ABSTRACT

Evidence of football fraud and how it can be addressed is fragmented in the literature, lacking a holistic view. This paper provides a holistic understanding of fraud in professional football through a comprehensive framework that encompasses (i) the typologies and methods of perpetrating fraud in football, (ii) the enablers of football fraud, and (iii) how to mitigate fraud risk in professional football. Additionally, it highlights literature gaps and suggests new directions for future research to open up academic debates on this significant topic. The findings show no evidence of external fraud reported in the literature. However, insider fraud, particularly corruption in all its forms, is well documented. There is minimal evidence of other insider fraud types, such as asset misappropriation and financial fraud, and even fewer studies discussing fraud against football players and fans. The analysis highlights various fraud risk factors in football, ranging from financial and sporting performance, competitive balance, and financial regulation issues to the lack of accountability, anti-fraud controls, governance mechanisms, and weak integrity culture in FIFA and football clubs. The paper summarizes various other motives and opportunities enabling football fraud and proposes a holistic framework for mitigating fraud risk in football.

Introduction

Recently, integrity and accountability have become a concern for the sports industry, mainly due to sports fraud incidents (Andon and Free Citation2019). Many fraud scandals, such as FIFA’s corruption case and the Greek and Italian football scandals, have blemished this glamourous industry (Nastos et al. Citation2017). Fighting football fraud is a public interest issue as fraud undermines the integrity of the competitions and damages the social, educational, and cultural values and sports’ economic role (Pouliopoulos and Georgiadis Citation2021).

Academic research can help by providing the knowledge that equips practitioners and policymakers to counter football fraud. Scholars assert that understanding fraud types, methods, and risk factors is essential for countering fraud (Kassem Citation2021; Wells Citation2011). However, evidence of football fraud and how it can be countered is fragmented in the literature, lacking a holistic picture of this crime. The current paper addresses this knowledge gap by providing a holistic understanding of fraud in professional football through a comprehensive framework that encompasses (i) the typologies and methods of perpetrating fraud in football, (ii) the enablers of football fraud, and (iii) how to mitigate fraud risk in professional football. It also highlights literature gaps and suggests new directions for future research to open up academic debates on this significant topic.

The findings are based on a comprehensive interdisciplinary general review of 200 peer-reviewed academic articles from 2000 to 2022 using multiple search engines and databases. The paper drew on multiple disciplines, including sports, accounting, governance, ethics, economics, information technology, sociology, and law.

The paper is motivated by the literature gap in this area and the adverse impact of fraud on the football profession and society. Fraud undermines the credibility and integrity of sports and discredits leagues and national sports (Visschers, Paoli, and Deshpande Citation2020). It can lower attendance at games and thus lower financial returns and the value of shares, making clubs less attractive to external investment and sponsorships (Carmichael, Rossi, and Thomas Citation2017) and resulting in football leagues’ collapse (Hill Citation2010). Athletes in football cited fraud as a contributing factor in their bankruptcies (EY Citation2019). Moreover, tax fraud committed by football clubs, managers, and players has a much broader detrimental effect on society by reducing public funds and the quality of public services (Gee, Brooks, and Button Citation2011).

The results show no evidence of external fraud reported in the literature. However, insider fraud, particularly corruption in all its forms, is well documented. There is minimal evidence of other insider fraud types, such as asset misappropriation and financial fraud, and even fewer studies discussing fraud against football players and fans. The analysis highlights various fraud risk factors in football, ranging from financial and sporting performance, competitive balance, and financial regulation issues to the lack of accountability, anti-fraud controls, governance mechanisms, and weak integrity culture in FIFA and football clubs. The paper summarizes various other motives and opportunities enabling football fraud and proposes a holistic framework for mitigating fraud risk in football. The findings have implications for research, police, and practice, which are later discussed.

The paper makes the following contributions. To the author’s best knowledge, it represents the first comprehensive interdisciplinary general review providing a holistic view of fraud in football. In so doing, it advances the literature on sports integrity and criminology. Additionally, the paper responds to various calls for future research. First, the literature has extensively focused on one fraud type in football, match-fixing, and evidence concerning other fraud types is scattered. The current paper provides a holistic view of the forms and methods of fraud in football. Therefore, it responds to Vanwersch et al. (Citation2021) call for future research highlighting other fraud types in football. Second, it discusses integrity and accountability issues in football and their role in countering fraud. So, it responds to Andon and Free’s (Citation2019) call for future research exploring integrity and accountability concerns in sports and the role of accountability in fighting fraud in sports. However, the paper’s contribution extends beyond identifying integrity and accountability issues as it highlights broader issues enabling fraud. Third, by proposing an interdisciplinary, holistic framework for mitigating fraud risk, the paper responds to Vanwersch et al. (Citation2021) ‘s call for research to develop an interdisciplinary approach to tackle fraud’s complex nature and scope. The proposed holistic framework is an initiative to aid policymakers and leaders in mitigating fraud risk in football, thus enhancing the profession’s integrity. The findings can also be helpful for researchers interested in fraud studies and academics in their teaching of criminology, sports management, governance, ethics, and accountability. Finally, the paper suggests new directions for future research, which could open up academic debates on sports fraud or economic crime, a much broader concept.

Following this introduction, the paper elucidates fraud’s meaning, nature, and typologies. Then, it describes the methodology before discussing the forms and methods of fraud in football. Next, the paper highlights the reasons for committing fraud in football before recommending strategies for mitigating fraud risk. Finally, it discusses the results and their implications and provides new directions for future research.

Unpacking the meaning, nature, and types of fraud

Not all EU Member States have a definition of fraud in criminal law, providing an opportunity for criminals to get away with minimum sentences (Bozkurt Citation2012). FIFA’s Code of EthicsFootnote1 does not refer explicitly to “Fraud” nor define it, but instead, it mentions “the abuse of position, bribery, and corruption, misappropriation, and the misuse of funds. This lack of explicit reference to fraud will not make fraud resonate in the minds of FIFA’s staff, making it challenging to recognize and report fraud. Therefore, it is essential to elucidate the meaning and types of fraud.

The Fraud Act 2006 in England and WalesFootnote2 refers to fraud as any dishonest behavior that intentionally results in a loss to the victim(s), exposes the victim(s) to risk, or provides gain to the perpetrator(s). This can occur through false representation (i.e., falsifying information/facts), the abuse of a position of trust, and failure to disclose information when there is a legal obligation to disclose such information. This broad definition of fraud allows a wide range of crimes to be considered and treated as fraud. This includes theft, offering or accepting bribes, manipulating an organization’s financial records, using an organization’s assets for personal purposes without the organization’s consent and knowledge, or simply lying on a job application or insurance form. Likewise, Wells (Citation2011) defines fraud as an illegal and unethical activity involving intentional deception, cheating, lying, or stealing (Wells Citation2011).

Although fraud can be categorized in countless ways, fundamentally, every type of fraud is either organizational or individual, whether we look at it from the perspective of perpetrators or victims (Association of Certified Fraud Examiners Citation2022). Therefore, this study categorizes fraud types into two categories based on fraud perpetrators and victims: (i) Fraud against individuals and (ii) Fraud against organizations.

Fraud against individuals occurs when a person is targeted by an individual or organization that uses deception, manipulations, theft, cheating or lies to defraud them for personal gain (Association of Certified Fraud Examiners Citation2022; Button, Lewis, and Tapley Citation2009). Examples of fraud against individuals in the football industry include criminals selling fake match tickets to football fans or deceiving football players by persuading them to invest in non-existing business ventures.

Fraud against organizations occurs when a single person, group of individuals, or another organization (e.g. football clubs or organized criminal groups) uses deception, manipulations, theft, cheating, or lies to harm that organization for personal gain (Wells Citation2011). Individuals committing fraud against an organization can be insiders or outsiders to that organization.

Fraud against an organization committed by outsiders (e.g., football fans, suppliers, individual criminals, or organized crime groups) is called external fraud. It includes cyber-enabled fraud to steal the organization’s intellectual property or customer data (Kassem Citation2021).

Fraud against an organization committed by insiders (e.g., football players, referees, managers, or directors) is called insider fraud, occupational fraud, or white-collar crime and includes (i) financial fraud, (ii) asset misappropriation, and (iii) corruption (Association of Certified Fraud Examiners Citation2022; Kassem Citation2021; Wells Citation2011).

Financial fraud is manipulating an organization’s accounting records for personal gain. It can be committed by various means, including overstating, understanding, or creating fictitious revenues, expenses, and liabilities, improperly evaluating assets, understating or overstating assets, and improper disclosures (Kassem Citation2018).

Asset misappropriation is the abuse and theft of an organization’s assets and often involves covering the theft to avoid detection through trickery, manipulation, or lies. It includes a wide range of schemes such as payroll fraud, cheque fraud, stealing an organization’s assets, using an organization’s assets for personal purposes, overbilling, procurement fraud, and expense reimbursement fraud. The abuse of assets comprises using an organization’s assets for personal rather than business purposes and, for example, using the organization’s printers to print personal documents (Wells Citation2011).

Corruption is the abuse of a position of trust for personal gain and includes bribery, illegal gratuities, conflict of interest, extortion, favoritism, nepotism, and neglect of duties (OECD Citation2007; Wells Citation2011). Bribery is the “giving, requesting, receiving, or accepting of an improper advantage related to a position, office, or assignment” (Gottschalk Citation2020: 722). Bribery and illegal gratuity are two closely related offenses comprising giving, offering, or promising to give anything of value to a public official in exchange for or because of an official act. The main difference between bribery and illegal gratuity is the intent involved. The initial intention of gratuities may not be to bribe an official. Still, gratuities may turn into bribery or extortion in the future (i.e., there might be an understanding that future decisions beneficial to that person will also be rewarded). In economic extortion, a person threatens another person or an organization to receive economic benefits. Extortion might involve threats of physical harm to the victim’s reputation or family (Wells Citation2011). A conflict of interest occurs when an individual or an organization exploits their professional capacity for personal or business benefit (OECD Citation2007). Favouritism means giving unfair preferential treatment to a specific individual(s) at others’ expense while performing public duties (Asencio Citation2018). Nepotism is another form of favoritism based on acquaintances and familiar relationships. Someone in an official position exploits their power and authority to provide a job or favor to a family member or friend at others’ expense (Fazekas Citation2017).

Methodology

The research questions addressed by this general review are: (i) what are the forms of fraud in football? (ii) how is football fraud perpetrated (iii) why is football fraud committed? (iv) How to counter football fraud? To answer these research questions, 200 academic peer-reviewed journal articles from 2000 to 2022 were reviewed using multiple search engines and databases for relevant papers. This includes JSTOR, Wiley Online Library, SCOPUS, EBSCOhost Business Source Premier, ProQuest, Elsevier ScienceDirect, Emerald Insight, Springer Standard Collection, Sage Journals Management, Allen Press American Accounting Association, IEEE Open Access Journals, and Conferences, and Taylor & Francis Open Access.

Following the approach of Moll and Yigitbasioglu (Citation2019), the review was not limited to a journal list. Still, attention was paid to papers published in leading accounting journals cited in the Association of Business Schools Academic Journal Guide 2021. Only peer-reviewed academic articles written in English were considered in this paper and some textbooks. The review comprised multi disciplines ranging from sports, accounting, ethics, and governance to economics, sociology, information technology, and law. To identify relevant studies, paper titles, keywords, abstracts, and primary texts were searched for these terms. When a relevant paper was identified, the reference list was examined to ensure that other vital contributions were not missed. Afterwards, the keywords were refined based on how fraud in football was described in these articles. This process helped identify and search keywords relevant to the first research question: Ticket fraud, match-making, tax fraud, unauthorized cash payment, price-fixing, overbilling, and investment fraud.

For the first and second questions, “What are the forms of football fraud and how it is committed?” only studies focusing on fraud in football were included in the review. Based on the definition and taxonomy of fraud discussed in section 2, the search started by using the following keywords: Fraud AND football; manipulation AND football; deceit AND football; deception AND football; misstatement AND football; misappropriation AND football; theft AND football; corruption AND football; bribery AND football; illegal gratuities AND football; extortion AND football; favoritism AND football; Nepotism AND football; crime AND football; financial fraud AND football; fraudulent financial reporting AND football. The final search yielded a total of 40 peer-reviewed academic articles.

To address the third question, “Why is fraud committed in football?” only studies exploring fraud risk factors in football were considered using the following keywords: Fraud risk factors AND football; fraud risk AND football; fraud factors AND fraud; risk AND football; motives, fraud, AND football; opportunity, fraud, AND football; rationalization, fraud, AND football; ethics AND football; governance issues AND football; issues AND football; accounting AND football; finance AND football; integrity AND football. The exact keywords were used with “soccer” replacing “football” and without both terms to understand why fraud is committed. The search yielded 95 peer-reviewed academic articles.

Regarding the fourth question, “How can football fraud be countered?” the search included studies covering mitigating fraud risk in football. The following keywords were used: risk management AND football; fraud prevention AND football; fraud detection AND football; risk assessment AND football; countering fraud AND football; mitigating fraud AND football; fraud deterrence AND football; identifying fraud AND football; curtailing fraud AND football. The search yielded 65 peer-reviewed academic articles.

Results

The forms and methods of football fraud

As explained in section 2 of this paper, fraud against organizations can be perpetrated by insiders or outsiders. Insider fraud includes corruption, asset misappropriation, and financial fraud. The findings show no evidence of external fraud reported in the literature. However, insider fraud, particularly corruption in all its forms, is well documented in the literature. There is minimal evidence of other insider fraud types, such as asset misappropriation and financial fraud, and even fewer studies discussing fraud against individuals. This study summarizes the forms and methods of fraud in football in below.

Table 1. Forms and methods of fraud in football.

Fraud against organizations - insider fraud

Corruption

The review shows evidence of all corruption forms in football, including bribery, match-fixing, illegal betting, price-fixing, favoritism, conflict of interests, and extortion. Gee, Brooks, and Button (Citation2011) report many international examples of referees being bribed with expensive watches, holidays, and female companies or working with criminal elements to defraud bookmakers. Club owners bribe officials to place a referee to look upon their team favorably in a forthcoming match. Liu et al. (Citation2019) identify three forms of bribing referees to manipulate matches in China: paying off referees, manipulating referees by football association officials, and investing in emotional bonds.

Bribery is at the heart of match-fixing scandals involving betting or gambling (Bag and Saha Citation2011). Match-fixing has been the focus of the literature and involves manipulating an outcome or contingency by competitors, teams, sports agents, support staff, referees and officials, and venue staff (Spapens and Olfers Citation2015). Match-fixing goes hand in hand with sports betting, as the participants decide to fix the match bet money on a particular outcome. Players could conspire to lose a football match, score the correct number of goals, miss a penalty, get booked, or be sent off to gain from gambling (Gee, Brooks, and Button Citation2011). In the Rovaniemen palloseurary football club in Finland, nine players took bribes from one individual between 2008–2011, with the players receiving bribes from between €1,000 to €40,000, allowing the briber to ultimately make a profit of €150,000 through placing bets on those games (Kimpimaki Citation2018). Joel, Turner, and Hutchinson (Citation2018) find that illegal player payments have become increasingly commonplace in Australian football and that champion footballers are taking bribes to “play dead.” Constantin and Stănescu (Citation2021) discussed that controlling and winning football matches in Romania were based on intimidation, abuse, and match-fixing. Equally, other studies reported that match-fixing is common practice in Malta (Aquilina and Chetcuti Citation2014), Greece (Numerato (Citation2016), and Belgium (Visschers, Paoli, and Deshpande Citation2020).

Favouritism also seems familiar in the football culture. Rocha et al. (Citation2013) found that referees systematically favor home teams by setting more extra time in close matches in which home teams are behind in the Brazilian Championship. Kotchen and Potoski (Citation2014) uncover that football coaches in the National Collegiate Athletic Association favor their team when they stand to gain more financially. Additionally, coaches rank teams they defeated more favorably, making their team look better than their opponents. Erikstad and Johansen (Citation2020) examined whether Norwegian Premier League referees are biased by a team’s success when awarding penalties. They found that successful teams were more likely to receive an incorrect penalty than their opponents. Data analysis of the top five European leagues from 2011–2012 to 2017–2018 reveals that referees award significantly more yellow and red cards to the opponents’ players in England. In Italy, Germany, and Spain, significantly fewer yellow cards and total booking points are given to top team players (Audrino Citation2020). Watson (Citation2013) reveals that home teams win more often and receive favorable treatment from umpires in the Australian Football League.

Conflicts of interest within football take various forms. Scholars (Dorsey Citation2015; Stone and Rod Citation2016) note the conflict of interest FIFA faces when allocating places in World Cups, suggesting FIFA’s focus on financial gain rather than transparency and integrity in the allocation process. Geeraert (Citation2015) suggests that the EU and FIFA face conflicts of interest: FIFA’s goal of having constructive dialogue with EU member states to gain leverage and maintain its autonomy, and the EU’s position of maintaining respect for that autonomy when instead, it could increase its leverage to protect its autonomy over member states. Hamil et al. (Citation2010) note the conflict of interests in the Italian case where former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi owned Italy’s largest and most successful club, AC Milan, and Italy’s largest media company, Mediaset. Using his political power, Silvio reduced the requirements for football clubs concerning financial transparency, regulation, and licensing problems. AC Milan, implicated in the Calciopoli scandal, appealed its initial punishment of a 44-point deduction to an 8-point deduction, allowing them to qualify for the Champions League and eventually win it. Rocha et al. (Citation2013) highlight the conflict referees face, mainly when concerned with their career prospects, as corrupt referees get promoted to top games. Other researchers (Baugh et al. Citation2020; Cohen, Lynch, and Deubert Citation2016) report that sports medicine clinicians and doctors face conflicts of interest in providing medical care to athletes (e.g., submitting false medical records to keep their jobs).

A few sources showed evidence of extortion. Meier and Garcia (Citation2015) discussed how FIFA abuses its monopoly to extract concessions from countries favoring its interests. Football has been used as a channel for criminal activities. Scalia (Citation2021) explores the case of the Sicilian crime syndicate (mafia) Cosa Nostra and how they extorted Palermo football clubs through threats and intimidation to protect their broader interests in the region.

Price-fixing was noted as occurring within the complex legal market of selling broadcast rights for football. Price fixing is an anti-competitive behavior occurring when football clubs conspire to fix the selling price of their broadcast rights. This practice may prevent individual competition and raise market entry barriers. Cases of actual price-fixing in football-related matters have attracted legal attention, particularly in the EU. Juska (Citation2014) argues how limited legal instruments within the EU’s jurisdiction prevented sufficient compensation from being paid to victims of a price-fixing cartel concerning replica football shirts. Bass and Henderson (Citation2015) studied the case, suggesting that of the 1.2–1.5 m shirts sold by those in the cartel (naming JJB, Manchester United, and Umbro as those being complicit), only 1,000 shirts received any compensation, less than 0.1% of the total sales.

Asset misappropriation

Some forms of asset misappropriation in football are reported in the literature. In particular, payroll fraud, where football players commit drug test cheating, and clubs perpetuate salary cap breaching (Masters Citation2015). Neri et al. (Citation2021) study of the buying and selling of Italian players in Serie A between 2005–2018 confirmed asset manipulation behaviors. Marquis and Soulie (Citation2022) found that football players purchase fake follower accounts on social media to inflate follower count, which, in turn, inflates player value in transfer fees by an average of 6%, or approximately €650,000. Another form of payroll fraud is age fraud: older yet young-looking and more experienced players enter age-specific tournaments (Makinde, Odimegwu, and OloOlorun Citation2018).

Issues of overbilling within football did not receive much academic attention but were used as case studies in broader discussions on the investigation and policing of fraud and corruption. Gottschalk (Citation2014) explored the success of fraud examiners investigating financial crime in Norway, noting two case studies. The first was building a new stadium in Briskeby, with the Lynx law firm suspecting there had been deliberate overbilling for the construction work of the stadium itself. The second was a case of clubs in the Norwegian league changing clubs without clubs paying each other transfer money. Da Cunha and Bugarin (Citation2015) found evidence of overbilling accusations in Brazil’s Maracanã Stadium as part of the 2014 World Cup. Risaliti and Verona (Citation2013) noted how in the 2001–2002 season, the most prominent Italian clubs (i.e. Inter Milan, Juventus, Lazio, A.C. Milan, and Roma) overestimated the value of players’ registration rights to manage wage costs.

Another form of asset misappropriation in football is intellectual property theft, where football clubs’ insiders collude with criminals in pirate broadcasting for personal gain or selling unofficial products using ambush marketing campaigns (Pearson Citation2012). Other studies reported players and officials illegally manufactured and dispensed tickets in return for business favors (Gee, Brooks, and Button Citation2011).

Fraudulent financial reporting

Fraudulent financial reporting in football is committed through tax fraud, ticket sales manipulation, and players’ salaries, which is particularly prevalent in Greek football (Manoli, Antonopoulos, and Levi Citation2016). Neri et al. (Citation2021) conclude that football clubs competing in the Italian Serie A from 2005 to 2018 adopted earnings manipulation due to trading players’ economic rights. Mazanov et al. (Citation2012) found evidence of overstated share prices following the Italian Calciopoli scandal in the Juventus and Lazio clubs. Risaliti and Verona (Citation2013) reported overestimated values of players’ registration rights in Italy. Halabi et al. (Citation2016) found that most clubs in Australia engaged in fraudulent financial reporting before 1911 by misrepresenting player payments and that they suspect such practices continue to date.

Fraud against individuals (i.e., football players and fans)

A few studies report that football fans are duped into purchasing fraudulent tickets (Gee, Brooks, and Button Citation2011). Football players can be victims of investment fraud defrauded by individuals fraudulently posing as financial professionals (Brody et al. Citation2022). In other cases, fraudsters collect cash payments for a football player’s image rights without the player’s knowledge and consent (Gee, Brooks, and Button Citation2011).

Outside the club environment, deceptive “recruitment” of players for financial gain is an area of football with some troubling case studies and stories. De Sanctis (Citation2014) reported that some low-income families sell their homes to meet the club entry fee requested by “fraudulent entrepreneurs” who pose as having connections with major clubs, causing around 20,000 children in Europe to live on the streets. Another case covers fraud involving underage Nigerian players imported into Norway until they could be sold to English clubs.

Fraud risk factors in football

Criminologists assert that understanding the reasons behind fraud could help organizations design effective counter-fraud measures (Wells Citation2011). Much of the current understanding of why individuals commit internal fraud is grounded in the traditional fraud triangle theory that Donald Cressey established in 1950. Cressey found that three indicators must exist for fraud to take place: (i) motive, (ii) opportunity, and (iii) the ability to rationalize fraud.

The motives for committing fraud can be financial or non-financial. Examples of financial motives include obtaining organizational finance, avoiding bankruptcy, personal financial needs, keeping the job, getting promoted, or the desire to receive a bonus. Non-financial motives include greed, ego, the desire to please investors, beating analysts’ forecasts, competition, or revenge (Kassem Citation2018). The opportunity for fraud is the chance of committing fraud without being caught, and it comes about by weaknesses in an organization’s internal controls and governance mechanisms. In its latest global fraud study, the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (Citation2022) reports that more than half of all internal frauds occurred because of an internal control deficiency, including a lack of internal controls, an override of existing controls, and a lack of management monitoring. Other examples of weak controls and governance mechanisms include lack of accountability, weak penalties, the concentration of power in the hands of one or a few individuals, weak accountability, an ineffective board of directors, and inadequate safeguards over assets and records (Kassem Citation2021). A rationalization justifies fraudulent behavior due to an individual’s low integrity (Albrecht, Howe, and Romney Citation1984). Albrecht et al. emphasized the significance of integrity as a fraud factor, arguing that individuals with low integrity are more likely to rationalize fraudulent and unethical behavior. From that perspective, they suggested replacing rationalization with integrity when assessing fraud risks. Therefore, this section focuses on the motives, opportunities, and integrity issues that enable fraud in football. It summarizes various fraud risk factors in football in below.

Table 2. Fraud risk factors in professional football.

The motives for committing fraud in football

The paper identifies several motives for committing fraud in football, including issues in financial and sporting performance, competitive balance, and financial regulations, among other motives.

Issues in financial and sporting performance

When discussing financial performance, it is first helpful to understand the major source and location of revenue within professional football. As Plumley, Wilson, and Shibli (Citation2017) make clear, the ‘Big Five European leagues (English, German, Spanish, Italian, and French) are the primary financial drivers of the sport. In 2013–14, they had a combined revenue of €11.3bn. Revenue of this size incentivizes excessive spending to justify and maintain their position, which means setting sporting and financial targets. Indeed, the linked goals of sporting and financial performance are a continuum along which clubs place themselves and move backwards and forwards to a greater or lesser extent. The “brand” of the club itself is vital in building success. Rohde and Breuer (Citation2016b) found that the top 30 clubs across the Big Five leagues draw their financial success from national and international sporting success, brand name value, and foreign private team investments.

Some concerns were raised that most football clubs remain overvalued in capital markets, not helped by high demand from a wide variety of motivated investors for their shares, all of whom expect additional benefits besides dividends and stock appreciation (Prigge and Tegtmeier Citation2019). The impact of foreign owners, particularly in the Premier League, has a mixed effect on the health of clubs. Rohde and Breuer (Citation2016a) suggest that whilst team investment improves under such owners, the overall profits of the club decrease. Conversely, research comparing the French and English leagues between 2006–2012 found that French clubs were increasingly becoming characterized by a private-ownership model and that foreign investors were increasingly taking over English clubs. The consequences on financial efficiency between the two models were noticeable, with French clubs typically taking a loss of €6.4 m and English clubs generating a €7 m profit (Rohde and Breuer Citation2018).

Scelles et al. (Citation2016) found the significant metrics in the club’s financial performance to be operating income, player value, stadium age, club ownership type, foreign ownership, supporter numbers, the income of those supporters, and historical performances, as all are having an impact on European clubs. They note the “chicken and egg problem” this can create. To attract high-value players that drive revenue, clubs need to offer high salaries, which can impact their ability to perform financially. Non-traditional metrics such as social media engagement with major clubs are noted as a source of fan support and engagement that could have a financial influence (Scelles et al. Citation2017). However, the most significant driver of income and metric of financial success is undoubtedly TV rights (Scelles and Andreff Citation2017). Scelles, Dermit-Richard, and Haynes (Citation2020) explored the challenges broadcasters faced when spending their combined £8.3bn (between 2016–19) on the English Premier League rights alone. Broadcasters experienced a virtuous circle of competition between channels for rights, committing more money and desiring more exclusive clubs and games. This drove more competition between channels, resulting in more money being committed. Similarly, concerning the buyers of the TV rights, Feuillet, Scelles, and Durand (Citation2019) note that in the French and English leagues, broadcasters commit more resources to broadcast the games of the major teams, paradoxically pushing up prices for consumers and resulting in a smaller market in which to fund those rights.

Given the financial stakes and pressures to remain financially competitive, it is unsurprising that some clubs may over-leverage their position. Indeed, failing to regulate and manage finances adequately can devastate a club, forcing them to commit fraud to maintain its financial viability. The fear of insolvency, bankruptcy, and financial distress could motivate football clubs to commit fraud. Bag and Saha (Citation2011) find that fear of zero profit is at the core of the decision to offer a bribe. Schubert and Harald Dolles and Professor Sten Söderman (Citation2014) argues that clubs are torn between short-term sporting success and the overall long-term financial solvency required by the main regulatory body. In this context, club managers may be tempted to engage in fraud to comply with UEFA regulations to maintain financial and sporting performance. The threat of extinction due to failure encourages fraudulent means in Greek football (Manoli, Antonopoulus, and Bairner Citation2019). The need to obtain funding could motivate football clubs to commit fraud. Dimitropoulos, Leventis, and Dedoulis (Citation2016) found that at the expense of accounting quality, club management seeks to promote the image of a financially robust organization to secure licensing and, consequently, much-needed funding from UEFA.

Fraud risk will likely remain high, given the current evidence of financial distress in football. Acero, Serrano, and Dimitropoulos (Citation2017) report that the financial situation of the clubs continued to deteriorate at an ever-increasing rate, with the level of aggregated debt of the European football clubs reaching multimillion-euro figures and many of the clubs on the verge of bankruptcy. Plumley, Serbera, and Wilson (Citation2021) analyzed English Premier League (EPL) and English Football League (EFL) championship clubs from the period 2002–2019 to anticipate financial distress with specific reference to football’s Financial Fair Play (FFP) regulations. The results show significant financial distress amongst clubs and that the financial situation in English football worsened during COVID-19. Cox and Philippou (Citation2022) explored the financial accounts of Premier League clubs from 1993–2018 to gauge just how exposed they were to economic shocks such as the global financial crisis, finding that only Arsenal was resilient enough to withstand a shock. Feuillet et al. (Citation2021) discussed that lower-earning clubs are incentivized to take out loans to fund their recruitment strategy and remain competitive. This means greater financial risk suggesting that the broader threat of insolvency remains large.

This section’s financial and sporting performance discussions highlight the pressure football clubs may face. The least of a club’s problems is how they present themselves as a brand that attracts fans and investors: they must also contend with financial investors, not all of whom may act in the club’s best interests. Constant pressure remains to be financially viable and drive revenue, particularly from sources such as ticket sales and TV rights, with the consequences of failure (insolvency) being catastrophic. Despite this, intense financial competition remains a pressing matter for clubs. Such pressures could force football clubs to commit fraud to remain financially competitive, obtain financing, or avoid bankruptcy and insolvency. Given the stakes, financial pressure undoubtedly leads to sporting performance pressure that could result in match-fixing. Managers, fairly or unfairly, bear the brunt of fan and media backlash when a team’s performance is below the bar, with the constant push for points and victories a motivating factor. Indeed, a team’s failure or success on the pitch can have consequences for fans and fan engagement with the overall product, which could be a motive for committing fraud.

Issues in competitive balance

The desire for all teams to be competitive to enhance the financial benefits is of note. Teams face pressure to enhance the quality of their play, which undoubtedly creates further sporting and financial pressures. Such an arms race impacts fans and their desire to engage with the sport. Competitive balance (CB) can help explain this arms race. CB is defined by Scelles et al. (Citation2013) as “the necessity of equilibrium between the teams in a league to guarantee uncertainty of outcome and thus generate public demand,” a task made difficult by teams having unequal resources to draw upon, thus justifying redistributive mechanisms. Scelles et al. (Citation2013) also discussed the limits of CB: An unbalanced championship can be potentially more interesting than a more balanced one if each team has a sporting stake to defend.

When looking at European men’s first tiers, Scelles, Francois, and Dermit-Richard (Citation2022) note common determinants across the countries and add their own to the broader European context. In particular, revenue sharing, differences in drawing power, prize money, talent market, sports content, climate, economic power, tradition, timing, number of clubs, financial regulation, and international performance all impact CB; however, economic power (specifically GDP) was highlighted as the most positive influence on CB. Scelles and Francois (Citation2021) found that CB had a significant positive impact on stadium attendance in countries with high-income inequality, suggesting that “fans look for the (in)equality their national economy does not offer.”

Some case studies explore the impact of CB in the broader game and what can influence its otherwise stringent attempts at equilibrium. Plumley and Flint (Citation2015) were critical of the seeding of UEFA Champions League group stages between 1999–2014. They found that the groups were incredibly competitively unbalanced and favored those teams constantly placed in the higher seeding pot, further entrenching their chances of advancement. Ramchandani et al. (Citation2018) took a longer-term view of the five major European leagues to determine how levels of CB had changed between 1995–2017, reporting that the French Ligue 1 had emerged as the most balanced, with a significant decline in the English, Spanish, and German leagues. A study of the impact of the Premier League on CB of the wider English leagues found that since 1992 there has been a decline in CB in the top three divisions. This was driven by greater rewards for winning the title, promotion, or relegation, and the financial gap between the Premier League and other leagues has widened substantially (Plumley, Ramchandani, and Wilson Citation2018). Indeed, they even expressed concerns that the long-term decline of CB could result in the emergence of dominant “super clubs”, incentivized to break away further into a super league (Plumley et al. Citation2022). A more focused study of the Premier League itself determined that a 20-league team “compromises the overall level of CB in comparison with a league comprising between 10 and 19 teams” but was unable to determine the “ideal” league size that would ensure CB (Ramchandani et al. Citation2019).

The financial considerations of CB draw some case studies. Pawlowski, Breuer, and Hovemann (Citation2010) were critical of the influence of the Champions League on the “Big Five” leagues, finding that CB in domestic leagues was declining due to the payouts received by those participating clubs. Those English clubs relegated from the Premier League and into the Championship were reducing CB further, with parachute payments being the primary factor. Those receiving payments were much more likely to be promoted back into the Premier League, further disadvantaging those clubs that had never won promotion (Wilson, Ramchandani, and Plumley Citation2018). Plumley, Ramchandani, and Wilson (Citation2019) looked at the consequences of UEFA’s Financial Fair Play (FFP) on CB, finding that imposing rules designed to improve solvency caused a decrease in CB in Spain, Germany, and France.

Scelles, Desbordes, and Durand (Citation2011) advance competitive balance by advocating for ‘competitive intensity (CI), placing a greater focus on the “absolute and relative quality of the teams and importance of the matches. By taking the French Ligue 1 as a case study, Scelles et al. (Ibid) find that Ligue 1, at that time, was not an ideal environment for competitive intensity, advocating greater “maximal suspense and dramatization,” especially if revenues such as television rights are to be maximized. CI was similarly used to explore a variety of case studies, aiming to understand the determinants of drivers of key economic metrics. Scelles et al. (Citation2013) tested CB and CI against each other to determine which was a greater driver of attendance, finding that greater levels of uncertainty with competitive intensity result in greater engagement, particularly concerning the home team. A further study by Hautbois, Vernier, and Scelles (Citation2022) found that the influence of CI on attendance was observable across seasons (especially when competing for a prize) and not a temporary factor, with interest peaking toward the end of the season, especially if more teams are involved in the outcome of a championship. They noted that CI increased attendance for those teams in relegation instead of those fighting for the championship. By examining the impact of prizes on the 2008–11 period in French Ligue 1, the competitive intensity was used to demonstrate all sporting prizes result in higher fan attendance, particularly in European competitions such as the Europa League (Scelles et al. Citation2016). Both CI and CB were used to explore the impact of changes to UEFA’s men’s Euro 2016 tournament, praising the increase in both, with the Euro 2016 final round highlighted as increasing in intensity (Scelles Citation2021).

It is clear from this discussion that Competitive Balance (CB) has outstayed its welcome: focusing on a balance between the teams was limiting financial opportunities, and those opportunities were eroding CB regardless. CB has undoubtedly given way to Competitive Intensity (CI), with its greater emphasis on predictability and stakes. CI is helping to drive those higher revenues desired by clubs, even if it risks diluting competitiveness to all but a small elite. Competitive balance was previously concerned with ensuring a “fair” game; however, the ever-growing importance of rewards and “stakes” caused this to give way to competitive intensity, which was a higher driver of fan engagement and, thus, revenue. With the ever-growing sporting and financial stakes and pressures, the pressure on those clubs themselves to maintain these standards may raise broader questions about the integrity of clubs and increase fraud risk.

Issues in financial regulation

With more money than ever before flowing into the accounts of the “Big Five leagues and constant pressure to achieve sporting and financial success, it is unsurprising that financial regulation was needed. With Portsmouth becoming the first major English club to enter administration in 2010, Financial Fair Play (FPP) came into force among UEFA-member states shortly after in 2012, forcing clubs to financially ‘break even’ and preventing them from spending more money than they generate. However, Plumley, Wilson, and Shibli (Citation2017) were skeptical of FPP’s impact, other than to widen the gap between the more established clubs that regularly compete in European competitions and those that do not. Recent research confirmed this suspicion, and by 2019, FPP had a financial impact on the health of clubs; particularly, English Championship clubs were suffering financial distress (Plumley, Serbera, and Wilson Citation2021). Francois et al. (Citation2021) reported that players” wages decreased significantly in English and French clubs, except those regularly competing in Europe, due to FPP impact.

Other studies doubted FFP’s suitability or ability to achieve its aims. Bachmaier et al. (Citation2018) use the English Premier League and German Bundesliga as case studies, finding that FPP would impact the latter far more substantially than the former, and those broader goals of assessing and monitoring requirements upon clubs are ineffective, endangering the project of FPP as a whole. Schubert and Lopez Frias (Citation2019) argued that FFP regulations represent the most restrictive regulatory intervention European club football has ever seen. It demands clubs to operate based on their football-related incomes. They suggested that the policy should go beyond the pragmatic goal of promoting financial sustainability and creating a level playing field; otherwise, it should not be labeled ‘fair play. Unfortunately, the financial distress imposed on clubs due to the need to comply with FFP could motivate fraud.

FFP is not the only regulation binding professional football clubs. Dermit-Richard, Scelles, and Morrow (Citation2019) point out the contradictions of the French National Direction of Management Control (DNCG), which is its greater focus on solvency, as opposed to the profitability concerns of FFP. With DNCG dating back to 1990, it has resulted in a situation where a French club can be DNCG-compliant, but in breach of FFP rules, with most French clubs falling into this trap. Evans, Walters, and Tacon (Citation2019) provide an assessment of the effectiveness of the Salary Cost Management Protocol, a form of financial regulation introduced by the English Football League in 2004 to improve the financial sustainability of professional football clubs. They found that it failed to improve clubs’ profitability or solvency in League Two.

Other motives

Personal financial need or gain coupled with low pay (Forrest Citation2012; Peurala Citation2013), fear of aging, and financial insecurity (Hill Citation2015) could motivate players, referees, and their leaders to commit fraud. Hill explained that given the high social and sexual status that players enjoy, match-fixing is more likely to be committed by older players nearing the end of their careers, fearing the loss of status and pay. Moriconi and De Cima (Citation2021) added that referees’ desire to keep their job might motivate them to engage in fraud. Religious ideologies, the influence of gambling networks, gambling addictions, and officials’ perceived corruption could also motivate football fraud. Nassif (Citation2014) explores broader corruption in Lebanon, finding that the country’s religious, multi-confessional political structure results in corruptive behavior. Spapens and Olfers (Citation2015) conclude that gambling addiction and the rise of online gambling motivate corruption. Hill (Citation2010) suggests that illegal solid gambling networks, high levels of relative exploitation of players, and perceived corruption of officials were strong motivating factors for match-fixing. Similarly, Hay (Citation2018) and Visschers, Paoli, and Deshpande (Citation2020) note football’s growing vulnerability to match-fixing is driven partly by the enormous financial stakes and the growing influence of betting companies.

Poor working conditions for players and referees, restrictions over player payments, and the desire to win the championship are noted as motives for fraud. Marchetti et al. (Citation2021) indicate that poor working conditions for players and referees are the primary motive for match-fixing in Brazil. Yilmaz, Manoli, and Antonopoulos (Citation2019) study into the Turkish leagues reported that the desire to win the championship motivates match-fixing. The pressure to achieve unrealistic targets placed on managers and football players by football fans and journalists could motivate fraudulent behavior (Fry, Serbera, and Wilson Citation2021).

The opportunities for fraud in football

Recent studies found that governance failures within football governing bodies and clubs promote opportunities for fraud (Moriconi and De Cima Citation2021). Nevertheless, the standards of corporate governance in football clubs are significantly below those of listed companies (Michie and Oughton Citation2005), and there is less emphasis on governance mechanisms and accountability (Anagnostopoulos and Senaux Citation2011). This section sheds light on controls and governance issues contributing to fraud risk in football.

the lack of accountability

There is a direct relationship between effective accountability and fraud deterrence (Dillard and Vinnari Citation2019), and the lack of accountability in football increases the opportunity for fraud. Boudreaux, Karahan, and Coats (Citation2016) argue that FIFA’s corruption emanates more from a lack of punishment. There does not appear to be an institutional process under which its president and the executive committee can be held accountable. The reasons for this low degree of accountability pertain to FIFA’s excessive power. FIFA does not directly answer any country, and although it is incorporated under Swiss law, very little supervision by Swiss authorities was conducted until May 2015. FIFA can punish national governments that try to supervise their football federations by banning countries from qualifying for the World Cup.

The lack of accountability in football extends beyond FIFA. Lash (Citation2018) found that Polish players engaged in match-fixing because the risk of punishment was low. Others reported how rare fraud convictions are in China (Liu, Dai, and Wang Citation2019), Argentine (Paradiso Citation2016), and everywhere else (Kimpimaki Citation2018). Manoli, Yilmaz, and Antonopoulos (Citation2021) added that despite individuals being implicated in scandals, UEFA punished the clubs instead and showed a reluctance to pursue the individuals in question due to the existing relationships with governing officials and politicians. Gottschalk (Citation2015) revisits the scandals in Norwegian football of the Briskeby stadium and payments for the transfer of players to determine the consequences of the fraud being exposed by private investigators. For the former, two managers were blamed for budget overruns; and for the latter, there were no consequences.

The lack of public accountability is another fraud enabler. Holzen and Meier (Citation2019) suggest that when the FIFA scandal became public, there was initially significant interest, but this interest declined over time. In some countries, journalists are corrupt and unlikely to hold fraud perpetrators accountable in the football industry, as Ncube (Citation2017) highlighted, referring to the case of Zimbabwe.

The lack of anti-fraud controls

Anti-fraud controls are vital for mitigating fraud risk. However, football clubs are ill-prepared to counter fraud. There is a lack of a clear and effective counter-fraud strategy in most football clubs (FATF Citation2009) and no single body has a robust anti-bribery policy (Philippou and Hines Citation2021). The football industry also lacks adequate monitoring, a crucial anti-fraud control (Association of Certified Fraud Examiners Citation2022). European clubs tend to have insider-dominated boards lacking independent executive directors, which results in low monitoring and provides an opportunity for managers’ bias and fraudulent behavior (Dimitropoulos and Tsagkanos Citation2012). Hamil et al. (Citation2004) found that less than a quarter of football clubs had an internal audit committee, and even where clubs had an audit committee, almost one-third of those clubs had no regular board risk assessment review. The concentration of power in the hands of one or a few individuals increases the risk of fraud and abuse (Kassem Citation2021). However, FIFA executives can choose whether and how resources are allocated, accept bids for World Cup sites, and are routinely criticized for demanding bribes. Although Switzerland monitors FIFA, this does not happen in practice due to FIFA’s excessive power (Boudreaux, Karahan, and Coats Citation2016).

Other controls and governance issues

Nowy and Breuer (Citation2017) suggest that the more formalized and reliant the grassroots club is on volunteers, the more potential opportunities for corruption arise. Di Ronco and Lavorgna (Citation2015) argue that football involves various misconducts and corrupt activities due to its significant turnover. Michie and Oughton (Citation2005) found that there is improper information disclosure, lack of transparency in the appointment of directors, unbalanced board composition, lack of induction and training of directors, lack of risk management, and no consultation with stakeholders in football clubs. Shalaby (Citation2016) noted that the football profession lacked an awareness of the consequences of corruption which is a significant contributor to fraud risk.

Integrity issues in football

Top management plays an essential role in mitigating fraud risk in any organization. The corporate culture created by top management, otherwise called the “control environment” or the “tone at the top,” is a critical component of an entity’s internal control as it sets the tone of an entity and influences the control consciousness of its people (Ramos Citation2004). However, the systemic use of bribing within FIFA represents an informal but systematic means of governance in FIFA and an accepted aspect of FIFA’s culture (Gill, Adelus, and de Abreu Duarte Citation2019; Pouliopoulos and Georgiadis Citation2021).

In building strong integrity cultures, organizational leaders must walk the talk and lead by example. Although FIFA stated that it has a zero-tolerance policy toward wrongdoing and is committed to good governance principles (Lee Citation2016), its culture was wholly exposed as fraudulent when 26 top FIFA officials were arrested in Zurich and Miami in 2015 (Mandel Citation2016). Additionally, there were allegations that a member of FIFA’s ethics committee received bribes from a member of the executive committee (Boudreaux, Karahan, and Coats Citation2016). Even when FIFA attempted to repair its image in the media, studies found that it relied heavily on a denial strategy to avoid responsibility (Ibrahim Citation2017; Onwumechili and Bedeau Citation2017) when the corruption was organized and purposeful (Boudreaux, Karahan, and Coats Citation2016).

Integrity issues in football do not just stop at FIFA. Wozniak (Citation2018) found the Polish Football Association implicated in fixing 638 games resulting in 452 convictions, and corruption is institutionalized. Carin and Terrien (Citation2020) believe that football clubs are vessels through which fraud is conducted and are lucrative for fraud criminals. Boeri and Severgnini (Citation2011) uncovered that referees willing to engage in match-fixed were typically promoted to top games. Their reputation as a referee was not negatively affected by their engagement in match-fixing. Liu et al. (Citation2019) ‘s study of the Chinese case revealed that the bribing of referees is considered an “unspoken rule” and one given tacit acknowledgment by clubs. Considering the Italian Calcipoli case, Di Ronco and Lavorgna (Citation2015) conclude that corruption was endemic, fostered, and even encouraged by a climate of peer- and public tolerance in Italy.

Countering football fraud – a holistic framework

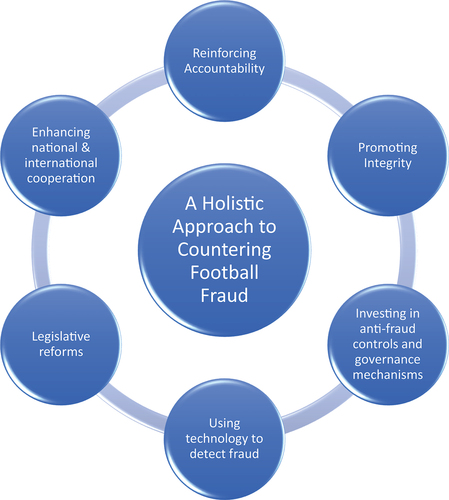

The studies reviewed in this paper recommended various methods for countering fraud in football. The analysis of the results highlights seven themes concerning the methods for countering fraud in football: (i) reinforcing accountability, (ii) promoting integrity, (iii) investing in anti-fraud controls and governance mechanisms, (iv) using technology to detect fraud, (v) legislative reforms, and (vi) enhancing national and international cooperation. Methods relevant to these themes are then placed under each related theme. These themes and the specific methods under each theme were then used to develop a holistic framework for mitigating fraud risk in football, illustrated in and below.

Table 3. A holistic framework for countering football fraud.

Reinforcing accountability

Enhancing accountability is a must to tackle fraud in football. This can be achieved by imposing harsher punishments for fraud perpetrators (Boudreaux, Karahan, and Coats Citation2016), preferably prosecution instead of financial penalty, to reduce the opportunity for fraud (Kassem Citation2021). Another way is to enhance accounting practices in the football profession. Accounting is a subset of accountability, generally linked through disclosure and transparency and has a vital role in enhancing integrity and accountability (Everett, Neu, and Rahaman Citation2007). The World Bank (Citation1994: 14) suggested that countries wanting to fight fraud and improve their accountability should:

Implement an effective and integrated financial management information system.

Develop a professional base of accountants and auditors.

Adopt and apply internationally accepted accounting standards.

Empower a robust legal framework for supporting modern accounting practices.

Further research by Prigge and Tegtmeier (Citation2020) recommends that football stocks be considered an asset class of their own and unattractive to traditional “pure” financial investors. Follert et al. (Citation2020) call for transparency in allocating budgets and clear guidelines for FIFA officials and bodies about their rights and accountability. Other suggestions include redistributing broadcasting rights equally and incentivizing cost-reduction targets, placing a hard salary cap at the league level to control costs, and revisiting FFP regulations to ensure financial sustainability in European football (Plumley, Serbera, and Wilson Citation2021). Dimitropoulos, Leventis, and Dedoulis (Citation2016) added that the UEFA should consider that, in a financially distressed industry focused on achieving success in the field of play, the imposition of regulatory monitoring tied to accounting data inevitably leads to a loss of organizational credibility and transparency. Hence, UEFA’s intervention should be accompanied by the implementation of a corporate governance framework.

There should be greater emphasis on monitoring and public awareness of fraud and its consequences. Cottle (Citation2019) suggests reducing responsibilities for FIFA’s governing bodies and applying more stringent monitoring of ethics adherence. Veuthey (Citation2014) proposes the implementation of a world integrity sports body involving the intervention of public authorities. De Sanctis (Citation2016) calls for establishing a supervisory monitoring body, obligating officials to report suspicious transactions, and requesting greater transparency in transferring players and ownership of clubs. Schubert and Harald Dolles and Professor Sten Söderman (Citation2014) suggests that UEFA prevent noncompliance with FFP by limiting opportunities and providing information and education. Seda and Tilt (Citation2020) propose disclosing fraud-related activities in annual reports to raise public fraud awareness.

Promoting integrity

Promoting integrity starts at the organization’s top. If top management seems unconcerned about ethics, employees will find it an opportunity to defraud the organization (Halbouni, Obeid, and Garbou Citation2016). An effective tone at the top comprises a management team with a consistent message regarding ethical values and appropriate behavior, a reduced perceived opportunity for fraud, and the introduction of influential, honest managers (Davis and Pesch Citation2013). Boudreaux, Karahan, and Coats (Citation2016) suggest appointing FIFA executives raised in low-corruption countries because research has shown that corruption is a learned behavior. Constandt and Willem (Citation2019) recommend that top management in football clubs and federations set an ethical example of how their employees should behave in the workplace and provide a safe reporting mechanism for reporting fraud. Fighting fraud requires ethical practices that deliver the right message about a robust ethical culture within the organization (Neu, Everett, and Rahaman Citation2015). Appointing leaders with integrity will make this task achievable as they will lead by example and discourage and severely penalize fraudulent behavior (Kassem Citation2021). Whistleblowers who do not use hotline mechanisms are most likely to report their concerns to their direct supervisors (Association of Certified Fraud Examiners Citation2022), so appointing leaders with integrity matters.

Promoting an organization’s integrity culture is crucial. It requires fostering an anti-fraud culture that includes mandatory employee fraud awareness training, establishing an easily used and secure whistleblowing process, and rewarding integrity. It also necessitates taking corrective actions when raised by auditors and audit committees, treating employees fairly and respectfully, and providing fair pay, workload, and promotions. Besides, it necessitates investing in robust anti-fraud controls and risk management systems, holding individuals accountable for their responsibilities, and prosecuting fraudsters rather than firing them (Kassem Citation2021). Having an ethical code of conduct with zero tolerance for fraud is paramount. The ethical code should cover accepting gifts and consistently implementing disciplinary processes to violate anti-fraud policies (Kassem Citation2021). Constandt, De Waegeneer, and Willem (Citation2019) suggest that football clubs incorporate their ethical code into a broader ethical programme. The code should focus on ethical leadership and whistleblowing protection to encourage fraud reporting.

Investing in anti-fraud controls and governance mechanisms

Investing in anti-fraud controls and governance mechanisms is vital for mitigating fraud risk (Kassem Citation2021). Some studies propose adopting a zero-tolerance policy on fraud internally and externally and setting up a code of conduct for all football staff (Bozkurt Citation2012). The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (Citation2022) identifies a code of conduct as one of the effective anti-fraud controls. The code of conduct should focus on the transparency of financial information and corporate governance practices, particularly the structure of the boards of directors, the degree of independence of its members, and their rotation (Acero, Serrano, and Dimitropoulos Citation2017). The code should also stipulate the dangers of fraud, the sanctions for engaging in fraud and encourage reporting fraud via an adequate whistleblower protection mechanism (Bozkurt Citation2012). The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (Citation2022) found that maintaining an anonymous fraud reporting mechanism increases the chances of earlier fraud detection and reduces fraud losses. It recommends using multiple reporting channels, including telephone, e-mail, and web-based, to encourage reporting fraudulent behavior. Recent studies emphasize the significance of setting up a dedicated whistleblowing hotline in football clubs (Visschers, Paoli, and Deshpande Citation2020) and FIFA to encourage fraud reporting (Philippou and Hines Citation2021).

The significance of anti-fraud education has also been noted. Murphy and Dacin (Citation2011) uncover that the lack of fraud awareness is a pathway to rationalizing fraudulent behavior. Nowy and Breuer (Citation2017) recommend educational programmes highlighting the dangers of corruptive behavior for the grassroots club. The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (Citation2022) found that fraud awareness training encourages tip-offs through reporting mechanisms. Visschers, Paoli, and Deshpande (Citation2020) recommend conducting fraud awareness campaigns and add that the language of fraud is essential in educational campaigns. In particular, Moriconi (Citation2018) suggests that a narrative change is needed to press the seriousness of the fraud issue. Philippou and Hines (Citation2021) recommend that FIFA clearly define bribery.

Monitoring is another crucial anti-fraud control. Watson (Citation2013) suggests appointing neutral umpires for all games and establishing an independent panel to oversee the development and selection of umpires. Moriconi and De Cima (Citation2021) recommend developing anti-match fixing policies and controlling the sport governing bodies externally and independently. Dimitropoulos and Tsagkanos (Citation2012) propose appointing independent directors to the boards of football clubs and their governing bodies as it could reduce fraud incidents (Frankel, McVay, and Soliman Citation2011; Ghafoor et al. Citation2019; Sharma Citation2004). Mandel (Citation2016) proposes publicly releasing financial accounts and strengthening the powers available to FIFA’s Ethics Committee. Adequate segregation of duties is also recommended. In particular, Cohen, Lynch, and Deubert (Citation2016) recommend separating the roles of physicians serving the player and those serving the club. Boudreaux, Karahan, and Coats (Citation2016) suggest reducing the FIFA executives’ power and allowing the supervisors to engage in merely advisory roles. Mandel (Citation2016) proposes adequate segregation of duties within FIFA to reduce the power in the hands of a small number of executives.

Improving the quality and integrity of financial reporting is another crucial anti-fraud control for the football profession. Accounting helps accomplish specific tasks within the corruption process, such as lengthening the accounting transaction chain to inflate the proceeds and fabricating invoices that make unusual accounting transactions appear normal (Neu et al. Citation2013). Miragaia et al. (Citation2019) recommend that clubs improve their control over the financial resources available due to the positive relationship between the sporting performance of clubs and their levels of financial efficiency. Auditors and audit committees could ensure the reliability of financial statements and help reduce fraud risk. DeZoort and Harrison (Citation2018) conclude that auditors are critical in managing organizational fraud risk, and fraud detection depend on internal auditors and external audit design (Ergin Citation2019). Buchanan, Commerford, and Wang (Citation2020) find that increased auditor scrutiny with communication to the board effectively reduces fraud risk. The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (Citation2022) found that surprise audits were associated with at least a 50% reduction in median loss and median duration of the 2110 fraud cases investigated. The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (Citation2022) asserts that having an internal audit department, an external audit of internal control over financial reporting, and an independent audit committee is among the standard anti-fraud controls.

Other anti-fraud and governance mechanisms include thoroughly scrutinizing subcontracting companies for organizing matches before granting them licenses, preventing matches organized for gambling-related activities, developing a comprehensive fraud prevention programme, and establishing a match-fixing disciplinary body (Bozkurt Citation2012). Philippou and Hines (Citation2021) advise that FIFA has a clear gift-giving policy, including specific reference to low-value gifts.

To protect football players against fraudulent investments, clubs should advise them to become more vigilant by conducting background investigations, conflict-of-interest checks, and reference checks and using experienced, reputable, independent third parties to perform due diligence (EY Citation2019). To protect Football Championships from intellectual property theft, Pearson (Citation2012) suggest restricting the access of clubs’ intellectual property to “Official Partners” and introducing legal and practical strategies to prevent the sale of unofficial merchandise and “ambush marketing” by other companies.

Using technology to detect fraud in football

A few studies suggest using mathematical and statistical models to detect fraud in football. Otting, Langrock, and Deutscher (Citation2018) constructed a model that utilizes odds and the volume placed in bets to identify suspicious matches and suggested that constant monitoring of such odds can improve the predictability of matches being fixed. Similar modeling by Forrest and McHale (Citation2019) used the real-time diverge of model and odds and market odds to try and predict where fixing was occurring, noting the need for an analyst to offer human judgment on whether the action was needed to address the discrepancy. Hamsund and Scelles (Citation2021) found that football fans prefer using the video assistant referee (VAR) at any point during the match to ensure integrity.

Legislative reforms

A handful of studies recommended legislative reforms to fight fraud in football. Nwosu and Ugwuerua (Citation2016) suggest stronger government-backed independent anti-corruption agencies, strengthening the penalties for financial crime, and empowering security agencies to investigate officials suspected of corruption. DiCenso (Citation2017) proposes domestic reform of Swiss legislation by giving authorities greater power to hold FIFA accountable. Enhancing the powers of these institutions is crucial, as the ability to correct the abuses of the most powerful requires power (Cooper and Johnston Citation2012). Bank (Citation2019) recommends strengthening the law for whistleblowers’ protection from retaliation. Others suggest regulating betting to undercut gambling syndicates (Forrest Citation2012) and introducing a global tax on sports betting gains to tackle illegal online betting (Andreff Citation2017). Lee (Citation2016) proposed placing FIFA on the list of international public organizations to allow the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977 to prosecute those engaging in foreign corruption.

Enhancing national and international cooperation

A few studies recommended strengthening national and international cooperation to fight fraud in football. Masters (Citation2015) suggests enhancing cooperation between governments and sports organizations in countering corruption. Serby (Citation2015) calls for a new international treaty on match-fixing, encouraging cooperation between states, governing bodies, and regulators in countering fraud. Meier and Garcia (Citation2015) suggest that states and public authorities should coordinate their efforts and responses to reduce FIFA’s monopoly. Visschers, Paoli, and Deshpande (Citation2020) propose intensifying cooperation between law enforcement agencies, sports bodies, and fraud data sharing.

Discussion, implications, and conclusion

This paper provides a holistic understanding of fraud in professional football through a comprehensive framework that encompasses (i) the typologies and methods of perpetrating fraud in football, (ii) fraud risk factors in football, and (iii) how to counter football fraud. The findings show no evidence of external fraud reported in the literature. However, insider fraud, particularly corruption, is well documented in the literature. There is minimal evidence of other insider fraud types, such as asset misappropriation and financial fraud, and even fewer studies discussing fraud against football players and fans. This finding implies that these fraud types are not only under-studied but could also be under-reported. Therefore, future research should focus on empirically investigating these under-studied forms of fraud in professional football. Additionally, future studies should explore whether these fraud forms are under-reported and, if so, why.

While prior studies focused on a single fraud type, match-fixing, this paper shows that football fraud can take many other forms, including other forms of bribery, extortion, conflict of interest, favoritism, nepotism, asset misappropriation, and financial fraud. It also highlights that fraud can be committed against football fans and players. Therefore, this paper broadens our knowledge of the forms and methods of fraud in football. This finding also implies the need for professional and regulatory interventions to safeguard football organizations, fans and players against fraudulent activities that can tarnish the industry’s reputation. Highlighting the various forms and methods of fraud in football could help football leaders and policymakers design effective interventions such as implementing anti-fraud controls, raising fraud awareness, or imposing stricter penalties for committing fraud.

Moreover, the paper identifies various fraud risk factors in football, ranging from financial and sporting performance, competitive balance, and financial regulation issues to the lack of accountability, anti-fraud controls, governance mechanisms, and weak integrity culture in FIFA and football clubs. By so doing, it alerts policymakers and leaders to the high-risk areas that must be prioritized.

Overall, the paper argues that efforts to tackle fraud in football require financial, social, organizational, and regulatory change. Thus real change is unlikely to be achieved without the cooperation of other national and international actors, such as governments, football federations, and governing bodies. Therefore, it proposes an interdisciplinary, holistic framework for mitigating fraud risk focusing on enhancing accountability, promoting integrity, investing in anti-fraud controls and governance mechanisms, legislative reforms, using technology to detect fraud, and enhancing national and international cooperation. This proposed framework can be helpful to football clubs and organizations like FIFA seeking to enhance football integrity.

From a research perspective, this paper hopes to open up research debates on the fight against fraud. The proposed holistic approach needs to be tested, retested, and updated with the help of future research to tackle the complex and ever-changing fraud issue. More research is needed to explore the use of technology in countering football fraud and how to enhance international cooperation in the fight against football fraud, as they are still under-researched areas. Future studies could also critique what football is doing to tackle fraud or perhaps economic crime, which is much broader. Another idea for future research is to highlight the problem of economic crime in football through the lens of real-world cases.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the editor of Deviant Behavior, Dr Craig J Forsyth for his guidance and support throughout the review process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

No data available with this submission.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rasha Kassem

Rasha Kassem is an internationally oriented academic with thirteen years of experience in Higher Education. Rasha’s expertise is in Fraud, Risk Management, Governance, and Audit. Rasha is also a Certified Fraud Examiner, an academic advisor at Cifas, a member of the Cross-Sector Fraud Advisory Group at the Cabinet Office, and a member of the ACFE Fraud Advisory Council. Dr Kassem has authored numerous publications in Fraud, Audit, and Corporate Governance and has reviewed several manuscripts for a wide range of international peer-reviewed journals and book publishers.

Notes

1 FIFACodeofEthics_2023_EN01052023.pdf.

2 FraudAct2006(legislation.gov.uk).

References

- Acero, I., R. Serrano, and P. Dimitropoulos. 2017. “Ownership Structure and Financial Performance in European Football.” Corporate Governance 17(3):511–23. doi: 10.1108/CG-07-2016-0146.

- Albrecht, W. S., K. R. Howe, and M. B. Romney. 1984. Deterring Fraud: The Internal Auditor’s Perspective. Altamonte Springs, FL: Institute of Internal Auditors Research Foundation.

- Anagnostopoulos, C. and B. Senaux. 2011. “Transforming Top-Tier Football in Greece: The Case of the Super League.” Soccer and Society 12(6):722–36. doi: 10.1080/14660970.2011.609676.

- Andon, P. and C. Free. 2019. “Accounting and the Business of Sport: Past, Present and Future.” Accounting Auditing & Accountability Journal 32(7):1861–75. doi: 10.1108/AAAJ-08-2019-4126.