ABSTRACT

Home and community-based services (HCBS) for older adults have been promoted worldwide to address the growing problems of aging. This systematic review included 59 studies published from 2013 to 2023 to explore factors influencing the utilization of HCBS among older adults. The review identified 15 common factors grouped into four levels of influence: individual, inter-relationship, community, and social contextual levels. The findings suggest that HCBS utilization is a dynamic process influenced by multiple factors at different levels. Gerontological social work should incorporate ecological thinking to improve practice and strengthen caregiver-recipient relationships.

Introduction

With an increasingly aging population, there is a significant rise in the demand for long-term care (LTC). According to World Population Prospects 2022, it is anticipated that the percentage of individuals aged 65 years or older in the worldwide population will witness a noticeable surge from 10% in the year 2022 to approximately 16% by the year 2050 (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Citation2022). In association with population aging, spending on LTC continues to increase. In 2010, LTC spending accounted for 1.3% of the GDP of the United States, and this figure is anticipated to rise to 3.0% by 2050 (Congressional Budget Office, Citation2013). A similar trend exists in the United Kingdom, where LTC spending represented 1.2% of GDP in 2017 and is forecast to reach 1.8% by 2050 (Crawford et al., Citation2021).

With an increase in age and longevity, the risk of age-related injuries and chronic diseases rises sharply (Franceschi et al., Citation2018). Due to the complexity of geriatric diseases, older adults may require diverse care, ranging from physical nursing services to mental health support, over an extended period (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Citation2016). In this context, governments and healthcare sectors face a challenge in striking a balance between managing increasing care costs and enhancing the health and well-being of the older population.

The World Health Organization (Citation2017) has emphasized the importance of facilitating home and community-based care to allow older adults to “age in place” with dignity and support. Due to the need to achieve cost savings in LTC and comply with the World Health Organization (Citation2017) recommendation, many countries are now prioritizing home and community-based services (HCBS) at a national level. For example, in the United States, state Medicare programs, which cover care provided in nursing facilities, now pay for more HCBS care than any other insurer due to Medicare enrollees’ preferences for care in the community (McLean et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, as part of the American Rescue Plan of 2021, an increased 10% of Medicaid-funded was allocated to states to improve the accessibility of Medicaid recipients to HCBS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Citation2021).

HCBS covers a range of services provided in an individual’s home or community setting. These services are designed primarily to help older adults and people with disabilities remain in their homes for as long as possible (Anderson et al., Citation2018). Given the lack of identifying HCBS by type of service, Peebles and Bohl (Citation2014) summarized 18 categories of HCBS from Medicaid administrative files, respectively are case management, round-the-clock services, supported employment, day services, nursing services, home-delivered meals, rent and food for live-in caregiver, home-based services, caregiver support, mental health, health and therapeutic services, services supporting participant direction, participant training, nonmedical transportation, community transition services, and equipment, technology, and modifications (Peebles & Bohl, Citation2014). The taxonomy of HCBS allows service providers and policymakers to determine exactly which services are being used by older adults, thereby fostering greater accessibility and delivery of HCBS.

The increasing focus on HCBS reflects a burgeoning shift in care preferences among the older population. Many older adults who require assistance in managing chronic diseases wish to remain in their homes or communities in familiar surroundings rather than reside in institutional care facilities (Kane, Citation2001; Marek & Rantz, Citation2000).HCBS helps to reduce institutionalization and hospitalization among older adults and improve their psychological well-being (Puyat et al., Citation2022, Tomita et al., Citation2010; Wiles et al., Citation2012). “Aging in place” is increasingly favored not only by older adults but also by the healthcare industry. For healthcare sectors and service providers, HCBS is associated with significantly lower healthcare costs compared to those associated with institutional care (Wysocki et al., Citation2015). A major advantage for HCBS from government and state perspectives is that healthcare outcomes are equivalent to those attainable in institutional settings at a reduced cost (Laporte et al., Citation2007).

To improve HCBS uptake in the community and enable caregivers to offer more targeted care services to older adults, the characteristics of HCBS users must be understood, including the factors that influence HCBS utilization. Knowledge of the factors that determine service utilization is particularly important for government policymakers in light of the significant growth worldwide in the aging population. Such knowledge can aid the formulation of policies and allocation of resources in relation to care provision for older adults and HCBS (E. Y. Kim et al., Citation2006). It can also aid the formulation of plans for efficiently managing the expected increase in the demand for LTC (Sugimoto et al., Citation2017). Successful implementation of programs and interventions aimed at improving HCBS is largely dependent on understanding the factors that influence the utilization of these services.

At present, the factors influencing HCBS utilization are not entirely clear. Most previous research has explored the influence of individual-level factors, such as age, economic status, and health status, on the utilization of LTC services (Alkhawaldeh et al., Citation2014; Archibong et al., Citation2020; Steinbeisser et al., Citation2018). However, factors beyond the individual level may explain the utilization of HCBS. Although some previous studies have focused on the impact of contextual factors on HCBS utilization, these studies have failed to capture the holistic aspects of HCBS utilization by focusing only on a single predictor or just a few predictors (Peng et al., Citation2020; Stewart et al., Citation2006). Drawing on an ecological perspective, this review aims to present a thorough and integrated overview of multilevel factors associated with HCBS utilization by older adults, which is a gap in the current literature. This review can advance understanding of HCBS utilization and the characteristics of HCBS users. The findings may guide policymakers and gerontological social workers to develop improved supporting measures for the older population.

The ecological model of HCBS utilization

The ecological model focuses on the interplay between individuals and their environment during the aging process. The basic principle of the ecological model is that human behavior evolves as a function of dynamic, reciprocal interactions between individuals and components of their environments that occur across time (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979, Citation1999). Based on Bronfenbrenner’s ecological system theory, the ecological model hypothesizes that health behaviors are determined not only by individual-level factors and decisions but also by system-level factors. The latter may include inter-relationships between individuals and caregivers (mesosystem), the community (exosystem), and social contexts (macrosystem) (Sallis et al., Citation2008).

In the ecological model, it is assumed that HCBS utilization is shaped by various factors at different levels of influence. The factors identified in this review were clustered into four levels of influence: individual (microsystem), inter-relationship (mesosystem), community (exosystem), and social context (macrosystem). The individual level encompasses the intrapersonal traits of the individual who utilizes HCBS. The inter-relationship level includes the interpersonal relationship between the individual and others (e.g., caregivers). The community/neighborhood level includes structures beyond family in the community. The social context level is made up of broad social elements that have an impact on HCBS utilization (e.g., race and social welfare programs).

Methods

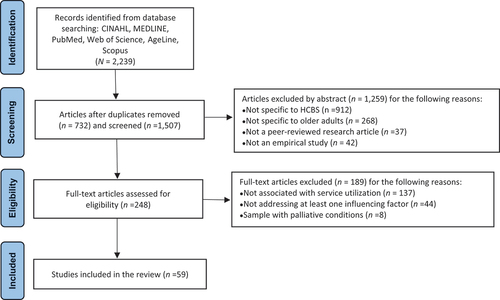

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to inform and structure the research process of this systematic review (Moher et al., Citation2009).

Search strategy

We conducted a systematic literature search of five electronic databases: CINAHL, MEDLINE, PubMed, Web of Science, and AgeLine. The search was limited to articles published from January 2013 to May 2023 because findings drawn from recent literature may be more policy-relevant to the current social climate. The search terms for HCBS were as follows: “long-term services and supports (LTSS),” “long-term care (LTC),” “home and community-based services,” “home care,” “home-based care,” and “community-based care.” The search terms of specific HCBS categories (i.e., case management, round-the-clock services, supported employment, day services, nursing services, home-delivered meals, rent and food for live-in caregiver, home-based services, caregiver support, mental health, health and therapeutic services, services supporting participant direction, participant training, nonmedical transportation, community transition services, and equipment, technology, and modifications) were also used. As keywords for older adults, the following search terms were included: “older adults,” “elderly,” “older people,” and “aged people.” To optimize the effectiveness of the search, we employed Boolean operators, which involved linking the search words with AND, OR, and NOT to combine the search terms. In this study, the term “utilization (or use)” pertained to the receipt of HCBS by older adults. As such, the scope of this review did not encompass HCBS needs, preferences, or access.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To maintain the precision and focus of this review, the inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) empirical studies with the utilization of HCBS as the dependent variable; 2) examining at least one factor in relation to the utilization of HCBS; 3) peer-reviewed journal articles written in English; 4) individuals aged 60 years and older (studies were included if more than 50% of the sample met this criterion); and 5) published between January 2013 and May 2023.

As HCBS are provided in private homes or community settings, care services provided in other residential settings, such as hospitals and 24-hour nursing homes, were not included in this review. Additional exclusion criteria were as follows: non-English studies and studies published prior to 2013; studies that focused on elderly populations diagnosed with palliative conditions because such populations would be provided with extra care; studies on older adults with dementia as there was a previous scoping review on factors influencing the use of community-based care by patients with dementia and their caregivers (Bieber et al., Citation2019); articles, interventional research, case reports, case series, and commentary papers as they did not align with the primary objective of the review; conference papers that featured only abstracts and information sourced from books or letters, as these did not offer reliable and comprehensive information.

Data extraction and analysis

The data screening process consisted of two steps, whereby articles were initially screened by their titles and abstracts and then subjected to a full-text evaluation. The first author screened the titles and abstracts and applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The second author then double-checked the screening results. All articles that passed the initial screening phase underwent comprehensive full-text screening. During this phase, both authors independently reviewed the full texts and deliberated on their key findings. In cases where discrepancies arose, a third colleague was consulted to aid in reaching a consensus between the first two reviewers. The complete texts of 248 articles were scrutinized for eligibility. Of these, 189 articles were subsequently excluded. The reasons for exclusion included studies not related to HCBS, not addressing at least a factor influencing HCBS utilization, not specific to older adults, and not containing a relevant sample (i.e., patients with palliative conditions) (). Finally, from the 59 remaining studies, we extracted data on the characteristics of the studies, including the author(s), and year, research design, research location, study sample, HCBS categories, and main findings on factors influencing HCBS utilization.

We utilized the analytical approach of narrative synthesis in the examination of the extracted data. First, we undertook a comprehensive assessment of the included studies to explore similarities and divergences in their findings. Subsequently, we conducted a thematic analysis, resulting in the identification of overarching themes relating to the influential factors affecting HCBS utilization by older adults. We then discussed the results and restructured the findings into key themes. Subsequently, we summarized the results and grouped the findings according to influential factors affecting HCBS utilization. Due to high heterogeneity (study populations, data sources, designs, and statistical methods) among the studies, we did not conduct a meta-analysis of the data. The systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42023421610), and the PRISMA checklist was employed.

Quality appraisal

We adopted the 2018 version of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for the critical appraisal of the quality of quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods research studies (Hong et al., Citation2018). This tool has previously been employed in systematic reviews to evaluate the methodological quality of various study designs, assessing a range of aspects, such as their credibility, significance, and applicability (Gopalani et al., Citation2022). Using the MMAT, we examined the rationality of the study designs, data collection methods, findings, interpretation of results, and coherence in the qualitative studies; the sample representativeness, risk of confounders, measurements, and rationality of interventions in the quantitative studies; and the rationality of mixed-method designs, integration of qualitative and quantitative components, and inconsistency of results in the mixed-method studies. Similar to the process used for screening the studies, the two authors performed independent quality appraisals, with divergence being resolved through discussion and consultation with the third reviewer if needed.

Of the 59 included studies, 34 (32 quantitative and 1 qualitative) met all the methodological quality criteria of the MMAT. 25 studies failed to meet the full quality criteria due to the lack of representativeness of the target population (Joostepn, Citation2015; Lam et al., Citation2014; Peng et al., Citation2020; Reckrey et al., Citation2023; Tocchi et al., Citation2017; Yu et al., Citation2019), inappropriate measurements (Fu & Guo, Citation2022; Gerst-Emerson & Jayawardhana, Citation2015; Gruneir et al., Citation2016; Hsu et al., Citation2021; Huang et al., Citation2023; Miller et al., Citation2023; Pepin et al., Citation2017; Robinson et al., Citation2021; Rodríguez, Citation2014; Van Cleve & Degenholtz, Citation2022; Wu et al., Citation2014; Yu et al., Citation2020), and not controlling for potential confounders (Brown et al., Citation2014; Chamut et al., Citation2021; Fisher et al., Citation2016; Gruneir et al., Citation2016; Hsu et al., Citation2021; Jeffares et al., Citation2022; Lee et al., Citation2015; Reckrey et al., Citation2020).

Results

Description of included studies

provides a summary of various aspects of the included studies (n = 59). The research design of these studies included 43 cross-sectional surveys, 14 longitudinal cohort studies, one panel study, and one qualitative design. The sample sizes of the included studies ranged from 28 to 376,421. The participants in the 59 studies were recruited from the United States (n = 21), Australia (n = 4), Japan (n = 4), Canada (n = 3), Taiwan (n = 5), China (n = 6), Europe (n = 4), Germany (n = 1), Netherland (n = 1), Norway (n = 1), Sweden (n = 1), Spain (n = 2), Switzerland (n = 1), Austria (n = 1), Ireland (n = 2), England (n = 1) and Israel (n = 1).

Table 1. Summary of the included studies.

In terms of the HCBS categories that were used by older adults, home-based services (i.e., personal care, home-based habilitation, chore, homemaker, and companion) were the most frequently discussed category (n = 47). Except for home-based services, Other HCBS categories typically examined include nursing (n = 20), day services (n = 17), caregiver support (n = 13), home-delivered meals (n = 16), and health and therapeutic services (e.g., physician services, counseling, and dental services) (n = 14).

Regarding the theoretical framework utilized in the reviewed studies, it is noteworthy that a majority of the studies (n = 35) did not explicitly adopt a specific theory or model. However, among the studies that did employ a theoretical framework to examine HCBS utilization, the most commonly utilized model was Andersen’s behavioral model (n = 20). In addition to Andersen’s behavioral model, several other theories or models were employed in the reviewed studies. Specifically, Peña-Longobardo et al. (Citation2021) used the Hedonic Adaptation Prevention model to explore HCBS utilization. Kashiwagi et al. (Citation2013) applied the Van Houtven and Norton model in their study. Ewen et al. (Citation2017) incorporated Lawton’s ecological model, while Huang et al. (Citation2023) drew on institutional theory and welfare pluralism theory.

Individual-level factors

Age

Age emerged as the most examined factor associated with HCBS utilization in 17 studies (Almazán-Isla et al., Citation2017; Balia & Brau, Citation2014; Davis et al., Citation2013; Hasche et al., Citation2013; Hu et al., Citation2022; Huang et al., Citation2023; Kalwij et al., Citation2014; Lee et al., Citation2015; Lehning et al., Citation2013; F. Li et al., Citation2017; Murphy et al., Citation2015; Rodríguez, Citation2014; Schmidt, Citation2017; Sonnega et al., Citation2017; Steinbeisser et al., Citation2022; Tocchi et al., Citation2017; Yu et al., Citation2019). All these studies indicated a positive relationship between advancing age and increasing utilization of HCBS. This can be explained by the biological approach, which indicates that the increased frailty with aging can explain the increased reliance on HCBS. Of these studies, one involved a comparison of service utilization between institutional care and HCBS (Schmidt, Citation2017). According to this study, younger elders, that is, those aged 60 years, were more likely to use HCBS instead of institutional care than those aged 70 or above.

Gender

Gender is often linked to disparities in economic gain and access to education, particularly over an extended period, which eventually affects healthcare utilization (Vlassoff, Citation2007). Seven of the included studies examined the relationship between gender and HCBS utilization, revealing that older females tend to utilize more HCBS compared to older males (Fu & Guo, Citation2022; Hsu et al., Citation2021; Lee et al., Citation2015; F. Li et al., Citation2017; H. Li et al., Citation2022; Rodríguez, Citation2014; Shih et al., Citation2020). Additionally, researchers have observed gender differences in the utilization of various HCBS categories. Specifically, older females tend to use more home-based services while utilizing fewer home-delivered meals and day services (Van Cleve & Degenholtz, Citation2022).

Education

Five of the included studies revealed a positive association between higher education and the utilization of HCBS (Fu & Guo, Citation2022; H. Li et al., Citation2022; Steinbeisser et al., Citation2022, Young et al., Citation2022; Yu et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, the findings of another study indicated that individuals utilizing HCBS had higher levels of education compared to those receiving institutional care (Wu et al., Citation2014).

Financial situation

The relationship between financial situation and the utilization of HCBS varied across the included studies. Six studies suggested that older adults with lower incomes or wealth tended to use HCBS more than those with better financial situations (Floridi et al., Citation2021; Hu et al., Citation2022; Lee et al., Citation2015; F. Li et al., Citation2017; Rahman et al., Citation2019, Tokunaga et al., Citation2015; Shih et al., Citation2020). However, four other studies found a significant association between higher income and greater use of HCBS (Dong et al., Citation2021; Fu & Guo, Citation2022; Kashiwagi et al., Citation2013; S. A. Kim et al., Citation2022). Additionally, one study comparing users of HCBS, and institutional care revealed higher odds of older adults with higher incomes utilizing HCBS compared to those with lower incomes (Schmidt, Citation2017).

Physical health

Eight studies indicated that older adults with poorer performance in activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) tended to utilize more HCBS (Døhl et al., Citation2016; Fu & Guo, Citation2022; Kalwij et al., Citation2014; Lam et al., Citation2014; Murphy et al., Citation2015; Shih et al., Citation2020; Young et al., Citation2022; Yu et al., Citation2020). Additionally, nine studies revealed a positive association between the presence of chronic conditions and the utilization of HCBS (Døhl et al., Citation2016; Dupraz et al., Citation2020; Fisher et al., Citation2016; Fu & Guo, Citation2022; Kashiwagi et al., Citation2013; Rahman et al., Citation2019; Reckrey et al., Citation2023; Rodríguez, Citation2014; Young et al., Citation2022). Moreover, six studies analyzing functional and cognitive limitations found a higher utilization of HCBS among older adults with more severe limitations in these areas (Brown et al., Citation2014; Hasche et al., Citation2013; Hsu et al., Citation2021; Jeffares et al., Citation2022; Sonnega et al., Citation2017; Young et al., Citation2022). Three studies revealed the impact of self-rated health on HCBS utilization (Rahman et al., Citation2019; Rodríguez, Citation2014; Sonnega et al., Citation2017). Older adults who rated their health status as poor or fair were significantly more likely to use LTC than those with good self-rated health. Several studies have also demonstrated that disability and frailty serve as noteworthy predictors for the utilization of HCBS (Almazán-Isla et al., Citation2017; Balia & Brau, Citation2014; Chesney et al., Citation2021; Davis et al., Citation2013; Yu et al., Citation2019).

Mental health concerns

Mental health plays a significant role in influencing the utilization of HCBS for older adults (Ewen et al., Citation2017). Four studies consistently demonstrated that older adults with more severe symptoms of depression are more likely to use HCBS (Hasche et al., Citation2013; Lam et al., Citation2014; Pepin et al., Citation2017; Shih et al., Citation2020). Additionally, loneliness has been identified as another factor positively associated with the utilization of HCBS (Gerst-Emerson & Jayawardhana, Citation2015).

Prior service utilization

Using HCBS was significantly predicted by previous service use. Five studies reported that regular hospital visits and hospitalization were linked to increased HCBS utilization (Hsu et al., Citation2021; Kashiwagi et al., Citation2013; Liang et al., Citation2019; Reckrey et al., Citation2020; Young et al., Citation2022). Also, it has been discovered that the previous experience of using HCBS has been found to be a predictor of subsequent HCBS utilization (Chamut et al., Citation2021; F. Li et al., Citation2017).

Others

Physical activities (i.e., walking and exercise) have been associated with a reduction in the use of HCBS (Steinbeisser et al., Citation2022). Proximity to death was positively related to HCBS utilization (Balia & Brau, Citation2014; Reckrey et al., Citation2020). The existence of a safety alarm increased the use of HCBS (Døhl et al., Citation2016). Additionally, unmet basic needs have been identified as a positive determinant of HCBS utilization (Fu & Guo, Citation2022; Joostepn, Citation2015).

Inter-relationship level factors

Marital status

Eight empirical studies have looked at relationships between marital status and HCBS use, and their findings consistently indicated that older adults who are separated, divorced, or single had a greater likelihood to use HCBS than those who are married (Hsu et al., Citation2021; Larsson et al., Citation2014; Lee et al., Citation2015; F. Li et al., Citation2017; Peña-Longobardo et al., Citation2021; Rahman et al. Furthermore, Wu et al. (Citation2014) study found that older adults who used HCBS were less likely to be single than those who got care in institutional settings.

Living arrangements

It was discovered by 12 studies that living arrangements have an impact on the use of HCBS (Døhl et al., Citation2016; Kashiwagi et al., Citation2013; Larsson et al., Citation2014; Lee et al., Citation2015; Lehning et al., Citation2013; Murphy et al., Citation2015; Reckrey et al., Citation2023; Robinson et al., Citation2021; Steinbeisser et al., Citation2022; Van Cleve & Degenholtz, Citation2022; Weaver & Roberto, Citation2017; Yu et al., Citation2020). The results of these studies revealed that older adults who live alone typically used more HCBS than those who live with others. In addition, older adults living with their relatives used more HCBS than older adults living with their spouses (Weaver & Roberto, Citation2017).

Social support

Social support, encompassing perceived support from family members, friends, and significant others, has been examined in relation to the utilization of HCBS in seven studies. These studies suggested that receiving social support was associated with lower utilization of HCBS among older adults (Guzzardo & Sheehan, Citation2013; Huang et al., Citation2023; Kalwij et al., Citation2014; Lam et al., Citation2014; H. Li et al., Citation2022; Van der Burg et al., Citation2020; Weaver & Roberto, Citation2017). Other factors that support older adults, such as social networks and social capital, have also been shown to be related to HCBS utilization (Lee et al., Citation2015; Peng et al., Citation2020).

Caregiver

Four studies indicated that having caregivers is positively and statistically significantly associated with the use of HCBS (McKenzie et al., Citation2014; Robinson et al., Citation2021; Shih et al., Citation2020; Yu et al., Citation2020). In addition to the presence of caregivers, the influence of caregiver gender on HCBS utilization among older adults has been examined. Tokunaga et al. (Citation2015) reported that female caregivers were associated with lower utilization of HCBS. Furthermore, Weaver and Roberto (Citation2017) conducted a study that revealed that spousal caregiving resulted in reduced utilization of HCBS. Another aspect examined in the research is the impact of caregiver burden, specifically caregiver depression, on HCBS utilization. Brown et al. (Citation2014) found that increased caregiver burden, such as experiencing caregiver depression, was associated with a higher use of HCBS.

Community level factors

Place of residence

Six studies consistently found that HCBS utilization was significantly higher among individuals living in urban areas or developed regions (Almazán-Isla et al., Citation2017; Fu & Guo, Citation2022; Huang et al., Citation2023; Miller et al., Citation2023; Reckrey et al., Citation2020; Van Cleve & Degenholtz, Citation2022). However, three studies revealed an opposite finding, suggesting that rural residence was associated with increased use of HCBS (Hasche et al., Citation2013; Rahman et al., Citation2019; Yu et al., Citation2020). Moreover, the availability of caring resources in a specific area has been found to influence HCBS utilization. Specifically, older adults residing in regions with sufficient LTC beds and a high proportion of certified nursing aides were less likely to rely on HCBS (Floridi et al., Citation2021; Fu & Guo, Citation2022; Shih et al., Citation2020).

Neighborhood/housing problems

Two studies, conducted by Hu et al. (Citation2022) and Lehning et al. (Citation2013), have examined the relationship between neighborhood or housing problems (e.g., a shortage of space, noise from neighbors, and heavy traffic) and the utilization of HCBS among older adults. These studies found that experiencing neighborhood or housing problems was associated with higher utilization of HCBS. Additionally, another study suggested that older adults were less inclined to use HCBS if there were language barriers and other communication difficulties in the neighborhood (Guzzardo & Sheehan, Citation2013).

Social contextual level factors

Race/Ethnicity

The impact of race/ethnicity on the utilization of HCBS has been investigated through seven empirical studies. These studies have consistently demonstrated that older adults belonging to nonwhite races tended to exhibit higher levels of HCBS utilization (Davis et al., Citation2013; Hasche et al., Citation2013; Hu et al., Citation2022; Lee et al., Citation2015; Sonnega et al., Citation2017; Tocchi et al., Citation2017; Van Cleve & Degenholtz, Citation2022). In particular, the non-Hispanic Black race was strongly linked to higher use of HCBS when compared to white non-Hispanic people (Sonnega et al., Citation2017; Van Cleve & Degenholtz, Citation2022).

Social welfare programs

According to three studies, enrollment in LTC insurance is significantly correlated with a rise in the use of HCBS (Liang et al., Citation2019; Mellor et al., Citation2023; Takahashi, Citation2022). Moreover, Tsai (Citation2015) discovered that higher social security income had a positive effect on the likelihood that older persons would choose HCBS.

Discussion

In light of the rapid growth of the aging population, HCBS utilization is anticipated to play a pivotal role in supporting older adults who wish to age in place. This review encompasses a selection of 59 academic articles published between January 1, 2013, and April 1, 2023, focusing on the examination of factors that influence the utilization of HCBS among older adults. Through meticulous analysis, this review identified a total of 15 common factors that significantly impact the utilization of HCBS. Furthermore, the review emphasizes the intricate interplay of these multifaceted factors across different levels of the system, collectively shaping the utilization of HCBS by older adults. While factors at the individual- level remain highly significant, our findings indicate that these individual-level factors can be notably influenced by factors at other levels of the system. For instance, the availability of community-based resources for caregiving was found to moderate the relationship between unmet needs and the utilization of HCBS among older adults (Fu & Guo, Citation2022). Moreover, disability, serving as a proxy for physical health, was found to partially mediate the effects of age on the subsequent utilization of HCBS (Yu et al., Citation2019). These findings emphasize the importance of considering not only individual-level factors but also their interaction with other factors to enhance the uptake of HCBS among older adults.

One important theme revealed by this study is the dynamic nature of HCBS utilization. The way older persons use HCBS can change as their circumstances and conditions change over time. The results of this study confirm the importance of individual-level factors in shaping HCBS utilization. Older adults’ characteristics, such as age, gender, and physical health, were found to be significant predictors of HCBS utilization (Almazán-Isla et al., Citation2017; Hsu et al., Citation2021; Lee et al., Citation2015). However, it is critical to recognize that other factors of the wider system also have an impact on how often older adults use HCBS (Mellor et al., Citation2023; Reckrey et al., Citation2020). The study made clear how crucial it is for the usual administrative procedure to recognize and document the dynamic nature of older adults’ use of HCBS. The capacity and delivery system of HCBS can be improved in this way, allowing for better coordination and adaptation to the many and changing care demands of the older population. Understanding the intricate relationship between factors at the individual level and the wider system context brings forth valuable insights into enhancing the efficacy and adaptability of HCBS programs. This knowledge can help policymakers and practitioners create interventions that consider the changing needs and preferences of older adults, ensuring that HCBS is flexible and adaptable as they age.

Our findings shed light on the significance of quality and robustness of relationships. The factors at the inter-relationship level show a substantial correlation with the use of HCBS. While other research has highlighted the roles of spouses, children, and caregivers in HCBS utilization (Ewen et al., Citation2017; F. Li et al., Citation2017; Weaver & Roberto, Citation2017), some studies included in this review go further into these dynamics to show additional nuances. For instance, single older adults who can rely less on children – and in particular daughters – used more HCBS (Kalwij et al., Citation2014). Additionally, older women were more likely to use HCBS if they experienced changes in their co-resident caregiving situation or continued to provide care for a frail, ill, or disabled person (McKenzie et al., Citation2014). These findings highlight the importance of looking at the robustness and quality of relationships among older adults when researching how they use HCBS. To accurately identify factors associated with HCBS utilization, in addition to taking into account factors like marital status, living arrangements, and the presence of a caregiver, it is essential to evaluate the extent of social support, the caliber of family relationships, and the interactions between caregivers and recipients.

Despite the knowledge gained from this review, there are still some unknowns in terms of the factors that influence HCBS utilization among older adults. The community, which stands for a social group based on shared location, interests, and identity, is playing a more significant role in assisting older people in accessing various care resources (Siegler et al., Citation2015). Further studies may consider exploring how the community can support older adults in utilizing HCBS. Moreover, variations in HCBS utilization may result from the influence of the social milieu. Future studies can focus on how older adults from different social and cultural backgrounds engage in HCBS.

Limitations

This review makes a significant contribution because it is the first to thoroughly explore the multilevel factors associated with HCBS utilization among older adults using an ecological model. While Mah et al. (Citation2021) conducted a scope literature review to explore social factors influencing the utilization of formal home care, his review did not categorize care services and was not specific to HCBS (Mah et al., Citation2021). Our review provides a more in-depth and precise understanding of how the use of HCBS is influenced among older adults. By examining the various factors at different levels of the ecological model, we have been able to shed light on the complex dynamics that impact the utilization of HCBS services among the older population. However, it is important to interpret the findings of this study with caution. First, generalization across the studies included in this review may be problematic, given that the findings were based on research in 17 countries/regions and 59 empirical surveys, each with different LTC systems, cultural backgrounds, study designs, target populations, and assessments of factors influencing HCBS outcomes. Although a factor may have an effect in one setting, this may not apply in other settings, where the same factor may not have the same effect. For example, as the U.S. is home to many international migrants, race/ethnicity differences in service use may be pronounced. In contrast, such effects may be very weak in ethnically homogeneous countries. Although the consistency across several studies regarding the effect of specific factors on HCBS utilization provides a certain degree of confidence in the validity of the findings, each factor and its influence are better comprehended within its appropriate context.

This review focused on HCBS utilization rather than on HCBS needs, preferences, or access, and further research is warranted in these areas. This review of HCBS utilization likely did not capture older adult populations without access to care resources. Therefore, how these vulnerable older adult populations access and use HCBS deserves more exploration. Moreover, this review excluded older adults with palliative conditions. The use of care services by this group of older adults is also of great concern. In addition, although we conducted an extensive search of major gerontology and social work databases, it is plausible that some relevant studies were omitted from this review. Finally, based on our inclusion criteria, only English-language studies were considered in this review. Although this review included several studies conducted in Europe and Asia, some critical studies published in languages other than English may have been overlooked.

Conclusion

As HCBS has become the primary choice for older adults who wish to age in place, understanding the factors influencing its utilization will be vital to promoting improved health and aging policies. Despite the above limitations, this review contributes to evidence of multi-level associated factors of HCBS utilization among older adults. The findings of this review have implications for gerontological social work. Given the complexity of HCBS utilization among older adults, gerontological social workers need to incorporate ecological thinking into practice. In addition to understanding the characteristics of service users, social workers should be aware that multiple factors at various levels influence health outcomes and that these factors are interdependent. Over time, older adults may be faced with increased challenges, such as mobility difficulties and declining health, that jeopardize “aging in place.” Social workers may need to help support their clients in navigating these changes and facilitate the delivery of HCBS. For example, social workers need to consider the care resources in the community and help coordinate HCBS to ensure that they are client-tailored.

As the direct care providers of HCBS, caregivers are acknowledged for their indispensable contribution to helping older adults live in the community. Caregiving for older adults entails a great deal of responsibility and can involve multiple role transitions. Over time, these transitions, as well as the health status of the person receiving care, can affect the caregiver’s physical and mental health (Gibbons et al., Citation2014). Although some countries, such as the United States and Canada, have provided support services for caregivers, the needs of caregivers have not been adequately addressed (Swartzell et al., Citation2022). To ensure the provision of high-quality HCBS, it is critical that caregiver priorities and needs are considered in practice and decision-making. Social workers play a vital role in helping carers get the support they need. As older adults use HCBS, social workers can assist caregivers in adjusting to the changes in their surroundings and adapting to their shifting position as primary carers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alkhawaldeh, A., Holm, M. B., Qaddumi, J., Petro, W., Jaghbir, M., & Omari, O. A. (2014). A cross-sectional study to examine factors associated with primary health care service utilization among older adults in the Irbid Governorate of Jordan. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research, 2014, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/735235

- Almazán-Isla, J., Comín-Comín, M., Alcalde Cabero, E., Ruiz, C., Franco, E., Magallón, R. & Larrosa-Montañes, L. A. (2017). Disability, support and long-term social care of an elderly Spanish population, 2008–2009: An epidemiologic analysis. International Journal for Equity in Health, 16(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-016-0498-2

- Anderson, K. A., Dabelko-Schoeny, H. I., & Fields, N. L. (2018). Home-and community-based services for older adults: Aging in context. Columbia University Press.

- Archibong, E. P., Bassey, G. E., Isokon, B. E., & Eneji, R. (2020). Income level and healthcare utilization in calabar metropolis of cross river state, Nigeria. Heliyon, 6(9), e04983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04983

- Balia, S., & Brau, R. (2014). A country for old men? long-term home care utilization in Europe. Health Economics, 23(10), 1185–1212. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.2977

- Bieber, A., Nguyen, N., Meyer, G., & Stephan, A. (2019). Influences on the access to and use of formal community care by people with dementia and their informal caregivers: A scoping review. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3825-z

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1999). Environments in developmental perspective: Theoretical and operational models. In S. L. Friedman & T. D. Wachs (Eds.), Measuring environment across the life span: Emerging methods and concepts (pp. 3–28). American Psychological Association.

- Brown, E. L., Friedemann, M. L., & Mauro, A. C. (2014). Use of adult day care service centers in an ethnically diverse sample of older adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 33(2), 189–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464812460431

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2021). Implementation of American rescue plan act of 2021 section 9817: Additional support for Medicaid home and community-based services during the COVID-19 emergency. https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/smd21003.pdf

- Chamut, S., Boroumand, S., Iafolla, T. J., Adesanya, M., Fazio, E. M., & Dye, B. A. (2021). Self-reported dental visits among older adults receiving home- and community-based services. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 40(8), 902–913. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464820925320

- Chesney, T. R., Haas, B., Coburn, N., Mahar, A. L., Davis, L. E., Zuk, V., Zhao, H. Y., Wright, F., Hsu, T. A., & Hallet, J. (2021). Association of frailty with long-term homecare utilization in older adults following cancer surgery: Retrospective population-based cohort study. European Journal of Surgical Oncology, 47(4), 888–895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2020.09.009

- Congressional Budget Office. (2013). Rising demand for long-term services and supports for elderly people. https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/113th-congress-2013-2014/reports/44363-ltc.pdf

- Crawford, R., Stoye, G., & Zaranko, B. (2021). Long-term care spending and hospital use among the older population in England. Journal of Health Economics, 78, 102477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2021.102477

- Davis, W. A., Lewin, G., Davis, T. M., & Bruce, D. G. (2013). Determinants and costs of community nursing in patients with type 2 diabetes from a community-based observational study: The Fremantle Diabetes Study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50(9), 1166–1171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.11.013

- Døhl, Ø., Garåsen, H., Kalseth, J., & Magnussen, J. (2016). Factors associated with the amount of public home care received by elderly and intellectually disabled individuals in a large Norwegian municipality. Health & Social Care in the Community, 24(3), 297–308. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12209

- Dong, J., He, D., Nyman, J. A., & Konetzka, R. T. (2021). Wealth and the utilization of long-term care services: Evidence from the United States. International Journal of Health Economics and Management, 21(3), 345–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10754-021-09299-1

- Dupraz, J., Henchoz, Y., & Santos-Eggimann, B. (2020). Formal home care use by older adults: Trajectories and determinants in the Lc65+ cohort. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4867-6

- Ewen, H. H., Washington, T. R., Emerson, K. G., Carswell, A. T., & Smith, M. L. (2017). Variation in older adult characteristics by residence type and use of home- and community-based services. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(3), 330. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14030330

- Fisher, K., Griffith, L., Gruneir, A., Panjwani, D., Gandhi, S., Sheng, L. L., Gafni, A., Chris, P., Markle-Reid, M., & Ploeg, J. (2016). Comorbidity and its relationship with health service use and cost in community-living older adults with diabetes: A population-based study in Ontario, Canada. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 122, 113–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2016.10.009

- Floridi, G., Carrino, L., Glaser, K., & Kemp, C. (2021). Socioeconomic inequalities in home-care use across regional long-term care systems in Europe. The Journals of Gerontology Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(1), 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa139

- Franceschi, C., Garagnani, P., Morsiani, C., Conte, M., Santoro, A., Grignolio, A., Monti, D., Capri, M., & Salvioli, S. (2018). The continuum of aging and age-related diseases: Common mechanisms but different rates. Frontiers in Medicine, 5, 61. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2018.00061

- Fu, Y., & Guo, Y. (2022). Community environment moderates the relationship between older adults’ need for and utilisation of home- and community-based care services: The case of China. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(5), e3219–e3232. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13766

- Gerst-Emerson, K., & Jayawardhana, J. (2015). Loneliness as a public health issue: The impact of loneliness on health care utilization among older adults. American Journal of Public Health, 105(5), 1013–1019. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302427

- Gibbons, S. W., Ross, A., & Bevans, M. (2014). Liminality as a conceptual frame for understanding the family caregiving rite of passage: An integrative review. Research in Nursing & Health, 37(5), 423–436. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.21622

- Gopalani, S. V., Sedani, A. E., Janitz, A. E., Clifton, S. C., Peck, J. D., Comiford, A., & Campbell, J. E. (2022). Barriers and factors associated with HPV vaccination among American Indians and Alaska Natives: A systematic review. Journal of Community Health, 47(3), 563–575. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-022-01079-3

- Gruneir, A., Griffith, L. E., Fisher, K., Panjwani, D., Gandhi, S., Sheng, L., Patterson, C., Gafni, A., Ploeg, J., & Markle-Reid, M. (2016). Increasing comorbidity and health services utilization in older adults with prior stroke. Neurology, 87(20), 2091–2098. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000003329

- Guzzardo, M. T., & Sheehan, N. W. (2013). Puerto Rican elders’ knowledge and use of community-based long-term care services. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 56(1), 26–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2012.724759

- Hasche, L. K., Lee, M. J., Proctor, E. K., & Morrow-Howell, N. (2013). Does identification of depression affect community long-term care services ordered for older adults? Social Work Research, 37(3), 255–262. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/svt020

- Hong, Q. N., Gonzalez-Reyes, A., & Pluye, P. (2018). Improving the usefulness of a tool for appraising the quality of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 24(3), 459–467. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12884

- Hsu, B., Korda, R. J., Lindley, R. I., Douglas, K. A., Naganathan, V., & Jorm, L. R. (2021). Use of health and aged care services in Australia following hospital admission for myocardial infarction, stroke or heart failure. BMC Geriatrics, 21(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02519-w

- Huang, G., Guo, F., & Chen, G. (2023). Utilization of home-/community-based care services: The current experience and the intention for future utilization in urban China. Population Research and Policy Review, 42(4), 61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-023-09810-1

- Hu, B., Cartagena-Farias, J., & Brimblecombe, N. (2022). Functional disability and utilisation of long-term care in the older population in England: A dual trajectory analysis. European Journal of Ageing, 19(4), 1363–1373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-022-00723-0

- Jeffares, I., Rohde, D., Doyle, F., Horgan, F., & Hickey, A. (2022). The impact of stroke, cognitive function and post-stroke cognitive impairment (PSCI) on healthcare utilisation in Ireland: A cross-sectional nationally representative study. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 414. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07837-2

- Joostepn, D. M. (2015). Social work decision-making: Need factors of older adults that affect outcomes of home- and community-based services. Health & Social Work, 40(1), 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlu043

- Kalwij, A., Pasini, G., & Wu, M. (2014). Home care for the elderly: The role of relatives, friends and neighbors. Review of Economics of the Household, 12(2), 379–404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-012-9159-4

- Kane, R. A. (2001). Long-term care and a good quality of life: Bringing them closer together. The Gerontologist, 41(3), 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/41.3.293

- Kashiwagi, M., Tamiya, N., Sato, M., & Yano, E. (2013). Factors associated with the use of home-visit nursing services covered by the long-term care insurance in rural Japan: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatrics, 13(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-13-1

- Kim, S. A., Babazono, A., Fujita, T., & Jamal, A. (2022). Impact of income disparity on utilization of home-based care services among older adults in Japan: A retrospective cohort study. Population Health Management, 25(5), 639–650. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2022.0110

- Kim, E. Y., Cho, E., & June, K. J. (2006). Factors influencing use of home care and nursing homes. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 54(4), 511–517. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03839.x

- Lam, B. T., Cervantes, A. R., & Lee, W. K. (2014). Late-life depression, social support, instrumental activities of daily living, and utilization of in-home and community-based services in older adults. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 24(4), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2013.849221

- Laporte, A., Croxford, R., & Coyte, P. C. (2007). Can a publicly funded home care system successfully allocate service based on perceived need rather than socioeconomic status? A Canadian experience. Health & Social Care in the Community, 15(2), 108–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00672.x

- Larsson, K., Kåreholt, I., & Thorslund, M. (2014). Care utilisation in the last years of life in Sweden: The effects of gender and marital status differ by type of care. European Journal of Ageing, 11(4), 349–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-014-0320-1

- Lee, J. S., Shannon, J., & Brown, A. (2015). Characteristics of older Georgians receiving older Americans act nutrition program services and other home- and community-based services: Findings from the Georgia Aging Information Management System (GA AIMS). Journal of Nutrition in Gerontology and Geriatrics, 34(2), 168–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/21551197.2015.1031595

- Lehning, A. J., Kim, M. H., & Dunkle, R. E. (2013). Facilitators of home and community-based service use by urban African American elders. Journal of Aging and Health, 25(3), 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264312474038

- Liang, Y., Liang, H., & Corazzini, K. N. (2019). Predictors and patterns of home health care utilization among older adults in Shanghai, China. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 38(1), 29–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621424.2018.1483280

- Li, F., Fang, X., Gao, J., Ding, H., Wang, C., Xie, C., Yang, Y., Jin, C., & Laks, J. (2017). Determinants of formal care use and expenses among in-home elderly in Jing’an district, Shanghai, China. PLoS One, 12(4), e0176548. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176548

- Li, H., Xu, L., Chi, I., & Yin, Y. (2022). Use of home and community based services in urban China: Experiences of older adults with disabilities. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 37(1), 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-021-09444-w

- Mah, J. C., Stevens, S. J., Keefe, J. M., Rockwood, K., & Andrew, M. K. (2021). Social factors influencing utilization of home care in community-dwelling older adults: A scoping review. BMC Geriatrics, 21(1), 145. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02069-1

- Marek, K. D., & Rantz, M. J. (2000). Aging in place: A new model for long-term care. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 24(3), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006216-200004000-00003

- McKenzie, S. J., Lucke, J. C., Hockey, R. L., Dobson, A. J., & Tooth, L. R. (2014). Is use of formal community services by older women related to changes in their informal care arrangements? Ageing & Society, 34(2), 310–329. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X12000992

- McLean, K. J., Hoekstra, A. M., & Bishop, L. (2021). United States Medicaid home and community-based services for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A scoping review. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 34(3), 684–694. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12837

- Mellor, J., Cunningham, P., Britton, E., & Walker, L. (2023). Use of home and community-based services after implementation of Medicaid managed long term services and supports in Virginia. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2023.2183678

- Miller, K. E. M., Ornstein, K. A., & Coe, N. B. (2023). Rural disparities in use of family and formal caregiving for older adults with disabilities. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 71(9), 2865–2870. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.18376

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097.

- Murphy, C. M., Whelan, B. J., & Normand, C. (2015). Formal home-care utilisation by older adults in Ireland: Evidence from the Irish longitudinal study on ageing (TILDA). Health & Social Care in the Community, 23(4), 408–418. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12157

- Peebles, V., & Bohl, A. (2014). The HCBS taxonomy: A new language for classifying home- and community-based services. Medicare & Medicaid Research Review, 4(3), mmrr2014-004-03–b01. https://doi.org/10.5600/mmrr.004.03.b01

- Peña-Longobardo, L. M., Rodríguez-Sánchez, B., & Oliva-Moreno, J. (2021). The impact of widowhood on wellbeing, health, and care use: A longitudinal analysis across Europe. Economics & Human Biology, 43, 101049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2021.101049

- Peng, C., Burr, J. A., Kim, K., & Lu, N. (2020). Home and community-based service utilization among older adults in urban China: The role of social capital. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 63(8), 790–806. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2020.1787574

- Pepin, R., Leggett, A., Sonnega, A., & Assari, S. (2017). Depressive symptoms in recipients of home- and community-based services in the United States: Are older adults receiving the care they need? The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(12), 1351–1360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2017.05.021

- Puyat, J. H., Mohebbian, M., Gupta, A., Ellis, U., Ranote, H., Almeida, A., Ridgway, L., Vila-Rodriguez, F., & Kazanjian, A. (2022). Home-based and community-based activities that can improve mental wellness: A protocol for an umbrella review. BMJ Open, 12(12), e065564. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-065564

- Rahman, M., Efird, J. T., & Byles, J. E. (2019). Patterns of aged care use among older Australian women: A prospective cohort study using linked data. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 81, 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2018.11.010

- Reckrey, J. M., Yang, M., Kinosian, B., Bollens-Lund, E., Leff, B., Ritchie, C., & Ornstein, K. (2020). Receipt of home-based medical care among older beneficiaries enrolled in fee-for-service medicare. Health Affairs, 39(8), 1289–1296. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01537

- Reckrey, J. M., Zhao, D., Stone, R. I., Ritchie, C. S., Leff, B., & Ornstein, K. A. (2023). Use of home-based clinical care and long-term services and supports among homebound older adults. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 24(7), 1002–1006.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2023.03.016

- Robinson, K. N., Menne, H. L., Gaeta, R., & Kemp, C. (2021). Use of informal support as a predictor of home- and community-based services utilization. The Journals of Gerontology Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(1), 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa046

- Rodríguez, M. (2014). Use of informal and formal care among community dwelling dependent elderly in Spain. The European Journal of Public Health, 24(4), 668–673. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckt088

- Sallis, J. F., Owen, N., & Fisher, E. B. (2008). Ecological models of health behavior. In K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, & K. Viswanath (Eds.), Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice (4th ed. pp. 465–486). Jossey-Bass.

- Schmidt, A. E. (2017). Analysing the importance of older people’s resources for the use of home care in a cash-for-care scheme: Evidence from Vienna. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(2), 514–526. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12334

- Shih, C. M., Wang, Y. H., Liu, L. F., & Wu, J. H. (2020). Profile of long-term care recipients receiving home and community-based services and the factors that influence utilization in Taiwan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(8), 2649. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17082649

- Siegler, E. L., Lama, S. D., Knight, M. G., Laureano, E., & Reid, M. C. (2015). Community-based supports and services for older adults: A primer for clinicians. Journal of Geriatrics, 2015, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/678625

- Sonnega, A., Robinson, K., & Levy, H. (2017). Home and community-based service and other senior service use: Prevalence and characteristics in a national sample. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 36(1), 16–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621424.2016.1268552

- Steinbeisser, K., Grill, E., Holle, R., Peters, A., & Seidl, H. (2018). Determinants for utilization and transitions of long-term care in adults 65+ in Germany: Results from the longitudinal KORA-Age study. BMC Geriatrics, 18(1), 172. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0860-x

- Steinbeisser, K., Schwarzkopf, L., Schwettmann, L., Laxy, M., Grill, E., Rester, C., Peters, A., & Seidl, H. (2022). Association of physical activity with utilization of long-term care in community-dwelling older adults in Germany: Results from the population-based KORA-Age observational study. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 19(1), 102. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-022-01322-z

- Stewart, M. K., Felix, H., Dockter, N., Perry, D. M., & Morgan, J. R. (2006). Program and policy issues affecting home and community-based long-term care use: Findings from a qualitative study. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 25(3–4), 107–127. https://doi.org/10.1300/J027v25n03_07

- Sugimoto, K., Kashiwagi, M., & Tamiya, N. (2017). Predictors of preferred location of care in middle-aged individuals of a municipality in Japan: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 352. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2293-1

- Swartzell, K. L., Fulton, J. S., & Crowder, S. J. (2022). State-level Medicaid 1915(c) home and community-based services waiver support for caregivers. Nursing Outlook, 70(5), 749–757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2022.06.005

- Takahashi, M. (2022). Insurance coverage, long-term care utilization, and health outcomes. The European Journal of Health Economics, 24(8), 1383–1397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-022-01550-x

- Tocchi, C., McCorkle, R., & Dixon, J. (2017). Frailty determinants in two long-term care settings: Assistant living facilities and home and community-based programs. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 36(3–4), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621424.2016.1264342

- Tokunaga, M., Hashimoto, H., & Tamiya, N. (2015). A gap in formal long-term care use related to characteristics of caregivers and households. In under the public universal system in Japan: 2001-2010. Health Policy (Vol. 119, no. 6, pp. 840–849). Amsterdam, Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.10.015(

- Tomita, N., Yoshimura, K., & Ikegami, N. (2010). Impact of home and community-based services on hospitalisation and institutionalisation among individuals eligible for long-term care insurance in Japan. BMC Health Services Research, 10(1), 345. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-10-345

- Tsai, Y. (2015). Social security income and the utilization of home care: Evidence from the social security notch. Journal of Health Economics, 43, 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.10.001

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2016). The growing need for long-term care: Assumptions and realities. https://www.un.org/development/desa/ageing/news/2016/09/briefing-paper-growing-need-for-long-term-care-assumptions-and-realities/

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2022). World population prospects 2022: Summary of results. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/wpp2022_summary_of_results.pdf

- Van Cleve, R., & Degenholtz, H. B. (2022). Patterns of home and community-based service use by beneficiaries enrolled in the Pennsylvania Medicaid aging waiver. Journal of Applied Gerontology: The Official Journal of the Southern Gerontological Society, 41(8), 1870–1877. https://doi.org/10.1177/07334648221094578

- Van der Burg, D. A., Diepstraten, M., & Wouterse, B. (2020). Long-term care use after a stroke or femoral fracture and the role of family caregivers. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 150. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01526-7

- Vlassoff, C. (2007). Gender differences in determinants and consequences of health and illness. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 25(1), 47–61.

- Weaver, R. H., & Roberto, K. A. (2017). Home and community-based service use by vulnerable older adults. The Gerontologist, 57(3), 540–551. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnv149

- Wiles, J. L., Leibing, A., Guberman, N., Reeve, J., & Allen, R. E. (2012). The meaning of “aging in place” to older people. The Gerontologist, 52(3), 357–366. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnr098

- World Health Organization. (2017, January 2). Global strategy and action plan on ageing and health. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241513500

- Wu, C. Y., Hu, H. Y., Huang, N., Fang, Y. T., Chou, Y. J., Li, C. P., & Forloni, G. (2014). Determinants of long-term care services among the elderly: A population-based study in Taiwan. PLoS One, 9(2), e89213. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089213

- Wysocki, A., Butler, M., Kane, R. L., Kane, R. A., Shippee, T., & Sainfort, F. (2015). Long-term services and supports for older adults: A review of home and community-based services versus institutional care. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 27(3), 255–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2015.1024545

- Young, Y., Hsu, W. H., Chen, Y. M., Chung, K. P., Chen, H. H., Kane, C., Shayya, A., Schumacher, P., & Yeh, Y. P. (2022). Determinants associated with medical-related long-term care service use among community-dwelling older adults in Taiwan. Geriatric Nursing (New York, NY), 48, 58–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2022.08.009

- Yu, H. W., Tu, Y. K., & Chen, Y. M. (2019). Sociodemographic characteristics, disability trajectory, and health care and long-term care utilization among middle-old and older adults in Taiwan. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 82, 161–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2019.01.019

- Yu, H. W., Tu, Y.-K., Kuo, P.-H., & Chen, Y.-M. (2020). Use of home- and community-based services in Taiwan’s National 10-year long-term care plan. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 39(7), 722–730. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464818774642