Abstract

Peer support is one of the pillars of the recovery model in mental health care. The purpose is to specify the interventions performed by peer support workers (PSWs) and identify the outcomes in terms of the occupational therapy (OT) process with statistical incidence. A systematic review of the peer-to-peer technique in OT was carried out using the PRISMA guidelines and searching scientific databases. The results were ordered according to the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework-4, finding significant positive results in 7 of the 10 outcome categories. PSWs can be essential partners in achieving the goals of the OT program.

Introduction

What is peer to peer? Essential personal recovery model tool

Peer-to-peer interventions with people with severe mental health illness (SMI) are an essential tool in the recovery process. Peer support was gradually introduced in the 1990s as part of the move to increase the engagement of users of mental health services (Repper & Carter, Citation2011) that began in the 1970s, influenced by the philosophy of the Oxford Group (Dewhurst et al., Citation1974). People who have experienced mental health problems but are now stable are in a privileged position to help in the recovery of others who are trying to overcome similar situations (Davidson et al., Citation2012). Peer support is based on the personal recovery model rather than on psychiatric diagnosis criteria (Jewell et al., Citation2006). In fact, although peer support workers (henceforth, PSWs) are sometimes part of interdisciplinary mental health teams, they are not technically team members because their role is as a peer supporting a peer, sharing their personal experience without making interventions framed inside the role of physician, psychologist or occupational therapist (Silver & Nemec, Citation2016). PSWs approach the task from another paradigm which is based on mutual help between peers; by helping others, they also help themselves. The so-called “personal” recovery, complementary to clinical and social recovery, is based on a process of positive adaptation to the disease and disability, seeking to create the conditions for attaining an adequate level of personal well-being beyond the limitations that the disease can cause (Kuhn et al., Citation2015). This model usually incorporates trained peers who perform various non-medical tasks seeking to promote empowerment and generate hope and optimism – variables that have been shown to be engines of change and well-being (Bellamy et al., Citation2017; Davidson et al., Citation2012; Pickett et al., Citation2010).

Peer support workers play a number of key roles in the recovery process: a) collaborate with their partner to empower them to direct their own treatment and recovery; b) act as connectors with family, friends and the general population to support socialization; c) help their partner to improve their proficiency in everyday activities; and d) act as connectors with the health team to support their peer’s recovery by making their demands more audible and visible (Mead et al., Citation2001).

Historical background: Pinel's moral treatment

The historical antecedents of peer-to-peer interventions go back to the 18th - 19th century with Philippe Pinel, who is considered the father of moral treatment in helping people with mental health problems. His main goal was participation in tasks and activities of daily life with the aim of improving social functioning (Pelletier et al., Citation2015). In turn, his figure is closely related to occupational therapy due to his interest in the occupation as therapeutic means (Peloquin, Citation1989). His holistic and strongly humanistic vision of the person, the restoration of the communication with the patient, the study of his history, respect for the patient's areas of interest and the importance given to the environment make "their moral treatment" a close approach to the current paradigm of occupational therapy. In addition, we can consider Pinel as one of the pioneers in recruiting people in recovery to help others who suffer from a mental health problem (Davidson et al., Citation2012).

Meaningful occupation, a pillar in the personal recovery model

There is a general consensus about the components of a “good recovery”, including the search for hope, optimism about the future, the restoration of a positive identity over the damaged identity, and the development of a sense of empowerment in the context of the disease (Repper & Carter, Citation2011). Several researchers and academics have shown that the PSWs approach is ideal for developing these facets, due to their direct experiences of disability (Campos et al., Citation2014), and coping with stigma and achieving restoration (Davidson et al., Citation2006; Flanagan et al., Citation2016). Restored peers quickly create a relationship of empathy that encourages patients to recover hope and optimism and creates the optimal conditions for achieving more ambitious goals (Dahl et al., Citation2015; Sells et al., Citation2008).

One of the most transcendental people within the discipline of occupational therapy was Adolf Meyer. He was one of the forerunners of the occupational paradigm, occupations that provide a feeling of interest, worth, achievement, and challenge. Meyer stressed the importance of interpersonal relationships between professional and patient as an essential element in the construction of meaningful occupations (Meyer, Citation1922), which lends support to the importance of the concept of peer-to-peer programs in mental health. These concepts are closely linked to the idea of meaning of Vicktor Frankl (father of logotherapy), where the logotherapy shows that the fundamental motivation of every person is the search for meaning for their own life, in each concrete moment and particular and unique situation, in which their existence is found (Parker, Citation2021). To be human means to be living “the tension established between reality and the ideals to be materialized” (Frankl, Citation1959, p. 58). The essence of PSWs interventions is in line with the current paradigm of occupational therapy. Mary Reilly (Citation1962) questioned the principles used until the 1960s and recovered a holistic approach with the occupation as the center of the intervention, giving the service user an active role in his recovery.

Occupational therapists seek to improve the health and well-being of a person from a holistic point of view, including the physical, cognitive, psychological and spiritual aspects through the involvement of people in meaningful occupations. The spirituality of the person can be expressed in different forms and actions, which allow him to connect with himself and with his environment (Humbert, Citation2016).

Connection of occupational therapy with the personal recovery model

Occupational therapy can provide importance guidance to individuals providing peer support for many reasons. Because the profession values employment as an indispensable, integral part of people's health and well-being occupational therapists can advocate for the value of peer support for the worker as well as the service recipient. The offer of a job for the PSWs may be even more important than the clinical component of the intervention (Kielhofner, Citation2009; Wilcock, Citation2006). Something indispensable for the success of the PSWs system is the professional’s engagement with the PSWs where s/he must accompany the PSWs in the search for occupational interests and roles, and must help them to design/find a balance between their caretaking occupations and the others that make up their occupational identity (Jones et al., Citation2013). Unlike other health care professions, occupational therapy can play a fundamental role in the design of the intervention, thanks to its ability to analyze the occupation and provide the other with an occupational balance between self-maintenance, productivity and leisure occupations (Wilcock, Citation2006). The ultimate goal is for the PSWs to find well-being in their occupational development and thus avoid occupational imbalances, with the corresponding loss of quality of life (Repper & Carter, Citation2011). All human beings have the need (and the right) to control their lives and make changes if necessary. Occupational therapists view the process to control one’s life as a symptom of health and well-being. (Townsend & Polatajko, Citation2013).

Examples of peer programs in mental health from occupational therapy

An example of occupational therapy’s contribution to a peer support program is Careers Offering Peers Early Support (COPES), a program developed in Victory (Australia) in which occupational therapy has played an essential role in its design and implementation: “The COPES service employs carers, defined as people who provide personal care, support and assistance to another individual in need of support due to a mental illness.” (Bourke et al., Citation2015, p. 300). COPES is built from four key concepts: (1) Person-centered strength based approach (Wilcock, Citation2006; Townsend & Polatajko, Citation2013); (2) Rights based framework (Hammell, Citation2017); (3) Working in partnerships as enablers (Fransen et al., Citation2015); (4) Detailed occupational analysis.

Other examples of implemented peer-to-peer programs for mental health services that utilized occupational therapy principles are found in the UK and Hong Kong. Wolfendale and Musaabi (Citation2017) designed and implemented a peer-to-peer program in high security forensic services and studied it using qualitative research. They used meaningful occupation as a means with the goal of (1) increasing people's confidence; (2) develop communication and social interaction skills; (3) increase protective factors; (4) and realign the will toward more prosocial interests, beliefs, goals, occupations, and choices. The PSWs was the link between the person and the objectives set in the occupational therapy service. The occupational therapist supervised and followed up on the evolution of the intervention. In Hong Kong, Yam et al. (Citation2018) carried out a peer intervention, designing a training program (15 sessions) and a 50-hour practicum, to measure (longitudinal study without control group) the impact of the program on awareness of recovery progress, occupational competence, and problem-solving skills. The role of occupational therapy was present in the design and implementation of the program, selection of participants, and evaluation.

Previous systematic reviews

Over the years and to date we have found 11 published reviews focused on studying the benefits of peer-to-peer interventions: the first one from 1999 (Davidson et al., Citation1999) and the last from 2016 (Stubbs et al., Citation2016). Among them, we have highlighted the reviews carried out by Simpson (Simpson & House, Citation2002) and Lloyd-Evans (Citation2014), where a global review of peer support with people with severe mental illness (SMI) was conducted. In the last 6 years, there has been a growing interest in implementing peer interventions in different mental health services. For this reason, we believe a systematic review that collects the interventions carried out, the results achieved and the impact on the participants is called for. In addition, the review incorporates an analysis carried out according to the standards of evidence developed in evidence-based medicine (Sackett, Citation1989).

Aims of study

The objective of this review is to broaden our knowledge of the peer-to-peer technique in occupational therapy by exploring: (1) the interventions performed by the PSWs, (2) the results achieved, (3) the impact on service users and (4) the influence of occupational therapy. Simultaneously, the results will be grouped according to the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework-4 (OTPF–4): Domain and process (American Occupational Therapy Association, Citation2020b), taking advantage of the discussion to reflect on the relationship between peer support and occupational therapy. Ethical approval was not required for this study.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

The criteria for inclusion of articles were (a) published from January 1990 to July 2019; (b) written in English; (c) published online and with full text available because this was what was available to the authors; (d) comparison between experimental group (PSWs intervention) and control group (standard intervention); (e) age of participants between 18 and 65 years old; (f) diagnosis of severe mental disorders; (g) occupational therapy interventions.

Types of outcome domains

The outcomes are of the occupational therapy process analyzed in the review were those listed in OTPF-4, specifically the following: Occupational performance; Prevention; Health and wellness; Quality of life; Participation; Well-being; Occupational justice. The process that gave rise to the outcome domains described above consisted of an analysis of previous systematic reviews to detect in which areas the intervention had significant results. The challenge was (1) how we could analyze the statistical incidence of PSWs interventions from the point of view of occupational therapy; and (2) fit the outcomes domains described in OTPF-4 from the paradigm of the personal recovery model. All the variables described are found in the articles; the grouping in the seven categories was done later.

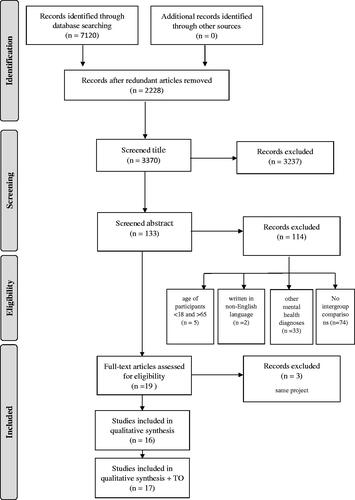

Search strategy

The search, selection and critical evaluation of relevant studies were carried out considering the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (Liberati et al., Citation2009).

The data search was carried out through the MEDLINE, Web of Science, Scopus and Cochrane Library computer databases. Two search strategies were used and combined in the final analysis (view Supplementary material 1):

((“mental health”) OR (“mental illness”)) AND ((((“peer support”) OR (“peer to peer”)) OR (“peer?led”)) OR (“consumers”));

(((“mental health”) OR (“mental illness”)) AND (((“mental health”) OR (“mental illness”)) AND ((((“peer support”) OR (“peer to peer”)) OR (“peer?led”)) OR (“consumers”)))) AND (“occupational therapy”).

The references included in the references of the most relevant articles were also searched.

Assessment of bias

The risk of bias in each article was assessed following the protocol set out in the Cochrane guide (Higgins et al., Citation2011).

Data management

Using Microsoft Excel (v.18.11), we developed a data extraction form to record the following information: study design; sample country; sample size, age, ethnicity, and inclusion criteria; description of the experimental intervention and control group; outcome measures; and results. Three independent evaluators, between them two occupational therapists, extracted data using identical forms. After data extraction, we compared the information entered and resolved any conflicts through discussion and consensus.

From each of the articles the following information was also obtained: (1) year of publication (in order to trace the use of the technique chronologically); (2) sample size, to assess the representativeness; (3) type of study design and evaluation of the instruments and results.

Analysis

The studies were carefully analyzed and classified in accordance with the AOTA guidelines developed in conjunction with the US Preventive Services Task Force (American Occupational Therapy Association, Citation2020a) as: strong: the results were obtained from well-conducted studies, usually two or more RCTs; moderate: the results were obtained from well-designed RCTs or multiple Level II or III studies; the available evidence is sufficient to determine health outcomes, but confidence in the evidence is constrained by factors such as the number, size, or quality of individual studies or by inconsistency of findings across individual studies; Low: low-level studies, with defects and inconsistencies in the findings; the available evidence is insufficient to assess effects on health and other outcomes of relevance to occupational therapy with confidence.

Results

Two searching strategies were used to combine occupational therapy studies with an earlier search that did not include occupational therapy as a variable. 7120 articles were found (search 1) and 189 (search 2).

3370 articles were reviewed after elimination of duplicates. 2228 articles were excluded after reviewing the title. 1142 abstracts were checked, of which 19 were selected for total reading. Finally, 16 articles were selected for the final analysis.

130 articles were reviewed after elimination of duplicates. 61 articles were excluded after reviewing the title. 69 articles were checked, 10 of which were selected for full reading. Finally, 1 article met the inclusion criteria and was included in the final analysis.

Ultimately, 17 articles were selected for their final review. A flow diagram in shows the study selection process.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of article inclusion and exclusion process. From: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(6): e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

The review collected relevant information from each article, including type of study, objective, number of participants, evaluation tools used, methodology, and results/conclusions.

Characteristics of the studies included

The recognition and subsequent screening process was completed in 17 studies. All were studies with two groups (experimental and control) published between 2005 and 2018 which met the inclusion criteria described above.

All the studies but one (Weissman et al., Citation2005) were RCTs.

The sample size ranged from 32 to 441, and ages from 39 to 57 years.

With regard to gender, the presence of women ranged from 5.4% (Resnick & Rosenheck, Citation2010) to 66% (van Gestel-Timmermans et al., Citation2012). Women were represented in all studies but one (Weissman et al., Citation2005). One study did not provide data on age and gender (Yamaguchi et al., Citation2017).

With regard to the origin of the studies, in agreement with Puschner et al., (Citation2019) most interventions between peers were found in English-speaking countries. Of the 17 studies selected for analysis, only four were carried out outside the US: one each in the UK (Johnson et al., Citation2018), the Netherlands (van Gestel-Timmermans et al., Citation2012), Canada (Wrobleski et al., Citation2015) and Japan (Yamaguchi et al., Citation2017).

The participation of occupational therapy in the studies has been analyzed. Despite carrying out a specific search, only one project (comparison of groups) with the presence of occupational therapists was detected (Wrobleski et al., Citation2015).

The inclusion criteria ensured that participants had a SMI, the main requirement of the review. The most common diagnoses were schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, psychotic disorder not otherwise specified, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. The 17 studies also incorporated new disorders: for example, in the already mentioned criterion of a person with a diagnosis of mental health in the process of personal recovery, two studies (Druss et al., Citation2018; Muralidharan et al., Citation2019) added as an inclusion criterion one or more diagnoses of physical diseases; drug addiction (Jewell et al., Citation2006); homelessness (Weissman et al., Citation2005); and criminal record (Rowe et al., Citation2007). All the studies mentioned have been added to the review ().

Table 1. Summary of fIndings.

Risk of bias

Following the protocol established by the Cochrane guide, all the studies analyzed present a correct explanation for the generation of random sequence. Eight studies had allocation concealment problems: they did not clearly describe the random selection process. In none of the interventions were differences found between groups. Regarding the blinding of the participants and the personnel involved in the studies, all studies show a risk of bias due to the need for informed consent. Eight of the 17 studies present a low risk of detection bias: PSWs and client are aware of the intervention. Many of the articles included were deficient in attrition bias: systematic differences between groups in withdrawals from a study; in six of them it is not clear how the problem was solved and only in one of them was it omitted. Finally, only two cases of reporting bias were observed: systematic differences between reported and unreported findings ().

Table 2. Risk-of-Bias Table.

Quantitative data synthesis

The review detected the existence of two different types of peer intervention. The first group of studies framed their intervention as an education/training program in which peers acted as trainers taking advantage of their experience in mental suffering and in the recovery process, accompanying the person cared for in the search for their life plan. In the second group, the peer took on the role of case manager, a community companion for the vulnerable person providing support and hope. In both interventions, future peers were trained in issues of personal recovery, bonding, communicative skills, and topics specific to each program. Below, the results are shown by these two types of intervention, highlighting the statistically significant results.

Education programs

We found five articles that proposed a training intervention. Druss (Citation2018) obtained statistically significant results in health and wellness, presenting improvements in Physical Component Summary (p < 0.046) and Mental Component Summary (p < 0.039) of the SF-36; and occupational justice (mental health recovery – p < 0.02).

We also found a program of support workers carried out in the Netherlands (van Gestel-Timmermans et al., Citation2012) which focused its peer intervention on people diagnosed with mental health problems who had gone through periods of destabilization. The only criterion for participating was being in an advanced process of personal recovery. The study found significant improvements in occupational justice (Dutch Empowerment Scale, (p < 0.01), quality of life (HHI, (p < 0.01), and well-being (MHCS, (p < 0.01).

Similar to the Dutch study, all PSWs exercising a training role had previously participated in the BRIDGES project as trainees (Cook et al., Citation2012). The article presented statistically significant improvements in occupational justice (RAS, p 0.01) and quality of life (SHS, p < 0.01).

A program developed in the US, focusing on people with a diagnosis of comorbidity (Living Well, Muralidharan, et al., Citation2019), achieved a positive impact on the beneficiaries with significant improvements in quality of life (SF-12, p < 0.032; Self-management Self-Efficacy Scale, (p < 0.001); occupational performance (PAM, p < 0.038; MHLCS (p < 0.045); IMSM (physical, p < 0.011; relationship, 0.015).

Finally, another article presented an educational program (Resnick & Rosenheck, Citation2010) facilitated by PSWs. The intervention recorded statistically significant results (correlations) in occupational performance (Activities of Daily Living Scale, p < 0.03); occupational justice (recovery attitude scale, p < 0.03; and empowerment p < 0.04).

Case management

The review found ten studies in which PSWs played a case manager role. The only prospective case-control study (Weissman et al., Citation2005) did not present any statistically significant differences in any of the variables studied. The study by Johnson et al. (Citation2018) reported a project developed by the National Health Service (NHS) focusing on people with SMI who had suffered a recent crisis. The researchers only found a significant improvement in prevention, specifically in the satisfaction with respect to mental health services (p < 0.001). Jewell et al. (Citation2006) described a program developed by members of the Yale Program on Recovery and Community Health research team, who obtained statistically significant post-intervention improvements in occupational performance at 6 months (BLRI: positive regard p < 0.05 and unconditionality, p < 0.05); at 12 months (ASI, positive regard, p < 0.01) empathy, p < 0.04 – unconditionality, p < 0.02).

Rogers et al. (Citation2016) compared two interventions developed by first-person agents: an experimental individualized intervention (one-on-one), and a control group which underwent a standard peer-run-agency intervention. The program showed significant improvements in two of the outcomes studied: quality of life (BQOL, p < 0.05) and health and wellness (BASIS-24, p < 0.05). A study in Japan (Yamaguchi et al., Citation2017), the only one carried out in a hospital setting, assessed the impact of a 6-month peer-led intervention on shared decision making. Significant differences were found in four variables with respect to the control group: occupational performance (quality of the clinical decision in a medical visit, SDM-18 – p < 0.001); the patient-doctor relationship, IPC communication – p < 0.01); patient-doctor relationship, STAR-Patient – p < 0.02); and health and wellness (medication side effects, DIEPSS – p < 0.02). Corrigan et al., (Citation2018) adapted an PSW program taking into account the cultural origin of the population served. The program offered significant improvements with respect to the control group: improvements in the perception of quality of life, QLS (p < 0.01); occupational justice (Empowerment Scale – p < 0.05; perception of the recovery process, RAS – p < 0.01).

Kelly et al. (Citation2017) analyzed a recent project based on the BRIDGES program, a peer intervention featuring a case manager figure to promote healthy roles and habits. The program presented statistically significant results, greater improvements in prevention were observed: access and use of primary care health services – p < 0.012; decreased preference for emergency care, p < 0.015; increased preference for primary care clinics, p < 0.001; increased satisfaction with care received on the Healthcare Provider Scale, p < 0.019); improvements in health and wellness: improved detection of chronic health conditions (SF-12, p < 0.048); reductions in pain (SF-12, p < 0.031); and a greater perception of well-being, specifically in consumer confidence in self-management of health care (MHCS, p < 0.009).

Mahlke et al. (Citation2017) is a PSWs program developed in Germany: a 192-hour training part in which PSWs shared training with healthcare professionals (the course was taught in the first-person), and a practical part (two months) where they joined the work teams in developing the role of case manager. The program obtained statistically significant results in terms of an improved perception of health and wellness with respect to the control group (EQ5D, p < 0.004). The two people who developed the role of case manager were paid €450 per month. The last of these studies, Sledge et al. (Citation2011) presents another project in which the PSWs had a formal contract. The program had a very positive impact, showing statistically significant differences with respect to the control group in prevention, with reductions in rehospitalizations (p < 0.042) and hospital days (p < 0.03).

A case manager program promoted from an occupational therapy service in Canada (Wrobleski et al., Citation2015) met the criteria for inclusion in this systematic review. The project designed an RCT comparing a standard intervention (occupational therapy with the support of a mental health worker – MHW)) with a peer intervention (occupational therapy with the support of a peer worker – PW). Both the MHW and PW offer individual assistance following the objectives established in the occupational therapy service. The role of the therapist in the project has been essential: design of the program, selection of participants according to the person's abilities, and monitoring of the PSWs during the intervention. Wrobleski et al. found significant improvements in quality of life (Quality of Life Interview, p < 0.05).

Training program + case management

Rowe et al. (Citation2007) tested the efficiency of peer programs by measuring their impact on crime and drug addiction. The project consisted of a training phase for project beneficiaries on issues of social inclusion, community participation, and construction of a work plan. The program presented a significant impact on the participants in the experimental group, observing improvements in occupational performance: low levels of alcohol consumption at follow-up periods between 6 and 12 months (ASI, p < 0.005), decreased non-alcohol drug use in all periods in both groups (ASI, p < 0.05); and a significant impact on prevention: reduced criminal justice charges over all periods evaluated in both groups (p < 0.05). The study by Chinman et al. (Citation2015) shows us another example of training (training modules) and provision of mutual support services. The peer workers received 30-hour training, recognized by the US health system, organized in different modules: recovery, social interaction skills and psychosocial rehabilitation; and intensive training (two days) in disease management. The responsible professional supervises the intervention with the peer worker on a weekly basis. The tasks once incorporated into the teams are grouped into occupational performance (Health management) and occupational justice (recovery plans). Significant improvements in occupational performance were observed in the intervention between equals (PAM, p < 0.005) compared to the control group. Additional analyzes observed significant improvements in both groups in health and wellness measures (BASIS-R, p < 0.02), and occupational justice (MHRM, p < 0.01).

Discussion

This review aims to add to the body of knowledge on the participation of peer support workers in mental health work teams, with special emphasis on occupational therapy services. One important aspect that the review has highlighted is the setting in which these projects have been implemented. The presence of studies in other countries besides the United States such as Japan, the Netherlands, the UK, Canada and Germany bears witness to the expansion of the practice in the wider world. People with experience in mental health can be an important asset for others who are in the midst of personal recovery.

Peer interventions and their relationship with outcomes of the occupational therapy process

The results were arranged following the guidelines of Occupational Therapy Practice Framework-4 (OTPF-4): Domain and process (AOTA, Citation2020b). The results show a positive impact on the following outcome measures: Occupational performance; Prevention; Health and wellness; Quality of life; Occupational justice ().

Table 3. Outcome Measures with Statistical Value Grouped by Outcome Domains According to Occupational Therapy Practice Framework Outcome Domains.

Occupational performance

Occupational performance is the dynamic interaction between the person, the context or environment and the activity. This interaction has the potential to improve the skills and patterns in the occupational performance of the participants, favoring participation in meaningful occupations and activities (adapted in part from Law et al. (Citation1996)). We have grouped the outcome measures with statistical impact that influence the therapeutic relationship and client satisfaction. Occupational therapists know the importance of building a positive bond with the person as a necessary part of the intervention (Meyer, Citation1922). This positive relationship has been identified as an essential element by clients (Cole & McLean, Citation2003). We found different outcome measures with statistical incidence after peer intervention in the study by Yamaguchi (Citation2017): IPC (Stewart et al., Citation2007) and Star-Patient (McGuire-Snieckus et al., Citation2007). In turn, Johnson et al. (Citation2018) measures the satisfaction of the participants using the Customer Satisfaction Questionnaire (Attkisson & Zwick, Citation1982). Kelly et al. (Citation2017) measured the impact of the relationship between client and professional using the Healthcare Provide Scale (Bakken et al., Citation2000). The reason for grouping them in this category is the relationship between occupation, health and well-being (WFOT, Citation2012b, p. 2) in which the therapeutic relationship is the central element to promote changes. As can be seen, PSWs interventions are capable of influencing the therapeutic relationship.

Continuing with the outcome measures, an area of special relevance for the discipline of occupational therapy is the activities of daily living (ADLs): activities oriented toward taking care of one's own body and completed on a routine basis (adapted from Rogers et al., Citation1994). These activities are “fundamental to living in a social world; they enable basic survival and well-being (Christiansen & Hammecker, Citation2001, p. 156). Among the studies analyzed, Resnick & Rosenheck (Citation2010) obtained significant values in this area by means of Activities of Daily Living Scale (Cuffel et al., Citation1997). Finally, three selected studies have focused their intervention on an occupation of special relevance for the well-being of clients: Health Management. Occupation focused on developing, managing, and maintaining routines for health and wellness by engaging in self-care with the goal of improving or maintaining health, including self-management, to allow for participation in other occupations (American Occupational Therapy Association, Citation2020a). Yamaguchi et al. (Citation2017) focused on client participation in their treatment (Shared Decision-Making) and obtained benefits in Scale to Assess Therapeutic Relationships in Community Mental Health Care (McGuire-Snieckus et al., Citation2007).

Prevention

The results measure the impact of health education or promotion efforts designed to identify, reduce, or prevent the occurrence and decrease the incidence of unhealthy conditions, risk factors, diseases, or injuries (American Occupational Therapy Association, Citation2020c). The use and/or assistance of medical services would fall into this category (Kelly et al., Citation2017; Sledge et al., Citation2011). We consider that they are a way of measuring the impact of health promotion programs within the occupational therapy services. In this grouping we have included the criminal charge (Rowe et al., Citation2007), understanding it as an opportunity for occupational therapists to promote and reduce risky behaviors.

Health & wellness

In this section we have grouped the outcome measures that are related to client factors, bodily functions, specifically clinical symptomatology. According to the WHO (1985), health is a state of physical, mental, and social well-being, as well as a positive concept that emphasizes social and personal resources and physical capacities. In our review, the instrument most often used has been the Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale (Eisen et al., Citation2004), which has captured statistical improvements in peer intervention in three studies (Chinman et al. (Citation2015); Muralidharan et al. (Citation2019); Rogers et al. (Citation2016). The 24-item Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale, BASIS-24 is a leading tool for assessing mental health treatment outcome from client perspective. Following the line of measurement of clinical aspects, we found the Drug-induced Extrapyramidal Symptoms Scale (Inada & Yagi, Citation1995) used by Yamaguchi et al. (Citation2017). Finally, we have included an instrument used by Rowe et al. Alabama. (2017), Addiction Severity Index, a measure that assesses the severity of addiction (McLellan et al., Citation1980). The factors of the person influence the performance of the occupation (American Occupational Therapy Association, Citation2020b) and therefore must be taken into account when designing the intervention.

Quality of life

According to Radomski (Citation1995) it is a dynamic appraisal of the client's life satisfaction (perceptions of progress toward goals), hope (real or perceived belief that one can move toward a goal through selected pathways), self-concept (composite of beliefs and feelings about oneself), health and functioning. “Occupational therapy practitioners develop and implement occupation-based health approaches to enhance occupational performance and participation, quality of life, and occupational justice for populations" (American Occupational Therapy Association, Citation2020b, p. 3). Peer interventions have shown significant improvements in these outcomes, evaluated by different instruments (). Three studies have obtained an impact on quality of life through the Quality-of-Life Interview – Brief Version (Lehman, Citation1996) and among them one with the participation of occupational therapy (Wrobleski et al., Citation2015). Chinman et al. (Citation2015) and Muralidharan et al. (Citation2019) have shown significant improvements in the Patient Activation Measure (Green et al., Citation2010), scale determining patient engagement in healthcare. Another instrument that assesses the perception of self-efficacy is the Self-management Self-Efficacy Scale (Lorig et al., Citation1996). Another important group is in the subjective perception of the state of health, in four selected studies they have found significant changes (Druss et al., Citation2018; Kelly et al., Citation2017; Mahlke et al., Citation2017; Muralidharan et al., Citation2019) with different instruments: (Salyers et al., Citation2000); Short-form health survey-36 (McHorney et al., Citation1993) EuroQol questionnaire (EuroQolGroup, Citation1990). In this section and following Radomski's definition of quality of life, the review has included two studies in which the peer intervention shows a positive impact on hope. Cook and van Gestel-Timmermans in their respective studies measured hope through the State Hope Scale (Snyder et al., Citation1996) and Health Hope Index (Herth, Citation1992). In generating hope in clients, we find an intimate relationship between the recovery model and occupational therapy. Throughout the review we have commented that hope is a very important element in the personal recovery model (Davidson et al., Citation2012) but also for occupational therapists. Occupational therapy practitioners use professional reasoning to help clients make sense of the information they are receiving in the intervention process, discover meaning, and build hope (Taylor, Citation2019; Taylor & Van Puymbrouck, Citation2013).

Occupational justice

If we follow the WHO definition, participating is “Involvement in a life situation” (World Health Organization, Citation2001, p. 10). The AOTA goes one step further: “Engagement in desired occupations in ways that are personally satisfying and congruent with expectations within the culture” (American Occupational Therapy Association, Citation2020b, p. 67). In this section we will group the instruments used to measure personal recovery. From an occupational perspective, the subjective feeling of recovery fits us with the development of significant occupations: access to and participation in the full range of meaningful and enriching occupations afforded to others, including opportunities for social inclusion and resources to participate in occupations to satisfy personal, health, and societal needs (adapted from Townsend & Wilcock, Citation2004). Townsend & Wilcock's vision is complemented by the definition of personal recovery: process of positive adaptation to the disease and disability, seeking to create the conditions for attaining an adequate level of personal well-being beyond the limitations that the disease can cause (Kuhn, Bellinger, Stevens-Manser, & Kaufman, Citation2015). The main objective of both occupational therapy and the paradigm of personal recovery is to accompany the construction of a life project, through meaningful occupations in search of well-being of the person. We can find instruments to measure recovery such as Mental Health Recovery Measure (Bullock, Citation2005), Recovery Attitudes Questionnaire (Borkin et al., Citation2000), and the most widely used Recovery Assessment Scale (Corrigan et al., Citation1999); and personal empowerment using the Empowerment Scale (Rogers et al., Citation1997) and the Dutch Empowerment Scale (Boevink et al., Citation2009).

Peer interventions in mental health can be very supportive for therapists. The PSWs can be a link to achieve the objectives set from the service (Tse et al., Citation2012). PSWs can give continuity to the objectives set by the occupational therapy service and supervise the intervention.

Below we discuss the different inclusion criteria observed in the studies, the setting (community vs institutional), the methodologies used and the significance of the results taking into account the control groups.

Inclusion criteria

All 17 studies included people with SMI. However, some studies highlighted other criteria that should be taken into account in future interventions. Druss et al. (Citation2018) and Muralidharan et al. (Citation2019) which both described training programs, used the diagnosis of one or more chronic pathologies as inclusion criteria (chart diagnosis of a chronic respiratory or cardiovascular condition, diabetes, or arthritis). Two studies introduced drug consumption as a criterion (Jewell et al., Citation2006; Rowe et al., Citation2007). Rowe et al’s is particularly interesting, as it focuses on peer interventions with a clear vocation to solve social problems, incorporating a criminal record as a criterion. Continuing with interventions to solve specific social problems Weissman et al. (Citation2005) introduced homelessness as a criterion. Finally, Corrigan (Citation2018) designed a peer-to-peer cultural intervention which incorporated belonging to the same community as a criterion (a cultural approach). These results corroborate those reported in another study by the same author (Corrigan et al., Citation2017) which proposed a peer intervention with homeless African Americans with serious mental illness. In that study, the authors observed significant improvements in two of the areas included in the review (quality of life and recovery) in addition to physical health.

Community vs. institutional setting

Peer intervention is mostly practiced in community settings, away from the hospital environment. In Japan, however, it has been carried out in a hospital setting. Yamaguchi et al. adapted a peer-to-peer intervention in a medical setting in which PSWs accompanied the person being cared for in making decisions about their treatment. PSWs received specific training from the programmer and played a case manager role. They obtained significant results with respect to the control group in the therapeutic relationship, symptomatology, and service evaluation. The results were satisfactory and opened up the possibility of incorporating this model in clinical-hospital settings. However, no significant results were obtained in recovery variables (SISR), something that community programs have achieved. Thus, given their effectiveness in community programs, peer programs need to be promoted in psychiatric units in order to quantify their impact on the personal recovery of the person being cared for. A good example of this are the studies of Wolfendale and Musaabi (Citation2017), and Yam et al. (Citation2018), both with occupational therapists in the design and execution of the programs.

Clinical vs. recovery outcomes

Substantial progress has been made in new mental health intervention paradigms, and there is currently a consensus between all stakeholders that services need to be geared toward recovery (Slade et al., Citation2012)

A new paradigm of intervention with people with mental health problems is currently advancing, focused on personal recovery and on what is important to the person (Talbott, Citation2013). The current paradigm of occupational therapy is that of a person-centered care, understanding clients as “active participants” in a process which interacts with the environment (Schell & Gillen, Citation2019, p. 1194). Traditionally, interventions have focused on measuring clinical aspects such as symptoms, social disability, and use of the service (Thornicroft & Slade, Citation2014). A common feature of the PSWs system, on which all interventions (educational programs or case management) are focused, is its implementation in a climate of hope in which there is an exchange of the skills and strategies that are necessary on the path to recovery (Mead et al., Citation2001). We again find a connection with essential values of occupational therapy. The paradigm of personal recovery and occupational therapy focuses on aspects such as accompanying the person in a life full of meaning, in which spirituality and hope in the face of change are essential (Billock, Citation2005). In our review we observed ten studies which, in addition to considering traditional variables, have incorporated measures aimed at achieving recovery in mental health.

However, only six studies out of the 17 included obtained significant results. Four of these studies were training programs aimed at achieving personal recovery in people with mental health problems (Cook et al., Citation2012; Druss et al., Citation2018; Resnick & Rosenheck, Citation2010; van Gestel-Timmermans et al., Citation2012). These studies incorporated variables such as quality of life, self-efficacy, symptoms, use of services and recovery-oriented variables. Van Gestel-Timmermans recorded significant results in empowerment (Dutch Empowerment Scale), hope (HHI), and in the variable of self-efficacy (MHCS); Resnick & Rosenbeck obtained significant results in functioning (activities of daily living), recovery, general empowerment, and use of services; Cook, recovery (RAS) and hope (SHS); and Druss in operation (SF-36) and recovery (RAS). Two case management programs, with individual intervention, achieved a significant impact (Chinman et al., Citation2015; Corrigan et al., Citation2018). The intervention proposed by Chinman obtained significant results in symptoms (BASIS-24) and recovery (MHRM), while Corrigan’s program is relevant because it incorporated peer-to-peer interventions with people with mental health issues and from the same ethnic background and obtained positive results in all the variables studied: quality of life (QLS), recovery (RAS) and empowerment (Empowerment Scale).

On the other hand, there is a group of four studies which despite presenting outcome domains of recovery did not obtain significant results. Two were training programs (Johnson et al., Citation2018; Muralidharan et al., Citation2019) and two case management (Rogers et al., Citation2016; Yamaguchi et al., Citation2017). Johnson recorded significant results in the use of services and Muralidharan reported significant results in functioning (SF-12, Self-management Self-Efficacy Scale, Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Scale, IMSM and MHLCS), therapeutic relationship (PAM) and symptoms (BASIS-24). As for the case management programs, (Rogers et al., Citation2016) found significant results for symptoms (BASIS-24) and quality of life (BQOL).

Finally, six studies proposed their interventions without any recovery domain outcome (Jewell et al., Citation2006; Kelly et al., Citation2017; Mahlke et al., Citation2017; Rowe et al., Citation2007; Sledge et al., Citation2011; Weissman et al., Citation2005), including very specific programs to solve an occupational dysfunction. They assess the impact of the intervention on clinical symptomatology. On the one hand, Sledge proposed a peer-to-peer program to assess its impact on reducing hospitalizations and medical services, while Jewell’s and Rowe’s programs for reducing toxic substance use had a positive impact on reducing addictions. Jewell achieved significant results in the therapeutic relationship (BLRI), and Rowe significant improvements in toxic consumption (ASI). Similarly, Kelly proposed a peer intervention focused on the acquisition of habits and routines in the home, achieving significant results in the person’s ability to respond to specific health problems. Kelly pursues one of the essential objectives of occupational therapy: the autonomy of people in the performance of activities of daily life (American Occupational Therapy Association, Citation2020b). All these studies were designed on the basis of a case management intervention. On the other hand, the Mahlke project focused on personal recovery in the form of a training program and only had an impact on quality of life (EQ5D). We might wonder why they did not measure the impact on recovery. There are two possible reasons. The first could be the desire to address a specific problem such as drug use (Jewell et al., Citation2006; Rowe et al., Citation2007) and the level of medical care (Sledge et al., Citation2011). Both experiences are located in the USA with a widespread implementation of PSWs throughout the country. The second might be the need to generate evidence; these authors compared the impact of peer-to-peer programs and clinical impact assessments (Kelly et al., Citation2017; Mahlke et al., Citation2017; Weissman et al., Citation2005).

Impact achieved vs. control group

An element to highlight in the review is the nature of the control groups. In most cases the experimental intervention has been compared with a control group with standard interventions. In Johnson et al. (Citation2018) all participants received the same training except for peer support for the preparation of the recovery notebook, while in Rogers et al. (Citation2016) both groups received the same content except for the case management intervention which was applied only to the experimental group. This may complicate the task of finding significant differences given the high recovery load in the two groups.

Why implement PSWs interventions? The role of the occupational therapist

Occupational therapy offers a vision of the person focused on their strengths, observes the client in their daily routine and considers their cultural, institutional and social context (Townsend & Polatajko, Citation2013). Occupational therapy transmits this vision of PSWs in its interventions so that the person receiving care can develop their own potential (Townsend, Citation1993). As we have mentioned previously, occupational therapy has different theoretical frameworks that offer therapists occupational tools to observe, analyze and design meaningful occupations (Polatajko et al., Citation2004; Townsend & Polatajko, Citation2013). An indispensable component of a successful PSWs program is the clear definition of the PSWs tasks and roles, which will help mitigate their fear and inability to manage the system (Davidson et al., Citation2012; Repper & Carter, Citation2011). A good occupational screening will allow the creation of an environment of respect between the PSWs, clients and professionals to achieve a common goal for occupational therapy: it is to enjoy a life to the fullest and that everyone can contribute to society. It is not a static process, but a dynamic one between the person, the environment, and occupations. The person is connected with the environment, and from this interaction the occupation is born. The role of occupational therapy can be key to achieving a successful implementation of peer support programs as a discipline that: (1) fundamentally values and holds beliefs rooted in occupation (Cohn, Citation2019); (2) knowledge and experience in the therapeutic use of occupation (Gillen et al., Citation2019); (3) professional behaviors and dispositions (American Occupational Therapy Association, Citation2015d); (4) therapeutic use of self (Taylor, Citation2020). We can group the roles that the occupational therapist can contribute to peer support programs as follows:

Select and train program participants in interpersonal skills

Analyze the workplace to achieve optimal occupational performance

Accompany people in their recovery process, in the search for meaningful occupations

Supervise the intervention, guide the peers in the objectives set with the client; and make modifications if necessary

Limitations

One of the main limitations of the study lies in the very origin of the systematic review, since the search criteria themselves eliminate papers that do not meet the inclusion criteria. The inclusion solely of papers in English means that a considerable amount of research has been neglected, but this has been done to guarantee publications with a high impact. Regarding the articles based on occupational therapy, the fact of only including studies with a control group has led to the exclusion of interesting papers. One issue to consider is the impossibility of shielding the participants from the intervention. They all know their role in the project, and this can influence the results.

Comparison with earlier reviews

Six years ago, a systematic review (Stubbs et al., Citation2016) that focuses on the impact of peer interventions on physical health and lifestyle behaviors on people with SMI has been published. Although there is inconsistent evidence (sample size and little clarity of the contribution of the PSWs), they draw positive conclusions. The previous systematic review (all types of peer support) carried out an in-depth analysis of peer support, fulfilled in 2014 by Lloyd-Evans (Lloyd-Evans et al., Citation2014), recorded significant results yet not consistent enough to promote it to policy makers. As a complement to the Cochrane quality assessment, this review has used elements to quantify the levels of evidence and their strengths for promoting the practice. All the studies analyzed present a level of evidence above II, a fact that makes it possible to classify the peer interventions as strong evidence. It is true that this evidence is defined by the inclusion criteria, but since 2014 ten level I studies have been found. Like Lloyd-Evans, the risk-of-bias analysis shows certain inconsistencies which we believe are due to the nature of the practice itself: for example, the fact that the participants and the staff cannot be blinded. For this reason, we believe that there has been an evolution in the interventions in terms of rigor and quality.

Challenges for future interventions and research

The review has provided an in-depth analysis of peer interventions with people with health issues and has identified the occupational therapy domain outcomes in which there has been a significant impact. To continue advancing in its implementation, it is necessary to incorporate innovative aspects, one of which is to combine health (SMI) and origin (culture) to adjust to the new social reality of diversity. We have observed the community essence of peer-to-peer models, but programs are needed to measure its impact in hospital settings. In order to continue to demonstrate the need for peer programs in mental health intervention, RCT studies are needed in which the person is in a process of recovery marked by stability and a willingness to engage in the process. It is vitally important for future research to relate the peer interventions with the impact on the occupational performance of the PSWs. The need to build knowledge is a matter of social justice

Conclusions

This review aims to encourage occupational therapists to engage in the practice of peer-to-peer support and to try to apply it to their immediate environment. The bond that is generated between the worker and the client is enveloped in an atmosphere of hope that promotes recovery. The importance of this bond has been demonstrated by the significant improvements recorded in the therapeutic relationship. Peer interventions are an example of the trending change in outcome measures that follow the paradigm of the mental health recovery movement, promoting empowerment, offering hope, and favoring inclusion. PSWs are very important travel companions for the person in achieving the objectives set from the occupational therapy service. Its widespread use in community resources has been confirmed, but there is still room for it to be applied in hospital settings. For this, it is important to define the type of intervention (educational program, training program or case management) that PSWs will carry out among their peers. In all of them, the therapist will validate the objectives with the person, and the PSWs will accompany the client toward the goals set. In an educational program, the professional will develop the modules and accompany the person in achieving the objectives set. Instead, in a training program, the role of the therapist will be primarily to train in interpersonal skills. Finally, in a case management program, the main role of the occupational therapist will be to analyze the potential of the person and their motivations, align them with the needs of the services. This should allow a definition of their role and tasks, achieving a high level of inclusion in the services. For all of these reasons the presence of occupational therapy is so important.

Author contributions

All authors declare that is original work and that they meet the criteria for authorship. Ivan Cano designed the study, extracted the data, conducted the analyses, and wrote the manuscript. Gemma Prat and Salvador Simó conducted the analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (14.1 KB)Acknowledgments

Thanks to the Fundació Althaia-Xarxa Assistencial i Universitària de Manresa, MOSAIC Project and the University of Vic - Central University of Catalonia for offering us the time and space to write this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Occupational Therapy Association. (2015d). Standards of practice for occupational therapy. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 69(Suppl. 3), 6913410057. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2015.696S06

- American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020a). Guidelines for systematic reviews in American occupational therapy. American Occupational Therapy, (March), 1–11. https://research.aota.org/DocumentLibrary/AOTA%20SR%20instructions%20Dec2020.pdf

- American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020b). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(Suppl. 2), 7412410010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001

- American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020c). Occupational therapy in the promotion of health and well-being. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74, 7403420010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.743003

- Attkisson, C. C., & Zwick, R. (1982). The client satisfaction questionnaire. Psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Evaluation and Program Planning, 5(3), 233–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/0149-7189(82)90074-x.

- Bakken, S., Holzemer, W. L., Brown, M. A., Powell-Cope, G. M., Turner, J. G., Inouye, J., Nokes, K. M., & Corless, I. B. (2000). Relationships between perception of engagement with health care provider and demographic characteristics, health status, and adherence to therapeutic regimen in persons with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 14(4), 189–197. https://doi.org/10.1089/108729100317795

- Bellamy, C., Schmutte, T., & Davidson, L. (2017). An update on the growing evidence base for peer support. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 21(3), 161–167. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-03-2017-0014.

- Billock, C. (2005). Delving into the center: Women’s lived experience of spirituality through occupation (Publication No. AAT 3219812) [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Southern California. Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

- Boevink, W., Kroon, H., & Giesen, F. (2009). Empowerment: Constructie en validatie van een vragenlijst [Empowerment: Construction and Validation of a Questionnaire]. Trimbos Instituut. https://assets-sites.trimbos.nl/docs/f8879f61-6722-4682-9831-34ce9247b27c.pdf

- Borkin, J., Steffen, J., Ensfield, L., Krzton, K., Wishnick, H., Wilder, K., & Yangarber, N. (2000). Recovery attitudes Questionnaire: Development and evaluation. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 24(2), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0095112

- Bourke, C., Sanders, B., Allchin, B., Lentin, P., & Lang, S. (2015). Occupational therapy influence on a carer peer support model in a clinical mental health service. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 62(5), 299–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12235.

- Bullock, W. A. (2005). The Mental Health Recovery Measure. In T. Campbell- Orde, J. Chamberlin, J. Carpenter, & H. S. Leff (Eds.), Measuring the promise of recovery: A compendium of recovery measures (Volume II). The Evaluation Center@HSRI.

- Campos, F. A. L., de Sousa, A. R. P., Rodrigues, V. P. da C., Marques, A. J. P. da S., Dores, A. A. M. da R., & Queirós, C. M. L. (2014). Peer support for people with mental illness. Revista de Psiquiatria Clínica, 41(2), 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1590/0101-60830000000009.

- Chinman, M., Oberman, R. S., Hanusa, B. H., Cohen, A. N., Salyers, M. P., Twamley, E. W., & Young, A. S. (2015). A cluster randomized trial of adding peer specialists to intensive case management teams in the Veterans Health Administration. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 42(1), 109–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-013-9343-1.

- Christiansen, C. H., & Hammecker, C. L. (2001). Self care. In B. R. Bonder & M. B. Wagner (Eds.), Functional Performance in Older Adults (pp. 155–175). F. A. Davis.

- Cohn, E. S. (2019). Asserting our competence and affirming the value of occupation with confidence. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73, 7306150010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2019.736002

- Cole, B., & McLean, V. (2003). Therapeutic relationships redefined. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 19(2), 33–56. https://doi.org/10.1300/J004v19n02_03.

- Cook, J. A., Steigman, P., Pickett, S., Diehl, S., Fox, A., Shipley, P., MacFarlane, R., Grey, D. D., & Burke-Miller, J. K. (2012). Randomized controlled trial of peer-led recovery education using Building Recovery of Individual Dreams and Goals through Education and Support (BRIDGES). Schizophrenia Research, 136(1–3), 36–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2011.10.016.

- Corrigan, P. W., Giffort, D., Rashid, F., Leary, M., & Okeke, I. (1999). Recovery as a psycho-logical construct. Community Mental Health Journal, 35(3), 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018741302682.

- Corrigan, P. W., Kraus, D. J., Pickett, S. A., Schmidt, A., Stellon, E., Hantke, E., & Lara, J. L. (2017). Using peer navigators to address the integrated health care needs of homeless African Americans with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 68(3), 264–270. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201600134.

- Corrigan, P., Sheehan, L., Morris, S., Larson, J. E., Torres, A., Lara, J. L., Paniagua, D., Mayes, J. I., & Doing, S. (2018). The impact of a peer navigator program in addressing the health needs of Latinos with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 69(4), 456–461. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201700241

- Cuffel, B. J., Fischer, E. P., Owen, R. R., & Smith, G. R. J. (1997). An instrument for measurement of outcomes of care for schizophrenia. Issues in development and implementation. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 20(1), 96–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/016327879702000107.

- Dahl, C. M., de Souza, F. M., Lovisi, G. M., & Cavalcanti, M. T. (2015). Stigma and recovery in the narratives of peer support workers in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. BJPsych International, 12(4), 83–85. https://doi.org/10.1192/s2056474000000611.

- Davidson, L., Bellamy, C., Guy, K., & Miller, R. (2012). Peer support among persons with severe mental illnesses: A review of evidence and experience. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association, 11(2), 123–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.05.009/

- Davidson, L., Chinman, M., Kloos, B., Weingarten, R., Stayner, D., & Tebes, J. K. (1999). Peer support among individuals with severe mental illness: A review of the evidence. Clinical Psycho1ogy: Science and Practice 6(2), 165–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.05.009

- Davidson, L., Chinman, M., Sells, D., & Rowe, M. (2006). Peer support among adults with serious mental illness: A report from the field. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 32(3), 443–450. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbj043.

- Dewhurst, K., McKnight, A. L., & Leopoldt, H. (1974). The Oxford group-home scheme for psychiatric patients. The Practitioner, 213(1274), 195–204.

- Druss, B. G., Singh, M., von Esenwein, S. A., Glick, G. E., Tapscott, S., Tucker, S. J., Lally, C. A., & Sterling, E. W. (2018). Peer-led self-management of general medical conditions for patients with serious mental illnesses: A randomized trial. Psychiatric Services, 69(5), 529–535. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201700352.

- Eisen, S. V., Normand, S.-L., Belanger, A. J., Spiro, A., & Esch, D. (2004). The Revised Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale (BASIS-R): Reliability and validity. Medical Care, 42(12), 1230–1241. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200412000-00010.

- EuroQolGroup. (1990). EuroQol–a new facility for the measurement of health related quality of life. Health Policy, 16, 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9.

- Flanagan, E., Farina, A., & Davidson, L. (2016). Does stigma towards mental illness affect initial perceptions of peer providers? The Psychiatric Quarterly, 87(1), 203–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-015-9378-y.

- Frankl, V. E. (1959). Man's Search for Meaning. Beacon Press.

- Fransen, H., Pollard, N., Kantartzis, S., & Viana-Moldes, I. (2015). Participatory citizenship: Critical perspectives on client-centred occupational therapy. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 22(4), 260–266. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2015.1020338.

- Gillen, G., Hunter, E. G., Lieberman, D., & Stutzbach, M. (2019). AOTA’s top 5 Choosing Wisely® recommendations. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73, 7302420010. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2019.732001

- Green, C. A., Perrin, N. A., Polen, M. R., Leo, M. C., Hibbard, J. H., & Tusler, M. (2010). Development of the patient activation measure for mental health. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 37(4), 327–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-009-0239-6.

- Hammell, K. R. W. (2017). Critical reflections on occupational justice: Toward a rights-based approach to occupational opportunities. Revue Canadienne D'ergotherapie [Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy], 84(1), 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417416654501.

- Herth, K. (1992). Abbreviated instrument to measure hope: Development and psychometric evaluation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 17(10), 1251–1259. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.1992.tb01843.x.

- Higgins, J. P., Altman, D. G., Gøtzsche, P. C., Jüni, P., Moher, D., Oxman, A. D., Savovic, J., Schulz, K. F., Weeks, L., Sterne, J. A., Cochrane B., & Methods Group, Cochrane Statistical Methods Group (2011). The Cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. British Medical Journal, 343(7829), d5928–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928.

- Humbert, T. K. (2016). Addressing spirituality in occupational therapy. In T. K. Humbert (Ed.), Spirituality and occupational therapy: A model for practice and research. AOTA Press.

- Inada, T., & Yagi, G. (1995). Current topics in tardive dyskinesia in Japan. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 49(5–6), 239–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.1995.tb01895.x.

- Jewell, C., Falzer, P., Davidson, L., Rowe, M., & Sells, D. (2006). The treatment relationship in peer-based and regular case management for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 57(8), 1179–1184. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2006.57.8.1179.

- Johnson, S., Lamb, D., Marston, L., Osborn, D., Mason, O., Henderson, C., Ambler, G., Milton, A., Davidson, M., Christoforou, M., Sullivan, S., Hunter, R., Hindle, D., Paterson, B., Leverton, M., Piotrowski, J., Forsyth, R., Mosse, L., Goater, N., … Lloyd-Evans, B. (2018). Peer-supported self-management for people discharged from a mental health crisis team: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 392(10145), 409–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31470-3.

- Jones, N., Corrigan, P. W., James, D., Parker, J., & Larson, N. (2013). Peer support, self-determination, and treatment engagement: A qualitative investigation. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 36(3), 209–214. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000008.

- Kelly, E., Duan, L., Cohen, H., Kiger, H., Pancake, L., & Brekke, J. (2017). Integrating behavioral healthcare for individuals with serious mental illness: A randomized controlled trial of a peer health navigator intervention. Schizophrenia Research, 182, 135–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2016.10.031.

- Kielhofner, G. (2009). Conceptual foundations of occupational therapy practice (4th ed.). F. A. Davis Company.

- Kuhn, W., Bellinger, J., Stevens-Manser, S., & Kaufman, L. (2015). Integration of peer specialists working in mental health service settings. Community Mental Health Journal, 51(4), 453–458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-015-9841-0/

- Law, M., Cooper, B., Strong, S., Stewart, D., Rigby, P., & Letts, L. (1996). The person-environment-occupation model: A transactive approach to occupational performance. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63(1), 9–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841749606300103

- Lehman, A. F. (1996). Measures of quality of life among persons with severe and persistent mental disorders. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 31(2), 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00801903/

- Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(10), e1–e34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006.

- Lloyd-Evans, B., Mayo-Wilson, E., Harrison, B., Istead, H., Brown, E., Pilling, S., Johnson, S., & Kendall, T. (2014). A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of peer support for people with severe mental illness. BMC Psychiatry, 14(1), 39–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244x-14-39.

- Lorig, K., Steward, A., & Ritter, P. (1996). Outcome measures for health education and other health care interventions. Sage.

- Mahlke, C. I., Priebe, S., Heumann, K., Daubmann, A., Wegscheider, K., & Bock, T. (2017). Effectiveness of one-to-one peer support for patients with severe mental illness-a randomised controlled trial. European Psychiatry, 42, 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.12.007.

- McGuire-Snieckus, R., McCabe, R., Catty, J., Hansson, L., & Priebe, S. (2007). A new scale to assess the therapeutic relationship in community mental health care: STAR. Psychological Medicine, 37(1), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291706009299

- McHorney, C. A., Ware, J. E., Jr., & Raczek, A. E. (1993). The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Medical Care, 31(3), 247–263. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006.

- McLellan, A. T., Luborsky, L., Woody, G. E., & O'Brien, C. P. (1980). An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients. The Addiction Severity Index. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 168(1), 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-198001000-00006.

- Mead, S., Hilton, D., & Curtis, L. (2001). Peer support: A theoretical perspective. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 25(2), 134–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0095032.

- Meyer, A. (1922). The philosophy of occupational therapy. Archives of Occupational Therapy, 1, 1–10.

- Muralidharan, A., Brown, C. H., E. Peer, J., A. Klingaman, E., M. Hack, S., Li, L., Walsh, M. B., & Goldberg, R. W. (2019). Living well: An intervention to improve medical illness self-management among individuals with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 70(1), 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800162.

- Parker, G. (2021). In search of logotherapy. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 7, 000486742110628. https://doi.org/10.1177/00048674211062830

- Pelletier, J.-F., Corbière, M., Lecomte, T., Briand, C., Corrigan, P., Davidson, L., & Rowe, M. (2015). Citizenship and recovery: two intertwined concepts for civic-recovery. BMC Psychiatry, 15, 37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0420-2

- Peloquin, S. M. (1989). Sustaining the art of practice in occupational therapy. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 43(4), 219–226. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.43.4.219

- Pickett, S. A., Diehl, S., Steigman, P. J., Prater, J. D., Fox, A., & Cook, J. A. (2010). Early outcomes and lessons learned from a study of the Building Recovery of Individual Dreams and Goals through Education and Support (BRIDGES) program in Tennessee. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 34(2), 96–103. https://doi.org/10.2975/34.2.2010.96.103/

- Polatajko, H. J., Davis, J. A., Hobson, S. J. G., Landry, J. E., Mandich, A., Street, S. L., Whippey, E., & Yee, S. (2004). Meeting the responsibility that comes with the privilege: Introducing a taxonomic code for understanding occupation. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(5), 261–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841740407100503

- Puschner, B., Repper, J., Mahlke, C., Nixdorf, R., Basangwa, D., Nakku, J., Ryan, G., Baillie, D., Shamba, D., Ramesh, M., Moran, G., Lachmann, M., Kalha, J., Pathare, S., Müller-Stierlin, A., & Slade, M. (2019). Using Peer Support in Developing Empowering Mental Health Services (UPSIDES): Background, rationale and methodology. Annals of Global Health, 85(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.2435.

- Radomski, M. V. (1995). There is more to life than putting on your pants. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 49(6), 487–490. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.49.6.487.

- Reilly M. (1962). Occupational therapy can be one of the great ideas of 20th century medicine. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy: Official Publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association, 16, 1–9.

- Repper, J., & Carter, T. (2011). A review of the literature on peer support in mental health services. Journal of Mental Health, 20(4), 392–411. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2011.583947.

- Resnick, S. G., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2010). Who attends Vet-to-Vet? Predictors of attendance in mental health mutual support. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 33(4), 262–268. https://doi.org/10.2975/33.4.2010.262.268.

- Rogers, E. S., Chamberlin, J., & Ellison, M. L. (1997). A consumer-constructed scale to measure empowerment among users of mental health services. Psychiatric Services, 48, 1042–1047. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.48.8.1042.

- Rogers, E. S., Maru, M., Johnson, G., Cohee, J., Hinkel, J., & Hashemi, L. (2016). A randomized trial of individual peer support for adults with psychiatric disabilities undergoing civil commitment. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 39(3), 248–255. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000208.

- Rogers, J. C., Holm, M. B., Bonder, B. R., & Wagner, M. B. (1994). Assessment of self-care. In B. Bonder & V. Bello-Haas (Eds.), Functional performance in older adults (pp. 181–202). F. A. Davis.

- Rowe, M., Bellamy, C., Baranoski, M., Wieland, M., O'Connell, M. J., Benedict, P., Davidson, L., Buchanan, J., & Sells, D. (2007). A peer-support, group intervention to reduce substance use and criminality among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 58(7), 955–961. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2007.58.7.955.

- Sackett, D. L. (1989). Rules of evidence and clinical recommendations on the use of antithrombotic agents. Chest, 95(2 Suppl), 2S–4S.

- Salyers, M. P., Bosworth, H. B., & Swanson, J. W. (2000). Reliability and validity of the SF-12 Health Survey among people with severemental illness. Medical Care, 38, 1141–1150. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200011000-00008.

- Schell, B. A. B., & Gillen, G. (2019). Glossary. In B. A. B. Schell & G. Gille (Eds.), Willard and Spackman’s occupational therapy (13th ed. pp.1191–1215). Wolters Kluwer.

- Sells, D., Black, R., Davidson, L., & Rowe, M. (2008). Beyond generic support: Incidence and impact of invalidation in peer services for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 59(11), 1322–1327. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2008.59.11.1322.

- Silver, J., & Nemec, P. B. (2016). The role of the peer specialists: Unanswered questions. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 39(3), 289–291. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000216.

- Simpson, E. L., & House, A. O. (2002). Involving users in the delivery and evaluation of mental health services: systematic review. British Medical Journal, 325(7375), 1265. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7375.1265.

- Slade, M., Williams, J., Bird, V., Leamy, M., & Le Boutillier, C. (2012). Recovery grows up. Journal of Mental Health, 21(2), 99–103. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2012.670888.

- Sledge, W. H., Lawless, M., Sells, D., Wieland, M., O'Connell, M. J., & Davidson, L. (2011). Effectiveness of peer support in reducing readmissions of persons with multiple psychiatric hospitalizations. Psychiatric Services, 62(5), 541–544. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.62.5.pss6205_0541.

- Snyder, C. R., Sympson, S. C., Ybasco, F. C., Borders, T. F., Babyak, M. A., & Higgins, R. L. (1996). Development and validation of the State Hope Scale. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(2), 321–335. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.70.2.321.

- Stewart, A. L., Nápoles-Springer, A. M., Gregorich, S. E., & Santoyo-Olsson, J. (2007). Interpersonal processes of care survey: patient-reported measures for diverse groups. Health Services Research, 42(3 Pt 1), 1235–1256. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00637.x.