ABSTRACT

The paper offers the author’s vision of the political and organizational problem of using modern blockchain-based platform solutions in public governance. The aim is substantiating potential of decentralized information platforms as a new tool of public governance to promote conscious participation of people in public politics and democracy. Based on the study of the experience of the UK, Estonia, India, and Ukraine in platform governance, the author asserts that the modern world practice of using centralized digital platforms is conditioned by the comfort for citizens as the main value, thereby replacing the real democratic values. The paper offers an original comparison of 15 key parameters of platforms and author’s comparison of decentralized platforms with two other main forms of providing public administrative services by criteria as functionality, security, and cost. Unlike promising decentralized platforms, government centralized platforms are a mechanism for removing citizens from conscious governance by their states.

Introduction

Over the past decade, platform governance has become one of the main technology trends in the world. Representing hi-tech digital solutions, platforms offer a person such necessary benefits as simplicity of services, their wide geographic accessibility via the Internet, relative cheapness due to absence of unnecessary intermediaries, etc. Large technology corporations offering global platform solutions have already acquired an extraordinary economic strength and technical excellence and can already influence the policies of countries, while governments, on the contrary, regard platforms both as a means of organizing domestic policy and providing hundreds of public services, and as a threat to the state (government) monopoly on power, unless, of course, the platforms are state-owned and large.

Recently, hundreds of publications in various fields of science have been devoted to the topic of digital platforms; however, to us, political science works are of special meaning (e.g., Cheibub et al., Citation2010; Faguet, Citation2014; Janssen & Estevez, Citation2013; Atzori, Citation2015; Tura et al., Citation2018; Chen & Pereira, Citation2020, etc.). Even special departments have been created in intergovernmental organizations (OECD, Citation2019, Citation2020a, Citation2020b; UNCTAD, Citation2020a, Citation2020b, Citation2019) and leading think-tanks (Stigler Center, Citation2019; WEF, Citation2018, Citation2019, Citation2020) to study how information platforms and related digital technologies affect macroeconomics, fiscal sphere, and public relations. But none of the publications contains a clear medium- or long-term prediction of how public policy and governance will change owing to platforms.

Governments are sensitive to the platform trend and are actively working on public digital infrastructure to provide their citizens with simple and convenient access to services. Quite a few governments have decided to radically re-architect their processes and are opening numerous government registers that were previously closed to easy access. Probably, digital platforms have become an ideal means of such hierarchical interaction between the state and citizens. The pace and scope of platform introduction into public governance seem to create an illusion that the general concept and mechanism of platform management have already taken shape, and there is a certain status quo. There is even a widespread belief that the government itself is becoming a service platform (Cordella & Paletti, Citation2019; O’Reilly, Citation2010; Pope, Citation2019), and the future of the Government as a Platform concept is secured for at least the next 10 years, if not more.

However, at the same time, numerous countries (Germany, Australia, India, Kenya, Singapore) have expressly decided to take the path of large-scale implementation of blockchain technologies in the public sector. We should note that no one knows the exact limits of blockchain implementation, while everyone like its useful properties, which are more simplicity, trust, and transparency. Is this a mirage? This poses the question: what will happen, if the strict hierarchy of “the state–people” interaction implemented in the common state information platforms is decentralized through blockchain?

‘It is clear that what the government will not do, the private sector will: it will develop and implement 80 an interesting technology, offer simpler, cheaper, and faster services, which is a new alternative for nonflexible government agencies’ (Dunayev et al, Citation2020). Schumpeter’s theory of creative destruction is applicable again (Delong, Citation2014), however, this time, we should try to do it using blockchain. What is the challenge for the modern society? We believe that it lies in the fact that comfortable use of services in common hierarchical digital platforms is not a defining value and is offered as a deceitful “wrapping” for billions of ordinary people. Indeed, it is important, but not defining. If we can see that at the political and supranational levels, they are close to reaching a consensus that the future belongs to platforms and lies in using blockchain, then perhaps we should combine them into single technological solutions and show states how to regulate, cooperate, and use them? At the moment, blockchain-based decentralized information platforms seem to be the solution. Some major examples have already been developed and are functioning.

Paper aim and objectives

The aim of this paper is to substantiate the potential of decentralized information platforms as a new public governance tool to build public confidence and promote conscious participation of people in public politics and democracy. A number of objectives have been determined for this purpose:

to make a brief comparison of implementation of platform governance in in the UK, Estonia, India, and Ukraine;

to determine platform governance challenges each of the analyzed countries faces;

to compare decentralized information platform features with traditional state digital solutions;

to raise doubts about the widespread representative democracy being able to promote the creative initiative of people and engaging them in public governance and politics;

to offer an alternative solution to the above problem, which lies in implementation of decentralized information platforms and blockchain-based trusted private registers in public governance.

Methodology applied

The author’s research approach is based on the following five steps:

definition of the key terms, especially “information platform” as well as “centralized information platform” and “decentralized information platform” being very close to it;

brief comparison of implementation of platform governance in the UK, Estonia, India, and Ukraine establishes the factual basis for this paper according to the following logic: (a) main state platforms, (b) guidelines, (c) people’s attitude towards digital transformations, and (d) propagation of changes. However, this also requires explaining why exactly these countries have been chosen to make comparison. This will be done below;

synthesis of platform governance challenges each of the above countries faces and laying the groundwork for a new vision of digital transformation of national public governance systems;

comparison of uncommon decentralized information platform with traditional government digital solutions based on the centralized information platform and personal appealing of citizens to specialized offline centers of administrative services;

use of inductive method to take a critical look at the existing public governance from the perspective of democracy and preparation of related conclusions.

Definition of key notions

Before proceeding to the main provisions, we should define the key and special terms:

information (digital) platforms can be viewed as a kind of regulating environment, and as an anonymous governance subject based on program code. It allows private developers, users, and other people to interact, exchange data, services, and applications, while governments that have implemented providing certain administrative services through information platforms, may monitor processes more easily, and facilitate the development of simple and innovative solutions and services;

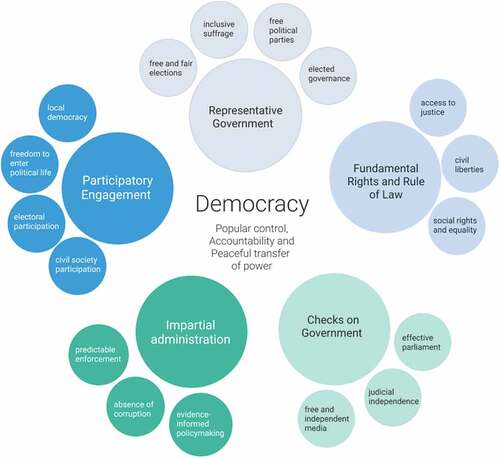

the idea of an information platform is to create a society and then support it using digital services, while having getting profit from reduced transaction costs through partially eliminated intermediaries as a managerial consequence (Dunayev, Citation2020, p. 278), as well as increasing coverage, and ensuring adequate peer supervision by users and owners of such a platform ();

decentralized information platform (DIP) means “a type of digital data accounting system based on a distributed ledger technology, which consists of a service infrastructure and a community of independent users having equal rights or pre-identified rights granted according to the levels of decentralized governance model to make such a system stable” (Kud, Citation2021; see the Table in );

key features of a centralized information platform (CIP) are as follows: 1) governance is based on acquired rights in the hierarchy; 2) the centralized coordination method creates additional added value for owners or higher ranks in the hierarchy, which indicates the priority of “economics over politics” (Explanatory note, Citation2019); 3) governance based on market rules and rights in the hierarchy; 4) emphasis on hierarchical web networks with or without clear territory relation and on online interest groups; 5) asymmetry of information for participants, owners, “nodes” managers; 6) the main evident benefit is easy, quick, and convenient use of services through the platform as an intermediary; 7) it exists in a dilemma of choice between secure transaction protection and personal data protection, confidentiality and censorship (Pereira et al., Citation2019); 8) relatively low complexity of building and maintaining the viability of the platform (see the Table in ).

Figure 1. The general logic of using information platforms within the caring governance concept (Janssen & Estevez, Citation2013).

Substantiation of the choice of countries to study

As for Ukraine, since the author of this paper is Ukrainian, resides in Ukraine, and is engaged in modernization of public governance in this country, the Ukrainian example has been chosen as basic to be compared with foreign counterparts (the UK, Estonia, and India). At the moment, Ukraine is facing accelerated digital transformations, and governmental digital platforms are being implemented here.

Regarding the UK, back in 2015, its government officially announced in its digital strategy of creating a Government as a Platform (GaaP) as a main approach to providing digital services. The UK Government Digital Service (GDS) has been actively taking platform governance measures for over 13 years, while other developed countries (the USA, Canada, Australia, and the South Africa) have modelled their government digital services after the GDS. In 2016, the United Kingdom was ranked first in the world in terms of digital government development by the UN precisely because of the platform approach.

As for Estonia, experts believe that it is the most “digital country” in the world, where at least 99% of public services are provided online. According to the Estonian government, it saved 800 labor years for the government, its authorities, and citizens.

Regarding India, its government’s unique identification number programme is ranked first in the world in terms of coverage among similar platform initiatives. Today, 1.26 out of the total of 1.31 billion Indians have their personal Aadhaar number used for address delivery of all budget payments and public services. Another governmental centralized information platform, Digital India, has significantly revamped the way all business processes are managed when services are being provided to citizens.

Results

We should begin with a brief review of implementation of state information platforms in four countries.

A brief review of different countries’ implementation of digital platforms

A1. The UK’s experience

The UK is the first country in the world to officially adopt “Government as a Platform” (GaaP) as a digital strategy for providing government services. In the UK, in the 1980s, Margaret Thatcher’s government tried to use the potential of technology to improve public services. This coincided with the era of “new public management”, when the government, with varying success, tried to apply business practices in the public sector for the sake of efficiency. Despite the fact that citizens were considered “customers”, they could not receive services in full and anywhere, since state authorities were still service monopolies (Brown et al., Citation2014).

1. The main governmental platform initiatives of the UK. The GDS was established in 2011 as a special unit for the improvement of public services under the Cabinet of the United Kingdom, and in 2012, the government adopted the first Digital Strategy. It included 14 actions to make the government “digital by default”: digital services must be as easy-to-use as possible, and everyone who can use them, will enjoy it. At the same time, those who cannot use them, will not be excluded, but will join afterwards (Singla, Citation2019, pp. 30–32). In particular, Clause No. 11 of the Digital Strategy describes development of common technological platforms for “digital services by default”: to develop services on platforms instead of in elevator s. For this purpose, the Cabinet of the United Kingdom will develop and introduce a new set of common technological platforms to support the new-generation digital services, while the Government Digital Service will: a) extend the range of information platforms for digital display, data analysis, personal identification, and future shared platform components (UK Digital Strategy, Citation2017); b) determine, process, and introduce common technological platforms to support digital services by default; c) develop a data analysis platform to combine a range of data, in particular, analytics, web operations, and financial information. It was announced in March 2015 that GaaP would become the main point of the next stage of the UK’s digital transformation.

This vision is being implemented owing to the main components of the platform concept – single central portal GOV.UK providing access to all government services. Today, all UK government’s departments and almost 400 other agencies and government bodies use it instead of DirectGov and Business Link to deliver government services to the UK citizens (Welcome to GOV.UK, Citation2021). All these departments and institutions’ websites can be found on GOV.UK (Singla, Citation2019, p. 37).

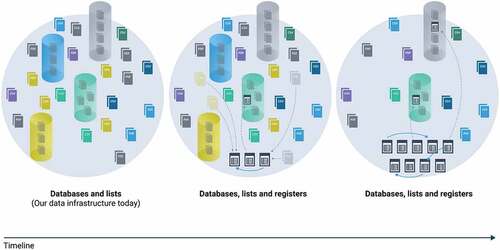

In addition to the many features of GOV.UK, registers are of particular interest for the purposes of this study. Thus, GOV.UK Registers is a strict set of possible government data, in which each register contains only specific data updated by an expert organization. For instance, the countries’ registers list all countries recognized by the UK government. Services that use registers can reduce the time and cost of obtaining data from government agencies, get ready-to-use data without the need for data cleansing, and ensure that their service is using the most up-to-date government data. Managers of data who create registers only need to publish it in one place, and it is updated automatically.

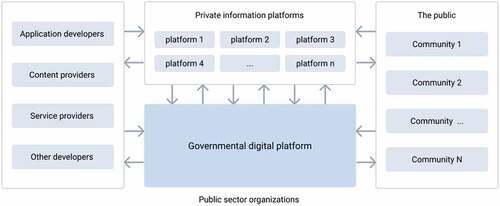

Such registers may include either those that contain public data and are publicly available, or closed ones that require users to do something before getting access to data, or private ones with confidential information. At first, before entering data into the GOV.UK Registers database, it was necessary to solve a number of difficult tasks for synchronizing data and updating old registers. Subsequently, GOV.UK Registers solved all of the above issues, simplified, and standardized the way of saving, storing, and accessing data in various services. Today, this service offers reliable, accurate, and up-to-date data at any moment. This data is of required format and consistent in terms of content. Anyone now may get access to all registers and use it according to one’s needs. The common API protocol can be used to obtain the latest data from the register. Citizens can see which government services are already using registers, and which have created a register with their data ().

Figure 2. The structure of www.GOV.UK, an open register ecosystem.

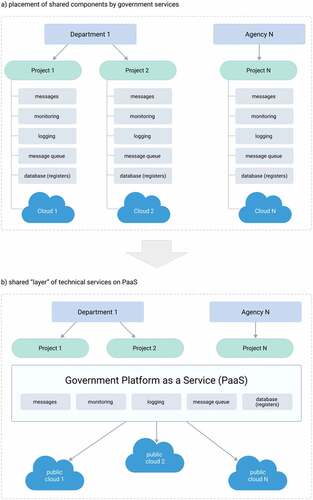

GOV.UK Platform as a Service (PaaS) is a shared web hosting for the UK government services. Each digital service used by the government should be hosted. Arranging and setting all components for hosting a service requires much effort and spending, even though these components are not very different and groups of such components of different services look quite alike (). This means that (a) state bodies may in fact repeat actions already performed by other body for its needs; (b) such bodies cannot focus on their primary tasks and will spend time and resources for such minor actions as monitoring applications, aggregating e-logs, analyzing technical errors, etc. A shared cloud-hosted Platform as a Service (PaaS) may solve these issues. A shared PaaS can provide such a level as shown in -b. It is clear that the preparation of the processes for acquisition of commercial services and their accreditation takes a lot of time, therefore, even during the implementation of PaaS, the British prepared and evaluated several models of business processes, which made it possible to form a certain universal approach for subsequent (or other) digital services

Figure 3. The structure of shared web hosting for UK government services without repeated administrative and technical resources (Singla, Citation2019, p. 34).

2. Guidelines for building a government service information platform. The GDS service design principles are as follows:

“Start with user needs”.

“Do less”, that is, the government should only do what it can do and focus on the minimum sufficient “core”.

“Design with data”.

“Do the hard work to make it simple”.

“Iterate. Then iterate again”, that is, iterate in test mode with a minimum set of services.

“It is for everyone”.

“Build digital services, not websites”.

“Be consistent, not uniform”, making the most of the same design templates (Singla, Citation2019, pp. 38–39).

3. Society’s attitude. Every year, the British study their citizens’ views of how digital services are changing their lives based on annual representative online surveys of 2,000 people, 500 phone calls, and focus group conversations (People, Power and Technology, Citation2018). Back in 2017, 91% of the UK population had basic digital skills to access the Internet, and these skills were counted along with literacy and counting skills as key elements of a British education. 80% of the people surveyed answered that their daily tasks became much more convenient; 69% believed that digitization provided an opportunity to try new things, meet new people and learn something new; 52% of respondents found that they used social media to connect with family and friends. There is still a large gap in understanding digital technology. Only a third of people were aware of the fact that the data that they did not want to share was still collected and stored somewhere on the server; also, there is only a partial understanding among the British of how state and private companies make money from digital products and services for people. However, people demand that technology be more accountable and responsible, while the poor are much more sensitive to controversial issues of ethics, fairness, and find compromises on these issues unacceptable. However, the British in general remain full of faith in the potential of technology and the rapid transformation in their lives.

4. Propagation of changes. As of February 2021, over 200 government services were using government centralized digital platforms, and in the previous year, 2020, these platforms ensured the transfer of more than 44 million messages through GOV.UK Notify as well as the transfer of more than 110 million pounds paid through GOV.UK Pay (Singla, Citation2019, pp. 39–40). While there are hundreds of digital services on GOV.UK, PaaS offers 19 services based on personal data from public registers, and 36 registers are available for public and free use. The GaaP concept has become the ultimate “default choice” for nearly 99% of all government services, agencies, and departments in the UK. With the increase in the number of online services, their use by citizens has already become the norm. While in 2007 only 30% of British adults used online banking, in 2017 this share was 63%, and almost 79% in 2020. Digital transformation has saved over £50 billion in five years since its launch, mainly due to reduced government operating costs (CEBR, Citation2018).

A2. Estonian experience

Estonians created their “digital nation” in less than 20 years making 99% of government services available online for Estonian citizens. These online services provide significant time and cost savings not only for users, but for the government as well (e-Estonia – we have built a digital society – and so can you (“e-Estonia guide,” Citation2016)). It is important that Estonia has reached such a level of service provision not through the creation of several web portals, like the UK, or the addition of digital technologies to the existing organizational structure and processes, but through the systemic redesign of its entire information infrastructure based on the principles of openness, confidentiality, and security.

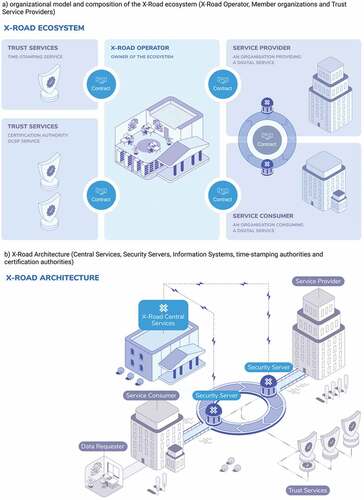

1. Estonia’s main governmental platform initiatives. The concept of Government as a Platform was not a clear model for the development of Estonian digital government, however, their system is clearly similar to a digital platform due to its digital government service infrastructure, which is public and mandatory. Estonia has developed three levels of the platform concept: 1) a registers and data exchange system that allows departments and agencies to exchange data (X-Road); 2) digital and mobile identification system (e-ID); and 3) the “layer” of public services, which is accessed through a special state web portal (www.eesti.ee).

First, X-Road is designed to provide secure communication between different databases, processes, and technologies used by different departments and agencies when delivering services. This is a secure level of data exchange on the Internet, which allows different information systems and state registers to seamlessly exchange data with each other. X-Road acts as an application development platform and facilitates a government agency to easily expand its physical services into an electronic environment. Estonian services, utilities, and private companies (e. g. energy, telecommunications, banking) maintain their own registers, but also allow other public authorities to gain secure access to them. Citizens can use a single password to access various government websites.

shows the X-Road structure. It also demonstrates that X-Road is a fairly decentralized information system for data exchange, however, the data belongs only to those institutions that join X-Road. X-Road does not monopolize individual registers, but it is important for X-Road that each such institution shares its data with others as needed. Each member organization and application developed is encouraged to use the same data that is stored in the registers of other members (i.e. cross or network principle) to avoid duplication in collection and confusion for the end customer. Since the exchange of data allows members to develop even more convenient services, X-Road is constantly pushing its members to reusing data. All this makes the state X-Road attractive for both individuals and legal entities of public law.

Figure 4. Organizational model and technical architecture of the Estonian X-Road.

In addition to basic citizen–government interaction, X-Road is also suitable for executing queries from various authorities to various registers (databases). For example, checking car registration data requires obtaining data from two different registers, which are the population register and the vehicle register. According to the State Information Administration, previously, such a simple request required the involvement of three civil servants (e.g., police officers), who processed it in total up to 15 minutes, but with the X-Road, only one police officer spends 30 seconds for the entire search for information (Singla, Citation2019, p. 41).

Second, the electronic ID (e-ID) based on the national authentication and digital signature system of the public key infrastructure (PKI), which is used as a “container” for certificates. The secure system of identification and authorization allows each user of services from the public and private sectors to identify himself/herself in the system using digital signatures (Singla, Citation2019, p. 42).

Third, the Eesti.ee platform: citizens have been able to access more than 800 services on the official e-Service portal since 2003. After full registration, any citizen can see who, when, and why accessed his/her data, since all changes in and access to data have a digital “footprint” (Solvak et al., Citation2019). As a rule, Estonian government services are prohibited from storing the same data in more than one place. The basic personal data of each person (e.g., unique identifier, name, date of birth, parents, gender, address history, citizenship, and legal relationships) is the most obvious example of this. A profile of any person’s basic personal data does not require storing data in different separate registers: only a unique identifier and distributed data registers are needed. This ensures a high level of data protection, since there is no such place where all information about someone is stored. In addition, such digitization allows visualizing the family tree of almost any person up to about 1950 (Estonian, Citation2016). It should also be noted that Estonians can see who viewed their data, but viewing other people’s data without permission is prohibited, all operations are recorded. For instance, you can see that a doctor and pharmacist have looked through a patient’s medical record, and there is no paper circulation for this. Technically, it is possible that some official was able to secretly gain access to personal data, however, the developers of this system expect that personal data is protected not only technically by the system, but also deliberately by the citizen himself/herself through the access rights management.

Fourth, the e-Residency platform. It is blockchain-based and the main result of the Estonian government’s experiments with this technology to validate records in government databases, such as birth and marriage certificates. The platform has introduced the concept of e-living as a form of transnational digital identity; e-Residency is available to everyone in the world who is interested in using Estonian online services, opening a bank account or starting a company. Electronic residents can apply to open a bank account, conduct online banking, declare taxes, remotely sign documents, and gain access to international payment operators. The American Stock Exchange NASDAQ cooperates with the Estonian e-Residency in terms of confirming secure electronic voting at shareholder meetings for listed companies (Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) and Blockchain, Citation2017, p. 33).

2. Guidelines for building a government service information platform:

The once only principle.

No legacy principle. As a rule, public digital infrastructure should not use technological solutions that are more than 13 years old.

Build versus buy principle.

Interoperability and security principle. Instead of striving for the creation of centralized databases and information systems, the main focus should be on the secure interoperability of data systems with a high level of compatibility.

Actors’ roles and responsibilities. The digital government service actors in Estonia are politicians, executive authorities, private sector companies, citizens, etc. (Singla, Citation2019, pp. 45–46).

3. Society’s attitude. The extremely high loyalty of Estonians to digital public services is based on compulsory IT education since kindergarten and the purposeful development of IT skills (e.g., using a computer at home, searching the Internet, etc.) among adults, which since the mid-1990s was one of the priorities of the government. People were also influenced by propaganda about the opportunities and threats of the information society and technologies with special attention paid to safe behavior on the Internet.

The Estonian government’s website, e-Estonia, says that, according to the Wired, Estonia ranked first in terms of the level of development of a digital society, in which 99% of services are provided to citizens in digital form. There are only three services left in the country that cannot be received via the Internet: getting married, divorcing, and purchasing real estate. Since gaining independence in 1991, the citizens trusted the authorities in the reform process, and that is why the government was able in 1999–2002 to initiate and implement the digitization of registers, and the first digital service was introduced in 2000. Also, the high people’s loyalty and the widespread acceptance of digital services were a consequence of the initial ease of use of services for various categories of the population, especially those with disabilities. The level of Internet use among the adult population increased from 29% in 2000 to 98% in 2020. Since 2000, the right to access the Internet has been included in the list of basic rights of Estonian citizens. Now at least 95% of the population file their tax returns online and 94% of the working-age population use Internet banking (“Digital Agenda” , Citation2016). In kindergartens, children are taught digital skills, and at the age of 7–8, children can already code their simplest games. IT classes are compulsory in schools. There is also a state advanced training program for all postgraduate students of Estonian universities with internships in local IT firms to develop their technical skills (Barbaschow, Citation2018).

4. Propagation of changes. Owing to platform initiatives and digital services, small Estonia has become a rare example of how to create a new viable niche in the international division of labor. Counting on this, during the 2010s, the country actively promoted itself as a place for labor migration for qualified specialists from post-Soviet countries, especially technical and IT specialists, and as a European “tax haven” (until 2018–2019). Of course, digitalization has given people a higher quality of life, and government services have become 100% available to anyone throughout the country. Digital technologies have helped create new professional communities, new companies, and digital governance start-ups; new jobs with high added value were created for citizens of different countries in Estonia.

A3. Indian experience

Digital India Programme is aimed to transform India into a society with digital power and a knowledge economy. Digital India e-governance ensures broadband for all, IT education, and telemedicine. The original budget for the Programme was Rs 11.3 billion in 2015 and increased to Rs 30.7 billion in 2018–2019. In 2017, this became an important factor for the growth of India’s ranking in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Index – from 142nd in 2015 to 77th in 2018. India is investing heavily in digital infrastructure becoming the world’s second largest mobile phone number country. However, as in many other developing countries, technological progress is outstripping the development of policy and innovation in public governance (Gupta & Auerswald, Citation2019). The push for electronic governance began with the launch of NICNET in 1987, a national satellite computer network. Thereafter, the program for District Information System of National Informatics Centre (DISNIC) was launched to computerize all district offices in the country. The introduction of the National e-Governance Plan (NeGP) in 2006 can be viewed as the second phase of e-Governance in India. The flagship project of NeGP aimed to create 100,000 Common Service Centres across India (one for every six villages). This aim was achieved in 2016–2017 (Singla, Citation2019, pp. 50–52).

1. India’s main governmental platform initiatives. In 2010, India embarked on an ambitious project to provide a unique, permanent, and secure digital 12-digit identification number to all of its residents through the collection of demographic and biometric data. Taking into account the potential of digital innovation and the widespread coverage of Aadhaar, many different open-source application programming interfaces (APIs) have been developed for several years, in particular e-KYC, e-Sign, Unified Payments Interface (UPI), DigiLocker, and Aadhaar Enabled Payment System (AEPS). Aadhaar bank account, Jan Dhan, and mobile phone access (JAM) together laid the foundation for the national centralized India Stack platform.

India Stack is a name given to a system of open API protocols (Aadhaar, UPI, e-KYC, e-Sign, DigiLocker owned by various government agencies in the country), which in turn allows government, companies, entrepreneurs, and developers to use the unique government digital infrastructure by providing non-cash services. India Stack can be viewed as a pyramid that has identification and authentication through Aadhaar (bottom), then Digital Locker for documentation, then Aadhaar-based electronic sign, and UPI (Unified Payments Interface) for payments at the top of the pyramid. Aadhaar (unique identity) has largely solved the problem of providing trust services in various spheres of life, especially in the field of settlements with the state. Effective government service delivery has become one of the core principles in the development of India Stack (India Stack, Citation2018).

Among the four major levels of India Stack, the consent layer should be noted. The architecture of electronic consent layer provides user-driven data exchange, data flow, and data storage. The consent layer is designed to allow citizens to ensure their consent in the data flow between data providers (banks, hospitals, and telecommunications companies) and data requesting parties (banks and credit card providers). For instance, if a person wishes to apply for a credit card, he/she can provide his/her bank with consent to transfer the relevant documentation to the credit card issuer to check his/her creditworthiness before the credit card is issued.

In addition to India Stack, other important platform initiatives should be noted:

A. Platform as a Service (PaaS) from the National Informatics Centre (NIC) provides a technological centralized platform for hosting websites, portals, and web applications. PaaS offers a variety of service models and provides remote and secure cloud servers for preinstalling web versions of private websites and running web applications allowing everyone not to have their own server or configure it. PaaS can be used to quickly deploy servers and publish web applications. NIC also grants operating system and application software licenses.

B. Open Government Data Platform (OGD): data.gov.in is an open data initiative by the government of India. This platform is one-point access to government registers, services, tools, documents, and applications of all federal authorities in India. It also consolidates and extends the advantages of India.gov.in project of the Indian government and data.gov project of the US government.

C. The MyGov.in platform aims to engage citizens in active development of the state by encouraging them to participate in groups, tasks, discussions, polls, blogs, and conversations. The government of India has begun involving its citizens to facilitate the active participation of Indians in the governance and development of the country. The project is aimed at crowdsourcing the ideas of ordinary citizens to govern the country and reduce the gap between voters and the elected government.

D. The Goods and Services Tax Network (GSTN) provides a common platform for the federal and state governments of India, tax payers, and other stakeholders to administer the payment of goods and services tax. GSTN uses the API protocol and other hardware and software systems required to manage federal goods and services tax settlements. GSTN, as a non-profit organization, is partly owned by the Indian federal and state governments. GSTN offers a single interface for taxpayers and shared IT infrastructure between the federal center of the Republic of India and the states of the Indian federation.

2. Guidelines for building a government service information platform:

Design for the user.

Based on the ecosystem: the entire technological infrastructure should be based on this ecosystem principle, while all services should be Aadhaar-based.

Simple and minimalist.

Open APIs, open data, open source, and open innovation.

Core functionality.

Design for scale. Over 1.2 billion Indians using Adhaar and related services have an enormous potential to scale services, therefore, all instruments should be created while taking this into account.

Collaborative (Principles for digital development; Singla, Citation2019, p. 55).

3. Society’s attitude. The introduction of a unique biometric identification system in India since 2010, the demonetization of monetary circulation in a non-cash form since 2016, and a new tax on goods and services since 2017 together caused the society’s need for digital integration, and accelerated the transition of the Indian public governance system to new standards of service delivery and budgeting. In India, more than 9 million electronic checks of the status of an individual during settlements (through e-KYC) are carried out every month using the state centralized information platform Aadhaar. While in 2010 electronic payments through mobile wallets accounted for no more than 0.3% of all electronic transactions, their share was 15% in 2018, and 23% in January 2021. In just one month (November 2017), citizens uploaded about 13 million official documents (e.g., a driver’s license) to DigiLocker (Borah, Citation2020).

Since the beginning of demonetization in November 2016, the volume of online payments had been growing exponentially according to the UPI. After the demonetization of cash circulation, the number and amount of deposits increased significantly in bank accounts, more than 90% of which were small accounts and with very small payments.

There are now over a billion mobile phones in India, which gives Indians a fairly cheap opportunity to view text and video content anywhere. The introduction of electronic teaching aids in schools and technical schools has allowed 0.4 billion young people to comfortably learn the skills that can later be monetized. On average, an Indian smartphone user downloads over 9 gigabytes of data per month, more than users in the US, China or Japan.

The widespread implementation of Meghraj cloud initiative to provide an India-wide broadband Internet access platform for rural India and software has enabled 100 large Indian cities to strategically pursue their development as smart cities, which is a significant step towards public governance, and also involving significant funds from the budgets of large cities for these purposes. The country has created related e-service platforms, namely eTaal (digital interface for government subsidies and social programs), e-Hospital, and e-Sushrut (information systems for health care and insurance on the Internet), eNam (online trading platform for agricultural products of poor farmers throughout India) and Jeevan Pramaan (for retirees). The nationwide India Stack has significantly reduced transaction costs and corruption in the provision of a wide range of government services such as training grants and social transfers (Singla, Citation2019, pp. 57–58).

4. Propagation of changes. India’s sole identification authority has identified Aadhaar as a strategically important government policy tool in government sector reforms. In fact, it has become a tool for distributed equity and a new tool for financially attracting hundreds of millions of Indians from disadvantaged groups. Its open API protocols have become the basis for an ecosystem of services such as e-KYC, digital signatures, and instant payment infrastructure. In particular, e-KYC (electronic Know Your Customer) has reduced the cost of counter-operational verification of parties in financial transfers from $23.43 to $0.16, or 146 times. Before Aadhaar, hundreds of millions of Indians were not considered economically desirable customers for banks and large retail chains. Owing to Aadhaar, this tool (e-KYC) also became one of the key factors in the opening of more than 317 million new bank accounts between August 2014 and December 2020, which allowed hundreds of millions of Indians who were not previously serviced by banks to enter the official economy and the official statistics of India (MEIT, Citation2018).

Digital India has definitely influenced the life of all Indians covering all sectors of the economy and all corners of the country, which made it possible to significantly reduce government and private administration costs, make big data available for analysis in real time, ensure fast movement and verification of information, in particular, for the needs of political governance of India, which was not the case before.

A4. Ukrainian experience

Now let us consider the experience of Ukraine in the digital modernization of public governance, in particular, through introducing information platforms and expanding access to registers.

When Volodymyr Zelenskyy became the President of Ukraine in 2019, the Ministry of Digital Transformation of Ukraine was established, one of the tasks of which is to digitize all government services in 5 years creating an integrated mechanism that would make all departments and accessible services available online.

1. Ukraine’s main governmental platform initiatives: mobile application Diia (https://diia.gov.ua/), separate portals for sectoral groups of services (Diia.Business, Diia.Center, Diia.City, Diia.Digital Education, Vdoma, etc.), the purpose of which is to create a “digital state” and “transfer the country to a smartphone.” In February 2020, the application for public digital services Diia, which allows receiving government services online, became publicly available. It was planned to digitize the top 50 most requested services during 2020 (registration of private entrepreneurs, companies, e-maliatko, services for carriers and builders, services for car owners, etc.) (Pischulina, Citation2020). The mobile application Diia may become the main application for all Ukrainians in about several years. The Ministry of Digital Transformation of Ukraine seeks to transfer all government services there adding not only digital copies of documents, but also dozens of government administrative services that can be technically and organizationally provided online to one degree or another. It was through Diia that at the end of 2020, thousands of private entrepreneurs were able to receive financial aid from the government. The subsidiary project Vdoma was being prepared to become a politically important state digital tool in the fight against the spread of COVID-19 in Ukraine, but, unfortunately, it did not (Gritsyk, Citation2020).

At least during the first year of Diia operation, the technical approaches implemented in it significantly outstripped the regulatory framework in the field of information security: now, Diia uses Amazon Web Services (a commercial public cloud supported and developed by Amazon since 2006) with load balancer that also deals with DDoS attacks.

2. Guidelines for building a state service information platform. Four principles have been defined: the state that helps, the convenient service of government services, against the digitalization of chaos, a system with a person at its core (MinTsifra, Citation2019).

3. Society’s attitude. During February–December 2020, Diia was downloaded 5 million times, a dozen of personal documents and over 30 services became available online. E-documents gradually come into use – they are already accepted at airports and post offices, vehicle owners may leave at home not only their licenses and registration certificates, but insurance policies as well. However, this has been going through a number of technical and organizational problems due to individual contractor partners, incomplete legislation, and inconsistencies in registers and software. It is worth noting the failure of the state approach to dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic with the help of Vdoma: back in December 2020, Ukrainian border guards at airports did not ask to install this application due to the ineffectiveness of this political and managerial solution for the remote control of the movement of Ukrainians (Gritsyk, Citation2020) amid lockdown.

4. Propagation of changes. Synchronization of the “transport” and “demographic” registers turned out to be the most effective solution. The main problem of using Diia is that this application exists in the architecture in which it is now, because Diia can access all connected state registers, receive information while operating on an almost unprotected channel. Diia is a state centralized “register of registers”, which is a repository of all data and state documents about a citizen and by-laws for this. When information is concentrated in one place, it is a huge temptation for attackers – valuable information should not be stored in one place, even if it is well protected, because everything can be hacked. It’s just a matter of time and resources.

The above analysis will have its logical conclusion below. In particular, based on the experience of the UK, Estonia, India, and Ukraine in the implementation of centralized information platforms in state governance, challenges and current risks will be synthesized to ensure democracy in modernization of the public governance system, and inductive conclusions will be drawn for updating the DIP-based public governance system.

B. Challenges based on the experience of implementing digital platforms

Challenges for the UK. Despite the success of the UK digital system in the population coverage, simplicity, and technically almost excellent delivery of services, it should be noted that none of the UK government platforms allows for any creativity, initiative, and entrepreneurship from ordinary service users, which are thousands of times more than application developers and online entrepreneurs for the platforms mentioned. Even British globalist experts admit (Ross, Citation2019) that although there are many talented and brilliant professionals in the UK government who know the answers to difficult questions, these people are not empowered to initiate and advocate for change. Furthermore, the path dependency, including the dependency on well-known platform analogies and the “near-perfection”, and the difficulty in introducing new digital organizational mechanisms that would be based on existing digital platforms, are really complex and still unresolved problems even for the British. The complexity of the “legacy system” (Ross, Citation2019) in the form of the existing centralized digital platform and its limitations in ensuring exercise of a wide range of human rights can be considered an obstacle to the implementation of continuous, more democratic, inclusive, and truly holistic e-governance. Those new political theories around the idea of direct democracy, the authors of which were the British, have been recently poorly aligning with the GDS’ “old” centralized digital platform analyzed above. However, in our opinion, DIP-based governance, including in terms of strengthening direct democracy, is one of the solutions to this problem.

The identified challenges for Estonia based on the experience in the implementation of platforms.

Firstly, the Estonian experience of overcoming the consequences of the 2007 cyber attacks on key state infrastructure made the whole world pay close attention to this threat and constantly invest in digital infrastructure and personnel training.

Secondly, the distributed data storage approach applied by the Estonian government authorities does not eliminate the danger of malicious distortion or deletion of data: the strategic choice would be to store it using a distributed ledger (blockchain) involving as many trusted private resources as possible, including private big data registers. Also, new digital solutions have not yet been formed into a shared infrastructure: the related decision has not been made yet, because this requires choosing between data consolidation and interoperability. In this case, it will be possible to better assess the impact of digital solutions both on saving state resources and the risks for the whole society.

Thirdly, even after gaining a foothold in the niche of technological innovations and significantly updating the system of its public governance owing to this, Estonia did not ensure itself a place among the leading countries of future innovations (including in terms of the Internet of Things, artificial intelligence for computing, and big data analysis), and “disruptive innovations” (Mesropyan, Citation2018) such as blockchain. On the one hand, this will inevitably require new concentration of resources and decentralized governance. The variable curve of technology leadership may further “bypass” this country. On the other hand, the entire population of Estonia (1.32 million people) should be more involved in the general and proactive governance of their country rather than be content with the convenience of expressing their will at the next elections every 4–5 years and with simple access to all services that already exist today.

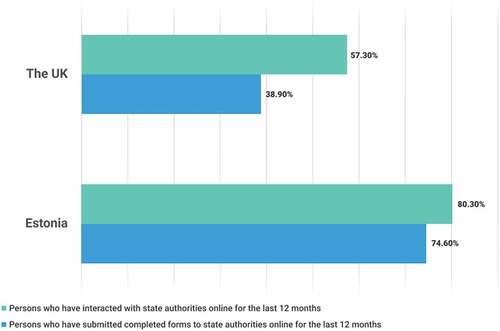

This all indicates that the current declared “decentralized system of services” and databases in Estonia is de facto part of the centralized state platform, where everything is well done for human comfort, at least if going “from top to bottom”, but not everything is done in order for a citizen to start interacting with another citizen as equal members of society, that is, there is still significant space for social and political networking of conscientious citizens (). Therefore, the challenges of including not just Estonian residents, but citizens in the digital framework of the near future are still unresolved for the Estonian government, if the government is really aware of this.

Figure 5. Comparison of the UK and Estonia on the two indicators of e-governance adopted in the European Union and being the closest to the citizen–state interaction (according to Eurostat, 2021; based on (EU Digital Agenda data, Citation2021)).

The identified challenges for India based on its experience in the implementation of platforms lie rather in the investment and technology as well as educational planes than in the democratic one. India, a country where a rigid caste structure of society has existed for millennia, will have a very different context for digital transformation than Ukraine, the UK, and Estonia. Digital infrastructure, maintenance, and the required level of government capacity to support modernization are the issues the Indian government is facing in promoting digitized services. Solving such state problems as building the required digital infrastructure for people to access digital services, overcoming digital illiteracy and the digital divide, and ensuring easy access to digital services are directly related to the organizational and financial ability of the authorities to provide people with broad access to high-speed data. Despite the achieved success, the Internet coverage in rural areas is no more than 20%. As a result, state governance mechanisms need to be significantly improved in terms of better administration, stakeholder engagement and coordination, and better alignment with the new digital culture.

India’s Unique Identification Number (UID) platform initiative, which was the first milestone in a series of all subsequent additions to the service, is somewhat similar to the UK’s GOV.UK Verify and Estonian e-ID, but the Indian initiative has much more potential than the other two. Despite this tool being progressive for India, we should note the problem of its conscious and proactive use by poor uneducated and poorly educated Indians, of whom there are tens of millions. Today, the UID platform is more useful to the authorities due to financial discipline and targeting than for millions of people who simply do not have basic and computer literacy skills. In this case, the issues of democracy and human rights are secondary.

It should be noted that Estonia and the UK are facing similar challenges regarding support for popular initiative, citizen interaction, and conditions for social capital (trust) through unity rather than individuality. Probably earlier, at a time when e-governance was being designed in these countries, this absolutely corresponded to that hierarchical human-centered paradigm of building “comfortable” public governance and, accordingly, the format of services “from state to person”. However, at the moment, digital technologies are increasingly offering new formats of communication between people, almost without involving the state, which can push out the “ordinary” state without reducing the “comfort” of services. Therefore, one should point out the development of such new public governance decisions that would bring people closer to one another rather than separate them, because it is such scarce solutions that are becoming much desired in the 21st century, and not just comfortable ones ().

Table 1. Generalizations of digital challenges of the analyzed countries for further digital modernization of the public governance system.

C. Request for new public value from platforms

shows that the state centralized platforms of the UK, India, and Estonia, which fully embraced the horizontal and vertical levels of governance, have already created conditions for both the scientist and the statesman to see a different perspective beyond the “narrow” interests of one influential stakeholder (a private company or a political party within a short political cycle) with a shift towards the common interests of the whole society for ten or more years. That is, it is like a new vision of group dynamics. Existing government bodies are unlikely to want to share their powers and control with new private organized participants that can not only use digital platforms, but even offer a simultaneous alternative in the form of an ecosystem of services for the ordinary citizen, which will be formalized and deployed as a private centralized or decentralized information platform. At the moment, this is already a reality in the world, and the state (government) can no longer prohibit it. However, if we proceed from the creation of a new common value, from common interest, from an attempt to strengthen trust and social capital in modern society, which is now defragmented by technologies and crises, there is a need to create interdepartmental and inter-hierarchical groups in existing state platforms with new institutions in order to ensure better acceptability of changes.

Given the generalizations made from country challenges above, a new layer of public services with a new common value could consist of parts of the public and private sectors with both the central and local authorities involved. So, on the one hand, this would make these relations more complex, multilateral, and less hierarchical, and on the other hand, in the short term, it would make the relations non-chaotic, ordered, and more regulated, in particular, due to the use of program code as an additional source of law (to some extent) along with the current legal law. The problem of trust between the participants has also been and is critical, since the components of the overall system can be easily used and transferred to third parties, and in this case, certain deception “protectors” are needed. This presupposes the establishment of new standards for public services and benefits, the development of relevant laws and especially the sub-legal framework.

According to the platform model, the government can be the first to form a wider and deeper network of mutually beneficial public relations as a “tangle”, and not as templates of vertical and horizontal-vertical structures as is now happening in the four countries studied above. The state power would feel as a single whole with its society, and some of the lines dividing the central, regional, and local levels would disappear, since some of the state functions will be transferred to trusted private participants organized and guided by by both the law and the program code in DIP.

D. Examples of cross-sectoral digital platforms with the private sector

In this sense, it is necessary to point out the latest initiatives in the form of global cross-sectoral, inter-institutional information platforms, which were formed by the governments of several countries or international organizations for the sake of greater confidence in solving complex common problems

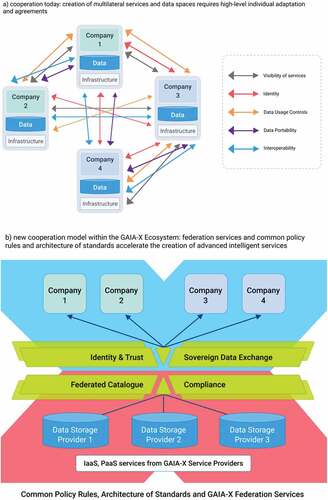

1. GAIA-X (www.data-infrastructure.eu/GAIAX), which is based on the principles of digital sovereignty and self-determination, authenticity and trust, European principles of data protection, modularity and interoperability, user friendliness, openness and transparency, as well as free market access and pricing in Europe. During its development, the main focus was on the users’ needs. The GAIA-X Platform Initiative seeks to align different providers across an infrastructure ecosystem based on portability, interoperability, and connectivity making it easier to combine data and services as desired by users. The technical infrastructure is based on GAIA-X integrated services, which are in turn based on integrated identification and verification mechanisms, sovereign data processing tools, an integrated catalog and compliance system, and certification and accreditation services (). Overall, all of this is expected to create a user-friendly and homogeneous ecosystem of services and data with the aim of creating a system that will facilitate innovation and ensure equal conditions for all (UNCTAD, Citation2020b: 12) within and beyond national borders, EU borders or zones of the EU political influence

Figure 6. Comparison of models of cooperation between companies: current one and new one within the European GAIA-X Ecosystem based on common rules and trust.

2. The joint initiative of the Estonian government and the World Health Organization in 2020 to develop a global technological information platform for the mutual recognition of COVID-19 vaccination certificates, which can serve as a confirmation that it is important not only to revive the economy, but also to build trust in health issues. Thus, there is a great need for a global trust architecture. Such a platform should address the issue of interoperability, deepen the understanding of classifications or taxonomy, and facilitate the will to communicate and find points of trust. Starting from September 2020, this initiative began defining a baseline architecture and pilot a global interoperability project (UNCTAD, 2020: 12).

3. The private South Korean decentralized platform ICON (https://theicon.ist), which intends to create the largest decentralized network not only in Korea, but in the world as well. ICON Foundation is a blockchain protocol very similar to Ethereum and EOS. Its main technological feature is that ICON connects different blockchains using its own, so their ultimate goal is to eliminate barriers between different blockchains and allow them to exchange information without intermediaries through hyperconnection of participants from all over the world. In such an environment, many tasks are performed using smart contracts, and centralized agencies and intermediaries are expected to either become less important or disappear (). At the moment, ICON unites more than one hundred participants that are legal entities. In particular, Korean insurance companies, hospitals, and non-governmental organizations use the ICON structure in their activities exchanging information among themselves in the same industry. In addition, each chain can create its own control system, and the ICON interchain technology will handle all registration requests. Basically, it is a blockchain of blockchains (ICON, Citation2018)

Figure 7. General logic of functioning of the ICON decentralized platform ecosystem using smart contracts.

At this stage, the political risks of using blockchain and blockchain-based products in public governance should be noted.

On the one hand, the blockchain technology has already established itself as a digital technology with enormous transformative potential for society, however, the risks and benefits of its possible application in public relations should be carefully weighed, while utopian expectations as well as the pitfalls of technocratic thinking and determinism should be avoided. Thus, M. Atzori emphasizes that blockchain-based governance should still be regarded as an organizational theory with significant technical and managerial advantages for markets, private services, and communities, but this does not mean that it is a separate political theory. Accordingly, the blockchain technology and decentralized platforms are not hyper-political, but rather pre-political instruments (Atzori, Citation2015, pp. 30–31). If DIP is not balanced with the functions of centralized political institutions (e.g., parliament, courts, the executive vertical of power to a certain extent, etc.), especially in terms of goal-setting and balance of interests, blockchain-based governance can go beyond the concept of moral politics and become immoral governance in the face of globalization and free markets (Marden, Citation2003). These anti-political forces are capable of undermining the main democratic values.

At the same time, one cannot ignore the fact that the weakening of the traditional economic and regulatory functions of the state with the subsequent absorption of its functions by private entities is a really profitable business. Thus, despite the fact that blockchain was originally created to eliminate the need for a third party (agents, providers) in transactions (to reduce transaction costs), the paradox is that the stakeholders currently involved in blockchain management play the classic role of tertius gaudens (Portinaro, Citation1986) (Lat. for “joyful third”), which almost automatically receives economic benefits replacing the state in some of its functions. In addition, these agents can in theory deliberately pursue the “divide and rule” strategy among civil society and the state in order to undermine the traditional democratic order, change the existing balance of power (influence), and their dominance in the society of the future. Robert Dahl (Dahl, Citation1989, p. 47) warned 30 years ago that in the case a state is weak, some actors will always be able to obtain sufficient resources to create a highly repressive state. And if this is so, the neoliberal paradigm of capitalism with its corporate agenda prevailing in the Anglo-Saxon part of the West gradually shaped and globally spread its own version of democracy, which means that it can be fair to assume that now it can begin to be embodied in society using decentralization algorithms.

On the other hand, asserting the idea of the state (both traditional liberal and “paternalistic” (Gorodetskiy et al., Citation2020)) in such a scenario is to confirm the priority of politics over economics and to recognize the need for an authoritative center for coordination in a society where contradictions between individual interests and the common good find a constructive political compromise, and the common social system is not destroyed. In fact, this in no way means defending the current sad transformation of democratic institutions (Claassen, Citation2019, Citation2020; Ross, Citation2001) and civil society into state-corporate systems of mass surveillance of people or justifying the policy of the current government regarding the imposed “security culture”, in which there is a basic attitude towards its citizens as potential criminals. Such de facto undemocratic starting positions of modern society and widespread democracies indicate the need to look in the opposite direction – towards the original values, namely the value of citizenship and the mutual obligations of the state and the individual. That is, “it means to revert to the original spirit of our Constitutions and to their genuine democratic principles … ” (Atzori, Citation2015, p. 31), which are usually perceived by politics as an obstacle.

E. Democracy inside out?

Such a view from the perspective of changes in the functions of the future state and the risk of seizure of control by new elites allows us to see the true motive in the implementation of centralized state platforms and the real format of modern democracy in the “citizen–state” relations, which hardly brings a citizen closer to real governance of his/her state and the public wealth.

Thus, modern democracy in its current widespread form is not the rule of the majority of people, the qualified majority or the practice of collective self-government (Judge, Citation2014; Kartsev, Citation2018; Van Wessel, Citation2009). It has a completely different logic directly formulated by the theorist of modern democracy Joseph Schumpeter almost 100 years ago. He offered to call it democracy when the elites are in charge, and the masses can have influence only by casting their vote for the elites’ representatives (Yudin, Citation2018). That is, the elites are fighting with each other to be elected by the masses, and the masses have no other levers of power. Modern political ratings for assessing the degree of democracy of a political regime proceed precisely from this: are there elections in the first place, how open, fair, and regular are they? That is, elections are becoming the main feature of modern democracy, but this institution is determined not by the power of the people, but by the participation and struggle of elites for power. In such a system of coordinates, democracy will not be the power of the people, but the power of the aristocracy, that is, the power of the best according to people. However, at the same time, these people do not choose the attributes of the best: they are preliminarily determined by party, business or administrative elites and offered to be legitimized during elections. This means that the democratic element has a function of legitimizing this power of the elites. And this is not at all direct democracy or the rule of the people.

For the renewal of the public governance system as a system, this means the following. First, from the point of view of a fuller consideration of the people’s opinion:

public governance system lacks renewal of approaches or even methods of ensuring democracy, for the sake of which allegedly elections are won in countries and the government machinery exists;

elections are gradually becoming a nonbasic form of democratic participation of citizens in the political life of their country, in particular, through the mechanism of representative democracy. Due to the fact that tools and information infrastructure are added to protect trust between participants and their political, property, and other groups of human rights, the mechanism of direct democracy and public accounting, monitoring, and control over public resources is gaining new perspectives owing to a qualitatively new level of accounting in DIP;

protest voting against the very system of formal democratic legitimization is increasingly threatening to governance and public policy. On the one hand, there is people’s loss of interest in politics and elections, that is depoliticization, which threatens the collapse of the democratic legitimization system; on the other hand, there is the growing wave of demands for strengthening democracy expressed in Brexit and the behavior of Donald Trump’s voters in 2020–2021;

in representative democracy, one of the theoretically possible solutions to the problem is transition to the logic of representation as a system of constant real rotation of power, where everyone has a chance to become a representative. Survey democracy as a modern version of representative democracy is not a desirable form of democracy due to the too small coverage of the population in the sample and the absence of any meaningful involvement and interaction of the population before and after a political decision is made (Yudin, Citation2018);

the idea of direct democracy presupposes not an abstract opinion, but will expressed as a result of direct involvement in a conflicting discussion of a common cause – with debates, meetings, demonstrations, self-organization, and collective action.

Secondly, from the point of view of the public governance system structure:

most of the known key elements of a democratic ecosystem () can be improved with the help of DIP due to the provision of greater operational transparency and greater trust between the participants, even without changing the existing models of state (liberal, paternalistic, etc.);

in the case of using a decentralized information platform, the importance of such a management function as accounting is growing rapidly, and, in fact, DIP offers a new model for the implementation of property and personal non-property relations in society using one of the varieties of a virtual asset, namely a digital asset. Digital asset is “an information resource derivative of the right to a value and circulating in the distributed ledger in the form of a unique identifier” (Kud, Citation2019), that is, it circulates in a public and highly secure database (blockchain-based ledger) for the purpose of accounting of property and personal non-property rights of subjects of legal relations;

the institution of citizenship, which is now the main “bridge” between a person and a state with mutual rights and obligations, is acquiring much greater importance. Its perceived and confirmed benefits and prestige for a person will continue to determine (a) what jurisdiction a person chooses to live and pay taxes in, and, accordingly, (b) the strength of the inevitable competition of states for the best talent. This becomes a consequence of the additional protection of the civil rights and citizens’ acquired opportunities owing to the DIP tools.

Thus, since the research focus has shifted towards the “citizen–state” relations due to democratic governance, the DIP phenomenon in combination with blockchain acquire additional and relevant meaning. Without going into techno-utopianism, we believe that this will be an additional argument against the conservative rhetoric of some political scientists and philosophers.

Discussion

Based on all of the above, and especially the structured comparison of the experience of implementing digital platforms in a number of countries, below we will compare different forms of providing public administrative services. As the experiences of Ukraine, the UK, Estonia, and India have shown, it is this sphere of public administrative services that is now the main, target, and demonstrative for the use of information platforms in the public sphere, in particular, state centralized information platforms. The comparison of the three proposed forms (DIP, centralized information platform, and personal reception of citizens) is made more analytical owing to the well-known SLEPT analysis, an analytical tool that takes into account the social, legal, economic, political, and technological parameters of the chosen objects of comparison ().

Table 2. Comparison of decentralized information platforms with other forms of providing public administrative services:SLEPT analysis.

According to , new and fundamentally important is introduction of such parameters differentiating various forms of administrative services as “accounting object”, “property accounting”, “using resources of market forces to provide services”, “form of democracy that can be supported”, “strengthening of social cohesion”, “political independence in implementation”, and “participative governance”. These parameters:

a) make DIP significantly different from other alternative forms;

b) directly link DIP with the solution of the still unresolved problems of democracy;

c) indicate multilateral inclusive public and even global governance, which exists and develops independently of the will of many states, and is a given.

At the same time, it is important to focus on the explanation of several key parameters (according to )

token is a record in the digital data accounting systems based on the distributed ledger technology, which is an identifier of information that can be derived from, in particular, but not as a limitation thereof, an original asset. Blockchain differs from the so-called “classic accounting systems” by its accounting object and technological solution for its implementation. This refers to high-level encrypting, open protocol, distributed information storage, transferring digital data among accounting addresses without intermediaries, which ensures reliable and transparent token transactions (A. Kud, Citation2020);

distributed ledger token is a record in the digital data accounting system, which is an identifier of information that can be, but not exclusively, derived from the original asset (See: On “Tokenized Assets and Crypto-Assets,” Citation2020)Footnote1;

the properties of DIP are directly related and derive from the blockchain technology, however, in their aggregate in the form of DIP, they form a higher level of capabilities compared to blockchain (Kud, Citation2021; A. Kud, Citation2020; see );

the presented political and social parameters are of great importance for the formation of a new vision of the future of a modern country and state. Depending on the desired characteristics of the political model of the future state, they contain both significant risks and opportunities for peoples.

The results of SLEPT analysis according to allow us to determine the characteristics of the three compared forms of providing public administrative services by a much larger number of parameters that can be logically structured according to such three criteria as functionality, security, and cost (see below three tables in : ). These three criteria are typical for evaluating any information system at the stage of its operation. We should note that the efficiency criterion is not taken into account, since among the three compared objects there is one (that is, decentralized information platform) that has not yet been introduced into the public governance system and has no observation history. This does not allow us to assess its effectiveness in any way except by the method of expert forecasting, which is not objective at the moment.

According to the three tables (see ), when decentralized information platforms are introduced into the public governance system, the usual methods of state influence on at least economic, political, and sociohumanitarian relations within the country may change. These methods of state influence will be included in the new mechanism for modernizing the public governance system, but this will not happen soon due to resistance to changes.

As can be seen from the tables in the Appendices (see ), centralized platforms correspond to their purpose: convenience and simplicity of interaction between citizens and the state when receiving public administrative services. This approach fits perfectly into the existing principal–agent paradigm, but does not fit very well into the new paradigm of the network society. Such a society has been spreading throughout the world for a long time. It “attacks” the state functions and displaces the state from its usual positions, in particular, in the monopoly in the sphere of services. For instance, private social networks are important “agents” of a network society, which allow a person to benefit from “horizontal” interaction and create new added value in it, while the state has almost nothing to offer in return. If this practice continues to spread, a great threat to the state will be that social networks do not address their services to a citizen, but rather to a person, sometimes even unidentified. That is, the external network environment weakens the main connection between the person and the state along the line of citizenship. And the person less and less identifies himself/herself with the community of citizens, his/her state and the corresponding political rights and responsibilities. This means that state and public governance must react to this and change from the inside.

Conclusions

1. Decentralized information platforms have significant potential and at the moment can be considered as a very promising tool in modernization of public governance as they ensure the conscious and proactive participation of citizens. In particular, this refers to significant strengthening of the ability and institutional conditions for active participation of citizens in the daily activities of a government body through the development of a new network model of democratic governance using the tools provided by blockchain and the highest level of public confidence in public institutions.