Abstract

Digital library services are frequently designed for specific user groups with very specific usage needs. This article presents a qualitative comparative analysis of findings derived from six user and usability studies in four different specialized subject information services. Rather than postulating hypotheses regarding variations in needs and behaviors among user groups, this article explores similarities among researchers’ requirements for specialized information service portals. The findings suggest that distinct subject areas may no longer require separate information systems tailored to each field’s specific needs. With the rise of interdisciplinary research, researchers increasingly favor the adoption of a unified system or multiple systems with consistent operation.

Introduction

Usability is defined as the “extent to which a system, product or service can be used by specified users to achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction in a specified context of use.”Footnote1 This suggests that digital services, such as digital libraries, repositories, or virtual research environments reach a high level of usability when their design is very much adapted to the needs of their targeted user group and its major task(s). In consequence, most usability studies focus on distinctive user groups and their specific needs, particularly on evaluations according to different subject domains.

The article questions this dominant usability evaluation approach to focus on differences between user groups, in particular, the tendency to mainly explore the differences caused by different subject backgrounds. The authors propose to put design for universality and interdisciplinary use first, and individuality second. This study is a meta-study that reports on results from six user studies across four different specialized subject information services. The research question addressed in the article is: What are researchers’ requirements for specialized information service portals, based on their information needs and usage behaviors?

The article is structured as follows: after a theoretical framework and an introduction to all four specialized information services, which form the basis for the meta-analysis, the methods and materials for this article are explained. Afterwards, users’ behavior across different specialized services is presented and discussed, along with the implications for the development of such services. The article concludes with a discussion on how to offer distinct services aimed to respond to information needs of specialized researchers, while simultaneously striving for a unified model of design.

Research background

Over the last 30 years of digital library service research, the differences in scholars’ information discovery and use of information sources have been a recurring theme. For example, Covi and Kling discovered major differences between two subjects in the use of digital libraries, as did Nicholas et al. and Arshad and Ameen.Footnote2 All three studies have a common starting point: the hypothesis of existing differences which their research design seeks to validate. Some studies further focus on different usage patterns of digital libraries by exploring differences in motivation and knowledge about digital libraries,Footnote3 examining diverse user groups in the academic context,Footnote4 and evaluating digital libraries by surveying various academic users about their satisfactionFootnote5 or search purposes.Footnote6 The literature on digital humanities scholars repeatedly highlights the differences among the groups.Footnote7

Few studies in this research area seek the similarities. Coming from a human-centered approach, those studies explore similarities in the usage of digital libraries.Footnote8 They examine factors that influence usage behavior beyond the typical demographic variables such as age, gender, or subject, and distinguish, for example, between levels of accessibility and familiarization with services.Footnote9 Further studies identified similarity criteria for the evaluation of digital libraries based on how students from different disciplines use them.Footnote10

Other studies that seek similarities are meta-studies on the evaluation of digital libraries. Saracevic and Covi, for example, write about challenges in the evaluation of digital libraries and introduce a framework for evaluation processes.Footnote11 Using this framework, they analyze different aspects of the evaluation and suggest uniformity in access and use as a criterion for the design of digital libraries. Fuhr et al. do not directly argue for similarities, but advocate for a “broad view of the subject area” instead of limiting the evaluation to specific problems.Footnote12 They introduce an evaluation scheme based on hosted data and collections, the choice of system and technology, users, and their usage.

User studies on the Collaborative European Digital Archive (CENDARI) have shown that a one-size fits all solution does not work, nor does a system that fulfills each requirement from the many user groups behind CENDARI, i.e., historian, archivists, and librarians.Footnote13 Their strategy for the development of CENDARI was to focus on “common needs amongst the different user groups.”Footnote14

Marchionini et al. focused on the design of digital libraries and commented already twenty years ago that in their opinion, it “is axiomatic that designing for universal access is much more difficult than designing for specific populations” because of different characteristics and user behaviors within different communities.Footnote15 Their assumption for the design of a national digital library service has been that it will “likely lead to multiple system solutions.” Their prediction was both wrong and right: it was wrong because large national and international digital library services which serve many different communities, were successfully built, most notably Europeana. They were right, because digital services for specific populations are the dominant form today, so the “multiple system solution” remains the most common design for specialized information service portals.

Introduction of the four research objects

This article presents six user experience and usability studies in four different specialized subject information services from Germany, which are all state-financed information and documentation services. Those digital library services have their roots in World War I and II, when the government realized that German scientists were cut off from international research and started building state-financed information and documentation services.Footnote16 In 2014, the German Research Foundation started funding “Fachinformationsdienste für die Wissenschaft”—specialized services for subjects (shortened FID), such as library and information science studies, German literary studies, ethnography studies, and others.Footnote17

The aim of those FIDs is to have access to information and library services for German researchers independent of the researchers’ current location. This means, for example, that German philosophical researchers can (request) access (to) all services from their subject FID independently, regardless of whether they work at a department of philosophy, at one of the state funded research institutions such as Fraunhofer or Max Planck, or live abroad. In 2024, there were 42 different specialized services funded by the German Research Foundation, each addressing its own research group and offering some sort of digital portal as an entry point to specialized services. Those services include, for example, a search portal, access to specialized subject databases, newsletters with funding opportunities and calls for submissions, or special training, i.e., on research data management for the targeted subject group.

According to the funding guidelines, the specialized subject services, FID, are required to fulfill the information needs of their user community.Footnote18 In consequence, all FIDs conduct various forms of user studies, from information need assessment surveys to usability evaluations. This article reports on six usability and user evaluation studies in four different portals, which are all funded by the German Research Foundation. All portals comprise different disciplines of humanities: Two of the portals belong to linguistic subjects, one covers manuscripts, and the last portal covers performing arts.

The first portal, the Handschriftenportal (HSP), is a portal of medieval and early modern manuscripts and the central resource for information on European book manuscripts in German collections (see ).Footnote19 This portal is still in its development stage, and so far contains search and browsing features for the manuscript catalog, which presents pictures of the manuscripts, as well as their metadata and descriptions. It also includes a digital workspace where selected manuscripts can be viewed in more detail using the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF).

The HSP portal is a joint project of the four major German libraries that collect medieval manuscripts. The German research foundation has supported this portal with more than eight million Euros since its beginning in 2018. It is not an official FID, but it has similar aims and functions and serves a very subject-specific user group.

Also, in 2018, Germanistik im Netz (GiN), the portal for German linguistics and literature studies, was launched (see ).Footnote20 This portal is located at the University Library Johann Christian Senckenberg in Frankfurt, same as the portal avldigital (AVL), the portal for general and comparative literature studies, which started already in 2016 (see ).Footnote21 FID GiN and FID AVL are similar in their layout and features. Both offer a search box as a first search entry for the catalog. Further, they provide thematic entries in specific aspects of each portal and their catalog.

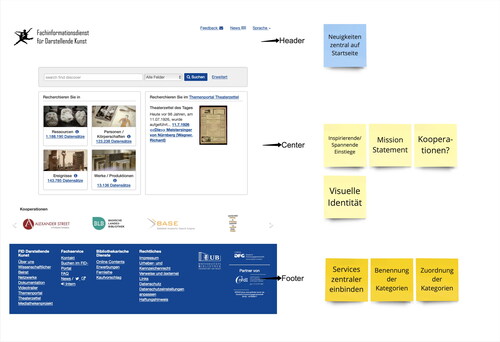

The last portal for analysis is the portal for performing arts (FID DK).Footnote22 This portal is also hosted at the University Library Johann Christian Senckenberg in Frankfurt and was one of the first portals of the funding line (see ). This portal is the only one in the sample that does not focus on literature or language and by this adds another perspective. The portal itself has a similar structure and comparable features to FID AVL and GiN. The first search entry is a central search box. Additionally, browsing categories containing specific aspects of the portal are represented.

Methods and research data

This article presents a comparative analysis of findings derived from distinct user experience and usability studies. Rather than adopting the conventional approach of postulating hypotheses regarding variations in needs and behaviors among user groups that require validation, this article takes a novel perspective by exploring similarities in the requirements of researchers when it comes to utilizing specialized information service portals, by reflecting on comparable cases based in the humanities. The authors of this article conducted the studies jointly with the respective librarians. While the protocols were very similar, they were not identical. Thus, the studies for this article were chosen because the authors were involved in those studies and had access to the data. Details for all studies follow and gives a summary overview.

Table 1. Methods used in all six usability studies across four specialized portals.

All participants signed an informed consent either before the study by email or at the beginning of an interview; templates of the informed consent are published as part of the individual study reports.Footnote23 The earliest study, on the medieval manuscript portal HSP, took place in 2020,Footnote24 followed by a follow-up think-aloud study with 13 participants on the same portal in 2021.Footnote25 Next, a remote asynchronous card-sorting test was conducted for the German linguistics and literature portal, FID GiN, in 2021,Footnote26 and a think-aloud study with six users for the portal for general and comparative literature studies, FID AVL, which took place in early 2022.Footnote27 The last two studies were completed for the portal of performing arts, FID DK, and consisted of another think-aloud study with 12 participants and a virtual usability workshop with 6 participants, which both ended in May 2023.Footnote28

The researchers in this project conducted asynchronous remote card-sorting testsFootnote29 using the software KardSort for the HSP study,Footnote30 and OptimalSort for FID GiN.Footnote31 The aim of card-sorting tests is to discover problems with the information architecture. In the two cases here, the existing navigation (FID GiN) and future filter options (HSP) were examined. Asynchronous, or sometimes called unmoderated, means that participants can take part in the card-sorting study at a time, on a device and in a place of their choice. Both card-sorting tests were open and included short pre- and post-surveys about participants’ characteristics (e.g., status group, research subject, etc.), their motivation and use of the portals, as well as questions related to their responses within the card-sorting tests (i.e., cards that they did not understand). Participants were invited using mailing lists and blog and social media postings. Both KardSort and OptimalSort require an entry link that was freely shared on the internet and afterwards participants could take part in the study similar to completing a survey.

For the follow-up study within HSP and the two most recent studies, FID AVL and FID DK, the authors conducted virtual think-aloud studies using Zoom due to the regional distribution of the participants. All think-aloud tests were based on semi-structured interview guides and analyzed qualitatively based on the interview transcripts. For the think-aloud protocols, structured interview protocols following the SPSS-approach by Helfferich were used.Footnote32 All think-aloud protocols were created based on specific requirements of FIDs. For this reason, different protocols were used in the studies. In the virtual think-aloud studies, participants were asked to complete typical tasks such as looking for a recent reference and exploring what the FID has to offer. The follow-up interviews explored further information needs and concrete wishes for the future development of the FID.

Finally, for the FID DK study, the authors first conducted the virtual think-aloud studies, analyzed the results, and brought them back for discussion to a participatory workshop with a sub-set of the participants. This workshop was conducted digitally using Zoom as well. Self-created Miro boards, hosted on the miro.com platform, provided the framework for both the synchronous card-sorting activity during the workshop and served as a reference point for guiding the directed focus group discussion. As one of the researchers facilitated the workshop and dynamically adjusted the arguments and key points, participants could solely concentrate on the discussion, eliminating the necessity to familiarize themselves with platform functionalities beforehand (see ).

The asynchronous card-sorting studies had 56 (HSP) and 92 (FID GiN) participants, while the think-aloud protocols each involved between 6 and 13 participants, and the FID DK usability workshop included 6 participants.

Researchers are the main target group of the German specialized information services; therefore, the majority of participants were researchers from their respective areas, including early career stage and senior researchers. An exception was participants in FID DK and FID which also included practitioners from memory institutions such as Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums. For FID GiN, the survey showed that 13% of all 92 participants categorized their profession as “other groups,” which were not further specified, and 10% of the participants work as academic consultants. Thus, not only scientists participated in those two studies.

summarizes the type and distribution of methods that were applied in all six studies. This article uses a comparative approach, where the individual results of the six case studies are combined and examined under the lens of the above research question.

Results

This article aimed to discover researchers’ requirements for specialized information service portals based on their information needs and usage behaviors. The result section follows a meta level reporting structure and does not make use of quotes from the individual studies. The quotes as well as the detailed study designs can be found in the original studies, cited above.

The three studies with think-aloud interviews and the usability workshop focused on concrete usability experiences regarding the FIDs within researchers’ subject area. Participants were asked to describe how they used the portals, demonstrate their information-seeking process using a current research question that they have, and express their needs toward the services. Furthermore, the assessment of layout and specific functionalities related to the FID was conducted with a specific focus on individual usage preferences and patterns.

A detailed analysis of preferences in catalog design, FID structure, and functionality discovered redundancies and less-utilized services. When comparing the usage patterns of participants in all four portals, we found that there were no discernible subject-specific usage patterns. The only significant distinctions that could be discerned were related to information-seeking, particularly regarding the level of data detail and the preference for either image or text data. Furthermore, within the search catalogs, a preference for either filters or advanced search became apparent, which is closely related to people’s level of familiarization.

It appears that researchers follow similar workflow processes regardless of the subject and data types, including a consistent approach to using catalogs. Despite the significant differences in data and services provided by the four portals, participants exhibited remarkably similar usage patterns: most of them initiated their interaction with a search request rather than exploring the various services featured on the main page, stating that this was their typical behavior.

Subsequently, the research designs included an in-depth examination of the catalog, its functionality, and its content. In this context, distinctions emerged regarding the inclination toward using search filters as opposed to employing advanced search operators. Notably, this differentiation was equally pronounced among participants within the same subjects as it was among those from different subjects. Hence, it appears to be a matter of personal preference influenced by familiarity and expertise, rather than subject-specific usage patterns. A similar pattern was observed with other catalog functionalities and the catalog’s structure.

Regardless of their subject, almost all participants made a comparison with the library catalogs of their research institution, which they use regularly. Particularly in smaller academic disciplines, a service for facilitating contact or disseminating announcements holds significant relevance. On the other hand, additional services such as newsletters, third party project documentations, or event calendars were, in all studies, seen as nice add-ons but were rarely used, if noticed at all. The same holds true for library-specific services that researchers typically access via their affiliated research institution’s library.

show the entry page for similar services, but they are very different in design and entry point. Participants noted that in their research process, they rely on multiple resources and, therefore, favor similar, if not identical, usage practices for these services. This was particularly emphasized in light of the desire for FIDs to be user-friendly, a quality that became particularly evident in smaller fields or specialized research areas where the use of interdisciplinary sources is common. However, participants also expressed the need to have their own specialized service, their FID of their own research area, as valuable sources tend to get buried amidst the extensive catalogs of larger subject areas, making them challenging to locate. Thus, all participants in the studies expressed gratitude for the existence of their subject-specific portal.

Participants also emphasized the importance of being able to quickly grasp the website’s structure and easily discern where they can perform specific actions. This may not sound innovative, because it is at the heart of what user experience design does, but it still is not fully implemented in the digital library world. As the studies indicate, the core function of the FID portals as a search tool is similar. Nevertheless, it is evident that both the structure and content of these portals exhibit significant diversity in terms of hyperlink organization and the nomenclature of similar categories. Even the functionalities and the structure differ, which restricts intuitive use.

The card-sorting tests demonstrated another important similarity. For the HSP project about the medieval manuscript portal, participants came from various subject areas—all with an interest in manuscripts, of course. Again, despite large participant numbers (56 for HSP and 92 for GiN), there was no evidence of a statistical difference between behaviors within the participant groups. What united them were issues related to unclear terms. Participants from all subjects sorted cards very similarly and therefore expected to find the information on a website in similar places. Moreover, when the information service employed specialized terminology, participants sorted those cards without any discernible pattern, indicating a lack of understanding of these terms and, consequently, uncertainty about the outcome of clicking on such subpages within the portal. From this observation, it can be inferred that for specialized information services, it is best to adopt a consistent design with commonly understood terms and to avoid library jargon or subject-specific language from various disciplines.

Especially for interdisciplinary purposes, having similar portal interfaces is beneficial for facilitating the seamless utilization of various FIDs and promoting a quick and intuitive comprehension of these distinct portals. In addition, having a centrally located mission statement is imperative to enable interdisciplinary users to promptly discern what they can anticipate from the FID and whether it can prove beneficial for their research.

Discussion

The results of all six studies show that users of specialized digital library services may express how different they are when it comes to getting funding or keeping positions within research structures, but that their information needs and information usage behaviors are very similar. The hypothesis of researchers such as Covi and Kling, Nicholas et al., and Arshad and Ameen about the different use of digital libraries according to subject hence cannot be confirmed.Footnote33 Based on previous studies in the field, it was expected to discover subject-specific usage patterns. However, those were rarely visible.

From a librarian’s standpoint, the rationale behind advocating for specialized services is rooted in the significant disparities among data types. Researchers from performing arts are more likely seeking visual data such as illustrations from performances, while the German linguists are more likely to seek large text corpora. If the data are very different, the information infrastructure must be very different. However, while the backend must accommodate various data types, it may not be essential to replicate this complexity in the frontend. On the contrary, a uniform presentation is preferred in the frontend to facilitate intuitive utilization of FIDs from related subjects.

Participants expressed that they are (no longer) willing to learn how to use services and expect that library services implement standard user experience practices. They prefer similar systems instead of specialized systems created only for them. None of the participants expressed the wish that the specialized services are just Google-like. They are comfortable with specialized services for research purposes, but request that those services is similar in function. This was also evident in the challenge researchers faced when encountering unfamiliar vocabulary. A hallmark of a well-designed specialized service is the consistency of similar functions working in a similar manner. Consistent interface structures prove beneficial for the seamless utilization of various specialized information services and contribute to a rapid and intuitive comprehension of these diverse information resources. They need to be “walk up and use systems that are easily learned” as Blandford et al. said about libraries in 2001.Footnote34 The same applies to digital libraries and specialized information services.

It is worth noting that all participants still emphasized the need for the continued existence of specific FIDs for their research fields, in which subject-specific data and information is made available and can be found easily. At the same time, participants request the handling of other subjects should be intuitively accessible. The reason for this change in behavior may be seen in an increase of interdisciplinary research. Researchers can no longer limit their search to utilizing information resources from just one subject area; they often need to access information from two, three, or even more subject specific sources. It is understandable that researchers might be hesitant to familiarize themselves with three times as many systems and specialized terminologies compared to their colleagues. As interdisciplinary work continues to grow, this trend may evolve from being the exception to becoming the norm.

A limitation of the project is that it only examined a small number of available FIDs and that, at present, no specialized service from the natural science area was included. All six studies were designed by the same authors, which may have influenced the results.

Conclusion

This article examined researchers’ requirements for specialized information service portals based on their information needs and usage behaviors. Data from six user and usability studies on German specialized digital library services were collected between 2021 and 2023, and results were examined under the lens of similarities and differences between researchers from different subjects.

Traditionally, it has been believed that distinct subject areas necessitate separate information systems tailored to the specific requirements of each field of study. What this article reveals that in reality, researchers across various subject areas tend to approach information systems in a similar manner. Due to the prevalence of interdisciplinary work, researchers prefer to have a unified system or multiple systems that operate consistently.

Previous studies showed large differences in usage behaviors between subject domains when seeking information. The findings of the current study indicate the contrary: the seeking behaviors were very similar and participants criticized when digital services were too different. Participants explained this with their interdisciplinary background and the need to use multiple specialized services for their research purposes.

Libraries as the stakeholders in the backend receive grant funding to develop multiple services for specialized user groups. Each difference means the chance of extra funding. Going for similarity in design and services steering toward some form of universal design may in the long run reduce funding income. Future developments of digital services ought to discuss how this act can be best balanced: offering distinct services to the information needs of specialized researchers and at the same time striving toward a unified model of design.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all project partners, who initiated the usability studies and supported the recruitment process for the six studies. The authors also thank Kirsten Schlebbe for her help with the study FID DK.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 International Organization for Standardization, ISO 9241-11:2018 Ergonomics of human–system interaction - Part 11: Usability: Definitions and concepts (Geneva, Switzerland: ISO, 2018).

2 Lisa Covi and Rob Kling, “Organisational Dimensions of Effective Digital Library Use: Closed Rational and Open Natural Systems Model,” in Culture of the Internet, edited by Sara Kiesler (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1997), 343–60; David Nicholas, Ian Rowlands, Paul Huntington, Hamid R. Jamali, and Patricia Hernández Salazar, “Diversity in the E-Journal Use and Information-Seeking Behaviour of UK Researchers,” Journal of Documentation 66, no. 3 (2010): 409–33; Alia Arshad and Kanwal Ameen, “Comparative Analysis of Academic Scientists, Social Scientists and Humanists’ Scholarly Information Seeking Habits,” Journal of Academic Librarianship 47, no. 1 (2021): 102297.

3 Feryal Turan and Özlem Bayram, “Information Access and Digital Library Use in University Students’ Education: The Case of Ankara University,” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 73, no. 2 (2013): 736–43; Jiming Hu and Yin Zhang, “Chinese Students’ Behaviour Intention to Use Mobile Library Apps and Effects of Education Level and Discipline,” Library Hi Tech 34, no. 4 (2015): 639–56.

4 Iris Xie, Soohyung Joo, and Krystyna K. Matusiak, “Multifaceted Evaluation Criteria of Digital Libraries in Academic Settings: Similarities and Differences from Different Stakeholders,” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 44, no. 6 (2018): 854–63; Wei Xia, “Digital Library Services: Perceptions and Expectations of User Communities and Librarians in a New Zealand Academic Library,” Australian Academic and Research Libraries 34, no. 1 (2013): 56–70.

5 Fang Xu and Jia Tina Du, “Examining Differences and Similarities Between Graduate and Undergraduate Students’ User Satisfaction with Digital Libraries,” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 45, no. 6 (2019): 102072, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2019.102072.

6 Paul Clough, Timothy Hill, Monica Lestari Paramita, and Paula Goodale, “Europeana: What Users Search for and Why,” in Research and Advanced Technology for Digital Libraries. TPDL 2017. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Thessaloniki, Greece: Springer Cham, 2017), 207–19.

7 Lisa M. Given and Rebekah Willson, “Information Technology and the Humanities Scholar: Documenting Digital Research Practices,” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 69, no. 6 (2018): 807–19, https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24008; Claire Warwick, “Studying Users in Digital Humanities,” in Digital Humanities in Practice, ed. Claire Warwick, Melissa Terras and Julianne Nyhan (Facet, 2012), 1–22.

8 Xu and Du, “Examining Differences and Similarities.

9 Elahe Kani‐Zabihi, Gheorghita Ghinea, and Sherry Y. Chen, “Digital Libraries: What Do Users Want?” Online Information Review 30, no. 4 (2006): 395–412; Pauline Melgoza, Pamela A. Mennel, and Suzanne D. Gyeszly, “Information Overload,” Collection Building 21, no. 1 (2002): 32–43; Xu and Du, “Examining Differences and Similarities.”

10 Hong Iris Xie, “Evaluation of Digital Libraries: Criteria and Problems from Users’ Perspectives,” Library & Information Science Research 28, no. 3 (2006): 433–52; Hong Iris Xie, “Users’ Evaluation of Digital Libraries (DLs): Their Uses, their Criteria, and their Assessment,” Information Processing & Management 44, no. 3 (2008): 1346–73.

11 Tefko Saracevic and Lisa Covi, “Challenges for Digital Library Evaluation,” Proceedings of the ASIS&T Annual Meeting, no. 37 (2000): 341 − 50.

12 Norbert Fuhr, Preben Hansen, Michael Mabe, Andras Micsik, and Ingeborg Sølvberg, “Digital Libraries: A Generic Classification and Evaluation Scheme, “in Research and Advanced Technology for Digital Libraries. ECDL 2001. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 2163 (Springer, 2001), 187–99.

13 Klaus Thoden, Juliane Stiller, Natasa Bulatovic, Hanna-Lena Meiners, and Nadia Boukhelifa, “User-Centered Design Practices in Digital Humanities – Experiences from DARIAH and CENDARI,” ABI Technik 37, no. 1 (2017): 2–11, doi: 10.1515/abitech-2017-0002.

14 Thoden et al., “User-Centered Design Practices in Digital Humanities,” 9.

15 Gary Marchionini, Catherine Plaisant, and Anita Komlodi, “The People in Digital Libraries: Multifaceted Approaches to Assessing Needs and Impact,” in Digital Library Use: Social Practice in Design and Evaluation, ed. Ann Peterson-Kemp, Nancy A. Van House, and Barbara P. Buttenfield (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2003), 119–60.

16 “Dokumentationseinrichtungen,” Bibliotheksportal, Deutscher Bibliotheksverband e.V. (dbv), last modified January 17, 2023, https://bibliotheksportal.de/informationen/bibliothekslandschaft/dokumentationseinrichtungen/

17 “Förderprogramm “Fachinformationsdienste für die Wissenschaft,” DFG, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft e.V., last modified February 9, 2023, https://www.dfg.de/de/foerderung/foerdermoeglichkeiten/programme/infrastruktur/lis/lis-foerderangebote/fachinfodienste-wissenschaft

18 Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, “Module Basic Module” (06/20, DFG, Bonn, 2020), accessed April 28, 2024, https://www.dfg.de/formulare/52_01/52_01_en.pdf

19 “Handschriftenportal,” Handschriftenportal, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, last modified NA, accessed April 28, 2024, https://handschriftenportal.de/

20 “Germanistik im Netz Forschungsinformationsdienst,” Germanistik im Netz, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität Frankfurt, last modified NA, accessed April 28, 2024, https://www.germanistik-im-netz.de/

21 “avldigital.de Fachinformationsdienst Allgemeine und Vergleichende Literaturwissenschaft,” avldigital, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität Frankfurt, last modified NA, accessed April 28, 2024, https://www.avldigital.de/

22 “Fachinformationsdienst für Darstellende Kunst, “performing-arts, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität Frankfurt, last modified NA, accessed April 28, 2024, https://www.performing-arts.eu/

23 The six studies in this article were accepted by the ethics board of the Humanities Faculty at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, because they neither collected potential harmful or sensitive data. The informed consent as well as the full research designs including the interview protocols are published in the reports from the individual studies cited below.

24 Elke Greifeneder and Paulina Bressel, “Studie zur Präsentation der Facetten auf dem Handschriftenportal” (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, GER, 2021).

25 Paulina Bressel and Elke Greifeneder, “Nutzerstudie zur Evaluierung der Funktionalitäten und Ansicht des Handschriftenportals (HSP)” (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, GER, 2023).

26 Elke Greifender and Paulina Bressel, “Studie zur Websitestruktur von ‘Germanistik im Netz (GiN)’ - Portal des Fachinformationsdienstes Germanistik” (Universitätsbibliothek Johann Christian Senckenberg, Frankfurt am Main, GER, 2021).

27 Paulina Bressel and Elke Greifeneder, “Studie zur Evaluierung der Websitestruktur und den zentralen Informationsangeboten des Fachinformationsdienstes ‘Allgemeine und Vergleichende Literaturwissenschaft (FID AVL)’: Ergebnisbericht” (Universitätsbibliothek Johann Christian Senckenberg, Frankfurt am Main, GER, 2022).

28 Paulina Bressel, Kirsten Schlebbe, Elke Greifeneder, Franziska Voß, and Julia Beck, “Ergebnisbericht zur qualitativen Evaluierung des Portals des Fachinformationsdienstes Darstellende Kunst” (Universitätsbibliothek Johann Christian Senckenberg, Frankfurt am Main, GER, 2023).

29 Elke Greifeneder and Paulina Bressel, “Hybrid Digital Card Sorting: New Research Technique or Mere Variant?” in Information for a Better World: Shaping the Global Future. iConference 2022. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 13193 (Springer, Cham, 2022), 50–67.

30 Kailaash Balachandran, “kardSort,” (Paderborn, Germany: Kailaash Balachandran, 2021).

31 “OptimalSort, “(Wellington, NZ: Optimal Workshop, 2021).

32 Cornelia Helfferich, “Leitfaden- und Experteninterviews,” in Handbuch Methoden der Empirischen Sozialforschung, ed. Nina Baur and Jörg Blasius, 2nd ed. (Wiesbaden, GER: Springer VS, 2019), 669–86.

33 Covi and Kling, “Organisational Dimensions of Effective Digital Library Use”; Nicholas et al., “Diversity in the E-Journal Use and Information-Seeking Behaviour of UK Researchers”; Arshad and Ameen, “Comparative Analysis of Academic Scientists, Social Scientists and Humanists’ Scholarly Information Seeking Habits.”

34 Ann Blandford, Hanna Stelmaszewska, and Nick Bryan-Kinns, “Use of Multiple Digital Libraries: A Case Study,” Proceedings of First ACM/IEEE-CS Joint Conference on Digital Libraries, no. 1 (2001): 179–88.