Abstract

Background

To educate the public on how best to support people with fertility problems, a narrative short film “Ten Things Not to Say to Someone Struggling with Infertility” was created, depicting the impact that helpful versus unhelpful dialogue has on someone with fertility problems.

Methods

Before and after watching the video, 419 participants from the public were presented with a hypothetical vignette describing a woman experiencing fertility problems and asked about the likelihood that they would endorse a series of helpful and unhelpful statements when communicating with the protagonist. Pre and post endorsement of helpful versus unhelpful statements were compared, as were self-perceived knowledge about the mental health aspects of fertility problems, confidence in providing emotional support to someone with fertility problems, and empathy for the protagonist.

Results

Participants endorsed fewer unhelpful statements after the video relative to before (M(SD) = 2.2(2.3) vs. 1.3(2.3), p < .001) and fewer participants endorsed at least one unhelpful statement (72% to 47%, p < .001). Self-perceived knowledge of fertility problems, confidence in providing support, and empathy increased at post-test (ps < .001; Cohen’s d = .56–.83) indicating medium-large effects.

Conclusions

A narrative short film appears to be an effective dissemination strategy for sensitizing the public to the emotional struggles of individuals experiencing fertility problems.

Approximately 16% of couples experience fertility problems [Citation1], defined as the inability to attain a successful pregnancy after a year or more of attempts. The distress associated with fertility problems is profound; women struggling to conceive commonly report feelings of shame, self-blame, poor self-esteem, and isolation [Citation2]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that fertility problems are associated with an odds ratio of 1.4 for depression and 1.6 for overall psychological distress [Citation3]. A large longitudinal study conducted in Australia furthermore concluded that the mental health impact of having fertility problems continues to be apparent years after fertility problems have been resolved [Citation4].

It is well-established that positive social support can mitigate the negative effects of stress and chronic health conditions. For instance, it has been demonstrated to protect against adverse mental health outcomes such as depression in people with chronic illness [Citation5], poor quality of life in cancer patients [Citation6], and importantly, stress related to fertility problems [Citation7, Citation8]. Malina and colleagues [Citation9] even found that a 3–5-h social interaction with other patients significantly reduced cortisol levels among in vitro fertilization (IVF) patients relative to watching an informational video. However, negative support provision, whereby friends and family members provide support that is perceived as unhelpful or insensitive, such as offering useless advice or providing judgment without taking the individual’s perspective, is also commonly reported by those experiencing fertility problems [Citation8]. Negative support provision has been linked to increases in mental health conditions in the general population [Citation10], among those with chronic illness [Citation11], and those with fertility problems, specifically [Citation12]. Interventions aimed at increasing positive support provision and decreasing negative support provision may therefore indirectly benefit the mental health of those with fertility problems.

Social Cognitive Theory tells us that behavior, including the tendency toward positive versus negative social support for those struggling to conceive, can be modified through changes in cognitive factors such as understanding of the experiences of people with fertility problems [Citation13]. In line with this theory, research conducted outside the context of fertility issues suggests that empathy – knowing and feeling what another person thinks and feels – is key to the provision of positive as opposed to negative social support [Citation14]. Fostering empathy for those experiencing fertility problems, such as through a video depicting their experiences, may therefore be an effective approach to increasing one’s inclination to provide positive rather than negative support in social interactions with someone struggling to conceive. A large body of research supports the use of video as a means to increase empathy [Citation15–17]; video is therefore often used in training student healthcare professionals to provide effective care for patients in distress [Citation17–19]. Our team therefore developed a first-person narrative short film depicting a woman’s experience with fertility difficulties and the emotional impact that negative social support has on her. To test its efficacy in increasing positive support provision and decreasing negative support provision, participants were provided with a vignette describing a woman struggling to conceive and asked to rate the likelihood that they would use a series of positive and negative support statements in their interactions with the vignette protagonist, both before and after watching “Ten Things Not to Say to Someone Struggling with Infertility” (hereafter referred to as “Ten Things”). It was hypothesized that the number of positive statements would increase while the number of negative statements endorsed would decrease post-video. A secondary analysis explored the relationship between changes in knowledge, confidence, and attitudes toward the protagonist and changes in the endorsement of positive and negative support statements.

Methods

Participants

A sample of 419 Canadian and American participants was obtained through Qualtrics Panel, an online survey sampling service. Individuals were eligible to participate if they were over 18 years of age. While respondents who endorsed personal experience with fertility problems were excluded from most analyses, their responses regarding the quality and realism of the video were recorded. Compensation paid to Qualtrics Panel was $11.50 for each quality response (participant passing the attention checks). The distribution of those funds to individual participants was agreed upon by participants prior to entering the study.

Procedure and design

Developing the “Ten Things Not to Say to Someone Struggling with Infertility” video

Content for the video was first identified by our research team after reviewing participant transcripts from the Dube and colleagues’ [Citation2] qualitative study exploring the various facets of infertility-related distress. From these transcripts, all unhelpful comments reportedly received by participants were highlighted. The research team, along with a panel of five patient partners, reviewed this list to select the top ten comments to be included in the video and brainstormed how these comments would be depicted, ultimately deciding that the video would be a first-person narrative of someone experiencing fertility problems. The senior author (JLG) then drafted an initial script, which was sent to patient partners for feedback to be discussed in a meeting. Changes made by patient partners included several wording changes, changes to who said what unhelpful comment, and props used. A production company, Lampblack Studios, drafted the team’s script into a screenplay, which was again circulated to patient partners for feedback. The patient partners reviewed all audition videos and made final decisions on the chosen actors. A total of five meetings with patient partners were held – one in-person and four over Zoom.

Self-report survey

Pre-vignette

Prior to commencement, the study was approved by the University of Regina’s Research Ethics Board (#2023-144). The present study utilized a within-subjects pre-post design via an online questionnaire. Participants consented and responded to demographic questions prior to disclosing their personal experience with fertility problems (e.g. “Have you or a close relative or friend experienced infertility?”), self-perceived knowledge of fertility problems (e.g. “How would you rate your current knowledge of infertility?”), and support capabilities (e.g. “How confident do you feel in your current ability to support a close family member struggling with infertility?”).

Vignette

Participants were instructed to read a brief vignette describing a friend, “Lisa”, who finally got pregnant after trying for a year, lost the pregnancy, and ended up deciding to pursue IVF after discussing it with her partner.

Post-vignette

Participants were asked about how badly they felt for Lisa and to what extent Lisa is likely to blame for her situation. Participants were also presented with 20 statements asking how likely they would be to say helpful (n = 7; e.g. “You can talk to me. I’m here to listen”) or unhelpful (n = 13; e.g. “Just relax and it’ll happen”) statements toward Lisa. Participants responded on a 5-point Likert scale from “I definitely wouldn’t say this” to “I would definitely say this” (see Supplemental Material).

Video

Participants were then instructed to view the video. The 4:17-min video depicts the fertility journey of “April” as she experiences challenges with IVF, hope from pregnancy, and despair from pregnancy loss. The many unhelpful interactions April has with friends, family, and colleagues are depicted. The film ends with April reflecting on her newfound commitment to being more honest with her loved ones about how they can better support her.

Post-video

Participants then completed three attention checks based on the video. Those that did not successfully complete all 3 checks were excluded from analyses. Questions regarding how surprising the video was, participants’ confidence in supporting people with fertility problems, and their perceived knowledge of fertility problems, were also asked. Participants were again asked to read the scenario with Lisa and respond to the same pre-vignette questions (see above).

Statistical analysis

Paired samples t-tests were used to quantify pre-to-post differences in self-reported understanding of the psychological challenges of fertility difficulties, the number of unhelpful (0–13) and helpful (0–7) statements, and the mean Likert scale endorsement of unhelpful and helpful statements. Two McNemar tests were used to categorically compare changes in the proportion endorsing at least one unhelpful and helpful statement from pre- to post-video and another examined the difference between those that endorsed all helpful statements compared to only some or none from pre- to post-test. Additional analyses were conducted to examine the degree to which changes in self-perceived knowledge, empathy, and confidence were associated with changes in statement endorsement. Specifically, a linear regression then examined changes in self-reported knowledge, confidence, and empathy in predicting pre-to-post changes in the ratio of helpful to unhelpful statement endorsement.

Results

Of the 419 initial recruits, 28 (6.7%) reported having had personal experiences struggling with fertility and were removed from analyses assessing the efficacy of “Ten Things” (i.e. positive and negative statement endorsements, awareness of fertility challenges statements). Demographics of the final sample are described in .

Table 1. Sample demographics.

Video quality

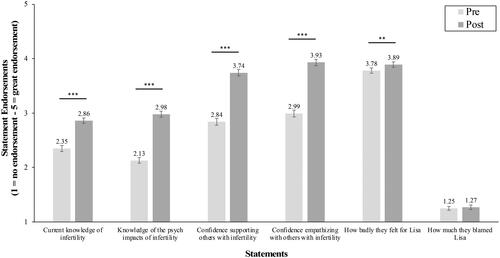

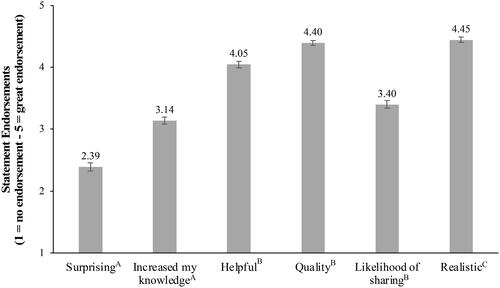

Participant impressions of the video are depicted in . While participants did not consider the video to be very surprising, they considered it to be quite helpful, and of high quality. Of the people who have witnessed or experienced fertility problems personally, the video was considered to be quite realistic.

Figure 1. Mean statement endorsements of the video. Standard error bars are shown. (A) excludes participants with personal experiences of fertility problems. (B) includes both participants with and without personal experiences of fertility problems. (C) includes only participants who have witnessed or had personal experiences with fertility problems.

Awareness of fertility challenges

Participants’ perceptions of their current knowledge of fertility problems, t(390) = 11.02, p < .001, d = .56 (medium to large effect) and current knowledge of the psychological impacts of struggling to conceive, t(390) = 16.40, p < .001, d = .83 (large effect) increased from “poor” to “good” following the video. Similarly, participants’ confidence in supporting, t(390) = 15.37, p < .001, d = .78 (large effect), and empathizing with close family or friends who have fertility problems, t(390) = 15.68, p < .001, d = .79 (large effect), increased from “somewhat” to “fairly confident” following the video. After reading the vignette pre- and post-video, participants reported shifts from feeling “moderately” to “very badly” for the protagonist, Lisa, t(390) = 2.70, p = .004, d = .14 (small effect). Participants endorsed that Lisa was “not at all” to blame for her difficulties conceiving at both at pre- and post-test, t(390) = .54, p = .29, d = .03, on average. Mean scores are depicted in .

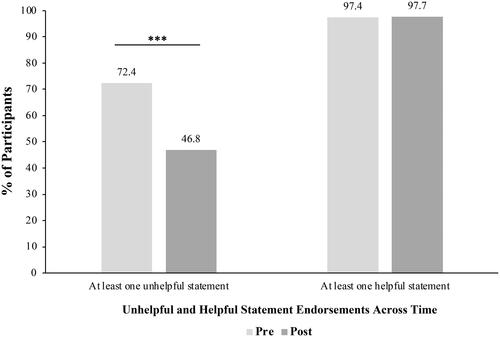

Endorsement of unhelpful statements

Most participants (72.4%) endorsed at least one unhelpful statement pre-video compared to 46.8% post-video. A McNemar test revealed a significant decline in the number of respondents endorsing at least one unhelpful statement from pre- to post-test, χ2(N = 391) = 89.10, p < .001 (see ). A paired samples t-test comparing the total number of unhelpful statements (0–13) at pretest (M = 2.22, SD = 2.34) to those at post-test (M = 1.32, SD = 2.28), was also significant, t(390) = 10.95, p < .001, d = .55 (medium effect). Similarly, mean endorsement on a Likert scale of 1 to 5 significantly decreased from pretest (M = 2.11, SD = 0.67) to post-test (M = 1.69, SD = 0.72), t(390) = 18.25, p < .0001, d = .60 (medium effect).

Endorsement of helpful statements

Pre-video, 97.4% participants endorsed at least one helpful statement compared to 97.7% at post-test. Only 1.57% never endorsed a helpful statement at both pre- and post-test. This was not a significant difference according to a McNemar test, p > .05 (see ), however, a post-hoc McNemar test identified that 40.2% of participants endorsed all helpful statements at post-test, whereas only 32% did at pre. This was identified as a significant difference, χ2(N = 391) = 12.65, p < .001. A paired samples t-test revealed a small yet significant increase in the number of helpful statement endorsements from pre- (M = 5.50, SD = 1.62) to post- (M = 5.69, SD = 1.61) video, t(390) = 3.12, p < .001, d = .16 (small effect). Similarly, mean endorsement from 1 to 5 significantly increased from pretest (M = 4.08, SD = 0.03) to post-test (M = 4.23, SD = 0.71), t(390) = 5.69, p < .0001, d = .30 (small effect).

Processes of change

Changes in the ratio of mean helpful to unhelpful statement endorsement were examined in relation to changes in responses to the items listed in in a single linear regression model. It was found that increases in self-perceived knowledge of the psychological impacts of having fertility problems (β(SE) = 0.04(0.02), p = .018) and changes in the extent to which they blamed Lisa for her problems (β(SE) = 0.06(0.02), p < .001) were associated with a higher ratio of helpful-to-unhelpful statement endorsements. There was also a non-significant trend for changes in how badly they felt for Lisa to predict this ratio ((β(SE) = 0.03(0.02), p = .058). However, changes in knowledge of fertility problems, confidence in providing support to someone in the future and confidence in empathizing in the future were not significantly associated with changes in statement endorsement (p = .248–.926).

Discussion

The present study assessed the effectiveness of a short educational video aimed at promoting positive support provision and decreasing negative support provision in the context of fertility challenges. Specifically, participants were provided a short vignette of a woman experiencing fertility problems and were presented with a list of helpful and unhelpful support comments, both before and after watching the educational video. Results revealed that the video was effective in decreasing the number of unhelpful comments endorsed while to a lesser extent, increasing the number of helpful comments. Additionally, self-perceived knowledge about fertility issues and about the psychological challenges of having fertility problems increased post-video, as did confidence in providing support to someone struggling to conceive and confidence in empathizing with someone experiencing fertility problems. Attitudes toward the vignette protagonist also changed significantly, with respondents having more sympathy for her post-video.

When examining the relationship between changes in knowledge, confidence, and attitudes toward the vignette protagonist in relation to changes in helpful and unhelpful comment endorsement, it was found that the extent to which respondents’ self-perceived knowledge of the psychological impacts of fertility problems increased was associated with a positive change in the ratio of helpful to unhelpful comment endorsement. Decreases in feelings of blame toward the vignette protagonist as well as increases in sympathy for her were also associated with positive changes in the ratio of helpful to unhelpful comments. In contrast, changes in knowledge of fertility problems as well as confidence in providing support to someone who is struggling to conceive were not associated with changes in the endorsement of helpful or unhelpful comments. To a certain extent, these findings support the notion that increases in empathy may be the process by which the video enhances the propensity to provide positive rather than negative social support: viewers come away with an improved understanding of what it must be like to experience fertility problems and, as a result, are less judgmental and more compassionate when faced with a fictional character experiencing fertility problems.

Empathy has long been considered an important facilitator of prosocial/helping behaviors [Citation20], particularly recognized as a key attribute of effective healthcare professionals [Citation21]. Accordingly, several attempts at enhancing empathy in student healthcare workers have been made using videos. Administration of course videos in dental students [Citation16] and medical students [Citation15,Citation17,Citation22] have shown promise in empathy promotion. Like “Ten Things”, many of these videos feature patient perspectives that give insight into difficulties faced by those seeking care or who are struggling with their health. Videos have also been implemented in the public to promote empathy related to stigmatized experiences apart from fertility issues such as mental healthcare seeking [Citation23] and racism [Citation24]. In these situations, narrative storytelling led to more empathy than an informational video [Citation24], supporting the narrative structure of “Ten Things” in producing empathetic responses.

In contrast, most educational material regarding fertility challenges has focused on knowledge uptake or the physiological or medical features with less attention being directed toward the psychosocial aspects of infertility. For example, in one analysis of popular informational videos about fertility issues on YouTube, only six out of the 24 identified examined the mental aspects of fertility challenges compared to 16 that discussed causes or detection of fertility problems, 14 on fertility procedures, and seven addressing lifestyle factors [Citation25]. Beyond “Ten Things”, videos have successfully educated university students about ways to try and prevent fertility issues [Citation26], shared information about fertility knowledge among childless women [Citation27], and improved treatment administration confidence and reduction of treatment errors among IVF patients using treatment direction [Citation28]. Furthermore, existing research suggests that video formats may be ideal for psychoeducational attempts in this population: for instance, video format was favored over text by patients learning fertility content on a fertility clinic’s website and on social media [Citation29]. The current study extends the current literature by suggesting that a video may also be an effective method of educating the public about the psychological aspects of infertility and how best to provide social support to those experiencing it.

Clinical implications

The success of the “Ten Things” video in increasing participants’ tendencies toward positive support provision and away from negative support provision suggests that it may be an effective tool for patients to share with their loved ones to educate them about how best to provide effective social support. Since the video is freely available on YouTube, clinicians working with individuals experiencing fertility problems should be encouraged to share the link to the video with their patients, to be shared with their loved ones. Given that lack of sensitivity among healthcare providers is also a frequent complaint among individuals experiencing fertility problems [Citation2], this video or a similar video tailored for healthcare providers, may also be effective in improving compassion among clinicians that interact with individuals experiencing fertility problems. Creating similar videos that increase understanding of the challenges of specific populations, such as same-sex couples pursuing third party reproduction, may also be helpful in changing judgmental attitudes and improving the quality of social support received.

Strengths and limitations

A notable strength of this study is the involvement of patient partners in forming the unhelpful and helpful statements, and in the production of the video. Some limitations included the fact that most participants were no longer of reproductive age; their knowledge and sensitivity surrounding fertility problems may not reflect those of younger individuals. Our assessment of self-perceived fertility knowledge consisted of a single item and may have been improved through the use of a validated scale. Similarly, the other proposed mechanisms by which the video impacts the quality of support, such as empathy or increased confidence/self-efficacy, could have been assessed more thoroughly using validated scales.

Conclusions

In summary, these findings demonstrate improvements in the publics’ ability to support those with fertility problems after watching “Ten Things”. This is largely backed by decreases in negative statement endorsements post-video, coupled with enhancements in participant’s beliefs regarding their fertility problem knowledge, empathy toward people with fertility challenges, and confidence in supporting people with fertility difficulties. Overall, this study demonstrates the power of online video formats in conveying important anti-stigmatizing messages about fertility issues, thus, providing a foundation for future distribution of fertility problem-based knowledge and awareness.

Authors’ contributions

MJK collected data, conducted statistical analysis, and wrote and revised the manuscript. SKG assisted with statistical analysis and revised the manuscript. AAB conceptualized the video and revised the manuscript. JLG conceptualized the study and revised the manuscript.

Manuscript Supplemental Material_Revised.docx

Download MS Word (15.1 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the film cast and crew at Lampblack Studios for their part in creating “Ten Things Not to Say to Someone Struggling with Infertility.” A heartfelt thank you to the patient advisors who helped make this study possible.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bushnik T, Cook JL, Yuzpe AA, et al. Estimating the prevalence of infertility in Canada. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(3):738–746. doi:10.1093/humrep/der465

- Dube L, Nkosi-Mafutha N, Balsom AA, et al. Infertility-related distress and clinical targets for psychotherapy: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(11):e050373. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050373

- Nik Hazlina HN, Norhayati MN, Shaiful Bahari I, et al. Worldwide prevalence, risk factors and psychological impact of infertility among women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2022;12(3):e057132. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057132

- Bagade T, Thapaliya K, Breuer E, et al. Investigating the association between infertility and psychological distress using Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health (ALSWH). Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):10808. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-15064-2

- Warner CB, Roberts AR, Jeanblanc AB, et al. Coping resources, loneliness, and depressive symptoms of older women with chronic illness. J Appl Gerontol. 2019;38(3):295–322. doi:10.1177/0733464816687218

- Gonzalez-Saenz de Tejada M, Bilbao A, Baré M, CARESS-CCR Group., et al. Association between social support, functional status, and change in health-related quality of life and changes in anxiety and depression in colorectal cancer patients: social support, functional status, HRQoL, and distress in CRC. Psychooncology. 2016;26(9):1263–1269. doi:10.1002/pon.4303

- Martins MV, Peterson BD, Almeida VM, et al. Direct and indirect effects of perceived social support on women’s infertility-related stress. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(8):2113–2121. doi:10.1093/humrep/der157

- Martins MV, Peterson BD, Almeida V, et al. Dyadic dynamics of perceived social support in couples facing infertility. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(1):83–89. doi:10.1093/humrep/det403

- Malina A, Głogiewicz M, Piotrowski J. Supportive social interactions in infertility treatment decrease cortisol levels: experimental study report. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2779. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02779

- Croezen S, Picavet HSJ, Haveman-Nies A, et al. Do positive or negative experiences of social support relate to current and future health? Results from the Doetinchem cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):65. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-65

- Ahn S, Kim S, Zhang H. Changes in depressive symptoms among older adults with multiple chronic conditions: role of positive and negative social support. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(1):1–11. doi:10.3390/ijerph14010016

- Balsom AA, Gordon JL. The relationship between psychological coping and mood across the menstrual cycle among distressed women struggling to conceive. J Psychosom Res. 2021;145:110465. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110465

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. p. 617.

- Verhofstadt L, Devoldre I, Buysse A, et al. The role of cognitive and affective empathy in spouses’ support interactions: an observational study. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0149944. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0149944

- Ahmadzadeh A, Esfahani MN, Ahmadzad-Asl M, et al. Does watching a movie improve empathy? A cluster randomized controlled trial. Can Med Educ J. 2019;10(4):e4–e12. doi:10.36834/cmej.56979

- Anishchuk S, Kubacki A, Howell Y, et al. Can a virtual learning module foster empathy in dental undergraduate students? Eur J Dent Educ. 2023;27(1):118–125. doi:10.1111/eje.12783

- Hojat M, Axelrod D, Spandorfer J, et al. Enhancing and sustaining empathy in medical students. Med Teach. 2013;35(12):996–1001. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2013.802300

- O’Brien R, Goldberg SE, Pilnick A, et al. The VOICE study – a before and after study of a dementia communication skills training course. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0198567. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0198567

- Sweeney K, Baker P. Promoting empathy using video-based teaching. Clin Teach. 2018;15(4):336–340. doi:10.1111/tct.12693

- Lehmann K, Böckler A, Klimecki O, et al. Empathy and correct mental state inferences both promote prosociality. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):16979. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-20855-8

- Moudatsou M, Stavropoulou A, Philalithis A, et al. The role of empathy in health and social care professionals. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(1):26. doi:10.3390/healthcare8010026

- Salajegheh M, Sohrabpour AA, Mohammadi E. Exploring medical students’ perceptions of empathy after cinemeducation based on Vygotsky’s theory. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24(1):94. doi:10.1186/s12909-024-05084-z

- Keum BT, Hearns M, Agarwal P, et al. Online digital storytelling video on promoting men’s intentions to seek counselling for depression: the role of empathy. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2022;68(7):1363–1372. doi:10.1177/00207640211023532

- Keum BT, Nguyen MMG, Ahn LH, et al. Fostering Asian American emerging adults’ advocacy against anti-black racism through digital storytelling. Counseling Psychol. 2024;52(4):581–613. doi:10.1177/00110000241227994

- Kelly-Hedrick M, Grunberg PH, Brochu F, et al. “It’s totally okay to be sad, but never lose hope”: Content analysis of infertility-related videos on YouTube in relation to viewer preferences. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(5):e10199. doi:10.2196/10199

- Conceição C, Pedro J, Martins MV. Effectiveness of a video intervention on fertility knowledge among university students: a randomised pre-test/post-test study. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2017;22(2):107–113. doi:10.1080/13625187.2017.1288903

- Pedro J, Fernandes J, Barros A, et al. Effectiveness of a video-based education on fertility awareness: a randomized controlled trial with partnered women. Hum Fertil (Camb). 2022;25(3):522–533. doi:10.1080/14647273.2020.1854482

- Adeleye A, Cruz K, Cedars MI, et al. Learning from online video education (LOVE) improves confidence in fertility treatments: a randomized controlled trial. NPJ Digit Med. 2022;5(1):128. doi:10.1038/s41746-022-00673-y

- Jones CA, Mehta C, Zwingerman R, et al. Fertility patients’ use and perceptions of online fertility educational material. Fertil Res Pract. 2020;6(1):11. doi:10.1186/s40738-020-00083-2