ABSTRACT

This article explores the boundary work of incels (involuntary celibates), to counter negative media coverage and online ridicule. Attempting to claim rational status, incels have created alternative information channels that reframe their situation of involuntary celibacy as a legitimate life circumstance. I examine the symbolic boundaries within the incel subculture, using the Incel Wikipedia page as a specialized encyclopedia for their online milieu. After describing the incel worldview and subcultural identity, I analyze how incels engage in boundary work to differentiate and solidify their status – categorizing themselves and other people. The article draws on theories of narrative and cultural criminology to present how incels negotiate their identity by establishing symbolic boundaries that exclude out-groups such as women, sexually successful men, and mainstream society. It concludes by considering how boundaries within the in-group are based on degrees of inceldom, gender, and violent actors. As a site of resistance, the boundary work of the incel wiki reveals how the social incel identity is formed and given meaning by contrast to symbolic others. I argue that narrative and cultural criminology can help us unravel the online ecosystem by analyzing the negotiation of external and internal subcultural boundaries.

Introduction

The incel phenomenon has received a lot of media attention, due to terror attacks resulting in many deaths. Dominant media narratives have led to broad generalizations about the incel community, sometimes without clear distinctions as to what degree perpetrators associate with incel ideologies, or self-identify as “incel” or involuntary celibate (Daly and Laskovtsov Citation2021; Kates Citation2021). Incels belong to a diverse subculture and continuously negotiate their identity, within the wider virtual space of the “manosphere,” which consists of numerous interest groups concerned with men’s issues and masculinity. Despite ideological differences, these groups all espouse a brand of antifeminism known as the red pill philosophy (Beauchamp Citation2019; Farrell Citation2019; Ging Citation2017).

Incels, however, stand out because their ideology, the blackpill philosophy, adopts an even more nihilistic and sexist worldview (Baele, Brace, and Coan Citation2019). Self-proclaimed incels occupy the “incelosphere” of isolated men blaming their involuntary lack of sexual and romantic success on feminism and women (Jaki et al. Citation2019; Lowles Citation2019). Their online subculture propagating misogynistic and extremist ideology has been criticized for fostering male supremacy and racism, violence and a culture of martyrdom, and even domestic terrorism (Larkin Citation2018; Lavin Citation2020; Witt Citation2020). However, few incels actually commit violent acts, and incel-inspired terrorism is rare (Hoffman, Ware, and Shapiro Citation2020). As Cottee (Citation2020: 5) points out, “most incels are law-abiding and seek out other incels online not to coordinate acts of violence but to share their experiences and stave off feelings of loneliness.” Incels mainly gather anonymously online to seek validation, community and recognition of their grievances concerning inceldom. They then find themselves the targets of ridicule, mockery and parody, as their counter-cultural rejection of mainstream norms and values often manifests itself as emotional venting, which others online find amusing, distasteful or harmful (Dynel Citation2020). Similarly, “incel” has become widely used as a mocking insult; online streaming platforms like Twitch have banned its use in “derogatory statements about another person’s perceived sexual practice or sexual morality”Footnote1 (Kastrenakes Citation2020). Seeking recognition as rational beings, incels have created alternative information channels to challenge social stigma and counter what they perceive as vilification and misrepresentation.

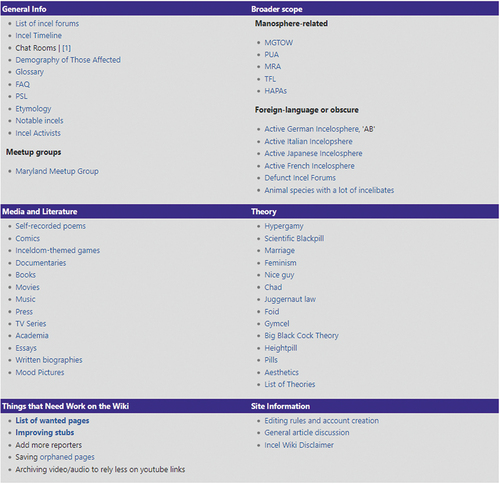

The Incel Wikipedia page is one such attempt.Footnote2 It adopts the English Wikipedia template and is an alternative specialized online encyclopedia of ideas shared by incels and gives an overview of core subjects, individuals, and activities. The wiki was created in early 2018 and now consists of over 1289 edited pages setting out the main arguments and grievances of incels. It provides detailed definitions of central theories, expressions and abbreviations related to a subculture lacking ideological and political consensus. The wiki aims to counter inaccurate media narratives by presenting involuntary celibacy not as a philosophy, movement or community, but as a “gender-neutral life circumstance” which leads to legitimate grievances.Footnote3 The incel wiki thus actively contests the notion that incels are irrational, dangerous or violent, by framing their worldview as rational, objective, and scientific.

This article uses the Incel Wikipedia to analyze how incels construct their identity by creating symbolic and social boundaries. The wiki is a site of subcultural resistance displaying the overarching narratives of the incel worldview. Drawing on theories of narrative and cultural criminology, and showing how narrative boundary constructions divide outsiders and insiders, the article seeks to reveal how the social incel identity is constructed, negotiated and maintained. Also examined is the way incels construct internal boundaries by separating authentic members from imposters or harmful others. Examining boundary work provides a more nuanced understanding of the incel phenomenon, and casts light on how members of subcultures create and negotiate meaning through identity work online.

The incel subculture

Though marginal, the incel movement is part of a wider social phenomenon of young men who feel disenfranchised in regards to men’s rights, social issues, masculinity, and loneliness (Dahl, Vescio, and Weaver Citation2015; Kimmel Citation2013; Maddison Citation1999; Regehr Citation2020). Ironically, the term “involuntary celibate” was coined in 1997 by a Canadian woman who created a website intended to be an emotional outlet for both men and women who had failed to find romantic success. Alana’s Involuntary Celibacy Project functioned as a support group for a few years until she ended her involvement and it disappeared (Beauchamp Citation2019; Ling et al. Citation2018). The incel community has by now changed considerably – from a small support group to a subculture at the extreme end of a misogynistic online movement (Bates Citation2020; Nagle Citation2017). The Internet has been essential for its development, by providing a free space that gives access to a potentially sizable audience of likeminded individuals. The absence of conflicting views has created echo rooms for discussion distribution of propaganda, and cementing ideology (Baele, Brace, and Coan Citation2019; Holt, Freilich, and Chermak Citation2017) – but has offered little hope of any answers to societal and “systemic dating problems for men” (Papadamou et al. Citation2020: 2).

Cohen (Citation1955: 12) defines a subculture as a “culture within a culture” which inverts dominant cultural values and norms to solve its members’ frustration about their status. Thus, the incel subculture adopts an inverted status system emphasizing the limitations of social and sexual inclusion. In this “wound culture,” lonely and desperate individuals gather online to share the traumas caused by inceldom (Cottee Citation2020: 9). Subcultures are often framed as being opposed to mainstream society and its social norms (Blackman Citation2014). This fosters the construction of an alternative set of values and behaviors, which appeal to marginalized groups, creating a counterculture which “strikes back” at, or provokes, mainstream audiences (Holt, Freilich, and Chermak Citation2017). Participants show attachment to their subculture by oppositional or negative behavior (Cohen Citation1955; O’Malley, Holt, and Holt Citation2020). Gelder (Citation2005) describes how subcultures embrace other forms of otherness by active detachment from mainstream society. Using subcultural capital as an ideological resource, incels inhabit a linguistic sphere of “collective symbols” – conceptual metaphors signaling “strong negative or positive demarcations” that bind the subculture together (Thornton Citation2003; Waśniewska Citation2020: 80). The Internet helps consolidate subcultural boundaries separating cultural groupings (Hodkinson Citation2003). Rather than reducing them, the online subculture transforms “what are private and practical troubles into an overarching political grievance against women” (Cottee Citation2020: 6). The incel movement can thus be seen as a deviant subculture, expressed like other countercultures, through social practices such as storytelling, rituals and customs, or artistic products such as Internet memes, GIFs, music, videogames, and films (O’Malley, Holt, and Holt Citation2020; Pieselak Citation2015).

Knowledge about incel demographics is limited, as they are dispersed across anonymous forums, but user data indicate the numbers visiting incel sites are in “the tens of thousands” (Sugiura Citation2021: 4). Self-reported surveys from the online forum “incels.co” suggest its core users are predominantly young middle-class white males. Many say they live with their parents and have never had sex or intimate contact with a woman, and eighty percent say they are from North America or Europe. Mental illness seems to be prevalent: “70% claimed to suffer from depression, while over a quarter self-identified as autistic” (Hoffman, Ware, and Shapiro Citation2020: 568). The incel demographic would seem to be heterosexual males between the ages of 21 and 33, and appear somewhat ethnically diverse, which contradicts the idea that incels are mainly white, as is often reported by the media (Jaki et al. Citation2019). However, although members vary in race and ethnicity, the incel subculture espouses ideas and preferences of heteronormativity “rooted in biological positivism and white supremacy” (Lindsay Citation2022: 217).

Previous research has studied incels in relation to masculine identity and the manosphere (Ging Citation2017; Menzie Citation2020; Witt Citation2020), networked misogyny and antifeminism online (Bratich and Banet-Weiser Citation2019; Chang Citation2020; Lin Citation2017), qualitative and quantitative analysis of incel forums (Baele, Brace, and Coan Citation2019; Ribeiro et al. Citation2020), its relevance to terrorism and security (Cottee Citation2020; Hoffman, Ware, and Shapiro Citation2020; Tomkinson, Harper, and Attwell Citation2020), and as an online subculture (Fowler Citation2021; O’Malley, Holt, and Holt Citation2020). Other studies have included the Incel Wikipedia within their methodologies (Papadamou et al. Citation2020), or analysis (DeCook Citation2021), but few have examined the symbolic boundaries within the subculture in the light of narrative and cultural criminology. The wiki is a central part of the incel online narrative and serves as a source of subcultural capital that supports resistance to the increased media scrutiny of the incelosphere. This article explores how the encyclopedia narratives establish and maintain the symbolic boundaries of out-groups and in-groups, which help shape stories, provide inspiration, and uphold behavior within the incel subculture.

Narrative criminology, cultural criminology and symbolic boundary work

Narrative criminology views “stories as instigating, sustaining or effecting desistance from harmful action” (Presser and Sandberg Citation2015a). This perspective “seeks to explain crime and other harmful action as a function of the stories that actors and bystanders tell about themselves” (Sandberg Citation2015:179); it looks at how stories shape our social world and “inspire us to do or resist harm” (Fleetwood et al. Citation2019: 1). Narrative criminology does not focus on the factuality of stories, but on “how the myriad stories people tell reflect the multilateral nature of identities, values, communities and cultures” (Raitanen, Sandberg, and Oksanen Citation2017: 3). Our narrative identity “shapes how we experience and act upon the world” not as “the outcome of agency, but rather, agency is constituted in/through narrative identity” (Fleetwood Citation2016: 184). Stories help define (counter) cultures by constructing boundaries between a “moral us and a deviant them” and include recognizable characters, such as “victim” or “villain,” to drive the plot and point to the underlying moral (Loseke Citation2007; Sandberg Citation2016). No one has used narrative criminology to study incels, and only a few have used the framework to study sexual offenses more generally. However, research within narrative criminology has shown how women sex workers experience gender violence, intersecting forms of subjugation and oppression (Boonzaier Citation2019), and how alternative narratives can instigate and sustain sex work (Poppi and Sandberg Citation2020). Narrative criminology has also highlighted the importance of stories in managing shame for sex offenders who try to make sense of themselves and their victims (Ievins Citation2019) while attempting to habilitate themselves after participating in treatment programs for sexual offenders in prison (Victor and Waldram Citation2015). Stories of sex and gender dynamics are essential for incels, and narrative criminology is especially helpful in unraveling their narrative worldview.

Cultural criminology focuses on the relationship between mediated meaning and individual experience by placing criminality and its control as cultural products in the context of culture (Hayward and Young Citation2004). In other words, it “emphasizes the centrality of meaning and representation in the construction of crime as momentary event, subcultural endeavor, and social issue” (Ferrell Citation2015: 1). Cultural criminology stresses the mediated nature of reality in late modernity and how “criminal subcultures reinvent mediated images as situated styles, but are at the same time themselves reinvented time and time again as they are displayed within the daily swarm of mediated presentations” (Hayward and Young Citation2004: 268). Individuals thus negotiate and reinvent their identity by operating within vast, loosely connected digital spaces, which are under constant external and internal critique (Ferrell Citation1999; Gal Citation2019). Cultural criminology can help capture how incels construct their own meanings by using decentralized media – their worldview is heavily influenced by reactionary gender politics, geek culture and a wider network of online misogyny (Ging and Siapera Citation2018; Nagle Citation2017; Salter and Blodgett Citation2017).

Narrative and culture are intrinsically connected: stories are used to make sense of the world (Smith Citation2005). To explain crime and violence, narrativists mainly focus on discursive retrospection, while cultural criminologists focus on “the visceral immediacy and experimental thrill of crime and transgression” (Aspden and Hayward Citation2015: 239). However, both approaches draw on social constructivist theories that view “crime and the agencies of control as cultural products” (Hayward and Young Citation2004: 259). As part of an inherently constructivist project, they share “a fundamental interest in the etiology of crime and especially the existential currents and phenomenological specificities that surround the decision to engage in or desist from offending” (Aspden and Hayward Citation2015: 239). At the same time, narrative identities are inherently reflexive as they are created at “all levels of human social life” (Loseke Citation2007: 661). This means personal narratives are not created in a vacuum, but part of larger cultural and organizational narratives: “actors draw on preexisting stories when constructing social identities” (Copes Citation2016: 196). In addition to narrative and cultural criminology, my analytical approach draws on Lamont and Molnar (Citation2002) concept of symbolic boundary work to conceptualize the categorizations negotiated within the incel subculture. This type of boundary work is examined in the light of narrative criminology, as it is important for “dramatic storytelling” (Presser and Sandberg Citation2015b: 92), and of cultural criminology to explain the negotiation of cultural and stylistic boundaries separating resources and space (see Ferrell et al. Citation2004; Hayward Citation2004).

Symbolic boundaries are defined as “conceptual distinctions made by social actors to categorize objects, people, practices, and even space. They are tools by which individuals struggle over and come to agree upon definitions of reality” (Lamont and Molnar Citation2002: 168). The concept of boundary work explains how “organizational actors define, negotiate, and perform identity-based boundaries” (Posselt et al. Citation2017: 8). Social boundaries are used to conceptualize these boundaries in reference to the “other,” which allows us to “divide the social world (and those in it) into groups and maintain symbolic boundaries among the various groups” (Copes Citation2016: 193–194). The maintenance of boundaries is not necessarily mechanical and physical, it can also be conceptual and symbolic, thus “language itself creates boundaries by providing the terms by which real or assumed behaviors and things are grouped” (Epstein Citation1992: 237). Virtual spaces have become a significant resource for collective identity formation, which consists of the “ongoing production, performance, and validation of values, codes, and norms through discourse” (Gal, Shifman, and Kampf Citation2016: 1699). Symbolic boundary-work thus captures social relationships among incels as they “compete in the production, diffusion, and institutionalization of alternative systems and principles,” while separating people into groups to generate feelings of similarity and group membership (Lamont and Molnar Citation2002: 168).

Incel ideology may represent the basis and motivation for deviant and criminal behavior, but members partaking in the subculture are not necessarily inherently deviant or criminogenic. Storytelling, however, shape and uphold subcultural identities and is important to “motivate, maintain, or restrain harmful actions” (Sandberg Citation2016: 156). The incel wiki is an edited text document, but for narrative analysis it is of “little difference if we have documents or other texts, interviews or ethnographic data” (Fleetwood et al. Citation2019: 8). Narrative criminology is used to analyze the constitutive effects of storytelling among incels and how they forge symbolic boundaries through language. Narrative scholars describe narratives as including temporality, one event follows another in time, and causality, one event caused by another, which gives meaning within a plot (Polletta et al. Citation2011). Importantly, they include characterizing people (Propp Citation1968), either metaphorically or not, that “limit the available positions subjects can take up in a discourse, and thus they influence their repertoire of action” (Presser and Sandberg Citation2015b: 91). Not all narratives are explicitly stated, and some remain unsaid or are only hinted at. Thus, the concept of tropes is used to identify familiar and dominant stories pointing to “ambiguity and dominant discourses” (Sandberg Citation2016: 155). Good stories are interpretable or already known to audiences (Polletta et al. Citation2011). Narratives can therefore be dynamic and inherently ambiguous as deviants and offenders present themselves in multiple or incoherent ways (Brookman Citation2015; Poppi and Verde Citation2021). Narrative scholars have described narratives as dialogical, multi-voiced, or elastic (Frank Citation2010; Presser Citation2008; Sandberg Citation2016). In other words, stories are fragmented and ambiguous, which “reflect not only a narrative repertoire of a particular social context but also the creative agency of the storyteller” (Sandberg et al. Citation2015: 1171). Although incel narratives can be perceived as categorical and straightforward, we should recognize their stories as manifold and complex as they include multiple ways of interpretations. In addition, cultural criminology is used to explore the mediated flow and “interplay of oppositional subcultural identity and legal authority” (Ferrell Citation2013: 261). It examines the subcultural meaning and interaction with mainstream media, government, and online actors, who position incels within the frames of crime control or domestic terrorism – the threat of incels demands social and political measures (Bates Citation2020; Lavin Citation2020; Leidig Citation2021). At the same time, incels construct their own subcultural meanings as they embrace otherness and deviance. Using alternative media strategies to re-incorporate and reference one another incels construct themselves as deviant or different from mainstream society (Nagle Citation2017). In so, mediated meanings of deviance become indistinguishable from everyday experiences (Ferrell Citation2013).

The incel community share basic stories and values that tie cultural narratives into a seemingly coherent subcultural worldview. The Incel Wikipedia is an archive of their collected knowledge, and helps compensate for a loss of online presence by establishing the origins of incel and sharing fantasies (DeCook Citation2021). This article explores the details of the incel phenomenon by analyzing how the wiki also serves as a site of resistance for incels in their efforts to avoid misrepresentation and maintain subcultural integrity by claiming rational status. They narratively engage in boundary work to distance themselves from unwanted “others,” by creating symbolic boundaries imperceptible to outsiders. In doing so they also construct different incel identities to establish the authenticity of an incel within the online subculture, because “maintaining symbolic boundaries is important for those who are socially and physically near stigmatized others” (Copes Citation2016: 197). Drawing on narrative and cultural criminology, my analysis demonstrates how the incel subculture constitute their worldview by setting boundaries for both out-groups and in-groups. This enables them to make sense of the social world, prescribe attitudes and govern behavior, and to portray themselves in culturally relevant and positive terms. The analysis speaks to the importance of boundary work online and to how fringe subcultures organize and understand themselves in terms of the wider cultural values and narratives available to them.

Methodology

This qualitative study is based on the English Incel Wikipedia (incels.wiki), which consists of 1289 pages gathered between August and October in 2020. The wiki introduces novel ideas and artistic products related to the incelosphere and describes itself as “a repository of academia, folk theories, memes, people, and art associated with involuntary celibates.”Footnote4 It has had over 16.5 million views since its creation in early 2018, and has become a central source of information for various incel websites, forums, and blogs. The incel wiki challenges the description of incels in the English Wikipedia, depicted as the “highest-profile virgin-shaming article on the world wide web;” it supposedly underwent a shift in tone and removed reliable sources between 2010 and 2018.Footnote5 This shift led to incel no longer being described as a life circumstance, but a subculture, following Angela Nagle’s BBC appearance after the van attack in Toronto 2018, by supposedly conflating 4chan culture with incels leading to further scrutiny and generalization of the community.

The wiki is a constantly evolving project, and has had 55,870 edits – an average of 13.9 per page. Editing rights are open to both incels and non-incels, but certain core individuals seem to contribute most of the content. The main content contributors are listed as 61 registered users, 3 administrators, 1 interface administrator, 3 bureaucrats, 8 trusted members and 52 automoderated users. This reflects the infighting within the larger incel community: individuals are banned from making edits, because they have violated rules and regulations, which leads to the development and expansion of different incel wikis. This study is limited to one wiki page, to the exclusion of other wikis within the incelosphere (incelwiki.org), other language offshoots (de.incelwiki.com, it.incelwiki.com or es.incelwiki.com) or earlier wikis (love-shy.com or incel.info).

The sampling of the wiki includes certain limitations, most notably its ability to fully represent incels due to ongoing disagreements within the incel subculture. The data consists of multiple symbolic meanings and linguistic representations that allow incels to selectively adopt complex, contradictory, and even changeable stories about themselves. Parts or sections of the data could thus be characterized by ambiguity. However, this paper mainly analyses the boundary work within the incel subculture with limited focus on ambiguity, which needs further investigation. In addition, the detail-oriented framing of the wiki might make it more favorable for individuals deeply invested in the incel ideology than those who only identify as “involuntary celibate.” In an effort to counter negative perceptions of incels the wiki has become a systematic and coherent information repository about and for incels (DeCook Citation2021). Previous research analyzing and identifying the belief systems on incel forums has shown similar conceptual use of in-group and out-group definitions as the wiki promotes (Baele, Brace, and Coan Citation2019; Cottee Citation2020; Hoffman, Ware, and Shapiro Citation2020; Menzie Citation2020). The wiki is an important part of the meaning construction of incels narratives, subcultural expressions and boundary work. It mirrors the discourse present on different incel forums, with the largest active forum linking to the wiki on its main page,Footnote6 where members, as well as researchers investigating incels, utilize its information to navigate and make sense of an incel worldview (Hintz and Troy Barker Citation2021; Lindsay Citation2022; Papadamou et al. Citation2020).

Data collection from the Incel Wikipedia initially focused on the subjects appearing on the main page, the pages with the most views, and in the glossary, while also following the hyperlinks found in these. This approach gave a better overall understanding of the main themes found in the pages, and of the online incel community in general. The next step of the analysis involved going through all 1289 pages in alphabetical order, to get a detailed view of the content. The data was collected by manually screenshotting each page and filing it according to theme (e.g. men, women, dating, incelosphere, manosphere, PUA, memes, literature, theories) and sub-category (e.g., “women” had the sub-categories of female types and levels, anatomy, ethnicity, action and behavior, and female personalities). The data produced 1591 files sorted into 143 categories consisting of 42 main categories and 101 sub-categories.

The analysis specifically involved identifying symbolic boundaries created by incels differentiating themselves from others, while separating themselves into different categories. Initial themes was based on narrative and cultural criminological theory, which identified narrative (e.g. characters and metaphors) and cultural (e.g. products and representations) elements. Further selection was thematically based on subcultural boundary work. Thus, the analytical categories are mainly inspired by the literature of symbolic boundary work related to in-group and out-group categorization (Lamont and Molnar Citation2002). Boundary work is closely connected to narrative and cultural theory, with narratives creating boundaries (Polletta et al. Citation2011), and culture being depended on the maintenance of boundaries (Barth Citation1998). Below I identify influential narratives and cultural frames within the incel worldview. Most importantly, my analysis show how incels create and maintain these frames through symbolic boundary work separating themselves from out-groups of women, men, and mainstream society, as well as in-groups based on degrees of inceldom, gender, and violent actors.

Findings

The first part of the analysis describes the incel worldview, encapsulated in the pill philosophy, the sexual market, and the victim identity narrative. The second, and main part, reveals nuances within the incel subculture by showing how incels engage in boundary work to distance themselves from others, or associate themselves with them. By distinguishing between “us” and “them,” incels separate themselves from an out-group, and create identity categories within the in-group. The analysis demonstrates how incels negotiate their identity through symbolic boundary work that divides off women, sexually successful men, and mainstream society. It concludes by presenting the boundaries established within the subculture based on degrees of inceldom, gender, and association with violence.

The incel worldview

Stories of love permeate our lives in novels, movies and music. In the West, the stock assumption is that “romance is natural” and it informs narratives of intimacy and love; online dating has facilitated the search for a partner (Shumway Citation2003). Incels totally reject this mainstream narrative and have adopted counter narratives based on “the pill philosophy.” Incel philosophies take the notion of being “bluepilled or redpilled” from “The Matrix,” where Neo, the protagonist of the movie is forced to choose between the blue pill that allows him to continue living in blissful ignorance, or the red pill that reveals the truth about the world. For advocates of the red pill, the “bluepilled masses” are tricked into having naïve and unrealistic expectations regarding romance and sexual relationships that are propagated by feminists:

It is the preference of believing in comforting or convenient tropes, especially when it concerns a person’s world view, with emphasis on the pretense or opinion that goes contrary to the research suggesting physical attraction plays an utmost role in social or sexual situations.Footnote7

The pill philosophy is a key part of the incel view of the current dating scene. To support this mind-set, incels have adopted a narrative of biological essentialism and developed their own blackpill philosophy based on evolutionary psychology, according to which incels are excluded from the dating pool due to their inferior genes that manifest in physical ugliness and limited social skills. This explanation often includes recognizing men as the actual victims in society because of discrimination and oppression perpetrated by women (Farrell et al. Citation2019; Wright, Trott, and Jones Citation2020). Constructing personal narratives can help make sense of confusing experiences by making “coherent connections among life events” (Loseke Citation2007: 672). Thus, incels tell a story in which they are alienated characters in a dystopian society where the truth is deliberately hidden from others. This narrative is reminiscent of Frye’s (Citation1957) archetype of classical tragedy, in which the hero is somehow separated from the natural order of things. More particularly, it belongs to the mythic archetype of irony, as it is designed “to give form to the shifting ambiguities and complexities of idealized existence” (Frye Citation1957: 223).

In the incel worldview, sex is viewed as a commodity and the ability to consume it is a measurement of success. The incel value system includes their own version of sexual economics theory (SET) that places sexual relationships within “the sexual market.” Incels, who are unable to participate in it, position themselves as rational observers of the extremely unfair situation. The redpill view is that it is possible to compensate for negative features and attract women by raising their “sexual market value” (SMV) by improving appearance, clothes, economic status etc.Footnote8 The blackpill view is that “sexual market value is mostly or entirely genetically determined.”Footnote9 It reflects culturally dominant values and is influenced by a market and consumer culture, which has made consumption “a mode of expression” (Hayward Citation2004: 4). In other words, the sexual market culture makes the “ability” to consume sex important, but this is not open to incels. Incel identity is therefore created and expressed by their total ““inability” and failure regarding sexual consumption.

Incel identity is a broad and vague term, as it applies to an amorphous group of sexless individuals. Incels are defined as “adults who fail to find a sexual partner for six months or more without choosing so,” while being “overwhelmingly rejected by the members of the sex they are sexually attracted to.”Footnote10 Rather than identifying incels as a group, ideology, subculture, organization, or movement, the wiki frames their situation as a common misfortune analogous to other negative circumstances such as poverty. However, despite their demographic and ideological differences, those belonging to the incel milieu have formed a subculture, by behaving “in ways that demonstrate their shared belief in a set of values” (O’Malley, Holt, and Holt Citation2020: 5). They position themselves within a victim narrative as a marginalized group that society systematically discriminates against because of their appearance. The narrative identity of incels has aptly been described as a subcultural “brotherhood of the shipwrecked and defeated” (Cottee Citation2020: 8).

Symbolic boundaries

Symbolic boundaries are drawn by setting oneself or one’s group against other individuals or groups, and are often used to “enforce, maintain, normalize, or rationalize social boundaries” (Lamont and Molnar Citation2002: 186). Boundary work enables marginalized and stigmatized groups to “form social identities and create positive perceptions of oneself,” and gain “a sense of agency and control of their lives” (Copes Citation2016: 207). People use the logic of boundaries to assert their own status by comparing it to that of others in a similar situation (Epstein Citation1992). For example, the concept of “status inconsistency” suggests that a person’s demographic characteristics can be interpreted within various social hierarchies (Bacharach, Bamberg, and Mundell Citation1993; Heames, Harvey, and Treadway Citation2006). Status inconsistency take place when an individual’s social position in a hierarchy conflicts with others in the group, which can result in status anxieties and frustrations that foster extreme political ideologies (Lenski Citation1954; Rush Citation1967).

The perceived mismatch in power-relations between incels and others can create strains that nurtures a deviant online subculture (Fowler Citation2021). In their ongoing narrative project, incels set up symbolic boundaries by defining not just who they are, but also who they are not. My analysis examines whom incels exclude from their subcultural in-group by telling stories enabling them to compare themselves with other people, categorize them as an out-group, and create social distance from them. As I describe below, incels establish and maintain status boundaries that separate them from (1) women, (2) sexually successful men, and (3) mainstream society. In conclusion, I deal with the boundaries they create within the subculture that are based on (1) degrees of inceldom, (2) gender, and (3) violent actors.

Boundaries excluding women

The status system of the incel subculture inverts, contests and rejects mainstream society. However, problems arise when admiration and recognition from outsiders is considered valuable (Cohen Citation1955). For incels, women are objects of both desire and contempt; they crave female validation and attraction (Glace, Dover, and Zatkin Citation2021). To resolve this problem, incels claim superiority by engaging in symbolic boundary work that changes the position of women by making them into one-dimensional characters.

The incel status system is mainly based on attractiveness, but also includes factors like income or social status. At the top of their hierarchy, is “Stacy” or “Gigastacy” – the archetypical unapproachable “blond bimbo.” Stacy is the enemy – the embodiment of female privilege that denies men access to sex. Incels also express great frustration at being ignored by women perceived as being on the same aesthetic level as themselves – “Becky” or the “female normie.” Although such women are of lower status than Stacy in terms of looks and social status, they too “ignore around 80% of men, including their looksmatches, unless said looksmatches happen to earn at least as much as she does.”Footnote11 This boundary work sees all women as manipulative, shallow, picky and demanding. Their social and sexual power enables them, as “sexual gatekeepers” to exclude men from experiencing sex, and to control them by threatening to make false rape accusations (FRA). Romantic and sexual relationships with women are thus framed as inaccessible, with sex seen as a commodity women use to manipulate men to achieve societal goods:

Adult females are a pay-to-cum, horror DDLG [Daddy-Dom-Little-Girl] roleplaying game. Due to bloatware and the increasing amount of resources required to install and maintain females, full romantic access is reserved for elite masochists. Many men have become bankrupt due to extortionate prices for temporary romantic subscriptions.Footnote12

Experiencing a form of “aggrieved entitlement,” incels feel cheated of sexual benefits that were formerly accessible to men in their position (Kimmel Citation2013). In their view, the sexual revolution of the 1960s had a negative effect on female behavior, making it “socially acceptable for girls to act like sluts, and pre-marital cohabitation and casual sex was normalized.”Footnote13 The current unregulated dating market has resulted in female hypergamy: women “marrying up in socioeconomic status.”Footnote14 Incels censoriously denounce women that explore their sexual autonomy, labeling them impure deviants, who over-indulge in sexual activity with selected men.

Humor is important in storytelling and can be used to ridicule out-group members and mark superiority and social distance (Sandberg and Tutenges Citation2019). Incels laugh at and devalue women that deviate from the traditional female ideal by not being pure, caring, and submissive. “Roastie” is used as a slur implying that female labia “become wider and longer” if women have multiple sexual partners, and eventually resemble a “roast beef sandwich.”Footnote15 The ultimate othering is expressed through the “dogpill,” an ironic version of the blackpill: the realization that “women prefer sex with dogs and other members of the family canidae over sex with incels.”Footnote16 Such misogynistic humor enhances in-group solidarity and enables incels to resist the emotional and social control women are thought to exert. It also creates out-group hostility, as these status boundaries construct women as morally and biologically inferior “others” with non-human characteristics requiring social and sexual control.

Paradoxically, incels express visceral hatred for what they most desire, vilifying unattainable women as the enemy. As Menzie (Citation2020) points out, the way incels represent themselves is “shaped and defined in relation to women as other.” The intentionally provocative framing of women involves what the subcultural theorist Cohen (Citation1955: 28) describes as “an element of active spite and malice, contempt, and ridicule, challenge and defiance.” This non-instrumental “striking back” at women and feminism enhances incels’ sense of self-worth helps them repress core existential self-doubts and uncertainties. The symbolic boundary-work thus allow incels to change their sexual failure from being an individual problem into one caused by women. Simultaneously, however, it creates social boundaries that limit incels’ approach to the women they call unclean, manipulative, irrational, or even dangerous.

Boundaries toward sexually successful men

Subcultural identities are often constructed and shaped in opposition to exaggerated cultural representations of masculinity, or hypermasculinity (Salter and Blodgett Citation2017). Incels create symbolic boundaries between themselves – “virgins” or sexual losers – and the physically attractive, sexually successful men dominating the sexual market – “Chads” or “Gigachads,” who epitomize hegemonic masculinity and dominate other forms of masculinity, who fail to reach their normative standards (Vito et al. Citation2018). As incels see it, there is an 80/20 rule whereby Chads attract eighty percent of women, thus excluding other men from the sexual market. In the face of this hegemonic masculinity, incels do boundary work to separate themselves physically and mentally from sexually successful men.

A Chad is a stereotypical tall and athletic jock whose masculine traits are emphasized by hyperbolic and parodic memes. He has “intimidating masculine features such as a square jaw, hunter eyes, pronounced cheekbones, a broad chin, and a thick neck,”Footnote17 – the prototypical “alpha male” every woman wants to have sex with. This hypermasculine identity performance creates an image of what manhood should be and the bodily requirements for men to attract female partners. Exceptions, like the “pretty boy,” serve to support these hypermasculine ideals among incels, as they reject the feminization of men by describing this male type as a “facially-aesthetic, somewhat feminine or androgynous version of a man.”Footnote18 This boundary work reinforces the cultural perception of how male bodies express “true masculinity” (Connell Citation1995), and the bodily differences between sexually successful males and incels.

Subcultural solutions to shared status problems are found by establishing new norms and criteria that make their own characteristics desirable (Cohen Citation1955). Using a gendered spectrum incels create a distinct hierarchy of political and social agency based on sexual access and desirability (Fowler Citation2021; Tranchese and Sugiura Citation2021). Chads and alpha males supposedly possess strength, charisma and authority that captivate women. Incels devalue these qualities by branding them as being required by women’s evolutionarily maladaptive and irrational sexual choices, which make them “choose men with the most sexually dimorphic traits such as cartoonishly large muscles and frame, with no selective attention paid to traits like loyalty or morality.”Footnote19 Incels position themselves as the underdog: weak, shy and submissive compared to Chads. To compensate for their lack of erotic capital, they claim they have positive characteristics such as cooperation, morality, intelligence, and empathy and nobler motives for wanting sex: unlike Chads, the “majority of incels want genuine companionship.”Footnote20 The main boundaries, however, are drawn by maligning men with erotic capital and symbolically labeling them as obnoxious, uncultured, or unintelligent brutes with immoral characteristics:

[…] it seems apparent that while personality does matter to women, it does not matter in the ways they claim. Contrary to popular claims that women want a “nice, caring guy,” in actual fact, they are most sexually attracted and aroused by narcissistic, manipulative, and psychopathic men.Footnote21

This constant boundary work frames Chads as undeserving of their sexual success because they are abusive and dangerous, and able to act as they please without consequences. High intelligence is also presented as detrimental to sexual success: incels suffer, while “especially low IQ men have more sex”Footnote22 than intelligent people of both genders.

Hegemonic masculinity creates impossible standards and expectations that can be detrimental to men’s physical and mental health (Connell Citation1995). Being unable to conform to such ideals makes incels feel powerless and frustrated. While they supposedly reject hegemonic masculinity, however, they express a deep desire to be, or become, Chads. Their unsuccessful dating life is often portrayed as illustrating the trope “nice guys finish last.” Memes featuring comparisons of portrait and profile pictures are used to show how little difference there is between the face of a Chad and that of a non-Chad. Despite its claims to a rational and scientific basis, the incel worldview involves emotions with strong moral components, including humiliation, self-righteousness, and cynicism. They speak of “a few millimeters of bone” when arguing that there is a tremendous difference in “the social and sexual advantage men (and women) with just the right facial proportion are thought to experience.”Footnote23 As in Frye’s (Citation1957: 237) tragic and fatalistic narrative archetype of irony that features “the natural cycle, the steady unbroken turning of the wheel of fate or fortune,” incels perceive their position as an unfair, but unavoidable result of having lost in the “genetic lottery.” Their narrative presents them as “destined to the life of a lonesome GDE (genetic dead end) who remains single till they are put into a coffin,”Footnote24 and expresses deep-seated bitterness at what is missed when one is “almost” a Chad. Incels have, though, created communities that attempt to conform to get round these masculine standards:

In the incelosphere Looksmaxxing is the main form of Deincelization, however some users propose other ways to escape inceldom like Moneymaxxing and increasing social reputation (Statusmaxxing). More uncommonly, some advocate radical practices like trannymaxxing (i.e. becoming a male to female transgender)Footnote25

Gender ideology and the sense of collective experience has fed into incels’ self-definition. The absence of romance, sex and masculinity make the boundaries of masculinity the boundaries of the self. Ironically, by erecting these boundaries between incel and Chad physical and mental traits, the incel worldview reproduces traditional notions of masculine gender roles that reify their perceived differences. Although incels claim to oppose hegemonic masculinity, their worldview reinforces hypermasculine stereotypes, which are often expressed as geek and hybrid masculinities (Glace, Dover, and Zatkin Citation2021). Their representation of masculine identity, or lack thereof, differentiates incel identity from that of symbolic others – sexually successful men. Incel boundary work maintains this difference by dividing the moral intellectual and the immoral physical. Thus, to counter stigma and preserve their desired self-image, incels re-position sexually successful men as behaviorally, emotionally, intellectually, and morally inferior to themselves.

Boundaries toward mainstream society

Participation in a subculture offers shared frames of reference based on similar personal experiences; outsiders are excluded (Cohen Citation1955; Gelder Citation2005). Actively setting up boundaries between themselves and mainstream society – normies, betas, anti-incels, who are perceived to ignore or persecute them – incels demonstrate close attachment to the subculture by embracing various forms of otherness (O’Malley, Holt, and Holt Citation2020).

Partaking in a deviant subculture can have a strong expressive element that involves excitement and the desire to exert control (Hayward Citation2004). The incel subculture uses countercultural expressions to create symbolic boundaries that distance them from “normies” outside the “inceldom spectrum.” They perceive themselves as fundamentally different from normies, who are incapable of understanding the issues of involuntary celibacy (Nagle Citation2017). Normies are generally framed as “bluepilled” – easily impressionable people with no capacity for independent thought, who blindly conform to the norms and peer pressure of mainstream society. Normies are othered by using the gaming label “NPC” or “non-playable character” to suggest social predictability and lack of interesting personality. As outsiders, incels position themselves as independent, rational thinkers guided by scientific data and not blinded by emotion or bias, especially in relation to how the dating market operates. Lamont and Molnar (Citation2002: 717) define boundary work as “kinds of typification systems, or inferences concerning similarities and differences” that “groups mobilize to define who they are.” Thus, incels claim to be rational, unlike ordinary people, whom they position as an anti-intellectual rabble who naively maintain the dating market, and only take notice of incels to discriminate against them.

Narrators draw on wider cultural narratives which enable them to “portray themselves as upholders of patterns of belief and followers of appropriate behaviors and others as being the opposite” (Copes Citation2016: 200). The out-group of ordinary men is thus often ridiculed by incels for being weak or desperate when they fail to meet the hegemonic standards of masculinity (Glace, Dover, and Zatkin Citation2021): they are described as “beta males,” subservient to Chads, who can only get sex through humiliating themselves when they “exchange loyalty in return for alphas not hoarding all the women.”Footnote26 Similarly, “orbiters” are desperate men hanging around Stacies, mainly on social media, hoping to win them over. This out-group contribute “to spoiling the women, inflating their self-worth and thus adopting higher standards, e.g. with regards to how expensive the courtship display should be.”Footnote27 Framed as “traitors,” they indirectly help to uphold a repressive sexual market by sacrificing their dignity, and betraying their own gender to gain sexual attention from women out of their league. Incels therefore, displaying self-control and moderation, create boundaries based on pride and self-respect, which enable them to mock other men who sacrifice such values for the sake of sex or romantic relationships. This enables incels to present themselves as having agency, self-control and stoicism, which sets them above others lacking these virtues. However, widely held symbolic boundaries can take on a “constraining character and pattern social interaction in important ways” (Lamont and Molnar Citation2002: 169). The risk of humiliation can limit incels’ own efforts to participate in the dating market, or even cause them to avoid interaction with women altogether.

The mainstream media is depicted as “bluepilled misandrist propaganda”Footnote28 which ignores male grievances and demonizes incels, ignoring scientific data that substantiates the incel worldview. The wiki lists reporters, academics, vloggers, media pages and forums considered to be “incelophobic” or “anti-incels.” Among them we find the IncelTears sub-reddit, one of the incel community’s greatest foes, which is described as “the largest anti-incel-forum.”Footnote29 It employs a form of vigilante humor to critique and disparage the incel ideology (Dynel Citation2020), by “posting screenshots of hateful, misogynistic, racist, violent, and often bizarre content created by hateful ‘incels’” (Reddit Citation2021). Incels see the forum as what Propp (Citation1968) calls “false heroes” pretending to champion altruism, feminism, and social justice, while really being hypocritical sadists that “derive pleasure from bullying” involuntary celibates.Footnote30 The screenshots and reactionary attacks on incels are portrayed as the result of the manipulation of members of the IncelTears forum by incel trolls who “often post stuff for the sole purpose of it ending up on inceltears.”Footnote31 Such “trolling” demonstrates the subcultural transmission of knowledge, skills and behavior used to decide status among the in-group of incels. Misogynistic and hateful incel rhetoric is often framed as hyperbolic humor, or pranks, and is intended to elicit reactions from anti-incels by members of the incel community trying to gain online notoriety. Sometimes humor and use of incel memes is framed as “comparable to political satire, mostly targeted at double standards in dating, [and] the lie of the patriarchy.”Footnote32 This may also include reaffirming a narrative of persecution perpetrated by “incelophobic” actors within mainstream society that conceals inceldom as a societal problem:

The incelphobe uses various tricks up their sleeve to ensure that public awareness about inceldom or its meaning remains obscure by the tactic of obfuscation around the definition of the word inceldom. Obfuscation is a form of gaslighting, and in the context of inceldom, involves the tendency to ignore, remove, falsify, or reexplain characteristics associated with involuntary celibates. The most flagrant example of obfuscation is the insistence that inceldom doesn’t exist; that involuntary celibates are just imagining their loneliness and unintentional celibacy.Footnote33

Symbolic boundaries are “employed to contest and reframe the meaning of social boundaries” (Lamont and Molnar Citation2002: 186), and by cultivating an outsider status, incels use them to reify their limited social and sexual mobility. In countering dominant media narratives, symbolic boundary work enables incels to embrace and reframe their subcultural identity. Mainstream society is framed as naïve and in denial about the dynamics of the dating market, and guilty of deliberately targeting incels. Within a narrative of persecution, incels position themselves as a marginalized group or victims of “lookism,” systematically discriminated against by a gynocentric society. By rejecting mainstream society, incels change their lowly status to that of enlightened outsiders.

Boundaries within the incel subculture

Subcultures create clear boundaries between themselves and outsiders, but internal boundaries can be just as important. Incel identity is narratively created, expressed and cemented by comparing their lack of sexual success to that of the out-groups of “others.” Incels also set up boundaries to categorize, differentiate and solidify status within the in-group. Although they have shared experience of failed sexual or social lives, not everyone suffers to the same degree or has the same opportunities to escape inceldom. Symbolic boundaries enable stigmatized individuals to present themselves as different from other unfortunates (Copes Citation2016). Incels do boundary work to negotiate the authenticity of those claiming to be involuntarily celibate, and decide whose experience of inceldom has been worse than others.’ Symbolic boundaries are used to emphasize the diversity of incels, as well as to identify inauthentic incels. The creation and maintenance of boundaries within the incel subculture is often based on (1) degrees of inceldom, (2) gender, and (3) violent actors.

To counter the perception of incels as a monolithic group, the wiki presents statistics on “the prevalence and rising trends of inceldom”Footnote34 worldwide, as well as highlighting the diversity of its community. It offers a detailed system of categorization of incels based on structural factors like ethnicity, religion, social economics and gender, together with more individual factors and personal traits like looks, sexual orientation, psychological or physical issues. Thus, as stated in the wiki, symbolic boundaries are used by incels to emphasize key factors in their inceldom:

Celibates are often divided into categories via a term preceding suffix -cel, where the precedent indicates either the reason for their sexlessness, or one of the celibate’s characteristics. There are many of these terms, and since sexual unattractiveness can be a result of many things at once, an incel can be a part of several of these categories at once. Not all these categories necessarily fixed lifelong problems and some are even self-imposed.Footnote35

Key boundaries are based on perceived degrees of inceldom and individuals’ chances of “escaping inceldom,” also known as “deincelization” or “ascension.” The degree of inceldom decides status when authenticity as an involuntary celibate is negotiated. Incels’ inverted status system rewards the negative personal traits and experiences of those identifying as “low status” or “omega.” The more unattractive or socially excluded someone is in mainstream society, the higher their status within the subculture. This narrative effort to position oneself as a low status person, and the way a racial hierarchy of attraction is established is clearly seen in the area of ethnicity. According to the “just be white theory” (JBW) women find white males far more desirable than nonwhite males, hence the racial discrimination found in the dating market. Ethnic minority incels (ethnicels) have various problems, but supposedly find their skin color contributes to their inceldom due to “the subsequent sexual racism.”Footnote36 South Asian or Indian men (currycel) seemingly have the most subcultural capital as they are both pitied and ridiculed by other incels: the archetypical unwanted sexual partner is a “5 foot 2 balding Indian janitor,” whose undesirable traits include unattractiveness, hair loss, short stature, racial inferiority, and low socio-economic status. By having, or presenting themselves as having, the lowest sexual market value, incels can claim true incel or “truecel” status:

A man so incredibly unattractive, deformed and/or neurodivergent, that no women would even consider dating him. Having a deformity, malformation, a physical anomaly, a physiological mutation, or some other abnormal aesthetic trait is said to be a key factor and trait of trueceldom.Footnote37

The accumulation of subcultural capital seemingly mitigates against escaping inceldom, but the subcultural attraction of the community can make it difficult to abandon an incel identity. As the wiki points out, “in incel communities men lose social status by ascending, so a truecel is very unlikely to give up his rank in the community.”Footnote38

However, not everyone is equally welcome within the incel subculture, even though they all have had negative experiences of inceldom. To preserve the subcultural hierarchy and the sanctity of their online space, incels police boundaries to exclude those not felt to merit the incel label: “gatekeeping and infighting about who counts as incel is common” on incel forums.Footnote39 Boundaries are based on looks, social economic status, sexual experiences, or other perceived barriers to becoming sexually active.

Although the wiki presents inceldom as a “gender-neutral life circumstance,” gender is a major boundary. Male and female sexuality are separated in a dichotomous and hierarchical worldview that usually excludes women from the in-group. Some male incels view women’s experience of inceldom as valid, while others accept it only “in extenuating circumstances such as deformity, disability, and severe mental health issues.”Footnote40 Involuntarily celibate women are framed as a myth and their sexless and solitary situation as “largely self-inflicted.”Footnote41 This is based on the trope of women’s privileged position in the sexual market, which enables them to find sexual partners just by lowering their standards. According to the “Juggernaut Law,” “most unattractive women receive a surprisingly large amount of attention from men, sometimes more attention than women of average attractiveness.” Such advantageous “sexual selection” is seen as impossible for unattractive men. This gender boundary allows most male incels to deny the existence of female celibates (femcels), by labeling them voluntary celibates (volcel), who are too picky, or dismissing them as fake incels (fakecel). This boundary policing reflects how women in male-dominated online cultures are sometimes perceived as being out to destroy, or negatively influence, the subculture (Salter and Blodgett Citation2017). Consequently involuntarily celibate women, often banned from male-dominated incel forums, have created their own online communities based on “the pink pill philosophy.”

Internal boundary work is an integral part of determining who is included in, and who is excluded from the subculture. Outsiders often view incels as potentially violent guys meeting online to rant about women and glorify mass murderers (Dynel Citation2020; Larkin Citation2018). To counter the image of incels as irrational or dangerous, a key internal boundary is the rejection of violence perpetrated by individuals self-identifying as incel. Incels therefore shun violent actors who seemingly have connections with the incel community, or who have expressed support for incel ideology. On its main page, the wiki condemns the use of violence and denies inceldom or the incel community contributes to violence:

No mass-shooters or other criminals identified by the media as “incels,” or that self-described as such, have been members of any online community explicitly devoted to involuntary celibacy. Some of these individuals had used online communities such as 4chan and PUAhate, which were not/are not communities dedicated to involuntarily celibacy.

When seeking identity and subcultural resistance, individuals might move between different groups that seem to offer what they need (Cohen 1995), engaging with mainstream social media as well as exclusive incel spaces, and participating in multiple groups online (Sugiura Citation2021). This can make it difficult to distinguish incels from other manosphere actors seeking to reassert traditional gender roles, who share ideologies, language and online spaces (Ging Citation2017; Waśniewska Citation2020; Wright, Trott, and Jones Citation2020). Incels set up boundaries between themselves and violent actors by asserting they are participants in online spaces or groups unrelated to the incelosphere, and framing them as “actual” harmful others. The Isla Vista shooter from 2014 is thus portrayed as “someone who visited a small part of the manosphere,” but “was not part of the incelosphere” as he visited a PUA forum that “had people of every celibacy status and did not self-identify as incel anywhere.”Footnote42 Similarly, pick-up-artists (PUAs) are framed as predatory fraudsters exploiting the insecurities of male incels. Boundary work thus protects the purity of the online incel milieu from contamination by harmful others. It absolves members from responsibility for violence perpetrated by individuals seemingly related to the community. Boundaries are designed to support their perception of themselves as rational, harmless, and nonviolent. The incel majority is thus marked off from those who have committed violent attacks, who are not part of the incel community, or not authentic incels.

The most important internal boundaries thus relate to degrees of inceldom, women, and violence. They reflect nuances within the subculture that are used to separate and hierarchically categorize incels, while creating meaning through a set of symbolic frames that support the authenticity of an incel identity. For insiders, negotiating and policing these boundaries also increases the sense of cultural belonging, by making distinctions or excluding inauthentic incels, often based on degrees of inceldom or gender. Similarly, violent actors are symbolically stripped of incel status, to dissociate their actions from authentic incels, to safeguard their rational and nonviolent identity.

Concluding discussion

The incel phenomenon demonstrates how traditional narratives about the search for a romantic or sexual partner have been influenced by more recent relativistic cultural politics, such as antifeminism, masculinity, and countercultural expressions. However, members of the incel subculture attach meanings to incel identity that differ from those of the wider media. Participating in internet-based subcultures provides multiple ways to construct online identities. Drawing on Rheingold (Citation1993), Sugiura (Citation2021: 5) describes incels as a “virtual community” that rather than being “a single, monolithic, online subculture” is better understood as “an ecosystem of subcultures, some frivolous, others serious.” Examining symbolic boundary work helps understand this online ecosystem by identifying the nuances in a seemingly homogenous group of misogynists. Drawing on narrative and cultural criminology I have attempted to show the importance of boundary work in online subcultures, by describing how incels construct and maintain symbolic and social boundaries between themselves and others, and among themselves. Serving as a site of resistance, the boundary work in the Incel Wikipedia page reveals how incel social identity is formed and given meaning, in opposition to symbolic others.

The anonymity of the internet means members of online subcultures are subjected to little social control, unlike in-life (Copes Citation2016) or street-based subcultures (Sandberg and Pedersen Citation2011). Incel subcultures include multiple voices invoking wider cultural values and narratives when describing individual experiences of social and sexual exclusion. The incel wiki clearly shows the cultural bricolage that binds them together: myriad products, phrases and stories are encapsulated in the pill philosophy, the sexual market, and the victim narrative. It enables an incel persona to be put together using a pool of information from which individuals can choose material to customize a legitimate incel identity. This makes incel subcultures highly variable: members strongly disagree about status, which is conferred by sexual disadvantages, and this makes it difficult to decide whether someone belongs to certain in-groups. Narrative and cultural criminology can help unravel these uncertainties by exploring the “ongoing and contested negotiation of meaning and identity” (Ferrell et al. Citation2004: 4).

Narrative criminology views stories and storytelling as central to the creation of social identities that guide future action, as they are “essential elements of culture that people use to interpret and justify behavior” (Copes, Hochstetler, and Ragland Citation2018: 176). Cultural criminology “stresses the mediated nature of reality in late modernity” and focuses on the reinvention of image and style within subcultures (Hayward and Young Citation2004: 268). The concept of symbolic boundaries is central to both frameworks, which in combination can show how boundaries among incels are “shaped by context, and particularly by the cultural repertoires, traditions, and narratives that individuals have access to” (Lamont and Molnar Citation2002: 171). Creating subcultural boundaries involves setting external boundaries that exclude outsiders, as well as maintaining important internal dividing lines.

The way symbolic boundaries are negotiated makes clear grievances that exist among incels and offers similar frames of references within a larger online ecosystem. It enables incels to link personal traits, values, and experiences to wider cultural narratives to make coherent personal narratives. Incels mainly ascribe their lack of sexual success to external or environmental factors, rather than to their own faults: thus incels differ from the rest of society, and set boundaries to exclude immoral outsiders. Women, sexually successful men and actors of mainstream society are symbolically identified as others who ignore or persecute incels. Internal boundaries determine status among themselves and reveal who lacks the subcultural capital to be a genuine incel. Using the criteria of perceived degree of inceldom, gender and use of violence, incels separate authentic members from imposters or harmful others who might contaminate or damage their online space. This boundary work is essential, enabling incels to make sense of the world by creating opposition to symbolic others, both outside and inside the subculture, and to construct a status system that rejects mainstream values and norms. The wiki reflects how the incel brotherhood is based on shared narratives of resistance featuring emotional, moral and intellectual superiority to symbolic others.

Even though incel ideology promotes categorical and deterministic answers for the lack of romantic or sexual success, the online subculture allows for ambiguous interpretations, negotiations, and management of an incel identity. This article has utilized a clear-cut distinction of boundary work between in-group and out-group. However, future studies should also discuss the role of ambiguity as the incel worldview consists of a complex narrative repertoire of multiple, contradictory, and even changeable stories. Thus, the incel wiki’s attempt to counter media narratives has certain limitations. As an informational hub created by and for incels, it seeks to establish power and order, and it is also a correctional tool on incel forums (DeCook Citation2021; Lindsay Citation2022). Its symbolic boundary-work, however, is an ongoing process of meaning-making lacking rigid or objective frames, and the wiki does not represent how all incels see themselves, or how they understand the term incel. Although they explicitly reject violence, the counter narratives can still foster harm or be criminogenic. In cementing their boundary constructions, the wiki can, as DeCook (Citation2021: 240) points out, be a “double-edged sword” increasing hatred by bolstering incel ideologies. However, the incel wiki, and others, sheds light on details of ongoing narrative struggles, made apparent by their opposition to incel subcultures that are generally overlooked. By limiting our focus to the most controversial and sensational parts of the incelosphere, we risk exaggerating the incel threat, and possibly overlook other influences.

The stories told by incels online are not created in a vacuum. Members of online subcultures create meaning within a multifaceted universe influenced by existing cultural values and narratives. To fully understand the incel phenomenon we need to study the multitude of voices shaping the community. Their use of boundary work displays their own understanding of the world, self-portrayal, and efforts to include and exclude.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Sveinung Sandberg, Lisa Sugiura, and the anonymous reviewers for their guidance and helpful comments on earlier versions of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jan Christoffer Andersen

Jan Christoffer Andersen is a doctoral research fellow at the Department of Criminology and Sociology of Law, the University of Oslo. He has a master’s degree in criminology from the same department. His research explores trends, narratives and radicalization within the incel community by focusing on everyday stories, stigma and the subcultural characteristics of the incel culture online.

Notes

1 See the guidelines for Twitch at https://www.twitch.tv/p/en/legal/community-guidelines/harassment/20210122/.

2 For others see e.g. incel.blog.

3 The Incel Wikipedia was accessed via the web page: https://incels.wiki and differs from other incel wikis (e.g., incelwiki.com or other language offshoots). The encyclopedia is thematically separated into content pages with references as presented on this web page. They are unedited and include grammatical errors, typo-graphical errors, etc. References that do not indicate something else are taken from the Main Page, while other references will include the title of the content page in a foot note.

4 Content page: About.

5 Content page: Wikipedia Incel article.

6 Incels.is (formerly known as incels.co or incels.me).

7 Content page: Bluepill.

8 Content page: Sexual market value.

9 Ibid.

10 Content page: Incel (their highlights).

11 Content page: Becky.

12 Content page: Women.

13 Content page: Sexual revolution.

14 Content page: Hypergamy.

15 Content page: Roastie.

16 Content page: Dogpill.

17 Content page: Chad.

18 Content page: Pretty boy.

19 Content page: Fisherian runaway.

20 Content page: Incel.

21 Content page: Dark triad.

22 Content page: IQ (their highlights).

23 Content page: Few millimeters of bone.

24 Content page: Truecel.

25 Page content: Looksmaxxing.

26 Content page: Beta male.

27 Content page: Causes of inceldom.

28 Content page: Fakestream.

29 Content page: Anti-incels.

30 Content page: Inceltears.

31 Content page: IncelTears.

32 Content page: Anti-incels.

33 Content page: Incelphobe.

34 Page content: Demographics of inceldom.

35 Page content: Incel.

36 Content page: Ethnicel.

37 Content page: Truecel.

38 Content page: Deincelization.

39 Content page: Incel.

40 Content page: Sexual selector.

41 Content page: Femcel.

42 Content Page: Elliot Rodger.

References

- Aspden, Kester and Keith J. Hayward. 2015. ”Narrative Criminology and Cultural Criminology.” in Pp. 235–59 in Narrative Criminology, edited by L. Presser and S. Sandberg. New York: University Press

- Bacharach, Samuel B., Peter Bamberg, and Bryan Mundell. 1993. ”Status Inconsistency in Organizations: From Social Hierarchy to Stress.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 14 (1):21–36. doi:10.1002/job.4030140104.

- Baele, Stephane J., Lewys Brace, and Travis G. Coan. 2019. ”From “Incel” to “Saint”: Analyzing the Violent Worldview Behind the 2018 Toronto Attack.” Terrorism and Political Violence 33 (8):1667–91. doi:10.1080/09546553.2019.1638256.

- Barth, Fredrik. 1998. Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: The Social Organization of Culture Difference. Long Grove: Waveland Press.

- Bates, Laura. 2020. Men Who Hate Women: From Incels to Pickup Artists. The Truth About Extreme Misogyny and How It Affects Us All. London: Simon & Schuster.

- Beauchamp, Zack. 2019. “Our Incel Problem.” Vox, April 23. Retrieved January 09, 2021. (https://www.vox.com/the-highlight/2019/4/16/18287446/incel-definition-reddit).

- Blackman, Shane. 2014. ”Subculture Theory: An Historical and Contemporary Assessment of the Concept of Understanding Deviance.” Deviant Behavior 35 (6):496–512. doi:10.1080/01639625.2013.859049.

- Boonzaier, Floretta. 2019. ”Researching Sex Work. Doing Decolonial, Intersectional Narrative Analysis.” in Pp. 467–91 in The Emerald Handbook of Narrative Criminology, edited by J. Fleetwood, L. Presser, S. Sandberg, and T. Ugelvik. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited

- Bratich, Jack and Sarah Banet-Weiser. 2019. ”From Pick-Up Artists to Incels: Con(fidence) Games, Networked Misogyny, and the Failure of Neoliberalism.” International Journal of Communication 13 (25):5003–27.

- Brookman, Fiona. 2015. ”The Shifting Narratives of Violent Offenders.” in Pp. 207–34 in Narrative Criminology, edited by L. Presser and S. Sandberg. New York: University Press

- Chang, Winnie. 2020. ”The Monstrous-Feminine in the Incel Imagination: Investigating the Representation of Women as “Femoids” On/R/Braincels.” Feminist Media Studies 22 (2):1–17. doi:10.1080/14680777.2020.1804976.

- Cohen, Albert. 1955. Delinquent Boys: The Culture of the Gang. New York: The Free Press.

- Connell, Robert William. 1995. Masculinities. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Copes, Heith. 2016. ”A Narrative Approach to Studying Symbolic Boundaries Among Drug Users: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis.” Crime, Media, Culture 12 (2):193–213. doi:10.1177/1741659016641720.

- Copes, Heith, Andy Hochstetler, and Jared Ragland. 2018. ”The Stories in Images: The Value of the Visual for Narrative Criminology.” in Pp. 175–96 in Narrative Criminology, edited by L. Presser and S. Sandberg. New York: University Press

- Cottee, Simon. 2020. ”Incel (E)motives: Resentment, Shame and Revenge.” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 44 (2):565–87. doi:10.1080/1057610X.2020.1822589.

- Dahl, Julia, Theresa Vescio, and Kevin Weaver. 2015. ”How Threats to Masculinity Sequentially Cause Public Discomfort, Anger, and Ideological Dominance Over Women.” Social Psychology 46 (4):242–54. doi:10.1027/1864-9335/a000248.

- Daly, Sarah E. and Albina Laskovtsov. 2021. ”“Goodbye, My Friendcels”: An Analysis of Incel Suicide Posts.” Journal of Qualitative Criminal Justice and Criminology. doi:10.21428/88de04a1.b7b8b295.

- DeCook, Julia R. 2021. ”Castration, the Archive, and the Incel Wiki.” Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society 26 (2):234–43. doi:10.1057/s41282-021-00212-w.

- Dynel, Marta. 2020. ”Vigilante Disparaging Humour at R/IncelTears: Humour as Critique of Incel Ideology.” Language & Communication 74:1–14. doi:10.1016/j.langcom.2020.05.001.

- Epstein, Cynthia Fuchs. 1992. ”Tinkerbell and Pinups: The Construction and Reconstruction of Gender Boundaries at Work.” in Pp. 232–57 in Cultivating Symbolic Differences and the Making of Inequality, edited by M. Lamont and M. Fournier. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press

- Farrell, Tracie, Miriam Fernandez, Jakub Novotny, and Harith Alani. 2019. “Exploring Misogyny Across the Manosphere in Reddit.” Proceedings of the 10thACM Conference on Web Science, Boston. 87–96.

- Ferrell, Jeff. 1999. ”Cultural Criminology.” Annual Review of Sociology 25 (1):395–418. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.25.1.395.

- Ferrell, Jeff. 2013. ”Cultural Criminology and the Politics of Meaning.” Critical Criminology 21 (3):257–71. doi:10.1007/s10612-013-9186-3.

- Ferrell, Jeff. 2015. ”Cultural Criminology.” in The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology, edited by G. Ritzer. 10.1002/9781405165518.wbeosc171.pub2.

- Ferrell, Jeff, Keith Hayward, Wayne Morrison, and Mike Presdee. 2004. Cultural Criminology Unleashed. London: The Glass House Press.

- Fleetwood, Jennifer. 2016. ”Narrative Habitus: Thinking Through Structure/Agency in the Narratives of Offenders.” Crime, Media, Culture 12 (2):173–92. doi:10.1177/1741659016653643.

- Fleetwood, Jennifer, Lois Presser, Sveinung Sandberg, and Thomas Ugelvik. 2019. The Emerald Handbook of Narrative Criminology. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Fowler, Kurt. 2021. ”From Chads to Blackpills, a Discursive Analysis of the Incel’s Gendered Spectrum of Political Agency.” Deviant Behavior 43 (11):1–14. doi:10.1080/01639625.2021.1985387.

- Frank, Arthur. 2010. Letting Stories Breath: A Socio-Narratology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Frye, Northrop. 1957. Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays. Princeton: University Press.

- Gal, Noam. 2019. ”Ironic Humor on Social Media as Participatory Boundary Work.” New Media & Society 21 (3):729–49. doi:10.1177/1461444818805719.