ABSTRACT

This article sets out to test an all too frequently undisputed assumption: contested politics and policy process theories or frameworks from the West, particularly the Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF), the Multiple Streams Framework (MSF) and the Social Construction in Policy Design Framework (SCPDF), can be plausibly ‘transported’ to the Arab world, without misleading biases. It describes and reflects upon practices of civil society associations (CSAs) to influence post-Uprisings public policymaking in three Arab states: Lebanon, Egypt, and Tunisia. The policy issues dealt with are domestic violence against women, and wage policy in Lebanon; dealing with NGOs in Egypt; and transparency of the state in Tunisia. This assumption, of course, is far from self-evident. Concepts like ‘advocacy coalition’, ‘problem stream’, or ‘policy entrepreneur’ describe role patterns in contested politics and policymaking practices in the context of consolidated Western liberal democracies; a context hardly applicable to post-Uprisings Arab states. Rather, we argue that public policymaking in post-Uprisings Arab states could be understood through a ‘regimes-triad approach’; i.e., a mutually dependent set of three strategic action fields—a domestic issue logic, and the logics of a national political regime, and a transnational or international geopolitical or geo-economic regime —around any policy issue. The regimes-triad context intends to correct the biases in western-canon theories of the policy process when applied to Arab states.

Introduction: governing as puzzling and powering on ‘policy’ and ‘policy process’

Modern politics in the Western world usually manifests itself as contestation about governmental policies. This has not always been the case; how governments conduct governing changed over time (Dean, Citation1999, 2010; De Jouvenel, Citation1963; Hoppe, Citation2003; Orren & Skowronek, Citation2017; Spink, Citation2019). Practices of governing are all about the conduct of conduct, i.e., “any more or less calculated and rational activity, undertaken by a multiplicity of authorties and agencies, employing a variety of techniques and forms of knowledge, that seeks to shape conduct by working through the desires, aspirations, interests and beliefs of various actors …“ (Dean, Citation1999, 2010, p. 18, following Foucault). For a long time governing was organized as territorial, legal and administrative sovereignty by feudal kings, combined with mental discipline instilled in ruling élites through military, religious and educational practices. Only since the eighteenth century, governing focused on health, welfare, prosperity, and happiness of ‘each and all’ citizens with nationality. Since then, there has been a shift in the major forms of governing. At first, during the formation of republics with representative government and rule-of-law, politics and governing were about ‘nomomachy’, i.e., parliamentary contestation about laws, meant to order and stabilize society for longer periods of time. During America’s New Deal and Great Society years, and the formation of European welfare states, the primacy of legislation and laws gradually receded to be supplanted by policy and policymaking, much better trimmed to continuous short-term adjustments in light of ever-changing situations and future perspectives (De Jouvenel, Citation1963, pp. 90–91). Laws and decrees lost their status as ‘trumps’ in the control of society, overriding policy considerations. Henceforth, they were merely ‘chips’ in the maelstrom of pragmatic policy considerations of social and economic control for the near future (Orren & Skowronek, Citation2017, pp. 41–43).

Thus, ‘policy’ and ‘policy process’ or ‘policymaking’ are concepts that, historically, reflect the way academic observes and practitioners in the West have understood ‘governing’ (Colebatch & Hoppe, Citation2018). This brought along an ‘epistemization’ of government. Originally, this became visible in the cameral sciences serving the mercantilist interests of absolute monarchs. Later, in the USA it developed in public administration as academic discipline (Wilson, Citation1887); and, in the immediate follow-up of the Second World War, even more strongly in the policy sciences (Lerner & Lasswell, Citation1951). This intellectualization of the governing process triggered a permanent concern among practitioners and academicians about the extent to which these novel policymaking practices were deviating from older practices of excercising power through the state apparatus. This question was framed as: to what extent is policymaking about ‘puzzling’ (‘how to think out policy?’), and skills and capacities for ‘knowledge use’ in ‘policy design’; or about ‘powering’ (‘how to fight about policy?’), i.e., agonistic activities and skills and capacities to do with political will formation in ‘policy agenda setting’ and ‘policy adoption’ and power in practices during ‘policy implementation’ (Lindblom & Woodhouse, Citation1968, 1993; Wildavsky, Citation1979).

This article is structured as follows. The introduction in this section is a brief discursus on the question: ‘how does governing and policymaking happen?’ The next section distinguishes between different types of contexts or conditions for public policymaking in the three Arab states researched.Footnote1 The third section explains the methods and the operational definitions of the main concepts in the study. A fourth section briefly explains the MSF and applies it to the domestic violence and wage adjustment issues in Lebanon, and explains the regimes-triad approach. A fifth section explains the ACF and deals with transparency issues in Tunisia. A sixth section applies the SCPDF and the regimes-triad approach to the issue of dealing with NGOs in Egypt. The final section provides conclusions and reflects on possible future research along the lines of applying Western-styled frameworks for contested politics and policymaking to Arab states.

Types of contexts and conditions for public policymaking

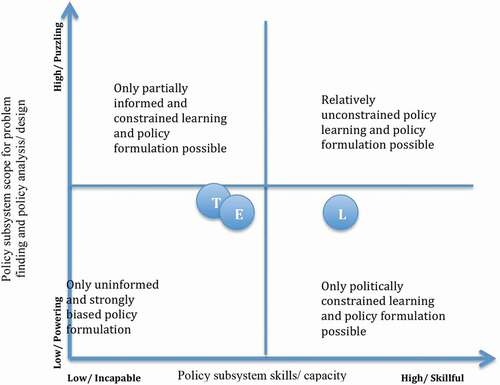

The question ‘how does governing and policymaking happen?’ always has to be answered in a specific context. Inspired by work of Howlett and Mukherjee (Citation2014), typical for contemporary ‘epistemized’ policy science, the notion of different contexts for policymaking can be elaborated into a typology of varying mixes of puzzling/powering, and high/low level of policy skills and capacities (see ).

First, on the vertical axis, is a policy subsystem’s scope for policy design, where the influence of puzzling and powering is roughly equal (puzzling ≅ powering), or where puzzling trumps powering (puzzling > powering). A ‘policy subsystem’ stands for all policy actors with sufficient influence and authority to make a difference in the practice of national policymaking in a particular policy domain (Sabatier & Weible, Citation2014); not just government actors like ministers, parliamentarians or officials, but people in non-governmental organizational positions and roles as well, like respected media personalities, other pundits, or NGO leaders. This actor constellation may be inclined more to policymaking as deliberation, consultation and collective puzzling (Heclo, Citation1974; Hoppe, Citation2011). Policy actors are free to learn from experience, domestically or even transnationally. And they may freely engage in policy analysis and means-ends design, whether this is merely incremental (considering small changes or patches to existing policies and implementation practices) or nonincremental (an innovative overhaul of policy doctrine, policy goals, implementation routines, and policy tools).

Contrariwise, policy subsystem actors may be inclined to policymaking as powering (powering > puzzling), i.e., participants see each other as adversaries, sometimes even enemies, locked in asymmetrically competitive situations. Even on designs for simple policy problems they do not seriously learn from each other through open consultation and debate; but instead engage in faking democratic and good governance procedures, bargaining, log-rolling, electoral opportunism, or clientelist or corrupt practices (Howlett & Mukherjee, Citation2014, p. 65; an excellent overview and analysis in; De Mesquita & Smith, Citation2012); not to speak of policymaking and implementation through systematically engaging in political crimes like illegal censorship, interfering with legal and judicial due process, creation of misinformation, and sometimes even systematically practicing torture and imprisonment of opponents or just noncompliant citizens in general (Ross, Citation2012; Sassoon, Citation2016).

On the horizontal axis, one can project knowledge, skills, and capacities for solid policymaking. High skills/capacities for public policymaking ask for political transparency like freedom of speech, assembly, academic freedom, freedom of conscience and religion (secularism), and of the press. A well-developed civil society and governance respectful of the rule-of-law also are necessary. In such conditions, people are free to apply their intellectual skills to political and policy issues. Jointly, they wield a wide spectrum of policy analytic methods and heuristics: at least in theory “(p)ublic or civic reason, in the liberal tradition, is a skill and a process available to everyone” (Edis, Citation2016, p. 168). Less developed policy skills and capacities result when the aforementioned conditions are insufficiently appreciated, resources are suppressed or simply non-existent. It is noteworthy here that strong anti-secularism impairs policy skills and competencies necessary for solid policymaking as puzzle-solving: “… if a policy proposal emerges from the demands of faith alone, it cannot persuade those who do not share that faith. Without persuasion, we are left with coercion – we invite violence, even chaos” (Edis, Citation2016, p. 168).

Research methods

This article reports on in-depth studies of four cases related to civil society activism that pertains to policymaking in three Arab countries. Each case starts by delineating the theoretical lens used to analyze the policy processes within a specific environment of policy skills and capacities. The article introduces and utilizes an innovative approach named the regimes-triad logic to critically analyze secondary data from the case studies. In the course of analyzing the Lebanese cases, this approach will be developed and elaborated. The article, hence, contributes to a better understanding of the specificities policymaking in the MENA region even though using western lenses.

Operationalization

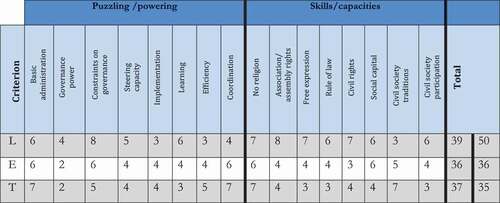

Operationalizing the typology of policymaking contexts for the case studies of Egypt, Tunisia, and Lebanon is possible by using the Bertelsmann Transformation Index data and scores as proxies, assuming these best represent the situation reported in the cases. Selecting proxy criteria for puzzling/powering oriented policymaking, and high/low policy skills and capacities at the national level, the countries are ranked as follows (see ). Returning to (p.4), the four types of policy formulation situations, and the positions Lebanon, Tunisia, and Egypt are shown in the typology on the basis of their BTI-2012 and for Egypt BTI-2018 scores. All these countries’ policymaking activities are undertaken in contexts where powering easily trumps puzzling; and where policymaking skills and capacities are relatively underappreciated or distrusted, with the possible exception of Lebanon.

Figure 2. Types of policymaking situation in Lebanon, Egypt, and Tunisia, 2012.

All case studies used a qualitative research design. Starting from document and time series analysis, and a careful reading of relevant secondary literature on political contexts, primary data were collected, where possible, through in-depth, unstructured élite interviewing; sometimes using Skype and Whatsapp when field conditions did not allow travel and face-to-face interviewing. Data analysis in all cases followed standard interpretive techniques (for detailed accounts see the sources mentioned in footnote 1).

Let us now turn to the details of the case narratives to illuminate policymaking practices in Arab states.

Contested politics and policymaking in Lebanon

The Multiple Streams Framework of policymaking

The two Lebanese case studies used the Multiple Streams Framework (MSF) as theoretical lens (Kingdon, Citation1995). The MSF draws attention to the “predecision public policy processes” that shape which issues arise onto the policy agenda and which proposals are likely to be taken up. The framework posits three ‘streams’ of policy activity which operate relatively independently: problems, policies, and politics. Contested politics, and the roles of social movements, civil society associations and domestic or international NGOs typically play out in the problem and solution streams, but take into account dynamics in the political stream as well. In the problem stream, the attention of people in and around government for a particular policy issue can be captured through focusing events (such as a crisis or a shift in the nature, size or visibility of a problematic situation), systematic indicators, or feedback on the outputs and outcomes of existing policies or programs. Kingdon describes the policy stream as a “policy primeval soup”: a constant flow of new, old and reframed policy proposals that are generated, floated and ‘tested’ amongst a community of specialists (including bureaucrats, academics, pundits and think tanks). While many proposals will be floated, successful proposals have to be technically feasible, anticipate budgetary and political constraints and fit with broader community values. The third stream is the political stream, which includes an array of factors such as public mood, turn-over in governments, electoral cycles, and interest group campaigns that shape what issues are likely to be deemed congruent with the political climate of the day.

According to the MSF, there arise critical moments—policy windows—when the three streams are joined, enabling policy change to occur. However, policy windows are infrequent and may open either predictably or unpredictably (and close just as quickly). Hence, policy entrepreneurs (advocates, inside or outside government, for particular proposals) through their problem politics are required to capitalize upon emerging opportunities in order to link the three streams: “they hook solutions to problems, proposals to political momentum, and political events to policy problems” (Kingdon, Citation1995: 182; but also Zahariadis, Citation2014). The likelihood of reform is inherently linked to events within the three streams, for example, if there is not an available or feasible solution the window may close. The heuristic describes a policy process that is complex, turbulent, non-linear, ambiguous and somewhat serendipitous.

Policymaking in Lebanon: discovering the logic of the regimes-triad

Lebanon’s policymaking is a paradox: it scores relatively well in competencies and skills, yet its policymaking is of low quality. Lebanon lacks a strong central state, an independent judiciary and, most of all, there is no monopoly over the use of violenceFootnote2. Lebanon is a society and polity deeply fragmented by religious-sectarian divides, even leading to civil war between 1975–1990. Since then governing Lebanon is an endless struggle between its Christian, Sunni and Shi’a political élites over ever-changing details in power-sharing arrangements. Moreover, these élites rely on external political support for propping up domestic power-sharing (Geukjian, Citation2017, p. 7). The long list includes Syria (until the Uprisings), Iran, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the US, France, and even Russia (Geukjian, Citation2017, pp. 4, 213). The externally dependent consociational, power-sharing nature of the political regime depends on constraints, not on incentives for cooperation (Horowitz, Citation1985). A spade of divisive policy issues creates constant discord and political instability: like Hizbullah’s pro-Assad support in fighting on the ground in Syria, and (armed) resistance to Israel, reform of the electoral system, and years-long paralysis of cabinet decision-making on policy issues of economic development and social justice.

Guelke (Citation2012, p. 41) observes that in deeply divided states politics and policymaking are “characterized by a lack of consensus on the framework for making decisions and by a contested political process in which the legitimacy of outcome is challenged …” The many veto-points inherent in power-sharing rules turn policymaking into a constraint-dodging nightmare; the need for virtual proportional representation that willfully ignores demographic numbers hampers governmental efficiency, and feeds non-democratic tendencies in decision-making. Moreover, policymaking may mean that actors have to ‘play chess on three boards’ at once. The first board is what in western policy process models and the MSF is assumed to be normal or routine: policymakers in the separate streams of problems, policies, and politics play a game, within domestic borders, governed by the goals-means logic, i.e., the logic of designing a broadly supported solution to a policy issue. This may be called policymaking according to the logic of the policy issue per se—the issue logic.

But in deeply divided countries with consociational or power-sharing arrangements, there is a second chessboard. Here the game is one of the competitive clientelism; shifts in relative power between societal and political groupings have to stay within the bandwidths indicated by the power-sharing rules; and any proposed policy solution has to stay within the boundaries of the national regime logic, i.e., the concern that social cleavages in society do not burst decision-making structures that enable the taking of authoritative decisions—in other words, the necessary conditions for a political regime to keep existing and not disintegrate. If upholding the domestic regime logic requires constructive intervention by external guarantors, like in the case of Lebanon, there is even a third chessboard, an inter- or transnational regime logic, to do with inter- and transnational games of geo-economics and -politics.

Thus, policymaking becomes a three-level game, where interdependent logics of the policy issue, the domestic political rules and institutions, and the inter-or transnational regime of which the country is a part, jointly constitute a three regimes-triad. Although the three regime logics for policymaking should not be thought of as hierarchically ordered, it is frequently the case that players in the lower-order policy games can only make particular moves if windows of opportunity open up in the higher-order national and international political games. But it will be shown in this article that players in the issue logic may cleverly exploit opportunities for policymaking resulting from the political system’s exposure to an international regime.Footnote3 It is clear that given its turbulent and deeply uncertain political situation, policymaking in Lebanon is a convoluted, complex and confusing process of patient constraint-dodging and efforts to create and swiftly use brief windows of opportunity. This is in itself a plausible reason to apply the MSF to Lebanese policymaking as the framework is considered applicable under conditions of turbulence, high ambiguity, and uncertainty.

Domestic violence against women in Lebanon: KAFA’s issue logic exploits the regime logics

The policymaking and legislative process resulting in Law 239 to protect women against domestic violence played out between 2008–2014, a time of severe political instability and self-paralysis (Geukjian, Citation2017, pp. 176–273). The consequences of the assassination, attributed to Syrian security agents, of Lebanese popular prime-minister Hariri in 2005, and after 2011 the consequences of the Arab Uprisings in Syria, posed existential threats to Lebanon as a political entity. This situation underlines the outstanding success of KAFA (meaning ‘Enough’) in getting Law 239 adopted at all! Together with Lebanon’s 2005 ‘Cedar Revolution’, where one-and-a-half million Lebanese demanded sovereignty, democracy and an end to foreign meddling in national politics (Bayat, Citation2013, p. 6), KAFA represents a kind of ‘model’ for the possibility of civil society organizations’ effective political influence after the Arab Uprisings. Several factors contributed to this story of exemplary performance.

First, over the course of six years KAFA managed to combine policymaking roles that in western models are functionally differentiated: ‘campaigner’ (mobilize and orchestrate the campaigns of women associations and NGOs, and media campaigns, in manifestations of contentious politics), ‘broker’ (bridging the normal confessional-sectarian cleavages and building a quasi-nationwide social movement, a truly exceptional feat in a country whose politics is permeated by sectarian clientelism), ‘advocate’ (constantly lobbying for policy reform with professional, political, bureaucratic, governmental and ecclesiastical authorities), ‘policy designer/legislator’ (mobilizing necessary legal, medical, social, professional and political expertise to draft a comprehensive, well-reasoned bill), and ‘policy entrepreneur’ (probably with the help of sympathetic political insiders, cunningly waiting for a fortuitous constellation of national and international political forces to push an otherwise paralyzed government and parliament to adopt the bill).

Why did KAFA succeed? Civil society actors in Arab countries, like KAFA, attempt to bypass the suffocating role of political parties and assume their function as mobilizing and selecting the needs and demands of ordinary citizens and transforming them in government policies. In Lebanon, although somewhat more free and democratic than other MENA states, the role and function of elections, political parties and parliament are rather different than in consolidated democracies. They are public spheres, but rather than holding government accountable, they are tools for parties and their ministers or presidents to justify their power-sharing rule. In Lebanon, elections (if held at all and not time and again postponed by parliament and the Council of Ministers) cannot change the relative power of the major political parties that are actually umbrellas for confessional-sectarian pillars. Where such pillars have more than one political party (e.g., Hizbulla and Amal in the Shi’a pillar; or Free Patriotic Movement and Lebanese Forces in the Christian pillar), elections merely record shifts in voters’ support between these parties. Parties usually have no clear ideological or policy platform, they are mere aggregation machines for people identifying as members of a confessional sect. The implication is that political parties and governments are more interested in gathering the spoils of governing and allocating (parts of) them to their clients. Thus, maintaining existing and developing new clientelist practices—following the domestic regime logic—easily trumps substantive interest in policymaking as issue logic. Usually then, civil society actors as one-issue, sect-based clientelist or interest groups fail to attract sufficient attention of parliament and government for nation-wide new policy initiatives. For example, although the “I stink” rebellion united citizens ‘en masse’ in weeks-long protests against the government’s gross negligence and corruption in handling the garbage and waste disposal crisis in Beirut, in later municipal elections voters fell neatly into sectarian lines again. Obviously not for nothing it is argued that in Lebanon people as citizens are on their own and helpless, but as members of a sect they are eligible for support in matters such as education, health, and jobs.

KAFA succeeded precisely because it combined normally differentiated roles. As policy entrepreneur KAFA managed to harmonize the problem, solution and politics streams by exploiting an opportunity for applying strong political pressure provided by the domestic regime logic of power sharing. The Lebanese constitution required a discordant, paralyzed (since July 2013) parliament and Council of Ministers to elect a new Maronite president before May 2014. Since prospects of meeting the deadline were negligible, parliament and government were willing to consider acting on any broadly supported issue that was ‘harmless’ enough from the point of view of the national or international regime logics. This institutionally contrived political situation KAFA cleverly turned into a policy window. This was possible because the number and nature of issues in the problem stream were favorable for the domestic violence issue. The only other issue seriously bothering Lebanese politicians was conferring Lebanese nationality to children of women married to non-Lebanese men. Like in many other Arab states, national law prohibits this, even though international law condemns such restrictive nationalization policies as violating a child’s universally accepted political right to citizenship; usually connected to social rights like education and health care. At the time this issue was explosive for Lebanese politics. Memories of civil war caused by (among other things) uncontrolled influx of Palestinians, a large Palestinian segment still living in the country, and, most of all, the ongoing influx of Syrian refugees—all of these made a new nationalization law in conformance with international law anathema. Thus, the turbulences in the international regime left the domestic violence bill as a last chance and opportunity for parliament and government to show at least some political effectiveness to citizens. After KAFA, as campaigner, timely organized a mass rally to stress once more the urgency of the domestic violence issue, as policy entrepreneur she pushed government to allow the bill she had proposed as policy designer and legislator to be put on the decision agenda. In other words, KAFA showed skillful tactics in what the MSF calls problem politics to create and exploit a policy window.

But the moment the issue became a matter of formal governmental decision-making procedures, KAFA’s success story turned out to have a downside. Due to parliament’s majority opinion about value acceptability to public opinion of the bill, sensitive parts like child custody and marital rape were removed from the final proposal. And since domestic violence still also belonged to citizens’ personal status, trying such cases fell to the religious courts of the 18 Lebanese sects; possibly supported by the Courts of Urgent Matters. Both judicial institutions were known to be short of skilled personnel and financial resources. Police training on how to deal with domestic violence incidents was only possible on a piecemeal basis. Thus, MPs deliberately watered down the spirit of the new law by ignoring matters of technical feasibility and resource adequacy (parts of the policy stream in MSF) of the law’s enforcement and implementation. The policy became the umpteenth case of dramaturgical incrementalism on women issues in the Arab world: ‘big leap’ policy reform for a spectator public vulnerable to symbolic reassurances, but at best slow-pace and long-run incremental change during implementation practices by under-resourced, under-educated, and understaffed institutions (cf. Saadi, Citation2019).

Once Law 239 was adopted, another weakness of KAFA manifested itself. External funding stopped, and the organization started to fall apart. Also, different NGOs and organizations claimed to be the ‘owner’ of the legislative success. Instead of an incentive for continued cooperation, sectarian clientelism reasserted itself. The high level of network integration (a property of MSF’s policy stream), which had always been one of KAFA’s strengths, turned out to rely less on bottom-up support from domestic volunteers, but more on external, non-Lebanese funding. Hence, implementation monitoring and goal achievement evaluation, two follow-up tasks for active civil society organizations, did not occur to a significant extent. In other words, important ingredients of a domestic issue logic were not in place due to the national and international regime logic impinging on the issue.

Wage adjustment policy in Lebanon: regime logics constraint and subordinate issue logic

The regimes-triad logic also illuminates why, in 2011–2012, an innovative, ‘social justice’ wage proposal by the Minister of Labor, Nahas, that would have benefitted most of Lebanese salaried workers, was quashed, with the surprising support of the labor unions, by a very incremental wage adjustment proposal by Prime Minister Miquati.

According to Article 44 of the Lebanese Code of Labor, “the minimum pay must be sufficient to meet the essential needs of the wage-earner or salary-earner and his family.” According to Article 46, “the minimum pay assessed shall be rectified whenever economic circumstances render such review necessary.” Law No. 36 of 1967 stipulates that the government is to periodically set a minimum wage and to define the increase of living costs and its implementation, while Law No. 2000/138 stipulates an annual wage adjustment. Nevertheless, since the 1990s the 1967 Law was not applied in the wage adjustments of 1996 and 2008, and in 2011 the average wage was low when compared to the cost of living, while significant inflation had lowered the real wages of employees. This clearly shows how in Lebanon law is not enforced consistenly. Politics is above the law; political legitimacy overrides legality and rule-of-law: “Legitimacy is derived from the extent to which it reinforces coexistence among religious communities, much less from compliance with law and human rights” (Hamd, Citation2012).

Like many other politicians, Minister of Labor Nahas used the law opportunistically as a tool to justify and support putting a particular policy issue, a social-justice system for wage policy in this case, on the parliamentary and governmental agendas. The policy solutions of Nahas stemmed from his nonincremental policy reform perspective: a “social wage” which seriously addressed questions of equity and fairness. These solutions demanded an evidence-based wage increase in accordance with official data indicators and legal provisions. Patient constraint dodging and swift action to use short windows of opportunity was also apparent. After more than a decade, Nahas revived the ‘sleeping’ Price Index Commission (PIC) as a major venue of policy design in the issue logic sense of the word, stating that “we are trying to act now in order to benefit from a temporary opportunity”. During the third PIC meeting on November 11, 2011, Nahas urged the members to swiftly present their views and proposals on the matter, in order to be able to draft a proposal and present it during the next Council of Ministers’ meeting.

Hurry was needed because he knew that there existed a rival policymaking venue, initiated and orchestrated by Prime Minister Miquati, who pushed another ready-to-go, minimal wage adjustment policy option: safeguarding the existing, ad-hoc wage policy arrangement, aimed at preserving the status quo and to re-activate wage policy schemes previously applied in 1996 and 2008. This proposal was not evidence-based and expert-advised, but reflected a political deal with the labor unions (politically paralyzed by divisive political party influences) and the business lobby. Another reason for hurry was an imminent turn in the political mood of the population at large. The onset of the wage policy process coincided with the outbreak of the Syrian crisis in March 2011. At this point, the government and citizens began to be alarmed by the influx of Syrian refugees.

To cut a long story short, the wage hike policymaking process ended in defeat for the Nahas reform (Nahas had to resign, eventually) and victory for the Miquati minimalist adjustment proposal. For a number of reasons, this was an absurd, hard to understand outcome. First, the labor unions sided with the business lobby in supporting a deal offered by the Prime Minster, and opposed a better deal of the Minister of Labor, who was not only offering a higher wage increase, but a package deal including elements of a social safety network. Second, although the Christian Free Patriotic Movement (in coalition with Shi’a political parties Hizbolla and Amal) had supported Nahas’ proposal only a few months before, in the end they voted against the proposal by Nahas, a minister affiliated with that same coalition, thereby allowing the approval of the deal by their political rival, Miqati (a Sunni Prime Minister). Third, Decree 7426 (the official name for the Miqati proposal) was passed despite a judicial review by the State Council which clearly declared it illegal for several reasons, including that it was not based on an updated cost of living index justifying the wage increase as per Law 36/67.

The MSF argues that the success of a policy proposal crucially depends on the skills of policy entrepreneurs in the game of problem politics. They have the ability to use, or by imaginative manipulation tactics even create, windows of opportunity where the three streams—problem, policy and solution streams—converge, a vital condition for policy proposals to be adopted and implemented. Nahas and Miqati were about equally skillful and powerful policy entrepreneurs; yet Miqati ‘wins’, and the political coalition of which Nahas is a prominent representative, suffers the humiliation of a double defeat: not only does his own coalition eventually vote down his proposal, but also he has to resign. How was this possible?

The only possible explanation of this perplexing result is by invoking the regimes-triad of policymaking. Although the MSF framework usually limits itself to the domestic policy issue logic, the logic of the regimes-triad can be accommodated in the MSF as shaping the problem politics that allows policy windows to occur. In Lebanon, the coupling of the three streams does not merely depend on the issue logic of the policy problem in question; it also depends on the rules of the domestic regime logic. The regime logic is a long-lasting system of power-sharing among three ruling élites of Christians, Sunnis, and Shiites. Because of the rule that the president should always be Maronite, the Prime Minister a Sunni, and the speaker of the parliament a Shi’a, the system creates predictable windows of opportunity for these three political top-jobs. Whoever holds one of these power positions, or in the future has the prospect of getting one, becomes a kind of ‘godfather’ who, because he (he is always a male) has (or will have) veto power, can trump any and all short-term policy considerations (issue logic) of policy entrepreneurs, in favor of longer-term power considerations to keep the system of consociational and sectarian clientelism (national regime logic), in its dependency on a transnational temporary order (international regime logic), going.

It is well known that such institutionalized, predictable windows of opportunity facilitate spill-over and issue-linkage attempts that may have nothing to do with the original policy issue. But because they are counter-factual, they are hardly empirically researchable. In this case, there are two more or less plausible but speculative scenarios.

The first scenario links presidential succession to the wage issue. As was shown in the KAFA-case already, in 2012 Lebanon, in a highly unstable situation and with a paralyzed government, the power-sharing constitution nevertheless stipulated that in 2014 President Suleiman ought to step down and a successor be elected by parliament. Predictably, due to virulent political discord about electoral law reforms, there would not be new elections before that time; hence relative power relations in parliament were stable. Also predictably, the next president had to be a Maronite; and he had to be acceptable to the politically strong Shia-segment of Lebanon represented in the Council of Ministers, i.e., Hezbollah and Amal. Domestic regime logic thus clearly pointed to the FPM’s leading politician, ex-general Aoun (Nahas’ political ‘boss’), who had sided with the pro-Syria 8 March camp, as a plausible, even promising candidate. Given that Lebanese presidents need the political approval of external guarantors, Aoun also had to look good from a transnational regimes logic. It was to be expected that an Iran–Syria–Hezbollah partnership would still be a strong force in the geopolitical matrix of the Middle East in 2014; and being a Maronite, Aoun might well be passable (by lack of another plausible candidate) to the counter-pact of the US–Saudi Arabia–Israel. All of these forces together created a problem politics where a ‘godfather’ could override the considerations of policy entrepreneurs and link the presidential succession issue, still two years in the future, to the 2012 wage hike issue.

Another somewhat less plausible scenario is that in exchange for accepting defeat on the wage hike issue, FPM was promised more influence on other labor-related issues, especially involving civil servants and teachers. Normally any FPM initiative in these domains would be hit by vetoes from the Sunni Free Movement party and the Shiite Amal party. Irrespective of which scenario is the more likely one, the wage hike issue was settled according to Miqati’s minimalist wage adjustment proposals; Nahas’ reformist social justice wage plans were buried, and Nahas himself had to step down, knowing his issue logic had been sacrificed to the national and transnational regime logics as perceived by a majority of his fellow ministers and members of parliament.

Policymaking in post-Jasmin Revolution Tunisia

The Advocacy Coalition Framework

The next case study used the Advocacy Coalition framework (ACF) as conceptual guidance. This framework was developed in the late 1980s/early 1990s; however, it continued to evolve under the influence of new theorists and new case studies (Sabatier & Weible, Citation2014). The ACF depicts the policy process as an adversarial competition over policy proposals, whereby actors in a particular policy domain (the policy sub-system) coordinate with allies to form “advocacy coalitions” that share core values and beliefs and then compete with each other in order to try to get their views translated into governmental policy. The ACF states that each policy arena may involve up to five coalitions, although researchers have found most policy sub-systems contain only two, in line with practices of parliamentarian democracy that normally produce binary divisions between a government supporting and opposing coalition. Coalitions draw upon the resources that are available to them, such as legal authority, public opinion, information or research, as well as venues such as media, courts, and legislatures on the state, regional and local levels in order to try to get their views adopted.

According to the ACF, actors and advocacy coalitions are driven by three types of beliefs (Jenkins-Smith, Nohrstedt, Weible, & Sabatier, Citation2014). The broadest are “deep core beliefs” that are ontological beliefs about the world and society (e.g., the importance of individual rights). The next level is “policy core beliefs”, which are normative and empirical beliefs about a specific policy arena (e.g., gender-related issues like marriage rights), including its framing and how serious a problem is, its causal structure and the preferred solutions for dealing with it. The third and most specific level is “secondary beliefs”, which pertain to instrumental considerations about how policies should be implemented or resourced. The ACF contends that deep core and policy core beliefs tend to be highly resistant to change, but that secondary beliefs frequently change, in response to a changing circumstance (Sabatier &Weible, Citation2014, p. 124).

Since actors in a particular policy domain (the policy sub-system) coordinate with allies to form “advocacy coalitions” and their policy beliefs are resistant to change, the line-up of allies and opponents around specific policy issues (and their beliefs and arguments) tends to be stable. However, either events outside of the policy sub-system or policy-oriented learning can increase opportunities for policy change (Jenkins-Smith et al., Citation2014). External events or perturbations such as major socio-economic change or an unexpected election result can shift the power balance between coalitions, shift resources and open or close available venues. The shake-up of power/resources/venues may enable major change in a policy response, such as via a new coalition becoming dominant. Another avenue for change is policy-oriented learning, defined as learning over long periods of time from the gradual accumulation of information, such as scientific research, policy analysis, and experiences of various local stakeholders. Policy-oriented learning tends to lead to changes in policy implementation rather than change in an overall policy. A further avenue for change is a “hurting stalemate”: whereby all parties involved in the dispute view a continuation of the status quo as unacceptable and come to a negotiated agreement. From this very brief summary, it should nevertheless be clear that the ACF generally presupposes a policymaking process where, barring strong external shocks, puzzling trumps powering through policy-oriented learning, or where puzzling and powering are in some form of equilibrium. This should not come as surprise because the ACF was originally designed to improve understanding of the role of knowledge and science in the policy process.

Transparency of state revenues and allocation in Tunisia: unstable regime logics frustrate issue logic

Eight years after the Arab Uprisings, catalyzed everywhere by the self-immolation of a Tunisian citizen, Tunisia is the only MENA country where spontaneous public debate in squares and streets may still be witnessed. After its ‘Jasmine Revolution’, Tunisia managed to avoid re-islamization as originally envisaged by the Ennahda party, and stave off extremism. It gained fragile political stability and democracy through a (Nobel Peace Prize 2015 winning) national dialogue in which political parties, the national labor union, the bar association, and many civil society groups all participated. Nowadays, the country is governed by a secular political party (Nidaa Tounes) and a secularized Islamic party, Ennahda. Nida Tounes was led by Beji Caid Essebsi, who served as prime minister under presidents Bourguiba and Ben Ali, and who ran an anti-Islamist agenda and pledged to restore order, and became Tunisia’s first elected president.Footnote4 Ennahda, unique in the MENA world, evolved into an party of Muslim democrats, committed to moderation, allowing a new 2014 constitution not to mention the Koran or Shari’a anywhere.

Tunisia finds itself in a “post-revolutionary transition … where authoritarian, deep-state structures and practices remain intact while the political system is in a state of flux” (Martin, Citation2018, p. 28). The political regime is in deep uncertainty and turmoil. The political élites appear deadlocked in power struggles, unable to agree on appointees to the constitutional court and an electoral commission; nor able to reform the civil service (growing since 2011 to appr. 700.000 civil servants), or to create sufficient jobs for people without ‘connections’, or reform the old public subsidies for food, gas and transportation. All in all, Tunisia’s political and economic élites have been preoccupied more with internal power struggles than responding to grievances of its citizens. As part of clinging to political power, élites have been holding on to their monopoly over the country’s natural resources, especially those originating from Tunisia’s state-owned extractive industries for petrol and phosphate.

It is for this reason that in 2014 CSOs and other oppositional forces have joined forces in a very broad anti-status quo ‘coalition’, “La Coalition Tunisienne pour la Transparence dans l’Énergie et les Mines” (CTTEM), under the banners of transparency, accountability and good governance. Decree Law 88 granted legal freedoms to CSOs, even international NGOs. This created a new political opportunity structure by opening up a previously closed policy subsystem dealing with extractive industry issues. In the past, this policy subsystem consisted only of the state-owned enterprises themselves, governed, without any democratic or legal accountability, by the Ministry of Industry and Mines and the Prime Minister’s Office. The new constitution brought with it a new issue logic because it now stipulated parliamentary approval of publicly available, publicized contracts.

Interestingly, international regime logics helped bring this about. Tunisia joined the international Open Government Partnership (OGP). The national OGP Action Plan for 2016–2018 includes the government’s commitment to join the international Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). Since then, EITI’s Resource Governance Index has become the main tool that the CTTM has wielded to push the government to adopt governance reforms. In its turn, CTTM was assisted in its consultation- and design-based policymaking efforts by INGOs, like the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI), Publish What You Pay (PWYP), and I-Watch. The international NGOs in fact function like policy brokers and policy entrepreneurs combined (Capano & Galanti, Citation2018). They push for more frequent and routine consultation between government actors like government officials known to be sympathetic to the transparency cause, and the much more ambivalent MP’s in the Energy Committee of the Tunisian Parliament.

The more informal anti-status quo forces consist of a ‘front’ of ever-changing protest movements and organizations. They focus on transparency and accountability issues as well, but mobilize around specific or local allocational issues, like more transparency in recruitment of workers for the companies in particular districts, or allocation of state revenues to district governments for improving local infrastructure or employment. These protest organizations almost constantly resort to strategies and tactics well known in the contentious politics literature, like strikes, mass demonstrations, sit-ins, etc. (Martin, Citation2018, pp. 11-12).

To some extent, this broad transparency coalition-plus-action front has been effective. It successfully pushed for the government decision to publish the oil and gas contracts (June 2016), and it keeps up the pressure to follow up on the national commitment to fully join EITI, and to increase corporate social responsibility of the state-owned enterprises in stimulating regional and local sustainable development. Even though stricter conditions so far deterred the government from making true its commitment to join EITI, the country’s ranking on the global Resource Governance Index has improved (Martin, Citation2018, p. 16).

However, the obstacles for real policy change remain formidable. First, there is the game of ministerial ‘musical chairs’: (Martin, Citation2018, p. 22) frequently changing ministerial portfolios and key figures (high-level civil servants and ministers alike) makes it hard to build relationships of trust that allow collective policy learning between government and non-governmental actors. Second, the state-owned companies themselves have double loyalties: commercial and political, and both appear marred by corruption and embezzlement (Martin, Citation2018, p. 23). Third, politicians and civil servants are not consistent advocates of more transparency because they believe it could slow down foreign investment and thus economic growth. IMF and World Bank are willing to ‘help’ by providing new loans, but only in exchange for unpopular austerity measures. This economic argument is important, because as a senior MP from a secular party stated: “There haven’t been any reforms.… The only thing we’ve done is gotten into debt. The country is adrift. We’re playing it day by day.” (New York Review of Books, 12 April 2019)

Fourth, and related, there is clearly a lack of will or a political stalemate (Martin, Citation2018, pp. 24-5). In view of the political competition in an uncertain and turbulent domestic and international political environment, politicians are unwilling to ‘cut the knots’. Although the ACF conjectures that a hurting stalemate could be a cause for real policy change, in Tunisia the jury on this hypothesis is till out. Finally, transparancy, accountability, and good governance rely on minimum levels of mutual trust— between politicians among themselves, between politicians and civil servants, between government and nongovernmental experts, between government and citizens, and amongst citizens themselves. During the dictatorship period trust was completely eroded. Rebuilding it is, by definition, a very gradual process of culture and mentality shift. Although it is true that “people cannot eat stability”, keeping the country politically stable is a precondition for regaining trust.

In the Tunisian case, the logic of the regimes triad makes for an entangled actor network in apparent paralysis. The ‘refolution’ (Bayat, Citation2013) ushered in new actors and a new constitution. This resulted in remarkable changes in the policy issue logic in the extractive industries policy domain. Originally, a novel international regime, EITTI and its global Extractive Industry Transparency Index, pushed a new transparency mentality and discourse, both in selective parts of government and parliament, and in an anti-status quo coalition of CSOs. INGOs like NRGI and PWYP offered capacity building and skills training, and played a kind of policy brokership-cum-entrepreneurship role. Although the INGOs, like policy entrepreneurs, did support the policy change advocated by the anti-status quo coalition and in that sense were not neutral; like brokers, they did insist on fostering trust relationships with friendly ministers and civil servants, and pushed for regular consultative relationships. Real policy change, and the lack of it, is the result of a national regime divided against itself: old habits of opacity, deep-state practices, corruption and embezzlement in both government and state-owned companies, against new impulses for transparency, open government, open data platforms, and more corporate social responsibility. How long this interregnum, in which the old refuses to die and the new cannot be born (Gramsci, Citation1930, 1999, pp. 32–33), will last is hard to predict. Experiences of political chaos and deep economic depression in Russia during the Gorbachev and Yeltsin years, as well as in Egypt where the army ousted Muslim Brotherhood rule, teach us that there comes a moment where people start preferring order and the prospect of some economic gains over the political drive for transparency and democracy.

Governing NGOs in Egypt: regime logic dictates issue logic

Social Construction in Policy Design Framework

The Social Construction in Policy Design Framework (SCPDF) informs data collection and analysis of this case study. The framework belongs to the so-called policy feedback type of policy process theories. Their core is the thesis that politics not only frames and pre-structures policymaking, but policy implementation and outcomes feed-back into the shape of politics as well (Lowi, Citation2009; Pierson, Citation1993). The SCPDF framework was developed to better understand “… why some groups are advantaged more than others … and how policy designs can reinforce or alter such advantages” (Schneider & Ingram, Citation1993, p. 334). Thus, contrary to the ACF, and more than (implicitly) the MSF, which assume policymaking to focus merely or largely on the policy issue logic, SCPDF incorporates the explicit assumption that, also in the West, public policymaking may have spill-over effects to the domestic or national regime logic; in this case adverse impacts on citizens’ trust in government and the quality of democracy.

By asserting that group traits are socially constructed, Ingram and Schneider (Citation2005) do not suggest that “factual distinctions are somehow made up … the facts of group characteristics may be real, but the evaluative component that makes them positive or negative is the product of social and political processes” (Ingram & Schneider, Citation2005, p. 3). SCPDF illuminates how policy designs shape the social construction of deservingness of a policy’s targeted population, and of their perceived power, and how policy design “feeds forward” to shape future politics and democracy (Pierce et al., Citation2014, p. 2).

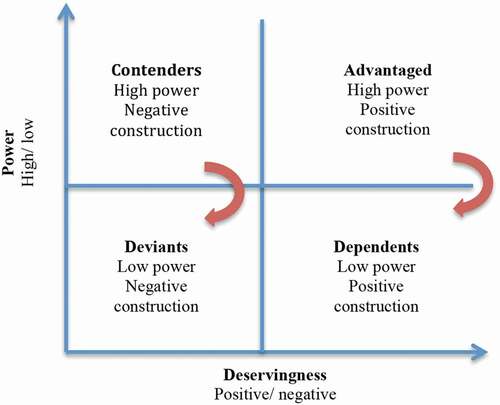

The theory has two core propositions: First is the target population proposition: depending on positively or negatively socially constructed, perceived properties of target groups, the ratio of benefits/burdens from policy programs will differ: “Policy designs structure opportunities and send varying messages to differently constructed target groups about … how they are likely to be treated by government.… The allocation of benefits and burdens to target groups depends upon their extent of political power and their positive or negative social construction on the deserving and undeserving axis” (Ingram, Schneider, & de Leon, Citation2007, pp. 98–101). summarizes the classification of target populations as indicated in this proposition. According to this classification, the advantaged are expected to receive a disproportionate share of benefits and few burdens. Contenders are expected to receive sub-rosa benefits and few burdens that are highly visible but easily undermined. The dependents are expected to receive rhetorical and underfunded benefits and few but often hidden burdens. Finally, deviants are expected to receive limited to no benefits and a disproportionate share of burdens (Schneider & Ingram, Citation1993).

A second core proposition of the SCPDF is the feed-forward proposition: these different benefit/burden ratios will influence target groups’ future behavior, especially its attitude towards government. In doing so, the regime logic of consolidated democracies may be impaired. The SCPDF leaves room for assuming and exploring the potential role of media during the policymaking process. Media-related assumptions that relate to the social construction of a policy’s targeted population’ trajectory inform the investigation in this case study of dealing with NGOs in post-Uprisings Egypt.

Mediating governmental policy design and taming NGOs in Egypt

Traditional media may be viewed as important policy actors in a policy subsystem. In this case, the role of Al-Ahram, a state-run newspaper, is a tool for both promoting Egypt’s government policy, and providing feedback about NGO-related policies. The main proposition tested here is the ‘target population proposition’. Data collection builds on content analysis of Law 70 of 2017 on NGOs in Egypt, and a thematic framing analysis of state-run news media articles.

In the months following Mubarak’s resignation in 2011, there were hopeful signs that Egypt might achieve enduring democratic reform. The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), which assumed control of the government until elections could be held, presided over an Egypt in which civil society was at its zenith and the independent media were rapidly expanding. Dozens of news outlets and hundreds of NGOs, trade unions, political parties, and coalition groups were established. Revolutionary activists, NGO leaders, and artists were dominating the public sphere (Mansour, Citationn.d.).

At present Egypt’s independent civil society organizations (CSOs) face the most repressive environment in decades. Historically, autocratic governments in Egypt have selectively used civil society restrictions to ensure civic mobilization did not cross the rulers’ red lines. In contrast, Egypt’s new government undertakes a much more comprehensive campaign to deliberately shrink civic space (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Citation2017). Its tactics include (1) the criminalization of public dissent in the name of national security and counterterrorism, (2) the use of legal reforms and decrees to institutionalize previously extrajudicial repressive practices, close existing loopholes, and tighten security sector control over civil society, and (3) targeted harassment and defamation of Egypt’s leading human rights activists and organizations.

The broad definition of national security is in keeping with other measures put in place in recent years, including a draconian NGO Law (Aboulenein, Citation2017), and anti-terror provision (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Citation2017) that contribute to the weakening of freedom of expression and civil society, facilitate human rights abuses, and to increase immunity for state authorities that stifle dissent (Miller, Citation2018). More brutally than in the other cases studied in this article, policymaking as powering muffles puzzling. One could even argue that the powering inherent in a garrison state’s regime logic fully dictates the puzzling allowed in its issue logic.

The target group proposition predicts that elements of policy design (especially the policy tools and the policy rationale) will differ depending on the social construction of deservingness and political power of the target population. At first glance, it seems that various policy tools of Law 70 of 2017 impose all-encompassing, identical burdens on all NGOs. A closer look, however, reveals that they impose burdens on and grant benefits to NGOs that vary according to their deservingness and level of power. For example, the law employs different tools to deal with receiving funds. While imposing limitations on associations’ access to domestic funding (Article 23), the law prohibits any receiving of foreign funds, donations, and grants—whether from outside Egypt, or from foreigners inside Egypt—without approval from the National Agency to Regulate the Work of Foreign NGOs (Article 24).

This distinction in the scale and level of tools draws the line between (national) development NGOs and other advocacy organizations. In fact, Law 70 expressly limits the activities that CSOs may engage in. Associations and foreign NGOs are restricted to activities “in the fields of development and social welfare” (not further defined), and the activities must align with the state’s development plan and priorities (Article 14). It is clear, hence, that “only human rights and political reform organizations [face] the full weight of the [NGOs] law.”Footnote5 This implies that advocacy organizations are negatively constructed as source of threat to the nation-state. It also implies that these NGOs are perceived by the state as ‘powerful trouble makers’ who require heavy policy tools for regulation and control. These attributes, hence, place advocacy organizations in the ‘contenders’ position.

Concurrently, developmental NGOs are positively constructed, powerful groups. On the one hand, they function within the policy scope permitted by the state and they refrain from getting involved in politics. On the other hand, they possess resources and expertise and are often described as appendages of the state bureaucracy. Although tools might seem burdensome to these organizations as well, yet “when burdens, rather than benefits, are directed at the advantaged groups, the tools will be less predictable and more likely to change; … self-regulation that entrusts the group to learn from its own behavior and voluntarily take actions to achieve policy goals will be preferred along with positive inducements” (Schneider & Ingram, Citation1993, p. 339). It is worth noting that by implementing such policy tools by Law 70 of 2017, power to ‘contender’ NGOs is strongly diminished, pushing them into ‘deviants’ status. Developmental NGOs might remain powerfully ‘advantaged,’ or descend to ‘dependents’ position according to the resources they possess and the partnership relations they build or maintain with the state. delineates the suggested shift in designation of deservingness to different categories of interest groups (NGOs).

Framing analysis of the Al-Ahram state-owned newspaper confirms this line of thinking. “The regime perceives the media as a tool for moral support, with its primary role being to prop up the country’s leader” (Kassem, Citation2016). State-run media act as government mouthpieces and practice self-censorship to make sure they do not cross the red lines (Youssef, Citation2015). Newspapers such as Al-Ahram till this day are run as public mobilization tools whose essential role is to justify, explain and endorse the regime’s policies (El-Amrani, Citation2005).Footnote6 In this case, state-run media are well situated in the policy sub-system not to debate policy making, but instead engage in faking democratic and good governance procedures. They are not engaged directly in the making of policy, but rather are utilized by the government as tools for justifying the to-be approved or already imposed policy. In this sense, state-run media function as ‘policy mediators’ that might contribute to stabilizing the policy environment during the making of and post-approving a barely debated, hardly accepted policy.

The research provides empirical evidence for the presence of a ‘risk’ and ‘opportunity’ frame in national press coverage of the recently enacted Law 70 of 2017 on NGOs. NGOs are dichotomously portrayed as either imposing risks, i.e., threats to the nation-state and its security, or creating opportunities for development. This concept of valenced frames has a strong theoretical foundation in prospect theory (Tversky and Kahneman, Citation1981). Two-fold policy rationales were presented in the press to legitimate policy goals, the choice of target populations, and policy tools.

For relatively powerful, positively viewed developmental NGOs, the rationales commonly featured the group’s instrumental links to the achievement of important public purposes, currently conceptualized in terms of national defense and economic competitiveness. Emphasizing the efficient role that developmental NGOs could (and should) play as a partner in the national development plan, media frames have justified legally induced ‘active inclusion’ of NGOs in the developmental process: “Efficiency as a means for achieving the instrumental goals of policy will be emphasized as the reason for the selection of [this] particular target group and particular tools” (Schneider & Ingram, Citation1993, p. 339).

For contending NGOs (those that are powerful but have negative constructions as risks), the rationale was sharply different. As they received burdens, the public rationale overstated the magnitude of the threat or risk, and interpreted it as a correction for their greed or excessive power. In the current situation where the burden is real, advocacy NGOs were led to believe that they abused or overestimated their power, or made errors in their strategies. They were told that the policy was inevitable once public attention was directed to their privileged, but irresponsible conduct. In a ‘war on terrorism frame’, they were blamed for threatening national security. Using this frame, the need for legally induced ‘active intrusion’ by the state was presented and justified. It could be said, hence, that the target population of Law 70 of 2017 is being deconstructed by the tools and rationales of the law. Its purpose is the creation of a docile civil society, with little incentives and capacity for feeding forward for a new (or amended version of the) law.

The findings support the thesis that autocratic states, like Egypt, are characterized by a strong and clearly visible distinction between issue and regime logics. For example, in recent research on systems of policy advice in Russia, Belyaeva (Citation2019, p. 14) found an ‘economic’ and a ‘political’ bloc. The advisors in the economic bloc were allowed to follow an issue logic of economic development and modernization, but within ‘red lines’ dictated by the regime logic of the political advisers. These advisors, in Belyaeva’s words, were concerned with “preserving and reproducing the regime”, by advising on topics such as methods of selecting reliable political candidates and keep unreliable ones from running for office, less visible methods for advantaging the political party ‘in power’ during electoral campaigns, “international experience of limiting electoral rights” and “experience of developed countries on the transformation of electoral systems …” (Belyaeva, Citation2019, p. 9–10). In this way, the regime in power suppresses normal talk and debates in society and between society and government. In fact, regime logic dictates what is and is not allowed in the issue logic of public policymaking.

Discussion and conclusions

For all cases one question was systematically posed: Can Western concepts like ‘policy’ and ‘policy process’ be applied to fully understand governmental practices (Colebatch & Hoppe, Citation2018) in post-Uprisings Arab states, without loss of meaning or concept stretching? We answered this question with a qualified and cautious ‘yes’. At the level of the logic of the policy issue itself, and at first sight, the Western frameworks appeared to do rather well. But looking harder and deeper, the policy issue logic of contested politics and policymaking practices was embedded in, and interdependent with, two other logics of governing: a national regime logic, and an inter- or transnational geopolitical and/or geo-economic regime logic. This mutually dependent set of strategic action fields around any policy issue is what we mean by the ‘regimes-triad approach’ to understand public policymaking in post-Uprisings Arab states.

All policymaking at the level of the policy issue itself is a gravitational force-field where policymaking activities are constantly pulled between two poles: policymaking as puzzling and as powering (Hoppe, Citation2011). Western canon policy process theories have analyzed the intellectual, puzzling aspects of policymaking more thoroughly than the powering aspects. This has to be taken into account when studying policymaking processes in the Arab world. There the national and trans/international regime logics usually draw public policymaking into a gravitational vortex where powering easily trumps puzzling. For editorial purposes, the regimes-triad approach was empirically elaborated and demonstrated in detail in the analyses of the two Lebanese cases; and then used to analyze and sum up the findings of the other cases.

The issue logic bias is strongest in the ACF. It cannot but see politics and policymaking as governing through advocacy coalition building, and nonviolent conflict management. In the case of Tunisia, the blind angles show up in the ACF’s core concepts of ‘advocacy coalitions’ and ‘policy subsystems’. In Tunisia coalition behavior and strategies were observed that could not easily be accommodated in ACF definitions of ‘advocacy coalitions’ as sharing core and policy beliefs, and, especially, strong coordination of members’ coalition. Also, the idea of stable, clearly delineated policy subsystems did not apply in Tunisia. Interestingly, like in the Lebanese KAFA case, also in the Tunisian case, we saw that (I)NGOs combined policy actor roles, although the ACF predicts brokerage roles between the coalitions only. Policy entrepreneurship roles are posited by the MSF. Obviously, in MENA-countries, the role differentiation hypothesized in wester-canon theories of the policy process needs to be taken with a grain of salt.

In all these observations, the ACF reveals its western bias: policymaking is, in terms of cogitation or puzzling, a learning process where participants with different views engage in a game of competitive analyses and persuasion strategies, where the more persuasive argument supposedly wins a majority in a parliament or in the polls. Even when the international regime context is somehow taken into account, it is supposed to affect the domestic issue logic through intellectual processes like transnational policy learning, transfer, and dissemination (Knaggård, Hildingsson, & Skovgaard, Citation2016). In terms of agonistic interaction and powering, it is a perhaps not-so-peaceful but still non-violent struggle between advocacy coalitions over policies, in which the party with the largest amount of votes, or money, or the best propaganda machine wins. That both sides of the policymaking game could play out in a higher agonistic register, bordering on and transgressing into outright criminal state practices (Ross, Citation2012), is beyond the pale. It is telling that Howlett and Mukherjee (Citation2014), in speaking of ‘non-design’ as the powering or agonistic part of policymaking, list relatively innocent practices of bargaining, corruption or clientelism, log-rolling, and electoral opportunism. However, in Egypt, ‘policy’ as reflected-upon and systematically applied course of action does include political practices bordering on, or transgressing into the criminal. Yet, this is simply ruled out of bounds in the western policy sciences. It is high time (comparative) policy studies include such modes of strong agonistic policymaking in its conceptual orbit, on penalty of making itself irrelevant to substantial parts of policymaking outside the traditional western worldFootnote7Footnote8.

MSF and SCPDF are only somewhat more attuned to the possibility of an interdependent regimes-triad logic of policymaking. In the Lebanese cases it was shown how the three regimes interact, and in different ways. In both cases, the MSF was applied, but through opposing ‘political godfathers’ to ‘policy entrepreneurs’, and through a novel interpretation of ‘problem politics’, the Lebanese cases allowed for the unearthing of national and international regime logics that interfered with the issue logic in normal policymaking. KAFA’s policy entrepreneurs could cunningly use the national and international regime logics to score a limited policy issue success. But, as policy entrepreneur, Minister Nahas was victimized by the regime’s ‘godfathers’, who determined a ‘winner’ in terms of the policy issue logic, in the interest of their ongoing power struggles at domestic and international regime levels. The SCPDF was the only framework from the western canon which explicitly harbored the possibility of erosion of democratic attitudes and civil society activism because it was built into an issue logic of policy design. In fact, its issue logic of differential burdens/rewards for (un)deserving target groups proved an accurate description of policymaking practices towards (I)NGOs by the government and policy-mediation practices by state-run media in autocratic Egypt.

Apart from clearly showing both possibilities and limitations in the western canon of policy process theorizing when applied to policy research in Arab states, what else can be learned from the case studies about governing and policymaking in the Arab world? One obvious finding is that their political systems, although using identical terminology to label their institutions (‘parliament’, ‘supreme court’, ‘political parties’, etc.), in practice obey different rules than in consolidated western democracies. Most importantly, courts are weak and parliaments and political parties are gatekeepers against, hardly initiators for policy initiatives and innovations emanating from civil society (cf. Katomero, Hoppe, & Wesselink, Citation2017; Völkel, Citation2019). In none of the cases, political parties embraced and pushed for the issues brought up by CSOs. As a result, it seems, CSOs and NGOs, not very successfully, attempt to bypass party politics and parliaments and try to deal directly with governmental bureaucracy and ministers.

Bayat (Citation2013) has offered a vivid description of how social and policy change comes about in an average Arab country. Regimes that display fake or manipulated electoral democracy of the illiberal type are so intolerant and repressive toward organized activism, that civil society actors hardly have a chance to use the nonviolent strategies of social movements of workers, the poor, women, youth, students or broader pro-democratic transition movements. This effectively precludes political and policymaking practices as taken for granted in social movement theories for consolidated democracies (e.g., Tilly & Tarrow, Citation2015), where civil society movement pressure induces political parties and governments to commit to undertaking large-scale social and political reforms in the interest of a majority of its citizens. In such illiberal democracies, government initiatives are frequently restricted to introduce, at the instigation of international financial institutions and the larger and more powerful donor countries, neoliberal reforms for economic élites closely tied to the political, bureaucratic and military or deep-state élites. As a response to the lack of national agency to challenge the ossified status quo, global ‘progressive’ forces devised the strategy of regime change from outside under economic and political incentives and sanctions. In its non-state and non-violent manifestations, this led to the NGO-ization of parts of Arab civil society, externally funded by western states, international charities, and the United Nations. Although well-meaning, as shown in the cases of Lebanon and Tunisia, this mode of external influence does not foster durable effectiveness of domestic interest groups, social movements, and political economies. Contrary to its intentions, it did lead to draconic anti-NGO policies like in Egypt.

Focusing on what happens on the ground in Arab illiberal democracies for policy change to occur, Bayat (Citation2013, p. 35) no longer seems to believe in states as agents of purposive, orderly social change. He points out the importance of quiet encroachment of nonmovements and passive networks, i.e., “noncollective but prolonged direct actions of dispersed individuals and families to acquire the basic necessities of life (…) in a quiet and unassuming illegal fashion.” Having retreated from the social responsibilities under earlier Arab socialism and nationalism, neoliberally oriented states are actually too weak to resist the power of the masses. They may originally attempt to strike back by using their repressive arsenals, but quickly have to retreat to random acts of suppression due to lack of systematic enforcement capacities. Hence, sooner or later they embark on a policy of partial and uninformed accommodation and toleration of the gains in life opportunities by the nonmovements. Such a passive policy of adjustment and accommodation reflects the situation of poor policymaking and low policy subsystem skills as discussed in section two (see ).

Overall, CSOs and (I)NGOs have not been very successful in influencing the government to change policy in desired directions. ‘Success’ at best meant symbolic legal changes, but ongoing struggle for meaningful implementation and compliance. As instances of dramaturgical incrementalism, they show the limits of CSOs and NGOs as policy entrepreneurs in achieving long-lasting policy change. Nevertheless, the conceptual gain claimed by the regimes-triad approach to policymaking in Arab countries is twofold. First, it claims that Western models of ‘policy’ and ‘policy process’ do apply in the governmental practices of Arab states (also Hoppe, Citation2019, pp. 148–151), but with important qualifications and nuances. Arab states just cannot be pictured as fully fledged ‘policy states’ that find their major purpose and raison d’être in solving public policy problems and policy implementation as service delivery for a majority of their citizens. Yet, dramaturgical incrementalist changes in Lebanon and perhaps Tunisia show that it is not impossible that a policy issue logic, initiated by cleverly operating CSOs, invades sympathetic élites’ regime logic. Second, the regimes-triad approach offers a nuanced understanding of the post-Uprisings politics in the Arab world: without denying failures and disappointments, it does not fall back into the exceptionalism thesis of ingrained autocracy and incompatibility between Islam and democracy. The regimes-triad approach hopefully offers political and civil society actors a more complete understanding of their political environments which allows for discovering and defining realistic opportunities for dealing constructively with the many challenges facing contemporary Arab politics. In that sense, there remains hope for state-initiated change next to Bayat’s fatalist picture of social change as spontaneous but random and chaotic encroachment of nonmovements.

Notes

1. All case studies referred to in this article were part of a research program “Civil Society Actors and Policy-Making in the Arab World”, coordinated by AUB’s Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs. Space limitations force the authors to select only four cases and provide analytic summaries of the cases. Cases dealing with women issues (Lebanon, Yemen, and Morrocco) are reported in detail in Yassin & Hoppe (Citation2019). The other cases (Lebanon, Tunisia, and Egypt) have all been published as Research Reports by AUB’s Issam Fares Institute: Lea Bou Khater (2018). Understanding politics in Lebanon: an application of the Multiple Streams Framework to the 2012 wage hike; Alex P. Martin (Citation2018); and Nermeen Kassem (Citation2018).

2. In his impressive The Patterning Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanity’s Search for Meaning Prometheus Books, Citation2017, Jeremy Lent convincingly shows that the mild anti-secularism in Medieval Christianity in fact paved the way for the Renaissance and Enlightenment, whereas Islam’s strong anti-secularism precluded similar developments.

3. Shi’a’s Hizbullah is frequently called ‘a state in the state’, and its military wing fights in Syria assist the Houthi’s in Yemen and furtively compete with the Lebanese Armed Forces domestically.

4. The classical example is the way the civil rights movement in the US profited from the Cold War with the USSR in gaining federal majorities, who simply did not tolerate Southern Jim Crow racism to destroy the US moral reputation as a world leader (Fligstein & McAdam, Citation2015, pp. 127–128).

5. Essebsi died, 92 years old, on 25 July 2019.

6. Egypt’s Draft NGO Law: Strengthening National Security or Threatening Civil Society? Egypt Oil & Gas Web Portal. Retrieved from: http://www.egyptoil-gas.com/publications/egyptsdraft-ngo-law-strengthening-national-security-or-threateningcivilsociety/.

7. Of course, the Egyptian government also uses televised talk shows and social media to endorse its policies.