ABSTRACT

Thailand in 2018 became the latest developing country to impose mandatory rules on its fiscal policy that included a national limit on the accumulation of public debt and direct control of local government budgets. Such fiscal recentralization is generally assumed in the literature on multi-level finance to weaken local economic, fiscal, and policy conditions. Yet a newer emphasis in this literature asserts the potential value of central governments in steering and constraining local governments through public finance. Such central steering may strengthen rather than weaken local governments via fiscal, economic, and policy conditions. In this paper, we use the emergent theory of pro-local fiscal recentralization to examine the initial evidence, as well as the emergent opportunities, for local governments in Thailand. We find grounds for optimism that fiscal recentralization will have positive effects, and identify strategies for local governments to optimize those effects. We conclude with recommendations for research and practice on fiscal recentralization in other developing country contexts.

Introduction

In the face of widening budget deficits and global financial uncertainties, Thailand in 2018 became the latest country to impose mandatory rules on its fiscal policy that included a limit on the accumulation of public debt and other measures to recentralize public finance. With an authoritarian government in power and broad social support on this issue, fiscal recentralization is likely to remain a fundamental fact of public finance in Thailand for the foreseeable future.

Rules-based fiscal recentralization differs from standard austerity policies because of its long-term and predictable impact on public finance, in contrast to episodic fiscal recentralization during the business cycle. As elsewhere in the developing world, local governments in Thailand are heavily dependent on the fiscal transfers and revenue-sharing from the central government. As a result, fiscal recentralization through a national debt-brake and other associated budgeting rules affects these governments in multiple ways. It also creates new dynamics of central-local relations. What will be the effects on local governments?

In this article, we outline a framework for examining the effects of fiscal recentralization on local governments, using Thailand as the case study. By “local government” in Thailand we refer mainly to the 7,800 decentralized “local” administrative bodies at the provincial, district, municipal, and sub-district (or tambon) levels rather than to the 8,100 deconcentrated “provincial government” bodies at these levels. Even so, the substantial overlap between the responsibilities, revenue sources, and policy priorities of these two types of locally-based government means that our analysis has implications for latter as well.

We identify three causal pathways – fiscal, macro-economic, and policy-based – through which fiscal recentralization will reshape local government affairs. We then examine both initial evidence and emerging strategies available to local governments in the face of this momentous change. The purpose is to provide a framework for both research and practice that can be applied to other developing country contexts.

Our focus on local government stems from two related concerns. First, as in many decentralized developing countries, local governments in Thailand are the engines of development administration. They are the main conduits of public direct investment, accounting for over half of government spending in this area (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Citation2019b, p. 222). Therefore, the effects of fiscal recentralization on local governments have wide implications for national development as a whole.

Second, the role of local governments in innovation may be particularly pronounced as countries emerge from the COVID crisis because of how the crisis has sometimes weakened national political institutions. The United Nations Development Programme describes the enhanced role of local governments in Latin America as a “positive externality” of the crisis and calls for efforts “to strengthen local governments as the axis of transformation and innovations for effective governance.” (Acuña-Alfaro & Cruz-Osorio, Citation2021) We believe that this logic applies to Thailand as well where local governments have been at the forefront of the COVID response because of their control of public health funds and their knowledge of local conditions, according to the case studies of the municipalities of Rangsit and Chiang Mai by Vongsayan & Nethipo (Vongsayan & Nethipo, Citation2021).

The article begins with a theoretical statement drawn from recent trends in the multi-level finance literature which we label “pro-local fiscal recentralization.” The purpose of the paper is to apply this lens prospectively to the Thai case. As such, our approach is consciously deductive, beginning with a theoretical statement and then examining its validity with respect to emergent (i.e. incomplete) and formative (i.e. process-based rather than outcome-based) data. We examine official documents, local government practices, and budget data in order to evaluate whether this evidence shows a likely positive result from fiscal recentralization consistent with the theory.

The article proceeds in six parts. After introducing the concept of pro-local fiscal recentralization, we provide descriptive information on fiscal recentralization in Thailand since 2018. This is followed by sections on the three causal pathways – fiscal, macro-economic, and policy-based – through which fiscal recentralization is shaping local government affairs. In each case, we consider both probabilistic initial evidence, as well as “possibilistic” opportunities for improved local government performance. We conclude with thoughts on how these dynamics may reshape public finance in Thailand and recommendations for research and practice in other contexts.

Pro-local fiscal recentralization

This article is located within the large literature on multi-level public finance and its effects on fiscal conditions, macroeconomic stability, and policy goals. This literature tends to divide between developed and developing countries because in the latter both governance and decentralization remain uninstitutionalized and thus fiscal relations are subject to significant uncertainty and change. We limit our review mostly to the developing country literature.

Much of the developing country literature on multi-level finance was rooted in the democratization wave of the 1990s and 2000s. It was “decentralizing” and “expansionist” in its orientation, focused on how central governments could provide more funds to local governments, more reliable and equal transfers to different units, and greater local autonomy in fiscal policy, notably in a World Bank report of 2007 (Boadway & Shah, Citation2007). The dominant view was that an institutionalized and expansive decentralization would improve fiscal accountability and the achievement of locally-driven economic and policy goals.

Today, there is a rebalancing of perspectives that asserts the importance of central governments in steering and constraining local governments through public finance, evident in a summative volume of 2018 by Bahl and Bird (Bahl & Bird, Citation2018). This may be to achieve macro-economic stability (a concern missing from the earlier literature) as well as to encourage local revenue mobilization (which has disappointed under fiscal decentralization). There is also a new appreciation of the importance of local governments being aligned with nationally-determined policy goals. This newer balancing of earlier perspectives provides insights into how fiscal recentralization under formal rules such as a debt brake could prove beneficial to local governments alongside more obvious challenges.

To start, local governments can play an important role in contributing to fiscal balance and resulting macro-economic stability through the non-negotiable operation of a debt brake that compels them to support conditions in which they have a self-interest. For example, an Asian Development Bank report of 2002 noted that laws requiring that a fixed proportion of central revenues be given to local governments may have unintended consequences when central governments raise taxes in order to narrow budget deficits. “Since local jurisdictions cannot be expected to have a concern for macroeconomic stability, the additional transfers will be spent, contrary to good macroeconomic policy,” the ADB noted (Schroeder & Smoke, Citation2002, p. 36). Similarly, Bahl and Bird note the challenges of achieving macro-economic stability when local governments have too much spending and revenue autonomy: “Regional and local governments may in various ways make it more difficult for the central government to implement potentially important stabilization policies.” (Bahl & Bird, Citation2018, p. 23)

While in theory, fiscal decentralization could be coupled with local government debt brakes, studies of Germany (Zabler, Citationforthcoming) and Ecuador (Zambrano-Gutiérrez & Avellaneda, Citation2022) show that such brakes are usually not effective given local incentives to overspend and under tax. As a result, balancing budgets for the purposes of macro-economic stability usually requires some degree of fiscal recentralization.

In terms of fiscal revenues, the downside of large and fixed transfers to local governments as advocated by the “localist” literature is that they may undermine local tax efforts, which not surprisingly have remained largely unchanged despite decades of encouragement from the research community. Such transfers, note Bahl and Bird, “may so dwarf the revenue-raising potential of sub-national governments that they are discouraging from making more effort to raise their own taxes.” (Bahl & Bird, Citation2018, p. 319) By locking in declining central transfers, fiscal recentralization creates incentives for local revenue efforts, especially the administrative capacity needed to achieve them. This greater fiscal strength may in turn provide the resources for local economic development. Su and Canh find in a study of 63 provinces in Vietnam from 2006 to 2017 that provinces that boosted their own-income share of their budget tended to attract more investment and to create more positive macroeconomic conditions, both of which raised local productivity (Dinh & Nguyen, Citation2022).

In terms of policy goals, the dominant “benefit model” of the early fiscal decentralization literature argued that policy choices are best left to local governments because they can more precisely target those who benefit in order to raise revenues (or garner votes). This simplistic rational choice model, however, ignored many extenuating factors that may argue for greater fiscal centralization for policy purposes. The Asian Development Bank noted, for instance, that some local governments may be more effective in delivering public services that have spillover effects into nearby regions. In that case, equalization rules on transfers may unduly constrain national policy goals and burden some local governments with policy mandates that should be taken up by neighboring sub-national units (Schroeder & Smoke, Citation2002, pp. 21–23, 46).

Central governments are also better off retaining a steering role where local governments are unable to fulfill central priorities in areas like health, education, and infrastructure. Reviewing several studies, Birner and Braun argue that poverty reduction in developing countries is better done from central ministries because local governments tend to favor the (voting) non-poor in their spending (Birner & Braun, Citation2015). The assumption that those powers should be put under local governments under general grants, observe Bahl and Bird, ignores how “central governments force or induce local governments to act in accordance with national policy objectives”, and these objectives may ultimately be in the local interest (Bahl & Bird, Citation2018, p. 172)

A World Bank paper of 2004 noted that some central governments made transfers contingent on results at the local level while allowing local choices on means (Shah, Citation2004, pp. 10, 15, 31). An emergent idea of “contractual” fiscal relations, where fiscal transfers are made through contracts with local governments, goes a long way to redress the “localist” bias in the earlier literature. In particular, central governments with limited (or debt braked) fiscal resources may contract with the local governments that have the greatest vertical (in carrying out central policy priorities) or horizontal (in delivering public services with benefits to other local governments) effectiveness. This would “lead to greater efficiency and foster political accountability,” writes Spahn (Spahn, Citation2015, p. 149).

A second broad thrust in the literature that redresses the earlier decentralizing approach is an emergent focus on context-specific solutions as opposed to “best practice” that assumes a single best model. “Perhaps the most important lesson one can learn … is that there is no one best way to get it right,” note Bahl and Bird (Bahl & Bird, Citation2018, p. 3). In particular, Asian countries like Thailand have often adopted asymmetric decentralization that variably empowers local governments in different ways despite their equal legal status, including with optional functions (“must do” versus “may do”) and with variously overlapping responsibilities with the central government or its deconcentrated provincial units, according to an OECD survey (Chatry & Vincent, Citation2019, p. 38). This includes not just special rights for major metropolitan areas (in Thailand’s case Bangkok) but a preference for conditional grants over guaranteed transfers. As Bahl and Bird advise on the adoption of flexible funding models for local governments: “Mistakes in designing grants are easier to fix than mistakes in designing constitutions.” (Bahl & Bird, Citation2018, p. 87)

This contextualist approach is important under a non-negotiable debt brake because other fiscal goals like participatory budgeting must take a back seat and are thus subject to contingent implementation. What is important is that this shift in process does not necessarily portend a worsening of outcomes for local governments. Instead, the new fiscal rules may encourage local fiscal capacity-building, macro-economic stability that benefits local economies, and incentives for policy innovation and effectiveness at the local level. For this reason, we refer to this emergent idea in multi-level finance as “pro-local fiscal recentralization.”

Fiscal recentralization in Thailand

Thailand’s public debt, which is almost entirely owned by the central government, hit a then-record high of the equivalent of 58% of GDP in 2000 as a result of the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997–1998 (International Monetary Fund, Citation2022c). Despite many populist spending programs, the prime minister from 2001 to 2006, Thaksin Shinawatra, reduced debt to 39% of GDP by 2006, when he was overthrown in a military coup. This was done through annual “frameworks” put in place from 2002 that set targets to keep debt below 60% (and then 50%) of GDP. Thaksin also initiated performance-based budgeting that reduced the discretionary spending traditionally available to the central bureaucracy, one reason for his unpopularity with the central state as one of the consultants overseeing the Australian-funded fiscal decentralization reforms noted (Dixon, Citation2005) In this sense, fiscal recentralization in Thailand really began with the 2006 overthrow of Thaksin.

In the shadow of the Global Financial Crisis of 2007 to 2009, many developing countries faced a severe loss of investor confidence. In Thailand, fiscal austerity resulting from the crisis led to ad hoc retrenchment by local governments, mainly by deferring capital spending, drawing down reserves, and cutting spending on social welfare, impacting the least advantaged, as shown by Krueathep’s survey of 900 municipal governments (Krueathep, Citation2013).

While the Thaksin governments had reduced public indebtedness, they were perceived by conservatives in Thailand as opening the spending floodgates with fiscal decentralization that would eventually bankrupt the country. The 2011 Local Administrative Organization Revenue Act created a new institution – the Local Administrative Organization Revenue Committee – chaired by the minister of finance to directly control local spending. After Thaksin’s successor party won national elections that year, recentralization came under threat, one reason the military overthrew the government in a second coup of 2014.

In a 2015 book on Thaksin’s “toxic fiscal democracy”, the Chulalongkorn University political science professor (and later military junta member) Charas Suwanmala called for a further institutionalization of fiscal recentralization through a binding debt brake (Suwanmala, Citation2015). The perception was that, given rational expectations among well-informed market participants, a failure by a small open economy like Thailand to reckon with its rising debt might trigger the sort of economic austerity that a debt-brake could forestall.

The military government obliged with two laws in 2018, the Fiscal Responsibility Act and a revised Budget Procedure Act, that followed patterns elsewhere. As two Ministry of Finance economists showed in that year, the shift was motivated by an urgent sense of vulnerability after seeing the effects of the Global Financial Crisis on European countries, especially Greece, and a run of budget deficits in Thailand of 18 out of 21 years since the Asian Financial Crisis. As they wrote, debt fears among investors “could stagger the confidence of the country, giving rise to the emergence of a sovereign and banking crises which require remedial actions from the government … and eventually setting in motion a vicious cycle.” (Asavavallobh et al., Citation2018, p. 124)

The new laws recentralized budgeting powers in many ways. Most important, the laws imposed a 60% of GDP limit on public debt (since raised to 70%), mimicking the 60% limit adopted by the European Union’s 2012 Fiscal Compact rule. Even that was seen as too high by three Thai economists who concluded in 2020 using data from 1998 to 2017 that public debt over 42% of GDP for Thailand would constrain growth. They urged an eventual reduction of the debt limit to 44% to guard against a sudden rise in the costs of rolling over the debt (Tangkanjanapas et al., Citation2020).

While many developing countries have adopted fiscal recentralization in order to control public debt, very few have followed the approach of a legally binding and enforced debt brake. By the end of 2021, Thailand was one of only 22 countries with formal fiscal rules that included a limit on public debt (International Monetary Fund, Citation2022a). Among developing countries, according to the IMF dataset, only Thailand, Vietnam, Botswana, Pakistan, Malaysia, Iran, and Indonesia have debt brakes that are closely followed. It is notable, then, that Southeast Asia accounts for four of seven such cases.

A second major change with fiscal recentralization was to give the central Budget Bureau under the Office of the Prime Minister direct control over local government budget allocations, changing the previous system in which such allocations were made through the Ministry of the Interior. Local governments now coordinate with the provincial offices of the Budget Bureau to develop their plans in coordination with national strategic priorities. Only the deconcentrated provincial governments continue to receive allocations from the Ministry of the Interior, although since 2007 they have also been able to make direct budget requests to the Budget Bureau (Government of Thailand, Citation2020a). A 2022 draft revision of the Local Government Organization Code would allow the Ministry of the Interior to impose direct rule over any local government, a power previously reserved for the deconcentrated provincial governments (Nitikorn, Citation2022).

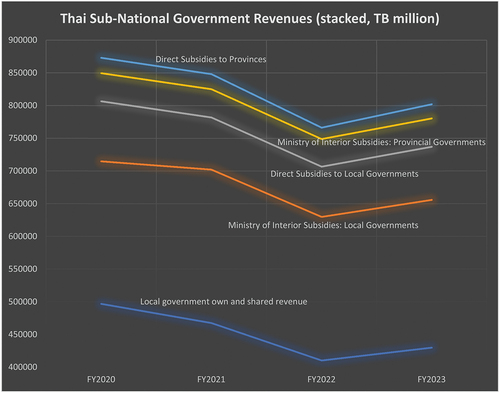

Fiscal recentralization in Thailand took effect just before the global pandemic pushed the country’s finances deeper into trouble. Public debt rose to 58% of GDP in 2021 and is forecast to reach 62% by the end of 2022. This was a result of both falling revenues and of voluntary fiscal expansion (automatic fiscal stabilizers in Thailand are relatively weak; World Bank, Citation2021, p. 24). The expansion was mainly through direct spending by the central government rather than through local governments. Local government revenues fell by 12% between the 2020 and 2022 fiscal years (fiscal years run until end-September) while the revenues of deconcentrated provincial governments fell by 10% (see ) (Government of Thailand, Citation2022f).

The political will behind the debt brake was evident from the 2023 budget cycle. The IMF advocated a nominal 13% increase in budgetary expenditures, bursting the limits of the debt brake (International Monetary Fund, Citation2021, pp. 13, 54). While this would ease the immediate pain of the debt brake, it would also set back the achievement of the macro-economic gains that the brake was supposed to achieve. The Thai government rejected this advice. The budget passed for fiscal year 2023 (ending September 2023) contained only a 4% increase in local government shared revenues and subsidies (and a smaller increase in budgets for deconcentrated provincial governments), both of which represent real declines as inflation was expected to remain above 5% during 2023.

Fiscal effects

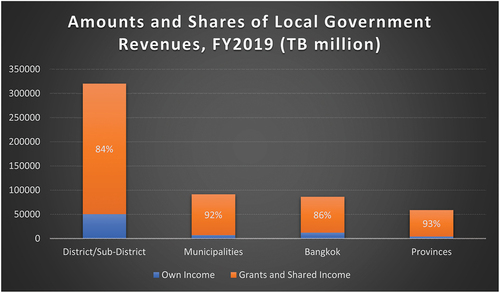

Under conditions of slow or negligible economic growth and continued adherence to the debt brake, declining budgets will be normal for local governments in Thailand for the foreseeable future. This has brought into sharp focus a long-standing and largely unresolved challenge for local governments in developing countries like Thailand: the small proportion of their budgets generated by local taxation and fees. Metasuttirat and Wangkanond note that this problem was identified in Thailand shortly after the country’s decentralizing constitution of 1997, but remained unresolved even with fiscal decentralization (Metasuttirat & Wangkanond, Citation2017, p. 131). In 2010, the proportion of local government revenues from locally-levied taxes and fees was just 6% (Metasuttirat & Wangkanond, Citation2017, Table 1). The figure rose slightly during the 2010s, reaching 15% in 2020 but fell to 9% in 2021 (Government of Thailand, Citation2022d). In FY2019, the last year for which detailed data are available, own-source income accounted for only 16% of district and sub-district (tambon) revenues, 14% of Bangkok revenues, 8% of municipality revenues, and 7% of provincial administration revenues (see ).

As a general rule, local governments in Thailand have highly undeveloped fiscal management systems, whether in budgeting, expenditure, or tax collection, a fact recognized by local officials in a study 272 budget staff in Rayong province carried out in 2014 by Khaikhuea and Budsin (Khaikhuea & Budsin, Citation2015). This is a result of fiscal dependency on transfers and shared revenues from the central state. Thus, one reform with the 2011 Local Administrative Organization Revenue Act was to give local governments scope for revenue raising through new environmental taxes, service fees, and other approved “new taxes.” A Thai parliament report of 2022 urged the central government to remove further barriers to local own-source revenues as a necessary reform to accompany fiscal recentralization. “Regulations should enable local administrations to have more fiscal independence and reduce their reliance on the central government’s budget,” stated a committee report. “The past reliance on central government funding has caused a lack of independence in designing and creating service innovations and in increasing the efficiency of revenue collection and expanding the tax base” (Government of Thailand, Citation2022b, p. 92).

The local property tax in Thailand remains by far the most underdeveloped revenue source. Its full application in Thailand, despite numerous exemptions, would increase local own-taxes by 50% based on Ministry of Finance estimates of losses during its suspension during COVID (Chantanusornsiri, Citation2022). One ADB report estimated that property tax revenues could increase by six times if Thailand achieved OECD levels in this category (Asian Development Bank, Citation2022, p. 23). Yet as Bahl and Bird note, the same things that experts like about the property tax are those that make it challenging for developing countries: its sticker shock visibility to payers, debates on valuations, and the inability of long-time owners to pay as the amount rises (Bahl & Bird, Citation2018, ch. 6). In the five years to 2017, revenues from property taxes in Thailand were on average the equivalent of just 0.23% of GDP, about a third of the already very low level for developing countries as a whole. Over the same period, the average in Indonesia was 0.41% (International Monetary Fund, Citation2022b).

Meesook and colleagues, in a study of six tambon governments in Ayutthaya province in 2016, found that “valuation of land and building tax is very often done arbitrarily” and that tax preferences depend on the whims of tambon government leaders (Meesook et al., Citation2020, p. 210). In his dissertation on private residential property taxes in Bangkok from 2016 to 2019, Maneepitak showed that the municipal government’s reliance on outdated valuations led to spatial unfairness, which reduced revenues due to sub-optimal supply (Maneepitak, Citation2020).

There is evidence that fiscal recentralization has prompted new property revenue efforts. In 2002, property valuation powers were placed under the Ministry of Finance, which created new State Property Appraisal Committees at the deconcentrated provincial government levels. As taxation experts have argued, such valuation and record-keeping “cadasters” in developing countries are best maintained at the provincial or even central level, or by a third-party independent agency, to ensure efficiency and avoid corruption (Ahmad et al., Citation2015, pp. 403–407). The provincial committees barely functioned however since property records came from local governments. Following the post-2006 fiscal recentralization, local governments began to create the property record and administrative systems needed to capture taxes on these valuations. Combined with technical advances in geographic information systems, the provincial appraisal committees in 2020 launch a fully-online valuations database.

Related to this, in 2019, the central government completed a major revision of the property tax – renamed the “land and building tax” – with new higher rates and broader coverage. Despite the immediate suspension of the new law during the COVID pandemic, local governments now have both the incentives and the means to capture revenues once collections restart beginning in the 2023 fiscal year. The government in Nonthaburi municipality, in the northern suburbs of Bangkok, for instance, issued valuation statements in 2020 on major properties within the municipality, averting the “sticker shock” problem identified by Bahl and Bird (Government of Nonthaburi Municipality, Citation2020). In Phuket municipality, the deconcentrated provincial government has taken the lead in capacity building for local tax collection (Government of Thailand, Citation2021a). This initial and process-oriented evidence suggests movement in the right direction, which would end 30 years of inertia on this major local fiscal issue.

Local governments also have control over an array of fees – signage tax, slaughter duty, hotel occupancy fees, and some business registration and retail shop fees. As with property taxes, there is wide scope for local governments to improve collection. Informal labor and business sectors are variously estimated to account for 43% to 54% of Thailand’s non-agricultural workforce (Komin et al., Citation2021) and 39% of GDP (Sotiyanurak, Citation2007). Bringing more labor and business into the formal sector would not only increase fee collections, it would also increase revenues from business and value-added taxes that are shared with the central government.

In 2021, for instance, responding to local revenue shortfalls, the central government updated the 1967 signage tax law. The revision included new categories for digital, LED, and mobile signs, the ending of the exemption for signs from state enterprises, and a large increase in all rates, which were last updated in 1992. This is a potentially significant shift since in the Bangkok municipality, for instance, revenue from the signage tax was 1,050 million baht (about $33 million), or 18% of self-generated revenues in FY2021, before the revision came into effect. Both the amount and the proportion are expected to grow with the broader tax and a continued boom of outdoor advertising (Techasiriprapha, Citation2022).

The other area where fiscal recentralization has encouraged joint efforts to improve local revenues is environmental taxes and service fees. As early as 2010, a Senate report urged the setting of new environmental taxes that could be shared or wholly locally-controlled: “This would give polluters an incentive to reduce their pollution so that their fees are reduced, while at the same time the local government or authorities can use their revenue from fees” (Government of Thailand, Citation2010, p. 160). The nationally-collected excise taxes (only 10% of which go to local governments) on oil products and automobiles have proven inelastic sources of revenue despite income and price effects as well as some temporary suspensions during COVID (Government of Thailand, Citation2022c; Metasuttirat & Wangkanond, Citation2017). A Thailand Development Research Institute report urges that most of these excise revenues be given exclusively to local governments, which would have boosted local revenues by the equivalent of 38% in 2021 (Phitidol, Citation2016).

One new regulation of 2019 allows local government to retain all locally-set motor vehicle fees, road and parking tolls, and fuel levies if they are earmarked for low carbon transport policies. Another significant shift was underway in 2022 to reform the management and sharing of revenues from traffic fines to allow municipal governments a great role and share of the revenues. At present, roughly two thirds of all traffic fine revenues nationally comes from Bangkok, indicative of a major revenue source largely untapped in other municipalities (Government of Thailand, Citation2022g).

Another area where fiscal recentralization has spurred efforts at local revenue mobilization is on the question of local government borrowing. An Asian Development Bank report in 2003 highlighted the undeveloped nature of local government credit markets – bonds and bank loans – throughout Asia despite expanded responsibilities under decentralization (Vera & Kim, Citation2003). Only capital cities like Seoul and Taipei had so far proven credit-worthy borrowers, which freed up central government funds for other local governments. The ADB subsequently wrote a six-volume handbook to help local governments in Thailand access credit markets (Asian Development Bank, Citation2009). But under Thailand’s Public Debt Management Act, local government debt is not guaranteed, which means it is not included in the national debt limit calculation. This makes local government borrowing prohibitively expensive. In addition, since 2011, all local government borrowing has required Ministry of Interior approval.

The combined result is hardly any local borrowing. Provincial and local governments had only 36 billion baht in outstanding debt at February 2022, or just 0.4% of all public debt. This has remained virtually unchanged since 2011 (Government of Thailand, Citation2022e). Attempts by the municipality of Bangkok to issue bonds in the 2010s fell flat (Issarachaiyot, Citation2017). When local governments borrow, it is mostly from the Ministry of Finance or other state banks and financial institutions and debts are rarely rolled over (Sithiyot et al., Citation2015).

As part of the fiscal regime of 2018, new rules permitted local governments to borrow private funds and for some approvals to be done by the deconcentrated provincial governments (Government of Thailand, Citation2020b). A key shift in 2020 was to allow borrowing by the lowest sub-district or tambon governments, of which there are over 5,000. Under the new rules, borrowing can be for three reasons: capital investment, to restructure existing debt, or to raise working capital for pensions or local government-owned pawnshops (of which there are 258 nation-wide). The rules outlined processes for loan approval including measures to measure debt sustainability and to ensure repayment schedules. In 2021, the Ministry of Finance created a dedicated portal and offered training through Ministry of the Interior’s Department of Local Administration so that local governments could report their debt obligations. This resolved a long-standing problem of the random nature of central monitoring of local debt (Kingphuang, Citation2013). Coupled with new local government fiscal sustainability stress tests being carried out under the prime minister’s office (Patamasiriwat et al., Citation2022), this edged the country closer to providing selective guarantees of local government debt, which the Ministry of Finance has had the power to do since 2007.

Thailand’s fiscal recentralization thus has paradoxically seen greater efforts in favor of local fiscal autonomy than under the previous system. Two lessons emerge. One is that while the negative fiscal effects of fiscal recentralization on local governments are fast-moving, the positive effects are slow-moving given the administrative and economic noise associated with boosting local revenues. The second is those positive effects are dependent on central government support, and thus fiscal recentralization works best when coupled with new commitments to local fiscal health.

Macro-economic effects

While direct fiscal effects dominate the literature on multi-level public finance, local government strength is ultimately dependent on the broader political economy in which local government operates. Strong economic and political support may be more important to local governments than fiscal transfers or revenue rights.

As a general rule, fiscal recentralization under a debt brake is introduced in order to protect macroeconomic stability and thus economic growth. Menkulasi’s regression estimates for 17 developing countries before and after the adoption of fiscal rules from 1984 to 2012 show that they enhance growth when the rules protect investment spending from cuts and when the mechanisms of compliance are mainly internal to the government (Menkulasi, Citation2016). Both of these conditions are true in the Thai case. A more recent study of 43 African nations finds robust evidence of the positive role of fiscal rules, including debt brakes, on economic growth (Nabieu et al., Citation2021). The primary mechanism through which debt rules accelerate growth is through lower borrowing costs according to Thorton and Vasilakis’s study of 61 developing countries for 1985 to 2017 (Thornton & Vasilakis, Citation2020).

These findings may be particularly strong in the Thai case because there is some evidence that public spending is relatively inefficient. Suanin, using quarterly data from 1993 to 2014, finds that the growth effects of budgetary spending are only half that of private investment on both physical and human capital, and far less reliable (Suanin, Citation2015, Table 2). Simply restraining government spending, then, may boost growth by releasing funds back into the private sector. Thailand’s relatively rapid recovery from the COVID pandemic shows a macro-economy in robust shape despite the collapse of key industries like tourism.

The second mechanism through which a debt brake may improve local government resources is the extent to which local governments capitalize upon healthy economic growth to develop new private financing options for local development. To date, virtually all formal private financing projects (often called public-private partnerships) in Thailand have been initiated by the central government, led by central agencies, and centered on infrastructure. Local governments “have not been given true freedom in making decisions” to form their own partnerships because “the bureaucratic administration system of the center lacks the clarity and has a complicated chain of authority and management structure that is inconsistent with each local context,” noted Chupradit and colleagues in 2019 (Chupradit et al., Citation2019, p. 481).

We should expect that fiscal recentralization combined with strong macro-economics should encourage more such partnerships, consistent with the findings from Kopańska & Asinski from Poland that local governments with greater fiscal stress are more likely to seek private financing for public services (Kopańska & Asinski, Citation2019). While formal PPPs remain caught in central bureaucratic red tape, local government have created many new informal private finance relationships in response to fiscal recentralization and retrenchment. The northeastern municipality of Roi-Et, for instance, has since 2013 partnered with private investors to help fund its child development and disaster mitigation programs in an example of cross-jurisdiction cooperation that involved four adjacent sub-districts (Sarakarn & Karlers, Citation2018). The municipality of Khon Kaen and four contiguous municipalities, to take another example, have created an arms-length government special purpose vehicle in order to attract private finance for a planned 26-km and 20 station light rail line costing approximately TB17,358 million ($476 million; Laochankham et al., Citationforthcoming). Even more unique, in 2022 the provincial and local governments in Prachinburi province formed a service delivery partnership with the foods and pharmaceuticals giant TCP Group to provide targeted assistance to impoverished households, including renovating their homes (Matichon Online, Citation2022a).

Thailand’s post-2006 fiscal recentralization has been accompanied by broad-based economic growth and local governments have taken advantage of this to strengthen their service delivery. The lesson here is that local governments should identify opportunities emerging from the positive indirect effects of macro-economic stability even as they deal with the immediate direct challenges of fiscal retrenchment.

Policy effects

Multi-level finance is ultimately about the multi-level policy debates that involve the fiscal tool. With few exceptions – such as the local government monopoly over elder care, kindergarten, and firefighting, and the national monopoly on defense, foreign affairs, courts, and policing – all functions in Thailand are not just legally but also practically shared (Laovakul, Citation2019, p. 212). Thus, virtually every policy area involves multi-level policy bargaining.

In Riggs’s seminal study of 1966, Thailand was portrayed as a “bureaucratic polity” dominated by the central bureaucracy and military where elected politicians and even the monarchy were sidelined (Riggs, Citation1966). Beginning with a formal law on decentralization in 1999, Thailand attempted to break this traditional structure by empowering local governments to make their own policy choices. But the twin coups against the democratically-elected Thaksin governments stymied further progress. In 2017, a Regional Development Policy Integration Committee was established to align local development policies with national needs. The committee is chaired by the Prime Minister and comprises representatives from local governments, the private sector, and relevant central ministries.

Coupled with direct control and funding of local government budgets, this policy integration was part of an attempt to introduce more strategic and integrated budgeting practices into Thai public finance, referred to in the 2023 budget as “capacity building of local government organizations to increase mission transfer potential.” (Government of Thailand, Citation2022a, p. 2) This means, for example, that a municipal government with a feasible plan for a bus rapid transit corridor could appeal for a larger budget if such a plan was aligned with Ministry of Transport goals. As a parliamentary report of 2022 put it: “Budgeting in future will require a review of the local government’s drive to lead to the goals according to the national strategy or the master plan under the strategy … The budget allocations of local governments should be distributed based on the nature, prominence, and potential of its national leadership in each area” (Government of Thailand, Citation2022b, p. 97). In the 2022 fiscal year budget, 11% of all spending was allocated to such strategic areas of economic development – a third for transport and logistics and another third for unspecified “competitiveness” enhancements. Fiscal recentralization was thus part of a broader shift to bring local governments into line with the national policy priorities of the resilient “bureaucratic polity” in Thailand.

This has highlighted the challenges for local governments of strengthening their political support by aligning with central priorities without sacrificing their autonomy. The results show both the threats and the opportunities.

In one case, the central government in 2015 launched a multi-sector development plan known as the Eastern Economic Corridor that aims to raise 300 billion baht of private investment per year, a significant leveraging of the total of 82 billion baht of public funds invested in the plan by the end of 2021 (Government of Thailand, Citation2021b). Essentially an attempt to disperse development in Bangkok to the east, the centralized impetus of the project has turned the three relevant local governments at the provincial level – Chachoengsao, Chonburi and Rayong – into little more than branch offices of the central government, according to Klindee’s interviews with provincial officials in Chonburi (Klindee, Citation2020).

On the other hand, a similar project launched in 2022 by the 20 provinces of the northeast known as the “Isan” region calling itself the “Economic Center of the Greater Mekong Sub-region” secured central funding for 410 transport and communications-related projects in the region for FY 2023 worth 10,764 million baht despite being a local rather than central initiative (Matichon Online, Citation2022b). Here, the impetus came from local governments working in cooperation with the deconcentrated provincial governments. The OECD argues that despite its centralizing tendency, the Regional Development Policy Integration Committee also gives local governments an unusual direct voice over national policy priorities (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Citation2019a, ch. 3) and that the committee should be evaluated for possible application to local fiscal issues as well. By doing so, “Thailand’s central government could create political and financial incentives for [local governments] to deliver services in ways that support important national policy goals” (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Citation2019a, ch.3)

Thus while the centralized bureaucratic polity is resilient, it has also created more opportunity structures for local governments to gain authority by slipstreaming with national policy aims. Writing as early as 2016, Unger and Mahakanjana argued that a flexible and responsive bureaucratic polity that ties local governments to national strategic priorities may be “the best option available” in Thailand (Unger & Mahakanjana, Citation2016, p. 186). The addition of the debt brake has thus forced local governments to “sink or swim” in matters of multi-level policy bargaining. If they do not take the initiative and use their direct access to Bangkok, they risk being swamped by centralized authority.

Conclusion

When and how does fiscal recentralization strengthen local government? Our paper suggests several answers to this question by examining fiscal, macro-economic, and policy areas in the case of Thailand. It is clear that these three mechanisms operate in different ways. In the fiscal space, fiscal recentralization strengthens local government when the central level takes a pro-active and supportive approach to strengthening local revenue capacity even as it puts new rules in place to determine and monitor local budgets. In the case of macro-economic effects, the results are more passive: as long as the central government remains committed to regionally broad-based growth, the positive economic effects will be felt by local governments but taking advantage of them require local initiative. Finally, in the case of policy, there is a more competitive, or negotiated, relationship in which local governments are strengthened only to the extent that they can act entrepreneurially to gain policy authority at the expense of rival central (or deconcentrated provincial) authorities.

The Thai case thus suggests then that the “recentralize” turn in the multi-level finance literature may reflect realities on the ground. For that reason, scholars and policy makers should continue to study carefully the phased impacts of cases like Thailand to understand the evolving relationship between fiscal rules and local government performance.

Supplemental Material

Download MP4 Video (148.9 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2022.2111580.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Acuña-Alfaro, J., & Cruz-Osorio, J. (2021). the last bastion of recovery: Innovative and effective governance at the local level. United Nations Development Program: Latin America and the Caribbean Blog(April 13).

- Ahmad, E., Brosio, G., & Poschl, C. (2015). Local property taxation and benefits in developing counties. In E. Ahmad & G. Brosio (Eds.), Handbook of Multilevel Finance (pp. 389–409). Edward Elgar.

- Asavavallobh, N., Aroonvisoot, R., & Yangwiwat, C. (2018). Fiscal sustainability assessment: the case of Thailand. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 5(2), 111–134.

- Asian Development Bank. (2009). Thailand: Commercial Financing for Local Government Units. ADB Publications

- Asian Development Bank. (2022). Strengthening Domestic Resource Mobilization in Southeast Asia.

- Bahl, R., & Bird, R. (2018). Fiscal Decentralizaion and Local Finance in Developing Countries. Edward Elgar.

- Birner, R., & Braun, J. v. (2015). Decentralization and Poverty Reduction. In E. Ahmad & G. Brosio (Eds.), Handbook of Multilevel Finance (pp. 471–505). Edward Elgar.

- Boadway, R., & Shah, A. (2007). Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfers: Principles and Practice. World Bank.

- Chantanusornsiri, W. (2022). Ministry nixes land and building tax cut: Arkhom cites fiscal burden as reason. Bangkok Post

- Chatry, I., & Vincent, R. (2019). A Global View of Sub-National Governments in Asia: Structure and Finance. In J. Kim & S. Dougherty (Eds.), Fiscal Decentralisation and Inclusive Growth in Asia (pp. 27–57). OECD Publishing.

- Chupradit, S., Khanthorn, N., Babad, T., & Chupradit, P. W. (2019). The idea of public-private partnerships to improve the public services of local governments. Suvarnabhumi Institute of Technology Journal, 5(1), 469–483.

- Dinh, S. T., & Nguyen, C. P. (2022). Local government capacity and total factor productivity growth: evidence from an asian emerging economy. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy.

- Dixon, G. (2005). Thailand’s quest for results-focused budgeting. International Journal of Public Administration, 28(3–4), 355–370. https://doi.org/10.1081/PAD-200047345

- Government of Nonthaburi Municipality. (2020). Guide to Payment of Land and Building Tax. https://nakornnont.go.th/files/com_news_private_rule/2020-07_14baaa35f95d665.pdf

- Government of Thailand. (2010). Pollution Tax: New Environmental Control Measures. Senate of Thailand

- Government of Thailand. (2020a). Guidelines for determining the budget allocation framework for the fiscal year 2021 of provinces and provincial groups. Regional Development Policy Integration Committee

- Government of Thailand. (2020b). Regulations of the Ministry of Interior on loans of Subdistrict Administrative Organizations. Ministry of the Interior

- Government of Thailand. (2021a). The collection of land and buildings tax in aranyik municipality and plai chumphon subdistrict municipality.

- Government of Thailand. (2021b). Eastern Economic Corridor News Release, November 11.

- Government of Thailand. (2022a). 2023 Budget in Brief. Office of the Prime Minister, Budget Bureau

- Government of Thailand. (2022b). Analysis of Budget Expenditures for the Fiscal Year 2022: Local Administrative Organizations. Parliament of Thailand, Budget Office

- Government of Thailand. (2022c). Annual Report, Excise Department.

- Government of Thailand. (2022d). Fiscal Policy Office. Ministry of Finance, Fiscal Policy Office

- Government of Thailand. (2022e). Local Government Organizations Debt. Ministry of Finance, Public Debt Management Office

- Government of Thailand. (2022f). Thailand’s Budget in Brief. Office of the Prime Minister, Budget Bureau

- Government of Thailand. (2022g). Traffic fines and traffic management enhancements of the local government organization.

- International Monetary Fund. (2021). Thailand: 2021 Article IV consultation. IMF Country Reports, 21(97).

- International Monetary Fund. (2022a). Fiscal Rules Dataset, 1985 – 2021. IMF Publications

- International Monetary Fund. (2022b). International Financial Statistics. IMF Publications

- International Monetary Fund. (2022c). World Economic Outlook Database. IMF Publications

- Khaikhuea, N., & Budsin, N. (2015). Problems in financial administration of local government organizations in rayong province. Nakhon Phanom University Journal, 5(3), 113–121.

- Kingphuang, P. (2013). The System of Local Government Borrowing: A Case Study of Uttaradit, National Institute of Development Administration.

- Klindee, M. (2020). strategy for the development of chonburi provincial administrative organization to support eastern special development zone. Education Journal, 7(3), 183–196.

- Komin, W., Thepparp, R., Subsing, B., & Engstrom, D. (2021). Covid-19 and its impact on informal sector workers: A case study of thailand. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development, 31(1/2), 80–88.

- Kopańska, A., & Asinski, R. (2019). Fiscal and political determinants of local government involvement in public-private partnership (PPP). Local Government Studies, 45(6), 957–976. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2019.1635016

- Krueathep, W. (2013). Municipal responses to fiscal austerity: The Thai case. International Journal of Public Administration, 36(7), 453–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2013.772631

- Laochankham, S., Gilley, B., & Kamnuansilpa, P. (n.d.). Government special purpose vehicles for public-private partnerships: Stuck on the slow train in Khon Kaen City. International Journal of Public Sector Performance Management. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPSPM.2020.10038755

- Laovakul, D. (2019). Fiscal Decentralisation and Governance in Thailand. In J. Kim & S. Dougherty (Eds.), Fiscal Decentralisation and Inclusive Growth in Asia (pp. 209–234). OECD Publishing.

- Issarachaiyot, S. (2017). Determinants of local bond issuance by bangkok metropolitan administration: Attempt and prospects. King Prajadhipok’s Institute Journal, 15(1), 139–166.

- Maneepitak, D. (2020). The potential economic and social impact of the land and building tax: An evaluation of the property assessment system in Bangkok [Ph.D., University of London, King’s College (United Kingdom)]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

- Matichon Online. (2022a). Ban Sang District shakes hands with the private sector to repair homes and solve poverty problems according to the policy of sufficiency economy. Matichon Online News, April 7.

- Matichon Online. (2022b, February 4). ‘Sak Siam’ discusses the sub-committee of the Isan department of integration development increase the efficiency of communication. Matichon Online

- Meesook, K., Routray, J., & Ahmad, M. (2020). rural local government finance and its management in Thailand: reflections and prospective through tambon administrative organisations. International Journal of Rural Management, 16(2), 199–224.

- Menkulasi, G. (2016). Are Fiscal Rules a Recipe For Growth in Developing Economies?, University of Deleware.

- Metasuttirat, J., & Wangkanond, R. (2017). The development of new revenue structure of local government in Thailand. International Journal of Crime, Law and Social Issues, 4(2), 129–140.

- Nabieu, G. A. A., Bokpin, G. A., Osei, A. K., & Asuming, P. O. (2021). Fiscal rules, fiscal performance and economic growth in sub-saharan Africa. African Development Review, 33(4), 607–619.

- Nitikorn, J. S. (2022). Analyzing the Draft Code of Local Government Organization.

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2019a). Multi-Dimensional Review of Thailand: In-Depth Analysis and Recommendations. OECD Publications

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2019b). Report of the World Observatory on Subnational Government Finance and Investment: Country Profiles. OECD Publications

- Patamasiriwat, D., Ratchataphibulphop, P., Hengpattana, S., Ausuwan, M., & Soisamut, N. (2022). Balance, discipline: Discipline of finance and finance of local Thai. Matichon Online, July1(https://www.matichon.co.th/article/news_3426359).

- Phitidol, T. (2016). Changing the future of Thailand with tax reforms: Proposals from the tax policy community program

- Riggs, F. (1966). Thailand: The Modernisation of a Bureaucratic Polity. Eastwest Center Press.

- Sarakarn, A., & Karlers, S. (2018). The guidelines for creating the local administrative organization best practices on strengthening network government, private and civil society: A case study of Roi-Et Municipality. Journal of Political Science and Public Administration, 9(1), 29–58.

- Schroeder, L., & Smoke, P. (2002). Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfers: Concepts, International Practice, and Policy Issues. In P. Smoke & Y.-H. Kim (Eds.), Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfers in Asia: Current Practice and Challenges for the Future (pp. 20–59). Asian Development Bank.

- Shah, A. (2004). Fiscal decentralization in developing and transition economies. World Bank Policy Research Working Papers(3282).

- Sithiyot, T., Likitragolwong, T., Samrej, P., & Wannasuksai, S. (2015). Local government debt issuance and outstanding: implications for fiscal sustainability. Thammasat Economic Journal, 33(1), 1–15.

- Sotiyanurak, W. (2007). Thailand’s Informal Economy. National Institute of Development Administration

- Spahn, P. B. (2015). Contract Federalism. In E. Ahmad & G. Brosio (Eds.), Handbook of Multilevel Finance (pp. 144–160). Edward Elgar.

- Suanin, W. (2015). Growth-Government spending Nexus: The evidence of Thailand. Bank of Thailand Graduate Essay Contest Award Essays(2015), 1–19.

- Suwanmala, C. (2015). Thailand’s Fiscal Democracy. Chulalongkorn University Press.

- Tangkanjanapas, P., Thamma-Apiroam, R., & Dheera-aumpon, S. (2020). optimal public debt level under fiscal sustainability framework. Chiang Mai University Journal of Economics, 24(2), 38–51.

- Techasiriprapha, N. (2022, 19 April). Bangkok has an income of tens of billions of dollars per year. Where Does It Come From? How Much? Thairath Plus

- Thornton, J., & Vasilakis, C. (2020). Do fiscal rules reduce government borrowing costs in developing countries? International Journal of Finance and Economics, 25(4), 499–510.

- Unger, D., & Mahakanjana, C. (2016). Decentralization in Thailand. Journal of Southeast Asian Economies, 33(2), 172–187.

- Vera, R. d., & Kim, Y.-H. (2003). Local government finance, private resources, and local credit markets in Asia. Asian Development Bank Economics and Research Department Working Papers(46).

- Vongsayan, H., & Nethipo, V. (2021). The roles of Thailand’s City Municipalities in the COVID-19 Crisis. Contemporary Southeast Asia, 43(1), 15–23. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27035519

- World Bank. (2021). Thailand Economic Monitor. World Bank Publications

- Zabler, S. (2021). Uncovering the effect of local government debt brakes in Germany using synthetic controls. Local Government Studies, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2021.1986392

- Zambrano-Gutiérrez, J. C., & Avellaneda, C. N. (2022). Municipal response to fiscal and governance reforms: Effects of stricter debt limits across jurisdictions. International Journal of Public Administration, 45(7), 590–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2020.1868504