Abstract

Everything a person does generates a unique experience of occupational value, and occupational values can in turn generate meaning in life. Doing creative activities positively influences subjective health and well-being. This article provides information about how and to what extent people diagnosed with mental illness experienced occupational value when participating in an intervention with creative activities. Thirty-three participants provided data within a mixed-methods design. Data were analyzed by quantitative non-parametric statistical methods and qualitative directed content analysis. Interventions with creative activities enable a high degree of experienced occupation value and are associated with all dimensions in the occupational value triad.

Introduction

Experiences of occupational value (OV), according to the Value and Meaning in Occupations (ValMO) model (Erlandsson & Persson, Citation2020; Persson et al., Citation2001), are generated in everyday doing and the occupational values form meaning in life. Meaning in everyday life is in turn a prerequisite for subjective health (Erlandsson et al., Citation2011). To recognize and explore occupational value thus seems important in relation to occupational therapy that uses occupations as interventions. OV is presented in the ValMO-model (Persson et al., Citation2001) as a concept to describe the experiences of engaging in occupations. Occupational therapists benefit from understanding why and which occupations will motivate and enhance engagement and participation in life to facilitate health, well-being, and recovery (Billock, Citation2013). This study explores the OV experienced by people with mental illnesses in psychiatric settings when engaged in creative activities as an intervention (CaI).

Value is a core concept in occupational therapy (e.g., AOTA, Citation2014; Kielhofner, Citation2008). One perspective of value may be understood as personal values developed during an individual’s lifespan, providing an understanding of and beliefs regarding what is right and wrong, and thereby determining a way of life and everyday activity (Billock, Citation2013; Kielhofner, Citation2008). Furthermore, personal values influence the values that are attached to occupations, i.e., important facets that have an impact on a person’s subjective experience of occupation. According to the ValMO model (Persson et al., Citation2001), perceived value is associated with occupations in daily life that thereby influence the overall experience of meaning. OV is a core concept in the ValMO model. The experiences, generated in performing an occupation, are operationalized as three parallel dimensions of OV that are all potentially present with variations in intensity. The three OV dimensions are concrete, socio-symbolic, and self-rewarding, and these dimensions are incorporated in every occupation (Erlandsson et al., Citation2011; Erlandsson & Persson, Citation2020). The concrete OV dimension concerns the visible features of one's doings, characterized by their tangibility. The socio-symbolic OV dimension regards the social, cultural, and universally experienced value of doing an occupation. Finally, the self-reward OV dimension concerns the immediate rewards that are inherent in the experience of doing a certain occupation (Erlandsson & Persson, Citation2020).

Creative activities are defined in the literature as any meaningful arts-based activity that evokes a creative process in an individual (Perruzza & Kinsella, Citation2010) and often results in a product, such as a painting or a poem (Gunnarsson & Björklund, Citation2013). CaI is defined in this study in the form of five attributes that were found in a systematic literature review of 15 articles between 2003 and 2016. The attributes defining CaI were: (1) often consisting of elements of arts and crafts using mind and body, (2) being experienced as meaningful, (3) creating creative processes, (4) developing skills and managing everyday life; and (5) being easy to modify individually or in groups with different approaches (Hansen et al., Citation2020).

The use of CaI has a long history in psychiatric occupational therapy practice (Caddy et al., Citation2012; Leckey, Citation2011) and is rooted in the understanding that CaI can facilitate a variety of needs, such as relaxation, diminishing disturbing thoughts, and aiding in a therapeutic relationship (Perruzza & Kinsella, Citation2010; Reynolds, Citation2000). People with a lived experience of mental illness often have difficulties performing everyday life skills, such as personal self-care and maintaining relationships (Cordingley & Pell, Citation2014), and are marginalized and deprived of occupations (Townsend, Citation2012). Furthermore, mental illnesses can result in periods of hospitalization. Individuals who are patients at psychiatric hospitals can be challenged with exhaustion, difficulties in concentrating, and low motivation, which have been identified as barriers to engaging in a rehabilitation process (Hickey, Citation2016). Occupational therapists use CaI in the mental health services to reduce these secondary consequences of being hospitalized and as a means of bringing about change in an individual’s function and performance (Walters et al., Citation2014). The literature focusing on the participatory effects of doing CaI and the specific influence of CaI on rehabilitation and the strengthening of everyday life is sparse (Horghagen et al., Citation2014; Saavedra et al., Citation2018). Experiences of participating in Cal have been documented in research. Perruzza and Kinsella (Citation2010) used a matrix method literature review of 23 peer-reviewed articles on creative arts as a therapeutic medium. They concluded that the experiences from participating in CaI enhanced the patients’ perceived control, built a sense of self and expression, transformed their illness experience, and helped them gain a sense of purpose and social support. When humans are active and creative, they evolve through what they experience as meaningful and this leads to an increased ability to perform daily activities and participate in community life (Eklund et al., Citation2010; Horghagen et al., Citation2014). Experiences from doing could be described by the dimensions of occupational value. There is, however, still limited research available about the experiences of OV, specifically associated with occupations that are used as an intervention. There is a lack of information about the experiences of occupational value (OV) when doing CaI and about whether and how experiences of individual variations in OVs can be detected during the course of doing CaI. Such variations are expected, according to the assumptions in the ValMO-theory however, empirical descriptions of it are still rare. Such understanding might clarify the benefits and contribute to how and if these experiences facilitate recovery processes and increased health and well-being. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore how and to what extent people with mental illness experience OV when participating in a CaI process and their reflections on experienced value during the process. Furthermore, the study aimed at exploring any differences in experienced OV between two points in time during the process.

Methods

Study design

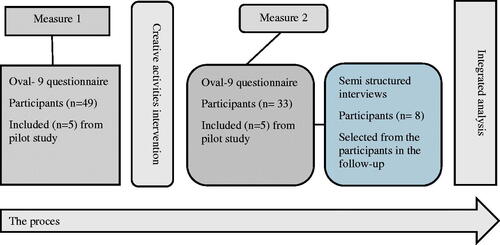

An explanatory sequential mixed-methods design (Creswell & Poth, Citation2017) was chosen to gain a comprehensive understanding of the experience of OV and if and how experiences of individual variations in OVs differ in the process of doing CaI. The specific mixed methods design is shown in .

Furthermore, the study’s design included a reference group (Bradbury-Huang, Citation2010) consisting of four users of CaI and two members of the staff from the facility providing CaI in workshops. This group was involved throughout the research process and collaborated with the first and third authors on three occasions to plan and discuss the research process before and after the pilot study and to review the findings as peers after the data analysis.

Study setting

The study was conducted at a Danish psychiatric hospital where workshops providing CaI were given. The workshops were held by workshop assistants who had an education in crafts and/or health and educational training under the leadership of an occupational therapist. The overall objective of the interventions was to promote activities in everyday life, such as being able to perform self-care and strengthening the participants’ experiences of being active. The interventions had to consist of elements of arts and crafts, creating creative processes, developing skills, and being easy to modify individually or in groups with different approaches for specific intervention goals in different settings. The participants could choose from seven workshops: leather, jewelry, recycling shop, drawing/painting, pottery, metal, and carpentry. Ten (half-day) weekly sessions, 2–3 h in length were available. The participants took part in an average of seven sessions over a period of 5–16 days during the intervention process. The participants chose which workshops to attend, the number of sessions, and if they wanted to create products for themselves or for sale.

Selection and sample of participants

The sample included individuals with mental health diagnoses (see ), according to ICD 10 (WHO, Citation1992), who had recently (<1 week) started in the workshops, either as inpatients or outpatients taking part in rehabilitation programmes financed by the municipality. All were referred to the workshops providing CaI. The specific inclusion criteria were inpatients or outpatients who were able to complete the questionnaires and take part in the interviews. The exclusion criteria were not being able to complete the study due to, for example, cognitive difficulties or deterioration of the condition. All the participants were consecutively and conveniently recruited (Creswell & Poth, Citation2017) over a period of six months by the therapy staff, in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. One hundred and nineteen clients were referred to the intervention in the workshops during the research period, seventy of whom were not included mainly due to declining participation or being too ill to participate in the study. The final sample of possible participants for the study comprised 49 individuals who completed the questionnaire at measure point one (M1).

Table 1. Characteristics of the Participants in M2

Sixteen dropped out due to deteriorating health, being discharged, or withdrawing from the study. The remaining 33, mainly inpatients (n = 31), completed the questionnaire at measure point two (M2) and eight of these participated in the semi-structured interviews. For sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the participants, see .

Data collection

Sociodemographic data were collected in a questionnaire consisting of age, gender, education, patient status, civil status, source of income, type of workshop, and self-reported diagnoses. The Occupational Value-nine items (OVal-9)-questionnaire (Persson & Erlandsson, Citation2010) was used to assess the patients’ experiences of OVs when participating in CaI. The individual rates the level of experienced OV in performing a specific occupation in accordance with the ValMO model when completing the self-rated OVal-9 questionnaire (Persson et al., Citation2001). The questionnaire focuses on experiences of OV immediately after completing an occupation. The nine items reflect the three value dimensions of the OV triad, and the items are randomly presented in the instrument. The degree of the experience of the specific value is rated on an ordinal scale from 1 (to a low degree) to 7 (to a high degree). The instrument has been shown to have good content validity among a sample of occupational science experts, occupational therapy students, and clients (Persson & Erlandsson, Citation2010). The authors concluded that the questionnaire had a good ability to assess the value that people experience in their daily occupations.

A semi-structured interview guide was developed to provide a greater understanding of the participants’ experiences of OV in participating in the CaI process. The interview guide was designed by the first author based on the structure and content of the OVal-9 questionnaire. An example of the general structure and content of the questions is: you rated this question X with 7, can you elaborate on how you were thinking?

Procedure

A pilot study including five participants, selected according to the inclusion criteria, was initially conducted to evaluate the feasibility, time, cost, and adverse events, and to improve the study design before carrying out a full-scale research project (Ismail et al., Citation2017). The pilot study resulted only in minor changes, such as in the distribution of the questionnaires, and the data from the five participants were thus included in the total sample.

The OVal-9 questionnaire was independently completed by the participants both at measures one and two, with a maximum of 30 min after participating in a CaI. The questionnaire was distributed and briefly explained by the workshop assistant. The interviews were carried out after completion of the OVal-9 questionnaires at measure point 2 and were conducted by an occupational therapist experienced in working with people with mental illness. The interviews were conducted in a room that was well-known to the patients in the workshop facilities. The interviews were carried out during a period of six months, and all were recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim. All the participants in the study signed informed consent.

The research project was approved for health science research in Region Zealand (REG-201-2017) by the Danish Data Protection Agency. The study complies with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration II (General Assembly of the World Medical Association, Citation2014).

Data analysis

Demographic data, except age, were described using descriptive statistics, and age was presented in mean years (). The ratings in the OVal-9 were clustered in three levels for this study: 1–3 denoted a low degree of OV, 4 was considered as a non-aligned rating and ratings from 5 to 7 denoted a high degree of OV. Each of the OVal-9 item ratings was analyzed using percentage distribution. An overall score and the three dimensions of OV were calculated and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to determine any statistically significant change in OV score between measures one and two. The significance level was set at 5% and the test was two-sided. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 25) was used.

The interview data was processed using content analysis with a directed approach (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). A deductive method was used in this study as we wanted the participants to elaborate on their thoughts about their scores according to the three value dimensions, respectively. The three dimensions of occupational value were the focus of this part of the research analysis. The first and third authors completed the first step of the analysis and independently read the transcripts several times to gain a sense of the whole, focusing on elements concerning OV in the text. The three OV dimensions were used as a screening pattern for sorting the meaning units in the second step of the analysis. The meaning units were then condensed, clustered, and initial codes were identified. These were then finally grouped together into categories and sub-categories illustrating aspects of the three OV dimensions, respectively. All the authors were involved in this final part of the content analysis. These results were presented to the reference group who recognized the findings of the analysis.

Results

The overall results indicated that doing CaI among a group of people with mental illness provided a high level of experienced OV, which is associated with all the value dimensions in the OV triad.

Level of occupational value at measures one and two

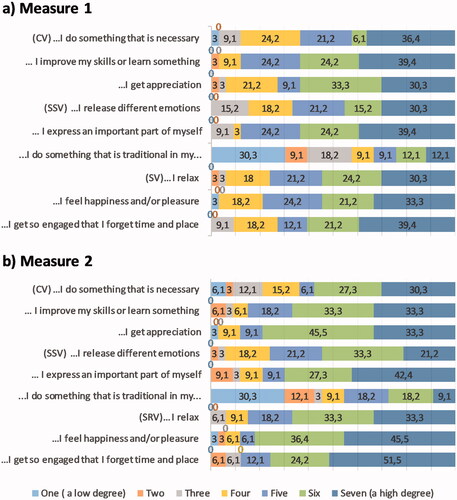

The participants’ ratings of their experiences of OV in doing CaI are presented in . Most of the participants rated most of the items in the questionnaire between 5 and 7 at both measurements, i.e., the three OV dimensions were all experienced while performing the CaI. There was no statistically significant difference (p = .54) in overall ratings between M1 and M2. The same results were found regarding change in the three OV dimensions between M1 and M2 (concrete value p = .87, socio-symbolic value p = .90 self- rewarding value p = .08). A statistically significant difference was found for the item …I feel happiness and/or pleasure (p = .03) when exploring the changes between M1 and M2 in OV at the item level. The item with the highest rating was, …I get appreciation, as a total of 72.7% of the participants rated experiencing appreciation to a high degree at M1 (). Fewer than 50% of the participants (33,3% at M1 and 45,5% at M2) rated the item … I do something that is traditional in my culture or in my family, to a high degree.

Figure 2. Percentage distribution of occupational values (measure 1 and measure 2). (a) Measure 1. (b) Measure 2. The figure displays the percentage distribution of the experiences from 1 to 7 of the responses to the nine items of OVAL-9. Light blue = 1 (a low degree), orange = 2, grey = 3, yellow = 4, blue = 5, green = 6, dark blue = 7 (a high degree). Note that not all the response categories were used for some items. This is indicated with the value of 0 between adjacent categories.

Experiences of occupational value when participating in CaI

Twenty-one subcategories were formed from the analysis of the informants’ experiences of OV when doing CaI and together these formed eight categories in accordance with the OV triad presented in . Quotations from anonymized participants are provided to illustrate the categories found.

Table 2. Sub-Categories and Categories of Experiences of Occupational Value of CaI According to the Occupational Value Triad

Concrete occupational value

The three categories describing the experiences related to the first of the triad of concrete OV in participating in CaI were identified as: return to everyday life, new meaningful activity, and having a work and a possibility to develop as an artist. Participating in CaI provided motivation and energy for physical training, to participate in social activities and it was recognized as social training in terms of regaining a social life. Furthermore, the participants reverted to carrying out daily routines by doing CaI, “I’ve started getting up at 8′ o clock when my husband leaves and doing something – before I was just lying in my bed” (Karen). CaI provided substance for their days by maintaining a structure, an everyday rhythm, and giving them something to do and look forward to. CaI was a new meaningful activity that the participants recognized as being of concrete occupational value as it entailed new activities, both in and outside the hospital. The participants spoke of the importance of making room for creative activities since these activities had not been prioritized before the intervention. Participating in CaI meant working professionally, learning arts and crafts, and developing as an artist in terms of creative expression and technical artistic processes. Participating in CaI was described as serious work, which entailed making marketable creative products in appropriate facilities.” Is it serious work? Yes, my children say; do you need to work today?” (Rose).

Socio-symbolic occupational value

The three categories describing the experiences related to socio-symbolic OV when participating in CaI were identified as strengthened identity and recognition, belonging, and self-expression.

Participating in CaI generated a feeling of a "normal" identity and increased self-esteem. Recognition of the creative product created a feeling of “being someone.” The feeling of having an occupation that was recognized by others was highlighted. “Even though you are somewhat different, you can still have something that can be seen as being normal” (Mona). The socio-symbolic OV of belonging to different subgroups when performing CaI was illustrated. The social community was recognized by the participants as a way of seeing themselves through the lives of others. This was possible through confidential peer contact and support, reflection, and being provided with a different perspective on their situation. The stories of others created hope. “Talking to co-patients – some who have come further than I have – then you know that there’s light out there somewhere. If you just dare to find it” (Eva).

The participants also emphasized the importance of getting guidance from staff and being part of a creative community individually or within a common project doing creative activities. One could express oneself creatively with the others who gave feedback on one’s creative work in these communities. Doing CaI made sense due to it being a part of the tradition and culture in the participants’ families or due to their educational background. Belonging and being able to produce things and sharing common creative interests with relatives provided opportunities for socializing and fellowship. The experiences of OV doing CaI in a caring and accommodating setting could initiate inner processes of self-expression and create a visible physical form of feelings. By expressing themselves artistically, the participants were able to reflect on their mental status, their identity, and feelings. “… it’s a part of me that comes out on the paper or canvas. So, I could see it very clearly how I felt mentally” (Tina). Difficult aspects of life could be expressed by participating in CaI and it thus helped to deal with negative energy and sad or frustrating feelings.

Self-rewarding occupational value

The two categories describing the experiences related to self-rewarding OV when participating in CaI were identified as: positive emotions and well-being, distraction, and creating a “free space.” The statements revealed that doing CaI generated self-confidence, positive emotions, and well-being. “It gives me peace, excitement, and joy” (Megan). Carrying out creative activities was valued as something joyful promoting a better mood and tranquility, which was calming, relaxing, and stress-reducing. Doing CaI was described as a distraction that created a ‘free space’ from tiresome thoughts. The participants spoke of their brain pausing by focusing on doing something pleasant. “It’s as if I forget time and place when I make art – it’s like reading a good book” (Karen). Doing CaI helped to find peace and relaxation and created a break from the everyday routines. “It’s a sanctuary to look out for as it provides a respite both in and outside the hospital” (Eva).

Discussion

Mixed methods were used to explore to what extent and how people with mental illness experience OV when participating in a CaI process. The combination of the results from the quantitative and the subsequent qualitative descriptions of the OV experiences strengthened the findings, i.e., the extent of the OV experiences and how these were described, respectively. Most of the participants experienced a high level of OV both at M1 and M2. The participants’ experiences of participating in CaI were associated with all three OV dimensions. No statistically significant differences were found between M1 and M2 in the ratings of the summarized items constituting the three OV dimensions, respectively. Furthermore, only one of the single items, referring to experiences of happiness and/or pleasure was found to significantly differ between M1 and M2. An explanation for this may be that most of the immediate experiences reflected in the instrument are important elements, no matter where individuals are in their recovery process.

Experiences of concrete OV

There was a high level of experienced concrete OV, e.g. I get appreciation (72,7% at M1 and 87,9% at M2) but no statistically significant differences in any of the subscales regarding concrete OV, between M1 and M2. This result was not expected. Theoretically, a change in experienced concrete value was expected since an improvement in skills and routines in relation to the workshops were assumed to increase during the intervention and thereby the satisfaction with the products made. The qualitative part of this study illustrates that skills and routines were, however, developed by participating in CaI, i.e., learning arts and crafts and developing as an artist through creative expression. Developing artistic skills and competencies in the technical artistic process of doing CaI, were found purposeful.

The concrete OV when doing CaI was, according to the participants’ statements, experienced as a “work like” activity that provided substance, rhythm, and energy in everyday life. Half of the participants were unemployed. Having a worker role is perceived as a basic part of daily life among the adult population in Western cultures (Kielhofner, Citation2008). The intervention meant a meaningful work-like activity i.e., having work hours, assignments, and producing something. Similar aspects have been found to be important in the recovery process e.g., having routine occupations. This is in line with the qualitative study by Hocking et al. (Citation2012) among people in recovery from mental illness, where engaging with others and meeting expectations generated a sense of stability and structure as well as achievement and worth. The importance of regular commitment is important in relation to occupational balance and is closely connected to the experience of occupational health (Wagman et al., Citation2012).

Experiences of socio-symbolic OV

There were no significant differences in the ratings of the experiences of socio-symbolic OV dimensions or any of the three single items of OV, between M1 and M2. Nevertheless, the experiences of socio-symbolic OV when participating in CaI were highlighted in the qualitative part of the study. Participating in CaI enabled a sense of identity as “normal and being someone” through the recognition of others, of the creative product, and of being an artist. Lloyd et al. (Citation2007) reported that doing CaI provided a sense of worth and value. Furthermore, the experience of belonging to different subgroups i.e., a social group, a creative community or the family was found within this dimension of OV when doing CaI. Positive experiences of being able to manage and complete activities like CaI may contribute to a better subjective health experience and generate positive expectations of being able to perform necessary activities in everyday life (Erlandsson et al., Citation2011).

Experiences of self-rewarding OV

There were no significant differences in the summarized rating of the three single items in the self-rewarding OV dimension, between M1 and M2. A statistically significant difference in rating was, however, found for one of the three single items, which concerned happiness and/or pleasure. The change in the experience of this item in doing CaI, may highlight the difficult challenge of experiencing happiness and pleasure at an early stage of mental illness where depression, anxiety, and psychoses are commonly present. This finding may thus be a consequence of the fact that most participants in this study were inpatients and therefore in an acute phase of their illness. The change in experiences between M1 and M2 reflects a step in a positive recovery process where the ability to experience and be aware of times of happiness and pleasure, improves. The experience of OV when doing CaI contributes to feelings of happiness and pleasure in being and doing something can thus be understood in relation to concepts of “doing” and “being” (Wilcock, Citation2002). “Doing” can provide experiences of satisfaction and happiness if we are doing what we want or enjoy doing. “Being” is about being true to ourselves, having time to discover oneself, to think, to reflect, and to simply exist (Wilcock, Citation2002).

Most of the participants experienced the item “…I get so engaged that I forget time and place,” to a high degree at both M1 and M2. The experiences spoken of by the participants in relation to the self-rewarding OV dimension reflected aspects used in describing flow (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1997). Self-reward value focuses on immediate rewards that are inherent in the experience of performing a certain occupation (Persson et al., Citation2001). Doing CaI was appreciated as it allowed the participants to relax, and their mental activity was relieved for a while. Experiences that can relate to the concept of flow thus appear to be an important part of the dimension of self-reward OV when doing CaI and thus an important point to consider in the planning and development of CaI.

Finally, Schmid (Citation2005) states that becoming aware of the value of creative occupations and making these a part of everyday occupations can be a positive way of getting the best out of negative disruptions in life. Applying the OVal-9 questionnaire and facilitating the awareness of OV in doing CaI can thereby encourage the individual to transform the experiences of doing CaI into other activities (Persson & Erlandsson, Citation2010).

Doing CaI as a strategy for mental health recovery

The results of the present study showed a high degree of perceived occupational value when participating in CaI during the intervention process. The ValMO model developed by Persson et al in 2001 assumes that the meaning we develop from our experiences of occupational value in daily activities is crucial for maintaining good health and well-being. The experiences of OV could thus be a way to illustrate how participating in CaI is a therapeutic factor facilitating the recovery processes in mental health.

A strong relationship between CaI and mental health recovery was identified in a study by Stickley et al. (Citation2018). Experiences of doing CaI related to this framework of recovery processes have been reported elsewhere (Lloyd et al., Citation2007; Stickley et al., Citation2018). There are similarities between the expressed experiences of doing CaI, from the interviews and items in the Oval-9 questionnaire, in this study, and these core processes.

CaI was described as being purposeful, fulfilling, and applicable to the participant’s lives, and doing CaI led to concrete products that were of value to the client and/or to other persons. These experiences are in accordance with the core recovery process (Leamy et al., Citation2011). There were also statements in the analyzed interviews that corroborate that CaI facilitated motivation and energy for returning to everyday life. These experiences can also be related to the core recovery process as Stickley et al. (Citation2018) found that experiences of doing CaI built empowerment. A sense of identity through the recognition of others, of the creative product, and of being an artist was experienced in doing CaI in our study. Stickley et al. (Citation2018) suggest that the experience of doing CaI may play a major role in the rebuilding of a new identity in the recovery processes. In a concept analysis of occupational identity by Hansson et al. (Citation2022) it was concluded that what one does connects not only to who one is but more so, to belongingness. The findings in their study thus validated the significant connection between occupation and identity through doing, being, and future becoming.

Connectedness in the recovery process (Stickley et al., Citation2018) was recognized in our study by the participants’ expressed appreciation of the fellowship, support, and guidance from staff and peers. Furthermore. a sense of hope was described and categorized as being related to the socio-symbolic value of doing CaI. This is in accordance with Stickley et al. (Citation2018) who identify the core recovery process hope in doing CaI.

Exploring the experiences of OV when doing CaI, may thus be relevant when supporting the recovery process of those with mental illness. Whether the experiences of OVs, as assessed in the Oval-9 questionnaire, can be used as a way of measuring conditions that can facilitate recovery needs to be examined further.

Limitations and methodological consideration

The rationale for choosing this mixed-method design was to obtain a more comprehensive view than either the quantitative or the qualitative perspective can give (Creswell & Poth, Citation2017). The consecutively purposefully collected sample was small and the external validity and generalizability of research results are thus limited. The CaIs that were available at the workshops were monitored to ensure that they mirrored the selected definitions of CaI. It was important to ensure that the qualitative data explained the quantitative data as the study had an explanatory sequential design. The interviews were thus conducted immediately after the completion of the OVal-9 questionnaires at M2. This, however, may also be a disadvantage as the questions in OVal-9 could influence and adversely affect the answers in the interviews. The participants interviewed at M2 are representative of the total sample (see ) in spite of a variation in terms of self-reported diagnosis, civil status, and type of workshop. The deviation from the total sample thus means that the experiences of the interviewed participants may be characterized by the perspective of this sample of participants. Strategies were applied to ensure the trustworthiness of the qualitative data analysis. A researcher triangulation was applied where all the authors were involved in the steps of the analysis, category agreement by all the authors was achieved, and the findings were reviewed by the reference group to ensure whether the result of the data analysis was congruent with experiences among peers i.e. a member triangulation (Creswell & Poth, Citation2017). However, credibility could have been further ensured by returning to the participants to confirm or falsify the results of the analysis and the interpretations made.

Dependability is a key aspect of trustworthiness in qualitative research, which involves a detailed research audit trail outlining every detail of the research process (Creswell & Poth, Citation2017). The research audit trail was discussed by three of the authors throughout the research process.

One item in the OVal-9 instrument; “I do something that is traditional in my culture or in my family…,” had a different distribution of percentages in the rating (1–7). Eklund et al. (Citation2009) found a similar item (concerning traditions) that differed from the others in a study of the psychometric properties of the related OVal-pd questionnaire. The difference in the distribution of this specific item in that study was explained as it was possibly an “external” aspect of socio-symbolic OV. It thus does not necessarily represent something that has been considered valuable by the individual and therefore may be rated lower. A similar explanation can apply to the varying distribution of the item referred to in the current study. It is thus important to carry out further validation studies with larger, similar, or different, populations to investigate whether the items in OVal-9 would, for example, fit a Rasch analysis (Hagquist et al., Citation2009).

Furthermore, the lack of statistical significance indicates that the OVal-9 questionnaire may not be useful for assessing changes in intervention outcomes at least not in the timeframe of the current study. Personal experiences of OV reflect here and now and are thus dependent on e.g., where an individual is in the recovery process. There are no published psychometric studies of the instrument to date and there is thus an urgent need for further exploration of the qualities of the questionnaire.

Conclusion

This study provides further knowledge about the experiences of OV in participating in CaI. The experience of participating in CaI is associated with all the occupational value dimensions in the ValMO-triad and most of the participants experienced a high level of OV both at M1 and M2. The study with one exception did not show that the experiences of OV in doing CaI changed during the study period. The role of CaI in mental health recovery processes is discussed as the experienced OV while participating in CaI resembles important elements in relation to facilitating recovery.

The results should be considered from at least two perspectives; the individual and those providing CaI. First, individuals enrolled in mental health services should know that participating in CaI may, even for a short period, contribute to a better subjective health experience and generate positive expectations of being able to perform necessary activities in everyday life and may generate experiences of OV and strengthen recovery. Second, the knowledge base of OV dimensions associated with creative activities provides occupational therapists with a basis for identifying and developing interventions that may facilitate recovery processes for people with mental illness.

Key findings

Doing creative activities as intervention enables a high degree of experienced OV

Doing creative activities as intervention is associated with all dimensions in the OV triad

The OV-triad terminology may serve to ensure that participating in certain CaIs, facilitates recovery.

This submission makes an original and substantial contribution to new knowledge about creative activities used as intervention enabling a high degree of experienced occupational value and thereby supporting mental health recovery.

Ethical approval

The research project was approved for health science research in Region Zealand (REG-201-2017) by the Danish Data Protection Agency. The study complies with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration II (General Assembly of the World Medical Association, Citation2014).

Author contributions

All authors collaborated in designing the study and the qualitative analysis. The first and third authors were responsible for the data collection. The quantitative analysis was performed by the first and last author, and all the authors contributed in varying degrees to the writing of the article.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to patients and users, the research group, and staff in the workshops, who took the initiative for the study brought about by a desire and a need to gain more evidence about the use of CaI in mental health recovery.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Occupational Therapy Association. (2014). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68(Supplement_1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2014.682006

- Billock, C. (2013). Personal values, beliefs, and spirituality. In B. A. Schell, G. Gillen, M. Scaffa, & E. S. Cohn (Eds.), Willard and Spackman’s occupational therapy (13th ed., pp. 310–318). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Bradbury-Huang, H. (2010). What is good action research? Why the resurgent interest? Action Research, 8(1), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750310362435

- Caddy, L., Crawford, F., & Page, A. C. (2012). ‘Painting a path to wellness’: Correlations between participating in a creative activity group and improved measured mental health outcome. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 19(4), 327–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01785.x

- Cordingley, K., & Pell, H. (2014). Life skills. In W. Bryant, K. Bannigan, J. Fieldhouse, J. Creek, & L. Lougher (Eds.), Chreek’s occupational therapy and mental health (5th ed., p. 502). Churchill Livingstone.

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2017). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage Publications.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Living well: The psychology of everyday life. Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Eklund, M., Erlandsson, L.-K., & Leufstadius, C. (2010). Time use in relation to valued and satisfying occupations among people with persistent mental illness: Exploring occupational balance? Journal of Occupational Science, 17(4), 231–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2010.9686700

- Eklund, M., Erlandsson, L.-K., Persson, D., & Hagell, P. (2009). Rasch analysis of an instrument for measuring occupational value: Implications for theory and practice. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 16(2), 118–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038120802596253

- Erlandsson, L. K., Eklund, M., & Persson, D. (2011). Occupational value and relationships to meaning and health: Elaborations of the ValMO-model. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 18(1), 72–80. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038121003671619

- Erlandsson, L.-K., & Persson, D. (2020). ValMO-Modellen – Occupational therapy for a healthy life by doing (2nd ed.). Studentlitteratur AB.

- Gunnarsson, A. B., & Björklund, A. (2013). Sustainable enhancement in clients who perceive the tree theme Method(®) as a positive intervention in psychosocial occupational therapy. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 60(3), 154–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12034

- Hagquist, C., Bruce, M., & Gustavsson, J. P. (2009). Using the Rasch model in nursing research: An introduction and illustrative example. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(3), 380–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.10.007

- Hansen, A. Ø., Boll, M., Skaarup, L., Hansen, T., Dür, M., Stamm, T., & Kristensen, H. K. (2020). A concept analysis of creative activities as intervention in occupational therapy. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 28(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2020.1775884

- Hansson, S. O., Björklund Carlstedt, A., & Morville, A.-L. (2022). Occupational identity in occupational therapy: A concept analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 29(3), 198–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2021.1948608

- Hickey, R. (2016). An exploration into occupational therapists’ use of creativity within psychiatric intensive care units. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 12(2), 89–107. https://doi.org/10.20299/jpi.2016.011

- Hocking, C. S., Smythe, L. A., & Sutton, D. J. (2012). A phenomenological study of occupational engagement in recovery from mental illness. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 79(3), 142–150. https://doi.org/10.2182/cjot.2012.79.3.3

- Horghagen, S., Fostvedt, B., & Alsaker, S. (2014). Craft activities in groups at meeting places: supporting mental health users' everyday occupations. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 21(2), 145–152. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2013.866691

- Hsieh, D. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288.

- Ismail, N., Kinchin, G., & Edwards, J.-A. (2017). Pilot study, does It really matter? Learning lessons from conducting a pilot study for a qualitative PhD thesis. International Journal of Social Science Research, 6(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijssr.v6i1.11720

- Kielhofner, G. (2008). Model of human occupation: Theory and application. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Leamy, M., Bird, V., Boutillier, C. L., Williams, J., & Slade, M. (2011). Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: systematic review and narrative synthesis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(6), 445–452. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083733

- Leckey, J. (2011). The therapeutic effectiveness of creative activities on mental well-being: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 18(6), 501–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01693.x

- Lloyd, C., Wong, S. R., & Petchkovsky, L. (2007). Art and recovery in mental health: A qualitative investigation. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 70(5), 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802260707000505

- Perruzza, N., & Kinsella, E. A. (2010). Creative arts occupations in therapeutic practice: A review of the literature. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(6), 261–268. https://doi.org/10.4276/030802210X12759925468943

- Persson, D., & Erlandsson, L.-K. (2010). Evaluating OVal-9, an instrument for detecting experiences of value in daily occupations. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 26(1), 32–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/01642120903515284

- Persson, D., Erlandsson, L. K., Eklund, M., & Iwarsson, S. (2001). Value dimensions, meaning, and complexity in human occupation – A tentative structure for analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 8(1), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/110381201300078447

- Reynolds, F. (2000). Managing depression through needlecraft creative activities: A qualitative study. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 27(2), 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-4556(99)00033-7

- Saavedra, J., Pérez, E., Crawford, P., & Arias, S. (2018). Recovery and creative practices in people with severe mental illness: evaluating well-being and social inclusion. Disability and Rehabilitation, 40(8), 905–911. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1278797

- Schmid, T. (2005). Promoting health through creativity: For professionals in health, arts and education. John Wiley & Sons.

- Stickley, T., Wright, N., & Slade, M. (2018). The art of recovery: outcomes from participatory arts activities for people using mental health services. Journal of Mental Health, 27(4), 367–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2018.1437609

- Townsend, E. A. (2012). Boundaries and bridges to adult mental health: Critical occupational and capabilities perspectives of justice. Journal of Occupational Science, 19(1), 8–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2011.639723

- Wagman, P., Håkansson, C., & Björklund, A. (2012). Occupational balance as used in occupational therapy: A concept analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 19(4), 322–327. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2011.596219

- Walters, J. H., Sherwood, W., & Mason, H. (2014). Creative activities. In W. Bryant, J. Fieldhouse, K. Bannigan, J. Creek, & L. Lougher (Eds.), Creek’s occupational therapy and mental health (pp. 260–275). Churchill Livingstone.

- Wilcock, A. A. (2002). Reflections on doing, being and becoming. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 46(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1630.1999.00174.x

- World Health Organization. (1992). International classification of diseases: Diagnostic criteria for research.

- World Medical Association. (2014). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. The Journal of the American College of Dentists, 81(3), 14–18.