Abstract

Arts-based interventions have been found to benefit adults with mental health conditions, however, the value of nonintervention creative experiences and activities requires further exploration. A scoping review was conducted to identify and map published literature to assist occupational therapists’ understanding of how creativity is experienced within everyday life. Nine databases were searched, and 23 articles were selected. Three forms of creative experiences and five themes related to the person, environment, occupations, spirituality and identity, and barriers and challenges experienced were identified. Findings support the benefits of various forms of creative experiences. Limitations, future research and implications for practice are discussed.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) one in every eight people live with a mental health condition (MHC) that is characterized as experiencing cognitive, emotional and behavioral disturbances (WHO, Citation2022). People living with MHCs experience many barriers that impact their ability to live a meaningful productive life (Pooremamali et al., Citation2017). For some individuals, living with a MHC may include difficulties in establishing routines, learning new skills, developing social connections and finding meaningful employment (Höhl et al., Citation2017; Jennings et al., Citation2021). These difficulties can also contribute to feelings of alienation, marginalization, self-stigmatization and a loss of one’s sense of identity (Cotterill & Coleman, Citation2017). One approach to reduce the impact that living with MHCs can have is the use of creativity which has been described as a “healing, life-affirming activity” (Gillam, Citation2018, p. 21). Overall, there is a need to understand how adults with MHCs living in the community experience nonintervention planned creativity in their daily lives. The potential value of creativity and creative experiences in the everyday lives of adults living with MHCs is examined.

Creativity

The innate drive to create can be considered a basic human need (Mee et al., Citation2004; Schmid, Citation2005). Creativity is used by people across the life span, regardless of age, gender, culture, socioeconomic status, or disability (Fancourt & Finn, Citation2019). There is no one universal definition of creativity with researchers describing the term as ambiguous (Hansen et al., Citation2021; Schmid, Citation2005). There are many different approaches to researching and understanding creativity including personality, individualistic, cognitive, sociocultural and interdisciplinary approaches that each have their own definitions of creativity (Sawyer, Citation2012).

Gillam (Citation2018) summarizes the historical development of these approaches as follows: the individualist approach (1950s–1960s) to creativity used a reductionist perspective that focused on the personality traits of understanding genius creators. Following this the cognitive approach (1970s–1980s) focused on the mental structures and processes involved in creating new products (Gillam, Citation2018). Next, was the development of the sociocultural approach (1980s–1990s), which considers creativity within social, cultural and organizational systems (Gillam, Citation2018). Sociocultural definitions of creativity often describe a product that “is judged to be novel and also to be appropriate, useful, or valuable by a suitably knowledgeable social group” (Sawyer, Citation2012, p. 8). In the sociocultural approach, although a product may be useful and novel to the individual, it may not be necessarily valued as creative by the social group (Sawyer, Citation2012).

Historically, the sociocultural approach has been described as the Big-C creativity which is characterized by remarkable innovation and achievements as determined by a knowledgeable social group (Villanova et al., Citation2021). Unlike the Big C's extraordinary genius-level creativity, the concept of everyday creative activities or sometimes called Little C’s has been under-researched across many fields (Villanova et al., Citation2021).

Everyday creative experiences, occupations and activities

Hasselkus (Citation2011) describes everyday creativity as the mundane moments of life that are filled with spirit, electricity and passion. Adding to this definition, Richards (Citation2018) describes everyday creativity as “having two criteria only: originality and meaningfulness – it is new, and it is understandable. Beyond that, any activity can qualify” (p. 3). Villanova et al.’s (Citation2021) systematic literature review defined everyday creativity as:

A phenomenon in which a person habitually responds to daily tasks in an original and meaningful way… everyday creativity can be either a creative product which is communicated to and assessed by the creator’s immediate society, or a creative experience that is often personal and assessed by only the individual. (p. 691)

Creative experiences and mental health

The role of creative experiences is widely accepted in the promotion of mental health (Acar et al., Citation2021; Creek, Citation2003). Within mental health care settings, several health disciplines such as psychology, art and music therapy, social work and occupational therapy offer forms of creative experience interventions, including crafts, art, recreation, play, music and drama (Smriti et al., Citation2022).

Creative experience interventions can focus on a specific treatment outcome, a healing process, or a therapy goal, such as helping people express and make sense of complex emotions (Hansen et al., Citation2021). For example, these may include singing to reduce distress (Dingle et al. Citation2017), theater to encourage connection (Orjasaeter et al., Citation2017) and painting for self-discovery (Van Lith, Citation2014). Specifically, within mental health, involvement in creative activities (Hansen et al., Citation2022; Perruzza, & Kinsella, Citation2010) has been linked to increased opportunities for recovery through learning vital life skills such as persistence, making decisions, following rules and expressing complex emotions (Tubbs & Drake, Citation2012). Creative activities can also encourage people to think, act, explore and be inventive (Acar et al., Citation2021; Hansen et al., Citation2022; Mee et al., Citation2004; Schmid, Citation2005).

However, there is limited research on how people with MHCs experience and use creativity in their daily lives. Gallant et al. (Citation2019) suggest that research should explore person-centered creative activities instead of exploring creative participation in controlled environments such as a hospital setting with specific treatment-based methods and outcomes (Gallant et al., Citation2019). Areas requiring further research include the reasons people choose to engage in creative experiences and activities and the effect of creativity on mood (Conner et al., Citation2018). There is also some evidence to suggest that creative experiences can act as a stepping stone for individuals to regain their social confidence to participate in meaningful activities within their community (Reberio Gruhl, Citation2017). Further investigation of the research literature is needed to explore whether people with MHCs find creative occupations, activities, acts, and behaviors helpful in their recovery process and how these creative experiences may meet the unique needs of these individuals (Leckey, Citation2011; Hasselkus, Citation2011).

The aim of this scoping review was to identify and summarize the empirical literature that has examined the use of nonintervention creative experiences and creativity in the lives of adults with MHCs living in the community; and to describe and analyze the form they take, how they are utilized and their meaning. The findings of this review will contribute to occupational therapists’ understanding of the value of nonintervention meaningful creative experiences in the everyday lives of adults with MHCs and provide a context for further research.

Methods

Scoping review

A scoping review was conducted to map key concepts in published literature that would inform the authors’ understanding of how adults with MHCs living in the community use and experience nonintervention creativity, creative occupations and activities. Davis et al. (Citation2009) state, “scoping involves the synthesis and analysis of a wide range of research and non-research material to provide greater conceptual clarity about a specific topic or field of evidence” (p. 1386). To address the above purpose, the scoping review followed Arksey and O'Malley’s (Citation2005) and Levac et al.’s (2010) methodological framework which is considered the best framework for conducting a scoping review (Daudt et al., Citation2013).

Stage one: Identifying the research question

To identify and formulate the research question, the first stage involved considering the rationale and clarifying the purpose of the scoping review, identifying and defining the key concepts, the forms of creative experiences, creative use of occupations and activities, and the populations of focus (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005; Levac et al., Citation2010). A working definition of the concept of creativity was developed to include the creative occupations, activities, choices, processes, acts and behaviors that people do in their everyday lives. This working definition was informed by Gallant et al.’s (Citation2019) descriptions of art-based activities as distinct from therapy-based approaches “such as, psychodrama in that they [arts-based activities] are self-initiated and directed rather than being led by a trained clinician, are ongoing rather than facilitated within a planned intervention” (p. 3). This working definition was selected as it did not lend itself to a specific approach, intervention or health care discipline, rather it is focused on the person’s individual and subjective motivation and experience. This working definition also suited our inclusion/exclusion criteria of focusing on people living in the community rather than inpatient care.

These definitions and descriptions of the concepts of creativity led to the articulation of two purpose statements which were to: (a) identify and summarize the literature that explores the use of nonintervention creative experiences and creativity in the lives of adults with mental health conditions living in the community; and (b) describe and analyze the nonintervention creative activities and experiences identified including the form they take, how they are used and their meaning for adults with MHCs living in the community. The research question formulated was “What has been published in the professional literature about the use of nonintervention creativity, creative experiences, occupations, activities, acts and behaviors in the daily lives of adults with mental health conditions living in the community?”.

Stage two: Identifying relevant literature

In stage two, the research team continued to clarify the process and procedures for limiting the scope of the review while locating literature. The purpose statements and research question guided decisions surrounding the search strategy adopted including key terms, journals, and databases searched. The initial search began in January 2020 and continued to December 2022. Key search terms included “occupation*,” “activit*,” “arts and crafts,” “creativ*,” “mental health,” “mental illness,” “mental health condition,” “creative arts,” “activities of daily living” and “occupation.” Searches were completed on nine databases, including Amed, CINAHL, Embase, Medline, ProQuest, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global, PsycInfo, Scopus, and OTDBase. Consistent with the scoping review process, limits such as the date and type of literature were not set to assist in retrieving a wide range of references.

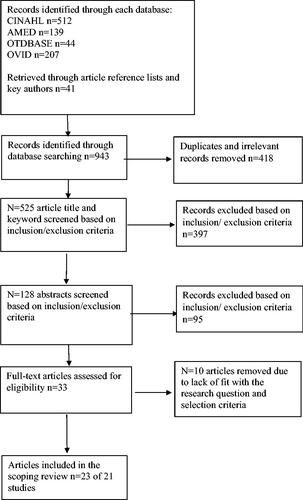

During the searches, literature that considered a range of perspectives on creativity, including editorials and opinion pieces published in journals was noted as they provided contextual and conceptual information used throughout the scoping review process. The database searches produced n = 943 records, which were reduced to n = 525 after irrelevant and duplicate records were removed. See of the adapted PRISMA diagram for the study identification and selection process.

Stage three: Study selection

This stage involved an iterative process where the first author, consulting with the second author, reviewed the titles and keywords of n = 525 articles using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Articles that met the inclusion criteria were those that were published in English in full copy peer-reviewed and grey literature; focused on nonintervention creativity, creative experiences, creative occupations, activities, choices, processes, acts and behaviors; included group or individual creative experiences that took place within the community; and included participants who were 16+ years or older, living in the community with a MHC as defined by The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; DSM–5; American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). This process led to the identification of n = 128 potential articles.

The first two authors reviewed the abstracts of these 128 articles and included those studies that appeared to fit best with the scoping review purpose, question and inclusion criteria (n = 33). The first two authors then scrutinized each article for quality against the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist for qualitative articles (JBI, Citation2020). Some further studies (n = 10) that focused on creative activities as an intervention and were not community-based were removed, resulting in n = 23 final full-text articles from 21 studies for review. Two studies reported different aspects of one study’s findings in two articles (Mee & Sumsion, Citation2001; Mee et al., Citation2004; Van Lith, Citation2014; Van Lith et al., Citation2011). Ten studies were undertaken by occupational therapy researchers and 11 by researchers with other backgrounds. An Excel spreadsheet was used to record retrieved records, database searches and search terms. Articles not meeting the inclusion criteria were highlighted in red, and relevant articles in green. The third author determined the final decision when there was disagreement or uncertainty.

Stage four: Charting the data and stage five: collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

In stages four and five we followed the analysis methods outlined by Arksey and O'Malley (Citation2005) and Levac et al. (Citation2010). To answer the research question and purpose statements, the first and second authors used descriptive numerical and qualitative content analysis methods (for the first purpose statement), and thematic analysis (for the second purpose statement) to chart, collate, summarize, analyze and report the results for the 23 selected articles from the 21 studies. reports the summary details of each of the selected articles, including author/s, year of publication, country of origin, title, research setting and participants, research aim and methodology, creative experience, findings and limitations.

Table 1. Overview of articles included in the scoping review—the meaning and purpose of creativity, creative occupations, activities, acts and behaviors in the daily lives of adults with mental health conditions living in the community, n = 23.

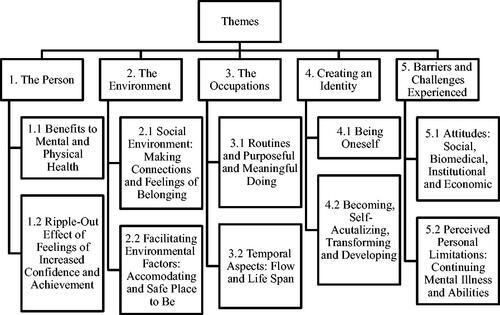

The qualitative thematic analysis method was used to address the second purpose statement. The process was inductive and iterative and involved several steps, including reading each article several times and noting down key phrases onto a separate word document, which were then assigned codes. Next all codes from different articles were grouped to form categories around related concepts that were then combined on a master word document to form tentative themes and subthemes. The first two authors reviewed and discussed these themes and sub-themes to confirm consistency in understanding by using an Excel spreadsheet in which the first two authors made comments on each article. A summary of the frequency of themes and subthemes is presented in .

Table 2. Mapping the themes and subthemes to the 23 selected articles.

As discussed by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) in developing a framework for collating and summarizing results during data analysis, the authors noticed how developed codes and categories could be grouped and presented according to existing concepts, including Wilcock’s (Citation2002) work on doing, being and becoming; and the concepts within the Person-Environment-Occupation Model (Law et al., Citation1996). Stages four and five of the scoping review process, which includes charting the data, collating, summarizing, and reporting the results are presented in the findings and discussion sections (see and ; ).

Limitations

Limitations identified from retrieved scoping study articles are listed in . Whilst the methodologies of the selected studies were generally sound there were some limitations identified. All of the articles except one utilized qualitative research methods which captured participants’ self-reported and self-perceived experiences, therefore valuable information such as quantifiable data related to participants physical (e.g. blood pressure, respiration rate, headaches, pain) and mental health symptoms (e.g. stress, depression, anxiety, medication use, hospitalization rate) were not captured. Most of the published research selected for inclusion in this scoping review focused on community arts-based and creative activity programs offered in a group setting in first world countries. Given the geographical location of where the majority of the studies were conducted this may have presented a biased view. A gap identified by Horghagen et al. (Citation2014) was the scarcity of how people participated in individual creative activities in their own home environments when housebound.

Additionally, most research involved sampling participants who were regular participants attending a program (Lawson, Citation2014; Makin & Gask, Citation2012). However, a limitation of this sampling strategy is that these participants may hold stronger positive perceptions about the community-based creative experiences and the program’s benefits (Bone, Citation2018). Therefore, the experience of those who stopped attending or did not attend community-based creative experience groups were not featured in the review (Horghagen et al., Citation2014).

Findings

Purpose statement one: Identify and summarize the literature that explores the use of nonintervention creative experiences and creativity in the lives of adults with MHCs living in the community

Introduction to studies, countries, research methodology, and participants

The 21 studies in 23 English language research articles were conducted in developed countries including Australia, Canada, Sweden, Ireland, Norway, the United Kingdom and the United States (see ). The date of publication of the articles ranged from 2000 to 2019. All articles except one quantitative article (Dingle et al., Citation2017), utilized qualitative methods to explore participants’ creative experiences. All studies involved adults with MHCs living in the community.

Forms of creative experiences and their settings

As depicted by the number of asterisks in and there were three forms of nonintervention creative experiences: (a) *participatory arts-based programs (11/21 studies), (b) **activity programs (3/21 studies) and (c) ***individual self-initiated daily life activities and occupations (7/21 studies). Most studies (11/21) were of community participatory arts-based programs of varying forms and lengths, with the arts experiences involving arts expert facilitators ranging from art media, creative writing, choir singing to theater. The programs were held in locations such as a museum, art studio, or other suitable setting available in the community (Bone, Citation2018; Dingle et al., Citation2017; Gallant et al., Citation2019; Hui et al., Citation2019; Lawson et al., Citation2014; Lloyd et al., Citation2007; Makin & Gask, Citation2012; Orjasaeter et al., Citation2017; Sapouna & Pamer, Citation2016; Stacey & Stickley, Citation2010; Van Lith, Citation2014; Van Lith et al., Citation2011). Three of the 21 studies involved more informal, mostly drop-in creative activity programs run in the community, offering craft (e. g. ceramics, knitting, jewelry making), horticulture, table-top games, quizzes and puzzles, and woodwork activities (Horghagen et al., Citation2014; Mee & Sumsion, Citation2001; Mee et al., Citation2004; Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000). Seven of the 21 studies were about individuals who self-initiated creativity and creative experiences in their daily life activities and occupations at home and in the community (Lentin, Citation2002; Leufstadius et al., Citation2008; Lin et al., Citation2009; Nagle et al., Citation2002; Potvin et al., Citation2019; Reberio Gruhl, Citation2017; Reynolds, Citation2000).

Purpose statement two: Describe and analyze the creative activities and experiences identified including the form they take, how they are used and their meaning for adults with MHCs living in the community

Presentation of themes

Themes relevant to purpose statement two are depicted in and . Five key themes and sub-themes were found: (a) the person with two sub-themes—benefits to mental and physical health; and the ripple out effects of feelings of increased confidence and achievement; (b) the environment with two sub-themes—the social environment—making connections and feelings of belonging; and facilitating environmental factors—accommodating and safe place to be; (c) the occupations with two sub-themes—routines, and purposeful and meaningful doing; and temporal aspects—flow and life span; (d) spirituality and creating an identity with two sub-themes—being oneself; and becoming, self-actualising, transforming and developing; and (e) the barriers and challenges experienced with two sub-themes—attitudes- social, biomedical, institutional and economic; and perceived personal limitations—continuing mental illness and abilities. Themes and sub-themes were interrelated, for example, the sub-theme social environment—making connections and belonging, was interrelated with reported mental and physical health benefits and purposeful and meaningful doing. Aspects of the themes and sub-themes were also found to be consistent with existing concepts identified in the Person-Environment-Occupation Model (Law et al., Citation1996) and Wilcock’s framework of doing, being, belonging and becoming (Wilcock, Citation2002; Citation2006). Findings were also consistent with Perruzza and Kinsella’s (Citation2010) literature review which identified themes related to “enhanced perceived control, building a sense of self, expression, transforming the illness experience, gaining a sense of purpose and building social support” (p. 1).

Theme one: The person

Benefits to mental and physical health

Findings reported that involvement in creative activities, creative experiences and processes was valuable to mental health recovery (Gallant et al., Citation2019; Horghagen et al., Citation2014; Hui et al., Citation2019; Lentin, Citation2002; Lloyd et al., Citation2007; Makin & Gask, Citation2012; Nagle et al., Citation2002; Van Lith, Citation2014; Van Lith et al., Citation2011). Reported health benefits included: improved self-esteem (Bone, Citation2018; Lawson et al., Citation2014; Lin et al., Citation2009; Reynolds, Citation2000; Sapouna & Pamer, Citation2016; Van Lith et al., Citation2011), personal insight (Orjasaeter et al., Citation2017; Van Lith et al., Citation2011), reduced rumination (Hui et al., Citation2019; Makin & Gask, Citation2012), an increased ability to tolerate difficult emotions (Dingle et al., Citation2017; Makin & Gask, Citation2012; Reynolds, Citation2000; Van Lith et al., Citation2011), a sense of joy (Leufstadius et al., Citation2008; Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000), personal connection (Van Lith, Citation2014) and social connectedness (Hui et al., Citation2019).

One of the most cited benefits of engaging in creative activities was to escape mental health symptoms (Van Lith, Citation2014). Potvin et al. (Citation2019) found video gaming provided a distraction from self-harming thoughts, and Reynolds (Citation2000) study described how one woman used needlecraft to slow her heart rate and breathing when experiencing episodes of panic. Another participant stated that without the café drop in facility, they would be “hanging from a tree with a rope around my neck” (Mee et al., Citation2004, p. 230). Some study participants used creative experiences to get to know oneself better (Orjasaeter et al., Citation2017; Stacey & Stickley, Citation2010) and understand the self through an outsider’s perspective (Van Lith, Citation2014).

Papers reported that music produced a range of emotional experiences, including feeling uplifted and appreciating loss and sadness, and helped people to “express themselves without having to put words on it” (Sapouna & Pamer, Citation2016, p. 5). Dingle et al. (Citation2017) found that choir singing enhanced positive emotions and decreased negative emotions. Van Lith et al. (Citation2011) identified that visual creative works encouraged self-reflection as emotional experiences associated with being mentally unwell were communicated, released and processed. Within the horticultural program, emotions were communicated through the choice of color, textures and objects used when making cards and floral arrangements (Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000). The horticultural program also provided a sensory experience for participants to dig in the dirt, smell the flowers, taste the herbs and have the opportunity to reminisce and reconnect to positive memories.

Ripple-out effects of feelings of increased confidence and achievement

Lawson et al. (Citation2014) described that confidence grew with participating in creative programs which had “ripple-out effects” on other areas of participants’ everyday lives, such as becoming a volunteer (p. 770). Confidence spreading to other areas of participants’ lives was also reported by (Makin & Gask, Citation2012; Mee et al., Citation2004; Stacey & Stickley, Citation2010). Simple creative activities provided participants with a powerful sense of achievement, pride and competence (Hui et al., Citation2019; Leufstadius et al., Citation2008; Mee et al., Citation2004; Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000; Reynolds, Citation2000; Stacey & Stickley et al., 2010; Van Lith, Citation2014) this included when participants remembered the words to a song (Dingle et al., Citation2017), were cooking marmalade or cleaning their house (Leufstadius et al., Citation2008) or reminisced on a previous project they had completed (Van Lith et al., Citation2011).

A sense of achievement also contributed to observed positive changes in participants’ ability to make eye contact, verbal expression, and body language (Lawson et al., Citation2014; Lloyd et al., Citation2007; Mee et al., Citation2004). When finishing a creative project, participants were intensely proud of themselves, with some showcasing their art with others (Lloyd et al., Citation2007; Sapouna & Pamer, Citation2016), publishing a book (Gallant et al., Citation2019), making gifts for others or decorating their home with created items (Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000).

Everyday creative experiences also included acts such as dancing to music on a TV show, cooking, completing an educational course, creating new relationships with society, creating a worker identity and creating a family (Dingle et al., Citation2017; Lentin, Citation2002; Leufstadius et al., Citation2008; Lin et al., Citation2009; Nagle et al., Citation2002; Potvin et al., Citation2019; Reberio Gruhl, Citation2017). New activities provided more interest and challenge and produced the greatest sense of achievement (Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000).

Theme two: The environment

Social environment: making connections and feelings of belonging

Making connections and belonging was a prominent theme in all but two studies (Dingle et al., Citation2017; Potvin et al., Citation2019). Connections formed were with the group, facilitators, family, friends and the wider community (Gallant et al., Citation2019; Reberio Gruhl, Citation2017). Participants enjoyed interacting with different types of people-staff, volunteers, artists and mental health workers (Hui et al., Citation2019). Several participants and researchers noted how living with MHCs severed meaningful social connections (Nagle et al., Citation2002; Orjasaeter et al., Citation2017). However, the benefits of attending creative art and activity programs negated some isolation (Stacey & Stickley, Citation2010) and disconnection from the community (Bone, Citation2018). Having a place to go in the community was important (Leufstadius et al., Citation2008). Horghagen et al. (Citation2014) reported that the strong connection participants felt with each other through doing crafts together and the peer support they gave each other to manage everyday occupations facilitated recovery, and assisted in preventing re-hospitalization.

Connection took place by meeting people, sharing everyday experiences, sharing the space, working toward group goals, experimenting together, listening, watching and becoming bonded as a group (Horghagen et al., Citation2014; Lawson et al., Citation2014; Makin & Gask, Citation2012; Orjasaeter et al., Citation2017; Sapouna & Pamer, Citation2016; Stacey & Stickley, Citation2010; Van Lith et al., Citation2011). Several studies noted how creative community programs were the link for people to create and rebuild their lives in the community (Hui et al., Citation2019; Lawson et al., Citation2014; Makin & Gask, Citation2012). Participants described how singing in a choir could be used to connect and communicate with society regarding stigma and MHCs safely and engagingly (Lloyd et al., Citation2007).

Research that included creative experiences in a group setting found that participants acted as a team, motivating and inspiring others (Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000). Participants were also looking to feel needed by others (Leufstadius et al., Citation2008). For example, helping others in the community or a creative activity group (Mee et al., Citation2004) gave individuals a sense of a greater purpose beyond the individual self (Leufstadius et al., Citation2008; Van Lith, Citation2014).

For participants who did not attend a formal creative program, creating connections included sitting in a public place, watching people, listening to music, playing musical instruments with others, watching other people socializing (Lin et al., Citation2009), using play to connect with one’s children (Lentin, Citation2002) and helping or caring activities to connect with family and others (Leufstadius et al., Citation2008; Lin et al., Citation2009; Nagle et al., Citation2002). People found creative ways to engage with their community by attending a café or a garage sale (Leufstadius et al., Citation2008) or doing their needlework on the train or during breaks at work (Reynolds, Citation2000). These acts gave participants a sense of connection to the broader community and their family.

Facilitating environmental factors: accommodating and safe place to be

Many participants perceived creative experience programs as a safe place for them (Bone, Citation2018; Gallant et al., Citation2019; Horghagen et al., Citation2014; Sapouna & Pamer, Citation2016; Van Lith, Citation2014; Van Lith et al., Citation2011). Participants identified that if they did not have a place to go to get out of the house (Hui et al., Citation2019) they would be “looking at the four walls, going mad” (Mee & Sumsion, Citation2001, p. 125). The result was that people felt they had a safe option available to them that they could voluntarily attend when they could not access more formalized medical appointments (Horghagen et al., Citation2014).

The perceived safety of the environment was influenced by the predictability (Horghagen et al., Citation2014), flexibility (Bone, Citation2018; Gallant et al., Citation2019; Horghagen et al., Citation2014; Mee & Sumsion, Citation2001; Van Lith, Citation2014; Van Lith et al., Citation2011), the non-stigmatizing environment (Bone, Citation2018; Lawson et al., Citation2014; Orjasaeter et al., Citation2017) and how welcoming staff and participants were (Mee & Sumsion, Citation2001). These elements afforded comfortability and encouraged relaxation. Participants also described not feeling pressured to engage in conversation or the art-making process, which encouraged the gradual progress of participants to enter into the group with the presence of additional support (Makin & Gask, Citation2012). Reduced perceived pressure contributed to facilitator-participant trust (Van Lith et al., Citation2011). Overall, staff facilitators were described as encouraging, providing guidance and encouragement to participants (Van Lith et al., Citation2011). Environments perceived as overwhelming were believed to exacerbate one’s MHCs and contribute to the use of less effective coping strategies such as smoking (Nagle et al., Citation2002) and self-injurious behaviors (Potvin et al., Citation2019).

Nagle et al.’s (Citation2002) study found that participants wanted “structured but flexible leisure, work and social opportunities over which they had some control” (p. 80). This includes the opportunity for choice through offering different options for frequency of attendance, length of time to participate, or a decision to share and emotionally express themselves with others (Mee & Sumsion, Citation2001; Van Lith et al., Citation2011). Compared to a more structured program model, the drop-in program model utilized in Mee and Sumsion (Citation2001) study had several perceived benefits, including a sense of autonomy and empowerment, as participants could attend on their own volition and staff had minimal involvement in the provided activities. Overall, the flexibility of the environment, including choice, time and level of engagement, was a key finding for increasing participants’ sense of comfort and safety (Horghagen et al., Citation2014; Nagle et al., Citation2002).

Theme three: The occupations

Routines and purposeful and meaningful doing

Purposeful and meaningful doing was a recurrent theme amongst retrieved articles. Studies reported a range of meaningful and creative forms of self-care, productive and leisure activities. Activities such as creating art work, helping plant flowers, building and riding a bike, busking, volunteering, being involved in research, homemaking, being a carer and needlecraft were mentioned (Gallant et al., Citation2019; Lawson et al., Citation2014; Lentin, Citation2002; Lin et al., Citation2009; Mee & Sumsion, Citation2001; Nagle et al., Citation2002; Perrins-Margalis, Citation2000; Stacey & Stickley, Citation2010; Reberio Gruhl, Citation2017; Reynolds, Citation2000; Van Lith, Citation2014).

Being creative was identified as allowing people to experience a sense of purpose (Perrins-Margalis, Citation2000), normality and productive time use (Lawson et al., Citation2014; Mee & Sumsion, Citation2001). For example, it “makes my day feel like I did something worthwhile today for myself” (Gallant et al., Citation2019, p. 7). Objects created were also identified as gifts for other people, reinforcing participants’ purpose and roles as friends and family members (Horghagen et al., Citation2014; Mee et al., Citation2004).

Instead of isolating when feeling the impact of their mental health symptoms, participants tried to participate in activities such as exercise, listening to music, doing chores (Dingle et al., Citation2017), or needlecraft (Reynolds, Citation2000). Participants also spoke about how they acquired different skills through participating in different activities, such as learning to use their hands and mind together (Mee & Sumsion, Citation2001). In the absence of traditional work, creative activities helped participants structure their daily routines (Nagle et al., Citation2002), including feeling motivated to get out of bed in the morning, select which day/group they wanted to attend, enter the community, participate with others, go home, prepare food, and rest (Horghagen et al., Citation2014; Makin & Gask, Citation2012; Van Lith et al., Citation2011). Having planned activity time resulted in less time spent in less helpful activities such as time in bed, drinking coffee, doing nothing, and time spent at home, thereby reducing the amount of time spent in rumination and feeling distressed (Gallant et al., Citation2019; Lawson et al., Citation2014, Leufstadius et al., Citation2008; Lloyd et al., Citation2007; Makin & Gask, Citation2012; Mee & Sumsion, Citation2001; Mee et al., Citation2004; Van Lith et al., Citation2011).

This sense of purposeful and meaningful doing helped people “escape this shame of not working” (Gallant et al., Citation2019, p. 6), thereby helping create a sense of occupational balance, normality and joy (Leufstadius et al., Citation2008; Perrins-Margalis, Citation2000; Van Lith et al., Citation2011). Participants identified that having a routine encouraged them to create plans and work toward goals (Leufstadius et al., Citation2008). For example, Reberio Gruhl’s (Citation2017) study reported how a participant named James found busking was a productive occupation for making ends meet so that he could purchase coffee, food and tobacco. He also shared how busking contributed to feeling like he had a meaningful place within his community (Reberio Gruhl, Citation2017). However, not all meaningful occupations participants use as a coping strategy or to connect with others are socially approved. For instance, participants in Potvin et al.’s (Citation2019) study spent extensive amounts of time gaming, staying in bars or at the movies.

Temporal aspects: flow and life span

Csikszentmihalyi Citation1996s concept of flow or immersion was also identified as a key benefit of creative experiences (Lawson et al., Citation2014; Mee & Sumsion, Citation2001; Reynolds, Citation2000; Van Lith Citation2014; Van Lith et al., Citation2011). Csikszentmihalyi (Citation1996) described a state of flow as being immersed in a creative experience that matches a person’s abilities and skills. The elements required to create an experience of flow include a balance between the challenges and skills required of an activity, a merging of action and awareness, clear goals and feedback, complete concentration, having a sense of control, the loss of self-consciousness and the loss of sense of time (Csikszentmihalyi et al., Citation2014). It is possible therefore that nonintervention creative experiences and activities that people engage in promotes a sense of flow within them.

Creative experiences were described as grounding, validating and empowering (Van Lith et al., Citation2011). When participants were engaged in creative experiences, their mental health problems were no longer the focus of their attention (Makin & Gask, Citation2012). Being immersed in creative experiences was identified as time spent “getting back to me” (Van Lith et al., Citation2011, p. 656), contributing to feeling refreshed and building one’s sense of self-identity (Reynolds, Citation2000). Being creative and concentrating on a project increased participants’ sense of control and safety in a period of their life they described as chaotic and distressing (Horghagen et al., Citation2014; Reynolds, Citation2000). This feeling of safety and stability facilitated other roles throughout the week (Horghagen et al., Citation2014).

An important aspect was the continued involvement in creative activities and experiences within participants’ lives over time. Lloyd et al. (Citation2007) reported that the art works participants created in an ongoing community arts program served as milestones in their recovery, capturing “the essence of their experience at that point in time” (p. 211). For the participants in Gallant et al. (Citation2019) and Lentin (Citation2002), ongoing participation in creating their personal life stories provided participants with a sense of continuity in times of other life changes.

Theme four: Spirituality and creating an identity

Being oneself

Being creative was an awakening spiritual experience that connected participants with their true selves (Lloyd et al., Citation2007; Van Lith et al., Citation2011). Creative experiences enabled participants to create their stories (Sapouna & Pamer Citation2016) and see beyond their life as a person with a mental illness identity role (Bone, Citation2018; Hui et al., Citation2019; Lawson et al., Citation2014). Instead, participants could create social and community identity roles such as being a group member, contributor, sharer, peer, friend, family member, worker and member of society (Gallant et al., Citation2019; Horghagen et al., Citation2014; Lentin, Citation2002; Lin et al., Citation2009; Mee et al., Citation2004; Orjasaeter et al., Citation2017; Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000; Potvin et al., Citation2019; Reberio Gruhl, Citation2017; Reynolds, Citation2000).

Participating in creative experiences encouraged participants to stop trying to be something and “just be yourself” (Mee et al., Citation2004, p. 230). Stacey and Stickey (2010), who explored the significance of art to people with MHCs, found that creativity is “an integral aspect of the person’s perception of themselves and that for many it is an essential component of the way they wish to live their life” (p. 70).

Becoming: self-actualizing, transforming and developing

The processes and experiences of doing, being and becoming are intertwined. Participating in a range of purposeful and meaningful creative occupations, activities, acts and behaviors was important in restoring and creating one’s self-identity when living with a mental illness (Bone, Citation2018; Gallant et al., Citation2019; Hui et al., Citation2019; Lawson et al., Citation2014; Leufstadius, Citation2008; Lloyd et al., Citation2007; Mee et al., Citation2004). According to Wilcock (Citation2002), becoming refers to a sense of future and authenticity between one’s doing, goals and values. Creating an identity was consistently described in papers as a process of self-discovery (Bone, Citation2018; Mee et al., Citation2004). This is an important finding as participants spoke about how mental illness was often associated with a loss of self and identity (Lentin, Citation2002; Lloyd et al., Citation2007; Orjasaeter et al., Citation2017). Identity was recognized as a critical ingredient in the recovery process for participants. Forensic outpatients living in the community in Lin et al.’s study wanted to be seen as “doing the right thing” and known as a good citizen (p. 112). For James, creating a social identity through busking was vital for feeling valued and acknowledged within the community. Busking also connected James to his family and cultural Celtic heritage (Reberio Gruhl, Citation2017).

Van Lith’s (Citation2014) paper “painting to find myself” (p. 19) presents the argument that recovery research has overlooked how distressing the process of trying to find oneself and one’s purpose is. Self-discovery was described as a creative and continuous journey that enabled participants to discover parts of themselves within the world (Lloyd et al., Citation2007; Orjasaeter et al., Citation2017). This journey included learning, reflecting, and acquiring new life skills and identities (Lentin, Citation2002; Lloyd et al., Citation2007; Orjasaeter et al., Citation2017). Van Lith et al. (Citation2011) cited Deegan’s (1988) idea that “recovery is a journey rather than an end destination, a transformative process in which the old self is gradually relinquished, and a new self emerges” (p. 652). This process is evident in Van Lith et al.'s research, as participating in creative arts encouraged participants to “gain wisdom through self-reflection” (p. 658) and to process and release emotions. Orjasaeter et al. (Citation2017) found that the theater and music project for Nelly (participant) was “the space needed to allow her to be herself and to become herself” (p. 5). Furthermore, using everyday objects such as clothing and accessories (such as a necktie and briefcase) helped participants create a community identity, thereby feeling integrated with society (Lentin, Citation2002).

Theme five: Barriers and challenges experienced

Attitudes: social, biomedical, institutional and economic

The arts-based programs’ aims were focused on raising social awareness, reducing the stigma associated with poor mental health and making social connections (Gallant et al., 2017; Hui et al., Citation2019). When there were no formal community-based programs, Lin et al. (Citation2009) found that stigma, and institutional and social restraints affected forensic outpatients returning to former occupations and reconnecting with friends and acquaintances. James had to overcome shame and social stigma to engage in busking (Reberio Gruhl, Citation2017).

Unlike the participants in the other studies, many of the meaningful occupations and activities of the young adult participants reported in Potvin et al.’s (Citation2019) study were not viewed positively by society either because they were socially disapproved or because there was an overinvestment in them such as video-gaming. Some participants in Lin et al.’s (Citation2009) study replaced perceived unhealthy occupations with healthier ones. Although society disapproved of video-gaming, Lin et al.’s (Citation2009) study shows that some participants tried to find creative ways to cope, such as creating a virtual life in which they felt they could control their emotions and create meaningful connections with others.

Although many participants valued being in a group program, some participants noted that the social environment contributed to increased pressure and restrictions (Lawson et al., Citation2014; Stacey & Stickley, Citation2010). For example, Van Lith (Citation2014) reported an issue for a participant was the lack of acknowledgement by staff in the arts-based program of the importance of spirituality in their personal meaning-making process through art. Other challenges included the intake process to attend the group, which included supplying character references and an interview contributing to potential anxiety for some participants (Bone, Citation2018). Similarly, the involvement of leaders and educators can result in reduced project ownership for participants (Lawson et al., Citation2014; Stacey & Stickley, Citation2010).

The need for the continuity of ongoing engagement in creative experiences was evident in the findings of most studies. However, there were concerns about the lack of opportunities (Nagle et al., Citation2002), and the continued viability and shortage of funds to maintain many of the programs, given the socio-economic emphasis on biomedical approaches (Bone, Citation2018; Lin et al., Citation2009; Stacey & Stickley, Citation2010). The ending of a structured creative group project produced anxiety as participants were uneasy about the absence of having a creative project to do (Van Lith et al., Citation2011). In contrast, several participants stated that participating in too many mental health programs may contribute to an increased sense of being unwell or reinforce stigma (Sapouna & Pamer, Citation2016).

Perceived personal limitations: continuing mental illness and abilities

Many participants reported how their mental health influenced their ability to engage in creative work, affecting their MHCs (Stacey & Stickley, Citation2010). One participant from Nagle et al.’s (Citation2002) study that sought to understand the daily occupational activities of people with severe mental illness shared that:

When I am sick there is nothing. There is just sleep, vegetate, maybe eat something, drink water, milk or coffee and stuff like that. Nothing productive… If I feel sick, I don’t do anything. (p. 75)

Other personal barriers participants identified that hindered their creative experiences included a lack of confidence and perceived limitations of ability, such as thoughts of inadequacy or a poor self-image (Lin et al., Citation2009). In a six-week horticultural program, some participants did not perceive themselves as artistic and most of the participants felt challenged at some point by not being able to meet the demands of parts of an activity, such as wearing gloves or where potential harm was involved (e.g., using a hot glue gun) (Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000). Several participants reported that the perceived personal pressure had contributed negatively to their depressed mood (Bone, Citation2018; Lawson et al., Citation2014). In addition, physical health factors such as fatigue and pain impacted participants’ participation in creative experiences (Lawson et al., Citation2014; Reberio Gruhl, Citation2017).

Discussion

The purpose of the scoping review was to identify and summarize the literature that explored the use of nonintervention creative experiences and creativity in the lives of adults living with MHCs in the community; and to describe and analyze the form they take, how they are utilized and their meaning. The scoping review identified three forms of creative experiences: (a) participatory arts-based programs (11/21 studies), (b) activity programs (3/21 studies) and (c) individual self-initiated daily life activities and occupations (7/21 studies). The following discusses the features and relevant themes and subthemes of the forms of creative experience.

Participatory arts-based programs and activity programs

All participatory arts-based and activity programs were delivered within the community environment. In particular, the theme of the environment with sub-themes of the social environment: making connections and feelings of belonging; and facilitating environmental factors: accommodating and safe place to be were strongly reported in the findings of 20 studies. Findings showed that creative arts-based programs delivered in the community provided a safe environment to feel connected and experience reciprocity and social citizenship (Bone, Citation2018; Gallant et al., Citation2019; Hui et al., Citation2019; Lawson et al., Citation2014; Makin & Gask, Citation2012; Orjasaeter et al., Citation2017; Sapouna & Pamer, Citation2016; Stacey & Stickley, Citation2010; Van Lith et al., Citation2011). Creating alongside other group members provided positive experiences of constructing an occupational identity as the group collectively explored their abilities and provided a safe space for acceptance and shared expectations of belonging to a group (Hui et al., Citation2019; Nagle et al., Citation2002; Orjasaeter et al., Citation2017; Stacey & Stickley, Citation2010).

Interestingly, findings highlight the importance, benefits and use of non-threatening, less clinical and familiar community spaces such as libraries, museums, council halls and galleries offering creative programs (Fancourt & Finn, Citation2019). Unlike art therapy, these programs were focused on art-making skills. An advantage of the arts-based programs compared to engaging in self-initiated creative activities is that participants often attended a group facilitated by artists and were provided opportunities to feel supported in learning new skills (Perrins-Margalis, Citation2000). A disadvantage that should be noted is that individuals may not own the resources and tools to create or participate in activities such as pottery, leatherwork, basketry, mosaic tile work, woodworking and jewelry making at home.

Further, as Damiano and Backman (Citation2019) identified, arts-based programs can experience institutional, administrative and financial difficulties in sustaining community-based programs. As demonstrated in theme five, barriers and challenges can include limited funding support, difficulty accessing a physical space, the time-limited nature of the group and withdrawal of artist support (Stewart et al., Citation2019; Van Lith et al., Citation2011). These challenges can contribute to feelings of anxiety and a sense of grief and loss for participants when a program ends (Damiano & Backman, Citation2019; Van Lith et al., Citation2011). For mental health service provided community activity programs, Damiano and Backman highlighted challenges in obtaining and sustaining funding for the occupational therapist’s role and encouraging participants to transition from being a “client” in the program to reintegrating within the community.

One suggestion to negate this challenge was encouraging participants to become “alumni” and volunteers through teaching the class rather than being recipients of the program, thereby reducing dependence on the program and its resources. This transition can be met with mixed emotions by some participants who do not want to assume a role that increases their responsibility in the program, especially if graduated members are not financially reimbursed for their time or skills. Additional barriers to attending activity programs may include the stigma associated with only socializing with others in institutional or mental health facilities and severe social anxiety (Bone, Citation2018; Lin et al., Citation2009; Stacey & Stickley, Citation2010; Van Lith et al., Citation2011).

Through observations and fieldnotes from their ethnographic study of participants who attended a craft group at a meeting place service in a Norwegian city, Horghagen et al. (Citation2014) reinforced that there is a need for ongoing nontreatment/intervention-focused programs to be readily available for people living with MHCS in the community. In particular, healthcare professionals should consider how creative experiences could be utilized in the natural and everyday lives of people with MHCs.

Individual self-initiated daily life activities and occupations

Seven studies reported on how individuals incorporated creativity in their daily life activities and occupations (Lentin, Citation2002; Leufstadius et al., Citation2008; Lin et al., Citation2009; Nagle et al., Citation2002, Potvin et al., Citation2019; Reberio Gruhl, Citation2017; Reynolds, Citation2000). Three individual studies provided rich narratives of their participants’ efforts in creating a life of meaning and purpose (Nagle et al., Citation2002; Lentin, Citation2002; Reberio Gruhl, Citation2017). Hasselkus (Citation2011) explains that creative doing through ordinary, mundane occupations provides a vehicle for the expression of spirituality and the essence of who one is. Occupation provides opportunities to reconnect with existing stories and create new stories as demonstrated in the theme of spirituality and creating an identity (Hasselkus, Citation2011; Lentin, Citation2002).

Also evident in the findings is a sense of time, as participants often selected activities, occupations and environments that held significant meaning to past experiences (Lentin, Citation2002; Reberio Gruhl, Citation2017). These findings are supported by Hansson et al.'s (Citation2022) concept analysis of occupational identity, which provides further evidence of the complex and positive relationship between doing, being and future becoming. Specifically, Hansson et al. describe occupational identity construction, which refers to the potential of meaningful doing in building and knowing one’s new self over time, which is often embedded within sociocultural contexts.

Self-initiated creativity also involved exploration and experimentation (Lentin, Citation2002). Rather than being directed by another, such as a facilitator, artist or health professional, these individual creative acts or activities provide participants agency to create their day through the choice of valued, meaningful activities as demonstrated in the themes of the occupations and the environment. An advantage of this freedom is the flexibility to use creativity according to one’s needs, energy and MHC (Reynolds, Citation2000). Unlike with traditional activity groups, individuals can participate in dark occupations, which may be judged as less socially sanctioned by others, such as video gaming or busking (Potvin et al., Citation2019). These alternative occupational experiences include risk taking such as James’s busking and standing in the cold or experiencing stigmatizing comments from members of the public (Hocking, Citation2020; Potvin et al., Citation2019; Reberio Gruhl, Citation2017).

All three forms of creative experiences

All three forms of creative experiences included the theme of the person with sub-themes of benefits to mental and physical health, and the ripple out effect of feelings of increased confidence and achievement (21 studies). Regardless of the participant’s age, diagnosis or cultural background, participating in creative experiences provided the potential for improved mental health (Gallant et al., Citation2019; Horghagen et al., Citation2014; Hui et al., Citation2019; Lentin, Citation2002; Lloyd et al., Citation2007; Makin & Gask, Citation2012; Nagle et al., Citation2002; Van Lith, Citation2014; Van Lith et al., Citation2011). The benefits to mental and physical health were also reported by Leckey’s (Citation2011) systematic review investigating the evidence of the therapeutic effectiveness of a diverse range of creative activities on mental well-being within a mental health context. Leckey (Citation2011) found evidence that involvement in creative activities can have a “healing and protective effect on mental well-being” (p. 506), increasing relaxation, reducing stress and blood pressure, and enhancing the immune system. These findings are important as they add value and rationale for the provision of nonintervention individual and community-based creative experiences for adults with ongoing MHCs living in the community.

All three forms of creative experiences included the theme occupations with sub-themes of routines and purposeful and meaningful doing; and temporal aspects such as flow experiences and life span development were reported in 17 studies. A state of flow was a participant experience identified in the scoping review’s findings. The experience of flow contributes to increased attention to the present moment and can reduce distracting thoughts and feelings (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1996). The benefits of flow were reported as increased focus, decreased distress and a feeling of refreshment (Reynolds, Citation2000; Van Lith et al., Citation2011). Participants in Sutton et al.’s. (Citation2012) study, also described the experience of focused attention, enjoyment, integration with the environment and “the flow of action and time” when they were engrossed in occupations (p. 146). One consideration is that the sense of flow and expression may become disrupted in a group environment when participants are required to share the same space, tools and resources (Perrins-Margalis, Citation2000).

The findings of this scoping review indicate that an identity construction process occurred in individual and group environments. Nineteen studies reported findings related to the theme of spirituality, creating an identity with sub-themes of being oneself; and becoming, self-actualising, transforming and developing.

An interesting challenge mentioned by participants was the perceived social pressure to be creative or become an artist (Lawson et al., Citation2014; Stacey & Stickley, Citation2010). Although this finding was only identified in group-based settings, this challenge could also present itself for those participating in individual creative activities at home. Western philosophical perspectives of creating works accepted by society as valuable and unique may contribute to internalized pressure of people with MHCs to meet unnecessary self and societal expectations (Rampley et al., Citation2019; Villanova et al., Citation2021). These social pressures may also contribute to a sense of shame and inadequacy as participants may want to identify themselves as being an artist, published writer or performing musician (Bone, Citation2018; Lawson et al., Citation2014; Rampley et al., Citation2019). These findings are important considerations for shaping positive, creative experiences focused on experiences of personal well-being and engagement rather than on one’s creativity being valued or accepted by society (Rampley et al., Citation2019).

Implications for practice

The intent of the scoping review was to examine the use of nonintervention creative experiences and creativity with adults living with MHCs in the community; and to outline their meaning, the forms they took and how they were utilized. There are several implications for practice including the fact that there is a need for ongoing nontreatment/intervention focused programs to be readily available for people living with MHCS in the community, particularly post discharge from inpatient stays. Given the focus on community settings, therapists should consider how creative experiences can be actively integrated into the daily repertoires, habits and interests of people living with MHCS. The community settings need to promote making connections and feelings of belonging as well as being accommodating and a safe place for people living with MHCS to be. Suggested community environments to hold creative occupations could include libraries, museums, council halls, church halls, schools, and galleries offering creative programs. It is also recommended where possible and feasible, that the nonintervention creative experiences and creative occupations utilized with adults living with MHCs in the community be client-centered, and that programs be evaluated for their effectiveness and impact.

Limitations and recommendations for future research

There are several limitations in the research identified in this scoping review. Whilst qualitative methodologies enable in-depth study, a limitation is that the majority of studies utilized qualitative research methods involving small numbers of participants. Future research should include larger sample mixed methods designs to quantify outcomes directly resulting from individuals participating in creative experiences. For example, numerical data on participants’ use of healthcare service before, during and after participation in community-based creative activities would be beneficial in substantiating the cost benefits of facilitating engagement in creative experiences in the everyday lives of adults living with MHCs. Additionally, changes in participants’ physical health (e.g. blood pressure, headaches, and pain), and mental health symptoms such as the frequency of panic and psychotic episodes and the use of illicit substances or self-mutilation could be recorded.

Future research to understand the experience of those who stopped attending or do not attend community-based creative experience groups would be valuable (Horghagen et al., Citation2014). Future research is needed in the conceptualization and definition of creativity which remains unclear and lacks a common understanding across disciplines (Hansen et al., Citation2021). This view is supported by Villanova et al. (Citation2021), who recommend further research to understand how everyday creativity occurs using subjective qualitative methodologies in various contexts. Further investigation into the features, function, purpose and meaning of self-initiated everyday creative experiences for people with MHCs living in the community is needed. Finally, future research should aim to include research from other interdisciplinary perspectives and health journals to form a comprehensive understanding of creativity.

Conclusion

This paper reviewed published literature concerning the nonintervention use of creativity, creative occupations, activities, acts and behaviors in the lives of adults living with MHCs in the community. Five themes with sub-themes related to the person, the environment, the occupation, spirituality and creating an identity, and the barriers and challenges to creative experiences were identified. The review found strong evidence that engagement in various creative experiences, everyday creative individual activities, participatory arts-based programs and activity programs can help support people with MHCs to create a meaningful and purpose-filled life. The findings assist understanding of how creativity is experienced within the everyday lives of adults with mental health conditions living in the community and the benefits of engagement in various forms of creative experiences. Overall, further research into how people with MHCs use everyday creative experiences within their daily lives is needed to inform and provide further evidence of the value and means of incorporating them into the provision of ways to better support the recovery of adults living with mental health conditions in the community.

Authors’ contributions

All three authors were involved in the conception, development and drafting of the manuscript. LL and PL conducted the literature search, manuscript selection and qualitative synthesis of the studies’ results. All three authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We honour and thank the people of the Kulin Nations Victoria and the Bunurong people as our community partners and traditional inhabitants of the lands of the City of Melbourne in the Region of Mornington Peninsula and surrounding areas, where this research was conducted.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References*Articles included in the review identified with an asterisk.

- Acar, S., Tadik, H., Myers, D., Sman, C., & Uysal, R. (2021). Creativity and well‐being: A meta‐analysis. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 55(3), 738–751. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.485

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). APA. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Blanche, E. I. (2007). The expression of creativity through occupation. Journal of Occupational Science, 14(1), 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2007.9686580

- *Bone, T. A. (2018). Art and mental health recovery: Evaluating the impact of a community-based participatory arts program through artist voices. Community Mental Health Journal, 54(8), 1180–1188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-018-0332-y

- Christiansen, C. H. (2004). Occupational identity: Becoming who we are through what we do. In C. H. Christiansen & E. A. Townsend (Eds.), Introduction to occupation: The art and science of living (pp. 121–139). Prentice Hall.

- Conner, T. S., DeYoung, C. G., & Silvia, P. J. (2018). Everyday creative activity as a path to flourishing. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 13(2), 181–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1257049

- Cotterill, D., & Coleman, L. (2017). Creativity as a transformative process. In C. Long, J. Cronin-Davis & D. Cotterill (Eds.), Occupational therapy evidence in practice for mental health (2nd ed., pp. 35–58). John Wiley & Sons.

- Creek, J. (2003). Occupational therapy defined as a complex intervention. College of Occupational Therapists.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. Harper/Collins.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., Abuhamdeh, S., & Nakamura, J. (2014). Flow. In M. Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly (Ed.), Flow and the foundations of positive psychology (pp. 227–238). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9088-8_15

- Davis, K., Drey, N., & Gould, D. (2009). What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(10), 1386–1400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.02.010

- Daudt, H.M., van Mossel, C. & Scott, S.J. (2013). Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Medical Research methodology13(48), 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-48

- Damiano, N., & Backman, C. L. (2019). More than art, less than work: The paradoxes of citizenship and artmaking in community mental Health. BC Studies, 0(202), 41–63. https://doi.org/10.14288/bcs.v0i202.190424

- *Dingle, G. A., Williams, E., Jetten, J., & Welch, J. (2017). Choir singing and creative writing enhance emotion regulation in adults with chronic mental health conditions. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56(4), 443–457. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12149

- Fancourt, D., & Finn, S. (2019). What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? A scoping review. WHO Regional Office for Europe. https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289054553

- *Gallant, K., Hamilton-Hinch, B., White, C., Fenton, L., & Lauckner, H. (2019). Removing the thorns: The role of the arts in recovery for people with mental health challenges. Arts & Health, 11(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/17533015.2017.1413397

- Gillam, T. (2018). Creativity, wellbeing and mental health practice. Palgrave Pivot.

- Hansen, B. W., Erlandsson, L., & Leufstadius, C. (2021). A concept analysis of creative activities as intervention in occupational therapy. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 28(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2020.1775884

- Hansen, B., Leufstadius, C., Pedersen, H., Berring, L., & Erlandsson, L. (2022). Experiences of occupational value when doing creative activities in a mental health context. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 38(4), 383–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2022.2067285

- Hansson, S. O., Björklund Carlstedt, A., & Morville, A.-L. (2022). Occupational identity in occupational therapy: A concept analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 29(3), 198–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2021.1948608

- Hasselkus, B. R. (2011). The meaning of everyday occupation (2nd ed.). SLACK.

- Hocking, R. (2020). The dark side of occupation: Accumulating insights from occupational science. In R. Twinley (Ed.), Illuminating the dark side of occupation: International perspectives from occupational therapy and occupational science (pp. 17–25). Taylor & Francis Group.

- Höhl, W., Moll, S., & Pfeiffer, A. (2017). Occupational therapy interventions in the treatment of people with severe mental illness. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 30(4), 300–305. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000339

- *Horghagen, S., Fostvedt, B., & Alsaker, S. (2014). Craft activities in groups at meeting places: Supporting mental health users’ everyday occupations. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 21(2), 145–152. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2013.866691

- *Hui, A., Stickley, T., Stubley, M., & Baker, F. (2019). Project eARTh: Participatory arts and mental health recovery, a qualitative study. Perspectives in Public Health, 139(6), 296–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913918817575

- Jennings, C., Lhuede, K., Bradley, G., Pepin, G., & Hitch, D. (2021). Activity participation patterns of community mental health consumers. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 84(9), 561–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022620945166

- Joanna Briggs Institute. (2020). Checklist for qualitative research: Critical appraisal tools for use in JBI Systematic Reviews. https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools

- Law, M., Cooper, B. A., Strong, S., Stewart, D., Rigby, P., & Letts, L. (1996). The Person-Environment-Occupation Model: A transactive approach to occupational performance. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63(1), 9–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841749606300103

- *Lawson, J., Reynolds, F., Bryant, W., & Wilson, L. (2014). ‘It’s like having a day of freedom, a day off from being ill’: Exploring the experiences of people living with mental health problems who attend a community-based arts project, using interpretative phenomenological analysis. Journal of Health Psychology, 19(6), 765–777. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105313479627

- Leckey, J. (2011). The therapeutic effectiveness of creative activities on mental well-being: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 18(6), 501–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01693.x

- *Lentin, P. (2002). The human spirit and occupation: Surviving and creating a life. Journal of Occupational Science, 9(3), 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2002.9686502

- *Leufstadius, C., Erlandsson, L. ‐K., Björkman, T., & Eklund, M. (2008). Meaningfulness in daily occupation among individuals with persistent mental illness. Journal of Occupational Science, 15(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2008.9686604

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O'Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5, 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- *Lin, N., Kirsh, B., Polatajko, H., & Seto, M. (2009). The nature and meaning of occupational engagement for forensic clients living in the community. Journal of Occupational Science, 16(2), 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2009.9686650

- *Lloyd, C., Wong, S. R., & Petchkovsky, L. (2007). Art and recovery in mental health: A qualitative investigation. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 70(5), 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802260707000505

- *Makin, S., & Gask, L. (2012). ‘Getting back to normal’: The added value of an art-based program in promoting ‘recovery’ for common but chronic mental health problems. Chronic Illness, 8(1), 64–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742395311422613

- *Mee, J., & Sumsion, T. (2001). Mental health clients confirm the motivating power of occupation. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 64(3), 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802260106400303

- *Mee, J., Sumsion, T., & Craik, C. (2004). Mental health clients confirm the value of occupation in building competence and self-identity. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 67(5), 225–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802260406700506

- *Nagle, S., Cook, J. V., & Polatajko, H. J. (2002). I'm doing as much as I can: Occupational choices of persons with a severe and persistent mental illness. Journal of Occupational Science, 9(2), 72–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2002.9686495

- *Ørjasæter, K. B., Stickley, T., Hedlund, M., & Ness, O. (2017). Transforming identity through participation in music and theatre: Exploring narratives of people with mental health problems. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 12(sup2), 1379339. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2017.1379339

- *Perrins-Margalis, N. M., Rugletic, J., Schepis, N. M., Stepanski, H. R., & Walsh, M. A. (2000). The immediate effects of a group-based horticulture experience on the quality of life of persons with chronic mental illness. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 16(1), 15–32. https://doi.org/10.1300/J004v16n01_02

- Perruzza, N., & Kinsella, E. (2010). Creative arts occupations in therapeutic practice: a review of the literature. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(6), 261–268. https://doi.org/10.4276/030802210X12759925468943

- Pooremamali, P., Morville, A.-L., & Eklund, M. (2017). Barriers to continuity in the pathway toward occupational engagement among ethnic minorities with mental illness. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 24(4), 259–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2016.1177590

- *Potvin, O., Vallée, C., & Larivière, N. (2019). Experience of occupations among people living with a personality disorder. Occupational Therapy International, 2019(9030897), 9030897. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/9030897

- Rampley, H., Reynolds, F., & Cordingley, K. (2019). Experiences of creative writing as a serious leisure occupation: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Journal of Occupational Science, 26(4), 511–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2019.1623066

- *Reberio Gruhl, K. (2017). Becoming visible: Exploring the meaning of busking for a person with mental illness. Journal of Occupational Science, 24(2), 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2016.1247381

- *Reynolds, F. (2000). Managing depression through needlecraft creative activities: A qualitative study. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 27(2), 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-4556(99)00033-7

- Richards, R. (2018). Everyday creativity and the healthy mind dynamic new paths for self and society (1st ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

- *Sapouna, L., & Pamer, E. (. (2016). The transformative potential of the arts in mental health recovery – An Irish research project. Arts & Health, 8(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/17533015.2014.957329

- Sawyer, K. (2012). Introduction. In K. Sawyer (Ed.), Explaining creativity: The science of human innovation (pp. 3–14). Oxford University Press.

- Schmid, T. (2005). Promoting health through creativity: An introduction. In T. Schmid (Ed.), Promoting health through creativity: For professionals in health, arts and education (pp. 1–26). Wiley.

- Smriti, D., Ambulkar, S., Meng, Q., Kaimal, G., Ramotar, K., Park, S., & Huh-Yoo, J. (2022). Creative arts therapies for the mental health of emerging adults: A systematic review. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 77, 101861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2021.101861

- *Stacey, G., & Stickley, T. (2010). The meaning of art to people who use mental health services. Perspectives in Public Health, 130(2), 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466424008094811

- Stewart, V., Roennfeldt, H., Slattery, M., & Wheeler, A. J. (2019). Generating mutual recovery in creative spaces. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 23(1), 16–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-08-2018-0029

- Sutton, D. J., Hocking, C. S., & Smythe, L. A. (2012). A phenomenological study of occupational engagement in recovery from mental illness. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. Revue Canadienne D'ergotherapie, 79(3), 142–150. https://doi.org/10.2182/cjot.2012.9.3.3

- Tubbs, C. C., & Drake, M. (2012). Introduction: Crafts in perspective. In C. C. Tubbs & M. Drake (Eds.), Crafts and creative media in therapy (4th ed., pp. 3–9). Slack.