?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

A number of studies have suggested close associations between maternal postpartum mental health (depressive and anxious symptoms), mother-infant bonding, and parenting stress. However, the relationship between maternal bonding and parenting stresshas hardly been explored in published literature. This cross-sectional study explored whether maternal bonding could mediate the effect of postpartum maternal mental health on parenting stress. This study assessed maternal bonding (MPAS), depressive and anxious symptoms (EPDS; STAI), and parenting stress (PSI) at 3 months postpartum in a community sample of 105 women (M (SD) = 32.60 (4.18) years old). Spearman’s correlation analyses showed moderate to high correlations between these factors. The three mediation models run showed that mother’s MPAS partially mitigates the effects of EPDS (b = 0.71; SE = 0.217; 95% CI = 0.290/1.136) and STAI State (b = 0.39; SE = 0.113; 95% CI = 0.178/0.625) on PSI, and totally mediated the relationship between STAI Trait and PSI (b = 0.59; SE = 0.155; 95% CI = 0.303/0.912). Maternal bonding resulted to be a relevant factor in the association between maternal mental health and parenting stress. This highlights the importance of interventions focusing on mother-infant relationship to reduce parenting stress and prevent developmental difficulties in children.

Introduction

Perceived maternal bonding, defined as the emotional connection that the mother develops toward her infant postpartum, is vital to healthy childhood development [Citation1]. The emerging relationship between mother and infant ensures that the mother strives to meet the infant’s needs and copes with the demanding tasks of child rearing [Citation2]. As proposed by Condon and Corkindale [Citation3], a threefold set of mutual features characterizes the maternal bond: the mother’s pleasure in interacting with the infant; her sense of developing competence and ability to understand and meet the infant’s needs; and her acceptance and tolerance of the demands of the maternal role [Citation3,Citation4].

The bonding process has tremendous implications for both mother and child and the mother’s emotional response to her infant is affected by many factors. The physiological, psychological, and social changes involved in this process, together with the requirements to adjust to the infant’s many needs, can be challenging and overwhelming for some mothers within the first months of the postpartum period [Citation5].

These changes may increase maternal vulnerability to psychological difficulties and affect the process of forming an emotional bond with the child. Both theory and empirical evidence suggest that internalized negative affect, such as postpartum depression and anxiety, can hinder maternal ability to bond with the newborn and is associated with parenting stress [Citation4,Citation6–8].

Studies have consistently linked maternal depressive symptoms to impaired mother- to-infant bonding postpartum [Citation9–14]. Indeed, research indicates that even subclinical depressive symptoms can negatively affect the developing maternal-infant bond during the first months postpartum [Citation15,Citation16]. Mason et al. [Citation17] suggest that maternal depression can have a negative impact on maternal-infant bonding with the finding that maternal bonding plays a role in mediating depression and later child social-emotional outcomes.

Considering parenting stress as the consequence of a caregiver’s perception that the demands of parenting are greater than the resources available to cope with them [Citation18,Citation19], the link between maternal depressive symptoms and parenting stress is evident [Citation20–23]. In a prospective study, Leigh and Milgrom [Citation20] found postnatal depression the strongest predictor of parenting stress, with antenatal anxiety and depression not significant in the hierarchical regression.

Although maternal mental health studies historically have focused on depressive symptoms, recent evidence has highlighted the negative impact that high levels of postnatal anxiety have on women and their children [Citation24,Citation25]. Even so, postnatal anxiety has received relatively limited attention from researchers, and few studies have explored its relationship with maternal bonding in the postpartum period. Studies show that anxiety is associated with poorer bonding, characterized by stronger negative maternal emotions toward and less emotional involvement with the baby [Citation7,Citation9,Citation11,Citation26,Citation27]. Studies also found an association between maternal anxiety symptoms and parenting stress, with anxious mothers perceiving themselves as less confident when caring for their child [Citation28–32]. The specific relationship between maternal bonding and parenting stress has not been extensively explored despite the importance of maternal bonding to managing both physically and psychologically strenuous childcare-related tasks. Furthermore, only a few studies have examined the link between maternal bonding, maternal mental health (depressive and/or anxious symptoms), and parenting stress in the first few months after birth. In one, Lutkiewicz et al. [Citation11] identified a significant correlation between maternal stress levels associated with parenthood, anxiety, and postnatal depressive symptoms and the maternal-infant bond in the early postpartum period (1–3 days after delivery). In another study, Reck and colleagues [Citation33] showed that higher maternal bonding partially mediates the negative effects of maternal depression on parenting stress.

To the best of our knowledge, however, no study has explored the specific links between maternal mental health (depressive and/or anxious symptoms), maternal bonding, and parenting stress in a community sample at 3 months after childbirth. The present study differs from previous work [Citation11] that explored these links by focusing on the 3 months after childbirth. We chose this time frame because previous studies have shown how mother and infant adapt to their new life in the first 3 months after birth and how maternal bonding becomes more stable at the end of this period [Citation3].

Based on the available literature, this cross-sectional study explores: (1) the associations between mother-infant bonding and maternal mental health (depressive and/or anxious symptoms), and parenting stress; (2) possible mediating effects of maternal bonding between maternal mental health (depressive and/or anxious symptoms), and parenting stress.

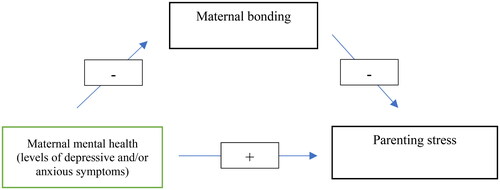

The mediation models hypothesized in the present study suggest that depressive and/or anxious symptoms affects parenting stress through maternal bonding to the child as a mediator. These models suggest that mothers with higher levels of anxious and/or depressive symptoms perceive their bonding as compromised and greater parenting stress. The hypothesized directions of these links are supported by studies, reported above, suggesting that internalized negative affects may hinder a mother’s ability to form a bond with her infant and that postnatal maternal depression and anxiety are predictors of parenting stress [Citation7,Citation8,Citation20,Citation32]. Furthermore, the mediation models proposed assume a mediating role played by mother to infant bond between maternal mental health and parenting stress. As the complex pathways likely to exist between the investigated variables have been poorly explored in detail, in the present study the mediation models have been conceptualized by referring to Reck and colleagues [Citation33]. The authors, testing two different mediation models, showed that is maternal bonding to function as a mediator between postpartum depression and parenting stress, and not parenting stress to mediate the relationship between postpartum depression and maternal bonding. illustrates the conceptual model to test maternal bonding as a mediator between maternal mental health and parenting stress.

Materials and methods

Procedures and participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards for research outlined in the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and the Code of Conduct of the American Psychological Association [Citation34]. Ethical approval was obtained from the Bio-Ethical Committee for Research at the University of Perugia.

Data were collected in the Region Umbria from two public services and three private associations that provided regular meetings for new parents in the first months of a child’s life between 2019 and 2020. Mothers were enrolled through convenience sampling. A researcher invited the mothers to participate in a study about how they felt. Inclusion criteria were: (a) 3 months post-partum; (b) understanding the Italian language; (c) signed written informed consent. After signing the written informed consent form and agreeing to participate, all the women completed a paper–pencil booklet at their homes. This booklet comprised a socio-demographic questionnaire and standardized Italian versions of self-report questionnaires.

No incentives were given and it was emphasized that participation in the study was voluntary and that mothers could withdraw at any moment. Confidentiality was ensured by replacing personal information with a numeric code, and all data were stored at the University’s offices; only the research team had access to the data.

A priori power analysis was conducted using G* to test a multiple regression using a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15), an alpha of 0.05, and two main predictors. Results showed that a total sample of 74 participants was needed to achieve a power of 0.95. Considering expected missing data, 122 mothers were invited to participate. Nine mothers (7%) dropped out of the study due to a lack of time or interest. Of the 113 remaining participants, eight were excluded because they did not fully complete the questionnaires. No one requested to withdraw. The final sample comprised 105 women between the ages of 18 and 46.

Measures

Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS)

The EPDS is a 10-item scale that assesses depression symptoms among pregnant women and mothers using a four-point scale [Citation35]. Higher scores reflect greater depression. This study used the Italian version [Citation36], which has good internal reliability (α = 0.78), high sensitivity, and good positive predictive value. Presence of depression symptoms was defined by an EPDS score ≥ 9 used as the cutoff in the community screenings [Citation37]. Our EPDS showed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.75.

State and trait anxiety inventory (STAI) - Form Y

The STAI is a 40-item scale that assesses two different kinds of anxiety using a four-point scale: State Anxiety is a transient emotional state marked by feelings of unease, stress, and fear regarding a specific situation, and Trait Anxiety is a personal and stable feature. The total score ranged from 20 to 80 for each scale; a score of 40 was the predictive threshold value of anxiety symptoms [Citation38]. This study used the Italian version, translated and validated by Pedrabissi and Santinello [Citation39], which showed good internal consistency and adequate test-retest reliability, in line with the original version. In the current study, the two subscales showed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92 and 0.82.

Maternal postnatal attachment scale (MPAS)

The MPAS is a 19-item scale that assesses the mother’s emotional response to her infant relating to the parent-to-infant bond [Citation3]. Each item scored from 1 to 5, where 1 represents lower bonding and 5 higher bonding. Scopesi and collegues [Citation40] translated and validated the MPAS in Italian, but their factor analysis did not confirm the three-factor structure of the original version, suggesting the use of the total scale score. The total score is calculated from 19 to 95, where low scores correspond to less optimal maternal bonding toward the infant. There is no validated cutoff for the MPAS and the total score is used in research as an indicator of the quality of the mother-child bond [Citation41]. The internal consistency of the MPAS is adequate (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.77), and the score distribution tends to be skewed toward higher attachment scores. In our study, the MPAS showed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.70.

Parenting Stress Index: short form (PSI-SF)

The PSI-SF (PSI), is a 36-item short form of the Parenting Stress Index using a 5-point ordinal Likert scale. It comprises three subscales and a total score calculated by adding those of the subscales [Citation18]. The three subscales are: Parental Distress (PD) to assess the level of emotional and psychological stress experienced by parents in their role as caregivers; Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction (CDI), to assess parents’ perceptions of dysfunctional or problematic interactions with their children; Difficult Child (DC) to assess the parents’ perceptions of challenging or stressful attitudes and behaviors exhibited by their children. The total stress score indicates the overall level of stress a person feels as a parent. Our study used the Italian version [Citation42] and the total stress score in the analyses. The total score ranged from 36 to 180; a score > 87 was used as the cutoff as high level of stress. In the present study the three subscales showed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87 for PD, 0.92 for CDI and 0.90 for DC. The Total stress score showed an alpha of 0.91.

Data analysis

Our final analyzed sample did not include subjects with missing data and those who did not answer more than 2% of the items of each questionnaire. Non-parametric statistical techniques were performed due to the non-normal distribution of three out of six main studied variables (EPDS; STAI State and Trait; PSI). Spearman correlations and mediation analyses were performed to assess our aims after calculating the descriptive statistics, including the mean, standard deviation, and percentage for all the variables analyzed.

Spearman correlation analyses explored the existing relationship among demographic variables, EPDS, STAI State and Trait, MPAS, and PSI Subscales and Total score to check for any relationships between the demographic variables and the studied measures before conducting the main analyses. The effect sizes were interpreted according to Cohen, where correlations of 0.10, 0.30, and 0.50 represented small, medium, and strong effects, respectively. Only correlations between medium and strong effects were considered. We conducted mediation models to verify the indirect effects of the EPDS and STAI subscales on the PSI through MPAS. If all PSI subscales correlate in the same direction with the mediator, only the PSI Total Score is used in the mediation analysis.

All analyses were carried out using the Statistical Package for Social Science version 26 [Citation43]. We used PROCESS macro v.4.0 in SPSS developed by Preacher et al. [Citation44] to perform the mediation analysis. We selected the bootstrapping technique (10,000 bootstrap samples) to examine the significance of indirect effects [Citation45,Citation46]. The mean indirect estimation effects for all mediational paths were computed, as well as the 95% confidence intervals and standard errors for each estimate. If zero was not included within the range of the confidence intervals, this suggested that the indirect effect was significant [Citation46].

Results

Descriptive statistics of demographic variables (N = 105)

Most mothers had a medium/high educational level, and 100% were married or cohabiting with the child’s fathers, mainly within a long-term relationship. shows the descriptive statistics of the demographic information, including the means, standard deviation, and percentage.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of demographic characteristics (N 105).

Descriptive statistics and Spearman correlations for the variables studied

In regard to mental health, the descriptive statistics showed that 76.2%, 75.7% and 61.5% of mothers reported respectively an EPDS, STAI State and STAI Trait scores below the clinical cutoff. The mean levels of EPDS and STAI, being lower than the cutoff, highlighted a non-clinical sample. Data showed low mean scores of PSI and high mean scores for MPAS, indicating a low levels of parenting stress and a positive mother-to-infant bonding. The Spearman correlations in show no relationships between demographic variables and the studied measures.

Table 2. Spearman correlations among demographic characteristics and variables studied (N 105).

Many significant relationships with medium and strong effects have been found between EPDS, STAI State and Trait with MPAS and with PSI subscales and total scores. Specifically, EPDS and STAI Trait showed positive correlations with PSI-PD and PSI Total Score, while the STAI State showed positive correlations with all subscales of PSI and total score. MPAS showed negative relationship with all three subscales of the PSI and with total score. Considering that all three PSI subscales showed strong correlations with MPAS in the same direction, in the subsequent analyses only the PSI total scale is included. reports the means, standard deviations, and correlations for the main variables studied.

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics and Spearman correlations among the main variables studied (N 105).

Mediation analyses: MPAS as a mediator

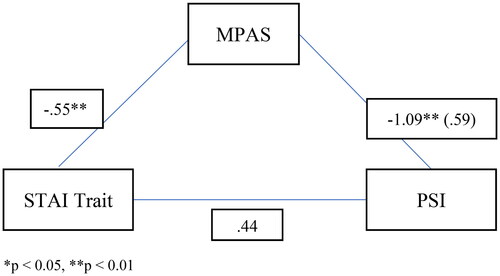

illustrates the mediation analyses testing MPAS as a mediator between EPDS and PSI. The data highlighted a significant total effect of the model tested ( = .27; F = 18.77; p < .001), explaining 27% of the PSI variance. There was a significant direct effect of the EPDS (b = .99; SE = .422; t = 2.33; p < .05; 95% CI = .148/1.823) on the PSI. MPAS mediated the direct effect. Specifically, EPDS significantly indirectly affected PSI through MPAS (b = .71; SE = .217; 95% CI = .290/1.136).

Figure 2. Mediation analysis testing the direct and indirect effects of EPDS on PSI mediated by MPAS.

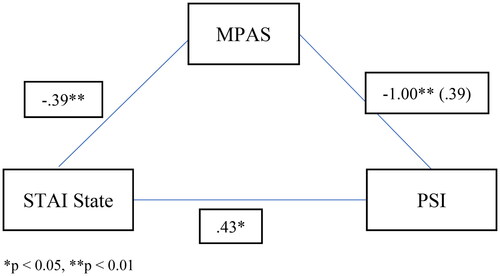

illustrates the mediation analyses testing MPAS as a mediator between STAI State and PSI. The data highlighted a significant total effect of the model tested (R2 = .26; F = 17.50; p < .001), explaining 26% of the PSI variance. There was a significant direct effect of the STAI State (b = .43; SE = .206; t = 2.10; p < .05; 95% CI = .024/.842) on the PSI. MPAS mediated the direct effect. Specifically, the STAI State had a significant indirect effect on PSI through MPAS (b = .39; SE = .113; 95% CI = .178/.625).

Figure 3. Mediation analysis testing the direct and indirect effects of STAI State on PSI mediated by MPAS.

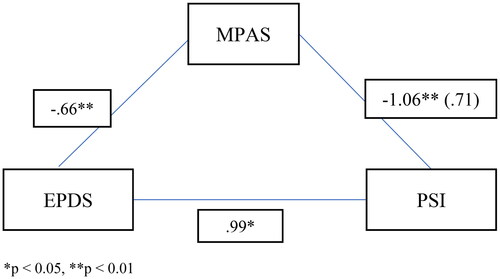

illustrates the mediation analyses testing MPAS as a mediator between STAI Trait and PSI. The model highlighted a significant total effect (R2 = .27; F = 17.43; p < .001), explaining 27% of the PSI variance. There was not a significant direct effect of the STAI Trait (b = .45; SE = .282; t = 1.58; p > .05; 95% CI = −0.115/1.005) on the PSI. Specifically, STAI Trait significantly indirectly affected PSI through MPAS (b = .59; SE = .155; 95% CI = .303/.912).

Discussion

This study examined the relationships between maternal-infant bonding, maternal mental health (depressive and/or anxious symptoms), and parenting stress. We also examined whether maternal-infant bonding mediated the relationship between maternal mental health and parenting stress.

Our findings demonstrated that worst maternal-infant bonding was highly associated with higher levels of maternal state and trait anxiety and parenting stress and moderately associated with greater depressive symptoms. Despite anxiety and depression being prevalent in the postpartum period, with numerous negative effects for the child, the impact of anxiety on the mother’s emotional involvement with the infant has not been studied extensively. We found that anxiety, as a general and long-standing characteristic trait) and as a temporary condition in a specific situation state), and depressive symptoms are associated with difficulties in maternal bonding. Compared to previous studies exploring the link between maternal bonding, depression, and anxiety assessed by STAI, our results agree with those showing how postpartum anxious and depressive symptoms were associated with a worst emotional involvement with the child [Citation9,Citation47–50].

Our findings further show a significant negative association between the mother’s perceived relationship with the baby and her specific difficulties in adjusting to the parenting role. The link between the mothers’ lower levels of bonding and higher parenting stress is in line with the existing literature [Citation11,Citation33,Citation51].

The three mediation models we conducted suggested that mother-to-infant bonding partially mediates the link between maternal mental health (depressive and/or anxious symptoms) and parenting stress. These results indicate that maternal depressive and anxious symptoms and maternal bonding are predictors of parenting stress and that stronger bonding can partially mediate the effect of maternal mental health on parenting stress.

The mediating role played by mothers’ bonding agrees with previous findings of Reck and colleagues [Citation33] and expands these to a community sample with sub-clinical levels of depressive symptomatology and added the important role of anxious symptoms. Our results also agreed with studies that emphasized the role of subclinical depressive symptoms on the developing mother-infant bond during the first months postpartum [Citation15,Citation16] and highlighted the important role of anxiety during the postnatal period [Citation24,Citation25].

Specifically, the mediating effect of maternal bonding was particularly high for trait anxiety, a stable measure of anxiety. This finding partially agrees with a previous study [Citation49] and indicates how experiencing pleasure in caring for the child plays a relevant role in the possible onset of parenting stress, especially in mothers for whom anxiety is a more stable trait and who tend to respond with worry, discomfort, and distress to various situations [Citation52]. This finding is particularly relevant considering previously reported studies on the negative impact of anxiety on mother and child in the postpartum period.

Overall, our data suggest the central role played at the end of the third month of the postpartum period by the mother’s affective responses experienced when caring for the infant. It is clear that depression and anxiety occur frequently in the postpartum period [Citation53]. Even if it is difficult to determine the exact comorbidity, shared and separate risk factors for postpartum depression and anxiety have been detected in various studies [Citation54]. Increasing awareness of the mechanisms that link postpartum anxious and depressive symptoms with parenting stress could provide information for development of preventive interventions and treatment to improve the mental well-being of mothers during the postpartum period.

As indicated by the mediation models, we can speculate that the mother’s emotional response to her infant is one of the mechanisms that plays a relevant role in the relationship between perceived maternal symptoms of anxiety and depression and her perception that the demands of the parental role are greater than the resources she has available to cope with them.

We acknowledge that our study is exploratory in nature and that the findings need to be replicated before firm conclusions can be drawn. The study’s main limitation is the cross-sectional nature of the results, which prevents us from inferring causality regarding the association between the investigated variables. The current study has other limitations. Homogeneous sampling was an issue, with the participants being mainly married mothers with higher socio-economic status and educational attainment. The mothers’ mental health, the bonding process and parenting stress are complex processes in the postpartum period influenced by many factors, such as childbirth experience and the quality of the couple’s relationship as well. Therefore, further replications are needed on different samples that also take into account the possible influence of other factors not accounted for by our models. Furthermore, the variables were assessed with self-report measures and, therefore, potentially at risk of cognitive bias. Mean levels of of anxiety and depressive symptoms were not clinically significant. Although this is a limitation, it supports the theory that even subclinical symptoms can impair maternal bonding and add to parenting stress, underscoring our results’ relevance.In summary, our findings suggest that maternal bonding is one mechanism through which the maternal experience of depressive and anxious symptoms are associated with parenting stress. Considering that there are critical gaps in our knowledge of the complex pathways that likely exist between perceived maternal mental health and parenting stress, our study sheds some light on the variables that mediate this relationship in the postnatal period.

Given the importance of the early mother–child relationship, our findings have important implications for clinical practice by indicating the relevant role of maternal bonding in reducing parenting stress and preventing developmental problems in infants. In the caregiving process, when micro-failures (e.g. “I can’t get him to sleep,” “I can’t calm him down”) are reiterated, the mother does not perceive the reinforcement of the feeling of competence and confidence in her parental function [Citation55]. These experiences, when repeated, expose the mother to the risk of negative mirroring, namely that of a bad child with a bad mother [Citation56]. If supported by future research, our results highlight the need to develop interventions focusing on strengthening or improving the maternal bond experienced toward the infant to reduce parenting stress, thus also limiting the known effects of such stress on child development.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study.

Institutional review board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Bio-Ethical Committee for Research at the University of Perugia (protocol code n. 2019-11 R, date of approval, 6 June 2019).

Acknowledgments

We thank the mothers who participated in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support this study’s findings are available on request from the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Walsh J. Definitions matter: if maternal-fetal relationships are not attachment, what are they? Arch Womens Ment Health. 2010;13(5):449–451. doi:10.1007/s00737-010-0152-8

- Klaus M, Kennell J, Klaus P. Bonding: building the foundation of a secure attachment and independence. Reading (MA): Addison-Wesley; 1995.

- Condon JT, Corkindale CJ. The assessment of parent-to-infant attachment: development of a self-report questionnaire instrument. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 1998;16(1):57–76. doi:10.1080/02646839808404558

- Le Bas GA, Youssef GJ, Macdonald JA, et al. Maternal bonding, negative affect, and infant social-emotional development: a prospective cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2021;281:926–934. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.031

- Nyström K, Öhrling K. Parenthood experiences during the child’s first year: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2004;46(3):319–330. https://doi.org/https://doi: doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.02991.x

- Biaggi A, Hazelgrove K, Waites F, et al. Maternal perceived bonding towards the infant and parenting stress in women at risk of postpartum psychosis with and without a postpartum relapse. J Affect Disord. 2021;294:210–219. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.076

- McNamara J, Townsend ML, Herbert JS. A systemic review of maternal wellbeing and its relationship with maternal fetal attachment and early postpartum bonding. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(7):e0220032. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0220032

- Riva Crugnola C, Ierardi E, Ferro V, et al. Mother-infant emotion regulation at three months: the role of maternal anxiety, depression and parenting stress. Psychopathology. 2016;49(4):285–294. doi:10.1159/000446811

- Figueiredo B, Costa R. Mother’s stress, mood and emotional involvement with the infant: 3 months before and 3 months after childbirth. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009;12(3):143–153. doi:10.1007/s00737-009-0059-4

- Hornstein C, Trautmann-Villalba P, Hohm E, et al. Maternal bond and mother–child interaction in severe postpartum psychiatric disorders: is there a link? Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006;9(5):279–284. doi:10.1007/s00737-006-0148-6

- Lutkiewicz K, Bieleninik Ł, Cieślak M, et al. Maternal-infant bonding and its relationships with maternal depressive symptoms, stress and anxiety in the early postpartum period in a polish sample. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(15):5427. doi:10.3390/ijerph17155427

- Ohara M, Okada T, Kubota C, et al. Relationship between maternal depression and bonding failure: a prospective cohort study of pregnant women. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2017;71(10):733–741. PMID: 28556440. doi:10.1111/pcn.12541

- Ohoka H, Koide T, Goto S, et al. Effects of maternal depressive symptomatology during pregnancy and the postpartum period on infant-mother attachment. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;68(8):631–639. PMID: 24521214. doi:10.1111/pcn.12171

- Tichelman E, Westerneng M, Witteveen AB, et al. Correlates of prenatal and postnatal mother-to-infant bonding quality: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2019;14(9):e0222998. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222998

- Behrendt HF, Konrad K, Goecke TW, et al. Postnatal mother-to-infant attachment in subclinically depressed mothers: dyads at risk? Psychopathology. 2016;49(4):269–276. doi:10.1159/000447597

- Tietz A, Zietlow AL, Reck C. Maternal bonding in mothers with postpartum anxiety disorder: the crucial role of subclinical depressive symptoms and maternal avoidance behaviour. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2014;17(5):433–442. doi:10.1007/s00737-014-0423-x

- Mason ZS, Briggs RD, Silver EJ. Maternal attachment feelings mediate between maternal reports of depression, infant social–emotional development, and parenting stress. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2011;29(4):382–394. doi:10.1080/02646838.2011.629994

- Abidin RR. Parenting stress index: professional manual. 3rd ed. Odessa (FL): Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; 1995.

- Deater-Deckard K. Parenting stress and child adjustment: some old hypothesis and new questions. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 1998;5(3):314–332. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2850.1998.tb00152-x

- Leigh B, Milgrom J. Risk factors for antenatal depression, postnatal depression, and parenting stress. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8(1):24. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-8-24

- Sidor A, Kunz E, Schweyer D, et al. Links between maternal postpartum depressive symptoms, maternal distress, infant gender and sensitivity in a high-risk population. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2011;5(1):7. doi:10.1186/1753-2000-5-7

- Thomason E, Volling BL, Flynn HA, et al. Parenting stress and depressive symptoms in postpartum mothers: bidirectional or unidirectional effects? Infant Behav Dev. 2014;37(3):406–415. doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2014.05.009

- Vismara L, Rollè L, Agostini F, et al. Perinatal parenting stress, anxiety, and depression outcomes in first-time mothers and fathers: a 3- to 6-months postpartum follow-up study. Front Psychol. 2016;7(7):938. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00938

- Davies SM, Silverio SA, Christiansen P, et al. Maternal-infant bonding and perceptions of infant temperament: the mediating role of maternal mental health. J Affect Disord. 2021;282(28):1323–1329. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.023

- Morales-Munoz I, Ashdown-Doel B, Beazley E, et al. Maternal postnatal depression and anxiety and the risk for mental health disorders in adolescent offspring: findings from the avon longitudinal study of parents and children cohort. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2023;57(1):82–92. doi:10.1177/00048674221082519

- Doster A, Wallwiener S, Müller M, et al. Reliability and validity of the german version of the maternal–fetal attachment scale. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2018;297(5):1157–1167. doi:10.1007/s00404-018-4676-x

- Tolja R, Nakić Radoš S, Anđelinović M. The role of maternal mental health, infant temperament, and couple’s relationship quality for mother-infant bonding. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2020;38(4):395–407. doi:10.1080/02646838.2020.1733503

- Huizink AC, Menting B, De Moor MHM, et al. From prenatal anxiety to parenting stress: a longitudinal study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017;20(5):663–672. doi:10.1007/s00737-017-0746-5

- Kaitz M, Maytal H. Interactions between anxious mothers and their infants: an integration of theory and research findings. Infant Ment Health J. 2005;26(6):570–597. doi:10.1002/imhj.20069

- Mulsow M, Caldera YM, Pursley M, et al. Multilevel factors influencing maternal stress during the first three years. J Marriage and Family. 2002;64(4):944–956. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00944-x

- Nath S, Pearson RM, Moran P, et al. The association between prenatal maternal anxiety disorders and postpartum perceived and observed mother-infant relationship quality. J Anxiety Disord. 2019;68:102148. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2019.102148

- Tedgård E, Tedgård U, Råstam M, et al. Parenting stress and its correlates in an infant mental health unit: a cross-sectional study. Nord J Psychiatry. 2020;74(1):30–39. doi:10.1080/08039488

- Reck C, Zietlow AL, Müller M, et al. Perceived parenting stress in the course of postpartum depression: the buffering effect of maternal bonding. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2016;19(3):473–482. doi:10.1007/s00737-015-0590-4

- American Psychological Association. Revision of ethical standard 3.04 of the “Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct” (2002, as amended 2010). Am Psychol. 2016;71(9):900. doi:10.1037/amp0000102

- Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150(6):782–786. doi:10.1192/bjp.150.6.782

- Benvenuti P, Ferrara M, Niccolai C, et al. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: validation for an Italian sample. J Affect Disord. 1999;53(2):137–141. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(98)00102-5

- Gibson J, McKenzie-McHarg K, Shakespeare J, et al. A systematic review of studies validating the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in antepartum and postpartum women. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119(5):350–364. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01363.x

- Spielberger CD. State-trait anxiety inventory: bibliography. 2nd ed. Palo Alto (CA): Consulting Psychologists Press; 1989.

- Pedrabissi L, Santinello M. Verifica della validità dello STAI forma y di Spielberger. Boll Psicol Appl Giunti Organ Spec. 1989;191–192:11–14.

- Scopesi A, Viterbori P, Sponza S, et al. Assessing mother-to-infant attachment: the Italian adaptation of a self-report questionnaire. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2004;22(2):99–109. doi:10.1080/0264683042000205963

- Dunn A, Bird PK, Endacott C, et al. The feasibility of an objective measure of the parent-child relationship in health visiting practice: assessment of the Maternal Postnatal Attachment Scale. Wellcome Open Res. 2022;7:88. doi:10.12688/wellcomeopenres.17552.1

- Guarino A, Di Blasio P, D’Alessio M, et al. Parenting stress index short form: Adattamento italiano. Firenze: Giunti, Organizzazioni Speciali; 2008.

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 26. Armonk (NY): IBM Corp; 2019.

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behav Res. 2007;42(1):185–227. doi:10.1080/00273170701341316

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2004;36(4):717–731. doi:10.3758/bf03206553

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(4):422–445.

- Edhborg M, Nasreen HE, Kabir ZN. Impact of postpartum depressive and anxiety symptoms on mothers’ emotional tie to their infants 2-3 months postpartum: a population-based study from rural Bangladesh. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14(4):307–316. doi:10.1007/s00737-011-0221-7

- Field T. Postnatal anxiety prevalence, predictors and effects on development: a narrative review. Infant Behav Dev. 2018;51:24–32. doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2018.02.005

- Matthies LM, Müller M, Doster A, et al. Maternal-fetal attachment protects against postpartum anxiety: the mediating role of postpartum bonding and partnership satisfaction. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;301(1):107–117. doi:10.1007/s00404-019-05402-7.

- Petri E, Palagini L, Bacci O, et al. Maternal-foetal attachment independently predicts the quality of maternal-infant bonding and post-partum psychopathology. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31(23):3153–3159. doi:10.1080/14767058.2017.1365130

- de Cock ESA, Henrichs J, Vreeswijk CMJM, et al. Continuous feelings of love? The parental bond from pregnancy to toddlerhood. J Fam Psychol. 2016;30(1):125–134. doi:10.1037/fam0000138

- Saviola F, Pappaianni E, Monti A, et al. Trait and state anxiety are mapped differently in the human brain. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):11112. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-68008-z

- Nakić Radoš S, Tadinac M, Herman R. Anxiety during pregnancy and postpartum: course, predictors and comorbidity with postpartum depression. Acta Clin Croat. 2018;57(1):39–51. doi:10.20471/acc.2017.56.04.05

- van der Zee-van den Berg AI, Boere-Boonekamp MM, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CGM, et al. Postpartum depression and anxiety: a community-based study on risk factors before, during and after pregnancy. J Affect Disord. 2021;286(286):158–165. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.062

- Abidin RR. Parenting stress and the utilization of pediatric services. Child Health Care. 1983;11(2):70–73. doi:10.1207/s15326888chc1102_5

- Maestro S. Nascita della genitorialità. SPIWEB, Italian Psychoanalytic Society. 2014. [cited 2022 Dec 12]. https://www.spiweb.it/la-ricerca/ricerca/genitorialita/