Abstract

Objective

In China, there is a unique type of second marriage (SM) family where the woman is remarried, and the man is experiencing his first marriage. Additionally, the woman is older than the man. Therefore, these families experience many challenges: psychological, emotional, and societal pressure. Such family is a typical sample for studying sociocultural and psychological stress influencing on outcome of assisted reproductive technology (ART). This study aimed to investigate the impact of social psychological stress on the live birth outcomes AR.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort, second marriage (SM) families who visited the Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University reproductive center between January 2012 to December 2022 were screened, and 561s marriage families (the SM group) with 5600 first marriage (FM) families (the FM group) were included undergoing their first ART cycles. The primary outcome of this study was the live birth rate (LBR).

Results

The live birth rate (LBR) of SM group (30.7%) is lower than that of the FM group (43.6%) (p < 0.01). After adjustment by logistic regression, the second marriage group (OR = 1.269, 95%CI 1.031–1.562, p = 0.025) were independent factors associated with the outcome of live birth. After propensity score matching (PSM), the live birth rate of SM group (28.7%) is lower than the FM group (35.9%) (0 = 0.011).

Conclusion

The SM family experience higher levels of social and psychological pressure, which lead to lower level of LBR than FM family.

Introduction

In the 1980s, China implemented a strict one-child policy, coupled with a prevalent preference for male offspring, especially in rural areas. This has resulted in a skewed sex ratio at birth. Entering the twenty first century, there is a severe gender imbalance in marriageable age in rural areas, with a significantly higher number of unmarried males of marriageable age compared to female [Citation1]. These remaining unmarried men in rural areas often exhibit characteristics such as low educational attainment, low income, and difficulties in finding marital partners. Due to limited options, they may find themselves choosing older, divorced women as their companions. In such circumstances, women in these marriages are typically older, possibly with children from previous marriages, while the men may be entering marriage for the first time [Citation2]. These constitute new family patterns -SM family. This study hypotheses SM family composition may result in various situations and challenges. Couples in such blended families may experience psychological, emotional, and societal pressures. This study aims to explore the relationship between sociocultural psychological stress and live birth outcomes of ART.

Our team previously use a special model-Chinese New Year holiday to study the impact of the sociocultural psychological stress on the outcome of fresh embryo transfers of in vitro fertilization (IVF) [Citation3]. Emotional challenges are common in remarriage families, often involving complex emotions such as anxiety, tension, jealousy, insecurity, and fear. These emotions may stem from uncertainty and adjustment to the new family dynamics [Citation4]. Role confusion can arise as family members in blended families adjust, leading to uncertainty about their roles and responsibilities within the new family structure, potentially causing confusion and conflicts [Citation5]. The reactions of children are significant, especially if the woman had children from a previous marriage and brings them into the new blended family when remarrying. Children may experience insecurity or hostility toward the stepfather, potentially leading to behavioral or emotional issues [Citation6]. Marital quality in blended families can face challenges as partners navigate coordinating family dynamics and dealing with issues from previous marriages. Blended families may encounter societal and familial expectations and perceptions, leading to social pressure on family members. Feeling of loneliness may arise, particularly among family members, during the initial stages of building intimacy within the new family structure. Managing relationships with ex-spouses and dealing with children from previous marriages may bring about emotional challenges and tensions. Communication issues can arise in remarriage families due to age differences and diverse past experiences between the spouses, potentially leading to misunderstanding and conflicts.

If the woman is of advanced age and in her second marriage, there is a high probability of a history of pregnancy and childbirth. Secondary infertility, which is the inability to conceive or carry a pregnancy to term after previous childbirth, is a common cause of infertility in such cases [Citation7,Citation8]. Blended families, especially those with fertility challenges due to factors like the woman’s advanced age and previous marriages, often seek assistance with reproductive technologies. The diagnosis of infertility often inflicts significant psychological impact on patient [Citation9]. Anxiety, loss of self-esteem, shame, and depression resulting from infertility can affect marital relationship [Citation10]. The process of diagnosing and treating infertility can impact the mutual trust between spouses and, consequently, affect the overall marital relationship. Therefore, in the case of second marriages utilizing in vitro fertilization (IVF) or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) techniques for childbearing, there are additional influencing factors compared to normal families. One crucial factor is the woman’s age, with advanced maternal age being a key determinant of IVF success rates. Advanced maternal age is associated with a decline in reproductive capacity, thereby reducing the success rates of fertility treatments [Citation11]. Marital stability and the stability of family relationships are crucial for the success rates of IVF. The success rates of IVF can be impacted if there is a lack of harmony and support among family members [Citation12]. Financial issues are significant, as the costs associated with the IVF process can impact the financial situation of families. Particularly, in the context of this study, where families may already be facing economic challenges, the expense of IVF can add significant financial pressure. The decision-making process can be challenging, as family members in blended families may need to collectively decide whether to undergo IVF. Given the complex composition of such families, this may lead to intricate family discussions and decision-making dynamics. The factors mentioned above can potentially reduce the success of IVF. This paper aims to investigate the social and cultural pressures, as well as psychological stresses, faced by blended families where the woman has been married before, the woman is older than the man. Additionally, the study seeks to discuss how these pressures may influence the outcome of IVF pregnancies in such reconstituted families.

Materials and methods

Inclusion criteria involve patients who sought their initial IVF treatment at our reproductive center from January 2012 to December 2022. All patients are required to undergo a fresh cycle embryo transfer and follow-up until a live birth outcome is achieved.

Exclusion criteria pertain to patients lacking complete data for relevant variables.

Implementation procedure

Include patients who sought treatment at our reproductive center, undergoing their first cycle of IVF with fresh embryo transfer. Exclude patients with incomplete data. During the fresh embryo transfer cycle, our center employs protocols including the antagonist protocol, the long luteal phase protocol, and the prolonged follicular phase protocol. Ovarian reserve function and doctor’s medication preference are important factors in choosing ovulation induction protocol. On the third day after egg retrieval, transfer two embryos that have developed to the third day cleavage stage, or on the fifth day after egg retrieval, transfer one blastocyst. The embryology laboratory utilizes a systematic evaluation system based on the external morphology of embryos to assign scores, prioritizing the transfer of embryos with higher ratings. Fresh cycle transfers may be canceled in certain situations, such as excessive egg retrieval to prevent ovarian hyperstimulation, elevated blood progesterone levels exceeding 2 ng/mL on hCG day, or the presence of other medical or surgical conditions in the patient that are unfavorable for pregnancy. After embryo transfer, the patient is provided with a fixed luteal support regimen, including daily administration of 90 mg vaginal progesterone gelMERCKSerono) and 20 mg oral dydrogesterone(Abbott). The experimental group consists of couples where the woman is in her second marriage, and the man is in his first marriage, with the additional condition that the woman is older than the man (Second marriage group, SM group). The control group comprises couples where both the man and woman are in their first marriage (First marriage group, FM group).

Data retrieval

Data were collected retrospectively from our hospital’s information system data, which includes patient’s age, educational background, past pregnancy history, BMI, baseline serum hormones as follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) (μIU/mL), luteinizing hormone (LH) (μIU/mL), estrogen (E2) (pg/mL), progesterone (P) (ng/mL), testosterone (T) (ng/mL), prolactin (PRL) (ng/mL), and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) (ng/mL), infertility reason, ovulating protocol, egg retrieval number, embryo transfer number, embryos scoring.

Outcomes

The primary outcome is live birth, defined as the delivery of at least one live born neonate in a given embryo transfer cycle. The secondary outcome is clinical pregnancy, defined by the evidence of fetal cardiac activity by sonograph 30 days after the embryo transfer, and ectopic pregnancy included. The outcomes also included miscarriage and pregnancy loss before 20 weeks.

Statistical analysis

For continuous variables following a normal distribution, use a t-test; for continuous variables not following a normal distribution, use the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Propensity score matching (PSM) was performed to match patients in the FM group with patients in the SM group. The caliper value is set at 0.02. The propensity score data set was constructed using the multivariable logistic regression model, including age, infertility years, infertility reason, education years, FSH, LH, E2, P, PRL, T and AMH. IBM SPSS Statistics version 27.0.1 was used for statistical analysis. GraphPad was used to generate figures.

Results

Patient and clinical characteristics

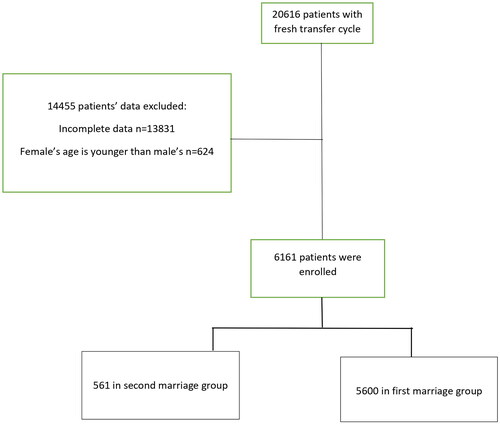

A total of 6161 women () receiving IVF with the first fresh embryo transfer cycle were included in the analysis. Initial screening involved a total of 20,616 couples, with 13,831 patients excluded due to incomplete information, and 624 couples were excluded where the woman was younger than the man. Among all 6,161 couples, where were 561 couples in the SM group and 5,600 patients in the FM group.

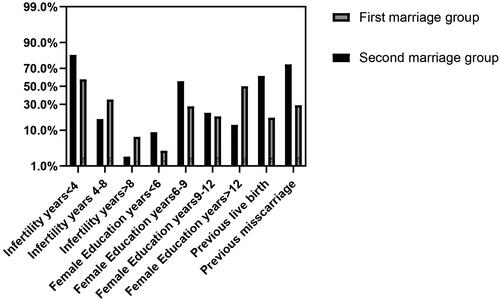

General information of participants is shown in and . The average age of women in the SM group was 34.66 ± 4.09, while in the FM group, it was 30.65 ± 4.34(p < 0.001). Due to the research focus on remarriage where women are older than their spouses, the average age of women in the SM group is higher than that in the FM group. When comparing the ages of men in the two groups, the average age for men in the SM group is 31.07 ± 3.67, and in the FM group, it is 31.37 ± 4.69(p = 0.071). The percentage of patients by years of infertility at <4, 4–8, and above 8 were 81.6, 16.6, 1.8% in the SM group, versus 58.2, 34.6, 7.2%, respectively in the FM group (p < 0.01). It is evident that the infertility years in the SM group is mainly concentrated within 4 years. The proportion of infertility years exceeding 4 years is significantly smaller than that in the FM group. This indicates that the SM group tends to have a shorter duration of infertility, reflecting a greater urgency for pregnancy results in such families. The percentage of patients by years of education at <6, 6–9, 9–12, above 12 were 9.1, 56.1, 21.6 and 13.2% in the SM group, versus 2.5, 28.1, 19.2 and 50.3% in the FM group (p < 0.01). In the SM group, the proportion of education level less than 6 years is higher than that in the FM group. The education level of SM group is primarily concentrated within 6–9 years, with the proportion exceeding 12 years being significantly smaller than in the FM group. The education level in the FM group is primarily concentrated in those with more than 12 years of education. The distribution of educational levels among males in both groups is similar to that of females. The percentage of education years at <6, 6–9, 9–12, above 12 were 5.3, 53.3, 26.6 and 14.8% in the SM group, versus 1.9, 31.0, 21.4 and 45.7% in the FM group. The male education level of SM group is primarily concentrated within 6–9 years, while the male education level in the FM group is primarily concentrated more than 12 years. This indicates that, on average, the educational level in the SM group is generally lower than that in the FM group. The average BMI of SM group is 24.19 ± 3.43, while is 23.63 ± 3.63 in the FM group (p < 0.01). For the past pregnancy history of women, the 61% of SM group had a history of live birth, while 17.7% of FM group had a history of live birth (p < 0.01). In the experimental group, 74.3% of women have a history of miscarriage, comparatively, 29.2% of women in the FM group have a history of miscarriage (p < 0.01). In the study group, where the women are remarried, there may have been a history of childbirth and miscarriage in previous marriages. For the classification of primary and secondary infertility, the primary infertility of the SM group accounted for 13.7%, and the secondary infertility account for 86.3%. For FM group, the primary infertility accounted for 56.7%, and the secondary infertility account for 43.3% (p < 0.01). The causes of infertility can be divided into four categories: tubal factor, male factor, other factor, and multi factors. The proportion of each infertility reason in the SM group is 68.6, 0.5, 29.6 and 1.2%; and in the FM group is 55.6, 0.5, 39.7 and 4.2% (p < 0.01). Compare the base hormone values between the two groups, the average LH of SM group is 4.99 ± 3.51, and the average LH of FM group is 5.19 ± 2.95(p = 0.037). The average baseline P level in the SM group is 1.03 ± 2.6, versus 0.68 ± 0.42 in the FM group (p = 0.026). The average AMH in the SM group is 2.50 ± 1.78, and 3.23 ± 2.56 in the FM group, p < 0.01. The average AMH level in the study group is lower than in the control group, which is associated with the higher average age in the study group compared to the control group. The serum baseline FSH, E2, PRL and T levels were comparable between the two groups.

Table 1. Baseline characters of all participants.

Outcomes of assisted reproductive technology for all participants

The outcomes of the two groups shown in . There were significant differences in use of ovarian stimulation treatment protocols between FM group and SM group (p < 0.01). In the FM group, there were 35.3% patients treated by antagonist protocol, 47.4% by GnRH agonist protocol, 16% by follicular depot GnRHa protocol, 1.2% by other protocol. In contrast, there were 27.2% patients treated by antagonist protocol, 43.3% by GnRH agonist protocol, 29.1% by follicular depot GnRHa protocol, 0.3% by other protocol in FM group. The number of retrieved eggs shows a statistically significant difference between the two groups. In the SM group, the average retrieved eggs number is 9.19 ± 4.79, while in the FM group the average number is 10.25 ± 5.01(p < 0.01). The FM group has a lower number of retrieved eggs, which is related to the higher average age and lower AMH levels than the SM group. The embryo transfer number of the two groups have statistically different. In the SM group, there are 19.3% patients transfer 1 embryo, 80% patients transfer 2 embryos, 0.7% transfer 3 embryos. In the FS group, there are 11.7% patients transfer 1 embryo, 86.9% transfer 2 embryos, 0.4% transfer 3 embryos (p < 0.01). In the FM group, 93.4% patients had day 3 embryos transferred and 6.6% patients had day 5 embryos transferred; while in the FM group, 97.5% patients had day 3 embryos transferred and 2.5% patients had day 5 embryos transferred (p < 0.01). In the SM group, 46.0% had biochemical pregnancy, versus 54.4% in the FM group (p < 0.01). In the SM group, 39.8% had clinical pregnancy, versus 51.1% in the FM group (p < 0.01). In the SM group, 30.7% had live birth, and in the FM group, 43.6% had live birth(p < 0.01). The live birth rate of SM group is lower than that of the control group.

Table 2. Outcome of ART for all participants.

Live birth results for all participants

presents the factors that affect the live birth outcomes after adjustment by logistic regression, indicating that the age (OR = 0.951, 95%CI 0.937–0.964, p < 0.01), serum E2 (OR = 0.998, 95%CI 0.968–1.000, p = 0.018), hCG day endometrium thickness (OR = 1.064, 95%CI 1.037–1.092, p < 0.01). Number of oocytes retrieved (OR = 1.026, 95%CI 1.014–1.038, p < 0.01), the second marriage group(OR = 1.269, 95%CI 1.031–1.562, p = 0.025) were independent factors associated with the outcome of live birth.

Table 3. Univariate analysis and multivariate logistic analysis for all participants.

Outcome of ART for matched participants

The SM group and the FM group exhibited significant differences in baseline conditions. To objectively analyze the differences in live birth rates between the two groups, and to reduce the impact of data bias and confounding factors, we employed propensity score matching to ensure that patients in both groups had similar characteristics. The predictor variables include the factors from that showed differences in multivariate logistic analysis between the two groups: age, E2, AMH, endometrium thickness, oocyte number. The general characters of participants after matching are shown in . Factors related to social and cultural aspects differed between the two groups, including the education level of the female participants, history of live birth, history of miscarriage, infertility classification, and indication for IVF. Other variables were comparable. The assisted reproductive outcomes of the two groups after matching are presented in . After matching, the two groups show no differences in the ovulation induction protocol, HCG day endometrial thickness, number of retrieved eggs, number of transferred embryos and days of embryo transfer. 198 of 537 women from the SM group had clinical pregnancy (36.9%). In contrast, 233 of 537 women from the FM group had clinical pregnancy (43.4%). The SM group had a significantly lower clinical pregnancy rate than that of the FM group (0.029). For live birth, 154 of 537 women from the SM group had live birth (28.7%), versus 195 of 537 women from the FM group had live birth (35.9%). The live birth rate of SM group is lower than the FM group (0 = 0.011). Patients recruiting flow diagram.

Table 4. Characters for matched participants.

Table 5. Outcome for matched participants.

Discussion

This study discusses a unique family dynamic in contemporary Chinese society, characterized by a remarried female partner who is older than the male partner, where the male partner is in his first marriage. For fertility, the age of the female partner is a crucial influencing factor [Citation13]. Indeed, advanced maternal age can impact the quality of eggs [Citation14]. For IVF cycles, the key factors influencing the cumulative pregnancy rate over multiple cycles include the female partner’s age, number of retrieved eggs, number of formed embryos, duration of infertility, BMI and POSEIDON classification [Citation15].The number of retrieved eggs and the formation of embryos are closely correlated with the age of the female partner [Citation16]. Therefore, the baseline conditions for the SM group undergoing IVF may be somewhat less favorable compared to the FM group.

After matching the two groups of patients based on age using PSM, we further compared the pregnancy outcomes of the SM group and FM group within the similar age group. Interestingly, we observed a lower live birth rate in the SM group, and the reasons for this are analyzed as follows:

Considering the family situation, the remarried experimental group has a more purposeful approach in establishing a family. Aiming to build a family quickly and achieve parenthood promptly. This may lead to fewer communication dynamics and a weaker emotional foundation compared to couples in typical families. Marital emotions and satisfaction often influence the success rate of assisted reproduction [Citation17]. Family relationships are a primary factor influencing women’s psychological well-being, and disharmony in family relationships is a major contributor to female depression [Citation18]. Indeed, a woman’s psychological state directly impact pregnancy outcomes [Citation19]. Excessive psychological stress in women can also increase the risk of miscarriage and complications during pregnancy [Citation20]. In addition to marital relationships, psychological stress experienced by women can also originate from the family of the male partner [Citation21]. The male partner being in his first marriage and not having children may lead to expectations from his family for the female partner to fulfill the task of childbirth, creating pressure on the female partner [Citation22]. Especially for women seeking assistance with IVF, the pressure related to childbirth can be even greater [Citation23]. When the female partner is older than the male partner and is in her second marriage, it often sparks discussions based on societal and cultural norms, leading to a certain degree of psychological pressure for both spouses [Citation24]. The female partner being in a second marriage, with a possible history of childbirth with her previous husband, may introduce complexities into the new family dynamics. Bringing children from a previous marriage into the new family requires time and effort to establish close relationships, increasing the adjustment demands on the female partner and consequently elevating psychological stress [Citation25].

The main factors and characteristics contributing to the formation of such second marriage families include: the male partner being from a rural background with lower education and income, insufficient financial resources to meet traditional marriage expectations or provide an adequate dowry, facing obstacles in the marriage process, limited choices, and thus forming a family with economically challenged, older women who have a history of marriage. These characteristics align with our research findings (), where there is a noticeable difference in the educational levels of both female and male partners between the two groups. In the SM group, the educational levels of both men and women are generally lower compared to the FM group. The SM group has a higher number of women with a history of both live births and miscarriages compared to the FM group. Consequently, in the comparison of infertility causes between the two groups, the SM group exhibits a higher proportion of secondary infertility, suggesting a higher incidence of infertility due to female tubal factors. This further confirms that our selection of the population is highly representative, characterized by low educational levels and a history of previous pregnancies. Indeed, study indicate that individuals with lower levels of education tend to have higher scores for depression and anxiety [Citation26]. Another characteristic of the SM group is lower income, making economic constraints a prominent feature even without specific investigation. Low income, low educational attainment, and unemployment are major socioeconomic factors associated with depression [Citation27].

The above analysis suggests that the primary factors influencing pregnancy outcomes in the SM group may be psychological stress arising from family and societal factors [Citation28]. The impact of psychological factors such as stress and depression on the outcomes of IVF has indeed been extensively researched. Researches indicate that psychological stress and anxiety can lead to an increase in serum cortisol levels, and anxiety accompanied by elevated serum cortisol is associated with a decreased pregnancy rate [Citation29–31]. Furthermore, lower levels of serum cortisol on the day of egg retrieval are indicative of a favorable outcome in IVF [Citation32]. Research on the impact of psychological stress on the number of retrieved eggs, the number of transplantable embryos, and embryo fertilization suggests that the baseline emotional stress of patients can affect the number of eggs retrieved and transplantable embryos during IVF [Citation33]. Qian-Ling Li conducted a survey involving 1002 infertile Chinese women, indicating that depression, anxiety and stress can reduce the quantity and quality of retrieved eggs, thereby affecting the fertilization rate of eggs [Citation34]. Li-Hua Huang reported that anxiety-induced sleep disorders can decrease egg quality and fertilization rates [Citation35]. A study on recurrent miscarriage suggests that stress induced an increase in adrenaline, thereby affecting the receptivity of the uterine ling to embryos [Citation36].

There is also evidence linking male infertility with men having feelings of psychological stress and anxiety [Citation37–39]. The impact of psychological stress on sperm quality: A study involving 222 men suggests that stress and depression increase the incidence of erectile dysfunction in men and decrease sperm vitality on the day of egg retrieval. The psychological state present before assisted reproductive technology (ART) can indeed influence sperm vitality [Citation40,Citation41]. Stress and anxiety are associated with lower semen volume, lower sperm density, reduced sperm motility and a higher sperm fragmentation rate [Citation41]. The impact of psychological stress on clinical pregnancy: Previous research suggests that psychological stress can increase oxidative stress, thereby reducing clinical pregnancy rates [Citation42]. After comparison, J M Smeenk believes that anxiety has a greater impact on pregnancy outcomes than depression [Citation43]. A study conducted surveys at three time points-preimplantation, before embryo transfer, and before clinical pregnancy testing-suggesting that psychological stress has a negative impact on clinical pregnancy [Citation44]. The impact of psychological stress on live birth: A study involving 391 women undergoing IVF suggests that stress, depression and other emotional factors have a negative impact on live birth outcome [Citation45]. Research on sleep duration and quality indicates that poor sleep quality is a risk factor affecting live birth in IVF [Citation46–48].

The biggest difference between this study and other psychological research paper is we didn’t use psychological investigation. And we used retrospective analysis to study a specific family then to demonstrate that psychosocial pressure can infect the outcome of ART. Then the subjective error of using questionnaires is avoided.

This study has some limitations that should be considered. Firstly, as it is a retrospective analysis, psychological assessments were not conducted for both male and female participants, making it challenging to evaluate the psychological stress levels of both partners. Secondly, all patients were from a single reproductive center, and although it is the largest reproductive center in Hebei Province, it may not be representative of the entire country. Thirdly, we did not track the psychological well-being of both partners after assisted reproduction. Fourthly, despite adjusting for some confounding factors, there may still be confounding variables that could impact the results. For instance, treatment plans and patient lifestyles, including diet and regional customs are among the confounding variables that could have influenced the results.

Conclusion

In this study, we focused on a specific type of family: where the female partner is in her second marriage, the male partner is in his first marriage, and the female partner is older than the male partner. Families of this type tend to experience higher levels of social and psychological pressure compared to the normal control group. Hence, objectively studying the outcomes of such families in ART can provide insights into the impact of societal and psychological pressures on the outcomes of ART. By bypassing the typical questionnaire surveys on psychological and societal stress, potential subjective biases in the questionnaire process can be effectively avoided.

Ethical approval

We affirm that this research study has been conducted in strict adherence to the principles delineated in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study analyzed the data of fresh embryo transfer (ET) cycles performed at the reproductive center of the Second Hospital of Hebei Medical University between January 2012 and December 2022. As a retrospective research, informed consents were not obtained from patients prior to this study. Consequently, the approval for waiving informed consent was obtained in conjunction with the study protocol from the Research Ethics Committee of the Second Hospital affiliated with Hebei Medical University (Approval number: 2023-R580). Adhering to the guidelines of the Second Hospital affiliated with Hebei Medical University, all sensitive information was expunged prior to extracting data from the Hospital Information System database

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- 安丽巧. 我国农村大龄“剩男”现象成因与对策研究. 硕士. 河北师范大学; MA thesis; 2018.

- 刘强. 我国农村剩男问题研究. 硕士. 烟台大学; MA thesis; 2019.

- Zhai J, Zhang J, He J, et al. Declined live birth rate from in vitro fertilization fresh cycles performed during Chinese new year holiday season. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2023;16:1–13. doi:10.2147/rmhp.S422969

- Seltzer JA. Family change and changing family demography. Demography. 2019;56(2):405–426. doi:10.1007/s13524-019-00766-6

- Dekel R, Shorer S, Nuttman-Shwartz O. Living with spousal loss: continuing bonds and boundaries in remarried widows’ marital relationships. Fam Process. 2022;61(2):674–688. doi:10.1111/famp.12687

- Wiemers EE, Seltzer JA, Schoeni RF, et al. Stepfamily structure and transfers between generations in U.S. families. Demography. 2019;56(1):229–260. doi:10.1007/s13524-018-0740-1

- Vander Borght M, Wyns C. Fertility and infertility: definition and epidemiology. Clin Biochem. 2018;62:2–10. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.03.012

- Carson SA, Kallen AN. Diagnosis and management of infertility: a review. JAMA. 2021;326(1):65–76. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.4788

- Iordachescu DA, Gica C, Vladislav EO, et al. Emotional disorders, marital adaptation and the moderating role of social support for couples under treatment for infertility. Ginekol Pol. 2021;92(2):98–104. doi:10.5603/GP.a2020.0173

- Shafierizi SH, Esmaelzadeh S, Ghofrani F, et al. Role of marital relationship quality in emotional disturbance and personal growth of women with infertility: a cross-sectional study. Int J Fertil Steril. 2023;17(3):174–180. doi:10.22074/ijfs.2022.551247.1281

- La Marca A, Capuzzo M, Longo M, et al. The number and rate of euploid blastocysts in women undergoing IVF/ICSI cycles are strongly dependent on ovarian reserve and female age. Hum Reprod. 2022;37(10):2392–2401. doi:10.1093/humrep/deac191

- Greil AL, McQuillan J, Burch AR, et al. Change in motherhood status and fertility problem identification: implications for changes in life satisfaction. J Marriage Fam. 2019;81(5):1162–1173. doi:10.1111/jomf.12595

- Seshadri S, Morris G, Serhal P, et al. Assisted conception in women of advanced maternal age. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2021;70:10–20. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2020.06.012

- Cakmak H. When is the right time to stop autologous in vitro fertilization treatment in poor responders? Fertil Steril. 2022;117(4):682–687. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2022.02.027

- Esteves SC, Yarali H, Vuong LN, et al. Cumulative delivery rate per aspiration IVF/ICSI cycle in POSEIDON patients: a real-world evidence study of 9073 patients. Hum Reprod. 2021;36(8):2157–2169. doi:10.1093/humrep/deab152

- Shilenkova YV, Pendina AA, Mekina ID, et al. Age and serum AMH and FSH levels as predictors of the number of oocytes retrieved from chromosomal translocation carriers after controlled ovarian hyperstimulation: applicability and limitations. Genes (Basel). Dec 25 2020;12(1):18. doi:10.3390/genes12010018

- Hamzehgardeshi Z, Khalilian A, Peyvandi S, et al. Complex factors related to marital and sexual satisfaction among couples undergoing infertility treatment: a cross-sectional study. Heliyon. 2023;9(4):e15049. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15049

- Ju YJ, Park EC, Ju HJ, et al. The influence of family stress and conflict on depressive symptoms among working married women: a longitudinal study. Health Care Women Int. 2018;39(3):275–288. doi:10.1080/07399332.2017.1397672

- Montagnoli C, Zanconato G, Cinelli G, et al. Maternal mental health and reproductive outcomes: a scoping review of the current literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;302(4):801–819. doi:10.1007/s00404-020-05685-1

- Malekpour P, Hasanzadeh R, Javedani Masroor M, et al. Effectiveness of a mixed lifestyle program in couples undergoing assisted reproductive technology: a study protocol. Reprod Health. 2023;20(1):112. doi:10.1186/s12978-023-01652-6

- Cristian D. The impact of daily stress on sexual activity in stable couples in Romania. Int J Adv Stud Sexol. 2022;4(1): 68–73. doi:10.46388/ijass.2022.4.7

- Szkodziak F, Krzyżanowski J, Szkodziak P. Psychological aspects of infertility. A systematic review. J Int Med Res. 2020;48(6):300060520932403. doi:10.1177/0300060520932403

- Güner Ö, Öztürk R. The development of pressure scale toward marriage and fertility in social structure. Women Health. 2023;63(8):587–598. doi:10.1080/03630242.2023.2249119

- Chen H, Zhang X, Cai S, et al. Even high normal blood pressure affects live birth rate in women undergoing fresh embryo transfer. Hum Reprod. 2022;37(11):2578–2588. doi:10.1093/humrep/deac201

- Turner JJ, Crapo JS, Kopystynska O, et al. Economic distress and perceptions of sexual intimacy in remarriage. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1056180. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1056180

- Shapiro DN, Stewart AJ. Dyadic support in stepfamilies: buffering against depressive symptoms among more and less experienced stepparents. J Fam Psychol. 2012;26(5):833–838. doi:10.1037/a0029591

- Xu H, Ouyang N, Li R, et al. The effects of anxiety and depression on in vitro fertilisation outcomes of infertile Chinese women. Psychol Health Med. 2017;22(1):37–43. Jan doi:10.1080/13548506.2016.1218031

- Buckman JEJ, Saunders R, Stott J, et al. Socioeconomic indicators of treatment prognosis for adults with depression: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(5):406–416. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.0100

- Negris O, Lawson A, Brown D, et al. Emotional stress and reproduction: what do fertility patients believe? J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021;38(4):877–887. doi:10.1007/s10815-021-02079-3

- Chai Y, Li Q, Wang Y, et al. Cortisol dysregulation in anxiety infertile women and the influence on IVF treatment outcome. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1107765. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1107765

- Wdowiak A, Raczkiewicz D, Janczyk P, et al. Interactions of cortisol and prolactin with other selected menstrual cycle hormones affecting the chances of conception in infertile women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(20):7537. doi:10.3390/ijerph17207537

- Alam F, Khan TA, Ali R, et al. SIRTI and cortisol in unexplained infertile females; a cross sectional study, in Karachi, Pakistan. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;59(2):189–194. doi:10.1016/j.tjog.2020.01.004

- An Y, Sun Z, Li L, et al. Relationship between psychological stress and reproductive outcome in women undergoing in vitro fertilization treatment: psychological and neurohormonal assessment. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2013;30(1):35–41. doi:10.1007/s10815-012-9904-x

- Klonoff-Cohen H, Chu E, Natarajan L, et al. A prospective study of stress among women undergoing in vitro fertilization or gamete intrafallopian transfer. Fertil Steril. 2001;76(4):675–687. doi:10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02008-8

- Li QL, Wang C, Cao KX, et al. Sleep characteristics before assisted reproductive technology treatment predict reproductive outcomes: a prospective cohort study of Chinese infertile women. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1178396. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1178396

- Huang LH, Kuo CP, Lu YC, et al. Association of emotional distress and quality of sleep among women receiving in-vitro fertilization treatment. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;58(1):168–172. doi:10.1016/j.tjog.2018.11.031

- Wu W, La J, Schubach KM, et al. Psychological, social, and sexual challenges affecting men receiving male infertility treatment: a systematic review and implications for clinical care. Asian J Androl. 2023;25(4):448–453. doi:10.4103/aja202282

- Ma J, Zhang Y, Bao B, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of erectile dysfunction, psychological disorders, and sexual performance in primary vs. secondary infertility men. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2021;19(1):43. doi:10.1186/s12958-021-00720-5

- Niederberger C. Re: male factor infertility and lack of openness about infertility as risk factors for depressive symptoms in males undergoing assisted reproductive technology treatment in Italy. J Urol. 2018;199(1):18. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2017.09.084

- Wu J, Lin S, Huang P, et al. Maternal anxiety affects embryo implantation via impairing adrenergic receptor signaling in decidual cells. Commun Biol. 2022;5(1):840. doi:10.1038/s42003-022-03694-1

- Bártolo A, Reis S, Monteiro S, et al. Psychological adjustment of infertile men undergoing fertility treatments: an association with sperm parameters. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2016;30(5):521–526. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2016.04.014

- Vellani E, Colasante A, Mamazza L, et al. Association of state and trait anxiety to semen quality of in vitro fertilization patients: a controlled study. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(6):1565–1572. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.01.098

- Prasad S, Tiwari M, Pandey AN, et al. Impact of stress on oocyte quality and reproductive outcome. J Biomed Sci. 2016;23(1):36. doi:10.1186/s12929-016-0253-4

- Smeenk JM, Verhaak CM, Eugster A, et al. The effect of anxiety and depression on the outcome of in-vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(7):1420–1423. doi:10.1093/humrep/16.7.1420

- Bai CF, Cui NX, Xu X, et al. Effectiveness of two guided self-administered interventions for psychological distress among women with infertility: a three-armed, randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod. 2019;34(7):1235–1248. doi:10.1093/humrep/dez066

- de Klerk C, Hunfeld JA, Heijnen EM, et al. Low negative affect prior to treatment is associated with a decreased chance of live birth from a first IVF cycle. Hum Reprod. 2007;23(1):112–116. doi:10.1093/humrep/dem357

- Liu Z, Zheng Y, Wang B, et al. The impact of sleep on in vitro fertilization embryo transfer outcomes: a prospective study. Fertility and Sterility. 2023;119(1):47–55. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2022.10.015

- Yao QY, Yuan XQ, Liu C, et al. Associations of sleep characteristics with outcomes of IVF/ICSI treatment: a prospective cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2022;37(6):1297–1310. doi:10.1093/humrep/deac040