ABSTRACT

Despite the growing attention to the everyday, nation-building literature has paid insufficient attention to the ways in which national identity is strengthened as a side effect of measures that are not initially conceived of as nation-building activities. This article examines contemporary examples of such non-traditional processes of nation-building by reviewing the unintended consequences of political measures not directly targeting identity construction. We focus on processes of identity construction in Kyrgyzstan and Estonia that have emerged as a side effect of nation branding. In both cases, the primary goal of the national government was not necessarily to boost national identity but rather to re-brand the country for international audiences. We argue, however, that these efforts at external image projection and change have also influenced the ways in which national identities are understood, perceived, and reproduced by domestic populations.

Introduction: nation-building projects and where to find them

The construction of national identities, in the Baltics as elsewhere, has been regarded from a variety of angles (Bekus Citation2010; Diener and Hagen Citation2013; Fabrykant Citation2018b; Fauve Citation2015; Lõhmus, Lauristin, and Siirman Citation2009; Murzakulova and Schoeberlein Citation2009). A significant amount of work has concentrated on formal political measures intended to foster belonging to a national community. In this respect, nation-making in the Baltics has mainly been examined as a top-down approach that is largely a product of elite manipulation (Fox and Miller-Idriss Citation2008, 554). This existing corpus largely excludes the vital role that ordinary people play in processes of nation-formation, overlooking the turn toward the everyday in nationalism studies more generally. After Hobsbawm (Citation1991) suggested looking at nationalism from below, new studies on micro-processes of nation-building began focusing on the role of individuals and non-state actors in shaping national identity (see Edensor Citation2002; Foster Citation2006; Goode and Stroup Citation2015). Among them, two are particularly relevant to this article: banal nationalism (Billig Citation1995) and everyday nationhood (Fox and Miller-Idriss Citation2008). Fox (Citation2018, 863) distinguishes between these two positions, suggesting that everyday nationhood is both a reproduction of what Billig calls ‘nationalist ideology’ and a reproduction beyond that very ideology. Everyday nationalism, he maintains, can be regarded as distinct from banal nationalism because it is about experiences of everyday reproduction of nationhood related and not related to national ideology. It is about ‘ordinary people doing ordinary things’ and ‘how ideas about the nation are reproduced by ordinary people doing ordinary things in their ordinary lives’ (862–863).

Despite this growing attention to the everyday, nation-building literature has remained mostly silent on possible enhancements of national identity as side effects of measures that were not initially conceived as related to nation-building projects (Pawlusz and Polese Citation2017), including economic and marketing measures such as nation branding (Polese et al. Citation2020). ‘Concerned with a country’s whole image on the international stage, covering political, economic and cultural dimensions’ (Fan Citation2010, 98), nation branding is used to communicate diplomatic or strategic messages (Potter Citation2009) to a variety of external audiences. The national and international, however, are increasingly indivisible in the communications sphere, opening the possibility that newly projected images can be adopted or appropriated by societies as part of their representations and understandings of themselves (see Navaro-Yashin Citation2002; Polese Citation2017; Polese and Horak Citation2015). This approach is grounded in the idea that identities are lived, reproduced, and transformed through everyday interactions (Harvey Citation1989) with other living actors and inanimate objects Lefebvre and Nicholson-Smith (Citation1991); Massey (Citation1995); Ozolina-Fitzgerald (Citation2016). It also builds on Fox’s argument that in banal nationalism, nationalism is taken for granted (it is ‘unseen’ and ‘unnoticed’), whereas, in everyday nationhood, nationalism is evoked and used by people (Fox Citation2018, 864).

Building on this corpus, our article offers a distinct contribution to studying identity construction in the post-socialist region by comparing national branding processes in Kyrgyzstan and Estonia. In both cases, the primary goal of national governments was not to boost national identity but to rebrand the country for international audiences. These countries began at very different starting points. Estonian national identity has consistently been quite well defined and embedded but is often considered exclusive in the sense that non-Estonians have often been excluded from the imagined national community (Galbreath Citation2005; Laitin Citation1998; Vetik and Helemäe Citation2011), and identities are constructed in a Baltic context (Pettai Citation2021; Rakfeldt Citation2015). Such widely criticized exclusionary practices have largely been absent in Kyrgyzstan, but efforts to foster national identity have also been relatively weak (see Huskey Citation2003; McGlinchey Citation2011; Radnitz Citation2010). Both countries, however, engaged in rebranding campaigns that, we argue, affected the way identity is understood and enacted at a societal level and in the political discourse of the country. In doing so, we highlight the potential robustness of these processes across different levels of coherence, strengths of national identity, and state capacities.

The relationship between branding and building is twisted. By branding a country, we can convince international audiences that a country possesses certain features. In turn, by being aware that certain national features are praised and valued abroad, national communities can feel the desire to display these same characteristics. Acceptance of our identity by others is one aspect of how identities are socially constructed and reproduced. In introducing others to a self-fashioned image, we have created of ourselves and/or are convincing others that this image is an authentic representation – that our identity can be reshaped. This is why, building on the idea that many state projects do not end up producing their desired effects (Scott Citation1998), we highlight the gap between the intentions of national elites and the eventual results of their efforts. These findings corroborate previous studies dealing with ‘spontaneous nation-building’ (Polese and Horak Citation2015) that highlight the unexpected and unintended consequences of measures that were not initially conceived to impact national identity, reinforcing the argument that identity construction is a matter of negotiation between the state and its citizens where the everyday merits further examination.

Such micro-level analysis has been recently taken up by researchers studying national identity (Edensor Citation2002; Fox Citation2017; Skey Citation2015) and transplanted into the post-socialist region to produce empirical studies on the role of, for instance, collective singing (Pawlusz Citation2017), food consumption (Polese et al. Citation2020), and fashion and home renovation (Seliverstova Citation2017). Other studies have explored how official and unofficial discourses of national, ethnic, or civic categorizations traverse lifestyles, consumer practices, leisure time activities, and individuals’ engagements with cultural products (Gavrilova Citation2018; Polese et al. Citation2017). This focus on everyday production, reproduction, consumption, performance, and choice-making by ordinary people resonates with Fox and Fox and Miller-Idriss’ (Citation2008, 539) idea that practices of everyday nation-making are reproduced through talking, choosing, performing, and consuming, thus ‘giving ordinary citizens concrete expression to their understanding of the nation.’ People’s everyday choices, for example, by choosing to attend minority schools or not (545), ‘shape’ nationhood. It also chimes with work on consuming the nation (Castelló and Mihelj Citation2018) in terms of music, costumes, food, media, schooling, and shopping practices (Fox and Miller-Idriss Citation2008, 552).

Methodologically, this article adopts a mixed-method approach. In both cases, the material presented is derived from primary sources, including a total of 35 in-depth interviews in Estonia and Kyrgyzstan. Respondents included kok-boru players, restaurant owners, marketing specialists, business analysts, and people working in the art business.Footnote1 These interviews were complemented by a study of the main nation branding materials created by the Estonian and Kyrgyz national governments, including an analysis of government websites, tourist brochures, and other government documents and publications (listed in the references), as well as informal discussions with marketing specialists that contributed to each nation branding strategy. The following section provides an overview of the central debates on national identity, distinguishing between state and statist narratives and a more recent body of literature looking at the everyday. It is followed by two case studies, the first on Kyrgyz and the second on Estonian identity constructions.

The loci of national identity

Initial debates on nation-building and identity construction have devoted particular attention to macro-efforts or events that could shape the collective identity of a community or a nation (Gellner Citation2008; Smith Citation1986). These could happen as unintended consequences of historical legacy or result from an elite-driven societal engineering project, whereby a given identity is attempted to be inculcated into a given population, or part thereof (Deutsch and Foltz Citation[1966] 2010 [1967]). Such an approach includes a diversity of modes and tools that can be used for nation-building and can be analyzed as an overarching project or deconstructed and examined one by one (for example, language policy, educational curricula, or integration policies). Two major dichotomies, however, have emerged over time. The first dichotomy contrasts state versus society-centered nation-building measures. Statist perspectives on identity construction prioritize the role of governing elites, institutions, and generally, the state in all its expressions, assuming that society will follow and that top-down approaches are the main determinants of a successful nation-building project. Bottom-up approaches consider the role of non-state actors in accepting, rejecting, or renegotiating identity markers proposed by the elite. The second is considered in terms of formal versus informal nationalism (Eriksen Citation1993; Pawlusz Citation2017; Strzemżalska Citation2017). It looks at the way the role of the state can be active (proposing measures), but also passive in letting some markers emerge from societal tendencies (Menga Citation2015; Morris Citation2005; Ó Beacháin and Kevlihan Citation2013). By ‘not fighting’ the spread of a given habit and not interfering with societal processes, a state could contribute to a nation-building project (Fabrykant and Buhr Citation2016; Isaacs Citation2015; Isaacs and Polese Citation2015).

Overall, nation-building and identity formation can be regarded as part of a synergy between elite forces providing ‘instructions’ on identity markers to choose and bottom-up (or informal) processes in reaction to these instructions. In many cases, renegotiating identity, selecting markers, and performing identity happen in ways that are not necessarily of great interest to state institutions (Fauve Citation2015; Polese et al. Citation2017). In our view, however, the current literature offers a limited understanding of the role of non-formalized actors, partly because they are more difficult to measure or notice (Rudé and Hobsbawm Citation1968). Nevertheless, their role seems to be of the utmost importance when these same actions are repeated millions of times, day in and day out (Scott Citation2014). Indeed, as Scott stated a few years before:

So long as we confine our conception of the political to activity that is openly declared we are driven to conclude that subordinate groups essentially lack a political life or that what political life they do have is restricted to those exceptional moments of popular explosion. To do so is to miss the immense political terrain that lies between quiescence and revolt and that, for better or worse, is the political environment of subject classes. It is to focus on the visible coastline of politics and miss the continent that lies beyond. (Scott Citation1990)

As a result, processes initiated by local and bottom-up actors, once the number of actors becomes higher, come to have political significance. They can be seen as an indicator of the success of a given policy or measure, but can also nullify the work of political institutions. Formal actors may offer instructions and modes of interpreting them. Nevertheless, one should also consider unrecognized, unnoticed, and non-formalized actors who behave in a way that is often defined as informal or spontaneous, and who undergo a process of redefining national identity so that it is more in line with what the people themselves ‘want.’ This is of utmost importance. Every day each individual faces many choices, from the mundane to the more fundamental. By choosing to consume a certain product or not, we perform and reproduce identity (Douglas and Isherwood Citation1996; Fox and Miller-Idriss Citation2008) to the point where these apparently insignificant actions may affect the capacity of a state or a political elite to construct or influence national identities (Doğan Citation2013; Goode and Stroup Citation2015; Jones and Merriman Citation2009). Thus, identities are performed through visible and consolidated actions; they are reproduced and spread through hidden, subconscious, and/or unperceived dynamics (Isaacs and Polese Citation2016). This approach informs the definition of spontaneous nation-building, which is one of our departing points as either performed by some segments of the population ‘spontaneously’ and or without input from national elites. Or else, resulting from some political measures that were not meant to impact identity construction but ended up, in fact, doing so (Polese and Horak Citation2015).

Billig’s work is also useful as it enables us to claim the role of agency in major socio-political processes. This point can be related to several other scholars (Hart and Risley Citation1995; Lefebvre and Levich Citation1987; Lefebvre and Nicholson-Smith Citation1991; Shotter Citation1993), who examine quotidian and ‘banal’ practices which are often performed unconsciously or with little awareness of their macro and long-term consequences. We live in a world of nations in the daily life and consciousness of people (Thompson and Ralph Citation2003). Such approaches have allowed scholars such as Michael Skey (Citation2009) and, more recently, Jon Fox (Citation2017), to hypothesize that people are not homogeneous and passive receivers of banal nationalism, and instead consume and experience their national identities in a variety of different ways. This approach emphasizes that ‘states are peopled’ (Jones Citation2007). This tendency has been partly addressed in the reflections of Fox and Miller-Idriss (Citation2008) and then Fox (Citation2017) on the theoretical ‘turn to the everyday’ in identity studies. Banal nationalism can thus be a good starting point, but also risks overlooking the role of an individual in reproducing the nation (Antonsich Citation2015), contrasting the state’s desire to uniformize and standardize and its people’s desire to be treated as an individual (Scott Citation1998). In this respect, scholars have explored different layers and modalities of identity constructions, including Edensor (Citation2002) and Foster (Citation2002), who look at how mundane and banal practices end up reinforcing a given idea of identity or the nation. Skey (Citation2011) also draws from this vein of research in introducing the concept of ‘ecstatic nationalism’ and the need to conceptualize new theories and tools for studying national identity. His call has been echoed by works on identity in the post-socialist region (Bassin and Kelly Citation2012; Fabrykant Citation2018a; Harris-Brandts Citation2018; Isaacs and Polese Citation2015; Polese and Horak Citation2015).

In the post-socialist region, scholars have approached the role of human agency from many angles (Buhr, Fabrykant, and Hoffman Citation2014; Isaacs Citation2018; Kolstø Citation2016; Mole Citation2012), as well as work on the roles of schoolteachers and administrators in renegotiating an official narrative of national identity at the local level (see Janmaat Citation2000; Polese Citation2010; Richardson Citation2008; Rodgers Citation2007). The unintended consequences of state-led artistic support (Isaacs Citation2018; Menga Citation2015; Militz Citation2016; Strzemżalska Citation2017), as well as the emphasis put on national heritage, national food, or other national features, promoted through advertising (Fabrykant Citation2018a; Gavrilova Citation2018; Seliverstova Citation2017), has also been examined by a range of authors. These studies draw from empirical evidence to challenge the assumption that nation-building is mostly a top-down process. Identity markers or even ‘the construction of the political’ (Navaro-Yashin Citation2002) do not necessarily come from state or political actors alone (Polese Citation2017; Polese and Horak Citation2015).

Nation branding nicely fits this category of unintended and non-state-led actions. Although initially regarded as an economic and marketing measure (Anholt Citation2007), it can be examined through a nation-building lens. While it intentionally targets international audiences, it also, in the process, (re)focuses national narratives on a pre-selected set of values and features that a society, or its elites, would like the world to notice (Fan Citation2006, Citation2010; Gudjonsson Citation2005; Kaneva Citation2011; Volcic and Andrejevic Citation2011). Nation branding conveys a message directly to international publics that are less sensitive to certain issues and are less likely to criticize and challenge the narrative constructed by that given country, functioning as a supplement to interstate diplomacy in seeking to establish or strengthen a state’s legitimacy or influence its geopolitical positioning (Browning and Ferraz de Oliveira Citation2017, 490). The Czech Republic, for example, repeatedly noted that Prague was geographically further west than Vienna as part of its ‘return to Europe’ narrative (Praha Citation1998).

Furthermore, branding can be used more reactively to compensate for or overcome something perceived domestically as harmful to the state’s reputation (Aronczyk Citation2013, 16Jansen Citation2008, 124). It can also generate ‘positive foreign public opinion that will “boomerang” back home, fostering both domestic consensus or approbation of their actions as well as pride and patriotism within the nation’s borders’ (Polese et al. Citation2020). Indeed, there is a substantial difference between listening to political messages and to those enhancing the qualities of the country where you live. As the cases below will illustrate further, this shift from nation branding to nation-building can significantly affect national self-perception.

Kyrgyzstan’s grand business and investment project: the World Nomad Games

Kyrgyzstan has experienced weak national ideology, political corruption, and clan-based rule since its independence in 1991 (McGlinchey Citation2011; Radnitz Citation2010). In its 30 years of independence, the country has undergone three violent leadership changes in 2005, 2010, and 2020. The violence of 2005 and 2010 were followed by inter-ethnic clashes and looting that further hampered the country’s economic development, resulting in volatility and uncertainty for business sectors that putting foreign investment at risk. Hence, one of the primary tasks of the post-2010 administration was improving the international image of Kyrgyzstan by advertising the state as a safe investment destination and a nomadic tourist center. The political leadership of Kyrgyzstan aspired that the country would be associated with nomadic culture, mountains, and Lake Ysyk-Köl. The nomad games were particularly perceived domestically as Kyrgyzstan’s ‘business card’ (Sheranova Citation2021). This resulted in the creation of World Nomad Games (WNGs) (in Kyrgyz: Duinoluk Kochmondor Oiundary; in Russian: Vsemirnye Igry Kochevnikov – VIK). Advertised as a nomadic version of the Olympic Games, the games feature up to 37 different nomadic sports, including hunting, horse riding, horseback games (kok-boru, archery, kunan-chabysh, zhorgo-salysh), wrestling, arm-wrestling, nomadic intellectual games, and others. The WNGs were announced by President Almazbek Atambaev in 2012 in Bishkek during the summit of the Turkic Council. Since then, three nomad games have been hosted in Kyrgyzstan: in 2014, 2016, and 2018. The games received substantial support from local sponsors and international actors, including the United Nations (through UNESCO). below presents detailed information on the three WNGs held in Kyrgyzstan between 2014 and 2018.

Table 1. The World Nomad Games in numbers. Source: Sheranova (Citation2023), 1 Kyrgyz som = 0.15 USD (2016).

The WNGs served several functions. Officially, it was designed by the Kyrgyz state leadership to revitalize, preserve, and develop world ethno-cultures and to promote international tolerance and diversity. Unpinning the design was a desire to develop international tourism and increase foreign investment in Kyrgyzstan. The Kyrgyz authorities used the WNGs as a global platform for demonstrating local culture, traditions, and history to promote international tourism and investments in Kyrgyzstan. All three WNGs were, for instance, accompanied by ethno-cultural activities in a Kyrchyn zhailoo (summer pasture) ethno-village in Ysyk-Köl. A picturesque mountain location was chosen to demonstrate the beauty of Kyrgyz nature to international guests. Dozens of urts/boz uis with tables inside laden with food welcomed international guests, tourists, and official delegations in a show of local hospitality.Footnote2 Ethno-cultural activities in the Kyrchyn Valley demonstrated Kyrgyz national customs and traditions, starting from the birth of a child up to marriage. Kyrgyz traditional handcrafts, clothes, cuisine, songs, and dances were also displayed, together with those of other participating cultures.

Overall, the government’s effort to attract foreign spectators and visitors to the WNGs was enormous. The Kyrgyz authorities accredited as many foreign media outlets as possible to cover the games. By 2018, during the third WNGs, 58 foreign media outlets were accredited. The authorities also developed special promotional videos about the games. They promoted them through the official WNGs social media pages on YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, VK, and Odnoklassniki.Footnote3 A user-friendly World Nomad Games website available in English, Russian, and Kyrgyz languages contained all the relevant information about the WNGs, including the history of its creation, programs, contact information, visa and ticket information, volunteering, and local traditions and customs. In addition, a special mobile phone application was developed to guide international guests. A special state body called the Secretariat was responsible for organizing the WNGs and operating social media tools to advertise the scheduled games and events.

The Kyrgyz authorities also undertook great efforts to attract world celebrities to the opening events to create ‘globalized entertainment’ (Adams Citation2010, 4) and spectacular shows. The second WNGs, for instance, featured the Hollywood star Steven Seagal, which made the opening ceremony especially memorable. During the opening ceremony of the second WNGs, 1,000 komuz (instrument) players simultaneously performed the melody Mash Botoi creating a unique national show (Kyrgyzstan, Citationn.d..). Finally, legislative measures were adopted to promote international tourism. The Kyrgyz government introduced a visa-free entrance policy for most foreign countries, with the Kyrgyz parliament adopting a special law on 60-day visa-free entry for 51 countries in 2012 (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kyrgyz Republic Citation2019).

State officials believed the project was hugely positive from a marketing perspective for the country and contributed to increased international tourism. Askhat Akibaev, the creator of the World Nomad Games and a former governor of Ysyk-Köl region, stated that after the games, ‘most tourists recognized the country not by its name, but by the Nomad Games. If in 2011–2012, the number of international tourists who visited Kyrgyzstan was 2.2 million people, in 2016, it was 4.2 million. Huge revenues in tourism were mostly achieved due to the Nomad Games’ (Azattyk Citation2018b). In a similar way, the interviewed members of the WNGs Secretariat, a specially assigned state body, acknowledged that the WNGs made Kyrgyzstan more prominent. The country became positively associated.Footnote4 The head of the Secretariat confessed in 2021 that before the WNGs, Kyrgyzstan was notoriously linked with negative images such as bride-kidnapping, revolutions, conflicts, and drug trafficking.Footnote5 He believed that the situation had significantly changed since then. Another research study featured in a media outlet in 2018 confirmed that Kyrgyzstan’s image had significantly improved since the first WNGs in 2014. As the piece noted, of 368 foreign articles about Kyrgyzstan published between 2011 and 2013 that were included in the study, 75% were negative in their content, with only 8% described as positive. After the WNGs, however, the percentage of positive articles analyzed in the 2014–2016 period increased to 29%, and the number of negative articles decreased to 51% (Azattyk Citation2018a). The available evidence, therefore, points to the positive trajectory of the national branding strategy among international audiences. The section that follows will consider the games’ domestic impact.

Everyday performing and consuming of nomadic nationhood in Kyrgyzstan

Fox and Miller-Idriss (Citation2008, 540) argue that sporting events, along with wars and other kinds of crises, ‘provide important contexts for everyday articulations of the nation.’ The World Nomad Games inspired local spectators to admire the nomadic past and to perform nomadic culture in their everyday lives.Footnote6 These ideas were largely induced by the efforts of non-state actors, such as public foundations, private entrepreneurs, businesspeople, and individual politicians. These actors played a tangible role in maintaining and strengthening a ‘new’ national identity in Kyrgyzstan stimulated by ideas of nomadism. Nomadic trends or identity markers are especially evident in the mass consumption of the kok-boru game among ethnic Kyrgyz men across post-WNG Kyrgyzstan.

Mass performance and consumption of the kok-boru horseback game

Kok-boru rapidly became the most exciting and spectacular game during all three World Nomad Games, with matches at the epicenter of public attention. In particular, the matches between Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan were compared to football’s El Clasico (the famous matches between rival clubs Barcelona and Real Madrid in Spain). Internationally, the game became known as a Kyrgyz ethno-game largely due to a 31-minute episode featuring kok-boru on Netflix’s Home Game Series. The show featured a final match between two prominent Kyrgyz teams at the newly constructed hippodrome in Cholpon-Ata for the occasion of the World Nomad Games. Spectacular performances during the game very soon made it a special sport in the hearts of many ‘Kyrgyzstanis.’Footnote7 Interviewed players and representatives from the Kok-Boru Federation of Kyrgyzstan (hereafter referred to as the Federation) stressed that following the WNGs, kok-boru was ‘reborn’ and ‘revitalized.’Footnote8 Earlier it was played predominantly in rural areas by rural youth; today, however, it is also played by urban youth. Currently, there are about 20 official teams in Kyrgyzstan. Some of the teams and players became famous after the WNGs. They opened social media channels, such as Instagram pages, Telegram channels, and distributed official WhatsApp numbers. Yntymak (one of the three strongest teams in Kyrgyzstan, a three-time winner of the WNGs, and a six-time winner of the President’s Cup), for example, has more than 76,000 followers on its official Instagram page. The team also has a fan account with more than 80,000 followers. Another team based in the region of Chui called Sary Ozon has more than 87,000 followers on its Instagram page. These teams update their followers on the latest developments within their teams, inform them about scheduled game dates, share photos and videos of their matches, highlight game-related news, and post commercial advertisements. The matches these teams posted received over 10,000 views and hundreds of comments. Overall, the WNGs made kok-boru a very popular sport associated with Kyrgyzstan and Kyrgyz identity. In other words, if you play it – you certainly become Kyrgyz. Non-Kyrgyz nationals born in Kyrgyzstan, especially ethnic Russians, became popular through playing kok-boru first as amateurs and later by forming a professional team (Sport Citation2019). Atuul, a team formed solely by ethnic Russians, participated in national tournaments and has been referred to as ‘Kyrgyz by soul,’ hinting at the fact that performing the kok-boru game professionally could somehow make up for poor Kyrgyz language skills and/or other in-group characteristics and be used as an identity marker to ‘make you more Kyrgyz.’

The popularity of Alaman ulak – a less professional version of the kok-boru game, was also boosted by the emphasis placed on the WNG. It became more popular with ordinary citizens at private ceremonies, such as childbirths, jubilees, feasts or toi, and other occasions.Footnote9 Usually, every week from autumn to summer, local people perform kok-boru tournaments as part of various feasts featuring a major prize, including cars, horses, cows, gold, or cash. The private feast games attract players from neighboring villages, towns, and even countries who come to compete for the main prizes within small teams or as individual players. In one village-level alaman ulak, up to 500 men on horseback can become involved in a game (with around 30–40 players coming from each village).Footnote10 In district-level or regional-level games, the number of players on horseback can exceed 1,000 people. The village of Kyzyl-Too in the Ozgon district holds, on average, five or six alaman ulaks annually, with competitors drawn from among the local population.Footnote11 Other official accounts also support the view that kok-boru became famous after the games. According to the Minister of Culture, Information, Sport, and Youth Politics of Kyrgyzstan, interest in kok-boru dramatically increased in the wake of the WNGs:

Kok-boru had drawn the attention of many after the games. It started to be played in league format like in football. In villages, even little school children play this game because they were very much impressed by the WNGs. Kok-boru also became more known internationally. Other countries like Turkmenistan, Iran, and the United States became interested in it.Footnote12

While the state promoted the sport, its domestic popularization and mass consumption would not be possible without non-state actors, including public foundations, private entrepreneurs, businesspeople, and individual politicians. It was foremost a non-state public foundation – the Federation and their partners (entrepreneurs, businesspeople, and individual amateur politicians) – who played a key role in everyday performances of the game at stadiums or hippodromes, and its popularization through social media. The state sponsors only supported a few official tournaments by organizing food and accommodation for players and by providing a prize fund. As the federation’s general secretary put it:

Kok-boru is a very expensive sport, and the state cannot afford its maintenance and development. We seek sponsors among businessmen and kok-boru devotees to support teams in Kyrgyzstan. In a team consisting of 12 men, there are 12 horses that need to be properly fed. We buy expensive vitamins for horses to keep them in good shape. Prior to a tournament, we collect and train teams.Footnote13

The state does not have a separate budget for the development of kok-boru apart from symbolic prize funds for the winning teams, which range up to 500,000 KGS, while the quality of state-owned hippodromes is generally poor.Footnote14 Likewise, existing teams do not receive any support from the state. Teams are typically maintained through support from businesspeople and rarely by community members. Prominent businesspeople and politicians, such as national parliament members, are generous sponsors of this sport. They establish and maintain teams, buy horses, hold competitions, and issue prizes for winners.Footnote15 Teams who fail to find sponsors usually disintegrate, as illustrated by the demise of the Kelechek team in 2020. The Federation also provides financial assistance to domestic teams taking part in competitions.

The Federation also promotes the sport domestically and internationally through social media and international partners. It has an Instagram page with more than 45,000 followers (as of October 2022), a YouTube channel with almost 16,000 followers, and an official Twitter account. As the general secretary of the Federation acknowledged, they launched their social media pages in 2014 on the eve of the first WNG in order to get more visibility and popularize kok-boru not only in Kyrgyzstan but also internationally.Footnote16 They encouraged teams in Kyrgyzstan to open and manage their official accounts on social media in order to promote the sport further. The Federation also initiated the production of a documentary film in 2021, reportedly to promote, preserve, and restore a tradition of kok-boru and to foster patriotism among the youth (Makanbai Kyzy Citation2021).

The relationship between the state and the people regarding the games, and particularly with respect to kok-boru, is deeply entangled. While the state promotes the sport, there are limits to what it can finance. In turn, surfing on the sport’s popularity, performers and organizers can benefit from growing support. As a result, the Federation, businesspeople, and individual amateur politicians became key actors in cultivating nomadic culture and identity through the production, popularization, and maintenance of kok-boru both domestically and globally. Captured by a nomadic idea of nationhood, ordinary people began to actively interact with nomadic sports, particularly kok-boru. Kok-boru suddenly became a source of national pride. For many Kyrgyzstanis, this game represents a way to express their belonging to a Kyrgyz identity. This Kyrgyz identity is inclusive of all who play kok-boru. Ethnic Russians born in Kyrgyzstan, for instance, who play professionally in one of the national teams have been praised and called ‘real Kyrgyz’ by ethnic Kyrgyz kok-boru spectators and commentators alike (Sport Citation2019).

Through efforts to re-brand and communicate abroad what Kyrgyzstan and Kyrgyz are, the WNGs project has also shaped the Kyrgyz identity. The mechanisms triggered are similar to others that have generated non-state identity markers. On the one hand, we have some more standard ethnic identity markers already identified in the literature on the nationalism of the eighties (Gellner Citation2008; Smith Citation1986), such as language, historical memory, and the very perception of a nation. On the other hand, however, some elements of civic nation-building emerge from using certain discourses or tools. These markers are associated with behaviors and attitudes toward symbols, events, and traditions promoted by the state but reinforced and amplified by societal actors.

A (snow cold) warm welcome from Estonia

We are what we pretend to be, Kurg Vonnegut wrote in his novel Mother Night. The leading feature of Estonian identity construction has been its capacity to act indirectly on the local population. Since the very early 2000s, the Estonian state has worked hard and invested a great deal of resources into promoting the country at the international level. Despite efforts to engage in formal nation-building, a great deal of identity construction in Estonia, especially its most inclusive components, does not come from the state but through people’s attitudes or reactions to measures initially promoted by the state with goals other than nation-building. This is due to the specific composition of the country, where Russian speakers make up almost one-third of the population and they often feature a hybrid identity including, according to Laitin (Citation1998), a sense of abandonment from ‘the motherland,’ but also a strong relationship with the place they are born. Several informants highlighted that, despite being Russian, they could not see themselves living in Russia. More than once informants explained that it is indeed upsetting to see some official discourses based on the idea that Russians ‘do not belong here’ (this is especially the case of the official discourse of nationalist parties) and that the requirements to know Estonian language have become stricter especially in some industries. Ultimately, however, they could not imagine having access to the same opportunities (labor market, house, medical care) in what is allegedly their motherland (Polese et al. Citation2017).

Nevertheless, with a population of 30% who do not self-identify as Estonian and a significant distance between the Estonian language, culture, historical memory, and minority groups, extreme manifestations of ethnic Estonianness are not likely to encourage positive inter-ethnic relations in the country (Ehala Citation2009). In this respect, the value of the Estonian identity construction strategy has been its foreign focus. It can be characterized as an effort to gently convince others about who they are to convince themselves that what foreigners think is the truth. As in many other cases, this strategy has not come directly from a well-planned nation-building project but is rather the byproduct of a nation branding strategy aimed at attracting international attention (and thus tourists and investors) to Estonia (Polese et al. Citation2020).

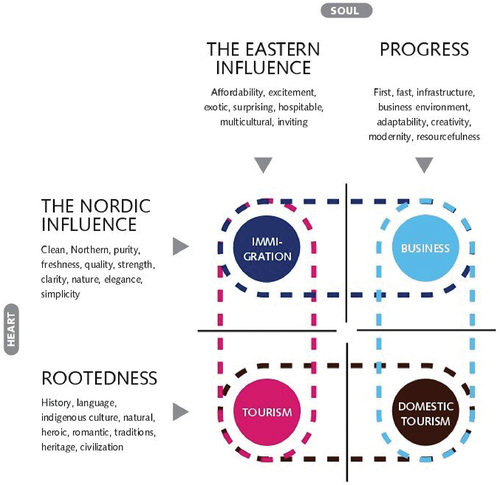

The strategy features efforts to ‘de-Sovietize’ Estonia that, in some cases risk parody – such as proposing that some popular activities such as jam making, or that unrenovated flats, belong, against all evidence, to the Soviet past (Polese et al. Citation2018). The ultimate goal, however, is to convey a message to potential investors that Estonia is an attractive destination and a stable country for foreign guests, as well as to promote services and advantages that everyone can benefit from, starting from foreigners but, of course, also including the local population. To increase the country’s foreign investment and tourism bases while broadening the scope of Estonia’s export market (Dinnie Citation2008, 230), Enterprise Estonia has been, since the 2000s, promoting business all over the country through financial support, advice, and training. Reaching a budget of over €81 million in 2019, it had come a long way from when it was a simple agency using the 2001 Estonian Eurovision Song Contest victory to make the country visible and attractive to investors (Polese et al. Citation2020). This event was possibly the first big milestone for Estonia and the agency sought to capitalize on the win to make the country more tourist-friendly, invest in infrastructure, and generally sell its image as a quiet, friendly, and safe, yet still exotic, destination to discover. The strategy revolved around the valorization of the country’s geographical location, at the crossroads between an imaginary east (Russia), west (Europe), and north (Scandinavia), that would also present Estonia as a hub between cultures preserving its ‘original’ culture and its ‘Europeanness’ (Lauristin Citation2009; Lauristin and Vihalemm Citation2009), as emphasized in the ‘Introduce Estonia’ brochure by Enterprise Estonia (see ).

The slogan chosen for the promotion of the country, ‘Welcome to Estonia: Positively Transforming,’ could be regarded as composed of a logo showing that everyone is welcome and a transforming (from the Soviet past) component (Dinnie Citation2008, 233). The country’s multicultural influences are also stressed:

By geographic location, we belong in the Baltic region. By language, we belong in Scandinavia. By allies, we belong in Europe. By the prevailing religion, we belong in Germany. By history, we belong in Sweden, Denmark, Livonia, and Russia. By climate, we belong in the North. (Enterprise Estonia Citation2012b, 3)

The word ‘Nordic’ has often been used to move Estonia geographically away from eastern Europe and even from the Baltics in people’s imagination. The ‘North’ (Jordan Citation2014a, 290) is a particularly important word as it can be regarded as an attempt to relate to Scandinavia, casting a shadow on the country’s geographical location in the Baltics and an attempt to associate its normality with anything which was ‘not Soviet’ or ‘not Communist’ (Eglitis Citation2002, 8). It also hints that its territory was and still is a real hub of civilizations, as romantically described by the statist Lennart Meri (Citation2016 [1976]) in his book Hõbevalge (Silver White):

Our bones are from the East and our flesh from the West, but this is as difficult to describe as the splitting of a personality after the separation of the two hemispheres of the brain. There were no people in Central Sweden when we landed on these shores to fish and set traps. We spoke our own language, of which we have retained about a thousand words, and these are still understood along the banks of the Volga and Pechora and beyond the Ural Mountains. A thousand words is not much in terms of modern vocabulary but during the Stone Age? As you can see, it was enough for us…. (Meri as quoted in Enterprise Estonia Citation2012a, 3)

In addition to generating an image of hospitality and safety, the branding strategy promoted effectiveness by capitalizing on the decision to install the European Union Agency for the Operational Management of Large-Scale IT Systems in the Area of Freedom, Security, and Justice (eu-LISA) in Estonia. Promoting the country as ‘northern Europe’s hub for knowledge and digital business.’ Since investments and companies need a workforce, a sister website titled ‘Work in Estonia’ (In Estonia Citation2020) was created to help attract foreign workers to ‘Northern Europe’s knowledge hub in tech;’ the website states that if you are an innovative worker, you should ‘come work in Estonia to accelerate your career.’ The above narrative of Estonia as ‘Nordic’ was then narrated through a myriad of small but significant actions to convince potential investors and businessmen that Estonia is worth their attention. World-leading companies started emerging because of these investments, but also due to the favorable business climate created. Indeed, from Skype to Transferwise (now Wise), the country has managed to mitigate the widely criticized Estonian nationalism of the 1990s and propose alternative ways to contribute to society and, eventually, citizenry (Jašina-Schäfer and Cheskin Citation2020).

Further in this direction, the development of the business environment in Estonia has benefited from a strongly inclusive approach. Also, in this case, the primary desire was not necessarily to secure cohesion at the national level (and thus enhance the integration of Russian speakers) but to invite everyone to the virtual business environment, which has ended up benefiting the non-Estonian parts of the population, both directly and indirectly. Since the introduction of the e-residency program in 2014 and the complete digitalization of public administration, it has become extremely easy to establish and manage any kind of business in Estonia, with over 50,000 business activities officially registered under the program in addition to the enhanced business opportunities for standard Estonian residents that have access to an accessible Estonian business management environment.

Consuming identity in Estonia

The business environment is not the only way Estonian identity construction has been visible, as is evident from a survey of recent studies on Estonia. Framed in a broader context of an everyday framework for the study of identity in the post-socialist region, a number of actions, from school policy to house renovation to exhibitions (Polese Citation2019), have been regarded as significant to spread or redefine national identity (Polese et al. Citation2017, Citation2018). They have conveyed the idea that identity building is not always caused by clear identity policies by institutions. Instead, transformation has happened through vibrant interaction with local spaces (Jašina-Schäfer and Cheskin Citation2020) and mundane activities such as the consumption of luxury (Polese and Seliverstova Citation2019). Language acceptance has also been fostered by cultural initiatives such as collective singing (Pawlusz Citation2017).

Food has emerged, in this respect, as a more contested territory than business for the reproduction of national identity. This is understandable. A narrative proposing a better business environment, especially if followed by concrete political measures, is going to benefit virtually everyone. In contrast, a narrative proposing a certain interpretation of food practices according to a constructed narrative is not always easily adopted by all targeted groups. At the source level, several narratives have been defined, for instance, through the establishment of a food museum and the promotion of national(istic) recipes, foods, and modes of food production. The Estonian Ministry of Rural Affairs’ affiliated website ‘Estonian food’ defines Estonian food as ‘a tasty reflection of thousand-year-old traditions, pure nature and smart producers’ (Republic of Estonia Ministry of Regional Affairs and Agriculture Citation2020), contributing to the imagination of national food ingredients, symbols, and practices with which Estonian citizens might associate themselves and through which the imagination of the Estonian nation might be facilitated. In contrast to Soviet practices of mass-production and industrialization, in this case, Estonia is depicted as a country of small family businesses producing high-quality products (Polese et al. Citation2020). Emphasis is placed on direct ‘producer to consumer’ production chains and frequent use of words such as natural, healthy, and genuine, as well as attempts to follow the latest fashions in world food trends (for example, eat seasonal, eat local, eat bio, the Zero Kilometer trend), all of which is intended to stress the relationship of Estonians with their food, land, and nature in general. The quote below from an official website promoting Estonian food illustrates this:

Estonians have always loved to grow different kinds of roots, tubers, vegetables, fruit, and berries. As most of the population lives in urban areas with little space for garden plots, then options such as growing fruit trees in the backyards of apartment block buildings, little urban greenhouses, and growing simpler vegetables on windowsills are gaining popularity. (Republic of Estonia E-Residency Citation2020)

Another ‘All Estonian’ feature is, it seems, the capacity of national producers to find a balance between care for every single product and the affordability and accessibility of such products, as shown in the bread section from the same website:

The first Estonian bread industries were established already in the nineteenth century, and Estonia’s oldest bread industry, Leibur, is already more than 250 years old. The industries today manufacture around 90% of the entire Estonian bread production, however, the number of small bakeries and farms whose produce ends up on supermarket shelves is also on the rise, as they offer variety. (Republic of Estonia E-Residency Citation2020)

So, food may be produced industrially and by small farms, but in both cases, some maternal care is applied to all products that should, thus, be regarded as genuine and ‘truly Estonian.’ This overemphasis on ‘Estonianness’ provides an entry point of sorts for the integration of other communities. The website, and in general, food narratives such as recipe books or even single products, emphasize the place of production, but pose no limits to the range of actors (or their ethnic origins) involved in the process. As a result, their definition of ‘patriotic consumption’ (Polese and Seliverstova Citation2019) and production principally relies on respect for national standards and acknowledgment of the modes and places of production, leaving sufficient room for negotiation. Who the producers or the consumers are loses importance to how they acknowledge Estonia as the place where all this happens. By force of this, the official discourse, or at least one of the official discourses of the country, shifts, thus opening the gates to non-Estonians behaving in an Estonian way.

The same can be said for the production of national foods that are labeled as ‘natural’ or ‘genuine,’ and often resemble the national flag in their packaging (using blue, white, and black coloring extensively). Food is there to be consumed, and being natural enhances the pride of those who identify with products from the territory that produces such foods and thus with markers that are not necessarily ethnic. Such private sector attempts to match state narratives on food, its production, and its marketing open the door to ‘de-exclusivizing Estonian-ness’ (Polese et al. Citation2020). Performing ‘Estonianness’ becomes, therefore, the act of producing, consuming, or promoting foods that are seen as embodying the essence of the country. Against ethnonationalist narratives, such moves mean that, at least in theory, you can feel a bit more Estonian by praising or promoting your national production or the genuineness of Estonian foods.

The Estonian modernization of recipes has benefited from the momentum of the health food industry, in which buckwheat (in Estonian, tatar), widely used in Estonian cuisine, has been praised as good for one’s body. Likewise, attempts to associate Estonia with innovative cuisine and recipes, connected to an emerging ‘Nordic cuisine,’ promotes the idea of Estonia as traditional, modern, and Nordic all at once (Jordan Citation2014a). This initiative has been accompanied by attempts to distance Estonia from Soviet-style cooking through the ‘nationalization’ or ‘modernization’ of Soviet ingredients or dishes, from solyanka and borshch to pelmeni. This sometimes led to the construction of twisted narratives in the respondents’ responses. The existence of homemade products is either denied because they are associated with the Soviet past (for example, homemade jams and pickles; see Polese Citation2019), or they are changed in significance and meaning, as, for instance, when they are modernized or mentioned as expressions of modernity and the desire to eat ‘genuine’ food (Republic of Estonia E-Residency Citation2020; see also Polese et al. Citation2020). They can also be re-labeled as expressions of cultural specificities:

Few people make things at home, including alcohol. The only people who engage with such things are the Sietsuki, who make their own samogon [moonshine], in the south of the country. But they are a per se case, they even have their own king and are protected as a national ethnic minority. Otherwise, we have the Hansa distillery, which has even been recognized as a UNESCO heritage. Also, after the 40s, the lesnye bratya [brothers of the wood, another name for local partisans] used to do this and are now a tourist attraction: Hutor lesnyh brat’ev.Footnote17

As in the previous Kyrgyz case, two elements are important to understand the attitude of Estonian society and how nation-building can use alternative channels. First, the inclusiveness of these possible markers. They are de-ethnicized and linked to land, national production, and consumption. From a state perspective, ‘Estonianness’ can be expressed through language, reproduction of historical memory, and the creation of the other (Smith Citation1986). This analysis, however, has highlighted how there are now aspects of performing Estonianness that pass through acceptance of a certain understanding of food, participation in country’s economic performance, contribution to its business environment, and perception of national products. These are elements with a high civic component and can be taken up by anyone, regardless of their ethnic origins or language. A second element is the unintended consequence of nation branding. Whatever the initial intentions of the campaign, it has created room for identification with a ‘national’ community that mostly passes through economic performance or reference to a hypothetical Estonian culture that has somehow been built in a lab with the creation of recipes, food narratives that, although invented (Hobsbawm and Ranger Citation1983), also offer participants an opportunity to feel Estonian by adopting and believing in these narratives, no matter how exaggerated they may be. At the end of the day, if enough people believe a certain version of things, they will bring it to the next generation, which will become how things are always perceived to have been.

Conclusion

The construction of national identity can take many forms and make use of a variety of markers. Besides more traditional approaches that examine the role of the state and its elites in defining national identity, recent literature emphasizes elements of nation-building that are not necessarily the intended consequences of political measures. This article further explores these processes through an examination of empirical case studies from Kyrgyzstan and Estonia, drawing from concepts such as banal and everyday nationalism (Billig Citation1995; Foster Citation2006; Fox and Miller-Idriss Citation2008) to show that the construction of identity markers can come in unexpected ways from nation branding efforts not initially conceived as identity creation or strengthening activities. Such spontaneous nation-building (Polese Citation2009) expands the scope of the construction of the political from officially and clearly political actors to a wider range of actors, including citizens themselves, even when they are not organized in a politicized fashion (Navaro-Yashin Citation2002).

The cases above showcased how state-led nation branding attempts in Kyrgyzstan (the homeland of nomadic games and traditions, a perfect harmony between nature and nomadism, an undiscovered nomadic tourist and investment destination) and Estonia (through Enterprise Estonia, a hub for digital business, a crossroad between European, Scandinavian, and Russian cultures) have produced local understandings of Kyrgyz and Estonian national identities. In Estonia, they contributed to patterns of special food consumption practices and cooking preferences among Estonians to shape and express Estonian identity; in Kyrgyzstan, they promoted the kok-boru horseback game among Kyrgyz. Believing in our own identity might be a matter of convincing others about what we are, and this is what, at least partly, happens in the cases illustrated above. In particular, we have sought to center our analysis on the relationship between nation branding, considered mostly an economic and marketing instrument, and nation building, which is mostly perceived as political and institutional. At the intersection of these two approaches is the idea that branding a nation can help promote identity markers that the official political discourse has not previously considered. These new interpretations can create a ‘safer space’ and uncover nuances of identity construction and relationships with their ethnic communities in ways that differ from preexisting national discourses. This type of analysis has been attempted by other authors, including Cheskin (Citation2012) for Latvia. It has led to the proposition that there is greater potential for integration into a shared national identity founded on a titular nationality within diverse political communities than is usually perceived in official accounts. Branding can ascribe to this narrative and expand the meaning of including anyone who ascribes to a certain set of values; its effects can be understood as civic in this regard, whether through contributions to the state economy (as in the Estonian case) or through participation in a sport that is perceived as a source of national pride (as in the Kyrgyz case).

These examples and this approach are important for at least two reasons. First, they highlight that national identity markers may emerge from state measures that are not political or at least were not conceived to primarily impact a target group’s identity. In both the Estonian and Kyrgyz cases, a lot of effort was put into national rebranding, from post-Soviet to ‘modern’ or ‘innovative’ in Estonia, and from ‘unstable’ or ‘unpredictable’ to genuine popular interest in nomad games in Kyrgyzstan. In both cases, however, these measures impacted well beyond the simple rebranding goals proposed to create spaces for identifying, using, and reproducing alternative markers. One consequence is that because these markers did not originate in deliberate political measures to build a national identity, they are often devoid of any state-led ideology. As a result, they are effectively de-ethnicized, allowing anyone to claim a bit more of the national character by simply aligning with the proposed markers. Such initiatives can thus contribute to a more inclusive or civic understanding of national identity.

Furthermore, these nation-building effects arise primarily from social action and non-state actors. Contrary to existing state-centric approaches in nation-building, we suggest that middling actors (independent agencies, sometimes funded by the state but not directly controlled by it) and those at the micro-level (common people, business, and cultural organizations) play a key role in negotiating, reshaping, and communicating a national identity. We highlight the importance of a long-downplayed phenomena by looking at the ‘invisible’ and ‘silent’ sides of nation formation. We expect, or at least hope, that further research can contribute to understanding the dynamics behind these phenomena.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Abel Polese

Abel Polese is a scholar and development worker dividing his time between Europe, the post-Soviet region, and Southeast Asia. He is Principal Investigator of SHADOW, a four-year project starting in 2018, which is funded through Marie Curie RISE (H2020). SHADOW is a research and training programme with the goal of producing strategic intelligence on the region and training a generation of specialists on informality in post-Soviet spaces. He is co-editor of STSS, an open access journal (Q3 in SCOPUS), focusing on governance and social issues in the non-Western world.

Arzuu Sheranova

Arzuu Sheranova is independent researcher, consultant and international development practitioner in Central Asia and Europe. She holds PhD in Political Science from Corvinus University of Budapest and MA degree in Politics and Security from the OSCE Academy in Bishkek. She is an author of publications on nationalism, identity, inter-ethnic relations, conflict prevention, power, legitimacy and informal politics.

Notes

1. A game played on horseback in Kyrgyzstan.

2. Although its name and rules are different in each country, kok-boru is an ancient game played by men on horseback in most Turkic nations. Ulak and alaman ulak is another vernacular name for kok-boru in Kyrgyzstan, which is played in a slightly different informal format. Modern-day Kyrgyz kok-boru was standardized through the setting of common rules by the famous cultural workers Bolot Shamshiev, Temir Duishekeev, and Bolot Sherniyazov in 1996. In kok-boru two teams comprised of twelve men each fight to toss a beheaded goat into the taikazan (a special plate) to score.

3. The latter is a social network popular mainly in Russia and other former Soviet countries.

4. Interview with the head of the WNG Secretariat, 17 January 2021; Interview with the specialist of the WNG Secretariat, 5 February 2021.

5. Interview with the head of the WNG Secretariat, 17 January 2021.

6. Kyrgyz were sedentarized by the Soviets between 1920 and 1930. Today, Kyrgyz still practice a seasonal nomadic lifestyle at the pastures from late spring to early autumn to feed their cattle.

7. We refer to Kyrgyzstani identity as a more inclusive and civic one, while Kyrgyz identity is rather ethnic-based. Here we use ‘Kyrgyzstanis’ because the game became widespread not only among ethnic Kyrgyz but also among other ethnicities living in Kyrgyzstan.

8. Interviews with three kok-boru players, with two representatives of the Kok-Boru Federation of Kyrgyzstan, February 2021.

9. For details on Kyrgyz feasting or toi, see Turdalieva and Provis (Citation2017).

10. Interview with a Kok-Boru player from Ozgon, 26 February 2021.

11. Interview with a Kok-Boru player from Ozgon, 26 February 2021.

12. Interview with the Minister of Culture, Information, Sport, and Youth Politics of Kyrgyzstan, 25 February 2021.

13. Interview with the general secretary of the Kok-Boru Federation of Kyrgyzstan, 26 February 2021.

14. Interviews with three kok-boru players, February 2021.

15. Interviews with three kok-boru players, February 2021.

16. Interview with the general secretary of the Kok-Boru Federation of Kyrgyzstan, 26 February 2021.

17. Personal communication with a food expert in Estonia.

References

- Adams, L. 2010. The Spectacular State: Culture and National Identity in Uzbekistan. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Anholt, S. 2007. Competitive Identity. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Antonsich, M. 2015. “Nation and Nationalism.” In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Political Geography, edited by J. A. Agnew, K. Mitchell, and G. Toal (G. Ó. Tuathail, 297–310. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Aronczyk, M. 2013. Branding the Nation: The Global Business of National Identity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Azattyk. 2018a. “Kak Kyrgyzstanskie I Mirovye SMI Osveshchali Igry Kochevnikov.” Azattyk, 4 October. https://rus.azattyk.org/a/kyrgyzstan-nomad-games/29524673.html.

- Azattyk. 2018b. “Stali li Igry kochevnikov brendom Kyrgyzstana?” Azattyk, 5 July. https://rus.azattyk.org/a/kyrgyzstan-nomad-games-brand/29339911.html.

- Bassin, M., and C. Kelly. 2012. Soviet and Post-Soviet Identities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bekus, N. 2010. “Nationalism and Socialism: “Phase D” in the Belarusian Nation-Building.” Nationalities Papers 38 (6): 829–846. https://doi.org/10.1080/00905992.2010.515973.

- Billig, M. 1995. Banal Nationalism. London: Sage.

- Browning, C., and A. Ferraz de Oliveira. 2017. “Introduction: Nation Branding and Competitive Identity in World Politics.” Geopolitics 22 (3): 481–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2017.1329725.

- Buhr, R., M. Fabrykant, and S. Hoffman. 2014. “The Measure of a Nation: Lithuanian Identity in the New Century.” Journal of Baltic Studies 45 (2): 143–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/01629778.2014.883418.

- Castelló, E., and S. Mihelj. 2018. “Selling and Consuming the Nation: Understanding Consumer Nationalism.” Journal of Consumer Culture 18 (4): 558–576. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540517690570.

- Cheskin, A. 2012. “Exploring Russian-Speaking Identity from Below: The Case of Latvia.” Journal of Baltic Studies 44 (3): 287–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/01629778.2012.712335.

- Deutsch, K., and W. Foltz. [1966] 2010. Nation Building in Comparative Contexts. New Brunswick, NJ: Aldine Transaction.

- Diener, A. C., and J. Hagen. 2013. “From Socialist to Post-Socialist Cities: Narrating the Nation Through Urban Space.” Nationalities Papers 41 (4): 487–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/00905992.2013.768217.

- Dinnie, K. 2008. Nation Branding: Concepts, Issues, Practice. London: Routledge.

- Doğan, E. 2013. “Changing Motivations of NGOs in Turkish Foreign Policy Making Processes: Economy, Identity, and Philanthropy.” International Review of Turkish Studies 3 (1): 56–81.

- Douglas, M., and B. C. Isherwood. 1996. The World of Goods: Towards an Anthropology of Consumption. London: Routledge.

- Edensor, T. 2002. National Identity, Popular Culture and Everyday Life. London: Bloomsbury.

- Eglitis, D. 2002. Imagining the Nation: History, Modernity and Revolution in Latvia. Pennsylvania, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Ehala, M. 2009. “The Bronze Soldier: Identity Threat and Maintenance in Estonia.” Journal of Baltic Studies 40 (1): 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/01629770902722294.

- Enterprise Estonia. 2012a. “Brand Estonia – Marketing Concept for Estonia: One Country, One System, Many Stories.” Issuu Website, 10 April. https://issuu.com/eas-estonia/docs/brandiraamat_eng.

- Enterprise Estonia. 2012b. “Brand Estonia – Marketing Concept for Tourism Leaflet.” Issuu Website, 30 July. https://issuu.com/eas-estonia/docs/an_old_country_in_a_shiny_package.

- Enterprise Estonia. 2018. E-Estonia Website. Accessed May 3, 2020. https://e-estonia.com/tag/statistics/.

- Enterprise Estonia. 2020a. E-Estonia Website. Accessed May 3, 2020. https://e-estonia.com/.

- Enterprise Estonia. 2020b. Enterprise Estonia Website. Accessed May 3, 2020. https://www.eas.ee/eas/?lang=en.

- Eriksen, T. H. 1993. “Formal and Informal Nationalism.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 16 (1): 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.1993.9993770.

- Fabrykant, M. 2018a. “National Identity in the Contemporary Baltics: Comparative Quantitative Analysis.” Journal of Baltic Studies 49 (3): 305–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/01629778.2018.1442360.

- Fabrykant, M. 2018b. “Why Nations Sell: Reproduction of Everyday Nationhood Through Advertising in Russia and Belarus.” In Informal Nationalism After Communism: The Everyday Construction of Post-Socialist Identities, edited by A. Polese, O. Seliverstova, E. Pawlusz, and J. Morris, 83–102. London: IB Tauris.

- Fabrykant, M., and R. Buhr. 2016. “Small State Imperialism: The Place of Empire in Contemporary Nationalist Discourse.” Nations and Nationalism 22 (1): 103–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12148.

- Fan, Y. 2006. “Branding the Nation: What is Being Branded?” Journal of Vacation Marketing 1 (1): 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766706056633.

- Fan, Y. 2010. “Branding the Nation: Towards a Better Understanding.” Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 6 (2): 97–103. https://doi.org/10.1057/pb.2010.16.

- Fauve, A. 2015. “Global Astana: Nation Branding as a Legitimization Tool for Authoritarian Regimes.” Central Asian Survey 34 (1): 110–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634937.2015.1016799.

- Foster, R. J. 2002. Materializing the Nation: Commodities, Consumption, and Media in Papua New Guinea. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Foster, R. J. 2006. “From Trobriand Cricket to Rugby Nation: The Mission of Sport in Papua New Guinea.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 23 (5): 739–758. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523360600673138.

- Fox, J. 2017. “The Edges of the Nation: A Research Agenda for Uncovering the Taken-For-Granted Foundations of Everyday Nationhood.” Nations and Nationalism 23 (1): 26–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12269.

- Fox, J. 2018. “Banal Nationalism in Everyday Life.” Nations and Nationalism 24 (4): 862–866. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12458.

- Fox, J. E., and C. Miller-Idriss. 2008. “Everyday Nationhood.” Ethnicities 8 (4): 536–563. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796808088925.

- Galbreath, D. J. 2005. Nation-Building and Minority Politics in Post-Socialist States: Interests, Influence and Identities in Estonia and Latvia. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Gavrilova, R. 2018. “Something Bulgarian for Dinner: Bulgarian Popular Cuisine as a Selling Point.” In Informal Nationalism After Communism: The Everyday Construction of Post-Socialist Identities, edited by A. Polese, O. Seliverstova, E. Pawlusz, and J. Morris, 144–163. London: IB Tauris.

- Gellner, E. 2008. Nations and Nationalism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Goode, P., and D. Stroup. 2015. “Everyday Nationalism: Constructivism for the Masses.” Social Science Quarterly 96 (3): 717–739. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12188.

- Gudjonsson, H. 2005. “Nation Branding.” Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 1 (3): 283–298. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.pb.5990029.

- Harris-Brandts, S. 2018. “The Role of Architecture in the Republic of Georgia’s European Aspirations.” Nationalities Papers 46 (6): 1118–1135. https://doi.org/10.1080/00905992.2018.1488827.

- Hart, B., and T. R. Risley. 1995. Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Young American Children. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

- Harvey, D. 1989. The Urban Experience. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Hobsbawm, E. J. 1991. Nations and Nationalism Since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hobsbawm, E. J., and T. Ranger. 1983. The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Huskey, E. 2003. “National Identity from Scratch: Defining Kyrgyzstan’s Role in World Affairs.” Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics 19 (3): 111–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523270300660020.

- Invest in Estonia. 2020. “Northern Europe’s Hub for Knowledge and Business.” Invest in Estonia Website. Accessed 3 May. https://investinestonia.com/.

- Isaacs, R. 2015. “Nomads, Warriors and Bureaucrats: Nation-Building and Film in Post-Soviet Kazakhstan.” Nationalities Papers 43 (3): 399–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/00905992.2013.870986.

- Isaacs, R. 2018. Film and Identity in Kazakhstan: Soviet and Post-Soviet Culture in Central Asia. London: IB Tauris. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350986428.

- Isaacs, R., and A. Polese. 2015. “Between “Imagined” and “Real” Nation-Building: Identities and Nationhood in Post-Soviet Central Asia.” Nationalities Papers 43 (3): 371–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/00905992.2015.1029044.

- Isaacs, R., and A. Polese. 2016. Nation-Building and Identity in the Post-Soviet Space: New Tools and Approaches. London: Routledge.

- Janmaat, J. G. 2000. Nation-Building in Post-Soviet Ukraine: Educational Policy and the Response of the Russian-Speaking Population. Utrecht: Royal Dutch Geographical Society.

- Jansen, S. C. 2008. “Designer Nations: Neo-Liberal Nation Branding–Brand Estonia.” Social Identities 14 (1): 121–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504630701848721.

- Jašina-Schäfer, A., and A. Cheskin. 2020. “Horizontal Citizenship in Estonia: Russian Speakers in the Borderland City of Narva.” Citizenship Studies 24 (1): 93–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2019.1691150.

- Jones, R. 2007. People, States, Territories. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Jones, R., and P. Merriman. 2009. “Hot, Banal and Everyday Nationalism: Bilingual Road Signs in Wales.” Political Geography 28 (3): 164–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2009.03.002.

- Jordan, P. 2014a. The Modern Fairy Tale: Nation Branding, National Identity and the Eurovision Song Contest in Estonia. Tartu: University of Tartu Press. https://doi.org/10.26530/OAPEN_474310

- Kaneva, N. 2011. “Nation Branding: Toward an Agenda for Critical Research.” International Journal of Communication 25 (5): 117–141. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1105.

- Kolstø, P. 2016. Strategies of Symbolic Nation-Building in South Eastern Europe. London: Routledge.

- Laitin, D. 1998. Identity in Formation: The Russian-Speaking Populations in the Near Abroad. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Lauristin, M. 2009. “Re-Visiting Estonia’s Transformation 20 Years on.” Paper presented at the annual CRCEES summer school, Tartu, Estonia, 3–5 July.

- Lauristin, M., and P. Vihalemm. 2009. “The Political Agenda During Different Periods of Estonian Transformation: External and Internal Factors.” Journal of Baltic Studies 40 (1): 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/01629770902722237.

- Lefebvre, H., and C. Levich. 1987. “The Everyday and Everydayness.” Yale French Studies 73 (73): 7–11. https://doi.org/10.2307/2930193.

- Lefebvre, H., and D. Nicholson-Smith. 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Lõhmus, M., M. Lauristin, and E. Siirman. 2009. “The Patterns of Cultural Attitudes and Preferences in Estonia.” Journal of Baltic Studies 40 (1): 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/01629770902722260.

- Makanbai Kyzy, G. 2021. “Shooting of a Film About National Kok-Boru Game Starts in Kyrgyzstan.” 24 KG Website, 15 July. https://24.kg/english/201301_Shooting_of_film_about_national_kok-boru_game_starts_in_Kyrgyzstan/.

- Massey, D. 1995. Spatial Divisions of Labour: Social Structures and the Geography of Production. London: Macmillan International Higher Education.

- McGlinchey, E. 2011. Chaos, Violence, Dynasty: Politics and Islam in Central Asia. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Menga, F. 2015. “Building a Nation Through a Dam: The Case of Rogun in Tajikistan.” Nationalities Papers 43 (3): 479–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/00905992.2014.924489.

- Meri, L. 2016. Sulla rotta del vento, del fuoco e dell’ultima Thule. Roma: Gangemi.

- Militz, E. 2016. “Public Events and Nation-Building in Azerbaijan.” In Nation-Building and Identity in the Post-Soviet Space: New Tools and Approaches, edited by R. Isaacs and A. Polese, 190–208. London: Routledge.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kyrgyz Republic. 2019. “Visa and Visa-Free Regimes.” Ministry of Foreign Affairs Website. https://mfa.gov.kg/ru/osnovnoe-menyu/konsulskie-uslugi/konsulskie-vizovye-voprosy/izovye-i-bezvizovye-rezhimy.

- Mole, R. 2012. The Baltic States from the Soviet Union to the European Union: Identity, Discourse and Power in the Post-Communist Transition of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. London: Routledge.

- Morris, J. 2005. “The Empire Strikes Back: Projections of National Identity in Contemporary Russian Advertising.” The Russian Review 64 (4): 642–660. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9434.2005.00379.x.

- Murzakulova, A., and J. Schoeberlein. 2009. “The Invention of Legitimacy: Struggles in Kyrgyzstan to Craft an Effective Nation-State Ideology.” Europe-Asia Studies 61 (7): 1229–1248. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668130903068756.

- Navaro-Yashin, Y. 2002. Faces of the State: Secularism and Public Life in Turkey. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Ó Beacháin, D., and R. Kevlihan. 2013. “Threading a Needle: Kazakhstan Between Civic and Ethno-Nationalist State-Building.” Nations and Nationalism 19 (2): 337–356. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12022.

- Ozolina-Fitzgerald, L. 2016. “A State of Limbo: The Politics of Waiting in Neo-Liberal Latvia.” The British Journal of Sociology 67 (3): 456–475. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12204.

- Pawlusz, E. 2017. “The Estonian Song Celebration (Laulupidu) as an Instrument of Language Policy.” Journal of Baltic Studies 48 (2): 251–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/01629778.2016.1164203.

- Pawlusz, E., and A. Polese. 2017. “‘Scandinavia’s Best-Kept Secret:’ Tourism Promotion as a Site of Nation-Building in Estonia (With a Free Guided Tour of Tallinn Airport).” Nationalities Papers 45 (5): 873–892. https://doi.org/10.1080/00905992.2017.1287167.

- Pettai, V. 2021. “National Identity and Re-Identity in Post-Soviet Estonia.” Journal of Baltic Studies 52 (3): 425–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/01629778.2021.1944236.

- Polese, A. 2009. “Dynamiques defination building et évolution d’une identité nationale en Ukraine: le cas d’Odessa.” PhD diss., Free University of Brussels.

- Polese, A. 2010. “The Formal and the Informal: Exploring ‘Ukrainian’ Education in Ukraine, Scenes from Odessa.” Comparative Education 46 (1): 47–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050060903538673.

- Polese, A. 2017. “Can Nation Building Be ‘Spontaneous’? A (Belated) Ethnography of the Orange Revolution.” In Identity and Nationalism in Everyday Post-Socialist Life, edited by A. Polese, J. Morris, E. Pawlusz, and O. Seliverstova, 161–175. London: Routledge.

- Polese, A. 2019. “Where Your Grandma’s Kitchen Belongs in a Museum.” Transitions, 27 June. Accessed May 3, 2020. https://tol.org/client/article/28463-where-your-grandmas-kitchen-belongs-in-a-museum.html.

- Polese, A., T. Ambrosio, T. Kerikmae, and O. Seliverstova. 2020. “Small Countries and New Voices: Nation Branding and Diplomatic Communication in Estonia.” Mezinarodni Vztahy/Czech Journal of International Relations 55 (2): 24–46. https://doi.org/10.32422/mv.1690.

- Polese, A., and S. Horak. 2015. “A Tale of Two Presidents: Personality Cult and Symbolic Nation-Building in Turkmenistan.” Nationalities Papers 43 (3): 457–478. https://doi.org/10.1080/00905992.2015.1028913.

- Polese, A., and O. Seliverstova. 2019. “Luxury Consumption as Identity Markers in Tallinn: A Study of Russian and Estonian Everyday Identity Construction Through Citizenship.” Journal of Consumer Culture 20 (2): 194–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540519891276.

- Polese, A., O. Seliverstova, A. Cheshkin, and P. Perchoc. 2017. “Consommation, identité et intégration en Estonie et en Lettonie.” Hermès n° 77 (1): 119–128. https://doi.org/10.3917/herm.077.0141.

- Polese, A., O. Seliverstova, E. Pawlusz, and J. Morris. 2017. Identity and Nationalism in Everyday Post-Socialist Life. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315185880.