ABSTRACT

In line with Pollitt’s call to clarify convergence in public management reforms, this research explores the decisional convergence in the context of performance budgeting reforms. Applying longer, deeper and comparative approaches, this research analyzes decades of experiences and comprehensive performance budgeting written foundations between two countries under the same framework. We found convergence of reform direction and transferability of key dimensions of reform. However, the important decisional divergences lie in evolution paths, reform speeds and the uneven, and sometimes surprisingly differential specifications of measurement, integration, accountability, and culture in performance budgeting foundations between the two countries. Adaptations and aspirations as sources of divergence, theoretical implications of T-form reform, and implications for generally accepted performance principles are explored.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

The use of performance information in budgetary decisions, or performance-informed budgeting (Joyce, Citation2003a), has garnered significant attention in the past 25 years and spread among budgeting systems with varying degrees of sophistication and capacity in different parts of the world, such as the US (Andrews, Citation2004; GAO, Citation1997, Citation2016; Lu & Willoughby, Citation2012). in the OECD countries (Sterck, Citation2007), and in China (Lu & Xue, Citation2011; Ma, Citation2009). The general definition of performance-informed budgeting is the involvement of performance measurement, reporting, management, and the use of performance dialogue in a budgetary setting to boost accountability for results (Ho et al., Citation2019; Labinot, Citation2017; Lu & Willoughby, Citation2012; Moynihan, Citation2008, Citation2015). However, what is increasingly confusing amid the prevalence, and diffusion of performance budgeting is whether government reform initiatives that various countries call performance budgeting mean the same thing, posing significant challenges to both theory building and transferrable knowledge of what works in performance budgeting and budget reforms in general across borders.

One factor that contributes to the ongoing debate on convergence/divergence is how we conduct research. Many studies are done with broad strokes of country-level comparisons. Others may not share the same analytical framework that would allow construction of parsimonious theories. In addition, findings differ based on focuses and stages of reforms under study: research emphasizing basic reform concepts and/or the initial adoption stage of reform tends to arrive at more convergence conclusions, while those focusing on political values, cultures, government structures, and/or the full stages of management reforms tend to depict otherwise (Christensen et al., Citation2008; Jing et al., Citation2015; Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development OECD, Citation2017; Samaratunge et al., Citation2008). Complex budgeting processes across countries, to which performance budgeting is intrinsically linked, further limit clarity on this issue (Grossi et al., Citation2018). These obstacles make cross-country examinations of a complex reform inherently challenging and murky.

This convergence/divergence debate inspires us to explore further whether performance budgeting is a reasonably universally applicable tool among countries. Or, is it dependent upon political, bureaucratic, and managerial contexts? If the truth is somewhere in between, then what parts of performance budgeting are most transferable or most path-dependent on each country’s context?

To address these questions, the challenge this research faces is to unpack the “asterisks” in cross-country comparisons. As Pollitt (Citation2001) pointed out, the principal limitation in cross-country comparison studies is that research shows “tables with asterisks denoting which countries have adopted reform X or Y,” but “it is hard to know exactly what they signify—whether one asterisk is equal to another, and whether the adoption is a brief flirtation or a deep meaningful relationship.” This research addresses this challenge in three ways: drawing from decades of experiences in both countries to look at their respective implementation paths; applying the same analytical framework to analyze their respective legal and policy foundations that orchestrate performance budgeting and exploring the subnational performance budgeting practices beyond the national level. Wide-spread subnational performance budgeting practices often signify maturity of reforms and provide breadth and depth. We further focus our efforts on comparisons between two countries with dramatically different governance structures (Yin, Citation2017): the US and China. The research starts with the introduction of the analytical framework of convergence. We define convergence as both the adoption speeds and the contents of performance budgeting foundations among national and subnational governments. After the discussion of context in each country, we assess convergence based on the same analytical framework to provide insights on whether performance budgeting in both countries converge and in what ways. The article concludes by discussing what the findings mean for understanding international performance budgeting adoptions.

Theoretical framework of performance budgeting convergence and hypotheses

A key step in a convergence study is to define what exactly is compared across units of analysis. One of the best convergence conceptualizations comes from Pollitt (Citation2001). He defined four stages of convergence:

“Discursive convergence – more and more people are talking and writing about the same concepts (performance budgeting, TQM, etc.). The conceptual agenda is converging.” (p. 477)

“Decisional convergence – the authorities (governments, legislatures, boards, and CEOs) publicly decide to adopt a particular organizational form or technique.” (p. 477)

“Practice convergence – public sector organizations begin to work in more similar ways.” (p. 477)

“Results convergence – this is when reforms produce their intended (and unintended effects) so that the outputs and outcomes of public sector activity begin to converge.” (p.478)

This research specifically studies the second stage—decisional convergence. Drawing from the rich data on performance budgeting foundations and a comparative theoretical framework, this research focuses on what the authorities publicly decided to adopt, which fits the second stage of Pollitt’s convergence (also known as decisional convergence) and compares and contrasts varying experiences across two countries. We consider the decisional convergence as a critical step to make organizational reforms official. While other stages of convergence are equally important, they are candidates for further research.

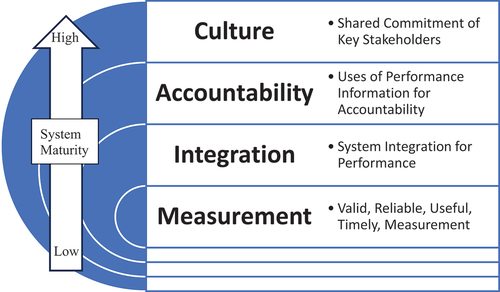

In addition, we go beyond conceptualizing the reform of performance budgeting as a dummy decision (adoption or not). We consider it as a deliberate decision consisting of an overarching design of a performance budgeting system. Drawing from the extensive literature on performance budgeting, depicts a framework of performance budgeting decisions. It identifies four important dimensions of design features that could shape the configuration of a performance budgeting system. The four dimensions are as follows: measurement, integration, accountability, and culture. This framework draws heavily from the work done by Lu and Willoughby (Citation2019), GFOA (Citation2010), Ho et al. (Citation2019) and Moynihan and Beazley (Citation2016).

Figure 1. Theoretical perspectives that influence elements of the framework of performance budgeting.

In line with prior research, we treat these four dimensions as equally important. While going from a foundational dimension of the system (such as measurement) to a more advanced dimension (such as culture) may suggest system maturity, the existing literature seems to suggest that it does not necessarily mean that the mature dimension has more impact. For instance, measurement has been the most cited dimension in US laws across states (Lu & Willoughby, Citation2019), which signifies its importance. Good performance measurement improves the implementation of performance budgeting (Joyce, Citation2003a; Lu et al., Citation2015). In addition, in line with the understanding that performance budgeting is not a stand-alone initiative, its integration with performance-oriented public sector reform (Raudla, Citation2022) is expected. A failed integration of communication, values, and aims among actors and an illusionary analysis of factual possibilities constrain the construction of causalities, hence jeopardizing the successful implementation of the reform of performance budgeting (Mauro et al., Citation2021). In particular, how to integrate budget information into the budget process is always the core issue of performance budgeting (Curristine, Citation2005; Moynihan, Citation2015). Furthermore, accountability lies at the core of performance budgeting that aims to amplify a logical relationship between the input of fiscal budget resources and the result that the resources intend to achieve (De Jong & Ho, Citation2018). Lastly, to effectively achieve the performance targets, it is imperative for the government and its departments to foster an organizational culture that places emphasis on performance throughout all stages of public budget execution, management, and supervision (Moynihan & Beazley, Citation2016). In short, the existing literature suggests that all four dimensions are equally important.

In addition, three theories are particularly instrumental to our theorization of convergence/divergence. The theory of bureaucratic control predicts that organizations, particularly those in formal hierarchical structures, respond to their authorities (Meier et al., Citation2015) and formal rules, the latter of which is regarded as legal papers that direct and coordinate organizational behaviors, which is particularly important in China, known for “governing by decree.” From the path-dependency theory (Pollitt & Geert, Citation2004), we infer those reforms, particularly core institutional reforms such as budget reforms, are bound by traditions and institutional logic, self-reinforcing the existing organizational parameters. In addition, the theory of resource dependency in part explains how resources at the disposal of both countries influence their reform strategies. Drawing from these three theories and in keeping with their dramatically different governing structures, the general hypothesis is that divergence is expected. However, we expect that divergence varies, depending on the dimensions.

First, the presence of valid, reliable, useful, and timely measurement is a foundation of meaningful performance budgeting. Yet, developing proper performance measures is the #1 mentioned difficulty in performance budgeting in the US model (Lu et al., Citation2015). From the bureaucratic control theory, performance budgeting in China serves an important function: legitimizing and strengthening the regime via performance. The political saliency of performance reforms (Jing et al., Citation2015) inevitably translates into tight control over performance measurement design in China’s strict hierarchical government structure. In addition, path dependency indicates that the planning emphasis of Chinese culture promotes and enables strong central guidance. Performance-oriented reforms become a perfect tool that “can serve state building by clarifying capacity demands to incentivize and steer the nascent and incapable public bureaucracy” (Jing et al., Citation2015, p. 51). These two theories predict divergence in terms of the prescriptive nature of the China model. Furthermore, the theory of resource dependency indicates that informational resources are critical and have been readily available due to international knowledge diffusion. Compared to the US, China is late in joining performance budgeting initiatives toward the end of the 1990s after conducting comprehensive reviews of international experience with performance budgeting. Being a rational “shopper,” China was deemed able to quickly draw from the lessons and insights of many countries and adapt performance measurement into its administrative system and budget process (H. M. Wang et al., Citation2020). This may allow China to surpass convergence and reap the advantages of late comers (i.e., having advanced measurement design). As a result, we hypothesize that both countries’ foundations have extensive measurement stipulations, but the Chinese performance measurement is more prescriptive and advanced in measurement than the American system (H1).

Second, the integration component of performance budgeting may have to be more path dependent and bear the imprint of bureaucratic control. At a system level, integration means connecting performance orientations with operations (Lu & Willoughby, Citation2019) and calls for varying degrees of alignment or realignment between performance budgeting practices and institutional norms (Ho et al., Citation2019). Integration of performance budgeting is expected to connect the “dots” between prioritization of strategic goals, budgets, and performance measurements. It also means a layered system of integration where government-wide strategic goals could be aligned with agency strategic goals. In addition, integration requires a significant level of administrative capacity and resources (Moynihan & Beazley, Citation2016). Taken together, it informs us that integration is dependent upon political, strategic, and capacity considerations. We could see less convergence on integration than on measurement. Two recent international comparative research series (Ho et al., Citation2019; Moynihan & Beazley, Citation2016) seem to suggest that countries adapt and vary in performance budgeting integration due to their path dependency. The path that the US took to jumpstart the wave of performance budgeting reforms in 1990s is through the passage of comprehensive performance legislations (Lu et al., Citation2009), signifying government-wide shared interests from both executive and legislative branches. This critical legislative resource in the American model is therefore expected to better enable performance integration with government-wide strategic plans (GAO, Citation1997) and agencies’ measurement and management (Joyce, Citation2011). The Chinese model, however, was first orchestrated by the Ministry of Finance which remains a heavy hand in institutionalizing performance budgeting, resulting in a stronger connection between performance and budgeting. Therefore, we hypothesize that the Chinese model integrates more with budgets but less with government-wide strategic planning than the US model (H2).

Both performance measurement and integration are means to better performance budgeting. A real test is whether and how performance information is used in decision-making and holds governments accountable for performance—the accountability dimension of the performance budgeting framework. Numerous researchers indicate the complexity and importance of accountability mechanisms. Borrowing from the literature (GFOA, Citation2010; Ho et al., Citation2019; Lu & Willoughby, Citation2019), accountability in this context is a tool to address the principle-agent problem in performance outcomes and requires behavioral changes to incorporate performance in decision-making. Given its central control via vast administrative and personnel resources at the top and the path of Chinese characteristics, China deals with the principle-agent problem via tools of incentives and sanctions abundantly available in its administrative and bureaucratic structure to push accountability pressure down while the US may need to invoke more citizen pressure to nudge accountability forward. As a result, we hypothesize that the Chinese model is more likely to specify incentives/sanctions to enforce accountability while the US model emphasizes the role of citizens (H3).

Last but not least is the cultural element. As Rainey (Citation2014, p. 355) summarized, “culture is the pattern of shared meaning in an organization.” In order for the culture to be supportive of performance budgeting, key stakeholders must engage with the process and share responsibilities. One important feature of Chinese politics is its politics-administration relations where the Chinese Communist Party exerts significant control over public affairs. Both the theory of bureaucratic control and path dependency suggest that China’s unified system may lead to skewed participation in favor of the executive branch of the government that wields far more resources and influence as opposed to the legislative branch. In line with path dependence, the link of performance with a government-wide strategic plan remains weak in China. On the other hand, the American model—a politically competitive system that promotes checks-and-balances and appreciates a higher degree of agency autonomy—may have to make shared responsibilities explicit in legislations in order to make performance budgeting a system-wide strategic initiative. In sum, we hypothesize that a wider set of key stakeholders are specified to participate in performance budgeting in the US than in China (H4).

Overall, we expect accountability to exhibit the most divergence, followed by culture, integration, and measurement.

Furthermore, we examined the convergence of vertical reform diffusion, exploring the speed of responsiveness of the state/provincial governments in the US/China to national calls for performance budgeting reforms. Existing studies have explored policy diffusion from the perspective of intergovernmental relations. Research finds that the US government tends to conduct policy-learning from other governments to solve similar problems. This was evidenced by the rapid increase in the number of states adopting performance budgeting in the 1990s (Lu & Willoughby, Citation2019). This policy learning model provided support for strategic planning, performance measurement, and information use in performance budgeting (Kamensky, Citation2018; Lu & Willoughby, Citation2012). However, in China, central administrative policies (including government documents, regulations, plans, opinions, notices, etc.) are an important way to promote the top-down extension of a new reform to subnational governments. Especially in performance budgeting reforms, the central government has a high degree of involvement and influence in the initiation and diffusion of this reform (Zhao & Ho, Citation2019). Given this institutional design, we expect that provincial-level governments in China would respond quickly and intensively to the top-level design of the central performance budgeting (H5), which facilitates “national unification” with the central government at the policy level (He and Du, Citation2021).

Methodology

In order to delineate and compare the specifics of performance budgeting decisions in both countries, we examined the performance budgeting foundations issued by the central and state (US)/provincial (China) governments in each country and their respective evolutions. The US state data was drawn from Lu and Willoughby’s decade-long research that tracks the evolution of US performance budgeting laws. Their extensive research on the laws across 50 states was conducted consecutively in 2008, 2012 and at the end of 2017. According to these authors (Lu & Willoughby, Citation2019, p. 27), as of 2018, “42 states have laws on the books requiring some form of performance measurement application for budgeting.” Their research further content-analyzed the US performance budgeting laws based on 14 dimensions in four groups: integration, incidence, accountability, and comprehensiveness.Footnote1 We regrouped their raw data based on our framework. We are fully aware that it is essential to maintain the consistency in measurement of concepts, particularly in cross-country comparisons.

The Chinese provincial data was independently collected by this research team. We first searched for “performance budget,” “performance budgeting” or “performance evaluation of fiscal expenditure” as key words on websites of government portals and the comprehensive law database of Peking University. We then read through the search results to select performance budgeting foundations. The term “foundations” mean legal foundations or laws in the US setting. In the Chinese setting, the foundations are mostly policy foundation rather than laws with the exception of budget law change in 2014. This reflects how authorities make decisions differently in each country, but they have the same purpose: public announcement of budget reforms. The foundations were formulated by the legislative and administrative branches of both the central and subnational governments. To ensure the integrity and standardization of the samples, we cross-checked these laws, regulations, and policies from different online sources. Then, we invited 40 staff members from 31 provincial-level finance departments to review the policy documents that we gathered to make sure that our collection contains the relevant foundations currently in use. Lastly, the final collection of performance budgeting foundations was read by two researchers. With the initial inter-rater consistency rate at 96.26%, any remaining differences were reconciled. This extensive search process renders one public law and 24 relevant regulations issued by the central government and 219 performance budgeting foundations issued by 31 provincial governments.

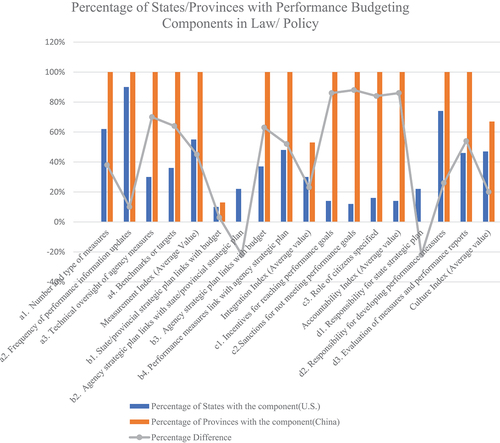

These performance budgeting foundations in both countries were then content-analyzed based on the framework. Specifically, the characteristics of measurement we examined include: number and type of measures, frequency of performance information updates, technical oversight of agency measures and benchmarks/targets. The integration aspect was operationalized via four variables: state/provincial strategic plan links with budget, agency strategic plan links with state/provincial strategic plan, agency strategic plan links with budget, and performance measures link with agency strategic plan (Joyce, Citation2003b). The accountability aspect includes incentives for reaching performance goals, sanctions for not meeting performance goals and role of citizens. Lastly, the cultural aspects include responsibility for state/provincial strategic plan, responsibility for developing performance measures and evaluation of measures and performance reports. summarizes the operationalization of each aspect of the framework. The operationalization process results in a total of 14 variables and each was coded in the same way: 1 if it was specified in the performance budgeting foundation and 0 if not specified. Detailed notes were taken to describe how the foundations lead us to coding it as 1. A total of 42 states in the US with performance budgeting laws and 31 provinces in China with relevant foundations were analyzed through the four elements of the framework, providing a concrete basis for convergence assessment. The differences in the percentages of states/provinces specifying the elements in the framework are used to gauge the general divergence. The bigger the difference, the more divergence. Notes collected during the content analysis were used to tease out the nuances beyond the percentage differences.

In addition, the percentages of states/provinces adopting performance budgeting from 1993–2019 are used to measure the vertical diffusion in respective countries. The year 1993 was chosen because the Government Performance and Results Act was passed in that year which jumpstarted the most recent wave of performance budgeting in the US Finally, before we delve into specific findings, it is important to note that this research only allows us to decipher decisional convergence/divergence (Pollitt, Citation2001). In other words, it is about what has been specified in performance budgeting foundations (decisional convergence). The findings should not be confused with “practice convergence” and/or “outcome convergence,” which are not the focus of this research.

Decisional convergence/divergence?—a tale of two countries

A look at the convergence/divergence of evolutional paths at the national level

The comparison table indicates that the US and China converge on their continued focus on performance budgeting but diverge on their purposes, stakeholder involvement, and implementation strategies over the past 20 years (). Each US president—Clinton (1993–2000), Bush (2001–2008), and Obama (2009–2016)—has reshaped and refined performance budgeting. Under President Clinton, the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) of 1993 launched the recent wave of performance budgeting reform with an emphasis on results-driven strategic planning and performance information supply, with the 1990s representing an explosive era for performance initiatives in the United States (Lu et al., Citation2015). Later, the Bush administration’s Performance Assessment Rating Tool aimed to use performance information to improve budget decisions and project management, which greatly promoted project performance evaluation (GAO, Citation2005; Jones & McCaffery, Citation2010). President Obama’s Management Agenda and Government Performance and Results Modernization Act of 2010 took a step further, creating the position of Chief Performance Officer in charge of coordinating cross-agency program performance. The Evidence Act of 2018 orients the process toward evidence-based decision making in which performance evidence is a key element.

Table 1. Summary of performance budgeting characteristics of the US and China’s national government Initiatives

In China, the central government issued eight important foundations between 2003 (the starting year) and 2018. Over time, the issuers of the foundations increased in importance from the Ministry of Finance (an agency), State Council (executive branch), to the CCP Central Committee (the Party leadership committee). Each step is a new turning point in performance budgeting reform with increasing implications for the entire government (P. Y. Gao, Citation2018; He et al., Citation2019). The perceived significance of performance budgeting was elevated from a performance evaluation tool (2003), an essential element of the revised budget laws (2014), to an inherent requirement to promote the modernization of state capacity (2018). One single important event that gave performance budgeting its legal foundation is the historic move to debut the word “performance” six times in the revised budget laws in 2014.

Decisional convergence on measurement, integration, accountability, and culture at the state/provincial level

As shown in , performance measurement as the first order of business in performance budgeting registers the most frequent mentioning in the legal foundations in both countries (a convergence). summarizes performance budgeting foundations in both countries are more likely to specify the component of measurement (55% of states in the US and 100% of the provinces in China) than other dimensions in the framework. The most striking divergence, however, is that measurement specification is quite similar among Chinese provincial governments, modeling after the central guideline of the national government, while the US state governments vary significantly in the specification. As hypothesized, performance measurements in the Chinese system are specified in incredible details. For instance, the 2011 and 2013 Chinese foundations issued by the Ministry of Finance require provincial governments to specify outcome measures in terms of impact on economy, society, environment, and citizen satisfaction. In addition, many performance measures in China assess the performance of its budgeting system (such as percentage of funding used), not program performance, a finding similar to what was first noted by Lu (Citation2013). This emphasis on the performance of the budget process itself differs from the US orientation toward program performance via budgeting. A closer look reveals that performance measures in China have been generally project-based until recent efforts to make them relevant to standard operations of agencies and consistent from one year to the next. Also, as hypothesized, the Chinese foundations clearly specify advanced measurement features (benchmarking and measurement oversight). However, there is no requirement on the frequency of updates. The standard rule is that performance information is updated and released along with the budget release. Hypothesis #1 that both countries’ foundations have extensive measurement stipulations, but the Chinese performance measurement is more prescriptive and advanced in measurement than the American system is confirmed.

Table 2. States/Provinces with performance budgeting components in Law/Government Guidelines

Figure 2. Divergence in measurement, integration, accountability and culture, measured by the percentage of subnational governments with specified components in each Country.

In terms of integration, the finding confirms our hypothesis that Chinese provincial governments specify much more integration within an agency among the trio of agency strategic plans, its performance measures, and corresponding budgets (b3 and b4-100%) than the US model. The boilerplate languages that integrate the trio in China are that agencies entrusted with the funding shall provide holistic funding arrangements to further an agency’s strategic responsibilities and the development of the respective fields and that governments shall detail performance measurement to cover all funding categories and projects. The Chinese model is muted on how agency strategic plan links externally with province-wide strategic plan (b2 − 0%). This is a distinction shaped by Chinese institutional design: government-wide provincial strategic planning is drafted and released by the Party Committee of a province and not in purview of budgetary offices. However, four economically advanced provinces (Guangdong-GDP ranking 3rd, Zhejiang-4th, Sichuan-6th and Beijing-13th, out of 31 provinces)Footnote2 mentioned their provincial strategic planning in their budget documents (b1), demonstrating some breakaways from the existing path, possibly in part enabled by the resources/capacities that these provinces master. Hypothesis #2 that the Chinese model integrates more with budgets but less with government-wide strategic planning than the US model is confirmed.

In addition, all provincial foundations in China specify incentives for meeting performance goals and sanctions for not meeting them (100%), compared with 14% and 12% of the states, respectively, in the US The most frequently mentioned incentives in Chinese foundations are performance-informed funding priorities and staff promotions, while the most frequent sanctions are the threat of funding withdrawal, auditing, criminal investigation, and demotion. One performance budgeting campaign slogan vividly explains why the accountability in performance budgeting is strong in China: Spending demands performance and non-performance demands accountability. A typical feature of China’s pressure-pumped system is the level-by-level decomposition and distribution of performance tasks and officials’ strong desire for both promotion and blame avoidance (Rong, Citation2013), an important reform measure to achieve self-discipline within administrative departments (Zhao & Ho, Citation2019). Some research indicated that a tournament style of Chinese performance budgeting motivates government officials to compete for goal obtainment (Shang, Citation2018). On the other hand, the US’s foundations seem to be very conscious about the validity of measurement and unintended consequences of a tight performance link with budget (Lu et al., Citation2020). For instance, Louisiana’s foundations require that performance indicators be approved by agency commissioners and allow performance data to be adjusted right before the beginning of the fiscal year to ensure the most accurate expectations of agency performance. Hypothesis #3 (H3) is partially confirmed. The confirmed part of H3 is that the Chinese model is more likely to specify incentives/sanctions to enforce accountability than the US model. The disconfirmed part of H3, also the most surprising finding, is the inclusion of citizen engagement: Chinese foundations uniformly (100%) include an oversight role of citizens in performance evaluation, while a much smaller percentage of their US counterparts (16%) specify the role of citizens in performance budgeting.

Within the cultural dimension, 47% of states have specified shared responsibilities, compared with 67% of provinces in China. The Chinese model does not specify responsibility for state strategic planning (d1) in performance budget foundations. However, both countries converge on specifying responsibility for developing measures (d2). In addition, both the US and China are equally diverse in their specification of shared responsibilities for evaluation of measures and performance reports (d3), describing roles for agencies, budget offices, the legislative branch, and the public with one significant difference: the role of third-party evaluative organizations. Although US foundations occasionally mention the involvement of external professional evaluators, Chinese foundations show a heightened interest in outsourcing performance evaluations to third-party external evaluative personnel, spurred by dedicated funding sources for performance evaluations. This may also be an institutional response to the lack of expertise within governments to take on independent performance assessment. Lu’s research (Lu et al., Citation2015) shed light on the nature of third-party involvement in China, which is dominated by accountants. Yet, its implications for performance culture are far from understood. Hypothesis #4 that a wider set of key stakeholders are specified to participate in performance budgeting in the US than in China is not confirmed because subnational governments in each country specify shared responsibilities, involving similar stakeholders in measurement design but dis-similar stakeholders in strategic planning and evaluation.

Speed of convergence at the state/provincial level

It is recognized that both the US and China started their most recent waves of performance budgeting reform with the involvement of their respective national governments (). The ensuing vertical diffusion speed of performance budgeting foundations across states (in the US)/provinces (in China), however, illustrates the divergence. On one hand, the US’s rate of diffusion is a little less than one state per year during the 25 years between 1993 and 2018 and has not reached all states as of 2020. On the other hand, China has seen a rapid increase in the number of provinces adopting performance budgeting foundations, reaching 100% coverage during the ten years between its initiation year of 2003 and 2014. As hypothesized, China registers a much higher speed of performance budgeting vertical diffusion from national to subnational governments than the US It means that H5 is confirmed.

Discussion and conclusion

Taken together, what do the findings here tell us about international performance budgeting diffusion? The biggest decisional convergence is that all four dimensions of the performance budgeting framework (Measurement, Integration, Accountability, and Culture) are transferrable across countries at the decisional phase. This in part explains the international diffusion of performance budgeting and raises the prospect of generally accepted performance principles, which is currently a vastly under studied topic. Yet the journey, as well as their current state as we unpacked here, shows that beyond the façade of performance budgeting championed in both countries, there are notable divergences. What do these convergence/divergences tell us in terms of building international reform logic and theory?

Logic of divergence: adaptations and aspirations as sources of divergences

This research confirms that some divergences are adaptations. The Chinese model shows the consistency of measurement specification, a strong link with budget but a missing link with state/provincial strategic plans, the predominance of third-party evaluation, and surprisingly the universal mentioning of role of citizens. In line with the theories, these adaptations could stem from the strong bureaucratic control of the Ministry of Finance, dependence on historical path, and the financial and human resource capacity of the central government to keep subnational governments in line. Specifically, the Ministry not only holds the actual power of purse in China but also enjoys a close-knit vertical structure of highly qualified and skilled fiscal officers who are most equipped to be trained and retrained to convey two intertwined messages: control and performance or two birds with one stone. One of the authors of this research happened to be a trainer for local and subnational fiscal officers hired by the Ministry of Finance in China. One thing she witnessed is the power of central guidance in those training sessions, which is a critical factor for the incredible speed in which performance budgeting has rolled out. China aims to legitimize the control over the backbone of its governance system (i.e., budget control) via performance, which is in line with a larger school of its governing philosophy to promote the legitimate governing status via performance in lieu of election. It also makes sense that the design of performance budgeting in China has played up incentives and sanctions because its current political system does so. In contrast, China almost muted the connection of government-wide strategic planning and performance budgeting because the current political system cannot link these effectively yet due to the segmentation of functions.

We also wonder whether time makes a difference to the extent of adaptation. In 2008, Christensen et al. in their article titled “Administrative reform in China’s central government—how much ‘learning from the West’” indicated that “the more specific solutions and models China started to use from the 1980s were very Western and not particularly Chinese” (Lan, Citation2001). Although their observations are not directly on performance budgeting, our research indicates that China today (about 15 years since their article) adapts performance budgeting although the idea comes from the West. These adaptations may stem from the rising confidence of developing countries in their own capacities, institutions, and indigenous cultures as well as the political necessity of maintaining national identity and edge. As Moynihan and Beazley (Citation2016, p. 4) noted, “[t]he countries that appear to have made the greatest progress are those that were willing to adapt rather than abandon performance budgeting.”

However, adaptations are not the only source of divergence—so are aspirations. The universal mentioning of role of citizens by subnational governments reflects both adaptation to the Chinese tradition of following central guidance and some aspirations among subnational governments. On one hand, the Opinions on Comprehensive Implementation of Performance Budgeting, issued by CCP Central Committee and State Council (2018), underscore the role of the public in supervision as one of the fundamental principles and safeguards. For instance, it specifies that ” the financial departments at all levels should actively promote the disclosure of performance information. Important performance targets and evaluation results should be submitted to the corresponding people’s congresses and promptly disclosed to the public, alongside draft budgets and final accounts. This will establish platforms for public participation in performance management, while consciously accepting supervision from both the people’s congresses and citizens.” The Chinese policy foundations seem to suggest that new budget reforms aim to provide to the public the opportunity to participate in budget governance decisions, thus forming a new pattern of grassroots governance (Gu & Han, Citation2014; Lin & Chen, Citation2020). It is a political must for subnational governments to follow central guidelines (adaptation). On the other hand, some degree of citizen engagement is aspired by some subnational government in China. A case in point is John Kamensky’s field study (Kamensky, Citation2018) on Hangzhou’s (the capital city of Zhejiang Province in China) innovative use of citizens’ feedback in governmental decision-making. This citizen engagement approach shows that aspiration could be a powerful incentive to innovate. We do not believe, though, that Hangzhou’s practices are widespread in China. One cautionary note is that this research only examined decisional convergence as reflected in foundations, not practice convergence. In short, both adaptation and aspiration are sources for divergence or surprising findings like the specification of citizen engagement in legal foundations.

T-Form institutional reform and implications for theory building

The near uniformity across provinces alerts us to think deeper on the style of core institutional reform in state-centric frameworks. We observe what we call a “T-form” institutional reform (budget reform) versus an M-form economic reform structure elaborated by Qian and Xu (Citation1993) and Xu (Citation2011). According to Qian and Xu (Citation1993, p. 546), in the M-form structure of Chinese economic reforms, as far as governments at the lower end of the hierarchy are concerned, “[b]oth the weak bargaining power and the semiautonomous position deeply affect the incentives and behavior of local governments.” This feature promotes entrepreneurship, which allows subnational governments to be the engine of economic development. However, this research shows that core institutional reforms take on a completely different shape (T-form) as these institutional reforms carry significant political risk, which deters subnational innovations. The T-form hierarchical structure represents a combination of two strokes: central design from the top and strict vertical implementations among subnational governments with little variance. Although the fast adoption of performance budgeting may indicate a tournament style in implementing central reform mandates (a finding similar to economic reforms), the difference is that subnational governments are not eager to innovate on the content/parameters of core institutional reforms in China. It is about the holistic nature of the core institutional reform in a state-centric framework (Zhou & Xu, Citation2017).

The larger implication pertains to the applicability of western administrative theories to non-western countries, particularly in Asian countries where a state-centric framework is very much alive (Samaratunge et al., Citation2008). As Haque and Turner (Citation2013) pointed out, “although Asian countries may have embraced some ingredients of the NPM and Good Governance models on the basis of imitation or imposition, the basic principles and values of these borrowed models such as efficiency, competition, value for money, capacity, and autonomy may not be compatible with the tradition of centralized one-party rule, bureaucratic dominance, paternalistic norms, and loyalty-based hierarchies in many Asian countries.” The findings in this research further suggest that any study on performance budgeting reforms in state-centric frameworks shall start with the understanding of political preferences and institutional arrangements of a central government. This institutional context determines many adaptations that follow. To some, this contextually driven approach may be a seemingly contrarian suggestion in the globalization of mega trends in public administration. Yet, a study of divergence in a contextually relevant way is what theory-building calls for.

Implications for practice: generally accepted performance principles (GAPPs)?

Is it possible that the convergence of countries is significant enough to form GAPPs? Back in 2008, GASB (Governmental Accounting Standards Board in the US), after more than two decades of research, issued Concepts Statement No. 5, Service Efforts and Accomplishments Reporting, aiming to report key program performance measures across governments in the US and establish the performance equivalent of accounting standards. Then, the Suggested Guidelines for Voluntary Reporting was issued in 2010. Yet, it did not work as hoped. Is the current time ripe for crafting GAPPs? If so, then what would they be? The transferability of the four dimensions of the framework (Measurement, Integration, Accountability, and Culture) indicates that they could serve as a base for crafting , possibly, generally accepted performance principles. We do not see the adaptation discussion or contextualized approaches as the antithesis of GAPPs. Instead, understanding adaptations is key to crafting GAPPs. Knowing what can be transferred and fostering realistic expectations are critical preparations for implementing any reform, particularly core reforms such as budget reforms.

One way to aid the craft of GAPPs and convergence is through reflecting on what can be “borrowed.” Wilson wrote, “We borrowed rice, but we do not eat it with chopsticks” (Citation1992, p. 233). For instance, in our opinion, China can learn from the US about data transparency and shared government-wide performance culture, while the US can learn from China about the role of training in rolling out and furthering performance budgeting by making up the capacity deficits and creating opportunities for collective reflection on reforms. One example of learning and reflection is the 2021 International Marc Holzer Public Performance symposium, where more than 130 participants from 40 plus countries (mainly commonwealth countries) discussed their shared performance missions, challenges and innovations. The prospect of GAPPs warrants further study and exploration in practices.

Overall, this study tells us that the efforts of carefully unpacking the “asterisk,” as Pollitt called it, are not only worthwhile but essential in cross-country comparison studies. Over the past 20 years, both the US and China have gone through an action-packed journey to performance budgeting as embodied by the passage and issuance of the large number of performance budgeting foundations both at the national and subnational levels. This research points to the general framework convergence but with notable adaptations and aspirations as divergences. Given the near universal discursive convergence on performance emphasis, this research shed some light on the extent of decisional convergence. However, a more challenging question is whether practice and results (Pollitt, Citation2001) are more likely to diverge or converge.

Notes

1. For detailed coding description of content analysis, please refer to their book Public Performance Budgeting: Principles and Practice.

2. GDP ranking across provinces in China. Online materials: https://www.sohu.com/a/451368479_166075, released Feb 19, 2021, accessed April 23, 2021.

References

- Andrews, M. (2004). Authority, acceptance, ability and performance-based budgeting reforms. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 17(4), 332–344. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513550410539811

- Christensen, T., Lisheng, D., & Painter, M. (2008). Administrative reform in China’s central government — how much “Learning from the West”? International Review of Administrative Sciences, 74(3), 351–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852308095308

- Curristine, T. (2005). Performance information in the budget process: Results of the OECD 2005 questionnaire. OECD Journal on Budgeting, 5(2), 87–131. https://doi.org/10.1787/budget-v5-art13-en

- De Jong, M., & Ho, A. T.-K. (2018). Lessons about integrating performance with budgeting in high income countries: An evolving exercise. In A. T. Ho, M. de Jong, & Z. Zhao (Eds.), Performance budgeting across countries: Presumed dead or alive and well? (pp. 50–78). Routledge Publishing.

- GAO. (1997). Performance budgeting: Past initiatives offer insights for GPRA implementation No. GAO/AIMD-97-46.

- GAO. (2005). Performance budgeting part focuses attention on program performance, but more can be done to engage congress No. GAO-O6-28.

- GAO. (2016). Managing for results: OMB improved implementation of cross-agency priority goals, but could be more transparent about measuring progress No. GAO-16-509.

- Gao, P. Y. (2018). 40 years of China’s fiscal and taxation reform: Basic track, basic experience and basic rule. China Finance, 26(2), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/cwe.12238

- GFOA. (2010). A performance management framework for state and local government: From measurement and reporting to management and improving. National Performance Management Advisory Commission. https://gfoaorg.cdn.prismic.io/gfoaorg/4ef4e175-b56c-4f92-95cc-606e65ce8ffe_APerformanceManagementFramework.pdf

- Grossi, G., Mauro, S. G., & Vakkuri, J. (2018). Converging and diverging pressures in PBB development: The experiences of Finland and Sweden. Public Management Review, 20(11–12), 1836–1857. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2018.1438500

- Gu, Y. N., & Han, F. G. (2014). Participatory procedures and budgetary identity: A comparative analysis based on the “Yanjin model” and the “Wenling model”. Public Administration Review, 7(5), 35–46.

- Haque, M. S., & Turner, M. (2013). Knowledge-budgeting in Asian public administration: An introductory overview. Public Administration and Development, 33(4), 243–248. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.1664

- He, W. S., & Du, L. N. (2021). How can budget performance information be used effectively? – Comparative analysis based on multiple cases. Chinese Administration, 12(9), 102–109.

- He, W. S., Du, L. N., & Cai, Z. S. (2019). The evolution of the concept of budget governance from the perspective of national governance modernization. Journal of Shanghai Administration Institute, 20(6), 10–21.

- Ho, A. T., Jong, M. D., & Zhao, Z. (2019). Performance budgeting reform theories and international practices. Routledge.

- Jing, Y., Cui, Y., & Li, D. (2015). The politics of performance measurement in China. Policy and Society, 34(1), 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2015.02.001

- Jones, L. R., & McCaffery, J. L. (2010). Performance budgeting in the U.S. federal government: History, status and future implications. Public Finance and Management, 10(3), 482–523.

- Joyce, P. G. (2003a). Linking performance and budgeting: Opportunities in the federal budget process. IBM Center for The Business of Government.

- Joyce, P. G. (2003b). Using performance measures for federal budgeting: Proposals and prospects. Public Budgeting & Finance, 13(4), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-5850.00987

- Joyce, P. G. (2011). The Obama administration and PBB: Building on the legacy of federal performance-informed budgeting? Public Administration Review, 71(3), 356–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02355.x

- Kamensky, J. (2018). A tale of two cities: How different performance management systems use citizen feedback (part 2) | IBM center for the business of government. IBM Center for The Business of Government. http://www.businessofgovernment.org/blog/tale-two-cities-how-different-performance-management-systems-use-citizen-feedback-part-2

- Labinot, D. (2017). What can performance information do to legislators? A budget-decision experiment with legislators. Public Administration Review, 77(3), 366–379. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12713

- Lan, Z. Y. (2001). Understanding China’s administrative reform. Public Administration Quarterly, 24(4), 437–468.

- Lin, M., & Chen, K. (2020). Participation effectiveness of citizen participatory budgeting: The case of Yanjin County in China. Chinese Public Administration Review, 11(1), 6–24. https://doi.org/10.22140/cpar.v11i1.247

- Lu, Y. (2013). Beginning to unlock the black box of the budgetary performance evaluation practices in China: A case study of evaluation reports from Zhejiang Province. Public Money & Management, 33(4), 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2013.799802

- Lu, Y., Mohr, Z., & Ho, A. T. (2015). Taking stock: Assessing and improving performance budgeting theory and practice. Public Performance & Management Review, 38(3), 426–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2015.1006470

- Lu, Y., & Willoughby, K. (2012). Performance budgeting in the states: An assessment. IBM the Business of Government, Fall/Winter, 71–75.

- Lu, Y., & Willoughby, K. (2019). Public performance budgeting: Principles and practice. Routledge.

- Lu, Y., Willoughby, K., & Arnett, S. (2009). Legislating results: Examining the legal foundations of PBB systems in the States. Public Performance & Management Review, 33(2), 266–287.

- Lu, Y., & Xue, C. (2011). The power of purse and budgetary accountability: Experiences from sub-national governments in China. Public Administration and Development, 31(5), 351. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.604

- Lu, Y., Yang, K., & Thomas, M. B. (2020). Designing performance systems in anticipation of unintended consequences: Experiences and lessons from the compstat-based performance regime in NYPD. Administration & Society, 53(6), 907–936. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399720976532

- Ma, J. (2009). ‘If you can’t budget, how can you govern?’—A study of China’s state capacity. Public Administration and Development, 29(1), 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.509

- Mauro, S. G., Cinquini, L., & Pianezzi, D. (2021). New public management between reality and illusion: Analysing the validity of performance - based budgeting. The British Accounting Review, 53(6), 100825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2019.02.007

- Meier, K. J., Favero, N., & Zhu, L. (2015). Performance gaps and managerial decisions: A bayesian theory of managerial action. Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory, 25(4), 1221–1246. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muu054

- Moynihan, D. P. (2008). The dynamics of performance management-constructing information and reform. Georgetown University Press.

- Moynihan, D. P. (2015). Uncovering the circumstances of performance information use findings from an experiment. Public Performance & Management Review, 39(1), 33–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2016.1071160

- Moynihan, D. P., & Beazley, I. (2016). Toward next-generation performance budgeting. World Bank Publications.

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2017). Budgeting and performance in the European Union—A review in the context of EU budget focused on results. OECD. https://www.oecd.org/gov/budgeting/budgeting-and-performance-in-the-eu-oecd-review.pdf

- Pollitt, C. (2001). Clarifying convergence. Striking similarities and durable differences in public management reform. Public Management Review, 4(1), 471–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616670110071847

- Pollitt, C., & Geert, B. (2004). Public management reform: A comparative analysis (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Qian, Y., & Xu, C. (1993). The M-form hierarchy and China’s economic reform. European Economic Review, 37(2–3), 541–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-2921(93)90043-A

- Rainey, H. G. (2014). Understanding and managing public organizations, 5th edition (5th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Raudla, R. (2022). Politicians’Use of performance information in the budget process. Public Money & Management, 19, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2021.1989779

- Rong, J. B. (2013). Review of the research on “Pressure system”. Comparative Economic & Social Systems, 6, 1–3.

- Samaratunge, R., Alam, Q., & Teicher, J. (2008). The new public management reforms in Asia: A comparison of south and southeast Asian countries. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 74(1), 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852307085732

- Shang, H. (2018). The road to government assessment with equal emphasis on motivation and accountability—review and reflection on government performance evaluation in the past 40 years of reform in China. Chinese Public Administration, 8, 85–92.

- Sterck, M. (2007). The impact of performance budgeting on the role of the legislature: A four-country study. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 73(2), 189–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852307077960

- Wang, Z. C. (2018). Budget performance management: The realization path of comprehensive performance management in the new era. Chinese Public Administration, 4, 6–12.

- Wang, H. M., Li, J. P., & Cao, T. Z. (2020). The commonalities and differences between Chinese and western government budget performance management systems: Based on a literature review from 1990 to 2018. Journal of Central University of Finance and Economics, 4, 15–25. https://doi.org/10.19681/j.cnki.jcufe.2020.04.002

- Willoughby, K., & Benson, P. (2011). Program evaluation, performance budgeting and PART: The U.S. Federal government experience. Working paper 11-12. International Studies Program.

- Wilson, W. (1992). “The study of public administration” (originally published in 1887). In J. M. Shafritz & A. C. Hyde (Eds.), Classics of public administration (p. 175). Wadsworth, Inc.

- Xu, C. G. (2011). The fundamental institutions of China’s reforms and development. Journal of Economic Literature, 49(4), 1076–1151. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.49.4.1076

- Yin, R. K. (2017). Case study research: Design and methods. SAGE Publications.

- Zhao, Z. Z., and Ho, T. K. (2019). The new development and enlightenment of performance budgeting theory. Chinese Public Administration, 3, 118–125. https://doi.org/10.19735/j.issn.1006-0863.2019.03.17

- Zheng, F. H., Liao, Y. E., & Lu, Y. F. (2017). Financial performance evaluation: Concept, system and practice. Social Sciences in China, 4, 84–108.

- Zhou, Z. R., & Xu, Y. Q. (2017). Comprehensive understanding of top-level design: An integrated interpretation framework. Administration Forum, 24(4), 118–122.