ABSTRACT

A sense of control is important for supporting older people living with frailty to develop adaptive functioning to optimize wellbeing. This scoping review examined the literature on the sense of control and wellbeing in older people living with frailty within their everyday life and care service use. Nine databases were searched using the timeframe 2000 to 2021 to identify key ideas regarding control and wellbeing in older people with frailty. The review highlighted three major themes: a) Control as conveyed in bodily expressions and daily activities, b) Sense of control and influence of place of residence, and c) Control within health and social care relationships. Maintaining a sense of control is not only an internal feeling but is impacted by physical and social environments. Greater focus is needed on the nature of relationships between older people living with frailty and those who work alongside them, which support control and wellbeing.

Introduction

As people age, they are gradually more likely to develop and live with complex co-morbidities linked to chronic diseases, illnesses, and injuries, resulting in a condition known as frailty (Buckinx et al., Citation2015; De Donder et al., Citation2019; Oliver et al., Citation2014). The British Geriatrics Society (BGS) defines frailty as; “a distinctive health state related to the aging process in which multiple body systems gradually lose their in-built reserves” (BGS, Citation2014, p. 6). Frailty is associated with cumulative deficits in multiple organ systems contributing to decreased bodily reserve and functional capacity in old age (Kojima, Citation2015; Nicholson et al., Citation2013; Turner & Clegg, Citation2014).

The impact of frailty in older people mainly manifests as physical decline experienced on two levels: a) the individual body and b) the contextual body. The individual body refers to the person’s body and its problems, such as ailments and injuries. The contextual body refers to the body and its limitations concerning the physical and social surroundings, such as being unable to independently perform daily living activities (Ekwall et al., Citation2012). Such deficits and limitations place a person at increased risk of adverse health outcomes, including admission to higher care levels, emergency hospitalization, prolonged hospital stay, and increased mortality (Andrew et al., Citation2012; Dent & Hoogendijk, Citation2014; González-Bautista et al., Citation2020; King et al., Citation2017). Consequently, older people living with frailty often report poor self-rated health and low levels of life satisfaction (Abu-Bader et al., Citation2003; Johannesen et al., Citation2004; King et al., Citation2017).

Perceived health in older people living with frailty is often linked to psychosocial factors, especially a sense of control (Dent & Hoogendijk, Citation2014; Elliot et al., Citation2018; Gale et al., Citation2014). Although there is no conclusive or all-inclusive definition of the concept of control, the literature highlights that the construct has been studied using different dimensions. The dimensions include perceived control, self-efficacy, personal mastery, locus of control, control beliefs, learned helplessness, and primary and secondary control (Skinner, Citation1996). In essence, these dimensions interrelate in creating an overall impact on individuals’ ability to produce desired outcomes or a feeling that life changes are under one’s mastery rather than life being directed by fate or uncontrolled external factors (Kempen et al., Citation2005; Lachman et al., Citation2011; Robinson & Lachman, Citation2017). Thus, a perceived sense of control is often translated into personal and sometimes social resources that individuals use to successfully manage their everyday life and environment and adapt to life changes such as old age and its associated challenges (Kempen et al., Citation2003).

A sense of control is important for individuals living with frailty because of the need to manage bodily changes and activity and social limitations to prevent deterioration as well as to maintain a sense of wellbeing (Kempen et al., Citation2003; Underwood et al., Citation2020; van Oppen et al., Citation2022). Frailty is associated with a loss of control in older people. Archibald et al. (Citation2020) argue that frailty in older people is associated with diminished mobility and independence, which contributes to a loss of control over one’s body and environment and affects their sense of identity and self-worth. In addition, a perceived lack of control negatively influences the risk and incidence of frailty in older people. The literature highlights that declining levels of control are associated with a greater likelihood of frailty (Dent & Hoogendijk, Citation2014; Elliot et al., Citation2018; Gale et al., Citation2014 Frank J. Infurna & Gerstorf, Citation2014).

In contrast, perceived control plays a buffering role against challenges contributing to old age frailty. For example, studies identified that perceived control has a moderating effect on the impact of low social-economic status and greater exposure to chronic stress on the development and progression of frailty in older people (Barbareschi et al., Citation2008; Dent & Hoogendijk, Citation2014; Mooney et al., Citation2018; Pudrovska et al., Citation2005).

Despite the bi-directional relationship between perceived control and frailty, the evidence is unclear as to whether the adverse health outcomes in the form of frailty precede the loss of control or the limited sense of control contributes to frailty. Regardless of the trajectory, however, the above findings make it clear that a loss of control is one of the primary losses experienced by older people living with frailty (Dent & Hoogendijk, Citation2014; King et al., Citation2017).

Evidence suggests that feelings of control progressively decrease as people grow older, irrespective of frailty status (Barbareschi et al., Citation2008; Krause, Citation2007; Ross & Mirowsky, Citation2002; Wolinsky et al., Citation2003). As a result, there is an increased emphasis on promoting a sense of control in old age to minimize the risk and impact on health outcomes (Hong et al., Citation2021; Kim, Citation2020; Skaff, Citation2007). This is because perceived control is considered a fundamental psychological aspect that improves coping and adaptive behaviors enabling older people to exploit available resources to cope with life stressors to maintain psychological wellbeing (Caplan & Schooler, Citation2007; Chou & Chi, Citation2001; Firth et al., Citation2008; Robinson & Lachman, Citation2017). Additionally, perceived cognitive control is associated with greater control of emotions, which is vital in improving the emotional wellbeing and cognitive performance in older people (Charles & Carstensen, Citation2010; Lachman, Citation2006; Stephanie A. Robinson & Lachman, Citation2018; Zahodne et al., Citation2015). Moreover, a sense of control is associated with adopting positive health behaviors such as adherence to treatment, good diet, and exercises which are vital in enhancing better health outcomes in old age (Barbareschi et al., Citation2008).

Evidence supports the linkage of perceived control with better mental and physical health outcomes, including lower disability levels, faster recovery of bodily functions, and lower mortality risks, particularly among older people experiencing a gradual decline in functioning (Assari, Citation2017; Bailis et al., Citation2001; Kempen et al., Citation2003, Citation2005; Popova, Citation2012; Turiano et al., Citation2014; Ward, Citation2013). Consequently, promoting a sense of control is considered an essential component of successful aging and research on older person care has emphasized a need to support and empower older people to take more control of their health and wellbeing (Infurna et al., Citation2013; Kunzmann et al., Citation2002; Lachman et al., Citation2009; Oliver et al., Citation2014; Turiano et al., Citation2014).

Despite this well-documented importance of a sense of control for older individuals, limited reviews focus on control in different categories of older people. Most reviews on the sense of control in old age have generally focused on older people. No scoping review explicitly targets the sense of control in older people with frailty. More importantly, such a lack of studies limits the development and maintenance of psychosocial resources and the potential to identify those factors that restrict control and increase frailty in older people, undermining their resilience and making them more vulnerable to infirmity and elevated risk of mortality (Claassens et al., Citation2014; Dent & Hoogendijk, Citation2014; Milte et al., Citation2015; Nicholson et al., Citation2012).

This review, therefore, aims: 1) to examine the extent, range, and nature of research activity into a sense of control and wellbeing in older people living with frailty within their everyday life and health and social care services use and 2) to identify research gaps in the existing literature to inform primary research on the topic area (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). With these aims, the review set out the following question “What is known about control and its relation to wellbeing in older people living with frailty within their everyday life and health and social care service use?”. A scoping review was chosen for two reasons. Firstly, because of time constraints and the fact that the review aimed at identifying the available literature and the research gaps on the topic area rather than formulating practice recommendations (Munn et al., Citation2018). Secondly, scoping reviews are flexible yet rigorous and transparent processes. Rather than being guided by a highly focused research question that aims at searching for specific study designs, as is the case in systematic reviews, the scoping review method is guided by a requirement to identify all relevant literature regardless of the study design (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005).

Materials and methods

A scoping review was carried out following the five key stages of the Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) framework: identifying the review question, identifying relevant studies, study selection, charting the data, and collating, summarizing, and reporting the results (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). Furthermore, we incorporated Levac et al. (Citation2010) recommendations to make the review robust and enhance its clarity and methodological rigor. Firstly, we used the components of the topic area, such as the Population, Concept and Context (PCC), to define the review question, search strategy and, subsequently, the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Secondly, we clarified the decision-making process regarding the study selection process to ensure transparency. Thirdly, the chosen charting approach was consistently applied across all the included papers. Finally, we applied qualitative thematic analysis to link the meaning of the results to the review purpose and the implication for future research. These recommendations enabled us to provide a sufficient methodological description of the review and analysis of the data to make it easy for the readers to understand how we arrived at the results (Levac et al., Citation2010).

The review included relevant original research articles published between 2000 and 2021. This timeline was chosen because we were interested in understanding how the notion of control has evolved over the years. Nine databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, Medline Complete, Web of Science, Social Care Online, Science Direct, Scopus, CINAHL Complete, and SocINDEX) were chosen to provide a comprehensive overview of the health, psychological and social literature. The search strategy included keywords, synonyms, and truncations, as summarized in . The search process was conducted iteratively from 15/10/2020 to 20/11/2021. The search strategy was continually refined after several iterations of the search, and the first author made decisions on refinement with guidance from the second and third authors (Levac et al., Citation2010). Finally, the key search terms were determined using the PCC considerations to guide the search for papers (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005; Levac et al., Citation2010).

The review included papers a) focusing on empirical research with older people aged 60 years and over and living with frailty and stakeholders involved in their care, b) focusing on control and/or its related concepts, and c) conducted in different care settings. The review also considered quantitative and qualitative empirical studies conducted in English in all parts of the world.

To ensure that the inclusion and exclusion criteria fit the scope of the review, we linked the review question to the review purpose by envisioning the intended outcomes of the review before it was undertaken. We debated the inclusion and exclusion criteria and agreed on the best and most feasible criteria to answer the review aims and objectives. Defining the scope involved balancing the need for breadth with feasibility, particularly time constraints and acknowledging the limitations linked to the limited scope and other methodological decisions (Levac et al., Citation2010).

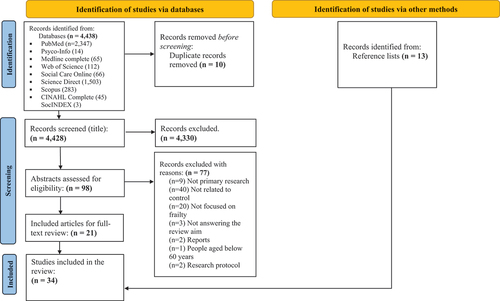

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to select the studies that “represent the best fit with the research question” (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005, p. 15). After the title search, the abstracts were examined, and this process concluded with a full-text examination of the eligible papers to inform the charting process. The reference lists of the eligible papers were also reviewed, and some more papers that met the inclusion criteria were included. Endnote (Citation2013) was used to organize and manage search records and for reference in the final scoping review report (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). In addition, the study used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram () to make the literature search visually accessible and easily read (Page et al., Citation2021).

The charted papers were manually analyzed using a qualitative thematic analysis framework by Braun and Clarke (Citation2012). This framework has six key steps: Step 1: Becoming familiar with the data, Step 2: Generating initial codes, Step 3: Searching for themes, Step 4: Reviewing potential themes, Step 5: Defining and naming themes, and Step 6: Producing the report. The first author read and re-read the charted data in Microsoft Excel (Citation2018) to identify recurring points, similarities, and differences (codes) in line with the review question (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). These codes were organized according to key issues by prioritizing certain aspects of the literature according to the review question and what was most noticeable during the review process (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). This resulted in the identification of three overarching themes. The themes generated were decided through discussions between the authors. The first author analyzed and synthesized results and developed the first round of themes. The second and third authors provided feedback and a second perspective on the first author’s definition and interpretation of the themes.

Since a scoping review aims to map out the existing evidence to identify gaps and inform primary research and not to make clinical or policy recommendations, we did not undertake any methodological appraisal of the quality of the included studies (Grant & Booth, Citation2009).

Finally, the review was part of a doctoral project, and the first author worked with the second and third authors, who provided supervisory input on all stages of the review. The first author did the initial review. Consequently, the second and third authors provided feedback and modifications made by the first author based on the feedback. The review process was complete when we were all satisfied with the final results.

Results

The database search retrieved a total of 4,438 records, and a total of 34 papers were included in the review.

The majority of the papers were published in the Scandinavian countries (n = 12), the Netherlands (n = 7) and the USA (n = 5) and a small number in Australia (n = 2), Belgium (n = 1), Canada (n = 1), England (n = 1), Germany (n = 1), Hongkong (n = 1), Italy (n = 1), Mexico (n = 1), and Siri Lanka (n = 1). 77% of the papers were published between 2010 and 2020 (n = 26), and 24% were published between 2000 and 2008 (n = 8). In terms of the methodology, 56% of the papers were quantitative (questionnaires, n = 14, other methods, n = 5). In addition, 97% focused on capturing the views of older people living with frailty (n = 33), while 9% focused on carers’ views (n = 3). The major outcome measures for the quantitative papers included different dimensions of control (locus of control, expected and desired control, multidimensional health locus of control, perceived autonomy, independence, self-efficacy, and mastery), domains of social, physical, and psychological wellbeing (autonomy, personal growth, mastery, positive relations, purpose in life, emotional balance, self-acceptance, chronic stress, depression and cognitive functioning), Quality of life (QoL) dimensions (life overall, health, social relationships and participation, freedom, home and neighborhood, financial circumstance, leisure, activities and religion), perceived health (physical health, functional disability, morbidity, long length of hospital stay, emergency rehospitalization, higher level of care needed on discharge, and mortality), Self- Management Abilities (SMA) (Cognitive abilities, active motivational abilities, and resource-combining abilities) and life satisfaction. There were only 13 qualitative papers with limited in-depth approaches. Six papers used content analysis, two followed the grounded theory and just one used phenomenology.

The results highlighted three themes: a) Control as conveyed in bodily expressions and daily activities, b) Sense of control and influence of place of residence, and c) Control within health and social care relationships. provides an overview of all the included papers and their contributions to the themes.

Overview of the included paper

Theme 1: Control as conveyed in bodily expressions and daily activities

Control in older people living with frailty is mainly expressed within the increasing limitations in their bodies and activities of daily living.

Control over the body

Bodily changes and pain limited control over the body and independence in older people living with frailty, as highlighted by Siriwardhana et al. (Citation2019), who looked at the association between frailty and QoL domains, including independence and control over life. As a result, many older people living with frailty rely on the assistance of others to achieve even simple daily activities, for example, getting out of bed, which meant that they sometimes stayed in their beds or chairs for extended periods as they waited for assistance (Kwong et al., Citation2014). Such incidents are linked to physical and psychological stress and a lower sense of control, further exposing older people to greater severity of physical frailty (Mooney et al., Citation2018). Therefore, a sense of control was linked to individuals’ perceived potential to manage their bodies and maintain self-care capacity.

When older people living with frailty engage in different self-care activities, such as exercises, managing their medication, and maintaining a good diet, they are more able to manage the limitations brought about by their bodies and the associated symptoms (Claassens et al., Citation2014; Niesten et al., Citation2012). Even in cases where their engagement with self-care activities was unrelated to the caring needs emerging from their frail condition, self-care activities provided and reinforced a perception of control and better QoL (Kwong et al., Citation2014; Milte et al., Citation2015). For example, by adopting a good oral hygiene schedule, older people living with frailty felt that they retained some control over their physical body and maintained a better sense of wellbeing (Niesten et al., Citation2012).

Consequently, the review has led us to understand that the levels of control of older individuals living with frailty have external manifestations and bodily expressions. If older individuals perceive they have or retain control of certain aspects of their body, this can compensate for parts of their body they do not have control over due to frailty. This perceived sense of control of parts of their body can consequently create feelings of wellbeing despite their frailty.

Control over activities of daily life

The review found that a sense of control in older people living with frailty impacted activities of daily living (Abu-Bader et al., Citation2003; Ekdahl et al., Citation2010; Hedman et al., Citation2019; Janlöv et al., Citation2006; Lambotte et al., Citation2019; Strohbuecker et al., Citation2011). Johannesen et al. (Citation2004) examined the association between measures such as continuity and self-determination with everyday life satisfaction among older people living with frailty. Results indicated that continuing daily activities is positively associated with life satisfaction. These individuals feel in control whenever they have choices over everyday life aspects, such as whether to do certain things on their own and maintaining regular routines in everyday life such as gardening, cleaning, preparing meals and engaging in community activities (Andersson et al., Citation2008; Claassens et al., Citation2014; Ebrahimi et al., Citation2013; Ekwall et al., Citation2012; Falk et al., Citation2011; Janlöv et al., Citation2006; Kristensson et al., Citation2010; Portegijs et al., Citation2016; Thorson & Davis, Citation2000). Engaging in meaningful activities of daily living enhances several control and wellbeing outcomes in older people living with frailty, such as a sense of identity, independence, environmental mastery, and reduced risk of adverse health outcomes, including hospitalization (Andrew et al., Citation2012; Dent & Hoogendijk, Citation2014; Ebrahimi et al., Citation2013; Ekwall et al., Citation2012; Gale et al., Citation2014; González-Bautista et al., Citation2020; Hedman et al., Citation2019; Siriwardhana et al., Citation2019). The literature identifies at least three preconditions for older individuals living with frailty to maintain greater control over their daily activities. Firstly, by remaining at home or in a familiar environment where they feel not only safe and supported by familiar care providers but also stay connected with family, friends, and other members of society that they value to avoid social isolation and loneliness (Andersson et al., Citation2008; Broese van Groenou et al., Citation2016; Ebrahimi et al., Citation2013). Secondly, a range of self-management techniques can strengthen older people’s cognitive and behavioral capabilities to manage their lives, improve their wellbeing and prepare for future age and health-related challenges. Several quantitative studies analyzed the relationship between Self-Management Abilities (SMA) and subjective wellbeing, QoL and self-rated health. They found that SMA is vital in supporting older people living with frailty to take the initiative in managing aspects of daily lives and maintaining various multi-functional resources significant in dealing with different age-related declines (Cramm et al., Citation2014; Frieswijk et al., Citation2006; Schuurmans et al., Citation2005; Vestjens et al., Citation2020). Thirdly, having easy access to practical aids such as vision and mobility aids coupled with supportive architecture such as furniture raisers to get out of bed or reach kitchen cabinets easily made a significant difference to the sense of control among older people living with frailty (Claassens et al., Citation2014).

In summary, the literature highlights that older people living with frailty maintain greater levels of control when they maintain normal routines and retain choices in simple daily activities.

Theme 2: Sense of control and influence of place of residence

This theme highlights the differences in the levels and experiences of control and wellbeing among older people living with frailty in the community and during their transition to nursing homes.

Living at home

As highlighted above, living at home was associated with independence and a higher sense of control. Grain (Citation2001) compared the sense of control and life satisfaction between homebound older people and nursing home residents and found that they expressed higher perceived control than their nursing home counterparts. This is because of their engagement in everyday activities where they felt that they were not a burden to other people, thus enhancing their sense of continuity, self-determination and good health (Ebrahimi et al., Citation2013; Grain, Citation2001; Johannesen et al., Citation2004). Moreover, living at home allowed for seamless integration of their new caring needs, the caregiving process, and the familiarity with the environment, ergo creating a sense of “homeness” and a notion of continuity which are crucial in enhancing older people’s sense of wellbeing (Andersson et al., Citation2008). Consequently, older people living with frailty at home feel safer, more engaged, and have a greater sense of continuity, increasing their sense of control and wellbeing.

Despite the preference to stay at home, some older people living with frailty reported that trying too hard to remain independent sometimes created a heavy burden for themselves, thereby perceiving excessive control as harmful to their health and overall wellbeing (Claassens et al., Citation2014). In addition, the physical and cognitive limitations arising from illness or frailty impacted individuals’ capacity to participate in decision-making processes. In such situations, retaining a sense of control became a burden rather than a contributor to wellbeing, compelling older people to surrender some or all of their decision-making power and control to significant others, such as professional caregivers and/or family members (Andersson et al., Citation2008; Bilotta et al., Citation2010; Claassens et al., Citation2014; Ekdahl et al., Citation2010; Lambotte et al., Citation2019).

However, in those cases where older individuals preferred to have their care decisions made by others, they wished to be informed and listened to by their care providers. This open communication minimized the possibility of the older person interpreting that care providers were taking the care responsibility away from them and anticipated as they were handing it over willingly (Ekwall et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, willful handing over of control to family members required that the older individual living with frailty did not anticipate this to be a burden for the family member; otherwise, this negatively impacted their wellbeing (Janlöv et al., Citation2006).

In summary, living at home enhanced a sense of safety, independence, and continuity among older people living with frailty. Although age and disease-related decline sometimes compelled them to surrender their control, willfully relinquishing control was paradoxically considered one way of exercising control as long as the person was informed and listened to by their care providers.

Control and relocation away from own home

In those cases where older people living with frailty had no option but to relocate from their home to a nursing home or even from one nursing home to another, this was often a stressful event as relocation aspects altered their normal routines (Falk et al., Citation2011). Hence, these routine alterations in the new living environments created outcomes including uncertainty, confusion, and abandonment, thereby imposing further limitations on older people’s sense of control and creating adverse health effects, including mortality (Thorson & Davis, Citation2000). In nursing homes, giving up usual activities and routines and depending on others for participation in everyday habits and community life created a sense of passivity that was anticipated as a loss of control among older people living with frailty (Grain, Citation2001; Johannesen et al., Citation2004; Kwong et al., Citation2014; Sandgren et al., Citation2020; Strohbuecker et al., Citation2011). Older individuals living with frailty were able to ameliorate this sense of loss of control by having a say in their relocation, undergoing a pre-relocation preparation, and maintaining some of their habits, e.g., moving to the same side of the new buildings as the previous building (Falk et al., Citation2011; Thorson & Davis, Citation2000).

Both formal and informal care providers were crucial in developing or retaining degrees of control of older people living with frailty during and after their relocation. For example, formal caring staff, such as nurses, can promote the participation of older people in their clinical assessment and care planning, acknowledging older people’s choices and respecting their privacy and dignity, which enhanced their sense of control (Hedman et al., Citation2019). Similarly, informal carers supported older people in nursing homes to attend social gatherings, engage in exercises and supervised their formal care, thereby empowering them to maintain control (Kwong et al., Citation2014; Wallerstedt et al., Citation2018). However, nursing home staff shortages and a lack of expertise in dealing with older people living with frailty may affect the approaches above (Kwong et al., Citation2014). This is particularly the case when nurses make decisions for older people without consulting them about their wishes or complaints, intensifying their loss of control (Strohbuecker et al., Citation2011).

In summary, the relocation of older people living with frailty to institutionalized care can limit their sense of control, particularly when this transition is accompanied by sudden changes in older people’s routines. Furthermore, staff shortages or lack of expertise in supporting older people living with frailty may lead to formal carers making and imposing decisions, intensifying their loss of control in nursing homes. In contrast, the involvement of older people living with frailty in decisions regarding their relocation and care planning, as well as the perceived support from their loved ones, can empower them to maintain degrees of control in institutional care.

Theme 3: Control within health and social care relationships

A sense of control in older people living with frailty is linked to the nature of the care relationships and the power dynamics within the health and social care systems.

Role of trusting relationships

The reviewed literature identified that developing a trusting relationship between older people living with frailty and formal/informal carers is pivotal in enhancing older people’s sense of control. The starting point for creating such a relationship can be the display of humor and empathy in caring interactions using simple gestures such as chatting, hugging and holding hands (Claassens et al., Citation2014; Hedman et al., Citation2019). This can create a sense of support and joy for older people living with frailty and further develop their communication, cooperation and a natural togetherness with their carers, leading to more caring and individualistic relationships and the perception of being a member of the caring team (Claassens et al., Citation2014; Hedman et al., Citation2019; Wallerstedt et al., Citation2018).

Consequently, a trusting, caring relationship enables an environment where care aspects such as information sharing and joint decision-making thrive, facilitating key control dimensions such as choice, autonomy and participation (Ekdahl et al., Citation2010; Hedman et al., Citation2019). In addition, this type of relationship further develops mutual respect and recognition of individuality. This is important in recognizing the individual’s unique experiences and care needs and/or wishes, which is vital in facilitating a sense of balance and normality and creating a greater sense of control for older individuals living with frailty (Claassens et al., Citation2014; Lambotte et al., Citation2019; Strohbuecker et al., Citation2011; Vestjens et al., Citation2020). Moreover, a thriving interprofessional working relationship between care providers ensures that care needs are sufficiently met and creates a feeling of security for older individuals (Claassens et al., Citation2014; Hedman et al., Citation2019). Finally, within the context of informal care, a trustful relationship enhances the notion of care reciprocity between older individuals and their informal carers. This creates the perception that older people living with frailty are not only resource takers, further intensifying their sense of control and usefulness (Ebrahimi et al., Citation2013; Janlöv et al., Citation2006; Lambotte et al., Citation2019).

In summary, empathetic, cooperative and reciprocal relationships between older people living with frailty and care providers, and good interprofessional relationships among care providers can enhance older people’s independence in care, a sense of togetherness, and perceived control.

Sense of control and power relationships

The reviewed literature shows that the depersonalization of the care process can create a perceived power imbalance between older individuals living with frailty and professional care staff. As a result, some care staff may not discuss the care options or plans with older individuals living with frailty, mainly disregarding the need for information sharing or overruling older people’s views if expressed (Ekdahl et al., Citation2010; Ekwall et al., Citation2012; Falk et al., Citation2011; Kristensson et al., Citation2010). For example, some older people living with frailty felt they lacked information on different care aspects, such as the type of help they could claim, due to the reluctance of home help officers to share such details willingly (Janlöv et al., Citation2006). Such power imbalances can intensify older individuals’ feelings of powerlessness, making them unable to ask questions or query decisions and compelling them to do as they are told (Andersson et al., Citation2008; Ekwall et al., Citation2012).

The bureaucratic tendencies and the pre-determined, rigid, and unresponsive functioning of hospitals and other care organizations can make older individuals living with frailty feel powerless (Ekdahl et al., Citation2010; Janlöv et al., Citation2006; Kristensson et al., Citation2010). In addition, they often struggle with gatekeepers of such care organizations, especially when waiting for key decisions such as relocation or discharge, creating feelings of uncertainty (Kristensson et al., Citation2010). Moreover, some care organizations pay more attention to specific tasks and less to a comprehensive understanding of the person, which is often disempowering to older people living with frailty (Hedman et al., Citation2019; Kristensson et al., Citation2010). This limits older peoples’ sense of control and potential to adjust to their care environment and situation.

In summary, the organizational structures of care organizations and the existing power imbalances between care professionals and older people living with frailty contribute to feelings of uncertainty, powerlessness and a limited sense of control in older people living with frailty.

Discussion

This scoping review examines and summarizes the literature on a sense of control and wellbeing in older people living with frailty within their everyday life and health and social care services. There is a small but growing literature in this area, with most work being carried out in Scandinavian countries. Drawing on perspectives of older people living with frailty and their caregivers in different care settings, the review generated three themes a) Control as conveyed in bodily expressions and daily activities; b) Sense of control and influence of place of residence; and c) Control within health and social care relationships.

There is clear quantitative and qualitative evidence demonstrating the relationship between the body, sense of control and sense of wellbeing for people living with frailty. The greater the limitation in bodily ability, the greater the challenge to a sense of control and wellbeing. These findings align with other studies that have shown that poor health creates biological disruptions in the body that exacerbate physical declines and contribute to the loss of functional abilities and ill-being in older people (Bhullar et al., Citation2010; Clarke & Korotchenko, Citation2011; Clarke et al., Citation2008; Satariano et al., Citation2010). Also, the findings align with a broader change in the sense of identity noted previously in older people. Older people experience body changes, including unintentional weight loss and slowing down, which affect their sense of identity (Alibhai et al., Citation2005; Chapman, Citation2011; Martin & Twigg, Citation2018; Thomas, Citation2005). Among others, the first theme highlights a disproportionate emphasis on biomedical aspects of the body, even though internal feelings of control can significantly compensate for the physical decline. Martin and Twigg (Citation2018) argue that focusing on the biomedical aspects of the body alone is ‘reductionist and “objectifying,” and more attention should be placed on the ‘embodied experiences of everyday life of older people (p. 3). This perspective is often linked to the concept of subjective aging, where some older people feel younger than their biological age and physical appearance, which is associated with resilience and better health outcomes in old age (Cleaver & Muller, Citation2002; Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn et al., Citation2008; Kornadt et al., Citation2018).

Another key aspect of the review is the importance of self-management and a sense of control. This is particularly important for people living with frailty, as deterioration can be slowed by engaging in activities and exercise (Angulo et al., Citation2020; Silva et al., Citation2017; Theou et al., Citation2011). This finding concurs with other studies exploring SMA’s benefits to older people’s wellbeing (Clarke et al., Citation2020; Cramm & Nieboer, Citation2015; Cramm et al., Citation2012; Steverink et al., Citation2005). The overriding message from these studies is that older people with health challenges that impede their participation in everyday activities can benefit from taking initiatives such as engaging in physical exercises. Clarke et al. (Citation2020) accentuate that exercises are vital to older people because they enable them to maintain health and physical functionality to continue participating in everyday activities. Another study indicates that SMA among older people can play a preventative role, especially when dealing with long-term cognitive decline (Cramm & Nieboer, Citation2022). However, some research has extended the discussion on the benefits of SMA beyond physiological aspects and highlighted the social benefits of SMA to older people, particularly in reducing loneliness (Nieboer et al., Citation2020). One way to enhance SMA is through promoting health literacy and ensuring high-quality patient-professional relationships (Cramm & Nieboer, Citation2015; Geboers et al., Citation2016). Generally, most of the available work on SMA in older people is mainly quantitative, focusing much on measurable outcomes. It would be interesting to find out what older people feel about SMA in their everyday life.

An important finding from the review is that the physical and social environment mediates a sense of control. Theme two suggests that older people living with frailty prefer to stay in their homes for as long as possible. This is supported by the wider literature on older people in general (Bárrios et al., Citation2020; Stones & Gullifer, Citation2016). This highlights how the sense of control and wellbeing is not only based within the individual but are relational. Theme two highlights the detrimental impact of environmental change and the potential lack of control over this change. These findings align with other studies that report diminished autonomy over everyday decisions when older people transition to nursing homes (Reimer & Keller, Citation2009; Wikström & Emilsson, Citation2014). However, some studies have reported that in some cases, older people in nursing homes can exercise free will on different aspects, such as bedtime and privacy, depending on the nurses’ flexibility, positive attitude, and respect for older people’s needs (Tuominen et al., Citation2016). In both cases, feeling in control over the environment seems to have more to do with how the environment makes people feel than the environment itself. Todres et al. (Citation2009) concur that feeling human is closely associated not only with the familiarity of the physical environment but primarily with the sense of comfort, security, and unreflective ease it exudes, and the lack of such attributes can lead an individual to feel like a stranger and the environment unhomely. The reviewed literature has revealed the challenges that older people living with frailty encounter during their relocation to nursing homes and from one nursing home to another and the ideals of good relocation care practices. However, these aspects have been explored mainly using quantitative approaches, and gerontological research and practice would benefit from understanding the lived experiences of relocations among older people.

Theme three suggests that a sense of control in older people living with frailty is supported through trusted relationships at different care levels. This implies that people are not just individuals, as seen in the medical model, but they live within networked relationships of meaning throughout their lives, and it is this meaning that should be the currency of care (Todres et al., Citation2007). Trusting relationships based on respect, empathy, and compassion can create a sense of security and togetherness in care processes, increasing care satisfaction (Heggestad et al., Citation2015; Sung & Dunkle, Citation2009). These findings are consistent with Dinç and Gastmans (Citation2013), who argue that trust is vital in building relationships between nurses and patients and that trusting relationships form the cornerstone of caring practices. However, this relationship is sometimes missing in care processes (Johnsson et al., Citation2019). The review has highlighted the role of formal and informal care providers in facilitating or obstructing a sense of control in older people living with frailty. However, few studies focus on care providers’ perspectives on control and wellbeing in older people with frailty. The review was only able to locate three studies by Hedman et al. (Citation2019), Wallerstedt et al. (Citation2018), and Broese van Groenou et al. (Citation2016), which focused on the perspectives of formal and informal care providers. Considering caregivers’ critical role in facilitating a sense of control and wellbeing in older people, conducting more studies that capture their perspectives is essential.

Furthermore, this review highlights that trusting caring relationships are sometimes challenged by organizational systems and service user vulnerability. This often manifests in power imbalances at the care provider and organizational levels. For example, care providers are perceived as experts who use their professional knowledge and competence to make care decisions, sometimes without the involvement of the older person, which culminates in a diminished sense of control for the older individual (D’Avanzo et al., Citation2017). Similarly, care organizational structures can support existing power imbalances between care professionals and older people living with frailty, creating conditions for delimiting the sense of control. This occurs where care interactions are dominated by a “system” discourse into which the person either fits or does not, with no room for other interpretations or discourses other than that of the professionals (Galvin & Todres, Citation2013).

Limitations of the review

This review was carried out as part of a PhD study which meant that the main author carried out most of the work rather than two or more researchers conducting and cross-checking all decisions in detail. However, all decisions were discussed and checked with the supervisory team in regular supervisory sessions, and any issues were resolved by consulting the second and third authors. In addition, in the search process, we only used key terms and other search components, such as subject headings, were not considered. Similarly, the first level of screening considered titles and not titles and abstracts. Therefore, relevant articles may have been missed. Furthermore, to strike a balance between feasibility in terms of time and the ability to answer the review question or achieve the review purpose, we decided to limit the search to only peer-reviewed primary research. Thus, some potentially relevant literature may have been left out from other sources, such as review articles, websites, blogs, research protocols, reports, conference proceedings, dissertations/theses, editorials, and commentaries which formed part of the exclusions. Finally, as this was a scoping review, there was no assessment of the methodological quality of the included papers. Therefore, it is possible that some of the included papers may not be of the highest quality or methodological rigor.

Conclusion

A sense of control in older people living with frailty is increasingly acknowledged as an important care and policy issue. This review shows that there is clear quantitative and qualitative evidence to demonstrate the importance of the sense of control in managing the development of frailty and the active maintenance of ability leading to a sense of wellbeing. Furthermore, this scoping review highlights that the sense of control is not solely an internally regulated feeling but is highly dependent and inextricably linked to the physical and social environments and the meanings held within these environments. However, most studies have been quantitative. This review highlights the need for more qualitative studies to explore and gain understanding from older people living with frailty and those working alongside them to understand these relationships and their meanings.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No 813928.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abu-Bader, S. H., Rogers, A., & Barusch, A. S. (2003). Predictors of life satisfaction in frail elderly. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 38(3), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1300/J083v38n03_02

- Alibhai, S. M. H., Greenwood, C., & Payette, H. (2005). An approach to the management of unintentional weight loss in elderly people. Cmaj, 172(6), 773–780. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.1031527

- Andersson, M., Hallberg, I. R., & Edberg, A. -K. (2008). Old people receiving municipal care, their experiences of what constitutes a good life in the last phase of life: A qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 45(6), 818–828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.04.003

- Andrew, M. K., Fisk, J. D., & Rockwood, K. (2012). Psychological wellbeing in relation to frailty: A frailty identity crisis? International Psychogeriatrics, 24(8), 1347. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610212000269

- Angulo, J., El Assar, M., Álvarez-Bustos, A., & Rodríguez-Mañas, L. (2020). Physical activity and exercise: Strategies to manage frailty. Redox Biology, 35, 101513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2020.101513

- Archibald, M., Lawless, M., Ambagtsheer, R. C., & Kitson, A. (2020). Older adults’ understandings and perspectives on frailty in community and residential aged care: An interpretive description. BMJ Open, 10(3), e035339. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035339

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Assari, S. (2017). Race, sense of control over life, and short-term risk of mortality among older adults in the United States. Archives of Medical Science: AMS, 13(5), 1233–1240. https://doi.org/10.5114/aoms.2016.59740

- Bailis, D. S., Segall, A., Mahon, M. J., Chipperfield, J. G., & Dunn, E. M. (2001). Perceived control in relation to socioeconomic and behavioral resources for health. Social Science & Medicine, 52(11), 1661–1676. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00280-X

- Barbareschi, G., Sanderman, R., Kempen, G. I. J. M., & Ranchor, A. V. (2008). The mediating role of perceived control on the relationship between socioeconomic status and functional changes in older patients with coronary heart disease. The Journals of Gerontology Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63(6), 353–P361. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/63.6.P353

- Bárrios, M. J., Marques, R., & Fernandes, A. A. (2020). Envelhecer com saúde: estratégias de ageing in place de uma população portuguesa com 65 anos ou mais. Revista de Saúde Pública, 54, 129. https://doi.org/10.11606/s1518-8787.2020054001942

- BGS. (2014). Introduction to Frailty, Fit for Frailty Part 1. Retrieved from London: https://www.bgs.org.uk/sites/default/files/content/resources/files/2018-05-23/fff_full.pdf.

- Bhullar, N., Hine, D. W., & Myall, B. R. (2010). Physical decline and psychological wellbeing in older adults: A longitudinal investigation of several potential buffering factors. In R. E. Hicks (Ed.), Personality and individual differences: current directions (pp. 237–247). Australian Academic Press.

- Bilotta, C., Bowling, A., Casè, A., Nicolini, P., Mauri, S., Castelli, M., & Vergani, C. (2010). Dimensions and correlates of quality of life according to frailty status: A cross-sectional study on community-dwelling older adults referred to an outpatient geriatric service in Italy. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 8(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-8-56

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. American Psychological Association.

- Broese van Groenou, M., Jacobs, M., Zwart‐olde, I., & Deeg, D. J. H. (2016). Mixed care networks of community‐dwelling older adults with physical health impairments in the Netherlands. Health & Social Care in the Community, 24(1), 95–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12199

- Buckinx, F., Rolland, Y., Reginster, J. -Y., Ricour, C., Petermans, J., & Bruyère, O. (2015). Burden of frailty in the elderly population: Perspectives for a public health challenge. Archives of Public Health, 73(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-015-0068-x

- Caplan, L. J., & Schooler, C. (2007). Socioeconomic status and financial coping strategies: The mediating role of perceived control. Social Psychology Quarterly, 70(1), 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250707000106

- Chapman, I. M. (2011). Weight loss in older persons. Medical Clinics, 95(3), 579–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2011.02.004

- Charles, S. T., & Carstensen, L. L. (2010). Social and emotional aging. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 383–409. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100448

- Chou, K. -L., & Chi, I. (2001). Stressful life events and depressive symptoms: Social support and sense of control as mediators or moderators? International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 52(2), 155–171. https://doi.org/10.2190/9C97-LCA5-EWB7-XK2W

- Claassens, L., Widdershoven, G. A., Van Rhijn, S. C., Van Nes, F., Van Groenou, M. I. B., Deeg, D. J. H., & Huisman, M. (2014). Perceived control in health care: A conceptual model based on experiences of frail older adults. Journal of Aging Studies, 31, 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2014.09.008

- Clarke, L. H., Currie, L., & Bennett, E. V. (2020). ‘I don’t want to be, feel old’: Older Canadian men’s perceptions and experiences of physical activity. Aging & Society, 40(1), 126–143. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X18000788

- Clarke, L. H., Griffin, M., & Team, P. R. (2008). Failing bodies: Body image and multiple chronic conditions in later life. Qualitative Health Research, 18(8), 1084–1095. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732308320113

- Clarke, L. H., & Korotchenko, A. (2011). Aging and the body: A review. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue canadienne du vieillissement, 30(3), 495–510. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980811000274

- Cleaver, M., & Muller, T. E. (2002). I want to pretend i’m eleven years younger: Subjective age and seniors’ motives for vacation travel. In B. D. Zumbo (Ed.), Advances in Quality of Life Research 2001 (pp. 227–241). Springer.

- Cramm, J. M., Hartgerink, J. M., De Vreede, P. L., Bakker, T. J., Steyerberg, E. W., Mackenbach, J. P., & Nieboer, A. P. (2012). The relationship between older adults’ self-management abilities, wellbeing and depression. European Journal of Aging, 9(4), 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-012-0237-5

- Cramm, J. M., & Nieboer, A. P. (2015). Chronically ill patients’ self-management abilities to maintain overall wellbeing: What is needed to take the next step in the primary care setting? BMC Family Practice, 16(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-015-0340-8

- Cramm, J. M., & Nieboer, A. P. (2022). Are self-management abilities beneficial for frail older people’s cognitive functioning? BMC Geriatrics, 22(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03353-4

- Cramm, J. M., Twisk, J., & Nieboer, A. P. (2014). Self-management abilities and frailty are important for healthy aging among community-dwelling older people; a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatrics, 14(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-14-28

- D’Avanzo, B., Shaw, R., Riva, S., Apostolo, J., Bobrowicz-Campos, E., Kurpas, D., Bujnowska, M., & Holland, C. (2017). Stakeholders’ views and experiences of care and interventions for addressing frailty and pre-frailty: A meta-synthesis of qualitative evidence. PloS One, 12(7), e0180127. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180127

- De Donder, L., Smetcoren, A. -S., Schols, J. M. G. A., van der Vorst, A., Dierckx, E., & Consortium, D. S. (2019). Critical reflections on the blind sides of frailty in later life. Journal of Aging Studies, 49, 66–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2019.100787

- Dent, E., & Hoogendijk, E. O. (2014). Psychosocial factors modify the association of frailty with adverse outcomes: A prospective study of hospitalized older people. BMC Geriatrics, 14(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-14-108

- Dinç, L., & Gastmans, C. (2013). Trust in nurse–patient relationships: A literature review. Nursing Ethics, 20(5), 501–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733012468463

- Ebrahimi, Z., Wilhelmson, K., Eklund, K., Moore, C. D., & Jakobsson, A. (2013). Health despite frailty: Exploring influences on frail older adults’ experiences of health. Geriatric Nursing, 34(4), 289–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2013.04.008

- Ekdahl, A. W., Andersson, L., & Friedrichsen, M. (2010). “They do what they think is the best for me.” Frail elderly patients’ preferences for participation in their care during hospitalization. Patient Education and Counseling, 80(2), 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.026

- Ekwall, A., Rahm Hallberg, I., & Kristensson, J. (2012). Compensating, controlling, resigning and accepting-older person’s perception of physical decline. Current Aging Science, 5(1), 13–18. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874609811205010013

- Elliot, A. J., Mooney, C. J., Infurna, F. J., & Chapman, B. P. (2018). Perceived control and frailty: The role of affect and perceived health. Psychology and Aging, 33(3), 473. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000218

- EndNote. (2013). The EndNote team (version EndNote X9) [Mobile application software].

- Falk, H., Wijk, H., & Persson, L. -O. (2011). Frail older persons’ experiences of interinstitutional relocation. Geriatric Nursing, 32(4), 245–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2011.03.002

- Firth, N., Frydenberg, E., & Greaves, D. (2008). Perceived control and adaptive coping: Programs for adolescent students who have learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 31(3), 151–165. https://doi.org/10.2307/25474645

- Frieswijk, N., Steverink, N., Buunk, B. P., & Slaets, J. P. J. (2006). The effectiveness of a bibliotherapy in increasing the self-management ability of slightly to moderately frail older people. Patient Education and Counseling, 61(2), 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2005.03.011

- Gale, C. R., Cooper, C., Deary, I. J., & Sayer, A. A. (2014). Psychological wellbeing and incident frailty in men and women: The English longitudinal study of aging. Psychological Medicine, 44(4), 697. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291713001384

- Galvin, K., & Todres, L. (2013). Caring and well-being: A lifeworld approach. Routledge.

- Geboers, B., de Winter, A. F., Spoorenberg, S. L. W., Wynia, K., & Reijneveld, S. A. (2016). The association between health literacy and self-management abilities in adults aged 75 and older, and its moderators. Quality of Life Research, 25(11), 2869–2877. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1298-2

- González-Bautista, E., Manrique-Espinoza, B., Ávila-Funes, J. A., Naidoo, N., Kowal, P., Chatterji, S., & Salinas-Rodríguez, A. (2020). Social determinants of health and frailty are associated with all-cause mortality in older adults. Salud Pública de México, 61(5, sep–oct), 582–590. https://doi.org/10.21149/10062

- Grain, M. (2001). Control beliefs of the frail elderly: Assessing differences between homebound and nursing home residents. Care Management Journals, 3(1), 42–46. https://doi.org/10.1891/1521-0987.3.1.42

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Hedman, M., Häggström, E., Mamhidir, A. -G., & Pöder, U. (2019). Caring in nursing homes to promote autonomy and participation. Nursing Ethics, 26(1), 280–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733017703698

- Heggestad, A. K. T., Høy, B., Sæteren, B., Slettebø, Å., Lillestø, B., Rehnsfeldt, A., Aas, T., Lohne, V., Råholm, M. -B., Aasgaard, T., Caspari, S., & Nåden, D. (2015). Dignity, dependence, and relational autonomy for older people living in nursing homes. International Journal of Human Caring, 19(3), 42–46. https://doi.org/10.20467/1091-5710-19.3.42

- Hong, J. H., Lachman, M. E., Charles, S. T., Chen, Y., Wilson, C. L., Nakamura, J. S., Kim, E. S., & Kim, E. S. (2021). The positive influence of sense of control on physical, behavioral, and psychosocial health in older adults: An outcome-wide approach. Preventive Medicine, 149, 106612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106612

- Infurna, F. J., & Gerstorf, D. (2014). Perceived control relates to better functional health and lower cardio-metabolic risk: The mediating role of physical activity. Health Psychology, 33(1), 85. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030208

- Infurna, F. J., Ram, N., & Gerstorf, D. (2013). Level and change in perceived control predict 19-year mortality: Findings from the Americans’ changing lives study. Developmental Psychology, 49(10), 1833–1847. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031041

- Janlöv, A. C., Hallberg, I. R., & Petersson, K. (2006). Older persons’ experience of being assessed for and receiving public home help: Do they have any influence over it? Health & Social Care in the Community, 14(1), 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2005.00594.x

- Johannesen, A., Petersen, J., & Avlund, K. (2004). Satisfaction in everyday life for frail 85-year-old adults: A Danish population study. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 11(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038120410019045

- Johnsson, A., Wagman, P., Boman, Å., & Pennbrant, S. (2019). Striving to establish a care relationship—Mission possible or impossible?—Triad encounters between patients, relatives and nurses. Health Expectations, 22(6), 1304–1313. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12971

- Kempen, G. I. J. M., Ormel, J., Scaf-Klomp, W., Van Sonderen, E., Ranchor, A. V., & Sanderman, R. (2003). The role of perceived control in the process of older peoples’ recovery of physical functions after fall-related injuries: A prospective study. The Journals of Gerontology Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 58(1), 35–P41. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/58.1.P35

- Kempen, G. I. J. M., Ranchor, A. V., Ormel, J., Sonderen, E. V., Jaarsveld, C. H. M. V., & Sanderman, R. (2005). Perceived control and long-term changes in disability in late middle-aged and older persons: An eight-year follow-up study. Psychology & Health, 20(2), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440512331317652

- Kim, B. (2020). Sense of Control and Frailty among Older Adults. (Doctoral dissertation, University of Massachusetts Boston).

- King, K. E., Fillenbaum, G. G., & Cohen, H. J. (2017). A cumulative deficit laboratory test–based frailty index: Personal and neighborhood associations. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(9), 1981–1987. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14983

- Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn, A., Kotter-Grühn, D., & Smith, J. (2008). Self-perceptions of aging: Do subjective age and satisfaction with aging change during old age? The Journals of Gerontology Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63(6), 377–P385. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/63.6.P377

- Kojima, G. (2015). Prevalence of frailty in nursing homes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 16(11), 940–945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2015.06.025

- Kornadt, A. E., Hess, T. M., Voss, P., & Rothermund, K. (2018). Subjective age across the life span: A differentiated, longitudinal approach. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 73(5), 767–777.

- Krause, N. (2007). Age and decline in role-specific feelings of control. The Journals of Gerontology Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62(1), S28–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/62.1.S28

- Kristensson, J., Hallberg, I. R., & Ekwall, A. K. (2010). Frail older adult’s experiences of receiving health care and social services. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 36(10), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.3928/00989134-20100330-08

- Kunzmann, U., Little, T., & Smith, J. (2002). Perceiving control: A double-edged sword in old age. The Journals of Gerontology Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 57(6), 484–P491. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/57.6.P484

- Kwong, E.W. -Y., Lai, C.K. -Y., & Liu, F. (2014). Quality of life in nursing home settings: Perspectives from elderly residents with frailty. Clinical Nursing Studies, 2(1), 100–110. https://doi.org/10.5430/cns.v2n1p100

- Lachman, M. E. (2006). Perceived control over aging-related declines: Adaptive beliefs and behaviors. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(6), 282–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00453.x

- Lachman, M. E., Neupert, S. D., & Agrigoroaei, S. (2011). The Relevance of Control Beliefs for Health and Aging. In K. Schaie, S. Willis (Eds.), Handbook of the Psychology of Aging (7th ed., pp. 175–190). Elsevier.

- Lachman, M. E., Rosnick, C. B., & Röcke, C. (2009). The rise and fall of control beliefs and life satisfaction in adulthood: Trajectories of stability and change over ten years. In H. B. Bosworth, C. Hertzog (Eds.), Aging and Cognition: Research Methodologies and Empirical Advances (pp. 143–160). American Psychological Association.

- Lambotte, D., Kardol, M. J. M., Schoenmakers, B., Fret, B., Smetcoren, A. S., De Roeck, E. E., Dury, S., De Donder, L., Dury, S., Dierckx, E., Duppen, D., Verté, D., Hoeyberghs, L. J., De Witte, N., Engelborghs, S., De Deyn, P. P., De Lepeleire, J., Vorst, A., Zijlstra, G. A. R. … Schols, J. M. G. A. (2019). Relational aspects of mastery for frail, older adults: The role of informal caregivers in the care process. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(3), 632–641. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12676

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Martin, W., & Twigg, J. (2018). Aging, body and society: Key themes, critical perspectives. Journal of Aging Studies, 45, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2018.01.011

- Microsoft Excel. (2018). Microsoft corporation. [Mobile application software]. Retrieved from https://office.microsoft.com/excel.

- Milte, C. M., Luszcz, M. A., Ratcliffe, J., Masters, S., & Crotty, M. (2015). Influence of health locus of control on recovery of function in recently hospitalized frail older adults. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 15(3), 341–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12281

- Mooney, C. J., Elliot, A. J., Douthit, K. Z., Marquis, A., & Seplaki, C. L. (2018). Perceived control mediates effects of socioeconomic status and chronic stress on physical frailty: Findings from the health and retirement study. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 73(7), 1175–1184.

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- Nicholson, C., Meyer, J., Flatley, M., & Holman, C. (2013). The experience of living at home with frailty in old age: A psychosocial qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50(9), 1172–1179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.01.006

- Nicholson, C., Meyer, J., Flatley, M., Holman, C., & Lowton, K. (2012). Living on the margin: Understanding the experience of living and dying with frailty in old age. Social Science & Medicine, 75(8), 1426–1432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.06.011

- Nieboer, A. P., Hajema, K., & Cramm, J. M. (2020). Relationships of self-management abilities to loneliness among older people: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01584-x

- Niesten, D., van Mourik, K., & van der Sanden, W. (2012). The impact of having natural teeth on the QoL of frail dentulous older people. A qualitative study. BioMed Central Public Health, 12(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-839

- Oliver, D., Foot, C., & Humphries, R. (2014). Making our health and care systems fit for an aging population [pdf]. In K. O’Neill (Ed.), (pp. 82). Retrieved from https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/making-health-care-systems-fit-aging-population-oliver-foot-humphries-mar14.pdf.

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D. Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J.M., Akl, E.A., Brennan, S.E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J.M., Hrobjartsson, A., Lalu, M.M, Li, T., Loder, E.W., Mayo-Wilson, E., & McDonald, S. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. The BMJ, 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Popova, S. (2012). Locus of control-predictor of health and subjective well–being. European Medical, Health and Pharmaceutical Journal, 4. https://doi.org/10.12955/emhpj.v4i0.367

- Portegijs, E., Rantakokko, M., Viljanen, A., Sipilä, S., & Rantanen, T. (2016). Is frailty associated with life-space mobility and perceived autonomy in participation outdoors? A longitudinal study. Age and Aging, 45(4), 550–553. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afw072

- Pudrovska, T., Schieman, S., Pearlin, L. I., & Nguyen, K. (2005). The sense of mastery as a mediator and moderator in the association between economic hardship and health in late life. Journal of Aging and Health, 17(5), 634–660. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264305279874

- Reimer, H. D., & Keller, H. H. (2009). Mealtimes in nursing homes: Striving for person-centered care. Journal of Nutrition for the Elderly, 28(4), 327–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639360903417066

- Robinson, S. A., & Lachman, M. E. (2017). Perceived control and aging: A mini-review and directions for future research. Gerontology, 63(5), 435–442. https://doi.org/10.1159/000468540

- Robinson, S. A., & Lachman, M. E. (2018). Perceived control and cognition in adulthood: The mediating role of physical activity. Psychology and Aging, 33(5), 769. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000273

- Ross, C. E., & Mirowsky, J. (2002). Age and the gender gap in the sense of personal control. Social Psychology Quarterly, 65(2), 125–145. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090097

- Sandgren, A., Arnoldsson, L., Lagerholm, A., & Bökberg, C. (2020). Quality of life among frail older persons (65+ years) in nursing homes: A cross‐sectional study. Nursing Open, 8(3), 1232–1242. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.739

- Satariano, W. A., Ivey, S. L., Kurtovich, E., Kealey, M., Hubbard, A. E., Bayles, C. M., Prohaska, T. R., Hunter, R. H., & Prohaska, T. R. (2010). Lower-body function, neighborhoods, and walking in an older population. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 38(4), 419–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.031

- Schuurmans, H., Steverink, N., Frieswijk, N., Buunk, B. P., Slaets, J. P. J., & Lindenberg, S. (2005). How to measure self-management abilities in older people by self-report. The development of the SMAS-30. Quality of Life Research, 14(10), 2215–2228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-005-8166-9

- Silva, R. B., Aldoradin-Cabeza, H., Eslick, G. D., Phu, S., & Duque, G. (2017). The effect of physical exercise on frail older persons: a systematic review. The Journal of Frailty & Aging, 6(2), 91–96.

- Siriwardhana, D. D., Weerasinghe, M. C., Rait, G., Scholes, S., & Walters, K. R. (2019). The association between frailty and quality of life among rural community-dwelling older adults in Kegalle district of Sri Lanka: A cross-sectional study. Quality of Life Research, 28(8), 2057–2068. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02137-5

- Skaff, M. M. (2007). Sense of control and health: A dynamic due in the aging process. In C. Aldwin, C. Park, & A. Spiro (Eds.), Handbook of health psychology and aging (pp. 186–209). Guilford Press.[Google Scholar].

- Skinner, E. A. (1996). A guide to constructs of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(3), 549–570. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.3.549

- Steverink, N., Lindenberg, S., & Slaets, J. P. J. (2005). How to understand and improve older people’s self-management of wellbeing. European Journal of Aging, 2(4), 235–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-005-0012-y

- Stones, D., & Gullifer, J. (2016). ‘At home it’s just so much easier to be yourself’: Older adults’ perceptions of aging in place. Aging & Society, 36(3), 449–481. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X14001214

- Strohbuecker, B., Eisenmann, Y., Galushko, M., Montag, T., & Voltz, R. (2011). Palliative care needs of chronically ill nursing home residents in Germany: Focusing on living, not dying. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 17(1), 27–34. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2011.17.1.27

- Sung, K. -T., & Dunkle, R. E. (2009). How social workers demonstrate respect for elderly clients. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 52(3), 250–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634370802609247

- Theou, O., Stathokostas, L., Roland, K. P., Jakobi, J. M., Patterson, C., Vandervoort, A. A., & Jones, G. R. (2011). The effectiveness of exercise interventions for the management of frailty: A systematic review. Journal of Aging Research, 2011, 1–19. 2011. https://doi.org/10.4061/2011/569194

- Thomas, D. R. (2005). Weight loss in older adults. Reviews in Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders, 6(2), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-005-6725-6

- Thorson, J. A., & Davis, R. E. (2000). Relocation of the institutionalized aged. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56(1), 131–138. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(200001)56:1<131:AID-JCLP12>3.0.CO;2-S

- Todres, L., Galvin, K., & Dahlberg, K. (2007). Lifeworld-led healthcare: Revisiting a humanizing philosophy that integrates emerging trends. Medicine, Health Care, and Philosophy, 10(1), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-006-9012-8

- Todres, L., Galvin, K. T., & Holloway, I. (2009). The humanization of healthcare: A value framework for qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Wellbeing, 4(2), 68–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482620802646204

- Tuominen, L., Leino-Kilpi, H., & Suhonen, R. (2016). Older people’s experiences of their free will in nursing homes. Nursing Ethics, 23(1), 22–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733014557119

- Turiano, N. A., Chapman, B. P., Agrigoroaei, S., Infurna, F. J., & Lachman, M. (2014). Perceived control reduces mortality risk at low, not high, education levels. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 33(8), 883–890. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000022

- Turner, G., & Clegg, A. (2014). Best practice guidelines for the management of frailty: A British geriatrics society, age UK and Royal College of general practitioners report. Age and Aging, 43(6), 744–747. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afu138

- Underwood, F., Latour, J. M., & Kent, B. (2020). A concept analysis of confidence related to older people living with frailty. Nursing Open, 7(3), 742–750. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.446

- van Oppen, J. D., Coats, T. J., Conroy, S. P., Lalseta, J., Phelps, K., Regen, E., Mackintosh, N., Valderas, J. M., & Mackintosh, N. (2022). What matters most in acute care: An interview study with older people living with frailty. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02798-x

- Vestjens, L., Cramm, J. M., & Nieboer, A. P. (2020). A cross-sectional study investigating the relationships between self-management abilities, productive patient-professional interactions, and wellbeing of community-dwelling frail older people. European Journal of Aging, 18(3), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-020-00586-3

- Wallerstedt, B., Behm, L., Alftberg, Å., Sandgren, A., Benzein, E., Nilsen, P., & Ahlström, G. (2018). Striking a balance: A qualitative study of next of kin participation in the care of older persons in nursing homes in Sweden. Healthcare, 6(2), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare6020046

- Ward, M. M. (2013). Sense of control and self-reported health in a population-based sample of older Americans: Assessment of potential confounding by affect, personality, and social support. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 20(1), 140–147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-011-9218-x

- Wikström, E., & Emilsson, U. M. (2014). Autonomy and control in everyday life in care of older people in nursing homes. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 28(1), 41–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763893.2013.858092

- Wolinsky, F. D., Wyrwich, K. W., Babu, A. N., Kroenke, K., & Tierney, W. M. (2003). Age, aging, and the sense of control among older adults: A longitudinal reconsideration. The Journals of Gerontology Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 58(4), S212–220. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/58.4.S212

- Zahodne, L. B., Meyer, O. L., Choi, E., Thomas, M. L., Willis, S. L., Marsiske, M., Parisi, J. M., Rebok, G. W., & Parisi, J. M. (2015). External locus of control contributes to racial disparities in memory and reasoning training gains in ACTIVE. Psychology and Aging, 30(3), 561. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000042

Appendix 1:

Table A1. Final search terms, synonyms, and truncations.

Table A2. The table below provides an overview of the included papers.