 7, 11–14. https://midwifery.iocspublisher.org/index.php/midwifery/article/view/12

- Mansfield, L., Daykin, N., & Kay, T. (2020). Leisure and wellbeing. Leisure Studies, 39(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2020.1713195

- Mayne, A. (2016). Feeling lonely, feeling connected: Amateur knit and crochet makers online. Craft Research, 7(1), 11–29. https://doi.org/10.1386/crre.7.1.11_1

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143–143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- Nevay, S., Robertson, L., Lim, C. S., & Moncur, W. (2019). Crafting textile connections: A mixed-methods approach to explore traditional and e-textile crafting for wellbeing. The Design Journal, 22(sup1), 487–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2019.1595434

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71–n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Piercy, K. W., & Cheek, C. (2004). Tending and befriending: The intertwined relationships of quilters. Journal of Women & Aging, 16(1-2), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1300/J074v16n01_03

- Pöllänen, S., & Voutilainen, L. (2018). Crafting well-being: Meanings and intentions of stay-at-home mothers’ craft-based leisure activity. Leisure Sciences, 40(6), 617–633. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2017.1325801

- Pollock, A., & Berge, E. (2018). How to do a systematic review. International Journal of Stroke, 13(2), 138–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747493017743796

- Reynolds, F. (2000). Managing depression through needlecraft creative activities: A qualitative study. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 27(2), 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-4556(99)00033-7

- Riley, J., Corkhill, B., & Morris, C. (2013). The benefits of knitting for personal and social wellbeing in adulthood: Findings from an international survey. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 76(2), 50–57. https://doi.org/10.4276/030802213X13603244419077

- Rusiñol-Rodriguez, J., Rodriguez-Bailon, M., Ramon-Aribau, A., Torra, M. l T., & Miralles, P. M. (2020). Knitting with and for others: Repercussions on motivation. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 40(3), 203–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887302X20969867

- Scott, K., & Williams, E. N. (2024). Art therapy with adult refugees: A systematic review of qualitative research. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 88, 102126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2024.102126

- Sjöberg, B., & Porko-Hudd, M. (2019). A life tangled in yarns–Leisure knitting for well-being. Techne serien - Forskning i slöjdpedagogik och slöjdvetenskap, 26(2), 49–66. https://journals.oslomet.no/index.php/techneA/article/view/3405

- Takiguchi, Y., Matsui, M., Kikutani, M., & Ebina, K. (2023). The relationship between leisure activities and mental health: The impact of resilience and COVID‐19. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 15(1), 133–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12394

- Thompson, E. (2022). Labour of love: Garment sewing, gender, and domesticity. Women’s Studies International Forum, 90, 102561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2022.102561

- Verdejo, C., Tapia-Benavente, L., Schuller-Martínez, B., Vergara-Merino, L., Vargas-Peirano, M., & Silva-Dreyer, A. M. (2021). What you need to know about scoping reviews. Medwave, 21(2), e8144-e8144–e8144. https://doi.org/10.5867/medwave.2021.02.8144

- Wolk, N., & Bat Or, M. (2023). The therapeutic aspects of embroidery in art therapy from the perspective of adolescent girls in a post-hospitalization boarding school. Children, 10(6), 1084. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061084

- York, P., Zhang, S., Yang, M., & Muthukumar, V. (2022). Crochet: Engaging secondary school girls in art for STEAM's sake. Science Education International, 33(4), 392–399. https://doi.org/10.33828/sei.v33.i4.6

- Yuwen, C. J., Miura, I., Nagamori, Y., Khankeh, H., Ward, K., Vázquez-Mena, A., Lee, M., & Chiu de Vázquez, C. (2021). Posttraumatic growth, health-related quality of life and subjective happiness among Great East Japan Earthquake survivors attending a community knitting program to perform acts of kindness. Community Psychology in Global Perspective, 7(2), 39–59. https://doi.org/10.1285/i24212113v7i2p39