ABSTRACT

This study employed an observational design to explore the presentation of advocacy strategies in YouTube videos orientated around the event of Self-Injury Awareness Day (SIAD). While previous research has focused on highlighting potential dangers of social media platforms like YouTube we approached our exploration from a perspective of advocacy to try and establish a more balanced understanding of how YouTube can, and does, contribute to self-injury discourses. The aim was not to define advocacy in YouTube videos but rather to understand more about the ways advocacy strategies might be presented, and what this looks like in the content produced by individuals with lived experience of self-injury. We expected to find content concerned with improving the lives of people experiencing self-injury, which could be interpreted as advocacy. Thematic analysis of thirty videos offered four themes: Community, comradery, and cheerleading; Education around self-injury; Authentic representation of self-injury; Development of advocacy identity. Findings indicate advocacy through YouTube exists and results in supportive, passionate, and resourceful content with potential to improve the wellbeing of individuals who self-injure, countering narratives of self-injury related content having a solely negative impact. Further research is required to fully understand, and harness, the potential of advocacy through online mediums.

Introduction

YouTube is a global social media platform on which individuals can publish visual content to share with other viewers. Launched in 2005, it is considered one of the largest and most well-known social media platforms with billions of world-wide viewers daily (Kilinç Citation2022). In 2023 YouTube boasted twice the number of viewers as rivals TikTok and Instagram, and was the second-largest search engine after Google. Simultaneously a technology, social practice, and cultural form (Van Dijck Citation2013) it has the potential to facilitate insights into individuals “lives, relationships, and habits” (Savage and Woloshyn Citation2022). Increasingly, YouTube is being recognized as a popular source of health-related information (Kilinç Citation2022; Osman et al. Citation2022). When it comes to mental health and wellbeing YouTube offers vital dissemination of information (Alhassan and Rasmussen Pennington Citation2022) and provides increased opportunity for communities with shared mental health experiences to present their stories to each other, and to audiences beyond, creating a community space for peer support, shared learning, and increased socialization (Betton and Tomlinson Citation2013). From such activities social media has been identified as a “crucial tool” for advocacy (Schermuly et al. Citation2021). This article will begin by exploring definitions of online advocacy and the current literature surrounding YouTube and self-injury content. It will then present the research methods utilized and the research findings before closing with a discussion of said findings, and an exploration of potential implications and future research directions.

Advocacy

Smith-Frigerio (Citation2020) suggests that the use of digital tools, such as YouTube, for online advocating is an extension of “grassroots advocacy.” Grassroots advocacy describes actions by non-government directed stakeholders capable of affecting powerful change in awareness, treatment, and policy. She highlights the importance of further studying how such grassroots movements craft their messages, how these messages are received, and how advocacy strategies to address mental health concerns are integrated.

The challenge of exploring this however, is that there is no current universally agreed meaning for the construct of advocacy in healthcare (Smith-Frigerio Citation2020). Drawing on the work of Zoller (Citation2005), Smith-Frigerio offers a general distinction that health advocacy focuses on messaging, which continues existing systems of healthcare – such as the biomedical model – and emphasizes education, while health activism challenges existing order and subverts existing power structures. To summarize, advocacy holds the more moderate associations of working alongside those in authority for the good of the community, while activism indicates radical change working against established authority. The former, Schermuly et al. (Citation2021) argue, is indicative of “responsibilisation” as personal practices are emphasized in response to healthcare needs unmet by the state. An example of this can be seen in YouTube video blogs by veterans (Schuman et al. Citation2019) who utilisied advocacy strategies to take on the responsibility of bridging service gaps in outreach, education, and support in the veteran community. Firmin et al. (Citation2017) identify advocacy as a core element to the public level of their conceptual model of stigma resistance. Advocacy work in this model was described as giving back to the community but also creating change regarding attitudes toward mental health. Both advocacy and activist strategies were identifiable in the activities listed by Firmin et al. (Citation2017) of this in action, including: peer support work, sharing personal stories, speaking out about political reform, and hosting educational events.

It seems that recognizing distinctions between the terms of advocacy and activism may be useful when considering the deeper consequences for individuals implied by traditional interpretations (e.g., “responsibilisation”); however, when in action, advocacy and activism are interrelated, overlapping, and entangled. This means it might be best to consider them as a single spectrum of potential messaging strategies in which elements of both education and systemic challenge are present (Laverack Citation2013). Raun (Citation2018) offers “activism/advocacy” as a way to acknowledge this entanglement In the present paper, however, we simply use “advocacy” as an integrated term representing elements of both. Accepting this breadth of conceptualization allows an exploratory position from which it is acknowledged that the academic definitions of advocacy may not align with how it is being deployed in a digital context. In fact, individuals on YouTube performing advocacy-type actions may not even consider themselves to be “advocates,” something which will be explored in the course of the present research. Indeed, the terminologies and associated definitions used in academic and clinical settings may not necessarily align with those used by individuals with lived experience of NSSI (Hasking, Boyes, and Lewis Citation2021; Lewis and Hasking Citation2023; Pritchard et al. Citation2021).

YouTube

The form YouTube videos take can vary widely. One form commonly associated with YouTube is video blogging (vlogging). This involves the creation of short videos in which individuals speak directly to an audience, sometimes with accompanying text or images, to express thoughts, ideas, or experiences around a particular subject. Advocacy work has previously been identified in veteran vlogging (Schuman et al. Citation2019) and transgender vlogging (Raun Citation2018), with individuals using personal stories to foster support and awareness for their associated communities. Other forms of video include filmed discussions/dialogs, and mixed-media compilations which utilize voiceovers, music, and text (Woloshyn and Savage Citation2020). Misoch (Citation2014) also identifies the category of “card stories.” Here, handwritten or typed notecards are presented sequentially to communicate information, accompanied by music to accentuate the message.

While YouTube remains generally understudied (Allgaier Citation2020), the platform has been the site of several studies on self-injury (Lewis et al. Citation2011; Lewis et al. Citation2012; Ryan-Vig et al. Citation2019). Social media generally has been highlighted as a particularly useful way to access otherwise difficult to research communities (Rodham and Gavin Citation2006), including among people who self-injure (for a review see Lewis and Seko ,Citation2015). Alhassan and Rasmussen Pennington (Citation2022) identify six categories of classification for creators of videos concerning self-injury – professionals, nonprofessionals, news media, Government organizations, private organizations, and support organizations. Nonprofessionals were identified as “layperson[s] who promote mental health awareness, with the video presenter being a non-academic or non-medical expert” (2022:5) and made up more than half of the videos they sampled. The focus of the present study was therefore on people who independently produce and publish content rather than those who have been supported or recruited by an established group (e.g., a charity) to tell their story (Caron et al. Citation2017). Not only were such videos identified as most favored by viewers (Alhassan and Rasmussen Pennington Citation2022) but focusing on content produced by nonprofessionals allows access to voices which are not interpreted or mediated by another party (Sangeorzan et al. Citation2019) and aligns with the definition of grassroots advocacy outlined previously.

When it comes to researching mental health and self-injury through digital spaces such as YouTube, Lavis and Winter (Citation2020) explain there is opportunity to reassess content previously considered harmful, or of causing self-harm, to gain a deeper understanding of the wider contexts influencing both self-harm and social media use. Such opportunity is limited in research, which focuses on potential dangers like “contagion” (Khasawneh et al. Citation2020), “problematic representation” (Dobson Citation2016), and “the dark side” (Hattingh Citation2022) – terminologies themselves which do little to counter the stigma so frequently experienced by individuals who self-injure, stigma which can itself increase the appeal of social media as a source of support (Lavis and Winter Citation2020). Existing research around online advocacy-type activity for self-injury has tended to focus on non-video platforms such as chat rooms and support fora (e.g. Adler and Adler Citation2008; Eysenbach et al. Citation2004); however, these spaces tend to be specialist in nature, curated specifically for individuals with experience of self-injury and/or their families/loved ones. Such sites must be actively sought out, whereas YouTube is a popular public forum that is freely accessible to an entertainment seeking audience that expands beyond the self-injury community; a fact which is of direct concern to YouTube, illustrated through their specific self-injury and suicide policy (Google Citation2022) to reduce liability around such content. If creators on YouTube are replicating the advocacy seen on other, more discrete, platforms this could indicate an expansion of advocacy practices which is useful to explore. There is also insight to be gleaned regarding how the video format is being engaged to broadcast advocacy messaging. With prior research pointing to the salience and potential impact of YouTube videos concerning self-injury for people with lived experience of self-injury (e.g., Lewis et al. Citation2011, Citation2012; Lewis and Knoll, Citation2015), knowing more about advocacy-type videos is important.

Overall, as YouTube is “a ripe, diverse, and almost endlessly extensive database” (Patterson Citation2018:759) it is essential to explore the platform from alternative perspectives, such as the lens of advocacy presented in this research, in order to establish a balanced understanding of how YouTube can and does contribute to self-injury discourse. Indeed, from their research around the impact of web-based sharing/viewing of self-injury related videos, Marchant et al. (Citation2021) acknowledge the potential for positive impacts and call for research which explores this possibility further. The aim in this research then is not to attempt to define advocacy in YouTube videos but to understand more about the ways in which advocacy strategies might be presented by people with lived experience of self-injury and what this looks like. We anticipated finding a range of content concerned with improving the lives of those experiencing self-injury which could be interpreted as advocacy. The research questions are as follows:

Are there videos on YouTube by people with lived experience of self-injury which deploy advocacy strategies?

How are advocacy strategies presented in YouTube content created by people with lived experience of self-injury?

Methodology

Drawing from existing research exploring mental health topics on YouTube (Lewis et al. Citation2011; Ryan-Vig et al. Citation2019; Woloshyn and Savage Citation2020) this study employed an observational design in which thematic analysis was applied to transcriptions of YouTube videos with content related to self-injury advocacy.

Research design

In designing their YouTube search for advocacy videos Caron et al. (Citation2017) advise that relevant results can be achieved by searching for “event-oriented content.” This means searching around a specific event or prompt which is associated with the expression of advocacy. Our research is therefore orientated around Self-Injury Awareness Day (SIAD), an internationally recognized event for people with experience of self-injury and their loved ones, held on March 1st. While the precise meaning and purpose of the day likely varies across stakeholders, a core aim of SIAD is to “raise awareness” about self-injury, which aligns with advocacy. The date of SIAD, and the weeks immediately preceding and following it, are marked by established organizations and individuals holding gatherings, wearing orange awareness ribbons, posting blogs, and sharing social media posts. Content titled or tagged under SIAD therefore ostensibly indicate that advocacy strategies will be deployed in the pursuit of raising awareness, offering a practical way to narrow down the selection of videos for this research.

Search terms (i.e., self-injury awareness day; self-harm awareness day; self-harm awareness month; self-injury awareness month; #SIAD) were individually entered via the YouTube search function. These terms were intentionally broad in relation to SIAD and selected to capture videos which might have been uploaded in association with SIAD, while accounting for common interchangeable terms. Although the YouTube search engine is not considered the most efficient in organizing content (Caron et al. Citation2017) it was deemed sufficient for the purposes of this study due to the use of “simple” search terms (keywords and phrases only); moreover, users seeking SIAD related content may use similar terms in their search. Searches were carried out during a single session in August 2021 on a private web browser with cleared cookies and search history; similar approaches have been used in YouTube data focused research (e.g., Lewis et al. Citation2011; Bandyopadhyay and Singh Citation2022) to limit any influence on search results from the researchers existing viewing practices. The search was carried out in the UK, which may have influenced the results generated as YouTube uses location information to serve videos specific to the viewers local region.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) video is from a commercial channel with content from established professionals, organizations, charities, or companies versus an individual with lived experience; 2) video is an unedited media excerpt from a television show/film; 3) video has restricted access requiring a YouTube account to view (i.e., not in the public domain); 4) video content was not in English, preventing accurate transcription; 5) video was uploaded less than 6 months from the time of the data search and could thus be ethically challenging as any problematic disclosures would not be historical (Ryan-Vig et al. Citation2019); 6) video contains irrelevant content (i.e., not on self-injury); 7) secondhand account (e.g. family, friend) as the person discussed in the video may not have consented to the video being shared online (Legewie and Nassauer Citation2018).

After each search term was entered, video results were filtered by view count, from most to least, as a way to identify those with the highest potential impact through visibility. As thousands of results were retrieved and to make the data manageable for our study purpose, only videos from the first three pages of each search identified as eligible had their URL, video length, view count, and date of upload collected and stored. Videos were revisited within one week of the initial search for transcription during which time two videos became inaccessible, precluding transcription and analysis.

Overall, 258 total videos were retrieved from the search process, 79 of which were excluded as duplicates. The remaining 179 videos were screened according to the criteria outlined earlier, leaving 111 eligible videos – after attrition – for consideration (). As observed by Holmes (Citation2017):30–35 videos is an appropriate sample size when working with YouTube data as video formulas and content begin to repeat around this number, with only minor variations to be observed beyond this. Research also suggests the majority of online users do not explore beyond the first three search result pages (Morahan-Martin Citation2004). For this reason the 30 most viewed of the 111 eligible videos were selected for analysis. This decision is in line with comparable studies utilizing YouTube as a data source (Lewis et al. Citation2011, Citation2012; Ryan-Vig et al. Citation2019; Sokół Citation2022).

Due to the observational design, demographic information about the uploaders (e.g., age, ethnicity, gender) were not collected as they were not readily or explicitly available from the video content. We comment on this in the Discussion.

Analysis

The approach to analysis was Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2019) Reflexive Thematic Analysis (RTA). This was considered appropriate as it has previously been used effectively in the analysis of YouTube related data (Owczarczak-Garstecka et al. Citation2018; Ryan-Vig et al. Citation2019). The approach also acknowledges the active role of researchers in interpreting meaning from data, which the authors felt was important given the way their own lived experiences of self-injury undoubtedly inform the analysis.

Each video was viewed at least twice, firstly during screening for inclusion and secondly for transcription. Multimodal transcription (Bezemer and Mavers Citation2011) was used to capture the multiplicity of visuals, texts, and sounds in the videos. The video description, authored by each creator to accompany their video, was also included in the transcriptions. This process facilitated familiarization with the content, in line with the first phase of Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2020) thematic analysis guidance, and initial notes and preliminary ideas for subsequent coding were made and saved alongside the transcript files.

As the aim of the research was to understand more about the ways that advocacy strategies might be presented by people with lived experience of self-injury, and what this looks like, initial observations of the video formats were made to document the different approaches taken in communicating messages (e.g., vlog, music video). We organized these into general categories of forms in order to summarize differences concisely within the research. Attention then turned to the transcripts, which were transported to NVivo 12 for analysis.

As the video search was guided by the assumed occurrence of advocacy through SIAD related videos we did not have to use a deductive framework of advocacy to guide the analysis. Rather, we took an inductive approach driven by the transcript data with no theoretical framework imposed. Adopting a constructionist epistemology, the initial codes were formed and assigned to the data based on central criteria of meaning and meaningfulness rather than the recurrence of information (Byrne Citation2021). Following this phase, codes with similarities were identified and grouped together in higher order categories. To facilitate real time collaboration between the geographically distant authors in establishing and reviewing themes the codes and categories were copied to Miro (www.miro.com), an online whiteboard tool which facilitates visual mapping. The process of writing-up results and discussion then began, through which the themes were further refined and final names for them were agreed.

Ethics

As YouTube is an open and public platform, data can be collected remotely without the requirement of consent from video creators. However, the ethics of this must still be carefully considered. Patterson (Citation2018) highlights that when working with data from a social media website like YouTube the spheres of public and private become blurred together. Navigating the ethics of this appropriately requires the researcher(s) to determine the individual intention and expectations of the video creator. Posting to an open and public platform like YouTube indicates the post is deliberately intended for public consumption, and that consent can be anticipated (Rodham and Gavin Citation2006). Indeed, YouTube offers creators the option of “hiding” videos from public searches; thus not selecting this option suggests an expectation of public consumption. Legewie and Nassauer (Citation2018) consider the act of posting to YouTube – a high traffic public platform – an indication that public visibility as not just an expectation but the explicit goal.

For this research it was further considered that by identifying their content as associated with SIAD, an event focused on increasing visibility, creators were indicating an openness to their content being publicly disseminated. However, confidentiality of contributors is still required as people may say things online with the expectation of anonymity, and this should be respected (Rodham and Gavin Citation2006). Data was therefore anonymized by removing identifiable details (e.g., usernames) in line with guidance on internet based research from both the Association of Internet Researchers (Franzke et al. Citation2020) and the British Psychological Society (British Psychological Society, Citation2021). To ensure only publicly accessible materials were included, videos necessitating a YouTube membership for access were not included. As the YouTube platform is designed as “a streaming service and not a video depository [to] download and re-catalogue data” (Patterson Citation2018:762) the privacy of creators and the right to be forgotten (Savage and Woloshyn Citation2022) was honored by not downloading videos. Instead, the search procedure was designed to accept – and work with – the potential for video attrition due to the platforms temporal fluidity. This also aligns with the BPS (Citation2021) guidance to only work with data clearly in the public domain without explicit consent.

A further ethical consideration was that the content of the videos could potentially have been distressing for the researcher to view. Regular collaboration and open dialogue between the researchers involved was thus established to allow for any distress to be acknowledged and processed. Approval for the research was granted by the Ethics Committee at Abertay University, Scotland (EMS4988).

Findings

Of the top 30 most viewed videos one video creator was responsible for uploading three videos, and four had uploaded two videos each. The remaining nineteen videos were each posted by different creators. Videos were uploaded between 2012 and 2021. Video length varied from 30 seconds to 15 minutes, and the total number of views videos had garnered ranged from 3,387 to 406,511. The form and occurrence of videos are outlined in .

Table 1. Video Forms and Occurrence.

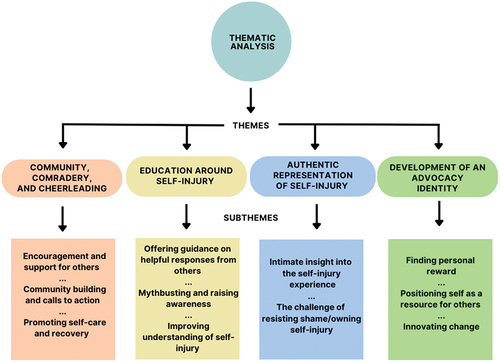

The process of analysis identified 4 themes, and 11 subthemes. These are outlined in .

Theme 1: Community, comradery, and cheerleading

Many videos were concerned with actively supporting the wellbeing of potential viewers, encouraging them to choose life, and to find courage and hope to keep going despite the challenges they might face. The content around this theme indicated that the anticipated viewer was someone who had or was currently engaged in self-injury. There was a sense of acceptance, non-judgment, and comradery; and feeling the maker of the video and the viewer were in it together.

It’s okay not to be okay. There is hope for you. You have a reason to be alive. You can get help. You can get through this I promise. (L)

And you are not your skin. And you are not your skin. And you are not your skin. (E)

Specific emotional challenges for individuals who self-injure were anticipated and resisted through the content, allowing a kind of cheerleading to take place, including countering feelings of being unlovable, “You are loved” (U) feelings of loneliness “I just want to say you’re not alone” (L), and offering validation:

I don’t care if you’re chopping your arm off with an axe or if you’re scratching yourself with your pinkie nail I don’t care, it’s still self-harm and it is still as bad. (F)

I want you to know it everything that you experience a go through is valid no matter what anybody else says (P)

Recognition and promotion of the development of a supportive self-injury community was also included to indicate that help was available, and to call people to both individual and community action. SIAD was a helpful anchor, with the color orange and orange ribbons frequently used as visuals, along with direct calls to support the day. The butterfly project, for which people who self-injure draw a butterfly on their skin and then try to avoid self-injuring and thus “killing” the butterfly, was also mentioned and celebrated as a way to show support and connect with a wider cause.

Speak up, wear something orange today, draw a butterfly or a heart on your wrist. Help us to raise awareness (K)

General calls to action pertained to sharing content, creating content, speaking up, and being there for others.

I hope that by expressing my concern and creating the awareness through my craft, there will be more of you who will also take on this challenge to educate our awesome community in your own ways (N)

Overall, there was a focus on recovery and promoting self-care. This was facilitated by sharing of personal recovery stories, general recovery encouragement, and general self-care strategies. Recovery stories offered encouragement that change was possible, while also acknowledging it was not an easy process.

nowadays like I still do get urges and they arise but I just sit with them and I let them be (M)

Cessation was prized as a tangible goal and encouraged by reminding people of alternative options. Practical self-care strategies were also shared to help empower people toward recovery:

don’t go look at pictures of scars on the internet don’t go look at pictures of cuts, don’t go seeking this kind of content. (F)

self-love is really important and when you reach that point nobody can take that away from you (W)

Here are some alternatives to self-harm: Writing, music, sport, dancing, drawing. If you want, you can even SCREAM. (L)

In summary, this theme captures the deployment of advocacy to establish and maintain a community for individuals with shared experiences around self-injury through YouTube, providing genuine understanding and acceptance alongside encouragement to develop alternative coping resources.

Theme 2: Education around self-injury

Videos contained strong threads of educating audiences. While the previous theme focused on the viewer as an individual who engaged with self-injury, content around this second theme considered a broader viewership. Presentation style of video was common here, lending itself a formal, educational air. Direct guidance was provided for those who might want to support/care for people who self-injure.

We don’t need lectures. We need love. Love. Love. (E)

Judge less, understand more. (L)

A second educational element was myth-busting and raising awareness. Such content often included statistical data and images of celebrities who had self-injured. Common myths (e.g. primarily women self-injure, self-injury indicating a personality disorder) were challenged.

Self injury is not: attention seeking, manipulation, for pleasure, a group activity, cool, a trend, and adrenaline rush, tattooing or piercing, BDSM, a failed suicide attempt (V)

Prevalence was also addressed.

Above 10% of the population, that’s right – yeah I’m surprised, it’s a big number (D)

The third educational point, which nearly every video touched on in some way, was providing information to enhance understanding of self-injury. There was a sense that offering understanding also provided an element of sense-making for the content makers themselves. Understanding was offered around what self-injury is:

self-harming isn’t just about cutting – it can be anything from burning to scratching to pulling hair, anything in any way to hurt yourself. (Q)

And why people might self-injure:

Cutting takes the pain from your mind and your thoughts and memories and puts them directly on your body. (A)

Why? Loneliness. Self-loathing. […] This is my only way out. It’s my alternative to drugs. And it reminds me that I’m real. It reminds me that I’m still alive. (E)

A common framework used to facilitate understanding was that of addiction.

It’s a coping strategy. […] But in the end it becomes a problem of its own. It is an addiction. (G)

Self-harming, it’s an addiction that’s really, really hard to break (M)

Overall, Theme 2 captures creators conscious consideration of broader viewership on YouTube with content designed to inform and educate a range or audiences (e.g. the loved one of a person who has engaged with self-injury) on the practical who, why, and what of self-injury.

Theme 3: Authentic representation of self-injury

A raw and painful representation of the reality of self-injury appeared to be something that was desirable to offer as it was authentic and honest, facilitating trust in the content creator.

That’s so fucked up say and I can’t believe I’m saying this out loud and it’s on the internet, but that’s true, and I want to be honest with you guys (F)

Trust me (M)

Such vulnerable confessionals were seen most frequently in vlogs, but also in the more creative and abstract videos. While the former described their experiences, the latter invited the viewer into the felt sensation of experiences such as loneliness, feeling misunderstood, fighting against the self, not feeling safe, and confusion around self-injury.

We fight and we fail, we fall and we’re fallen

Walking away with less of ourselves

Spiralling and spinning out of control (O)

[clips from a cartoon cut with audio clips from other media] *laughing* just leave, like everybody else. People have hurt you. They didn’t believe you. They didn’t trust you. Didn’t need you. Left you. People have hurt you. They didn’t believe you. They didn’t trust you. Didn’t need you. Left you. (X)

Though visceral and stark at times, such content was balanced with elements from the other themes as well as a sense of resistance, of owning self-injury and the associated stigma. The pressure to hide self-injury was often a main focus.

But why do I hide it? Why wouldn’t I? So I can be called emo? Weak? Pathetic? Stupid? Things I already say to myself? No thanks. (E)

I know what it’s like to pretend to be okay, and I definitely know what it’s like to wear long sleeves in the summer. (L)

There were bold challenges to stigma and shame with attempts to change the narrative of self-injury to one of strength:

Don’t be ashamed of your scars (if you have any), they are signs of strength, you survived! (L)

I believe in these scars, I believe (A)

In exploring this theme a distinction is drawn between content designed to formally educate (seen in Theme 2) and content which invites the viewer to feel and experience elements of self-injury, from the act itself to the underlying emotions and the resistance of stigma which can follow. Different video formats potentially facilitated different levels of engagement for the viewer in this.

Theme 4: Development of an Advocacy Identity

Creators acknowledged that making advocacy content “took a lot of courage” (D) and caused them to get “a little upset” (Q). Yet, they persisted. An element of advocacy videos then was the emerging values and identity of video creators as they addressed why they took on such a challenge. One motivation offered was the reward of helping others.

if this video can help even one person in any way, it will be absolutely worth it to me. (E)

Personal growth and learning was also named, as was the importance of feeling connected to others who personally understood self-injury:

You know I’m just like you

You’re just like me

We block off everything

We got our motives

Our oceans of these little things (A)

The extent of the helping service creators felt they were providing by making videos was interpreted in various ways. Some felt it sufficient enough to signpost to existing resources for self-injury (e.g., websites), while some made implicit offers to be there for support. Others went further, making explicit offers to assist directly:

Contact me on Facebook (E)

Need Help, or someone to listen? Message me - I want everyone to know that I struggled with this too and that you not alone. Because I care about you (R)

Please just DM me, I’m always here for help (W)

Several creators made SIAD related posts across multiple years and had additional content related to self-injury which they actively promoted, indicating an extended commitment to effect change.

I did a whole video actually on self-harm alternatives which I will link in the description below (M)

Potentially helpful resources were also developed directly by the creators. These were distinct from those in Theme 1 as they went beyond tips for individual wellbeing and attempted to position the creator as filling an identified gap or lack in existing services. Examples included a video designed for sharing with loved ones to explain self-injury, testing and reviewing the Instagram self-harm support service, exploring the potential of tattoos for coping with unwanted scars, and the promotion of using a doll to project feelings onto and manage self-injury:

I drew blood on her and I drew stitches, just cuts with stitches. I drew the burns that I have on my wrists. I drew the cuts that I have on my leg. I didn’t want to hurt the doll because I felt so bad for her and I saw I saw the broken part of me in her (D)

Some creators made efforts to expand their audience – and general online presence – by sharing links to additional social media (e.g., Twitter, Snapchat, Instagram). Links to e-mail and podcast were also offered. One creator had discount codes available for promoted products indicating influencer status online. All of this speaks to the advocacy identity being expanded and developed, though only one creator referred to themself using the term “activist.”

In summary, this theme recognizes that by engaging in their own personal growth through the production of YouTube content which advocates for individuals with experience of self-injury creators can offer direct sources of support for others and develop/promote novel and creative helping resources.

Taken together these four themes illustrate advocacy strategies by people with lived experience of self-injury on YouTube exist and largely reflect grassroots advocacy (Smith-Frigerio Citation2020) through efforts to change awareness and understanding, to bridge gaps in service provision, and to influence the wider experience of living with self-injury. There was a strong sense of community building, with educational content and a striving for authentic representation. While advocacy strategies can be recognized, the language used by creators themselves to describe their actions does not formally acknowledge advocacy, with only one creator explicitly labeling themselves as an “activist.” However, there were clear attempts by creators to position themselves as committed to effecting positive change, indicating the process of developing an advocacy-like identity.

Discussion

The primary anticipated audience for videos created appears to be individuals who have first-hand experience with self-injury, indicating an understanding amongst creators that a supportive and informative community is a desired yet often perceived as absent in existing support resources. This aligns with the findings of Lavis and Winter (Citation2020) who showed that young people accessing such content are likely to already be engaging in self-harm and to turn to social media for advice and support after the fact. The secondary anticipated audience seems to be those who care about or are interested in helping someone who self-injures. Further research is required to explore the impact of watching these kinds of videos – for both audiences, as well as those who create and post these videos. For example, in their research around eco-activism through YouTube Sokół (Citation2022) proposes vlogs can be particularly impactful in empowering audiences due to how viewers are positioned as capable of making effective choices. Interview based studies that focus on people’s experience watching such videos (including motives for doing so) would be useful here to gain a deeper understanding in this regard.

The form a video took, and therefore how it communicated its advocacy message, was variable and evidenced a wealth of creativity powered by the openness and vulnerability of the creators. The most viewed videos were songs. This seems to signal a preference for a non-traditional way of sharing information which is emotive and resonant. Similar results were found by Seko and Lewis’s (Citation2018) research into self-injury narratives on Tumblr. It also aligns with Alhassan and Pennington’s (Citation2022) finding that “entertaining” videos were preferred over videos designed purely for educational purposes. The import of non-traditional means of advocacy may therefore represent a useful insight for healthcare and academic professionals in developing valuable, relevant, and desirable digital content.

The nature of advocacy messages were often complex, with video creators wanting to instill hope and support while acknowledging the difficult and challenging elements of their own experience. This messiness appears to be of value, offering an authentic depth to the reality of living with experience of self-injury which may be missed or glossed over in typical, tidier media narratives of overcoming mental health difficulties. Indeed, messages with sole emphasis on hope and positivity may inadvertently invalidate the inherent difficult of self-injury and its related experiences (e.g., co-occurring mental health difficulties). Thus, emphasizing hope alongside ups and downs may resonate more with viewers due to the “reality” being represented. Prior research examining the potential impact of comments to YouTube videos about self-injury found that hopeful messages which concurrently acknowledge the difficulties associated with self-injury may increase more hopeful views toward recovery (Lewis, Seko, and Joshi Citation2018) – ostensibly, as they validate and authenticate people’s true lived experience. Space was also made for narratives of self-injury orientated around strength and survival to emerge, challenging stigma and shame. No creators outright encouraged engaging with self-injury, however there was non-judgment and acceptance for engaging with in the behavior, and a deep appreciation of its potential underlying causes.

Commonly, videos offered insight or meaning as to why people self-harm. In some ways, this aligns with prior research examining self-injury videos on YouTube (Lewis et al. Citation2011) and the Internet more broadly (e.g., Lewis and Baker Citation2011), which found that individuals with lived experience may be motivated to dispel self-injury myths (e.g., challenging the notion that self-injury is attention-seeking) as part of their online communication. The current findings add to this by demonstrating that myth-busting is a key aspect of advocacy work in online videos. This notwithstanding, in the context of this kind of messaging, there remained confusion even amongst the creators themselves as to the functions and mechanisms of self-injury. For example, alongside nuanced self-injury management videos which promoted the complexity of recovery as non-linear and multifaceted (Lewis and Hasking Citation2021, Citation2023) there was content with a more flattened narrative of cessation. This could be an impact of drawing on the framework of addiction, a relatable discourse from which to share experiences of self-injury, particularly the difficulties in trying to stop (Pritchard, Fedchenko, and Lewis Citation2021). Use of an addiction framework, however promotes abstinence, and thus cessation as the only signal of wellbeing, putting it at odds with more nuanced narratives of recovery (Lewis et al. Citation2019), in which self-injury can be conceptualized as a choice. This suggests that part of the advocacy process may be a journey for individual sense-making on the part of the video creator. Making sense of self-injury, confronting shame, and finding meaning by helping others all offer rewards to the video creator and contribute in some way to their identity development. That people experience shifts in how they understand their experiences of self-injury is perhaps unsurprising. Indeed, there is evidence that people not only vary in how they understand and communicate their self-injury experiences (e.g., Pritchard, Fedechenko, and Lewis Citation2021), but that their understandings change over time (e.g., Lewis et al. Citation2019), and can involve finding a sense of meaning, resilience, and purpose (e.g., Farrell, Kenny, and Lewis Citation2024). This may be a helpful insight for practitioners seeking to facilitate meaning-making around self-injury.

In thinking about identity it is useful to draw on Corrigan and Rao (Citation2012) who propose a hierarchy of strategies from which a person makes disclosures about their personal mental health. Ranging from social avoidance to openly broadcasting in order to educate others, one’s stage in the hierarchy is indicative of the movement to reducing self-stigma and increasing personal empowerment, a familiar journey for those navigating disclosure of self-injury (Rosenrot and Lewis Citation2020, Simone and Hamza Citation2020). Growing in confidence around disclosure allows an individual to develop and re-negotiate their identity in relation to their mental wellbeing (e.g. by re-negotiating self-injury scars as a representation of inner strength versus something shameful (Lewis and Mehrabkhani Citation2016). YouTube provides access points for a range of journey stages, with those who conceal their identity somewhere between secrecy and selective disclosure, and those who are fully identifiable being proud broadcasters. This means there are a range of ways the development of agency and resilience could be employed and encouraged in clinical settings (e.g. making a card story may be appropriate for someone closer to the social avoidance stage, while a vlog might be more fitting for someone ready to openly broadcast their experience). Similarly, in the conceptual model of stigma resistance proposed by Firmin et al (Citation2017) a positive anti-stigma identity is developed through deployment of individual knowledge, experiences, and skills across personal, peer, and public levels. YouTube is an ideal medium to facilitate the public level of this, highlighting the importance of having a voice, and the need to hear and see advocacy in its various manifestations to instill much needed hope to wherever people are in their journey.

While the value of YouTube advocacy should be explored further to understand how it might best be harnessed by practitioners and by people with lived experience of self-injury who are looking to implement self-care, the risk of “responsibiliation” (Schermuly et al. Citation2021) and possible detrimental impacts of offering peer support (Lavis and Winter Citation2020) warrant attention. For example, mental health professionals receive specific training around the demands involved in support provision and in strategies to avoid burnout – messaging that was conspicuously absent in our study. Accordingly, resources could be developed and sign-posted for people involved in advocacy-type roles online. Further, there may be merit in ensuring that videos developed and uploaded online are accompanied by supportive resources for viewers (e.g., accessible as links in or beneath the video); similar recommendations have been made more broadly for online self-injury communication (e.g., Lewis et al. Citation2012; Lewis et al. Citation2019).

Implications

Advocacy on YouTube exists and leads to the creation of supportive, passionate, and resourceful content that can potentially make a difference to the wellbeing of individuals who self-injure, countering the narrative that social media content regarding self-injury will have a negative impact. While there are several reports that online self-injury material can be promotive of the behavior (e.g., Mavandadi and Lewis Citation2021), contribute to continued or initiation of self-injury (e.g., Lewis and Baker Citation2011) or otherwise exacerbate loneliness and hopelessness (e.g., Lewis et al. Citation2011, Citation2012) these same studies also point to benefits of online NSSI communication, suggesting that sweeping views that primarily focus on the risks of such online activity, often reported in the media and adopted in public discourses, do not reflect the evidence and may work to undermine the number and impact of positive and supportive messages about self-injury on the Internet (see Lewis and Seko Citation2015) – including those in our study. Hence, the present study adds the role of advocacy to the growing understanding of potentially positive and supportive opportunities of social media in relation to self-injury (Alhassan and Pennington Citation2022; Lavis and Winter Citation2020; Lewis and Seko Citation2015 ; Lewis et al. Citation2018). Moreover, these findings point to the import of not adopting blanket approaches to banning – or criminalizing – self-injury material online.

Looking ahead the present findings set the foundation for several lines of inquiry. Advocacy identity could be further explored, particularly the overlap with peer support. As noted above, understanding the impact of advocacy videos represents an important next step. Relatedly, gaining insight into the types of videos that are most impactful for audiences could help guide future digital advocacy efforts, particularly how such visual media differs generally from written content on specialist message boards or chat forums. This is important considering that these latter forms of online activity are perhaps less salient in the ever-changing landscape of the Internet and the forms of advocacy communication therein. Indeed, YouTube focused research itself should be mindful of the evolution of advocacy strategies as other platforms gain prominence (e.g. TikTok, Instagram).

In doing so, ascertaining who interacts with such content is important. This may also help identify if specific audiences, narratives, or concerns addressed in the context of advocacy are being missed. For instance, a recent study examining trichotillomania videos on YouTube found that most people in the videos were white; thus, people of color may not see themselves in these stories and feel as though their experiences and concerns are under-represented (Ghate et al. Citation2022). This would be valuable knowledge for outreach and professional organizations engaging in their own advocacy work to ensure it resonates with the intended audiences. Participatory research may be useful in exploring the above points, as well as potentially offering insights into how video creators identify their actions and roles online if the terminology of advocacy is not relatable to them. This is especially important as people with lived experience engaging in online “advocacy” may not use this or related terms. Participatory research may thus allow for lived experience views (and concerns) to be meaningfully woven into future research; such approaches have also been highlighted as essential in future self-injury research and outreach work (Lewis and Hasking Citation2020; Lewis and Hasking Citation2023; Lewis et al. Citation2021).

We were limited in our capacity to collect detailed information (e.g., demographics) about who was behind the videos examined. Future work ought to determine who engages in advocacy online and what draws some people to such activity when it comes self-injury. Alongside this is investigating the impact making and posting these videos has on the people who develop them; this seems especially relevant given that online interactions (e.g., video comments) may differentially affect people who post these videos. As noted in the discussion around the research procedure, video results were influenced by YouTube serving videos specific to the UK region; replicating the study in other geographic locations may therefore provide additional insights. Finally, as one of the first studies of this nature in the area of self-injury, we deliberately focused on advocacy through YouTube and selected SIAD as a focal point. Different platforms (e.g., Instagram, Twitter) likely involve different means of advocacy engagement and it cannot be presumed that advocacy will look the same beyond SIAD (e.g., during other times of the year). More work is therefore needed to address these potential gaps, and to generally further the inclusion of varied forms of data/types of participation in relation to self-injury related research (Lewis et al. Citation2021).

In sum, advocacy through YouTube exists and it can take many forms to offer support and resources to those who engage with self-injury. It can look like efforts to change awareness and understanding, to bridge gaps in service provision, and to influence the wider experience of living with self-injury through community building, educational content, and a striving for authentic representation. It is a timely message for those developing related guidance and policy, such as the UK Online Safety Bill, that digital platforms like YouTube have the potential to make meaningful contributions to wellbeing when channeling actions such as advocacy. Further research is required to understand more fully, and harness, this potential.

Acknowledgements

Thanks go to the International Society for the Study of Self-Injury’s Collaborative Research Program, which inspired this project and initiated collaboration between the authors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s)

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Fiona J. Stirling

Fiona J. Stirling is a practicing therapist and a lecturer in Counselling at Abertay University, Scotland. Coming from a background in Social Anthropology, with further qualifications in Education, Psychology, and Youth and Childhood, Fiona is passionate about building collaborative relationships to explore topics of mental health in new ways. Her own lived experience of mental health issues and self-injury increasingly inform both her research and therapeutic practice.

Stephen P. Lewis

Stephen P. Lewis is an academic based at the University of Guelph, Canada. His research program examines non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) and related mental health difficulties among youth and emerging adults. Central to his research approach is the use of the Internet as a research platform and outreach tool. In this regard, his research investigates: a) online NSSI communication, b) ways to increase youth’s access to online NSSI resources, c) NSSI recovery experiences, and d) ways to enhance knowledge and training of those who can support youth who struggle with NSSI and other mental health difficulties.

References

- Adler, Patricia A. and Peter Adler. 2008. “The Cyber Worlds of Self-Injurers: Deviant Communities, Relationships, and Selves.” Symbolic Interaction 31(1):33–56. doi:10.1525/si.2008.31.1.33

- Alhassan, Muhammad Abubakar and Diane Rasmussen Pennington 2022. “ YouTube as a Helpful and Dangerous Information Source for Deliberate Self-harming Behaviours.” Pp. 347–62 in Information for a Better World: Shaping the Global Future (17th International Conference, iConference 2022, Virtual Event, February 28 – March 4, 2022, Proceedings, Part I), edited by Smits Malte, 13192. Strathprints. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-96960-8_23.

- Allgaier, Joachim. 2020. “Science and Medicine on YouTube.” Pp. 7–27 in Second International Handbook of Internet Research, edited by Jeremy Hunsinger, Matthew Allen, and Lisbeth Klastrup. Dordrecht: Springer

- Bandyopadhyay, S and Singh K. 2022. The portrayal of older Indians on YouTube. Educational Gerontology 48(11): 511–535. doi: 10.1080/03601277.2022.2052494.

- Betton, Victoria and Victoria Tomlinson. 2013. “Social Media Can Help in Recovery – but Are Mental Health Practitioners Up to Speed?” Mental Health and Social Inclusion 17(4):215–19. doi:10.1108/MHSI-06-2013-0021

- Bezemer, Jeff and Diane Mavers. 2011. “Multimodal Transcription as Academic Practice: A Social Semiotic Perspective.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 14(3):191–206. doi:10.1080/13645579.2011.563616

- Braun, Virginia and Victoria Clarke. 2019. “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11(4):589–97. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, Virginia and Victoria Clarke. 2020. “One Size Fits All? What Counts as Quality Practice in (Reflexive) Thematic Analysis?” Qualitative Research in Psychology 18(3):328–52. doi:10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- British Psychological Society. 2021. “Ethics Guidelines for Internet-Mediated Research” The British Psychological Society. Retrieved October 3, 2021 (https://www.bps.org.uk/sites/www.bps.org.uk/files/Policy/Policy%20-%20Files/Ethics%20Guidelines%20for%20Internet-mediated%20Research.pdf)

- Byrne, David. 2021. “A Worked Example of Braun and Clarke’s Approach to Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Quality & Quantity 56(3):1391–412. doi:10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y

- Caron, Caroline, Rebecca Raby, Claudia Mitchell, Sophie Théwissen-LeBlanc, and Jessica Prioletta. 2017. “From Concept to Data: Sleuthing Social Change-Oriented Youth Voices on YouTube.” Journal of Youth Studies 20(1):47–62. doi:10.1080/13676261.2016.1184242

- Corrigan, Patrick W and Deepa Rao. 2012. “On the Self-Stigma of Mental Illness: Stages, Disclosure, and Strategies for Change.” The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 57(8):464–69. doi:10.1177/070674371205700804

- Dobson, Amy Shields. 2016. “Girls’ ‘Pain Memes’ on YouTube: The Production of Pain and Femininity on a Digital Network.” Pp. 173–82 in Youth Cultures and Subcultures, edited by Baker Sarah and Robards Brady. Routledge.

- Eysenbach, Gunther, John Powell, Marina Englesakis, Carlos Rizo, and Anita Stern. 2004. “Health Related Virtual Communities and Electronic Support Groups: Systematic Review of the Effects of Online Peer to Peer Interactions.” British Medical Journal 328(7449):1166–70. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7449.1166

- Farrell, B CT, Kenny T E and Lewis S P. 2024.“Views of self in the context of self-injury recovery: a thematic analysis.” Counselling Psychology Quarterly 37(2): 173–191. doi:10.1080/09515070.2023.2193871

- Franzke Aline, S., Anja Bechmann, Michael Zimmer, and Charles Ess. 2020. “Internet Research: Ethical Guidelines 3.0.” The Association of Internet Researchers Retrieved October 5, 2021 https://aoir.org/reports/ethics3.pdf

- Ghate, Rohit, Rahat Hossain, Stephen P. Lewis, Margaret A. Richtor, and Mark Sinyor. 2022. “Characterizing the Content, Messaging, and Tone of Trichotillomania on YouTube: A Content Analysis.” Journal of Psychiatric Research 151:150–56.

- Google. 2022. “Suicide and Self-Harm Policy - YouTube Help”. Retrieved May 3, 2022 (https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/2802245?page=andmaster=suicideradiobuttonandvisit_id=637854570953254282-2318223372andrd=1)

- Hasking, Penelope A., Mark E. Boyes, and Stephen P. Lewis. 2021. “The Language of Self-Injury.” Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease 209(4):233–36. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000001251

- Hattingh, Marie. 2022. “The Dark Side of YouTube: A Systematic Review of Literature.” Adolescences, edited by Ingrassia Massimo and Benedetto Loredana. IntechOpen. doi:10.5772/intechopen.99960

- Holmes, Su. 2017. “‘My Anorexia story’: Girls Constructing Narratives of Identity on YouTube.” Cultural Studies 31(1):1–23. doi:10.1080/09502386.2016.1138978

- Khasawneh, Amro, Kapil Chalil Madathil, Emma Dixon, Pamela Wiśniewski, Heidi Zinzow, and Rebecca Roth. 2020. “Examining the Self-Harm and Suicide Contagion Effects of the Blue Whale Challenge on YouTube and Twitter: Qualitative Study.” JMIR Mental Health 7(6):e15973. doi:10.2196/15973

- Kılınç, Delal Dara. 2022. “Is the Information About Orthodontics on Youtube and TikTok Reliable for the Oral Health of the Public? A Cross Sectional Comparative Study.” Journal of Stomatology, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 123(5):e349–54. doi:10.1016/j.jormas.2022.04.009

- Laverack, Glenn. 2013. Health Activism: Foundations and Strategies. London: Sage.

- Lavis, Anna and Rachel Winter. 2020. “#online Harms or Benefits? An Ethnographic Analysis of the Positives and Negatives of Peer‐Support Around Self‐Harm on Social Media.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 61(8):842–54. doi:10.1111/jcpp.13245

- Legewie, Nicolas M. and Anne Nassauer. 2018. “YouTube, Google, Facebook: 21st Century Online Video Research and Research Ethics.” Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung 19 (3):21 doi:10.17169/fqs-19.3.3130

- Lewis, S P and Baker T G. 2011. “The Possible Risks of Self-Injury Web Sites: A Content Analysis.” Archives of Suicide Research 15(4): 390–396. doi:10.1080/13811118.2011.616154

- Lewis, Stephen P. and Penelope A. Hasking. 2020. “Self‐Injury Recovery: A Person‐Centered Framework.” Journal of Clinical Psychology 77(4):884–95. doi:10.1002/jclp.23094

- Lewis, Stephen P. and Penelope A. Hasking. 2023. Understanding Self-Injury: A Person‐Centered Approach. USA: Oxford University Press.

- Lewis, Stephen P., Nancy L. Heath, Michael J. Sornberger, and Alexis E. Arbuthnott. 2012. “Helpful or Harmful? An Examination of Viewers.” Journal of Adolescent Health 51(4):380–85. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.01.013

- Lewis, Stephen P., Nancy L. Heath, Jill M. St Denis, and Rick Noble. 2011. “The Scope of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury on YouTube.” Paediatrics 127(3):e552–57. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-2317

- Lewis, Stephen P., Nancy L. Heath, and Rob Whitley. 2021. “Addressing Self-Injury Stigma: The Promise of Innovative Digital and Video Action-Research Methods.” Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health 40(3):45–54. doi:10.7870/cjcmh-2021-020

- Lewis, S P, Kenny T E, Whitfield K and Gomez J. 2019. Understanding self‐injury recovery: Views from individuals with lived experience. Journal of Clinical Psychology 75(12): 2119–2139. doi:10.1002/jclp.22834

- Lewis, S P and Knoll A K. 2015. Do It Yourself: Examination of Self-Injury First Aid Tips on YouTube. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 18(5): 301–304. doi:10.1089/cyber.2014.0407

- Lewis, Stephen P. and Saba Mehrabkhani. 2016. “Every Scar Tells a Story: Insight into people’s Self-Injury Scar Experiences.” Counselling Psychology Quarterly 29(3):296–310. doi:10.1080/09515070.2015.1088431

- Lewis, Stephen P. and Yukari Seko. 2015. “A Double-Edged Sword: A Review of Benefits and Risks of Online Nonsuicidal Self-Injury Activities.” Journal of Clinical Psychology 72(3):249–62. doi:10.1002/jclp.22242

- Lewis, Stephen P., Yukari Seko, and Poojan Joshi. 2018. “The Impact of YouTube Peer Feedback on Attitudes Toward Recovery from Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: An Experimental Pilot Study.” Digital Health 4:205520761878049. doi:10.1177/2055207618780499

- Marchant, Amanda, Keith Hawton, Lauren Burns, Anne Stewart, and Ann John. 2021. “Impact of Web-Based Sharing and Viewing of Self-harm–related Videos and Photographs on Young People: Systematic Review.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 23 (3):e18048. doi:10.2196/18048

- Mavandadi, Veesta and Lewis Stephen P. 2021. Pro-self-harm: Disentangling self-injury and eating disorder content on social media. Suicidology Online 12(1).

- Misoch, Sabina. 2014. “Card Stories on YouTube: A New Frame for Online Self-Disclosure.” Media and Communication 2(1):2–12. doi:10.17645/mac.v2i1.16

- Morahan-Martin, Janet. 2004. “How Internet Users Find, Evaluate, and Use Online Health Information: A Cross-Cultural Review.” Cyberpsychology & Behavior: The Impact of the Internet, Multimedia and Virtual Reality on Behavior and Society 7(5):497–510. doi:10.1089/cpb.2004.7.497

- Osman, Wael, Fatma Mohamed, Mohamed Elhassan, and Abdulhadi Shoufan. 2022. “Is YouTube a Reliable Source of Health-Related Information? A Systematic Review.” BMC Medical Education 22(1). doi:10.1186/s12909-022-03446-z

- Owczarczak-Garstecka, Sara C., Francine Watkins, Rob Christley, Huadong Yang, and Carri Westgarth. 2018. “Exploration of Perceptions of Dog Bites Among YouTube™ Viewers and Attributions of Blame.” Anthrozoös 31(5):537–49. doi:10.1080/08927936.2018.1505260

- Patterson, Ashley N. 2018. “YouTube Generated Video Clips as Qualitative Research Data: One Researcher’s Reflections on the Process.” Qualitative Inquiry 24(10):759–67. doi:10.1177/1077800418788107

- Pritchard, Tyler R., Chelsey A. Fedchenko, and Stephen P. Lewis. 2021. “Self-Injury Is My Drug: The Functions of Describing Nonsuicidal Self-Injury as an Addiction.” Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease 209(9):628–35. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000001359

- Raun, Tobias. 2018. “Capitalizing Intimacy: New Subcultural Forms of Micro-Celebrity Strategies and Affective Labour on YouTube.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 24(1):99–113. doi:10.1177/1354856517736983

- Rodham, Karen and Jeff Gavin. 2006. “The Ethics of Using the Internet to Collect Qualitative Research Data.” Research Ethics 2(3):92–97. doi:10.1177/174701610600200303

- Rosenrot, Shaina A. and Stephen P. Lewis. 2020. “Barriers and Responses to the Disclosure of Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: A Thematic Analysis.” Counselling Psychology Quarterly 33(2):121–41. doi:10.1080/09515070.2018.1489220

- Ruth, Firmin, Lauren Luther, Paul Lysaker, Kyle Minor, John McGrew, Madison Cornwell, and Michelle P. Salyers. 2017. “Stigma Resistance at the Personal, Peer, and Public Levels: A New Conceptual Model.” Stigma and Health 2(3):182. doi:10.1037/sah0000054

- Ryan-Vig, Selena, Jeff Gavin, and Karen Rodham. 2019. “The Presentation of Self-Harm Recovery: A Thematic Analysis of YouTube Videos.” Deviant Behavior 40(12):1596–608. doi:10.1080/01639625.2019.1599141

- Sangeorzan, Irina, Panoraia Andriopoulou, and Maria Livanou. 2019. “Exploring the Experiences of People Vlogging About Severe Mental Illness on YouTube: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis.” Journal of Affective Disorders 246:422–28. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.119

- Savage, Michael and Vera Woloshyn. 2022. Ethical and Methodological Considerations when Using Social Media Sites as Data Sources: Lessons Learned from a Youtube Case Study. SAGE research methods: doing research online. USA: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Schermuly, Allegra Clare, Alan Petersen, and Alison Anderson. 2021. “‘I’m Not an activist!’: Digital Self-Advocacy in Online Patient Communities.” Critical Public Health 31(2):204–13. doi:10.1080/09581596.2020.1841116

- Schuman, Donna L., Karen A. Lawrence, and Natalie Pope. 2019. “Broadcasting War Trauma: An Exploratory Netnography of Veterans’ YouTube Vlogs.” Qualitative Health Research 29(3):357–70. doi:10.1177/1049732318797623

- Seko, Yukari and Stephen P Lewis. 2016. “The Self—Harmed, Visualized, and Reblogged: Remaking of Self-Injury Narratives on Tumblr.” New Media & Society 20(1):180–98. doi:10.1177/1461444816660783

- Simone, Ariana C. and Chloe A. Hamza. 2020. “Examining the Disclosure of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury to Informal and Formal Sources: A Review of the Literature.” Clinical Psychology Review 82:101907. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101907

- Smith-Frigerio, Sarah. 2020. “Grassroots Mental Health Groups’ Use of Advocacy Strategies in Social Media Messaging.” Qualitative Health Research 30(14):2205–16. doi:10.1177/1049732320951532

- Sokół, Malgorzata. 2022. ““Together We Can All Make Little Steps Towards a Better world”: Interdiscursive Construction of Ecologically Engaged Voices in YouTube Vlogs.” Text & Talk 42(4):525–46. doi:10.1515/text-2020-0089

- Van Dijck, José. 2013. YouTube Beyond Technology and Cultural Form. Pp. 147–160 in After the Break, Television theory today, edited by J. Teurlings and Marijke de Valck. Netherlands: Amsterdam University Press. doi:10.1017/9789048518678.

- Woloshyn, Vera and Michael J Savage. 2020. “Features of YouTube™ Videos Produced by Individuals Who Self-Identify with Borderline Personality Disorder.” Digital Health 6:205520762093233. doi:10.1177/2055207620932336

- Zoller, Heather M. 2005. “Health Activism: Communication Theory and Action for Social Change.” Communication Theory 15(4):341–64. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2005.tb00339.x