Abstract

Postpartum depression (PPD) is classified under postpartum psychiatric disorders and initiates soon after birthing, eliciting neuropsychological and behavioral deficits in mothers and offspring. Globally, PPD is estimated to be associated with 130–190 per 1000 birthing. The severity and incidences of PPD have aggravated in the recent years due to the several unfavorable environmental and geopolitical circumstances. The purpose of this systematic review hence is to explore the contributions of recent circumstances on the pathogenesis and incidence of PPD. The search, selection and retrieval of the articles published during the last three years were systematically performed. The results from the primary studies indicate that unfavorable contemporary socio-geopolitical and environmental circumstances (e.g. Covid-19 pandemic, political conflicts/wars, and natural calamities; such as floods and earthquakes) detrimentally affect PPD etiology. A combination of socio-economic and psychological factors, including perceived lack of support and anxiousness about the future may contribute to drastic aggravation of PPD incidences. Finally, we outline some of the potential treatment regimens (e.g. inter-personal psycho- and art-based therapies) that may prove to be effective in amelioration of PPD-linked symptoms in birthing women, either alone or in complementation with traditional pharmacological interventions. We propose these psychological and art-based intervention strategies may beneficially counteract the negative influences of the unfortunate recent events across multiple cultures, societies and geographical regions.

Introduction

Depression is a mental condition and is estimated to be the third leading cause of disability worldwide. It induces huge socioeconomic and psychological burdens on the subjects and the care-givers. The spectrum of depressive symptoms includes devitalized mood, reduced interest in daily activities, weight loss, insomnia, fatigue, feeling of worthlessness, reduced concentration, and suicidal thoughts, among others. Age and gender are two main factors that influence the development of depression. Thus, women are more prone to depression than men, and susceptibility to depressive behavior increases with age [Citation1]. Depression may be temporal in certain cases, postpartum depression (PPD) being a notable example. However, it is a significant issue as its prevalence around the globe is estimated to be between 150–220 per thousand birthing. Indeed, Wang et al. have reported a global incidence of PPD at 17.22% (16–18.51%; 95% CI); however, its frequency is imperatively determined by the economic and developmental status of the geographical area [Citation2].

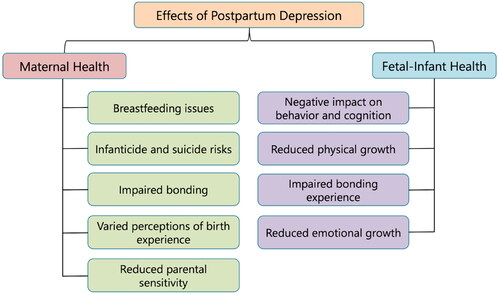

Contrary to popular beliefs, pregnancy is only associated not with positive emotions like happiness, optimistic anticipation and satiation. It also induces an exceptional toll on the female’s hormonal, physical, emotional, and psychological abilities. After birthing, women may experience a mix of emotions such as sadness and mood swings [Citation3]. Clinically, PPD is a depressive condition which occurs particularly in new mothers and is associated with symptoms such as mood swings, heightened irritation/anger, uncontrolled crying spells, fatigue, weight loss/gain and insomnia. Generally, PPD is identified when these symptoms persist for at least 2 weeks [Citation4]. The onset of PPD is within the first 4 weeks after birthing and depending on the severity of the conditions and the persistence of the underlying etiological factors, it can extend to 3–12 months, and even beyond [Citation5]. Interestingly, PPD impacts not only the mother’s health but also has significant implications for offspring. PPD in mothers is often associated with anthropometric changes in their children, such as weight loss, reduced overall physical and social health, and cognitive and emotional problems [Citation6]. Particularly, difficulty in bonding with the offspring as a consequence of PPD may result in prolonged detrimental effects on the child’s neurological and behavioral outcomes, such as delay in language development [Citation7]. delineates some of the consequences of PPD on maternal and infant health. Of note, while females are more prone to PPD, males (fathers) may also experience it. They may be 2.5 times more likely to develop PPD if their partners are also suffering from it [Citation8].

The trigger(s) for PPD have multimodal origins; including physical, hormonal, psychological and emotional stress the female body is under during the gestation period. PPD needs to be identified and treated to prevent adverse effects on parental abilities and child development. The major aim of the present review is to critically discuss the impact of current environmental and socio-economic conditions in the etiology of PPD in the global perspective. In particular, the influences of recent events; viz. Covid-19 pandemic, on-going geopolitical conflicts and natural calamities such as earthquakes and floods have been evaluated. While most previous studies have focused on individualized risk factors (e.g. economic status, domestic and obstetric violence, access to healthcare, etc.), the present study combines three scenarios (pandemics, wars/military conflicts and natural calamities) representing unexpected, generally transient events which affect the entire population of the particular area; for assessment of their influences on PPD etiology. Finally, the authors conclude with a brief overview of novel and potentially effective treatment strategies against PPD.

This systematic review highlights the effects of Covid-19 outbreak, war conflicts, and natural disasters on PPD prevalence and etiopathology. This has been done by taking into account several studies that have been conducted across the world. The general finding of these primary studies has been that these events result in increased prevalence and aggravated phenotype of PPD, and this associativity is based upon several demographic, psychological, socio-economic and physical factors. Furthermore, treatment strategies which may be alternatively used to counteract the side-effects caused by traditional methods such as antidepressant-based pharmacotherapy have been discussed.

Methodology

Focused research objectives

The major goals of this review article were developed based on the original research published on the themes of PPD etiology, pathogenesis, and prevalence in various countries of the world and their incidences in current scenarios of recently resolved COVID-19 pandemic, military conflicts in different geographical regions and natural disasters such as floods and earthquakes, in otherwise peaceful regions, during the last three years (Dec 2019–March 2023).

The specific objectives were as follows: (i) to evaluate the prevalence of PPD in different locations during the peak of Covid-19 infections and the associated factors, (ii) to assess the influences of military conflicts on PPD in multiple geopolitical regions, and (iii) to analyze the effects of natural calamities such as floods and earthquakes on PPD pathogenesis.

Lastly, evidences for the effectiveness of two novel therapeutic regimens; psychotherapy and art-based therapy are discussed.

The study was performed in accordance with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ) and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Supplementary Information files). COREQ is essentially a checklist of items that should be included in reports of qualitative research whereas PRISMA is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Research study search

The identification of pertinent research articles dealing with PPD etiology, pathogenesis, and prevalence in various countries around the world, as well as their incidence in current scenarios of recently resolved COVID-19 pandemic, geopolitical conflicts and natural disasters, was accomplished using a methodically designed, well-structured approach for the literature/study search. A variety of keyword combinations were employed for the literature search, which used the most relevant online scholarly web-databases such PubMed (Medline), Google Scholar, Web of Science, and EMBASE. The key words used were {(“Postpartum depression” OR “PPD” OR “postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder” OR “PP-PTSD” OR “postnatal depression”) AND (“Etiology” OR “Covid-19” OR “Geopolitical conflicts” OR “wars” OR “natural disasters” OR “earthquakes” OR “floods” etc.)}. Few more search keywords like countries experiencing geo-political wars/conflicts in the current times (i.e. Syria, Myanmar, Russia-Ukraine, Yemen, Mexican drug war, Boko haram insurgency), “psychotherapy”, “art therapy” and “antidepressants” were used in combination with PPD.

Studies discussing the etiology of PPD in relation to the recent events of Covid-19 pandemic, military conflicts and natural disasters, and published in the last three years (Dec 2019–March 2023) were considered for inclusion in the present study. Further, the obtained studies were chosen after evaluation of their titles and abstracts, which were verified for relevance with regards to the specific objectives. In addition to the aforementioned online web search, the references listed in the retrieved articles were carefully examined to ascertain if there were any relevant research studies that might have been overlooked during the initial web search. Literature retrieved in this manner from the different databases revealed the various factors associated with the etiology, incidence and pathogenesis of PPD.

Inclusion & exclusion criteria

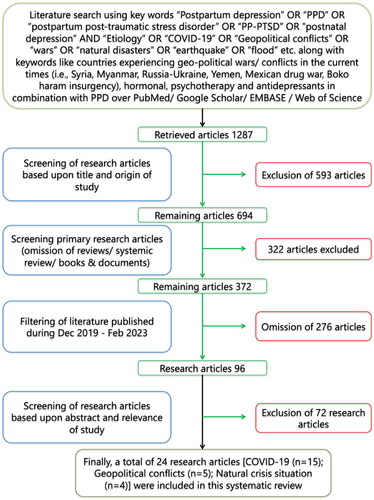

Only original research articles that were published in various peer-reviewed journals and indexed in reputable databases were included in the list of chosen articles. Strict criteria were followed for including/excluding the individual papers in order to draw the appropriate conclusions for this critical study. Pre-set inclusion-exclusion criteria were employed for recruiting the primary research articles for the present systematic review. summarizes the retrieval and selection methodology for the relevant studies for this systematic review. All selected studies included in this study were original research articles dealing with PPD etiology, pathogenesis and its incidence in current global scenarios of the recently resolved Covid-19 pandemic, military conflicts and natural disasters, such as earthquakes and floods. Further, only studies published during the last three years (December 2019 to March 2023) were included. Exclusion criteria included unavailability of the sample size and publication of the study in a language other than English.

Literature search strategy

The methodological strategy for literature search was as follows. Two investigators (viz. LP and SS) individualistically inspected the “titles” and the “abstracts” of the articles retrieved from the sequential search performed on the different scholarly online databases. Full-texts of the retrieved studies were also examined to ratify their relevance for the specific objectives of the study. This was followed by a systematic and independent appraisal of the suitability of the retrieved articles by two other investigators (AA and SSR) by applying the pre-set criteria of study inclusion/exclusion. Concurrently, the second and third investigators (SS and AA) independently endorsed the germaneness of the screened articles for the present study by randomly, but thoroughly examining 10% of the full-text articles. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study selection were fully followed by the investigators while selecting the relevant articles. Following the finalization of study-set, investigators (DMM and FA) summarized the pertinent data from the screened articles. This step was further cross-checked by the investigators (DKY and FA) independently by evaluating all the data from the included studies. For any type of conflict occurred between the investigators during the study selection process, especially related to the data retrieval were resolved with logical debate in the presence of appointed arbitrator (SH).

Results

Screening of studies and data abstraction

The online search conducted over PubMed (Medline), Google Scholar, Web of Science, and EMBASE databases resulted in retrieval of 1287 articles during the primary screening step. Further, downsizing of the screened articles for pertinent studies of PPD etiology, pathogenesis and its incidence in relation to the contemporary events of Covid-19 pandemic, regional military conflicts and natural crises resulted in selection of 694 articles when time duration of last three years (2019–2023) was applied. Further screening was based upon the screened articles’ titles, abstracts and their full-texts following the pre-established inclusion and exclusion criteria. The data fetched from the included studies were summarized according to the: year of publication and the country of origin of the study, sample size, factors affecting PPD pathogenesis and the first author name. A final set of 24 original research studies were selected for discussion in this study along with other relevant studies discussing the novel therapeutic strategies against PPD.

Quality assessment and data extraction

The designated investigators (LP, SS, AA, SSR, DMM and FA) independently carried out the quality evaluation of the data abstracted from all the selected studies based appropriateness of several study attributes; such as sufficiency of subject number, suitability of assessment method for depression-like symptoms, and presence of critical analyses and inferences regarding the factors aggravating PPD symptoms/incidences. The exactness of the abstracted data was cross-checked by filling a data-collection-form prepared according to the pre-established study selection criteria. The data collected from the included studies were the year of publication and the country of origin of the study, sample size, major findings and the first author name, along with the citation. In the event of any conflict, a final consensus was achieved in the presence of adjudicators (DKY and SH) by open dialogue.

Selection of studies

The significance of PPD etiology and prevalence in the current global scenario of pandemics, wars and natural disasters have been taken into consideration in order to streamline the study. All the relevant data abstracted from 24 primary-original research articles, which were included for this study have been abridged in . The study selection (pre-set criteria of study inclusion/exclusion) process and iterative steps applied in this study are shown as PRISMA flow diagram ().

Table 1. Research studies evaluating the impact of Covid-19 pandemic on PPD pathogeneses (2019–2023).

Table 2. Research studies evaluating the impact of geopolitical conflicts on PPD pathogeneses (2019–2023).

Table 3. Research studies evaluating the impact of natural calamities on PPD pathogeneses (2019–2023).

Etiological factors affecting PPD pathogenesis

PPD has a multifaceted etiology and several factors are known to increase its risk. For example, studies indicate that Asian (Middle-eastern, Central Asian, Indian subcontinent and far Eastern) women are at a higher risk of PPD, possibly to the relatively increased exposure to unfavorable socio-economic factors [Citation33]. Below we discuss some of the etiological factors for the increased susceptibility for the development of PPD. We also outline results from studies which have attempted to evaluate the effects of recent events (e.g. Covid-19 pandemic, wars, and natural disasters) on the development of PPD.

Environmental factors

Studies indicate that several unfavorable socio-economic factors significantly increase the risk for PPD pathogenesis. These include poverty and lack of social support, financial and marital stress, obesity, exposure to adverse life events such as domestic violence, unplanned pregnancy, negative anticipation and anxiety of physical and mental strains of childbirth, and inability to form efficacious mother-infant bonding [Citation3]. Depressed mothers may elicit 36% probability of harming the infant and 34% chances of having a weak attachment toward the offspring [Citation34]. Postnatal women who had little social support were nearly four times more likely to develop depression than mothers who had adequate social support, which functions as a protective factor against depression [Citation4]. Similarly, mothers with a history of subjugation to domestic violence and unwanted pregnancies were nearly three times as likely to be depressed as their counterparts [Citation35]. Unplanned pregnancy may also enhance the likelihood of mistreatment of the birthing woman, thereby increasing the risk of mental stress and anxiety. For example, a clinical study conducted in a sample of new mothers based in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Oman identified several factors that may be associated with PPD development, one of which was unplanned pregnancy. In this questionnaire-based study, several variables were considered; age, weight, gender of the offspring, delivery type, diet during gestation, physical state, financial constraints, family problem, and nature (planned or unplanned) of pregnancy. These variables were then used for evaluation of any links with PDD pathogenesis. Among all the environmental variables, un-satisfaction with the physical state and unplanned pregnancies posed the higher association with PPD-like symptoms [Citation36]. Similar implications were also derived from the data collected from a panel study on Korean children from 2008–2010. The results indicated that a high percentage of birthing women with unplanned pregnancies experienced PPD [Citation37]. Is should be noted that while unwanted pregnancy may lead to poor mother-infant relations, the lack of attachment may not continue for an extended time period. Unintended pregnancy and the sudden news of a child might initially seem to be a burden but this anxious state may diminish over time with increasing intimacy between the mother and the infant as a result breast-feeding. Nevertheless, unwanted pregnancy may be a significant factor in the etiology of PPD [Citation38].

The inability of the birthing woman to form positive bonding with the infant is another environmental factor that is related to the increase in the incidences of PPD. This in turn might be due to mental stress caused by a plethora of external and environmental factors, such as socio-economic and family issues. In concurrence, rodent models of early-life neuropsychological stress which mirror poor infant-mother bonding (such as repeated maternal separation [Citation39]) indicate a strong relationship between developmental stress and trauma and increased risk of neuropsychological disorders like anxiety and depression, schizophrenia, and substance abuse later in the life [Citation40]. In addition to the deleterious and irreversible effects in the offspring, such animal experiments have also shown that inability to form mother-offspring bonding may result in higher risk of PPD-like symptoms [Citation41].

Similarly, experimental models of high fat diet have elicited a strong association of obesity with the development of PPD [Citation42]. Further, in addition to diet-mediated weight gain, other physiological changes in the birthing woman’s body such as abnormal vaginal and breast discharges, breast engorgement, discomfort in perineal area and constipation as well as the surgery-linked discomfort (in case of Cesarean delivery) have been implicated in the promotion of PPD-like behavioral phenotype [Citation3]. Interestingly, altered eating behavior in some gestating women may significantly increase fetal weight, increasing the likelihood of Cesarean delivery. This, in turn adds another facet linking diet to the pathogenesis of PPD in mothers [Citation8]. Moreover, birthing women undergoing Cesarean delivery often experience post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and PP-PTSD after the surgery. These depressive symptoms are elicited particularly in birthing women who experience Cesarean delivery for the very first time. In addition, Cesarean delivery is often associated with several health concerns like blood clot and hemorrhage and may be a major contributor to maternal morbidity [Citation43]. All these factors associated with Cesarean delivery (and diet) are critically important for increased risk for the development of PPD and PP-PTSD.

Finally, birthing women with a history of depression, stress and anxiety have exceptionally elevated chances of suffering from PPD [Citation35]. Such clinical subjects are often diagnosed with severely altered endocrinological responses during and after childbirth. These abnormal biochemical changes may alter neurotransmitter signaling, particularly serotonergic signaling in the brain, significantly enhancing the risks of PPD pathogenesis [Citation34].

Contemporary environmental and geopolitical conditions influencing etiology of PPD

Several contemporary environmental and geopolitical events have been implicated in the increased prevalence of PPD. For the purpose of this review, we have chosen three highly relevant factors; Covid-19 pandemic, geopolitical conflicts/wars and natural disasters. Although not directly related, these three conditions share interestingly commonalities. First, they are largely unexpected, and very intense in their consequences. Second, these situations affect the entire population in particular geopolitical regions. Third, they are transient in nature per se, although their detrimental effects on psychological, social and economic aspects may be longer-lasting and predominantly irreversible. In comparison, most studies have evaluated the influences of factors which are generally limited to few individuals/families or sections of the geographically-limited populations, and are longer-lasting. Examples of these include economic status, domestic and obstetric violence, etc.

Covid-19 pandemic

The recent outbreak of Covid-19 had long-lasting effects on psychological attributes in the survivors [Citation44]. Increased anxiety among child-bearing women has been evidenced by several groups. There were several considerations in this regard. First, the birthing females were anxious about the outcome of the SARS-CoV-2 infection and the consequences on their and the progeny’s health. Second, deleterious socioeconomic conditions, particularly in third-world countries lacking efficient social/medical support systems procedures was strongly linked with the higher incidences of PPD. In fact, social isolation which was the defining feature of the anti-Covid 19 strategies implemented in almost all countries may have resulted in significant incidences of relationship strain, lack of prenatal care, and interruptions in routine offline health checkups; increasing the likelihood of PPD-like behavior in pregnant women. On the other hand, Covid-19 infection may have resulted in avoidance of frequent routine visits to hospitals and care-givers in pre- and post-partum women. Indeed, new mothers preferred to be discharged from the hospitals and clinics immediately after delivery during the Covid-19 pandemic. Third, lack of physical activity during the Covid-19 pandemic also contributed to the increase in the score of birthing women in the Edinburg postnatal depression scale (EPDS). Fourth, the fear of getting infected was also a prime reason of developing PPD-like symptoms of anxiety and depression in non-infected birthing women. Indeed, all these factors contributed to the increased prevalence of PPD-associated symptoms during the Covid-19 pandemic to at least 34% more than during the non-pandemic period. Furthermore, incidence of PPD among birthing women was significantly higher in low-income third world countries in comparison to high-income countries [Citation45].

In an online EPDS questionnaire-based study conducted in the United States to evaluate the effects of Covid-19 pandemic on PPD-associated behavioral alterations in 670 postpartum women, 21.8% of the subjects were found to suffer from major depression symptoms and 7.6% were inclined toward self-harming, while the fear of contracting the infection increased the odds by 71% to be positive for PPD. Furthermore, the study indicated a possible link between the inability of breast-feeding and the chances of developing PPD [Citation46]. In a case-control study conducted in Italy, Zanardo and colleagues found a strong association of social isolation induced by quarantine measures and anxiety regarding contracting Covid-19 with postpartum depressive behavior, as assessed by EPDS [Citation9]. In concurrence, higher severity of PPD-like symptoms was reported in American women who birthed during the early phases of the pandemic [Citation18]. In contrast, Overbeck et al. reported no significant anxiety and depression like symptoms in postpartum women during the different periods of Covid-19 pandemic [Citation23].

The incidence of PPD was found to be as high as 56.9% in a sample of 209 postpartum subjects in China during the Covid-19 pandemic period of May to July 2020. Moreover, middle-aged subjects, birthing women with elevated perceived stress as well as women with a history of abortion were found to be at elevated risks for PPD [Citation10]. PPD symptoms and long-term inability to form healthy mother-infant bonding were apparent in American women during the pandemic possibly due to Covid-19-related psychological distress, among other factors such as previous exposure to depressive and stressful episodes [Citation11]. In a study involving 305 postpartum women from Cordoba, Argentina, 37% of the women were diagnosed with PPD, as measured by the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale questionnaire. The major determinant was found to be social isolation induced by the strict confinement measures enforced during the pandemic. Other factors which influenced PPD in these women were age and provision/absence of social support systems. In addition, Covid-19-related isolation measures resulted in deterioration of other mental health attributes, including sleep regulation, memory and concentration [Citation12]. Similarly, in 4–12 week postpartum Mexican women, social isolation during Covid-19 pandemic was associated with significantly higher incidences of postpartum depression, anxiety and perceived stress, compared to the controls [Citation13]. In a study carried out in Iranian pregnant and breast-feeding women during the pandemic period of May-June 2020, significantly higher prevalence of depressive and anxiety-like symptoms (measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HADS) were reported, compared to the general female population [Citation14]. In India, during the period of August 2020 to February 2021, 204 Covid-19 postpartum suspects (in hospital isolation wards, and enforced with quarantine measures) were found to be at tremendously increased risk of developing PPD symptoms, compared to postpartum women (n = 204) from non-suspect hospital zones [Citation15]. Similar effects of Covid-19 pandemic on PPD manifestation were reported in women from Israel, surprisingly with little detrimental effects on mother-infant bonding [Citation22]. In agreement, fear of hospital visits, job-insecurities, anxiety regarding social isolation were reported to the major factors underlying increased PPD pathogenesis during the various waves of the Covid-19 pandemic in Romania [Citation19]. Anxiety with regards to lack of hospital beds and loss of partner, family or social support possibly were also shown to underlie the manifestation of depressive symptoms in postpartum Brazilian women during Covid-19 pandemic [Citation20]. In Kenya, Covid-19 pandemic may have increased the risk of developing depressive symptoms in postpartum women by 2.5 times. In addition, economic vulnerabilities among birthing women; such as food insecurities, inabilities to pay for hospital postnatal visits and PPE, were reported to severely aggravate the problem [Citation21].

In contrast to these studies, no obvious changes in PPD prevalence were observed in postpartum women in Yokohama, Japan during the pre-pandemic (March-June 2019) and pandemic (March-June 2020) periods, after adjusting for variables such as history of psychiatric disorders, pregnancy, and delivery outcomes, preterm delivery, and maternal postpartum complications [Citation16]. Surprisingly, in spite of the association of the Covid-19 pandemic with increased incidence of obstetric violence, no significant changes in the prevalence of PPD- and PTSD-like symptoms were reported in Russian women who birthed before vs. during the pandemic [Citation17]. The authors attributed this to similarities of the incidences of depression and obstetric violence, which were the major correlates for PPD development, before and during the pandemic. Further, they indicated that presence of efficient medical child birth facilities, and prioritization of health care provision for birthing women during the pandemic was also a significant contribution. summarizes the results from the selected studies evaluating the effects of Covid-19 on PPD in birthing women across the globe.

Geopolitical conflicts

In the recent decades, there has been a surge in political conflicts and wars across the globe. Traumatic events during wars have significantly increased the prevalence of PPD and PP-PSTD among birthing women in the conflict zone. This has culminated into the emergence of various unfavorable risk factors for PPD; such as displacement and migration [Citation47]. For instance, the on-going Syrian civil war has resulted in the displacement of millions of civilians since the start of the war. A detailed study published in 2018 was conducted to understand the prevalence and risk factors for PPD in a sample size of 1105 displaced Syrian women. Results from this descriptive cross-sectional EPDS questionnaire-based study indicated that approximately half of the respondents elicited probable depressive symptoms. Among the etiological factors tested, lack of family support appeared to be a common cause for PPD. Conversely, subjects receiving antenatal care were observed to have 50% less chances of developing PPD. Other socio-demographic factors which were found to be linked with PPD-linked symptoms included birthing age of the subjects, financial status, state of literacy, gender of the infant, appropriate access to health care services, and complications during previous pregnancies [Citation48]. Interestingly, Syrian women have been found to elicit much greater frequency of PPD prevalence in comparison to other Arab and non-Arab countries. Indeed, war-induced displacement and perceived exposure to multiple stressors have turned out to be the major sources of depression and anxiety among postpartum Syrian women [Citation24].

A study conducted by Isosavi et al. analyzed the risk factors for caregiving representations, and depressive- and PTSD-like symptoms in Palestinian mothers exposed to pre- and post-natal traumatic war events. Emotional availability as a measure of mother-infant interactions, scored using a questionnaire, was observed to be significantly impacted by depression levels, postnatal PTSD, offspring gender, financial difficulties and age at the time of birthing [Citation25]. In concurrence, a study by Yoneda et al. from the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) evaluated the risk factors for PPD in Palestinian refugees based in Amman, Jordan. Out of the sample size of 251 birthing women, a whopping 49% were estimated to be manifesting PPD-like symptoms. The major variables associated with this high frequency of PPD were found to be exposure to stressful life events and low levels of social support [Citation26]. Similar findings of significantly higher risk of developing peri- and postpartum depression have been reported in women inhabiting conflicts regions in Pakistan compared to the general population [Citation49]. In Xinjiang Uyghur autonomous region which has seen multiple episodes of political conflicts and repressions, there has been a constant rise in the prevalence of PPD from 2018 to 2021 [Citation28]. Lastly, a study conducted for identification of risk factors for the development of depression, as assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnosis of DSM-IV Disorders, in perinatal and postpartum stages in refugee and migrant women at the Thai-Myanmar border implicated several variables; including age of the mother, exposure to interpersonal violence, history of exposure to stressful, traumatic and depressive events, and low economic and social support [Citation27]. Unfortunately, several other regions have seen tremendous political instability and conflicts in the recent years. However, not many studies have covered the impact of geopolitical tensions in birthing women of these regions (e.g. Ukraine, Afghanistan, and Yemen). It will be relevant for researchers to evaluate the prevalence of PPD and PP-PTSD in women of these regions which have suffered wars and conflicts in the recent years.

Interestingly, women war veterans may also elicit higher incidence of mental health issues, including PPD and PP-PTSD compared to the women from the general population [Citation50]. Moreover, military deployment of spouses has also been associated with the development of depressive symptoms in birthing women [Citation51]. Other studies have also elicited the direct and/or indirect impact of political conflicts in the development of PPD- and PP-PTSD-like symptoms in birthing women (reviewed by Chrzan-Dętkoś et al. [Citation52]). For example, a major issue has been significantly heightened risk of developing PPD in immigrant women compared to nonimmigrant women [Citation47, Citation53], with a number of contributing risk factors; including diminished levels of marital and/or social support, poor social and cultural adjustment in the destination country/region and low economic stability.

Natural calamities

Natural calamities and the associated visualization of death of family members, physical trauma and destruction of property take a heavy toll on mental health. Disruptions in social interactions/networks and loss of safety and security perception induce psychological and mental alterations [Citation54]. These detrimental effects are often temporary, but can be persistent in individuals. Floods and earthquakes are among the major natural disasters that affect large communities which may be at relative peace, as opposed to communities exposed to wars. Hence for this section, we focused on the studies which evaluated the effects of floods and earthquakes on PPD pathogenesis in females not exposed to military violence. In this regard, studies have characterized the impacts of massive flood situations in Calgary (Canada, 2013 [Citation29]), and in Queensland (Australia, 2011 [Citation30]), and Iowa (USA, 2008 [Citation55]) on postpartum anxiety and depression. Interestingly, both the Queensland and Iowa flood studies indicated a significant association of peritarumatic distress for post-disaster anxiety and depression in birthing women [Citation30, Citation55]. However, the Calgary flood study did not report significant differences in PPD and anxiety in flood victims, although they elicited small increases in gestational hypertension [Citation29]. With regards to earthquakes, studies in Japan indicated significant association of traumatic exposures during the Great East Japan Earthquake (Great Tōhoku Earthquake [Citation32]) and the Fukushima earthquake [Citation31] with the appearance of PPD-like symptoms in women.

Treatment regimens

The first form of approachable traditional treatment includes anti-depressants. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) are the first choice for the treatment of mood disorders, including depression. SSRIs, paroxetine, fluoxetine, and sertraline are all used for PPD treatment. A related class of anti-depressants is the serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). These work by blocking the re-uptake of neurotransmitters, serotonin and norepinephrine, and thereby enhance their signaling at the synapses [Citation56]. Another pharmacotherapeutic agent recommended for PPD is the rapidly acting antidepressant brexanolone [Citation57], although clinical studies have questioned its side-effects and safety.

Inter-personal psychotherapy (IPT)

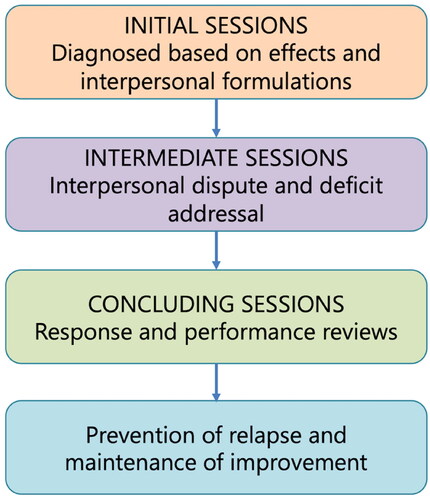

Depressive disorders often cause poor communication thereby leading to poor relations among patients. Inter-personal psychotherapy (IPT; ) is a suitable treatment regimen that brings biological, psychological, and social factors together helping the new mothers deal with stress. This psycho-social model may help to reduce the risk of developing PPD-like symptoms in birthing women. Social support can be the initial stage of treatment, with interactive sessions being held weekly. With time and upon confirmation of the beneficial effects, these can be reduced to once in a fortnight. Furthermore, cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) and psychodynamic therapy may be included for further efficiency of the IPT regimen [Citation58]. Randomized controlled trials have indicated that such IPT sessions result in significant reduction in the depressive state of new mother and enhance their social interactions. Recent strategies of cognitive-behavioral counseling of expectant mothers, their spouses and/or close relatives have been shown to be beneficial and may represent an effective preventive methodology against PPD [Citation59,Citation60]. Online or offline structured educational sessions in the supervision of licensed and experienced psychologists may be implemented in primary and secondary care-giving institutions so as to reduce the risk of the development of PDD in birthing women. Further, IPT is easy to implement, accessible and affordable for to a larger population.

Art-therapy (at)

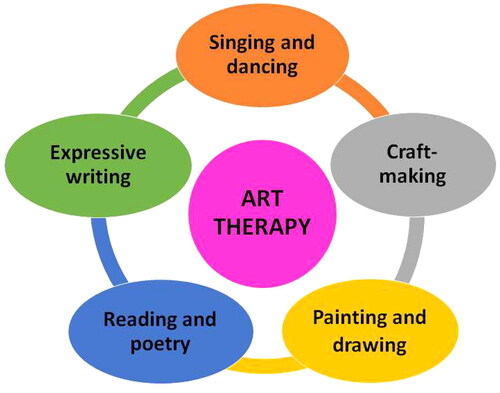

Novel alternative methods, such as art-therapy for amelioration of mental health deficits have been proposed for some time now. PPD and dysfunctional mother-infant bonding are no exceptions to this (). Recent studies have provided irrefutable evidences in favor of the effectiveness of art-based postnatal mother-infant interventions in preventing and even reversing the PPD-associated detrimental changes in birthing women and their offspring [Citation61,Citation62]. Attending and participating in activities such as singing and dancing [Citation63–65], craft-making [Citation66,Citation67], painting and drawing [Citation68], and expressive writing [Citation69] for instance, have been shown to be associated with beneficial alterations in maternal and infant psychosocial outcomes. AT can be combined with psychotherapy and IPT strategies for significantly enhanced rescue of depressive symptoms in postpartum women, as evidenced by a study carried out amongst Palestinian Arab population residing in Israel [Citation66]. Similarly, protocols for combinatorial cognitive and art therapy therapies may be designed for implementation in perinatal and postpartum women with depressive and anxious phenotypes [Citation70,Citation71].

Discussion

The study of PPD currently uses multiple analytical parameters to measure the presence and severity of several aspects of depressive behavior among birthing women. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) scale is one of the most widely used questionnaires in clinics for both research and diagnostic purposes. Other forms of diagnostic online interviews may be used in complementation for a more robust assessment of the PPD symptoms. Many of these techniques provide a differential approach to examining postpartum depression. Studies are also warranted for the development of efficacious and standardized tools for the diagnosis of PPD-associated behavioral phenotype for birthing women, both during the pre- and postpartum periods. A standard scale will allow construction of a cutoff value for ensuring validity and reliability of the diagnosis. In addition, it is relevant to provide the birthing women with early detection of prenatal depressive symptoms with appropriate healthcare and social safety supports, depending on the exact nature of the stressor(s). In particular, alternative preventive strategies should be employed in the place of techniques such as the electroconvulsive therapy which is used in cases of severe PPD, but is often marred with side effects such as memory loss. Focal brain stimulation strategies such as transcranial magnetic or direct current stimulation should be preferred. Along similar lines, advances in our understanding of the etiology and risk and pathogenic factors will lead to the development of promising new treatments for PPD [Citation4].

Although there has been appreciable progress in the last few years, several aspects of PPD and its prevention/amelioration have remained obscure. Given that depressive behavior in general and PPD in particular, is potentially a life-threatening condition, it is obvious that further research must be carried out to understand the patho-physiology of the condition and device efficient diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Recent strategies of cognitive-behavioral counseling of expectant mothers, their spouses and/or close relatives have been shown to be beneficial and may represent an effective preventive methodology against PPD [Citation59,Citation60]. Online or offline structured educational sessions in the supervision of licensed and experienced psychologists may be implemented in primary and secondary care-giving institutions so as to reduce the risk of the development of PDD in birthing women. In addition, combinatorial cognitive and art therapy programs may be a way forward for amelioration of PPD and enhancement of the mother-infant bonding.

The major strength of our systematic review is that this is the first-of-its kind study which highlights the effect of formidable but transient environmental factors which affect whole communities on PPD etiology. In contrast, previous studies have discussed the influences of longer-lasting factors which undermine few individuals/families and small sections of the society in a particular geopolitical area, examples of which include socio-economic parameters, psychological dysfunctions associated with domestic abuses, and so on. The three parameters chosen here are pandemics (with the recently resolved Covid-19 crisis serving as an example), natural calamities (earthquakes and floods) and wars; all of which are very harsh on the population as a whole, but are nevertheless generally regarded as transient; even though they are expected to have irreparable consequences on multiple socio-psychological and economic aspects. There are some limitations of study; first, most primary studies included in this systematic review have not clinically evaluated the therapeutic aspects, although some of them have theoretically discussed these. In order words, while the different factors relating to aggravated PPD phenotype have been more-or-less thoroughly analyzed, measures to control these have not been evaluated. This means that although we have proposed IPT and AT as potential therapeutic regimens against PPD, their effectiveness under clinical settings remains to be evaluated in the three current environmental and geopolitical scenarios discussed in this review. Second, because of our inability to comprehend other languages, we have only selected primary studies published in the English language. While studies in other languages are in no way or form, inferior to those published in English, this is a limitation on the part of the authors, which in our experience is difficult to rectify even using the best of the language translation platforms.

Conclusion

Given that depressive behavior in general and PPD in particular, is potentially a life-threatening condition, it is obvious that further research must be carried out to understand the patho-physiology of the condition and device efficient diagnostic and treatment strategies. The number of studies evaluating the molecular mechanisms of and therapeutic strategies against neuropsychiatric disorders has increased exponentially during the last few years. Nevertheless, research evaluating the etiology, pathogenic mechanisms and ameliorative strategies against PPD have somewhat remained retarded. The present review first highlights the etiology and the risk factors associated with the development of PPD in birthing females. Particular emphasis is given to effects of the prevalent geopolitical, and socio-economic conditions and environmental factors including Covid-19 pandemic and political conflicts on PPD and PP-PTSD risk. The hope is that advances in our understanding of the etiology and the associated risk factors will lead to the development of promising new treatment regimens against PPD. Hence, we briefly discuss the preventive and ameliorative strategies against PPD currently in use in the clinical practice. Several novel facets of the art-based treatment regimens appear to be highly effective in amelioration of postpartum anxiety and depression, particularly in closely-linked subsets of newly birthed mothers exposed to detrimental environmental situations of wars, forced migration, floods, earthquakes, socio-economic hardships, pandemics, etc. Moreover, combinatorial approaches relying on both art and cognitive therapies have immense potential in treatment of PPD and in enhancement of mother-infant relationships. Nevertheless, studies must be directed to first confirm and establish these therapeutic regimens in multiple populations of new mothers of varied ethnicities, geopolitical origins and economic status. The hope is that this systematic study will serve as a basis for generating more interest among scientists of different fields for conducting further research on PPD and ultimately, comprehending and preventing the factors linked to the pathogenesis of PPD.

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data: LP, SS, AA, SSR, DMM, SH, MT, FA; involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content: LP, SS, AA, SSR, DMM, SH, MT, FA; given final approval of the version to be published. Each author should have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content: LP, SS, AA, SSR, DMM, SH, MT, FA; Agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: LP, SS, AA, SSR, DMM, SH, MT, FA.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through the Project Number ISP23-101.

Submission declaration and verification

This work has not been previously published and it is not under consideration for publication elsewhere, that its publication is approved by all authors and tacitly or explicitly by the responsible authorities where the work was carried out, and that, if accepted, it will not be published elsewhere in the same form, in English or in any other language, including electronically without the written consent of the copyright-holder.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (36.2 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Park LT, Zarate CA. Depression in the primary care setting. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(6):1–17. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1712493

- Wang Z, Liu J, Shuai H, et al. Mapping global prevalence of depression among postpartum women. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):543. doi:10.1038/s41398-021-01663-6

- O’Hara MW, McCabe JE. Postpartum depression: current status and future directions. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9(1):379–407. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185612

- Stewart DE, Vigod SN. Postpartum depression: pathophysiology, treatment, and emerging therapeutics. Annu Rev Med. 2019;70(1):183–196. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-041217-011106

- Ko JY, Rockhill KM, Tong VT, et al. Trends in postpartum depressive symptoms—27 states, 2004, 2008, and 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(6):153–158. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6606a1

- Slomian J, Honvo G, Emonts P, et al. Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: a systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Womens Health (Lond). 2019;15:1745506519844044. doi:10.1177/1745506519844044

- Surkan PJ, Ettinger AK, Hock RS, et al. Early maternal depressive symptoms and child growth trajectories: a longitudinal analysis of a nationally representative US birth cohort. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14(1):185. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-14-185

- Ansari NS, Shah J, Dennis C, et al. Risk factors for postpartum depressive symptoms among fathers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100(7):1186–1199. doi:10.1111/aogs.14109

- Zanardo V, Manghina V, Giliberti L, et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 quarantine measures in northeastern Italy on mothers in the immediate postpartum period. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020;150(2):184–188. doi:10.1002/ijgo.13249

- An R, Chen X, Wu Y, et al. A survey of postpartum depression and health care needs among Chinese postpartum women during the pandemic of COVID-19. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2021;35(2):172–177. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2021.02.001

- Kornfield SL, White LK, Waller R, et al. Risk and resilience factors influencing postpartum depression and mother-infant bonding during COVID-19. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(10):1566–1574. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00803

- Miranda AR, Scotta AV, Cortez MV, et al. Triggering of postpartum depression and insomnia with cognitive impairment in Argentinian women during the pandemic COVID-19 social isolation in relation to reproductive and health factors. Midwifery. 2021;102:103072. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2021.103072

- Suárez-Rico BV, Estrada-Gutierrez G, Sánchez-Martínez M, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and perceived stress in postpartum Mexican women during the COVID-19 lockdown. IJERPH. 2021;18(9):4627. doi:10.3390/ijerph18094627

- Mirzaei N, Jahanian Sadatmahalleh S, Bahri Khomami M, et al. Sexual function, mental health, and quality of life under strain of COVID-19 pandemic in Iranian pregnant and lactating women: a comparative cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19(1):66. doi:10.1186/s12955-021-01720-0

- Chaudhary V, Puri M, Kukreti P, et al. Postpartum depression in covid-19 risk-stratified hospital zones: a cross-sectional study from India. J Affect Disord Rep. 2021;6:100269. doi:10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100269

- Hiiragi K, Obata S, Misumi T, et al. Psychological stress associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in postpartum women in Yokohama, Japan. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2021;47(6):2126–2130. doi:10.1111/jog.14776

- Yakupova V, Suarez A, Kharchenko A. Birth experience, postpartum PTSD and depression before and during the pandemic of COVID-19 in Russia. IJERPH. 2021;19(1):335. doi:10.3390/ijerph19010335

- McFarland MJ, McFarland CAS, Hill TD, et al. Postpartum depressive symptoms during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic: an examination of population birth data from Central New Jersey. Matern Child Health J. 2021;25(3):353–359. doi:10.1007/s10995-020-03116-w

- Citu C, Gorun F, Motoc A, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum depression in Romanian women during two periods of COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Med. 2022;11(6):1628. doi:10.3390/jcm11061628

- Galletta MAK, Oliveira AdS, Albertini JGL, et al. Postpartum depressive symptoms of Brazilian women during the COVID-19 pandemic measured by the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. J Affect Disord. 2022;296:577–586. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.09.091

- Sudhinaraset M, Landrian A, Mboya J, et al. The economic toll of COVID-19: a cohort study of prevalence and economic factors associated with postpartum depression in Kenya. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2022;158(1):110–115. doi:10.1002/ijgo.14142

- Handelzalts JE, Hairston IS, Levy S, et al. COVID-19 related worry moderates the association between postpartum depression and mother-infant bonding. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;149:83–86. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.02.039

- Overbeck G, Rasmussen IS, Siersma V, et al. Mental well-being during stages of COVID-19 lockdown among pregnant women and new mothers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):92. doi:10.1186/s12884-021-04374-4

- Roumieh M, Bashour H, Kharouf M, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for postpartum depression among women seen at primary health care centres in Damascus. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):519. doi:10.1186/s12884-019-2685-9

- Isosävi S, Diab SY, Qouta S, et al. Caregiving representations in war conditions: associations with maternal trauma, mental health, and mother–infant interaction. Infant Ment Health J. 2020;41(2):246–263. doi:10.1002/imhj.21841

- Yoneda K, Hababeh M, Kitamura A, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of Palestine refugee mothers at risk of postpartum depression in Amman, Jordan: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2021;398:s 28. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01514-2

- Fellmeth G, Plugge E, Fazel M, et al. Prevalence and determinants of perinatal depression among labour migrant and refugee women on the Thai-Myanmar border: a cohort study. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):168. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-02572-6

- Abulaiti A, Abudurexiti M, Nuermaimaiti A, et al. Analysis of the incidence and influencing factors of postpartum depression and anxiety: a cross-sectional study in Xinjiang from 2018 to 2021. J Affect Disord. 2022;302:15–24. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2022.01.069

- Hetherington E, Adhikari K, Tomfohr-Madsen L, et al. Birth outcomes, pregnancy complications, and postpartum mental health after the 2013 calgary flood: a difference in difference analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0246670. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0246670

- Paquin V, Elgbeili G, Laplante DP, et al. Positive cognitive appraisal “buffers” the long-term effect of peritraumatic distress on maternal anxiety: the Queensland flood study. J Affect Disord. 2021;278:5–12. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.041

- Kuroda Y, Goto A, Koyama Y, et al. Antenatal and postnatal association of maternal bonding and mental health in Fukushima after the great east Japan earthquake of 2011: the Japan environment and children’s study (JECS). J Affect Disord. 2021;278:244–251. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.021

- Murakami K, Ishikuro M, Obara T, et al. Traumatic experiences of the great east Japan earthquake and postpartum depressive symptoms: the Tohoku medical megabank project birth and three-generation cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2023;320:461–467. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2022.09.139

- Klainin P, Arthur DG. Postpartum depression in Asian cultures: a literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(10):1355–1373. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.02.012

- Ghaedrahmati M, Kazemi A, Kheirabadi G, et al. Postpartum depression risk factors: a narrative review. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2017;6:60. doi:10.4103/jehp.jehp_9_16

- Payne JL, Maguire J. Pathophysiological mechanisms implicated in postpartum depression. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2019;52:165–180. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2018.12.001

- AlOmar MJ. Factors affecting postpartum depression among women of the UAE and Oman. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;7:231–233.

- Bahk J, Yun S-C, Kim Y, et al. Impact of unintended pregnancy on maternal mental health: a causal analysis using follow up data of the panel study on Korean children (PSKC). BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(1):85. doi:10.1186/s12884-015-0505-4

- Ayoub K, Shaheen A, Hajat S. Postpartum depression in the Arab region: a systematic literature review. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2020;16(Suppl-1):142–155. doi:10.2174/1745017902016010142

- Ahmad F, Salahuddin M, Alsamman K, et al. Neonatal maternal deprivation impairs localized de novo activity-induced protein translation at the synapse in the rat hippocampus. Biosci Rep. 2018;38(3):BSR20180118. doi:10.1042/BSR20180118

- Weinstock M. Alterations induced by gestational stress in brain morphology and behaviour of the offspring. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;65(5):427–451. doi:10.1016/S0301-0082(01)00018-1

- Boccia ML, Razzoli M, Prasad Vadlamudi S, et al. Repeated long separations from pups produce depression-like behavior in rat mothers. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32(1):65–71. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.10.004

- Moazzam S, Jarmasz JS, Jin Y, et al. Effects of high fat diet-induced obesity and pregnancy on prepartum and postpartum maternal mouse behavior. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2021;126:105147. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2021.105147

- Zochowski MK, Kolenic GE, Zivin K, et al. Trends in primary cesarean section rates among women with and without perinatal mood and anxiety disorders. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(10):1585–1591. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00780

- Tizenberg BN, Brenner LA, Lowry CA, et al. Biological and psychological factors determining neuropsychiatric outcomes in COVID-19. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2021;23(10):68. doi:10.1007/s11920-021-01275-3

- Chen Q, Li W, Xiong J, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with postpartum depression during the COVID-19 pandemic: a literature review and meta-analysis. IJERPH. 2022;19(4):2219. doi:10.3390/ijerph19042219

- Shuman CJ, Peahl AF, Pareddy N, et al. Postpartum depression and associated risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Res Notes. 2022;15(1):102. doi:10.1186/s13104-022-05991-8

- Fung K, Dennis C-L. Postpartum depression among immigrant women. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010;23(4):342–348. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e32833ad721

- Mohammad KI, Abu Awad D, Creedy DK, et al. Postpartum depression symptoms among Syrian refugee women living in Jordan. Res Nurs Health. 2018;41(6):519–524. doi:10.1002/nur.21919

- Zafar S, Sikander S, Hamdani SU, et al. The effectiveness of technology-assisted Cascade training and supervision of community health workers in delivering the thinking healthy program for perinatal depression in a post-conflict area of Pakistan – study protocol for a randomized controlled tria. Trials. 2016;17(1):188. doi:10.1186/s13063-016-1308-2

- Shivakumar G, Anderson EH, Surís AM. Managing posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression in women veterans during the perinatal period. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24(1):18–22. doi:10.1089/jwh.2013.4664

- Robrecht DT, Millegan J, Leventis LL, et al. Spousal military deployment as a risk factor for postpartum depression. J Reprod Med. 2008;53(11):860–864.

- Chrzan-Dętkoś M, Rodríguez-Muñoz MF, Krupelnytska L, et al. Good practices in perinatal mental health for women during wars and migrations: a narrative synthesis from the COST action Riseup-PPD in the context of the war in Ukraine. Clínica y Salud. 2022;33(3):127–135. doi:10.5093/clysa2022a14

- Falah-Hassani K, Shiri R, Vigod S, et al. Prevalence of postpartum depression among immigrant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;70:67–82. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.08.010

- Saeed SA, Gargano SP. Natural disasters and mental health. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2022;34(1):16–25. doi:10.1080/09540261.2022.2037524

- Brock RL, O’Hara MW, Hart KJ, et al. Peritraumatic distress mediates the effect of severity of disaster exposure on perinatal depression: the Iowa flood study. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28(6):515–522. doi:10.1002/jts.22056

- Latendresse G, Elmore C, Deneris A. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors as first-line antidepressant therapy for perinatal depression. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2017;62(3):317–328. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12607

- Hutcherson TC, Cieri-Hutcherson NE, Gosciak MF. Brexanolone for postpartum depression. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77(5):336–345. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxz333

- Kang HK, John D, Bisht B, et al. PROTOCOL: effectiveness of interpersonal psychotherapy in comparison to other psychological and pharmacological interventions for reducing depressive symptoms in women diagnosed with postpartum depression in low and Middle-income countries: a systematic r. Campbell Syst Rev. 2020;16:e1074. doi:10.1002/cl2.1074

- Beydokhti TB, Dehnoalian A, Moshki M, et al. Effect of educational-counseling program based on precede-proceed model during pregnancy on postpartum depression. Nurs Open. 2021;8(4):1578–1586. doi:10.1002/nop2.770

- Dafei M, Mojahed S, Dastjerdi G, et al. The effect of cognitive-behavioral counseling of pregnant women with the presence of a spouse on stress, anxiety, and postpartum depression. J Educ Health Promot. 2021;10:131. doi:10.4103/jehp.jehp_926_20

- Crane T, Buultjens M, Fenner P. Art-based interventions during pregnancy to support women’s wellbeing: an integrative review. Women Birth. 2021;34(4):325–334. doi:10.1016/j.wombi.2020.08.009

- Hogan S, Sheffield D, Woodward A. The value of art therapy in antenatal and postnatal care: a brief literature review with recommendations for future research. Int J Art Ther. 2017;22(4):169–179. doi:10.1080/17454832.2017.1299774

- Colella C, McNeill J, Lynn F. The effect of mother-infant group music classes on postnatal depression—a systematic review protocol. PLoS One. 2022;17(10):e0273669. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0273669

- Fancourt D, Perkins R. Effect of singing interventions on symptoms of postnatal depression: three-arm randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;212(2):119–121. doi:10.1192/bjp.2017.29

- Perkins R, Yorke S, Fancourt D. How group singing facilitates recovery from the symptoms of postnatal depression: a comparative qualitative study. BMC Psychol. 2018;6(1):41. doi:10.1186/s40359-018-0253-0

- Hamed-Agbariah A, Rosenfeld, Y. [The added value of art therapy for mothers with post-partum depression in Arabic society in Israel]. Harefuah. 2015;154(9):568–72, 608.

- Sezen C, Ünsalver BÖ. Group art therapy for the management of fear of childbirth. Arts Psychother. 2019;64:9–19. doi:10.1016/j.aip.2018.11.007

- Wahlbeck H, Kvist LJ, Landgren K. Art therapy and counseling for fear of childbirth: a randomized controlled trial. Art Ther. 2020;37(3):123–130. doi:10.1080/07421656.2020.1721399

- Rabiepoor S, Vatankhah-Alamdary N, Khalkhali HR. The effect of expressive writing on postpartum depression and stress of mothers with a preterm infant in NICU. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2020;27(4):867–874. doi:10.1007/s10880-019-09688-2

- Morton A, Forsey P. My time, my space (an arts-based group for women with postnatal depression): a project report. Community Pract. 2013;86:31–34.

- Sarid O, Cwikel J, Czamanski-Cohen J, et al. Treating women with perinatal mood and anxiety disorders (PMADs) with a hybrid cognitive behavioural and art therapy treatment (CB-ART). Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017;20(1):229–231. doi:10.1007/s00737-016-0668-7