Abstract

Objectives: We aimed at exploring the wishes of Dutch donor-conceived offspring for parental support, peer support and counseling and sought to contribute to the improvement of health care for all parties involved with assisted reproductive technologies.

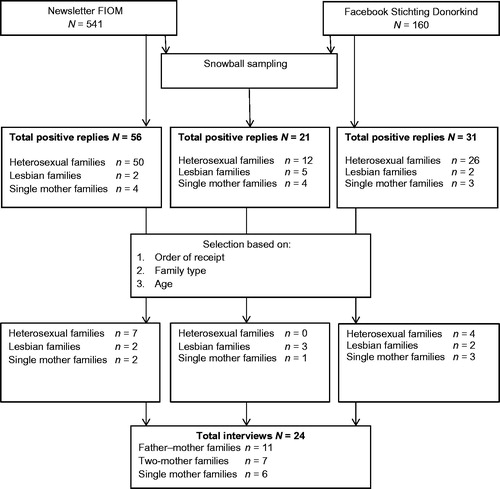

Methods: We held semi-structured in-depth interviews with 24 donor-conceived offspring (Mage = 26.9, range 17–41) born within father–mother, two-mother and single mother families. The majority of the donor offspring was conceived with semen of anonymous donors. All offspring were recruited by network organizations and snowball sampling. The interviews were fully transcribed and analyzed using the constant comparative method.

Results: Donor-conceived offspring wished that their parents had talked openly about donor conception and had missed parental support. They wished that their parents would have received counseling before donor sperm treatment on how to talk with their children about donor conception in several stages of life. They valued the availability of peer contact to exchange stories with other donor-conceived offspring and would have liked assistance in getting access to trustworthy information about characteristics and identifying information of their donor. Donor-conceived offspring wished to know where to find specialist counseling when needed.

Conclusions: Peer support and counseling by professionals for donor-conceived offspring should be available for those who need it. The findings also support professional counseling for intended parents before treatment to improve parental support for donor-children.

Introduction

Donor sperm treatment (DST) enables infertile heterosexual couples to become parents, but also supports lesbian couples and single women to build a family. In the past, semen donors were anonymous and DST was surrounded by secrecy towards family, friends and in particular towards donor-children. This has gradually, over recent decades, been replaced by identifiable semen donation and a paradigm of openness towards donor-conceived offspring [Citation1–4]. Since the 1980s, several countries including the Netherlands have stated that every child has the right to know his/her genetic origin and prohibited anonymous semen donation by law, which gave children the possibility to learn more about their donor upon reaching adulthood [Citation5]. To date, DST with semen of identifiable donors is increasingly approved as donor-children struggle with not knowing identifiable characteristics of the donor and there is a strong tendency to encourage disclosure in families regardless of the status of the donor [Citation2,Citation6–11].

Disclosure to the child – from birth on – is recommended, since it is known that donor-children who were told about their genetic origins during childhood experience more positive feelings towards their parents than those who were told during adolescence or adulthood [Citation2,Citation9,Citation12–14]. Also, donor-conceived offspring who found out during or after adolescence that they are a donor-child, frequently have feelings of mistrust and wished that parents had told them earlier about being donor-conceived [Citation10].

So far, it is known that children value openness of their parents about their genetic origin but also value peer support by someone in the same situation which reduces feelings of loneliness and stigma-related feelings of being donor-conceived [Citation10,Citation15]. In addition, it has been suggested that counseling might help donor-conceived offspring cope with any negative feelings they may have of being donor-conceived. Counseling in this respect is defined as a method for healthy people to gain a better understanding of their situation, to develop competencies and to address and solve psychosocial problems, building from their own strength and can be offered by social workers and by psychologists [Citation16,Citation17].

As earlier research only studied the experiences of donor-conceived offspring of being donor-conceived, empirical knowledge on their wishes for support is scarce [Citation2,Citation9–10]. The current societal debate on donor-conceived offspring who are searching for their donor shows that donor offspring have a wish for clear information about their origins and discovering later in life about their genetic origins causes psychological harm [Citation18,Citation19]. More knowledge on the wishes of donor-conceived offspring for support can help counselors and psychologist to adjust their support to the needs of donor offspring. Therefore, we aimed at exploring the wishes of Dutch donor-conceived offspring for parental support, peer support and counseling and sought to contribute to the improvement of health care for all parties involved with assisted reproductive technologies.

Methods

Ethical approval

All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration of 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all donor-conceived offspring before their inclusion in the study. The Medical Ethics Committee of the Academic Medical Centre of Amsterdam had requested that donor-conceived offspring should be at least 16 years of age and that the parents of donor-conceived offspring of 16 and 17 years of age gave informed consent as well. The trial is registered at the Dutch Trial Register. Code number NTR5340.

Recruitment

We recruited Dutch donor-conceived offspring aged 16 years or older. In the Netherlands, the Supreme Court acknowledged the right of donor-children to know their genetic origin from the age of 16 and prohibited anonymous semen donation in 2004. Since most Dutch clinics offered open-identity donation next to anonymous donation about ten years before legislation, our sample included both donor-conceived offspring who had access to identifiable information about the donor as well as donor-children who had not.

The recruitment of donor-conceived offspring for this study was part of a broader research project on the wishes for support and counseling of donor-conceived offspring. We recruited donor-conceived offspring for the broader project from September 2015 to February 2016 in three ways. First, the Federatie van Instellingen voor de Ongehuwde Moeder [Federation of Organizations of Unmarried Mothers] (FIOM) posted a message in their newsletter directed to donor-conceived offspring with an announcement asking for participation in this study. FIOM is a foundation for questions about genetic origins and initiator of the KID DNA-Databank [Sperm Donation DNA-Databank] where donor-conceived offspring can be matched with the donor and half siblings. Second, Stichting Donorkind [Foundation Donor-child], a special interest group for donor-conceived offspring and semen donors, posted an announcement on their open and closed Facebook pages with an invitation to participate in this study. Third, we asked participating donor-conceived offspring if they were willing to ask their sibling(s) to participate and we included donor-conceived offspring acquainted to participating offspring and who volunteered to participate at his/her request (snowball sampling).

All donor-conceived offspring who were willing to participate in the broader project contacted one of the researchers, whose email address and telephone number was provided in the announcements. We used a non-probability sampling method, to select a subsample that would represent the total Dutch population of donor-conceived offspring. Every participant was, based on family type and age, compared to the already participating donor-conceived offspring and invited to participate in this interview study. The first author (A.M.S.) sent a patient information letter and an informed consent form to these potential participants and - when they were 16 or 17 years of age – also to their parents. When they agreed to participate after reading our information letter, we contacted them by telephone to arrange the interview. The sample size was increased until theoretical saturation was reached and new data did not yield new insights [Citation20]. All other donor-conceived offspring were included in another ongoing questionnaire study.

Data collection

A junior researcher and counselor (A.M.S.) and a senior researcher and experienced counselor (M.V.) working at the Centre for Reproductive Medicine conducted the in-depth interviews. A.M.S. was trained in the subject of DST by M.V. They interviewed donor-conceived offspring in their home or at the University of Amsterdam, depending on their preference. None of the donor-conceived offspring was acquainted with either of the interviewers before the interview. The participants were informed about the format and confidentiality of the interview. The in-depth interviews started with a questionnaire collecting demographic information, were guided by open ended questions of a self-constructed topic list, based on a literature review and took 45–75 min. During the study the interviewers were aware of their own ideas about donor-conceived offspring and discussed these on regularly basis with two senior researchers (M.H.M.) and (H.M.W.B.) and other members of the research team throughout the data collecting process, to increase trustworthiness [Citation21]. The topic list was adapted when new topics were identified, until data saturation occurred [Citation20]. The interviews were digital audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analyses

The interview transcripts were systematically analyzed by A.M.S. and M.V. and independently by a senior researcher (F.B.v.R.), using the constant comparative method (CCM) [Citation20]. CCM is an iterative process of coding that makes constant comparison of the codes, both within and between interviews, with the aim of conceptualizing the content of the interviews into structured categories [Citation20].

The process of analyzing began after the first three interviews. First, the interviews were analyzed by means of line-by-line coding, comparing the different segments within the interviews. Codes from the following interviews were continually compared with previous codes in order to develop categories. This cycle of comparison and reflection was repeated several times until no new codes were needed to cover the various and relevant themes. The coders discussed the coding into categories and discussed after forming the coding tree, the interviews were read as a whole again to check for any meaningful information [Citation20]. To ensure consistency, any discrepancies between codes, categories and/or comparisons were discussed with other members of the research team, until consensus was met. We performed all analyses with the software program for qualitative data analysis MaxQDA [Citation22]. To generate meaning from the qualitative data and to document and verify this, we made our data countable by using numbers [Citation23]. To display the data we defined the numbers as follows: all donor-conceived offspring (n = 24), almost all donor-conceived offspring (n = 20–23), most donor-conceived offspring (n = 14–19), several donor-conceived offspring (n = 13–8), some donor-conceived offspring (n = 4–7), a few donor-conceived offspring (n = 3–1) and none of the donor-conceived offspring (n = 0). The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist was followed in reporting the findings of this study [Citation24].

Results

Recruitment and inclusion of donor-conceived offspring are summarized in . We obtained 56 positive replies from 541 followers of the newsletter of FIOM and 31 positive replies out of 160 registered open and closed Facebook members of Stichting Donorkind. In addition, snowball sampling led to recruitment of 21 donor-children. Of these 108 donor-conceived offspring who confirmed to participate, we selected 24 donor-conceived offspring for interviews of whom 11 were born in a father–mother family, seven were born in a two-mother family and six were born in a single mother family. Theoretical saturation was achieved after 22 interviews and was confirmed by the last two interviews. Baseline characteristics of the included donor-conceived offspring are shown in .

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the included donor-conceived offspring.

Almost all donor-conceived offspring had been told about donor conception by their parents, one had been told by a neighbor at the age of 9 and one had been told by a niece at the age of 26. Of the donor-children who were told about donor conception by their parents, several knew since early childhood that they were donor-conceived, a few knew since preschool age, a few since puberty and some since adulthood, of which two were told by their mother after the death of their father.

Most donor-conceived offspring with two-mothers and single mothers could not remember the moment of disclosure, as they had been told at a very young age. Almost all donor-conceived offspring with two mothers and single mothers, learned earlier in life about being a donor-child than donor-conceived offspring who were born in a father–mother family.

An exception was a woman with two mothers who had never been told about her donor conception. She sometimes had felt that she was a donor-child, but she had not asked her mothers who her biological father was until she was 29 years of age.

In the analysis of the interviews of the 24 donor-conceived offspring, four themes emerged: disclosure by parents, peer support, independent and trustworthy information and counseling by counselors. These four themes and the frequencies and percentages of the comments are listed in .

Table 2. Four themes and the frequencies and percentages of the comments.

Disclosure by parents

All donor-conceived offspring had tried to talk about donor conception with their parents. They asked their parents why they had chosen for DST and for an anonymous or identifiable semen donor. Most donor-conceived offspring experienced no difficulties talking with their parents, which they had strongly appreciated.

In our family we talk a lot with each other. Now I’m not that kind of person who continually wants to talk about this issue, but my parents were always willing to discuss. That is very helpful. (woman, 21 years of age with lesbian parents)

Several donor-children felt that their parents had not been able to talk openly with them about donor conception, as their parents felt guilty and uncomfortable. Some of these donor-children thought that their fathers felt ashamed about being infertile, as they had experienced embarrassment and anxiety when talking about this with them. They also had believed that their parents wanted to keep donor conception a secret for them, but this secret was often broken after divorce or by death of the father.

For my father it is difficult to talk about this issue [donor conception], so we don’t talk about it so often. I remember a moment when he told me that he was disappointed with himself. I saw him getting smaller and smaller during that conversation. I think he felt ashamed for being infertile as that is the reason why they kept it a secret for so long. (woman, 37 years of age with heterosexual parents)

Several donor-conceived offspring in father-mother families said that their parents had been advised by the doctor to keep donor conception a secret for their child, as disclosure might increase the risk of family issues and attachment problems between the child and the non-biological father. Some of them said that, before disclosure, they always had felt that their parents were hiding something from them, but they had never expected that their parents were hiding such important information. They preferred that their parents had told them earlier in life. Almost all these donor-children mentioned the advice of the doctor and lack of proper guidance on how to talk with children about donor conception as the main reason why their parents had tried to keep donor conception a secret or disclosed after so many years. They wished that their parents would have received good counseling about when and how to share donor conception with children and how to guide their children in being donor-conceived.

I think that it would have been important that the doctors had mentioned that it [DST] is not so special. That you are not weird and that more people became parents after DST. If the doctor had had this attitude, it probably had been more easier for my parents to talk with me about this. (man, 35 years of age with heterosexual parents)

Almost all donor-conceived offspring said that clinics should encourage intended parents to talk openly with their child about being donor-conceived as soon as possible.

I think that they [doctors] have to talk with intended parents about if they want to keep the donor conception a secret for their child. Do they know the consequences of raising a donor-child? They must discuss this before the child is born, because otherwise it is too late and there is nothing they can discuss anymore. (women, 22 years of age with a single mom)

Peer-support

Most donor-children had told family and friends about being a donor-child, as it was important for them that others would understand what this meant. They had preferred to talk openly about being donor-conceived, but said that this was not a topic they had discussed daily with family and friends. Some donor-children said that they only had told their closest friends, as their parents had asked them to keep it a secret for the family.

Almost all donor-conceived offspring who were recruited by FIOM and snowball sampling were familiar with Stichting Donorkind and the possibility to meet other donor-children. Most were interested in stories of others such as since when they had known they were a donor-child, how they had talked about this with their parents and how family and friends had reacted. Several donor-conceived offspring had visited meetings organized by Stichting Donorkind, which they had experienced as an adequate way to exchange feelings with donor-conceived peers.

I registered at the Facebook page of Foundation Donor-child and went to a day where I met other donor-children. It was nice to meet other donor-children with the same questions and issues. This day resulted into a good friendship with another man. It is nice to have a friend with whom I can have an open conversation about being a donor-child. (man, 35 years of age with heterosexual parents)

While all donor-conceived offspring had appreciated the exchange of stories by the Facebook page of Stichting Donorkind, several of them did not had a wish to actually seek contact with this Foundation. Some of them had felt that this Facebook page included too many stories of children who struggle with being a donor-child and they did not have a need to discuss donor conception with others than family and friends.

I know about the existence of Foundation Donor-child and the meetings they organize. But is that not only for the ones who struggle with being donor conceived? I think it is good that they offer this platform for anyone who wishes to meet other donor-children or has specific questions about being donor conceived. I don’t have a need to go there. I can go to my mother or friends if I want to talk about this. (man, 41 years of age with heterosexual parents)

Independent and trustworthy information

Most donor-conceived offspring were curious about the personality and genetic characteristics of the donor, especially once reaching puberty. They had wondered whether they had the same appearance as the donor and had hoped to receive information about his motivation to donate semen. Most donor-conceived offspring had expressed the wish to meet the donor one day and/or were actively seeking contact with him by registering at FIOM’s KID DNA-Databank. Not all interviewed donor-children were registered at the KID DNA-Databank. Some of them said that the databank was not accessible for them, as registration costs were too high [€250].

Besides the wish for information about the donor, some donor-children had wished to receive information about the clinic where their parents had been treated, what had happened with their files and if there were other possibilities than the KID DNA-Databank to find their donor and half-siblings. Most of them had sought contact with the clinic their parents had been treated, but were told that the clinic could not provide them with information about the donor. They had wished to receive support of someone who could help on how to find information to get in contact with the donor and half-siblings.

I am looking for a place where people can guide me with finding all these pieces about the donor and the clinic. Maybe there are people who know more, but how do I get in contact with them? My guide, so far, is Google, but there is not enough specific information on the internet. (women, 25 years of age with heterosexual parents)

Counseling

In some donor-conceived offspring, not knowing who the donor is led to questions about their identity and to symptoms of depression. Some donor-children had one or more conversations with a psychologist or a social worker about identity related problems or difficulties in the relation with their parent(s). Some felt that these problems were not related to being a donor-child, while others said that these problems occurred after they had been told about their genetic origins.

Me, my brother and my sister had issues with being a donor-child. I even went to a psychologist for suffering from depression. That was not only because we are donor conceived, but it has definitely something to do with that. For me being donor conceived felt as grief and my psychologist guided me dealing with that. (woman, 32 years of age with lesbian parents)

A few donor-conceived adults said they had a consultation with a therapist in the school-age period because of study related problems, which they felt had nothing to do with being a donor-child.

Some donor-children who had contact with a psychologist or a social worker, were satisfied with the counseling they had received, as these counselors had helped them to cope with their identity questions and, in some cases, behavioral problems. Others mentioned that, as they had felt that their problems were related to not knowing who their biological father is, their problems had not been solved by counseling of a general psychologist.

A few donor-conceived offspring preferred counseling of a counselor specialized in donor conception and donor-conceived families, but they did not know where they could find such a counselor.

Expertise of the professional is important in guidance. I can go to an all-round psychologist but that is not specific enough. I went to an all-round psychologist in the past, and she could help me with a lot of other stuff, but when it came to things like my donor-dad, she was not experienced, so I prefer to go to a specialist. (woman, 39 years of age with heterosexual parents)

Some thought that counseling was needed for their donor-conceived siblings, as they had felt that they struggled more with being a donor-child than they did. Almost all donor-conceived offspring said that counseling should be accessible for all donor-conceived offspring when they had needed this.

Discussion

In exploring the wishes of donor-conceived offspring with regards to parental support, peer support and counseling, we found that the donor-children who know about the DST wished open conversations about donor conception and being a donor-child. They talked more easily with their parents about their feelings and thoughts on being donor-conceived when they had open conversations with their parents from birth on. Children who did not experience openness from their parents wished that their parents would have received counseling by specialist counselors before starting DST to prepare them to talk openly about donor conception. Not all donor-children wished peer contact. Most donor-children who sought contact with peers appreciated contact with them to exchange experiences and to find a sense of recognition. Others did not seek contact with peers, as they were content to talk with their family and friends about being a donor-child. Donor-conceived offspring wished to know where to find specialist counseling when needed. Furthermore, in retrospect, they all wished that they had received trustworthy information of someone who would have told them how to find information about the donor, about the clinic their parents had been treated and how to search for their donor and half-siblings.

Our finding that children appreciated open communication with their parents, is in line with other qualitative and quantitative studies that found that talking with a child about being a donor-child is a process which must be repeated during child development [Citation8,Citation25–27]. Several donor-conceived offspring in our study experienced that their parents were uncertain how to talk to them about being a donor-child. They emphasized the importance of counseling before DST to prepare parents for sharing donor conception at several moments during child-raising. This mirrors earlier studies that revealed that also parents have a wish for counseling before and after childbirth, especially on when and how to disclose donor conception to their child [Citation28–30]. Parents experience a lack of clear scripts about how and what to tell to their children and they have a need for information about experiences of other parents on this [Citation31]. The Donor Conception Network in the UK provides parents and intended parents with information on how to frame the story of donor insemination from birth on, these findings are now underpinned by our findings on the donor-conceived offspring [Citation31]. What is really needed to satisfy the wishes children is that counseling intended parents focuses on teaching them to talk openly with their children about donor conception during child-raising and provide them with clear scripts and information about the experiences of parents, as demonstrated in our study.

A recent opinion paper on disclosure and well-being of donor-children stated that disclosure, and directive counseling towards disclosure, cannot be justified because there is no empirical evidence of differences in psychological well-being of donor offspring in disclosing and non-disclosing families [Citation32]. It was recommended that if parents decide not to disclose donor conception, they should be supported by counselors how to keep donor conception a secret [Citation32]. Our study provides evidence on this issue, although – for obvious reasons – donor children of non-disclosing families cannot be studied. The evidence points out that parents should talk openly about donor conception with their child and that specialist counselors should prepare intended parents how to do this. The fact that some studies found that in disclosing families children were negatively influenced by the stress of their parents, only underpins the importance of greater psychological support for parents throughout the process of talking about donor conception with their child and give them support in being a donor-child [Citation13,Citation30,Citation33].

The strength of this study is that we interviewed a diverse group of donor-conceived offspring, i.e. adolescent and adult donor-conceived offspring from all family types i.e. children of father–mother families, two-mother families and single mother families, enhancing the generalizability. Donor-conceived offspring from all family types reported almost similar experiences on peer-contact, wish for independent and trustworthy information and counseling. This means that findings of earlier research that suggested that two-women couples need less information about how and when to talk with their children about donor conception, is not underpinned by the children themselves [Citation34,Citation35]. The only differences we found is that donor-conceived offspring in father–mother families learned later in life about their genetic origins than children in two-mother families and single mother families.

A limitation of this study is that almost all donor-conceived offspring were registered at the KID-DNA Databank or were recruited through networks organizations. This may lead to selection bias, because these children wished to receive information and get into contact with their peers and/or their donor. On the other hand, donor-conceived offspring who had peer contact are the only ones who can indicate their wishes for peer contact.

In view of our data, we recommend easy access to counseling for all donor-conceived offspring who know about their genetic origin. We also recommend that counseling should be available for all intended parents and specifically for parents who decide to disclose to their child to help them to talk about donor conception more easily with their future child and with family and friends. These data may contribute to increased awareness of health care professionals in the field of unconventional parenthood and lead to improvement of health care for all parties involved. Furthermore, guidelines for psychosocial counseling should be developed with taking into account the experiences and wishes of donor-children who know about their genetic origins.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Brewaeys A, de Bruyn JK, Louwe LA, et al. Anonymous or identity-registered sperm donors? A study of Dutch recipients’ choices. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:820–824.

- Scheib JE, Riordan M, Rubin S. Adolescents with open-identity sperm donors: reports from 12-17 year olds. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:239–252.

- Daniels K. Donor gametes: anonymous or identified?. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gyn. 2007;21:113–128.

- Readings J, Blake L, Casey P, et al. Secrecy, disclosure and everything in-between: decisions of parents of children conceived by donor insemination, egg donation and surrogacy. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;22:485–495.

- Janssens PMW, Simons AHM, van Kooij RJ, et al. A new Dutch Law regulating provision of identifying information of donors to offspring: background, content and impact. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:852–856.

- ESHRE Task Force on Ethics and Law; III. Gamete and embryo donation. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:1407–1408.

- Ethics Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Informing offspring of their conception by gamete or embryo donation: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:45–49.

- Human Fertility and Embryology Authority (HFEA). Code of Practice Edition 8.0. London: HFEA; 2013.

- Jadva V, Freeman T, Kramer W, et al. The experiences of adolescents and adults conceived by sperm donation: comparisons by age of disclosure and family type. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:1909–1919.

- Turner AJ, Coyle A. What does it mean to be a donor offspring? The identity experience of adults conceived by donor insemination and the implications for counselling and therapy. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:2041–2051.

- Mahlstedt PP, LaBounty K, Kennedy WT. The views of adult offspring of sperm donation: essential feedback for the development of ethical guidelines within the practice of assisted reproductive technology in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:2236–2246.

- Freeman T, Golombok S. Donor insemination: a follow-up study of disclosure decisions, family relationships and child adjustment at adolescence. Reprod Biomed Online. 2012;25:193–203.

- Tallandini MA, Zanchettin L, Gronchi G, et al. Parental disclosure of assisted reproductive technology (ART) conception to their children: a systematic and meta analytic review. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:1275–1287.

- Paul MS, Berger R. Topic avoidance and family functioning in families conceived with donor insemination. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:2566–2571.

- Crawshaw M, Gunter C, Tidy C, et al. Working with previously anonymous gamete donors and donor-conceived adults: recent practice experiences of running the DNA based voluntary information exchange and contact register, UK DonorLink. Hum Fertil (Camb). 2013;16:26–30.

- Boogaars J, Hardeveld van E, Woertman F. Counselling een nieuw perspectief van ont-moeten, ont-dekken, ont-wikkelen [Counseling a new perspective on all-ways, dis-cover, development]. Garant: Antwerpen; 2007.

- Veen van G. Handboek counseling [Counseling handbook]. Van Gorcum: Assen; 2010.

- Allan S. Donor conception and the search for information: from secrecy and anonymity to openness. Abingdon: Routledge; 2017.

- Ilioi E, Blake L, Jadva V, et al. The role of age of disclosure of biological origins in the psychological wellbeing of adolescents conceived by reproductive donation: a longitudinal study from age 1 to age 14. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2017;58:315–324.

- Boeije HA. A purposeful approach of the constant comparative method in analysis of qualitative interviews. Qual Quant. 2002;30:391–409.

- Giorgi A. Concerning the application of phenomenology to caring research. Scand J Caring Sci. 2000;14:11–15.

- MAXQDA. Software for qualitative data analysis. Berlin: VERBI Software – Consult Sozialforschung GmbH; 2011.

- Sandelowski M. Real qualitative researchers do not count: The use of numbers in qualitative research. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24:230–240.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–357.

- Beeson DR, Jennings PK, Kramer W. Offspring searching for their sperm donors: how family type shapes the process. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:2415–2424.

- Akker vd O. A review of family donor constructs: current research and future directions. Hum Reprod. 2006;12:91–101.

- Hertz R, Nelson MK, Kramer W. Donor conceived offspring conceive of the donor: the relevance of age, awareness, and family form. Soc Sci Med. 2013;86:52–65.

- Lalos A, Gottlieb C, Lalos O. Legislated right for donor-insemination children to know their genetic origin: a study of parental thinking. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:1759–1768.

- Söderström-Anttila V, Sälevaara M, Suikkari AM. Increasing openness in oocyte donation families regarding disclosure over 15 years. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:2535–2542.

- Visser M, Gerrits T, Kop F, et al. Exploring parents’ feelings about counselling in donor sperm treatment. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;37:156–163.

- Hargreaves K, Daniels K. Parents dilemmas in sharing donor insemination conception stories with their children. Child Soc. 2007;21:420–431.

- Pennings G. Disclosure of donor conception, age of disclosure and the well-being of donor offspring. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:969–973.

- Golombok S, Blake L, Casey P, et al. Children born through reproductive donation: a longitudinal study of psychological adjustment. J Child Psychol Psych. 2013;54:653–660.

- Indekeu A, Rober P, Schotsmans P, et al. How couples’ experience prior to the start of infertility treatment with donor gametes influences the disclosure decision. Gynaecol Obstet Invest. 2013;76:125–132.

- Wyverkens E, Provoost V, Ravelingien A, et al. Beyond sperm cells: a qualitative study on constructed meanings of the sperm donor in lesbian families. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:1248–1254.