Abstract

This scoping review aimed to establish if horticulture is an occupation-based intervention in mental health recovery. Horticulture as an occupation was found to aid recovery by facilitating the social aspect of person-driven recovery based on strengths and responsibility. Where occupational therapists were able to use horticultural therapy, they did so in a client-centred and recovery-oriented outcome way. The findings support occupation-based and recovery-oriented occupational therapy practice. Use of recovery-oriented outcome measures and systematic appraisal of evidence are required to enhance applicability of these findings.

Introduction

Horticultural therapy

Nature-based therapies, or green care, are increasingly utilized in mental health care (Ascencio, Citation2019; Clatworthy et al., Citation2013). Within this domain, horticultural therapy is a gardening-based intervention, which involves use of plants and horticulture-based activities by a trained professional as a means of achieving clinical or therapeutic goals (Cipriani et al., Citation2017; Clatworthy et al., Citation2013; Kam & Siu, Citation2010). Horticultural therapy differs from therapeutic horticulture in that it: a) involves active engagement of the participant; b) is designed to achieve therapeutic goals; c) is facilitated by a professional as part of an established intervention for service users (American Horticultural Therapy Association, Citation2022), whereas therapeutic horticulture is defined as “interventions designed to enhance wellbeing through the use of plants and horticulture” Clatworthy et al. (Citation2013). Horticultural therapy can be facilitated by horticultural therapists, occupational therapists, recreational therapists, social workers, and physical therapists (Cipriani et al., Citation2017). However, the use of horticulture in occupational therapy retains its focus on the use of horticulture as a structured occupation-based intervention which has meaning to the client.

Horticulture as an occupation-based intervention

Occupational therapy is congruent with the three aforementioned of horticultural therapy. Firstly, both occupational and horticultural therapy are based on active engagement in gardening. Engagement in meaningful occupation is at the heart of occupational therapy theory and practice (American Occupational Therapy Association, Citation2014). Viewed through the occupational lens, gardening is a meaningful occupation that is believed to facilitate well-being through doing (i.e., active engagement in gardening), being in nature and with others, becoming (i.e., developing a positive sense of self, developing skills and new identity), and belonging to the social group and the wider community through engagement in an ordinary occupation devoid of stigma (Joyce & Warren, Citation2016; Wilcock, Citation1998; York & Wiseman, Citation2012). Hence, engagement in gardening as a therapeutic medium is the essence of occupation-based practice (Fisher, Citation2014). Occupation-based interventions are strongly linked to professional identity and are defined as “those where the occupational therapist uses engagement in occupation as the therapeutic agent of change” (Fisher, Citation2014, p. 98). For instance, “putting the occupation back in occupational therapy” was used in the title of a study investigating occupational therapists’ use of gardening as an intervention (Wagenfeld & Atchison, Citation2014). Secondly, setting therapeutic goals is inherent within the occupational therapy process and intervention (American Occupational Therapy Association, Citation2014). This results in the use of occupational and horticultural therapies as structured and goal-directed interventions. Finally, occupational therapists are evidenced to facilitate gardening-based group interventions within the scope of their practice in a client-centred and participant-led manner, which are associated with enhanced therapeutic benefit (Joyce & Warren, Citation2016; Wagenfeld & Atchison, Citation2014).

Occupation-based recovery

Meaningful occupational engagement and client-centred practice are believed to facilitate recovery (Arblaster et al., Citation2019; Doroud et al., Citation2015). Globally, recovery-orientation is the aspired standard of delivery of mental health services (Government of Ireland, Citation2020; Leamy et al., Citation2011; Mental Health Commission, Citation2007; World Health Organisation, Citation2021). Rather than the clinical model of symptom-free normality, recovery is a unique journey of regaining a fulfilling and meaningful life regardless of whether symptoms persist (Slade et al., Citation2014; World Health Organisation, Citation2021). In line with occupational therapy theory, recovery is supported by engagement in personally meaningful and socially valued occupations (Doroud et al., Citation2015; Hancock et al., Citation2015; Nugent et al., Citation2017). Thus, recovery through occupation led to recovery-oriented occupational therapy practice and a term ‘occupational recovery’ being coined (Doroud et al., Citation2015, p. 389). Furthermore, Doroud et al. (Citation2015) asserts that occupational engagement and recovery ‘speak the same language’ (p. 388) and that recovery can be conceptualized through the occupational doing, being, becoming and belonging as ‘re-uniting doing, being oneself and finding a sense of belonging, so as to become the person one aspires to be’ (p. 388). The congruence between recovery-oriented practice and occupational therapy are elucidated by client-centredness, choice, self-determination, and therapeutic relationships (Nugent et al., Citation2017; Slade et al., Citation2014).

Horticultural therapy and recovery linked by occupation

Both horticultural therapy and recovery appear to have occupation in common. Namely, horticultural therapy is based on horticultural occupations as a therapeutic medium for positive change (American Horticultural Therapy Association, Citation2022). Recovery has as its focus living a meaningful and purposeful life and supporting individuals in their recovery journey using occupation as a means for change. (Rebeiro Gruhl, Citation2005). Thus, the focus of this paper is on the scope of horticulture as a therapeutic medium and its relationship to recovery in mental health and occupational therapy.

Gap in knowledge

Largely, research on horticultural therapy has not adopted a recovery-oriented approach, evidenced by using mostly symptom-based outcome measures (Sinnott & Rowlís, Citation2021). Research that is not informed by recovery has limited potential to inform recovery-oriented practice. Inconsistent use of the term and many definitions of recovery is an acknowledged barrier in a research context (Meehan et al., Citation2008, as cited in Ellison et al., Citation2018; Leamy et al., Citation2011). For the purpose of this review, ten guiding principles of recovery developed by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration, Citation2012) were utilized, namely: holistic, peer support, respect, hope, person driven, strengths/responsibility, culture, addresses trauma, relational, and many pathways. It is one of the most accepted conceptualisations of recovery (Ashford et al., Citation2019). Additionally, definitions, synonyms, and keywords for each of the ten guiding principles of recovery were established as concordant with empirical and policy definitions, distinguishable, and self-exclusive in a systematic review (Ellison et al., Citation2018).

Previous reviews on horticultural interventions incorporated both horticultural therapy and therapeutic horticulture (Clatworthy et al., Citation2013; Sempik et al., Citation2003, as cited in Clatworthy et al., Citation2013) or included populations with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (Cipriani et al., Citation2017; Tu, Citation2022), children, stroke survivors, or the general population (Tu, Citation2022). A previous review on occupational engagement and recovery found that a considerable number of studies focused on work as a meaningful occupation, with the need identified to explore how other occupations could foster recovery (Argentzell et al., Citation2012, as cited in Doroud et al., Citation2015). As a result, no review has attempted to establish the potential of horticultural therapy as an occupation-based intervention to facilitate recovery within the scope of occupational therapy practice in mental health.

Aim

The objective of this review was to scope out the evidence on horticulture as a therapeutic medium. A second objective was to examine the evidence for horticulture/gardening as an occupation-based intervention in mental health and its relationship to recovery and occupational therapy. (Aromataris & Munn, Citation2020).

Review questions

What is the scope of horticultural therapy in mental health practice?

How is the impact of horticultural therapy on recovery measured?

Do occupational therapy interventions based upon horticulture facilitate the recovery of individuals with mental health conditions?

Inclusion criteria

Through utilizing the PCC (Population, Concept, Context) framework, the following key elements were used to conceptualize the review focus and inform the eligibility criteria (Aromataris & Munn, Citation2020).

Population

Studies were included if the participants were adults (over 18 years of age) with a mental health diagnosis or were identified as having a mental health condition, whether any mental health conditions were specifically stated or not. Studies of participants with dementia, Alzheimer’s disease or cognitive impairment were excluded. Studies on general (non-clinical) population and their mental well-being were also excluded. The selected population is intended to be representative of typical client population within adult mental health services.

Concept

The definition of horticultural therapy was used as an inclusion criterion (American Horticultural Therapy Association, Citation2022). Studies that did not specify any clinical goals in relation to horticultural therapy were included if the intervention was provided by a professional to service users as an established intervention.

Context

Studies were included regardless of context.

Types of sources of evidence

Any existing literature could be included in a scoping review (Aromataris & Munn, Citation2020). Other reviews or meta-analysis were assessed against eligibility criteria. No studies were excluded due to their level of evidence in order to allow for the inclusion of any and all evidence relevant to the research questions. Grey literature was excluded from the review. Grey literature may include: theses and dissertations, reports, blogs, technical notes, non-independent research or other documents produced and published by government agencies, academic institutions or non-commercially operated databases (Aromataris & Munn, Citation2020). It was excluded due to limited applicability to informing practice and the sufficient number of identified empirical literature.

Methods

This scoping review follows the Joanne Briggs Institute (JBI) method for scoping reviews (Aromataris & Munn, Citation2020). In accordance with the JBI method – and to increase the methodological rigor and relevance to clinical decision-making – the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) was used for reporting of this scoping review (Tricco et al., Citation2018). The objectives, eligibility criteria, and methods for this scoping review were agreed upon by all authors and documented in an unpublished protocol in advance.

Search strategy

The search strategy aimed to locate literature published in full regardless of the time of publication. The authors included sources of evidence published in English only. Background reading and preliminary searches were used to determine the search terms. A preliminary search using occupational therapy as a search term, identified only six studies that mentioned occupational therapists as facilitators and therefore it was decided given the aims of the review, that the terms for the search would be broadened. Additionally, valuable data pertinent to the recovery principles could have been lost if the search was limited to occupational therapy only; and no differences, if any, could be identified between facilitation of horticultural therapy or use of outcome measures by occupational therapists and other professionals. With support of the subject librarian, search terms were developed and seven electronic databases searched on the 14th of June 2022 using the platform of databases available to Trinity College Dublin. This date for running searches was determined by the timeframe of completing this scoping review. The following databases were searched based on the relevance to the review topic: EMBASE, Medline, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Web of Science – Core Collection, Scopus, Google Scholar. Reference lists of other relevant reviews were searched. As an example, the following search terms were adapted for searching EMBASE: ‘horticultural therapy’/exp; ((horticultur* OR garden*) NEAR/3 (therap* OR program* OR rehabilitation)):ti,ab,kw; ((‘nature-based’ OR 'garden-based’ OR ‘green-based’ OR ‘horticultur* based’) NEAR/3 (rehab* OR intervention* OR therap* OR program*)):ti,ab,kw; (‘plant-based activit*’ OR ‘rehabilitation greenhouse*’ OR ‘wander garden*’ OR ‘healing garden*’ OR ‘Social and therapeutic horticulture’ OR ‘Social and therapeutic garden*’ OR ‘green care’ OR ‘socio horticulture’ OR ‘care farm*' OR ‘eco therapy’ OR ecotherap* OR ‘green therap*’ OR ‘green intervention*’):ti,ab,kw; #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4; ‘mental health’/exp OR ‘mental health recovery’/exp OR ‘mental diseases therapy’/exp OR ‘mental disease’/exp OR ‘mental health care’/exp; (('mental health’ OR ‘mental disease*' OR ‘mental illness*' OR ‘mental disorder*' OR ‘psychiatric illness*’ OR ‘psychiatric disorder*’ OR ‘psychiatric condition*') NEAR/4 (recover* OR rehab* OR intervention* OR program* OR therap*)):ti,ab,kw; ‘depression’/exp/dm_rh OR ‘schizophrenia’/exp/dm_rh; ((psychosis OR depression OR schizophreni* OR anxiety OR bi-polar OR bipolar) NEAR/4 (recover* OR rehab* OR intervention* OR program* OR therap*)):ti,ab,kw; #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9; #5 AND #10.

Study screening and selection

Following the search, the identified records were collated by the subject librarian into the EndNote library with duplicates removed. The records were then uploaded into Covidence systematic review software where any additional duplicates were manually removed. The titles and abstracts were then screened against the inclusion criteria by the first and second authors. Full texts of 77 studies were retrieved and assessed in detail against the inclusion criteria by the same two authors. Any conflicts at any stage of the selection process were resolved by systematic referral to the eligibility criteria and discussion between the two authors or with the third author.

Data extraction

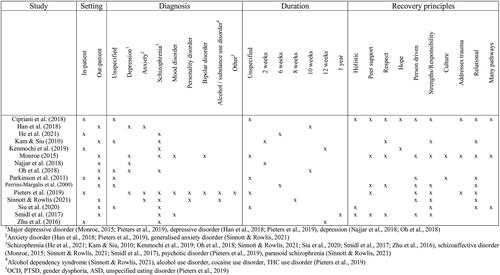

A charting table for data extraction was informed by the suggestions for standard extraction forms in the JBI method (Aromataris & Munn, Citation2020). The pilot testing extraction of the first two sources by the first and second authors was performed. Following resolution of inconsistencies, all data relevant to inform this scoping review’s objective and questions was extracted by the first author (Aromataris & Munn, Citation2020). The complete charting table was reviewed by all authors. All variables and characteristics for which data was sought are presented in tabular format ().

Table 1. Characteristics of Included Sources of Evidence.

Data analysis and presentation

Extracted data was analyzed using framework synthesis. Framework synthesis involves preliminary identification of themes, or a framework, against which to map and configure the findings from the quantitative and qualitative studies (Carroll et al., Citation2011). In this case, the ten recovery principles constitute the preconceived framework against which a summary of extracted data was mapped (Aromataris & Munn, Citation2020; Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration, Citation2012). This framework synthesis involved basic coding of data to the recovery principles and descriptive qualitative content analysis presented under each recovery principle. That way, the benefits of horticultural therapy were viewed through the recovery lens. Extracted data, which could not be mapped under the recovery principles, informed the first question of this review.

Results

Study inclusion

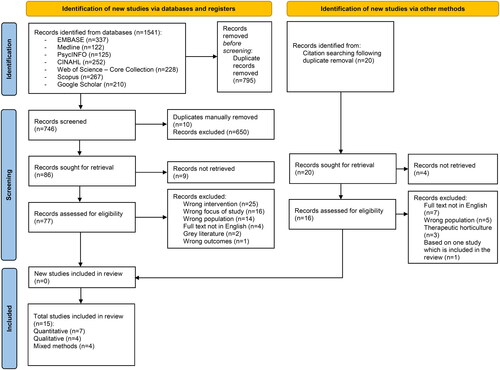

A total of 1561 records were identified during the searches; including 20 records identified through hand searching the reference lists of relevant reviews, with none of the latter (i.e., 20 records) subsequently meeting the eligibility criteria. The search results and study selection, including the reasons for exclusion, are depicted in the PRISMA flow diagram (). A total of 15 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included for data extraction and review.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram. From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

Characteristics of included studies

All of the included sources were published between 2000 and 2021. However, the majority (n = 12, 80%) of the studies were published from 2015 onward, 3 studies (20%) were published prior to this (Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000; Kam and Siu, Citation2010; Parkinson et al., Citation2011). The studies were conducted in the following countries: the USA (n = 5, Cipriani et al., Citation2018; Monroe, Citation2015; Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000; Pieters et al., Citation2019; Smidl et al., Citation2017), China (n = 4, He et al., Citation2021; Kam & Siu, Citation2010; Siu et al., Citation2020; Zhu et al., Citation2016), South Korea (n = 2, Han et al., Citation2018; Oh et al., Citation2018), Japan (n = 1, Kenmochi et al., Citation2019), Iran (n = 1, Najjar et al., Citation2018), United Kingdom (n = 1, Parkinson et al., Citation2011), and Ireland (n = 1, Sinnott & Rowlís, Citation2021). Seven studies used quantitative (Han et al., Citation2018; He et al., Citation2021; Kam & Siu, Citation2010; Kenmochi et al., Citation2019; Najjar et al., Citation2018; Oh et al., Citation2018; Zhu et al., Citation2016), four used qualitative (Cipriani et al., Citation2018; Monroe, Citation2015; Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000; Pieters et al., Citation2019), and four used mixed methods (Parkinson et al., Citation2011; Sinnott & Rowlís, Citation2021; Siu et al., Citation2020; Smidl et al., Citation2017). Seven studies (46.7%) were conducted or coauthored by occupational therapists (Cipriani et al., Citation2018; Kam & Siu, Citation2010; Kenmochi et al., Citation2019; Parkinson et al., Citation2011; Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000; Sinnott & Rowlís, Citation2021; Smidl et al., Citation2017).

Review findings

The results of ten out of 15 included studies were suitable for mapping to the recovery principles (). First, a descriptive summary of the findings regarding the scope of horticultural therapy is presented. Second, findings regarding recovery-oriented research, including outcome measures, are presented. Finally, the benefits of horticultural therapy, which have been mapped to the recovery principles, are presented.

Table 2. Horticultural Therapy and the Recovery Principles.

Scope of horticultural therapy of relevance to occupational therapy

Horticultural therapy usually took place in either in-patient (n = 6) or out-patient (n = 6) mental health facilities, with the exception of farm (Han et al., Citation2018; Oh et al., Citation2018), sheltered workshop (Kam & Siu, Citation2010), community allotment (Parkinson et al., Citation2011), and rehabilitation clubhouse (Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000) settings. The study by Parkinson et al. (Citation2011) involved multiple settings. Service users of horticultural therapy had diverse mental health conditions (), with four studies focusing solely on individuals with schizophrenia (He et al., Citation2021; Kenmochi et al., Citation2019; Oh et al., Citation2018; Zhu et al., Citation2016) and one study – on older adults with mental health problems (Han et al., Citation2018). Horticultural therapy was a group intervention in all reviewed studies.

Horticultural therapy consisted of various indoor and outdoor horticultural activities as well as horticulture-based crafts. Some horticultural therapies involved growing edible plants (Han et al., Citation2018; He et al., Citation2021; Monroe, Citation2015; Oh et al., Citation2018; Smidl et al., Citation2017), cooking and tasting (Kenmochi et al., Citation2019; Siu et al., Citation2020; Zhu et al., Citation2016), and selling garden produce at community sales (Cipriani et al., Citation2018). In one instance, the service users were reimbursed for their participation in horticultural therapy at a sheltered workshop (Cipriani et al., Citation2018).

Horticultural therapy sessions typically lasted between 45 and 120 minutes one to three times a week, except for one daily horticultural therapy programme (Kam & Siu, Citation2010). Participation in horticultural therapy was generally from two weeks to 12 weeks in total, with one programme taking place over one year (Smidl et al., Citation2017). Some studies emphasized the need for longer duration of horticultural therapy interventions (He et al., Citation2021; Kam & Siu, Citation2010; Kenmochi et al., Citation2019).

Six of the horticultural therapy groups were facilitated or co-facilitated by occupational therapists (Cipriani et al., Citation2018; Kam & Siu, Citation2010; Pieters et al., Citation2019; Sinnott & Rowlís, Citation2021) or graduate occupational therapy students (Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000; Smidl et al., Citation2017), while others were facilitated by horticultural therapists (He et al., Citation2021; Kenmochi et al., Citation2019; Oh et al., Citation2018; Siu et al., Citation2020) or other professionals (Han et al., Citation2018; Monroe, Citation2015; Zhu et al., Citation2016).

Some horticultural therapies had pre-determined objectives for each session, including specific activities, which the participants were instructed to follow (Cipriani et al., Citation2018; Kam & Siu, Citation2010; Kenmochi et al., Citation2019; Najjar et al., Citation2018; Siu et al., Citation2020; Zhu et al., Citation2016) or which were demonstrated by the facilitators (Han et al., Citation2018; Oh et al., Citation2018). One horticultural therapy programme included a demonstration, a written directory of tasks, work in pre-arranged pairs, and instruction during completion of tasks (He et al., Citation2021). Conversely, other studies facilitated the participants to choose activities or how to perform them (Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000; Pieters et al., Citation2019) or participate in the planning process of horticultural therapy (Sinnott & Rowlís, Citation2021; Smidl et al., Citation2017). It was described as a ‘participatory approach’ and involved the participants identifying goals for each session, making plans and delegating roles and tasks between themselves and the facilitators (Monroe, Citation2015).

Recovery measures

Six studies adopted a recovery-oriented or recovery-informed approach to goal-setting, outcome measures, or study design, such as:

measuring achievement of recovery goals as an outcome (Cipriani et al., Citation2018; Sinnott & Rowlís, Citation2021; Smidl et al., Citation2017);

hypothesizing horticultural therapy as a recovery-oriented intervention, particularly in relation to alleviating hopelessness (Kenmochi et al., Citation2019), facilitating motivational change and hope (Parkinson et al., Citation2011), meaningful occupations which integrate mental illness and recovery (Pieters et al., Citation2019), and peer support (Sinnott & Rowlís, Citation2021);

adapting a recovery-specific measure for the follow-up survey (Smidl et al., Citation2017).

Holistic

Recovery encompasses one’s ‘whole life, including mind, body, spirit, and community’ (Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration, Citation2012, p. 5). A few studies identified the holistic nature of horticultural therapy, such as having social, physical, psychological, and spiritual benefits and addressing several areas of occupation concurrently, such as social participation and productivity (Cipriani et al., Citation2018; Siu et al., Citation2020; Smidl et al., Citation2017).

Peer support

Peer support and connectedness with peers facilitate recovery (Ellison et al., Citation2018; Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration, Citation2012). Horticultural therapy facilitated achievement of a recovery goal of having a support system to help one recognize their mistakes and make improvements (Cipriani et al., Citation2018), to learn to delegate tasks and provide emotional support to other participants (Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000), and to learn from others (Pieters et al., Citation2019). Participants tended to value the social group and peer support as part of horticultural therapy (Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000).

Respect

Recovery is based on respect, including self-acceptance, a positive self-identity, and regaining belief in oneself (Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration, Citation2012). Participants of horticultural therapy reported improved self-esteem and confidence and demonstrated higher levels of respect for peers and facilitators (Cipriani et al., Citation2018; Kam & Siu, Citation2010; Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000). Participants derived a sense of pride and being respected (Kam & Siu, Citation2010; Smidl et al., Citation2017) as well as having proof that they could be independent (Cipriani et al., Citation2018) from participation in horticultural therapy. They also realized their significance and the worth of their contribution to the horticultural therapy group (Monroe, Citation2015; Smidl et al., Citation2017). Additionally, participants were reported to experience enhanced self-acceptance through accepting their feelings (Monroe, Citation2015).

Hope

Hope is the foundation and ‘the catalyst of the recovery process’ (Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration, 2012, p. 4), including optimism and the belief that recovery is real (Ellison et al., Citation2018). Horticultural therapy facilitated achievement of an individual recovery goal of having a more optimistic and hopeful attitude and positive outlook (Cipriani et al., Citation2018). However, no significant change in the sense of hope or perspectives for the future or feeling of hopelessness was found (Kenmochi et al., Citation2019).

Person-driven

This principle is foundational to recovery and encompasses self-determination, self-direction, and autonomy by facilitating individuals to define their own goals, lead, and exercise choice over the services that support their recovery (Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration, 2012). Therapeutic relationships form part of person-driven recovery (Ellison et al., Citation2018).

In one qualitative study, five out of eight participants identified their recovery goals, either independently or when prompted, and provided examples of how horticultural therapy facilitated achievement of their recovery goals (Cipriani et al., Citation2018). Participants in the study by Sinnott and Rowlís (Citation2021) were supported to identify two to three individual recovery-oriented SMART goals, with the total 12 out of 15 recovery goals being subsequently achieved as a result of horticultural therapy.

Participants also reported personal growth and developing and valuing therapeutic relationships with staff, including occupational therapy students (Cipriani et al., Citation2018; Parkinson et al., Citation2011; Pieters et al., Citation2019; Smidl et al., Citation2017). Horticultural therapy was identified to be ‘specifically tailored to meet the needs of each individual client, based on their diagnosis and recovery goals’ (Cipriani et al., Citation2018, p. 251). Other horticultural therapies emphasized the participatory process, namely the participants informing the development and running of the horticultural therapy group (Monroe, Citation2015). It was noted that participants took more initiative as the time went on (Smidl et al., Citation2017). In some cases, it involved the participants determining the roles within the group for themselves and the facilitators (Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000). Additionally, they had the opportunity to show creativity and make choices based on their thoughts and desires, which is embodied by these quotes: ‘I enjoyed the sense of choice during activities,’ ‘We had choices all the time’ (Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000, p. 25). The participants valued being able to choose activities during horticultural therapy (Pieters et al., Citation2019), which was associated with enhanced satisfaction with the end-product (Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000). Pieters et al. (Citation2019) found that having two facilitators allowed for more participant engagement as one therapist could focus on the group process while the other devoted more attention to one-to-one interactions.

Strengths/Responsibility

Recovery is built on personal strengths, acquisition of skills and coping strategies, and responsibility for active participation in recovery (Ellison et al., Citation2018; Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration, 2012). Some individual recovery goals related to skill acquisition or structure (Sinnott & Rowlís, Citation2021). Horticultural therapy offered opportunities to learn new skills, improve work performance, and experience challenges (Kam & Siu, Citation2010; Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000; Pieters et al., Citation2019; Siu et al., Citation2020). As a result of horticultural therapy, participants acquired new horticulture-related vocational skills and professional habits, such as punctuality and having responsibilities (Cipriani et al., Citation2018). Participants reported using nature-based metaphor as a coping strategy to manage negative thoughts, for instance, conceptualizing the trees swaying in the wind as ‘being flexible and adjusting to what life throws at us’ (Monroe, Citation2015, p. 36; Pieters et al., Citation2019). Horticultural therapy also facilitated a feeling of being productive, assuming personal responsibility to care for plants, and personal mastery despite low uptake of activities during the maintenance phase, such as watering and weeding, among the participants of the one-year-long horticultural therapy programme (Pieters et al., Citation2019; Smidl et al., Citation2017).

Culture

‘Recovery is culturally-based and influenced’ (Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration, Citation2012, p. 6). Some participants appreciated nature representing the cycle of life, planting and harvesting rituals, growing food more than flowers, and the work role standards of some horticultural therapy groups, including getting paid (Cipriani et al., Citation2018; Monroe, Citation2015; Parkinson et al., Citation2011).

Addresses trauma

Trauma-informed care promotes recovery and safety through trust and collaboration (Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration, 2012). During horticultural therapy, participants developed therapeutic relationships with the facilitators based on trust (Cipriani et al., Citation2018; Pieters et al., Citation2019) and benefited from the opportunity to build trusting relationships with other participants (Monroe, Citation2015).

Relational

Relational is the social aspect of recovery, including non-peer relationships and the wider community (Ellison et al., Citation2018). Some of the individual recovery goals related to the social domain of the service users’ lives and their individual recovery journey (Sinnott & Rowlís, Citation2021). Horticultural therapy offered opportunities for socialization (Cipriani et al., Citation2018; Smidl et al., Citation2017), facilitated extension of social networks (Kam & Siu, Citation2010), development of positive relationships and interdependence among the participants (Monroe, Citation2015; Parkinson et al., Citation2011). Improved social skills and self-confidence among the participants were noted (Kam & Siu, Citation2010), including enjoyment of collective ownership of the garden (Monroe, Citation2015). The participants valued the social group, input of facilitators, social interactions, and a sense of community (Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000; Pieters et al., Citation2019). Sharing was prominent among the participants, including sharing of tools and end-products, and the sharing of memories, thoughts, and reflections (Cipriani et al., Citation2018; Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000; Smidl et al., Citation2017). Some participants also shared the end-products with family and friends (Siu et al., Citation2020). One study found no significant change in social exchange following a standardized horticultural therapy programme (Siu et al., Citation2020). Despite the social environment of horticultural therapy being facilitative of recovery, it was found to require careful facilitation (Parkinson et al., Citation2011).

Many pathways

Recovery is a non-linear, unique, and subjective journey, which can occur even though symptoms reoccur (Ellison et al., Citation2018). During horticultural therapy, participants learned to tolerate depression, anxiety, and loss of a loved one by conceptualizing them as cycles that would pass while allowing themselves to experience these feelings (Monroe, Citation2015). Participants also learned resilience and acceptance of challenges through metaphor: ‘Outdoor plants could grow better and stronger after severe storms’ (Siu et al., Citation2020, p. 10). The therapeutic value of horticultural therapy was encapsuled in that it ‘doesn’t make the delusions go away but can help [the participants] function in spite of the delusions’ (Cipriani et al., Citation2018, p. 250) as it provided a place for ‘quiet reflection’ and the ‘development of close relationships with other workers.’

Discussion

The findings regarding the scope of horticultural therapy in mental health are in line with previous reviews (Cipriani et al., Citation2017). The considerable representation of occupational therapists, either as facilitators or researchers, supports the use of horticulture as a therapeutic medium within the scope of occupational therapy practice in mental health. There is evidence that horticulture can be used as a means and an end to enable service users to embark and stay on their recovery journey. It also challenges the critique by Wagenfeld and Atchison (Citation2014) of insufficient evidence produced by occupational therapists to support the use of gardening as a therapeutic occupation and as basis for intervention.

The findings of this review show that horticultural therapy can potentially support recovery. Horticultural therapy appears to address all recovery principles to some extent. The three most prominent ones were: ‘person driven,’ ‘strengths/responsibility,’ and ‘relational.’ The relational (i.e., social) aspect of recovery appeared to be supported by the group format and therapeutic relationships among the participants and between the facilitators and participants. This is in line with previous literature on occupational therapy and recovery-oriented practice. Namely, the social connectedness of being with others and belonging, as previously discussed in relation to gardening, are believed to contribute the most to the meaning that people recovering from mental health conditions derive from occupational engagement (Hancock et al., Citation2015). The ‘strengths/responsibility’ aspect relates to skill acquisition, routine, and responsibility of attendance and care for plants. This is supported by the holistic and strengths-based approach to recovery focused on personal growth (Ashford et al., Citation2019).

Occupational therapy and recovery-oriented practice both promote client-centred practice at the heart of person-driven approach to therapy (Smidl et al., Citation2017). Majority of occupational therapists who use gardening as an intervention identified that they do so because it supports client-centredness and fosters a sense of accomplishment (Wagenfeld & Atchison, Citation2014). Additionally, York and Wiseman (Citation2012) noted how gardening, as an occupation, can support personal agency and the creation of a new sense of self. However, the somewhat prescriptive or standardized nature of facilitation of horticultural therapy by providers other than occupational therapists (Han et al., Citation2018; He et al., Citation2021; Najjar et al., Citation2018; Oh et al., Citation2018; Siu et al., Citation2020; Zhu et al., Citation2016) is contrary to recovery-oriented and client-centred practice where the focus was upon the remediation of psychological symptoms. Therefore, facilitation of horticultural therapy varied in its adoption of recovery orientation. While the two studies where horticultural therapy was facilitated by occupational therapists (Cipriani et al., Citation2018; Kam & Siu, Citation2010), included set objectives and gardening activities, the rest of occupational therapy facilitators adopted a markedly participant- or client-led approach, such as involving service users in decision-making, planning and choice of gardening activities (Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000; Pieters et al., Citation2019; Sinnott & Rowlís, Citation2021; Smidl et al., Citation2017). The only other facilitator described to endorse a participatory approach was an unspecified therapist (Monroe, Citation2015). Joyce and Warren (Citation2016) emphasized the impact of thoughtful ‘person-centred, member-led ethos and facilitation approach’ (p. 10) as vital to the success of a gardening group in supporting well-being. Indeed, co-production is one of four principles underpinning the recovery framework, embodied by the role of service users in the design, delivery and evaluation of services (Health Service Executive, Citation2018).

Limited amount of data was mapped to the recovery principles of ‘addresses trauma,’ ‘culture,’ and ‘peer support,’ which is in line with previous findings, namely that these recovery principles are not frequently addressed in the literature irrespective of field of study (Ellison et al., Citation2018). Similarly, ‘holistic’ is less frequently mentioned in the literature. From the studies reviewed, only three explicitly identified the benefits of horticultural therapy as holistic (Cipriani et al., Citation2018; Siu et al., Citation2020; Smidl et al., Citation2017), despite multiple other studies reporting on psychological, physical, and social benefits separately (e.g., Han et al., Citation2018; He et al., Citation2021; Kenmochi et al., Citation2019). Future studies could address this identified gap in knowledge.

As a limited number of reviewed studies measured recovery specifically or utilized recovery-specific measures, the impact of horticultural therapy on recovery does not appear to be adequately measured. Additionally, there is insufficient evidence currently available on the long-term effects of horticultural therapy as only two studies utilized follow-up measures (Siu et al., Citation2020; Smidl et al., Citation2017), which is in line with previous literature (Clatworthy et al., Citation2013). Wagenfeld and Atchison (Citation2014) noted the gap within occupational therapy in translating the use of gardening as an occupation-based intervention into measurable outcomes. Nevertheless, the six studies that were found to adopt a recovery-informed or recovery-oriented approach involved occupational therapists as facilitators and/or (co-)authors. Notably, four of them measured recovery as an outcome of their occupation-based horticultural therapy intervention (Cipriani et al., Citation2018; Sinnott & Rowlís, Citation2021; Smidl et al., Citation2017), including the use of one recovery-specific follow-up measure (Smidl et al., Citation2017). This finding supports the recovery-orientation of occupational therapy as a profession not only thorough facilitation of horticultural therapy as an occupation-based intervention, but also in contributing to recovery-oriented research.

Limitations

Only four studies clearly stated the therapeutic goals of horticultural therapy (Kam & Siu, Citation2010; Monroe, Citation2015; Siu et al., Citation2020; Smidl et al., Citation2017). Conceptual clarity would be increased if such details were included in any research on horticultural therapy. Additionally, the duration of horticultural therapy and/or diagnoses of participants were omitted from some studies (Cipriani et al., Citation2018; Kam & Siu, Citation2010; Monroe, Citation2015; Oh et al., Citation2018; Parkinson et al., Citation2011; Perrins-Margalis et al., Citation2000; Pieters et al., Citation2019; Siu et al., Citation2020). The findings of this review are limited by the literature available on the topic. Due to the nature of scoping reviews, quality of reviewed evidence was not appraised, which limits the applicability of the findings to practice (Aromataris & Munn, Citation2020). Only published empirical research in English was included.

Conclusion and recommendations

The use of horticulture is compatible with occupational therapy and when it was in the hands of occupational therapists it was participant and client led in line with the recovery approach. It is recommended that in future studies occupational therapists make explicit their use of the underlying theories that support their interventions as these are important factors to enable understanding of how recovery happens. Studies to date indicate that horticultural therapy facilitates recovery through providing choice, self-determination, acquisition of new skills, coping strategies, responsibility, opportunities for socialization, and development of therapeutic relationships. As recovery-oriented research on horticultural therapy in mental health is scarce, occupational therapists have an opportunity to rectify that by continuing to use recovery-specific measures as well as their occupation-based theoretical approach.

Implications and recommendations of the findings for research

Robust evidence for horticultural therapy in mental health, including controlled trials, is considered both necessary and feasible to ensure funding, incorporation into policy, and availability to service users (Clatworthy et al., Citation2013). Using recovery-specific outcome measures and scales, such as the ones outlined by Ashford et al. (Citation2019) for example, the Recovery Self-Assessment (RSA) (O'Connell et al., Citation2005); Recovery Assessment Scale (RAS) (Corrigan et al., Citation1999); Stages of Recovery Instrument (STORI) (Andresen et al., Citation2003); Recovery Process Inventory (RPI) (Jerrell et al., Citation2006); Mental Health Recovery Star (MHRS) (Mackeith and Burns, Citation2008); Self-Identified Stages of Recovery Inventory (SISRI) (Andresen et al., Citation2003); Questionnaire of Processes in Recovery (QPR) (Neil et al., Citation2009) to name a few, would support the emerging evidence base for horticultural therapy as a recovery-oriented intervention. A systematic review on the role of horticultural therapy in facilitating recovery may be feasible once more recovery-oriented research becomes available. Future research is needed on long-term effects of horticultural therapy.

Implications of the findings for practice

The findings of this review emphasize the importance of maintaining recovery orientation when providing services to individuals with mental health conditions, if such services are to comply with the current national and international guidelines (Slade et al., Citation2014). The ongoing utilization of horticulture as a therapeutic medium by occupational therapists is supported by the findings of this review. However, skillful facilitation with an occupation and theory driven focus is imperative to ensure recovery orientation of horticulture as a medium within the scope of occupational therapy.

Acknowledgements

Authors acknowledge the assistance of the subject librarian, Mr. David Mockler.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Horticultural Therapy Association. (2022). Definitions and positions. https://www.ahta.org/ahta-definitions-and-positions#:∼:text=Definition%20of%20a%20Horticultural%20Therapist,%2C%20rehabilitation%2C%20or%20vocational%20plan (19 July 2022)

- American Occupational Therapy Association. (2014). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68(Suppl. 1), S1–S48. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2014.682006

- Andresen, R., Oades, L., & Caputi, P. (2003). The experience of recovery from schizophrenia: Toward an empirically validated stage model. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 37(5), 586–594. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01234.x

- Arblaster, K., Mackenzie, L., Gill, K., Willis, K., & Matthews, L. (2019). Capabilities for recovery-oriented practice in mental health occupational therapy: A thematic analysis of lived experience perspectives. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 82(11), 675–684. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022619866129

- Argentzell, E., Håkansson, C., & Eklund, M. (2012). Experience of meaning in everyday occupations among unemployed people with severe mental illness. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 19(1), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2010.540038 21171830

- Aromataris, E., & Munn, Z. (Eds.) (2020). JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Joanna Briggs Institute.

- Ascencio, J. (2019). Horticultural therapy as an intervention for schizophrenia: A review. Alternative and Complementary Therapies, 25(4), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1089/act.2019.29231.jas

- Ashford, R. D., Brown, A., Brown, T., Callis, J., Cleveland, H. H., Eisenhart, E., Groover, H., Hayes, N., Johnston, T., Kimball, T., Manteuffel, B., McDaniel, J., Montgomery, L., Phillips, S., Polacek, M., Statman, M., & Whitney, J. (2019). Defining and operationalizing the phenomena of recovery: A working definition from the recovery science research collaborative. Addiction Research & Theory, 27(3), 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2018.1515352

- Carroll, C., Booth, A., & Cooper, K. (2011). A worked example of “best fit” framework synthesis: A systematic review of views concerning the taking of some potential chemopreventive agents. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-29

- Cipriani, J., Benz, A., Holmgren, A., Kinter, D., McGarry, J., & Rufino, G. (2017). A systematic review of the effects of horticultural therapy on persons with mental health conditions. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 33(1), 47–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2016.1231602

- Cipriani, J., Georgia, J., McChesney, M., Swanson, J., Zigon, J., & Stabler, M. (2018). Uncovering the value and meaning of a horticulture therapy program for clients at a long-term adult inpatient psychiatric facility. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 34(3), 242–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2017.1416323

- Clatworthy, J., Hinds, J., & Camic, P. M. (2013). Gardening as a mental health intervention: A review. Mental Health Review Journal, 18(4), 214–225. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHRJ-02-2013-0007

- Corrigan, P. W., Giffort, D., Rashid, F., Leary, M., & Okeke, I. (1999). Recovery as a psychological construct. Community Mental Health Journal, 35(3), 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018741302682

- Doroud, N., Fossey, E., & Fortune, T. (2015). Recovery as an occupational journey: A scoping review exploring the links between occupational engagement and recovery for people with enduring mental health issues. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 62(6), 378–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12238

- Ellison, M. L., Belanger, L. K., Niles, B. L., Evans, L. C., & Bauer, M. S. (2018). Explication and definition of mental health recovery: A systematic review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 45(1), 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0767-9

- Fisher, A. G. (2014). Occupation-centred, occupation-based, occupation-focused: Same, same or different? Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 21(Supp1), 96–107. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2014.952912

- Government of Ireland. (2020). Sharing the vision: A mental health policy for everyone. Department of Health. https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/2e46f-sharing-the-vision-a-mental-health-policy-for-everyone/ (19 July 2022)

- Han, A. R., Park, S. A., & Ahn, B. E. (2018). Reduced stress and improved physical functional ability in elderly with mental health problems following a horticultural therapy program. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 38, 19–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2018.03.011

- Hancock, N., Honey, A., & Bundy, A. C. (2015). Sources of meaning derived from occupational engagement for people recovering from mental illness. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 78(8), 508–515. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022614562789

- He, H., Li, T., Zhou, F., Yang, Q., Hu, L., & Yu, Y. (2021). The therapeutic effect of edible horticultural therapy on extrapyramidal symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. HortScience, 56(9), 1125–1129. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI15916-21

- Health Service Executive. (2018). Co-production in practice guidance document 2018–2020: Supporting the implementation of ‘A national framework for recovery in mental health 2018–2020’. Advancing Recovery in Ireland. Retrieved from https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/4/mental-health-services/advancingrecoveryireland/national-framework-for-recovery-in-mental-health/co-production-in-practice-guidance-document-2018-to-2020.pdf (26 April 2023).

- Jerrell, J. M., Cousins, V. C., & Roberts, K. M. (2006). Psychometrics of the recovery process inventory. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 33(4), 464–473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-006-9031-5

- Joyce, J., & Warren, A. (2016). A case study exploring the influence of a gardening therapy group on well-being. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 32(2), 203–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2015.1111184

- Kam, M. C., & Siu, A. M. (2010). Evaluation of a horticultural activity programme for persons with psychiatric illness. Hong Kong Journal of Occupational Therapy, 20(2), 80–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1569-1861(11)70007-9

- Kenmochi, T., Kenmochi, A., & Hoshiyama, M. (2019). Effects of horticultural therapy on symptoms and future perspective of patients with schizophrenia in the chronic stage. Journal of Therapeutic Horticulture, 29(1), 1–10.

- Leamy, M., Bird, V., Le Boutillier, C., Williams, J., & Slade, M. (2011). Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(6), 445–452. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083733

- MacKeith, J., & Burns, S. (2008). Mental health recovery star. Mental Health Providers Forum and Triangle Consulting.

- Meehan, T. J., King, R. J., Beavis, P. H., & Robinson, J. D. (2008). Recovery-based practice: Do we know what we mean or mean what we know?. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 42(3), 177–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048670701827234

- Mental Health Commission. (2007). Quality framework: Mental health services in Ireland. https://www.mhcirl.ie/sites/default/files/2021-01/The%20Quality%20Framework.pdf (19 July 2022).

- Monroe, L. (2015). Horticulture therapy improves the body, mind and spirit. Journal of Therapeutic Horticulture, 25(2), 33–40. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24865266.

- Najjar, A., Foroozandeh, E., & Asadi Gharneh, H. A. (2018). Horticulture therapy effects on memory and psychological symptoms of depressed male outpatients. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal, 16(2), 147–154. https://doi.org/10.32598/irj.16.2.147

- Neil, S. T., Kilbride, M., Pitt, L., Nothard, S., Welford, M., Sellwood, W., & Morrison, A. P. (2009). The Questionnaire about the Process of Recovery (QPR): A measurement tool developed in collaboration with service users. Psychosis, 1(2), 145–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/17522430902913450

- Nugent, A., Hancock, N., & Honey, A. (2017). Developing and sustaining recovery-orientation in mental health practice: Experiences of occupational therapists. Occupational Therapy International, 2017, 5190901–5190909. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/5190901

- O'Connell, M., Tondora, J., Croog, G., Evans, A., & Davidson, L. (2005). From rhetoric to routine: Assessing perceptions of recovery-oriented practices in a state mental health and addiction system. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 28(4), 378–386. https://doi.org/10.2975/28.2005.378.386

- Oh, Y. A., Park, S. A., & Ahn, B. E. (2018). Assessment of the psychopathological effects of a horticultural therapy program in patients with schizophrenia. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 36, 54–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2017.11.019

- Parkinson, S., Lowe, C., & Vecsey, T. (2011). The therapeutic benefits of horticulture in a mental health service. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(11), 525–534. https://doi.org/10.4276/030802211X13204135680901

- Perrins-Margalis, N. M., Rugletic, J., Schepis, N. M., Stepanski, H. R., & Walsh, M. A. (2000). The immediate effects of a group-based horticulture experience on the quality of life of persons with chronic mental illness. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 16(1), 15–32. https://doi.org/10.1300/J004v16n01_02

- Pieters, H. C., Ayala, L., Schneider, A., Wicks, N., Levine-Dickman, A., & Clinton, S. (2019). Gardening on a psychiatric inpatient unit: Cultivating recovery. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 33(1), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2018.10.001

- Rebeiro Gruhl, K. L. (2005). Reflections on…. The recovery paradigm: Should occupational therapists be interested? Revue Canadienne D'ergotherapie [Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy], 72(2), 96–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841740507200204

- Sempik, J., Aldridge, J., & Becker, S. (2003). Social and therapeutic horticulture: Evidence and messages from research. Thrive.

- Sinnott, R., & Rowlís, M. (2021). A gardening and woodwork group in mental health: A step towards recovery. Irish Journal of Occupational Therapy, 49(2), 96–103. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOT-08-2021-0018

- Siu, A. M., Kam, M., & Mok, I. (2020). Horticultural therapy program for people with mental illness: A mixed-method evaluation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 711. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030711

- Slade, M., Amering, M., Farkas, M., Hamilton, B., O'Hagan, M., Panther, G., Perkins, R., Shepherd, G., Tse, S., & Whitley, R. (2014). Uses and abuses of recovery: Implementing recovery‐oriented practices in mental health systems. World Psychiatry, 13(1), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20084

- Smidl, S., Mitchell, D. M., & Creighton, C. L. (2017). Outcomes of a therapeutic gardening program in a mental health recovery center. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 33(4), 374–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2017.1314207

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2012). SAMHSA’s working definition of recovery. US Department of Health and Human Services. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/pep12-recdef.pdf (19 July 2022)

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- Tu, H. M. (2022). Effect of horticultural therapy on mental health: A meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 29(4), 603–615. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12818

- Wagenfeld, A., & Atchison, B. (2014). “Putting the occupation back in occupational therapy:” A survey of occupational therapy practitioners’ use of gardening as an intervention. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2(4), 4. https://doi.org/10.15453/2168-6408.1128

- Wilcock, A. (1998). Reflections on doing, being and becoming. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 65(5), 248–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841749806500501

- World Health Organisation. (2021). Comprehensive mental health action plan 2013–2030. WHO.

- York, M., & Wiseman, T. (2012). Gardening as an occupation: A critical review. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 75(2), 76–84. https://doi.org/10.4276/030802212X13286281651072

- Zhu, S., Wan, H., Lu, Z., Wu, H., Zhang, Q., Qian, X., & Ye, C. (2016). Treatment effect of antipsychotics in combination with horticultural therapy on patients with schizophrenia: A randomized, case-controlled study. Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry, 28(4), 195. https://doi.org/10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.216034