ABSTRACT

This paper documents a case study of how academics can use traditional research and non-traditional knowledge mobilization to improve the dissemination of findings related to stigmatized communities. The International Anthropomorphic Research Project (IARP) used peer-reviewed scholarship to challenge pervasive media misconceptions and misinformation about furries. Finding the reach of traditional academic outlets was inadequate to meaningfully impact mainstream misconceptions, we rebranded our research efforts under the name Furscience and utilized social marketing and creative dissemination to repackage the IARP’s research into more public-friendly, accessible formats. Furscience has become a multi-purpose platform specifically engineered to forge connections among academics, furries, the public, and media. It also supports the furry community’s own diverse, anti-stigma efforts by providing data, public education, and partnerships. We offer preliminary evidence that suggests Furscience has increased its public reach and that furries, themselves, see improvements in how the media and public understand their community. This case study offers academics who work with stigmatized populations—especially those plagued by misinformation—and engage in translational research an example of how data, community and media partnerships, and non-traditional dissemination strategies can improve research accessibility and anti-stigma efforts. We conclude with a summary of the lessons learned by Furscience.

Main introduction

Misinformation is the fertilizer that facilitates a stigma’s growth. It is defined as “erroneous or misleading information to which the public may be exposed, engage with, and share” (Calo et al. Citation2021: par. three). In discussing the vast consequences of misinformation for health, Schiavo (Citation2021: 269) states that not only is it a problem for health behaviors (e.g., vaccine uptake), but “misinformation is also the very culprit through which stigma and discrimination are being perpetuated across time, issues, geographical regions, and groups.” As such, combatting misinformation, especially as it relates to stigmatized groups and behaviors, is a growing concern in modern society. Consequently, developing strategies for researchers to dispel misinformation and inform or correct the popular narrative is needed (e.g., Heijnders and Van Der Meij Citation2006).

However, researchers can face challenges when attempting to study stigmatized populations or deviant topics. The rarity of the phenomenon, lack of access to the population, and the (un)willingness of participants to interact with researchers can prohibit research success—especially if participants have experienced exploitation or misrepresentation. Compounding these challenges, researchers who attend to “unusual” or deviant topics that do not fit neatly into more traditional scholarship may face difficulties with their own institutions taking the work seriously, experience setbacks when trying to publish the findings in peer-reviewed journals, and struggle to obtain funding to support their research. Moreover, conducting and translating research with the goal of reducing stigma can be further complicated when academics include advocacy as part of their scholarship and dissemination practice, as they may face institutional and/or political barriers (e.g., Gardner et al. Citation2021). As such, studying stigmatized groups can sometimes be stigmatizing for the researchers, too, potentially stymieing exploration into important new areas of inquiry.

Even when the population is not stigmatized or the topic not deemed deviant, a long-recognized challenge in many academic fields—including psychology, social work, education, health, and criminal justice—involves translating academic research into meaningful and practical applications, policies, and procedures (e.g., Fudge et al. Citation2016). Various disciplines have adopted unique language and concepts to describe this phenomenon. In clinical psychology, therapists’ failure to incorporate results from clinical research into their therapeutic practice is referred to as the scientist-practitioner gap (Cautin Citation2011; Sobell Citation2016), and in the field of criminal justice, the attempt to translate research findings into policies and procedures—Translational Criminology—has been explored extensively. For example, in their discussion of the challenges of implementing evidence-based policies in policing, Nichols et al. (Citation2019) argue that the main barrier is no longer the mere existence of evidence-based research findings, but rather, the problem lies in the implementation of that evidence. Obstacles include lay persons’ difficulties in understanding scientific results, researchers’ use of jargon, the length of time it takes for scientific results to be generated, problems of knowledge dissemination, practitioners’ and policy makers’ lack of access or interest in the academic journals where researchers typically disseminate their information, the establishment of trust among various stakeholders, and the appeal of emotion over rational thought (e.g., Laub Citation2012; Robinson Citation2013).

If the goal is to effectively reduce stigma and change public perception based on evidence-based findings, then one strategy might include modifying knowledge mobilization tactics to increase the likelihood of researchers’ work being discovered by a curious public and media when they seek out information. Taken together, it is important to explore new ways for academics to study stigmatized or deviant topics, counter misinformation, and increase their dissemination of evidence-based findings to the public.

A case study: studying deviant or stigmatized topics and communities

This article represents a case study of how our research team overcame the scholarly challenges associated with investigating a highly stigmatized community—furries. Most people have never heard of furries. For those who have, their information has likely come from—or been influenced by—misinformed media, rooted in sensationalistic portrayals of furries as sexual deviants.Footnote1 In the absence of better information, the media have often reported popular narratives, anecdotes, and stereotypes that shape public perception and stigmatized the furry community, also known as the furry fandom. When our small group of interdisciplinary academics—called the International Anthropomorphic Research Project (IARP)—began its research on anthropomorphic studies in 2006, there was a dearth of peer-reviewed information available on furries. Subsequently, the original goal of the IARP was to assess the veracity of stigmatizing media representations. The data did not support the sensationalistic narratives and led to the first peer-reviewed paper on furries in the social sciences (Gerbasi et al. Citation2008).Footnote2 For the next decade, the IARP compiled data on the furry community by building trust and engaging tens of thousands of furries in qualitative and quantitative research projects—both online and in-person at furry conventions. As a result, the IARP published several dozen peer-reviewed papers and chapters on the furry fandom and comparison groups.Footnote3

However, as a research team, we were frustrated by the limited influence of the resulting peer-reviewed papers. While education can be an effective strategy for reducing stigma (e.g., Corrigan et al. Citation2012), the inability to reach the very people who needed this information most urgently unearthed deficits in these more traditional approaches to knowledge dissemination. As such, the IARP rebranded as Furscience and utilized elements of social marketing (e.g., Collins Citation2014; Grier and Bryant Citation2005) and creative education to repackage the IARP’s scholarship into more public-friendly, accessible formats. Consequently, Furscience’s research and unique dissemination approaches became one tool to support community capacity building (e.g., Chaskin Citation2001) in the furry fandom, where furries engage in their own unique efforts and advocacy to destigmatize their community and correct the record.

This paper will offer academics of varied backgrounds insights into overcoming some of the challenges associated with studying stigmatized topics (e.g., health) or (presumed) deviant communities and the challenges encountered more broadly in translational research. We do this by detailing the evolution of Furscience and then extracting the generalizable lessons learned. The paper begins with an overview of the historical misconceptions of furries and the resulting impact of stigmatizing media portrayals on the community; this is followed by an evidence-based review of the furry fandom. The literature review not only documents the extent of stigma faced by the furry community as they were cast as sexual deviants, but it also contextualizes the immense challenge of this anti-stigma work. Next, we describe the methods used to extend the reach of our peer-reviewed scholarship. We review the creation of Furscience as a dissemination tool, the expansion and integration of dissemination platforms, and the value of adding a Communications and Creative Director to the team. We discuss how the visibility of Furscience improved relations with participants and helped us forge new partnerships with the furry community. We then present preliminary analyses of the cumulative effectiveness of Furscience dissemination strategies via website traffic and Google rankings. We conclude with a discussion of lessons learned from more than 15 years of engaging in challenging research that may possibly be applicable to diverse areas of inquiry, be of value to researchers, communities, or organizations that implement evidence-based policies, and contribute to other areas of translational research.

Identifying and understanding the problem

Researchers benefit from having a strong grasp of the existing misinformation or misconceptions related to a group or topic because this knowledge permits nuance in conversation when attempting to correct the record.Footnote4 As it relates to the example of anthropomorphic identities, in our experience, understanding the ubiquity of negative sentiment and acknowledging those sources has helped make misinformed people more receptive to taking in new (evidence-based) information. We begin our story by describing some of the misinformation related to furries and then take the opportunity to educate a willing audience with data—something that is customary practice for our research team.

Stigma: media portrayals and misconceptions of the furry fandom as sexual deviants

Much of the public is unfamiliar with the furry fandom, and, historically, the more accessible forms of information were often entrenched in misinformation, which led to negative impressions of furries (Roberts et al. Citation2016). In particular, the early 2000s bore witness to several inflammatory media portrayals of furries that implied they were sexual deviants. For example, one of the first ways that some of the public came to “know” furries was through an article published in Vanity Fair called Pleasures of the Fur (Gurley Citation2001). Prominently displayed on the cover was the hook line, “‘HEY, THAT STUFFED CHIPMUNK IS TURNING ME ON!’ Inside the bizarre sex fetish world of ‘plushies’ and ‘furries’” (see Vanity Fair, March 2001). Two years later, CSI: Crime Scene Investigation released an incendiary portrayal of furries. The episode “Fur and Loathing” included an exaggerated and misleading depiction of a sexually deviant furry convention, references to furpiles (erroneously described as furry orgies), a fashion show with sexualized fursuits, and the character Sexy Kitty, who refused to remove her fursuit head for the police (Zuiker, Jerry, and Lewis Citation2003). Neilson Ratings reported 27.3 million people watched CSI the week “Fur and Loathing” was released. It was the most viewed prime time show in the USA and outperformed Survivor (20.8 M viewers), ER (19.9 M viewers), and Friends (19.4 M viewers) (The Associated Press Citation2003). There are many other documented examples of stigmatizing, anti-furry sentiment, including Second Life, where furries could be disemboweled and sent to a furry death camp (Brookey and Cannon Citation2009), the TV show Hannibal (Fuller, Jeff, and Michael Citation2014), which contained an episode with a mentally ill therianFootnote5 serial killer, and 1000 Ways to Die, which portrayed a fatal attempt by a furry to copulate with a bear (McMahon and Raee Citation2009).

These kinds of negative portrayals have had a lasting, stigmatizing impact on the public’s perception of the furry fandom. Deviance scholars have argued that misrepresentations, such as the one depicted in the infamous CSI episode, “appears to have been influential in introducing many outsiders to the furry community and perpetuating incorrect and harmful stereotypes, which in turn appears to impact the community” (Eller, Lax, and De La Torre Citation2020: 254). Indeed, research shows that when the public knows anything about furries, the impression is often highly unfavorable. For example, Roberts et al. (Citation2016) examined the attitudes of fantasy sport fans toward furries, bronies,Footnote6 and anime fans using a feeling thermometer test.Footnote7 They were asked two questions, one that measured the favorability ratings of the typical fantasy sport fan toward other fan groups and one that assessed their own favorability of the fan groups. The researchers found that while fantasy sport fans viewed anime fans negatively,Footnote8 they viewed bronies and furries even more negatively.Footnote9 Moreover, Reysen and Shaw (Citation2016) found that, out of 40 different fan groups, furries were among the most negatively viewed.

Consequently, furries are often afraid to disclose to others this important part of their furry identity.Footnote10 Roberts et al. (Citation2015b) found that furries fear ostracism from a public that does not understand their interest, and a 2018 study found many furries reported that “no one knows” about their furry fandom participation in their family (33.4%) or in their day-to-day life (45.8%; Furscience Citationn.d.-a). As a result, many furries have shied away from the media for fear of being made out—mistakenly—to be zoophiles (sexually attracted to animals), plushophiles (sexually attracted to stuffed animals), or pedophiles (Plante et al. Citation2016). However, after years of academic research and studying more than 30,000 furries worldwide, the IARP has found little corroborating evidence that the furry fandom is the cesspool of debauchery intimated by some (e.g., Bieszad Citation2018). The research did find, however, that the furry fandom is where many marginalized people find refuge and can be their most authentic selves (Mock et al. Citation2013).

#getthefacts: facts of the furry fandom

There is no “central group” that runs the furry community; it is a decentralized fandom that, rather than being centered around a single piece of canon content provided by a single author (e.g., Star Trek fans, also known as Trekkies or Trekkers), is instead built around thousands of small, independent content creators. Some furries engage with the community exclusively in online forums, while others meet up in-person at local furmeets (Plante et al. Citation2016). A smaller proportion of furries attend conventions, which can range in size from a few hundred attendees to more than 10,000. These conventions were once predominantly held in North America and Europe, but there are growing numbers of conventions in South America, Asia, and the Pacific, and, in 2019, more than 95,000 (non-unique) furries attended conventions—a twofold increase compared to 2014 (WikiFur Citation2020).

Contrary to the pervasive public misconceptions, the most distilled description of furries is simply people who are interested in anthropomorphism—giving human characteristics to animals (e.g., a bipedal, talking animated animal character; Plante et al. Citation2015). At its core, the furry fandom is defined by its creation of original anthropomorphic media, friendship, and fierce defense of inclusion and social equality (Brooks et al. Citation2022). Among the most universal, recognizable, or distinguishing features of the furry fandom is that most furries—about 95%—will create a fursona, which is an avatar-like representation of self that is imbued with positive characteristics (Reysen et al. Citation2020). Furries use their fursonas to engage with others in meaningful ways, such as practicing social interactions or imagining their fursonas in various kinds of situations and engaging in self-discovery. As such, fursonas are often safer ways for furries to participate in identity exploration and can aid in processing vulnerable elements of the persona, such as sexual orientation or gender identity (Plante et al. Citation2016). In fact, many furries experience significantly less anxiety when they think of themselves as their fursona (in contrast to their persona), suggesting that the fursona can be useful in mitigating mental health stresses (Furlong Citation2016). All things considered, the documented experiences of the furry fandom are markedly different—more positive—than many early media depictions.

Intersections of stigma within a stigmatized group

While the fandom has a long history of dealing with negative public sentiment (Roberts et al. Citation2015b, Citation2016), many furries also face additional stigmas. Furries, on average, have histories of being bullied at all stages of life that are significantly more extensive than non-furry samples (Plante et al. Citation2016; Reysen et al. Citation2021). More than 70% of furries are part of the LGBTQ+ community (Plante et al. Citation2015), at least 12–17% identify as transgender (Roberts et al. Citation2020),Footnote11 and between 4–15% are on the autism spectrum (Fein et al. Citationn.d.; Reysen et al. Citation2018).

A large body of non-furry research points to many complex challenges of dealing with multiple intersections of stigma and the impact it can have on mental health and wellbeing (Sharratt et al. Citation2020; Stutterheim et al. Citation2016). However, despite many furries facing histories of extensive marginalization and discrimination (e.g., sexual orientation; Roberts et al. Citation2020), bullying (Reysen et al. Citation2021), and significant social stigma (Reysen and Shaw Citation2016; Reysen et al. Citation2017), the furry fandom provides a haven for its members and allows for individual and community resilience (Roberts et al. Citation2015b). In fact, the research indicates furries’ recreational connection with similarly minded peers has tremendous benefits, such as improved self-esteem and life satisfaction (Mock et al. Citation2013). Moreover, self-reported accounts of wellbeing find that furries have fewer mood disorders and less anxiety than comparison groups (Reysen et al. Citation2018).

The challenges of researching stigmatized or deviant communities

The previous sections offer insights into the reality of the furry fandom—details that refute much of the public misinformation about this stigmatized community that cast them as deviants. However, conducting and publishing this research came with some challenges, and during the early years, the IARP faced its share of academics who dismissed the scholarship out of hand. In some ways, the research itself could be considered deviant—not because of its methodology, but because some academics scoffed at the topic itself. Some of the early publications and grants were difficult to secure, but the team leveraged opportunities from these struggles.Footnote12 After achieving the first yeses, it became easier to garner subsequent acceptance in traditional scholarship outlets. Seed grants were used to justify larger funding applications, and by 2013, the IARP was able to secure its first grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC).

Methods

When peer-review is not enough: the IARP and the rebrand to furscience

Despite this growing body of peer-reviewed research published by the IARP and other scholars (e.g., Bryant and Forsyth Citation2012; Deshotels and Forsyth Citation2020; Kington Citation2015; Satinsky and Nicole Green Citation2016) demonstrating the benefits of the fandom to its members, the media continued to represent furries as deviants (e.g., Stewart Citation2016; Swerdloff Citation2016). In spite of data which actively contradicted popular accounts, the findings themselves were insufficient to sway public opinion. In response, the IARP decided to step beyond the confines of traditional academic dissemination methods (i.e., peer-reviewed publications and academic conferences) and strategically rebranded to Furscience in 2016. Furscience is not a furry organization but, rather, sits adjacent to the furry community as a dissemination tool that provides evidence-based information for furries and non-furries alike. While traditional scholarship remains the foundation of the IARP, Furscience’s non-traditional dissemination strategies increased the research team’s visibility in the public sphere. Consequently, this strengthened the IARP’s visibility and connection with the furry fandom and led to new and exciting Furscience-community partnerships that were guided by mutual, destigmatizing goals—to educate the public on the facts of the fandom. Importantly, Furscience does not serve as public relations (PR) for the furry fandom and rejects that characterization. Rather, our peer-reviewed scholarship can help correct the mainstream record through effective science communication.Footnote13

When studying a stigmatized group, it is crucial to demonstrate that the researchers understand the community. The moniker, Furscience, achieves this by emulating a specific furry-based nomenclature, which appreciates pun-based inclusions of “fur” into convention names,Footnote14 furry-specific paraphernalia (such as fursuits), or the aforementioned characteristics of fursona for persona. The Fur + Science compound construction signals to the fandom that this is not only real science, but real science that seeks to understand the nuances of the fandom specifically—a nuance that could only come from researchers who have actually attended furry conventions and know furries.Footnote15 While there was some pushback by some academics who expressed the opinion that the platform’s name and research lacked seriousness, overall, the strengthened connection to the furry community and increased visibility far outweighed the naysaying, and, ultimately, the record of research productivity and successful grant applications shielded the team from the brunt of such criticism.

Branding and platform

An essential part of the team’s anti-stigma efforts necessitated careful attention to the subtleties of information dissemination—ones that are often overlooked and sometimes unappreciated by some academics. Furscience’s adherence to professional and consistent branding was critical to developing a successful, non-traditional research dissemination strategy. To help shape and achieve the IARP’s dissemination vision for Furscience, the team acquired a dedicated Communications and Creative Director (CCD). With more than a decade of experience in advertising, the CCD played an indispensable role in overseeing the branding transition to Furscience, such as supervising the hiring of a local agency that designed and maintained the website. The CCD also ensured the team’s vision was represented in the Furscience logos (e.g., Aaker Citation2012). The Furscience wordmark (see ) is a stylized typeface with a tail and ears, uses the AlternateGothic2 BT font, and is typically displayed in orange and gray, but is also used in black and reversed (i.e., white) for specific media applications (e.g., survey headers, tablecloths, pencils, lanyards, T-shirts). The tail and ears-based logo strengthened the uniqueness of Furscience’s brand identity (Aaker Citation2012) with an intentional move away from the paw print, which is associated with the furry fandom but presented a problem of potential brand confusion because it is associated with bumper stickers and other symbols used to identify dog/pet ownership.Footnote16 An IARP/Furscience hybrid logo (), which was designed by the CCD, adopted brand-consistent elements of the wordmark and is useful for Furscience’s social media profile pictures, branded buttons, et cetera, fostering brand consistency.Footnote17

Figure 1. Furscience branding projects 1a: furscience wordmark/logo. 1b: furscience/IARP hybrid logo 1c: furscience convention booth 1d: furloose parody 1e: the furry bunch parody 1f: just like you*

Brand consistency (e.g., Kenyon, Elisavet Manoli, and Bodet Citation2018) requires attention to these kinds of details that most people do not consciously consider but, as consumers of media and products, find themselves unconsciously influenced by, nonetheless (Dichter Citation1985). The goal was to have synergy between the brand identity and brand image (Nandan Citation2005). All elements of the Furscience platform (e.g., website, social media, data collection materials) were developed to proactively deliver consistent messaging in service of the IARP, build trust and recognition within the furry community, enhance anti-stigma efforts via public dissemination of research findings, and change public perceptions of the furry fandom through exposure and education.

Beyond the ivory tower: furscience.com

Developing a strategy for those outside of academia to easily locate and understand the research associated with marginalized communities or anti-stigma efforts is essential. Our priority was to reduce barriers for furries, the media, and the public who wished to access IARP research findings. Paywalls and academic jargon often create obstacles to information, so there was a sense of urgency to create an accessible place where simplified data and findings (e.g., Furscience Citationn.d.-f) could be located and shared through social and other traditional forms of media. As such, Furscience.com was designed to be the hub for information gathered by the research team and to facilitate brand recognition across platforms.

The website houses general information about what furries are, the research team, media coverage, participant recruitment, resources, publications, research findings, and media inquiries. In fact, much of the website content is a response to furries’ requests for aggregate information about their own community. These are not necessarily the kinds of data, nor format, that would interest academic journals (e.g., most common type of fursona species, political affiliation), but they are of significant interest to the furry community, the public, and the media. The website also facilitates participant recruitment into studies (e.g., autism, therianthropy), and it allowed a few thousand furries who trust Furscience researchers to sign up for the Furscience Universal Recruitment Project (Fur-P)—a database of furries who responded to 85+ demographic questions and are willing to be contacted for targeted studies (e.g., high self-esteem, PTSD, disability).Footnote18

The Furscience website and social media platforms also tend to strengthen Furscience’s relationship with the furry community. Making education tools that are both accessible and deemed legitimate available to furries supports the community’s own efforts to counter stigma. Furries disseminate IARP research findings via their own social media posts and articles—often as a mechanism for educating the public with more than conjecture or anecdote. These social media posts then direct people to the website and participants to new studies.

Clearly, furries play a critical role in the success of Furscience’s research methodology and dissemination. As the fandom assists Furscience in raising its public profile, more media sources—such as journalists and documentarians—are increasingly finding and citing the research or contacting the Furscience academicsFootnote19 for perspective. These factors work in tandem to support new research endeavors, disseminate findings of both traditional and non-traditional scholarship, educate the public, and—in partnerships with the community—help destigmatize the furry fandom.Footnote20

Expanding the reach at conventions: the furscience booth

An integral part of working successfully with stigmatized groups is obtaining buy-in from the community. For us, increasing the community’s familiarity with the research team at furry conventions was important. Being able to show members of the community exactly what we do with the data via face-to-face interactions has gone a long way to building trust.

Furscience’s visibility in these spaces is now amplified by an enormous agency-designed and lighted tradeshow booth with pedestals that serve as the research home at conventions (see ).Footnote21 Consistent with concepts of exhibition marketing and successful “boothmanship” (e.g., Søilen Citation2013), the team uses convention spaces to appeal to multiple senses: bright, complementary colors (Furscience orange and blue), branded tablecloths, two large iPads on mic stands-one playing Furscience videos on loop and the other demonstrating the website functionality so that participants can see exactly how the data are used. Peer-reviewed publications are often displayed and made available at the booth for furries to take with them. A gumball machine and a loud, clacking spin-to-win wheel for small prizes (Furscience branded orange pencils that change color, buttons, lanyards, silicon bracelets, stickers, etc.) facilitate the growth of social media supporters and draw attention to the booth.Footnote22 The research team also wears highly visible Furscience-branded lab coats,Footnote23 which are an inside joke with the fandom—lab scientists studying animals—and Furscience T-shirts that incorporate branding elements.

The Furscience booth helps to recruit participants into studies.Footnote24 High visibility with the booth also means that the Furscience research panels are well advertised and attended events. In some cases, the convention organizers show their support for Furscience by introducing the team to the convention at opening ceremonies or making team members guests of honor, which helps build credibility. To support programming, the team often holds special events in partnership with the convention organizers or hosts events important to the community—like the parents’ panels for first-time “con-goers” (furry convention attendees).Footnote25 These events are often livestreamed and/or posted to YouTube.Footnote26 Team members also donate items to support the convention’s fundraising goals for their selected charities.Footnote27

Convention attendance also allows for furries to influence the evolving vision of Furscience. This supports the “de-professionalization” that comes with a participatory planning model of community development and creates a sense of “collective power” (Nasca, Changfoot, and Hill Citation2018: 638), where furries feel empowered to become collaborators, part of Furscience’s dissemination efforts, or appear in Furscience media promotions. Furscience’s CCD attends conventions to film promotion pieces in partnership with the furry community, which are then displayed at subsequent convention research talks and looped on the iPad at the booth. In these short videos, Furscience shines a spotlight on the talents of the fandom, whether that be highlighting amazing dance moves in a parody of Footloose called Furloose (see ) or the talents of fursuit makers in The Furry Bunch parody (see ). These kinds of partnership activities reside outside of traditional forms of research dissemination, but they are crucial for building rapport between Furscience and the furry community, and they create the foundation for educational promotions, such as the Just Like You* campaign.

Partnerships with the furry community

Building trust and working in partnership with stigmatized communities is essential for success. Furscience works collaboratively with various furries on their own fandom initiatives (supporting the fandom’s own capacity building), such as appearing as guests on Culturally F’d (furry YouTubers who contribute furry-oriented social commentary in Toronto) or being regular contributors to furry-produced podcasts (e.g., Fur What It’s Worth in Utah, FurCast in New York). These are examples of furries who use their own platforms to create educational and destigmatizing content. By working together, both platforms benefit. In the next sections, we offer three examples of collaborations with the furry community.

Just like you* *but with fur—a tongue-in-cheek, PSA-style Video Series

The Just Like You* campaign was an anti-stigma, public service announcement (PSA) project designed to interest the public in exploring the research findings on Furscience.com (see ). The target audience (Grier and Bryant Citation2005) was an ignorant, but curious, public. It was a multifaceted project where Furscience (with the CCD) partnered with furries to write, storyboard, cast, film, and produce five short videos, which is consistent with the type of co-created change advocated by Collins (Citation2014). The campaign was framed around furries doing banal, everyday things in fursuits: parking a car, doing yoga, wine tasting, going to the bathroom, and going on a date. The set up was to portray situations that the public expected to see—teasing the stereotype—with the punchline being that, of course, furries do not do these things in fursuits, but the public could learn more about furries by going to Furscience.com. The videos were relatively successful from a “views” perspective, but more importantly, they helped us kickstart the conversation such that the mainstream media started asking us questions. The campaign was first picked up locally and then nationally, which included radio spots and articles via CBC, an article in VICE, and a video on VICE. Within a month, Facebook metrics showed that the campaign had reached over 150,000 people. The media coverage of the campaign also drove traffic to the website, which furthered the IARP’s dissemination mission.

The furry bunch—resources for parents

The information for parents panels co-hosted by Furscience at a convention revealed a need to add a parents’ section on Furscience.com. The team worked collaboratively with Tempe O’Kun, a writer and furry from Culturally F’d, and Moms of Furries in Nevada—a pair of supportive moms who have children who are furries—to develop a list of frequently asked questions for parents of young furries. Furscience then peppered the document with evidence-based research. To celebrate the new parental resources (Furscience Citationn.d.-g), we filmed a shot-for-shot parody of The Brady Bunch TV intro called The Furry Bunch ().

Autism in the Fandom

Working with convention organizers, Furscience developed resources related to autism in the fandom. People on the autism spectrum often struggle with loneliness and social isolation, so finding a supportive community can make a crucial contribution to social development and overall quality of life (Fein Citation2015a, Citation2015b, Citation2018, Citation2020; Müller, Schuler, and Yates Citation2008; Sosnowy, Silverman, and Shattuck Citation2018). Following the observation that people on the autism spectrum participate in the furry fandom at unusually high rates, the IARP conducted a series of research projects. The research produced a report (Furscience Citationn.d.-d, under construction) with a series of suggestions for conventions and other furry events to support participants on the autism spectrum. The resources for parents of furries and conventions to create safer and more accessible spaces for autistic participants is an example of how research and data can be combined with lived experience and expertise to benefit the greater community, as well as reducing stigma via accessible education.

Partnerships with media: changing the narrative based on data

Furscience learned early on that public education efforts yielded greater impact if the team nurtures relationships with media. Stepping beyond traditional dissemination methods means that Furscience accepts most opportunities to engage with media (video, television, radio, newspapers, magazines) who are interested in the research. As academics—some of whom are furries—Furscience offers a combination of expertise, credibility, and lived experience that is often sought in various media reports.Footnote28,Footnote29 Additionally, Furscience is occasionally asked to be technical consultants on projects (e.g., CNN’s This is Life with Lisa Ling, PBS’s Subcultured, Dr. Phil). However, when Furscience began, getting the research covered in the media necessitated we pursue contacts with local reporters to suggest story ideas and offer interviews. For example, Just Like You* coverage happened because we initially reached out to a friendly local reporter who covered the story and that story led to local radio interviews and subsequent national coverage on CBC. By creating a public-friendly, PSA campaign, we created a current event that the media was interested in covering, and that generated opportunities to discuss and disseminate our peer-reviewed scholarship.

Notably, diverse audiences (e.g., the public, major news outlets like PBS and NBC, the furry community, other academics) require tailored engagement strategies. As such, Furscience’s CCD developed a multi-pronged approach to engaging in media appearances that selects for the audience (e.g., Grier and Bryant Citation2005). When the efforts are directed at the fandom, they usually include humor and references recognizable to those within the community. However, with major media partners, the IARP takes a serious tone. In these circumstances, Furscience’s professional branding and science communication strategies help facilitate message reception—that leisure activities, even fantasy-themed ones, can and should be taken seriously by people, rather than be trivialized or ridiculed.Footnote30 By forging these media partnerships, Furscience has not only been able to communicate its research findings to audiences all over the world, but the voices of furries are also amplified (i.e., partnering with furries at conventions to manage media requests).Footnote31

Analysis and results: is it working?

The IARP’s public dissemination strategies represented a shift toward social marketing—the idea that marketing strategies can be implemented to challenge undesirable social attitudes (e.g., Collins Citation2014) and stigma (e.g., Corrigan Citation2011). Furscience’s brand identity was critical to the IARP’s mission of growing public awareness—partly for a more palatable name recognitionFootnote32 but also because quality branding makes consumers of information more open to receiving messages (e.g., Aaker Citation2012). It was a professional look, taking a serious approach, but also captured the fun of furries, and thus serving a key role in reframing the research team’s conversations with media away from deviance to the facts. The question remains, though, is Furscience reaching more people?

Google analytics and search engine optimization (SEO)

Measuring the success of the Furscience approach to knowledge dissemination is difficult. However, there are tools that can help us gain some insight into the effectiveness of Furscience’s innovative strategies. The next section offers an analysis of data from Google AnalyticsFootnote33 for Furscience’s website traffic,Footnote34 followed by a summary of SEO metrics.

Results from google analytics: evidence suggesting the growth of furscience.com

During the first 12 months of Furscience.com “going live” (2016–2017), the website had 43,843 (3,658 average monthly) visitors and 149,991 (12,499 monthly) pageviews, which were driven by the release of the (free) Furscience book and national coverage of the Just Like You* campaign—all of which were supported with social media. In the most recent 12 months of data (2022), the Furscience website had 225,223 (18,768 monthly) visitors and 409,068 (34,089 monthly) pageviews (without the benefit of a strong campaign during the pandemic), which represents a 413% increase in visitor growth and 173% more pageviews within five and a half years. These data are reported in .

Table 1. Website metrics for furscience.com, IARP original (pre-furscience) website, and IAmRP (anime) website at various 12-month intervals.

However, would that growth have occurred without the Furscience rebranding? What would the traffic metrics have shown if Furscience remained the International Anthropomorphic Research Project (IARP) and continued with its original (pre-Furscience) Google site? While it is impossible to answer that question with certainty, it occurred to the authors that, unintentionally, a comparison group was available that could offer perspective.

The international anime research project

Furscience engages in studies of other fandoms to use as comparison groups. As such, in 2013, the team developed a parallel research initiative called the International Anime Research Project—even using the same initialism the IARP, but for clarity, is referred to here as the IAmRP. Using identical methodology—often identical studies—the Furscience team, under the IAmRP name, conducted online and in-person studies with anime fans with annual participation rates that were similar for furry (approx. 3,500) and anime studies (approx. 3,000).Footnote35

As the IAmRP, our team has also published about two dozen papers on anime fans. To facilitate research dissemination, a Google site that paralleled the original IARP furry research website was developed in 2013 (International Anime Research Project Citationn.d.). Overall, the academic content is similar for both websites—biographies of the team, results from research, current and upcoming studies, a schedule of events the team will attend, etc. Like Furscience’s research summary book (Plante et al. Citation2016, forthcoming 2023 release), the team’s anime research book (Reysen et al. Citation2021) was made available for free download on the website. Importantly, Furscience rebranding techniques were not replicated with the IAmRP. There is no IAmRP social media on Instagram, Twitter, or Facebook, no video campaigns of any kind, no seeking media coverage—nothing but the dissemination of findings that are more consistent with traditional scholarship. As such, the three websites, the IARP original (launched in April 2011), IAmRP (launched August 2013), and Furscience.com (launched April 2016) can offer points of comparison to gain some insight into the effectiveness of Furscience.

IARP (pre-furscience), furscience.com, and IAmRP (anime): website traffic comparisons

The earliest Google Analytics data for the IARP and IAmRP were limited to new users data and pageviews.Footnote36 The IARP (first 12 months, 2011) and IAmRP (first 12 months, 2013) user data comparisons are reported in : The IARP website had 6,109 (509 monthly) new users and 14,304 (1,192 monthly) pageviews, and the IAmRP website had 4,561 (380 monthly) new users and 8,562 (714 monthly) total pageviews. Despite more global interest in anime,Footnote37 the traffic was similar for the two websites in the first 12 months after launching: the IARP (furry) had 33.9% more new users and 67.1% more pageviews than the IAmRP (anime) at baseline.Footnote38 Contrasting the first 12 months (2013) of the IAmRP data with the most recent 12 months (2022) of IAmRP data () shows that the traffic on the IAmRP website remained stable, but, overall, the trend is flat—pageviews (9,278; 773 monthly) were slightly up in the most recent data (8.4%), but new user numbers (3,485; 290 monthly) were down by 23.6%.

In summary, the IARP (furry original) and IAmRP (anime) websites had similar traffic when they began, and the IAmRP maintained consistent traffic over the next nine years. As such, a reasonable hypothesis would be that the IARP (pre-Furscience furry research) website would have had a similar, slightly higher traffic trajectory than the IAmRP if it had not been replaced by Furscience. However, when the first 12 months of the IARP (old website, 2011) traffic was compared to the most recent 12 months of Furscience.com traffic (2022), it shows new users (204,892; 17074 monthly) and pageviews (409,068; 34098 monthly) increased (3,254% and 2,761% growth respectively; see ).

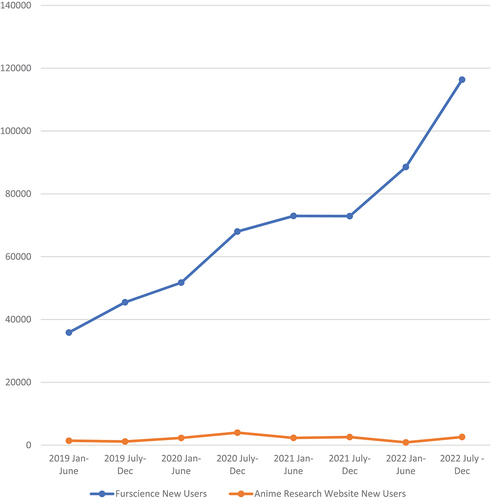

Moreover, when Furscience’s and the IAmRP’s web traffic are contrasted for the most recent 48 months (2019–2022) of data, significant differences are found. reports the Google Analytics data for Furscience and the IAmRP in more detail (6-month intervals for January 1, 2019, to December 31, 2022). Users, new users, sessions, pageviews, and unique pageviews indicate, on average over the 48 months, Furscience.com outperformed the IAmRP website by 3,198% to 3,478% on these measures (all p < .001). There were no significant differences between the two websites in terms of page sessions, the average duration of a visit, or bounce rate (). This indicates that the type of interactions that people have on both websites is similar; there is simply more traffic on the Furscience website. shows the relative growth of new users for the Furscience and IAmRP website between January 2019 and December 2022 in six-month periods. Overall, the data for 2019–2022 show that the anime website had over 15,000 new users while Furscience.com had over half a million.

Figure 2. Graphic representation of the rate growth for Furscience and the IAmRP website: new user data in six-month periods (January 2019 – December 2022).

Table 2. Website metrics for furscience (branding supported) and the international anime research project (branding non-supported).

Furscience: keywords and search engine ranking

Ranking in internet searches is another way of assessing the success of the Furscience approach. Most internet users visit links from the first page of search results, so with billions of websites available, achieving a high ranking is important and exceedingly difficult (Krrabaj, Baxhaku, and Sadrijaj Citation2017). Ubersuggest (Ubersuggest Citationn.d.) and SEMrush (SEMRUSH Citationn.d.) are two popular website SEO analyzers that, among other things, estimate the frequencies of internet keyword search terms (i.e., furries) and the top returns (websites) from those searches. At the time of writing, furscience.com received first-page ranking for many relevant keyword searches (e.g., Google). shows the ranking and traffic from the two SEO analyzing tools. For example, the keyword phrase what is a furry is Google searched 40,500 times in a month, and this keyword returns 1.77 billion results—out of those, Furscience.com is second on the list. Having the media create backlinks to Furscience improves ranking (Krrabaj, Baxhaku, and Sadrijaj Citation2017).Footnote39 The findings indicate that Furscience’s academic information is near the top of relevant keyword searches.

Table 3. Search engine optimization data for furscience.com: Furscience ranking and keyword search traffic from Ubersuggest and SEMrush.

offers details on the websites that rank above Furscience.com in keyword searches. According to Ubersuggest, Furscience.com ranks fourth on searches for furries. However, the websites that rank higher than Furscience.com include a Vox article that cites the old IARP website (Matthews Citation2014), a CNN article that links to Furscience.com (Patterson Citation2018), and Wikipedia (Fandom Citationn.d.), which references Furscience publications and posts a direct link to the free book as recommended further reading. Similar findings were reported for keyword searches from SEMrush. The results indicate that when the public explores important keywords to find out information about furries via internet search engines, the information from Furscience is returned at or near the top of the results, both directly and indirectly. Most importantly, it stresses the importance of working with media and creating backlinks to research.

Table 4. Furscience ranking from keyword search traffic analysis from ubersuggest and SEMrush.

Is the tide changing?

While there is preliminary evidence that Furscience is receiving more public attention than it would have if it continued as the IARP, whether that translates to changed public sentiment is challenging to quantify. However, Furscience ascertained some evaluation of whether the tide of public sentiment is changing according to furries—the stigmatized group. As such, in 2018, a few years after Furscience was established, data were gathered at a convention (n = 1039) and online (overflow, n = 95), where furries were asked (Likert-type scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 4 = neutral, 7 = strongly agree) two questions: “In your opinion, the fandom’s reputation (in the public) is more favorable now (seen more positively) than it was five years ago” and “In your opinion, the media coverage of furries (news) is less favorable now (seen more negatively) than it was five years ago.” The online sample reported that the fandom’s reputation was improving and that incendiary reporting in media was declining (mid-point was 4), M = 5.88, SD = 1.21 and M = 2.85, SD = 1.54. Findings were similar in the convention sample: M = 5.76, SD = 1.15 and M = 2.94, SD = 1.45, respectively (Furscience Citationn.d.-b).Footnote40 This provides preliminary evidence that at least some members of the furry community see an improvement in the way that the public views the fandom and how it is represented in the media. This is positive, as research indicates that felt stigma is correlated with lower psychological wellbeing (Quinn and Chaudoir Citation2009).

A myriad of reasons that do not include Furscience could explain this change. For instance, the furry community is filled with talent (e.g., musicians, artists, designers, gamers) that garners attention through social media. Large furry conventions help to sustain local economies (e.g., Anthrocon in Pittsburgh) and facilitate interactions between the public and the furry community.Footnote41 Moreover, many charities benefit from the immense generosity of the fandom. All these factors, and more, could be contributing to these furries’ perception of improvement.

However, there is evidence suggesting that the efforts of Furscience might also be playing a small role. The ability to reach a broader public is slowly increasing with easier-to-find destigmatizing information and Furscience’s increasing penetration of media. In this way, Furscience has, perhaps, scratched the destigmatizing surface on correcting the public record, which was not possible when CSI broadcasted a sensationalistic portrayal of furries to more than 27 million viewers in a single week. Nevertheless, perspective is warranted. Compared to marketing giants, “news” outlets spreading misinformation, or influencers who reach millions of people each day, Furscience’s reach feels inconsequential. Furthermore, our user data that suggest increased reach do not permit an assessment of whether the anti-stigmatizing message was absorbed (Rik, Roosjen, and Poelman Citation2013)—particularly in the face of readily available misinformation.

Despite Furscience’s efforts to educate the public and more media reporting the facts, the battle is very much uphill. There are emerging obstacles to destigmatizing the community, such as furries becoming a political pawn in—what has been suggested to be—a thinly veiled attack on transgender rights (e.g., Weill Citation2022). In the past year, many schoolboards and some government officials are charging that furries are asking for litterboxes in bathrooms (e.g., reviewed in Paz Citation2022) or asking for cafeteria tables to be lowered so furries can eat without utensils (reviewed in Solomon Citation2022). In fact, some of the alleged behaviors (i.e., how furries use bathrooms or drink wine in their fursuits) were the very misconceptions used in the Just Like You* campaign. Other erroneous narratives declare that kids in schools are “becoming furries” and “identifying as cats,” but furries do not identify as animals (Gerbasi et al. Citation2017).Footnote42 Luckily, some reporters now contact Furscience for fact-checking purposes—such as Reuters Fact Check (Citation2022), NBC (Kingkade et al. Citation2022), Politifact (Czopek Citation2022), and Snopes (Palma Citation2023)—which are subsequently signal boosted by other media.Footnote43 Whether the public ever fully embraces the furry fandom for what it is—a haven for connection, creativity, and community—remains to be seen. Reputable media recognizing the “litter boxes in school bathrooms” is a “furry hoax” is encouraging. There are even cases of public retractions, such as Joe Rogan on The Joe Rogan Experience podcast walking back his comments on the litter box situation (see Demopoulos Citation2022). However, misinformation about furries remains pervasive and widespread as it shifts from being mainstream to political (Roberts Citation2022). As such, Furscience will strive to educate the public via effective science communication and partnerships with the furry community—the seeding of a grassroots movement to take the evidence-based, peer-reviewed scholarship of academics studying a stigmatized group of people and expand it beyond the limitations of traditional academic dissemination.

Discussion: our lessons learned

We recognize that studying furries is a niche area of scholarship. What could, say, a mental health researcher or someone who engages in translational criminology glean from this report documenting the experiences of furry researchers? While there are elements of Furscience’s strategies that are unique to the community, such as being able to tap into furry conventions as a resource, there are lessons we have learned that may be generalizable to other researchers. We close our article by extracting general conclusions from our experiences that could possibly be applied to studying stigmatized groups or unusual research topics and research dissemination that is both traditional and non-traditional.

Relationships with participants

Good research relies on meticulous ethics, good methods, and data, and good data are, in large part, predicated on fostering trust with participants. The IARP would have failed in its foundational research mission without the trust of the furry community. Researchers must build a solid and earned reputation with the community being studied—not just the gatekeepers—and part of that is understanding the culture of the community or target audience and demonstrating that understanding through actions.Footnote44 Being visible and accessible as researchers, having face-to-face interactions where possible and appropriate, engaging with communities through social media, giving public research talks, etc., all help researchers to build trust with participant communities. Researchers should demonstrate transparency with their participants regarding how their data are used and involve the community in all stages of the research (e.g., planning, asking for community members to plan or test-drive surveys, sharing authorship, or reviewing papers before publishing). As the trust between the researchers and community grows, researchers might weigh the value and risks associated with building a database of participants who are willing to be contacted for future studies (and house it securely and according to ethics), especially if participants are difficult to find or they occupy a rare or niche identity/role. Finally, have a dedicated place where participants can easily find research results.

Researchers might also consider applying a participatory planning model to their research, as there can be great value in insisting the core research team be informed—at least in part—by lived experience and engaging participants in advisory boards. Researchers can also take advantage of funding opportunities that train non-academic participants in research methods so that they can become active collaborators on grant applications and projects (i.e., patient-oriented research). Moreover, when permitted or espoused by ethics, researchers should share ownership of data (i.e., Indigenous communities) and/or consider making it available more broadly.Footnote45 Collaborating with communities also means that researchers offer support for the community’s own initiatives (i.e., support capacity building) and projects. This might include offering support via in-depth planning of projects, giving interviews, or signal boosting the community’s activities through social media.

Peer-review publishing and research funding

When trailblazing a new area of research—particularly if it is misunderstood by the public—getting those first publications can be difficult. Be tenacious. Academics who receive dismissive or nasty rejection letters from journals can assess the potential value (or harm) in using them (de-identified) to make a more compelling case in subsequent submissions. Researchers should also apply for grants methodically; funded research helps to build team credibility, research project completion, and dissemination—all of which strengthen subsequent grants and publications. Small, internal grants can demonstrate success and build momentum for larger applications. Obtaining ethics approval prior to grant applications might help with feasibility scores, as can anchoring an element of a brand-new topic to something that is well established (e.g., studying the identity formation of furries’ fursonas). Based on our experiences, we remain hopeful that excellent quality research will eventually resonate with decisionmakers—even when the research topic falls outside of the scope of traditional academia.

Brand identity

Developing a strong brand identity is possibly the most important lesson that Furscience can offer other academics who wish to disseminate evidence-based research to non-academic audiences, and the strategy applies broadly to researchers who study stigmatized communities, mental health, or, really, any topic where the dissemination of information matters. Brand recognition and popularity may also help improve Google rankings, which is crucial for getting accurate information to a curious public.Footnote46

Brand appropriateness and uniqueness—avoiding clichés—are key. A solid brand should simultaneously speak to the caliber of the scholarship and demonstrate researchers’ understanding of—or compassion for—the topic, target audience (e.g., other academics, the public, media, policy implementation end-users), or people studied.Footnote47 Budgeting for professional marketing or adding a Communications and Creative Director to the team who takes the time to understand the academic vision, community, and target audience may make a huge difference in the success of knowledge mobilization. If there are no funds available, then there may be more economical opportunities to access resources via the home institution’s marketing office.Footnote48

Once a brand is developed, use it fervently and ensure compliance in brand consistency across every public communication (i.e., no stretched or old logos, mixing of fonts) from all team members working on the project. Although it is a time-intensive endeavor that is often not formally recognized in academic job performance metrics, engaging in activities (e.g., social media) that will increase brand recognition is important. There are also many low-cost—but professional-looking—branded items that can foster brand awareness or direct people to engage with the research team’s social media or website (e.g., lip balms, mini hand sanitizers, or other small, but useful, items). If face-to-face interactions or piquing the curiosity of people passing by are desired, then a branded tablecloth, custom floor stand, or a trade-show booth (that fits into a suitcase with wheels) can facilitate opening conversations. Purchasing custom T-shirts for team members can also increase brand visibility at public events.Footnote49

Traditional forms of academic messaging compete with social media influences that often have a larger reach than legacy media networks and are algorithmically ranked by user preference and popularity. These platforms may have unchecked quality control, yet they are deemed as credible by many information consumers. As such, getting academic messaging noticed may be difficult. However, good marketing does more than just sell hamburgers and soap: it elicits confidence and fosters credibility, which, in turn, facilitates message reception for the end user. Relying solely on the merits of the work for dissemination (i.e., “the work stands for itself and doesn’t need branding”) can be a missed opportunity, especially if the researchers desire to have their scholarship become part of the public narrative but are competing with savvy misinformation campaigns. And, for those academics who become interested in developing non-traditional dissemination strategies, they must avoid the pitfall of believing that good marketing is easy. Good marketing looks easy when it is encountered because it was designed that way.

Peer-reviewed scholarship is the backbone of academic work, but it is only the first step to getting quality information to the public. If our goal—as academics—is to have the public benefit from the research they fund, then the paradigm needs to shift from academics stigmatizing or dismissing other academics who disseminate to the public with “crossover” scholarship to one that embraces the inclusion of media tactics that are better suited to compete in the attention economy. Applying branding and marketing principles to academic findings does not sacrifice the quality of work. However, simplifying scientific facts and nuanced research into digestible packages of information can improve research dissemination to non-academic audiences. If the approach is ethically sound and evidence-based information is at the core, then our experience suggests that marketing strategies can be adopted by academics to help educate the public and undo the stigma that comes from pervasive misinformation.

Website

Building a dedicated website with a unique URL that is easy to recall can facilitate information dissemination. When buying the domain name, we suggest purchasing the other variations (i.e., .com, .org, .ca, .net) and have those domains redirect to the main URL.Footnote50 This can help prevent bad actors from damaging the brand or message, especially when dealing with stigmatized communities. We advise researchers to set up an alertFootnote51 to warn them when the domain license expires and renew before that date.

Having a presence on the Internet because you are advocating for—or even just a disinterested party who is dispassionately describing evidence-based findings that refute common misconceptions—means that you could garner a lot of attention, both positive and negative. Particularly in cases where the topic may be deemed controversial and result in extraordinary numbers of hacking attempts, in addition to complex passwords, password managers, and two-factor authentication, researchers might wish to use a hosting service that offers time-machine or cloud backup to reset services for compromised websites. That way, if the website is hacked, the system can be shut down and reset with limited loss and downtime, which is theoretically easier than having to rebuild the website from scratch. As such, researchers must pay careful attention to software security updates for all associated systems.Footnote52 Remember, some of the biggest companies in the world, who presumably have the best cyber security money can offer, have had their systems compromised and information stolen. If it can happen to them, then it can happen to anyone.

Make sure that more than one person can attend to the needs of the website—with at least two people maintaining full administrative access. If you allow for comments, have a moderator approve them before posting and remove identifying information. In our experience, people leave sensitive information in their public comments, such as full names and e-mail addresses. Researchers may wish to avoid collecting non-essential, personal information via the website, even though this is an easy option to set up. If a researcher must capture data on vulnerable people, then consult security experts and use a secure and encrypted database so that if it were compromised or captured, it would be scrambled data without the encryption key. Data security is an ever-evolving concern, so be familiar with university policies and best practices.Footnote53

Branded social media

We suggest that researchers reserve social media accounts (YouTube, Twitter, Instagram, Threads, etc.) using the branded name before launching the website; this will also help to identify possible sources of brand confusion. Have the marketing team develop brand-consistent logos for use in social media in addition to black and reverse versions. Researchers may opt to enlist the help of a few dedicated and highly responsible people who thoroughly understand the mission of the project; will post information related to the project appropriately and regularly; create links across various social media platforms; work with others to develop materials that are made exclusively for social media releases; and, crucially, demonstrate that they are aware of the political nuances needed to engage online and that a poorly-conceived 140 character post can destroy the brand and years of work. Similarly, a brand’s “follows” are sometimes interpreted to be endorsements and can unwittingly introduce political controversy.

We suggest taking steps to protect the privacy and safety of team members, such as not linking personal social media to branded social media or revealing that information via likes or tags. Where permissible, consider using pseudonyms with e-mails that are exclusively reserved for personal social media (i.e., not a work e-mail). There may be value in limiting the amount of personal information posted on the Internet, signing up for dark web monitoring, identity theft insurance, and a password manager, and monitoring evolving Internet safety tools.

Media connections

Developing connections with reporters, local media, universities’ communications departments, and community partners can all help researchers to elevate the coverage of peer-reviewed research and unique dissemination projects. All these relationships should be carefully nurtured. Researchers may have the opportunity to leverage their institution’s social media to garner attention for new projects and dissemination events. Furthermore, by signing up for an institution’s “expert” list, researchers may get a foot in the media door with a local story. In our experience, reporters often identify the “experts” in an area via other reporters’ articles, and a local story can quickly lead to national coverage.

We have observed that the media will often tell a more accurate or complete story when we provide them with additional background and relevant materials. As such, we strongly suggest that researchers follow up with a journalist post interview and offer links to their relevant articles and website. When appropriate, they can offer access to a drop box with selected rights-owned B-roll footage and/or stock photography (i.e., we provide news stations with generic footage of public parades so that they have something to play while they are making their report) or photos with the provision they credit the brand or, preferably, link to the website.

Building a reputation as “helpful” with reporters, documentarians, and journalists, for us, anyway, has led to additional opportunities.Footnote54 It is also worth noting that while scholars may work directly with reporters or journalists to convey the facts of their research, unless that message is conveyed to the supporting production team, too, then some important—often visual—details can be missed (e.g., such as the media outlet licensing images that represent misconception more than fact). Finally, when an article or feature is published by the media that does a good job representing the subject, researchers may choose to share the link on their social media, even if the report is not based on their research.

Controversies and media

Not all media requests for interviews or appearances are made in “good faith,” especially if coverage of the topic is rife with misinformation and/or disinformation. A scan of previous stories written by a reporter may yield some insights into their intentions. Researchers may benefit from consulting their institution’s ethics and communications experts to handle tricky situations. Responses could include not participating in the media request, limiting interactions to written communications, or, with permission, recording the interviews so they can be released in their entirety, if necessary. It is wise to assume that any written communications may be published without permission (i.e., in an article or in a dissertation). Researchers must remain aware of hot mics and assume everything said in an interview—before, during, and after—is being recorded and could be used. When the stakes are high, ask for the questions ahead of the interview and practice video-recording your answers and review them.

For professors who teach classes, addressing new content each week is expected. However, media interviews are different than classes—do not assume there is crossover in the interviewers’ audiences. Carefully develop a list of talking points and stick to them. The repetition may also help develop a smoother delivery for this kind of dissemination. Researchers should always exercise caution when asked to weigh in on topics that are outside of their expertise. When this happens, acknowledge the question (that’s a great question), explain that the answer would be outside of the scope of the research expertise (I don’t want to speculate on matters outside of my expertise or you’ll have to ask a specialist in X for a satisfactory answer to that question or that’s a great idea for a future investigation), and then bridge (however, what I can tell you is) to one of the talking points.

Overall

These are some of the lessons we learned from more than 15 years of conducting (sometimes stigmatized) research on a highly stigmatized community (perceived as deviant by the public) and disseminating that information in (sometimes) non-traditional and stigmatized ways. Some of our lessons are a consequence of our own epic failures and the mistakes we made along the way, while others came from being the targets of both positive and negative attention. Some came from having experts in our corner who guided us well—like our CCD and exceptional grant writing expert. Some lessons came from being lucky. All of them were the product of a genuine desire to understand a maligned, stigmatized community who deserved to have science help to set the record straight.

Peer-reviewed scholarship is considered a necessary condition of academia, but it is often insufficient to move the needle on public perception (Nichols et al. Citation2019). While open access journal articles may satisfy funders’ requirements for knowledge dissemination and make scholarship more available, they will often fail to make the information more accessible to the public in terms of how it is presented. In the same way academics gain rich expertise by partnering with interdisciplinary investigators, researchers who include communications specialists may benefit from their unique skills. In this article, we have offered academics a rudimentary introduction to some of the design and marketing tactics, strategies, and skills that facilitated Furscience’s public message penetration.

Limitations

It is impossible to know which part of our Furscience strategy was most effective, but we believe all elements have reinforced each other: branding, accessibility, building trust with participants, community partnerships, engagements with media, social media use, and the credibility that comes with peer-reviewed scholarship/grants have all worked in tandem to engage in sound research, publish the findings in peer-review, and communicate the results more broadly. Overall, the Furscience website traffic (>3000% more traffic than the IAmRP), first page Google rankings, and penetration of mainstream media suggest (1) that the IARP’s research is becoming a known resource within target audiences and (2) that the Furscience branding played a role in this success.

Ultimately, researchers and community advocates must remain vigilant regarding their legal/professional, social, and ethical/moral responsibilities related to research and dissemination and stay informed of requirements, limitations, or cautions based on emerging political, legal, national, and cultural or religious contexts. What might have worked in one environment or timeframe or even as a topic for mainstream discussion may not be feasible or advisable to replicate. As the world changes at a rapid pace, tread carefully, bravely, and ethically.

Final words

Furscience is an example of an academically-based dissemination tool seeking to bridge the gaps among highly marginalized creative communities, the scientific community, and the public. Positioned adjacent to the furry fandom, Furscience aids in amplifying the voices of community members in destigmatizing endeavors. However, the furry community also aids Furscience—the IARP’s goals were advanced only by forming partnerships with the furry community. Other marginalized creative communities, mental health researchers, or academics who study any group of people could mutually benefit from recognizing communities as partners in science. There is much to learn from creative, resilient communities and what they offer in terms of unique insights on social support, anti-stigma visions, and finding belonging. Though the furry fandom might seem to be an obscure example of a marginalized subculture, the IARP-Furscience research methodology and fandom-immersed approach can provide a template for the study of other communities and topics where there is deep distrust of outsiders that is fueled by misinformation popularized by the media.

Acknowledgements

Achieving research and dissemination goals—especially in the early years—came with significant challenges. We are grateful to the institutions, journals, and funding agencies who saw the potential in our early anthropomorphic work, without whom the research would not have been possible. We wish to express our sincere gratitude to the many furry conventions (CEOs, organizers, and amazing staff) who have supported Furscience by allowing our team to meet face-to-face with participants over the past 16 years. Thank you to the reporters, journalists, documentarians, and producers who were willing to approach the topic of furries with an open mind. We are thankful for the dozens of students, research assistants, and volunteers who have helped us conduct and disseminate research, and for the furries who reviewed this manuscript. A heartfelt thank you to our CCD, Malicious Beaver, for his endless dedication to Furscience. Most importantly, we are indebted to a media bruised community—the furry fandom—who placed their trust in academics. We hope that Furscience will continue its mission with the next generation of researchers who will persist in collaborating with the furry community via scientific investigation, information dissemination, and anti-stigma education rooted in evidence.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sharon E. Roberts

Sharon E. Roberts is an Associate Professor at Renison University College at the University of Waterloo in Canada. Her educational background is interdisciplinary: Sociology (PhD, MA), Psychology (BA Hns), and Social Work (MSW). She is one of the co-founders of the IARP/Furscience.

Chelsea Davies-Kneis

Chelsea Davies-Kneis is a registered social worker in Ontario, Canada. Chelsea holds a BA in Social Development Studies and BSW from Renison University College, University of Waterloo, and recently completed an MSW at the University of Windsor. Chelsea has been working with Furscience as a research assistant since 2018.

Kathleen Gerbasi

Kathleen Gerbasi is Professor Emerita at Niagara County Community College, where she has received the SUNY Chancellor’s Awards for both teaching and research. She is a social psychologist and anthrozoologist. Her BA and PhD are both from the University of Rochester. She was the lead author of the first peer reviewed psychological publication about furries.

Elizabeth Fein

Elizabeth Fein is Associate Professor and Chair of Psychology at Duquesne University. She received her Ph.D. from the Department of Comparative Human Development at the University of Chicago. A licensed clinical psychologist and psychological anthropologist, she locates her work at the intersection of culture and neurodiversity. Her recent scholarship has investigated autism in the furry fandom, the experiences of therians and otherkin, and the utility of ethnography for psychologists. She is the author of Living on the Spectrum: Autism and Youth in Community (Fein, 2020) and co-editor of Autism in Translation: An Intercultural Conversation on Autism Spectrum Conditions (Fein and Rios, 2018).

Courtney Plante

Courtney N. Plante is an Associate Professor of Social Psychology at Bishop’s University in Quebec, Canada. He is a co-founder of the IARP/Furscience and specializes in research on fan culture, fantasy, and the effects of screen media.

Stephen Reysen

Stephen Reysen is a Full Professor in the Department of Psychology and Special Education at Texas A&M University-Commerce. His research interests include topics related to personal (e.g., fanship) and social identity (e.g., fandom).

James Côté

James Côté is a Full Professor Emeritus of Sociology at the University of Western Ontario, and regularly contributes to three fields of research: sociology of youth, identity formation, and higher education studies. He is also the Associate Editor for the Journal of Adolescence.

Notes

1 Most recently, furries were targeted in false rumors purporting that “kids” are identifying as cats and are asking for litter boxes to be placed in school bathrooms (see Kingkade et al. Citation2022; Roberts Citation2022).