ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the activity of Japanese-language dark web sites by examining a Japanese dark web forum, the Onion Channel. While global crypto markets and English-language forums have been extensively studied, there has been little research on Japanese-language dark web sites. The number of posts and the variety of activities on the Onion Channel started increasing around mid-2012, exhibited steady growth until the end of 2016, and then showed a declining trend toward mid-2020. This study classifies activities on the forum into 10 categories. The forum was dominated by illegal and unethical activity. In particular, illegal drug dealing and cyberbullying were the two major illegal and unethical activities that took place there. The large presence of drug-related activity suggests that the forum on the dark web operated as a substitute for crypto markets. Textual analysis revealed that cannabis and methamphetamine were two major drugs that were likely to be sold, and those deals were likely to be completed face-to-face at a designated location. There was also a certain amount of illegal content, such as information related to fraud, identity theft and sales of false IDs, and hacking, as well as criminal conversations.

Introduction

The Worldwide Web (WWW) provides a platform for exchanging unprecedented amounts of digital information. The WWW consists of three different layers: the surface web, the deep web, and the dark web. The surface web can be indexed and searched through with popular search engines such as Google and Yahoo. In contrast, the deep web and dark web are unindexed and hidden from popular search engines (Stupples Citation2013). The most popular service on the dark web is the TOR network, which enables users to secretly share information anonymously via peer-to-peer connections instead of through centralized computer servers (Dingledine, Mathewson, and Syverson Citation2004). The virtual anonymity on the dark web lends itself to not only legitimate uses but also illegal or illicit activities (Al Nabki et al. Citation2017). The proportion of illegal activities on the Tor network is estimated to be between 25% (Al Nabki et al. Citation2017) and 57% (Weimann Citation2016).

Criminal activities on the dark web have taken place mainly in marketplaces known as crypto markets and forums. Crypto markets are online marketplace platforms where vendors list their goods and services for sale and buyers search for and compare products and vendors before purchase. Forums are online places where users mainly discuss and share information about viral topics as well as illegal activity. Since the first crypto market, the Silk Road, was launched in 2011 and its seizure by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in 2013, crypto markets have gained considerable attention from the media and law enforcement agencies, and numerous studies have been conducted on the subject (Décary‐Hétu et al. Citation2023). The most popular products for sale on crypto markets are illicit drugs (e.g., Soska and Christin Citation2015; Tzanetakis Citation2018). There is considerable evidence that tools and services for cybercrime and stolen data and information are all traded (Van Wegberg et al. Citation2018, Citation2020; Van Wegberg, Klievink, and Van Eeten Citation2017) as well as media containing child abuse (Dalins, Wilson, and Carman Citation2018) on crypto markets. Because direct dealing, a new type of drug dealing, between a vendor and buyer outside a crypto market has become increasingly commonplace through advertising on dark web forums (Childs et al. Citation2020), the attention to dark web forums has recently increased; thus, the investigation of dark web forums has provided insights into cyber threats.

Dark web forums are also often used for the anonymous trading of illicit items or services (Guitton Citation2013; Haasio, Harviainen, and Savolainen Citation2020) and for illicit or unethical discourse (Abbasi and Chen Citation2007; Weimann Citation2016). There are only a few studies that have investigated and classified the activity within each forum (Guitton Citation2013; Haasio, Harviainen, and Savolainen Citation2020), although there is a large body of literature categorizing various dark web sites or forums (Moore and Rid Citation2016; Nazah et al. Citation2020). On three dark web forums, unethical content was more common than ethical content in posts between June and July 2012 (Guitton Citation2013). Posts on a Finnish dark web forum between November 2017 and January 2018 were examined, and it was found that approximately 72% were related to drugs (Haasio, Harviainen, and Savolainen Citation2020). To capture the varying characteristics of dark web forums over time and how those forums have developed, it is necessary to analyze posts on those forums with longer observation periods. However, these previous studies focused only on a period ranging from one month to three months.

Therefore, this study attempts to fill this gap in the literature by providing a case study of the Onion Channel, a dark web forum in the Japanese language, and classifies its activities into 10 major categories. The Onion Channel was the first and most active Japanese dark web forum, operated between 2004 and 2021. The forum was operated even before the first successful crypto market and can be observed for a much longer period than those used in previous studies. Sites on the dark web vanish and disappear quickly (Nazah et al. Citation2020), and even Hydra, the dominant and probably longest-lived crypto market, was active for only seven years (Goonetilleke, Knorre, and Kuriksha Citation2023). This study covers all posts on the Onion Channel between its launch in 2004 and 2020, more than 15 years, making it a unique phenomenon that may reveal in study how a dark web forum develops its activity. Furthermore, previous studies have focused on Western countries. To complement literature on the Western world and draw insights, it is important to characterize this forum in terms of its similarity or differences to those of Western countries. Examining the existence of this long-running forum can contribute not only by filling a research gap regarding dark web sites in the Japanese language but also by shedding light on the activities of one of the earliest dark web sites and its evolution over time.

Overview of the onion channel

Before providing an overview of the Onion Channel, a brief overview of dark web sites and forums is provided. First, most of the dark web sites have been in English, and few are in Japanese. To our knowledge, no academic studies have focused on dark web forums in Japanese, although a few studies have detected dark web sites in Japanese. Dark web sites in Japanese are rare; six were found by crawling on June 29, 2019, and one was found by crawling in July 2020; meanwhile, 3268 sites were found in English in June 2019, while 8598 sites were found on July 14, 2020 (Arai, Yoshioka, and Matsumoto Citation2020). More than 85% of the dark web sites were in English, and the number of sites in Japanese was negligible (He, He, and Li Citation2019).

Dark web forums have been used by terrorist and extremist groups for illicit and unethical discourse (Abbasi and Chen Citation2007; Weimann Citation2016); cybercrime and discussions about crypto markets have also been commonly observed. A well-known example of the former is Darkode, which was launched in 2007 and taken down by an international law enforcement effort led by the FBI and European Police Office (EUROPOL) in (Citation2015). It was used not only as a means of information sharing but also as a venue for the sale and trade of hacking services, botnets, and malware and was considered the most prolific English-speaking cybercriminal forum (EUROPOL Citation2015). A well-known example of the forums on cybercrime and crypto markets is Dread, which was launched in 2018 and is still active; on Dread, users discuss information about crypto markets and market law enforcement activity (Popper Citation2019). Usually, on dark web forums, only registered members can read and post, while membership is anonymous and free (Guitton Citation2013).

A brief overview of the dark web in Japanese by focusing on the Onion Channel is provided. In sum, there are a small number of Japanese-language sites on the dark web, and the most common sites in Japanese are anonymous forums such as a well-known Japanese surface web forum, “5 channel”Footnote1 (Cheena Citation2019). Furthermore, illegal transactions often take place on these forums; however, there has been no establishment of crypto markets (Cheena Citation2019). Except for the Onion Channel, there are believed to be no other dark web sites that have been active for longer than a few years (Arai, Yoshioka, and Matsumoto Citation2020; Cheena Citation2019). Cheena (Citation2019) reported that there was a Japanese-language membership child pornography site, Magical Onion, in 2015, which subsequently shut down around the end of 2015 because users were successively caught, although there were no investigations in the literature.

Two years after the initial version of Tor was released to the public, the Onion Channel, the first Japanese site on the dark web, was established. It was an anonymous forum like 5 channel, combined with the anonymity of Tor. The administrators were unknown; there were three subforums: Tor, Pornography, and Underground. Unlike the other dark web forums investigated in the literature, no registration for membership was required to read or write posts on the Onion Channel. Therefore, anyone could start a new thread or post in any thread. A thread contained an opening message and the series of messages replying to it. shows an illustration of the Onion Channel. For ethical reasons, the contact information in the figure was hidden so that it could not be identified.

The Onion Channel likely effectively disappeared between July and October 2021. However, the reason for the closure was not clear; administrators did not leave any posts about the closure and there were no official or unofficial statements about the closure. There is also no information that the administrator was arrested or immigrated to a new site. The fact that there was a major update to the Tor network in October 2021 (Tor Citation2020) may be related to the closure because the administrators would have had to integrate the new version for the forum to keep operating. Unlike administrators of crypto markets, the administrators of the forums in Japanese did not profit from moderating those forums.

Methods

Data collection

Posts on the forum were collected between March 2, 2020, and June 3, 2020, using a custom web crawler built in Python that automatically collected all information of interest from the website. For each post on each thread, the raw data were then parsed using a dedicated parser to extract information on the title of the thread and the content of each post along with the date and username of the poster. The threads or posts were automatically archived, older threads were not deleted, or the threads and posts could not be deleted by any users. Administrators monitored the forum and removed threads with irrelevant posts. The removed threads were placed in the trash bin, and users could no longer post to them, although they could read the removed threads and their posts. These features ensure that once the data are collected, the collected data contain all threads and posts made from the time the forum was launched to the time of data collection (Sawicka, Rafanell, and Bancroft Citation2022). Therefore, a relatively short period of three months of data collection is likely to provide reliable and comprehensive data on posts.

We designed and implemented the scraping framework with a few simple goals (Soska and Christin Citation2015). First, our scraping was intended to be carried out in a stealthy manner. To avoid our requests being censored and by either modifying the content in an attempt to deceive us or denying the request altogether, it was not desirable to alert the administrators to our presence. Because scraping a site aggressively limits the stealth of the scraper, we manually imposed appropriate rate limits for the scraping: the crawler could not revisit the site within 1 second. The scraper was also designed to be capable of handling the client-side state normally kept by the users’ browser, such as cookies. These strategic scraper designs were likely to be robust enough to avoid detection schemes that might be devised to thwart the scraper.

Second, we aimed to make complete scrapes. These complete scrapes conveyed a coherent picture about what is taking place on the forum without doubts about possible unobserved actions because the forum was sometimes unstable and unable to be accessed during the scraping implementation times or during preliminary observations to identify site specifications. For completeness of data collection, the scrapes were attempted 44 times between the 93-day observation period, meaning that scrapes were completed once every other day on average. For each scrape, we collected all posts that had not been observed at the previous scrape. This indicates that our scraping likely achieved a high level of completeness in the data collection. Note also that all information regarding posts in the removed threads could be obtained from scraping even though they had been moved to the trash bin.

To avoid ethical challenges in the analysis of the data, URLs of other sites inserted in the messages were excluded from the downloaded materials (Moore and Rid Citation2016) because those URLs may provide access to illegal pictures and images. This was done as part of our ethical proofreading of the data. In ethical proofreading, researchers assume that informants can be identified from published research. Therefore, they seek to minimize any potential damage that could be done to the informants, even if the actual likelihood of their being identified is quite low (Lee Citation1993). We considered this especially important since, unlike in most other online environments, neither participant nor site owner consent could be obtained due to the anonymity principles the site follows (Ferguson Citation2017; Martin and Christin Citation2016). Furthermore, the site’s users were, in many cases, involved in criminal activities that carry severe judicial penalties. This very anonymity of message posters, however, enabled us to conform with the standard ethical guidelines established in the literature.

Classification

To identify each activity and the extent to which each is predominant, the collected posts were categorized according to the classification established by Dalins, Wilson, and Carman (Citation2018), who provided wider and more detailed categories based on prior studies (Broséus et al. Citation2017; Guitton Citation2013; Moore and Rid Citation2016). Dark web activities in the Japanese language had not previously been investigated and thus were not already known, so it was not possible to determine activity classifications in advance without relying on related literature. The two authors separately read the thread titles and the first few posts in the threads several times in preparation for the coding process. Therefore, a preliminary codebook was developed by inductively identifying the category of activities in each thread (Haasio, Harviainen, and Savolainen Citation2020). However, we detected high levels of cyberbullying activity, which was not covered by or did not fit the categories in previous studies. Three new categories, namely, cyberbullying, cyberstalking, and forum trolling, were created for coding under the classification of “cyberbullying.” This classification has its own category among various cybercrimes (Phillips et al. Citation2022). All the posts within a given thread were given the same category as that thread. In this work, it was assumed that the posts in a given thread were all related to the thread’s title, although there could have been posts within a given thread that differed from the thread’s classification. This assumption can be to some extent validated for the following two reasons. First, our manual examination of the first few posts in the threads provided supporting evidence of the assumption. Second, if a post was made that had nothing to do with the thread title, there would likely be no more posts to that thread. Thus, the overestimation of activity regarding posts in threads is unlikely to be substantial.

This coding process resulted in 45 categories. In this coding process, the intercoder reliability was checked by comparing the categorizations made by each author. Whenever differences in classification were found, they were discussed, and a decision regarding the classification of each thread was made together until the two manual coding sets were completely identical. This coding process also indicated that the coding was refined inductively and finalized in the process of checking intercoder reliability. Although the coding process was time-consuming, as 14,864 threads were coded, the coding of the total sample provided a comprehensive picture of the activity on the Onion Channel.

The 45 categories were subsequently grouped into 10 classifications modeled on and modified from previous studies. The 10 classifications are “chats and discussions,” “criminal communication,” “cyberbullying,” “drugs,” “fraud related,” “goods,” “hacking,” “ID related,” “other,” and “pornography.” The categories within each classification and their descriptions are shown in . Three remarks are necessary to clarify how our classifications differ from those of previous studies. First, “cyberbullying” was a newly introduced category. Second, “firearms and weapons,” which was one classification in previous studies, was classified under “goods” due to the very low occurrence of mentions of firearms and weapons. Third, “pornography” and “child pornography,” which were classified separately in previous studies, were grouped into one classification because there were not as many instances of pornography and child pornography; for the purpose of this paper, we aimed to obtain an overview of the activity. Finally, previous studies classified the activity of various dark web sites, not activity on a particular site or forum.

Table 1. Classification, category, and description of topics.

The coding process revealed that a significant number of categories are related to illegal or unethical activity. However, posts classified as “Chats and discussions” are unlikely to be related to illegal or unethical activity because chats or discussions on general issues, news, politics, or religion that bully or embarrass someone or organizations are categorized as one of the three “cyberbullying” categories. Posts classified as “Other” are also virtually unrelated to such illegal or unethical activity.

Topic model

To obtain more insights into the content of posts, this study further examines posts on Onion Channel using the latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) model (Blei et al. Citation2003). The LDA model identifies latent patterns of word occurrence using the distribution of words in a collection of documents. The LDA model assumes that each document is a mixture of a small number of topics and that each word’s creation is attributable to one of the document’s topics. The analysis consists of splitting each document into k topics. One can imagine that a poster on the Onion Channel writing about a topic will use a combination of words related to that topic. For example, a post about drug sales might be more likely to contain words such as “price,” “quantity,” or “cannabis,” whereas a post about a cyberbullying might be more likely to use words such as “insult,” “fool,” or “scum.” The LDA model optimizes the weighted word lists, that is, the topics, to discriminate between posts. For instance, the word “price” might be more closely related to the drug sales topic and therefore indicate that a post is on drug sales. The mixed-membership model represents each document as a set of shares of topics. For example, a post is classified as 75% drug sales and 25% cyberbullying if a particular drug sale with an insulting term is posted. This interpretability determines whether topic models in general and LDA in particular are useful for social science research since these approaches are among the most widely used machine learning techniques (Jacobi, Van Atteveldt, and Welbers Citation2018).

The LDA model requires researchers to specify the number of topics. To find the appropriate number of topics, we estimated models with a variety of presumed topic numbers varying from two through 100. These are then evaluated quantitatively and qualitatively by their ability to produce an acceptable amount of information loss and interpretability of the topics (Grimmer, Roberts, and Stewart Citation2022; Jacobi, Van Atteveldt, and Welbers Citation2018). The quantitative measure used is perplexity, where a lower perplexity indicates a better prediction (Blei et al. Citation2003). In our analysis, the collection of topics inferred by the LDA model would ideally resemble a classification that we manually assigned. However, topics are created by the LDA algorithm based on patterns of word co-occurrence in documents, which do not necessarily match those classifications. A topic could also represent writing styles or events, which are also formed through patterns of specific words (Jacobi, Van Atteveldt, and Welbers Citation2018).

To improve the performance of the LDA model, the raw text of posts is processed according to standard text-mining procedures (Grimmer, Roberts, and Stewart Citation2022). First, posts on the Onion Channel are reduced to bags of words from which the co-occurrence of words is analyzed. Second, we removed common words referred to as stop words such as “to” or “in.” Third, we used the lemmatizer and part-of-speech tagger MeCab (Kudo Citation2023). Fourth, we removed punctuation and all terms that contained a number or nonalphanumeric characters in Japanese. The LDA model was implemented using the widely used library Gensim.Footnote2

Results

Overview of the data

In total, there were 14,864 threads with 257,737 posts. These were posted between October 12, 2004, and June 3, 2020. These results indicate that there were approximately 2.6 threads and 45.1 posts per day. This study confirms that the Onion Channel has been in operation since 2004 (Cheena Citation2019). shows a histogram of the number of posts by thread with a line depicting the cumulative distribution. Approximately one-fourth of those threads had only one post, which was written by the thread starter. Aside from threads with only one post, threads with 10 to 29 posts were most common, and more than 90% of threads had fewer than 30 posts. Note that the maximum number of posts on a thread was 5,988, the average was 17.3, the median was 4, and the standard deviation was 100.6. These findings indicate that there were few threads that actually received many posts.

Classification of activity

The two leftmost columns of show what activity was observed on the forum based on the 10 classifications described above. Appendix shows information on the categories within each classification. Our data provide considerable evidence of illegal or unethical activity, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies. “chats and discussions,” “cyberbullying,” and “drug related” were the major activities because they accounted for more than 80% of both threads and posts. “drugs” accounted for approximately half of the threads. “cyberbullying” accounted for approximately one fourth of the threads, and “chats and discussions” accounted for approximately 10%. Additionally, each of these three major activities broadly accounted for more than one-quarter of all posts.

Table 2. Share of activity by threads and posts and comparisons to other studies.

There are two things worth mentioning regarding the difference in shares between threads and posts. First, the share of posts categorized as “chats and discussions” was greater than the share of threads for “chats and discussions,” indicating that the “chats and discussions” category was likely to have more posts than threads in other categories. In the classification of “chats and discussions,” chats in general had the largest share, and discussions on Tor had the second largest share, while the remaining categories had much smaller shares. This indicates that there are few political discourses in Japanese dark web forums, which is in line with the findings of Dalins, Wilson, and Carman (Citation2018) and Munksgaard and Demant (Citation2016). Second, in contrast to “chats and discussions,” the share of posts related to drugs was smaller than the share threads related to drugs because few posts were made in these threads. These results suggest that drug-related threads were used simply as information by vendors to promote the sale of their products; thus, subsequent posts were rarely followed up. In fact, drug sales accounted for the majority of posts in the “drugs” category, as shown in Appendix .

also shows the shares of activity on the forums and sites from the previous studies. The activities from the previous studies were classified to be as close as possible to our 10 classifications. Notably, the share of “chats and discussions” on dark web sites in our calculations is likely to be overestimated because “chats and discussions” may be classified as “others” in previous studies; those threads which could not be classified explicitly as illegal activities were classified as “chats and discussions” here. First, there are similarities among the forums and differences between the forums and the sites. A few major classifications were much larger than the remaining classifications on dark web forums, regardless of language. Although fraud-related activity was one of the major classifications, as was drug use on dark web sites, there were few fraud-related activities on forums. If fraud-related activity was classified as belong to other categories, such as hacking or ID-related crime, the number of activities classified as fraudulent was not large.

Second, comparisons with previous studies on forums provided more insights into “drugs” and “cyberbullying.” The prevalence of drugs is similar to that of the two forums, Das ist Deustchland in German and Sipulitori in Finnish, whereas the prevalence of drug-related activity is lower on two forums in English, the Onion Forum 2.0 and talk. The shares of drug-related activity on dark web sites, regardless of language, are not high – at most, approximately 15%. The highest prevalence of drug-related activity in the Finnish forum is attributed to the fact that Haasio, Harviainen, and Savolainen (Citation2020) investigated posts on discussion forums in Sipulitori, a Finnish crypto market that has focused mainly on drug trading. However, these findings indicate that there was also a prevalence of drugs on the German forum. Users who were interested in dealing with drugs in other languages were likely to use those forums because most crypto markets that focused on illicit drugs have operated in English (Soska and Christin Citation2015). These findings imply that the Onion Channel has served as a substitute for crypto markets in Japan. Although cyberbullying on forums, other than Sipulitori, was more prevalent than cyberbullying on dark web sites, the share of “cyberbullying” on the Onion Channel was much greater than that on the other four forums. This finding indicates that the Onion Channel played a major role in cyberbullying.

Activity over time

shows the time series of daily posts. A 30-day moving average was used to find overall trends and remove any possible seasonality in the data. The figure shows that the Onion Channel was not active until May 2012 because there were fewer than 10 posts on average before that point. After June 2012, the forum was more active, as indicated by the significant number of posts in June 2012. Afterward, the forum grew constantly until March 2017, with three spikes in July 2015, December 2015, and October – December 2016. From then on, the number of posts showed a declining trend, with an exceptional spike in August 2018, until June 2020. Overall, it can be concluded that there were three periods of forum activeness: an infancy period with fewer than 10 daily posts until May 2012, an active period with between 50 and 200 daily posts between June 2012 and March 2017, and a stagnant period with fewer than 50 daily posts since April 2018. The further declining trend since 2018 could be attributed to the instability of the Onion Channel because it was reported that the site was sometimes unavailable for viewing and posting between 2018 and 2019 (Cheena Citation2019).

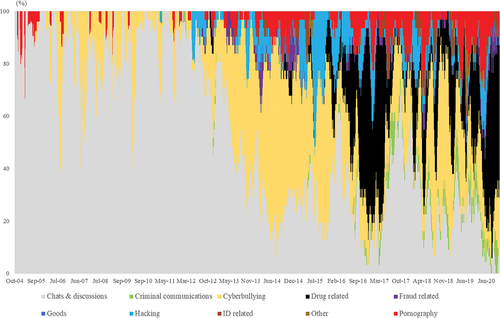

shows the share of each classification over time. Since mid-2012, when the number of posts started increasing steadily, the variety of illegal or unethical activities also increased. Note that the increase in activity and its variety came about one year after the launch of the most infamous dark web marketplace, the Silk Road, in February 2011 (Soska and Christin Citation2015). It is possible that as the Silk Road gained popularity and expanded in scale, illegal or unethical activity on the Onion Channel also became more common. Afterward, the share of each classification broadly remained stable, although there were temporary increases and decreases.

The activity on the forum started with licit or ethical activity via chats and discussions. Pornography was the earliest illegal activity on the forum, with general pornography being found since November 2004 and child pornography since August 2006. Cyberbullying, not including forum trolling, was the next illicit or unethical activity to emerge, beginning in January 2006. The earliest hacking-related activity was digital theft or piracy, which began in March 2011, and hacking information itself was founded in May 2012. Recruitment was the earliest criminal conversation found and emerged in February 2012. It was advertised that it was possible to hire an assassin on the site starting in April 2012, but it is not clear whether this was actually feasible. Commissioned and contracted assassins have been reported in various countries (Reporter Citation2013; Roddy and Holt Citation2022). In terms of drug-related activity, the drug sales started in September 2013, although the earliest activity that was neither sales nor purchases found in October 2012. The first drug sale was observed slightly earlier than the emergence of direct dealing following the closure of the Silk Road in October 2013 and has since evolved to complement the crypto market supply (Barratt et al. Citation2016). Identity-related activity started in March 2013. For fraud-related activity, money laundering was the earliest and emerged in June 2012.

The temporary increase in a few particular classifications likely corresponded with the rapid increase in the number of posts shown in . Chats on Tor use increased sharply in June 2012, contributing to a spike in the number of posts. In July 2015, a sharp increase in the “chats and discussion” and “hacking” categories was the main contributor to a spike in overall posts, while a spike in posts in December 2015 was attributable to a sharp increase in “drugs” and “hacking” activity. The sharp increases in the number of posts between October and December 2016 were mainly associated with “hacking” in October, “cyberbullying” in November, and “drugs” activity in December. In August 2018, the increase in “drug-related” activity was the major contributor to the overall increase. Note, however, that those spikes were likely not triggered by specific incidents or events that were broadcasted or reported in the media. These findings were likely unexpected, indicating that it is difficult to predict what causes growth and decline in posts and how forum activity will vary. Note also that those rapid spikes in posts included posts that were unrelated to the thread title, and thus, the size of each classification might be overestimated. During the rapid increases in the posts in the threads in a particular classification, there were also increases in posts in threads by spectators who tried to redirect or urge them to stop those posts. This was particularly common in August 2018.

Text analysis

We settled on the model with three topics. To specify the number of topics, we initially selected models with three to five topics because they have the lowest values of perplexity. The perplexity increases monotonically and rapidly both above five topics and below three topics. This study selects three for the number of topics after reviewing exemplar documents that contain high shares of the identified topics because of their interpretability. As the number of topics increased from three, we found that the models reflected the same thematic structure differing only in granularity or level of detail. Preprocessing yielded a total vocabulary of 66,186 terms in 219,012 documents out of all 257,737 collected posts.

shows topics that resulted from the LDA model, including the 10 words with the highest probability of appearing in that topic. To facilitate interpretations and label topics, documents with the highest share of a particular category under consideration were examined. Topic 1 included terms related to cyberbullying, “vendor,” “Japan,” “site,” “choose,” “support,” “today,” “deny,” “be,” “member,” and “template,” as the 10 most common terms. These terms were used to identify and attack the people they are insulting, while claiming that they are the chosen sensible ones. The words “vendor,” “Japan,” “site,” “member,” and “template” are often used to abuse drug vendors, members of some political and religious groups, open public websites, and reposts, respectively. Conversely, “choose” suggests a claim that they are chosen sensible ones. “support” is often used in the context that it is required to support organizations that attack opposing people and groups. Two symbolic terms, which are described using Japanese characters, are also used to describe cyberbullying. The term “deny” is a type of emoji used to express denial (Okumura Citation2016) and is used to indicate bullying. The term “be” represents the pronunciation of the Korean verb “be” in Japanese (Yoon Citation2009) and is used in abusive descriptions of Korea.

Table 3. LDA results: most representative words.

Topic 2 and Topic 3 are related to drug dealing. Topic 2 indicates drug dealing. The terms “deliver,” “phone,” “inquire,” and “email” are related to delivery, inquiry, and contact methods for drug dealing, respectively. The terms “sale” and “service” suggest drugs for sale and volume service, respectively, for first-time buyers. The term “confirm” suggests that drug quality can be confirmed at purchase. “Vegetable” and “ice” are slang for cannabis and methamphetamine, while “hand-push” is slang for face-to-face deals at a designated location (Police of Kyoto, Citation2022). Topic 3 is also related to drug dealing, particularly with relation to location. The names “Tokyo,” “Osaka,” “Saitama,” “Chiba,” and “Kanagawa” are prefecture names. Kanto and metropolitan areas also indicate areas; that is, the former indicates a wider area that includes Tokyo and six neighboring prefectures, and the latter indicates a district that consists of 23 special wards in the eastern part of Tokyo. The term “prefer” is also used with locations in the context of delivery to a buyer’s preferred location within a given prefecture. The term “female” is often used in the context of “orders from females are welcome.” “Scam” is usually used to warn buyers of scam dealers.

These findings from the LDA model support the results in the previous sections that cyberbullying and drug dealing were the two major activities and further provided insights into each activity. Not only members of political or religious groups but also drug vendors and some forum users were cyberbullied. An overview of drugs mentioned for trade on the Onion Channel was also provided. First, due to the illegal nature of the trade, direct expressions of illegal drugs are unlikely to be used. Cannabis and methamphetamine are the two major drugs most likely to be mentioned, which is consistent with the fact that these are the most commonly used drugs in Japan, and more than 90% of arrests are related to them (Ministry of Justice Citation2021). Second, face-to-face delivery to specific rendezvous points rather than postal delivery was the delivery method most likely to be suggested. The Tokyo Metropolitan area and Osaka, the largest city in the western part of Japan, that is, the two most populated areas, seem to have the most drug dealing. Other activities, including illegal activities related to the purchase and sales of goods, hacking, and ID-related theft, might be masked with terms related to drug dealing because of similarities in the language and written style for talking about those other activities.

Discussion and limitations

This section discusses whether there were any differences in the forum in Japanese from forums in other languages, whether there have been any impacts of COVID-19 on forum activities, and the limitations of this study.

There are three features of the Onion Channel worth mentioning. First, there were a relatively larger share of threads regarding the sale of drugs on the Onion Channel than on forums in other languages (Guitton Citation2013). This finding suggests that the forums on the dark web worked as a substitute for crypto markets because crypto markets in Japanese have not yet been observed. Second, compared to forums in other languages, on the Onion channel, there was relatively little activity involving child pornography (Guitton Citation2013). This was likely because there are dark web sites that specialize in child pornography. The Onion Channel likely served as a gateway to those sites. In fact, there were already at least two large Japanese-language membership child pornography sites on the dark web: “Magical Onion” and “Lolitter 2” (Cheena Citation2019). The former was shut down at the end of 2015 after seven users were successively caught in September and November 2015. The latter was launched in February 2017, and its founder was arrested in June 2018. Third, text analysis revealed that drug dealing on the Onion Channel was more similar to drug dealing on social media than dealing on crypto markets. In those crypto markets, postal delivery rather than face-to-face delivery was the preferred delivery method (Barratt et al. Citation2022). In contrast, on social media, sellers and buyers meet face-to-face to exchange drugs for cash or receive home drops offs after contact, indicating that drug markets are locally segregated and that postal delivery is rare (Bakken and Demant Citation2019).

Regarding the impacts of COVID-19, there were unlikely to be apparent changes in the volume of daily posts after January 2020 when the pandemic started expanding globally. There was also no significant impact on the volume of daily posts after April 2020 when the first state of emergency was declared by the government in Japan. In terms of activity on the forum posts, activity related to drugs increased after January 2020, and it continued to be prevalent until the end of the observation period. In February 2020, there were 26 posts about face masks. The increase in posts about drugs can be partly attributed to increased anxiety triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic and vendors who were attempting to exploit the heightened anxiety and increase possible demand. Although the extent of and change in drug use and addiction varies with the time period, country and governmental policies, marijuana use has increased across generations (Brenneke et al. Citation2022), and the pandemic fueled drug addiction (Dubey et al. Citation2020).

Finally, the limitations of this study must be noted. First, there might be missing data due to issues related to the site’s administrators. They might have deleted threads and posts completely from the trash bin so that we could not view or obtain them. Second, it was not possible to examine the posts for approximately one year before the site was closed. Therefore, it is not clear if the observed patterns of activity still held at the end of the observation period. In addition, for future research, more elaborate investigations of major illicit activities such as illegal drug trading and cyberbullying should be performed. Text analysis with more elaborate and advanced techniques can be applied to further reveal the characteristics of various activities. Additionally, other dark web forums in Japanese and more recent activities on those forums should be investigated in future research.

Conclusion

This study investigated the Onion Channel, a dark web forum in the Japanese language to fill a research gap regarding dark web sites in the Japanese language and shed light on the activities of one of the earliest dark web sites. This study collected posts from the forum between March 2, 2020, and June 3, 2020, using a custom web crawler. The posts were then categorized into 10 major activity classifications. The study found that a significant number of categories were related to illegal or unethical activities, with “chats and discussions,” “cyberbullying,” and “drugs” being the major activities and topics on the forum. The data showed evidence of drug sales activity, suggesting that the forum served as a substitute for crypto markets, and also revealed how drug dealing took place. The study analyzed the activity over time and identified three periods by the amount of activity on the forum: an infancy period with few posts, an active period with increased posts, and a stagnant period with few posts. The variety of illegal or unethical activities increased as the number of posts grew, and this study traced the emergence of different categories of activity over time. The findings highlight the prevalence of illegal or unethical activities on the forum and the evolving nature of dark web activities over time.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the helpful suggestions from two anonymous referees. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Mercari/Mercoin Inc.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Naoki Hiramoto

Naoki Hiramoto is a researcher at Mercari/Mercoin, IT company in Tokyo, Japan. His research interest is statistics, applied mathematics and their applications to cyber crime research.

Yoichi Tsuchiya

Yoichi Tsuchiya is a Professor at the School of Commerce, Meiji University, in Tokyo, Japan. He received his Ph.D. in Economics from State University of New York at Buffalo. His research interests are activity on darkweb and economic forecasting.

Notes

1 It was established in May 1999 and was formerly called “2 channel.” It has become the largest open forum in Japan (https://5ch.net/).

2 See https://radimrehurek.com/gensim/for details. To calculate perplexity, this study set a hyperparameter at a default value of one.

References

- Abbasi, Ahmed and Hsinchun Chen. 2007. “Affect Intensity Analysis of Dark Web Forums.” Pp. 282–88 in 2007 IEEE Intelligence and Security Informatics, New Brunswick, NJ, USA, IEEE.

- Al Nabki, Mhd Wesam, Eduardo Fidalgo, Enrique Alegre, and Ivan De Paz. 2017. “Classifying Illegal Activities on Tor Network Based on Web Textual Contents.” Pp. 35–43 in Proceedings of the 15th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Valencia, Spain, Volume 1, Long Papers.

- Arai, Yu, Katsunari Yoshioka, and Tsutomu Matsumoto. 2020. “A Study on the Chronological Change of Darkweb.” Pp. 44–49 (in Japanese) in Computer Security Symposium 2020, Kobe, Japan.

- Bakken, Silje Anderdal and Jakob Johan Demant. 2019. “Sellers’ Risk Perceptions in Public and Private Social Media Drug Markets.” International Journal of Drug Policy 73:255–62.

- Barratt, Monica J., Francois R. Lamy, Liam Engel, Emma Davies, Cheneal Puljevic, Jason A. Ferris, and Adam R. Winstock. 2022. “Exploring Televend, an Innovative Combination of Cryptomarket and Messaging App Technologies for Trading Prohibited Drugs.” Drug & Alcohol Dependence 231:109243.

- Barratt, Monica J, Simon Lenton, Alexia Maddox, and Matthew Allen. 2016. “‘What if You Live on Top of a Bakery and You Like cakes?’—Drug Use and Harm Trajectories Before, During and After the Emergence of Silk Road.” International Journal of Drug Policy 35:50–57.

- Blei, David M, Andrew Y Ng, and Michael I Jordan. 2003. “Latent dirichlet allocation.” Journal of Machine Learning Research 3(Jan):993–1022.

- Brenneke, Savannah G, Courtney D. Nordeck, Kira E. Riehm, Ian Schmid, Kayla N. Tormohlen, Emily J. Smail, Renee M. Johnson, Luther G. Kalb, Elizabeth A. Stuart, and Johannes Thrul. 2022. “Trends in Cannabis Use Among US Adults Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic.” International Journal of Drug Policy 100:103517.

- Broséus, Julian, Marie Morelato, Mark Tahtouh, and Claude Roux. 2017. “Forensic Drug Intelligence and the Rise of Cryptomarkets. Part I: Studying the Australian Virtual Market.” Forensic Science International 279:288–301.

- Cheena. 2019. Textbook of Darkweb. Tokyo (in Japanese): Data House Inc.

- Childs, Andrew, Ross Coomber, Melissa Bull, and Monica J. Barratt. 2020. “Evolving and Diversifying Selling Practices on Drug Cryptomarkets: An Exploration of Off-Platform “Direct Dealing.” Journal of Drug Issues 50(2):173–90.

- Dalins, Janis, Campbell Wilson, and Mark Carman. 2018. “Criminal Motivation on the Dark Web: A Categorisation Model for Law Enforcement.” Digital Investigation 24:62–71.

- Décary‐Hétu, David, Camille Faubert, Julien Chopin, Aili Malm, Jerry Ratcliffe, and Benoît Dupont. 2023. ““Like Aspirin for arthritis”: A Qualitative Study of Conditional Cyber‐Deterrence Associated with Police Crackdowns on the Dark Web.” Criminology & Public Policy 22(4):639–64.

- Dingledine, Roger, Nick Mathewson, and Paul Syverson. 2004. Tor: The Second-Generation Onion Router. Washington DC: Naval Research Lab.

- Dubey, Mahua Jana, Ritwik Ghosh, Subham Chatterjee, Payel Biswas, Subhankar Chatterjee, and Souvik Dubey. 2020. “COVID-19 and Addiction.” Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 14(5):817–23.

- EUROPOL. 2015. “Cybercriminal Darkode Forum Taken Down Through Global Action.” Retrieved July 15, 2015 (https://www.europol.europa.eu/media-press/newsroom/news/cybercriminal-darkode-forum-taken-down-through-global-action).

- Ferguson, Rachael-Heath. 2017. “Offline ‘Stranger’and Online Lurker: Methods for an Ethnography of Illicit Transactions on the Darknet.” Qualitative Research 17(6):683–98.

- Goonetilleke, Priyanka, Alex Knorre, and Artem Kuriksha. 2023. “Hydra: Lessons from the World’s Largest Darknet Market.” Criminology & Public Policy 22(4):735–77.

- Grimmer, Justin, Margaret E. Roberts, and Brandon M. Stewart. 2022. Text as Data: A New Framework for Machine Learning and the Social Sciences. Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton University Press.

- Guitton, Clement. 2013. “A Review of the Available Content on Tor Hidden Services: The Case Against Further Development.” Computers in Human Behavior 29(6):2805–15.

- Haasio, Ari, J. Harviainen, and Reijo Savolainen. 2020. “Information Needs of Drug Users on a Local Dark Web Marketplace.” Information Processing & Management 57(2):102080.

- He, Siyu, Yongzhong He, and Mingzhe Li. 2019. “Classification of Illegal Activities on the Dark Web.” Pp. 73–78 in Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Information Science and Systems, Tokyo, Japan.

- Jacobi, Carina, Wouter Van Atteveldt, and Kasper Welbers. 2018. “Quantitative Analysis of Large Amounts of Journalistic Texts Using Topic Modelling.” Pp. 89–106 in Rethinking Research Methods in an Age of Digital Journalism, edited by K. Michael, S. Helle. London, UK: Routledge.

- Kudo, Taku. 2023. MeCab: Yet Another Part-Of-Speech and Morphological Analyzer. (in Japanese). 2023.

- Lee, Raymond M. 1993. Doing Research on Sensitive Topics. London, UK: Sage.

- Martin, James and Nicolas Christin. 2016. “Ethics in Cryptomarket Research.” International Journal of Drug Policy 35:84–91.

- Ministry of Justice. 2021. White Paper on Crime 2021. Tokyo: Research and Training Institute.

- Moore, Daniel and Thomas Rid. 2016. “Cryptopolitik and the Darknet.” Survival 58(1):7–38.

- Munksgaard, Rasmus and Jakob Demant. 2016. “Mixing Politics and Crime–The Prevalence and Decline of Political Discourse on the Cryptomarket.” International Journal of Drug Policy 35:77–83.

- Nazah, Saiba, Shamsul Huda, Jemal Abawajy, and Mohammad Mehedi Hassan. 2020. “Evolution of Dark Web Threat Analysis and Detection: A Systematic Approach.” Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Access 8:171796–819.

- Okumura, Noriyuki. 2016. “A Large Scale Dictionary of Kaomoji for Natural Language Processing.” The 30th Annual Conference of the Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence, Kitakyushu, Japan, The Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence.

- Phillips, Kirsty, Julia C. Davidson, Ruby R. Farr, Christine Burkhardt, Stefano Caneppele, and Mary P. Aiken. 2022. “Conceptualizing Cybercrime: Definitions, Typologies and Taxonomies.” Forensic Sciences 2(2):379–98.

- Police of Kyoto. 2022. “Dictionary of Illegal Drug Cryptography (In Japanese).” Retrieved November 15, 2023 (https://www.pref.kyoto.jp/fukei/anzen/sotaisan/yakuran/index.html).

- Popper, Nathaniel. 2019. “Dark Web Drug Sellers Dodge Police Crackdowns.” Retrieved June 11, 2019 The New York Times.

- Reporter, Daily Mail. 2013. “The Disturbing World of the Deep Web Where Contract Killers and Drug Dealers Ply Their Trade on the Internet.” Mail Online 11(10). 2013. 11 October, 2013.

- Roddy, Ariel L. and Thomas J. Holt. 2022. “An Assessment of Hitmen and Contracted Violence Providers Operating Online.” Deviant Behavior 43(2):139–51.

- Sawicka, Maja, Irene Rafanell, and Angus Bancroft. 2022. “Digital Localisation in an Illicit Market Space: Interactional Creation of a Psychedelic Assemblage in a Darknet Community of Exchange.” International Journal of Drug Policy 100:103514.

- Soska, Kyle and Nicolas Christin. 2015. “Measuring the Longitudinal Evolution of the Online Anonymous Marketplace Ecosystem.” Pp. 33–48 in 24th USENIX Security Scymposium (USENIX Security 15), Washington, DC, USA.

- Stupples, David. 2013. “ICITST-2013: Keynote Speaker 2: Security Challenge of TOR and the Deep Web.” Pp. 14–14 in 8th International Conference for Internet Technology and Secured Transactions (ICITST-2013), London, UK, IEEE.

- Tor. 2020. “V2 Onion Services Deprecation.” https://support.torproject.org/onionservices/v2-deprecation/index.html.

- Tzanetakis, Meropi. 2018. “Comparing Cryptomarkets for Drugs. A Characterisation of Sellers and Buyers Over Time.” International Journal of Drug Policy 56:176–86.

- Van Wegberg, R. S., A. J. Klievink, and M. J. G. Van Eeten. 2017. “Discerning Novel Value Chains in Financial Malware: On the Economic Incentives and Criminal Business Models in Financial Malware Schemes.” European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 23:575–94.

- Van Wegberg, Rolf, Fieke Miedema, Ugur Akyazi, Arman Noroozian, Bram Klievink, and Michel van Eeten. 2020. “Go See a Specialist? Predicting Cybercrime Sales on Online Anonymous Markets from Vendor and Product Characteristics.” Pp. 816–26 in Proceedings of the web conference 2020, Taipei Taiwan.

- Van Wegberg, Rolf, Samaneh Tajalizadehkhoob, Kyle Soska, Ugur Akyazi, Carlos Hernandez Ganan, Bram Klievink, Nicolas Christin, and Michel Van Eeten. 2018. “Plug and Prey? Measuring the Commoditization of Cybercrime via Online Anonymous Markets.” Pp. 1009–26 in 27th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 18), Baltimore, MD, USA.

- Weimann, Gabriel. 2016. “Going Dark: Terrorism on the Dark Web.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 39(3):195–206.

- Yoon, Changhoon. 2009. Sanseido’s Daily Concise Korean Dictionary. Tokyo: Sanseido.

Appendix

Table A1. Descriptive statistics and information for each category.