Keywords:

A 7-year-old, 35 kg, intact female springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis) was presented to the Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital, ‘College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Florida’, for evaluation of a firm ventral cervical mass. The animal exhibited minimal clinical signs of disease; the swelling did not seem painful but appeared to interfere with the movement of food down the esophagus and normal eructation. The springbok was housed in a large open-field enclosure with a male springbok and two West African crowned cranes (Balearica pavonina).

Anesthesia was induced in the springbok via dart with a combination of medetomidineFootnote1 (0.1 mg/kg BW), midazolamFootnote2 (0.1 mg/kg BW), and ketamineFootnote3 (5.7 mg/kg BW) administered intramuscularly. The animal was intubated and maintained with isofluraneFootnote4 in oxygen. Physical examination confirmed a large, discrete, slightly mobile, firm subcutaneous mass in the caudoventral neck extending from the thoracic inlet to the mid-cervical region. A blood sample submitted for a complete blood count and plasma biochemical panel revealed no abnormalities. A fine-needle aspirate from the mass submitted for cytologic examination was consistent with hemorrhage.

Computed tomographyFootnote5 (CT) with and without intravenous contrast,Footnote6 revealed a large, 16 × 11 × 8 cm, well-defined, oval, heterogeneous soft tissue attenuating mass. It extended from the level of cervical vertebra five to the thoracic inlet and was causing moderate dorsal compression and displacement of the cervical trachea (). The esophagus, jugular veins, and carotid arteries were identified and seen coursing around the mass, as were multiple tortuous vascular structures at the cranial aspect. There were multiple septate regions within the mass. Large, irregularly marginated, noncontrast-enhancing regions were noted centrally. The superficial cervical lymph nodes were within the normal limits. Based on the clinical presentation and CT scan appearance, differential diagnoses included ectopic thyroid, lymphoma, soft tissue sarcoma, hematoma, and less likely a cyst. Surgical exploration and marginal excision were recommended.

Figure 1. Transverse and sagittal CT images of a cervical thymoma. ( a) Thymoma. (b) Cervical trachea.

A ventral, cervical-midline incision was made and the platysma and sternohyoideus muscles were split on midline. A large, tan-to-brown in color, well-encapsulated, moderately vascular mass was present extending from the mid-cervical region to the cranial-most aspect of the thoracic inlet. A plane was created primarily with blunt-finger dissection around the periphery of the mass. Vital structures, including the carotid sheath, were palpated intermittently to avoid injury. Blunt and sharp dissection was continued until the mass was freed from its attachments. Hemostasis was obtained using surgical hemoclips and radiofrequency cautery. The left jugular vein was ligated due to its association with the mass. All other vital structures were preserved during the marginal excision. Two separate pale masses, thought to be lymph nodes, near the thoracic inlet measuring 1–2 cm were also marginally excised. The surgical defect was lavaged, suctioned, and explored to insure no residual hemorrhage. The sternohyoideus and platysma muscles were closed using 3-0 biosynFootnote7 in a simple continuous pattern. The subcuticular tissue was closed using 4-0 biosyn7 in a simple continuous pattern. The skin was sealed using cyanoacrylateFootnote8. All masses were submitted for histopathological evaluation.

During the surgical excision of the mass, ketamine3 (2.8 mg/kg BW) and cefazolinFootnote9 (25 mg/kg BW, q 90 mins) were administered intravenously. No significant intraoperative anesthetic or surgical complications occurred. Postoperatively, the medetomidine was reversed with atipamezoleFootnote10 (0.5 mg/kg BW, IM), and buprenorphineFootnote11 (0.02 mg/kg BW, IM) was administered for analgesia. The springbok was transported back to the zoo and recovered uneventfully.

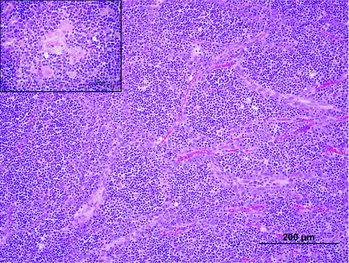

The histologic findings were consistent with a lymphocyte-predominant thymoma (). The mass was well demarcated, encapsulated, and divided into irregular lobules with sheets of homogenous round cells on a fine, fibrovascular stroma. The cells were small with scant eosinophilic cytoplasm and distinct cell borders. The nuclei were round to ovoid with coarsely clumped chromatin and a single-eosinophilic nucleolus. Mitotic figures were 5 per 10 400× fields. Scattered within the mass were small to medium nests and bundles of epithelial cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and large ovoid nuclei with vesiculate chromatin that occasionally formed Hassall's corpuscles (thymic corpuscles). In addition, there were small numbers of multifocal, variably sized cysts lined by a single layer of attenuated epithelium. The cysts contained abundant eosinophilic, granular to flocculent material (proteinaceous material). The neoplastic cells did not extend into or beyond the capsule with no lymphatic or vascular invasion observed.

Figure 2. Photomicrograph of the cervical thymoma. The mass was composed of sheets of homogenous round cells, divided into irregular lobules by dense lightly eosinophilic fibrous to dense collagenous connective tissue. Scattered within the mass were small-to-medium nests and bundles of epithelial cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and large ovoid nuclei with vesiculate chromatin that occasionally formed Hassall's corpuscles (inset).

In the smaller mass, there was mild hyperplasia of cortical lymphoid nodules. There were medullary sinuses with histocytes and numerous hemosiderophages. These findings were consistent with lymphoid hyperplasia and sinus histiocytosis of a cervical lymph node.

Visual recheck examinations were performed at 7, 14, and 28 days following surgery. A noticeable swelling developed in the dependent cervical region by day 7. This was thought to be a seroma that did not appear to adversely affect the springbok. The swelling resolved by 1 month, and the animal continued to do well 8 months postoperatively.

This appears to be the first documented case of a cervical thymoma in an antelope species with successful surgical treatment. The thymomas are a neoplasm of the thymic epithelium with various degrees of benign lymphocytic infiltration (Patnaik et al. Citation2003; Dengues et al. Citation2008; Zitz et al. Citation2008; Faisca et al. Citation2011). They are usually slow growing, noninvasive and infrequently metastasized (Patnaik et al. Citation2003; Dengues et al. Citation2008; Zitz et al. Citation2008; Faisca et al. Citation2011). The thymus is a lymphoepithelial, lobular immunological organ. Embryologically, it develops from the third and fourth pharyngeal pouches and then begins its descent along the cervical neck where it eventually reaches the cranial mediastinum (Tovi & Mares Citation1978; Dengues et al. Citation2008; Zitz et al. Citation2008; Amodeo et al. Citation2013). The most commonly observed location of thymomas in both humans and domestic animals is in the cranial mediastinum, which is the end location of the thymus following its descent during development.

Although the thymus is usually located in the cranial mediastinum, when it incompletely or fails to descend, it can be found aberrantly along its path of descend where it sequesters from the main gland and implants in the surrounding tissue (Patnaik et al. Citation2003). Cervical thymic tissue is most commonly isolated along a line from the angle of the mandible extending to the manubrium or around the thyroid gland (Tovi & Mares Citation1978). Ectopic thymic tissue usually remains dormant but has been rarely observed to form thymomas. The incidence of cervical thymomas in human medicine is only 4%, and fewer than five cases have been reported in domestic animals (Dengues et al. Citation2008; Amodeo et al. Citation2013).

Cranial mediastinal thymomas are commonly diagnosed in dairy goats, but reports on cervical thymomas were not identified (Hadlow Citation1978; Olchowy et al. Citation1996; Matthews Citation2009). The cause and individual predilection for cervical thymoma may be unique among species.

The most commonly presenting complaints are nonspecific, as seen with the springbok, and are due to the effects of a space-occupying mass compressing neighboring tissues, for example, dyspnea from tracheal compression. Depending on the tumor location, an intermittent cough, difficulty swallowing, or signs consistent with a cranial mediastinal mass may be seen (Tovi & Mares Citation1978; Rae et al. Citation1989).

Despite the location of the mass, the CT characteristics are similar to what has been reported in people and in small animals. Due to their large size, thymomas will often displace regional anatomy as was seen in this case. Contrast enhanced CT, and specifically CT angiography, is preferred over unenhanced CT to accurately assess vascular invasion, which has been reported with more aggressive tumor types (Yoon et al. Citation2004; Maher & Shepard Citation2005). Thymomas are typically described as large, solitary masses that are encapsulated with a well-defined fibrous capsule (Takahashi & Al-Janabi Citation2010). They have mild-to-moderate contrast enhancement with multifocal central regions of low attenuation representing areas of necrosis or cyst formation (Takahashi & Al-Janabi Citation2010).

Since cytological and histological evaluations of small biopsy samples are often misleading, complete surgical excision and histological evaluation of suspected thymomas are recommended (Takahashi & Al-Janabi Citation2010). Prognosis following complete surgical removal is good and has been shown to be inversely related to the invasiveness of the mass, the percent of epithelial cell composition, and the mitotic index in both humans and animals (Tovi & Mares Citation1978; Zitz et al. Citation2008). A study reports a 3-year survival rate of 74% in cats and 42% in dogs, following complete surgical excision (Zitz et al. Citation2008).

This is the first report of an extrathoracic thymoma in a springbok. Marginal surgical excision, guided by contrast CT, was an effective treatment and should be considered in similar cases.

Notes

1. Dormitor, Division of Pfizer Inc. New York, NY 10017, USA.

2. Midazolam, West-ward Pharmaceutical Corp., Eatontown, NJ 07724, USA.

3. Ketaset, Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, IA 50501, USA.

4. Isoflurane, Piramal Healthcare Limited, Bethlehem, PA 18017, USA.

5. CT, Toshiba Aquilion 8, Tustin, CA 92780, USA.

6. Omnipaque; GE Healthcare, Princeton, NJ 08540, USA.

7. Covidien, Mansfield, MA 02048, USA.

8. Vetbond; 3M Co, Saint Paul, MN 55144, USA.

9. Sandoz Inc., Princeton, NJ 08540, USA.

10. Pfizer Animal Health, New York, NY 10017, USA.

11. Reckitt Benchkiser Pharmaceutical Inc., Richmond, VA 23235, USA.

References

- Amodeo G, Cipriani O, Orsini R, Scopelliti D. 2013. A rare case of ectopic laterocervical thymoma. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 41:7–9.

- Dengues EG, Amarilla SP, Grau I, Werhle AS, Kegler K, Cino AG, Diaz AAR. 2008. Mixed thymoma in a German shepherd dog. Braz J Vet Pathol. 1:73–76.

- Faisca P, Henriques J, Dias TM, Resende L, Mestrinho L. 2011. Ectopic cervical thymic carcinoma in a dog. J Small Anim Pract. 52:266–270.

- Hadlow WJ. 1978. High prevalence of thymoma in the dairy goat. Report of seventeen cases. Vet Pathol. 15:153–169.

- Maher MM, Shepard JA. 2005. Imaging of thymoma. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 17:12–19.

- Matthews JG, editor. 2009. External swellings. In: Diseases of the goat. 3rd ed. Ames: Wiley-Blackwell; p. 148–160.

- Olchowy TW, Toal RL, Brennemen KA, Slauson DO, McEntee MF. 1996. Metastatic thymoma in a goat. Can Vet J. 37:165–167.

- Patnaik AK, Lieberman PH, Erlandson RA, Antonescu C. 2003. Feline cystic thymoma: a clinicopathologic immunohistologic, and electron microscopic study of 14 cases. J Feline Med Surg. 5:27–35.

- Rae CA, Jacobs RM, Couto CG. 1989. A comparison between the cytological and histological characteristics in thirteen canine and feline thymomas. Can Vet J. 30:497–500.

- Takahashi K, Al-Janabi NJ. 2010. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of mediastinal tumors. J Magn Reson Imaging. 32:1325–1339.

- Tovi F, Mares AF. 1978. The aberrant cervical thymus. Am J Surg. 136:631–637.

- Yoon J, Feeney DA, Cronk DE, Anderson KL, Ziegler LE. 2004. Computed tomographic evaluation of canine and feline mediastinal masses in 14 patients. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 45:542–546.

- Zitz JC, Birchard SJ, Couto GC, Sami VF, Weisbrode SE, Young GS. 2008. Results of excision of thymoma in cats and dogs: 20 cases (1984–2005). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 232:1186–1192.