ABSTRACT

The increase of older workers has resulted in more diversified demographics with a wide spectrum of employees’ ages. This change calls for a better understanding of intergenerational conflict, in particular ageism. This study aimed to synthesize study findings on workplace ageism by examining the relationship between ageist attitudes and chronological age. A systematic literature review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA; then, 15 studies were included. The results of an intercept-only meta-regression model, using robust variance estimation with a random-effects approach, showed that an increase in workers’ age had a significant negative association with the severity of their workplace-based ageist attitudes: b = −.159 (95% CI: −.21, −.11). Thus, the younger the workers, the more severe their ageist attitudes toward others in different age groups in the workplace. The findings offer implications for occupational social work practice in terms of priority in anti-ageism education and training among different age groups.

Introduction

Workforce demographics have changed as the proportion of older workers has increased. As a result of extended working lives, the age composition in the workplace has become diverse due to this larger proportion of older workers. In fact, according to the International Labour Organization (ILO), the proportion of labor force participation of older workers–who are aged between 55 and 64—has increased from 54.8% in 2000 to 60.6% in 2019 (International Labour Organization, Citation2020). Furthermore, because of advances in medical technologies, employees’ physical health is no longer a major obstacle to prolonging their employment, as people are able to live longer in good physical condition, which has a positive effect on the extension of their retirement age (Neumark & Song, Citation2012). This increase in the number of older workers has resulted in more diversified demographics with a wide spectrum of employees’ ages in the workplace (Crumpacker & Crumpacker, Citation2007; Schloegel et al., Citation2016).

The changes in the aforementioned workforce demographics have led to new kinds of conflicts among different generations (Rudolph & Zacher, Citation2015). Often, such intergenerational tensions are associated with age-based stereotypes, which lead to discriminatory behaviors in the workplace such as the reluctance to communicate and cooperate with individuals from different age groups (Levy & Macdonald, Citation2016; Posthuma et al., Citation2012; Powell, Citation2010; Urick, Citation2014). Previous studies have reported that ageism has a negative impact on the health of workers, causing general stress and affecting mental health such as depression or anxiety (Lyons et al., Citation2018; Marchiondo et al., Citation2019). Specifically, older workers’ experience of age-based discrimination tends to gradually increase in the workplace as they age, with negative effects on their depressive symptoms and decreases in their overall self-rated health along with declines in their job satisfaction (Marchiondo et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, Levy et al. (Citation2020) argued that negative age stereotypes and age-based discrimination, respectively, added $28.5 billion and $11.1 billion to healthcare costs per year, in relation to eight of the most expensive health conditions in the United States.

The drastic increase in older workers needs more attention in resolving workplace ageism. Note that, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the proportion of workers over 55 years has risen more than twice over 25 years, from 11.9% in 1995 to 24.5% in 2021 (Tossi & Torpey, Citation2017). Therefore, investigating ways to mitigate workplace ageism has become an important social and research agenda, particularly in light of a recent review on ageism suggesting that age-based discrimination conflicts will probably further increase in the future (Levy & Macdonald, Citation2016).

The definition of ageism

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines ageism as “stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination against people on the basis of their age” regardless of their age groups (World Health Organization, Citation2020). However, most of previous studies on ageism in the workplace have focused on negative attitudes toward older workers, such as being less productive, less motivated, less adaptable, inflexible and reluctant to change compared to their counterparts (e.g., Bal et al., Citation2011; Levy & Macdonald, Citation2016; Marchiondo et al., Citation2019). Nevertheless, as mentioned earlier, ageism is not only associated with older workers, but also with workers from all other age groups (Snape & Redman, Citation2003). For instance, younger workers can experience unfair disadvantages in promotion and deployment because they are considered too young for certain roles or regarded less loyal to their company compared to the older workers (Duncan & Loretto, Citation2004; Schloegel et al., Citation2016). Therefore, this study focuses on ageism in the workplace regardless of age groups.

Age and ageism

One of the critical questions related to ageism is whether individuals’ chronological age is associated with holding ageist attitudes. In fact, unlike gender and race, people’s chronological age is continuously changing; therefore, people naturally belong to different age groups throughout their life span. When people are young, they belong to a younger age group; on the other hand, as people age, they move into an older age group. Therefore, ageism can be relevant to everyone in many different ways as people keep moving from one age group to another. This is known as “the out-group paradox of ageism” (Jönson, Citation2013). The paradox might connect to potential availability to foster empathy toward different age groups and mitigate ageism (Solem, Citation2016). This implies that the younger age groups, who have not yet experienced being a part of other age groups, might have more ageist attitudes compared to older age groups.

Previous studies have reported contradictory findings on the relationship between chronological age and ageism in the workplace. Some of the previous studies suggested that the increase in a worker’s age was negatively correlated with his/her ageist attitude in the workplace (e.g., Bal et al., Citation2015; Iweins et al., Citation2012). For instance, the younger workers have more negative age stereotypes toward older workers based on the results of the survey conducted in the study of Bal et al. (Citation2015). On the other hand, other studies showed no significant relationship between chronological age and stereotypical attitudes toward older workers (e.g. Sammarra et al., Citation2020; Vignoli et al., Citation2021).

Study aim

Occupational social work is one of the newest fields in social service and practice with a focus on work, workers and work organizations (Kurzman, Citation2013). Understanding age effects on ageism is important in occupational social work practice, affecting the decisions and provisions of management and labor (Kurzman, Citation2013). Recent research findings on the generational gap in the workplace – with a particular focus on the millennials (Rainer & Rainer, Citation2011)—inform the practice of occupational social workers dealing with intergenerational conflicts; however, there is still a knowledge gap in understanding the relationship between workers’ chronological age and the severity of their ageist attitudes. Considering the increasing age diversity in the workplace, the present study aims to examine previous studies’ conflicting results about the relationship between chronological age and ageist attitudes in the workplace through a meta-analysis that synthesizes the results of prior studies in a statistical way. More specifically, this study aims to examine the hypothesis that there is a negative relationship between the increase of chronological age and the severity of ageist attitudes in the workplace.

Methods

A systematic literature review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Moher et al., Citation2009). Then, a meta-analysis-one of the statistical methods synthesizing the results of previous studies – was carried out on the selected studies to examine the relationship of workplace-based ageist attitudes with age.

Search strategy

We conducted a systematic literature search using two databases (i.e. the Web of Science and PubMed), looking for studies from the earliest time available till 9 September 2020. The first theme of search terms was about ageism; they included terms related to ageist attitudes such as ageism, ageist, stereotype, prejudice and discrimination, considering the definition of ageism which is “stereotyping, prejudice and discrimination against people on the basis of their age” regardless of their age group (World Health Organization, Citation2020). The second theme for search terms was about the workplace, in order to sort out workplace ageism from general ageism in non-workplace contexts; and they included workplace, work, worker and employee. In order to maximize the sensitivity of search, we used Boolean operators – connecting search words using AND, OR and NOT (MIT Libraries, Citationn.d.)—to combine the search terms.

Specifically, in the Web of Science, which provides papers published since 1970, we used the following search terms in order to find relevant studies through “advanced search” options narrowing the search areas to topic (TS), title (TI), and abstract (AB): (“ageism” OR “ageist” OR “age discrimination” OR “age stereotype” OR “age prejudice”) AND (“workplace” OR “worker” OR “work” OR “employee”). In PubMed, which provides papers published since 1969, we used the same search terms while selecting the “advanced” option to narrow the search areas to major topic (MeSH) and title and abstract (Title/Abstract).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

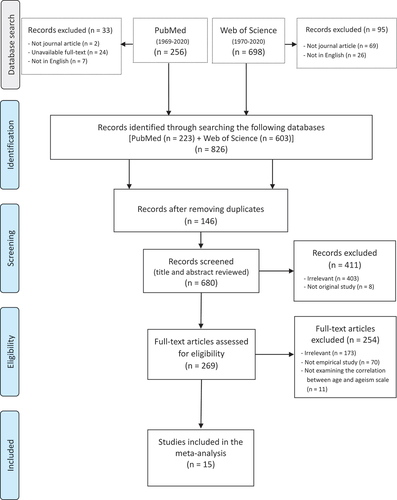

Articles meeting the following criteria were included in this study: (1) Must be an empirical study, measuring respondents’ ageist attitudes through survey questionnaires in a quantitative way; (2) Must be written in English; (3) Must include the assessment of workplace-based ageist attitudes toward workers from different age groups (i.e. older and/or younger age groups), such as a worker’s stereotypical attitudes toward older workers and his/her discriminatory behavior toward younger workers in the workplace; and (4) Must report correlation coefficients between ones’ chronological age as a continuous variable of one-year intervals (e.g., 20, 21, 22 years old) and their ageist attitudes. Accordingly, we excluded studies with a focus on ageist attitudes in non-workplace contexts in our database such as studies on college students’ discriminatory attitudes toward older adults or studies on physicians’ ageist attitudes toward older and/or younger adults. shows the details of this screening process.

Data extraction

The final database for this study consists of 15 studies meeting the inclusion criteria. Data extracted from the studies includes authors, publication year, sample composition, location and means of ageist attitudes, along with the effect sizes of correlation coefficients between age and ageist attitudes (see for the details). When the relationship between age and ageist attitudes was not statistically significant, the coefficient of correlation was recorded as zero.

Table 1. Summary of the Selected Studies.

Quality assessment

The first author initially extracted the information of each journal article into a standardized format, then the second author double-checked the data to ensure accuracy. After that, two authors assessed risk of bias in all the selected studies using the Newcastle Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for case-control studies (Wells et al., Citation2000). The authors independently assessed risk of bias of each journal article in terms of its selection, comparability and ascertainment; no study was excluded due to bias after the authors’ discussions and agreement.

Data analysis

A meta-analysis was conducted to assess the association between chronological age and ageist attitudes. In order to synthesize the outcomes of prior effect sizes, an intercept-only meta-regression model was performed using robust variance estimation (RVE) with a random-effects approach. Considering the statistical dependencies resulting from the varying number of effect sizes in each study, the RVE of a correlated effects model was employed to produce more accurate estimates of standard errors with narrower confidence intervals (Fisher & Tipton, Citation2015; Hedges et al., Citation2010; Tipton, Citation2015). We used a random-effects model because of the expectation of non-zero variation (i.e. heterogeneity) at the population level due to the heterogeneous contexts between the studies selected for the meta-analysis; also, the result was adjusted by weighting the effects of sample size (Hunter & Schmidt, Citation2004). Furthermore, we conducted small-sample adjustments as the total number of studies included in this meta-analysis was less than 40; thus, meta-analytic effect sizes (i.e. correlation coefficients) were transformed into Fisher’s z (Tipton, Citation2015).

In addition, we assessed potential publication bias by visual inspection of the estimated funnel plot as well as statistical testing of the asymmetry in Egger’s linear regression test (Egger et al., Citation1997). The trim and fill method was used to account for potential publication bias by estimating the number of missing studies in the meta-analysis (Duval & Tweedie, Citation2000). In this study, publication bias was calculated with unweighted effect sizes for each study instead of RVE due to the methodological unavailability as of this date (Zelinsky & Shadish, Citation2018). All statistical analyses were conducted using the statistical software R – in particular the package called robumeta. All subsequent analyses were computed with 95% confidence intervals (CI) (Fisher & Tipton, Citation2015).

A total of 954 records were located through the systematic search (698 from the Web of Science and 256 from PubMed). We retrieved 680 unique journal articles from these for title and abstract screening to identify and exclude studies irrelevant to the focus of this study (see ). Next, the full texts of 269 journal articles were examined; of which 254 articles were excluded because they were irrelevant or did not meet the inclusion criteria. Specifically, those dealing with ageist attitudes toward others in everyday contexts, not in the workplace toward coworkers from different age groups, were excluded (i.e. 173 articles). Also, if an article was not an empirical research study or did not include the correlation coefficient of chronological age and ageist attitudes, it was excluded. Studies which did not include chronological age as a continuous variable were excluded too. A total of 15 studies met criteria and were included in the database for qualitative and quantitative analysis.

Description of studies

The studies included in this review were published between 1995 and 2020, covering diverse samples focused on specific countries (e.g. USA, Italy, or Brazil), while 8 out of the 15 studies (53%) focused on European countries. Most of the studies had sample sizes of over 100 participants except one study with 78 participants. The age of participants in the selected studies ranged widely, from 18 to 71. In terms of measurement for assessing ageism, most of the studies included in this meta-analysis focused on measuring perceptions such as stereotypes toward older or younger workers rather than behavioral intention to act on different age groups in a discriminatory way. Specifically, 24 out of 32 measures (75%) in the 15 studies examined age-based perceptions entailing particular beliefs or thoughts. For examples, Hassell and Perrewe (Citation1995) and Liebermann et al. (Citation2013) used stereotypical beliefs toward older workers; on the other hand, the remaining measures (25%) assessed discriminatory behavioral intentions or treatment such as the avoidance of hiring older job applicants, unwillingness to work with older workers and selecting older employees for retrenchment (Chiu et al., Citation2001; Fasbender & Wang, Citation2017). In addition, the majority of scales (29 out of 32) assessed ageist attitudes toward older workers solely, without considering ageism toward younger age groups. Conspicuously, a few measures (3 out of 32) included both older and younger age groups as ageism victims by assessing implicit or explicit stereotypes toward older and younger workers (Sammarra et al., Citation2020; Zaniboni et al., Citation2019).

Results

The dataset of this study included 32 effect sizes of coefficients of correlation within the 15 identified studies, involving 5,049 cases (see ). The results of meta-analysis are presented in a forest plot using the RVE with Fisher’s z transformation of correlations (see ). The overall estimate of the coefficient correlations indicated that an increase in workers’ chronological age had a significant negative association with the severity of their workplace-based ageist attitudes: b = −.159, p < .01, (95% Confidence Interval −.21, −.11).

Heterogeneity across studies was tested using the I2 statistic. There was significant heterogeneity across the individual studies (I2 = 64%) (Higgins et al., Citation2003). To assess publication bias, the Egger’s test was conducted and showed that the observed effect size was not significantly associated with the standard errors: t(13) = −1.44, p = .17. After that, the results of the trim and fill method indicated that publication bias was not likely to be present in this meta-analysis, showing that the overall effect remained statistically significant (b = −.159, p < .001; b = −.117, p < .001, respectively) although five studies were potentially missing given the asymmetry of the funnel plot (see the Appendix) (Duval & Tweedie, Citation2000).

Discussion

The findings of this systematic literature review and meta-analysis provide insight into the relationship between age and ageist attitudes in the workplace. To our knowledge, this study is the first meta-analysis suggesting the significant negative relationship between the increase of chronological age and the severity of ageist attitudes in the workplace. That means the younger the workers, the more severe their ageist attitudes toward others in different age groups in the workplace.

The findings offer implications for occupational social work research and practice to reduce ageism in the workplace. For instance, one of the effective strategies would be for occupational social workers to implement diversity training with a focus on ageism as part of on-the-job training (OJT) programs, which teaches workers – in particular, newly hired workers who are often young workers – about a company’s overall work procedures and tasks. Also, findings demonstrate the importance for social workers to contribute to creating positive intergenerational interactions while integrating workers from diverse age groups including both younger and older workers. Occupational social workers can play an important role in including non-age discrimination statements in job advertisementsin particular, targeting younger applicants (Cebola et al., Citation2021). Creating an age-friendly work environment cannot be achieved without all the workers’ efforts regardless of age; however, the results of this study provide practice implications in terms of priority in anti-ageism education and/or training among different age groups in the workplace.

Second, more evidence is needed to better understand “ageism between coworkers.” When screening previous studies on ageism for this meta-analysis, a majority of them were excluded because they used convenience samples of college students mostly in their twenties (Rupp et al., Citation2005; Xiao et al., Citation2013). A majority of previous studies in the field tended to examine young adults’ age-based discriminatory attitudes toward older workers regardless of respondents’ employment status; and therefore, relatively little evidence has been reported with a focus on “ageism between coworkers.” To have a better understanding of workplace-based ageism, more empirical studies are needed with a focus on current workers’ ageist attitudes against their colleagues from different age groups (i.e. both older and younger) in workplace contexts.

The findings of the present study should be interpreted in light of limitations. First, this meta-analysis included only the results of cross-sectional studies; therefore, future research needs to examine the longitudinal effects of worker’s age on his/her ageist attitude while distinguishing cohort effects from age effects. We think each cohort would have varied experience in terms of work environment, which would largely affect their perceptions toward other workers. For example, due to the digital transformation accelerated by COVID-19 as well as emerging advanced digital technologies, the work environment has changed as working from home becomes common. In addition, there is the “COVID retirement boom” as older workers tend to retire early due to COVID-19 (Faria-e-Castro, Citation2021). This may affect age diversity in the workplace as well as the relationships between coworkers. Accordingly, it is important to explore how historical events and social environments influence workplace-based ageism by cohort from the life course perspective. Second, the result of this meta-analysis should be interpreted with caution due to the potential heterogeneity between studies. Countries and age ranges of the samples in the studies included for the meta-analysis differ from one another. Although we controlled the differences in the numbers of samples by weighting each effect depending on the sample size of each study, heterogeneity in terms of characteristics of samples needs to be considered when interpreting the study results.

Despite these limitations, this systematic review contributes to evidence of the significant negative relationship between the increase in workers’ age and their ageist attitudes toward workers from different generations by synthesizing the conflicting results of prior studies through a meta-analysis. This finding implies that occupational social workers need to consider age of workers in terms of developing and implementing interventions to reduce ageism in the workplace. This study also provides suggestions for future research. Future research needs to examine how ageism affects different age groups beyond solely older groups in order to have a more comprehensive understanding of age effects on ageism in the workplace. In addition, it calls for further research and development of anti-ageism interventions in the workplace, enabling evidence-based practice in the field of occupational social work.

Acknowledgments

A preliminary version of this work was presented at the 2021 Annual Summer Conference of the Korea Association for Policy Studies in June 2021.

Disclosure statement

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bal, P. M., de Lange, A. H., Van der Heijden, B. I., Zacher, H., Oderkerk, F. A., & Otten, S. (2015). Young at heart, old at work? Relations between age, (meta-) stereotypes, self-categorization, and retirement attitudes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 91, 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.09.002

- Bal, A. C., Reiss, A. E., Rudolph, C. W., & Baltes, B. B. (2011). Examining positive and negative perceptions of older workers: A meta-analysis. The Journals of Gerontology Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66(6), 687–698. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbr056

- Cebola, M., Dos Santos, N., & Dionísio, A. (2021). Worker-related ageism: A systematic review of empirical research. Ageing and Society, 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X21001380

- Chiu, W. C., Chan, A. W., Snape, E., & Redman, T. (2001). Age stereotypes and discriminatory attitudes towards older workers: An East-West comparison. Human Relations, 54(5), 629–661. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726701545004

- Crumpacker, M., & Crumpacker, J. M. (2007). Succession planning and generational stereotypes: Should HR consider age-based values and attitudes a relevant factor or a passing fad? Public personnel management, 36(4), 349–369. https://doi.org/10.1177/009102600703600405

- Duncan, C., & Loretto, W. (2004). Never the right age? Gender and age‐based discrimination in employment. Gender, Work & Organization, 11(1), 95–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2004.00222.x

- Duval, S. J., & Tweedie, R. L. (2000). A nonparametric “trim and fill” method of accounting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 95, 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.2000.10473905

- Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. British Medical Journal, 315(7109), 629–634. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

- Faria-E-Castro, M. (2021). The COVID retirement boom. Economic Synopses, 25(25), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.20955/es.2021.25

- Fasbender, U., & Wang, M. (2017). Negative attitudes toward older workers and hiring decisions: Testing the moderating role of decision makers’ core self-evaluations. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(2057). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.02057

- Fisher, Z., & Tipton, E. (2015, March 7). Robumeta: An R-package for robust variance estimation in meta-analysis. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1503.02220

- Hassell, B. L., & Perrewe, P. L. (1995). An examination of beliefs about older workers: Do stereotypes still exist? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 16(5), 457–468. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030160506

- Hedges, L. V., Tipton, E., & Johnson, M. C. (2010). Robust variance estimation in meta-regression with dependent effect size estimates. Research Synthesis Methods, 1(1), 39–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.5

- Higgins, J., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J., & Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. British Medical Journal, 327, 557–560. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

- Hunter, J. E., & Schmidt, F. L. (2004). Methods of meta-analysis: Correcting error and bias in research findings (2nd ed.). Sage.

- International Labour Organization. (2020, October 18). ILOSTAT database [ILO modelled estimates and projections]. Retrieved from https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/.

- Iweins, C., Desmette, D., & Yzerbyt, V. (2012). Ageism at work: What happens to older workers who benefit from preferential treatment? Psychologica Belgica, 52(4), 327–349. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb-52-4-327

- Jönson, H. (2013). We will be different! Ageism and the temporal construction of old age. The Gerontologist, 53(2), 198–204. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gns066

- Kurzman, P. (2013). Occupational social work. Encyclopedia of Social Work. Retrieved 19 Jun. 2022, from https://oxfordre.com/socialwork/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.001.0001/acrefore-9780199975839-e-268.

- Levy, S. R., & Macdonald, J. L. (2016). Progress on understanding ageism. The Journal of Social Issues, 72(1), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12153

- Levy, B. R., Slade, M. D., Chang, E. S., Kannoth, S., & Wang, S. Y. (2020). Ageism amplifies cost and prevalence of health conditions. The Gerontologist, 60(1), 174–181. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny131

- Liebermann, S. C., Wegge, J., Jungmann, F., & Schmidt, K. H. (2013). Age diversity and individual team member health: The moderating role of age and age stereotypes. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 86(2), 184–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12016

- Lu, L. (2010). Attitudes toward older people and coworkers’ intention to work with older employees: A Taiwanese study. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 71(4), 305–322. https://doi.org/10.2190/AG.71.4.c

- Lyons, A., Alba, B., Heywood, W., Fileborn, B., Minichiello, V., Barrett, C., Hinchliff, S., Malta, S., & Dow, B. (2018). Experiences of ageism and the mental health of older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 22(11), 1456–1464. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1364347

- Marchiondo, L. A., Gonzales, E., & Williams, L. J. (2019). Trajectories of perceived workplace age discrimination and long-term associations with mental, self-rated and occupational health. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 74(4), 655–663. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbx095

- Marcus, J., Fritzsche, B. A., Le, H., & Reeves, M. D. (2016). Validation of the work-related age-based stereotypes (WAS) scale. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 31(5), 989–1004. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-11-2014-0320

- MIT Libraries. (n.d.). Database search tips: Boolean operators. Retrieved from https://libguides.mit.edu/c.php?g=175963&p=1158594

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(10), 1006–1012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005

- Neumark, D., & Song, J. (2012). Barriers to later retirement: Increases in the full retirement age, age discrimination, and the physical challenges of work (Report No. 2012-265). Michigan Retirement Research Center.

- Ospina, J. H., Cleveland, J. N., & Gibbons, A. M. (2019). The relationship of employment scarcity and perceived threat with ageist and sexist attitudes. Work, Aging and Retirement, 5(3), 215–235. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waz003

- Posthuma, R. A., Wagstaff, M. F., & Campion, M. A. (2012). Age stereotypes and workplace age discrimination. In J. W. Hedge & W. C. Borman (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Work and Aging (pp. 298–312). Oxford University Press.

- Powell, M. (2010). Ageism and abuse in the workplace: A new frontier. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 53(7), 654–658. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2010.508510

- Rainer, T., & Rainer, J. (2011). The millennials connecting to America´s largest generation. B&H Publishing Group.

- Redman, T., & Snape, E. (2002). Ageism in teaching: Stereotypical beliefs and discriminatory attitudes towards the over-50s. Work, Employment and Society, 16(2), 355–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/095001702400426884

- Rego, A., Vitória, A., Cunha, M. P. E., Tupinambá, A., & Leal, S. (2017). Developing and validating an instrument for measuring managers’ attitudes toward older workers. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(13), 1866–1899.

- Rego, A., Vitória, A., Tupinambá, A., Júnior, D. R., Reis, D., Cunha, M. P. E., & Lourenço-Gil, R. (2018). Brazilian managers’ ageism: A multiplex perspective. International Journal of Manpower, 39(3), 414–433.

- Rudolph, C. W., & Zacher, H. (2015). Intergenerational Perceptions and Conflicts in Multi-Age and Multigenerational Work Environments. In L. M. Finkelstein, D. M. Truxillo, F. Fraccaroli, & R. Kanfer (Eds.), Facing the Challenges of a Multi-Age Workforce: A Use-Inspired Approach (pp. 253–282). Routledge.

- Rupp, D. E., Vodanovich, S. J., & Credé, M. (2005). The multidimensional nature of ageism: Construct validity and group differences. The Journal of Social Psychology, 145(3), 335–362. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.145.3.335-362

- Sammarra, A., Profili, S., Peccei, R., & Innocenti, L. (2020). When is age dissimilarity harmful for organisational identification? The moderating role of age stereotypes and perceived age-related treatment. Human Relations, 74(6), 869–891. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726719900009

- Schloegel, U., Stegmann, S., Maedche, A., & Van Dick, R. (2016). Reducing age stereotypes in software development: The effects of awareness-and cooperation-based diversity interventions. The Journal of Systems and Software, 121, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2016.07.041

- Snape, E., & Redman, T. (2003). Too old or too young? The impact of perceived age discrimination. Human Resource Management Journal, 13(1), 78–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2003.tb00085.x

- Solem, P. E. (2016). Ageism and age discrimination in working life. Nordic Psychology, 68(3), 160–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/19012276.2015.1095650

- Tipton, E. (2015). Small-sample adjustments for robust variance estimation with meta-regression. Psychological methods, 20(3), 375–393. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000011

- Tossi, M., & Torpey, E. (2017, May). Older workers: Labor force trends and career options. Retrieved from June 10, 2020, https://www.bls.gov/careeroutlook/2017/article/older-workers.htm

- Urick, M. J. (2014). The presentation of self: Dramaturgical theory and generations in organizations. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 12(4), 398–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2014.961829

- Vignoli, M., Zaniboni, S., Chiesa, R., Alcover, C. M., Guglielmi, D., & Topa, G. (2021). Maintaining and engaging older workers at work: The trigger role of personal and psychosocial resources. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(8), 1731–1753. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1579252

- Wells, G. A., Shea, B., O’Connell, D., Peterson, J., Welch, V., & Losos, M. (2000) The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Retrieved from May 1, 2022, http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- World Health Organization. (2020). Ageing and life-course. Retrieved from May 25, 2020, https://www.who.int/ageing/ageism/en/

- Xiao, L. D., Shen, J., & Paterson, J. (2013). Cross-cultural comparison of attitudes and preferences for care of the elderly among Australian and Chinese nursing students. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 24(4), 408–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659613493329

- Zaniboni, S., Kmicinska, M., Truxillo, D. M., Kahn, K., Paladino, M. P., & Fraccaroli, F. (2019). Will you still hire me when I am over 50? The effects of implicit and explicit age stereotyping on resume evaluations. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(4), 453–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2019.1600506

- Zelinsky, N. A., & Shadish, W. (2018). A demonstration of how to do a meta-analysis that combines single-case designs with between-groups experiments: The effects of choice making on challenging behaviors performed by people with disabilities. Developmental Neurorehabilitationn, 21(4), 266–278. https://doi.org/10.3109/17518423.2015.1100690