Abstract

Despite guidance to minimize restrictive practice within the UK, seclusion and long-term segregation are necessary to maintain the safety of patients and clinicians. There is little evidence to guide the work of occupational therapists with secluded patients. A literature search identified seven papers that met the study inclusion criteria. A deductive approach to thematic analysis was conducted using the ‘Model of Human Occupation’ as a theoretical framework to identify issues related to occupational need during a period of seclusion. Findings indicate ways in which occupational therapists could engage with patients in seclusion and suggest a need for future research.

Introduction

Seclusion and long-term segregation in mental health

In the United Kingdom (UK), patients who have been detained under the Mental Health Act (Citation1983) are cared for in mental health hospitals or secure settings. Sometimes, patients become increasingly unwell in the ward environment and their behavior poses a risk to themselves or others. If de-escalation is unsuccessful, as a last resort, patients may be secluded to maintain safety (Bowers et al., Citation2017). Seclusion and long-term segregation in mental health units are both defined as a form of restraint or force (Mental Health Units Use of Force Act, 2018) used when behavioral disturbance in patients poses significant risk of harm to the patient or others. The Mental Health Act (Citation1983) Code of Practice (2015) outlines the variances in the use of restraint. Seclusion is designed to manage risk in the short term, with the patient being isolated from other patients and staff members, often in a specialist seclusion room or suite. Although there is no time limit on seclusion, UK legislation and policy state that it should be used for the shortest possible duration (Social Care, Local Government and Care Partnership Directorate, Citation2014). In the UK guidelines suggest that patients should be continuously observed, with regular nurse and medical reviews and a multi-disciplinary team (MDT) meeting after eight hours, followed by subsequent daily MDT meetings to assess the patient’s wellbeing and potential to reintegrate into the ward (Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust, Citation2019). Long-term segregation is utilized when periods of seclusion have not been successful in reducing the risk to self and others and the potential for harm remains too high to reintegrate the patient into the ward environment. When a patient is cared for in long-term segregation, the environment should be comfortable and personalized, rather than the clinical environment of a seclusion suite (Care Quality Commission, Citation2015). While in long-term segregation, the patient should be encouraged to participate in meaningful therapeutic activities and to continue to develop and engage in therapeutic relationships with staff (Mental Health Act Citation1983 Code of Practice, 2015). These therapeutic relationships may be seen as protective factors and time spent working with a patient while in seclusion or segregation can be used to build trust and rapport, potentially reducing the need for seclusion in the future (Chieze et al., Citation2019).

Legislation and policy

Although the Care Quality Commission (CQC) in the UK set out guidelines for seclusion facilities in order to maintain safety (CQC, Citation2015), the published interim report on seclusion and segregation of people with mental health problems, learning disabilities and autism (CQC Citation2019) found many seclusion areas were not fit for purpose. Furthermore, there were not sufficient staff members with adequate training to provide the specialist care, resulting in a negative impact on patients. Specialist occupational therapy (OT) services working within the sector could be part of the multi-disciplinary team, delivering this specialist care and training less qualified members of staff.

In the United Kingdom, there are currently no National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline for long-term segregation, however NICE Guideline 10 (NICE, Citation2015) outlines the short-term management of patients whilst in seclusion. Local policy, such as the Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust seclusion and long-term segregation policy (Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust, Citation2019) are informed by overarching government legislation, so the lack of NICE guidelines means fewer sources of information to draw from and therefore local policies are less informed. The Royal College of Occupational Therapists (RCOT) have published guidance for Occupational Therapists (OTs) working in secure hospitals (RCOT, Citation2017a) illustrating the importance of identifying and addressing occupational deprivation. Patients in seclusion are at heightened risk of this and OTs are well placed to work with patients to reduce the negative effects of isolation, by supporting engagement in meaningful activity. These guidelines do not provide advice for OTs working in seclusion, however, do recognize the need for further research in this area.

Occupational therapy working with patients in seclusion

OT in a mental health inpatient setting aims to promote engagement in meaningful activity whilst undertaking assessment of functional skills to better understand the impact of the patient’s mental illness; using this understanding to provide patient centered care (RCOT, Citation2017b). The Mental Health Act (Citation1983) Code of Practice (2015) states that during periods of seclusion or long-term segregation patients should be supported to engage with activities that hold meaning, suggesting OTs are well placed to offer interventions that meet patient’s occupational needs. Despite this, there is a lack of evidence to support occupational therapists in their clinical practice, highlighting the importance of further research in this area to illustrate the benefits of OT to employers (Fitzgerald, Citation2016).

Maintaining an occupational focus could address potential occupational deprivation experienced in long-term segregation (Whiteford et al., Citation2020), with patients unable to access the range of activity usually available to them. Continued participation in meaningful activity facilitates the maintenance and development of skills and motivation, increasing potential to reintegrate into the ward environment and progress to eventual discharge (Whiteford et al., Citation2020). OTs in mental health inpatient services often receive training in sensory processing that can be adapted for therapeutic use in seclusion (Dunn, Citation2007). The use of sensory strategies such as education around triggers and coping strategies, individual sensory kits, and modification of the environment may prevent prolonged or further episodes of segregation or make the period of segregation more therapeutic for the patient (Andersen et al., Citation2017). The range of skills OTs are equipped with in understanding patients’ occupational needs and facilitating engagement make them a valuable part of the multi-disciplinary team and have potential to improve outcomes for service users (Evatt et al., Citation2016).

Aims and objectives

The Mental Health Act Code of Practice (2015) outlines an expectation for care providers to reduce the use of seclusion and restraint. As a result, there is a growing body of quantitative research that aims to understand seclusion duration and how external factors may affect this (Cullen et al., Citation2018), however, quantitative research does not recognize the human experience of seclusion. Qualitative research in this area aims to understand the views and experiences of service users, staff and carers who have lived experience of seclusion. Highlighting the patient voice, can aid healthcare providers in improving service delivery by gaining insight into the personal experiences, views, and opinions of people with lived experience of receiving mental health care. At the time of writing, there was little qualitative literature examining the experience of seclusion, and no qualitative syntheses could be found. Therefore, this review aimed to identify and synthesize qualitative studies that examined the patient, staff or carer experience of seclusion or long-term segregation.

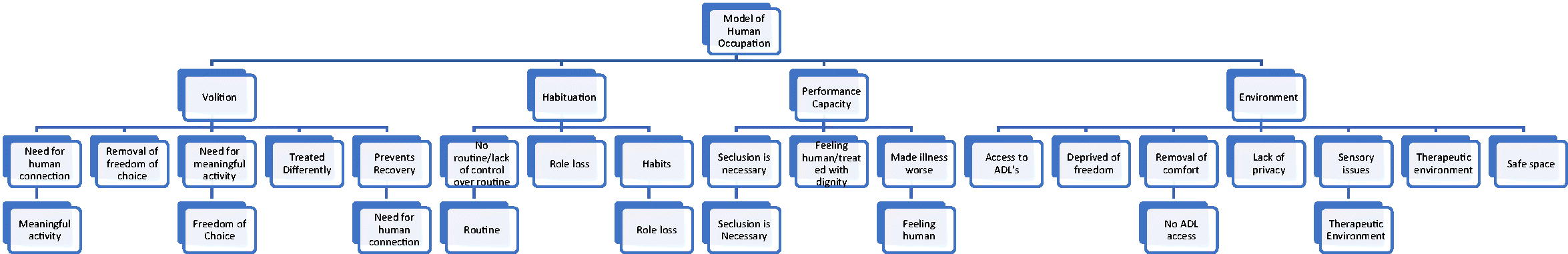

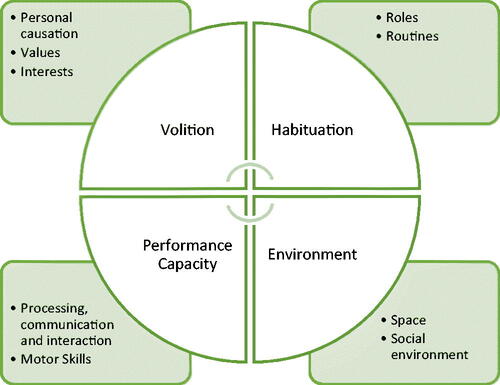

In order to provide an occupational therapy lens through which to view the data within the articles, a deductive approach was taken, using the concepts within MOHO (Kielhofner, Citation2002) as outlined in .

Figure 1. Illustrating Kielhofner’s (Citation2002) model of human Occupation.

The literature review question developed from these aims was: Can the experiences of patients, staff and carers inform the potential role for occupational therapy in seclusion and long-term segregation?

Materials and methods

This literature review aims to synthesize existing qualitative literature and analyze the qualitative findings to inform future OT practice. A qualitative research synthesis (QRS) was adopted for this review, and a three-phase results process implemented (Savin-Baden & Major, Citation2010):

Data analysis: developing themes across individual studies selected for review.

Data synthesis: unifying themes from the individual studies into overarching themes.

Data interpretation: interpreting themes and drawing conclusions.

Database selection

To ensure the search was robust and identified as many appropriate articles as possible, searches were made on the following databases which encapsulate the majority of OT and psychiatric care journals: Delphis, MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and AMED. To ensure relevant OT articles were included, searches were also performed on the British Journal of Occupational Therapy, Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, Australian Journal of Occupational Therapy, and The American Occupational Therapy Journal websites, in line with the search strategy.

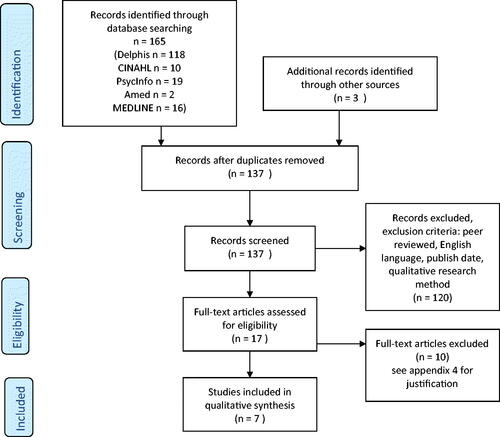

A hand search of reference lists was performed and screened using the inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine suitability. Grey literature databases were not searched due to time constraints as illustrated in .

Table 1. Search inclusion and exclusion criteria and justifications.

Search strategy

Search terms were developed using the SPIDER tool (Cooke et al., Citation2012), illustrated in Appendix A. A thesaurus was used to identify potential search term synonyms, and key terms in relevant papers were reviewed to include subject specific terminology. The key terms used were ‘seclusion’ (or long-term segregation, psychiatric intensive care, PICU), ‘inpatient’ (or detained, hospital, mental health unit/hospital), ‘occupational therapy’ (or meaningful activity) and ‘mental health’ (or mental/psychiatric illness, mental/psychiatric disorder). After articles were selected, abstracts were screened against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Those that were included were full text screened, refer to Appendix B for excluded articles.

Screening process

To ensure transparency and to clearly illustrate the screening process (Liberati et al., Citation2009), a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram was used (Moher et al., Citation2009), illustrated in in .

illustrates the studies selected for inclusion in this synthesis.

Table 2. Overview of papers selected for synthesis.

Study characteristics

Seven papers met the inclusion criteria, with the study characteristics outlined in . Further information regarding the strengths and limitations of the research papers is outlined in Appendix C.

Although the search strategy aimed to include research that incorporated data from nurses, patients and carers, the majority of papers collated only patient data. Brophy et al. (Citation2016) obtained qualitative data from the perspective of patients and carers, while Holmes et al. (Citation2015) examined data from both patients and nursing staff. As a result, there was insufficient clinician or carer data to include in the synthesis, so only the patient data from these research papers will be included.

None of the selected papers examined long-term segregation. The data extracted from the articles, therefore, will only include qualitative data examining patient experience of seclusion.

Critical appraisal process

All articles that met the requirements were appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, Citation2018) for qualitative research, in order to assess their quality and suitability for inclusion in the synthesis, as outlined in . Seven studies met the first two criteria on the CASP (Citation2018) checklist. In line with existing qualitative syntheses (Stomski & Morrison, Citation2017), the remaining eight CASP (Citation2018) questions were scored as follows: three points where there is data to comprehensively answer the question; two points when the issue had been somewhat addressed but not comprehensively; one point when it was unclear whether the issue had been addressed or there were no details to answer the question. The studies could achieve a maximum score of 24, and all studies scored 17 and above. No studies were excluded from this review as a result of their CASP score, however if any had scored less than average (16), they would have been excluded. The critical appraisal process did not highlight any ethical issues within the studies, despite selecting studies from a variety of countries, all studies had obtained the required ethical approval. CASP scores are illustrated in .

Table 3. CASP scores of papers selected for synthesis.

Thematic analysis and data synthesis

As the search strategy allowed for the inclusion of research from disciplines other than OT, an OT model was selected in order to provide an occupational lens when analyzing the research. This ensured data gathered was relevant to the research question.

Several models were considered, however as OT models are designed to be applied to individuals, some were unsuitable to be applied to research. The Person-Environment-Occupation-Performance model (Baum et al., Citation2015) was considered but when applied to a research paper in a trial, was not as efficient at extracting data as the Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) (Kielhofner, Citation2002). MOHO is also suggested to be the most used and evidence-based model of OT practice (Lee et al., Citation2012), furthermore, RCOT recommend MOHO for use in secure mental health services (RCOT, Citation2017a). Consequently, MOHO (Kielhofner, Citation2002) was selected to provide the framework.

The data extraction and thematic analysis process began with a single researcher reading and re-reading the articles to familiarize themselves with the data (Clarke & Braun, Citation2013). Stage one involved categorizing any relevant data into the four main concepts within MOHO (Kielhofner, Citation2002); volition, habituation, performance capacity and environment. Stage two involved following thematic analysis (Clarke & Braun, Citation2013) processes and line by line coding the data within each of these concepts. The third stage involved grouping the codes and developing key themes within each concept. Appendix D outlines the sub theme refining process. To ensure a rigorous process was carried out, the data trail and emerging themes were reviewed and verified within the multidisciplinary research team.

Findings

Quotes will be used from the original studies in support of the synthesis, in this section, the studies have been referred to by numbers, as illustrated in the overview of papers in .

Volition

The need for human connection

Desire to have increased or improved human contact while in seclusion was expressed in all seven of the research papers and as such, was the most common theme across all four concepts. This highlights the meaning patients place on human contact. Patients across the studies found the experience of solitude difficult, with participants commenting: “I only wanted the real presence of a human being, with nurses and physicians, more communication, human touch…” (2). Other participants found this need for human connection negatively impacted their mental health: “I wanted to get out of there because I was depressed to be alone, to be locked up. I was depressed from being alone, without people” (6).

Freedom of choice

Frustration around the removal of freedom of choice was a theme in four of the papers selected for review (1–3 and 7). Risk management in seclusion practice means that often, patients’ ability to make small decisions is impacted. This participant highlighted the lack of control they felt: “I don’t like being in the cell thing, because you’re not allowed snacks and stuff” (3) another patient in this study also commented: “I didn’t get much to eat, and that I didn’t like” (3). Patients in other studies felt the practice of seclusion was used to enforce rule following: “Seclusion and restraint is about compliance” (1) which was also echoed by a patient in study two: “it was like shock treatment, punishment and deprivation of liberty, nothing good in it.”

Meaningful activity

Boredom and a lack of meaningful activity was identified as an issue in four papers (1–3, and 5). Some patients recognized the need for risk assessment and understood supervision would be needed for risk items while highlighting the importance of meaningful activity in reducing boredom and the negative impact of seclusion on their mental health: “If in supervised confinement, you should be allowed newspapers/books or a bible. It’s boring, you end up going mad.” (Study 5). Boredom was mentioned again in study two:” I did not have anything to do in the seclusion/restraint room, it was a long time, boring, distressing…” this view harmonizes with a patient from paper three who used the terms “boring” and “demoralising” to describe their experience of seclusion.

Patients in study two provided insight into the activities that held meaning for them that they felt would reduce their seclusion rate: “I need physical activities when I am restless, a boxing sack on the ward, going out cycling or walking, something sensible to do…”. When patients are secluded, they are often deemed to be at risk of causing harm to themself, or others. In order to minimize this risk, patients are not always offered meaningful activity whilst in seclusion, as a participant in study three stated: “we all have programs in this building, we’re all doing things, so they’re really taking away from what we’re doing… we miss all the programs, we miss our job, we miss outings”.

Habituation

Routine

Being secluded removes the option for patients to engage in their regular routine. Participants in four papers (1–3, and 5) identified having no control over their routine, or their routine being disrupted as a negative aspect of seclusion. A participant in paper one used the term “learned helplessness” in describing the effect of seclusion on their ability to maintain their usual routine.

Role loss

Removing a patient from the ward environment limits the maintenance and development of roles that form an important part of their self-identity, impacting on both their roles within the hospital and their ability to make contact and preserve their roles in their regular home environment. Loss of role was explored in four of the papers (3, 5, 6 and 7). Patients in three papers (5, 6 and 7), reported lack of contact with their families as being a negative aspect of seclusion, and the restrictions placed on their role as a family member or friend was expressed as a contributing factor to the patient’s unhappiness: “my sister doesn’t come, my brothers don’t come… and I have no one. I don’t even have friends that come… and I have no one, I don’t even have friends that come. I have nobody… I feel sadder the others don’t come… I wonder why they [the staff] don’t come”.

The meaning found in ward-based roles, such as through vocational rehabilitation was addressed by a patient in paper three who when discussing their experience of seclusion stated: “we miss our job”.

Performance capacity

Seclusion is necessary

Despite patients finding seclusion a difficult and sometimes traumatic experience, there was an awareness among participants in two papers (2 and 3) of the need for seclusion in order to minimize risk to self or others. In this sub theme some patients spoke positively of seclusion: “I think it can be a great tool for people, it keeps people safe”; “When you have patients that don’t want to follow the rules or people that have negative symptoms… it’s pretty much a necessity” (3). “They told me how aggressive and unpredictable I was before seclusion. I understood that this was the only alternative and a part of my treatment…” (2)

Feeling human

Four papers identified how the experience of seclusion impacts on how patients feel about themselves as human beings (papers 1, 2, 3, and 5). Patients in three studies (1, 3 and 5) reported feeling dehumanized by the seclusion experience: “Angry and animalistic… cage, cold… felt treated like an animal” (5); “Nothing is important about seclusion rooms. It’s just wrong. They treat people like animals. It’s just like keeping a dog in a cage” (3); “you literally just get dehumanized and its sort of that once you have become part of that system you do become almost, well not completely, but treated in a sub-human way. You can do things that you would not normally do. If you had a cancer patient in that same situation the furor would be terrible with the treatment, they receive” (1). A participant in paper two spoke of compassionate treatment holding equal value to regular ward treatment, while in seclusion: “I hope that I am a human being in a psychiatric hospital and in the seclusion room too. I want polite, humane treatment from the staff…”

The environment

Access to activities of daily living

In addition to restricting patients’ freedom of choice, in some cases the procedure of seclusion and the design of the seclusion room restrict the access to activities of daily living (ADL’s), such as washing, dressing, eating and drinking. Several of the papers included in this review suggest the seclusion room did not include free access to a bathroom, preventing patients from meeting basic human needs such as using the toilet. Six out of the seven papers included in the review discussed the restriction of access to ADL’s. with three papers (2, 3 and 6) highlighting the restrictions around bathroom access. A participant in paper two used language that emphasized the infantilisation and humiliation of the seclusion experience: “They washed my hair once a week and I didn’t have a chance to brush my teeth. I was thirsty and peed into the floor drain”. This feeling of neglect was echoed by a participant in study six: “Sometimes you’re hungry, they don’t open the door, you want to go to the bathroom, they [staff] don’t open the door”.

Therapeutic environment

Some patients recognized that seclusion offers a safe space which enables risk reduction and time away from the ward environment can be beneficial. Participants in five of the papers discussed the therapeutic benefit of seclusion and in two studies, participants acknowledged the potential to use sensory strategies to improve the experience. A participant in paper two made suggestions for sensory improvements: “beautiful colors on the walls and ceiling, cosy room with peaceful music, soft chairs”. A participant in paper five had further sensory suggestions: “buttons on the wall you can press, and it plays sounds, sensory sounds, like thunder and classical music”.

Discussion

The aim of this literature review is to understand the experiences of seclusion from the perspectives of patients, staff, and carers so that they can inform the role of occupational therapy in this unique environment. There was very little staff (one paper) and carer (one paper) data, so this was not incorporated into the themes. However, all seven of the reviewed papers included the patient’s perspective which enabled the development of themes relating to their experiences. Qualitative data which develops an understanding of the patient experience can help clinicians and policy makers to provide improved patient centered care (Crowe et al., Citation2015).

The most common subtheme was ‘the need for human connection’. Patients spoke of their desire for continued therapeutic relationships during their period of seclusion, and their subsequent distress when this did not happen. Research has suggested that working with patients whilst in seclusion can build trust and rapport, potentially reducing the need for future seclusion (Chieze et al., Citation2019). Lack of continued contact between the patient and their trusted clinicians, including the OT, could result in re-traumatisation and feelings of abandonment, delaying recovery and damaging the therapeutic relationship (Muskett, Citation2014). Without continued input from a patient’s regular clinician during seclusion, restorative work would be required to rebuild trust. Recent literature by Sherwood (Citation2021) has highlighted how in the past, occupational therapy has paused while a person is in seclusion, but that in current practice, OTs in the UK are increasingly continuing their work during periods of patient seclusion, which is vital to preventing occupational deprivation and facilitating recovery. The Mental Health Act (Citation1983) Code of Practice (2015) also recognizes the need for therapeutic relationships with staff to be maintained. Therefore, it is essential that OTs understand the importance of maintaining the therapeutic relationship with the patient by continuing to provide therapy sessions in seclusion.

It is unsurprising that he next two most discussed subthemes (therapeutic environment and access to ADL) relate to the environment as it is accepted that seclusion areas by design are very restrictive and often not fit for purpose (CQC, Citation2015). Several patients felt they benefited from the low stimulus environment of the seclusion room, although across the papers positive patient experience was minimal. More patients reported finding the seclusion environment oppressive and felt that it negatively impacted their mental health and recovery. Recommendations were made for the improvement of the seclusion experience by participants who suggested making the décor and fittings more therapeutic. This aligns with research by Meehan et al. (Citation2000) where participants felt a therapeutic environment would reduce feelings of distress when secluded.

This type of environment where patients cannot access their usual activities, such as the self-care activities described in the reviewed papers, can lead to occupational deprivation. However, it has been recognized that engaging patients in occupations can reduce the potential for occupational deprivation (Whiteford et al., Citation2020). OTs have the skills and knowledge to provide appropriate occupations and support the engagement of the patient. They also understand how the environment in which a person lives affects occupational performance (Kielhofner, Citation2002), and should advocate for patients to have a therapeutic environment in which to be secluded. This could include risk assessed artwork or interactive media panels, which allows the patient some control over their environment (National Association of Psychiatric Intensive Care Units, Citation2017).

Patients also discussed the need for sensory strategies to improve the seclusion environment. Andersen et al. (Citation2017) support this view reporting that strategies such as education for staff around sensory triggers, modification of the environment and the use of individual sensory kits can make the experience more therapeutic and reduce the length of seclusion. Patients with mental health conditions are more likely to have sensory processing dysfunction (Javitt & Freedman, Citation2015) and OTs working within these services are often the only discipline trained in sensory processing (Dunn, Citation2007). OTs can provide guidance to the multi-disciplinary team around incorporating sensory strategies into practice (Cromwell, Citation2013). A study by Wright et al. (Citation2020) highlighted the important role OTs play in delivering training to the wider team and promoting sensory strategies to clinicians from other disciplines. Andersen et al. (Citation2017) found the use of restraint was reduced by 40% after staff received training in utilizing sensory modulation strategies, this is supported by Yakov et al. (Citation2018) who found a 72% reduction in restraint after analysis of patients’ sensory needs and subsequent implementation of sensory strategies. In this study no literature was found around the use of sensory modulation during a period of seclusion, however, having awareness of patients’ sensory needs while in seclusion could allow OTs to use patients’ sensory profiles or diets to help patients co-regulate.

Four of the subthemes, ‘freedom of choice’, ‘meaningful activity’, ‘role less’ and ‘routine’ are closely related. Patients discussed the removal of choice within their day-to-day life, the loss of their daily routine, roles and subsequent lack of any meaningful activities often leading to feelings of boredom. Continued participation in meaningful activity facilitates the maintenance and development of skills and motivation, increasing potential to reintegrate into the ward environment and progress to eventual discharge (Whiteford et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, the Mental Health Act (Citation1983) Code of Practice (2015) states that during periods of seclusion patients should be supported to engage with activities that hold meaning, suggesting a clear role for occupational therapy.

It is also acknowledged that one of the aims for OTs working in mental health settings is to promote engagement in meaningful activities whilst undertaking functional assessments (RCOT, Citation2017b). OTs are well placed to address the occupational deprivation that comes with being secluded (Kearns Murphy & Shiel, Citation2019). OT’s core values include enabling patients to participate in occupations that are meaningful to them, and fulfill their occupational potential, while providing patient centered care (RCOT, Citation2017b).

Patients in the reviewed studies identified the restrictions around freedom of choice and meaningful activity as elements of seclusion that they felt negatively impacted them. Dike et al. (Citation2021) found that using Wellness Recovery Action Plans (WRAP) (Copeland, Citation1997) significantly reduced the amount of time patients spent in seclusion. OTs could play an integral role in care planning when a patient is stable by assisting patients to write a WRAP, which could include the patient’s wishes on which occupations they would like to engage in if they are secluded (Gardner et al., Citation2012), including meaningful OT interventions and sensory strategies that had been shown to regulate the patient.

The remaining two themes have conflicting views. There was a positive acknowledgement in two papers that ‘seclusion is necessary’ for the safety of staff and patients but in contrast to this, there was a negative view in four papers that seclusion leads to ‘feeling inhuman’ with patients describing their feelings of being treated like animals. It is widely accepted that seclusion is necessary in mental health units to manage risk (Holmes et al., Citation2015), however, the patient experience should be considered, and adaptations made where possible to increase the therapeutic benefit and make seclusion more recovery orientated. Traditional risk assessment can restrict recovery and therefore positive risk taking is acknowledged as a significant element of mental health care (Boardman & Roberts, Citation2014). The RCOT emphasizes the importance of positive risk taking and highlights it as an essential element of effective OT practice (RCOT, Citation2018). Combining positive risk taking with the knowledge that OTs have regarding activity analysis and the ability to grade and adapt occupations puts them in a good position to identify meaningful occupations with patients that can be adapted so that they are safe to be used in seclusion. Maintaining a person-centered approach in psychiatric inpatient settings has been shown to increase patient satisfaction and occupational performance (Schindler, Citation2010).

There is a need for further research to explore the role of OT within this specialist area. It would be beneficial to have a better understanding of the positive impact that OT has on service users in seclusion. It would also support OTs to have a deeper understanding of which interventions are the most effective.

Strengths and limitations

Due to a lack of OT research, this synthesis included interpreting research from other disciplines. A primary qualitative research design from an OT perspective could have better answered the research question but was outside the parameters of this study. Long term segregation is used to maintain safety in secure hospitals, however the literature search did not identify any research in this area, from any mental health disciplines, as a result only the seclusion element of the research question could be addressed.

Although the search strategy aimed to retrieve qualitative information from studies examining seclusion as experienced by patients, healthcare staff and carers, there was insufficient data from the healthcare staff and carer groups to include in this synthesis. The lack of triangulation resulting from this could have resulted in bias toward the patient experience, future research could examine the use of seclusion from staff perspectives to better understand their lived experience of seclusion as a therapeutic tool and necessity to reduce risk.

A strength of this review was the systematic approach taken to identify relevant research and the rigorous process used to analyze the data. Taking a qualitative synthesis approach has illustrated how there is a clear need for further research to inform the clinical practice of occupational therapists and other healthcare disciplines.

Conclusion

Despite the lack of specific literature relating to the role of occupational therapy in seclusion, through collating qualitative experiences across papers, this review has added to the understanding of the experiences of seclusion from a patient’s perspective. The Model of Human Occupation (Kielhofner, Citation2002) has provided the occupational lens to synthesize these perspectives and aid the consideration of ways in which the role of OT can be further developed. It has highlighted how important it is for OTs to continue working with patients whilst in seclusion thus maintaining the therapeutic relationship. OTs are skilled in using a person-centered approach which helps them to find occupations that are meaningful to patients and then facilitate their participation. Moreover, combining their unique skills in activity analysis and grading occupations with positive risk-taking enables them to adapt occupations so that they can be safely carried out in seclusion. OTs have expertise in adapting the environment and can therefore advocate for environmental changes, which may include sensory strategies which better meet the needs of the patient. OTs could also work with patients when they are stable to care plan their wishes in relation to occupational engagement should they be secluded, for example, their sensory preferences and occupations that are important to them. Overall, this illustrates the importance of taking a person-centered occupationally focussed approach in all aspects related to seclusion.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allikmets, S., Marshall, C., Murad, O., & Gupta, K. (2020). Seclusion: A patient perspective. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 41(8), 723–735. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2019.1710005

- Andersen, C., Kolmos, A., Andersen, K., Sippel, V., & Stenager, E. (2017). Applying sensory modulation to mental health inpatient care to reduce seclusion and restraint: A case control study. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 71(7), 525–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2017.1346142

- Askew, L., Fisher, P., & Beazley, P. (2020). Being in a seclusion room: The forensic psychiatric inpatients’ perspective. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 27(3), 272–280. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12576

- Baum, C. M., Christiansen, C. H., & Bass, J. D. (2015). The Person-Environment-Occupation-Performance (PEOP) Model. In C. M. Baum, C. H. Christiansen, & J. D. Bass (Eds.), Occupational therapy: Performance, participation and well-being. Slack.

- Boardman, J., & Roberts, G. (2014). Risk, safety and recovery (Implementing Recovery through Organisational Change Briefing). Centre for Mental Health. Retrieved from https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/Handlers/Download.ashx? IDMF=6461ca23-6a96-493b-a7c4-0411892ca6ef.

- Bowers, L., Cullen, A., Achilla, E., Baker, J., Khondoker, M., Koeser, L., Moylan, L., Pettit, S., Quirk, A., Sethi, F., Stewart, D., McCrone, P., & Tulloch, A. (2017). Seclusion and Psychiatric Intensive Care Evaluation Study (SPICES): Combined qualitative and quantitative approaches to the uses and outcomes of coercive practices in mental health services. Health Services and Delivery Research, 5(21), 1–116. https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr05210

- Brophy, L. M., Roper, C., Hamilton, B., Tellez, J., & McSherry, B. (2016). Consumers and carer perspectives on poor practice and the use of seclusion and restraint in mental health settings: Results from Australian focus groups. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 10, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-016-0038-x

- Care Quality Commission (CQC). (2015). Brief Guide: Seclusion Rooms. Retrieved January 29, 2021, from https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/CQC%20mental%20health%20brief%20guide%202%20-%20seclusion%20rooms.pdf.

- Care Quality Commission (CQC). (2019). Segregation in mental health wards for children and young people and in wards for people with a learning disability or autism. Newcastle. Retrieved January 15, 2021, from https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20191118_rssinterimreport_full.pdf.

- Chieze, M., Hurst, S., Kaiser, S., & Sentissi, O. (2019). Effects of seclusion and restraint in adult psychiatry: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 491. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00491

- Clarke, B., & Braun, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage Publications Ltd.

- Cooke, A., Smith, D., & Booth, A. (2012). Beyond PICO, the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), 1435–1443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312452938

- Copeland, M. E. (1997). Wellness recovery action plan. Peach Press.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2018). CASP Qualitative Checklist, CASP [Online]. Retrieved November 29, 2020, from https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf.

- Cromwell, F. S. (2013). Sensory integrative approaches in occupational therapy. [ebook] Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1677022/sensory-integrative-approaches-in-occupational-therapy-pdf.

- Crowe, M., Inder, M., & Porter, R. (2015). Conducting qualitative research in mental health: Thematic and content analyses. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 49(7), 616–623. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867415582053

- Cullen, A. E., Bowers, L., Khondoker, M., Pettit, S., Achilla, E., Koeser, L., Moylan, L., Baker, J., Quirk, A., Sethi, F., Stewart, D., McCrone, P., & Tulloch, A. D. (2018). Factors associated with use of psychiatric intensive care and seclusion in adult inpatient mental health services. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 27(1), 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796016000731

- Dike, C. C., Lamb-Pagone, J., Howe, D., Beavers, P., Bugella, B. A., & Hillbrand, M. (2021). Implementing a program to reduce restraint and seclusion utilization in a public- sector hospital: Clinical innovations, preliminary findings, and lessons learned. Psychological Services, 18(4), 663–670. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000502

- Dunn, W. (2007). Supporting children to participate successfully in everyday life by using sensory processing knowledge. Infants & Young Children, 20(2), 84–101. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.IYC.0000264477.05076.5d

- Estrella, M., Vatsya, M., Tsuda, M., & Roby, R. (2019). Exploring the experiences of individuals with serious mental illness in a modified treatment mall: Centralized off-unit programing with extended hours, a mixed methods study. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 35(4), 361–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2019.1648226

- Evatt, M., Scanlan, J., Benson, H., Pace, C., & Mouawad, A. (2016). Exploring consumer functioning in High Dependency Units and Psychiatric Intensive Care Units: Implications for mental health occupational therapy. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 63(5), 312–320. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12290

- Ezeobele, I. E., Malecha, A., Mock, A., Mackey-Godine, A., & Hughes, M. (2014). Patients’ lived seclusion experience in acute psychiatric hospital in the United States: A qualitative study. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 21(4), 303–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12097

- Fitzgerald, M. (2016). The potential role of the occupational therapist in acute psychiatric services: A comparative evaluation. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 23(11), 514–518. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijtr.2016.23.11.514

- Gardner, J., Olson, V., Castronovo, A., Hess, M., & Lawless, K. (2012). Using wellness recovery action plan and sensory based intervention: A case example. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 26(2-3), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.3109/07380577.2012.693650

- Goodman, H., Brooks, C., Price, O., & Barley, E. (2020). Barriers and facilitators to the effective de-escalation of conflict behaviours in forensic high-secure settings: A qualitative study. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 14, 59. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-020-00392-5

- Holmes, D., Kennedy, S. L., & Perron, A. (2004). The mentally ill and social exclusion: A critical examination of the use of seclusion from the patient’s perspective. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 25(6), 559–578. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840490472101

- Holmes, D., Murray, S. J., & Knack, N. (2015). Experiencing seclusion in a forensic psychiatric setting. Journal of Forensic Nursing, 11(4), 200–213. https://doi.org/10.1097/jfn.0000000000000088

- Javitt, D., & Freedman, R. (2015). Sensory processing dysfunction in the personal experience and neuronal machinery of schizophrenia. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(1), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13121691

- Kearns Murphy, C., & Shiel, A. (2019). Institutional injustices? Exploring engagement in occupations in a residential mental health facility. Journal of Occupational Science, 26(1), 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2018.1531780

- Kielhofner, G. (2002). A model of human occupation: Theory and application. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Kontio, R., Joffe, G., Putkonen, H., Kuosmanen, L., Hane, K., Holi, M. & Vallmaki, M. (2012). Seclusion and restraint in psychiatry: Patients' experiences and practical suggestions on how to improve practices and use alternatives. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 1(48), 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6163.2010.00301.x

- Lee, S., Kielhofner, G., Morley, M., Heasman, D., Garnham, M., Willis, S., Parkinson, S., Forsyth, K., Melton, J., & Taylor, R. (2012). Impact of using the Model of Human Occupation: A survey of occupational therapy mental health practitioners’ perceptions. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 19(5), 450–456. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2011.645553

- Liberati, A., Altman, D., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P., Ioannidis, J., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), W65–W94. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

- Meehan, T., Vermeer, C., & Windsor, C. (2000). Patients’ perceptions of seclusion: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 31(2), 370–377. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01289.x

- Mental Health Act. (1983). Retrieved December 13, 2021, from http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1983/20/contents.

- Mental Health Act. (1983). Code of Practice (2015) s.5, 6. Retrieved December 13, 2020, from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/435512/MHA_Code_of_Practice.PDF.

- Mental Health Act Use of Force Act. (2018). c. 27. Retrieved December 13, 2020, from https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2018/27/enacted.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analsys: The PRISMA statement. BMJ, 339, b2700. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Muskett, C. (2014). Trauma-informed care in inpatient mental health settings: A review of the literature. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 23(1), 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12012

- National Association of Psychiatric Intensive Care Units. (2017). Design guidance for psychiatric intensive care units. NAPICU International Press.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2015). Violence and aggression: Short term management in mental health, health and community settings (NICE guideline NG10). Retrieved January 10, 2021, from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng10.

- O’Connell, M., Farnworth, L., & Hanson, E. (2010). Time use in forensic psychiatry: A naturalistic inquiry into two forensic patients in Australia. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 9(2), 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2010.499558

- Royal College of Occupational Therapists (RCOT). (2017a). Occupational therapists’ use of occupation-focused practice in secure hospitals. Second edition. Retrieved February 12, 2021, from https://www.rcot.co.uk/practice-resources/rcot-practice-guidelines/secure-hospitals.

- Royal College of Occupational Therapists (RCOT). (2017b). Occupational therapy evidence, adult mental health. Royal College of Occupational Therapists.

- Royal College of Occupational Therapists (RCOT). (2018). Embracing risk; enabling choice. Guidance for occupational therapists. Third edition. Retrieved February 25, 2021, from https://www.rcot.co.uk/sites/default/files/RCOT%20Embracing%20Risk%20FINAL%20WEB_0.pdf.

- Savin-Baden, M., & Major, C. H. (2010). New approaches to qualitative research: Wisdom and Uncertainty. [ebook] Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1608687/new-approaches-to-qualitative-research-wisdom-and-uncertainty-pdf.

- Schindler, V. (2010). A client-centred, occupation-based occupational therapy programme for adults with psychiatric diagnoses. Occupational Therapy International, 17(3), 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.291

- Sherwood, W. (2021). Perspectives on the Vona du Toit model of creative ability, 1st ed. International Creative Ability Network.

- Social Care, Local Government and Care Partnership Directorate. (2014). Positive and Proactive Care: Reducing the Need for Restrictive Interventions. Retrieved August 23, 2021, from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/300293/JRA_DoH_Guidance_on_RP_web_accessible.pdf.

- Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust. (2019). Seclusion and long-term segregation policy. Retrieved January 10, 2021, from www.southernhealth.nhs.uk/_resources/assets/attachment/full/0/109537.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2-lx5WRTq0Qky5LFAwxw1o.

- Stomski, N., & Morrison, P. (2017). Participation in mental healthcare: A qualitative meta-synthesis. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 11, 67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-017-0174-y

- Sustere, E., & Tarpey, E. (2019). Least restrictive practice: Its role in patient independence and recovery. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 30(4), 614–629. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2019.1566489

- Sutton, D., Wilson, M., Van Kessel, K., & Vanderpyl, J. (2013). Optimizing arousal to manage aggression: A pilot study of sensory modulation. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 22(6), 500–511. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12010

- Tully, J., McSweeney, L., Harfield, K., Castle, C., & Das, M. (2016). Innovation and pragmatism required to reduce seclusion practices. CNS Spectrums, 21(6), 424–429. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852916000481

- West, M., Melvin, G., McNamara, F., & Gordon, M. (2017). An evaluation of the use and efficacy of a sensory room within an adolescent psychiatric inpatient unit. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 64(3), 253–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12358

- Whiteford, G., Jones, K., Weekes, G., Ndlovu, N., Long, C., Perkes, D., & Brindle, S. (2020). Combatting occupational deprivation and advancing occupational justice in institutional settings: Using a practice-based enquiry approach for service transformation. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 83(1), 52–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022619865223

- Wiglesworth, S., & Farnworth, L. (2016). An exploration of the use of a sensory room in a forensic mental health setting: Staff and patient perspectives. Occupational Therapy International, 23(3), 255–264. https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.1428

- Wood, L., Williams, C., Billings, J., & Johnson, S. (2019). The role of psychology in a multidisciplinary psychiatric inpatient setting: Perspective from the multidisciplinary team. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 92(4), 554–564. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12199

- Wright, L., Bennett, S., & Meredith, P. (2020). “Why didn’t you just give them PRN?”: A qualitative study investigating the factors influencing implementation of sensory modulation approaches in inpatient mental health units. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29(4), 608–621. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12693

- Yakov, S., Birur, B., Bearden, M., Aguilar, B., Ghelani, K., & Fargason, R. (2018). Sensory reduction on the general milieu of a high-acuity inpatient psychiatric unit to prevent use of physical restraints: A successful open quality improvement trial. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 24(2), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078390317736136

Appendix A.

SPIDER tool for development of research question

The SPIDER mnemonic has been designed to aid qualitative research question development and was selected rather than PICO due to the lack of comparator and due to the subjectivity of the outcome, in qualitative research there is sometimes no outcome and the objective is to simply gain insight. The table illustrated below demonstrates the use of SPIDER in this instance.

Table A1. llustrating development of research question using SPIDER.

Appendix B.

Articles excluded after full text screening

Appendix C.

Table illustrating strengths and limitations in papers selected for review

Appendix D.

Theme development

Third row illustrating all themes drawn from research, fourth row illustrating finalized themes. Third row themes were either able to be incorporated into fourth row themes, or there was not enough data to complete synthesis on the topic.