Abstract

Background

Restrictions around childbirth, introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, could decrease maternal feelings of control during birth. The aim of this study was to compare the sense of control of women who gave birth during the COVID-19 pandemic with women who gave birth before COVID-19. The secondary objective was to identify other factors independently associated with women’s sense of control during birth.

Methods

A prospective cohort study, in a sub-cohort of 504 women from a larger cohort (Continuous Care Trial (CCT), n = 992), was conducted. Sense of control was measured by the Labor Agentry Scale (LAS). Perinatal factors independently associated with women’s sense of control during birth were identified using multiple linear regression.

Results

Giving birth during the COVID-19 pandemic did not influence women’s sense of control during birth. Factors statistically significantly related to women’s sense of control were Dutch ethnic background (β 4.787, 95%-CI 1.319 to 8.254), antenatal worry (β − 4.049, 95%-CI −7.516 to −.581), antenatal anxiety (β − 4.677, 95%-CI −7.751 to 1.603) and analgesics during birth (β − 3.672, 95%-CI −6.269 to −1.075).

Conclusions

Despite the introduction of restrictions, birth during the COVID-19 pandemic was not associated with a decrease of women’s sense of control.

Introduction

Humans value a sense of control when impactful events, such as childbirth, happen in their life. A diminished sense of control is associated with negative effects on health and psychological wellbeing [Citation1]. Especially for labor and birth, a sense of control is important to women, since it is a significant predictor of childbirth satisfaction, which has immediate and long-term effects on the health and well-being of mother and child [Citation2–5]. In modern society, birth mostly takes place in a clinical environment, which could decrease women’s sense of control [Citation6].

Women, who gave birth in the period from March 11, 2020 onwards, might have experienced a greater loss of control. On March 11, 2020 the World Health Organization declared the distribution of the COVID-19 virus to be a pandemic. Thereafter, institutional settings worldwide introduced special restrictions in maternity care. This was also the case in the south of the Netherlands, both in primary as well as secondary maternity care. The presence of a birth companion in labor was limited to one person, with no possibility to switch companions during labor. If the birth companion was positive for COVID-19, they were not allowed to be present. Face-to-face interaction with healthcare providers was limited by protective equipment [Citation7]. After discharge, the new mother and her household had to follow strict rules, including social distancing and not allowing visitors [Citation8].

These restrictions may have affected women’s birth plans, by prohibiting the execution of certain items in this plan. A birth plan allows women to be involved in the decision-making process and leads to the feeling of having more control over the childbirth [Citation9]. Therefore, the implementation of restrictions during COVID-19, may have affected the maternal sense of control during birth.

Studies into this topic in other countries than the Netherlands have generally focused on the feeling of anxiety during pregnancy. These studies have shown that pregnant women have elevated levels of anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic [Citation10–12]. Studies such as these suggest that feelings of anxiety persist during birth itself and result in psychological vulnerability of the women giving birth [Citation13]. However, little is known about whether giving birth during the pandemic indeed influences women’s feelings during childbirth. Focusing on the feeling of control during birth in this pandemic may lead to new insights that could improve maternity care during COVID-19 or during similar situations in the future. Additionally, few studies have focused on identifying those factors that influence the feeling of control during childbirth. Therefore, this study should result into insights that could improve obstetric care in general.

In this prospective multicenter cohort study, the primary objective was to compare sense of control during childbirth of women who gave birth during the COVID-19 pandemic (from March 11, 2020 to December, 2020) with women who gave birth before March 11, 2020. The secondary objective was to identify other factors independently associated with women’s sense of control during birth. The hypothesis was that giving birth during the COVID-19 pandemic results in a lower sense of control in women during childbirth.

Materials and methods

A cross-sectional analysis was conducted among a sub-group of women from the Continuous Care Trial, a two-armed, multicenter randomized controlled trial in the south of the Netherlands. This trial has been described in detail in a study protocol [Citation14]. Briefly, it compared the effects of continuous care by a trained maternity care assistant during birth, with care-as-usual. Continuous care was defined as care that is given during the full first stage of labor by a trained maternity care assistant, who can offer emotional, physical and practical support. Recruitment was carried out by intake-staff of the maternity care assistant agencies. After women registered for postnatal care at one of these agencies, they were informed about the study via telephone or e-mail. At the standard home visit around 34 weeks of gestation, intake-staff answered remaining questions and informed consent was signed. Primiparous as well as multiparous women, who were pregnant more than 27 weeks, lived in Limburg, the south-eastern region of The Netherlands, and planned to have a vaginal birth, were eligible for the study. Women who were younger than 18 years of age, had a cesarean delivery planned or were unable to speak, read or write in the Dutch language, were excluded from the cohort. Additionally, for this study, women who did not complete the Labor Agentry Scale (LAS) questionnaire were excluded.

The patient data was collected between 2018 and 2020 using questionnaires. The first questionnaire collected baseline demographic and obstetric characteristics and was completed by the women directly after inclusion, during the standard home visit. In the first week after birth, preferably the day of the birth, a case report form based on the birth itself was completed. Additionally, the women filled out a second questionnaire to score sense of personal control during childbirth.

The Continuous Care Trial has been approved by the medical ethical committee of Maastricht University Medical Center (METC172041) and all participants gave informed consent. Since this research used data from the Continuous Care Trial, new medical ethical approval was not needed.

To measure women’s sense of control during birth, a validated instrument was used: the LAS. This instrument has demonstrated an internal reliability coefficient of 0.97 and construct validity has been shown through factor analyses and dual scaling [Citation3]. The original LAS consists of 29 positively and negatively worded statements. The short version, as used in this research and presented in Appendix I, consists of 11 statements. These positively and negatively worded statements are scored on a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from “always or almost always” to “rarely or never.” A total score was obtained by reversing the scores of the positive worded items, so that a positive response reflected a higher score and corresponded with the negative worded items. In this manner, all scores were summed to form a total score, in which 11 stood for never or rarely feeling in control and 77 for always or almost always feeling in control.

To estimate the association between the independent variables and the sense of control during birth, a multiple linear regression analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 25 software. The variables were selected based on literature and clinical perspectives, and included maternal baseline characteristics, factors related to the maternal antenatal psychological well-being, and factors related to birth and maternity care.

Maternal baseline characteristics included age, highest finished education (dichotomized as low for women who finished elementary school, high school or vocational education and high for women who finished university of applied sciences or research university), ethnic background (Dutch or non-Dutch), parity including obstetric history (categorical variable: primipara, multipara with vaginal birth in obstetric history or multipara with only cesarean section in obstetric history) and randomization for continuous care (randomized for continuous care during labor or randomized for care-as-usual).

The factors related to women’s antenatal psychological well-being were antenatal anxiety and antenatal worry. Antenatal anxiety levels were measured using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), completed at time of inclusion. The STAI is a validated and widely used instrument that measures two types of anxiety: state and trait. It consists out of 20 positively and negatively worded items, with a four-point Likert Scale (1 “not at all” to 4 “very much so”). The total score can range from 20 to 80, in which a higher score represents a higher state of anxiety [Citation15,Citation16]. A threshold of 39 points was used as a cutoff value to identify antenatal anxiety, as has been suggested to detect anxiety that is clinically significant [Citation17].

Antenatal worry levels were measured using the Cambridge Worry Scale (CWS), also completed at time of inclusion. The CWS is a validated instrument that measures the extent and content of women’s concerns during pregnancy on four factors: socio-medical, own health, socio-economic, and relational. It consists of 16 questions, using a six-point Likert scale (0 “not a worry” to 5 “major worry”). The total score can therefore range from 0 to 80, in which the higher CWS scores represent a higher worry [Citation18]. No clinical cutoff value has been described for the CWS. Therefore, 10% of the participants with the highest CWS scores has been used to identify a cutoff value for this research. This resulted in a cutoff value of 17 points to identify antenatal worry.

Factors related to the birth and maternity care included type of care during birth (categorical variable: midwife-led primary care, obstetric-led secondary care or transfer from midwife-led to obstetric-led care during birth), mode of onset of birth (spontaneous contractions and rupture of membranes or induction of birth), mode of delivery (vaginal birth or unplanned cesarean section), use of analgesics during birth (yes or no), length of hospitalization after birth for mother and/or child (categorical variable: no or less than 24 h, between 24 and 48 h, more than 48 h), and complications during birth (yes or no).

Complications were defined as a binary outcome in accordance with the Continuous Care Trial [Citation14]. Occurrence of a complication during birth was defined as the presence of one of the following situations: admission of the baby to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for more than 24 h, uterine rupture, birth injury (shoulder dystocia, clavicle or arm fracture), asphyxia (APGAR score <7 after 5 min), third- or fourth-degree tear, and blood loss of more than 1000 milliliters.

Maternal baseline characteristics, factors related to antenatal psychological well-being and factors related to the birth and maternity care were retrieved from the questionnaires. In case of missing information medical records, discharge letters or the corresponding healthcare professionals were consulted. The percentage of patients with incomplete data was low (2.8%). Since literature suggests imputation from a missingness of 5% [Citation19], the missing data were not imputed.

Results

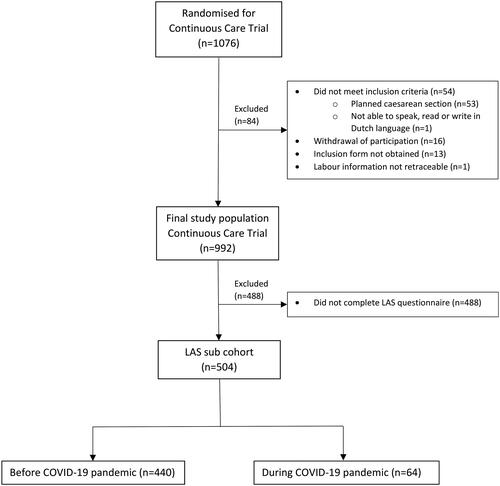

shows the inclusion flowchart. A total of 1076 women were randomized for the Continuous Care Trial, 84 of whom were excluded due to not meeting the inclusion criteria, withdrawal of participation, not being able to obtain the inclusion form or no possibility to retrace birth information. This has led to a study population of 992 women for the Continuous Care Trial. 488 of these women could not be included due to incomplete LAS questionnaires, leaving a sub-cohort of 504 women, of whom 440 gave birth before the COVID-19 pandemic and 64 women during the pandemic.

shows the characteristics of the participants in this study, displaying the maternal baseline differences in the group giving birth before the COVID-19 pandemic, compared to the group giving birth during the pandemic. Age, ethnic background and continuous care were similar among both groups, while there were differences for education (73.0% in COVID-19 group versus 60.6% in comparison group) and parity (54.0% in COVID-19 group versus 63.2% in comparison group).

Table 1. Characteristics of all participants and maternal baseline characteristics of women giving birth before COVID-19 pandemic and during COVID-19 pandemic.

shows descriptive statistics for the factors included in the regression model for the total study group, as well as LAS scores of women with different values of these factors. Overall, LAS scores were high, with a mean LAS score of 61.61 for all participants (SD 11.631).

Table 2. Distribution of the characteristics included in multiple regression analysis.

The multivariable linear regression showed that giving birth during the COVID-19 pandemic is not significantly associated with women’s sense of control (, model 1). This did not change after correcting for baseline characteristics (, model 2).

Table 3. Multiple linear regression.

To assess the independent association of factors other than COVID-19 period with sense of control, antenatal psychological well-being-related factors and birth and maternity care-related factors were also added to the multivariable linear regression. The results are shown in , model 3. Dutch ethnic background, as opposed to non-Dutch background, was positively associated with LAS (β 4.787, 95%-CI 1.319 to 8.254). Having antenatal worry and antenatal anxiety were both negatively associated (β 4.049, 95%-CI −7.516 to −.581 and β 4.677, 95%-CI −7.751 to −1.608, respectively). The use of analgesics during birth was also negatively associated with LAS score (β − 3.672, 95%-CI −6.269 to −1.075).

Sub-analyses for women with midwife-led care during birth and women with obstetric-led care during birth, including women who were transferred from midwife-led to obstetric-led care, were performed. These sub-analyses did not show any meaningfully different associations between delivery during COVID-19 restrictions and LAS.

Discussion

This study explored the difference in sense of control during childbirth between women who gave birth during the COVID-19 pandemic and women who gave birth before the pandemic. This study also explored which other factors were independently associated with women’s sense of control during birth. In general, women participating in this study reported high levels of sense of control during childbirth. Giving birth during the COVID-19 pandemic did not lower this high sense of control.

An explanation for the sense of control remaining high may be the increased number of home births during the pandemic [Citation20,Citation21]. Due to the current limited proportion of home births in the Netherlands (14.4% of all primipara and 35.4% of all multipara [Citation22]), the place of birth was not included in our study. However, giving birth at home instead of in a clinical environment may increase women’s sense of control [Citation6]. For women who did not have a home birth, the high sense of control indicates that the expectation management of women giving birth during COVID-19 seems sufficient. This suggests that, despite the pandemic, the healthcare system was capable of preserving women’s sense of control and the autonomy of women during their childbirth.

This study found other factors that were independently associated with women’s sense of control during birth. Having a Dutch ethnic background was positively associated with sense of control during birth. Having antenatal worry, antenatal anxiety and receiving analgesics during birth had an independent negative association with women’s sense of control during birth.

A lower sense of control in non-Dutch women may be explained by the fact that non-Dutch women are known to experience problems with the use of healthcare due to language issues, their different cultural background and unfamiliarity with the Dutch maternity care system [Citation23]. Besides, Peters et al. showed that women with a non-Western ethnic background and low education have an overall negative opinion about the Dutch healthcare responsiveness during all stages of antenatal, birth, and maternity care [Citation24].

Antenatal worry and anxiety being negatively correlated with women’s sense of control during birth, is in accordance with the findings of Lemmens et al., who found that antenatal anxiety is highly correlated to pregnancy and childbirth dissatisfaction [Citation25]. Since other studies indicate that sense of control during birth is a significant predictor of childbirth satisfaction [Citation2], it is plausible that antenatal worry and anxiety, childbirth dissatisfaction and sense of control during birth are all associated with each other.

Women who received analgesics during childbirth also reported a significantly lower sense of control during birth. However, it remains unclear which of the two is cause and which is effect. Other studies about pain during birth reported that high levels of pain are related to a negative sense of control [Citation4,Citation26] and that the most satisfied women are those who use no analgesics during birth [Citation5]. However, a review by Hodnett et al. showed that it is not the pain, nor the pain medication itself that influences the subsequent satisfaction, but it is a combination of personal expectations, the support from caregivers, the quality of the caregiver-patient relationship, and involvement in decision-making [Citation27].

Although the study showed multiple factors being independently associated with an influence on women’s sense of control during birth, these factors separately did not exceed the threshold for clinical relevance as defined by studies concerning the minimal important difference in quality of life instruments. These studies report that a minimal clinically important difference is half a point on a 7 point scale. Since the LAS consists out of 11 items, a difference of a minimum of 5.5 points in total, is considered as clinically relevant [Citation28–30]. Although the factors separately did not reach the threshold of 5.5 points, it is possible that the combination of these factors will have a strong and clinically relevant effect.

The main strength of this study is its usage of participants from an ongoing trail, which made it possible to compare sense of control of women giving birth during the COVID-19 pandemic with women giving birth before COVID-19 played a role in everyday life. Therefore, the pandemic could not have had influence on the feelings of these women. Another strength of the study is that the LAS was filled out directly after birth until one week postpartum. This short timeframe minimizes recall bias. Besides, it is the first study to assess sense of control in women giving birth during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A limitation of this study is that this cohort may potentially have participation bias, since participants were included from a larger cohort [Citation31]. However, no baseline differences between the sub-cohort and non-responder cohort were found. Due to the Dutch setting of the study, the generalizability to other settings may be limited. The Dutch maternity care system differs from other international systems because of independently practicing midwives, who conduct home births. In a clinical setting however, it is likely that the restrictive measures are comparable between the Dutch maternity care system and the system in other countries.

Conclusion

In this study, giving birth during the COVID-19 pandemic did not impact women’s sense of control during childbirth. Having a non-Dutch ethnic background, experiencing antenatal worry and anxiety and receiving analgesics during birth were independently negatively associated with sense of control. The results indicate that despite the COVID-19 pandemic, the healthcare system could preserve women’s sense of control and therefore the autonomy of women during their childbirth.

Ethics approval

The current study was part of the Continuous Care Trial, which received ethical approval from the medical ethical committee of Maastricht University Medical Center (METC172041). All participants gave informed consent.

Author contributions

KC wrote the majority of the manuscript. HS and MN designed the Continuous Care Trial and provided major feedback on writing. LS advised and edited the text concerning statistical analysis. KC, AS, AL, BP, SJ and MLV are responsible for the practical organization of the Continuous Care Trial. AL, JL and RVL are responsible for organization of the trial in participating centers. AS, AL, JL, RVL, BP, SJ and MLV provided feedback on writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (14 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

There is no online database. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ward MM. Sense of control and self-reported health in a population-based sample of older Americans: assessment of potential confounding by affect, personality, and social support. Int J Behav Med. 2013;20(1):140–147.

- Goodman P, Mackey MC, Tavakoli AS. Factors related to childbirth satisfaction. J Adv Nurs. 2004;46(2):212–219.

- Hodnett ED, Simmons-Tropea DA. The labour agentry scale: psychometric properties of an instrument measuring control during childbirth. Res Nurs Health. 1987;10(5):301–310.

- Green JM, Baston HA. Feeling in control during labor: concepts, correlates, and consequences. Birth. 2003;30(4):235–247.

- Green JM, Coupland VA, Kitzinger JV. Expectations, experiences, and psychological outcomes of childbirth: a prospective study of 825 women. Birth. 1990;17(1):15–24.

- Bohren MA, Hofmeyr GJ, Sakala C, et al. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7(7):CD003766.

- Boelig RC, Manuck T, Oliver EA, et al. Labor and delivery guidance for COVID-19. Am J Obstet Gynecol Mfm. 2020;2(2):100110.

- Cowling BJ, Aiello AE. Public health measures to slow community spread of coronavirus disease 2019. J Infect Dis. 2020;221(11):1749–1751.

- Kuo S-C, Lin K-C, Hsu C-H, et al. Evaluation of the effects of a birth plan on Taiwanese women's childbirth experiences, control and expectations fulfilment: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(7):806–814.

- Lebel C, MacKinnon A, Bagshawe M, et al. Elevated depression and anxiety symptoms among pregnant individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:5–13.

- Moyer CA, Compton SD, Kaselitz E, et al. Pregnancy-related anxiety during COVID-19: a nationwide survey of 2740 pregnant women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2020;23(6):757–765.

- Preis H, Mahaffey B, Heiselman C, et al. Pandemic-related pregnancy stress and anxiety among women pregnant during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Am J Obstet Gynecol Mfm. 2020;2(3):100155.

- Viaux S, Maurice P, Cohen D, et al. Giving birth under lockdown during the COVID-19 epidemic. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2020;49(6):101785.

- Lettink A, Chaibekava K, Smits L, et al. CCT: continuous care trial – a randomized controlled trial of the provision of continuous care during labor by maternity care assistants in The Netherlands. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):725.

- Spielberger CD. State-trait anxiety inventory: Bibliography. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1989.

- van der Ploeg HD, Spielberger CD. Handleiding bij de Zelf-Beoordelings Vragenlijst ZBV: een nederlandstalige beweking van de Spielberger State-Trait Anxiet Inventory STAI-DY. Tijdschrift voor psychiatrie. 1980.

- Julian LJ. Measures of anxiety: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A). Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63 Suppl 11(0 11):S467–S72.

- Green JM, Kafetsios K, Statham HE, et al. Factor structure, validity and reliability of the Cambridge worry scale in a pregnant population. J Health Psychol. 2003;8(6):753–764.

- Frank E, Harrell J. Regression modeling strategies. 2 ed. Vol. XXV. Cham: Switzerland Springer; 2015. p.582.

- Grünebaum A, McCullough LB, Bornstein E, et al. Professionally responsible counseling about birth location during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Perinat Med. 2020;48(5):450–452.

- Hart VN. corona laat vrouwen vaker thuis bevallen, gemist?: Koninklijke Nederlandse Organisatie van Verloskundigen; 2020. [updated 15-09-2020. Available from: https://www.knov.nl/actueel-overzicht/nieuws-overzicht/detail/bevallen-ten-tijde-van-corona/2763.

- Perinatale zorg in Nederland anno 2018. [press release]. Perined, 26-11-2019 2019.

- Lescure D, Schepman S, Batenburg R, et al. Preferences for birth center care in The Netherlands: an exploration of ethnic differences. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):79.

- Peters IA, Posthumus AG, Steegers EAP, et al. Satisfaction with obstetric care in a population of low-educated native Dutch and non-Western minority women. Focus group research. PLOS One. 2019;14(1):e0210506.

- Lemmens SMP, van Montfort P, Meertens LJE, et al. Perinatal factors related to pregnancy and childbirth satisfaction: a prospective cohort study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2021;42(3):181–189.

- Nieuwenhuijze MJ, de Jonge A, Korstjens I, et al. Influence on birthing positions affects women's sense of control in second stage of labour. Midwifery. 2013;29(11):e107–e114.

- Hodnett ED. Pain and women's satisfaction with the experience of childbirth: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(5 Suppl):S160–S72.

- Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Willan A, et al. Determining a minimal important change in a disease-specific quality of life questionnaire. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(1):81–87.

- Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. Measurement of health status. Ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trials. 1989;10(4):407–415.

- Geerts CC, Klomp T, Lagro-Janssen ALM, et al. Birth setting, transfer and maternal sense of control: results from the DELIVER study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):27.

- Berman DM, Tan LLJ, Cheng TL. Surveys and response rates. Pediatr Rev. 2015;36(8):364–366.