ABSTRACT

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the specific features of financialization in peripheral and semi-peripheral contexts. To date, the majority of this research, however, consists of broad studies covering a number of countries, leaving a gap in the analysis of case studies, especially from east-central Europe. Therefore, the present article attempts to address this gap through an in-depth analysis of Latvia. The research shows that subordinate financialization is a changing and heterogeneous phenomenon that goes through uneven cycles of advance and retreat, which can lead to divergent dynamics between and within economies.

Introduction

In recent years, a growing number of scholars have shown an increasing awareness of the variegated nature of financialization. This term is used to refer to the growing power and influence of finance over economies and societies (Sokol and Pataccini Citation2020). In particular, there is a growing body of research delving into the specific features of financialization in developing and emerging economies (DEEs) and (semi)peripheral contexts, showing that it assumes a subordinate position to that of developed economies (Becker et al. Citation2010; Lapavitsas and Powell Citation2013; Rodrigues, Santos, and Teles Citation2016; Bortz and Kaltenbrunner Citation2017). Despite this growing interest, the academic literature on subordinate financialization, however, still shows two significant research gaps. First, the number of case studies that analyze the specific features of this phenomenon in individual countries is very limited. Second, the role of subordinate financialization in the former centrally planned economies of east-central Europe (ECE) remains underexplored, especially in regard to the Baltic countries.

Therefore, this research aims to address these gaps by answering the following question: how does the Latvian experience fit in with the current conceptualizations of subordinate financialization and what can it add to them? For this, this article will describe the Latvian economic cycles from the post-socialist transition to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and analyze their characteristics in regard to existing theoretical conceptualizations of subordinate financialization. Above all, the case of Latvia shows that subordinate financialization is not a one-way and homogeneous phenomenon. Instead, it goes through uneven cycles of advance and retreat affected by the interaction of external drivers with national and supra-national configurations, which can even lead to divergent dynamics between and within economies. Additionally, the research explores its implications in the face of the COVID-19 crisis and the prospects for post-pandemic recovery.

The article is structured as follows: the next section addresses the main theoretical characterizations of subordinate financialization in DEE and ECE contexts. The third section analyzes the three main economic cycles of the Latvian economy from the restoration of independence to the outbreak of the Corona crisis in light of the conceptualization of subordinate financialization. The fourth section presents the discussion and findings on the drivers and features of subordinate financialization in Latvia. It also addresses its implications in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The final section summarizes the main conclusions of this research.

Variegated financialization in DEEs and ECE

There is a growing consensus among scholars from different disciplines in social sciences that financialization has become the dominant feature of contemporary capitalism (Sokol Citation2017). This phenomenon has been initially defined as ‘the increasing importance of financial markets, financial motives, financial institutions, and financial elites in the operations of the economy and its governing institutions, both at the national and international levels’ (Epstein Citation2002, 3).Footnote1 To date, two dominant approaches can be found in the scholarship on financialization – the Marxist and the Post-Keynesian. Briefly, while the former emphasizes the rise and evolution of financialization mostly as a product of the social relations of production within capitalism, the latter has focused on the detrimental impact of booming finance on production and the real economy (Lapavitsas Citation2013). Despite these differences, most authors agree that the rise of financialization is closely related to the spread of the neoliberal political doctrine throughout the world (Lapavitsas Citation2009; Kotz Citation2011; Palley Citation2013; Dunhaupt Citation2016).

In macroeconomic terms, the early scholarly literature on financialization identifies three main indicators. First, the increasing volumes of private debt, especially that of households and non-financial corporations (NFCs) (for Stockhammer Citation2004, Citation2010; Epstein Citation2002; Krippner Citation2005; Epstein and Jayadev Citation2005; Palley Citation2007; Lapavitsas Citation2009). Moreover, Palley (Citation2010) contends that in the context of neoliberalism and financialization, rising debt and asset price inflation became the engine of aggregate demand, since they provided means to compensate wage stagnation and increasing income inequality. Second, Epstein (Citation2002), Blecker (Citation2005), Palley (Citation2007), and Stockhammer (Citation2012), among others, state that financialization allows countries to run larger external trade imbalances than in the past, since it has promoted growth in global trade exchanges through the expansion and relaxation of financing mechanisms and the liberalization of capital flows. This aspect has also been discussed by Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (Citation2008) and Lane (Citation2012) in regard to ‘financial globalization,’ especially in the EU context. Third, authors like Krippner (Citation2005), Palley (Citation2007, Citation2013), Orhangazi (Citation2008), Rossi (Citation2013), Hudson (Citation2015), Witko (Citation2016), and Jayadev, Mason, and Schröder (Citation2018) emphasize that financialization is characterized by the growing share of financial, insurance, and real estate (FIRE) activities in the overall economy, which have mainly developed to the detriment of manufacturing industries.

As pointed out by Rodrigues, Santos, and Teles (Citation2016), Santos, Rodrigues, and Teles (Citation2018), Kaltenbrunner and Painceira (Citation2018), and Choi (Citation2020), among others, until recently most of the studies on financialization have only focused on developed capitalist economies. Consequently, the features, drivers, implications, and manifestations of financialization in different contexts have remained underexplored. In response to this vacuum, in recent years a growing body of research on the variegated nature of financialization has developed. This line of research has aimed to broaden the understanding of financialization not only as a purely economic but also a geographical, political, and cultural phenomenon. Hence, denominations such as ‘peripheral,’ ‘dependent,’ or ‘subordinate’ have arisen, showing that financialization is a variable, complex, and dynamic phenomenon, capable of displaying particular characteristics in specific settings, such as those of DEEs.

In a seminal contribution, Becker et al. (Citation2010) show that peripheral financialization has been primarily dependent on over-liquidity in advanced economies. According to this perspective, high interest rates in DEEs attracted (short-term) financial capital, leading to overvalued real exchange rates, and providing incentives to residents in these countries to become (highly) indebted in foreign currency. In turn, this scenario tended to erode productive capacities, deepen current account deficits, and increase external debt, ultimately leading to financial crises. Lapavitsas and Powell (Citation2013) argue that the form of financialization varies according to institutional, historical, and political developments in each country. Financialization in DEEs has been particularly driven by the opening of capital accounts, the import of foreign capital, the accumulation of foreign exchange reserves and the increasing establishment of foreign banks. Thereby, financialization in DEEs has assumed a ‘subordinate’ character to that of developed countries (Lapavitsas and Powell Citation2013).

A number of authors have pointed out that in the context of international financial integration, capital flows, exchange rates, and the accumulation of international reserves have also played a key role as drivers of subordinate financialization in DEEs (Correa, Vidal, and Marshall Citation2012; Bonizzi Citation2013; Girón and Solorza Citation2015; Kaltenbrunner and Painceira Citation2018). For their part, a growing number of researchers are paying attention to the role of foreign investment in the rise of financialization in peripheral economies. Demir (Citation2007, Citation2009), for example, found that Foreign Portfolio Investments and Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) have contributed to the development of financialization in Argentina, Mexico, and Turkey, inducing a shift by domestic NFCs away from productive toward more short-term and speculative financial investment. Similarly, Karwowski and Stockhammer (Citation2017) show that external financial flows contribute to the phenomenon of financialization in DEEs. At the EU level, Rodrigues, Santos, and Teles (Citation2016), Pataccini (Citation2017), and Santos, Rodrigues, and Teles (Citation2018) have shown that EU integration has promoted the rise of financialization in the European periphery by the expansion of loanable capital, which favored non-tradable sectors and fueled an extraordinary rise in private debt and current account deficits.

While recent research has addressed how the interdependencies of the international monetary and banking systems have played a key role in the rise of financialization on a global scale (for example, Tooze Citation2018; Bortz and Kaltenbrunner Citation2017; Kaltenbrunner and Painceira Citation2018) show that the subordinated position of DEE currencies in the international monetary system molds the features of financialization in these countries and increases external vulnerability, due to the inability to borrow in domestic currency and the accumulation of foreign reserves. This, in turn, creates a dominance of short-term portfolio flows and a trend toward structural balance-of-payments crises. Similarly, Fernandez and Aalbers (Citation2019) contend that the embeddedness of DEEs in uneven global financial and monetary relations creates a position of subordination because they are forced to borrow in a foreign currency, which makes them dependent on liquidity conditions in other countries and creates a currency mismatch.

Despite the growing number of studies on financialization in (semi)peripheral contexts, to date, only a small number of them have focused on the former centrally planned economies of ECE. Gabor (Citation2010a, Citation2010b, Citation2012, Citation2013) shows that financialization in ECE has mainly been promoted by foreign financial actors, such as foreign banks and nonresident investors, and validated by local actors, such as central banks. Developing the arguments laid by Raviv (Citation2008), Sokol (Citation2013) asserts that Western financial expansion in ECE was inherently predatory, as foreign institutions were able to obtain higher returns than in the West but left the region increasingly indebted and economically vulnerable. Sokol (Citation2017) states that financialization had direct implications for uneven geographical development in ECE. For its part, Bohle (Citation2017) shows that harmonization with the EU financial framework in combination with the availability of cheap credit has induced a trajectory of (housing) financialization in the European periphery, including the countries of ECE. Büdenbender and Aalbers (Citation2019) claim that financial institutions that operate in already financialized economies have extended their operations to semi-peripheral countries, such as those of ECE, where they channel capital toward private credit, and especially mortgage loans, creating a subordinated financialization. Finally, Ban and Bohle (Citation2020) analyze the role of the state in the process of (de)financialization after the global financial crisis (GFC) in a group of selected ECE countries, which includes Latvia. While in many western European countries the state has been a key driver of financialization over the last decades (Schwan, Trampusch, and Fastenrath Citation2020), the authors argue that state capacity, particularly in the case of illiberal governments, is a key element in repressing financial globalization.

In summary, financialization has become a dominant feature of contemporary capitalism and recent research shows that this phenomenon assumes distinctive characteristics in (semi)peripheral contexts. To date, however, the vast majority of research on subordinate financialization consists of broad studies covering a varying number of countries, leaving a gap in the analysis of in-depth case studies, especially from ECE. Therefore, the present article attempts to address this gap through an in-depth analysis of Latvia, with the aim of contributing to shed light on the concrete interaction between external drivers and local configurations, as well as the mechanisms, dynamics, and manifestations of subordinate financialization in specific settings.

Economic cycles and subordinate financialization in Latvia

Since the restoration of its independence, one can identify three main cycles of the Latvian economy: from the post-Soviet reforms to the aftermath of the Russian financial crisis (1991–1999), from European integration to the GFC (2000–2010), and from post-crisis recovery to the COVID-19 pandemic (2011–2019). This article claims that each of these cycles has a direct relationship with the evolution of subordinate financialization in this country. Therefore, the periodized analysis presented below aims to show in greater detail and clarity the drivers and factors that shaped this phenomenon in each of its phases.

From post-Soviet reforms to the Russian financial crisis (1991–1999)

After the restoration of its independence from the USSR in August 1991, the Republic of Latvia embarked on a comprehensive process of economic and political reforms aimed at establishing a fully-fledged market economy and achieving EU membership (Åslund and Dombrovskis Citation2011). For that, the strategy chosen was the so-called ‘shock therapy,’ which sought to carry out the reforms as quickly as possible, trying to take advantage of the favorable context (Marangos Citation2007). The basic outline of the reforms was agreed with the IMF and based on the guidelines of the Washington Consensus agenda (WC) (Nissinen Citation1999). The first measures consisted of price liberalization and a drastic cut in subsidies for consumer goods, including food, which led to a sharp increase in inflation (World Bank Citation1993). To fight the price escalation, in May 1992 Latvia introduced a temporary currency, the Latvian Rublis, and in 1993, the country reintroduced its official currency, the lats (LVL) (Dreifelds Citation1996). Due to value fluctuations, at the beginning of 1994 the Bank of Latvia adopted a fixed exchange rate, taking the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights (SDR) as the reference. The exchange rate set was 1 SDR = 0.7997 LVL, approximately 1 LVL = 1.4 USD (US dollars) by the time of its introduction. Following neoliberal principles, Latvia also implemented a rapid and radical liberalization of capital and current accounts, and underwent a process of financial deregulation, establishing one of the most liberal exchange regimes in the world (OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) Citation2000).

The most distinctive aspect of Latvia’s transition was the rapid growth of its banking sector and its strong influence on the overall economy, which proved decisive in the following years. This was due to several factors. On the one hand, the minimum capital requirements for the establishment of a commercial bank were low and quickly liquefied by high inflation (Roolaht and Varblane Citation2009). Furthermore, in mid-1992, the Bank of Latvia liberalized interest rates (Bitans and Purvins Citation2012). Both factors created strong incentives for the establishment of new banks. On the other hand, during the Soviet period, there was a large relocation of Russian-speaking workers to Latvia, which accounted for almost 50% of the population in 1989 (Solska Citation2011; Bohle and Greskovits Citation2012). Due to the high proportion of the population this group comprised and its connections with the other former republics of the USSR, since the beginning of the transition many banks in Latvia were created to provide offshore services to nonresident customers, mainly based in Russia and other CIS countries (Ådahl Citation2002). Thereby, in 1993 there were 62 banks in Latvia, compared to 21 in Estonia and 26 in Lithuania (Myant and Drahokoupil Citation2010).

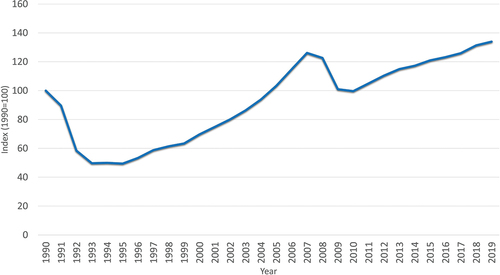

After three years of deep transitional recession, Latvia achieved meager growth in 1994 (see ). The fragility of its banking sector, however, soon dragged the country back into recession. In 1995, the largest bank in the country, Banka Baltija, went bankrupt, creating great disruption in the Latvian economy. By that point, it accounted for approximately 40% of the total assets and deposits in the Latvian banking system, amounting to 10% of the country’s GDP (Nissinen Citation1999). While the causes of Banka Baltija’s collapse were the result of fraudulent activities, this episode exposed the lack of adequate supervision and the extremely risky practices conducted by the new banking institutions.

Figure 1. Latvian GDP index, 1990-2019 (1990=100)Source: Author’s own calculations, based IMF World Economic Outlook Database, October 2020 (https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2020/October) and Korhonen (Citation2001).

Yet, despite the introduction of stricter supervision, in the late 1990s the stability of the Latvian banking sector was hit again, this time by the Russian financial crisis. As noted by Ådahl (Citation2002), by 1998 more than 10% of total Latvian banks’ assets were exposed to the Russian market, and more than one-third of this exposure was related to Russian bonds that lost most of their value with the crisis. Rigas Komercbanka, the fifth-largest bank in the country, which held 14% of its assets in Russia, and about 20% of its capital was owned by Russians (Ådahl Citation2002). As a result, in 1999, the central bank declared Rigas Komercbanka insolvent along with three other smaller banks, which had serious effects on the stability of the Latvian financial sector and the real economy.

In this context, the Latvian authorities, in alignment with the other Baltic countries, sought the assistance of Nordic banking groups as strategic investors for the restructuring and consolidation of the banking system (Schipke et al. Citation2004; Grittersova Citation2017). This strategy was also endorsed by the EU in light of their possible accession (Jacoby Citation2014; Bohle Citation2018). This process was largely dominated by Scandinavian institutions, particularly, by two Swedish groups, Swedbank and SEB, which expanded their activities in the Baltic states through subsidiaries (Epstein Citation2017). Unlike the other Baltic states, however, Latvia kept a significant share of domestic banks. Thus, after the arrival of Nordic banks the Latvian banking sector was divided into two segments: foreign-owned banks, composed mainly of subsidiaries of Scandinavian groups and focused on the domestic market; and domestic banks, mostly person-privately owned and specializing in serving nonresidents (Ådahl Citation2002).

After a decade of transition, the economic results were mixed. By the end of the 1990s, Latvia’s real GDP was still 36% below pre-transition levels. Due to the progress achieved in the establishment of market mechanisms, however, in December 1999 the European Council decided to start accession negotiations with Latvia, opening a new stage in the political, economic, and social history of the country.

Europeanization, boom and bust (2000–2010)

With the start of formal negotiations for EU accession, Latvia began the phase of formal integration with the EU or, ‘Europeanization.’ Due to the ‘EU enlargement effect’ (Trasberg Citation2012), during the first years of the twenty-first century, the Latvian economy showed an unprecedented pace of growth. The evolution of Latvian GDP in these years was above the average of ECE countries and EU members, and when Latvia joined the EU, in 2004, the economic boom gained momentum. Latvia’s accumulated GDP growth over the period 2004–2007 was the highest in the EU and one of the fastest in the world (Skribane and Jekabsone Citation2013). Moreover, in January 2005 the Bank of Latvia established a new exchange rate, set at 1 LVL = 1.4229 euros, aimed at fulfilling the euro convergence criteria.

Throughout this phase, Latvia underwent a process of ‘financial deepening’ (Christensen and Rasmussen Citation2007; Hübner Citation2011). Financial integration with the EU opened the Latvian economy to external capital flows, especially from other member countries (Kattel Citation2010). Furthermore, compliance with EU conditions and regulations provided legal security for investors, who saw the new member countries as an attractive option to expand their activities (Jacoby Citation2010; Medve-Bálint Citation2014). Consequently, since the beginning of 2000, there was a substantial increase in capital inflows, both in the form of FDI and debt instruments, mainly related to the expansion of Scandinavian banks in the region (Kattel Citation2009; Hübner Citation2011; Bohle Citation2018).

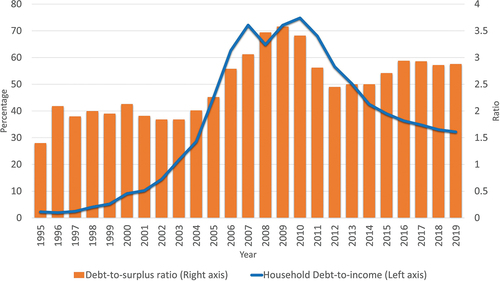

In alignment with the features of subordinate financialization described by Becker et al. (Citation2010), among others, the expansion of bank credit led to an exponential increase in the debt ratios of households and NFCs in foreign currency, especially after 2004 (see ). Thereby, the debt-to-surplus of NFCs doubled between 2003 and 2009, while the debt-to-income of households increased more than seven times, from 10.2% in 2001 to 72% in 2007. By 2007, external liabilities represented 160% of GDP, while over 88% of loans were denominated in foreign currencies, mostly euros (Deroose et al. Citation2010; European Commission Citation2010), since they had lower interest rates than loans in lats and they were considered riskless by investors due to the pegged exchange rates and the strong commitment to join the EU’s Economic and Monetary Union (Becker and Jäger Citation2012).

Figure 2. Evolution of households’ debt-to-income (as %) and NFCs debt-to-surplus (ratio)Source: Author’s own elaboration based on Eurostat - Gross debt-to-income ratio of households (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-datasets/-/tec00104) and OECD - Non-Financial corporations debt to surplus ratio (https://data.oecd.org/corporate/non-financial-corporations-debt-to-surplus-ratio.htm#indicator-chart).

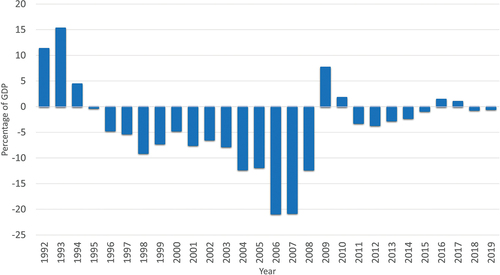

Regarding the current account balance, since the mid-1990s until the GFC, Latvia experienced constant and increasing trade deficits (see ). This was directly related to the combination of radical foreign trade liberalization, following WC guidelines, and an overvalued exchange rate that affected the competitiveness of tradable sectors (Hübner Citation2011; Hudson Citation2014). During the period of Europeanization, however, this dynamic dramatically deepened. On the one hand, massive access to cheap credit provided by foreign banks and integration into the European Single Market led to a strong increase in imports. On the other hand, the economic boom of the early 2000s led to a sharp increase in Unit Labor Costs, which in turn, led to a loss of competitiveness in manufacturing sectors (Kattel and Raudla Citation2013).Footnote2 As a consequence, Latvian exports tended to be concentrated in primary goods, mainly wood and base metals, while imports consisted mostly of intermediate and consumer goods. Since 2000, Latvia’s current account deficits have increased notably, reaching more than 20% of GDP in 2006 and 2007, showing consistency with the characterization of subordinate financialization in peripheral EU members made by Rodrigues, Santos, and Teles (Citation2016) and Santos, Rodrigues, and Teles (Citation2018). Additionally, since a large part of this deficit was financed by debt in euros, the trade imbalances were associated with an outflow of capital paid as interest, which also had a negative effect on the external financial position of the country.

Figure 3. Lativa’s current account balance, 1992-2019 (as % of GDP)Source: IMF World Economic Outlook Database, October 2020 (https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2020/October).

Initially, bank credit in Latvia was financed by deposits from the public. From the early 2000s, however, foreign parent banks began to borrow euros on the international capital markets at very low interest rates and lend this capital to Baltic subsidiaries, while domestic banks were engaged directly in wholesale capital markets (Aarma and Dubauskas Citation2011; Epstein Citation2017; Bohle Citation2014). These operations brought substantial benefits to foreign banks, while allowing domestic institutions to expand their credit supply almost limitlessly. As argued by Kandell (Citation2009), from 2002 to 2007, the Baltic countries were the main drivers of growth for Swedbank and SEB, as the returns on Baltic assets were substantially higher than those of Sweden. In other words, during the boom years foreign banks conducted massive carry trade operations with local households and firms (Gabor Citation2010a; Kattel Citation2010).Footnote3 As argued by Fernandez and Aalbers (Citation2019) and Bonizzi, Kaltenbrunner, and Powell (Citation2020), carry trade operations are characteristic of subordinate financialization regimes, since financial actors benefit from interest rate differentials between developed economies and DEEs, as well as from sustained periods of real exchange rate appreciation that is usually caused by carry trade operations themselves.

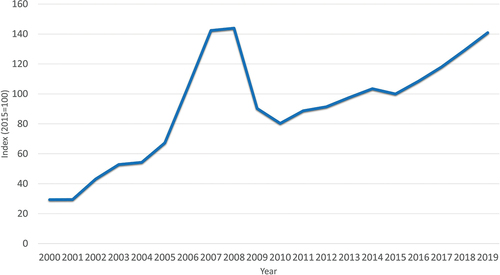

The unfettered expansion of private credit in Latvia also had direct effects on house prices. From the beginning, foreign banks operating in the Baltic countries were very active in developing the mortgage loan market, which was virtually non-existent until the beginning of 2000 (Bohle Citation2017, Citation2018). Moreover, during 2004–2007, the long-term interest rates on mortgages were strongly negative and significantly below the eurozone average, which created strong incentives to borrow (Bukeviciute and Kosicki Citation2012). As a result, in 2005–2006, mortgage loans increased by more than 90% on a yearly basis, becoming the main type of debt in Latvia (Klyviene and Rasmussen Citation2010; Purfield and Rosenberg Citation2010).

In line with the phenomena analyzed by Pettifor (Citation2006) and Ryan-Collins, Loyd, and Macfarlane (Citation2017), among others, in Latvia, the rise in mortgage lending fueled a marked real estate bubble during the pre-crisis years. As shown in , the Real House Price Index began to increase in 2002 but it skyrocketed after 2004, peaking in 2007. According to the European Commission (Citation2010), the real prices of residential properties in Latvia increased more than three times between 2003 and 2007. Once again, this phenomenon was a consequence of a combination of factors, including easy access to mortgage credit, overly optimistic expectations concerning Latvian economic convergence with EU standards, and speculative investments by nonresidents (Kattel and Raudla Citation2013). The rise in real estate prices caused an increase in the average value of mortgage loans and in some cases, borrowers were taking more than one loan at a time in order to pay the rising cost of the properties. Ultimately, these practices were key to further fueling the housing bubble. Throughout this period, however, Latvia’s population permanently declined, suggesting that the rise in property prices was not related to housing demand, but the strong financialization of real estate, which turned properties into financial assets rather than ordinary commodities (see Aalbers Citation2016).

Figure 4. House price index 2000-2019 (2015=100)Source: Eurostat - House price index - annual data (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-datasets/product?code=tipsho20).

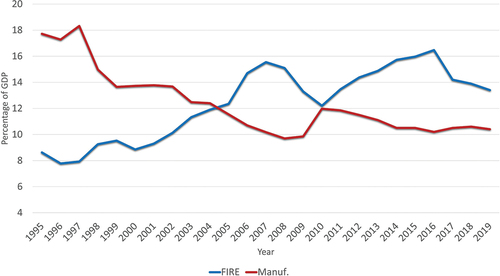

In relation to the evolution of FIRE activities, since the beginning of the transition the Latvian economy experienced marked structural changes. On the one hand, the early radical liberalization policies led to fierce deindustrialization (Greskovits Citation2014). Therefore, the manufacturing sector’s contribution to GDP declined sharply from the early 1990s, especially during the booming years of 2004–2007, reaching the lowest point in 2008 (see ). On the other hand, FIRE activities expanded hesitantly until 2000, but they rose substantially in the pre-crisis years, surpassing the contribution of manufacturing to GDP in 2005, and peaking in 2007. This trend was temporally reversed during the crisis years (2008–2010) but resumed in 2011.

Figure 5. Evolution of FIRE and Manufacturing activities (as % of GDP)Source: Author’s own calculations based on Eurostat - Gross value added by A*10 industry - selected international annual data (https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=naida_10_a10&lang=en).

As argued by Krippner (Citation2005), Palley (Citation2007, Citation2013), Rossi (Citation2013), and Witko (Citation2016), among others, the growth of FIRE activities at the expense of manufacturing is a clear indicator of the rise of financialization. In a nutshell, financialization diverts investment from the manufacturing sector to the financial sphere in search of higher profits, undermining the productivity and competitiveness of non-financial firms. In addition to that, the delocalization of production and the liberalization of the current account that usually accompanies financialization put the survival of manufacturing companies in jeopardy, especially for small and medium domestic enterprises in tradable sectors, which have more limited resources and fewer opportunities to access to external financing. In this way, financialization not only leads to a decline in manufacturing activities, but also to a growing concentration and foreignization of the sector. Yet, in the case of Latvia, Hudson (Citation2015, 215–217) shows that lax fiscal and financial policies applied by the government in the pre-crisis years played a key role in fostering real estate speculation and, with it, a rise in FIRE activities.

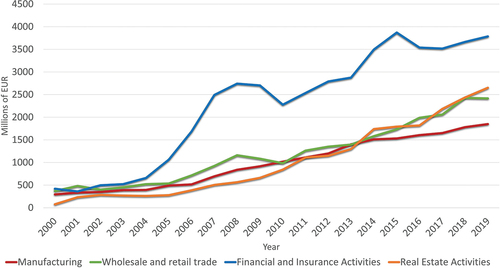

Yet, in connection with the characterization of subordinate financialization, the dynamics of the FIRE activities should be analyzed in the light of FDI inflows. Since independence, the net average annual FDI inflows to Latvia amounted to more than 4% of GDP, peaking at 8% and 9% in 2006 and 2007, respectively. Throughout this period, FIRE activities received the lion’s share, accounting for more than 50% in 2000–2007. In particular, the item ‘banking and financial intermediation’ was the main recipient of foreign investments. As seen in , this trend started in the late 1990s when Scandinavian banks began to invest heavily in the Baltic republics and accelerated after EU accession in 2004. Thus, in line with the characterization of subordinate financialization in other DEEs, FDI is key in explaining the rapid expansion of FIRE before the crisis and the high share of foreign ownership in the banking sector in Latvia, which reached 65% of total assets in 2007.

Figure 6. Inward FDI by kind of activity (in millions of EUR)Source: Bank of Latvia – Direct Investment data by kind of activity (https://statdb.bank.lv/lb/Data/131).

In response to the outbreak of the subprime mortgage crisis in the United States, deteriorating global financing conditions, and the negative outlook for the Latvian economy, in late 2007, banks tightened credit standards and applied more conservative policies to reduce their exposure to risk and uncertainty (Klyviene and Rasmussen Citation2010; Bohle Citation2017). In doing so, they sharply reduced loans to businesses and households (Bitans Citation2012; Kattel and Raudla Citation2013). These conditions dragged the Latvian economy into recession. The situation was worsened by the exposure of the domestic banking sector. Ultimately, domestic banks that provided offshore services for nonresidents had limited ties with local markets (OECD Citation2019). Yet, in the fourth quarter of 2008, approximately 40% of bank deposits in Latvia belonged to nonresidents, of which more than 85% were on-demand (OECD Citation2016). Thus, when the crisis broke out, a large share of foreign investors withdrew their deposits, which worsened the already bleak situation of the Latvian economy (Pataccini and Eamets Citation2019). In this scenario, Parex, the second largest bank in the country, was particularly vulnerable because it was engaged in both segments of the Latvian banking sector.

During the boom years, Parex mainly relied on European wholesale markets to finance the expansion of credit while also attracting large amounts of nonresident depositors (Epstein Citation2013). Thus, when the GFC hit, Parex was doubly exposed: in the months following the collapse of Lehman Brothers, Parex lost 25% of its deposits, while also having to face the repayment of syndicated loans for the equivalent of 4.6% of Latvian GDP (Åslund and Dombrovskis Citation2011). The government decided to nationalize Parex bank in November 2008, which turned the banking crisis into a fiscal crisis and, at the same time, a balance of payment crisis. As a result, Standard & Poor’s downgraded Latvia’s credit rating to BB+, considered as ‘non-investment’ or ‘junk,’ making it much harder for the Latvian government to borrow on international financial markets (Pataccini and Eamets Citation2019). Consequently, in February 2009 the Latvian government negotiated a ‘bailout’ loan with the IMF (International Monetary Fund), the EU, the World Bank, the EBRD (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development), and other international financial actors, amounting €7.5 billion, equivalent to almost 40% of Latvia’s GDP (Åslund and Dombrovskis Citation2011).

In this context, the Latvian government opted for the implementation of an internal devaluation strategy. This consisted of maintaining the fixed exchange rate and restoring international competitiveness by reducing local productive costs, mainly wages (Hudson Citation2014; Woolfson and Sommers Citation2016). The aim of this decision was meeting the exchange rate criterion to adopt the euro as soon as possible, since this was expected to solve the country’s financial imbalances (Åslund and Dombrovskis Citation2011). The immediate consequences of these policies, however, were catastrophic: GDP fell by almost 25% in 2008–2010, unemployment exceeded 20% in early 2010, and 10% of the country’s population emigrated between 2008 and 2013 (Hilmarsson Citation2014).

From recovery to the COVID-19 crisis (2011–2020)

After the GFC, the economic and financial landscape in Latvia changed significantly. In the wake of the ‘Great retrenchment’ in international capital flows (Milesi-Ferretti and Tille Citation2011), Latvia, like several other countries of ECE, experienced sudden stops and reversals of capital flows; while foreign banks reduced cross-border operations, curtailed loans, shed assets, and committed to financing operations with local deposits in an effort to reduce risk exposure and restore their capital ratios (Gros and Alcidi Citation2015; Bank for International Settlements Citation2018; Lahnsteiner Citation2020). Furthermore, after the GFC, stricter regulations on banking activities were introduced at the EU and regional levels through the establishment of new bodies, such as the European Systemic Risk Board, created in 2010, and the Nordic-Baltic Macroprudential Forum, created in 2011 (Farelius and Billborn Citation2016), and in 2016 Latvia introduced more stringent regulations and controls to prevent money laundering and terrorist financing activities, focusing primarily on deposits from nonresidents in domestic banks (Saeima Citation2008).

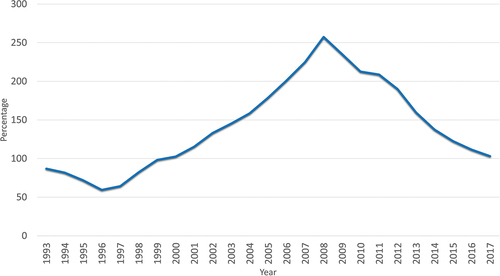

Due to these measures, Latvia experienced notable changes in its financial sector. The private debt-to-GDP ratios decreased markedly after 2009 (), as did loan-to-deposit ratios (see ). Furthermore, between 2016 and 2018, nonresident deposits in Latvia decreased by more than 60% (OECD Citation2019). Similarly, Latvia also underwent some important macroeconomic changes. Dunhaupt and Hein (Citation2019) show that after the GFC, Latvia’s economic growth became more export-oriented. These changes have contributed to keeping foreign trade closer to balance (see ). Latvia resumed economic growth in 2011 and succeeded in becoming a member of the eurozone on 1 January 2014. Economic growth, however, remained dependent on foreign capital and the rise in exports failed to offset the decline in FDI and bank credit (Bohle Citation2018). As a result, the economic recovery was slow compared to the previous collapse, and it took ten years, until 2017, for Latvia to regain its pre-crisis level in real GDP ().

Figure 7. Latvian Loan-to-deposit ratio, 1993-2017Source: World Bank - Global Financial Development Database - Bank credit to bank deposits (%) (https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=global-financial-development#).

Interestingly, Latvia experienced a drastic reduction in private debt levels while DEEs accumulated the ‘largest, fastest, and most broad-based’ debt wave in half a century (World Bank Citation2019; Ayhan Kose et al. Citation2020). In this regard, Latvian debt indicators, like those of other ECE economies, moved in the opposite direction to that of subordinated financialization in the rest of the world. To understand these developments, one must look at the unconventional monetary policies, such as the so-called Quantitative Easing (QE), applied by central banks of developed capitalist economies, including the European Central Bank (ECB).

In response to the GFC, the ECB started buying assets from commercial banks with the aim of creating money in the banking system and promoting economic growth (European Central Bank Citation2016). QE policies generated liquidity in the banking system, a large part of which was geared toward assets in DECs in search of higher rates of profit than those in developed economies, fueling fast-growing public and private debt in those countries (Fernandez and Aalbers Citation2019). At the same time, by keeping interest rates extremely low within the Eurozone, the ECB’s QE policies also affected the profitability of EU banks and their incentives to extend loans to customers. As stated by Demertzis and Demertzis and Wolff (Citation2016) ‘QE reduces long-term yields and thereby reduces term spreads. With this, the lending-deposit ratio spread falls, making it harder for banks to generate net interest income on new loans.’ Therefore, QE policies show radically different effects among (semi)peripheral economies, emphasizing the heterogeneous and specific character of subordinated financialization in each context.

It is also important to note that since the end of the GFC the Latvian financial sector has maintained and even deepened some of its previous trends. First, despite a significant population decline, property prices have risen steadily since the end of the GFC and by 2020 were on the verge of reaching the maximum levels before the Covid-19 pandemic downturn (see ). Second, FIRE’s activities remained one of the main contributors to Latvia’s GDP. The decline during the GFC was followed by a rapid increase until 2016, when they began to decline again due to the introduction of more stringent measures on money laundering. Yet, they are still above the manufacturing sector in terms of Gross Value Added (GVA) contribution to GDP (see ). Third, in terms of FDI, FIRE activities have also continued to be the main recipient of foreign investment in Latvia, followed by wholesale and retail trade. The manufacturing sector has managed to attract investment since the end of the crisis, but after joining the eurozone, the pace of investment growth slowed (see ).

Likewise, since the end of the GFC the two main features of the Latvian banking sector deepened, namely concentration and foreignization. First, many domestic banks failed due to the crisis or were forced to shut down due to criminal procedures. These include the above-mentioned Parex Banka along with Latvijas Krājbanka, Trasta Komercbanka, GE Money Bank, Latvijas Hipotēku un Zemes Banka, ABLV, and PNB Banka.Footnote4 Second, in March 2020 Handelsbanken (Sweden) followed the example of Scania Finans (Sweden), by ceasing operations in the Baltics due to low profitability and high costs (Reuters Citation2019). Third, the sector also went through a phase of consolidation, led by foreign institutions. In 2013 Swedbank acquired the Baltic operations of UniCredit Bank (Italy), in 2016 the Latvian branch of Danske Bank (Denmark) transferred its retail business to Swedbank AS (see more below) and in October 2017, Nordea and DNB combined their Baltic businesses to create Luminor Bank AS (Luminor Citation2017).

As a result of these events, since the end of the GFC the Latvian banking sector experienced a marked concentration that consolidated the position of the main foreign institutions: as of 31 December 2008, there were 27 banks in Latvia and the five largest banks controlled 69.5% of total assets (FKTK (Finanšu un Kapitāla Tirgus Komisija) Citation2008). In the first quarter of 2020, however, there were 15 banks and the five main banks accounted for almost 85% of total assets, while the three largest banks, all of them of foreign origin, accounted for almost two-thirds of total assets (Finance Latvia Association Citation2020). In turn, it is important to note that QE policies did not affect all banks operating in Latvia in the same way. While the largest banks, mainly foreign ones, had direct access to financial markets and benefited from central banks’ asset purchase programs and overseas investments, domestic banks had limited access to capital markets and were more dependent on loan-deposit margins. Therefore, starting from 2015 smaller domestic banks faced declining profits and even serious losses, especially after 2016, when nonresident deposits fell dramatically. These developments reinforced the dominance of foreign institutions, widening the gap with domestic banks.

Drivers and implications of subordinate financialization in Latvia

As Lapavitsas and Powell (Citation2013) argue, the specific form of financialization varies according to the institutional, historical, and political developments of each country. Therefore, to understand the rise of subordinate financialization in Latvia one must look at its particular characteristics. Based on the evidence presented in the previous section, this research asserts that Europeanization, foreign banks, and the system of international monetary hierarchies shaped the process of financialization in Latvia during the pre-crisis period, establishing asymmetric financial relationships between this country and developed economies. It is important to note that after the GFC, however, the picture becomes more complex, as some key indicators begin to follow divergent paths, challenging some of the existing knowledge on subordinate financialization.

First, through the process of Europeanization, the EU has been a dominant force in shaping capitalism and financial integration of ECE countries (Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier Citation2004; Vachudova Citation2005; Grabbe Citation2006; Bruszt and Vukov Citation2017). Medve-Bálint (Citation2014) contends that the EU has been a key player in opening ECE countries to foreign investors through the financing of national investment promotion agencies and the Commission’s reports on countries’ progress toward accession, which openly advocated privatization in the banking sector and openness to FDI. Moreover, Jacoby (Citation2010) and Bohle (Citation2018) assert that compliance with European rules and regulations not only opened these economies for capital flows, but also provided legal security for investors. In relation to the banking sector, Ross (Citation2013) argues that harmonization with EU regulations led to a procyclical relaxation of previously stricter national regulations, as in the case of capital requirements for mortgage loans and capital adequacy requirements. Additionally, the EU endorsed the role of Scandinavian institutions as strategic investors in the Latvian banking sectors after the Russian financial crisis (European Commission Citation1999). In this way, integration with the EU promoted FDI inflows that transformed the Latvian banking sector, triggering rapid concentration, expansion, and foreignization, as well as the adoption of new and more lax regulations and provisions. Moreover, it is worth mentioning that during the GFC the EU was the main advocate of internal devaluation (Lütz and Kranke Citation2014). Above all, the EU was concerned that the devaluation of the Latvian currency would wreak havoc on regional financial markets, causing spillover effects and inducing capital flight from other ECE countries (Kuokstis and Vilpisauskas Citation2010). In doing so, the EU was a key player in securing the status quo of subordinate financialization in Latvia at the expense of economic recovery.

Second, since the beginning of the transition, the banking sector in Latvia grew rapidly, and banks dominated the domestic financial system. During the phase of Europeanization, Scandinavian banks were instrumental in driving a growth model of ‘privatized Keynesianism’ – a substantial expansion in aggregate demand through private debt (see Crouch Citation2009). These practices were key to changing companies and households’ patterns of consumption and investment, becoming the main driver to engage these sectors in financial markets and transform the Latvian economy. Yet, contrary to some common narratives, the capital flowing into Latvia during the boom years was not simply savings from northern Europe escorted to the periphery (for example, Sinn Citation2014), but massive amounts of credit borrowed by banks in international capital markets at extremely low interest rates (carry trade operations). In this way, banks (mostly foreign) took advantage of liquidity overhang in advanced economies around the world to channel these funds to the Latvian credit market – with high profitability.

The role of foreign banks in the Latvian economy can be explained through the concept of ‘financial chains.’ As shown by Sokol (Citation2017), in contemporary capitalist economies, households, firms, banks, central banks, states, and financial markets are interconnected through a myriad of linkages referred to as ‘financial chains,’ which operate as stable circuits of value transfer between actors across time and space. In particular, credit-debt relationships are paradigmatic examples of financial chains because they establish formal relations for the transfers of value in two directions, for example, loan and repayment. Thus, while these links were very effective in spreading the high liquidity provided by foreign banks, driving rapid growth, they also spread the crisis to all sectors of the Latvian economy, causing a general decline. In this way, as the case of Latvia shows, through financial chains, foreign banks can not only boost the circulation of value within an economy, but also create the conditions for crises. In doing so, they (re)produce social and geographic inequalities, including the asymmetric financial relations characteristic of subordinate financialization.

Third, Latvian monetary subordination also played a fundamental role throughout the entire process. One key weakness of DEEs is that they cannot borrow in their domestic currency (Gabor Citation2010b; Kaltenbrunner and Painceira Citation2018; Sokol and Pataccini Citation2020). In the long term, this creates a currency mismatch that poses serious burdens and requires strong adjustments. As pointed out by Bortz and Kaltenbrunner (Citation2017, 382–383), the reduced liquidity premium of currencies in the lower ranks of the international monetary hierarchy means that they have to offer higher interest rates to maintain demand, are subject to short-term speculative operations, and suffer an excessive degree of external vulnerability because any change in international liquidity preference might cause a flight to quality. Thereby, in the case of Latvia, operations in lats had higher rates than in euros. Moreover, for the Bank of Latvia it was important to attract foreign currencies in order to accumulate reserves and be able to maintain a fixed exchange rate. This scenario of virtual financial bi-monetarism reinforced incentives to hold positions in foreign currency, which deepened the currency mismatch, while increasing the vulnerability of the Latvian banking system and the Latvian economy. One of the main consequences of this configuration is that, as O’Connell (Citation2015) points out, when the financial bubble bursts it creates not only a banking crisis but also a foreign debt crisis. Thereby, the strategy chosen by the Latvian government to cope with the crisis was aimed at resolving the currency mismatch through integration with the eurozone, even at an extremely high social cost (see Woolfson and Sommers Citation2016). In other words, the internal devaluation strategy should be interpreted as a response in the framework of its subordinated position in the international monetary hierarchy.

Subordinate financialization and the COVID-19 crisis in Latvia

The outbreak of COVID-19 in early 2020 has posed new threats and challenges for the Latvian economy. As mentioned above, over the last decade the country has managed to improve some of its main macroeconomic and financial imbalances. As a small and open economy, however, Latvia remains highly exposed to external shocks. Due to Latvia’s current reliance on foreign trade, the slowdown in the global economy had direct implications for its performance. At the same time, developments in the banking sector have also increased Latvia’s vulnerability.

Since the two main banks operating in Latvia are Swedish subsidiaries, developments in this country may have direct effects on its economy. In recent years the Swedish economy has accumulated various macroeconomic and financial imbalances, while displaying strong features of financialization (Belfrage and Kallifatides Citation2018). Traditionally, Swedish companies and households rely mainly on bank credit to cover their financial needs while preferring to invest their savings in mutual and pension funds (Belfrage and Ryner Citation2009). Consequently, Swedish banks turn to financial markets to fill this gap and meet the demand for loans (Stenfors Citation2014). In 2018, for instance, more than 50% of its financing came from international markets, while loan-to-deposit ratios stood at 205% at the end of 2019 (Lietuvos Banka Citation2020). In that year, private debt to GDP amounted to 204% and this credit boom has fueled a housing bubble that is feeding back the demand for loans (Johnson Citation2019). Swedish banks are also closely interconnected, as they hold substantial amounts of each other’s covered bonds (Sveriges Riksbank Citation2019).

In the context of the COVID 19-induced crisis, there are several potential sources of imbalances for Swedish banks. First, a protracted decline in economic activity and national income could soon transfer the problem to banks, which will find increasing difficulties in collecting their credits. In turn, a recession could also burst the housing bubble, which would reduce the value of collateral and private wealth. Second, given the high level of interconnectedness of Swedish banks, the problems of one bank can quickly spread to others. Furthermore, it is important to remember that Sweden does not belong to the eurozone, therefore, banks take credits in foreign currency – mainly USD (Stenfors Citation2014), adding exchange risk to the equation.

If parent banks face difficulties, they can pass the problem on to their Baltic subsidiaries through three main channels: a) a decrease in cross-border lending; b) an increase in funding costs for subsidiaries; and c) greater volatility of deposits due to growing concern of depositors and lack of confidence. Consequently, Swedish economic imbalances, the high level of leverage in foreign currency, and the interconnectedness of Swedish banks may have direct effects on the Latvian economy. Reflecting its exposure to external imbalances, in April 2020 the credit rating agency Fitch revised the Outlook on Latvia’s Long-Term Foreign-Currency Issuer Default Rating to Negative due to the growing risks associated with the COVID-19 pandemic (Fitch Ratings Citation2020).

In addition to these aspects, one particular concern that has recently hit the Nordic-Baltic region is the weakened reputation of its banking institutions due to public scandals related to money laundering activities. Ban and Bohle (Citation2020) have stated that after the GFC, Europe’s failure to contain money laundering operations gave a ‘second life’ to Latvian domestic banks, particularly those who provide offshore services to nonresident customers. While this was the case until 2016 (see above), recent events show that these types of activities were not exclusive to local banks.Footnote5 In 2018, it was uncovered that the Baltic branches of Danske Bank were involved in massive money-laundering transactions between 2007 and 2015, amounting to €200 billion (Milne and Winter Citation2018). After this episode, various investigations were launched at other Nordic banks operating in the Baltic countries. As a result, in March 2020, the Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority imposed a record fine of 4 billion Swedish krona (SEK) (approximately €360 million) on Swedbank, and in June 2020, the Swedish financial supervisory authority fined SEB bank 1 billion SEK (€96 million) for ‘deficiencies in its work to combat anti-money laundering in the Baltics’ (Latvijas Sabiedriskie Mediji Citation2020). Both institutions, however, may still face new fines in the future as criminal investigations in the Baltics and the United States continue. This may reduce the parent banks’ capital, eventually leading to decisions that could compromise the ability of subsidiaries to cope with the long-term effects of the COVID-19 crisis.

Conclusion

The case of Latvia sheds light on various aspects of subordinate financialization at an individual country level. The research shows concrete ways in which FDI, (foreign) banks, and international monetary hierarchies can act as drivers of subordinate financialization. While FDI inflows were a key element to shape the Latvian economic structure during the transition, the banking sector was the key link to engage households and NFCs in the financial sphere, with direct effects on other sectors of the economy such as foreign trade and housing. Furthermore, the role of banks is critical to explaining the exposure of the Latvian economy to the crisis. First, the high rates of domestic indebtedness in foreign currency not only fueled a boom-and-bust cycle, but also increased external vulnerability. Second, the large share of domestic institutions providing offshore services on-demand generated massive flight-to-quality after the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers, which aggravated the country’s balance of payments crisis. Additionally, the subordinated position of the Latvian currency in the international monetary system encouraged borrowers to take credits in foreign currency, promoting critical currency imbalances. Eventually, these aspects were also determinant in the crisis strategy choice. In order to overcome the currency mismatch and secure the repayment of foreign debts, the EU forced the Latvian government to adopt an internal devaluation strategy.

The literature on ‘financial chains’ shows that both foreign and domestic banks acted as the nexus between international financial markets and the Latvian economy, conducting carry trade strategies by channeling the over-liquidity in the global economy into the Latvian private sector. Thus, the Latvian boom was not only a matter of capital flows within the EU, but a reflection of the process of global financialization where Latvia, like many other countries, occupied a subordinated position.

After the GFC there was, however, a notable change in dynamics, and while some indicators of financialization were reduced, other aspects were deepened. In particular, a notable change was observed in the levels of private debt, which contributed to balancing other macroeconomic indicators. To a large extent, these changes were due to tighter controls applied at the national and international level, and a change in profitability conditions for banks, which drastically reduced incentives to lend money. Within this framework, banks resorted to various strategies to restore profitability, including illegal activities. It should be noted, however, that money laundering was not exclusive to domestic banks. On the contrary, foreign banks also became involved in this type of activity, encouraged by the effects of QE policies.

The case of Latvia shows that subordinate financialization is a complex and changing phenomenon. It can undergo cycles of expansion and retreat, affecting different economies, and even different sectors and actors within one economy in different ways. In turn, its progress (or reversal) is the consequence of a multitude of factors taking place at the domestic and, not least, the international level. For the most part, the rolling back of financialization in Latvia occurred beyond the government’s action. Yet, this scenario also suggests that a new financial bubble could occur beyond the government’s control.

Finally, after the GFC Latvia has slowly managed to recover but has not yet established a new sustainable growth model and continues to depend on external capital. This situation poses a concrete question about the near future: how will Latvia cope with its post-pandemic recovery? The experience of the last decades shows that growth driven by (subordinate) financialization will be fragile and unstable, and the risks may far outweigh the benefits. Above all, this lesson can be useful not only for the other Baltic states, but also for the countries of east-central Europe that have similar configurations, especially in terms of dependence on foreign capital inflows, financial integration with the EU, concentration and foreignization of their banking sectors, and in the case of non-eurozone members, subordinated monetary positions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Leonardo Pataccini

Leonardo Pataccini is a Research Fellow at the Department of Geography, Trinity College Dublin and the Department of Global Economics Interdisciplinary Studies, University of Latvia. His main research interests are international political economics, financialization, and post-socialist transitions.

Notes

1. For alternative definitions see Krippner (Citation2005) and Aalbers (Citation2016).

2. Unit Labor Costs are often considered as a broad measure of international price competitiveness. ULCs are defined as the average cost of labor per unit of output produced (OECD Citation2021).

3. Carry trade operations consist of borrowing at a low-interest rate and investing in assets that provide higher rates of return, usually denominated in another currency.

4. After nationalization Parex Banka was replaced by ‘Citadele Banka.’

5. ABLV Banka and PNB Banka provide clear examples of Latvian domestic banks involved in money laundering activities. Both institutions were forced to cease their operations in 2018 and 2019, respectively.

References

- Aalbers, M. B. 2016. The Financialization of Housing: A Political Economy Approach. London: Routledge.

- Aarma, A., and G. Dubauskas. 2011. “The Foreign Commercial Banks In The Baltic States: Aspects Of The Financial Crisis Internationalization.” European Journal of Business and Economics 5: 1–7.

- Ådahl, M. 2002 ”Banking in the Baltics-The Development of the Banking Systems of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania since Independence. The Internationalization of Baltic Banking (1998–2002)“.Focus on Transition 2, 107–131. http://www.oenb.at/de/img/adahl_ftr_202_tcm14-10384.pdf

- Åslund, A., and V. Dombrovskis. 2011. How Latvia Came through the Financial Crisis. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics.

- Ayhan Kose, M., P. Nagle, F. Ohnsorge, and N. Sugawara. 2020. Global Waves of Debt: Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Ban, C., and D. Bohle. 2020. “Definancialization, Financial Repression and Policy Continuity in East-Central Europe.” Review of International Political Economy 28 (4): 874–897. doi:10.1080/09692290.2020.1799841.

- Bank for International Settlements. 2018. “Structural Changes in Banking after the Crisis.” Committee on the Global Financial System Papers 60 (January): 1–119. https://www.bis.org/publ/cgfs60.pdf

- Banka, L. 2020. “Financial Stability Review 2019.” https://www.lb.lt/en/reviews-and-publications/category.39/series.169

- Becker, J., J. Jäger, B. Leubolt, and R. Weissenbacher. 2010. “Peripheral Financialization and Vulnerability to Crisis: A Regulationist Perspective.” Competition & Change 14 (3–4): 225–247. doi:10.1179/102452910X12837703615337.

- Becker, J., and J. Jäger. 2012. “Integration in Crisis: A Regulationist Perspective on the Interaction of European Varieties of Capitalism.” Competition & Change 16 (3): 169–187. doi:10.1179/1024529412Z.00000000012.

- Belfrage, C., and M. Ryner. 2009. “Renegotiating the Swedish Democratic Settlement: From Pension Fund Socialism to Neoliberalization.” Politics & Society 37 (2): 257–288. doi:10.1177/0032329209333994.

- Belfrage, C., and M. Kallifatides. 2018. “Financialisation and the New Swedish Model.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 42 (4): 875–899. doi:10.1093/cje/bex089.

- Bitans, M., and V. Purvins. 2012. “The Development of Latvia’s Economy (1990–2004).” In The Bank of Latvia XC, edited by M. Gulēna and I. Rimševičs, 140–168. Riga: Latvijas Banka.

- Bitans, M. 2012. “Latvia’s Economic Development following the Accession to the European Union: A Classic boom-bust Cycle.” In The Bank of Latvia XC, edited by M. Gulēna and I. Rimševičs, 240–268. Riga: Latvijas Banka.

- Blecker, R. 2005. “Financial Globalization, Exchange Rates, and International Trade.” In Financialization and the World Economy, edited by G. Epstein, 183–209. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Bohle, D., and B. Greskovits. 2012. Capitalist Diversity on Europe’s Periphery. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Bohle, D. 2014. “Post-Socialist Housing Meets Transnational Finance: Foreign Banks, Mortgage Lending, and the Privatization of Welfare in Hungary and Estonia.” Review of International Political Economy 21 (4): 913–948. doi:10.1080/09692290.2013.801022.

- Bohle, D. 2017. “Mortgaging Europe’s Periphery.” LEQS – LSE “Europe in Question” Discussion Paper Series 124. https://ideas.repec.org/p/eiq/eileqs/124.html

- Bohle, D. 2018. “European Integration, Capitalist Diversity and Crises Trajectories on Europe’s Eastern Periphery.” New Political Economy 23 (2): 239–253. doi:10.1080/13563467.2017.1370448.

- Bonizzi, B. 2013. “Financialization in Developing and Emerging Countries.” International Journal of Political Economy 42 (4): 83–107. doi:10.2753/IJP0891-1916420405.

- Bonizzi, B., A. Kaltenbrunner, and J. Powell. 2020. “Subordinate Financialization in Emerging Capitalist Economies.” In The Routledge International Handbook of Financialization, edited by P. Mader, D. Mertens, and N. van der Zwan, 177–187. London: Routledge.

- Bortz, P. G., and A. Kaltenbrunner. 2017. “The International Dimension of Financialization in Developing and Emerging Economies.” Development and Change 49 (2): 375–393. doi:10.1111/dech.12371.

- Bruszt, L., and V. Vukov. 2017. “Making States for the Single Market: European Integration and the Reshaping of Economic States in the Southern and Eastern Peripheries of Europe.” West European Politics 40 (4): 663–687. doi:10.1080/01402382.2017.1281624.

- Büdenbender, M., and M. Aalbers. 2019. “How Subordinate Financialization Shapes Urban Development: The Rise and Fall of Warsaw’s Służewiec Business District.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 434 (4): 666–684. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12791.

- Bukeviciute, L., and D. Kosicki. 2 2012. “Real Estate Price Dynamics, Housing Finance and Related macro-prudential Tools in the Baltics.” ECFIN Country Focus 9. https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/country_focus/2012/2012/cf_vol9_issue2_2012.pdf

- Choi, C. 2020. “Subordinate Financialization and Financial Subsumption in South Korea.” Regional Studies 54 (2): 209–218. doi:10.1080/00343404.2018.1502419.

- Christensen, L., and L. Rasmussen. 2007. “New Europe: A Warning Not to Be Ignored.” Danske Bank Research, February 23.

- Correa, E., G. Vidal, and W. Marshall. 2012. “Financialization in Mexico: Trajectory and Limits.” Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 35 (2): 255–275. doi:10.2753/PKE0160-3477350205.

- Crouch, C. 2009. “Privatised Keynesianism: An Unacknowledged Policy Regime.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 11 (3): 382–399. doi:10.1111/j.1467-856X.2009.00377.x.

- Demertzis, M., and G. B. Wolff. 2016. “What Impact Does the ECB’s Quantitative Easing Policy Have on Bank Profitability?” Bruegel Policy Contribution, November 30. https://www.bruegel.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/pc-20-16-4.pdf

- Demir, F. 2007. “The Rise of Rentier Capitalism and the Financialization of Real Sectors in Developing Countries.” Review of Radical Political Economics 39 (3): 351–359. doi:10.1177/0486613407305283.

- Demir, F. 2009. “Financial Liberalization, Private Investment and Portfolio Choice: Financialization of Real Sectors in Emerging Markets.” Journal of Development Economics 88 (2): 314–324. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2008.04.002.

- Deroose, S., E. Flores, G. Giudice, and A. Turini. 2010. “The Tale of the Baltics: Experiences, Challenges Ahead and Main Lessons.” ECFIN Economic Brief 10: 1–9. https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/economic_briefs/2010/pdf/eb10_en.pdf

- Dreifelds, J. 1996. Latvia in Transition. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Dunhaupt, P. 2016. “Financialization and the Crises of Capitalism.” Institute for International Political Economy Berlin, Working Paper 67: 1–25. https://www.ipe-berlin.org/fileadmin/institut-ipe/Dokumente/Working_Papers/IPE_WP_67.pdf

- Dunhaupt, P., and E. Hein. 2019. “Financialization, Distribution, and Macroeconomic Regimes before and after the Crisis: A post-Keynesian View on Denmark, Estonia, and Latvia.” Journal of Baltic Studies 50 (4): 435–465. doi:10.1080/01629778.2019.1680403.

- Epstein, G. 2002. “Financialization, Rentier Interests, and Central Bank Policy.” Paper presented at the PERI Conference on Financialization of the World Economy, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, December 7–8.

- Epstein, G., and A. Jayadev. 2005. “The Rise of Rentier Incomes in OECD Countries: Financialization, Central Bank Policy and Labor Solidarity.” In Financialization and the World Economy, edited by G. Epstein, 350–378. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Epstein, R. 2013. “Central and East European Bank Responses to the Financial ‘Crisis’: Do Domestic Banks Perform Better in a Crisis than Their Foreign-Owned Counterparts?” Europe-Asia Studies 65 (3): 528–547. doi:10.1080/09668136.2013.779453.

- Epstein, R. 2017. Banking on Markets: The Transformation of bank-state Ties in Europe and beyond. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- European Central Bank. 2016. “How Quantitative Easing Works.” https://www.ecb.europa.eu/explainers/show-me/html/app_infographic.en.html#:~:text=The%20ECB%20started%20buying%20assets,but%20close%20to%2C%202%25

- European Commission. 1999. “Regular Report from the Commission on Latvia’s Progress Towards Accession.” https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/archives/pdf/key_documents/1999/latvia_en.pdf

- European Commission. 2010. “Cross Country Study: Economic Policy Challenges in the Baltics.” Economic and Financial Affairs: Occasional Papers 58 (February): 1–104. https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/occasional_paper/2010/pdf/ocp58_en.pdf

- Farelius, D., and J. Billborn. “Macroprudential Policy in the Nordic-Baltic Countries”. 2016. . Sveriges Riksbank Economic Review 2016:1 .

- Fernandez, R., and M. Aalbers. 2019. “Housing Financialization in the Global South: In Search of a Comparative Framework.” Housing Policy Debate 30 (4): 680–701. doi:10.1080/10511482.2019.1681491.

- Finance Latvia Association. 2020. “Operating Results of Latvian Commercial Banks 1st Quarter 2020.” https://www.financelatvia.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Bank-results-1st-quarter-2020.pdf

- FKTK (Finanšu un Kapitāla Tirgus Komisija). 2008. “Banking Activities in 2008 – General Information.” https://www.fktk.lv/en/statistics/credit-institutions/quarterly-reports/banking-activities-in-2008/

- Gabor, D. 2010a. “(De)financialization and Crisis in Eastern Europe.” Competition & Change 14 (3–4): 248–270. doi:10.1179/102452910X12837703615373.

- Gabor, D. 2010b. Central Banking and Financialization: A Romanian Account of How Eastern Europe Became Subprime. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gabor, D. 2012. “The Road to Financialization in Central and Eastern Europe: The Early Policies and Politics of Stabilizing Transition.” Review of Political Economy 24 (2): 227–249. doi:10.1080/09538259.2012.664333.

- Gabor, D. 2013. “The Romanian Financial System: From Central bank-led to Dependent Financialization.” FESSUD Studies in Financial Systems 5.

- Girón, A., and M. Solorza. 2015. “‘Déjà Vu’ History: The European Crisis and Lessons from Latin America through the Glass of Financialization and Austerity Measures.” International Journal of Political Economy 44 (1): 32–50. doi:10.1080/08911916.2015.1035989.

- Grabbe, H. 2006. The EU’s Transformative Power. Europeanization through Conditionality in Central and Eastern Europe. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Greskovits, B. 2014. “Legacies of Industrialization and Paths of Transnational Integration after Socialism.” In The Historical Legacies of Communism in Russia and Eastern Europe, edited by M. Beissinger and S. Kotkin, 68–89. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Grittersova, J. 2017. Borrowing Credibility: Global Banks and Monetary Regimes. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Gros, D., and C. Alcidi. 2015. “Country Adjustment to a ‘Sudden Stop’: Does the Euro Make a Difference?” International Economics and Economic Policy 12 (1): 5–20. doi:10.1007/s10368-014-0286-7.

- Hilmarsson, H. 2014. “Iceland and Latvia: The Economic and Social Crisis.” Regional Formation and Development Studies 3 (14): 86–97.

- Hübner, K. 2011. “Baltic Tigers: The Limits of Unfettered Liberalization.” Journal of Baltic Studies 42 (1): 81–90. doi:10.1080/01629778.2011.538518.

- Hudson, M. 2014. “Stockholm Syndrome in the Baltics: Latvia’s Neoliberal War against Labor and Industry.” In The Contradictions of Austerity: The socio-economic Costs of the Neoliberal Baltic Model, edited by J. Sommers and C. Woolfson, 44–63. New York: Routledge.

- Hudson, M. 2015. Killing the Host: How Financial Parasites and Debt Bondage Destroy the Global Economy. Petrolia, CA: Counterpunch Books.

- Jacoby, W. 2010. “Managing Globalization by Managing Central and Eastern Europe: The EU’s Backyard as Threat and Opportunity.” Journal of European Public Policy 17 (3): 416–432. doi:10.1080/13501761003661935.

- Jacoby, W. 2014. “The EU Factor in Fat Times and in Lean: Did the EU Amplify the Boom and Soften the Bust?” Journal of Common Market Studies 52 (1): 52–70. doi:10.1111/jcms.12076.

- Jayadev, A., J. W. Mason, and E. Schröder. 2018. “The Political Economy of Financialization in the United States, Europe and India.” Development and Change 49 (2): 353–374. doi:10.1111/dech.12382.

- Johnson, S. 2019. “Sweden Grapples with Housing Market Reform as Risks Mount.” Reuters, December 18. https://www.reuters.com/article/sweden-economy-housing/sweden-grapples-with-housing-market-reform-as-risks-mount-idUSL8N28L43A

- Kaltenbrunner, A., and J. P. Painceira. 2018. “Subordinated Financial Integration and Financialisation in Emerging Capitalist Economies: The Brazilian Experience.” New Political Economy 23 (3): 290–313. doi:10.1080/13563467.2017.1349089.

- Kandell, J. 2009. “Swedish Banks Suffer Baltic Losses.” Institutional Investor, 4 May. https://www.institutionalinvestor.com/article/b150q9whgpvv8z/swedish-banks-suffer-baltic-losses

- Karwowski, E., and E. Stockhammer. 2017. “Financialisation in Emerging Economies: A Systematic Overview and Comparison with Anglo-Saxon Economies.” Economic and Political Studies 5 (1): 60–86. doi:10.1080/20954816.2016.1274520.

- Kattel, R. 2009. “The Rise and Fall of the Baltic States.” Development and Transition 13: 11–13.

- Kattel, R. 2010. “Financial and Economic Crisis in Eastern Europe.” Journal of Post-Keynesian Economics 33 (1): 41–60. doi:10.2753/PKE0160-3477330103.

- Kattel, R., and R. Raudla. 2013. “The Baltic Republics and the Crisis of 2008–2011.” Europe-Asia Studies 65 (3): 426–449. doi:10.1080/09668136.2013.779456.

- Klyviene, V., and L. Rasmussen. 2010. “Causes of Financial Crisis: The Case of Latvia.” Ekonomika 89 (2): 7–27. doi:10.15388/Ekon.2010.0.988.

- Korhonen, I. 2001. “Progress in Economic Transition in the Baltic States.” Post-Soviet Geography and Economics 42 (6): 440–463. doi:10.1080/10889388.2001.10641180.

- Kotz, D. 2011. “Financialization and Neoliberalism.” In Relations of Global Power: Neoliberal Order and Disorder, edited by G. Teeple and S. McBride, 1–18. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Krippner, G. 2005. “The Financialization of the American Economy.” Socio-Economic Review 3 (2): 173–208. doi:10.1093/SER/mwi008.

- Kuokstis, V., and R. Vilpisauskas. 2010. “Economic Adjustment to the Crisis in the Baltic Republics in Comparative Perspective.” Paper presented at the 7th Pan-European International Relations Conference, Stockholm, September 9–10.

- Lahnsteiner, M. 2020. “The Refinancing of CESEE Banking Sectors: What Has Changed since the Global Financial Crisis?” Focus on European Economic Integration, Oesterreichische Nationalbank Q1 (20): 6–19.

- Lane, P. R., and G. M. Milesi-Ferretti. 2008. “The Drivers of Financial Globalization.” American Economic Review (Papers & Proceedings) 98 (2): 327–332. doi:10.1257/aer.98.2.327.

- Lane, P. R. 2012. “Financial Globalisation and the Crisis.” BIS Working Paper 397: 1–34. https://www.bis.org/publ/work397.pdf

- Lapavitsas, C. 2009. “Financialisation, or the Search for Profits in the Sphere of Circulation.” Research on Money and Finance Discussion Paper 10 (May): 1–26.

- Lapavitsas, C., and J. Powell. 2013. “Financialisation Varied: A Comparative Analysis of Advanced Economies.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 6 (3): 369–379. doi:10.1093/cjres/rst019.

- Lapavitsas, C. 2013. “The Financialization of Capitalism: ‘Profiting without Producing.’” City: Analysis of Urban Trends, Culture, Theory, Policy, Action 17 (6): 792–805. doi:10.1080/13604813.2013.853865.

- Luminor. 2017. “The Merger of Nordea and DNB Will Take Place on 1st of October.” https://www.luminor.lv/lv/jaunumi-lidz-2017-10-01/merger-nordea-and-dnb-will-take-place-1st-october

- Lütz, S., and M. Kranke. 2014. “The European Rescue of the Washington Consensus? EU and IMF Lending to Central and Eastern European Countries.” Review of International Political Economy 21 (2): 310–338. doi:10.1080/09692290.2012.747104.

- Marangos, J. 2007. “The Shock Therapy Model of Transition.” International Journal of Economic Policy in Emerging Economies 1 (1): 88–123. doi:10.1504/IJEPEE.2007.015583.

- Medve-Bálint, G. 2014. “The Role of the EU in Shaping FDI Flows to East Central Europe.” Journal of Common Market Studies 52 (1): 35–51. doi:10.1111/jcms.12077.

- Milesi-Ferretti, G. M., and C. Tille. 2011. “The Great Retrenchment: International Capital Flows during the Global Financial Crisis.” Economic Policy 26 (66): 289–346. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0327.2011.00263.x.

- Milne, R., and D. Winter. 2018. “Danske: Anatomy of a Money Laundering Scandal.” Financial Times, December 19. https://www.ft.com/content/519ad6ae-bcd8-11e8-94b2-17176fbf93f5.

- Myant, M., and J. Drahokoupil. 2010. Transition Economies: Political Economy in Russia, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Nissinen, M. 1999. Latvia’s Transition to a Market Economy. Political Determinants of Economic Reform Policy. London: Macmillan press.

- O’Connell, A. 2015. “European Crisis: A New Tale of Center–Periphery Relations in the World of Financial Liberalization/Globalization?” International Journal of Political Economy 44 (3): 174–195. doi:10.1080/08911916.2015.1035986.

- OECD. 2016. “Latvia: Review of the Financial System.” https://www.oecd.org/finance/Latvia-financial-markets-2016.pdf

- OECD. 2019. “OECD Economic Surveys: Latvia.” http://www.oecd.org/economy/surveys/latvia-2019-OECD-economic-survey-overview.pdf

- OECD. 2021. “Unit Labour Costs.” Accessed 15 March 2021. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/unit-labour-costs/indicator/english_37d9d925-en

- OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2000. OECD Economic Surveys: The Baltic States: A Regional Economic Assessment. Paris: OECD.

- Orhangazi, Ö. 2008. “Financialisation and Capital Accumulation in the non-financial Corporate Sector: A Theoretical and Empirical Investigation on the US Economy: 1973–2003.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 32 (6): 863–886. doi:10.1093/cje/ben009.

- Palley, T. 2007. “Financialization: What It Is and Why It Matters.” The Levy Economics Institute Working Paper 525: 1–31. https://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp_525.pdf