ABSTRACT

Empowerment is central in gerontological social work. Operationalizing empowerment from the perspective of the target population is important to align with context specific interpretations of what empowerment means. This study aims at operationalizing psychological empowerment from the perspective of older people. A design was chosen that is based on the concept mapping method, though tailored to accommodate the specific principles we assume in empowerment research and to align with target specific conditions that come to play with older persons. The results show an empowerment with 58 statements divided over four components of empowerment; emotional, cognitive, relational and behavioural component.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

As discussed extensively in previous research, empowerment plays a central role in social work, either as an intended outcome or as a mechanism that can lead to the achievement of social work goals (International Federation of Social Work, Citation2014; Noordink et al., Citation2021, Citation2023; Van Regenmortel, Citation2002). Measurements can help us better understand the extent to which social work actually leads to the achievement of these ambitions (i.e., Noordink et al., Citation2023).

It is important to distinguish between empowerment as a value orientation and empowerment as a theoretical model (Rappaport, Citation1987; Zimmerman, Citation2000; de Kreek, Citation2014). Empowerment as a value orientation influences how we look at power, at control and at emancipation, supported by ethical values such as inclusion, social justice, democracy, pluralism and diversity (de Kreek, Citation2014; Van Regenmortel, Citation2011). Empowerment as a theoretical model offers us the framework by which we can get a better understanding of how the construct, for this study specifically psychological empowerment, can be theorized, defined and operationalized (Zimmerman, Citation2000). A basic principle within empowerment theory is that a distinction can be made between three levels of analysis, namely psychological empowerment, organizational empowerment and community empowerment (Rappaport, Citation1984; Zimmerman, Citation2000). This study focuses on psychological empowerment, as at this level the construct integrates perceptions of personal control, a critical understanding of the sociopolitical environment and proactive behavior in life (Zimmerman, Citation1995); aspects that are important when regarding empowerment of older people, which will be elaborated on later in the introduction.

Psychological empowerment

Psychological empowerment is sometimes mistaken for individual empowerment, treating the concept as a personality variable, neglecting the fundamental contextual basis (Christens, Citation2019; Riger, Citation1993; Zimmerman, Citation1990). However, psychological empowerment is inseparable from context, relations and interconnections (Christens, Citation2012, Citation2019; Zimmerman, Citation1990). Thus, measuring instruments should account for this multi-levelness in the operationalization of the construct. Zimmerman (Citation1995) laid the foundation for one of the most influential frameworks used to explain and study psychological empowerment by distinguishing between intrapersonal, interactional and behavioral components. The intrapersonal component refers to how people think about themselves and self-perceptions of control and one’s competence in exerting influence (Christens, Citation2012). It includes self-efficacy, motivation to control, perceived control and competence, and mastery (Christens, Citation2012; Zimmerman, Citation1995). The interactional component focuses on critical understandings of personal dynamics in social and political situations, of causality and affairs, and of societal injustices and power dynamics (Christens, Citation2012; Freire, Citation1982; Speer & Peterson, Citation2000; Zimmerman, Citation1995). The behavioral component relates to actions taken to directly influence outcomes and to participation in the life of a community, particularly in democratic decision-making processes (Christens, Citation2012; Zimmerman, Citation1995).

The relational component of psychological empowerment

There is great consensus in literature that empowerment is by definition a relational construct (Christens, Citation2012; Van Regenmortel, Citation2002; Zimmerman,Citation1990, Citation1995). Power and control are often developed and exercised through relationships and relationships are not only external components of the context in which people are active, they also form the basis for experiences and for the construction of our identity (Christens, Citation2012).

However, this relational aspect is often insufficiently made explicit in operationalizations of empowerment, and is therefore less explicit in measurements of empowerment (Christens, Citation2012; Noordink et al., Citation2021). This may lead to the question whether current operationalizations do sufficient justice to the widely recognized relational aspect of empowerment. As such, some researchers choose to expand on the aforementioned three-dimensional structure of psychological empowerment (Zimmerman, Citation1995) by adding a relational component as a fourth component, as it is believed that adding this fourth component offers a framework that makes it possible to make the relational aspect of empowerment explicit. The relational component is explained as relating to interpersonal transactions and processes that undergird the effective exercise of control and power (Christens, Citation2012).

Conceptualizing and positioning empowerment in research

The all-purpose and versatile interpretation of “empowerment” brings forth a danger of losing its substantive value if we do not maintain a clearly defined theoretical framework as a starting point for research activities (Noordink et al., Citation2019, Citation2023; Van Regenmortel, Citation2002). This ensures that people mean the same thing when they talk about empowerment. However, it is the people concerned who give meaning to how empowerment is interpreted and manifested in their lives. Empowerment as a context-specific construct deserves translations that aligns with the context and perceptions of the target population (Akey et al., Citation2000; Florin & Wandersman, Citation1990; Rappaport, Citation1987; Rogers et al., Citation1997; Spreitzer, Citation1995; Zimmerman, Citation1995). This means it is important to align it with clear theoretical frameworks and move toward context-specific operationalizations.

The socio-political level of empowerment also includes the responsibility of social workers to give people a voice, a responsibility that translates into social work research. Giving voice to people goes beyond merely involving them in the process of operationalizing the construct to be measured. Empowerment principles in research suggest that opportunities for empowering experiences for service users should be created when the target population is involved in empowerment evaluation (Cochran, Citation1992; Fetterman, Citation2005; Florin & Wandersman, Citation1990; Wandersman et al., Citation2005). The fundamental involvement of the target population in empowerment research can help them gain control over affairs and perceive a sense of influence in decision-making processes. Of course, the extent to which participants truly gain control and power depends on how the research is conducted (Fetterman, Citation2005; Florin & Wandersman, Citation1990). This also means that researchers’ and participants’ roles and positions in empowerment research can alternate and are not always static (Chavis & Wandersman, Citation1986; Van Regenmortel et al., Citation2016). Rappaport (Citation1987) emphasizes this when describing how empowerment theory can self-consciously be seen as a world view theory, which means the target population are to be treated as collaborators and researchers can be seen as participants.

Empowerment of older people

Empowerment is also a central concept in care for older people. It gives meaning and provides a framework for a value orientation in which people gain or maintain control over decisions and actions that affect their health in relation to their aging process (Fisher & Gosselink, Citation2008; Hupkens et al., Citation2016; Lloyd, Citation1991; Maertens & Desmet, Citation2015; Van Regenmortel, Citation2002). Self-determination, a sense of control and agency – all aspects of empowerment – are key to enabling older people to thrive in the face of age-related challenges, to be able to maintain agency and control over their lives for as long as possible (Ng & Ho, Citation2020; Nyende et al., Citation2023).

When communicating about older people and conceptualizing their care, it is common to encounter language that perpetuates negative stereotypes. Such language is the starting point for ageism and age discrimination (De Witte & Van Regenmortel, Citation2019). Empowerment can counteract mechanisms of ageism that tend to frame aging as a process of decline, dependency and vulnerability and reinstate a focus on older people’s strengths, power and opportunities. In this context, we believe that viewing the process of aging from an empowerment perspective repudiates negative images of aging (De Witte & Van Regenmortel, Citation2023; Van Gorp, Citation2013). Empowerment in this regard emphasizes the strengthening process of aging in our society and the value of fostering connections in this regard. It also demonstrates that vulnerability and mastery can go hand in hand (De Witte & Van Regenmortel, Citation2023).

Furthermore and in line with the aforementioned relational dimension of empowerment, we know that relationships, connectivity and interpersonal connection are important for older people. Both in maintaining a sense of belonging and a sense of worth, as well as in supporting older people as they age (Clarke et al., Citation2020; van Corven et al., Citation2021).

In line with the previous paragraph about the importance of giving voice to the people, it is also important that older people be given a voice in the care process, participate in the empowerment process and be addressed as partners (De Witte & Van Regenmortel, Citation2019; Holroyd-Leduc et al., Citation2016; Janssen, Citation2010). Thus, empowerment measures can be valuable tools for social workers and organizations who work with older people, who have empowerment as an intended outcome or valuable mechanism, and who wish to better understand the extent to which this is achieved. The process of developing such measures should be preceded by exercises that give voice to the people concerned (i.e., the older persons) and give words to their perceptions and operationalization of what empowerment entails.

This study aims to operationalize psychological empowerment systematically from the perspective of older people. Subsequently, this study aims at contributing to the process of developing an empowerment measure for older people in the context of social work, by operationalizing the construct from the perspective of the target population.

Method

This study has a participatory, qualitative approach in which conversations between older people form the starting point. To operationalize psychological empowerment systematically, methodically and participatory, based on the perceptions of the target population, we applied a design based on the concept mapping method (Kane & Trochim, Citation2007; Trochim, Citation1989). We tailored that method to accommodate specific principles we assume in empowerment research and to align with target-specific conditions that apply to older people.

Concept mapping is a type of structured conceptualization groups can use to develop a conceptual framework (Kane & Trochim, Citation2007; Trochim, Citation1989). A set of statements that ideally represents the entire conceptual domain is generated in a brainstorm with the target group. Aligning with target-specific conditions related to older people means that in consultation with specialist geriatric social workers, we have determined that a solely linguistic approach to data collection is insufficient to achieve our goals of conducting inclusive research and involving a realistic representation of the target group. The original concept mapping method places great demands on participants’ mental and linguistic abilities, which may be inappropriate for some members of the target group, as not everyone is evenly articulate and skilled. From an ambition to allow for inclusive research, we instead used a design that can be considered a modified form of concept mapping. It includes alternative methods of querying participants that are supported by tools such as images or metaphors.

Setting

For this study, we choose to align with a preexisting activity called “the narrative at the table” that is offered weekly in three community centers in Nijmegen, the Netherlands. This activity focuses on facilitating a dialogue between older people about topics such as health, experiences and beliefs with the aim of having them learn from each other, get inspired and find recognition. The activity is hosted and moderated by a specialist geriatric social worker, along with a researcher (TN). Three sessions were organized, one in each of the community centers.

Participants

In total, 28 older persons participated in one of three sessions: Seven in the first session, 9 in the second and 10 in the third. All participants were at least 65 years old; the average age was 83 and the oldest participant was 94. Twenty-four of the participants (85.7%) were female.

The attendance of participants was voluntary and not based on a medical referral. In consultation with specialist geriatric social workers, we determined that dementia was a contraindication for this study because all participants could not contribute equally if people with dementia were included.

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of Tilburg University under reference number TSB_RP541.

Procedure

Brainstorm input and theoretical framework

The moderators introduced the activity with a short presentation about the concept of empowerment. They did not use the word “empowerment” but described the concept as “processes by which people can exert control over their lives and situations.” They then linked that idea to the aging process and related challenges. The theoretical introduction was supported by the use of images that represent empowerment (e.g., a hand holding a marionette was used to refer to efforts to balance and control events, a person juggling several objects was used to refer to efforts to deal with several challenges simultaneously). These images were discussed in the group. The moderators concluded the introduction by sharing a metaphorical story about a ship’s captain: the challenges he experiences whilst keeping his ship afloat and on course, how he collaborates with the sailors, and how he views his tasks as a captain.

By combining these strategies, we aimed to stimulate a narrative approach in which older persons share their stories and personal perspectives on what it means to exert control over their lives as they age and as such operationalize empowerment. A narrative approach seems explicitly suitable for this goal, as stories provide excellent insight into the insiders’ perspectives (Jansen et al., Citation2017; Robeyns, Citation2016). Over 25 years ago, Rappaport (Citation1995) linked a narrative approach to empowerment research and described the potential and value of this approach. Personal and collective narratives – which can be interdependent and reciprocal – can enhance the goals of empowerment by giving voice to both a person and the community to which they belong.

After these methodical introductions, the moderators began a group discussion based on an opening question: What is important to you in regard to being in control of your life and affairs?

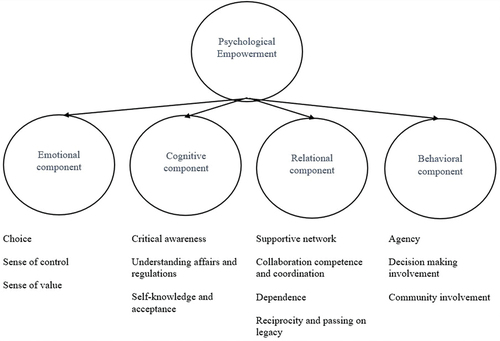

In this research, we chose to follow the theoretical framework put forward by Christens (Citation2012), who built on and expanded the three empowerment components in Zimmerman’s framework (Citation1995) – intrapersonal, interactional and behavioral – by adding the aforementioned fourth, relational component. Christens followed the work of Speer and Peterson (Citation2000) by renaming these components: the intrapersonal component became the emotional component, the interactional component became the cognitive component, and the behavioral component remained the same.

Although the worth of Zimmerman’s (Citation1995) framework has been proven repeatedly in research and measures, we chose to align with and experiment with adding “relational empowerment,” as we hope this helps to operationalize the construct in a way that does justice to this relational dimension and contributes to possibilities of distinguishing this relational side in measuring instruments.

Christens himself is cautious about the empirical clout of this new component structure, but he emphasizes that this proposed relational addition in the study of psychological empowerment can open new lines of inquiry that have theoretical, methodological and practical significance (Christens, Citation2012). Recent research suggests that this component structure can help to emphasize how psychological empowerment develops and is exercised within and through relationships (Cheryomukhin & Peterson, Citation2014; Langhout et al., Citation2013; Miguel et al., Citation2015; Rodrigues et al., Citation2018). We hope that this research contributes to a better understanding of how making relational empowerment explicit in operationalizations and frameworks for measuring instruments supports capturing relational aspects of empowerment in measuring activities.

To align with a theoretical framework, we derived the opening question from a simplified version of Van Regenmortel’s definition of empowerment (Citation2002). Subsequently, to link to theoretical conceptualizations of psychological empowerment (Christens, Citation2012; Zimmerman, Citation1995), we formulated follow-up questions that can be connected to this in terms of content. Those questions relate to every component of psychological empowerment: the emotional component (e.g. To what extent do you feel able to do what people ask of you?), the cognitive component (Which life lessons or insights help you manage in life?), the relational component (e.g. How do your loved ones help you stay on top of things?) and the behavioral component (e.g. What actions help you influence decision making?).

Brainstorm sessions

The moderators were actively involved in the brainstorm session: they questioned participants, asked follow-up questions, solicited responses from other participants, asked for clarifications, actively summarized and asked for confirmation. This is important because a brainstorm session needs to be managed; one cannot passively wait for participants to share their opinions (Kane & Trochim, Citation2007). In this process, the moderators regularly referred back to the metaphor they had used, and they reshowed supporting images. After a moderator summarized and developed a statement, it was presented to the group for confirmation and written on a large whiteboard so everyone could read it and respond.

Post-brainstorm sessions

At the end of the activity, it was discussed and evaluated in detail. Then, “the narrative at the table” activity was followed by a joint lunch. The researcher and social worker attended this lunch and used this opportunity to ask the participants to reflect on the activity. We chose to evaluate in a participatory manner through an open discussion and by participating in the discussion about the activity. No written data was collected here, as we did not want to burden the participants further.

To better understand the value of this activity as a way to give voice to older people and create an opportunity for them to have an empowering experience, the geriatric social worker and researcher (TN) extensively evaluated the process and outcomes of “the narrative at the table” as a participatory method and the mutual collaboration between research and social work practice as a strategy to improve both. After each session, the process and strategy were assessed and discussed. Follow-up questions were altered if the evaluation so indicated. The substantiation given for each image was also altered if the evaluation of a previous session so indicated.

Data analyses

The statements that derived from the sessions were not deduplicated, as we believe that even small semantic variations and nuances can have great meaning. Given that the opening questions and follow-up questions are distilled from the theoretical framework of Zimmerman (Citation1995) and Christens (Citation2012) and are thus based on the four components of empowerment, the data obtained from the group discussions was analyzed deductively (Doorewaard et al., Citation2019). This means that for all the statements derived from the sessions, we determined which component best fit the statement. The four-eyes principle was applied by having two researchers individually assign each statement to a category, after which the results were compared and deviations discussed (Doorewaard et al., Citation2019). ATLAS.ti (Citation2021) was used to code, label and organize statements. The schematic representation that arose from this exercise then formed the starting point to look for common threads per component, by means of a thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006).

Results

A total of 56 statements were collected throughout the sessions and each was assigned to one of the four components. The results of this exercise were schematically categorized. However, this assignment is complicated. Although the four components of psychological empowerment each emphasize a different aspect of the construct, the elements in the statements are so interrelated that they are difficult to isolate, and it is difficult to attribute statements to only one component. This corresponds with conclusions from the literature that the components of psychological empowerment are inalienable and reduction at the dimension level is not recommended (Akey et al., Citation2000; Speer & Peterson, Citation2000; Zimmerman & Rappaport, Citation1988). Nevertheless, when studying the statements, we tried to determine whether one component was more logically represented by the statement and assigned it accordingly.

The schematic representation then made it possible to look for common threads per component, by means of a thematic analysis. This forms the actual context specification of empowerment according to older people. In the search for these common threads, we were guided by the theoretical frameworks of psychological empowerment (Christens, Citation2012; Zimmerman, Citation1995). The naming of the elements within the four components of psychological empowerment was partly derived from or inspired by these theoretical frameworks. Other elements were named after context-specific literature related to older people. This leads to the integrated display as can be seen in . The most important results from this operationalization are finally presented descriptively.

Table 1. Emotional component of psychological empowerment.

Table 2. Behavioral component of psychological empowerment.

Table 3. Relational component of psychological empowerment.

Table 4. Cognitive component psychological of empowerment.

The cognitive component of psychological empowerment described by older people, demonstrates aspects that apply specifically to older people and relate to challenges that come to play in the process of aging. Several statements from older people relate to challenges they experience in maintaining an understanding of the world around them, including all kinds of financial or administrative affairs, regulations and obligations. Almost all the respondents recognized that they had challenges and wishes related to understanding their own finances, sharing authority and control over them, cooperating with family, and desiring agency. The complexity in this regard makes the necessity of self-knowledge explicit, as it forms the bridge between (not) understanding affairs and regulations and accepting possible shortcomings and as such contributes to one’s dependence on support, an aspect again positioned within the relational component of psychological empowerment.

Within the behavioral component of psychological empowerment, it is interesting to see that many reflections made by the participants relate to their ability to act (agency). The extent to which they perceived to be able to act seems strongly connected to the extent to which their environment allows them, or even supports them to act on one hand, but also the extent to which their cognitive understanding of their surroundings allow for them to act.

Discussion

This study shows how psychological empowerment is operationalized from the perspective of older people and how they load the construct with meaning. This can form the starting point for the construction of context-specific measuring instruments that center the perspective of the target population. This overview of how older people interpret psychological empowerment can also be used as a conversation tool, an opening to meaningful conversations between older people and others about mechanisms by which they can exert control over their affairs. In this way, the results of this research can truly contribute to the professional practice of social work and offer social workers a framework for discussion and a means to give substance to a complex construct like empowerment.

The inalienable components of psychological empowerment

As said before, the components of psychological empowerment are inalienable and aspects should be viewed holistically in order to really understand what they mean. By connecting aspects and contents from the different components, a real insight is gained into how empowerment manifests itself in the lives of older people. For example, the way in which a critical understanding (cognitive component) of how interdependence with one’s environment (relational component) leads to the decline of a sense of control (emotional component) and as such, interferes with one’s ability to act (behavioral component) illustrates how the different components interact within statements.

Context specifications for older people

Many of the themes found correspond to empowerment conceptualizations that already appear in the literature (e.g. Christens, Citation2012; Zimmerman, Citation1995). For example, choice and control’ take a central place in the operationalization by older people, but these concepts take on a different meaning and shape. The definitions or interpretations shifts from an absolute control to being able to have a say in how caregivers do their work. It now reflects on being allowed to steer and decide to the extent that is possible within one’s capabilities. Emphasis is placed on the extent to which people are given a voice and are listened to when making choices and exercising control, as such emphasizing the relationship between aspects from the emotional component of psychological empowerment such as choice and control, and aspects from the relational component of psychological empowerment, in this case collaboration competence and coordination and dependence, as exercising control and making choices for older people appear to be related to their ability to cooperate with the people who help them with this or on whom they sometimes even depend or experience dependence toward.

The fact that the thematic operationalization per component closely matches the theoretical frameworks of empowerment is unsurprising, given that the search for context-specific interpretation is based on theory when formulating opening questions and association questions for the data collection. Nevertheless, the specific context provides insight into important aspects for older people. An integrated view of the most important themes and elements per dimension is displayed below in .

A theme specific to older people is related to learning to let go and accept. Participants noted that aging implies a decrease in competence and ability to act, or suggests a need for support with tasks that people used to be able to perform independently. It also refers to emotional processes that come into play as people age and their capabilities decline. Emphasizing this point could increase the risk of ageism, but ignoring it does not acknowledge the grief and pain the participants report experiencing during the aging process. The decline and loss that older people experience and the effects this has on them have been extensively described in the literature (de São José et al., Citation2016; Deeg, Citation2010; Nicholson et al., Citation2012).

The importance of reciprocity

Another notable theme relates to reciprocity between older persons and people in their environment and addresses the strengthening potential that arises when older people can share and pass on insights and experiences to younger generations: passing on a legacy. Doing this contributes to a sense of usefulness and value, and it can form a natural counterargument against ageism, i.e. the notion that growing older is intertwined with vulnerability, loss of capabilities and other negative connotations (De Witte & Van Regenmortel, Citation2023). This sense of value and usefulness also seems to be a specific operationalization of how older people interpret empowerment. This aligns with earlier research into perspectives on empowerment in which “retaining a sense of worth” and “having a sense of usefulness and being needed” were core features of an empowerment conceptualization for people with dementia (van Corven et al., Citation2021). The literature supports the importance of reciprocity for older people, as empowerment may contribute to reciprocity in relationships (Huizenga et al., Citation2022; Vernooij-Dassen et al., Citation2011; Westerhof et al., Citation2014). This can negate negative images that come into play when discussing older people and their dependence on their environment, a factor that was regularly mentioned by the participants and supported by the literature (de São José et al., Citation2016). In line with this, when combining insights from the cognitive and relational components, we emphasized the need to come to a critical understanding of how older people can maintain an overview of their situation, with critical awareness of the interdependence with their environment being central. Family members often play an important role in organizing such an overview. Resigning themselves to such dependence seems to contribute to a sense of control for older people.

The empowering potential of modified concept mapping

In line with the principles of empowerment evaluation, it would be a good aim to conduct research with empowering potential. In other words, contributing to and participating in this study should open doors to empowering experiences. To create opportunities in this regard, we found it necessary to adjust methodological standards and conditions. In the data collection process, we emphasized meaningful conversation between the participants. Their process and dialogue were prioritized and the distillation of data was secondary.

Adding relational empowerment as a fourth component

The literature is clear about the importance of interpersonal relationships and social embedding in regard to empowerment. However, it is unclear how this relational dimension can best be made explicit in operationalizations of empowerment. Some researchers assume that the relational aspect is so incorporated and intertwined in the other dimensions that sufficient value is attached to it (Boomkens, Citation2020; Zimmerman, Citation1995). Others argue for the addition of relational empowerment as a fourth component, precisely to emphasize how power is developed and exercised through relations (Christens, Citation2012) and how a sense of connection is needed to become and stay empowered (Christens, Citation2019).

The addition of a fourth component seems to create possibilities to distinguish the relational aspect from more cognitive or emotional aspects in theory and item formation, which is part of what this study is about. It can provide a helpful tool when constructing scales. On the other hand, operationalizing the intrapersonal, the interpersonal and the behavioral components with items that account for connectiveness and relational aspects might do sufficient justice to the value of the relational dimension of empowerment, aligning with the assumption that this relational aspect is incorporated and intertwined in the three components of psychological empowerment (Zimmerman, Citation1990). Nonetheless, we found adding relational empowerment to be a helpful tool in the process of operationalizing psychological empowerment and emphasizing important relational aspects from perspectives of older people.

Strengths and limitations

The open-ended character of empowerment (i.e. its ability to be interpreted differently by individuals or groups) makes it complicated to develop universal instruments. Even when operationalized together with the target population, the results cannot necessarily be generalized for other groups of people with comparable characteristics because other older people may define and operationalize empowerment differently. Nevertheless, the results of this study seem to give a good indication of the central themes and challenges that older people experience within the framework of empowerment and in the face of aging. As such, these results can form a starting point for developing context-specific measures that align with the perceptions of the target population.

One limitation of this study is related to the challenge of assigning statements to components. The interdependence and inalienability of the components creates a risk of arbitrariness. Our awareness that different researchers might make other choices in the assignment led us to apply the four-eyes principle to the assignment. One might also ask how important the exact allocation is since the ultimate value is in the whole. Minor variances in allocation do not detract from the value of the final operationalization. In relation to this, the framework we describe here – with four components, each symbolizing a different dimension of empowerment – suggests that empowerment can be unraveled almost mathematically, in smaller logical units that form a coherent whole. This is at odds with the notion that empowerment is a complex, multilevel and multidimensional construct in which different principles constantly interact, interdepend and are intertwined. Such an unraveling is helpful for measuring, but it is important to emphasize that empowerment should be viewed as a holistic, layered and cohesive construct.

The data collection process was preceded by an introduction to the concept of “empowerment.” Critics may argue that this gave some degree of direction to the participants’ thinking process and thus influenced the data collection. However, our choice to offer a theoretical demarcation is legitimized by the knowledge that empowerment could become an all-purpose word to which everyone assigns a different meaning and thus lose its substantive value (Noordink et al., Citation2019, Citation2023; Van Regenmortel, Citation2002).

Another limitation concerns the fact that this study did not systematically measure the extent to which the method was empowering for participants. We determined that an extensive evaluation with participants would be too burdensome for them, given the limited time we had together. The open nature of the activity that led to different participants every week also complicated possibilities for entering into a sustainable collaboration with the participants. This made it difficult to evaluate the activity or to involve the participants in the interpretation of the data and the valorization of the results.

Another tension in data collection is related to the accessibility of research and thus the representativeness of the target group. Although we created interventions to increase accessibility (e.g. by adding images and metaphors), the method remains a cognitive, verbal exercise. This may not be feasible for everyone. For example, when the group was asked whether the formulated statement did justice to the discussion, it was common for one or two participants to zone out. It is unclear whether the latter exercise, in which the participants were asked to indicate individually to what extent they agreed with the statements, sufficiently compensated for this.

A final limitation is found in the methodological adjustments that were made to the original method of concept mapping. The adjustments were based on the desire to connect with the context-specific characteristics of the target group and focus on the empowering potential of research. Specifically, this means that we skipped the section in the regular concept mapping process in which respondents are asked to rank the statements in order of importance. This could have led to a prioritization of the collected results and to gradation of the outcomes. Since our goal was not to prioritize the content of the operationalization but simply to map the context-specific operationalization of the construct, we asked the respondents to indicate the extent to which they identified with the statements in order to contribute to the representativeness of the statements.

Also, in the regular application of concept mapping, researchers use complex algorithms and computing techniques in the mapping process and in the process of assigning statements to a cluster (e.g. nonmetric multidimensional scaling techniques and hierarchical cluster analyses; Trochim, Citation1989). We did not use these analytic processes. Instead, we chose to use a deductive approach in which we let the theoretical framework of empowerment form the mold. Furthermore, we believe that the efforts required for our older participants to arrive at data that could be analyzed using these mathematical techniques are too burdensome for the target group and would not necessarily contribute to the quality of the results. Instead, we used a thematic analytic approach to identify the context-specific operationalizations of psychological empowerment. We believe that the importance of connecting to context-specific characteristics of the target population and focusing on the empowering potential of research legitimizes the necessity to make these methodological adjustments.

Conclusion

The results of this research offer valuable information for the professional practice of social work. They can help social workers better understand core elements, questions and challenges older people face in the process of acquiring, maintaining and exerting control over their affairs and situations as they age. Social workers can use this information to adjust their services, interventions and strategies accordingly. Even more, this overview offers social workers a framework for discussion, a conversation tool, and a means to give substance to a complex construct like empowerment in dialogue with people involved.

For research, the results provide insight into research methodology that can combine data collection with strategies that allow participants to have empowering experiences. It shows how adjustments to existing research methods can be made, how they can be legitimized and on what basis context-specific properties of such adjustments can be proposed. Finally, the results provide information about the advantages and disadvantages of such adjustments and how they can be balanced.

For the older people, the process seemed more important than the results. A closer look at the process suggests that participants had positive, empowering experiences while contributing to the research process. During the debriefing after the sessions, participants repeatedly indicated that they experienced recognition and acknowledgment when discussing experiences and insights associated with exerting control over their affairs. The researchers and social worker were asked to revisit this in the future, and some participants indicated they would appreciate being kept informed about the results of this study.

AOM to preprint server research square

Noordink, T., Verharen, L., Schalk, R., & Van Regenmortel, T. (2023). An innovative concept mapping of the empowerment construct in dialogue with older people. Research Square. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3162821/v1.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to express their gratitude to Rob Aalders, social worker, for hosting the group sessions with the participants, to Sterker Sociaal Werk for their contribution to this research, to Erin Stallings for language editing and to Arjan Doolaar for reference assistance and APA support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akey, T. M., Marquis, J. G., & Ross, M. E. (2000). Validation of scores on the psychological empowerment scale: A measure of empowerment for parents of children with a disability. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 60(3), 419–438. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131640021970637

- ATLAS.ti. (2021). (Version 9.1) [Computer software]. ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development.

- Boomkens, C. (2020). Supporting vulnerable girls in shaping their lives: Towards a substantiated method for girls work. Ipskamp Printing.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Chavis, D. M., & Wandersman, A. (1986). Roles for research and the researcher in neighborhood development. In R. B. Taylor (Ed.), Urban neighborhoods: Research and policy (pp. 215–249). Praeger.

- Cheryomukhin, A., & Peterson, N. A. (2014). Measuring relational and intrapersonal empowerment: Testing instrument validity in a former Soviet country with a secular Muslim culture. American Journal of Community Psychology, 53(3–4), 382–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-014-9649-z

- Christens, B. D. (2012). Toward relational empowerment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50(1–2), 114–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-011-9483-5

- Christens, B. D. (2019). Community power and empowerment. Oxford Academic.

- Clarke, C. L., Wilcockson, J., Watson, J., Wilkinson, H., Keyes, S., Kinnaird, L., & Williamson, T. (2020). Relational care and co-operative endeavour – Reshaping dementia care through participatory secondary data analysis. Dementia (London, England), 19(4), 1151–1172. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301218795353

- Cochran, M. (1992). Parent empowerment: Developing a conceptual framework. Family Science Review, 5(1), 3–21.

- Deeg, D. J. H. (2010). Empowerment (LASA report 2009). Vrije Universiteit; Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam; VU medisch centrum. https://lasa-vu.nl/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/vws-rapport-2009-empowerment.pdf

- de Kreek, M. (2014). Empowerment from a narrative perspective: Learning from local memory websites.

- de São José, J., Barros, R., Samitca, S., & Teixeira, A. (2016). Older persons’ experiences and perspectives of receiving social care: A systematic review of the qualitative literature. Health & Social Care in the Community, 24(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12186

- De Witte, J., & Van Regenmortel, T. (2019). Silver empowerment: Loneliness and social isolation among elderly: An empowerment perspective. HIVA-KU Leuven. https://lirias.kuleuven.be/retrieve/548228

- De Witte, J., & Van Regenmortel, T. (Eds.). (2023). Silver empowerment: Fostering strengths and connections for an age-friendly society. Leuven University Press. https://doi.org/10.11116/9789461665072

- Doorewaard, H., Kil, A., & van de Ven, A. (2019). Praktijkgericht kwalitatief onderzoek: Een praktische handleiding [Practice-based qualitative research: A practical manual] (2nd ed.). Boom.

- Fetterman, D. M. (2005). Empowerment evaluation principles. Assessing levels of commitment. In D. M. Fetterman & A. Wandersman (Eds.), Empowerment evaluation in practice (pp. 42–72). Guilford Press.

- Fisher, B. J., & Gosselink, C. A. (2008). Enhancing the efficacy and empowerment of older adults through group formation. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 51(1–2), 2–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634370801967513

- Florin, P., & Wandersman, A. (1990). An introduction to citizen participation, voluntary organizations, and community development: Insights for empowerment through research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 18(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00922688

- Freire, P. (1982). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum.

- Holroyd-Leduc, J., Resin, J., Ashley, L., Barwich, D., Elliott, J., Huras, P., Légaré, F., Mahoney, M., Maybee, A., McNeil, H., Pullman, D., Sawatzky, R., Stolee, P., & Muscedere, J. (2016). Giving voice to older adults living with frailty and their family caregivers: Engagement of older adults living with frailty in research, health care decision making, and in health policy. Research Involvement and Engagement, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-016-0038-7

- Huizenga, J., Scheffelaar, A., Fruijtier, A., Wilken, J. P., Bleijenberg, N., & Van Regenmortel, T. (2022). Everyday experiences of people living with MCI or dementia: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10828. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710828

- Hupkens, S., Machielse, A., Goumans, M., & Derkx, P. (2016). Meaning in life of older persons: An integrative literature review. Nursing Ethics, 25(8), 973–991. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733016680122

- International Federation of Social Work. (2014). Global definition of social work. https://www.ifsw.org/what-is-social-work/global-definition-of-social-work/

- Jansen, E., Pijpers, R., & De Kam, G. (2017). Expanding capabilities in integrated service areas (ISAs) as communities of care: A study of Dutch older adults’ narratives on the life they have reason to value. Journal of Human Development & Capabilities, 19(2), 232–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2017.1411895

- Janssen, B. (2010). Professionele ondersteuning vanuit het perspectief van kwetsbare ouderen [Professional support from the perspective of vulnerable elderly people. In T. Van Regenmortel (Ed.), Ervaringskennis als kracht. Empowerment en participatie van kwetsbare burgers [knowledge-by-experience as a strength. Empowerment and participation of vulnerable citizens] (pp. 135–150). Uitgeverij SWP.

- Kane, M., & Trochim, W. M. K. (2007). Concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Sage Publications.

- Langhout, R. D., Collins, C., & Ellison, E. R. (2013). Examining relational empowerment for elementary school students in a yPAR program. American Journal of Community Psychology, 53(3–4), 369–381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-013-9617-z

- Lloyd, P. (1991). The empowerment of elderly people. Journal of Aging Studies, 5(2), 125–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/0890-4065(91)90001-9

- Maertens, M., & Desmet, B. (2015). Report: Empowerment vision and theoretical foundation. Centrum Empowerment voor Ouderenzorg.

- Miguel, M. C., Ornelas, J. H., & Maroco, J. P. (2015). Defining psychological empowerment construct: Analysis of three empowerment scales. Journal of Community Psychology, 43(7), 900–919. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21721

- Ng, B., & Ho, G. (2020). Self-determination theory and healthy aging: Comparative contexts on physical and mental well-being. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-6968-5

- Nicholson, C., Meyer, J., Flatley, M., Holman, C., & Lowton, K. (2012). Living on the margin: Understanding the experience of living and dying with frailty in old age. Social Science & Medicine, 75(8), 1426–1432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.06.011

- Noordink, T., Verharen, L., Schalk, R., Van Eck, M., & Van Regenmortel, T. (2021). Measuring instruments for empowerment in social work: A scoping review. The British Journal of Social Work, 51(4), 1482–1508. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcab054

- Noordink, T., Verharen, L., Schalk, R., & Van Regenmortel, T. (2019). De totstandkoming van meetinstrumenten van empowerment onder de loep: Instrumentontwikkeling volgens de kwaliteitsstandaarden, een kritische beschouwing [Quality standards for the development of measuring instruments aimed at empowerment: A critical consideration]. Journal of Social Intervention, 28(4), 24–47. https://doi.org/10.18352/jsi.584

- Noordink, T., Verharen, L., Schalk, R., & Van Regenmortel, T. (2023). The complexity of constructing empowerment measuring instruments: A Delphi study. European Journal of Social Work, 26(6), 1123–1136. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2023.2168627

- Nyende, A., Ellis-Hill, C., & Mantzoukas, S. (2023). A sense of control and wellbeing in older people living with frailty: A scoping review. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 66(8), 1043–1072. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2023.2206438

- Rappaport, J. (1984). Studies in empowerment: Introduction to the issue. Prevention in Human Services, 3(2–3), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1300/J293v03n02_02

- Rappaport, J. (1987). Terms of empowerment/exemplars of prevention: Toward a theory for community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology, 15(2), 121–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00919275

- Rappaport, J. (1995). Empowerment meets narrative: Listening to stories and creating settings. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 795–807. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02506992

- Riger, S. (1993). What’s wrong with empowerment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 21(3), 279–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00941504

- Robeyns, I. (2016). Conceptualizing well-being for autistic persons. Journal of Medical Ethics, 42(6), 383–390. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2016-103508

- Rodrigues, M., Menezes, I., & Ferreira, P. D. (2018). Validating the formative nature of psychological empowerment construct: Testing cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and relational empowerment components. Journal of Community Psychology, 46(1), 58–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21916

- Rogers, E. S., Chamberlin, J., Ellison, M. L., & Crean, T. (1997). A consumer-constructed scale to measure empowerment among users of mental health services. Psychiatric Services, 48(8), 1042–1047. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.48.8.1042

- Speer, P. W., & Peterson, N. A. (2000). Psychometric properties of an empowerment scale: Testing cognitive, emotional, and behavioral domains. Social Work Research, 24(2), 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/24.2.109

- Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). An empirical test of a comprehensive model of intrapersonal empowerment in the workplace. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 601–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02506984

- Trochim, W. M. (1989). An introduction to concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Evaluation and Program Planning, 12(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/0149-7189(89)90016-5

- van Corven, C. T. M., Bielderman, A., Wijnen, M., Leontjevas, R., Lucassen, P. L. B. J., Graff, M. J. L., & Gerritsen, D. L. (2021). Defining empowerment for older people living with dementia from multiple perspectives: A qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 114, 103823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103823

- Van Gorp, B. (2013). Van “over en oud” tot “het zilveren goud”: Beeldvorming en communicatie over het ouder worden [From “gone and old” to “the silver gold”: Imaging and communication about aging]. Koning Boudewijnstichting.

- Van Regenmortel, T. (2002). Empowerment en maatzorg: Een krachtgerichte psychologische kijk op armoede [Empowerment and tailored care: A strength-oriented psychological view of poverty]. Acco.

- Van Regenmortel, T. (2011). Lexicon van empowerment: Marie Kamphuis lezing 2011 [Lexicon of empowerment: Marie Kamphuis lecture 2011]. Marie Kamphuis Stichting. https://www.amsterdamsnetwerkervaringskennis.nl/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Regenmortel-lexicon-empowerment.pdf

- Van Regenmortel, T., Steenssens, K., & Steens, R. (2016). Empowerment research: A critical friend for social work practitioners. Journal of Social Intervention: Theory and Practice, 25(3), 4–23. https://doi.org/10.18352/jsi.493

- Vernooij-Dassen, M., Leatherman, S., & Rikkert, M. O. (2011). Quality of care in frail older people: The fragile balance between receiving and giving. British Medical Journal, 342(mar25 2), d403–d403. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d403

- Wandersman, A., Snell-Johns, J., Lentz, B., Fetterman, D., Keener, D., Livet, M., Imm, P., & Flashpoler, P. (2005). The principles of empowerment evaluation. In D. M. Fetterman & A. Wandersman (Eds.), Empowerment evaluation in practice (pp. 27–41). Guilford Press.

- Westerhof, G. J., van Vuuren, M., Brummans, B. H., & Custers, A. F. (2014). A Buberian approach to the co-construction of relationships between professional caregivers and residents in nursing homes. The Gerontologist, 54(3), 354–362. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnt064

- Zimmerman, M. A. (1990). Taking aim on empowerment research: On the distinction between individual and psychological conceptions. American Journal of Community Psychology, 18(1), 169–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00922695

- Zimmerman, M. A. (1995). Psychological empowerment: Issues and illustrations. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 581–599. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02506983

- Zimmerman, M. A. (2000). Empowerment theory: Psychological, organizational and community levels of analysis. In J. Rappaport & E. Seidman (Eds.), Handbook of community psychology (pp. 43–63). Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-4193-6_2

- Zimmerman, M. A., & Rappaport, J. (1988). Citizen participation, perceived control, and psychological empowerment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 16(5), 725–750. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00930023