Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to analyze the efficacy of psychosocial interventions for improving pregnancy rates in infertile women undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment through a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

Twelve studies were included in the meta-analysis. To estimate the effect size, a meta-analysis of the studies was performed using RevMan 5.3. The possibility of publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots and Egger’s method.

Results

A statistically significant effect size (standardized mean difference [SMD] = 1.39; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.11–1.71; p = 0.004; I2 = 19%) was found for the 12 studies that investigated the effects of psychosocial interventions on clinical pregnancy rates. The psychosocial interventions that had a significant effect on pregnancy rates were mind-body interventions (SMD = 1.37; 95% CI = 1.01–1.85; p = 0.040; I2 = 0%) and cognitive behavioral therapy (SMD = 2.19; 95% CI = 1.17–4.13; p = 0.010).

Conclusions

The results suggest that psychosocial interventions affect pregnancy rates. Moreover, they indicate that mind-body interventions and cognitive behavioral therapy are beneficial for improving the pregnancy outcome in infertile women undergoing IVF.

Introduction

Although there has been an unprecedented low fertility phenomenon worldwide, Korea’s total fertility rate in 2019 was 0.92 people, which is far below the average of 1.68 in 35 member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) [Citation1]. The total fertility rate is the average number of births that a woman is expected to have in her lifetime. The total fertility rate required to maintain a population is usually 2.1 people, so it is predicted that before 2028, the total population in Korea will begin to decline [Citation2]. The number of infertility diagnoses in Korea increased from 178,000 in 2007 to 221,000 in 2016 [Citation3]. In addition, medical expenses due to infertility were a major socio-economic problem in 2018, reaching 115.03 billion won. Accordingly, the government started the “Medical Expense Support Project for Infertile Couples” for low-income families in 2006. Thereafter, the target of support was increased by gradually expanding the targeted income bracket and age range. Since October 2017, infertility treatment has been included in the National Health Insurance to incorporate an expanded version of the scope of infertility treatment to increase the fertility rate. Efforts are being made to increase the fertility rate by expanding these support programs to include more than financial benefits [Citation4]. Despite these efforts, the proportion of births due to infertility interventions among all births was only 8.8% in 2019 [Citation5]. Furthermore, the likelihood of pregnancy per procedure for infertile couples receiving medical support was 33.5% in 2013, 31.5% in 2015, and 28.1% in 2017 [Citation6]; therefore, measures to increase the pregnancy rate among infertile women are needed.

One infertility procedure, in vitro fertilization (IVF), is performed in several stages including controlled ovarian hyperstimulation, oocyte retrieval, embryo culture, and intrauterine embryo transfer [Citation7]. During these procedures, women experience physical and psychological burdens [Citation8]. While waiting for pregnancy results after embryo transfer, infertile women’s anxiety and depression can rise sharply [Citation9], and they often worry that their daily activities may be a factor in pregnancy failure [Citation10]. In such a period, the emotions of infertile women are expressed as “the period of experiencing the irritation of drying out blood” [Citation11].

The stress, anxiety, and depression experienced by infertile women are comparable to that experienced by patients with renal failure [Citation12] or cancer [Citation13], and these emotions have been found to have a significant effect on the pregnancy rate after IVF [Citation14]. A prospective cohort study of 475 infertile couples who underwent primary IVF measured stress levels using salivary alpha-amylase enzymes and confirmed pregnancy outcomes, and found that high levels of alpha-amylase (i.e. high stress) correlated with an increased risk of pregnancy failure after IVF [Citation15]. In addition, in a study of 23,557 infertile women undergoing IVF, infertile women (n = 51) who did not take antidepressants despite depression and anxiety before IVF had a pregnancy rate of 21.6% and a childbirth rate of 9.8%. Also, the pregnancy and fertility rates of infertile women who were diagnosed with depression and anxiety and received antidepressant medication (n = 829) were 38.3% and 25.9%, respectively, and were not diagnosed with depression (n = 22,513) were 39.8% and 28.5%, respectively [Citation16]. Those with depression and anxiety, but without proper treatment, had the lowest pregnancy and fertility rates.

In a meta-analysis of 39 psychosocial intervention studies conducted on infertile women or couples, the pregnancy rate increased as anxiety decreased before or during the infertility procedure, suggesting that managing anxiety may be a moderating variable in pregnancy rate [Citation17]. Additionally, a meta-analysis study of the effects of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) on pregnancy outcomes in women treated with in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer (IVF-ET) treatment showed a significant improvement in pregnancy rates in infertile women who received CBT intervention [Citation18]. Based on the information from these studies, in order to increase the pregnancy rate of infertile women undergoing IVF, it is necessary to explore the most effective psychosocial interventions for emotional regulation.

Psychosocial interventions for infertile women undergoing IVF include cognitive behavioral therapy, mind-body therapy, counseling, education, and expressive writing [Citation17]. Meta-analysis studies on these psychosocial interventions have included both infertile women and their partners [Citation17,Citation19]. To expand the current literature, we focused on the effect of psychosocial interventions conducted only on infertile women undergoing IVF.

This study conducted a systematic literature review and meta-analysis to analyze the effects of psychosocial interventions on pregnancy rates in infertile women undergoing IVF. The specific objectives were as follows: (1) to investigate the characteristics of the literature on the effects of psychosocial interventions for infertile women undergoing IVF on pregnancy rate, and (2) to test the efficacy of psychosocial interventions performed on infertile women undergoing IVF on the pregnancy rate by calculating effect sizes.

Methods

This study was a systematic literature review and meta-analysis conducted to analyze the results of randomized experimental studies that investigated the effects of psychosocial interventions on pregnancy rates in infertile women undergoing IVF.

This systematic review and meta-analysis were registered with PROSPERO (Registration number: CRD42022309169).

Core questions

This study used the Participants, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, Study Design (PICO-SD) tool as follows: (1) population (P), infertile women undergoing IVF; (2) intervention (I), psychosocial interventions, including mind-body therapies (meditation, yoga, relaxation and breathing techniques, tai chi, qigong, hypnosis, biofeedback, etc.), counseling, cognitive behavioral therapy (cognitive therapy, behavioral therapy), writing, education, and information provision; (3) comparison (C), no treatment control group, placebo group, or alternative group; (4) outcomes (O), the pregnancy rate; (5) study design (SD), randomized controlled trials (RCT).

Search strategy

The study search was conducted in January 2021, and there was no restriction on the search period. To evaluate all the researched articles, the research period and language were not limited.

The international articles were searched in the Cochrane Library, PubMed, EMBASE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, and PsycARTICLES databases. In addition, the domestic articles were searched on the following search engines and databases; Research Information Sharing Service, Korean Studies Information Service System, Korean Medical Database, National Digital Science Library, Korean Society of Nursing Science, Korean Society of Adult Nursing, Korean Society of Women Health Nursing, and Korean Academy of Community Health Nursing.

Search keywords were determined using medical subject headings (MeSH) and life science term indices (EMBASE TREE; EMTREE). The target keywords included “infertility”, “infertile women”, “infetile*”, “sperm injections”, “intracytoplasmic”, “ICSI”, “intracytoplasmic sperm injection”, “fertilization in vitro”, “IVF”, “in vitro fertilization”, “infertility treatment”, “assisted reproductive technologies”, and “ART”. Intervention keywords included “psychosocial”, “psychoeducation”, “psycho*”, “psychia*”, “mind-body”, “body-mind-sprit”, “mindfulness”, “mindful*”, “yoga”, “meditation”, “relaxation”, “psychological”, “breathing”, “tai chi”, “qigong”, “hypnosis”, “biofeedback”, “cognitive behavioral therapy”, “cognitive behavioral”, “cognitive”, “behavioral”, “cogniti*”, “writing”, “education”, and “counselling”. Outcome variables included “pregnancy”, “pregnan*”, and “pregnancy rate”. Each subject was connected by an AND using a search term.

Study selection

The inclusion criteria for the literature were as follows: (1) psychosocial intervention was performed on infertile women undergoing IVF; (2) the outcome variable was pregnancy rate; (3) RCTs; (4) published in English or Korean in a peer-reviewed journal. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) study subjects other than infertile women undergoing IVF; (2) research related to medical treatment (including Eastern medicine); (3) pilot works of research that were not followed by the main ones; (4) literature reviews; (5) case studies; (6) studies published in languages other than English or Korean that are difficult for researchers to read.

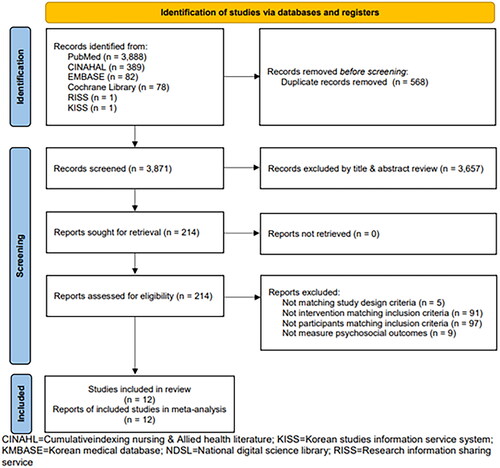

This study was conducted according to the systematic literature review reporting guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) group [Citation20]. The step-by-step literature selection process is shown in . We identified 4437 English literature articles in the primary literature search, including 3888 from PubMed, 78 from the Cochrane Library, 389 from CINAHL, 82 from EMBASE, 1 from RISS, and 1 from KISS. Two articles in Korean were found in the Korean Society of Nursing. Among the retrieved articles, 568 duplicates were excluded, resulting in 3871 articles. Subsequently, we excluded 3657 articles based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria after reviewing the titles and abstracts. After reviewing the full text of the remaining 214 articles, we excluded 202 that did not meet the selection criteria; finally, 12 articles were selected for analysis.

The literature selection and review were conducted by three researchers, and each researcher completed an independent review and prepared a result table in a unified format. The results were checked through regular twice-weekly research meetings and selected studies were cross-reviewed. If there was disagreement among the researchers, they reviewed the text and discussed it until a consensus was reached.

Quality assessment of the selected studies

The quality of the selected studies was evaluated using a revised tool for assessing the risk of bias, the RoB 2.0 (The Cochrane Collaboration, England, London) [Citation21]. The RoB 2.0 consists of five domains: “randomization process”, “deviations from intended interventions”, “missing outcome data”, “measurement of the outcome”, and “selection of the reported result”, which are evaluated as “low risk of bias”, “high risk of bias” or “some concerns” [Citation22]. The studies were graded as follows: (1) “high risk of bias” when at least one domain had a high risk of bias or multiple domains had some concerns, (2) “low risk of bias” when a low risk of bias was determined for all domains, or (3) “some concerns” if at least one domain had some concerns but no domain had a great risk of bias [Citation22]. As in the literature selection, disagreements were resolved by jointly examining the text and discussing it until a consensus was reached.

Data analysis

The characteristics of the articles, including the year of publication, author, country of publication, number of samples, method, number of interventions in the experimental and control groups, and outcome variables, were analyzed.

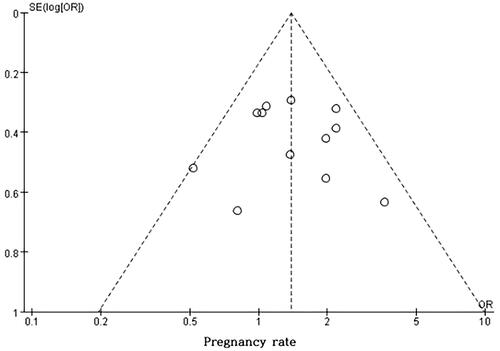

The interventions’ homogeneity and effect sizes were analyzed using RevMan 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration). The main variable heterogeneity was assessed using the Chi-Square Null Hypothesis Test. When I2 was 0%, 30–60% and 75%, it indicated no, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively [Citation21]. In this study, the effect size was calculated using the fixed-effects model when heterogeneity was moderate or none, and the effect size was calculated and analyzed using the random-effects model when heterogeneity was high. In the case of high heterogeneity, the robustness of the results was investigated using sensitivity analysis [Citation23]. A forest plot was used to confirm the direction of the effect and the confidence interval (CI). Regarding effect sizes for the outcome, standardized mean difference (SMD) was used for continuous data, and odds ratio (OR; the ratio between two groups when a specific event occurs and when no event occurs) was used for dichotomous data. The significance level for the effect size was set at 0.05, and the CI was set at 95%. Finally, a funnel plot was used to evaluate publication bias to test the validity of the entire study. Egger’s Regression Test was conducted to examine the relationship between standard error and effect size to check the significance of asymmetry.

Results

Characteristics of the selected studies

shows the characteristics of the studies. The studies were conducted in the following countries: China (3, 25.0%); Israel (2, 16.7%); the Netherlands (2, 16.7%); Turkey, Brazil, Denmark, Macedonia, and Greece (8.3%). Regarding the publication year of the studies, four (33.3%) studies were published between 2000 and 2010, and eight (66.7%) studies were published after 2010. Six (50.0%) studies had <100 participants, five (41.7%) had 100–200 participants, and one (8.3%) had >200 participants, including the experimental and control groups. Regarding the type of intervention, the control groups always received routine treatment. For the experimental group, five (41.7%) studies used mind-body therapy interventions, one (8.3%) study used counseling intervention, one (8.3%) study used cognitive behavioral therapy intervention, two (16.7%) studies used writing interventions, and three (25.0%) studies used education and information provision interventions. Regarding the number of sessions in the interventions, five (41.7%) studies had <5 sessions, two (16.7%) studies had 5–9 sessions, and three (25.0%) studies had ≥10 sessions. Six (50.0%) studies provided the intervention before IVF, two (16.7%) studies provided the intervention during IVF, one (8.3%) study provided the intervention for embryo transfer, two (16.7%) studies provided the intervention between embryo transfer and pregnancy test, and one (8.3%) study provided the intervention before and after IVF and after embryo transfer. Seven (58.3%) studies had individual interventions and five (41.7%) studies had group interventions.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies (n = 12).

Quality assessment of the selected studies

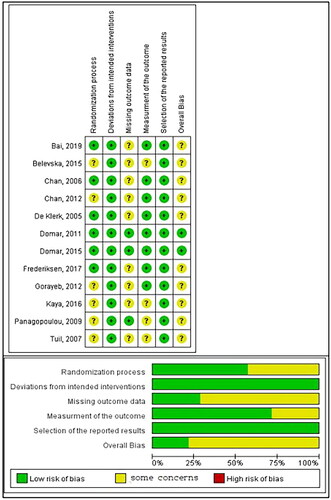

The risk of bias in the randomization process, deviations from the intended intervention, missing outcome data, outcome measurement, and selection of the reported results are shown in .

There were six studies in which the assignment order was concealed using computer programs and random numbers; however, for the other 6 studies, the appropriateness was unidentified due to an absence of a clear method for concealing the assignment order. Based on the foregoing results, six and six studies were evaluated as “some concerns” and “low risk of bias”, respectively, in “randomization procedure”. In selected studies, we determined that the research results were unbiased because the participants, researchers, and evaluators were blinded. Thus, all articles were assessed as “low risk of bias” in “deviations from intended interventions”. In the domain of “the missing outcome data”, three studies that did not show missing data were evaluated as “low risk of bias”, and nine studies in which outcome data for all participants were not specified were determined as “some concerns”. In terms of “measurement of the outcome”, four studies that did not clearly suggest a method for measuring the outcome were evaluated as “some concerns”, and eight studies with a clear method of reviewing the results and no difference in measurement between the experimental group and the control group were determined like “low risk of bias”. Regarding the “selection of the reported result”, all 12 studies were examined based on a predetermined analysis plan and assessed as “low risk of bias”. The general risk of bias overall matches the worst one in all domains. Considering the aforementioned findings collectively, we found that 2 studies had a “low risk of bias”, and 10 studies had “some concerns”.

Effects of psychosocial interventions on pregnancy rates

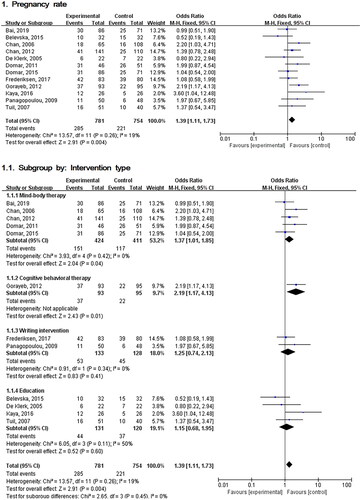

The effects of psychosocial interventions on the pregnancy rate of infertile women undergoing IVF are shown in . The homogeneity test results were Q (Chi-square) = 13.57, df = 11 (p = 0.260), and I2 = 19%. The effect size on the pregnancy rate was 1.39 (95% CI: 1.11–1.71), indicating that there was a significant difference between the pregnancy rates of the experimental groups and the control groups (Z = 2.91, p = 0.004).

Figure 3. Comparison of pregnancy rate between experimental and control group.

Effects of each type of psychosocial intervention

The results of specific psychosocial interventions are shown in .

Mind–body therapy

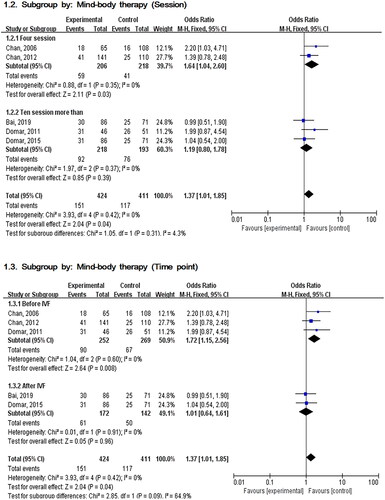

For the five studies reporting the effects of Mind–body therapy on pregnancy rates, the homogeneity test revealed that Q (Chi-square) = 3.93, df = 4 (p = 0.420), and I2 = 0%. The effect size was 1.37 (95% CI: 1.01–1.85), and there was a significant difference in the pregnancy rates between the experimental group and the control group (Z = 2.04, p = 0.040).

To compare the difference in effect size according to the number of sessions of Mind–body therapy, two studies with 4 sessions and three studies with more than 10 sessions were analyzed, respectively. The homogeneity test of the four-session studies showed Q (Chi-square) = 0.88, df = 1 (p = 0.350) and I2 = 0%, and the effect size was 1.64 (95% CI: 1.04–2.60), indicating that there was a statistically significant difference (Z = 2.11, p = 0.030). The homogeneity test of studies with more than 10 sessions showed Q (Chi-square) = 1.97, df = 2 (p = 0.370) and I2 = 0%, with an effect size of 1.19 (95% CI: 0.08–1.78), that there was no significant difference in the pregnancy rate (Z = 0.85, p = 0.390).

In order to compare the difference in the effect size according to the time of intervention, the effect size was analyzed by dividing it into before and after IVF initiation. For the three studies where the time point of Mind–body therapy was before the IVF initiation, the homogeneity test demonstrated Q (Chi-square) = 1.04, df = 2 (p = 0.600) and I2 = 0%. The effect size was 1.72 (95% CI: 1.15–2.56); a statistically significant difference was reported (Z = 2.64, p = 0.008). There were two studies in which the time point of Mind–body treatment was after the IVF initiation; The homogeneity test demonstrated Q (Chi-square) = 0.01, df = 1 (p = 0.910) and I2 = 0%. The effect size was 1.01 (95% CI: 0.64–1.61), and there was no statistically significant difference in pregnancy rates (Z = 0.05, p = 0.960).

Cognitive behavioral therapy

For the one study reporting the effect of cognitive behavioral therapy on pregnancy rate, the effect size was 2.19 (95% CI: 1.17–4.13), indicating that there was a significant difference between the pregnancy rate of the experimental group and the control group (Z = 2.43, p = 0.010).

Expressive writing

For the two studies reporting the effect of expressive writing on pregnancy rate, the homogeneity test revealed that Q (Chi-square) = 0.91, df = 1 (p = 0.340), and I2 = 0%. The effect size was 1.25 (95% CI: 0.74–2.13), and there was no significant difference in pregnancy rates between the experimental group and the control group (Z = 0.83, p = 0.410).

Education and information provision

For the four studies on the effects of education and information provision on pregnancy rates, the homogeneity test revealed that Q (Chi-square) = 6.05, df = 3 (p = 0.060), and I2 = 50%. The effect size was 1.15 (95% CI: 0.68–1.95), and there was no significant difference in the pregnancy rates between the experimental group and the control group (Z = 0.52, p = 0.600).

Publication bias

We found that the distribution did not deviate significantly from left-right symmetry with respect to the centerline and was symmetrical (). To verify this more objectively, we conducted an Egger’s Regression Test (p = 0.487), which revealed no publication bias.

Discussion

We conducted a systematic literature review and meta-analysis to determine the effects of psychosocial interventions on the pregnancy rate of infertile women undergoing IVF. The results of this study confirmed that psychosocial interventions, particularly cognitive behavioral therapy and Mind–body therapy, had a significant effect on the pregnancy rate of infertile women undergoing IVF. This result is similar to that of a previous meta-analysis [Citation17,Citation19] that the pregnancy rate increases when psychological discomfort in infertile couples is alleviated. In addition, it is consistent with the results of previous meta-analysis studies that cognitive behavioral therapy, one of the psychosocial interventions, is effective in improving the pregnancy rate of infertile women [Citation18]. Psychosocial interventions have been developed to provide emotional support under the recognition that depression, anxiety, psychological discomfort, and burden have a significant effect on people suffering from infertility [Citation36]. Psychosocial factors, such as depression, anxiety, and discomfort, are associated with a decrease in pregnancy success rate [Citation17,Citation37]. In addition, previous studies [Citation17,Citation19] have reported that psychological support increases the pregnancy rate by alleviating the burden associated with infertility. Therefore, it is necessary to provide appropriate psychosocial interventions to alleviate psychological discomforts such as depression, anxiety, and stress, and ultimately increase the pregnancy rate among infertile women, especially when undergoing IVF.

We found that cognitive behavioral therapy was the most effective intervention for improved pregnancy rates. Cognitive behavioral therapy is a form of psychotherapy that helps people clarify and change destructive or negative thoughts that negatively affect behavior and emotions [Citation38]. As a result of cognitive behavioral therapy for infertile women undergoing IVF, depression, anxiety, and stress were all significantly relieved, suggesting that it could be a useful intervention for infertile women undergoing IVF [Citation39]. However, only one study investigated cognitive behavioral therapy and pregnancy rate, so it is difficult to assert its effectiveness. In addition, because the study was conducted on infertile women who underwent IVF more than twice, the results are somewhat limited [Citation32]. Nevertheless, in a recent meta-analysis on the effect of cognitive behavioral therapy on the pregnancy rate, a meta-analysis of ten studies revealed that cognitive behavioral therapy is an effective intervention for pregnancy rate [Citation18]. This is the same result as the result of this study, and it can be said that it strongly shows that cognitive behavioral therapy is an effective intervention for the pregnancy rate. The reason for the large difference in the number of selected studies was that pilot studies were not included in this study, only studies in a language that researchers could read were selected and Chinese literature was excluded. In addition, the study that performed cognitive coping and relaxation intervention was classified as Mind–body therapy in this study, but it was classified as a type of cognitive behavioral therapy intervention in a study by Li et al. As such, in selecting studies for meta-analysis, it is necessary to consider that there are differences in the selected studies depending on the language of the researcher, and there are differences in the classification of interventions according to the opinion of the researcher.

This study confirmed that Mind–body therapy was effective in improving the pregnancy rate of infertile women undergoing IVF. Mind–body therapy is an intervention that focuses on the interaction of thoughts, mind, body, and behavior, affecting overall health and physical function [Citation40]. Mind–body therapies include meditation, tai chi, yoga, and relaxation techniques (gradual relaxation, image therapy, biofeedback, self-hypnosis, deep breathing, and self-discipline) [Citation41]. Mental and physical therapy have been reported to be effective in relieving anxiety and depression in infertile women [Citation42]. Considering that anxiety and depression are related to the pregnancy rate of infertile women undergoing IVF [Citation16,Citation17], the anxiety- and depression-relieving functions of Mind–body therapy likely enhance the pregnancy rate of infertile women undergoing IVF.

There were five studies that confirmed the effect of Mind–body therapy, and all were targeted at infertile women who underwent primary IVF. According to the number of sessions, subgroup analysis was conducted by grouping them into two studies with less than 10 sessions and three studies with more than 10 sessions. As a result, interventions with less than 10 sessions had a significant effect. Two studies that showed a significant effect each provided 4 sessions of intervention. In addition, subgroup analyzes were conducted according to the time of intervention in mind and body therapy; three studies before IVF initiation, and two studies after IVF initiation. As a result, if the intervention was provided before IVF, it was found that there was a significant effect on the pregnancy rate. Therefore, in order to increase the pregnancy rate by applying Mind–body therapy to infertile women undergoing primary IVF, it is necessary to configure it so that it can be applied at least four times to less than ten times before IVF.

Expressive writing, education, and information provision interventions did not have any significant effect on the improvement of the pregnancy rate. Education and information provision are the basis for communicating with the target audience and encouraging their participation [Citation43]. These results are similar to those of a study that found that expressive writing has an effect on the infertility-related stress of infertile couples undergoing IVF treatment, but has no significant effect on pregnancy rate [Citation31]. Although there was no significant effect on the pregnancy rate, expressive writing is a cost-effective intervention that can alleviate pregnancy-related stress or depression, and it is an intervention that can be implemented at home [Citation31]. Thus, expressive writing can be used among infertile women with high levels of stress undergoing IVF as a stress-relief intervention.

The results indicate that providing psychosocial interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy or Mind–body therapy, to infertile women undergoing IVF may help increase pregnancy rates. In the case of Mind–body therapy, it is necessary to apply the appropriate number of sessions at relevant time points for positive results.

The current study had some limitations. First, none of the studies included in the analysis were conducted in Korea. Therefore, there may be limitations to extending the results to infertile Korean women. Second, we could not determine if the round of IVF (first round, second round, etc.) had an effect on the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy and Mind–body therapy. Therefore, future studies should examine whether various subject characteristics (e.g. the round of IVF procedure, the time point of procedures) have an effect on the pregnancy rate. Third, in the case of the effect of cognitive behavioral therapy, there was a difference from the selected study in the previous meta-analysis study. This is thought to be because, in the process of selecting literature for systematic literature review and meta-analysis, there may be differences in the literature included depending on the researcher’s ability to interpret the language, and the classification of interventions may differ depending on the opinion of the researcher. In spite of its limitations, this study is meaningful in that it provides a basis for suggesting cost-effective interventions to increase the pregnancy rate of infertile women undergoing IVF.

Conclusions

We found that cognitive behavioral therapy and Mind–body therapy had significant effects on the pregnancy rate of infertile women undergoing IVF. The results of this study can be used by healthcare professionals to develop effective interventions for infertile women and thereby help increase the pregnancy rate. If the pregnancy rate effect of psychosocial interventions for infertile women has not been confirmed as in Korea, the basis of in-depth research by medical experts to develop effective interventions for infertile women that will help increase the fertility rate based on the results of this study can be. This study’s results, derived from a best-level systematic literature review and meta-analysis, are noteworthy in that they present quality scientific data that can be used in evidence-based nursing research. Additionally, this study was able to confirm the positive effect of psychosocial interventions on the pregnancy rate by specifically selecting RCT research during the literature selection and extraction process. An increase in the pregnancy rate can be expected through the provision of psychosocial interventions to infertile women who are suffering psychologically and physically. Therefore, active management such as applying psychosocial intervention to infertile women undergoing IVF in nursing practice may have a positive effect on the pregnancy rate of infertile women. The use of non-pharmacological interventions for healthy pregnancies and childbirth in infertile women is considered the first treatment option. Considering this, the results of this study, which synthesized the effects of RCT research through meta-analysis, are significant. By providing an objective platform for the application of psychosocial interventions to infertile women, these results can form the basis for planning the future direction of education and counseling for infertile women. Furthermore, it is expected that the results of this study will form the basis for the future development of an effective pre-pregnancy nursing intervention program for infertile women.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Statistics Research Institute [Internet]. Characteristics of children’s households by marriage period. Daejeon (South Korea): Statistics Korea; 2019. http://kostat.go.kr/sri/srikor/srikor_pbl/2/index.board?bmode=read&aSeq=382516 Korean.

- Medical Today [Internet]. Last year’s domestic total fertility rate of 0.96… lowest in the OECD. Seoul (South Korea): Medical Today; 2019. Available from: http://www.mdtoday.co.kr/mdtoday/index.html?no=344340 Korean.

- Ministry of Health and Welfare [Internet]. Infertility treatment and dementia neurocognitive health insurance. Sejong (South Korea): Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2017. Available from: http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/al/sal0301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=04&MENU_ID=0403&CONT_SEQ=341710 Korean.

- Ministry of Health and Welfare [Internet]. From this year, the burden of treatment costs for infertile couples will be reduced even more: Ministry of Health and Welfare, expanding the targets and contents of government support projects for infertility treatment. Sejong (South Korea): Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2019. Available from: http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/al/sal0301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=04&MENU_ID=0403&CONT_SEQ=347302 Korean.

- Oh MH. Current status and issues of assistance for infertile couples in South Korea and Japan. Jap Cult Res. 2020;73(0):241–259.

- Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs [Internet]. Evaluation of the results of the 2017 support project for infertile couples and analysis of support for low income families. Sejong (South Korea): Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs; 2018. Available from: https://www.prism.go.kr/homepage/entire/researchDetail.do?researchId=1351000-201900284 Korean.

- CHA Fertility Centers [Internet]. In-vitro fertilization (IVF). Seoul (South Korea): CHA Fertility Centers; 2015. Available from: https://seoul.chamc.co.kr/info/info.aspx?menuCode=2318 Korean.

- Hwang NM. Analysis of factors affecting depression of infertile women. Health Social Welfare Rev. 2013;33(3):161–187.

- Boivin J, Lancastle D. Medical waiting periods: imminence, emotions and coping. Womens Health. 2010;6(1):59–69.

- Yang SN. The experience of infertility treatments among working women without children. Korean Council Soc Welfare Edu. 2019;48(0):93–120.

- Kang SR, Lee YJ. Phenomenological study on the experiences of infertility among married women. Women’s Stud Rev. 2015;32(2):61–89. Korean.

- Öyekçin DG, Gülpek D, Sahin EM, et al. Depression, anxiety, body image, sexual functioning, and dyadic adjustment associated with dialysis type in chronic renal failure. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2012;43(3):227–241.

- Villar RR, Fernández SP, Garea CC, et al. Quality of life and anxiety in women with breast cancer before and after treatment. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. 2017;25(0):1–13.

- Matthiesen SMS, Frederiksen Y, Ingerslev HJ, et al. Stress, distress and outcome of assisted reproductive technology (ART): a meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(10):2763–2776.

- Zhou FJ, Cai YN, Dong YZ. Stress increases the risk of pregnancy failure in couples undergoing IVF. Stress. 2019;22(4):414–420.

- Cesta CE, Viktorin A, Olsson H, et al. Depression, anxiety, and antidepressant treatment in women: association with in vitro fertilization outcome. Fertil Steril. 2016;105(6):1594–1602.

- Frederiksen Y, Vestergaard IF, Skovgård NG, et al. Efficacy of psychosocial interventions for psychological and pregnancy outcomes in infertile women and men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2015;5(1):e006592.

- Li Y, Shi Y, Xu C, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy improves pregnancy outcomes of in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int Med Res. 2021;49(11):3000605211050798.

- Hämmerli K, Znoj H, Barth J. The efficacy of psychological interventions for infertile patients: a meta-analysis examining mental health and pregnancy rate. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15(3):279–295.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–1012.

- Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 6.1. London (UK): The Cochrane Collaboration.

- Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898.

- Kim SY, Park JE, Seo HJ, et al. NECA’s guidance for undertaking systematic reviews and meta-analyses for intervention. 2nd ed. Seoul (South Korea): National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency.

- Bai CF, Cui NX, Xu X, et al. Effectiveness of two guided self-administered interventions for psychological distress among women with infertility: a three-armed, randomized controlled trial. Human Reprod. 2019;34(7):1235–1248.

- Belevska J. The impact of psycho-education on in vitro fertilization treatment efficiency. PRILOZI, 2015;36(2):211–216.

- Chan CHY, Ng EHY, Chan CLW, et al. Effectiveness of psychosocial group intervention for reducing anxiety in women undergoing in vitro fertilization: a randomized controlled study. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(2):339–346.

- Chan CHY, Chan CLW, Ng EHY, et al. Incorporating spirituality in psychosocial group intervention for women undergoing in vitro fertilization: a prospective randomized controlled study. Psychol Psychother: Theory, Res Pract. 2012;85(4):356–373.

- De Klerk C, Hunfeld JAM, Duivenvoorden HJ, et al. Effectiveness of a psychosocial counseling intervention for first-time IVF couples: a randomized controlled trial. Human Reprod. 2005;20(5):1333–1338.

- Domar AD, Rooney KL, Wiegand B, et al. Impact of a group mind/body intervention on pregnancy rates in IVF patients. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(7):2269–2273.

- Domar AD, Gross J, Kristin Rooney BA, et al. Exploratory randomized trial on the effect of a brief psychological intervention on emotions, quality of life, discontinuation, and pregnancy rates in in vitro fertilization patients. Fertil Steril. 2015;104(2):440–451.

- Frederiksen Y, O’Toole MS, Mehlsen MY, et al. The effect of expressive writing intervention for infertile couples: a randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(2):391–402.

- Gorayeb R, Borsari ACT, Rosa-e-Silva ACJS, et al. Brief cognitive behavioral intervention in groups in a Brazilian assisted reproduction program. Behav Med. 2012;38(2):29–35.

- Kaya Y, Beji NK, Aydin Y, et al. The effect of health-promoting lifestyle education on the treatment of unexplained female infertility. Euro J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;207:109–114.

- Panagopoulou E, Montgomery A, Tarlatzis B. Experimental emotional disclosure in women undergoing infertility treatment: are drop outs better off? Social Sci Med. 2009;69:678–681.

- Tuil WS, Verhaak CM, Braat DDM, et al. Empowering patients undergoing in vitro fertilization by providing internet access to medical data. Fertil Steril. 2007;88(2):361–368.

- Chow KM, Cheung MC, Cheung IK. Psychosocial interventions for infertile couples: a critical review. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(15–16):2101–2113.

- Demyttenaere K, Bonte L, Gheldof M, et al. Coping style and depression level influence outcome in in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 1998;69(6):1026–1033.

- Hofmann SG, Asnaani A, Vonk IJ, et al. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Cognit Ther Res. 2012;36(5):427–440.

- Mosalanejad L, Koolaee AK, Jamali S. Effect of cognitive behavioral therapy in mental health and hardiness of infertile women receiving assisted reproductive therapy (ART). Iran J Reprod Med. 2012;10(5):483–488.

- Elkins G, Fisher W, Johnson A. Mind–body therapies in integrative oncology. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2010;11(3–4):128–140.

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health [Internet]. Mind and body practices. Bethesda (MD): National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health; 2017. Available from: https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/mind-and-body-practices.

- Gaitzsch H, Benard J, Hugon-Rodin J, et al. The effect of mind–body interventions on psychological and pregnancy outcomes in infertile women: a systematic review. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2020;23(4):479–491.

- De Beradis D, Mazza M, Martini S, et al. Psychopathology, emotional aspects and psychological counselling in infertility: a review. Clin Terminol. 2014;165(3):163–169.