ABSTRACT

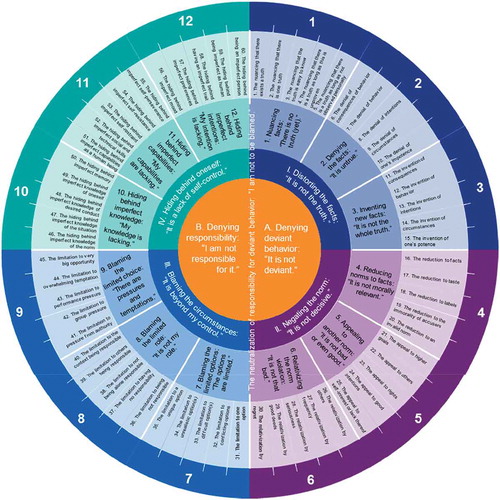

Neutralizations are important explanations for the rise and persistence of deviant behavior. We can find many different and overlapping techniques of neutralizations in the literature, which may be a reason for inconsistent research findings on the use and influence of neutralization techniques. Therefore, by following both a deductive and an inductive approach, this article develops a model that covers these techniques in a logical way. This is a novel approach in studying neutralization techniques. We distinguish four categories of neutralizations: distorting the facts, negating the norm, blaming the circumstances, and hiding behind oneself. Based on a broad inventory of neutralizations that are identified in the literature – something that has not been done before – we operationalized each of the four categories into three techniques, each of which consists of five subtechniques. The resulting model aims to reduce the risk of arbitrariness in the selection of techniques for empirical research and thereby facilitates more consistent future research findings. The model also aims to help better understand how neutralizations work.

Introduction

“I didn’t really hurt anybody,” “They had it coming to them,” and “I didn’t do it for myself” are, as Sykes and Matza (Citation1957) point out, examples of neutralizations. Neutralizations, also called rationalizations, are defined by Maruna and Copes (Citation2005) as justifications and excuses for deviant behavior. Neutralizations have the awkward position of being “universally condemned while being universally used” (Schlenker, Pontari, and Christopher Citation2001:15). They are considered an important or even most important explanation of deviant behavior, such as fraud (Murphy and Dacin Citation2011) and embezzlement (Cressey Citation1950). Neutralizations have thus become one of the most common concepts in the study of deviant behavior (Serviere-Munoz and Mallin Citation2013).

Sykes and Matza (Citation1957) are among the scholars to first study neutralizations. To explain juvenile delinquency, they proposed five major types of neutralization techniques: denial of responsibility, denial of injury, denial of the victim, condemnation of the condemners, and appeal to higher loyalties. These five types of neutralization techniques, also known as the famous five, have been widely used in many different fields (Maruna and Copes Citation2005). At the same time, many other new techniques have been identified (Maruna and Copes Citation2005). Fritsche (Citation2005:485) suggests that because these various techniques “do not offer a theoretically sound taxonomy, nor an exhaustive list”, there is the risk of arbitrariness in selecting which techniques to study for their use and influence. Maruna and Copes (Citation2005) warn that because many techniques overlap, this may be a reason for the inconsistent research findings and may present problems for future researchers.

To address these risks of arbitrariness and inconsistency in the way neutralization techniques are named and selected, this article aims to develop a model that covers the neutralizations that have been presently identified and group these neutralizations into nonoverlapping techniques. This article follows both a deductive and an inductive approach, a method that is new for this subject. We first define a basic model of the categories of neutralizations. We then test and enrich this model by collecting as many examples of neutralizations as possible that are suggested in the academic and professional literature. Such collection has not been done before. By going back and forth between the preliminary model and the collected neutralizations, we will arrive at a model that covers all identified neutralizations. The contribution of this article is a model of neutralizations that is the most comprehensive that can be found at present, one that facilitates less arbitrary and more consistent research findings and helps better understand how neutralizations work. We start with a brief description of neutralization theory.

Neutralization theory

Neutralization theory originated from research on criminology and deviant sociology (Curasi Citation2013). In explaining how white-collar crime is learned, Sutherland (Citation1941) states that rationalization is the primary means by which managers attempt to justify their crimes. In a process of conscious self-discussion, offenders talk themselves into committing the crime by making the crime acceptable. Cressey (Citation1953) found in a study among embezzlers that they rationalized their illegal behaviors through “vocabularies of adjustment” such as they “only borrowed the money.” These verbalizations allowed embezzlers to minimize the apparent conflict between their behavior and the prevailing laws and norms.

Inspired by the work of Sutherland and Cressey, Sykes and Matza (Citation1957) were interested in explaining how juvenile delinquents learn neutralizations. Sykes and Matza preferred to use the term “neutralization” to refer to the justification given before the act instead of the term “rationalization” that refers to the justification given after the act. The basic thesis of their article is that offenders learn techniques of neutralizations so that they can violate the laws and norms that they ordinarily believe in and adhere to. Offenders accept norms but view them as “qualified guides” instead of “categorical imperatives” (Sykes and Matza Citation1957:666). Offenders are said to “neutralize” in advance any disapproval of not following internalized norms because “social controls that serve to check or inhibit deviant motivational patterns are rendered inoperative, and the individual is freed to engage in delinquency without serious damage to his self-image” (p. 667). Thus, the offender can remain “committed to the dominant normative system and yet so qualifies its imperatives that violations are ‘acceptable’ if not ‘right’” (p. 667).

Neutralization theory seeks to explain the paradox of offenders violating norms that they believe in while having seemingly little or no guilt. These offenders protect their self-esteem and neutralize self-blame by employing linguistic devices to convince themselves that it is acceptable in their current situation to engage in behavior that is traditionally considered immoral. Norms are not denounced wholly but are momentarily bracketed so that an offender feels released to transgress them (Hinduja Citation2007). So the contradiction between their behavior that violates a norm and the resulting guilt and shame is neutralized by self-deception (Heath Citation2008). This neutralization of behavior occurs not only following the offense but also prior to it, thus making deviant behavior also possible (Sykes and Matza Citation1957).

According to Maruna and Copes (Citation2005), the most significant stumbling point for neutralization theory has been the difference between neutralizations and rationalizations. For the purpose of this article, we will not make a distinction between these two terms because they are increasingly used interchangeably in the literature, covering both ex ante and ex post arguments (Ashforth and Anand Citation2003; Serviere-Munoz and Mallin Citation2013). Neutralizations and rationalizations are also broadly congruent with some other concepts whose vocabularies are used to bridge the gap between norm and behavior (Ribeaud and Eisner Citation2010). Some widely used overlapping concepts are accounts (Scott and Lyman Citation1968), disclaimers (Hewitt and Stokes Citation1975), and cognitive mechanisms of moral disengagement (Bandura et al. Citation1996). Stokes and Hewitt (Citation1976) introduced the notion of aligning actions as a catchall for the behaviors expressed by these concepts.

Elaborations

Many of the studies on neutralizations use Sykes and Matza (Citation1957) famous five to examine the extent to which neutralizations exist in practice, how they explain and predict deviant behavior, and what their conditions are (Maruna and Copes Citation2005). Given that Sykes and Matza’s list was tentative, as they themselves have acknowledged, many studies have identified other neutralization techniques, such as the metaphor of the ledger (Klockars Citation1974), claim of individuality (Henry and Eaton Citation1999), and “no one cares” (Shigihara Citation2013). The famous five is also not uncontested. For instance, Ashforth and Anand (Citation2003) have proposed replacing the ‘condemnation of the condemners’ technique with social weighting because they consider the former a subset of the latter.

Many different categorizations and typologies of neutralization techniques and related concepts have been proposed as a result of the many different neutralization techniques that have been identified, such as by Scott and Lyman (Citation1968), Schlenker (Citation1980), Benoit and Hanczor (Citation1994), Barriga and Gibbs (Citation1996), Bandura et al. (Citation1996), Robinson and Kraatz (Citation1998), Ashforth and Anand (Citation2003), Gellerman (Citation2003), Geva (Citation2006), Goffman (Citation2009), Murphy and Dacin (Citation2011), Banerjee, Hay, and Greene (Citation2012), and Shigihara (Citation2013). Two typologies that claim to cover most of the techniques are Schönbach’s (Citation1990) and Fritsche’s (Citation2002). Schönbach inductively collected accounts from 120 students who were confronted with vignettes of various failure events. The accounts contained a total of 19 themes and led to the categories of concessions, excuses, justifications, and refusals. Fritsche (Citation2002:376) aimed to deductively develop an integrative metataxonomy of account strategies that “maps the universe” by distinguishing from each other accounts that reject the reproach’s legitimacy (refusal), those that reject one’s own agency (excuse), and those that reject that the behavior contradicts the salient norm (justification). Fritsche’s taxonomy contained a total of 13 techniques. So far, none of the proposed categorizations of neutralization techniques are based on a systematic inventory of already identified techniques for all kinds of deviant behavior. Because of this, we still run the risk of having a limited, arbitrary, and only illustrative overview of techniques of neutralizations.

Toward a model

We used both a deductive and an inductive approach to develop a model that not only covers as many neutralizations as possible but also offers a logical structure.

Deductive approach

We started by deductively devising a basic structure that should help us connect the categories of neutralization techniques to each other in a logical way. The basic structure we used is logical and exhaustive because it is based on the essence of what neutralizations are. Neutralizations for deviant behavior are techniques that help to argue away, fully or partly, someone’s responsibility for the deviant behavior (“I am not to be blamed.”) so that there is no or less guilt. Neutralizing can then be done in two ways: on the one hand, by denying deviant behavior, and on the other, by denying responsibility. By denying deviant behavior, there is no problem at all. By denying responsibility, there is no agency that can be credited with accountability. Using either of these two neutralizations means that there is no (or only less) responsibility for the deviant behavior to speak of because there is deviant behavior but one is not responsible for it, or that one is responsible but for a behavior that is not deviant. Therefore, we have two broad categories of neutralizations for a deviant behavior: denying deviant behavior (“It is not deviant.”) and denying responsibility (“I am not responsible for it.”).

Each of these categories can be further subdivided into two categories. One can deny deviant behavior through (I) distorting the facts (“It is not the truth.”) or through (II) negating the norm (“It is not decisive.”). People can deny deviant behavior by changing the description of the situation so that the norm that is violated is no longer applicable and thus would appear to have not been violated at all. They can also deny deviant behavior by changing the norm so that it is no longer applicable to the situation. Denial of responsibility can be distinguished into (III) blaming the circumstances, where people pass on the responsibility to the situation and aggravating external factors (“It is beyond my control.”) and (IV) hiding behind oneself, where people pass on the responsibility to personal, internal factors and influences, thereby excusing themselves (“It is a lack of self-control.”). These four categories are exclusive and exhaustive in the sense that offenders can tamper either with deviancy (through the facts or norms) or with responsibility (through the external or internal factors.)

These four categories vary in how much room they allow for avoiding the acceptance of guilt and opting for another neutralization. Schönbach (Citation1990) ranks his account categories in order of escalating defensiveness from concessions, to excuses, to justifications, and up to refusals (the most aggravating strategy). We can do the same with our four categories. Denying deviant behavior is safer than denying responsibility in the sense of being less close to concession and having more options open for other neutralizations. When one fails in denying deviant behavior, one still has the option to deny one’s responsibility. However, in trying to deny one’s responsibility, one acknowledges that a norm has been violated because otherwise one does not have to neutralize one’s responsibility. When trying to deny deviant behavior, distorting the facts is safer than negating the norms in the sense that when the facts are different and no or other norms apply, there is no issue at all; thus there is no longer any reason to neutralize one’s behavior by negating the norms (cf. White, Bandura, and Bero Citation2009). However, when one aims to negate the norms, one acknowledges the facts otherwise one would not have to make the norm indecisive. When deviant behavior cannot be denied at all or at least not sufficiently, it is safer to attribute responsibility to the circumstances because if one fails, one can still try to use neutralizations for one’s lack of self-control. However, using neutralizations for a lack of self-control implies an acknowledgement that not all responsibility for the deviant behavior can be passed on to the circumstances (i.e., that one is then partially responsible).

Inductive approach

To operationalize our model, we collected as many examples of neutralizations as possible. The examples are in the form of quotes of neutralizations and similar concepts. We examined the academic and professional literature in the following disciplines: deviance, criminology, (social) psychology, (business) ethics, and management. We used as keywords the different concepts discussed above (e.g., excuses, justifications, and rationalizations) and terms like distortions, illogical arguments, and fallacies. We explored the electronic databases Blackwell Synergy, EBSCO, Google, Google Scholar, ISI Web of Knowledge, JSTOR, ProQuest, ResearchGate, and SSRN. We conducted a manual search of all articles published in the top-tier journals in the abovementioned disciplines. We identified and examined other relevant publications cited within the retrieved publications. We did the literature review independently of each other and merged our findings afterwards. Because we cast our net broadly, we continued with only those neutralizations that are used to justify and excuse deviant behavior. These include immoral, unethical, nonconforming, delinquent, and criminal behavior. After grouping together similar neutralizations, we had a remaining set of 1,251 different neutralizations.

As the next step, we independently plotted each identified example of neutralization into one of our four categories. We discussed and compared the results and agreed on the category allocation of each neutralization. Based on the initial allocations, we then tried to refine the categories. With this iterative process of putting collected neutralizations into a logical, detailed categorization of techniques and testing whether these categories of techniques cover the collected neutralizations in a clear way, we finally came up with three main techniques of neutralizations per category, with each of the three techniques consisting of five subtechniques. This made a total of 60 subtechniques.

The resulting model can be defended on logical grounds. We have arguments for the classification and also for the sequence of the categories and their techniques. It can also be checked whether the model covers all the collected neutralizations and whether the suggested subtechniques are different from each other. We were able to ascribe each collected example of neutralizations to one of the techniques in the model. This suggests that the model covers all neutralizations that have been identified to date. To start testing the discriminant validity of the model, we randomly selected 30 examples of neutralizations and asked 9 academics and practitioners to allocate them to one of the 60 subtechniques that were briefly described to them. In 85% and 93% of the cases the participants attributed the example to the same subtechnique and technique, respectively, as we ourselves proposed. For two of the examples more than one third of the panel members attributed it to another subtechnique. This led us to adjust the relevant technique and its corresponding description.

A model of neutralization techniques

The resulting model is depicted in . The model indicates that the higher the number of a category and its (sub)techniques, the less room there is for people, who fail in using that particular neutralization, to select another (sub)technique before they have to admit their guilt. This is because by using a particular (sub)technique, the person implicitly acknowledges that the subtechniques depicted earlier (i.e., lower number) in the model cannot be used any longer in a logical way. The sequence in which the (sub)techniques are presented, however, does not suggest that the (sub)techniques become more invalid or that everyone starts with the first technique, or moves in a linear fashion, or follows the same sequence.

I. Distorting the facts

The distortion of facts is the first category of neutralizations. People employ this kind of neutralizations to misrepresent the facts to themselves or to others so that there will no longer be a violation of a particular norm. They deliberately change or distort memories, scenes, events, and evidence to reframe the situation (Cavanagh et al. Citation2001) and thereby change their reality (Rogers and Buffalo Citation1974). Agnew (Citation1994:122) observes that neutralizations provide an “often distorted portrayal of the events and conditions that contribute to (one’s) crime.” Murphy (Citation2012) suggests that in many cases offenders reconstrue the circumstances to justify the act. We found that distorting the facts can be done by nuancing, denying, and inventing the facts.

1. Nuancing facts

The nuancing of facts is a technique whereby people escape reality by suggesting that there are no (hard) facts and that in general or in the specific situation there is no truth. This technique consists of the subtechniques of nuancing that there exists a truth, that there is one truth, that the truth is easy to know, that there is a truth even if unproven, and that there is a truth even if not observed personally.

The most fundamental subtechnique to deny deviant behavior is to argue that truth does not exist and that everything is virtual. This is also the safest way to distort the facts because when this technique fails all other techniques are still possible. This technique resembles the idealist–skeptic approach that doubts the existence of any real world independent of the mind. Smith (Citation2011) points out that this is an epistemic fallacy because it relativizes reality: People claim that because they cannot know the truth then reality does not exist or that it cannot exist independently of their knowledge of it. On this view, facts are degraded to artifacts. This is also the postmodern fallacy of ineffability or complexity, also called post-truth: People arbitrarily declare that the world is so complex that there is no truth, or if truth exists, then it is unknowable (Williamson Citation2015).

A slightly less fundamental subtechnique is that people recognize that there is truth to the matter but that everyone may have their own perception and interpretation of what is true and untrue. They then suggest that there are no neutral observations of the world, that all knowledge is conceptually mediated because there is no universal, indubitable, and neutral foundation for knowledge (Smith Citation2011). This so-called judgmental relativist approach to reality concedes that a real world exists but that different accounts of the truth may exist because the truth of each account is believed to be always relative to the paradigm that generates the account (Smith Citation2011). For example, Fooks et al. (Citation2013) found that managers at a tobacco company neutralized the harmful effects of smoking, which were pointed out by the stakeholders, by believing that the stakeholders’ views were erroneously accepted as facts. In discussing neutralizations, Murphy (Citation2012) posits that people can reject facts by arguing erroneously that it cannot exist if they do not believe it.

People can acknowledge that there may be one universal truth about reality, but by suggesting that truth is difficult to know they create room to make up their own favorable interpretation of the truth. For example, people can claim that the situation is so complex that only they themselves can determine what is real and unreal or that knowledge is reserved only for insiders. Williamson (Citation2015) calls this the fallacy of esoteric knowledge. By nuancing that truth is easy to know, people may argue that truth is (always) in the middle thereby dismissing the viewpoints of others as being too extreme. People may also argue, following a conventionalist approach of facts (Smith Citation2011), that as long as there is no consensus about truth, truth does not exist and thus people are free to have their own ideas about reality.

Instead of arguing that evidence to know what is true is always incomplete, people can also argue that the truth of the matter can be known but only when it is proven. For example, something is true or false only if it is proven to be true or false, or when it is scientifically validated, or when it is measured and quantified. By following this neopositivistic line of reasoning, people may therefore suggest better measures and collecting more empirical data (Smith Citation2011). This is also called the fallacy of moving the goalpost: People escape the truth by arguing every time to wait for more evidence (Fuller Citation2002). Williamson (Citation2015) calls this the fallacy of measurability: If something cannot be measured and quantified, then it does not exist or only anecdotal and unworthy of serious consideration. Reed and Janis (Citation1974:3461) found that smokers denied the dangerous effects of smoking by arguing, “It has not really been proven that cigarette smoking is a cause of lung cancer.”

Even when the facts are proven, people can nuance them by suggesting that they should first observe the facts themselves before it can be true. As long as they have not observed the facts themselves it is not real, and judgment has to be suspended (cf. Hewitt and Stokes Citation1975). Kooistra and Mahoney (Citation2016) found that this technique is extremely important in war where soldiers justify their killing by believing that their actions harm no one. Solders can deny the existence of their victims and their victims’ injuries because they do not see their faces and bodies. Rhodes and Cusick (Citation2002) found that people justified unprotected sex even when they were diagnosed to be HIV-positive; they thought that because they did not fell ill then they had beaten the disease. This subtechnique entails what Parfit (Citation1984) claims as one of the mistakes of moral mathematics: When one only believes what one sees thereby ignoring small chances and imperceptible effects.

2. Denying the facts

The second technique involves the denial of one or more facts surrounding the deviant behavior. Whereas the first technique concerns general perspectives regarding truth, this second technique concerns concrete facts in concrete situations. Even when people acknowledge that there is truth to the matter, they can still avoid the complete truth by denying one or more of the relevant facts. Consciously pretending that nothing really happened is, according to Cavanagh et al. (Citation2001), a critical element in the arsenal of neutralizations. They found selective amnesia to be a significant feature of men neutralizing their violence toward their partners thereby reducing their violence to “unreality.” Von Hippel and Trivers (Citation2011) argue that one engages in this kind of conscious self-deception by rehearsing the lies in one’s mind until one convinces oneself of their truth. This is what Ashforth and Anand (Citation2003) call minimization: People technically accept what happened but only in a “watered down” form, and by suppressing the knowledge, at the extreme, they selectively forget the deviant behavior such that in some sense it never happened. The denial of facts can be related to the consequences of one’s behavior and to one’s behavior, intentions, circumstances, and impotence.

The technique involving the denial of consequences is referred to in the literature as the denial and minimization of damage (Schönbach Citation1990) or harm (Fooks et al. Citation2013). Misconstruing or disregarding the consequences of the act makes the consequences appear less real than they actually are so that there is less reason for self-censure to be activated (Bandura et al. Citation1996). White, Bandura, and Bero (Citation2009) found that aggressors neutralized their behavior by discrediting any evidence of harm. Bandura et al. (Citation1996) found that people using this technique were less able to recall the harmful effects of an act. Ignoring the effects of actions is also one of the mistakes in moral mathematics suggested by Parfit (Citation1984). As an example, Banerjee, Hay, and Greene (Citation2012) found that 10% of their participants believed that the use of tanning beds could not be all that bad because many people who use tannings beds have long lives.

Although people can acknowledge the consequences of their actions, they can still deny the existence of the underlying behavior. Schönbach (Citation1990) identifies this as the denial of the occurrence of the alleged failure event. For example, Maruna and Copes (Citation2005) found that many rapists hold the belief that their action did not involve any force even though they raped with a weapon or during a burglary. People can also deny that they were present at the moment of the wrongdoing by, for example, suggesting, “I wasn’t here” (Kaptein Citation2005). Schönbach (Citation1990) discussed this technique as one of the accounts where there is acknowledgment of the negative aspects of the failure event but no concession of one’s own involvement. Stadler and Benson (Citation2012) found that 21% of the white-collar inmates they sampled denied any involvement in the wrongdoing that led to their imprisonment.

Another neutralization technique is the denial of intentions. When people acknowledge that certain behavior has occurred they can still escape reality by denying that they did it intentionally. Henry and Eaton (Citation1999) call this technique denial of negative intent and Stadler and Benson (Citation2012) calls it denial of criminal intent. Von Hippel and Trivers (Citation2011) argue that even if one and others accurately recall one’s prior wrongdoing, it is still possible to avoid telling oneself the whole truth by reconstructing the motives behind the original behavior. People are able to misinterpret and distort their bad intentions. Von Hippel, Lakin, and Shakarchi (Citation2005) have also conducted research to demonstrate this subtechnique. In their laboratory experiments, people were more likely to cheat when their cheating could be cast as unintentional, and they were less likely to cheat when their cheating was clearly intentional.

Even when people acknowledge the behavior, intentions, and consequences of the behavior, they can neutralize their deviant behavior by denying evidence about the circumstances (Fooks et al. Citation2013). Rhodes and Cusick (Citation2002) found that people neutralized unsafe sex by employing wrong arguments to ignore that the other person may be HIV-positive. For example, “You’re big and slim, you can’t be HIV positive.” A frequently noted element in the denial of facts in this context is the denial of humanity, which is proposed by Alvarez (Citation1997). When humans are dehumanized and viewed as pigs (Gailey and Prohaska Citation2006), as targets (Levi Citation1981), as not normal (Darley Citation1992), as inferior to us (Byers, Crider, and Biggers Citation1999), as subhuman (Alvarez Citation1997), as cogs in a wheel (Martin, Kish-Gephart, and Detert Citation2014), and as suckers (Anand, Ashforth, and Joshi Citation2004), then it becomes easier to commit harm toward them.

A final subtechnique of denying the facts is denying one’s impotence. People do not deny the consequences, behavior, intentions, or the circumstances, but they create a less negative or more positive view of their own knowledge and capabilities. Ashforth and Anand (Citation2003) consider the illusion of control to be one of the neutralizations for corruption in business. By having an inflated perception of one’s self by, for example, arguing that “Whatever the problems, if any, I felt I could handle them” and “Nothing could hurt me”, people can ignore problems. There is also Josephson and Hanson (Citation2002) argument from omniscience: people argue that conflicts of interest do not affect their judgment even though their objectivity has been affected. Nelson and Lambert (Citation2001) also found that professors who were accused of bullying used the technique of evidentiary solipsism in which the professors portrayed themselves as uniquely capable of divining and defining the “true” meaning structure of events, thus making it possible for them to develop a quite foreign interpretation of what has happened.

3. Inventing new facts

Inventing new facts is another technique to distort facts. People imagine and fantasize about a situation in which the violated norm no longer (fully) applies. This technique goes further than the techniques discussed above because it is more active: The person creates a new reality. People claim that there is another truth or that it is not the whole truth, or that others are ignoring the facts, or that there is more going on than meets the eye (Williamson Citation2015). The distinction between fact and fiction becomes blurry. Fantasizing is a pathological defense mechanism that involves creating an inner world when the real world becomes too painful, difficult, or stressful (Niolon Citation2011). Fantasizing results in a reality so distorted that one can stop neutralizing further one’s deviant behavior. Five subtechniques of inventing new facts are inventing consequences, behavior, intentions, circumstances, and one’s potence.

Inventing consequences can be both in a positive and negative sense. Regarding negative consequences, Reed and Janis (Citation1974) found that smokers neutralized not to stop smoking because they imagined that “If I stop smoking I will gain too much weight.” Regarding positive consequences, Moore and McMullan (Citation2009) found that some participants in their study argued that file sharing helped rather than harmed musicians because file sharing could make a musician’s work more popular, which would then translate to more earnings. Rhodes and Cusick (Citation2002) found that people who have had a condom accident used it as neutralization for unprotected sex, claiming that unsafe sex has already occurred. They invented consequences such as they were already HIV-positive or the accident would occur again anyway.

Instead of inventing consequences, people can also invent facts about their behavior. This is done by, for example, making the wrong assumptions or drawing the wrong conclusions. Reasons such as “No news is good news” and “Where there’s smoke, there’s fire” are completely fictitious suggestions about potential underlying behavior (Williamson Citation2015). Improperly concluding that one thing is the cause of another – the fallacy of non-causa pro-causa (Fuller Citation2002) – and equating correlation with causation both create a wrong picture of what the actual (real) behavior is. People can also invent behavior by pretending that they acted or did something even when they actually did not. Instead of neutralizing their inaction or lack of response toward the deviant behavior of others, people can fantasize that they confronted the wrongdoers, that they told the wrongdoers to stop, or that they pointed out the wrongdoing to others who can stop the wrongdoer.

Another subtechnique is to invent intentions. In this situation people imagine that they have a better motivation than they actually do. For example, Scully and Marolla (Citation1984) found that rapists neutralized their behavior by claiming that they loved the woman thus they overestimated their own intentions. Geva (Citation2006) notes that by pretending that one’s motivation is actually good, one then neutralizes one’s deviant behavior. This is supported by a field study of Gauthier (Citation2001), who found that veterinarians neutralized the substandard care they provided by pretending that they were not driven by pecuniary motives but by ethical motives to help others.

People can also invent facts about the situation. One can do this by interpreting the situation in such a way that there is no deviant behavior anymore. For example, in the study of Scully and Marolla (Citation1984), one of the rapists said, “It was like she was saying, ‘rape me’”; another rapist said, “All woman say ‘no’ [when you want to woo her] when they mean ‘yes.’” Gilgun (Citation1995) also found pedophiles who imagined children to be older by avoiding eye contact with their victims. By imagining new developments too positive people can neutralize their behavior. For example, Banerjee, Hay, and Greene (Citation2012) found users of tanning beds neutralized their behavior with the claim that in the event they would get skin cancer there would be a cure available. Stuart and Worosz (Citation2012) found that industrial food processors neutralized their behavior of not protecting consumers better by an unwavering faith in the progress of science and technology.

A final identified subtechnique for inventing facts is inventing facts about their potence to create a less negative or more positive view about themselves. Benoit and Hanczor (Citation1994) describe the story of a famous figure skater who neutralized her lies about an attack by claiming that she was scared she would be hurt if she had been honest. Gilgun (Citation1995) found that pedophiles ignored the age discrepancies by experiencing themselves as younger and being a kid again.

II. Negating the norm

The second category of neutralizations that deny deviant behavior is one that negates the norm. The facts are not distorted but the decisive norm that should be applied to the situation or behavior is being refuted. This category consists of three techniques: reducing norms to facts (when people deny that a norm is relevant in the situation), appealing to another norm (when people acknowledge the norm that is violated but justify the violation by appealing to another more important norm), and relativizing the norm violation (when people acknowledge that the norm is violated wrongfully but mitigate the wrongness by comparing it to other behaviors).

4. Reducing norms to facts

Reducing the norm to facts is one way of negating the relevant norm. The relevance of norms is then ignored and excluded. Five identified subtechniques are the reduction to facts, to taste, to labels, to the immorality of condemners, and to an invalid norm.

The first subtechnique for negating the norm is to reduce it to facts. This involves people arguing that there are only facts in their situation hence there is no room for norms or normative judgments. From this moral nihilist perspective, people claim that the facts are given thus they do not require any interpretation; it is a fait accompli; it is what it is. This subtechnique functions as an a priori argument about how reality is. For example, “That is just the way the world works” (Maruna and Copes Citation2005) and “It’s just the fact” (Topalli Citation2006). In addition, the statement, “I do it anyway” (Atkinson and Kim Citation2015) absolves people from any moral reflection, and “It’s something that’s been here so long,” (Forsyth and Evans Citation1998) hides them behind collective traditions and folkways.

The next subtechnique is the reduction of the norm to taste. By suggesting that morality, as set of norms, is taste people acknowledge that there is morality but that this is subjective, individualistic, and personal (Kaptein and Wempe Citation2002). This implies that people are free or even have the right to choose and do not have to account for their choice to others. From Williamson (Citation2015), we gathered the following examples of this kind of neutralization: “It is my own life,” “You’re not the boss of me,” and “So what?” Other examples we have identified are “It is none of their business” (Marx Citation2003) and “That is no business of yours!” (Fritsche Citation2002). Henry and Eaton (Citation1999) labeled this neutralization as the claim of individuality: People do not care what others think of them or their behavior.

A third subtechnique is the reduction of the norm to labels. In this case people acknowledge that morality is not individualistic but they describe or redescribe the facts (Geva Citation2006) with the use of labels so that morality is excluded or reduced. Examples of labels are metaphors, analogies, euphemisms, acronyms, and jargons. Because language not only shapes people’s thought patterns but it is also malleable in itself, it is a convenient tool for neutralization (Ashforth and Anand Citation2003). By using sanitizing and convoluted language (White, Bandura, and Bero Citation2009) people engage in interpretative denial (Cohen Citation2013) and false labeling. Geva (Citation2006) calls this euphemization rationalization. Examples of labels that neutralize are car theft as joyride (Copes Citation2003), stealing as adjusting income (Shigihara (Citation2013), corruption as hospitality (Lowell Citation2012), and sexual abuse as teaching love (Gilgun Citation1995).

A more offensive subtechnique is reducing the norm to the immorality of the accusers; this corresponds to Sykes and Matza (Citation1957) neutralization of the condemnation of the condemners. People disparage and denigrate their accusers to show that they do not have the right to accuse, and therefore the norm the accusers proclaim can be dismissed (Fritsche Citation2002; White, Bandura, and Bero Citation2009). This subtechnique is different than the reduction-to-taste technique because it does not involve ignoring one’s accountability toward others. Rather it involves ignoring one’s accountability toward specific people in a particular situation. Claiming that the accusers are “hypocrites, deviants in disguise, or impelled by personal spite” (Sykes and Matza Citation1957), malicious and devious (Garrett et al. Citation1989), unfair (Rogers and Buffalo Citation1974), uninformed and biased (Rosecrance Citation1988), silly (Forsyth and Evans Citation1998), brainwashed (Durkin and Bryant Citation1999), neurotic (Irwin Citation2001), hostile (Maruna and Copes Citation2005), and “are making a career out of moralizing” (Kvalnes Citation2014) all fall under this subtechnique.

A final subtechnique of reducing norms to facts is arguing that the norm is invalid and irrelevant. One acknowledges the existence of morality and the specific norm being violated but one argues that it is only relevant for others. Some examples are “We are above the law,” “Rules are meant for other people,” and “Ethics and laws are for lesser firms” (Anand, Ashforth, and Joshi Citation2004; Barriga and Gibbs Citation1996). Individuals could also acknowledge that the norm is relevant for them but then argue that the norm in question is not meant to be followed, such as the belief that a specific rule is meant to be broken (Kooistra and Mahoney Citation2016). Liddick (Citation2013) calls this subtechnique the denial of the necessity of the law. The use of this technique can be initiated by portraying the norm as too restrictive (Siponen and Vance Citation2010), too ambitious (Lanier and Henry Citation2004), too vague, complex, and inconsistent (Ashforth and Anand Citation2003).

5. Appealing to another norm

When people acknowledge that the relevant norm is at stake, they can neutralize the violation of this norm by appealing to a higher, more important norm that needs to be followed. In this sense there can even be “a moral inversion, in which the bad becomes good” (Adams and Balfour Citation1998:11). Bandura et al. (Citation1996) call moral justification of people’s detrimental behavior by reconstrueing it in the service of valued social or moral purposes. Five relevant subtechniques are appealing to higher goals, to others and to their expectations, to rules and regularity, to intentions and intuition, and to self-interest or the lack thereof.

Appealing to higher goals is used to justify deviant behavior based on a goal that one considers more important than the norm that is being violated. Liddick (Citation2013) and Schönbach (Citation1990) call this the appeal to a higher moral principle and the appeal to positive consequences, respectively. This goal can be expressed in general terms, as in “It’s for the greater good” (Martin, Kish-Gephart, and Detert Citation2014) and “It’s for their own good’’ (Johnston and Kilty Citation2016). It can also be expressed in more specific terms, as in “to free animal slaves” (Liddick Citation2013) and “to maintain a good business relationship with a good customer” (Rabl and Kühlmann Citation2009). It is especially when the cause is noble that it is attractive to use as a “higher goal” because it makes the bad behavior appear good (Fooks et al. Citation2013).

Another subtechnique to deny the applicable norm is by appealing to others and to their expectations. In this case, one argues that the norm to be followed is determined by others. This is different than appealing to higher goals where people themselves determine and defend the norm that should be followed. In appealing to others and/or to their expectations, the others in question could be a role model (Dunford and Kunz Citation1973), an authority (Gilgun Citation1995), or one’s group (Moore et al. Citation2012). Also those who are harmed – whether they (will) ask for the wrongdoing, or agree with it, or not refuse it (Wortley Citation2001) – can be the “others” that could be appealed to. What others do or will do can also be used as neutralization: “They would have done the same to us” (Kvalnes Citation2014). Henry and Eaton (Citation1999) call this neutralization the claim of normalcy. What others evoke is also used to justify norm violation: “Suckers deserve to be taken advantage of” (Costello Citation2000) and “You get what you pay for” (Gauthier Citation2001). Rice (Citation2009) calls this the abuse defense.

People can also appeal to a right to neutralize deviant behavior. They hide behind moral and legal rights, by calling upon laws, rules, agreements, and promises. Some examples are “The law says this, and I follow it” (Osofsky, Bandura, and Zimbardo Citation2005), “It is my contract” (Levi Citation1981), and “It’s legal, it’s ethical” (Geva Citation2006). Fooks et al. (Citation2013) found that corporate actors even justified deviant behavior with reference to some unspecified universal right that protects the freedom of businesses. This technique is known by many names: as the defense of the necessity of the law (Coleman Citation2005), the defense of legality (Fooks et al. Citation2013), the appeal to legal rights (Garrett et al. Citation1989), and the appeal to the right of self-fulfillment (Schönbach Citation1990).

Another subtechnique is the appeal to good intentions. People acknowledge that their behavior is wrong but that their good intentions or the lack of any bad intention, make the behavior not deviant. In other words, deviant behavior is unproblematic as long as people do their best (cf. Schönbach Citation1990). This is what Ferraro and Johnson (Citation1983) refer to as the appeal to the salvation ethic: People do bad things but claim to have good intentions. Some examples of this subtechnique are “I didn’t mean it” (Sykes and Matza Citation1957) and “It was an honest mistake” (Eliason and Dodder Citation1999). Forsyth and Evans (Citation1998) found this subtechnique, which they call the we-are-good-people defense, among dogmen. Following one’s intuition belongs also to this subtechnique: As long as people personally feel comfortable with it, they can sleep with it, and can look themselves in the mirror, then it is good and thus there is no deviant behavior (cf. Badaracco and Webb Citation1995).

A final subtechnique to appeal to another norm is appealing to self-interest or to the lack thereof. When people point to the lack of self-interest to justify their bad behavior, they mean that they too are hurt by the bad behavior or that they are not benefitting from it. Examples of such neutralizations are “I didn’t do it for myself” (Lanier and Henry Citation2004) and “There was not personal gain in it for me” (Coleman Citation1987). When appealing to one’s own self-interest people argue that it is reasonable for them to give priority to, for example, their own needs, pleasure, or survival. This egocentric approach is more problematic than the other subtechniques of appealing to another norm because it is most remote from considering the interests of all stakeholders (Kaptein and Wempe Citation2002). Examples of such neutralizations are “If I really want something, it doesn’t matter how I get it” (Barriga and Gibbs Citation1996), “I am interested in my own advantage” (Gruber and Schlegelmilch Citation2014), and “She’s my daughter. She needs to take care of my needs” (Gilgun Citation1995).

6. Relativizing the norm violation

People employ the technique of relativizing the norm violation when they acknowledge that they have breached a norm but that it is not “that” bad. We have identified five arguments by which the relativization takes place: others (as long as others are as bad or even worse), the frequency (as long as it is not too often), the seriousness (as long as it could be worse), the good deeds (as long as it is in balance), and regret (as long as there is remorse). These subtechniques are arranged according to decreasing number of arguments available for neutralizing: relativizing has less depth and are less persuasive and thus closer to the admission of deviant behavior.

People can compare their wrongdoing to that of others to neutralize their own behavior. This technique, also known as the reference to the sin of others (Fritsche Citation2002) or selective social comparison (Anand, Ashforth, and Joshi Citation2004), can make use of stereotyping: people distinguish themselves from a stereotype of a more vicious kind (Jennings Citation1990). Some general examples of this subtechnique are “At least we’re not doing what those people are doing” (Martin, Kish-Gephart, and Detert Citation2014) and “Others are worse than we are” (Anand, Ashforth, and Joshi Citation2004). Some specific examples are “Stealing some money is not too serious compared to those who steal a lot of money” (Bandura et al. Citation1996) and “Throwing a gum wrapper out the car window is nothing compared to the damage caused by violent criminals” (Liddick Citation2013). In this regard, people can also argue that if they do not do it someone else will and in a worse way (Coleman Citation1987; Lanier and Henry Citation2004; Levi Citation1981).

When people cannot compare their behavior to those of others to justify a norm violation, they can focus on their own behavior and argue that their behavior is not (that) bad as long as it not does occur (too) frequently. People relativize frequency when they claim, “It is just for one time” (Rosenbaum, Kuntze, and Wooldridge Citation2011), “It was an exception” (Fritsche Citation2002), and “It is okay if I do something questionable every now and then” (Hinduja Citation2007). Rosenbaum, Kuntze, and Wooldridge (Citation2011) call this subtechnique “first-time only-time crime”. They found it used in cases of fraud among consumers who did not deny the illegality of their behavior but saw it as an exception, as a singular instance of deviant behavior.

Even when people have to acknowledge that any wrongdoing is wrong, they can still neutralize their own wrongdoing by relativizing its seriousness. They compare their behavior to a (potentially) worse one so their own wrongdoing will appear less or not bad at all. They can then claim that their behavior could have been worse. So people say for example, “I may be bad, but I could be worse” (Cromwell and Thurman Citation2003), “It is okay to insult a classmate because beating him/her is worse” (Bandura et al. Citation1996), and “I did use force, but not as much force as I probably could have” (Cavanagh et al. Citation2001). These cases are characterized by a comparative standards justification (Schönbach Citation1990), advantageous comparison (Bandura et al. Citation1996), or claim of relative acceptability (Henry and Eaton Citation1999).

Another way to relativize a norm violation is to argue that the wrongdoing is neither not bad nor less bad but that it is in balance. This subtechnique comes after the previously mentioned subtechniques because here one acknowledges that the behavior itself cannot be made less bad but that it can either be compensated for by one’s own good deeds or be seen as a compensation for the bad behavior of others. This subtechnique is also called the metaphor of the ledger (Klockars Citation1974), moral licensing (Merritt, Effron, and Monin Citation2010), claim of entitlement (Coleman Citation2005), and merit-based account (Shigihara Citation2013). Examples of this technique are “I felt like the world owed me something” (Copes Citation2003), “I’ve done more good than bad in my life” (Lanier and Henry Citation2004), and “After years of slaving for this company, I have a right to steal a few office supplies” (Liddick Citation2013).

The final relativization subtechnique in this category is people arguing that deviant behavior is acceptable as long as they regret it, or as long as they want to learn from it or promise to better their lives. Promised reform, such as “I will certainly change my behavior in the future” is what Fritsche (Citation2002) calls the affirmation to abstain from the deviant behavior in the future. This subtechnique is also called justification by postponement (Piacentini, Chatzidakis, and Banister Citation2012) and the appeal to own learning experience (Schönbach Citation1990). It is the least safe of the five subtechniques for relativizing norm violation because people compensate for their wrongdoing only with words, which can convince the least.

III. Blaming the circumstances

People use the neutralizations that fall under categories III and IV when they acknowledge that their behavior is wrong but argue that their responsibility for their behavior is either reduced or absent. Sykes and Matza (Citation1957) call this denial of responsibility, Bandura et al. (Citation1996) refer to it as the diffusion and displacement of responsibility, and Rhodes and Cusick (Citation2002) as the denial of agency. With this neutralization people claim that one or more of the conditions for responsible agency are not met (Kvalnes Citation2014), hence the link between them and their behavior is broken (Serviere-Munoz and Mallin Citation2013). They claim that they are not themselves acting but are being acted upon (Sykes and Matza Citation1957). Whereas with Category III neutralizations people shirk their responsibilities by blaming the circumstances, with Category IV neutralizations people shirk their responsibilities by reducing themselves. We can recognize Category III neutralizations in the literature as externalizing blame (Stadler and Benson Citation2012), apportioning blame elsewhere (Goffman Citation2009), and scapegoating (Scott and Lyman Citation1968). This category of neutralizations consists of three techniques that limit the options, the role, and the choice.

7. Blaming the limited options

People using the limitation-of-options neutralization try to deny their moral agency by reducing or removing their options. By claiming that they do not have any real options or that they have less (easy) options, they are then claiming that they are not (or less) morally responsible for their wrongdoing. Because there is no realistic and better alternative, they are forced to behave deviantly. Minor (Citation1981) calls it the defense of necessity when people claim to have no other acceptable option under the constraining circumstances but to engage in deviant behavior. The relevant subtechniques involve blaming the limitations of being confronted with one option, with conflicting options, with difficult option(s), with unrealistic option(s), and with a unique option.

By suggesting that they are confronted with only one (real) option, people claim to have no other option (anymore) than to do what they have done or what they are about to do (Anand, Ashforth, and Joshi Citation2004). One is unable to do the right thing because there is no other alternative (Geva Citation2006). Some examples of such neutralizations are “I knew it was wrong, but I just didn’t have any other choice” (Cromwell and Thurman Citation2003), “It’s not my fault, I had no other choice” (Strutton, Vitell, and Pelton Citation1994), and “What can I do? My arm is being twisted” (Anand, Ashforth, and Joshi Citation2004). Ferraro and Johnson (Citation1983) name this subtechnique the denial of either practical or emotional options. In their research, the battered women used the denial-of-emotional-options technique: They felt that no one else other than their abusive partners could provide them the intimacy and companionship they needed.

Instead of arguing that they do not have any option, people can claim to be confronted with conflicting options or norms. By using this neutralization people suggest that they are in a dilemma when actually there are more alternatives available, or the options available do not really contradict each other. Geva (Citation2006) refers to this as the creation of a false dilemma. The use of this subtechnique suggests that people have more freedom than the use of the preceding subtechnique implies. Claiming to be confronted with conflicting options or norms means that the individual can now choose between two (or more) options (and not just have one). The fact that the options are considered conflicting means that although the norms they express might be different they are of the same importance. This implies that choosing the actually less important norm is justified. Examples of this subtechnique are “Both targets are due; unfortunately, we have to make a choice” (Geva Citation2006) and “If I stand in front of the shelf and there are five products and all five products are equally bad I can only choose the lesser of two evils” (Gruber and Schlegelmilch Citation2014).

People can also blame the circumstances by claiming that the option they have is a difficult one. In this situation, people do not deny that they have another option or claim that all options are similar or equally important, but they acknowledge that the preferable course of action can be chosen. However, by arguing that the circumstances (e.g., systems and procedures) are complex or even irrational and crooked, they are claiming that they cannot be blamed for failing to behave compliantly (cf. Benoit and Hanczor Citation1994). For example Gruber and Schlegelmilch (Citation2014) found that consumers neutralized their behavior of not boycotting unethical companies by appealing to the interconnectedness and complexity of products and supply chains as well as that “so many products have a name that doesn’t reveal the company behind it, it’s not possible.”

People can also claim to be confronted with an unrealistic option as a way of blaming the circumstances. While acknowledging that the best option is available, people can neutralize their deviant behavior by claiming that the circumstances do not offer more realistic options thereby asking too much of them (Rosenbaum, Kuntze, and Wooldridge Citation2011). For example, Brunner (Citation2014) found that consumers neutralized their failure to buy fair trade products by claiming that these products are too expensive and there are no cheaper alternative fair trade products. In this regard, people can also argue that because the circumstances are bad, it is unrealistic for them to behave well. An example of this neutralization is “Life is unfair, and everyone is corrupt and it is a rat race to get ahead, regardless of who gets hurt” (Hinduja Citation2007). This subtechnique is riskier than the previous three discussed above because arguing that one is being asked too much is quite akin to the idea that is part of category IV: that one is not prepared to pay a price for being compliant.

The final subtechnique of the limitation of options is claiming that one is confronted with a unique option. In this case, people acknowledge that they have a realistic option to behave compliantly but they neutralize their deviant behavior by suggesting that the circumstances do not offer sufficient chances or offer only a once-in-a-lifetime chance. Research shows that people neutralize their theft (Cromwell and Thurman Citation2003), illegal behavior (Hinduja Citation2007), and price fixing (Sonnefeld and Lawrence Citation1978) by seeing it as being confronted with a unique option. Some examples are “It’s okay to take little things from stores, if it is the only way to get it” (Topalli, Higgins, and Copes Citation2014) and “It was a case of emergency” (Dunford and Kunz Citation1973).

8. Blaming the limited role

Instead of pointing to the limited options, people can also blame the circumstances by limiting their role. In this respect, people do not deny that there is the option to behave compliantly. Instead they claim to have less or no relationship with and thus no responsibility for the deviant behavior. People can do this in several ways, by claiming that they are not responsible, that they have no responsibility, that they are not the only one responsible, that only others are responsible, or that the context is responsible.

By claiming that one is not responsible, one is saying that one is either not the cause or only remotely the cause of the wrongdoing. Thompson (Citation1980) calls this the excuse from null cause: People then do not hold themselves responsible for a behavior when a subsequent action by another can control or determine whether their own action will have any effect. People can also neutralize their responsibility by arguing that they are not doing anything. They claim that because they do not directly cause the wrongdoing, then they are not responsible for solving it or that their contribution to the solution for a wrongdoing is limited (cf. Fritsche Citation2002). This neutralization ignores the possibility that one can contribute to a wrongdoing even if or precisely because one is not doing anything. Examples of such neutralizations are “I played such a small part that I’m not really responsible” (Moore Citation2008) and “I learned a long time ago not to worry about things over which I have no control” (Maruna and Copes Citation2005).

People can also limit their role with regard to the wrongdoing and deny any responsibility by claiming that the prevention or solution of the wrongdoing is not their formal task, function, or job. “It’s not my job” is, according to Thompson (Citation1980), a common excuse to cut short any argument about whether an official could make any difference. Although one cannot be responsible for everything, it is, as Thompson argues, not enough to claim that one’s formal role does not require taking other actions. Examples of this subtechnique are “It is none of my business” (Anand, Ashforth, and Joshi Citation2004), “I don’t feel that it’s my responsibility. They are grown adults” (Rhodes and Cusick Citation2002), and “It is not an employee’s responsibility to report corporate violations to any outside source” (Clinard Citation1983).

Even when people acknowledge their responsibility, they can still try to reduce it by arguing that they alone are not responsible, thus implying a shared responsibility. For example, “We were all in on it” (Maruna and Copes Citation2005) and “We did it together” (Rhodes and Cusick Citation2002). In this case, there is dispersal of blame and partial transfer of responsibility (Thompson Citation1980). Schönbach (Citation1990) calls this an appeal to participation as coactor in the failure event. People can also suggest that their behavior is the result of the behavior of others (Fulkerson and Bruns Citation2014). For example, Nelson and Lambert (Citation2001) found that bullies portrayed themselves as the victim rather than the agent of bullying. Rice (Citation2009) shows how offenders use the neutralization of protecting themselves and others to shift part of the blame for their wrongdoing to those who started with the wrongdoing.

A riskier technique than partly blaming others is to blame them fully and hold them completely responsible thus fully denying one’s own responsibility (Barriga and Gibbs Citation1996). For instance, “It is the company’s responsibility to make sure that things like this don’t happen” (Bersoff Citation2001) and “Caveat emptor” (Piquero, Tibbetts, and Blankenship Citation2005). People can also deny full responsibility by claiming that they are dependent on others to be able to do what is good. Fritsche (Citation2002) describes this as the reference to the helplessness of the individual, where one’s own good behavior is only useful if others act in the same way. For instance, “I will never be able to change anything if others don’t also stop” and “Why should I be the first?” (Fritsche Citation2002). These neutralizations are also called the pioneer’s lament (Marshall Citation2017). People can also claim that others are responsible because, for example, the latter have the expertise (Johnston and Kilty Citation2016) or initiated the wrongdoing (Stuart and Worosz Citation2012).

If people cannot partly or fully apportion responsibility to others, they can then try to hold the context responsible for their wrongdoing. Time pressure is one possible excuse (Schönbach Citation1990). So people argue that they are overloaded (Haines et al. Citation1986). Other things that people can blame are their jobs: “I hated doing it, but it’s my job” (Geva Citation2006) and “My job made me a real bitch” (Thompson, Harred, and Burks Citation2003); technology and tools: “I did not kill, my gun or grenade did it” (Kooistra and Mahoney Citation2016) and “The computer is to blame” (Geva Citation2006); receipt of inadequate information: “Information didn’t reach me” (Geva Citation2006) and “We received unreliable or inadequate advice” (Rhodes and Cusick Citation2002); culture: “The messenger gets shot a lot” (Badaracco and Webb Citation1995) and “They don’t trust me” (Marx Citation2003); and childhood: “It’s not my fault. I commit crime because I had a troubled childhood” (Liddick Citation2013).

9. Blaming the limited choice

Next to using the excuse of having limited options and role, people can blame the circumstances by claiming to have limited choice. In this case, people do not deny their moral autonomy but suggest that this is threatened and undermined by pressures and temptations. These pressures and temptations are quite difficult to resist because they are overwhelming and irresistible; thus, it is but reasonable that one succumbs to them. People attribute their limited choice to several things: pressure from authority, group pressure, performance pressure, an overwhelming temptation, and a very big opportunity.

In appealing to pressures from authority as an excuse, people are claiming that they behave deviantly because of the influence of, or force or coercion from an authority figure (Bandura et al. Citation1996; Moore et al. Citation2012; White, Bandura, and Bero Citation2009). Kelman and Hamilton (Citation1989:16) note that basically in a situation when someone has authority over another, “actors often do not see themselves as personally responsible for the consequences of their actions. … They are not personal agents, but merely extensions of authority. Thus when their actions cause harm to others, they can feel relatively free of guilt.” So, for instance, people say, “I felt pressured by the boss” (Mayhew and Murphy Citation2014), “I was made to do it by my boss” (Moore Citation2008), or “I felt unduly pressured by top management and supervisors” (Clinard Citation1983).

Appealing to group and peer pressures is another subtechnique to limit one’s choice. It is less safe than appealing to authority figures because following the instructions or commands of an authority is the basic idea of hierarchy (Maruna and Copes Citation2005) and is therefore less unconvincing to oneself or others than satisfying or living up to the expectations of one’s group and peers. Examples of this subtechnique are “Kids cannot be blamed for misbehaving if their friends pressured them to do it” (Bandura et al. Citation1996), “When I would screw it up I would be sanctioned by exclusion” (Celsi, Rose, and Leigh Citation1993), “I do it to impress others” (Rosenbaum, Kuntze, and Wooldridge Citation2011), and “I would be a party pooper” (Priest and McGrath Citation1970).

People can also blame the pressures caused by performance expectations, objectives, and targets. For example, by suggesting that the performance criteria are set too high, people create an excuse for behaving deviantly to meet these criteria. This subtechnique is different from the subtechnique of conflicting options because it is not about norms conflicting with each other but about one norm conflicting with a goal or interest. Examples of this subtechnique are “We have to hit the numbers” and “Even if it requires practices that are unethical, middle management has to try to meet a corporation’s objective” (Clinard Citation1983). The threat and fear of being punished for not meeting the performance criteria can be used to deny one’s responsibility (Coleman Citation1987). In this regard, Anand, Ashforth, and Joshi (Citation2004) cite a marketing officer, “When we didn’t meet our growth targets, the top brass really came down on us. And everybody knew that if you missed the targets enough, you were out on your ear.”

People can also appeal to the irresistibility of an all-too-powerful temptation to make their deviant behavior plausible. With this subtechnique, people still blame the context but it is less safe than the preceding subtechniques because it quickly suggests a weak personality of not willing or being able to resist temptations (which is part of category IV). Perpetrators of sexual abuse frequently use this argument; they accuse their victim of being a seductress and being provocative (Fulkerson and Bruns Citation2014; Hall, Howard, and Boezio Citation1986; Scully and Marolla Citation1984). Vasquez and Vieraitis (Citation2016) also found that street taggers blamed their actions on being victims of seduction. As one tagger said, “It’s like the walls are telling me to tag. I hear them calling my name everyday when I walk home.” It is as if something or someone asks for the wrongdoing to be committed (Curasi Citation2013). This subtechnique corresponds to what Schönbach’s (Citation1990) calls “the excuse of distraction”.

The final subtechnique for blaming the circumstances is to cite the existence of a “too big an opportunity” as something that limits one’s choice to act compliantly (cf. Cressey Citation1953). When using this technique, people acknowledge that they possess moral agency and have the freedom to behave compliantly but that this is threatened by extreme demands on their personal integrity. Here people are not being seduced in the sense that others are suggesting or demanding the commission of the wrongdoing. Examples of this subtechnique are “Because I could” (Murphy Citation2012), “It is available” (Hinduja Citation2007), “It was very convenient” (Rosenbaum, Kuntze, and Wooldridge Citation2011), and “That is extremely cheap” (Gruber and Schlegelmilch Citation2014).

IV. Hiding behind oneself

Instead of blaming the circumstances people can also reduce or diminish responsibility by hiding behind themselves. They suggest that they have no full control over themselves, thereby mitigating their culpability or guilt. They deny responsibility by “attributing the action to another part of the self that has been disengaged from the ‘real’ me” (Maruna and Copes Citation2005:280). Cohen (Citation2013) calls this the most radical actor adjustment. One can hide behind oneself by claiming to have imperfect knowledge, capabilities, or intentions.

10. Hiding behind imperfect knowledge

By hiding behind a lack of knowledge, people suggest that they are ignorant or are not aware of the relevant things and that therefore they cannot bear (full) responsibility. Schahn and colleagues (cited in Fritsche Citation2002) identified this as a relevant technique for neutralizing environmentally harmful behaviors. They call this “reference to lack of knowledge.” For Scott and Lyman (Citation1968), this cognitive disclaimer is the simplest denial to achieve defeasibility. One can hide behind a lack of knowledge by claiming to have imperfect knowledge of the norm, the situation, the desired behavior, of oneself or memory.

People can appeal to having imperfect knowledge of the norm that is at stake. Some examples of this subtechnique are “I really didn’t think I was doing anything wrong at the time” (Gannett and Rector Citation2015) and “I don’t know enough about fair trade – that’s why I don’t buy these products” (Brunner Citation2014). Rhodes and Cusick (Citation2002) found in their research among people having unprotected sex numerous examples of this subtechnique: “I did not know that unprotected sex carried HIV transmission risks”, “I did not know what it was all about”, and “We didn’t know what safer sex meant, it was a completely new expression.” In this regard, Rice (Citation2009) discusses the insanity defense in which people argue to be unable to determine right from wrong.

People can also appeal to imperfect knowledge of the situation, i.e., they have less or no understanding of the circumstances. Some examples are “I was not really realizing the consequences of it at the time” (Rhodes and Cusick Citation2002), “Why didn’t I see the gravity of the problem and its ethical overtones?” (Geva Citation2006), and “I did not know the weapon was loaded” (Vernick et al. Citation1999). This corresponds with what Fritsche (Citation2002) calls the reference to a lack of intentionality, when people claim that they had no information that could have guided or contradicted their behavior. This is the case when people claim to have acted in a thoughtless way or have been unaware that their behavior has contradicted the norm. The same holds for what Scott and Lyman (Citation1968) call the gravity disclaimer, where people admit to the possibility of the outcome in question but suggest that its probability is incalculable.

Another subtechnique is hiding behind the claim of imperfect knowledge about the desired behavior. People may know what the relevant norm and situation is but do not know what they have to do. They claim to not have the faintest notion about what to do, to be in the dark, and to doubt what the right course of action is. An example of hiding behind imperfect knowledge about the desired conduct comes from Priest and McGrath (Citation1970) study on the use of marijuana. One of their respondents said, “I had no reason to say no” when his friend offered him marijuana for the first time. People can argue that this lack of knowledge is due to their lack of training, experience, and/or intelligence, or due to their own perplexity (Schönbach Citation1990).

More fundamental than the preceding subtechnique is the appeal to an imperfect knowledge of oneself. People then claim to be ignorant not about things outside them but about themselves. Some examples are “I was simply absorbed in thought!” (Fritsche Citation2002), “I did not even know what I was doing” (Cavanagh et al. Citation2001) and “I blacked out” (Cavanagh et al. Citation2001). Rice (Citation2009) mentions in this regard the defense of automatism, which refers to people appealing to being on autopilot as an excuse for their deviant behavior. The defense of automatism is also described in Kooistra and Mahoney (Citation2016) as a technique where soldiers in combat may feel themselves dehumanized, lose sharpness of consciousness, and forget about their own death by losing their individuality; They act as automatons, behaving almost as mechanically as the machines they operate.

People can also try to suggest that they have imperfect memory. The difference with the first category, distorting the facts, is that with the imperfect memory neutralization, people admit that there is deviant behavior and that they cannot (fully) blame others for it. However, by claiming that they have an imperfect memory about their own role in the action, they are then trying to escape admission about their contribution. Examples are “I mean, if you think about it, it seems wrong, but you can ignore that feeling sometimes” (Cromwell and Thurman Citation2003), “I don’t know anything” (Benoit and Hanczor Citation1994), and “I think I kind of blanked out, my mind went a blank” (Cavanagh et al. Citation2001).

11. Hiding behind imperfect capabilities

People can also try to hide behind imperfect capabilities. They then claim that they are unskilled and uncontrollable. Schönbach (Citation1990) calls this technique claiming impairment of capacity. Arguments that reflect this technique are, for example, “I did not have the power,” “I could not stop myself,” and “I was uncontrollable” (cf. Hall, Howard, and Boezio Citation1986; Priest and McGrath Citation1970; Rhodes and Cusick Citation2002; Scully and Marolla Citation1984). The relevant subtechniques here are hiding behind imperfect capabilities as a human being, imperfect social and technical skills, imperfect self-restraint, imperfect self-resistance, and hiding behind imperfect self-perseverance.

The most general subtechnique used by people who hide behind a lack of capabilities is suggesting that all or most human beings do not possess the capability in question and that therefore it is reasonable that they too lack it. As Thompson and Schlehofer (Citation2007) suggest, people with an external locus of control believe that external factors determine whether people achieve their goals because their capabilities are insufficient and inadequate. Rhodes and Cusick (Citation2002) found that women excused themselves for having unprotected sex by suggesting that many women lack the capability to negotiate (“a lot of women feel intimidated that they can’t say ‘no’”). The lack of such capability on the part of women was positioned as an outcome of the general uneven distribution of power between women and men. As one HIV-positive heterosexual female reported, “If the man is not going to use a condom, there’s nothing you can do.”

People can also claim that while others may possess the capability to behave well, they themselves lack it. People then claim to have no or limited, what Thompson and Schlehofer (Citation2007) call, self-efficacy. One of its subtechniques is claiming to have imperfect skills. Schönbach (Citation1990) identified claiming a lack of technical skills as a kind of neutralization. This is when individuals claim to lack professionality, competences, experience, and craftsmanship to perform their tasks. Taylor (Citation1972) identified sexual offenders who cited defective social skills in their accounts. They claimed that they stumbled clumsily into the situation or that they were trying to engage in compliant behavior but failed. For instance, “I didn’t mean to frighten her. I was trying to ask her to come out with me.” Scott and Lyman (Citation1968) suggest that people may be inclined to position themselves as clumsy when the same type of accidents befalls them frequently.

Another subtechnique is one where people do not deny that they have the skills to behave good but they claim that inner factors override their ability to demonstrate or make use of those skills. These inner factors or conditions, such as impulses, temper, and needs, are considered to be so strong that they cannot be suppressed (Scully and Marolla Citation1984). People then claim to have an imperfect capability for self-restraint. We can find instances of these neutralizations in Taylor’s (Citation1972) study of sexual offenders: “It was my inner impulse,” “I could not break down my strong desire,” and “I was overcome by a desire.” Cavanagh et al. (Citation2001) identified in their study subjects who regularly claimed their inability to control their temper as the cause of their violent behavior. Some of the subjects described themselves as becoming a “different person”: “I lose control of myself. I know what’s happening; I can see it happening but my temper just takes over” (p. 707).

Instead of claiming to lack skills or self-restraint people can neutralize their behavior by claiming that they have not the capability to resist (big) temptations and (overwhelming) opportunities. Rhodes and Cusick (Citation2002) discussed people who claimed to lack this capability: