ABSTRACT

Purpose: To present nine new cases of superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis (SOVT) and compare these with the literature, and to assess the impact of SOVT for the clinician.

Methods: Using the data bases of the Department of Ophthalmology of the AMC, we searched for patients with radiologically evidenced SOVT between January 2006 and December 2014. In addition, a PubMed search, using the mesh term ‘superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis’, was done.

Results: We found nine patients with SOVT. In three patients, SOVT was related to dural arteriovenous fistulae. In one patient, it was caused by the acute reversal of warfarin by vitamin K. In two patients, an infectious cause was found. In three patients, the cause of SOVT was not found despite screening for coagulation and other disorders. All patients presented with eyelid swelling, proptosis, and/or motility impairment. We found complete recovery in four patients. Three patients had mild sequelae and two patients had severe visual impairment. In the literature, we found 60 cases reporting on SOVT with various aetiologies. Clinical presentation, treatment modalities, and outcomes were comparable to our findings.

Conclusion: Our case series and literature review show that SOVT can occur simultaneously with cavernous sinus thrombosis (CST) but can also be a separate entity. Clinical presentation can mimic orbital cellulitis (OC) or CST and when no signs of OC can be found, an alternative cause for SOVT should be sought. When timely and adequate treatment is conducted, the prognosis is predominantly favourable.

Introduction

Superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis (SOVT) is a clinical and radiologic diagnosis and its implications may not entirely be clear to the clinician. Apart from anecdotal case reports, systematic evaluations of SOVT are scarce. Causes of SOVT can be septic or aseptic. SOVT may present similar to, or occur together with, orbital cellulitis (OC) or cavernous sinus thrombosis (CST). Presenting signs of SOVT are caused by venous congestion and include eyelid swelling, proptosis, motility impairment, or even vision loss. We evaluated our own series and compared our findings with those described in literature.

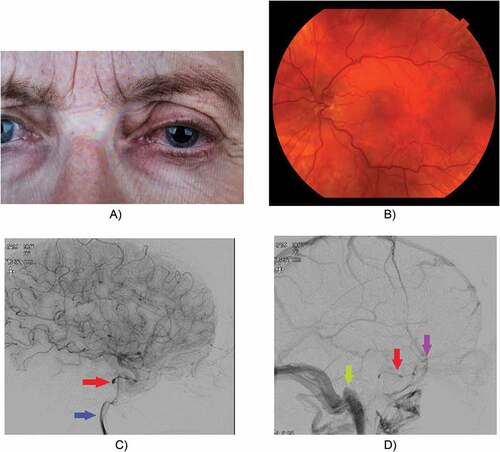

Figure 2. Female, 62 years old. Left-sided SOVT caused by a small dural fistula. Treatment with anticoagulants. No coiling possible because of the small size of the fistula. Secondary macular oedema to some extent successfully treated with bevacizumab injections. Follow-up imaging showed a normal SOV.

Methods

We retrieved files from all patients in whom a diagnosis of SOVT has been made between January 1, 2006 and December 31, 2014 at the Department of Ophthalmology of the Academic Medical Center of the University of Amsterdam, a tertiary referral centre in the Netherlands (estimated population 17 million). We searched our electronic database for patients with a diagnosis of SOVT. A dedicated neuroradiologist (MMdW) reviewed all cases to confirm the diagnosis. Inclusion criteria were thickened or dilated superior ophthalmic vein (SOV) with a filling defect. All other cases were excluded. Charts were reviewed for demographic characteristics, ophthalmic examination, imaging results, and cause of SOVT. Use of antibiotic therapy, anticoagulation therapy (ACT), treatment of ocular hypertension, and surgical intervention were noted. Outcomes were evaluated for mortality, visual acuity, and eye movements.

In addition, on May 3, 2018, we searched in PubMed using the searchterm: ‘superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis’, and looked into the articles available in English containing case reports of SOVT.

Formal ethical approval was not required because the preexisting data had been anonymized. All investigations and treatments were carried out in line with accepted clinical practice.

Results

AMC-series

Over an 8-year span, we found nine patients with radiologically confirmed SOVT. Patient’s characteristics, presentation, imaging results, treatment, and outcome are summarized in . The median age was 56 (40–79), and we found four male and five female patients. The majority of the patients were aseptic (seven out of nine). In three patients, SOVT was caused by spontaneous thrombosing of dural arteriovenous fistula. One patient had SOVT caused by reversal of ACT by vitamin K. Two patients had a septic cause of SOVT; one was diagnosed with bacterial OC caused by paranasal sinusitis and another patient had OC due to a dental infection. In three patients, the cause was not found despite investigations for coagulation disorders by haematologists. One of these three patients, however, did have a history of Graves’ Orbitopathy. Two of the patients had SOVT and CST simultaneously. All patients presented with symptoms of orbital pathology: eyelid swelling, chemosis, proptosis, impaired ocular motility, reduced visual acuity and/or increased intraocular pressure. Visual acuity was impaired in four patients and one patient presented with no light perception at all. Treatment consisted of intravenous antibiotics, anticoagulants, eye pressure lowering medication, and/or surgical intervention. Seven out of nine patients were treated with anticoagulant therapy, and in none of these, haemorrhage complications occurred. There was no mortality. We found a complete recovery in four patients. One patient had persistent mild exophthalmos, and two patients had secondary cystoid macula oedema which was successfully treated with bevacizumab injections. The patient who presented with no light perception did not regain her visual acuity. The three other patients who presented with impaired visual acuity partially regained their vision.

Table 1. Case series, patient characteristics (CST: cavernous sinus thrombosis, SOV: Superior ophthalmic vein).

Literature search

The initial search yielded 220 titles. Two authors separately screened the titles (KW and NP), for articles about SOVT and CST. Of the screened titles, 81 were considered to be eligible. Screening the abstracts, we found that 15 articles were not published in English and 9 articles did not contain a (new) case report of SOVT. Five articles were not available as full text, despite extensive efforts of our librarian. This resulted in a total of 52 articles containing 60 cases.

Of the 60 cases, 31 were female and 27 were male (in two cases, the gender was not specified). The median age was 53 (range 10 months–88 years). We found more cases caused by aseptic aetiology compared to septic disorders. Details on all cases can be found in supplementary data (supplementary table 1).

Discussion

The superior ophthalmic vein is a valve-less vein which is responsible for most of the venous drainage of the orbit. SOVT is caused by altered venous blood flow, which can be the result of stasis of blood flow, trauma to the vessel wall, or hypercoagubility disorders. Both septic and aseptic causes of SOVT are known. Aseptic causes of SOVT can be explained by alterations of blood flow due to anatomical or systemic causes. SOVT is seen in patients with flow alterations in the orbital vascular system, such as in dural arteriovenous fistulae in the direct vicinity of the cavernous sinus.Citation1–Citation5 Facial trauma is another aseptic cause of SOVT, reported in literature.Citation6–Citation8 Systemic diseases reporting SOVT in literature include Graves’ Orbitopathy, systemic lupus erythematosus, and ulcerative colitis.Citation9–Citation13 Hematologic aetiologies include antiphospholipid syndrome and sickle trait.Citation14–Citation17 Also, hormone therapies have been reported as a cause for SOVT (e.g. tamoxifen, oral contraceptive pill).Citation18–Citation20 Other causes of aseptic SOVT include Tolosa-Hunt syndrome and idiopathic orbital inflammatory disease.Citation21,Citation22 Not seldom, the cause remains unknown despite investigations for coagulation disorders or systemic diseases.Citation23–Citation26 On the other hand, in some cases SOVT can be the first clinical sign of a new diagnosis such as arteriovenous fistulae or systemic disorders.Citation11,Citation12

Septic causes of SOVT include infections of the paranasal sinuses, orbit, teeth, and face. In literature, paranasal sinusitis is the most common cause of septic SOVT.Citation13,Citation27–Citation33 In our series, the majority of cases were aseptic (77.8%). This corresponds to the literature, where we also found more aseptic SOVT (66.7%). The exact incidence of SOVT is not known but is often described as ‘rare’. This is reflected in the literature by the fact that we only found 60 cases since 1975.Citation14,Citation18

For an overview of SOVT aetiology in literature, see .

Table 2. Literature review. Aetiology of cases in literature (total number of cases: 60).

Presentation

The clinical presentation of SOVT can be explained by congestion of the orbit due to the impaired venous drainage. Patients usually present with pain, chemosis, eyelid oedema, proptosis, limited ocular motility, with or without fundus findings, and impaired visual acuity. These symptoms are similar to the symptoms of CST and OC, and thus those entities can be hard to be distinguished clinically. Moreover, SOVT, CST, and OC can occur together.

In our series, we found SOVT to be a unilateral disease in all cases. In our literature review, 85% of cases presented with unilateral complaints. In patients with CST, however, patients usually have an onset with unilateral ophthalmic signs, with rapid development to bilateral signs and symptoms.Citation34

If patients present themselves without septic symptoms and there is no suspicion of OC, one must look for another underlying condition. Imaging can rule out or demonstrate vascular abnormalities. Laboratory examinations should be performed for systemic and hypercoagulable disorders.

Imaging

The diagnosis of SOVT is assessed by imaging, preferably contrast enhanced CT or MR imaging. On a contrast-enhanced CT-scan, SOVT is characterized by a thickened SOV with an indistinct outer border due to perivascular oedema compared to the other side. A filling defect can be seen within the SOV itself, or a thin lining can be present close to the vessel wall, either due to vessel wall enhancement or a small lumen in between the clot and the vessel wall.Citation35 In case of a chronic SOV thrombosis, the central thrombus can also show enhancement opposite to the acute stage. MRI shows enhancement of intraorbital fat and swelling and enhancement of the eye musculature due to the venous congestion. Similar to contrast enhanced CT, MRI can show intra-luminal filling defects in the SOV, as shown in . Secondary signs include proptosis and thickening of the extraocular muscles.Citation23

Management

If an underlying cause is found, a targeted treatment is possible. Treatment may include antibiotics, steroids, ACT, and/or surgery. The choice of antibiotics should be based on the pathogens usually found in the suspected source of infection, while waiting for culture. There is no consensus on duration of antibiotic therapy. No aggregated evidence is available for the use of steroids in SOVT.

ACT was initially disputed because of fear for haemorrhagic complications. More recent literature shows that the risk of haemorrhages is acceptable in most patients and that the use of anticoagulants promotes a smooth instead of an abrupt transition to normal flow conditions. In a recent review, Weerashinghe et al. concluded ACT to be associated with reduced mortality in CST patients.Citation36 However, their conclusion is based on a review of case reports with a great heterogeneity of patients and treatment schemes. Although current reports favour ACT, the optimal dose and duration is not known. Surgery may be necessary for an underlying cause of SOVT like sinusitis, orbital abscess, or dental infection.

Prognosis

Early detection of SOVT is crucial to prevent progression to CST and its severe effects. In the case reports we found, SOVT mostly resolved without any serious sequelae. However, 3 out of 60 literature cases died and 7 of the cases did not regain any visual acuity after presenting with no light perception. The majority of cases fortunately reported complete recovery.

Conclusion

We present 9 new cases of SOVT and an overview of 60 previously described cases in literature. We found a variation in both septic and aseptic causes of SOVT, and both in our cases as in literature, the majority of SOVT was caused by aseptic disorders. Patients clinically present with typical orbital symptoms, which can also mimic OC and CST. Thus, especially in patients presenting with OC without sinusitis or other signs of inflammation, SOVT should be considered. Underlying pathology should be sought for, such as systemic diseases or haematological disorders.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (369.2 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Supplementary data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/01676830.2018.1497068

References

- Levin MH, Moss HE, Pineles SL, et al. Orbital congestion complicating treatment of cerebral vascular anomalies. World Neurosurg. 2014;82(1–2):239.e213-237. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2013.01.093.

- Pendharkar HS, Gupta AK, Bodhey N, Nair M. Diffusion restriction in thrombosed superior ophthalmic veins: two cases of diverse etiology and literature review. J Radiol Case Rep. 2011;5(3):8–16. doi:10.3941/jrcr.v5i3.547.

- Theaudin M, Saint-Maurice JP, Chapot R, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of dural carotid-cavernous fistulas: a consecutive series of 27 patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(2):174–179. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2006.100776.

- Lau LI, Wu HM, Wang AG, Yen MY, Hsu WM. Paradoxical worsening with superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis after gamma knife radiosurgery for dural arteriovenous fistula of cavernous sinus: a case report suggesting the mechanism of the phenomenon. Eye (Lond). 2006;20(12):1426–1428. doi:10.1038/sj.eye.6702287.

- Churojana A, Chawalaparit O, Chiewwit P, Suthipongchai S. Spontaneous occlusion of a bilateral post traumatic carotid cavernous fistula. Interv Neuroradiol. 2001;7(3):245–252. doi:10.1177/159101990100700311.

- Mishima M, Yumoto T, Hashimoto H, et al. Superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis associated with severe facial trauma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2015;9:244. doi:10.1186/s13256-015-0737-y.

- Akingbola OA, Shar B, Singh D, Frieberg E, Petrescu M. Posttraumatic superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis in a 2 years old. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(2):108–110. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000000066.

- Jones ST, Schoenberg ED, Shah B, Valenzuela AA. Traumatic superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis in a child. Orbit. 2012;31(5):355–357. doi:10.3109/01676830.2012.700546.

- Sorrentino D, Taubenslag KJ, Bodily LM, Duncan K, Stefko T, Yu JY. Superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis: a rare complication of Graves’ orbitopathy. Orbit. 2018;37(3):175–178. doi:10.1080/01676830.2017.1383467.

- Park HS, Gye HJ, Kim JM, Lee YJ. A patient with branch retinal vein occlusion accompanied by superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis due to severe superior ophthalmic vein enlargement in a patient with graves ophthalmopathy. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25(4):e322–324. doi:10.1097/SCS.0000000000000586.

- Baidoun F, Issa R, Ali R, Al-Turk B. Acute unilateral blindness from superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis: a rare presentation of nephrotic syndrome from class iv lupus nephritis in the absence of antiphospholipid or anticardiolipin syndrome. Case Rep Hematol. 2015;2015:413975.

- Sambhav K, Shakir O, Chalam KV. Bilateral isolated concurrent superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Int Med Case Rep J. 2015;8:181–183. doi:10.2147/IMCRJ.S87518.

- Mandic JJ, Mandic K, Mrazovac D. Superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis with complete loss of vision as a complication of autoimmune and infective conditions. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2017;1–3. doi:10.1080/09273948.2017.1313433.

- Lim LH, Scawn RL, Whipple KM, et al. Spontaneous superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis: a rare entity with potentially devastating consequences. Eye (Lond). 2014;28(3):348–351. doi:10.1038/eye.2013.273.

- Dey M, Charles Bates A, McMillan P. Superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis as an initial manifestation of antiphospholipid syndrome. Orbit. 2013;32(1):42–44. doi:10.3109/01676830.2012.736600.

- Idrees Z, Dooley I, Jackson A, Roche C, Fahy G. Simultaneous isolated bilateral superior orbital vein thrombosis as a presenting feature of antiphospholipid syndrome. Orbit. 2014;33(3):214–216. doi:10.3109/01676830.2014.881398.

- Rao R, Ali Y, Nagesh CP, Nair U. Unilateral isolated superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2018;66(1):155–157. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_791_17.

- Lai PF, Cusimano MD. The spectrum of cavernous sinus and orbital venous thrombosis: a case and a review. Skull Base Surg. 1996;6:53–59.

- Michaelides M, Aclimandos W. Bilateral superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis in a young woman. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2003;81:88–90.

- Jaais F, Habib ZA. Unilateral superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis in a user of oral contraceptives. Med J Malaysia. 1994;49:416–418.

- Spirn FH, Wolintz AH, Tenner MS, Gombos GM. Tolosa-hunt syndrome. Ann Ophthalmol. 1975;7:1087–1090.

- Carrim ZI, Ahmed TY, Wykes WN. Isolated superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis with orbital congestion: a variant of idiopathic orbital inflammatory disease? Eye (Lond). 2007;21(5):665–666. doi:10.1038/sj.eye.6702655.

- Coban G, Cetinkaya A, Karalezli A, Donmez FY, Ozbek N. Unilateral superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis in a neonate. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;29(6):e154–156. doi:10.1097/IOP.0b013e3182831f18.

- Hsu HY, Chao AC, Chen YY, et al. Reflux of jugular and retrobulbar venous flow in transient monocular blindness. Ann Neurol. 2008;63(2):247–253. doi:10.1002/ana.21299.

- Baskara Rajan G, Thiruvenkatasamy K, Jayakumar V, Dorairaj G, Ramesh S, Visvanathan J. Idiopathic superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis. Indian Pediatr. 1981;18:74–75.

- Brismar G, Brismar J. Aseptic thrombosis of orbital veins and cavernous sinus. Clinical symptomatology. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1977;55:9–22.

- Thomsen S, Larson E, Greenwood M. Superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis: the role of anticoagulation. S D Med. 2017;70:203–205.

- Komatsu H, Matsumoto F, Kasai M, Kurano K, Sasaki D, Ikeda K. Cavernous sinus thrombosis caused by contralateral sphenoid sinusitis: a case report. Head Face Med. 2013;9:9. doi:10.1186/1746-160X-9-9.

- Gomi H, Gandotra S, Todd C. Septic right superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis complicated by left sphenoid sinusitis. Scand J Infect Dis. 2005;37(4):316–318. doi:10.1080/00365540410021135.

- Ogul H, Gedikli Y, Karaca L, Okur A, Kantarci M. Massive thrombosis of bilateral superior and inferior ophthalmic veins secondary to ethmoidal rhinosunisitis: imaging findings. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25(3):e277–279. doi:10.1097/SCS.0000000000000661.

- Cumurcu T, Demirel S, Keser S, et al. Superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis developed after orbital cellulitis. Semin Ophthalmol. 2013;28(2):58–60. doi:10.3109/08820538.2012.736007.

- Parmar H, Gandhi D, Mukherji SK, Trobe JD. Restricted diffusion in the superior ophthalmic vein and cavernous sinus in a case of cavernous sinus thrombosis. J Neuroophthalmol. 2009;29(1):16–20. doi:10.1097/WNO.0b013e31818e3f40.

- Younis RT, Lazar RH. Cavernous sinus thrombosis: successful treatment using functional endonasal sinus surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;119:1368–1372.

- Desa V, Green R. Cavernous sinus thrombosis: current therapy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70(9):2085–2091. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2011.09.048.

- Walker JC, Sandhu A, Pietris G. Septic superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2002;30:144–146.

- Weerasinghe D, Lueck CJ. Septic cavernous sinus thrombosis: case report and review of the literature. Neuroophthalmology. 2016;40(6):263–276. doi:10.1080/01658107.2016.1230138.