ABSTRACT

Hugs are a pervasive practice characterizing human sociality. They involve the persons engaged in hugging as well as other persons who might witness it for various purposes. This article examines the social organization of hugging in family photography sessions. This organization integrates instructions to hug, orchestrated by photographers and sometimes by third parties, and their responses; it also relies on constitutive details of local contexts as well as global projects of the photographing activity. By concentrating on the organization of hugs in photography sessions, this study highlights the movement trajectories of hugging parties and their projectability and visibility. Relying on their professional vision, photographers identify, arrange, and shoot photographable haptic compositions. The ways in which hugs are produced index different familial relationships among hugging parties, shedding light on issues such as agency, participation and entitlement.

Introduction

Hugs are a pervasive haptic practice in everyday life, observable in the opening phases of encounters and in farewells but also in the midst of other activities. Often spontaneously emerging among familiar and intimate participants, hugs can also be instructed or requested by others, like by parents to children or teachers to students reconciling after a fight. In all cases, hugging is a social interactional practice, relying on a fine-tuned coordination between the hugging parties.

This article contributes to recent studies of haptic sociality in human interaction by examining the interactional anatomy of hugging. We focus on a context of action in which hugs are particularly observable for analysts and witnessed by other participants, analyzing hugs instructed by a third party: a photographer shooting portraits of families and couples. Hugs can emerge serendipitously between family members and can also be instructed for a family photo. This enables us to cast light on the organization of action in social interaction at several levels: on instructions, on hugging as an embodied haptic practice, and on its visible and public accountability.

A threefold focus: instructions, haptic configurations, and their visible accountability

This article has a threefold interest. First, it focuses on instructions as situated actions and deals with how they are formatted and how they are followed, concentrating in particular on instructing embodied actions and addressing issues in the interactional organization of instructing and instructed actions. Second, it targets hugging as a particular embodied action involving physical contact and touch, addressing issues in interpersonal sensoriality. Third, it discusses the visible accountability of embodied actions, focusing on an activity where visibility is centrally at stake: taking photographs of families.

In this way, we explore the sociality of hugs in three distinct but closely interrelated ways: a) hugging achieves sociality by haptically engaging two or more persons in a course of action; b) hugging is not only a private or intimate form of conduct but is socially organized and coordinated, for example, by being instructed and corrected by others; and c) hugging is witnessable and scrutinizable, seeable by others as indexing specific forms of interpersonal relations.

Interactional organization of instructions

Getting someone to do something has attracted attention in disciplines such as speech act theory and conversation analysis. Whereas the former highlights the communicative intentions of persons, examining the syntactic forms and the contextual details such as role, age, familiarity, difficulty of tasks in question, etc. (Ervin-Tripp, Citation1976; Vine, Citation2009), the latter focuses on how people reach intersubjective understandings in and through interaction (Deppermann, Citation2015; Mondada, Citation2014). The present article adopts the latter perspective and attends to how hugs among family members in professional photography sessions are produced and treated especially in relation to the photographer’s vision and instructions.

Instruction sequences within the perspective of ethnomethodology and conversation analysis involve instructing and instructed actions as paired actions. Instructing actions can be designed with imperatives, future subjunctives, noun phrases in the form of deictic expressions, and so on and are often accompanied by embodied practices like gestures and bodily movements (Deppermann, Citation2018). Instructed actions are usually done in the form of embodied compliances, sometimes involving confirmation tokens. These complying instructed actions could be rather swift, particularly in the cases of practical and urgent tasks (Mondada, Citation2014; Tekin, Citation2017) as well as when they are projectable (Deppermann & Schmidt, Citation2021; Mondada, Citation2021), but sometimes their implementation may require some time, especially in pedagogical activities such as calligraphy lessons (Nishizaka, Citation2020) or crochet classes (Lindwall & Ekström, Citation2012). Instructions might also be disaligned, resulting in alternative sequential trajectories in which various sorts of adjustments and modifications could be observed (Goodwin, Citation2006).

Hugging for the photograph as an instructed action exhibits the interpersonal relationship of the family members. Photographed hugs achieve the accountability and visibility of the family members as belonging to the family.

Hugs and haptic sociality

The importance of touch for interpersonal relationships has been recognized by an abundant literature. Touch achieves the intimacy and affection of the persons touching each other (Cekaite & Kvist, Citation2017), although it can also be used for controlling the body of others, typically of children (Cekaite, Citation2016). It can also respond to normative expectations, related to rights or prohibitions to touch (Mondada, Bänninger, et al., Citation2020). Touch has been specifically studied as a form of haptic sociality (Goodwin, Citation2017) in the details of its interactional organization (Cekaite & Mondada, Citation2020; Meyer et al., Citation2017).

Hugging, as a particular and frequent form of touching, is part of the repertoire of practices constituting haptic sociality. As shown by Goodwin (Citation2017, Citation2020) and Goodwin and Cekaite (Citation2018), studying family life, hugs not only convey affection in supportive interchanges (together with holding hands, embracing, or kissing) but also characterize asymmetric orientations (such as when one parent requests the child to give a hug). Consequently, hugs can be organized in reciprocal ways but also unilaterally requested; they can be responsively complied and accepted but also resisted and refused, making them an important locus of socialization into family control and affection. Like kisses (see Mondada, Monteiro et al., Citation2020), hugs can be exchanged at any moment in social interaction, contrary to other forms of touch that are rather specialized in the openings (such as handshakes). Hugs also suppose the progressive creation of a “haptic formation” that can be maintained for some time, engaging in more proximal or distal touch, thus affording variations in the intensity, intimacy, and formality of the haptic moments, which have to be locally negotiated by the participants. The Covid-19 pandemic was interesting in this respect, generating a renegotiation of meanings, expectancies, and normativities of hugging (Mondada, Bänninger, et al., Citation2020). Variations in hugging are acknowledged in relation to emotions, including their neuropsychological dimensions and psychosomatic benefits (Forsell & Åström, Citation2012), gender, age, and culture (Sorokowska et al., Citation2021). In particular, culture may play a vital role in the variations of hugs—impacting their duration, contact, intensity, and so on—through which hugging parties exhibit specific relationships. Yet, the connections between culture and different ways of hugging remain relatively underexamined in the literature. Rather than directly linking hugs and culture, this article focuses on specific situated activities, which shape ways of hugging (see below the distinction between ordinary hugs and hugs done for the camera). It might be interesting to note that the hugging practices considered in our article, concerning families of various cultural background (expats from European countries and Swiss German) present very similar trajectories, which might be related to the social activity they are embedded in. They present also some similarities with data from families in the United States and Sweden (Goodwin & Cekaite, Citation2018) but initiated in different ways and performed within different types of activities. In this sense, this article rather focuses on the sociality of hugs, as it is revealed by the sequential organization of hugging, including the embodied trajectories that build their projectability and amount to their intersubjective completions as well as their situated interpretations by the co-present participants.

The sociality of hugs is achieved both in the ways the huggers engage in hugging, in aligned or disaligned ways, and in the ways others (other ratified co-participants but also bystanders) glimpse, stare, or witness them. Hugs are publicly visible for others who can see and understand what the hugging parties are doing, or about to do, even when they are not acquainted with them. Interested in the way people present the public intelligibility of their actions, Goffman refers to “body idioms” (Goffman, Citation1963) and “body glosses” (Goffman, Citation1971) as the ways in which persons make their actions not only intelligible but also normal and predictable for unacquainted others, both establishing and securing the social order of public life.

Within ethnomethodology and conversation analysis, the intelligibility of action has been treated in terms of accountability, which refers to the way an action is not only understandable and interpretable but also normatively acceptable (Garfinkel, Citation1967; Robinson, Citation2016; Schegloff, Citation1997). The accountability of embodied and haptic practices has been addressed by multimodal analyses (Mondada, Bänninger, et al., Citation2020; Mondada et al., Citation2021; Mondada & Tekin, Citation2020). It has also been highlighted more recently by debates about the recognizability and ascribability of action (Deppermann & Haugh, Citation2022; Levinson, Citation2012; Svensson & Tekin, Citation2023): Action is not only formatted by the individuals producing it but also understood, recognized, interpreted, and ascribed by the other parties. In this respect, our analysis of hugging discusses both how the involved participants coordinate their hugging and how co-participants witnessing understand what they are doing, ascribing meaning and intentions to them. While hugging might be visibly interpretable, for instance, as affective, intimate, reticent, or formal, by strangers witnessing it, the interpretability of hugging and touching practices might sometimes also be challenging for both the participants and the analysts. In this context, the visibility of embodied actions from the perspective of the participants remains understudied and often taken for granted by the researchers. This article aims at contributing to this aspect by focusing on a situation in which co-participants engage in haptic sociality and orient to its relevance both for the type of relationship they are in and for what they manifest for others, locally recognizing and ascribing certain actions rather than others. Photography sessions, and especially sessions aiming at producing family portraits, are situations in which the visibility of social, informal, and intimate touching practices is particularly at stake. Visibility is crucial both for the “professional vision” (C. Goodwin, Citation1994) of the photographer whose task is to observe and capture the spirit of the family in their portraits and for the photographed participants actively contributing to the image of their cohesive and affectionate family. As we shall see below, hugs feature in a central way in the constitution of this image. Thus, this article explores the visibility of hugs in this particular context of activity that constitutes a “perspicuous setting” (Garfinkel, Citation2002) for revealing these two faces of the haptic sociality.

Photographing the social life of families

Family photography has been identified as the site of the visual production of affective and intimate relationships together with morality, respectability, and social status for different uses, from domestic ones (Rose, Citation2003) to bureaucratic ones (Rizzo, Citation2013), within European and non-European cultures. Family photos rely on the relations between visual appearances and affects, such as ostensive happiness and joy (Rose, Citation2010) as well as social distinction (Bourdieu, Citation1990). Even when portraited in informal attitudes, the social organization of the family is made visible: Goffman confirms that pictures of families “nicely serve as a symbolization of the family’s social structure” (Goffman, Citation1979, p. 37), with more marked gendered associations between mother–daughter and father–son in advertisements. Even within attempts to creatively innovate the family style of photographs, the reference to and use of remarkably stable conventions are perpetuated, reproducing dominant ideological normative visions of the family as stable, happy, and cohesive (Hirsch, Citation1999; Spence & Holland, Citation2000).

History and sociology of photography have considered the photographers, either professionals or amateurs, and the consequences of technical developments for the accessibility of photography to socially diverse families, and they have reconstructed the circumstances of photograph taking (e.g., portraits in the studio, photos of people on holiday pictured by street photographers, or family photos taken by fathers, etc.) and portrait circulations and displays (Rose, Citation2003, Citation2010). However, the very practices for obtaining these photographs are less studied. Despite the identification of posed versus arranged or directed versus caught photographs, reconstructed on the basis of the photographs themselves or their archives, and despite references to posing, arranging, and directing, often on the basis of testimonies of or manuals for photographers, the in vivo practices of taking photographs are rarely studied. This article elaborates on a few video studies of these practices describing how the photographable is actually assembled (Tekin, Citation2017), how the poses are instructed and how the bodies are arranged (Mondada & Tekin, Citation2020), and how haptic moments are orchestrated (Mondada, Monteiro, et al., Citation2020). More generally, it refers to the project of studying photographing in action by using videos of naturally occurring photography sessions, in a way that is akin to the studies of situated video practices (Broth et al., Citation2014; Mondada et al., Citation2022).

Data and Methods

This article is based on a corpus of a series of outdoor family photography sessions (about 4 hours) involving a professional photographer shooting the portraits of various families from different cultural and linguistic backgrounds. These sessions were video recorded without constraining the ongoing photographing activities. In the data examined here, participants speak different languages, including English, German, Swiss German, and French. They were filmed with one to three cameras. All participants were informed about the study, agreed to take part in it and to be filmed, the videos to be used for research in the form of transcripts, and signed a consent form. However, they did not agree for the data to be shared publicly (i.e., to put the data on an open research data repository) for privacy reasons. There was not any analysis plan or study preregistration.

The analysis focuses on how hugs emerge in the course of an ongoing activity, either spontaneously or in a directed way, and how they either become a photographable or are instructed to be formatted as such. On the one hand, this enables us to analyze how the hugging haptic configuration is progressively and collectively established by the participants, by those who hug but also those who monitor and photograph these hugs. This configuration supposes a coordinated approach of the huggers. On the other hand, this allows us to demonstrate how the visibility of the hugging trajectories is established and publicly witnessed, recognized, and ascribed: Hugs are treated as publicly visible displays of affection and intimacy but are also treated as a photographable (see Tekin, Citation2017). A photographable is an event or an action, which either attracts the attention of the photographers (when hugs are self-initiated) or is orchestrated and treated as relevant and meaningful by them for the family (and for the family archive). As a photographable, the hug is not only a haptic configuration but also a haptic composition. Orienting to the camera/photographer, the hugging participants not only organize their hugging arrangements but position themselves toward the camera, designing and adjusting their bodies to the perspective of the photographers. As we see below, this shapes the haptic composition as a side-by-side or one-behind-another (see Tekin, Citation2017) rather than a face-to-face hugging. Thus, this article contributes to studies of haptic sociality by showing in detail how hugs are sequentially organized, embedded in courses of action, and integrated in global projects (like the activity of taking photographs) and how their visible accountability is achieved, publicly performed to be seen by others, and shot by the photographer.

The ensuing analyses first discuss the two ways in which hugs emerge: self-initiated by the hugging participants and instructed by the photographer. We then show that hugs can be made relevant with generic instructions in which the mere mention of togetherness is responded to by the participants by hugging. Moreover, generic instructions involving some “withs” (Goffman, Citation1971, p. 19) can be followed by instructions to hug. Instructions to hug can be formulated explicitly by using the verb “to hug,” which introduces further issues, such as whom is targeted by the instruction, how the instruction is eventually achieved, and who else might produce instructions beside the photographers. The analyses reveal multiple constraints and contingencies at play in constituting a hugging configuration and in achieving a photographable hugging composition.

Self-initiated versus instructed hugs

The photography sessions take place in an outdoor environment with an open terrain, in which the participants gather together and engage in conversation and other playful activities. As in their daily social life, they hug spontaneously at various occasions (Goodwin, Citation2017), not orienting to the camera but as part of their affectionate and intimate relationships. The photographer might see them hugging and promptly seize these scenes: these are occasioned photographs, capturing moments of intimacy. Moreover, the photographer might also orchestrate these moments, by instructing the participants to hug and arranging them in a choreographed pose. In this section, we show how these two ways in which hugs are produced, seen, and photographed emerge in situ.

In the following extract, the participants come out from a previous series of shots. We join the action as everybody relaxes after the photographer has shown the photographs she just took at her camera:

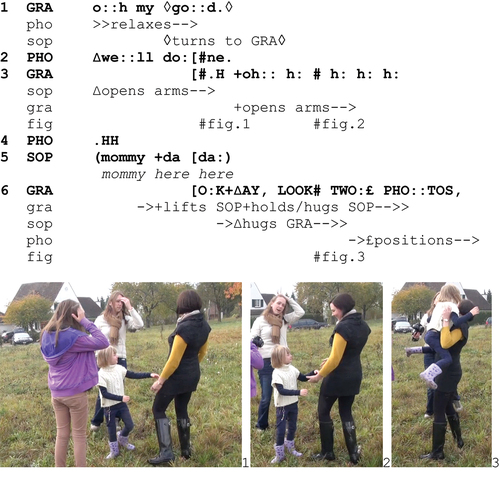

Extract 1a (PHO_BS_301016_1220)

While Grace (1) and the photographer (2) comment on the previous shots, Sophie opens her arms toward her mother as an invitation to hug (1, Figure 1), and Grace responds with a reciprocal gesture (2, Figure 2). As Sophie addresses her in an affectionate way (5), Grace lifts her and they hug one another (Figure 3). This manifestation of affection is not treated by the photographer as a photographable: She gazes at Grace but maintains a relaxed posture and does not move her camera. The hug—initiated by Sophie, promptly reciprocated by her mother, both engaging in a mutual body contact—is treated as a moment of intimacy.

Although the photographer does not orient to the hug spontaneously emerged between daughter and mother as a possible target, soon after they hug, she changes her posture from a relaxed to a tensed one:

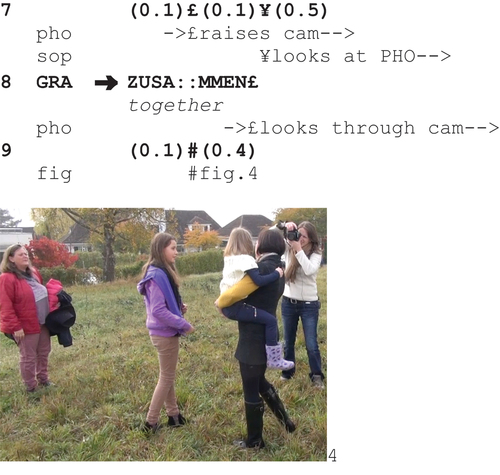

Extract 1b

Having repositioned and stabilized her body by firmly standing on her two feet, the photographer raises her camera (7), bringing it at the level of her eyes, ready to shoot. At this point, she exhibits her identification of the hug as a photographable and projects to take a photo. Sophie directs her gaze toward her (7). Yet, Grace gazes at Heidi, her sister-in-law (Figure 4), while proposing another shot of the two families (6, 8). This is further expanded in the beginning of a list of people concerned (10), which is responded to by Heidi informing that Fredi, her husband, has walked away to bring extra shoes for the grandmother (12). While Sophie aligns with the proposed photograph, Grace positions herself within another participation framework, with Heidi, orienting toward the next activity. The photographer lowers the camera (10) without having taken any photo.

Hugs can be treated by the participants as a moment of intimacy, neither staged for the camera nor targeted by it (Extract 1a). However, these orientations might dynamically change over time, and hugs might be treated as a photographable by the photographer raising the camera and by some (Sophie) aligning with it—contrary to others (Grace) engaging in another project. The photographable might be oriented to as such, even in the absence of taking any photos (Extract 1b). Finally, the photographable might be shot, like in next extract which shows the immediate continuation:

Extract 1c

While Grace is still oriented toward Heidi, the photographer instructs her to adopt a pose for the photo (17)—her self-repairs ending in a summons show that she treats Grace as not yet ready for the pose. This occasions Grace’s reorientation toward the camera (17) and her repositioning in front of it (20), along with the photographer’s instructions first delineating who is in the frame (19) and then specifying their positioning in space (21)—while the other bystanders move out of the frame. The photographer approaches the mother and her daughter hugging each other (Figure 5), stabilizes her posture, raises the camera, and then takes a photo (25, Figure 6).

In this extract, the hugging pair is explicitly instructed to position in front of and for the camera, transforming their affectionate posture into a photographable that is finally captured by the camera. Thus, these first extracts show how a mutual haptic contact—a haptic configuration—is transformed moment by moment from a spontaneous intimate moment into a photographable target—a haptic composition—seized in an occasioned way and finally into an instructed pose for the photo. The visible and observable aspect of the hug gradually evolves from something that is seen-but-unnoticed to something that is noticed and oriented to and to something that is finally framed and captured by the perspective of the camera.

Generic instructions interpreted as hugs

The previous section has shown how hugs can be opportunistically caught as they emerge but also orchestrated by the photographer. This section focuses more closely on the latter trajectory, in which hugs are directed for the photo. There are diverse ways of doing so: In this section, we focus on how generic instructions, like “let’s take a photo together,” are immediately understood and responded to by hugging.

New poses or photographs can be instructed by saying “together with N.” Participants often respond to these instructions by hugging. This reveals the participants’ orientation to “togetherness” (Rose, Citation2004): They respond not only by assembling as a “with” (Goffman, Citation1971) but also by embodying togetherness in a haptic configuration, the hug. The hug achieves the sense of being closely together and reflexively constitutes the intimacy of the family as a photographable haptic composition.

The following extract shows how the instruction “zusammen mit omi”/“together with grandma” is interpreted by Alina and her grandmother, Elisabeth:

Extract 2 (PHO_BS_301016_2255)

Photographer summons Alina (1) who is walking along the path. As she turns back to her, the photographer proposes the next pose: “together with grandma” (3). This generic instruction is responded to by Elisabeth looking at Alina and extending her arm toward her (3, Figure 7) and by Alina also extending her arm while coming closer to her grandmother (Figure 8). They hug one another, by putting their arms around (6, Figure 9), and Alina leans toward her grandmother (Figure 10) in an affectionate cuddle.

The photographer raises her camera, orienting to the emerging haptic configuration of the hugging bodies as a photographable. Alina and her grandmother also format their hug in such a way that it is positioned in front of the camera. They hug side-by-side (vs. a reciprocal hug where the bodies are frontally in contact and which might be more difficult to photograph). Prior to taking a photo, the photographer requests Alina to fix her hair and then she will take some shots (not shown in the transcript).

The reference to togetherness is systematically responded to by getting closer and hugging, as observable in the next extracts. In the following extract, the photographer invites Grace to join her husband, Lucas, who stands nearby, after a series of photographs with the children:

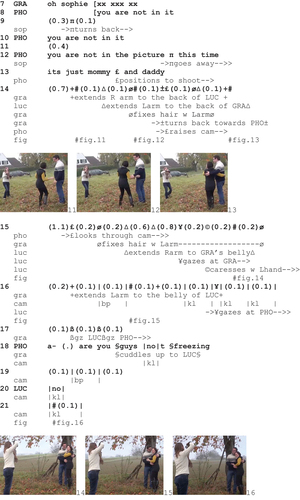

Extract 3 (PHO_BS_301016_1825)

The photographer summons Grace (1), and invites her to join Lucas, proposing to do some photographs of them “together” (3). In the midst of her utterance, their daughter, Sophie, starts running forward, toward the scene (3). Upon the completion of the photographer’s proposal, Grace walks toward the scene (4), verbally accepting her invitation (5). Thus, the photographer’s next photo proposal (“let’s do some of you together,” 3) is responded to, interpreted and understood by different participants in varying ways. Whereas Lucas maintains his position from the previous shots, displaying his understanding of the proposal as involving him in the picture, Grace initiates her movement toward Lucas, exhibiting her treatment of the proposal as involving herself with Lucas, and Sophie also begins to move toward the scene, demonstrating her interpretation of the proposal as including herself in the photo.

While walking forward, Grace calls Sophie, treating her movement to the scene as inapt. In overlap, photographer explicitly announces that Sophie is not in the picture (8). As Sophie turns toward the photographer, the photographer reiterates her announcement (10). In this way, both Grace and the photographer display their orientations to the next photo as not involving Sophie. The photographer then provides an explicit account that Sophie is not involved in the picture “this time” (12), which will feature “just mommy and daddy” (13). The mention of the categories implicates a couple photograph, and the “just” works to exclude any other persons apart from Grace and Lucas in the picture.

As photographer positions herself for the next shoot, Grace gets closer to Lucas. While she is one step away from him, she starts to extend her right arm to the back of Lucas (Figure 11). In doing so, she projects to hug him sideways while they both will face the photographer. Lucas also extends his right arm to the back of Grace (Figure 12). They hug one another, which is treated by the photographer as a photographable as she raises her camera and readies herself to shoot (Figure 13).

While Grace and Lucas are in a hugging formation and the photographer is ready to produce some shots, Grace lifts her left arm up and fixes her hair. As she does so, Lucas extends his right arm to Grace’s belly and stares at her affectionately (Figure 14). Lucas caresses Grace’s back with his hand resting on her shoulder up and down. While Grace engages in preparing her appearance for the photograph, Lucas establishes the affective tone of their embodied contact by adopting a distinctive form of romantic hugging, including embracing and caressing. In different but complementary ways, both maintain their contributions to the constitution of their haptic composition for the photo to come. After fixing her hair, Grace moves her left arm toward the belly of Lucas, reciprocating his arm positioning (Figure 15). Looking through her camera, the photographer snaps a shot, which demonstrates her seeing of the haptic composition as a photographable. Her snap is hearable first as a beep and then as a shot (16). Following this sound, Lucas shifts his gaze toward the photographer who then produces two more shots in a series (16). While keeping her camera up, the photographer initiates a turn at talk, inquiring about whether they feel cold (18). This utterance might be triggered by a noticing of Lucas’ caressing Grace’s back and shoulder. Rather than treating the caress as part of the contact of an affectionate couple, the photographer introduces the possibility that the cold weather may be the reason for the caress. As the photographer does so, Grace cuddles up to Lucas (Figure 16), after which the photographer produces a series of shots.

The association between “together”/“zusammen” and hugging is further confirmed by an instance in which the photographer utters it as a single-word turn (4) while doing the gesture of hugging (Figure 17A)—instructing Heidi to engage in a haptic composition with her daughter, Alina:

Extract 4 (PHO_BS_301016_1940)

Transiting to a new pose, the photographer summons Heidi and Alina for a photo (1). The summons orients to their engagement in a playful activity, initiated by the mother, tapping Alina’s back (2). Although facing the camera, Alina keeps her hands in the pockets and steps back, in a way that resists both to what the mother is doing and to a contact with her. The production of “zusammen” with a hugging gesture (Figure 17A)—obtained by crossing the arms on the chest—orients to this configuration (Figure 17B), which is treated by the photographer holding the camera at her chest level (vs. raising it up) as not (yet) constituting any photographable. The instruction is further expanded by asking the participants to come closer, which is accounted for as a defense against the cold weather (7). The multimodal gestalt, constituted by the “zusammen” and a hugging gesture, works as an instruction in a situation in which the participants are visibly disaligned with the objectives of the photographer (Figure 17B). The multimodal gestalt confirms the possible understanding and implementation of “together” as a hug.

In this section, we have demonstrated that generic instructions mentioning togetherness are immediately understood and complied with a hug. The multimodal format of these generic instructions includes not only the expression “zusammen”/“together” but also prepositions like “and” (as you and mom) or “with” (as with your sister). This shows that hugs embody a fundamental form of intimate “with” (Goffman, Citation1971)—in turn they are seen and ascribed as being a “body gloss” (Goffman, Citation1971) that is not only visibly witnessable and recognizable by social gaze but also constitutes a good photographable representing closeness and happiness.

Explicit instructions following generic instructions

Hugging compositions can be obtained through generic instructions (see above) or by means of explicit instructions to hug, using the lexical form of the verb “to hug.” In some cases, as shown in this section, both are used, successively specifying the instructed action: first the former, then the latter. This again demonstrates the strong relationship between the two.

We join the action in a transition to a new pose where the kids (Sophie and Thomas) are disassembling (Figure 18). The photographer proposes Sophie to do a picture of “just” her (1), yet in response Sophie turns toward her brother, Thomas (Figure 19):

Extract 5 (PHO_BS_301016_0105)

Sophie turns to Thomas and puts her hands on his chest, beginning to push him gently away (Figure 20). This bodily conduct is seen and understood by the photographer as her interest in doing a photo “with” Thomas (“do you wanna go,” 3)—while it seems that Sophie is rather organizing the moving away of her brother to have the field free for a single photo of her, aligning with the photographer’s proposal. The photographer not only ascribes this intention to her (3) but expands it into a further understanding of the trajectory of her movements as about to hug Thomas (5). Meanwhile, the photographer raises her camera, displaying her treatment of this as a possible photographable, distinct from her initial project.

Sophie responds to the photographer by modifying the position of her hands on Thomas: She moves them from his chest (which she was pushing, Figure 20) to behind his shoulders (Figure 21), from where she hugs him. Given that Thomas at that point begins to step away, Sophie ends up hugging him from behind, in a posture that both embraces and controls him (Figure 22).

In these few seconds, we can observe different actions that are built, understood, and ascribed in different ways. The photographer produces a request for permission for a photo of just Sophie (1). Sophie’s turning to Thomas is a response that is understood as proposing an alternative photo (with Thomas), while it can be designed as aligning and complying with the photographer’s initial project (single photo of just herself). Likewise, her hands pushing Thomas away are complying with the photographer’s request but are interpreted by her as a counterproposal. Action ascription of embodied conduct—which is relevant for the photographer’s shooting of the haptic composition—is here formulated in so many words (3, 5).

This formulation is responded to by Sophie who modifies her own project, now hugging her brother, as he walks away. The photographer summons Thomas (7) who nonetheless leaves the scene, orienting to something else (8). Sophie lets him go but maintains her arms open. This posture (Figure 23), while she looks at the camera, is first responded with response cries (10–12) and then formulated in so many words by the photographer (14, 16) after she has taken two shots (13). The formulation again attributes Sophie the intention to hug Thomas.

This extract offers several hints for our analysis of hugs and more generally for embodied conduct and its visibility. First, it shows how doing a photo “with” somebody is further glossed as a hug, confirming our earlier demonstrations where “together” is understood as and implemented in a hug. Second, it shows the relevance of the visibility of trajectories of embodied conduct for action recognition and ascription: The movements done by Sophie are seen by the photographer who interprets them in particular ways, relevant for her work of taking photographs. In this case, action formation is visible for analysts on the video and action ascription is explicitly formulated by the participants, constituting a particularly clear piece of evidence for the multiple ways in which the visible embodied formation of actions can be situatedly interpreted by the participants. Third, this extract shows an instance of resistance to be hugged. The hug itself is unilaterally initiated and performed; it not only engages in an affectionate hug but also exerts a control on the hugged body. Fourth, we can notice how the visibility of the embodied conduct of the protagonists is witnessed by different recipients: not only the photographer but also Grace (the mother), watching and monitoring the scene with other members of the family (Figure 23).

Instructed hugs

In the previous sections, we have examined hugs that emerge either spontaneously or in an instructed way with generic expressions or/and with more specific expressions, also involving explicit references to hug. In this section, we pursue a systematic examination of the more explicit instructions in which the multimodal format of the instructing action includes the use of the verb “to hug.” Our analyses include the way in which the haptic configuration is not only assembled by the participants but also treated as a photographable by the photographer. We examine how explicit instructions to hug are proffered, and how they involve several instructing participants other than the photographer, such as the parents (supporting the photographer’s work, Extract 6) who can mediate the instruction by translating (Extract 7) or initiate the haptic configuration for the photographer (Extract 8). This shows how the resulting photographs are collective accomplishments by all related participants engaging in the action within the global project of reproducing the family for the photograph.

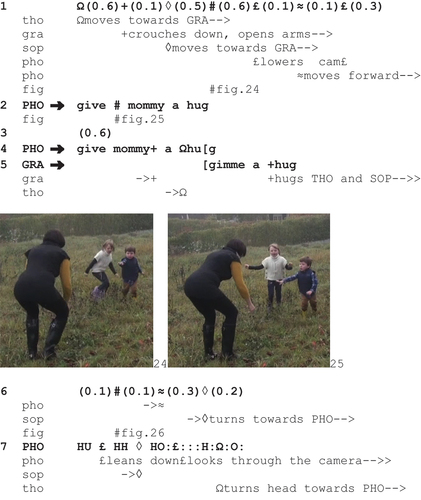

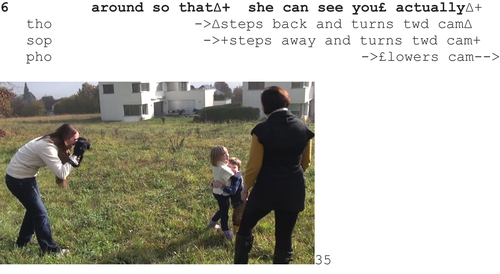

In the following extract, the photographer has been shooting some pictures of Grace running, followed by her two kids, Sophie and Thomas. Once the mother approaches the photographer, she slows down and turns to her right, changing her trajectory. Seeing that the children are not still following her, she turns toward the photographer and stabilizes her position. When the kids get close to the photographer, they stop running for a while. We join the action as both kids start again to run toward their mother:

Extract 6 (PHO_BS_301016_0250)

After Thomas initiates his movement toward his mother, his mother crouches down and opens her arms. Sophie follows her brother, and they both run toward their mother (Figure 24). The photographer lowers her camera, displaying her treatment of the emergent running of the kids as not constituting a photographable anymore. Yet, the photographer follows the kids from behind, which shows her interpretation of the conduct of the mobile participants as possibly relevant for her activity of photographing. As she follows the kids, the photographer produces an explicit instruction (“give mommy a hug,” 2). While she utters this, mom keeps crouching down while slightly opening her arms, and the kids are already in motion toward her (Figure 25). The photographer’s instruction treats the emergent haptic configuration as possibly relevant to produce a hug. While the kids continue their run toward their mom, the photographer reiterates her instruction to hug (4), which treats the kids as not yet complying and aligning with her instruction, even though their arms are moving to sides. Grace reformulates the photographer’s instruction by modifying the pronoun referring to herself (“gimme me a hug,” 5), through which she displays her alignment with the photographer’s proposal.

After the kids reach their mom, mom hugs both of them (Figure 26). Having been hugged, Sophie begins to turn toward the photographer: Now she is performing the hug for the camera. The photographer leans down and looks through the camera, treating this—still emerging—haptic configuration as a photographable. As the photographer assesses it with a vocalization (7), Thomas turns his head toward the camera as well. Sophie cuddles up to her mom (8, Figure 27), while the photographer produces a series of shots, documenting this haptic composition (8).

While in Extract 6, the mother is included in the haptic configuration to be built, in the next extracts the parents are clearly situated outside the interactional space of the photographer–photographable. In such a spatial organization (see Kendon, Citation1990; Mondada, Citation2009), they are observing, and possibly watching, the scene. Yet, they might also intervene in the composition of the scene by mediating the instructions (Extract 7) or by initiating them in the first place (Extract 8).

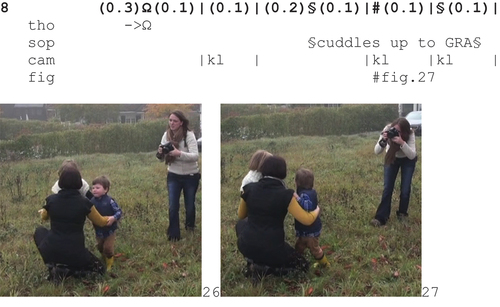

In the following extract, we join the action as the photographer initiates a new series of photos with the kids. She asks the little brother, Michel, to hug his sister, Sheila (1):

Extract 7 (PHO_BS_240916_2750)

Photographer’s instruction is formatted as a multimodal gestalt including a hugging gesture (Figures 28A/28B, see also Extract 4). It is addressed to the little brother, and reissued, with the same gesture again, in a recipient-designed way (3), referring to the toy he holds in his right hand. While Michel does not respond, Sheila replicates the hug gesture (Figure 29) and then turns to Michel, displaying her expectancy of some responsive action. As Michel does not move, Marie, their mother, translates the instruction into French (5), and the photographer repeats the recipient-designed description of the instructed hug (6). She also lifts up her camera, manifesting her expectation of a response, which would possibly be a photographable. Both parents (Marie and Denis) respectively produce a summons to Michel (8–9), and Marie reissues the instruction again (11), while the photographer holds the camera at her eye level, ready to shoot. Then, Sheila turns to Michel and initiates the hug, opening widely her arms. Michel responds immediately, also opening his arms (Figure 30). They accomplish a reciprocal hug (Figures 31A/31B). This is not only shot by the photographer but also vocally assessed by her and the parents (13–15).

In this extract, the hug is instructed in a recycled fashion. The instructions are addressed to—and specifically designed for—the little kid who does not respond and not to the older child who is more engaged in the activity. Issues of agency, age, and socialization are at stake here, also considering more marginal—or less controllable—participants. Moreover, other members of the family, in this case the parents, not only witness the scene (see also Extract 5) but also support the photographer’s instructions (see also Extract 6). In particular, Marie, the mother, produces several instructions to hug, recycling and reproducing the photographer’s instructions, through which she displays that she shares and even co-manages the global photographing activity with the photographer.

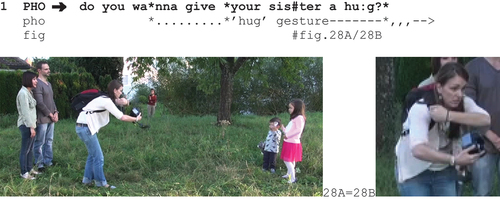

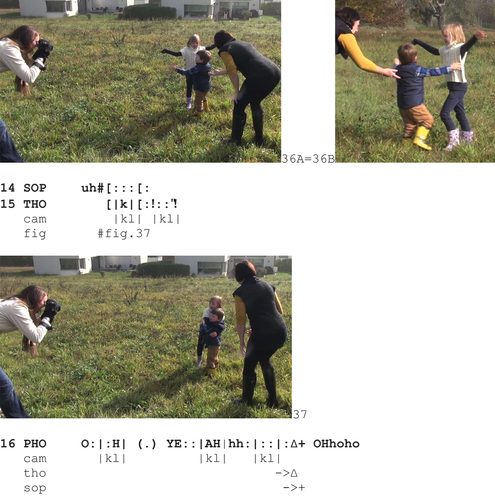

Other members of the family, rather than the photographer, may themselves instruct the hug, as in the next extract. We join the action after Sophie proposes “maybe mummy should (.) .h (.) photogra:ph.” (not shown), promptly rejected by her mom, Grace. However, Grace integrates her son in the next series of photographs by pushing him toward his sister (1):

Extract 8a (PHO_BS_301016_4505)

In this extract, it is the mother, rather than the photographer, who initiates the pose: She gives an explicit instruction (1) while pushing Thomas toward Sophie (Figure 32). First shepherded, then continuing his trajectory, Thomas collides with Sophie (Figure 33), who puts her arms around his shoulders (3). Consequently, they hug one another in a face-to-face formation (Figure 34). The emergent haptic formation is positively assessed by the photographer (2) who raises the camera, getting ready to shoot. She indeed produces a couple of shots (Figure 35) as well as a vocalization (4) while the kids strongly hug one another. Thus, the photographer’s responses address the distinct hugging formation, here orienting to the particular intensity of the hug.

The photographer continuously monitors the haptic configuration, orienting to possible photographable moments which can be captured. However, Grace—who has initiated the shooting of the hugs in the first place—also monitors the scene. She explicitly addresses the issue of photographability as a problem of visibility of the kids’ bodies for the photographer (5–6). Grace provides for a situated analysis of the conditions at which a hug is photographable. She addresses in particular that the hug currently accomplished is face-to-face (like “ordinary” hugs) and not side-by-side, that is, not designed for the photographer and her camera. Her corrective instruction addresses this issue (“actually,” 6) and highlights the problem with the current hug. The hugging kids separate and dissolve their bodily composition and turn toward the camera (6).

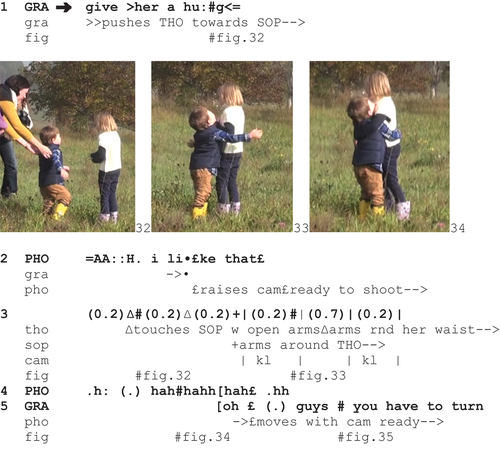

In the immediate continuation, Grace produces another instruction to hug (8):

Extract 8b

While pushing Thomas toward Sophie, Grace produces a new instruction to hug (8), which has the same format as the initial one, addressed to Thomas. Grace reissues her instruction by explicating the benefactor of the hug (“Sophie” in 10 vs. “her” in 8) and by supporting the instruction with a promise concerning a next activity (Thomas had previously expressed an interest for visiting some horses nearby). Both kids respond to this by opening their arms widely (Figures 36A/36B), projecting the hug. This projection enables them to coordinate themselves but also gives a hint to the photographer about their emergent haptic configuration. Both kids turn and look toward the photographer, transforming their initial face-to-face hug into a side-by-side hug which is designed for the camera. Ultimately, the resulting side-by-side hug is assembled by Sophie, who is bigger, embracing her brother from behind (Figure 37). This secures the visibility of the hug (in fact, of the bodily contact and the faces of the huggers) for the photograph—showing that the kids embody the instructed action in a way that integrates the previous correction, which could also be seen as contributing to their socialization not only to hug but to the photographability of the hug.

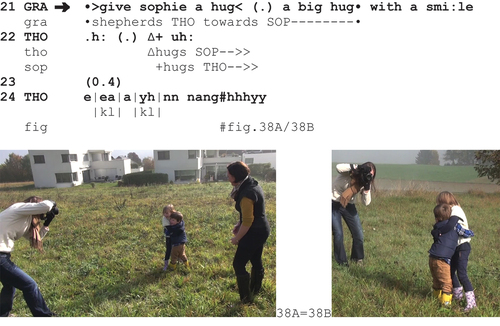

Despite the haptic arrangement is positively assessed by the photographer who produces some shots (16), Grace still engages in a new corrective instruction:

Extract 8c

The format of Grace’s instructing turn first repeats the previous one (21, cf. 10), but with a faster pace. It is then immediately followed by a corrective instruction, uttered with a slower pace and with an emphasis on “smi:le” (21)—while she shepherds Thomas toward Sophie. The kids respond to it by hugging (22) and turning toward the camera in a side-by-side position, looking at the camera and smiling (Figures 38A/38B). The photographer takes some photos (24), and the mother monitors the scene.

The mother orchestrates the hugs as photographables by producing explicit instructions and engaging in issuing relevant corrective instructions which are concerned with the visibility of the hugs for the camera. The first hugs are treated as not yet being a-good-enough-hug-for-the-camera. The mother’s corrective instructions mobilize progressively different body parts of the children (torso, head/gaze, face/smile), which shows how the body is dismembered and rearranged for the photo (see also Mondada & Tekin, Citation2020; Tekin, Citation2017). The way the kids respond to these instructions manifests how they make sense of the series of corrections, treat them as cumulatively addressing the progressive correction of the pose, and integrate them in an understanding not only of the indexicality of the directives but also of the global project they contribute to: the production of family photographs.

Discussion and conclusions

This article has examined the trajectories of spontaneous hugs, generically instructed hugs doing “being together,” and explicitly instructed hugs directed by the photographer and/or some other third parties. The organization of hugs involves not only the hugged parties (two, three, or more) but also larger participation frameworks (crucially the photographer, but also various family members and observers).

The article has examined instructions to hug, focusing on the action of instructing and its responses. It has highlighted the detailed way hugs are locally shaped by the instruction and collaboratively designed by the instructed participants, aligning not only with the instruction but also with the global project and goals of the photography sessions. In this sense, the instructing action—the directive to hug—is articulated not only with responses within locally produced sequences, but also within the larger activity. The instructed hug relies on a collective vision (shared by the photographer and their clients) of the emerging hugging haptic configuration and its photographability, which becomes a photographed haptic composition over time upon being shot. Thus, the analysis cannot be reduced to the recurrently used formats of the directives (give X a hug) but takes into consideration the constitutive details of the local context—making intelligible variations and transformations of the formats, as well as the corrections—and of the global project of taking family photos.

On this basis, we have described the interactional anatomy of hugging in its sequentially relevant specificities. The hug emerges out of a trajectory of embodied actions and is embedded in the ongoing activity. In this trajectory, movement is central: Hugs, similar to kisses (see Mondada, Monteiro, et al., Citation2020), are made possible by persons approaching their bodies closer to each other and can be implemented by implicating more or less intimate intercorporeal touch. This approach can be produced and seen as projecting hugs or not. Consequently, hugs can be observable and visible in their accomplishment; alternatively, the participants’ movements can be instructed and visibly inspected (and possibly corrected, occasioning the repetition of instructions or other adjustments). The photographer scrutinizes and orchestrates these movements: She can capture the serendipitous hugs or she can instruct more specific haptic compositions, by explicitly using lexical formulations of hugs as well as gestural enactments (see Extracts 4 and 7). These options account for the initiation of the hugs. Moreover, who initiates hugging might not always be the one who is instructed to hug (see Extract 7)—hinting at issues of agency, participation, entitlement, and socialization. The timing of the instruction relative to the ongoing trajectory of the participants’ and their embodied conduct also impinges on initiations and agency (Heath & Luff, Citation2021; Mondada, Citation2021; Tekin, Citation2021): The instructions might formulate what the participants are already projecting (the mother crouching in Extract 6) or might transform what they are doing into hugging (the children running in Extract 6).

The approaching movement projects the format of the imminent hug, for instance, when one or both participants extend their arms toward each other. This also indicates where the bodily contact will occur and what kind of hugging formation will be achieved. Ordinary spontaneous hugs might often happen as a face-to-face formation, which can be more or less (a)symmetric (in Extract 1, though they both use their two arms to hug, the mother is holding her daughter who embraces her on the shoulders). By contrast, hugs done for the camera are shaped as a side-by-side formation, in which the hugging bodies often face (and look at) the photographer (in Extract 3, the emergence of the hug involves each participant extending their arm around their waist, while they position their bodies in front of the camera—within a triangular interactional space). A diversity of hugging compositions is possible, not only side-by-side but also one-behind-another, also involving arms around the shoulders, the neck, the waist, also depending on the size of the participants (see also Mondada & Tekin, Citation2020; Tekin, Citation2017). The body parts involved in hugging might thus vary, in a limited versus all-embracing way, as well as their intensity, which might also be addressed, by the huggers as well as by the witnesses. Furthermore, the forms of the hugs index different relational categories (Sacks, Citation1992) visibly distinguishing the persons hugging, such as hugger–hugged (in Extract 6, the mother hugs her two children, which might also be referred to as a collective hug, or a multiparty hug, a term used by Goodwin & Cekaite, Citation2018, pp. 139–142).

The temporality of the shooting constrains the length of the hug: This enables slight transformations or adjustments—such as cuddling up (Extracts 2, 3, and 6) or caressing (Extract 3). Further movements can be noticed by the photographer (see her comment about the cold weather in Extract 3, which addresses the caress without formulating it or about the intensity of the hug in Extract 8a). They can increase the emotional quality of the photograph but can also disassemble the haptic composition (such as in Extract 5 where Thomas runs away or in Extract 8 where he continuously withdraws).

The photographer constantly monitors the emerging and resulting haptic compositions of the participants: This concerns the projectability of the embodied trajectories and the visibility of the photographable compositions, as well as their adequacy for the final portrait and family representativeness. Projectability is an important dimension of the visibility of social actions, on which the photographer’s work relies within a form of “ordinary vision” (shared with the other co-participants observing, monitoring, and co-directing the poses). We have shown that this ordinary vision is constitutive of action ascription, that is for the way embodied action is situatedly interpreted and treated (in particular, in Extract 5 the photographer’s local interpretation of pushing as hugging transforms the course of action). This contributes to wider debates about action ascription (see Deppermann & Haugh, Citation2022; Levinson, Citation2012) where the ascription of meaning to actions still tends to privilege their verbal formats, neglecting the ways in which embodied actions are seen and interpreted in situ. Moreover, this issue also concerns the “professional vision” (Goodwin, Citation1994) of the photographer: the identification of a detail as a photographable or, in absence of such detail, the orchestration of a photographable through instructions as well as the timed articulation between seeing the haptic configuration and shooting it. The action of the photographer integrates these various layers of visibility, which makes the photography sessions a perspicuous setting for discussing the intricate relations between visibility and accountability of social actions (including their projectable embodied trajectories) in general, and haptic practices in particular. By articulating together instructions, vision, and photographing in relation to haptic sociality, this article demonstrates the relevance of treating these different fields together—contributing to the analysis and conceptualization of the organization of action, language and embodiment.

Transcription conventions

Data are transcribed following current standards in ethnomethodology and conversation analysis: Gail Jefferson’s conventions for talk; Lorenza Mondada’s conventions for embodied actions (see https://www.lorenzamondada.net/multimodal-transcription).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bourdieu, P., ( with L. Boltanski, R. Castel, J-C. Chamboredon, & D. Schnapper). (1990). Photography: A middle-brow art. Polity Press.

- Broth, M., Laurier, E., & Mondada, L. (2014). Studies of video practices. Video at work. Routledge.

- Cekaite, A. (2016). Touch as social control: Haptic organization of attention in adult-child interactions. Journal of Pragmatics, 92, 30–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2015.11.003

- Cekaite, A., & Kvist, M. H. (2017). The comforting touch: Tactile intimacy and talk in managing children’s distress. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 50(2), 109–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2017.1301293

- Cekaite, A., & Mondada, L. (2020). Touch in social interaction. Touch, language, and body. Routledge.

- Deppermann, A. (2015). When recipient design fails: Egocentric turn-design of instructions in driving school lessons leading to breakdowns of intersubjectivity. Gesprächsforschung, 16, 63–101. http://www.gespraechsforschung-online.de/fileadmin/dateien/heft2015/ga-deppermann.pdf

- Deppermann, A. (2018). Instruction practices in German driving lessons: Differential uses of declaratives and imperatives. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 28(2), 265–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.12198

- Deppermann, A., & Haugh, M. (2022). Action ascription in interaction. CUP.

- Deppermann, A., & Schmidt, A. (2021). Micro-sequential coordination in early responses. Discourse Processes, 58(4), 372–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2020.1842630

- Ervin-Tripp, S. (1976). Is Sybil there? The structure of some American English directives. Language in Society, 5(1), 25–66. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404500006849

- Forsell, L. M., & Åström, J. A. (2012). Meanings of hugging: From greeting behavior to touching implications. Comprehensive Psychology, 1, 13. https://doi.org/10.2466/02.17.21.CP.1.13

- Garfinkel, H. (1967). Studies in Ethnomethodology. Prentice-Hall.

- Garfinkel, H. (2002). Ethnomethodology’s program. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Goffman, E. (1963). Behavior in public places: Notes on the social organization of gatherings. Free Press.

- Goffman, E. (1971). Relations in Public: Microstudies of the Public Order. Basic Books.

- Goffman, E. (1979). Gender advertisements. Harper & Row Publishers.

- Goodwin, C. (1994). Professional vision. American Anthropologist, 96(3), 606–655. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1994.96.3.02a00100

- Goodwin, M. H. (2006). Participation, affect, and trajectory in family directive/response sequences. Text & Talk, 26(4–5), 515–543. https://doi.org/10.1515/TEXT.2006.021

- Goodwin, M. H. (2017). Haptic sociality: The embodied interactive constitution of intimacy through touch. In C. Meyer, J. Streeck, & J. S. Jordan (Eds.), Intercorporeality (pp. 73–102). OUP.

- Goodwin, M. H. (2020). The interactive construction of a hug sequence. In A. Cekaite & L. Mondada (Eds.), Touch in social interaction. Touch, language, and body (pp. 27–53). Routledge.

- Goodwin, M. H., & Cekaite, A. (2018). Embodied family choreography. Routledge.

- Heath, C., & Luff, P. (2021). Embodied action, projection, and institutional action: The exchange of tools and implements during surgical procedures. Discourse Processes, 58(3), 233–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2020.1854041

- Hirsch, M. (1999). The familial gaze. University Press of New England.

- Kendon, A. (1990). Conducting interaction. CUP.

- Levinson, S. (2012). Action formation and ascription. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (Eds.), Handbook of conversation analysis (pp. 103–130). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Lindwall, O., & Ekström, A. (2012). Instruction-in-interaction: The teaching and learning of a manual skill. Human Studies, 35(1), 27–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10746-012-9213-5

- Meyer, C., Streeck, J., & Jordan, J. S. (2017). Intercorporeality. OUP.

- Mondada, L. (2009). Emergent focused interactions in public spaces: A systematic analysis of the multimodal achievement of a common interactional space. Journal of Pragmatics, 41(10), 1977–1997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2008.09.019

- Mondada, L. (2014). Instructions in the operating room: How the surgeon directs their assistant’s hands. Discourse Studies, 16(2), 131–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445613515325

- Mondada, L. (2021). How early can embodied responses be? Issues in time and sequentiality. Discourse Processes, 58(4), 397–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2020.1871561

- Mondada, L., Bänninger, J., Bouaouina, S. A., Camus, L., Gauthier, G., Hänggi, P., Koda, M., Svensson, H., & Tekin, B. S. (2020). Human sociality in the times of the covid-19 pandemic: A systematic examination of change in greetings. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 24, 441–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.12433

- Mondada, L., Bouaouina, S. A., Camus, L., Gauthier, G., Svensson, H., & Tekin, B. S. (2021). The local and filmed accountability of sensorial practices: The intersubjectivity of touch as an interactional achievement. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 4(3). https://doi.org/10.7146/si.v4i3.128160

- Mondada, L., Monteiro, D., & Tekin, B. S. (2020). The tactility and visibility of kissing: Intercorporeal configurations of kissing bodies in family photography sessions. In A. Cekaite & L. Mondada (Eds.), Touch in social interaction. Touch, language, and body (pp. 54–80). Routledge.

- Mondada, L., Monteiro, D., & Tekin, B. S. (2022). Collaboratively videoing mobile activities. Visual Studies, Online First, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2022.2086614

- Mondada, L., & Tekin, B. S. (2020). Arranging bodies for photographs: Professional touch in the photography studio. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.7146/si.v3i1.120254

- Nishizaka, A. (2020). Appearance and action: The sequential organization of instructions in Japanese calligraphy lessons. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53, 295–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2020.1739428

- Rizzo, L. (2013). Visual aperture: Bureaucratic systems of identification, photography and personhood in colonial Southern Africa. History of Photography, 37(3), 263–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/03087298.2013.777548

- Robinson, J. D. (2016). Accountability in social interaction. OUP.

- Rose, G. (2003). Family photographs and domestic spacings: A case study. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 28(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-5661.00074

- Rose, G. (2004). ‘Everyone’s cuddled up and it just looks really nice’: An emotional geography of some mums and their family photos. Social & Cultural Geography, 5(4), 549–564.

- Rose, G. (2010). Doing Family Photography. Ashgate.

- Sacks, H. (1992). Lectures in conversation. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Schegloff, E. A. (1997). Practices and actions: Boundary cases of other-initiated repair. Discourse Processes, 23(3), 499–545.

- Sorokowska, A., Saluja, S., Croy, I., Frąckowiak, T., Karwowski, M., Aavik, T., Akello, G., Alm, C., Amjad, N., Anjum, A., Asao, K., Atama, C. S., Atamtürk Duyar, D., Ayebare, R., Batres, C., Bendixen, M., Bensafia, A., Bizumic, B., Boussena, M., & Croy, I. (2021). Affective interpersonal touch in close relationships: A cross-cultural perspective. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 47(12), 1705–1721. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167220988373

- Spence, J., & Holland, P. (2000). Family snaps: The meanings of domestic photography. Ashgate.

- Svensson, H., & Tekin, B. S. (2023). Making a mistake, or cheating: Two sequential trajectories in corrections of rule violations. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 56(3), 191–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2023.2205300

- Tekin, B. S. (2017). The negotiation of poses in photo-making practices: Shifting asymmetries in distinct participation frameworks. In L. Mondada & S. Keel (Eds.), Participation et asymétries dans l’interaction institutionnelle (pp. 285–313). L’Harmattan.

- Tekin, B. S. (2021). Quasi-instructions: Orienting to the projectable trajectories of imminent bodily movements with instruction-like utterances. Journal of Pragmatics, 186, 341–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2021.10.018

- Vine, B. (2009). Directives at work: Exploring the contextual complexity of workplace directives. Journal of Pragmatics, 41(7), 1395–1405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2009.03.001