Abstract

The immediate social microcosm surrounding diagnosed individuals are often neglected. Partners of persons with bipolar I disorder experience positive and challenging experiences of occupational engagement, informed by their partner role. Guided by Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), in-depth interviews unearthed participants’ lived experiences to highlight challenging experiences of occupational engagement, including, unmet occupational needs, occupational disharmony, and imbalance. Protective factors enhancing occupational engagement included satisfactorily achieving occupational needs and the experience of autotelic meaning. This study consolidated that exploring, understanding, and addressing occupational needs for everyone, including secondarily affected populations, should be a focus of occupational therapists.

Introduction

In aiming to understand the lived experience of occupational engagement of partners of persons with bipolar I disorder, contextualizing the parameters of the experience of occupational engagement is necessary. According to the World Health Organization, in 2019, 40 million individuals globally were directly impacted by bipolar disorder (WHO, Citation2020). The impact of mental health diagnoses (including bipolar I disorder) are extensive, often transcending the diagnosed client to affect those within their social contexts (Esan & Esan, Citation2015; Rowe & Morris, Citation2012; Spoelma et al., Citation2023). Considering that occupational engagement is elicited and guided by physical and social circumstances, the indirect influences of bipolar disorder on occupational engagement would thus extend to encompass many more individuals than those formally diagnosed (Morris & Cox, Citation2017). Social contextual factors (such as being a partner to an individual diagnosed with bipolar I disorder) may thus limit meaningful engagement or opportunities to engage in the areas of leisure, social engagement, work related occupations and self-care (McDougall et al., Citation2014).

Occupational therapy as a profession centralizes the construct of occupational engagement, placing emphasis on equitable occupational opportunities for all, and yet, it has been well documented that the occupational engagement of the direct client population (those who present themselves or those who are referred for therapeutic intervention) is a more prevalent area of focus in occupational therapy than the occupational engagement of the general population or secondarily affected populations (Hammell, Citation2017). Yet, Hammell (Citation2017, p.212) notes, “Occupational engagement is fundamentally important to the well-being of all people, not solely those whose health is already compromised.” Thus, understanding the lived experiences of occupational engagement of the partners of persons with bipolar disorder is necessary to begin contextualizing their challenging and positive experiences of occupational engagement.

Research outlines that the partners of persons with psychiatric diagnoses experience a substantial amount of psychosocial stress due to chronic exposure to stressors within their immediate social environment (Idstad et al., Citation2010; Joutsenniemi et al., Citation2011). Partners of persons with bipolar disorder are at risk of experiencing inadequate social support due to a decline in social activities and often receiving insufficient support from their diagnosed partner (Granek et al., Citation2016). Social strain is experienced as particularly high when the partner with bipolar disorder has increased support demands, specifically when acutely symptomatic (Boyers & Rowe, Citation2018). In addition to experiencing challenges in social engagement, the ability to practice effective self-care is compromised as a result of assuming caregiver like roles within their intimate relationship. Partners often place their own occupational needs on a level of secondary importance influencing their physical and emotional wellbeing, which in turn implicates resilience affecting readiness to handle acute or subacute challenges of the diagnosed individual (Kolostoumpis et al., Citation2015). Sacrificial feelings are often associated with deferring personal needs and implicated self-esteem and self-worth (Rusner et al., Citation2013).

The belief that engagement in meaningful doing is profoundly tied to matters of health and wellbeing is widely accepted in occupational therapy. According to Wilcock, ‘‘Doing, being, becoming and belonging = survival and health’’ (2006, p. 220). Humans engage in occupations to overcome discomfort, and to respond to environmental challenges (Kennedy & Davis, Citation2017; Saraswati et al., Citation2019). When considering the positive outcomes of occupational engagement, it can be deduced that occupations that positively contribute to the experiences of health and well-being are those that serve to meet an individual’s occupational needs (Doble & Caron, Citation2008). According to Sutton et al. (Citation2012), a central focus of occupational therapy practice should be to address the loss of freedom to engage freely in occupations that meet a person’s occupational needs (which are inevitably achieved by means of occupational engagement). Secondarily affected population groups (such as the partners of persons diagnosed with bipolar disorder) are indirectly influenced by the construct of mental health, which resultantly influences their ability to meet their occupational needs, resultantly influencing their occupational engagement.

Whilst Doble and Caron (Citation2008) propose that all humans have the same occupational needs (accomplishment, affirmation, coherence, pleasure, belonging, agency, and renewal), they simultaneously consider that the manifestation of these needs is subjective. An important consideration, however, is that occupational engagement is not inevitably positive, nor does it inextricably link to positive meaning. Persons may experience occupations as degrading, frustrating, unsatisfactory, dehumanizing, and humiliating (Hammell, Citation2017).

Person, occupation and/or environmental challenges present for partners of persons with bipolar disorder that pose a threat to achieving occupational needs, will additionally pose a risk to overall wellbeing and quality of life (Doble & Caron, Citation2008). Tension is likely to occur when the roles that one engages in are associated with complexities and several demands (such as when a partner assumes roles reflective of a caregiver), which can consequently lead to the experience of role overload (occurring when there is a discrepancy between one’s role demands and the resources - such as time - that one has available to fulfill these roles for the partner) (Bar & Jarus, Citation2015).

An important consideration when exploring positive and challenging experiences of occupational engagement, is the concept of occupational balance. Humans require a dynamic balance between doing and being, as being allows individuals to encounter their essence and humanness, which can offer a sense of deep fulfillment and peace (Wilcock, Citation1998). An additional proponent is the consideration of balance between relationships and solitude (Littman-Ovadia, Citation2019). Over engagement in the realms of doing and relationships with or for a diagnosed individual will cause occupational imbalance, posing threat to partners achieving a holistically fulfilling human experience (Littman-Ovadia, Citation2019).

The occupational engagement of populations that are indirectly influenced by the construct of mental health should be considered by occupational therapists. This article serves to highlight the positive and challenging lived experiences of occupational engagement of the partners of persons diagnosed with bipolar I disorder, thus contextualizing their occupational needs. The challenging experiences of occupational engagement outlined by research participants have implications for consideration by occupational therapist with regard to who the client in occupational therapy is (extending beyond persons diagnosed).

Materials and methods

Study design

Situated in the interpretivist paradigm, the aim was to understand, through a process of interpretation, the lived experiences of occupational engagement of partners of persons diagnosed with bipolar I disorder. As a result, Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) was used (Smith et al., Citation2009). Participants’ perspectives and meanings were sought and explored in complex discourse using through in-depth interviews guided by the Person-Environment-Occupation-Performance model (PEOP model) to enable the researcher to access and engage with participants’ reflections and interpretations authentically. There exists a dynamic relational interplay between the ‘Person’ and the ‘Environment’ which influences ‘Occupations’- either positively, or negatively (Baum et al., Citation2015). The PEOP model served to inform several questions included in the interview guide, so as to “gain an understanding of the person, the environments and contexts in which their occupations occur (and in which the client wishes to participate), and the demands of their occupations” (Joosten, Citation2015), thereby enabling a holistic understanding of the lived experience of occupational engagement for participants, including factors that served to facilitate and restrict engagement in the social context of being a partner to an individual diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

Despite the aim of IPA research being to explore the perspective of the participant, “such an exploration must necessarily implicate the researcher’s view of the world…” (Willig, Citation2013, p.260). The views of the researcher (as an occupational therapist and human/“meaning-making” being) were thus uncovered throughout the research process using a reflective journal (Willig, Citation2013). To authentically demystify the essence of the participants’ perspectives of occupational engagement, the double hermeneutic process was used, whereby the researcher aimed to make sense of the participants’ reflections of their experiences (thereby meaningfully co-constructing the reality of the participants’ lived experience) (Willig & Stainton-Rogers, Citation2017).

Participant selection and sampling procedure

The sample was selected purposively and included partners of persons with bipolar I disorder residing in South Africa who volunteered participation. Occupational therapists employed in public and private mental healthcare facilities in South Africa were contacted via an occupational therapy mental health interest group, wherein a general outline of the study and eligibility criteria were outlined. Contact details were made available for potential participants, and participants who made contact were provided with a detailed information sheet, demographic and consent forms (which they were required to complete and sign for participation to commence).

The following aspects were carefully considered when selecting participants; partners of persons with bipolar I disorder were selected, who were in an intimate relationship equal to or exceeding six months with an individual formally diagnosed (by a psychiatrist). Participants had to be willing to provide detailed descriptions of their lived experience in English. Participants were not excluded based on gender, culture, or age to allow for diverse experiences to enrich the study. The above suitability criteria ensured that all participants were inherently familiar with the phenomenon and that participants’ worldviews could be seen, heard, and intimately understood by sharing the same language as the researcher, ensuring that important nuances and subtleties were more likely to be included as a part of the data set.

The sample size in IPA studies is generally smaller than other qualitative research designs. According to Smith et al., a sample size of three to six participants is to be considered (2009). This study employed a sample size of four participants to ensure that detailed insights were sought and uncovered comprehensively. Due to their ideographic nature, IPA studies do not aim to reach data, meaning or code saturation, but rather serve to explore the particularity of a person’s lived experiences.

Data collection

Individual in-depth interviews were employed as the data collection instrument to enable a deep exploration of the participants’ lifeworld (Smith et al., Citation2009; Willig, Citation2013). The interviews with participants were approximately 60–90 minutes in length. Questions started as general and open-ended and gradually became more specific by encouraging the participants to elaborate on concepts being uncovered and shared. Specificity was additionally sought by using the PEOP model as a guiding framework, thereby focusing on the Person (such as emotive and psychological aspects, for example: “What motivates you to engage in the task/activity?”), Environment (primarily their social and cultural environments, for example: “What external factors support or hinder your engagement?”) and Occupation aspects brought forth by the participant during the interview (for example: “Are there other activities/tasks that take priority over this activity/task?”). It is important to note that the interview guide was not prescriptive but instead utilized to intentionally engage in dialogue, as guided by the specific participants’ narrative. Participants were encouraged to be honest in the interview process to enhance credibility. Additionally, the researcher consulted with experienced colleagues following each of the interviews conducted and throughout the research process, which enabled recognition of the interpretative turns employed by the researcher, and to receive alternative perspectives (Anney, Citation2014).

A virtual interview was conducted with participants individually. To ensure that participants felt comfortable, I encouraged them to enter the virtual interview from a physical space that felt safe to them (as far as realistically possible) and at a time convenient to them. Technological components were subjected to a test run, and a publicly available platform (Zoom) was utilized for ease of access. Raw data were audio-recorded (with participant consent) for later transcription and analysis using two audio-recording devices and saved onto a password-protected laptop and a password-protected Google Drive. All relevant forms (i.e., consent, biographical data, and interview forms) were stored electronically on a password-protected laptop and Google Drive. Data were only available to the research team.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed following the IPA analysis process (Smith et al., Citation2009). Systematic steps were taken once raw data had been collected; first, raw data was transcribed verbatim shortly after each interview and the transcript was read several times to enable data immersion; reflective notes gathered were read as well. After several re-readings, the researcher engaged in open coding to capture initial curiosities and freely engage with the data (Smith et al., Citation2009; Willig, Citation2013). Thereafter, a second stage of explorative coding was undertaken using ATLAS.ti 8. (Archive for Technology, Lifeworld and Everyday Language), encompassing descriptive, interpretive, and linguistic codes (which had been color-coded) (Smith et al., Citation2009).

The researcher captured comments, including descriptive comments (concerned with the content of what the participant had shared), linguistic comments (concerned with language use, i.e., how the participant had shared the information), and interpretive comments (i.e., how what had been shared spoke to the participant’s experience). Both the transcribed data and reflective journal were consulted when outlining interpretive comments.

Emergent themes were developed by clustering and collapsing explorative codes based on conceptual similarities to formulate sub-themes. Sub-themes were drafted across code groups (therefore, sub-themes included interpretive, linguistic, and descriptive codes), allowing for the sub-themes to be nuanced and layered (by exploring the what, how and meaning/s of what had been shared). Meaningful concise statements representative of the data were used as the labels of emergent sub-themes (Smith et al., Citation2009). Sub-themes that fit together led to the development of “super-ordinate”/main (Smith et al., Citation2009, p. 96) themes (Willig, Citation2013). The steps above were repeated for each interview (Smith et al., Citation2009; Willig, Citation2013).

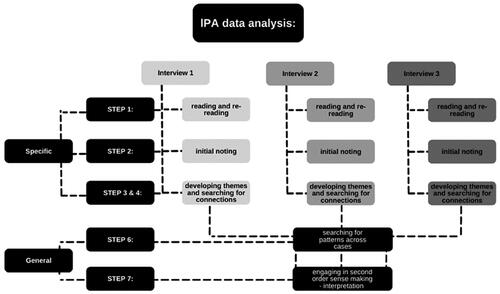

After being immersed in each specific case (due to the ideographic nature of IPA), the next step was that of seeking commonalities across participant codebooks, leading to codes, sub-themes and main themes being re-clustered or re-labelled- as necessary, to ensure accuracy across the data set. In some instances, similar meanings could not be inferred; this was noted on the combined code book and overtly stated as being inferred from a single participant’s transcript. In the final stage, the researcher played an active role in the interpretive process, as IPA involves a “double hermeneutic” process. The hermeneutics of empathy in the earlier stages were exercised (by attempting to understand the worldview of the participant authentically). At this stage, the hermeneutics of questioning were fore-fronted- and the researcher added to each of the outlined themes, informed by personal knowledge, worldviews, and reflections, thus bringing forth emerging subtleties (Smith et al., Citation2009). The diagram as represented in illustrates the ideographic nature of IPA, whereby each case was comprehensively explored individually before searching for commonalities among cases.

Ethics

The ethical considerations of Beneficence, Non-Maleficence Autonomy and Confidentiality were upheld in accordance with South Africa’s Department of Health ethics in health research (2015). Additionally, the research proposal was submitted to the university of Pretoria Health Research Ethics Committee (HREC) and ethical clearance had been obtained (ethics number: 508/2020).

Findings

Infringement, facilitators, occupational influence, external influence, and internal influence, were the five superordinate themes that emerged from the data, reflecting the voice of all participants. The findings can thus be considered representative of the participants’ collective experiences. In certain instances, explorations within a specific theme will not represent collective experiences, as they are linked to a particular participant’s experience. Due to the ideographic nature of IPA, personal experiential themes (reflecting the voice of a particular participant) are considered significant and have thus been included (Willig, Citation2013). The complexities of the participants’ collective narrative encompassed both challenging and positive experiences of occupational engagement. The themes consider internal, external, and occupational influences and their resultant impact/s on occupational engagement.

Demographic information

The four participants involved in this study met the eligibility criteria (being in a relationship with an individual diagnosed with bipolar I disorder), thus enabling intimate familiarity with the study’s phenomenon. The demographics are specified in the participant demographic information table (participant names have been replaced with pseudonyms) ().

Table 1. Participant demographic information.

Themes

Infringement

From the four participants’ narratives, feelings of being overwhelmed by contextual circumstances, which resultantly influenced occupational engagement negatively, were extensively communicated. Participants described that the need to attend to multiple demanding tasks and roles simultaneously negatively impacts engagement in other meaningful roles and tasks. Participants mentioned that the perceived need to be present for their diagnosed partner infringed on social participation and leisure, as indicated in the following participant excerpts, “My socialisation did take a bit of a knock. I don’t see my friends as much. I don’t spend as much time with my family. I was spending all my free time or anytime I had with him” (Kirsten), “You [I] don’t make an effort with the things that you [I] enjoy. I don’t go to the gym as much” (Matt). Kirsten’s meaningful relationships were negatively impacted during her partners depressive episode. Matt explored the need to “shut down” when his partner experienced acute symptoms, thus disengaging from previously meaningful occupations.

Participants explored that the need to attend to multiple demands simultaneously is exacerbated during periods whereby their diagnosed partners experience acute symptoms. James also experienced this, “The additional stress and pressure of work and then being in your home environment … that does drain you … if she is overwhelmed that day … the house responsibilities are with me.” Thus, when his partner was acutely symptomatic, James’ demands for engagement in instrumental activities of daily Living (IADL’s) significantly increased. Matt, who significantly values his role as a student, reflected on the interpersonal conflict that arises during manic episodes for his partner and explored the manner in which the conflict led to the development of acute symptoms of anxiety for him and resultantly negatively influenced his student role and ability to engage in the occupation of work, “I can’t really focus on university because I am trying to focus more on the relationship. So that does have a negative effect on my results….”

Participants explore that the need to “take on” more than their diagnosed partner is at times not met with acknowledgement, thus leading to feeling unappreciated, as reflected in the following excerpts, “I do everything … I don’t think that is visible to the people around me” (Sid), “I do sometimes feel a lack of support” (James), “I have never felt like I was a priority…” (Matt). Participants implied feeling unheard and unseen in the relationship (and larger still by their community and society). As a result of placing their own needs and feelings on the backburner, participants explored the manner in which they struggle to allocate time and energy to navigate their own occupational needs, often feeling that their partner’s needs supersede their own. The implication of sacrificing their own needs (to meet the needs of their partner) resulted in feeling consumed by circumstance/s (social contextual) and feeling as though their romantic relationship at times encroaches on their own inner world and their ability to engage in meaningful occupations.

Facilitators (physical and social)

Participants’ accounts of their lived realities revealed several factors that serve to facilitate engagement in occupations and further still, served to enhance their partner relationship dynamic. Social contextual factors were illustrated by participants as serving to enable occupational engagement as well as enabling participants to meet several occupational needs. The social context facilitating engagement included their partner (in some participants’ reflections), person’s external to the intimate relational dynamic, and in some instances connections to the wider world. Positively perceived social contexts served to foster the human need for belonging and connection. Participants explored that engagement with supportive persons external to their relationship space (whether family or friends) was perceived as enabling them to return to the relationship dynamic with more clarity and empathy. Matt and Kirsten sought out their families in times of adversity, “just knowing that they are there (family) … that is a big support for me, I also talk to my brother whenever I feel down” (Kirsten).

Sid considered belonging as extending beyond the social realm and persons who exist in concrete reality. Her experience of support and belonging was strongly present is her spirituality, “I feel connected (to God) … and that nobody can touch, even he (my partner) cannot and could never….” Participants additionally explored that despite the challenges in their intimate relationship space, their partners (in some cases) provided support, “My boyfriend is a big support. I know I wanna be in this (relationship) even though it’s difficult” (Kirsten).

Reflections additionally suggested the importance of balancing connection and independence in close relationships (which is in keeping with concepts of occupational balance and harmony). Boundaries capacitated participants with the ability to be more present for themselves (and, as a result, allowed for them to be more empathetic toward and present for their partners), “I have put a boundary in place that I am there for him, but I can’t be there all the time and I can’t be there for everything” (Kirsten). Boundaries and open communication had the effect of diagnosed partners assuming more independent responsibility in relation to their wellbeing and resultantly increased participants’ capacity to meet (and understand) their own occupational needs.

Finally, participants said that shared engagement in occupations (together with their partners) enhanced interpersonal relationship satisfaction and enhanced feelings of belonging and validation, “I feel when he helps me out that he makes an effort … and that gives me you know … that feeling of positivity or security” (Sid). James reflects on his role as a parent as a collective experience, “I’d say that being a parent was very difficult at first, but we’ve gotten the hang of it now,” allowing James to feel supported in a shared occupational engagement.

Occupational influence (productive occupations)

Across all participant interactions, the influence of “productive” occupations were reflected upon and perceived as simultaneously challenging, stressful, overwhelming (due to associated pressure), and meaningful (allowing participants to achieve occupational needs and positive affect). Participants at times alluded to a lack of occupational balance and disharmony as a result of productive occupations. Kirsten and Matt explored their student roles and feelings of being consumed by the demands associated with the role, “I feel like I barely have a life outside of uni” (Kirsten). Sid and James mentioned the financial demands placed on them in their partner role, “He (my partner) has a problem with handling money and ummm … budgeting. They are impulsive and … just like there’s no like … you know … there’s no responsibility…” (Sid). Sid dances between a sense of frustration and empathy in the verbatim above, acknowledging the difficulty that her partner faces whilst simultaneously acknowledging that the experience is challenging for her and places a strain on her financially.

Participants pointed out several positive experiences in relation to productive occupations including, the ability to meet basic survival and security needs, achieving a sense of competency achievement and fulfillment, participants (in some instances) alluded to achieving the “flow” state through work when the level of challenge at work was “just right,” and the experience of positive meaning. Sid explores feelings of competency when engaged in cooking (as a work occupation), “It gives me a feeling … a feeling of … I can do something right.” The excerpt above implies that when cooking, Sid’s experience contrasts how she often feels in her intimate relationship dynamic (wherein she expressed feelings of inadequacy and unworthiness). When she is engaged in work, she experiences a sense of mastery which induces a positive sense of self.

Participants perceived that engaging in alternate occupations (outside of their day-to-day occupational demands), served to meet occupational needs of renewal and solitude allowing them a pleasant “escape,” “a lot of the time I think we are so hyper focused on the fact that we are stressed out in one space that we neglect doing anything else … but actually, you need that (doing something else), you need an escape” (James). Meaningful occupations external to productive occupations and their partner role served to positively enhance wellbeing.

External influence

The impacts of “external” reality (context) on occupational engagement were primarily explored within this theme. Social contextual factors were particularly impactful with regard to influencing the occupational engagement. Participants explored the manner in which the diagnosis not only informed the lived experience of the individual diagnosed, but additionally transcended to inform their lived reality.

James explored the manner in which navigating the journey with his partner’s diagnosis required that he faces and contends with the reality of the diagnosis in her reality (and his). Kirsten further elaborated on the impact of the diagnosis being real and transcending to inform her own reality “at the end of the day it’s very much my reality too…being in a relationship with a someone who has a mental disorder…, it is a part of your [my] life.”

Participants deeply engaged with the concept of stigma and the influence thereof on occupational engagement (particularly in relation to engagement in social activities) during the interviews. Participants inferred that stigma and societal perceptions affect their interpersonal relationship dynamic (whether consciously or subconsciously) and interactions within their community.

Internal influence (the influence of the “inner world”)

This theme explores participants’ interpretations, thoughts and perceptions of their inner world and the influence thereof on occupational engagement. Internal influence led to both positive and challenging experiences of occupational engagement. Participants reflected that their values influenced engagement in various day to day occupations, and that creating positive shifts within their relationship space motivated occupational engagement. “A big value is where you feel like you can contribute positively, it makes you feel good, so it makes stressful circumstances or that feeling of overwhelm easier…” (James). James’ statement was agreed on by Sid who echoed, “Nurturing the people around me … that motivates me … seeing other people happy …it contributes positively to my relationship too.”

Participants preferred coping mechanisms (employed to cope with social contextual challenges) indirectly influenced occupational engagement. The coping mechanisms most often referenced by participants alluded to the use of denial, avoidance, and escapism. The use of these coping mechanisms whilst highlighted (to some degree) in each of the participants’ transcripts were particularly prevalent in the interview conducted with Sid who has been in a relationship with her partner for 29 years (for the majority of which, he had not been diagnosed or received intervention). Sid alluded to the use of escapism and avoidance particularly on several occasions as seen in the quotation that follows, “Sometimes I want to sit in bed and ponder about nothing in specific … Do you know what I sometimes do? I picture a chalkboard and I picture all the things that he said and everything he did and things that annoy me … I picture an eraser and I start to erase the entire board; I wipe it clean … when I forget to do this, I get nightmares and then I’m like okay … go back to the chalkboard (long pause) …” (Sid). There seems to be a subtle implicit indication that aspects negatively perceived in the intimate relationship dynamic cannot be dealt with through direct confrontation. She thus describes the use of visualization techniques to dissociate from circumstances (escapism and avoidance). She seeks the outcomes and security that she desires in daydream or fantasy states as she perceives that these aspects (safety, conflict resolution, security etc.) are out of her reach in tangible reality). Despite the focus of this theme being on person factors, persons are not context independent, and thus, values, meaning/s, coping and participants’ perception of self will have a resultant influence on occupational choice, occupational engagement and participants’ insights that will influence their perception of occupational harmony.

Discussion

The findings served to highlight several positive and challenging experiences of occupational engagement. It is important to note that the findings relate specifically to the four participants of this study and thus, the findings and resultant discussion cannot be generalized but rather considered in relation to partner and secondarily affected population groups.

The challenging landscape of occupational engagement

The challenging landscape of occupational engagement relates to the themes: Infringement, Occupational Influence, External Influence, and Internal Influence, wherein participants explored challenging experiences of occupational engagement. Partners form an integral component of the diagnosed individual’s context, and according to literature, are more likely to assume caregiver like responsibilities (assuming responsibility for the needs and feelings of their diagnosed partner to varying extents) (Greer & Cohen, Citation2018). As a result, partners may assume dual roles in their intimate relationship (assuming the role of a romantic partner and caregiver). Role duality was inferred by participants (in the theme Infringement) which translated within the relationship space to cause negative impact and overwhelm, thereby influencing occupational engagement negatively. From the participants’ accounts, it is evident that constantly being engaged in the narrative of another can be a frustrating experience and infringed on participants’ ability to achieve their occupational needs. Granek et al. (Citation2016) found that partners of persons with bipolar disorder often reported self-sacrificial behaviors. In this study, self-sacrifice led to partners not having sufficient resources (with regard to time and energy) to navigate their own feelings and needs due to the majority of their resources being dedicated to the “other” (their diagnosed partner).

Being in an intimate relationship with a partner diagnosed with bipolar disorder, was found to impact social participation (among other meaningful categories of occupation), as explored in the theme’s Infringement and External Influence, reflected in participants’ accounts of their lived experience whereby they report social withdrawal and reduced engagement (Boyers & Rowe, Citation2018; İnanlı et al., Citation2020). The presence of a mood disorder can lead to exposure to traumatic cues, causing feelings of fear, shame, self-blame, anger, and resentment. Affective shifts in participants’ contexts indirectly infringed on engagement in productive and restorative occupations, as a result of anticipatory anxiety. Fear during manic episodes and anticipatory anxiety correlates with literary sources which outline that caregivers experience symptoms of mania as more distressing (Granek et al., Citation2016; Sheets & Miller, Citation2010).

Participants communicated challenges experienced in relation to achieving and maintaining occupational balance (in Infringement and Occupational Influence), resultantly influencing their engagement in meaningful roles and occupations. Occupational balance during periods of misalignment (between the internal and external realms) may feel difficult for people to achieve (Liu et al.,Citation2021). Participants felt a sense of internal tension or conflict during periods whereby multiple demands presented themselves simultaneously. These demands felt exacerbated during periods whereby their diagnosed partners were acutely symptomatic which is in keeping with a study conducted by Spoelma et al. (Citation2023) who outline that “caregivers had high rates of ‘caring more’ for their care-recipients during illness episodes (rates exceeding 70% in both depressed and hypo/manic phases).”

According to Littman-Ovadia (Citation2019), over-engagement with certain characteristics of occupations can lead to the experience of occupational imbalance. Doing and relationship domains of engagement (traditionally) pose higher demands on the human form engaging, thus causing a sense of disharmony when taking away from the individuals’ ability to engage in the complimentary states of being and solitude. The state of engagement in the relationship domain during periods whereby the participants’ diagnosed partners were symptomatic (or experiencing an acute affective state) typically increased, causing overwhelm, as they perceived that their diagnosed partner required increased support. The states of being and solitude (which offer individuals an opportunity to be contemplative, retreat inward, and more deeply connect with the self) were experienced as more difficult for participants to achieve when productive occupations or their relationship felt overwhelming (Littman-Ovadia, Citation2019).

Participants stated that self-sacrifice can, however, be a rewarding experience when you have made a positive difference for another (as explored in Internal Influence). According to a study conducted by Krupp and Maciejewski (Citation2022), there are two opposing ends of a spectrum in relation to the concept of self-sacrifice, namely, altruism and spite. Over time, if the perceived benefits of self-sacrifice outweigh the costs, self-sacrifice is perceived positively (as altruistic), and many people report experiencing satisfaction, purpose and meaning from engaging in occupations that provide care to others (Hammell, Citation2014). Whilst costs outweighing benefits leads to the development of negative affect (spite) (Krupp & Maciejewski, Citation2022). The above finding is consistent with James’ reflection (whereby he perceives self-sacrifice as beneficial), but also with the reflections of other participants, which err on the other end of the spectrum, due to the perception of the cost/s of self-sacrifice outweighing the benefits, noted in Infringement. Both altruism and spite can be considered to resultantly impact participants’ occupational engagement and their perceptions thereof (whether positive or negative).

In the theme, External Influence, participants assert that their partners diagnosis is a part of their reality and fabric of life as well (by association and constant interaction with the diagnosed individual). This is in keeping with literature which asserts that the impact (inclusive of challenges and stressors) are significant for the diagnosed individual, but also extend to impact persons in their daily context/s (Granek et al., Citation2016). Corroborating literature which implies that psychiatric stigma extends beyond the diagnosed individual (to additionally implicate persons within their primary social groups), participants allude to experiencing the impact of stigma (Hawke et al., Citation2013), resultantly influencing occupational engagement (specifically in relation to social occupations).

Facilitators enhancing engagement in occupations

Facilitators enhancing engagement in occupations relates to the themes: Facilitators, Occupational Influence, and Internal Influence, wherein participants explored intrinsic and extrinsic factors that served to support occupational engagement. Interpersonal support explored in Facilitators, served to enhance participants’ engagement in various occupations and enabled the achievement of occupational needs (particularly the need for belonging and companionship, which is resultantly associated with the positive meaning dimension of allowing for social connection) (Baum et al., Citation2005; Clouston, Citation2018; Doble & Caron, Citation2008). Previous studies contend that psychological and social support provision enhance wellbeing and quality of life, which is additionally in alignment with participants’ reflections, as they describe feeling supported, heard, and understood when engaged in positively perceived interactions, with their partner or other support networks (Baum et al., Citation2005; Boucher et al., Citation2016). Additionally, the role that occupational engagement plays in enhancing relationships and fostering a sense of belonging is reflected in several studies (Hammell, Citation2017; Roberts & Bannigan, Citation2018). Collective occupational engagement (engagement in occupation with or for others) in autotelic occupations serves to foster connections (Roberts & Bannigan, Citation2018). Duncan illustrates that ‘‘doing valued occupations with and for others fosters a sense of connectedness—a sense of belonging, purpose and meaning (2004, p.198). The preceding statements align with Sid, Kirsten, and James’ reflections of feeling a sense of validation in their romantic relationships during periods of shared occupational engagement.

Additionally, open communication in conjunction with asserting boundaries was found to be impactful in allowing participants to develop assertiveness skills and to “be there for themselves,” thereby enabling them to meet their occupational needs. Open communication (about thoughts, fears, feelings, and needs) enhances didactic relationship coping and enables enhanced conflict resolution, as it increases the possibility of taking effective action (Kiełek-Rataj et al., Citation2020).

According to literature, personal values (such as those explored in the theme Internal Influence) serve as motivational roots for attitudes and behaviors when engaging in occupations (Sato et al., Citation2021). Considering that belonging needs pose greater motivation for individuals’ engagement in occupations, cultural and societal values held by persons could, therefore strongly influence occupational attitudes and behaviors (Doré & Caron, Citation2017; Ramugondo, Citation2017). This correlates with participants’ outlines of valuing financial provision for their immediate social microcosm, providing care and nurturing those in their immediate daily proximity (as outlined by James and Sid). Additionally, provision toward participants’ partners needs and feelings were associated with autotelic meanings such as (Clouston, Citation2018):

Inducing a positive sense of self, which correlates with Sid’s and James’ perception of altruistic engagement through creating an environment of positivity and engaging in occupations (such as work and IADL’s) to positively contribute within their intimate relationship context.

Inducing feelings of being valued by others had additionally been alluded to by both Sid and James, motivating engagement in work and IADL’s.

Participants’ transcripts imply the concepts of occupational balance and harmony and how engagement in alternate occupations (beyond one’s primary roles and occupations) can aid in achieving these states, as noted in Occupational Influence. Consistent with participant reflections, Doble and Caron (Citation2008) note that occupations which serve to enable the achievement of the occupational need for renewal, reclamation and relief from interpersonal and occupational stressors enhance wellbeing. Littman-Ovadia (Citation2019), further explore that occupational engagement that enables the states of being and solitude, allow for engagement in the states of doing and relationships with an increased sense of harmony, ease, and perceived balance, consistent with participants’ explorations.

Ramugondo (Citation2017) reflects that occupations that serve to enhance eudemonic well-being are integral to the experience of health and wellbeing. Eudemonic wellbeing which focuses centrally on the experience of social well-being (resulting from pursuing experiences that provide purpose and meaning which extends beyond individualistic pleasure and gratification) (Doré & Caron, Citation2017; Ramugondo, Citation2017). The exploration of well-being above corroborates with participants’ reflections, in Facilitators and Internal Influence, as although from surface level exploration, participants’ engagement is done for the sake of pleasure and gratification, the underlying common motivator is that of engagement for the sake of enabling more cantered engagement in core occupational roles (such as that of being a partner, student etc.).

Dynamic engagement between person, environment and occupation served to influence participants’ occupational engagement (either positively or negatively) and their perception thereof (Baum et al., Citation2015).

Limitations

The socioeconomic statuses of the study participants were not holistically representative of the South African context, as most of the South African population fall within the lower income bracket. Thus, the participants’ daily experiences may differ from that of the majority of the country’s population. Future research may thus consider a more holistic consideration of population dynamics. The participants included in this study were partners of persons with bipolar I disorder who are currently in a relationship with the diagnosed individual. As such, the nature and extent of occupational engagement of the participants involved in this study may not be fully representative of partners who have experienced relationship disruptions and raptures. Considering the perspective of persons previously in relationships with diagnosed individuals and the influence thereof on their occupational engagement may be worth considering in future research.

Conclusion

Occupational therapy processes are carefully considered and applied to “direct” client populations in occupational therapy (typically encompassing persons with diagnoses). However, the consideration of who the client is in occupational therapy ought to be considered more broadly. This article served to contextualize the positive and challenging experiences of occupational engagement for participants as informed by their lived experience. A summary of the challenging influences and protective factors explored by participants is outlined in .

Table 2. A summary of challenges and protective factors emerging from the study.

Future research using more diverse participants to explore the occupational needs of secondarily affected and contextually impacted populations is recommended to enable occupational therapists to better understand the occupational needs and factors influencing the occupational engagement of these groups of persons. In so doing, broadening the concept of who the client is in the occupational therapy context may be more holistically considered. This article contributes to current literature, which highlights that occupational engagement is a human rather than a diagnostic consideration.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (137.9 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anney, B. (2014). Ensuring the quality of the finds of qualitative research: Looking at the trustworthiness criteria. Journal of Emerging Trend in Educational Research and the Policy Studies. JETERAPS, 5, 272–281.

- Bar, M. A., & Jarus, T. (2015). The effect of engagement in everyday occupations, role overload and social support on health and life satisfaction among mothers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(6), 6045–6065. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120606045

- Baum, C., Christiansen, C., & Bass, J. (2005). Occupational therapy: performance, participation, and well-being. (3rd ed.). Slack publications.

- Baum, C., Christiansen, C., & Bass, J. (2015). Person-environment-occupational performance (PEOP) model. In C. Christiansen, C. Baum, J. Bass, Occupational therapy: Performance, participation, well-being. (4th ed.). Thorofare, NJ: Slack Publications.

- Boucher, M. E., Groleau, D., & Whitley, R. (2016). Recovery and severe mental illness: The role of romantic relationships, intimacy, and sexuality. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 39(2), 180–182. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000193

- Boyers, G. B., & Rowe, L. S. (2018). Social support and relationship satisfaction in bipolar disorder. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP: Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 32(4), 538–543. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000400

- Clouston, T. J. (2018). Creating meaning in the use of time in occupational therapy. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 81(3), 127–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022617733245

- Doble, S., & Caron, J. (2008). Occupational well-being: Rethinking occupational therapy outcomes. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. Revue Canadienne D'ergotherapie, 75(3), 184–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841740807500310

- Doré, I., & Caron, J. (2017). Santé mentale: Concepts, mesures et déterminants. Santé Mentale au Québec, 42(1), 125–145. https://doi.org/10.7202/1040247ar

- Esan, O., & Esan, A. (2015). Epidemiology and burden of bipolar disorders in Africa: A systematic review of available data from Africa. European Psychiatry, 30, 546. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0924-9338(15)30430-2

- Granek, L., Danan, D., Bersudsky, Y., & Osher, Y. (2016). Living with bipolar disorder: The impact on patients, spouses, and their marital relationship. Bipolar Disorders, 18(2), 192–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.12370

- Greer, H., & Cohen, J. N. (2018). Partners of individuals with borderline personality disorder: A systematic review of the literature examining their experiences and the supports available to them. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 26(4), 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0000000000000164

- Hammell, K. W. (2014). Belonging, occupation, and human well-being: An exploration. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. Revue Canadienne D'ergotherapie, 81(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417413520489

- Hammell, K. W. (2017). Opportunities for well-being: The right to occupational engagement. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. Revue Canadienne D'ergotherapie, 84(4-5), 209–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417417734831

- Hawke, L. D., Parikh, S. V., & Michalak, E. E. (2013). Stigma and bipolar disorder: A review of the literature. InJournal of Affective Disorders, 150(2), 181–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.030

- Idstad, M., Ask, H., & Tambs, K. (2010). Mental disorder and caregiver burden in spouses: the Nord-Trøndelag health study. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/10/516

- İnanlı, İ., Çalışkan, A. M., Tanrıkulu, A. B., Çiftci, E., Yıldız, M. Ç., Yaşar, S. A., & Eren, İ. (2020). Affective temperaments in caregiver of patients with bipolar disorder and their relation to caregiver burden. Journal of Affective Disorders, 262, 189–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.10.028

- Joosten, A. V. (2015). Contemporary occupational therapy: Our occupational therapy models are essential to occupation centred practice. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 62(3), 219–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12186

- Joutsenniemi, K., Moustgaard, H., Koskinen, S., Ripatti, S., & Martikainen, P. (2011). Psychiatric comorbidity in couples: A longitudinal study of 202, 959 married and cohabiting individuals. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 46(7), 623–633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-010-0228-9

- Kennedy, J., & Davis, J. A. (2017). Clarifying the construct of occupational engagement for occupational therapy practice. OTJR: occupation, Participation and Health, 37(2), 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/1539449216688201

- Kiełek-Rataj, E., Wendołowska, A., Kalus, A., & Czyżowska, D. (2020). Openness and communication effects on relationship satisfaction in women experiencing infertility or miscarriage: A dyadic approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5721. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165721

- Kolostoumpis, D., Bergiannaki, J. D., Peppou, L. E., Louki, E., Fousketaki, S., Patelakis, A., & Economou, M. P. (2015). Effectiveness of relatives psychoeducation on family outcomes in bipolar disorder. International Journal of Mental Health, 44(4), 290–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207411.2015.1076292

- Krupp, D. B., & Maciejewski, W. (2022). The evolution of extraordinary self-sacrifice. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-04192-w

- Littman-Ovadia, H. (2019). Doing–being and relationship–solitude: A proposed model for a balanced life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(6), 1953–1971. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-0018-8

- Liu, Y., Zemke, R., Liang, L., & Gray, J. M. L. (2021). Occupational harmony: Embracing the complexity of occupational balance. Journal of Occupational Science, 30(2), 145–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2021.1881592

- McDougall, C., Buchanan, A., & Peterson, S. (2014). Understanding primary carers’ occupational adaptation and engagement. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 61(2), 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12076

- Morris, K., & Cox, D. L. (2017). Developing a descriptive framework for “occupational engagement. Journal of Occupational Science, 24(2), 152–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/14427591.2017.1319292

- Ramugondo, E. (2017). Occupational therapy association of South Africa position statement: Spirituality in occupational therapy. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 48(3), 64–65.

- Roberts, A. E. K., & Bannigan, K. (2018). Dimensions of personal meaning from engagement in occupations: A metasynthesis. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. Revue Canadienne D'ergotherapie, 85(5), 386–396. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417418820358

- Rowe, L. S., & Morris, A. M. (2012). Patient and partner correlates of couple relationship functioning in bipolar disorder. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP: journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 26(3), 328–337. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027589

- Rusner, M., Carlsson, G., Brunt, D., & Nyström, M. (2013). Towards a more liveable life for close relatives of individuals diagnosed with bipolar disorder. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 22(2), 162–169. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2012.00852.x

- Saraswati, J. M. R., Milbourn, B. T., & Buchanan, A. J. (2019). Re-imagining occupational wellbeing: Development of an evidence-based framework. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 66(2), 164–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12528

- Sato, N., Watanabe, K., Nishi, D., & Kawakami, N. (2021). Associations between personal values and work engagement: A cross-sectional study using a representative community sample. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 63(6), e335–e340. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000002209

- Sheets, E. S., & Miller, I. W. (2010). Predictors of relationship functioning for patients with bipolar disorder and their partners. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP: journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 24(4), 371–379. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020352

- Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Spoelma, M. J., Ponte, K. M., & Parker, G. (2023). Phase-based concerns of caregivers for individuals with a bipolar disorder. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 69(6), 1472–1480. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207640231164285

- Sutton, D. J., Hocking, C. S., & Smythe, L. A. (2012). A phenomenological study of occupational engagement in recovery from mental illness. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. Revue Canadienne D'ergotherapie, 79(3), 142–150. https://doi.org/10.2182/cjot.2012.79.3.3

- Wilcock, A. (1998). Occupation for Health. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61(8), 340–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802269806100801

- Wilcock, A. (2006). An occupational perspective on health. (2nd ed.). Slack.

- Willig, C. (2013). Introducing qualitative research in psychology. McGrawHill International.

- Willig, C. & Stainton-Rogers, W (Eds) (2017). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research in psychology. (2nd ed). SAGE.

- World Health Organisation. (2020). Mental disorders. [online] https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders.