Abstract

Background: This systematic scoping review explored key features, application and potential benefits of sensory rooms and implications for sub-acute mental health services. Methods: Using electronic databases and citation tracking, fourteen studies were identified, data-extracted and thematically synthesized based on the research questions. Results: Sensory rooms include wide range of equipment and strategies. They offer a supportive space that help in distress management, that can lead to longer-term benefits. Training and implementation considerations are also discussed. Discussion: Sensory rooms, as a complementary approach, provide tools and strategies to assist in managing distress. Staff and consumer training and tailored use of sensory strategies are essential.

Introduction

Sensory processing is how individuals interact with and interpret information from the environment and their own bodies. Sensory modalities include seven senses: vision, hearing, touch, taste, smell, vestibular and proprioception (Brown et al., Citation2019; Harrison et al., Citation2019). Difficulties in sensory processing can be common among people with mental illness (Greven et al., Citation2019; Harrison et al., Citation2019), and may result in over- or under-responsiveness to environmental stimuli, seeking or avoiding sensory information (Brown et al., Citation2019; Harrison et al., Citation2019), that interfere with daily functioning and participation in everyday life (Bailliard & Whigham, Citation2017; Harrison et al., Citation2019). Some sensory modalities or certain circumstances may be perceived as being unpleasant, triggering or overwhelming that can heavily impact social and occupational functioning, indicating a need for targeted sensory-based strategies (Andersson et al., Citation2021; Bailliard & Whigham, Citation2017; Brown et al., Citation2019).

Sensory-based interventions have demonstrated promising therapeutic benefits (Alhaj & Trist, Citation2023; Haig & Hallett, Citation2023; Kandlur et al., Citation2023). Designated sensory modalities, activities or environments can support individuals regulate their emotions and self-manage at the time of distress (Brown et al., Citation2019; Hitch et al., Citation2021; Kandlur et al., Citation2023). Sensory rooms have gained popularity recently, for their application in inpatient settings to enable individuals to self-regulate and to reduce the need for restrictive approaches (Dorn et al., Citation2019; Haig & Hallett, Citation2023). Established initially by Champagne and Stromberg (Citation2004), sensory rooms provide a safe environment to support individuals to regain control over their emotions through engagement in activities that offer desired/appropriate sensory modalities for their needs (Brown et al., Citation2019; Fraser et al., Citation2017; Scanlan & Novak, Citation2015). There is growing strong evidence on the benefits and application of sensory rooms in inpatient mental health settings as a complementary approach to enable self-regulation, reduce distress, foster recovery and improve participation in daily activities (Craswell et al., Citation2021; Haig & Hallett, Citation2023; Kandlur et al., Citation2023; Ma et al., Citation2021). There are, however, variations in the design and application of, and involvement of staff in sensory rooms (Craswell et al., Citation2021; Haig & Hallett, Citation2023; Kandlur et al., Citation2023).

Sensory rooms can particularly be helpful in enabling self-management in sub-acute settings. This study was set up as a collaboration between a university and a healthcare provider to identify key features, application and potential benefits of sensory rooms for an inpatient sub-acute mental health setting. Subacute residential services, known as Prevention and Recovery Care (PARC), have been operating in Australia since 2003. Integrating clinical and psychosocial care, the PARC services aim to promote recovery, autonomy and collaboration. They offer short-term residential and psychosocial supports up to four weeks as a substitute for hospitalization or for those leaving hospital early (Farhall et al., Citation2021; Fletcher et al., Citation2019; Ngo et al., Citation2020). This ‘step-up, step-down’ approach has demonstrated positive outcomes and consumers’ satisfaction; in particular reduced need for hospitalization, involuntary treatment or restrictive interventions (Farhall et al., Citation2021; Ngo et al., Citation2020). PARC services involve small-scale home-like residential units that aim to enable autonomy and self-management through offering a range of interventions such as therapeutic groups, life-skill training, social and community-based activities (Fletcher et al., Citation2019). The PARC services value collaborative approaches and consumers’ participation by providing natural, supportive and minimally restrictive environments where consumers can learn about and self-manage symptoms (Fletcher et al., Citation2019; Green et al., Citation2019). Despite emerging evidence supporting the role of PARC in promoting recovery, better understanding of application of psychosocial and clinical approaches to PARC practices and policies is required (Fletcher et al., Citation2019; Green et al., Citation2019; Ngo et al., Citation2020). This review contributes to this understanding by summarizing findings from previous studies on key features, application and benefits of sensory rooms. The implications of sensory rooms for PARC setting are discussed.

Methods

A systematic scoping review framework (Arksey & O'Malley, Citation2005; Daudt et al., Citation2013) informed this review using the six phases: 1) identifying research questions; 2) locating and searching for relevant evidence; 3) screening and selecting relevant studies; 4) data extraction; 5) collating and summarizing; and 6) consultation.

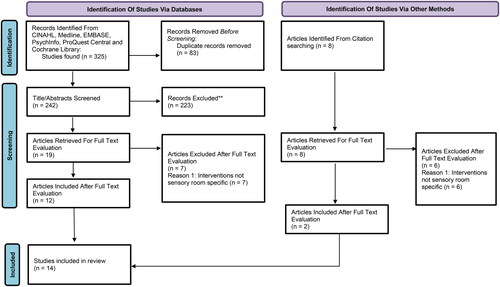

The need for the better understanding of the key features, application and potential benefits of sensory rooms was initiated by an occupational therapist (DMc) working at a PARC service with experience in designing and implementing sensory rooms. The occupational therapist liaised with the first author to establish the need for this review. This included a preliminary literature search and development of a scoping review protocol. Four electronic databases (CINAHL, MEDLINE, PubMed and EMBASE) were searched to locate relevant studies. Example of search terms included ‘mental health’, ‘mental illness*’, ‘mental disorder*’ or ‘psychiatric illness*’; and ‘sensory room*’, ‘sensory approach*’, ‘sensory intervention*’. Search terms related to sub-acute setting were not included as no studies could be located by adding these terms. Additionally, to identify all outcomes related to sensory rooms, search terms related to outcomes were not included. Limits applied included peer-reviewed studies published in English, between 2011 and 2021, and full-text availability. Citation tracking was also used to locate other relevant studies that were not retrieved through database searching (). The search was completed in November 2021.

The studies were screened through reading the title and abstract to remove irrelevant titles, followed by review of the full text. Studies were included if they were conducted in mental health settings, explored perspectives of people with mental illness and/or staff, and included the use of sensory rooms as a purposefully designed space (i.e. separate space to clinical rooms) that used sensory strategies and equipment. All types of research designs, including review studies were included. Non-research publications such as commentaries, opinion papers or editorials were excluded. Fourteen studies met the inclusion criteria for this review. Four authors (ND, MC, KG and MS) contributed to screening and selection of the studies. Data were extracted from the included studies related to fields proposed for scoping reviews and additional fields to enrich understanding of the studies (e.g. authors, aim, location/setting, methodology and design, participants, and key findings) (). Three authors conducted the data extraction (MC, KG and MS), with another author reviewing the data extraction table (ND) for consistency and accuracy.

Table 1. Data extraction.

The authors began by color-coding key findings form the studies relevant the research questions. They then compiled and synthesized data based on similarities and differences between the findings. Similar patterns generated tentative categories and a preliminary summary report of the key outcomes, characteristics and application of sensory rooms was developed and reviewed by all authors. As suggested by Levac et al. (Citation2010), consultation should be an essential component of the scoping reviews, therefore the preliminary summary report was reviewed by an occupational therapist working in a mental health facility and with experience in using sensory rooms. The key findings were presented to the occupational therapy team at Youth PARC service at Bendigo Health and an industrial designer with experiences regarding designing sensory rooms. Following the presentation and feedback from the consultation, the key categories relevant to sensory rooms’ application and outcomes were finalized.

Findings

Characteristics of studies

Total of 242 articles were retrieved through database searches after removing the duplicates. After reading title and abstracts, 19 studies were found potentially relevant for full-text review. Full text of these articles were retrieved and reviewed in depth that resulted in excluding 7 articles that were not specifically studied sensory rooms. Two additional articles were found through citation tracking, resulted in including total of 14 articles for this review (). summarizes the characteristics and key findings of the 14 studies. Five of the studies were conducted in Australia, 3 in the United Kingdom, 2 in Sweden, 2 in New Zealand, one in United States, and one in Canada. Half of the studies used qualitative designs, six were quantitative studies and one used a mixed-methods approach. Twelve of the studies involved consumers with varying diagnoses who had participated in sensory room interventions. Seven studies included healthcare staff working within mental health settings and five studies involved both consumers and healthcare staff. Across the 14 studies, there was a total of 263 participants, comprising of 80 males and 183 females with participant ages ranging from 12 to 73 years old.

Application of sensory rooms in mental health settings

Design, equipment and tools

The review found that sensory rooms use a wide variety of sensory modalities purposefully designed to address consumers’ sensory needs. These sensory modalities can be grouped in six key areas including touch, smell, taste, vision, hearing and proprioception. summarizes the application of sensory equipment across studies. All studies except for West et al. (Citation2017) reported using tactile equipment featuring bean bag chairs, massage chairs, fidget items, stress balls and weighted items such as blankets, animals, and cushions. Weighted blankets were the most frequently used sensory tool (Hedlund Lindberg et al., Citation2019; Novak et al., Citation2012). Scented objects such as aromatic oils, demisters and diffusers, scented hand creams, aromatherapy blankets and scented playdough were used within the sensory rooms to stimulate the olfactory sense (e.g. Barbic et al., Citation2019; Björkdahl et al., Citation2016; Davies et al., Citation2020; Hedlund Lindberg et al., Citation2019); ). Sensory tools relating to taste were less commonly used with only four studies reported the use of lollies, mints, chewing gum, and ice blocks (Bobier et al., Citation2015; Dorn et al., Citation2019; Lloyd et al., Citation2015; Wiglesworth & Farnworth, Citation2016).

Table 2. Summary of the findings related to key features, application and benefit of sensory rooms.

All studies except one (West et al, Citation2017) reported the use of visual and auditory features (see ). Examples of visual features included projector images and lighting, adjustable lights, featured lamps, fiber optic lighting and photo walls. Auditory stimuli used in the sensory rooms included music played through radios, mobile phones, speakers, and sound systems (). All studies except Björkdahl et al. (Citation2016) and West et al. (Citation2017), reported using at least one auditory feature. Listening to music was a popular choice for consumers as outlined by Novak et al. (Citation2012), Wiglesworth and Farnworth (Citation2016) and Seckman et al. (Citation2017). The ability to choose preferred music was identified an important factor (Smith & Jones, Citation2014). Noise canceling headphones were also used in one study (Forsyth & Trevarrow, Citation2018).

Proprioceptive sensory equipment was only briefly described in the studies with tools such as recliner or rocking chairs, exercise balls or mini trampolines reportedly used (). Several studies however, such as Davies et al. (Citation2020), Smith and Jones (Citation2014), West et al. (Citation2017), and Wiglesworth and Farnsworth (Citation2016) indicated that these features were not present. The proprioceptive equipment was reportedly helpful to reduce tension and to manage distress (Hedlund Lindberg et al., Citation2019; Sutton et al., Citation2013).

Implementation, staff preparation and training

Implementation of sensory rooms in relation to gender and age showed differing results. Some studies reported that females were more likely to use sensory rooms than males, perhaps due to higher prevalence of anxiety disorders in females (Bobier et al., Citation2015; Novak et al., Citation2012; West et al., Citation2017) and/or the design of the sensory rooms (Novak et al., Citation2012).

Studies reported that sensory rooms can be used with or without presence of staff members. Some studies suggested at least one staff per consumer in the sensory room where high level of distress or potential risk is identified (Dorn et al., Citation2019; Seckman et al., Citation2017; Wiglesworth & Farnworth, Citation2016). Some studies, however, suggested a group supervision approach (Dorn et al., Citation2019) (Davies et al., Citation2020; Smith & Jones, Citation2014). Other factors to consider regarding presence of staff included the facility resources, purpose of using sensory room, staffing, and consumers’ choice (Forsyth & Trevarrow, Citation2018; Hedlund Lindberg et al., Citation2019). Hedlund Lindberg et al. (Citation2019), for example, reported that consumers felt more comfortable when given choice regarding the presence of staff members. This is an important consideration as presence of staff can impact consumers’ sense of autonomy and may alter the purpose of the room.

The most frequent time of day consumers used the sensory rooms were evenings (Hedlund Lindberg et al., Citation2019; Seckman et al., Citation2017) and after lunch (Bobier et al., Citation2015). This is probably due to the reduced number of staffing or group programs available in the evening (Seckman et al., Citation2017) and the use of sensory rooms as a self-care strategy prior to going to sleep (Hedlund Lindberg et al., Citation2019). Four of the studies reported that consumers spent 35 minutes on average in the sensory rooms, with 2 hours maximum (Bobier et al., Citation2015; Novak et al., Citation2012; Seckman et al., Citation2017; Wiglesworth & Farnworth, Citation2016).

Studies reported that the consumers may initiate using sensory rooms with or without referral from the staff member. Wiglesworth and Farnworth (Citation2016) suggested that staff members were more likely to refer consumers to sensory room when they demonstrate physical or emotional signs of distress. In such circumstances and when more than one consumer wanted to use the sensory room, it is suggested that staff use their clinical judgment to decide how sensory room would benefit the consumer (Seckman et al., Citation2017).

Most studies identified the need for training programs alongside the implementation of the sensory rooms (). The training programs were often delivered by occupational therapists and nursing staff, ranging from singular short sessions to a half-day workshop (Björkdahl et al., Citation2016; Bobier et al., Citation2015; Davies et al., Citation2020; Forsyth & Trevarrow, Citation2018; West et al., Citation2017). Most training programs included background information into sensory modulation, application of sensory tools and safety procedures (e.g. Björkdahl et al., Citation2016; Bobier et al., Citation2015; Seckman et al., Citation2017)). In addition, some studies included an orientation (such as regular education or plain language information handout) to the consumers regarding the use and accessibility of sensory rooms (Björkdahl et al., Citation2016; Dorn et al., Citation2019; Forsyth & Trevarrow, Citation2018; Sutton et al., Citation2013). Barbic et al. (Citation2019) indicated that these orientation sessions should be further structured around the purpose of sensory rooms within each setting and individual needs.

Integrating sensory rooms within mental health practice

Some studies indicated that sensory rooms can be used as an adjunct intervention or an alternative method compared with medication, seclusion or chemical restraints, particularly for individuals with history of aggression and a complex care plan (Barbic et al., Citation2019; Björkdahl et al., Citation2016; Davies et al., Citation2020; Dorn et al., Citation2019; Forsyth & Trevarrow, Citation2018; West et al., Citation2017). Studies also suggested that sensory rooms can be associated with reduced need for medication, restrictive and coercive interventions, thus can be a safe alternative (Barbic et al., Citation2019; Björkdahl et al., Citation2016; Davies et al., Citation2020; Dorn et al., Citation2019; Forsyth & Trevarrow, Citation2018; Hedlund Lindberg et al., Citation2019). However, inconsistencies were reported in the studies regarding reduction of seclusion and restrictive measures.

Potential benefits of sensory rooms

The review of literature suggested that sensory room can have potential benefits by providing a safe and supportive space that can assist in addressing distress and self-management of symptoms in both the short- and long-term. provides a summary of the outcomes.

Safe, supportive space and distress management

In both quantitative and qualitative studies, sensory rooms showed benefits in soothing, calming and regulating mood or energy levels for consumers (e.g. Bobier et al., Citation2015; Hedlund Lindberg et al., Citation2019; Wiglesworth & Farnworth, Citation2016) (). Sensory rooms and equipment had positive impacts on consumers’ emotional state and was identified a “peaceful atmosphere to boost mood” (Barbic et al., Citation2019, p. 6). Consumers experiencing anxiety or distress found the sensory rooms relaxing which also helped their sleep quality (Björkdahl et al., Citation2016; Hedlund Lindberg et al., Citation2019; Smith & Jones, Citation2014; Sutton et al., Citation2013). Some consumers described the sensory room as a safe space to help them ‘escape’ from clinical environments and to unwind (Björkdahl et al., Citation2016; Hedlund Lindberg et al., Citation2019; Seckman et al., Citation2017; Sutton et al., Citation2013). The sensory rooms provided consumer a sense of freedom and choice that encouraged trust, empowered consumers, and facilitated decision making (Björkdahl et al., Citation2016; Hedlund Lindberg et al., Citation2019; Smith & Jones, Citation2014). Consumers appreciated the opportunity to access sensory room when they wished, and use the equipment based on their preferences (e.g. choose their own music) (Barbic et al., Citation2019; Björkdahl et al., Citation2016; Hedlund Lindberg et al., Citation2019). The need for presence of staff, therefore, should be considered in the light of these benefits.

As shown in , sensory rooms played a role in addressing distress, and regulating emotions and arousal (e.g.Barbic et al., Citation2019; Björkdahl et al., Citation2016; Dorn et al., Citation2019; Hedlund Lindberg et al., Citation2019; Lloyd et al., Citation2015). Sensory rooms can have potential benefits as an early intervention strategy to address distress or aggression in a safe and minimally restrictive environment (Dorn et al., Citation2019; Novak et al., Citation2012; Sutton et al., Citation2013; Wiglesworth & Farnworth, Citation2016). Sensory rooms provided consumers with the opportunity to explore their sensory preferences, regulate their emotions and self-manage their feelings (Barbic et al., Citation2019; Björkdahl et al., Citation2016; Forsyth & Trevarrow, Citation2018). For instance, West et al. (Citation2017) reported that 94% of consumers had a perceived reduction in distress following sensory room use and 89% showed fewer signs of distress as measured by staff. Novak et al. (Citation2012), similarly, reported reduced stress, distress and agitation among consumers who used sensory rooms. This finding was not associated with age, gender, history of trauma, presence of personality or anxiety disorders, and time spent in sensory rooms. Other studies (Barbic et al., Citation2019; Dorn et al., Citation2019; Sutton et al., Citation2013; West et al., Citation2017) have also reported the role of sensory rooms in managing distress.

Self-management and control

Many of the reviewed studies reported that sensory rooms can be a safe space that encourages recovery, self-management, and sense of control (Barbic et al., Citation2019; Forsyth & Trevarrow, Citation2018; Novak et al., Citation2012; Sutton et al., Citation2013) (). Sensory rooms offer noninvasive, home-like and supportive equipment for consumers to self-manage their distress or symptoms (Novak et al., Citation2012). They are identified by consumer as spaces where they can explore and identify their needs, choose the use of sensory strategies and gain better control over their emotional symptoms (Barbic et al., Citation2019; Forsyth & Trevarrow, Citation2018; Sutton et al., Citation2013). For example, a consumer stated:

“I found it really good sort of to be in control of the environment. Like, the sound … the lighting, it was just being in control of things around you, kind of helps to calm you down” (Sutton et al., Citation2013, p. 505).

Long term benefits and perceptions of staff

The long-term effects that sensory rooms may provide for consumers in the community is promising (e.g. Bobier et al., Citation2015; Sutton et al., Citation2013), as outlined in . Forsyth and Trevarrow (Citation2018) reported the benefits of implementing low technological and low budget sensory items in the room, that provided service users with an opportunity to transfer the skills learnt in the mental health facility to implement in the community setting and/or home environment. Participants in one study (Sutton et al., Citation2013) spoke about the sensory-based strategies or tools that helped them manage their stress in their home or community environments. This highlights the importance of sensory modulation as a self-initiated strategy with longer term implications for self-management of symptoms and to encourage recovery.

Sensory rooms were viewed positively by staff members as well, particularly in relation to its unique design as a supportive therapeutic space (Björkdahl et al., Citation2016; Smith & Jones, Citation2014; Sutton et al., Citation2013). Sensory rooms provided one-on-one opportunities to assist building rapport and enhancing consumers’ engagement (Smith & Jones, Citation2014; Sutton et al., Citation2013; Wiglesworth & Farnworth, Citation2016). In addition to supporting consumers, some staff also identified their own use of sensory rooms to relax, unwind and ‘escape’ from the busy inpatient environment when they have a chance (Björkdahl et al., Citation2016; Forsyth & Trevarrow, Citation2018).

Discussion

The findings from this systematic review can inform the application of sensory room in mental health occupational therapy. The review of studies revealed that sensory rooms, as purposefully designed spaces, include variety of tools and approaches that can be tailored to consumers’ needs. Sensory rooms offer a complementary approach in addressing distress through providing a safe and non-clinical environment and equipping consumers with self-directed strategies to manage their symptoms (Björkdahl et al., Citation2016; Davies et al., Citation2020; Novak et al., Citation2012).

Sensory rooms encompass wide range of tools and sensory strategies. The most commonly used sensory tools included tactile materials, visual tools and auditory equipment. Studies reported therapeutic application of weighted items, lighting and music. In particular, these tools provide safe and noninvasive sensory strategies that offer choice (e.g. consumer can choose their own music to play) and can be used concurrently as multi-modal tools (e.g. using the weighted blanket while listening to music). Consistent with Cusic et al. (Citation2022) who identified the effectiveness of multisensory environment on mood, behavior and occupational functioning of people with dementia, it is suggested that multi-modal sensory strategies can be used prior to or as part of interactions with the clients within the mental health settings. For example, PARC settings may run therapeutic groups or individual activities within the sensory room to facilitate communication and to encourage participation. It is, however, important to consider consumers’ preferences and organizational context such as costs, availability of space, and staffing, in designing and implementing sensory rooms (Björkdahl et al., Citation2016; Chalmers et al., Citation2012; West et al., Citation2017). Several studies (Björkdahl et al., Citation2016; Davies et al., Citation2020; Hedlund Lindberg et al., Citation2019; West et al., Citation2017) described the role of sensory rooms when integrated into the consumers’ overall care plan, and tailored to their unique needs and preferences. Andersson et al. (Citation2021) also highlighted the importance of individuals’ sensory needs, their strengths and preferences to develop strategies to help addressing sensory needs within the context of everyday life. Bailliard and Whigham (Citation2017), similarly, suggested that sensory modalities can be adapted within the physical environment. These findings are particularly important as the PARC services aim to facilitate transition from clinical settings to community and independent living (Fletcher et al., Citation2019). PARC services may consider embedding sensory room within the therapeutic programs to encourage consumers adopt sensory strategies in everyday life to address distress and self-manage symptoms. In particular, sensory rooms offer a range of tools that can be adapted to all ages and genders (Bobier et al., Citation2015). PARC services are also encouraged to include sensory assessments to determine consumers’ needs and sensory preferences to encourage their participation in design and use of sensory rooms (Hitch et al., Citation2021; Wiglesworth & Farnworth, Citation2016).

Majority of studies identified the need for training for both staff and consumers to ensure safety and desired therapeutic benefits (Björkdahl et al., Citation2016; Davies et al., Citation2020; West et al., Citation2017). Studies suggested that staff training should include theoretical foundations of using sensory modalities, safety and risk management, application of sensory equipment and information on benefits of sensory strategies. For consumers, a brief orientation or plain language handout on purpose and application of sensory room, has been identified beneficial (Barbic et al., Citation2019; Björkdahl et al., Citation2016; Dorn et al., Citation2019; Forsyth & Trevarrow, Citation2018; Novak et al., Citation2012; Sutton et al., Citation2013). PARC services may develop these handouts as part of the orientation provided to consumers upon admission.

Sensory rooms offer natural features that empower consumers to apply sensory strategies within and beyond mental health settings to self-manage their symptoms (Barbic et al., Citation2019; Hedlund Lindberg et al., Citation2019; Sutton et al., Citation2013). This can enable choice and autonomy that are key elements of recovery (Leamy et al., Citation2011) and pivotal to PARC services. Offering choice regarding the intervention plan facilitates consumers’ engagement and leads to better outcomes (Laugharne & Priebe, Citation2006; Piat et al., Citation2020). Sensory rooms offer choice within a safe environment and use ordinary objects that can create a supportive environment to help consumers re-connect with everyday life and develop self-management strategies using sensory modalities. PARC services may consider making sensory rooms available 24-hours a day and on weekends to better facilitate choice and autonomy. However, services are encouraged to comply with the safety guidelines and risk management procedures to ensure safe use of the sensory rooms and to take measures to allow unattended use of the room (Hedlund Lindberg et al., Citation2019; Seckman et al., Citation2017).

Sensory rooms can provide a safe ‘escape’ within the mental health settings through offering real-life modalities (Björkdahl et al., Citation2016; Hedlund Lindberg et al., Citation2019; Novak et al., Citation2012). Most inpatient settings are associated with a sense of powerlessness, alienation, passivity and boredom (McCormick et al., Citation2005; Rose et al., Citation2015). As a ‘bridge’ between clinical and non-clinical settings, PARC services can integrate home-like features of sensory rooms within their settings to help consumers unwind and re-connect with everyday life (Björkdahl et al., Citation2016; Novak et al., Citation2012). PARC services may promote use of sensory rooms through structuring therapeutic activities (e.g. mindfulness groups) or consumers’ independent use of the room when there are no other planned activities (e.g. during evening or as a relaxation strategy) (Hedlund Lindberg et al., Citation2019; Seckman et al., Citation2017). Through the use of sensory rooms, PARC consumers can gain awareness about their sensory preferences, and apply sensory strategies as part of everyday routines while residing at and after leaving PARC services (Bobier et al., Citation2015; Forsyth & Trevarrow, Citation2018; Sutton et al., Citation2013). Listening to calming music, using fidget toys to manage stress, or weighted blankets are just a few low-cost examples that consumers may wish to use independently after leaving PARC services.

The findings from this review offer several implications for practice. First, it is important to consider the potential benefits of sensory modalities in design and application of the sensory rooms. The review of the studies showed that weighted items, visual features and music (particularly when chosen by consumers) are the most commonly used modalities, whilst modalities using olfactory and taste have not been widely implemented; partly because these two senses are highly individualized and diverse. Second, it is suggested that individuals’ sensory preferences and needs are prioritized in designing sensory rooms. Sensory assessments used by occupational therapists, such as sensory profile (Licciardi & Brown, Citation2023), can be useful tools in developing targeted and person-cantered intervention plans (Hitch et al., Citation2021; Wiglesworth & Farnworth, Citation2016). Third, well-designed and targeted training programs for staff and consumers should be an integrated aspect of sensory rooms, particularly to ensure safe and practical use of sensory strategies (Martin & Suane, Citation2012). Fourth, it is recommended that sensory rooms use home-like features, and a variety of gender-neutral and inclusive sensory equipment (Bobier et al., Citation2015). Occupational Therapists, for example, are recommended to contribute to design of the sensory rooms using their task analysis knowledge. Finally, it is important that sensory room provide 24-hour access to enable choice, autonomy and control (e.g. preferred time and duration of using sensory room). It is suggested that the sensory rooms enable consumers to gain awareness of their sensory needs and trial sensory modalities to identify the strategies suited best to their needs. A sensory game (e.g. picking favorite sensory items followed by a sensory training), for example, can encourage this.

However, whilst some studies suggested more freedom within the sensory room, some highlighted the need for at least one staff member to be present when consumers use sensory room. It is suggested that safe design of sensory rooms can reduce the need for staff supervision as the presence of staff can impact the potential benefits of sensory rooms particularly in relation to consumers’ choice and self-management skills.

This study has some limitations that may impact the applications of the findings. Consistent with the original scoping review framework (Arksey & O'Malley, Citation2005), a quality appraisal of the studies was not conducted, thus only limited insights into the rigor of the studies included in this review are provided. The findings from both quantitative and qualitative studies were combined. A meta-analysis of quantitative studies and a separate synthesis of qualitative findings may have provided an increased understanding of the effectiveness and experiences of using sensory rooms. This review did not limit database search to a specific age range or a setting. The application and therapeutic benefits of sensory rooms may differ between age groups and/or settings; thus, more targeted reviews of certain age groups or settings may be warranted. Acute settings, for instance, may require more structured approach compared to sub-acute (e.g. PARC) or community-based or residential settings. Overall, it is recommended that the findings from this review are applied with careful attention to the requirements and organizational protocols within each setting.

Conclusion

This review has explored the key features, application and potential benefits of sensory rooms within mental health care and implications for PARC services. Sensory rooms use variety of tools and strategies and can serve as a complementary approach in addressing distress and enabling self-management in mental health care. It is important to tailor sensory rooms to consumers’ needs and sensory preferences as an integrated approach in person-cantered and recovery-oriented intervention plan.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the coordinators of the project-based unit at La Trobe University university as well as Bendigo Heatlh, Youth PARC staff who proposed the initial topic and provided consultation throughout the scoping review.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alhaj, H., & Trist, A. (2023). The effects of sensory modulation on patient’s distress and use of restrictive interventions in adult inpatient psychiatric settings: A critical review. Advances in Biomedical and Health Sciences, 2(3), 105. https://doi.org/10.4103/abhs.abhs_52_22

- Andersson, H., Sutton, D., Bejerholm, U., & Argentzell, E. (2021). Experiences of sensory input in daily occupations for people with serious mental illness. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 28(6), 446–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2020.1778784

- Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Bailliard, A. L., & Whigham, S. C. (2017). Linking neuroscience, function, and intervention: A scoping review of sensory processing and mental illness. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy: Official Publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association, 71(5), 7105100040p1–7105100040p18. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2017.024497

- Barbic, S. P., Chan, N., Rangi, A., Bradley, J., Pattison, R., Brockmeyer, K., Leznoff, S., Smolski, Y., Toor, G., Bray, B., Leon, A., Jenkins, M., & Mathias, S. (2019). Health provider and service-user experiences of sensory modulation rooms in an acute inpatient psychiatry setting. PloS One, 14(11), e0225238. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225238

- Björkdahl, A., Perseius, K.-I., Samuelsson, M., & Lindberg, M. H. (2016). Sensory rooms in psychiatric inpatient care: Staff experiences. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 25(5), 472–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12205

- Bobier, C., Boon, T., Downward, M., Loomes, B., Mountford, H., & Swadi, H. (2015). Pilot investigation of the use and usefulness of a sensory modulation room in a child and adolescent psychiatric inpatient unit. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 31(4), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2015.1076367

- Brown, C., Steffen-Sanches, P., & Nicholson, R. (2019). Sensory processing. In C. Brown, V. Stoffel, & J. P. Muñoz (Eds.), Occupational therapy in mental health: A vision for participation (2nd ed., pp. 323–341). F.A. Davis Company.

- Chalmers, A., Harrison, S., Mollison, K., Molloy, N., & Gray, K. (2012). Establishing sensory-based approaches in mental health inpatient care: A multidisciplinary approach. Australasian Psychiatry: Bulletin of Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, 20(1), 35–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856211430146

- Champagne, T., & Stromberg, N. (2004). Sensory approaches in inpatient psychiatric settings: Innovative alternatives to seclusion & restraint. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 42(9), 34–44. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20040901-06

- Craswell, G., Dieleman, C., & Ghanouni, P. (2021). An integrative review of sensory approaches in adult inpatient mental health: Implications for occupational therapy in prison-based mental health services. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 37(2), 130–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2020.1853654

- Cusic, E., Hoppe, M., Sultenfuss, M., Jacobs, K., Holler, H., & Obembe, A. (2022). Multisensory environments for outcomes of occupational engagement in dementia: A systematic review. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics, 40(3), 275–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703181.2022.2028954

- Daudt, H. M., Van Mossel, C., & Scott, S. J. (2013). Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-48

- Davies, R., Murphy, K., & Sethi, F. (2020). Sensory room in a psychiatric intensive care unit. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 16(1), 23–28. https://doi.org/10.20299/jpi.2019.016

- Dorn, E., Hitch, D., & Stevenson, C. (2019). An evaluation of a sensory room within an adult mental health rehabilitation unit. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 36(2), 105–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2019.1666770

- Farhall, J., Brophy, L., Reece, J., Tibble, H., Le, L. K.-D., Mihalopoulos, C., Fletcher, J., Harvey, C., Morrisroe, E., Newton, R., Sutherland, G., Spittal, M. J., Meadows, G., Vine, R., & Pirkis, J. (2021). Outcomes of Victorian prevention and recovery care services: A matched pairs comparison. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 55(12), 1178–1190. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867420983473

- Fletcher, J., Brophy, L., Killaspy, H., Ennals, P., Hamilton, B., Collister, L., Hall, T., & Harvey, C. (2019). Prevention and recovery care services in Australia: Describing the role and function of sub-acute recovery-based residential mental health services in Victoria. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 735–735. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00735

- Forsyth, A. S., & Trevarrow, R. (2018). Sensory strategies in adult mental health: A qualitative exploration of staff perspectives following the introduction of a sensory room on a male adult acute ward. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(6), 1689–1697. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12466

- Fraser, K., MacKenzie, D., & Versnel, J. (2017). Complex trauma in children and youth: A scoping review of sensory-based interventions. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 33(3), 199–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2016.1265475

- Green, R., Mitchell, P. F., Lee, K., Svensson, E., Toh, J.-W., Barentsen, C., Copeland, M., Newton, J. R., Hawke, K. C., & Brophy, L. (2019). Key features of an innovative sub-acute residential service for young people experiencing mental ill health. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), 311–311. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2303-4

- Greven, C. U., Lionetti, F., Booth, C., Aron, E. N., Fox, E., Schendan, H. E., Pluess, M., Bruining, H., Acevedo, B., Bijttebier, P., & Homberg, J. (2019). Sensory processing sensitivity in the context of environmental sensitivity: A critical review and development of research agenda. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 98, 287–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.01.009

- Haig, S., & Hallett, N. (2023). Use of sensory rooms in adult psychiatric inpatient settings: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 32(1), 54–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.13065

- Harrison, L. A., Kats, A., Williams, M. E., & Aziz-Zadeh, L. (2019). The importance of sensory processing in mental health: A proposed addition to the research domain criteria (RDoC) and suggestions for RDoC 2.0. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 103–103. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00103

- Hedlund Lindberg, M., Samuelsson, M., Perseius, K.-I., & Björkdahl, A. (2019). The experiences of patients in using sensory rooms in psychiatric inpatient care. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28(4), 930–939. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12593

- Hitch, D., Wilson, C., & Hillman, A. (2021). Sensory modulation in mental health practice. Mental Health Practice, 24(3),10–16. https://doi.org/10.7748/mhp.2020.e1422

- Kandlur, N. R., Fernandes, A. C., Gerard, S. R., Rajiv, S., & Quadros, S. (2023). Sensory modulation interventions for adults with mental illness: A scoping review. Hong Kong Journal of Occupational Therapy: HKJOT, 36(2), 57–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/15691861231204896

- Laugharne, R., & Priebe, S. (2006). Trust, choice and power in mental health: A literature review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41(11), 843–852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-006-0123-6

- Leamy, M., Bird, V., Le Boutillier, C., Williams, J., & Slade, M. (2011). Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 199(6), 445–452. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083733

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O'Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Licciardi, L., & Brown, T. (2023). An overview & critical review of the sensory profile–second edition. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 30(6), 758–770.

- Lloyd, C., King, R., & Machingura, T. (2015). An investigation into the effectiveness of sensory modulation in reducing seclusion within an acute mental health unit. Advances in Mental Health, 12(2), 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/18374905.2014.11081887

- Ma, D., Su, J., Wang, H., Zhao, Y., Li, H., Li, Y., Zhang, X., Qi, Y., & Sun, J. (2021). Sensory‐based approaches in psychiatric care: A systematic mixed‐methods review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 77(10), 3991–4004. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14884

- Martin, B. A., & Suane, S. N. (2012). Effect of training on sensory room and cart usage. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 28(2), 118–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2012.679526

- McCormick, B. P., Funderburk, J. A., Lee, Y., & Hale-Fought, M. (2005). Activity characteristics and emotional experience: Predicting boredom and anxiety in the daily life of community mental health clients. Journal of Leisure Research, 37(2), 236–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2005.11950052

- Ngo, H., Ennals, P., Turut, S., Geelhoed, E., Celenza, A., & Wolstencroft, K. (2020). Step-up, step-down mental health care service: Evidence from Western Australia’s first - a mixed-method cohort study. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 214–214. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02609-w

- Novak, T., Scanlan, J., McCaul, D., MacDonald, N., & Clarke, T. (2012). Pilot study of a sensory room in an acute inpatient psychiatric unit. Australasian Psychiatry: Bulletin of Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, 20(5), 401–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856212459585

- Piat, M., Seida, K., & Padgett, D. (2020). Choice and personal recovery for people with serious mental illness living in supported housing. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 29(3), 306–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2019.1581338

- Rose, D., Evans, J., Laker, C., & Wykes, T. (2015). Life in acute mental health settings: Experiences and perceptions of service users and nurses. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 24(1), 90–96. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796013000693

- Scanlan, J. N., & Novak, T. (2015). Sensory approaches in mental health: A scoping review. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 62(5), 277–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12224

- Seckman, A., Paun, O., Heipp, B., Van Stee, M., Keels-Lowe, V., Beel, F., Spoon, C., Fogg, L., & Delaney, K. R. (2017). Evaluation of the use of a sensory room on an adolescent inpatient unit and its impact on restraint and seclusion prevention. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing: Official Publication of the Association of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nurses, Inc, 30(2), 90–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcap.12174

- Smith, S., & Jones, J. (2014). Use of a sensory room on an intensive care unit. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 52(5), 22–30. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20131126-06

- Sutton, D., Wilson, M., Van Kessel, K., & Vanderpyl, J. (2013). Optimizing arousal to manage aggression: A pilot study of sensory modulation. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 22(6), 500–511. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12010

- West, M., Melvin, G., McNamara, F., & Gordon, M. (2017). An evaluation of the use and efficacy of a sensory room within an adolescent psychiatric inpatient unit. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 64(3), 253–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12358

- Wiglesworth, S., & Farnworth, L. (2016). An exploration of the use of a sensory room in a forensic mental health setting: Staff and patient perspectives. Occupational Therapy International, 23(3), 255–264. https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.1428