ABSTRACT

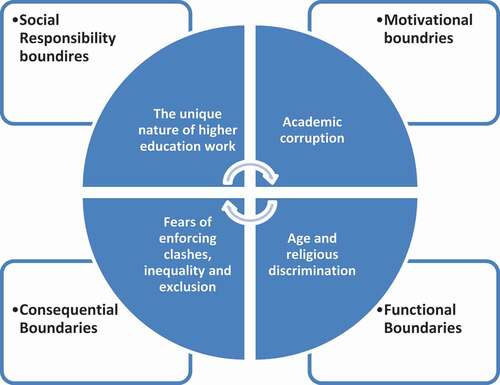

We investigated the relevance of introducing talent identification/classifications among Egyptian public business schools, as perceived by academics, and the expected outcomes of such proposed classification system. We employed thematic analysis of data collected from interviews with 49 academics from three large business schools. Our findings revealed the following themes: no clear systems for talent management; being talent means going the extra mile in research; talent identification/classification system is irrelevant due to: academic corruption; age and religious discrimination; the unique nature of higher education work; and the fears of enforcing clashes, inequality and exclusion. We confirmed that any attempt to constitute talent classifications in the Egyptian higher education does not appear to be a prioritized need for the sector. Nevertheless, we did assert the need to manage motivational, structural, consequential and social responsibility boundaries before the need for constituting any system for talent identification and classifications.

Introduction

In today’s uncertain environment, stakeholders are experiencing growing pressure, and ongoing environmental changes have prompted organizations to form what is labelled “organizational responsiveness”, which constituted a resilient cornerstone during 2008’s global economic downturn (Lacey & Groves, Citation2014). Owing to the noticeable demographic changes and multi-cultural dialogues, organizational responsiveness has enabled organizations to think strategically and subsequently demonstrate an appealing desire to identify, develop and retain talents (Vaiman & Collings, Citation2013; Vaiman et al., Citation2012).

As a result, talents and the management of talents have become critical issues more than ever before (Bolander et al., Citation2017; J. Boudreau & Ramstad, Citation2006; Cappelli, Citation2008; J.W. Boudreau & Ramstad, Citation2005; Konnerth, Citation2008; Michaels et al., Citation2001). Kontoghiorghes (Citation2016) highlights that talents constitute today’s organizational reality and drive present and future business priorities. As a result, the interest in talent-related aspects has started to receive growing attention by researchers from different disciplines such as psychology, HR management, public policy, cultural diversity and public administration (Beechler & Woodward, Citation2009; Dries, Citation2013; Preece et al., Citation2013; Thunnissen et al., Citation2013). Collings et al. (Citation2011) elaborate that research on talents first appeared in North American countries and subsequently received devoted interest in India (Kulkarni & Scullion, Citation2015) China (Cooke, Citation2011) and Russia (Latukha, Citation2015). Recently, it has found a space in the European academic context in countries such as the United Kingdom, Germany, the Netherlands and Spain (Scullion et al., Citation2010).

According to Tarique and Schuler (Citation2010) and Latukha (Citation2011), the interest in talents and their management has received popularity due to the cut-throat competition which leads organizations to employ staff of a calibre who are able to penetrate cultural and geographical borders through their ideas, and also because of the worldwide shortage of elites who have the capabilities to create a better future for their businesses and societies. Garib (Citation2013) and Festing et al. (Citation2015) also add that the demographic global changes besides the spread of a heterogeneous culturally diverse workforce have prompted organizations to consider talent acquisition, development and retention as a norm of today’s organizational life.

The following three schools of thought on talent management have been addressed by many researchers (Collings & Mellahi, Citation2009; Lewis & Heckman, Citation2006; Tarique & Schuler, Citation2010; Valverde et al., Citation2013). The first school of thought considers talent management as a dynamic part of the traditional HRM practices which mainly focus on selecting, recruiting, developing and retaining only those employees whom the organization trusts due to their roles in achieving superior performance results. The second considers talent management as a rebranding for the HRM concept, and accordingly, it targets all of an organization’s employees and enhances their credentials through an organizationally agreed set of competences. The third has either an exclusive approach; which narrows the scope of organizational training, support and learning to only elite/high performers who constitute at most 20% of the organization’s staff; or an egalitarian inclusive approach, which treats all the organization’s staff as talents and prioritizes a detailed set of competences for them to learn and experience.

In this regard, the discourse about exclusive/inclusive approaches on talent management may closely touch on the ongoing debate about equal employment opportunity (Siebers, Citation2009), which involves equal treatment for every applicant/employee without paying attention to his/her gender, religion, ethnicity, race or other differences, as well as preferential selection, which violates the terms of justice and equality (Powell, Citation2011). Needless to say, adopting equal employment opportunity not only alleviates any likelihood of bias, discrimination and in-out group differentiation, but also empowers workplace inclusion, which can be referred to as a person’s ability to contribute fully and effectively to an organization (Roberson, Citation2006), and subsequently, secures employees’ full engagement for attaining better organizational outcomes. This may explain why different organizations consider talent-related concerns and decisions to be sensitive issues.

Therefore, securing a pool of talents to ensure the availability of all present and future needs for high calibre staff remains one of the essential functional goals of the organization (Tansley et al., Citation2007). Deetz (Citation1995) and Watson (Citation2009) point out that projecting talent identity requires developing an individuals’ visible behaviours via training and coaching, as well as supporting their insider feelings (e.g., fears, worries, hopes, desires, etc.) through psychological treatment and spiritual mentoring. Accordingly, every employee seeks to be recognized as a talent not only to ensure his/her superiority in comparison with their colleagues, but also to reflect his/her potential to be a partner or a figurehead within and/or across his/her organizational setting (Huang & Tansley, Citation2012). That is why employees are in a constant competition to gain this identity of talent (Alvesson & Robertson, Citation2006).

If this is the case in for-profit organizations, what is the situation in the setting of academia? Is it relevant to form and use this “talent identity” in academia? If so, how do non-talented academics react accordingly? While many practitioners have extensively addressed the topics of talent and their management and produced many coherent rigorous reports, studies and working papers during the past 20 years (Strack et al., Citation2011), this, however, was not the case in the academic arena, in which the concept of talent has remained at its embryonic stage, particularly when it comes to empirical studies and debates within the organizational context (Lewis & Heckman, Citation2006). Based on what has preceded, we seek to investigate the relevance of using talented/non-talented classifications in the academic arena to explore the perceptions of academic towards such classifications.

Scholars have identified different challenges to effective global talent management (Mellahi & Collings, Citation2010; Schuler et al., Citation2011; Stahl et al., Citation2007, Citation2012), which necessitated the need for more in-depth investigation about how differences between human resources practices in different continents and countries will develop in the future (Brewster, Citation2004; Browaeys & Price, Citation2011). According to Ali (Citation2011), there are two issues essential for talent management in the Middle East: share of the youth in the region and the unemployment rate among the young and general populations.

In Egypt, during the past seven years, the country has witnessed a political youth revolution and a subsequent semi-revolution/semi-military coup resulting in a state of division and silent anger that has become a noticeable phenomenon characterizing Egyptian daily work and non-work life (Mousa, Citation2018; Mousa & Alas, Citation2016). This has made it difficult for Egyptian universities to demonstrate their commitment to and care about the values of solidarity, diversity and acceptance of the other in their educational curricula and practices, as required by the AACSB (Citation2004). This has led the authors of this article to think about the relevance of talented and non-talented identifications and classifications (King & Hugh Scullion, Dr Vlad Vaiman and P, Citation2016; Tansley & Tietze, Citation2013) in the context of Egyptian public business schools. They were prompted by questions on whether talents are a new source of division, whether considering talents would fit the values of inclusion, and what the expected outcomes of this classification would be.

Previous research undertaken by authors (2019a) explored how the practices of managing academic talents, if existed, are perceived by academics, and found no systematic approach for the management of academic talents undertaken at universities in Egypt. They found that there were unorderly procedures undertaken by these business schools in staffing, empowering, motivating, evaluating and retaining those talents with the absence of cultural and technical dimensions like adaptability, consistency and knowledge sharing. However, our current research is extending this topic by attempting to investigate the relevance of developing talent classifications’ systems among universities based on actual needs towards establishing such systems and academics’ view of the real perceived usefulness of such talent management systems.

Literature review

Talent and talent management

Yeung et al. (Citation2008) highlight the dearth of research on talents in emerging markets. Furthermore, authors such as Marin and Verdier (Citation2012), Guerci and Solari (Citation2012), and Huang and Tansley (Citation2012) differentiate between a macro-level view of talents that mainly pays attention to the availability of skilled calibre staff in a specific country and a micro-level view that only addresses how talent is recognized and talent management is experienced in a specific organization and/or business activity.

Several authors have previously defined talent and talent management (Gallardo-Gallardo et al., Citation2013, Citation2015, Citation2016; Holden & Tansley, Citation2007). For example, Williams-Lee (Citation2008) defines talent as a person who is continuously able to have, show and develop an exceptional quality/ability needed for the betterment of his organization and/or society, whereas talent management is the sequence of procedures and/or protocols undertaken to select, attract, hire, staff, develop, evaluate and retain persons whose qualities are unique and needed for their organization (Blass, Citation2007).

Despite the growing interest in talents, Iles et al. (Citation2010) consider the concept of talent as an updated version and/or title created by those who are affiliated to the HR field. The same study considers that the reason for HR affiliated figures to change their titles from Personnel Manager to HR Manager and from HRD Manager to Learning and Development Manager is their continuous need to gain more status than other professionals who belong to other departments (e.g., marketing, finance etc.) in the same organization.

In the same context, Nadler and Nadler (Citation1989) have defined HRD as an organized learning experience provided by employers within a specific period of time to bring about the possibility of performance improvement and/or personal growth. Accordingly, and given the previous definition of HRD, it appears that the main purposes of HRD are the same as those in talent management, and they both seek to enhance organizational performance and/or personal growth, the matter that, to some extent, reflects that talent management is not considered a new approach for managing people, but is mostly the same as HRM/HRD strategies and mainly involves having the right people at the right time to fulfil the right job responsibilities. However, Lewis and Heckman (Citation2006) think that talent strategy reflects only a part of HRM traditional strategy, as it has narrowed its scope by focusing only on a selective segment of employees whom the organization’s top management identifies as “stars” and smoothly tailors programmes for their support and development.

Vaiman et al. (Citation2012) have raised a new debate when considering talent-related aspects as a part of the organization’s overall strategy, not only a part of the HR one. They consider this because talent-related decisions affect the overall success of an organization, on the one hand, and an organization’s resources on the other. Therefore, the talent management department should not be in isolation from HR, marketing, finance and other organizational active departments. Scullion and Collings (Citation2006) support the same view when indicating that the emergence of the concept of talent comes as a result of several factors (e.g., diversity, corporate social responsibility, increased mobility, dominance of knowledge-based economy, changing demographic trends, talent shortage and growth of emerging markets) that are related to different global, national and organizational phenomena that remotely touch HR majors.

According to Naim and Lenka (Citation2017), there are two approaches to managing talents. The first is the inclusive approach to talent management which considers that every organizational member has potential, and therefore should be granted an opportunity to be supported in order to be able to fulfil his/her job responsibilities. The second approach is the exclusive one which focuses only on a few employees who are of great importance to their organization, and consequently their organization invests in them to prompt a superior performance from them. Despite the need of all employees for support from their organization, Lacey and Tompkins (Citation2007) indicate that an organization has the right to treat its organizational members differently. In other words, an organization has the right to offer its talented staff some special treatments (e.g., out of office meetings, informal gatherings, additional financial package etc.) and at the same time care about other employees’ internal feelings (e.g., marginality, organizational ostracism, cognitive and emotional distress etc.).

Cultural clashes may come as a result of talent protocols when an organization appreciates outsiders more than its current employees, or when it values a few employees over other staff (Mousa et al., Citation2021; Pfeffer, Citation2001). Haslam (Citation2006) asserts the same notion and notes that considering the majority of employees as performers (non-talented individuals) entails a kind of dehumanizing and curbs employees’ self-confidence, which turns into alleviating their organizational commitment and subsequently performance levels, besides diminishing their work outcomes. It is worth highlighting that such an approach to talent management deters distributive justice that urges an organization to care about every one of its staff through the equal distribution of its benefits (e.g., technical support training, coaching, financial remuneration, etc.), as indicated by Hartman (Citation2008). Accordingly, Coulson‐Thomas (Citation2008) points out that identifying insider talents or even recruiting them from outside the organization may entail a change within the dominant organizational culture, internal procedures, and training dynamics. Coulson‐Thomas (Citation2012) also indicates that introducing talent-related aspects inside an organization prompts a change in internal communication, assessment methods and inclusion approaches, even if these changes consume time, money and effort. Importantly, Allen et al. (Citation2010) elaborate that if talents are not properly managed, they only feel committed to their career aspirations, which accelerates their rate of turnover and destroys any possible discourse about citizenship behaviour.

Based on the aforementioned, Johnson (Citation2001) demonstrates that any organization should hire only those who are culturally aligned to its current system of values, ethics and virtues. Moreover, Ployhart (Citation2006) confirms that besides their performance, talented individuals need the organization they work in to care about their internal feelings such as fears, worries and hopes, to perceive the full engagement of those talents. Gathmann and Schoenberg (Citation2010) indicate that investing in workgroup training initiatives is much more beneficial to an organization than investing in only a niche of talents, because every talented employee can easily be headhunted by competitors even if he/she has received many personal and work-related enhancements. In this regard, Miller and Cummings (Citation2009), Baxter (Citation2011), Tansley (Citation2011), and Downs and Swailes (Citation2013) agree that both talented and non-talented employees link the process of identifying talents with their organization’s level of neutrality, style of leadership, gender characteristics and even leader-followers ethical relationships. Consequently, Downs and Swailes (Citation2013) describe the process of identifying talents as a social procedure that closely touches on an organization’s ethical components.

Talent management in academia

The higher education sector is currently facing the challenges of an ageing population, increased immigration and financial cuts (Van den Broek et al., Citation2018). Hendriks et al. (Citation2016) add that the emergence of cross-disciplinary academic units and ongoing advancements in information technology are also considered challenges that promptly and continuously need a kind of collaboration between public officials, academics and social actors to strike a balance between academic affairs and socially responsible behaviour. Subbaye and Dhunpath (Citation2016), Reddy et al. (Citation2016), Mousa (Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2020c), Mousa et al. (Citation2020), and Mackay (Citation2017) assert that the long-term development of academics contributes to their knowledge competences, and subsequently, their professional identity. Martin et al. (Citation2016) consider academics as talented personnel as they possess competencies and exceptional capabilities that can be utilized for the betterment of their universities and societies. The same has been highlighted by Drucker (Citation2001), who asserts that academics fit into the ‘golden worker’ category as they supervise students, carry out and publish research, provide consultancy services and contribute to their universities’ academic ranking. As a result, they constantly suffer from more work stress than those who hold traditional positions. Abu Said et al. (Citation2015) also confirm that an academic’s work of increasing the number of Master’s and PhD holders, supporting graduates’ capabilities and providing business consultation when needed constitutes an effective basis for classifying him or her as a “talented or elite member”.

Despite what has preceded, talent management practices in the academic arena are very few. The number of empirical studies on managing academic talents is also scarce. However, the authors of this paper have touched on some previous attempts for addressing academic talents. Defining talents in the academia settings has been a topic of growing interest to Thunnissen and Arensbergen (Citation2015), who note that the concept varies from one organizational setting to another and is often governed by both internal and external stakeholders’ groups. Mousa and Ayoubi (Citation2019a, Citation2019b)) found that exclusive style of talent management affects the organizational downsizing of academics in Egypt and that responsible leadership plays no role in mediating this relationship, which shows a lack of clear approaches of managing talents in academia. Moghtadaie and Taji (Citation2016) explored talent management approaches in academia in Iran, and found that the “talents development”, “attracting the talent” and “talents maintenance” are respectively ranked by university management in improving the performance of faculty members.

In addressing the recruitment of academic talents, Van den Brink et al. (Citation2013) and Paisey and Paisey (Citation2016) have highlighted that transparency versus autonomy, power of HR versus power of academics, and equality versus homogeneity constitute three main challenges universities face in recruiting their academic staff. Rudhumbu and Maphosa (Citation2015) argue that managers of higher education institutions lack the required competences to draw up and manage talent-related strategies. Kolsaker (Citation2008) also points out the confusion managers of academic institutions have in balancing their managerial and academic roles. Moreover, Erasmus et al. (Citation2017) highlight the poor experience of academic managers in identifying and undertaking responsible talent management practices in different academic contexts.

While the concepts of talent and talent management are considered new in organization-related literature (King & Hugh Scullion, Dr Vlad Vaiman and P, Citation2016; Mousa et al., Citation2019; Ross, Citation2013), the authors of this paper have touched on a rarity in the empirical studies conducted on talent-related aspects in academia. Based on what has preceded in this paper, the authors seek to investigate the relevance of using talented/non-talented classifications in the Egyptian academic arena and to explore the perceptions of academics towards this classification if implemented by university leadership in the future.

Methodology

Procedures

The research process for this paper started in February 2019 by determining the units of analysis for interviews: participants (teaching assistants and assistant lecturers), time (Fall, 2019), and place (public business schools) in addition to the explored behaviour (practices of managing talents in Egyptian public business schools). Most importantly, the authors employed a comprehensive count sampling method to target their respondents (Namey et al., Citation2007). The impetus of using a comprehensive count method is to target all academics who work in the addressed business schools. Worthy of note is that employing comprehensive count sampling as a mechanism was aimed to alleviate bias and increase the likelihood of generalizing the study results. All interviews were in Arabic, semi structured and the duration of each interview was 45 minutes approximately (See Appendix 1 for the interview questions guide attached as a supplementary material).

Participating universities and personnel

This study adopts qualitative approach which is widely used to perform research evaluations (Easterby-Smith et al., Citation2012), to gain knowledge (Ghauri & Grønhaug, Citation2010), and to provide more intricate details and understanding (Bell et al., Citation2019). This study involves the participation of academics who work in three different public business. Within the Egyptian academic context, students and officials always label the School of Business as Faculties of Commerce, or sometimes Colleges of Management. The three selected universities are in Upper Egypt, which represents 25% of Egypt’s total area and often receives the least media coverage and the poorest infrastructural development plans and share of Egyptian public spending. In total, Upper Egypt includes four public universities, but the authors of this paper received acceptance for collaboration from only three of these business schools. The number of Egyptian public universities is 24. The first selected business school has four academic majors (accounting, management, economics and maths) and the authors received acceptance for collaboration in interviews from 18 academic staff in this school. The second school has the same academic majors, and the authors received acceptance for collaboration in interviews from 20 academic staff. The third business school includes the same four academic departments, and the authors received acceptance for collaboration interviews from 11 academic staff.

Observations

It was observed during the interviews that some respondents (nine)refused to have their interviews recorded when they were informed that the authors would record them. This has been carefully dealt with by the authors, and an alternative manual notetaking was conducted. An assurance of privacy and confidentiality was made with the intreviwees before the start of each interview whether it is audio recorded or noted manually. Some transcripts were returned to interviewees who requested a final check before any further analysis to be undertaken by the authors. It was observed that some interviewees were reluctant to reveal details with regard to the administration of their schools out of fear of giving a negative impression about their colleagues who currently manage academic departments, schools and research centres.On another issue, before conducting the planned interviews, the authors were fully aware of the state of division Egypt has been witnessing since its January 2011 revolution (Bauer, Citation2011). Considering the socio-political and economic context, the authors were very sensitive in tailoring their interview questions to the chosen research community composed of three Egyptian public business schools.

Analysis of collected data

Upon conducting the interviews, detailed transcripts are made in which the content of the interviews is typed out. Only relevant information derived from the transcripts is coded. Owing to the specific focus of this research, questions and answers of the research are related to one of the following concepts, namely, talent management, golden workers, academic talents, recruiting, training, developing, deploying, justice, equality, diversity management, work-place discrimination and many others. Within the research, reliability is enhanced via audio recording for some of the conducted interviews, and the authors attempted to target all academics working in the addressed schools. Internal validity is enhanced by cyclical proceedings of data collection and analysis. Furthermore, all interviews are conducted in Arabic which is the native language for both respondents and authors.

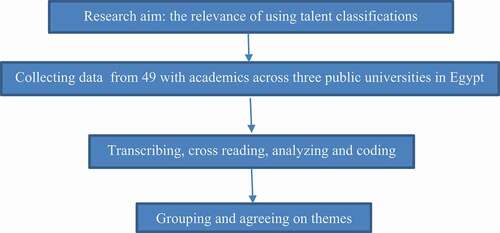

The authors used thematic analysis, which mostly determines the main patterns/ideas from the transcripts, by identifying, analyzing, organizing, describing, and reporting themes found within a data set (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). In applying this method, we compare each transcript with the other transcripts collected in order to narrow down the data sets and come up with the main patterns (Namey et al., Citation2008). Subsequently, the patterns were coded into constituent themes, and the main themes were extracted to reflect the respondent’s main answers/experiences/viewpoints. All authors participated in the coding and analysis after peer checking for five transcripts in order to agreeing in general principals of completing coding and analysing the remaining transcripts. For details describing the thematic analysis map please see .

Findings and discussion

In responding to the interview questions, the following themes have been identified by the authors. We align the findings, discussion and implications for each resulted theme from our interviews (see ).

No clear systems for talent management

As confirmed by Mousa and Ayoubi (Citation2019a) that no talent management systems are operated in public universities in Egypt, this study extended this result, as respondents clarified that they were being assessed on a monthly basis by the head of their academic department and/or supervisor, and they noted that the only two criteria by which they are assessed are their teaching of their assigned courses and the extent to which academics are conformist, in that they do not discuss, debate or disturb either their supervisors or professors.

Being talent means going the extra mile in research

The interviewees show that the concept “talent” and its scope are not only limited to musical, artistic and sporting figures but also to the exceptional qualities employees have and can positively use to affect the present and future of their organizations and subsequently society. According to the respondents, academic talent was defined as the academic who has carries out research more than normal. “I consider an academic talented person as the person who attends academic conferences, does research, regularly publishes in high-ranked academic journals and is often ready to cooperate with practitioners in business and social consulting” said one of the respondents.

Talent identification/classification system is irrelevant due to academic corruption

The authors asked about academics’ perceptions if their business school to classify them into talented and non-talented, and the respondents in most interviews rejected this suggestion completely. One of the respondents proclaimed that “we as academics are currently suffering from organizational nepotism in which every rector and/or department head tends to give maximum attention and high priority to the academic work of only one or two academics, either because of personal relationships with them or because of the luxurious financial presents or even “bribery” received offered by those academics”. The same was iterated by another respondent when noting that “before such talented/non-talented classification, distributive justice is non-existent. Only a few academics dominate the training opportunities, financial rewards and informal benefits with professors”.

As noted above, much uncertainty regarding the fair selection and, subsequently, the effective implementation of talented/non-talented classification already exists. This may come as a result of the absence of procedural justice which is mainly based on neglecting an individual’s competences and other credentials when making a decision related to his career (Siebers, Citation2009). The majority, if not all, of the respondents highlighted the role personal relationships and organizational nepotism play in shaping academics’ future. This represents clear ignorance for Powell (Citation2011), who asserts that excluding organizational members without justified transparent procedures violates not only equal employment dynamics but also organizational peace mechanisms. This negatively impacts the organization’s overall performance.

Talent identification/classification system is irrelevant due to age and religious discrimination

Surprisingly, another respondent mentioned that “even if there were no personnel relationships and/or obedience, a school administration would use the age of academics as a basis factor for this new talented/non-talented classification. Usually, a school would grant the title “talented” to the oldest academic in every academic department. This is the case in most Egyptian public universities”. A Christian respondent clarified that if it comes to selecting talented staff, Christian academics would never be selected because of their religion. Disappointedly, he complained that “I have completely no work rights because I am Christian”. Two respondents elaborated that using/introducing the concept “talent” to the Egyptian academic context brings nothing more than a new state of division. As they think, academics now are divided into liberal and Islamist, Muslims and Christians, and now a new disturbing classification “talented and non-talented academics.

The discourse of some respondents about using religion and age as a basis for assigning academic privileges in the context of the selected business schools represents another case for the essentially in-out group differentiation and its subsequent workplace discrimination that would further hinder any thought of creating a pool of talents there. Schaafsma (Citation2008) indicates that using similarities and dissimilarities to categorize people into groups may be hurdles for the opportunities to build and maintain in-organization harmony. The same can be said about the intentional unjustified negative actions towards members of a group simply because they are different (Ogbonna & Harris, Citation2006).

Talent identification/classification system is irrelevant to universities due to their nature

Respondents were asked about the logic or motive behind the possibility of introducing the identity of talent to the academic setting, particularly if it involved the same two objectives included in the context of human resource development protocols, which are enhancing organizational performance and cherishing personal growth. One respondent said: “those HR practitioners regularly change or create new titles for their job; they transformed from personnel to human resource managers, to human resource development managers, then to learning and development managers, and now to talent managers only to create more job responsibilities, more job opportunities and subsequently more money and financial incentives”. Many respondents believe that not every title that appears in a for-profit organization fits academic institutions and their members. When asking respondents what would happen if the identity of talent is to be introduced to their business school however they are not considered as a talented academic, they are felt disturbed and rejected this action.

The ambiguous difference between HRD objectives and talent management strategy objectives may delay introducing talent identity to various academic settings. Iles et al. (Citation2010) consider that both HRD and talent management strategies aim at raising organizational performance and personal growth, which constitute the same objectives constantly announced by any talent management strategy. Accordingly, no clear difference between them has been touched upon. Another point that should be highlighted is that in private organizations, every employee strives to ensure his/her superiority as a step towards becoming a partner or a figurehead within a particular department in order to attain a better financial and psychological package (Huang & Tansley, Citation2012). This pass is not available in the higher education sector because every academic knows very well that he or she will gain nothing more than his/her monthly salary and will never be a partner in a public organization setting.

Talent identification system is irrelevant as it will enforce work clashes, inequality and exclusion

Furthermore, one respondent stated that “using a talented/non-talented classification in an academic setting curbs an equal employment protocol which involves giving the same chance to every employee in the same workplace”. Moreover, the majority of respondents demonstrated that any discourse about inclusion and the engagement of academics for the betterment of the school, present and future, would turn out to be irrelevant upon applying such classification, as every academic would think about his career commitment instead of commitment to the organization. Additionally, and given this unhealthy organizational climate, negative organizational phenomena such as absenteeism, cyber loafing, intention to quit and day dreaming would constitute the main norms of academic existence.

Furthermore, they all considered any proposed talent identification and classification system as an open door for workplace tensions and cultural clashes. A respondent said: “valuing my colleague higher than me in this unfair work atmosphere entails a kind of dehumanizing feeling that sooner or later would urge me to leave my position”. Another claimed that “this unneeded classification yields negative emotions among colleagues, and towards their heads, school and even university – an aspect that accelerates nothing except academics’ turnover intentions”.

What may curb any attempt to use the concept “talent” in the selected business schools is the kind of dehumanization respondents conveyed when confronted with the notion of talented/non-talented categorization. This comes in agreement with Pfeffer (Citation2001), who indicates that cultural clashes besides workplace conflicts may come as a result of a talent pool when appreciating a few employees (academics in this case) more than other staff. In the conducted interviews, respondents clarified that nothing except negative attitudes towards their colleagues and subsequently their workplace would accrue if this kind of classification were applied. Andersson and Bateman (Citation1997) use the concept of cynicism to describe employees’ negative feelings towards their organization. Simha et al. (Citation2014) confirm the role of organizational cynicism on raising work stress, job burnout and subsequently psychological withdrawal (Abraham, Citation2000; Andersson, Citation1996). Moreover, Coulson‐Thomas (Citation2012) demonstrates that a talent-related strategy would not be effectively introduced without a change in internal communication, assessment methods and inclusion approaches. The same has been confirmed by Allen et al. (Citation2010) when pointing out that if talent protocols are not properly designed, introduced and managed (Tansley & Sempik, Citation2008), they would foster only employees’ turnover intentions. This aspect was communicated by many respondents in the chosen business schools.

Conclusions and implications

As noted earlier, our study is extending the work of Mousa and Ayoubi (Citation2019a), where the previous study found that there were no systematic procedures undertaken by public business schools in staffing, empowering, motivating, evaluating and retaining talents. A point that is generalizable to other public business schools given the similarities in organisational structures, management and macro level of supervision by the Ministry of Higher education in the Country. This research aimed to discover the relevance of using talented/non-talented classifications in Egyptian public business schools. As shown above, upon analysing the conducted interviews and hearing about the working conditions in the chosen context, the authors of this paper have realized that any talented/non-talented academic classification is an irrelevant practice. However, and given the subsequent findings, the authors of this paper consider that the situation could be changed, and this talented/non-talented classification might turn out to be relevant if practically universities manage to develop the concept of good academic, to disseminate good practices of manging and developing academics and to consider all the organisational, social and cultural factors before initiating any system for talent identification/classification.

More specifically, the authors believe that the following four boundaries need to be identified and managed. Firstly, motivational boundaries, which is the extent to which academics feel some privileges (financial rewards, psychological recognition and hierarchical authority) if he or she is recognized as more superior/talented than his or her colleagues. Secondly, structural/functional boundaries: the extent to which an academic trusts the procedures his/her school undertakes when establishing its pool of academic talents. In the present case, an Egyptian academic should not doubt his/her school’s system of procedural and distributive justices besides his/her school’s virtues of cultural tolerance (age diversity, religious diversity etc.). Thirdly, consequential boundaries: the extent to which an academic believes his/her school constitutes its pool of talented academics based on transparent credentials and criteria. Accordingly, no feelings of organizational cynicism, turnover intention or psychological withdrawal will be yielded to. Fourthly, social responsibility boundaries: the extent to which academics believe that part of their work is to serve the community, the public and overall society (see ).

This research may be subject to criticism because it offers only a single point of view of “academics in three chosen business schools” without addressing the perspectives of other stakeholders (rectors and heads of academic departments), a matter that hinders constituting a holistic picture of the situation. So, it is advisable for other researchers in the same field to investigate the same research questions with other academic partners in the same public business schools. Moreover, addressing Egyptian private business schools may also enrich the findings discovered here. Therefore, the findings of this research could be generalizable only to Egyptian public business schools which are mostly subject to the same values, working conditions, and infrastructure/info-structure facilities. However, the situation in private business schools and other faculties is still unknown by the authors of this paper and needs to be explored. Moreover, the findings of this study are generalizable to other public universities, in other countries in the Middle East, with similarities of cultural, political, economic and societal backgrounds.

Finally, and as implications for rectors and professors, the authors found that a development of the concept “good academic” should be initiated. This concept should work as a real transitional starting point to introduce “the identity of talent” inside the academic context. The concept “good academic” should specify what obligations every academic should fulfil to attain both in-department and in-school recognition. Moreover, this good academic development secures a transparent platform for cross-disciplinary collaboration, argument and accomplishment.

References

- AACSB, Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business. (2004). Eligibility procedures and accreditation standards for business accreditation (Rev ed.).

- Abraham, R. (2000). Organizational cynicism: Bases and consequences. Genetic, Social and General Psychology Monographs, 126(3), 269–292.

- Abu Said, A. M., Rosdi, R. M., Abu Samh, B., Silong, A. D., & Sulaiman, S. (2015). A career success model for academics at Malaysian research universities. European Journal of Training and Development, 39(9), 815–835. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-03-2015-0022

- Ali, A. (2011). Talent management in the Middle East. In H. Scullion & D. Collings (Eds.), Global talent management (pp. 155–177). Routledge.

- Allen, D. G., Bryant, P. C., & Vardaman, J. M. (2010). Retaining talent: Replacing misconceptions with evidence-based strategies. Academy of Management Perspectives, 24(2), 48–64.

- Alvesson, M., & Robertson, M. (2006). The best and the brightest: The construction, significance and effects of elite identities in consulting firms. Organization, 13(2), 195–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508406061674

- Andersson, L. M. (1996). Employee cynicism: An examination using a contract violation framework. Human Relations, 49(11), 1395–1418. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679604901102

- Andersson, L. M., & Bateman, T. (1997). Cynicism in the workplace, some causes and effects. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 18(5), 449–469. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199709)18:5<449::AID-JOB808>3.0.CO;2-O

- Bauer, P. (2011). The transition of Egypt in 2011: A new springtime for the European neighborhood policy. Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 12(4), 420–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/15705854.2011.622958

- Baxter, J. (2011). Survival or success? A critical exploration of the use of ‘doublevoiced’ discourse by women’s business leaders. Discourse & Communication, 5(3), 231–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481311405590

- Beechler, S., & Woodward, I. (2009). The global war for talent. Journal of International Management, 15(3), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2009.01.002

- Bell, E., Bryman, A., & Harley, B. (2019). Business research methods (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Blass, E. (2007). Talent management: Maximizing talent for business performance (pp. 1–13). Chartered Management Institute and Ashridge Consulting.

- Bolander, P., Werr, A., & Asplund, K. (2017). The practice of talent management: A framework and typology. Personnel Review, 46(8), 1523–1552. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-02-2016-0037

- Boudreau, J., & Ramstad, P. (2006). Talentship and HR measurement and analysis: From ROI to strategic organizational change. Human Resource Planning, 29(1), 25–33.

- Boudreau, J. W., & Ramstad, P. M. (2005). Talentship, talent segmentation, and sustainability: A new HR decision science paradigm for a new strategy definition. Human Resource Management, 44(2), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20054

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brewster, C. (2004). European perspectives on human resource management. Human Resource Management Review, 14(4), 365–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2004.10.001

- Browaeys, M. J., & Price, R. (2011). Understanding cross-cultural management (2nd ed.). Financial Times-Prentice Hall.

- Cappelli, P. (2008). Talent on demand. Harvard Business School Press.

- Collings, D. G., & Mellahi, K. (2009). Strategic talent management: A review and research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 19(4), 304–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.04.001

- Collings, D. G., Scullion, H., & Vaiman, V. (2011). European perspectives on talent management. European Journal of International Management, 5(5), 453–462.

- Cooke, F. (2011). Talent management in China. In H. Scullion & D. Collings (Eds.), Global talent management (pp. 132–154). Routledge.

- Coulson‐Thomas, C. (2008). Developing directors, key questions for the training and development community. Industrial and Commercial Training, 40(7), 364–373. https://doi.org/10.1108/00197850810912234

- Coulson‐Thomas, C. (2012). Talent management and building high performance organisations. Industrial and Commercial Training, 44(7), 429–436. https://doi.org/10.1108/00197851211268027

- Deetz, S. (1995). Transforming communication, transforming business: Building responsive and responsible workplaces. Hampton Press.

- Downs, Y., & Swailes, S. (2013). A capability approach to organizational talent management. Human Resource Development International, 16(3), 267–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2013.782992

- Dries, N. (2013). The psychology of talent management: A review and research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 23(4), 272–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2013.05.001

- Drucker, P. F. (2001). The essential drucker. Harper Collins.

- Easterby-Smith, M., Thorpe, R., Jackson, P., & Lowe, A. (2012). Management research (4th ed.). Sage.

- Erasmus, B., Naidoo, L., & Joubert, P. (2017). Talent management implementation at an open distance e-learning higher educational institution: The views of senior line managers. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 18(3), 83–98. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i3.2957

- Festing, M., Kornau, A., & Schafer, L. (2015). Think talent- think male? A comparative case study analysis of gender inclusion in talent management practices in the German media industry. The International Journal of Human Resources Management, 26(6), 707–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.934895

- Gallardo-Gallardo, E., Dries, N., & González-Cruz, T. F. (2013). What is the meaning of ‘talent’ in the world of work? Human Resource Management Review, 23(4), 290–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2013.05.002

- Gallardo-Gallardo, E., Nijs, S., Dries, N., & Gallo, P. (2015). Towards an understanding of talent management as a phenomenon-driven field using bibliometric and content analysis. Human Resource Management Review, 25(3), 264–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2015.04.003

- Gallardo-Gallardo, E., Thunnissen, M., Hugh Scullion, & Dr Vlad Vaiman, P. (2016). Standing on the shoulders of giants? A critical review of empirical talent management research. Employee Relations, 38(1), 31–56. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-10-2015-0194

- Garib, G. (2013). Diversity is in the eye of the beholder: Diversity perceptions of managers. The Psychologist-Manager Journal, 16(1), 18–32. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0094733

- Gathmann, C., & Schoenberg, U. (2010). How general is human capital? A task-based approach. Journal of Labor Economics, 28(1), 1–49. https://doi.org/10.1086/649786

- Ghauri, P., & Grønhaug, K. (2010). Research methods in business studies: A practical guide (4th ed.). FT Prentice Hall.

- Guerci, M., & Solari, L. (2012). Talent management practices in Italy – Implications for human resource development. Human Resource Development International, 15(1), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2011.647461

- Hartman, E. M. (2008). Socratic questions and Aristotelian answers: A virtue-based approach to business ethics. In G. Flynn (Ed.), Leadership and business ethics. issues in business ethics (Vol. 25). Springer.

- Haslam, N. (2006). Dehumanization: An integrative review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(3), 252–264. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4

- Hendriks, P. H. J., Ligthart, P. E. M., & Schouteten, R. L. J. (2016). Knowledge management, health information technology and nurses’ work engagement. Health Care Management Review, 41(3), 256–266. https://doi.org/10.1097/HMR.0000000000000075

- Holden, N., & Tansley, C. (2007). ‘Talent’ in European languages: A philosophical analysis reveals semantic confusions in management discourse.Paper Presented at Critical Management Studies Conference, Manchester Business School, University of Manchester.

- Huang, J., & Tansley, C. (2012). Sneaking through the minefield of talent management: The notion of rhetorical obfuscation. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(17), 3673–3691. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.639029

- Iles, P., Chuai, X., & Preece, D. (2010). Talent management and HRM in multinational companies in Beijing: Definitions, differences and drivers. Journal of World Business, 45(2), 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2009.09.014

- Johnson, C. (2001). Meeting the ethical challenges of leadership. Sage Publications.

- King, K. A., Hugh Scullion, & Dr Vlad Vaiman, P. (2016). The talent deal and journey: Understanding how employees respond to talent identification over time. Employee Relations, 38(1), 94–111. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-07-2015-0155

- Kolsaker, A. (2008). Academic professionalism in the managerialist era: A study of English universities. Studies in Higher Education, 33(5), 513–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802372885

- Konnerth, T. (2008, July). The war for talent. Human Resources, 64–65.

- Kontoghiorghes, C. (2016). Linking high performance organizational culture and talent management: Satisfaction/motivation and organizational commitment as mediators. The International Journal of Human Resources Management, 27(16), 1833–1853. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1075572

- Kulkarni, M., & Scullion, H. (2015). Talent management activities of disability training and placement agencies in India. The International Journal of Human Resources Management, 26(9), 1169–1181. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.934896

- Lacey, M. Y., & Groves, K. (2014). Talent management collides with corporate social responsibility: Creation of inadvertent hypocrisy. Journal of Management Development, 33(4), 399–409. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-06-2012-0073

- Lacey, M. Y., & Tompkins, T. (2007). Analysis of best practices of internal consulting. Organization Development Journal, 25(3), 123–131.

- Latukha, M. (2011). To stay or leave: Motives behind the decisions of graduate programs’ trainees’ in European and Russian companies. Journal for East European Management Studies, 16(2), 140–161. https://doi.org/10.5771/0949-6181-2011-2-140

- Latukha, M. (2015). Talent management in Russian companies: Domestic challenges and international experience. The International Journal of Human Resources Management, 26(8), 1051–1075. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.922598

- Lewis, R. E., & Heckman, R. J. (2006). Talent management: A critical review. Human Resource Management Review, 16(2), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2006.03.001

- Mackay, M. (2017). Identify formation: Professional development in practice strengthens a sense of self. Studies in Higher Education, 42(6), 1056–1070. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1076780

- Marin, D., & Verdier, T. (2012). Globalization and the empowerment of talent. Journal of International Economics, 86(2), 209–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2011.10.005

- Martin, G., Farndale, E., Paauwe, J., & Stiles, P. (2016). Corporate governance and strategic human resource management: Four archetypes and proposals for a new approach to corporate sustainability. European Management Journal, 34(1), 22–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2016.01.002

- Mellahi, K., & Collings, D. (2010). The barriers to effective global talent management: The example of corporate elites in MNEs. Journal of World Business, 45(2), 143–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2009.09.018

- Michaels, E., Handfiels-Jones, H., & Axelrod, B. (2001). The war for talent. Harvard Business School Press.

- Miller, K., & Cummings, G. (2009). Gifted and talented students’ career aspirations and influences: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship, 6, Article 8. https://doi.org/10.2202/1548-923X.1667

- Moghtadaie, L., & Taji, M. (2016). Study of the performance of faculty members according to talent management approach in higher education. Educational Research and Reviews, 11(8), 781–790.

- Mousa, M. (2018). Inspiring a work-life balance: Responsible leadership among female pharmacists in the Egyptian health sector. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 6(1), 71–90. https://doi.org/10.15678/EBER.2018.060104

- Mousa, M. (2020a). Does gender diversity affect workplace happiness for academics? The role of diversity management perceptions and organizational inclusion. Public Organization Review, Vol. in press No. in press. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-020-00479-0

- Mousa, M. (2020b). Organizational inclusion and academics’ psychological contract: Can responsible leadership mediate the relationship? Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 39(2), 126–144. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-01-2019-0014

- Mousa, M. (2020c). Diversity management in Egyptian public contexts: When the heat yields cold reactions. In A. Farazmand (Ed.), Global encyclopedia of public administration, public policy, and Governance/management.

- Mousa, M., & Alas, R. (2016). Cultural diversity and organizational commitment: A study on teachers of primary public schools in Menoufia (Egypt). International Business Research, Canadian Center of Science and Education, 9(7), 154–163.

- Mousa, M., & Ayoubi, R. (2019a). Talent management practices: A study on academic in Egyptian public business schools. Journal of Management Development, 38(10), 833–846. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-01-2019-0030

- Mousa, M., & Ayoubi, R. (2019b). Inclusive/exclusive talent management, responsible leadership and organizational downsizing: A study among academics in Egyptian business schools. Journal of Management Development, 38(2), 87–104. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-11-2018-0325

- Mousa, M., Ayoubi, R., Massoud, H., & Chaouali, W. (2021). Workplace fun, organizational inclusion and meaningful work: An empirical study, public organization review. Vol. in press No. in press.

- Mousa, M., Massoud, H., & Ayoubi, R. M. (2019). Organizational learning, authentic leadership and resistance to change: A study on Egyptian academia. Management Research, 18(1), 5–28.

- Mousa, M., Massoud, H., Ayoubi, R. M., & Puhakka, V. (2020). Barriers of organizational inclusion: A study among academics in Egyptian public business schools. Human Systems Management, 39(2), 251–263. https://doi.org/10.3233/HSM-190574

- Nadler, L., & Nadler, Z. (1989). The Jossey-Bass management series. Developing human resources (3rd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Naim, M. F., & Lenka, U. (2017). Talent management: A burgeoning strategic focus in Indian IT industry. Industrial and Commercial Training, 49(4), 183–188. https://doi.org/10.1108/ICT-12-2016-0084

- Namey, E., Guest, G., Thairu, L., & Johnson, L. (2007). Data reduction techniques for large qualitative data sets, www.stanford.edu/Bthairu/07_184.Guest.1sts.pdf

- Namey, E., Guest, G., Thairu, L., & Johnson, L. (2008). Data reduction techniques for large qualitative data sets. In Handbook for Team-Based Qualitative Research. Rowman Altamira.

- Ogbonna, E., & Harris, L. (2006). The dynamics of employee relationships in an ethnically diverse workforce. Human Relations, 59(3), 379–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726706064181

- Paisey, C., & Paisey, N. J. (2016). Talent management in academia: The effect of discipline and context on recruitment. Studies in Higher Education, 23(7), 1196–1214.

- Pfeffer, J. (2001). Fighting the war for talent is hazardous to your organization’s health. Organizational Dynamics, 29(4), 248–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0090-2616(01)00031-6

- Ployhart, R. E. (2006). Staffing in the 21st century: New challenges and strategic opportunities. Journal of Management, 32(6), 868–897. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206306293625

- Powell, G. N. (2011). Women and men in management. Sage.

- Preece, D., Iles, J., & Jones, R. (2013). MNE regional head offices and their affiliates: Talent management practices and challenges in the Asia pacific. The International Journal of Human Resources Management, 24(18), 3457–3477. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.777676

- Reddy, S., Searle, R. L., Shawa, L. B., & Teferra, D. (2016). A balancing act: Facilitating a university education induction programme for (early career) academics. Studies in Higher Education, 41(10), 1820–1834. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1221658

- Roberson, Q. M. (2006). Disentangling the meanings of diversity and inclusion in organizations. Group and Organization Management, 31(2), 212–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601104273064

- Ross, S. (2013). How definitions of talent suppress talent management. Industrial and Commercial Training, 45(3), 166–170. https://doi.org/10.1108/00197851311320586

- Rudhumbu, N., & Maphosa, C. (2015). Implementation of talent management strategies in higher education: Evidence from Botswana. Journal of Human Ecology, 49(1–2), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/09709274.2015.11906820

- Schaafsma, J. (2008). Interethnic relations at work: Examining ethnic minority and majority members’ experiences in the Netherlands. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 32(5), 453–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2008.06.004

- Schuler, R. S., Jackson, S. E., & Tarique, I. (2011). Global talent management and global talent challenges: Strategic opportunities for IHRM. Journal of World Business, 46(4), 506–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2010.10.011

- Scullion, H., & Collings, D. (2006). Global Staffing. Routledge.

- Scullion, H., Collings, D. G., & Caligiuri, P. (2010). Global talent management. Journal of World Business, 45(2), 105–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2009.09.011

- Siebers, H. (2009). Post bureaucratic organizational practices and the production of racio-ethnic inequality at work. Journal of Management and Organization, 15(1), 62–81. https://doi.org/10.5172/jmo.837.15.1.62

- Simha, A., Elloy, D. F., & Huang, H.-C. (2014). The moderated relationship between job burnout and organizational cynicism. Management Decision, 52(3), 482–504. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-08-2013-0422

- Stahl, B. I., Farndale, E., Morris, S., Paauwe, J., Stiles, P., Trevor, J., & Wright, P. M. (2012). Six global practices for effective talent management. MIT Sloan Management Review, 53(2), 25–32.

- Stahl, B. I., Farndale, E., Morris, S. S., Paauwe, J., Stiles, P., Trevor, J., & Wright, P. M. (2007). Global talent management: How leading multinationals build and sustain their talent pipeline. INSEAD Faculty and Research Working Papers No. 34, Fontainebleau.

- Strack, R., Caye, J.-M., Teichmann, C., Haen, P., Frick, G., & Bird, S. (2011). Creating people advantage 2011 time to act: HR certainties in uncertain times. The Boston Consulting Group, Inc. and the European Association for People Management.

- Subbaye, R., & Dhunpath, R. (2016). Early-career academic support at the University of KwaZulu-Natal: Towards a scholarship of teaching. Studies in Higher Education, 41(10), 1803–1819. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1221657

- Tansley, C. (2011). What do we mean by the term ‘Talent’ in talent management? Industrial and Commercial Training, 43(5), 266–274. https://doi.org/10.1108/00197851111145853

- Tansley, C., & Sempik, A. (2008). Talent management: Design, implementation and evaluation. CIPD.

- Tansley, C., & Tietze, S. (2013). Rites of passage through talent management progression stages: An identity work perspective. The International Journal of Human Resources Management, 24(9), 1799–1815. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.777542

- Tansley, C., Turner, P. A., Foster, C., Harris, L. M., Stewart, J., Sempik, A., & Williams, H. (2007). Talent: Strategy, management, measurement. Chartered Institute of Personal and Development.

- Tarique, I., & Schuler, R. (2010). Global talent management: Literature review, integrative framework, and suggestions for further research. Journal of World Business, 45(2), 122–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2009.09.019

- Thunnissen, M., & Arensbergen, P. V. (2015). A multi-dimensional approach to talent: An empirical analysis of the definition of talent in Dutch academia. Personnel Review, 44(2), 182–199. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-10-2013-0190

- Thunnissen, M., Boselie, P., & Fruytier, B. (2013). Talent management and the relevance of context: Towards a pluralistic approach. Human Resource Management Review, 23(4), 326–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2013.05.004

- Vaiman, V., & Collings, D. G. (2013). Talent management: Advancing the field. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(9), 1737–1743. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.777544

- Vaiman, V., Scullion, H., & Collings, D. (2012). Talent management decision making. Management Decision, 50(5), 925–941. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251741211227663

- Valverde, M., Scullion, H., & Ryan, G. (2013). Talent management in Spanish medium-sized organisations. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(9), 1832–1852. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.777545

- Van den Brink, M., Fruytier, B., & Thunnissen, M. (2013). Talent management in academia: Performance systems and HRM policies. Human Resources Management Journal, 23(2), 180–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2012.00196.x

- Van den Broek, J., Boselie, P., & Paauwe, J. (2018). Cooperative innovation through a talent management pool: A qualitative study on cooperation in health care. European Management Journal, 36(1), 135–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2017.03.012

- Watson, T. J. (2009). Narrative, life story and manager identity: A case study in autobiographical identity work. Human Relations, 62(3), 425–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726708101044

- Williams-Lee, A. (2008, May–June). Accelerated leadership development tops the talent management menu at McDonald’s. Global Business and International Excellence, 27(4), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.20210

- Yeung, A., Warner, M., & Rowley, C. (2008). Guest editors’ introduction growth and globalization: Evolution of human resource management practices in Asia. Human Resource Management, 47(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20194