ABSTRACT

Hospital to home transfers for older people require effective communication, coordination and collaboration across multiple service settings. Rural Nursing Theory and the Beyond Periphery model explain why this is particularly difficult in rural areas, but there are few examples of how rural services respond. This paper presents a case study of the district of Tärnaby in the inland north of Sweden. Data are drawn from interviews with health and care staff in Tärnaby, observations, and experiences of the researchers. Data were analyzed thematically, with four main themes emerging – role clarity, communication, geography, and understanding of the rural context. Responses to challenges included increasing opportunities for communication between service providers and improving documentation. The paper concludes that informal “workarounds” run the risk of further disconnecting rural service settings from “the city”. Rather, the aim needs to be to improve contextual understanding through formally incorporating “the rural” in service design.

Introduction

Hospital to home transfers (HHT) for older people are difficult because they require effective communication, coordination and collaboration (CCC) between multiple actors in multiple service settings (Hilborn & Singh, Citation2022). In rural areas, the challenges are likely to be even greater because of the distances across which CCC must occur, and because of the distinguishing characteristics of “the rural” when it comes to the provision of care services (Lee and McDonagh, Citation2022, Strasser, Citation2016). There is generally poor understanding of how rurality impacts the experience of transitions in care for older people (Poulin & Skinner, Citation2022), and a lack of nuanced understanding of the experiences in different kinds of rural settings (Jakobs, 2021). The purpose of this research is to explore the multiple layers of CCC in HHT in a specific rural setting (the district of Tärnaby in the inland north of Sweden). The research examines how service providers manage, or could manage, CCC to lower risk and deliver patient-centered HHT, which, if not always “perfect,” has reliably “good” outcomes for all actors involved.

While there are substantial difficulties (discussed later in the paper) in assessing whether Tärnaby currently has good or poor HHT outcomes from a statistical perspective, it is important to note that there is no immediate perceived crisis in HHT in Tärnaby. Rather, there is a desire to reduce the risk of poor health outcomes, hospital readmissions and avoidable expense. The research makes a contribution by describing the strengths and weaknesses of current (mostly informal) approaches to managing the challenges of HHT and proposing more formal responses. It contributes to research practice where, in Sweden at least, sub-municipal studies, and studies in this particular type of rural context are rare (Eimermann, Adjei, Bjarnason, & Lundmark, Citation2022) and so the complexity of intra-municipal CCC is often overlooked. And it contributes theoretically through linking Rural Nursing Theory and the Beyond Periphery model to provide a more nuanced understanding of how rurality impacts care provision.

The paper proceeds as follows: firstly, the relevance of Rural Nursing Theory and the Beyond Periphery model of rurality to hospital to home transfers in places like Tärnaby is discussed. The paper then reviews literature on HHT in rural areas somewhat similar to Tärnaby, identifying both challenges to “good” HHT and proposed solutions to those challenges. The research is then described as a case study involving interviews with 10 health and care staff based in Tärnaby, two periods each of two weeks’ field observation and experience drawn from working with the municipal care department (author 1) and the regional health service in Tärnaby (author 3). Results are presented thematically, and the Discussion and Conclusion explore the implications of the research for practice and theory.

Theory and literature

HHT is difficult in any geographic context because it relies upon CCC between a range of actors often working within different sectors and with patients and their families and informal carers (Hilborn & Singh, Citation2022). The “8Ds” or “Beyond Periphery” model of rurality (in bold below), specifically designed to investigate characteristics of small rural and remote areas, helps explain why HHT is even more challenging in places like Tärnaby (Carson, Carson, & Lundmark, Citation2014; Strasser, Citation2016). Despite having small populations, rural areas are diverse and demographic, economic and social conditions are dynamic – they change rapidly, and often due to the behavior of just one or two people (detailed). The presence or absence of one individual in the HHT process, for example, can dramatically change how HHT works and the knowledge and skills available (Dellasega & Fisher, Citation2001). Social and economic conditions in small rural areas are often delicate, with rural residents and service providers reluctant to draw attention to perceived weaknesses for fear of interference from “outsiders” on whose resources they are often dependent. In health, this often means rural residents are reluctant to seek care until it is absolutely necessary, leading to poorer health status and increases in hospital admissions and re-admissions (Hardman & Newcomb, Citation2016). It is well known that what works in one rural setting may not work in another (Harrington et al., Citation2020), and this is often because even proximate rural communities have very different social, cultural, political and economic backgrounds as a result of discontiguous development, making it difficult to translate institutions or initiatives from one to another. Perhaps the most commonly cited distinguishing features of small rural areas are their distance to and consequently disconnectedness from the urban institutions which by and large make policy and determine how services should be delivered and evaluated (Strasser, Citation2016). While distance is a given, the Beyond Periphery model argues that small rural places can become more distant over time as increasing specialization and service costs concentrate resources in larger urban centers (Carson & Cleary, Citation2010).

Conceptually, this research links the Beyond Periphery model to the insights provided by Rural Nursing Theory (see ) (Jakobs, Citation2022). While RNT has most often been applied specifically in the context of nursing as a profession, it has relevance for the practice of patient-centered care (nursing as an activity) generally.

Table 1. Linking Rural Nursing Theory (RNT) and the beyond periphery model.

For the most part, RNT presents care work in rural areas as challenging, perhaps because rural work aligns poorly with experiences in formal education and training of health and care workers (McConnel, Demos, & Carson, Citation2011). However, the observations of RNT also present as paradoxes, where they can simultaneously hinder and help effective delivery of care. For example, lack of anonymity, re-interpreted as close relationships between care workers and residents, can help break through communication barriers caused by the different perspectives on “health” between residents and service providers (Swan & Hobbs, Citation2017). High self-reliance can lead to greater health literacy among rural residents who take responsibility for their own care treatment (Ohta, Ryu, Kitayuguchi, Gomi, & Katsube, Citation2020).

Strategies for improvement

A structured review of the scientific literature on “rural hospital to home transfer” revealed very few concrete examples of how to manage this complexity and reduce risk. The review was conducted using EbscoHost with keywords “rural” (and variations such as “country”), “case study” (and variations) and “hospital to home transfers” (and variations such as “transitions”), Forty-six articles matched the initial search, and these were manually screened by all three authors to confirm that the setting was “small rural” (Carson, Preston, & Hurtig, Citation2022) and that there were concrete suggestions for improving hospital to home transfers. Eight papers ultimately matched the criteria, and these are cited in this section of the paper.

In the literature generally (the 46 initial papers), there were broad calls for “better communication” and “increased patient-centredness”, but few concrete insights into how to achieve these goals. The most common suggestion was the implementation of some sort of case management or care coordination model, either through attaching responsibility to a single person (the case manager or care coordinator) or through reorganization of work – where inter-organizational (and multi-locational) teams would be constituted for each patient (Hogan et al., Citation2018). Care coordination could be led by a health professional (most often a nurse), but might also be something that could be undertaken by a nonprofessional or lay worker (Kitzman, Hudson, Sylvia, Feltner, & Lovins, Citation2017) especially where there are nursing shortages.

Fahlberg (Citation2017) among others called for better use of digital technologies, and particularly the interoperability of digital systems across space and organizational boundaries to improve communication, coordination and collaboration. In Sweden, the Prator system has been developed to help different actors in the care process (within and across organizations) communicate with each other by sharing case notes and identifying tasks that need to be done (Christiansen, Fagerström, & Nilsson, Citation2017). It is unclear from Christiansen and colleagues’ research how well suited Prator is to complex and rural contexts such as Tärnaby.

The literature reveals strong theoretical (Beyond Periphery and RNT) and experiential (through the literature review) explanations for the challenges facing HHT in a context like Tärnaby. From a challenges perspective, one might expect increased reluctance to seek care (Ohta, Ryu, Kitayuguchi, Gomi, & Katsube, Citation2020), a persistent feeling of “crisis” within the system (Congdon & Magilvy, Citation2001), a loss of patient-centredness (Poulin & Skinner, Citation2022) and stress and low work satisfaction among health care workers (Dussault & Franceschini, Citation2006). However, at least in rural Sweden, it appears that most HHT experiences are good (Nyhlen & Giritli-Nygren, Citation2016), so there must be adaptations to the context that are not currently well described in the literature. Whether these adaptations are case specific or generalizable, ad hoc or entrenched, temporary or sustainable, and how these adaptations might inform new formal procedures for HHT is unknown.

Methods

Case selection

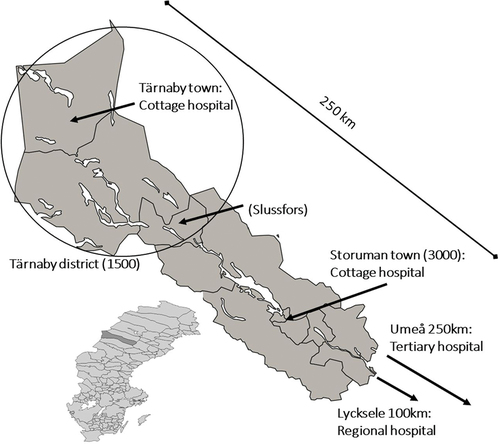

The municipality of Storuman in the inland north of Sweden covers a land area of about 8300 km2 and has a population of just over 5500 residents (see ). About 20% of residents are aged 70 years or older. The Municipality is responsible for non-medical care services, including aged care. In practice, this means providing in-home care services, managing several residential care facilities targeting people needing 24/7 nursing care, and providing short term accommodation for people transitioning between sites of care, including between hospital and home. The province of Västerbotten is responsible for medical care, and operates two primary care facilities (sjukstuga or cottage hospital) in the municipality, a small regional hospital in the city of Lycksele and a tertiary and teaching hospital in the capital city of Umeå. The Municipality organizes aged care services within two districts (which are further divided for home care services). The largest is the Storuman district which is based around the municipal center of Storuman. The Tärnaby district is based around the mountain villages of Tärnaby (where there is a sjukstuga) and Hemavan, which are about 150 km west of Storuman town. Services in the Tärnaby district may also cater to people living in (particularly western parts of) the Slussfors area (otherwise serviced via Storuman town). The hospital in Lycksele is about 250 km by road from Tärnaby town, and Umeå is approximately 400 km distant. The Tärnaby district and Slussfors combined have a population of just over 1500 residents.

Figure 1. Municipality of Storuman, showing Tärnaby district and distances to main health services (created by authors).

Tärnaby represents a particular type of geography which has been labeled by Carson, Preston, and Hurtig (Citation2022) as “small rural.” The population within the Tärnaby care district, and even within the entire municipality of Storuman would normally be considered insufficient to sustain a “standard” primary care service (with estimates of this threshold varying from 7–12 000) (Scott et al., Citation2013). However, the distance to any service center that does meet the threshold (even Lycksele city has fewer than 10 000 residents) is so great that some localized models of care are required.

Case definition

HHT services for Tärnaby residents are complex spatially, organizationally and temporally. “Hospital” can involve any mix of time spent locally (at the Tärnaby cottage hospital), nearby (at the Storuman town cottage hospital), or in the more distant facilities in Lycksele and Umeå. While in Storuman municipality, the patient may be interacting with service providers employed by the province or the municipality, while the municipality is largely absent from service provision in Lycksele and Umeå. In Lycksele and (especially) Umeå, the patient has access to a wide range of health professionals, who operate in departments specific to their disciplines. In Tärnaby and Storuman, the province is responsible for medical care meaning direct treatment of an illness or injury. A range of professions may be involved in this, but not all will be available locally, and some may be sourced (including via digital technologies) from Lycksele and Umeå. The municipality is responsible for care after the province has decided there is no need for hospitalization. Most care staff in the municipality are nonprofessional, but there is a small team of nurses, physical and occupational therapists, social workers and perhaps other specialties (dieticians, nutritionists, speech therapists, mental health professionals) depending on staffing conditions. Municipal staff are separated into three organizational units – home care, residential care and clinical care (which works across both settings).

The HHT process is complex, involving discharge from the distant hospital, transport (4 or 6 hours direct by road) to Tärnaby (sometimes Storuman town), assessment locally by provincial and municipal staff, physical return to home (assisted by informal carers or municipal staff) and follow-up assessment in the home. At each point, different orders may be made for care regimes, house modifications (installing accessibility devices, for example), and ongoing medical appointments. At each point, there is a possibility that the transfer will be stopped and the patient returned to the distant hospital, or hospitalized locally (under either municipal or provincial care), or encouraged to move to residential care. The outcomes are dependent on the patient’s physical and psychological status, access to informal care, quality of housing, the availability of health professions (which can change rapidly due to staff turnover) and beds in various facilities, and, of course, the level of CCC between all these actors in all these places across the entire journey.

Not surprisingly, the fragility of the HHT process presents risks to good outcomes for patients and staff. Patient and staff experiences can vary greatly across even a small number of HHT events, and the conditions for good HHT can change almost on a day to day basis.

Sources of data

The principal source of data for this research was 10 semi-structured interviews with provincial (6) and municipal (4) health and care staff based in Tärnaby and regularly involved in HHT. The interviews were conducted during a two week fieldwork visit to the Tärnaby cottage hospital (Authors 2 and 3), and field observations from this fieldwork were used to validate data drawn from the interviews. In addition, Authors 1 (municipality) and 3 (province) were employed in health and care roles involving contact with actors involved in HHT in Tärnaby, and Author 2 was employed by the province in another rural location, and had experience of HHT in that location. Authors 2 and 3 also spent an additional 2 weeks observing municipal health and care services in Storuman prior to the fieldwork and interviews. Observational data were recorded through note taking by the three authors for a period of four months from when the study was first announced to health and care staff in Tärnaby until data analysis was completed.

Interviews were held in late May 2022 following presentations and an information sheet being made available to health and care staff in Tärnaby. A small number of participants were directly approached to be interviewed due to their formal roles in HHT, while most were self-recruited through informal discussions with the researchers or were recommended as participants by previous interviewees. Most interviews were conducted “in pieces” to fit in with participants’ work schedules. So a single interview might have involved 3 or 4 periods of interaction during breaks in work.

Each interview commenced by asking the participant what they thought constituted a “good” HHT, and how good HHT was facilitated or hindered in their workplace. Participants were typically asked “what should be done to make a good HHT,” “how should it be done,” and who should be responsible for getting it done’? However, as far as possible, participants led the discussions and were not constrained by these three questions. The researchers took notes during the interview. At the end of the interview, a summary of key points raised was made with the participant, which sometimes led to further discussion and elucidation of key points. At the end of the day, Authors 2 and 3 made a joint summary of each interview and how each interview linked to observations the authors had made during their fieldwork and their lived experience outside of the fieldwork period. At the end of the fieldwork, a higher level summary of findings was made with Author 1 (who was not privy to the identities of participants).

In addition to quotes from interviews and descriptions of field observations, the Results include two “anecdotes”, which are extended stories illustrating the challenges arising from a lack of shared understanding of the rural context. The anecdotes arise from examples of frustrations which were repeated by multiple participants and which were elaborated in observed informal discussions between staff and researchers throughout the course of the fieldwork.

Analysis

Thematic synthesis (following Thomas & Harden, Citation2008) was used to analyze the data. The process involved initially “line-by-line” coding of quotes and notes, grouped then into descriptive themes (such as “being able to do your job correctly”) which were then grouped into analytic themes (“being resourced to do your job”), which were ultimately combined into the four thematic “headlines” used in reporting the Results below (an example is presented in ). Where there are direct quotes from participants, they are identified as Participant A – J.

Table 2. Example of analysis for “role clarity” theme.

Ethical considerations

Three key ethical considerations underpinned the research process. The first was ensuring that no HHT patients could be identified. Interviewees were asked not to name patients, patient names were not used in any notes taken during observation, and where patient experiences are reported in this paper, they are presented as generalized experiences, rather than specific cases. The second ethical consideration was maintaining, as best as possible, the anonymity of interviewees. In small workplaces like those in Tärnaby, it is not possible to protect the identity of participants in a study, and participants in this study were warned that their colleagues would most likely know they had been interviewed. No personal information was recorded about participants, and no breakdown of participant characteristics (age, role) is given in this paper except to say that all participants were female, and we were unable, because of staffing conditions, to interview any social workers. Finally, the position of Author 3 as a “true insider” required some attention to maintaining professional and private boundaries between researcher and participants (Heslop, Burns, & Lobo, Citation2018), and recognizing the bias of the insider-researcher. At the same time, the insider perspective is of course invaluable to understanding the deeper meanings of what is heard or seen (McDermid, Peters, Jackson, & Daly, Citation2014). In this study, insider knowledge was both privileged and questioned in data collection and analysis, with daily meetings between the researchers doing the fieldwork, regular meetings with all three researchers, and the “outsider” (Author 2) being the lead interviewer where there was a perceived risk of relationship management.

Results

Overview

Participants emphasized themes relating to: role clarity; communication; geography; and understanding of the rural context by actors particularly by based in Lycksele and Umeå. However, CCC challenges were not confined to relationships between local and distant actors, or between municipal and regional staff. There were also difficulties within each service in Tärnaby itself (role clarity and communication, for example, between lay and professional staff, for example), and between staff geographically located in Tärnaby and in Storuman town (whether employed by the municipality or the province). Despite this, participants universally claimed that HHT was generally well managed and few people “fell between the chairs” (Participant I) because the small size of the local workforce enabled people to respond to challenges on a case by case basis, and there were almost always preexisting relationships between patients and their families and staff involved in HHT that allowed individual circumstances to be catered for. However, it was recognized that relying on case-by-case reactive management (“workarounds”) is risky, and fails to address the underlying structural weaknesses in the system-

If we don’t have routines, the continuity will be lost (Participant B)

Role clarity

Many people probably feel that the discharge process is a bit unclear (Participant C)

Role clarity is often difficult to achieve in small environments like Tärnaby where one person may fill a number of roles, there may be no individual with the necessary skills available when needed, and where locally framed roles like team leader or case manager are versatile and broad in scope. It was often difficult for participants to know exactly what their role would be in the next HHT, as well as to understand other people’s roles and responsibilities. While HHT would likely work better if

Everyone takes responsibility for their area; everyone sees their responsibility. (Participant D),

this continued to be difficult to achieve in a context where an individual’s role (or roles) could change from case to case.

A workaround for this challenge was to rely heavily on those few staff with extensive experience in local HHT and good connections with municipal and provincial services.

It is noticeable when someone is in the know. (Participant G)

This risks over-burdening these few people, and doesn’t work well when experienced staff are absent for whatever reason. Another workaround was to try and limit the size of the teams involved in HHT, actually encouraging people to assume multiple roles, and to step outside the roles they have been specifically trained for.

It is easier when few people are involved. (Participant E)

This does allow for better communication and faster decision making, but it also risks excluding knowledges, skills or roles that are important for good HHT. One concrete example is in meal preparation where including input from dieticians or nutritionists would make the process more time consuming and costly than relying on historical precedent. However, people working outside their recognized roles often experienced a sense of lack of control as they were unable – legally, or because of professional boundaries or strict routines existing in the parent organizations – to make promises about what would be done for the patient, or to follow up when things that had been promised were not delivered. In a context where roles are sometimes unclear and reactive management is the norm, it is difficult to ensure accountability.

Addressing the challenge of role clarity would begin with better documentation or guidelines for how to conduct HHT that reflect awareness of the Tärnaby context – allocating roles and responsibilities to those with the capacity to undertake them, and providing points of connection between municipal and regional, and local and distant staff. Case meetings involving municipal and provincial staff were recommended

I like the idea of having regular meetings between us (provincial nurses), the nursing homes and home care – it doesn’t have to be often …since we have the same patients. (Participant E – emphasis added)

Ultimately, any attempts to improve role clarity would need to involve home care units (largely consisting of lay workers) in ways that have not been done in the past. The home care team has tried to improve accountability by assigning a “contact person” (essentially a case manager) for each home care client, but other actors either did not know that this was done, or did not think it was a home care responsibility, and lists of contact people quickly become out of date due to high staff turnover and absences. Nevertheless, there was some support for the idea of case management like this.

Communication

The Prator system was designed to improve communication between provincial and municipal service providers, but it is not seen as a particularly important source of information by many of the participants in this study. Prator’s effectiveness was limited because not all actors could access the system (home care staff in particular), not all information was available to everyone who could access the system, and there was a perception that entering data into Prator was time wasting when the person looking for that information was physically in the same office or workspace, or when the person entering the information acted in multiple roles – meaning they were entering information that would then be delivered to themselves (situations rarely faced in larger work environments and not catered for in Prator’s design). Consequently, study participants were at best ambivalent about how better use of Prator could improve communication flows. Generally, participants could see the potential of Prator

IF you use it the way it’s supposed to be used. (Participant A)

Prator isn’t a dangerous system so there is no need to be afraid of using it. (Participant D)

Most participants said they had not had a good introduction to how to use Prator, and didn’t think it reported the information that they needed. Specifically, while Prator could be used as a checklist manager (having users enter tasks that needed to be done and noting when they had been done), participants had not been trained to use it this way, and it was unclear who was responsible for determining how Prator should be used.

Participants also felt that Prator would not help resolve issues around (often perceived rather than actual) legal barriers to information sharing. Municipal and provincial service providers operate under different pieces of national legislation, and there is poor clarity around what information can be shared (from patient records, for example) between the organizations, and between different layers of each organization. For example, medical test results (usually held by the provincial services) were often not available to nurses working in the municipality, and home care workers were often not told what illnesses the users had.

The primary workaround for the absence of a structured documentation system was reliance on “on-the-run” communication between staff who often met each other in workplaces (the cottage hospital, the nursing homes) or during meal and rest breaks. Unfortunately, not all staff who require information have the possibility to be regularly included in these conversations, and their success relies on people remembering what they need to tell or be told and knowing who would have that information. It also increases the risk of failing to document critical information. Again, it was often home care staff who missed out on these information flows because they work almost exclusively off-site. When attempts were made to include home care staff in coordination meetings, those meetings were still held at central workplaces (usually the cottage hospital) and it was difficult for perennially short-staffed home care teams to free up staff time to attend.

Some participants described how they tried to guess the information they thought they needed (particularly around medical conditions and text results) to provide their services. Home care staff might try and guess a patient’s medical condition from the medications they have been prescribed, for example. Alternatively, staff with better access to information would invent their own documentation protocols to pass on information, recognizing that they may be treading a legal “fine line” in doing so. One nurse, for example, used the home care task declarations (instructions about what care services were to be provided) to inform home care staff about the medical status of users.

The ’solutions’ that participants suggested for the communication challenge probably already exist in theory (through Prator, primarily) – clear epicrisis and discharge notices available locally before the patient leaves the distant hospital, routines and protocols (or checklists) for what needed to be in place before discharge, and a mechanism by which local staff could report back to distant services when care instructions were unrealistic (because of pharmacy opening times or stock issues, travel times, locally available expertise). There was enthusiasm about developing a universal patient charting system accessible to both municipality and province, but again there were concerns about who would legally be able to access such a system.

Participants identified the need for better case management structures, but there were also calls for changes to documentation procedures (having more checklists, for example) and better induction, education and training of staff. Ultimately, however, there was some skepticism about the capacity to implement change in an environment of staff shortages, lack of financial resources and fundamental world-view differences between local and distant (and sometimes municipal and regional) actors. Higher priority among participants was improving the level of patient-centredness of HHT processes, where it was felt that decisions were often made “over the patient’s head” (Participant X) and based on what was easier or more convenient for the service provider rather than the wants and needs of the patient.

Patients are individuals, not memos! (Participant E)

Geography

Pharmacies with restricted opening times and limited stock was just one of the challenges arising from the geographic context of Tärnaby. Participants recognized that geography (distance, small workforces, staff turnover and absences, small patient base so difficulties in building workforce experience) is not a “problem” that can be solved, but an ongoing constraint on how HHT services can be provided. It is very difficult, for example, to schedule additional home visits for returned patients because of the distances to be traveled between service headquarters and patient home. It is difficult to manage the large seasonal population fluctuations particularly caused by winter tourism – at which time the focus of provincial services at least becomes almost entirely on emergency medicine, and “routine” services are suspended or de-prioritized. It is difficult to manage the often rapid changes in weather and road conditions, meaning home care appointments can be delayed or canceled at very short notice. It is difficult to release staff for education and training when care units are under-staffed, training often occurs in distant places, and rural staff sometimes don’t “fit the box” in terms of which people have access to what sort of training.

While these are contextual factors that do not have “solutions” in the sense of improving the weather, or reducing distances, current workarounds such as high use of short term patient accommodation (in situations where it would not normally be needed), avoidable hospital readmissions and ad hoc service design (where neither user or provider has clarity about what will be done) were clearly seen as inadequate. They also tended to reduce the capacity of the user to influence their own care. A partial response may be to develop local education and training programs for service staff that reflect local conditions, but it was not clear exactly what this would look like.

It was, however, also emphasized that “geography” provides opportunities not just for the workarounds that are currently in place, but for longer term and more robust service design.

To think – what would work here. (Participant G)

It is a strength that we are small and have an overall view, local knowledge, we know each other, we meet. (Participant E)

Everyone knows each other, you do a little extra, don’t leave anything, I’m already going that way. (Participant J)

My experience is that patients rarely fall between the chairs, people solve problems even if it isn’t their responsibility. (Participant I)

Small size, distance, close local relationships all mean that novel approaches to service design can be attempted. Participants talked about the ability to ignore the battles between municipality and province and “just get on with” the work they need to do. They talked about the capacity to use individuals’ experience and skills even if their roles then don’t align exactly with professional boundaries. They talked about the capacity to engage patients and their families in processes of change by leveraging the personal (often not work related) relationships that they often have. They talked about benefits of small staff numbers (meaning information flows were less complex), and even staff turnover and staff shortages – knowledge and experience is regularly shared between municipality and province by staff moving between employers, there is capacity to capture skills and expertise even from staff who stay only a short period of time or who are accessed remotely. Their contact with local services, even if brief, can be used to build confidence and competence in the workforce because they come into contact with “everybody”. Participants noted that their rural experience gives them competence and knowledge that they would not have developed elsewhere.

Understanding of the rural context

Several participants thought it would be useful to develop education and training programs for those working in the distant cities so that they would improve their understanding of geographic conditions in Tärnaby and consequently be better positioned to contribute to care plans and care service provision. Two anecdotes are emblematic of the disconnect between the urban and the rural in HHT –

[Anecdote 1] A large proportion of people returning from a hospital stay need modifications to their home so they can continue to live independently. One of the most common, and easily implemented, modifications is the installation of a raised toilet seat. There is no local seller of raised toilet seats in Tärnaby, and the suggestion from participants is that many people have HHT delayed, and are forced into short term accommodation (or even transferred back to hospital) while waiting for a toilet seat to be delivered. The province is aware of this, and has stocks of toilet seats in Lycksele and Umeå. However, when patients are returned to Tärnaby with a discharge notice identifying the need for a toilet seat, no seat is sent with them. At the same time, the services in Tärnaby are discouraged from maintaining their own stock because the province has a stock. The solutions to this are obvious – in Tärnaby, the need for seats for many returning patients can be anticipated and seats ordered well in advance of their return, in Umeå, it should be routine to send patients home with a package of aids (including toilet seats) that they will need on arrival. Implementing the solutions, however, relies on addressing the communication issues (so that the Tärnaby home care service can anticipate when someone is returning to home) and raising awareness of the Tärnaby context among the urban service providers.

[Anecdote 2] A large proportion of patient transport from hospital back to home is done by taxi rather than by ambulance or for-purpose vehicles. Direct transfer from Lycksele to Tärnaby can take over three hours, and from Umeå to Tärnaby up to five hours. Transfers are not always direct, and taxis can be redirected to service other customers on the way, or to avoid poor roads or weather. It is not unusual, therefore, for transfers to take 6 or 8 hours or more. The Umeå and Lycksele hospital both have set discharge routines, which take place at the same time each day. The problem is that the discharge times in Umeå and Lycksele do not account for the transfer time to Tärnaby, and most returning patients arrive “after hours” with no qualified health professional (typically a nurse) to meet them and arrange their onward travel to home. A local solution may be to change standard work hours for nurses in Tärnaby so that they are present when needed, but this is likely to place extra staffing pressure on the Tärnaby based services and reduce the attractiveness of the workplace. Alternative solutions might include having more flexibility around discharge procedures in Umeå and Lycksele so that the time required to get back to Tärnaby is accounted for (and, not insignificantly, the comfort of the patient considered).

When patients do arrive back in Tärnaby, the urban actors may have prescribed services – medications, access to certain types of health professionals, visit frequencies – that are not available locally, leading to care plans written at discharge being modified locally. Greater involvement of local actors in the discharge process could improve this, however there is an entrenched cost-shifting culture (the municipality and the province trying to minimize the service components they need to fund) that stands in the way of better coordination.

Finally, participants noted a disconnect between how their services are perceived by distant actors (not just in the provincial administration, but nationally) and the on-the-ground realities. This arises from Sweden’s commitment to transparency in reporting on the state of health and care services, coupled with the rigid alignment of service catchments to municipal borders. A municipality like Storuman (population 5500) is directly compared with municipalities like Stockholm (1.7 million), Gothenburg (700 000) and Malmö (400 000). One or two bad cases in Storuman stand out in statistical reporting, while one or two cases in large municipalities are invisible. There was a sense among some participants, therefore, of receiving harsher criticism and resultant higher work stress simply because of the vagaries of the national reporting regimes. This can lead to higher risk aversion (and so delays in HHT, unnecessary readmissions, early entry into residential care etc.), and the patient’s wants or needs becoming a secondary consideration.

Discussion

sumamrises the key findings of the research in terms of the challenges arising from each of the key themes, the informal workarounds that are in place to address these challenges, and the ideas presented by case study participants for more formal responses.

Table 3. Challenges of HHT, workarounds and proposed responses – summary of research findings.

The challenges facing HHT in Tärnaby can be broadly classified as involving the organizational context (policies, procedures, relationships within and between organizations) and the rural context (specifically distance, small size, and patient-provider relationships). Challenges essentially relate to communication, coordination and collaboration (CCC) that needs to occur across multiple boundaries – geographic (including boundaries within the municipality), organizational, and professional. The status of Tärnaby district as sub-municipal exacerbates some of these challenges by creating a “fourth layer” of geography – national (where policy and regulation arises), provincial, municipal and then sub-municipal. Tärnaby’s staffing mix (provincial and municipal) and capacity is not the same as that assumed for Storuman (municipality) as a whole, but this distinction may be hard for distant actors to recognize given the primacy of municipal borders in service design. There clearly needs to be more attention paid to how things might work at sub-municipal level in Sweden’s spatially large northern municipalities (Eimermann, Adjei, Bjarnason, & Lundmark, Citation2022).

It is important to reiterate that the focus on challenges to good HHT in the results is a function of the nature of the research, which was looking for strategies for improvement (necessitating identification of challenges and risks). Participants universally emphasized that HHT in Tärnaby is usually good, and that what was needed was improvements in certain areas rather than a major redesign of processes. Concrete ideas for improvement often came back to the idea of case management (Kitzman, Hudson, Sylvia, Feltner, & Lovins, Citation2017), although it was interesting to note that the attempt at case management by the home care team had been largely unsuccessful because of staffing issues and poor communication with other providers. This challenge reflects both RNT (the nature of health and care work) and Beyond Periphery (dynamic workforces). It might be that a case management structure that is not dependent on an individual, but on a role or a teams-based structure may be more effective in this environment (Hogan et al., Citation2018). Along with case management, there were calls for checklists and protocols and generally improved documentation, training, including in legal obligations and responsibilities, and better discharge agreements with the distant hospitals. While better documentation could arise from better use of Prator, Prator clearly had limitations in “fit” for this rural environment, with perceptions of time wasted (sending memos to yourself or the colleague at the next table) and information missing (because of organizational or professional boundaries, or because Prator wasn’t used in the way it could be). Interestingly, digital solutions to communication or other challenges were not discussed in the interviews, despite being mentioned (in general terms) in the academic literature (Fahlberg, Citation2017). Perhaps the Prator experience – where a system designed by and for actors in “the city” is imposed on rural settings without good awareness of how it might fit with that context – has produced some skepticism about the potential of digital solutions.

The disconnectedness between the rural experience and “the city” was a persistent theme throughout, and related to all the challenges. Several participants raised the possibility of urban-based actors receiving training about the rural context, while noting their own need for training in the procedures and protocols that had largely been developed in urban areas. Current training is either absent (especially for home care workers) or difficult to access because courses are not given locally. Again, there may be digital solutions to this, or the opportunity for a province-wide HHT training program which has modules delivered in rural and urban places.

Some of the solutions participants identified were obvious (coordinating the delivery of toilet seats or discharge timing) and others would be relatively easy to design (case meetings, training modules). Many participants, however, doubted that these solutions could be implemented because of the lack of staff time and resources that could be dedicated to any change process. While the perception that HHT is not in crisis persists, the incentive to spend time or money on improvement is low, even though the inefficiencies (costing staff time and resources, not to mention impacts on patients) of current workarounds were also recognized.

A lack of time to dedicate to quality improvement is one of the paradoxes recognized in RNT (Lee & McDonagh, Citation2022) and emphasized in this research. Another was in the attitude to having limited staff, which at once made it difficult to access skills and impacted role clarity but made it easier to coordinate at least those activities that could be controlled in Tärnaby. Close relationships with patients meant that cases were managed individually, but also meant there was a risk of working “over the patient’s head” because staff assumed they knew what the patient would want or need (Swan & Hobbs, Citation2017). In the Beyond Periphery model, this “strength” of rurality – close ties – can be seen as increasing the dependence of patients on service providers.

Conclusion

The research has made some practical contributions to HHT in Tärnaby by identifying specific actions that could be taken to manage current risks. It has also made some theoretical contributions by applying the Beyond Periphery model to HHT, extending the scope of Rural Nursing Theory beyond the role of “the nurse,” and adding nuance to both theories through investigating a particular type of rural and a particular type of care activity. There is always a temptation to depict the Beyond Periphery model as one that reveals the disadvantages of rurality (Carson, Carson, & Lundmark, Citation2014), but this research also reveals how attributes such as distance, disconnectedness, diversity and detail allow workarounds to be successfully implemented. There needs to be caution, however, in ensuring that the components of Beyond Periphery are considered in attempting to formalize responses to the challenges described here. Otherwise, the risk is that new procedures continue to serve the needs of “the city” and the disconnect with local actors increases (Carson & Cleary, Citation2010).

There are some limitations to the research, including the absence of patient voices from the study. We were also not able to interview social workers due to staffing conditions at the time, and we chose not to interview local service managers who work “off the floor” and whose perspectives, particularly around change management and legal and procedural issues, would be insightful. The next step for this research is to design and test specific interventions, and this will need input from these voices. Case study research such as this provides a richness and volume of data that is difficult to distill into a simple “priority list” of such interventions, but what it can do is demonstrate the interconnectedness of themes, emphasizing how even small changes (detail) aimed at one challenge will likely have impacts across the system. Consequently, this research not only informs HHT in places like Tärnaby, but speaks to the operation of health and care services more broadly.

Poulin and Skinner’s (Citation2022) “rural gap” in understanding older people’s transitions through care is not just apparent in the literature, but in practice, where the disconnect between HHT actors across space, organizational and professional boundaries continues to make the process of transition unclear not just to patients and their families, but to service providers. Locally developed workarounds suit the rural context, but may serve to further disconnect or distance (Carson & Cleary, Citation2010) local actors from those in “the city” (including the municipal center) if they are not assessed for their efficiency and sustainability and somehow incorporated in documented procedures that are known and accepted by all involved. Some mechanism needs to be found so that rural actors are not required to invent fragile workarounds as a response to urban-centric system design, but can play a more direct role in that design.

Acknowledgments

The work in this article was in part funded by FORMAS, the Swedish Research Council for sustainable development, under the project ‘Cities of the norht: urbanisation, mobilities and new development opportunities for sparsely populated hinterlands (2016-00352)’

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Carson, D. A., Carson, D. B., & Lundmark, L. (2014). Tourism and mobilities in sparsely populated areas: Towards a framework and research agenda. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 14(4), 353–366. doi:10.1080/15022250.2014.967999

- Carson, D., & Cleary, J. (2010). Virtual realities: How remote dwelling populations become more remote over time despite technological improvements. Sustainability, 2(5), 1282–1296. doi:10.3390/su2051282

- Carson, D., Preston, R., & Hurtig, A. K. (2022). Innovation in rural health services requires local actors and local action. Public Health Reviews, 43, 1604921. doi:10.3389/phrs.2022.1604921

- Christiansen, L., Fagerström, C., & Nilsson, L. (2017). Nurses’ use and perception of an information and communication technology system for improving coordination during hospital discharges: A survey in swedish primary healthcare. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 35(7), 358–363. doi:10.1097/CIN.0000000000000335

- Congdon, J. G., & Magilvy, J. K. (2001). Themes of rural health and aging from a program of research. Geriatric Nursing, 22(5), 234–238. doi:10.1067/mgn.2001.119471

- Dellasega, C. A., & Fisher, K. M. (2001). Posthospital home care for frail older adults in rural locations. Journal of Community Health Nursing, 18(4), 247–260. doi:10.1207/S15327655JCHN1804_05

- Dussault, G., & Franceschini, M. C. (2006). Not enough there, too many here: Understanding geographical imbalances in the distribution of the health workforce. Human Resources for Health, 4(1), 1–16. doi:10.1186/1478-4491-4-12

- Eimermann, M., Adjei, E. K., Bjarnason, T., & Lundmark, L. (2022). Exploring population redistribution at sub-municipal levels–microurbanisation and messy migration in Sweden’s high North. Journal of Rural Studies, 90, 93–103. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.01.010

- Fahlberg, B. (2017). Preventing readmissions through transitional care. Nursing, 47(3), 12–14. doi:10.1097/01.NURSE.0000512879.91386.22

- Hardman, B., & Newcomb, P. (2016). Barriers to primary care hospital follow-up among older adults in rural or semi-rural communities. Applied Nursing Research, 29, 222–228. doi:10.1016/j.apnr.2015.05.003

- Harrington, R. A., Califf, R. M., Balamurugan, A., Brown, N., Benjamin, R. M. … Joynt Maddox, K. E. (2020). Call to action: Rural health: A presidential advisory from the American heart association and American stroke association. Circulation, 141(10), e615–e644. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000753

- Heslop, C., Burns, S., & Lobo, R. (2018). Managing qualitative research as insider-research in small rural communities. Rural and Remote Health, 18(3), 1–5. doi:10.22605/RRH4576

- Hilborn, B., & Singh, M. (2022). A scoping review of adult experiences of hospital to home transitions in rural settings. Online Journal of Rural Nursing and Health Care, 22(1), 57–99. doi:10.14574/ojrnhc.v22i1.703

- Hogan, K., Burnett, S., & Roberts, S. (2018). Help me get home safely: Preventing medically unnecessary hospitalizations. Perspectives, 39(4), 23–25.

- Jakobs, L. (2022). Rural nursing theory and research on the frontier. In C. A. Winters, (Eds.). Rural nursing: Concepts, theory, and practice (6th ed., pp. 65–74). New York: Springer. doi:10.1891/9780826183644.0006

- Kerry-Anne Hogan, R. N., Burnett, S., & Roberts, S. (2018). Help me get home safely: Preventing medically unnecessary hospitalizations. Perspectives, 39(4), 23–25.

- Kitzman, P., Hudson, K., Sylvia, V., Feltner, F., & Lovins, J. (2017). Care coordination for community transitions for individuals post-stroke returning to low-resource rural communities. Journal of Community Health, 42(3), 565–572. doi:10.1007/s10900-016-0289-0

- Lee, H. J., & McDonagh, M. K. (2022). Updating the rural nursing theory base. In C. A. Winters (Eds.). Rural nursing: Concepts, theory, and practice (6th ed. pp. 19–39). New York: Springer.

- McConnel, F. B., Demos, S., & Carson, D. (2011). Is current education for health disciplines part of the failure to improve remote Aboriginal health? Focus on Health Professional Education: A Multi-Disciplinary Journal, 13(1), 75–83.

- McDermid, F., Peters, K., Jackson, D., & Daly, J. (2014). Conducting qualitative research in the context of pre-existing peer and collegial relationships. Nurse Researcher, 21(5), 28–33. doi:10.7748/nr.21.5.28.e1232

- Nyhlen, S., & Giritli-Nygren, K. (2016). The ‘home-care principle’in everyday making of eldercare policy in rural Sweden. Policy & Politics, 44(3), 427–439. doi:10.1332/030557315X14357452041573

- Ohta, R., Ryu, Y., Kitayuguchi, J., Gomi, T., & Katsube, T. (2020). Challenges and solutions in the continuity of home care for rural older people: A thematic analysis. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 39(2), 126–139. doi:10.1080/01621424.2020.1739185

- Poulin, L. I., & Skinner, M. W. (2022). Emotional geographies of loss in later life: An intimate account of rural older peoples’ last move. Social Science & Medicine, 301, 114965. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114965

- Scott, A., Witt, J., Humphreys, J., Joyce, C., Kalb, G., Jeon, S. H., & McGrail, M. (2013). Getting doctors into the bush: General practitioners’ preferences for rural location. Social Science & Medicine, 96, 33–44. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.07.002

- Strasser, R. (2016). Learning in context: Education for remote rural health care. Rural and Remote Health, 16(2), 1–6. doi:10.22605/RRH4033

- Swan, M. A., & Hobbs, B. B. (2017). Concept analysis: Lack of anonymity. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(5), 1075–1084. doi:10.1111/jan.13236

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 1–10. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-8-45