ABSTRACT

The article explores the longitudinal relationship between subjective and objective deprivation in early adolescence on the one hand, and criminal offending in adolescence and early adulthood on the other. Data from the Stockholm Birth Cohort Study (n = 15,117), containing information from surveys and registers are used. Bivariate analyses confirm a relationship between low socioeconomic status and both subjective and objective deprivation. Subjective deprivation alone is related to offending only for those from less privileged background. Subjective and objective deprivation in combination is associated with a higher risk of offending for all individuals, although the less privileged background, the higher the risk.

Introduction

Over recent years, criminology has witnessed a growing interest in the significance of perceived future prospects for the risk of offending at the individual level (Brezina, Tekin, and Topalli Citation2009; Clinkinbeard Citation2014; Piquero Citation2016; Silver and Ulmer Citation2012). Young people who report low expectations for the future also tend to report higher levels of criminal involvement. For example, Piquero (Citation2016) shows that among youth offenders the “perceived age at death” is related to offending. According to the offenders interviewed by Brezina, Tekin, and Topalli (Citation2009), the connection between self-reported future prospects and offending can be understood in terms of a “here and now” orientation and of a lack of fear, linked to an experience of blocked life chances. These mechanisms are all well-known from the traditional pool of criminological theories.

However, there often exists a methodological problem in connecting the fatalistic views that some juvenile offenders have on their future with levels of criminal offending. Obviously, the reason why some individuals have low future expectations could be precisely because they have been identified as criminals by the authorities. Thus, it is of vital importance to distinguish between how children and adolescents perceive their future before onset of criminal involvement, and how life actually turns out later on.

It is also the case that the majority of research in the area has been inspired by psychosocial explanatory models, while the role of structural factors for the shaping of future prospects has been largely ignored. In order to bring the structural level into the understanding of future expectations and their significance for offending, we argue that inspiration can be found in elements of Merton’s classic strain theory (Merton Citation1938, Citation1968), primarily in the tendency for individuals from different social strata to share the same life goals, but to differ in (the extent to which they believe in) their capacity to reach these goals. Put somewhat differently, by use of key elements from Merton’s theory, in combination with knowledge from recent research on future orientation, the aim of this study is to analyze the importance of future prospects for the risk of being convicted of crime among individuals from different social backgrounds.

We have access to a unique combination of questionnaire- and register data for an entire cohort of boys and girls who grew up in Stockholm, Sweden (n = 15,117). Information on the individuals’ future orientation was collected when they were aged 12–13. In addition, we have information from various registers relating to both childhood conditions and convictions at age 15–30.

Future orientation, crime, and the need for longitudinal information

There are many different ways to approach the issue of how individuals relate to the future, and different labels are sometimes used to refer to the same phenomena. A common umbrella concept, however, is Future Orientation (FO), which may include a focus on a range of different aspects of the ways in which individuals relate to the future. FO may be defined as “… an individual’s thoughts, plans, motivations, hopes and feelings about his or her future” (Stoddard, Zimmerman, and Bauermeister Citation2011:239; see also; Trommsdorff Citation1983; Nurmi Citation1991). The FO-concept can thus be said to include a cognitive, a motivational, and an affective dimension (Chen and Vazsonyi Citation2011), and perceived future prospects, which constitute the focus of this article, can be viewed as one part of the broader FO-concept.

A link between negative perceptions of future prospects and crime has been reported in several recent criminological studies (see e.g., Clinkinbeard Citation2014; Clinkinbeard and Zohra Citation2012; Piquero Citation2016). This connection appears reasonable on the basis of a number of criminological theories (Silver and Ulmer Citation2012). For example, if individuals do not harbor hopes for the future, they have less reason to worry about the possible consequences of punishment. On the basis of labeling theory, the experience of negative future prospects should not primarily be seen as being related to primary deviation, but rather to secondary deviation. It is possible that it is only when an individual has been detected and labeled as deviant that s/he will perceive the personal future prospects to have worsened. This “chicken or egg dilemma” was identified by Nurmi already some 25 years ago (Nurmi Citation1991). More recently, Brezina, Tekin, and Topalli (Citation2009) and Piquero (Citation2016) have also noted that many of the existing studies examine future prospects and crime at one and the same point in time, which means that the observed differences may be consequences rather than causes of deviant behavior.

There are, however, studies that have had access to longitudinal data on perceived future prospects and crime later on in life. Chen and Vazsonyi (Citation2011) found a negative correlation between pupils’ (followed over a period of 7 years) future prospects and an index based on different types of “problem behaviors”, which included crime. Brezina, Tekin, and Topalli (Citation2009) and Piquero (Citation2016) have both used what may be regarded as the most extreme measure of negative expectations about the future, namely anticipated early death. Brezina, Tekin, and Topalli (Citation2009) combined quantitative data from a large representative sample of youth with interviews conducted among active offenders. The follow-up of the population sample one year subsequent to the first data collection showed a clear correlation between anticipated early death and offending. The young offenders’ narratives showed in turn that negative perceptions of future prospects tended to promote a disregard for the future consequences of one’s actions, a focus on immediate rewards, the development of a here-and-now orientation, and an attraction to risky behavior. Piquero (Citation2016) found a similar correlation in a study based on a considerably longer follow-up period (7 years). In contrast to the study of Brezina, Tekin, and Topalli (Citation2009) however, Piquero’s sample only included “serious youthful offenders” from two American cities. The study was therefore unable to show whether a variation in future expectations had also preceded involvement in crime leading to institutionalization.

A further limitation of the existing literature, which has also been noted by Brezina, Tekin, and Topalli (Citation2009), is that studies have rarely examined the question of the underlying causes of variations in perceived future prospects and blocked life chances. Why is it that some young people look more brightly at the future than others?

Shared goals, blocked life chances, and crime

One of the social science’s most stable findings over both time and geographical location is a clear correlation between resource deficiencies in childhood and subsequent living conditions, included offending (Alm Citation2011; Bäckman and Nilsson Citation2011; Sobolewski and Amato Citation2005; Wagmiller et al. Citation2006).

As is well known, according to Merton (Citation1938, Citation1968)), the roots of this excess risk should not be sought in individual characteristics, but rather in social structures. While conceptions of what constitutes a good life are similar for people from different social strata, the opportunities to achieve these goals are not. Messner and Rosenfeld (Citation2001:53) present a succinct summary of the fundamental conflict involved – “Culture promises what social structure cannot deliver – success, for all”. According to Merton this conflict creates frustration/strain. Given that access to the means is socially stratified, while the goals are universal, the distribution of strain within the population at large will also be socio-economically stratified.

Merton (Citation1968) further argued that the frustration experienced as a result of blocked life chances for some led them to commit crime in order to reduce strain, thus using alternative means to reach the desired goals.

We would argue that on the basis of Merton’s theory, it is not entirely clear whether the frustration that produces an excess risk for crime should be viewed as being objectively produced, in terms of the level of access to resources, or whether it is the subjective experience of blocked life chances that should be viewed as the central factor. As has been noted by Agnew and Jones (Citation1988:316), for example, strain theory has difficulty explaining “why many objectively deprived individuals with high aspirations are not frustrated or strained”. According to Agnew and Jones, this may in part be explained by individuals reacting to worse conditions by reducing their levels of aspiration (in order to thereby avoid frustration resulting from the conflict between goals and means). They argue further that another, less well-known strategy, is for individuals to raise their expectations to inflated levels, and hence report better (exaggerated) future prospects than might be expected on the basis of objective conditions. The consequence of this is that a relatively large proportion of those with low levels of the objective means for achieving desired goals avoid reporting the experience of strain when they are asked about their future prospects. Since the future prospects of this group are objectively speaking worse than those of others, however, they will nonetheless be at greater risk of failing to achieve their stated goals. Over the longer term, then, this adaptive strategy involves a risk of producing experiences of frustration and thus also an excess risk for offending.

In a study based on the same date as that used here, Halleröd (Citation2011) examined on the one hand the extent to which young people’s future prospects were linked to their childhood conditions, and on the other the extent to which their perceived prospects corresponded with the way their lives later turned out. The results showed that children who subjectively assessed their future prospects to be “worse than the majority of others of their own age” were at higher risk as adults of finding themselves outside the labor market, on long-term sick leave, or even to have died. Another interesting finding was that there was a group who exaggerated their future prospects as measured by their grade scores. In line with the ideas of Agnew and Jones (Citation1988), these objectively deprived individuals also experienced worse outcomes in adulthood in terms of work and health.

On basis of the above, we would suggest that an analysis of this criminogenic conflict between goals and means benefits from a focus on both individuals’ subjective perceptions of their future prospects and their more objective opportunities to achieve specified goals. If we follow Agnew and Jones (Citation1988), individuals who are disadvantaged in these two respects may be said to be experiencing subjective and objective deprivation respectively.

Future prospects and crime: implications for the current study

The empirical part of this study will, in a first step, investigate the assumption of a consensus on future goals, in terms of work and material wealth that is shared by a majority of the population, irrespective of their childhood conditions. We will also analyze the extent to which the opportunities to actually realize these goals vary between individuals on the basis of their childhood conditions. The discrepancy between goals and means will be labeled deprivation. In addition to measuring subjective deprivation, i.e., a less optimistic future orientation, we will include in the analysis a measure of objective deprivation, in the form of the children’s grade scores in year six. Previous research has repeatedly shown there to be a clear relationship between school results and future life chances (Bäckman and Nilsson Citation2011). It is important to note that both these measures are studied in early adolescence and before we begin to follow up the convictions of the cohort.

In a next step we will investigate whether those who subjectively experience deprivation, i.e., those with less optimistic self-reported future prospects, and those whose means of achieving their goals are poor as a result of objective conditions, will be significantly over-represented on the different crime dimensions examined in the study. While it is given according to Merton’s (Citation1938, Citation1968) classic strain theory that the prevalence of strain varies on the basis of childhood conditions, it is less clear whether the link between strain and offending is similar across different social classes (see e.g., Farnworth and Leiber Citation1989). This study will examine the interaction between SES/future prospects and crime. Nor is it clear whether the excess risk for crime is general or more specific to certain types of crime, or what should be expected with regard to prevalence vs. incidence. Since we are able to follow registered crime for a relatively long period (between ages 15 and 30), we also have the opportunity to examine whether these correlations are stronger during a certain phase of life.

While the data employed in this study provide opportunities for unique analyses, it should be noted that they are socio-historical to some extent, since the study subjects were born in Sweden during the 1950s and the data on future orientation were collected in the 1960s. As regards the gender aspect, paid work was still not as self-evident an ingredient of adult life for girls as for boys at this time and we may therefore expect the level of commitment to established life goals to be somewhat lower among girls (Alm Citation2015; Axelsson Citation1992). We also know that there are significant gender-based differences in levels of registered crime, both in the cohort examined in this study and in later cohorts, despite the trend toward increased gender equality over recent decades (Estrada, Bäckman, and Nilsson Citation2016). As a result of this, we conduct separate analyses for boys and girls.

The development of the welfare state, not least in the Scandinavian countries, involved the formulation of policies with the clear objective of redressing differences in life chances between different social groups (e.g., Breen and Jonsson Citation2007). Inequalities in childhood conditions were not to be perpetuated across generations (Bäckman et al. Citation2014). Thus, in an international perspective, the level of income inequality has been relatively low in Sweden (Atkinson Citation2015). The decades in which our cohort members grew up were characterized by powerful economic growth and low levels of unemployment. This means that the likelihood of individuals experiencing a conflict between goals and means can reasonably be said to have been, and to be, lower in a country such as Sweden than in, for example, the USA (see Baumer and Gustafson Citation2007; Messner and Rosenfeld Citation2001). At the same time, there are a number of studies based on Scandinavian data showing that inequalities in life chances are linked to involvement in crime also in these countries (Aaltonen, Kivivuori, and Martikainen Citation2011; Bäckman and Nilsson Citation2011). We would therefore argue that the difference between Sweden and other, more unequal countries, is likely to be primarily in degree rather than in kind.

Data and operationalizations

Data

The Stockholm Birth Cohort Study (SBC) is a longitudinal database created by combining two anonymized data sets: the Project Metropolitan Study and the Health, Illness, Income and Employment database (HSIA) (Stenberg and Vågerö 2006; Stenberg et al. Citation2007). The current study only employs data from the Project Metropolitan Study (n = 15,117). This part of the database comprises all individuals born in 1953 who were living in Greater Stockholm ten years later, and includes a large amount of survey and register-based data relating to both the individuals in the cohort and their parents (Janson Citation1995). The register data include information on among other things the parents’ socioeconomic group and income, and on the cohort members’ grades and registered criminality. In 1966, when the cohort members were in the sixth grade (12–13 years old), a school survey was conducted in the form of two questionnaires which focused, among other things, on questions regarding peers, attitudes to school, and plans for the future. A total of 13,476 of the 15,117 individuals in the cohort participated in the school survey.Footnote1

The data on involvement in crime are drawn from the police’s National Crime Register (NCR).Footnote2 This register contains information on offences that have resulted in a conviction. The NCR data cover the period 1968–1984 (i.e., when the cohort members were aged 15–30) and contain annual information on both the number and type of offences committed (for a more detailed description of the cohort members’ involvement in crime, see Nilsson and Estrada Citation2009).

Operationalizations

The study employs four different outcome measures of the cohort members’ registered crime: (1) Prevalence: the proportion convicted at least once between the ages of 15 and 30. (2) Incidence: the number of convictions per individual up to age 30. (3) Life-stage offending: those never convicted of crime are distinguished from those who were only convicted as youths (at age 15–19), and from those whose first conviction came in adulthood (at age 20–30).Footnote3 (4) Offence type: a measure that differentiates between seven different types of crime: theft, fraud, drug offences, violent crime, vandalism, motoring offences, and other offences (see Nilsson and Estrada Citation2009).

The study includes both self-reported and register-based independent variables. Socioeconomic background during childhood is in part measured using a broad indicator based on the socioeconomic status (SES) of the childhood family, and in part using a measure of economic problems in the childhood family. SES is measured on the basis of the parents’ occupation in 1966, i.e., when the cohort members were aged 13. If the child was living with both parents, the SES measure is based on the parent from the highest SES group. The variable has five categories: (1) upper class and upper middle class, (2) lower middle class and self-employed, (3) skilled blue-collar, (4) unskilled blue-collar, (5) unclassified.Footnote4 Economic problems in the childhood family is measured based on whether the cohort member’s family was in receipt of social welfare benefits. Those who received no social welfare payments are distinguished from those who received such benefits over the course of: (1) a maximum of 3 years and (2) more than 3 years.

From classic strain theory we pick the idea of the relevance of cohort members’ self-reported commitment to established life goals (in combination with their means to fulfill these goals). Commitment to established life goals at age 12–13 is estimated with the question: “Do you think that what you’re going to be when you grow up is important, or doesn’t it matter?” The question has five response categories: (1) Very important, (2) Fairly important, (3) Neither important nor unimportant, (4) Doesn’t matter much, (5) Doesn’t matter at all. The individuals who answered that what they were going to be when they grew up was “very” or “fairly” important are viewed as agreeing with the idea that a good job constitutes a central life goal.Footnote5

Self-reported future prospects are measured using the question: “If you compare your future prospects with those of most other people of your age, do you think that yours are worse, as good, or better?” The question has five response categories: (1) Much worse, (2) A bit worse, (3) As good, (4) A bit better, (5) Much better. Individuals who answered “much worse” or “a bit worse” are viewed as perceiving themselves to have limited means available to them for achieving central life goals.Footnote6

Objective future prospects for achieving life goals are measured using grade scores in year six, when the cohort members were aged 12.Footnote7 Individuals with a grade average of below 2.5 (on a five category scale) are regarded as having low grades, and have been coded 1, the others have been coded zero. Just under one-fifth of the cohort members (18.6%) had low grades, based on this measure, and are regarded as having objectively worse future prospects.

Among those individuals who stated that what they would be when they grew up was fairly or very important, we distinguish: (1) Non-deprived. (2) Subjectively deprived; individuals who share society’s goals, but estimate their future prospects to be relatively poor. (3) Objectively deprived; individuals who share society’s goals, and estimate their future prospects to be good, but whose objective future prospects are restricted as a result of poor grades. (4) Subjectively and objectively deprived; individuals who share society’s goals, but have poor future prospects on the basis of both subjective and objective criteria.

In order to examine whether the relationship between deprivation and crime differs by childhood conditions, interaction terms have been created for SES and the deprivation measure. To limit the number of categories for the interaction variable, some of the SES categories have been combined to produce a three-category variable: (1) Upper class and upper middle class, (2) Lower middle class and self-employed, and (3) Skilled and unskilled blue collar, and unclassified. Since we wish to compare the relationship between having less positive future prospects at age 13 and convictions at age 15–30 for groups from different childhood conditions, we use the positive future prospects category (i.e., neither subjective nor objective deprivation) for all individuals irrespective of SES as the reference group. This gives us a total of nine interaction variables which combine the three SES categories with (1) subjective deprivation, (2) objective deprivation, and (3) subjective and objective deprivation.

The analysis employs both bivariate and multivariate (logistic regression) methods.

Results

First below are presented the results of the bivariate analyses of the link between SES background and future prospects on the one hand, and between future prospects and criminal offending on the other. After this follows the results from the logistic regression models.

Future goals and future prospects in a birth cohort

A very substantial majority of the cohort members, 88% of the 12–13-year-old boys, and 86% of the girls, stated that what they would be when they grew up was “very important” or “fairly important” (not shown in table). Similarly, a large majority of the youths in the study, irrespective of gender, stated that their prospects of achieving these future goals were as good as those of most other people. Although one may perhaps have opinions about the degree to which these measures would have been approved of by Merton himself, for our current purpose we interpret this as an absence of a conflict between goals and self-reported means for the majority of the cohort members.

Among those who feel that it is important what they will become as adults, approximately one tenth of the boys and one twentieth of the girls, however, perceive that their prospects of achieving these goals were worse than those of their peers. Although there is a somewhat larger proportion of boys in this group, the gender differences are small. If we instead shift the focus to socioeconomic factors, the differences are clearer, and they are also in the expected direction (). Members of the two groups that contain young people who perceive themselves to have worse future prospects are considerably more often drawn from homes with more sparse economic resources. This is the case in relation to both the broad measure of socioeconomic class (SES) and our more restrictive measure of economic problems during childhood (social welfare recipiency). The pattern is the same for both genders.

Table 1. Future goals combined with future prospects by socioeconomic background. Adolescents aged 12–13. NB: Row percentages.

In we include our “objective” measure of negative future prospects, i.e., poor grades in year six, and thus distinguish the three categories of individuals on whom we will be focusing our analysis of subsequent involvement in crime: (1) the subjectively deprived, (2) the objectively deprived, (3) the subjectively and objectively deprived. The proportion of boys who are objectively deprived is larger than the corresponding proportion of girls (). It should be remembered that the youths in this group perceive their future prospects to be as good as, or better, than those of their peers. The smallest of the three groups we will be studying is that comprised of those classified as both objectively and subjectively deprived. Here the proportion of boys is twice as large as the corresponding proportion of girls.

Table 2. Subjective and objective deprivation by socioeconomic background. Adolescents aged 12–13. NB: Row percentages.

Looking to how the risk for subjective and objective deprivation are distributed on the basis of social background, we find that the risk of experiencing only subjective deprivation is greatest for those who come from homes where the parents are either unskilled blue-collar workers or from an unclassified occupational background, although with respect to this experience neither the relative nor the absolute differences between individuals from different social backgrounds are particularly large (irrespective of gender). Looking instead to the risk of being objectively deprived (poor grades) or of experiencing both subjective and objective deprivation simultaneously, we can see much greater such differences. The question is, what does the subsequent criminality of these groups look like, both in relation to one another and in relation to the remainder of the cohort members?

Future prospects and crime

After the cohort members had been interviewed at age 12–13 on their expectations regarding the future, they were followed up into adulthood. The risk of being convicted at some point between the ages of 15 and 30 was considerably greater among those who had experienced a conflict between goals and means at age 12–13 (see ). The level of convictions is much lower among the women, but the general pattern is the same. The fact that relatively few women were convicted means however that the results are less unequivocal than those for the men, which is particularly true when the focus is directed at convictions for specific types of offending.

Table 3. Subjective and objective deprivation (at age 12–13) and criminal convictions (at age 15–30). Men and women. Column percentages.

Given that the conflict between goals and means has been measured at a young age, it is interesting to note that the excess risk for a conviction among those who have experienced this conflict is more marked during the teenage years. Of the men in the non-deprived group, for example, 13.7% were convicted at age 15–19 and 10.4% subsequent to the age of 20. The corresponding proportions among those who experienced both subjective and objective deprivation were 38.2% for a conviction in youth and 15.4% in adulthood. This pattern is also found among the women. One difference, however, is that the proportion of convicted women whose first conviction comes in adulthood is greater.

The results regarding convictions for different types of crime indicate that the significance of subjective and objective deprivation is not limited to specific offence types, but is a general pattern. Finally, for those convicted of offences, we have also studied the frequency of convictions. Here the findings of the analysis focused on women are unfortunately somewhat uncertain due to the small number of convictions registered in a number of the groups. Among the men, however, it is clear that the incidence of convictions is considerably greater in the groups that experienced subjective or objective deprivation.

Social background, future prospects and crime – results from multivariate analyses

The analysis now moves on to use logistic regression models to examine whether the effects of the goals/means conflict on the likelihood of being convicted remain when we control for childhood conditions (SES and economic problems respectively). In addition, we are also interested in examining whether having poor future prospects, in subjective and objective terms respectively, are of similar importance for the conviction risk among young people from different social backgrounds. Since we have shown above that the relationship can be seen irrespective of which measure of crime is chosen, we will be analyzing the general risk of being convicted (prevalence at age 15–30). The relatively low levels of convictions among women mean that the estimates become more uncertain when we include several different factors in the analysis. For the purposes of our multivariate analysis, we have therefore chosen to focus exclusively on the men.

In Model 1, the reference category comprises those who share the established societal goals and who, on the basis of the study’s indicators, were not experiencing either subjective or objective deprivation (). In principle, this model replicates the results we have presented above. The highest level of excess risk for a conviction is found among those men who at age 12–13 both had poor grades and perceived themselves as having worse prospects of achieving the desired goals. Models 2 and 3 focus on the different indicators of resources in the childhood family, and these too, as expected, are found to be significantly correlated with the risk of conviction.

Table 4. Results from logistic regression analyses of the risk of being convicted of crime at age 15–30. Boys/men. Odds ratios.

Finally, in Models 4 and 5 we see how the significance of both social background and future prospects are affected when they are included in the analysis at the same time. We can note that all correlations remain significant, which means that all of the factors examined have an independent effect on the risk for a future conviction for crime. Thus with regard to SES, each of the groups examined is at greater risk of conviction than the reference category (upper class and upper middle class), but the less privileged the group’s position, the greater the level of excess risk. Shifting the focus to economic problems, those from families in receipt of social welfare are at significantly greater risk of being convicted of crime. Further, if we compare the significance of the different dimensions of poor future prospects, there is a tendency for objective deprivation to be more strongly linked to future crime than the individuals’ subjective perceptions of having poor prospects for the future. It can be noted, however, that even those who have experienced subjective deprivation are at significantly greater risk of being convicted of crime, following the inclusion of controls for differences in social background. The highest level of excess risk (by a factor of just over three) is found among those who experienced both subjective and objective deprivation.

Although both future prospects and our different measures of childhood resources each contribute to explaining the risk for conviction, it can also be seen that the effects of SES and economic problems become weaker when they are included in the model together with the measures of future prospects. This indicates that the effect of socioeconomic background is in part mediated via the individuals’ subjectively experienced and objective future prospects. Models 4 and 5 also show that the effect of SES on crime appears to be affected to a varying extent across different SES categories when the future prospect measures are included in the model.

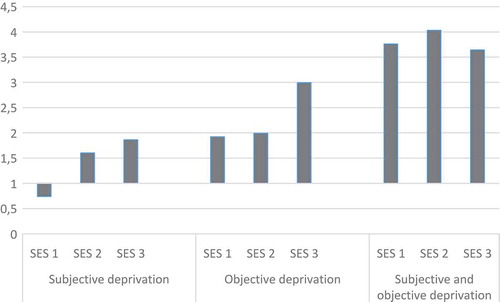

In order to examine this finding in more detail, a concluding analysis was conducted, which employed interaction terms based on SES and future prospects. All those with positive future prospects (i.e., those who experienced neither subjective nor objective deprivation), irrespective of SES, were used as the reference category. This gave us a total of nine interaction variables, which combine the three SES categories with subjective deprivation, with objective deprivation, or with both subjective and objective deprivation. The odds ratios for each of these, in relation to the reference category, are presented in below (the model, including significance levels, is presented in in the appendix).

Figure 1. Results from logistic regression analysis of the risk of being convicted of offences at age 15–30 among men. Odds ratios for interaction variables with the reference category “neither subjective nor objective deprivation”, ”SES1-SES3”.

The interaction analysis shows that the significance of poor future prospects for subsequent criminality differs somewhat between young men from different social groups. Firstly, the experience of subjective deprivation is not linked to a higher risk of subsequent conviction for those of upper class and upper middle class background (SES 1). Thus, this conflict between goals and perceived means only produces a significant excess risk for future crime among those from lower middle class and blue-collar homes. Objective deprivation, i.e., poor grades, on the other hand, is linked to an excess risk for conviction irrespective of SES. Here too, however, the risk is linked to social class background in the sense that young people from blue-collar homes are at considerably higher risk of being convicted compared to young people from middle- and upper-class homes who also have poor grades. It is thus only among those who both have poor grades and who perceive their prospects to be “worse than the majority of others” that social class background does not appear to matter for the risk of being convicted of crime. Naturally, the risk of finding oneself in this category varies on the basis of childhood conditions (and there are very few young men from upper class and upper middle class homes in this group), but given that an individual experiences both subjective and objective deprivation, growing up in more privileged conditions provides no protection against becoming involved in crime.

Concluding discussion

Over recent years, a number of interesting studies have focused attention on the significance of individuals’ perceived future prospects for the risk of committing offences (see e.g., Brezina, Tekin, and Topalli Citation2009; Clinkinbeard Citation2014; Piquero Citation2016; Silver and Ulmer Citation2012). The results from these studies show a clear link between criminality and having negative perceptions about one’s future. One recurrent problem in the research literature, however, is that the studies are either based on cross-sectional data, which makes it difficult to specify the causal order, or on selective samples of individuals who have already been involved in crime. In addition, the issue of the structural underpinnings of future prospects has not been studied sufficiently. Here we would argue that there are clear benefits to be had from returning to Merton’s classic formulation of strain theory and to the idea that the higher levels of offending found among working class youth are linked to their relative lack of opportunities to achieve desired future goals.

As a result of our access to a unique longitudinal data set containing information on the future orientation of an entire birth cohort, as well as register data on social background, grades, and crime, we have been able to study how young people’s future prospects are associated with criminality later on in life.

One requirement for the occurrence of strain is that individuals share the same goals for the future, but perceive themselves as lacking similar future prospects. Moreover, strain theory is intimately associated with the inequality of access to the “American Dream” (Messner and Rosenfeld Citation2001). Swedish society, not the least during the decades in which the Stockholm cohort that we analyze grew up, has been characterized by a much greater degree of equality in life chances. In spite of this, we find that those young people who share the same goals as the majority, but who at the same time perceive themselves as having worse future prospects than others, are considerably more often found to have a less privileged class background.

Moreover, we also find that these subjectively deprived youths are more often convicted of crime later in life. The excess risk is found in relation to a range of different types of offences and for both prevalence and incidence. This pattern supports the assumption that the mechanisms of classic strain theory are of general significance for crime and are not only associated with utilitarian delinquency for example.

The finding that women commit considerably fewer offences than men is one of the most robust in criminology. In the current study, this meant that there were too few convicted women to allow for multivariate analysis, and this analysis was therefore restricted to the men. This is a of course a limitation. Nonetheless, the initial bivariate analyses indicated substantial cross-gender similarities in the sense that both strain and having objectively worse opportunities to achieve desired goals also appeared to be associated with a higher risk for conviction among the women. In exactly the same way as among the men, the same tendency was found in relation to the majority of offence types.

Perhaps the study’s most interesting finding is that the analysis of the interaction between class background, subjective deprivation, and crime showed that young men experiencing a conflict between goals and means and who grew up in socioeconomically privileged homes were not at higher risk of being convicted of crime. Thus it is only among young people from lower middle and blue-collar backgrounds that subjective deprivation appears to be linked to crime. In these groups the risk of being convicted was almost twice as large as among those who experienced neither subjective nor objective deprivation. We have not examined what it is that protects the socioeconomically privileged youths who reported having poor future prospects from an excess risk of future convictions, but it appears that high levels of socioeconomic resources may have a cushioning effect. At the same time, however, we note that this protective effect is no longer enjoyed if the upper or upper middle class individuals have received poor grades in year six. The presence of this objective measure of poor future prospects is de facto also more clearly linked to criminality than the experience of subjective deprivation alone, irrespective of class background. Here too, however, we find an interaction effect, to the disadvantage of those from less privileged socioeconomic backgrounds; it is only for those youths who experience both subjectively and objectively poor future prospects that class background no longer has an influence on future involvement in crime. Among these young people, the level of excess risk is substantial, at a factor of almost four times that of those who experienced neither subjective nor objective deprivation, and this is thus the case irrespective of class background.

Over recent decades, Sweden, as well as other Western countries, has witnessed a trend toward increasing levels of income inequality (Atkinson Citation2015). This trend suggests that the study’s findings are becoming increasingly relevant. A study by Wiborg and Hansen (Citation2009), which investigates the intergenerational transmission of social disadvantage in Norwegian birth cohorts born between 1955 and 1985, points in the same direction. Wiborg and Hansen show that the significance of social origin has not declined for younger cohorts. On the contrary, their findings indicate a stable, and even slightly increasing, impact of the parents’ economic resources. The likelihood of youths, and not least those from poorly resourced homes, experiencing blocked life chances has thus rather increased than decreased since the Stockholm cohort grew up. The substantial excess risk for future convictions found among those who share the life goals of the majority, but who perceive their own chances of achieving these goals to be poor, and whose chances of achieving them are also objectively restricted, therefore constitutes this study’s most important finding. We would welcome studies based on younger cohorts, investigating whether this basic pattern tends to persist among the young of today.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the Swedish Research Council [2011-2206] is gratefully acknowledged.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Susanne Alm

SUSANNE ALM: She is an Associate Professor of sociology at the Swedish Institute for Social Research, Stockholm University, Sweden. Her research is primarily concerned with the relationship between childhood living conditions and various aspects of social exclusion and social problems in adulthood, such as criminal offending, drug abuse, poverty, and eviction. She also does research on future orientation among the young, on adolescent psychological health and on youth culture.

Felipe Estrada

FELIPE ESTRADA: He is a Professor of Criminology at Stockholm University, Sweden. His main research areas are life-course criminology, crime trends, life chances, and social exclusion.

Notes

1 Of the remaining 1641 individuals, 288 had left the cohort (i.e., they had either moved out of the Stockholm Metropolitan area or had died). The remaining 1353 individuals were still in the cohort but did not participate in the School Survey.

2 Person- och belastningsregistret (PBR).

3 198 of the total of 15,117 cohort members died between the ages of 15 and 30. This proportion is small enough not to affect the patterns identified in the study as a whole.

4 For just over 400 individuals, SES could not be specified. These include individuals whose guardians had no stable labor market attachment, and the group as a whole is characterized by low levels of resources.

5 Data was missing for 134 individuals.

6 Data was missing for 283 individuals.

7 In cases with missing data, grade scores for year nine were employed. This was the case for 280 individuals. For 646 individuals, data were missing in both year six and year nine.

References

- Aaltonen, Mikko, Janne Kivivuori, and Pekka Martikainen. 2011. “Social Determinants of Crime in a Welfare State: Do They Still Matter?.” Acta Sociologica 54(2):161–81. doi:10.1177/0001699311402228.

- Agnew, Robert and Diane H. Jones. 1988. “Adapting to Deprivation: An Examination of Inflated Educational Expectations.” The Sociological Quarterly 29(2):315–37. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.1988.tb01256.x.

- Alm, Susanne. 2011. “The Worried, the Competitive and the Indifferent: Approaches to the Future in Youth, Their Structural Roots and Outcomes in Adult Life.” Futures 43(5):252–62. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2011.01.012.

- Alm, Susanne. 2015. “Dreams Meeting Reality? A Gendered Perspective on the Relationship between Occupational Preferences in Early Adolescence and Actual Occupation in Adulthood.” Journal of Youth Studies 18(7–8):1077–95. doi:10.1080/13676261.2015.1020928.

- Atkinson, Anthony B. 2015. Inequality: What Can Be Done?. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Axelsson, Christina. 1992. “Hemmafrun som försvann”. [The housewife that disappeared] Dissertation series, no. 21, Swedish Institute for Social Research, Stockholm University, Stockholm.

- Bäckman, Olof, Felipe Estrada, Anders Nilsson, and David Shannon. 2014. “The Life Course of Young Male and Female Offenders: Stability or Change between Different Birth Cohorts?.” British Journal of Criminology 54(3):393–410. doi:10.1093/bjc/azu007.

- Bäckman, Olof and Anders Nilsson. 2011. “Pathways to Social Exclusion – A Life-Course Study.” European Sociological Review 27(1):107–23. doi:10.1093/esr/jcp064.

- Baumer, Eric P. and Regan Gustafson. 2007. “Social Organization and Instrumental Crime: Assessing the Empirical Validity of Classic and Contemporary Anomie Theories.” Criminology 45(3):617–63. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2007.00090.x.

- Breen, Richard and Jan O. Jonsson. 2007. “Explaining Change in Social Fluidity: Educational Equalization and Educational Expansion in Twentieth-Century Sweden.” American Journal of Sociology 112(6):1775–810. doi:10.1086/508790.

- Brezina, Timothy, Erdal Tekin, and Volkan Topalli. 2009. “‘Might Not Be A Tomorrow’: A Multimethods Approach to Anticipated Early Death and Youth Crime.” Criminology 47(4):1091–129. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2009.00170.x.

- Chen, Pan and Alexander T. Vazsonyi. 2011. “Future Orientation, Impulsivity, and Problem Behaviors: A Longitudinal Moderation Model.” Developmental Psychology 4(6):1633–45. doi:10.1037/a0025327.

- Clinkinbeard, Samantha S. 2014. “What Lies Ahead: An Exploration of Future Orientation, Self-Control, and Delinquency.” Criminal Justice Review 39: 9–36. doi:10.1177/0734016813501193.

- Clinkinbeard, Samantha S. and Tusty Zohra. 2012. “Expectations, Fears, and Strategies: Juvenile Offender Thoughts on a Future outside of Incarceration.” Youth & Society 44: 236–57. doi:10.1177/0044118X11398365.

- Estrada, Felipe, Olof Bäckman, and Anders Nilsson. 2016. “The Darker Side of Equality? the Declining Gender Gap in Crime: Historical Trends and an Enhanced Analysis of Staggered Birth Cohorts.” British Journal of Criminology 56(6):1272–90. doi:10.1093/bjc/azv114.

- Farnworth, Margaret and Michael J. Leiber. 1989. “Strain Theory Revisited: Economic Goals, Educational Means, and Delinquency.” American Sociological Review 54(2):263–74. doi:10.2307/2095794.

- Halleröd, Björn. 2011. “What Do Children Know about Their Futures: Do Children’s Expectations Predict Outcomes in Middle Age?” Social Forces 90(1):65–83. doi:10.1093/sf/90.1.65.

- Janson, Carl-Gunnar. 1995. On Project Metropolitan and the Longitudinal Perspective. Research Report No. 40. Stockholm: Department of Sociology, Stockholm University.

- Merton, Robert K. 1938. “Social Structure and Anomie.” American Sociological Review 3: 672–82. doi:10.2307/2084686.

- Merton, Robert K. 1968. Social Theory and Social Structure. Glencoe: Free Press.

- Messner, Steven F. and Richard Rosenfeld. 2001. Crime and the American Dream. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Nilsson, Anders and Felipe Estrada. 2009. Criminality and Life Chances. Department of Criminology, Report no. 2009:3. Stockholm: Department of Criminology, Stockholm University.

- Nurmi, Jari-Erik. 1991. “How Do Adolescents See Their Future? A Review of the Development of Future Orientation and Planning.” Developmental Review 11: 1–59. doi:10.1016/0273-2297(91)90002-6.

- Piquero, Alex R. 2016. “Take My License N’ All that Jive, I Can’t See…35ʹ: Little Hope for the Future Encourages Offending over Time.” Justice Quarterly 33(1):73–99. doi:10.1080/07418825.2014.896396.

- Silver, Eric and Jeffery T. Ulmer. 2012. “Future Selves and Self-Control Motivation.” Deviant Behavior 33(9):699–714. doi:10.1080/01639625.2011.647589.

- Sobolewski, Juliana M. and Paul R. Amato. 2005. “Economic Hardship in the Family of Origin and Children’s Psychological Well-Being in Adulthood.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 67: 141–56. doi:10.1111/j.0022-2445.2005.00011.x.

- Stenberg, Sten-Åke and Vågerö. Denny. 2006. “Cohort Profile: The Stockholm Birth Cohort of 1953.” International Journal of Epidemiology 35(3):546–48. doi:10.1093/ije/dyi310.

- Stenberg, Sten-Åke, Denny Vågerö, Reidar Österman, Emma Arvidsson, Cecilia Von Otter, and Carl-Gunnar Janson. 2007. “Stockholm Birth Cohort Study 1953-2003: A New Tool for Life-Course Studies.” Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 35(1):104–10.

- Stoddard, Sarah A., Marc A. Zimmerman, and José A. Bauermeister. 2011. “Thinking about the Future as A Way to Succeed in the Present: A Longitudinal Study of Future Orientation and Violent Behaviors among African American Youth.” American Journal of Community Psychology 48: 238–46. doi:10.1007/s10464-010-9383-0.

- Trommsdorff, Gisela. 1983. “Future Orientation and Socialization.” International Journal of Psychology 18: 381–406. doi:10.1080/00207598308247489.

- Wagmiller, Robert L., Jr, Mary Clare Lennon, Li Kuang, Philip M. Alberti, and Lawrence L. Aber. 2006. “The Dynamics of Economic Disadvantage and Children’s Life Chances.” American Sociological Review 71(5):847–66. doi:10.1177/000312240607100507.

- Wiborg, Øyvind Nicolay and Marianne Nordli Hansen. 2009. “Change over Time in the Intergenerational Transmission of Social Disadvantage.” European Sociological Review 25(3):379–94. doi:10.1093/esr/jcn055.

Appendix

Table A: Interaction SES and deprivation. Risk for conviction at age 15–30. Boys/men. Odds ratios from logistic regressions.