Abstract

In this article, we are proposing an Identification Key for recognition of Quaternary Spiniferites species and some morphologically close Quaternary taxa of some related genera. We summarize the morphological features of 43 taxa (including three subspecies and one variety) based on the original description of the holotypes and sometimes supplemented by our observations. In addition to the Identification Key, we refer to published illustrations that feature both typical and atypical specimens for each taxon. The compilation of this key gave us the opportunity to reconsider some taxonomic concepts, which resulted in two new combinations and an emendation: Hafniasphaera granulata (Mao Citation1989) comb. nov., emend. and Hafniasphaera multisphaera (Price and Pospelova Citation2014) comb. nov. In addition, we recommend that the names Spiniferites nodosus and Spiniferites pseudofurcatus subsp. obliquus be restricted to their holotype.

1. Introduction

Organic walled dinoflagellate cysts are extremely useful for stratigraphic correlation and for reconstructing palaeoenvironments. For example, they facilitate the determination of hydrological parameters such as sea-surface temperature, salinity, primary productivity, nutrient content, turbidity/stratification of the water column, seasonal sea ice cover and bottom water ventilation (e.g. Dale Citation1976; Wall et al. Citation1977; Turon Citation1984; de Vernal et al. Citation1994; and see Zonneveld et al. Citation2013 for further references). Databases that include the modern geographic distribution of dinoflagellate cyst species are essential for such determinations. During the last four decades, development of such databases has revealed the need for consistency in species identification. Otherwise, the data are compromised. One major difficulty in ensuring consistency in identification of the individual species is that original descriptions are scattered over a large number of publications, which may not be readily available. Furthermore, some descriptions often lack the necessary information for distinguishing species. That explains why we have developed this key to aid identification.

The above concerns are particularly true for species of Spiniferites Mantell Citation1850. Cysts of this genus are common in almost all oceanic and coastal Quaternary sediments. Although the genus is rarely dominant in associations, it can be abundant and show considerable diversity (see de Vernal et al. Citation2018). Species from the Spiniferites complex are generally easily recognized as such by their characteristic spiniferate processes that are trifurcate then sometimes bifurcate. But, most of its species are difficult to distinguish. Differentiation is complicated by the large morphological plasticity of several species that has been shown in modern, in-situ and culture studies (e.g. Lewis et al. Citation1999; Ellegaard et al. Citation2003).

In the key included here, we present a step-by-step guide to the identification of Quaternary Spiniferites complex species when using light microscopy. We consider this ‘complex’ to consist of the genera Spiniferites, Achomosphaera Evitt Citation1963, Hafniasphaera Hansen 1977 and Rottnestia Cookson and Eisenack 1961; see Mertens and Carbonell-Moore (Citation2018) for discussions about these genera. The key does not supersede original or emended species descriptions, but aims to facilitate identification of Spiniferites and Achomosphaera specimens. For this, it uses morphological features that are easy to recognize under light microscopy. Furthermore, it indicates the source of the original and emended descriptions, and the latter have been compiled in Supplementary Descriptions, available with the supplementary online material. This work complements the online determination key initiated by Zonneveld and Pospelova (Citation2015) for the identification of modern dinoflagellate cysts, which can be used to recognize the species of Spiniferites, a prerequisite for the present practical guide. The present key also includes species that are recorded in Quaternary strata but are thought to be extinct. We are assuming that Quaternary cysts have the same morphological characteristics as their holotypes even if the latter are described from older strata. Spiniferites ramosus (Ehrenberg Citation1837b) Mantell Citation1854 is one example, since its type material is Late Cretaceous in age and its stratigraphic range spans ca. 145 Ma (from earliest Cretaceous to the present). Assignment of Quaternary specimens to Spiniferites ramosus is discussed below in taxonomic remarks as well as in Londeix (Citation2018).

The taxonomical resolutions that form the framework of this key are a continuation of discussions held during two workshops in Montreal and Ostend/Ghent respectively in 2014 and 2015 (see Introduction by Mertens et al. (Citation2018)).

2. Prelude to the Identification Key

2.1. Synthesis of original descriptions of Quaternary Spiniferites complex taxa

We consider ‘Quaternary taxa’ as species recorded from the Pleistocene (including the Gelasian) and the Holocene. That totals 43 taxa (Appendix 1), of which three are subspecies (Fensome and Williams, Citation2004) and three varieties: Table S1 (see supplementary online material) summarizes their morphological features. uses the same terms as the original diagnosis or the original description but is sometimes supplemented by observations based on the holotype illustrations or our own observations. To avoid any confusion between these various sources of information, elements from original descriptions are given in quotation marks. With such an approach the vocabulary used in Table S1 is not harmonized, but does conform to the original description.

Table 1. First separation of the Identification Key for Quaternary taxa of the Spiniferites complex.

2.2. Summarized features of Quaternary Spiniferites complex taxa

Morphological characters of dinoflagellate cysts sometimes show close similarities between taxa; thus correct identification can be difficult when based solely on original descriptions and comparisons. In such cases, we relied on our own experience and on the results of round-table discussions during the workshops in Montreal or Ostend/Ghent. Moreover, the light microscope observations made directly on holotypes brought by some participants (e.g. K. Matsuoka, M. Head) helped us to clarify the morphological differences between taxa (see photo stack of holotypes in supplementary material). Our work is also based on interpretations made from studying specimens extracted from type material and published in this special volume (cf. Mertens et al., Ellegaard et al., Gurdebeke et al., Limoges et al., Van Nieuwenhove et al.).

Spiniferites is a taxon whose morphological variability is particularly broad as shown by the number of taxa and morphotypes (e.g. Harland Citation1977; Rochon et al. Citation1999; Mudie et al. Citation2001; Ellegaard Citation2000; Ellegaard et al. Citation2002, Citation2003; Limoges et al. Citation2013). So, during the counting phase of any study, specimens with atypical features or characters not expressed in the original descriptions will be encountered. Other specimens show features of two or more taxa, so identification is dependent on the analyst’s experience.

Most of the taxonomic decisions arising from the Montreal and Ostend/Ghent workshops are discussed in the Round Table Introduction of Mertens et al. (Citation2018). Further discussions are presented below regarding some of the taxa to complete the understanding of taxonomic boundaries and to facilitate the use of the Identification Key. To depict the range of what we consider as standard morphologic features for each taxon, we refer to photographs already published in various works. Further references are provided to illustrated specimens that show less conformity to the morphology of the type material but which we estimate as belonging to the same taxon. In both cases, the photographs are based on Quaternary specimens where possible.

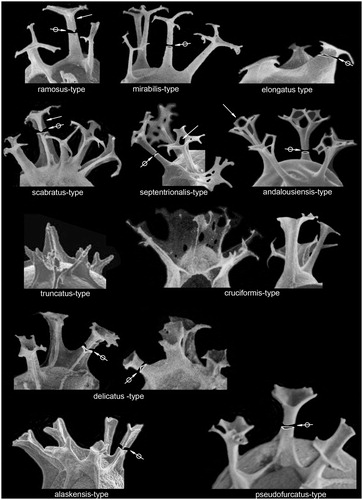

Often original taxonomic descriptions are imprecise or ambiguous or fail to provide enough detail for positive identification. To improve clarity in the key, we have defined some process types (). These morphological criteria refer to standard/dominant gonal processes. The processes of some specimens may have different morphologies depending on their location (adjacent processes having merged bases, apical processes, etc.). This typology is not exhaustive and can be applied independently of the process length, the surface ornamentation, and the wall structure.

Figure 1. Typology of the most common process types occurring in the Quaternary Spiniferites complex. Simple arrows show peculiar features: upward thinning of the stem in ramosus-type processes, relatively constant width of the shaft in scabratus-type processes, fenestration on the trifid platform of septentrionalis-type processes, connection between neighboring bifid tips in andalousiensis-type processes. Rimmed arrows point to a cross section of the stem. Note that in pseudofurcatus-type processes the stem is rounder in cross section and the trifid distal platforms are more developed than in delicatus-type processes; in the latter type, the septa extend along the stems. See text for a more complete description.

alaskensis-type processes (refer to Spiniferites alaskensis Marret et al. Citation2001): elongated processes supported by prominent skeletal rods (formed by the border of the septa continuing up along the process shaft) up to the top of the shaft, giving them a triangular cross section with concave sides; solid shafts; trifurcations characteristically short.

andalousiensis-type processes (refer to Achomosphaera andalousiensis Jan du Chêne Citation1977): processes generally hollow with a circular cross section; closed distally; trifurcations generally well expressed; bifurcations present, with one of the branchlets characteristically connected to that of the neighboring bifurcation; trifurcations make an angle ranging from 100° to 140° with the shaft axis.

bentorii-type processes (not illustrated herein, refer to Spiniferites bentorii (Rossignol Citation1964) Wall and Dale Citation1970)): processes supported by skeletal rods up to the middle or the top of the shaft; triangular cross section with concave sides; base of the shaft relatively wide and particularly curved; shafts mainly solid; trifurcations variable in length, generally V-shaped with an angle from 130° to 140° to the shaft axis; when present, bifurcations are short. See Rossignol (Citation1964, pl.1, fig.3 for illustration of this process type).

cruciformis-type processes (refer to Spiniferites cruciformis Wall and Dale 1973): processes very variable in shape, generally supported by skeletal rods up to the middle or up to the top of the shaft; processes can be lost in the septa when the latter are high; cross section of isolated shafts rather triangular, with concave sides; trifurcations varying in length on a single process; when present, bifurcations are generally faint.

delicatus-type processes (refer to Spiniferites delicatus Reid Citation1974): processes may or may not be supported by prominent skeletal rods (formed by the border of the septa continuing up along the process shaft); when present the rods rise up to the top of the shaft; triangular cross section with more or less concave sides; shafts minutely hollow then solid before the trifurcation; trifurcations often short, lamellar, giving a hexagonal to petaloid shape to the processes ends in plan view.

elongatus-type processes (refer to Spiniferites elongatus Reid Citation1974): stocky processes with a more or less elongated triangular cross section; shafts hollow, distally closed; trifurcations often subparallel to the central body.

mirabilis-type processes (refer to Spiniferites mirabilis (Rossignol Citation1964) Sarjeant Citation1970): elongated processes with a circular cross section, generally minutely hollow and rarely distally open; the gonal processes have relatively long trifurcations, with an angle from 90° to 120° to the shaft axis, generally terminated by short bifurcations; the intergonal processes have relatively long bifurcations, generally terminated by short bifurcations.

pseudofurcatus-type processes (refer to Spiniferites pseudofurcatus (Klumpp Citation1953) Sarjeant Citation1970): elongated processes; triangular cross section with rounded angles; shafts hollow, distally open; trifurcations lamellar, relatively long, giving a petaloid shape to the process ends.

ramosus-type processes (refer to Spiniferites ramosus ramosus (Ehrenberg Citation1837b) Mantell Citation1854): elongated processes; triangular cross section with concave sides; shafts minutely hollow then solid before the trifurcation; trifurcations generally well expressed, with an angle from 90° to 120° to the shaft axis; bifurcations often present, generally short.

scabratus-type processes (refer to Spiniferites scabratus (Wall Citation1967) Sarjeant Citation1970): elongated processes supported by prominent skeletal rods that rise up to the top of the shaft; triangular cross section with deeply concave sides; shafts mainly solid before the trifurcation; trifurcations generally well expressed; bifurcations often present, generally short.

septentrionalis-type processes (refer to Spiniferites septentrionalis Harland Citation1977): elongated processes supported by faint skeletal rods (except around archeopyle where they are prominent); rounded triangular cross section; shafts scarcely hollow then solid before the trifurcation; trifurcations relatively long, lamellar and fenestrated; bifurcations often relatively long; trifurcations make an angle ranging from 90° to 120° with the shaft axis.

truncatus-type processes (refer to Spiniferites bentorii truncatus (Rossignol Citation1964) Lentin and Williams Citation1973): short processes; triangular cross section with concave sides; shafts mainly solid except at the base; trifurcations generally absent; when present, trifurcations are short, with an angle ranging from 120° to 140° to the shaft axis; no bifurcations.

Dorso-antapical processes may be connected by a variably developed septum or flange. To describe the features of such set in a clear and illustrative way we propose the following terms, which apply exclusively to processes present at the angular junctions of plates 4‴ and 1⁗ and the membrane interconnecting them.

we use the term ‘carpet-like’ for adjacent antapical processes connected by a high flange rising up to the first ramification of the processes; processes can be solid or hollow, and are closed distally; the flange is mainly solid. This type of paired processes is often present in Spiniferites membranaceus (Rossignol Citation1964) Sarjeant Citation1970 as depicted in Rossignol (Citation1964, pl.1, fig.4), Reid (Citation1974, pl.3, figs.28–29), Rochon et al. (Citation1999, pl.8, figs.6, 8).

we use the term ‘sirwal-like’ for adjacent antapical processes connected by a very depressed septum rising up to ca. half-height of the process shafts; processes and the connecting membrane can be solid or hollow; the processes can be open or closed distally. This type of paired processes is present in, for example, Spiniferites asperulus Matsuoka Citation1983b or Spiniferites firmus Matsuoka Citation1983b.

we use the term ‘trousers-like’ for adjacent antapical processes connected proximally by a low depressed septum; processes are hollow and distally open. This type of paired processes is present in, for example, Spiniferites pacificus Zhao and Morzadec-Kerfourn Citation1994.

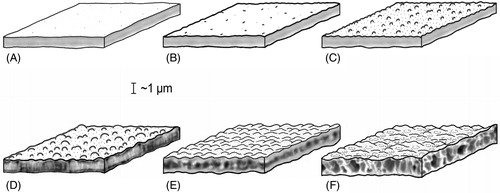

For wall structure, we use ‘simple wall’ when the endophragm and periphragm are appressed, that is without alveolae or lamella (cf. Williams et al. Citation2000). In such a case, the structure (architecture) of the phragms is massive or solid ().

Figure 2. Wall structure and surface in dinoflagellate cysts. (A) Smooth surface, simple structure. (B) Shagreenate surface, simple structure. (C) Microgranulate surface, simple structure. (D) Granulate surface, fibrous structure. (E) Wavy surface, with a bubble-string-like structure. (F) Wavy and foveolate surface, alveolate/vesiculate structure.

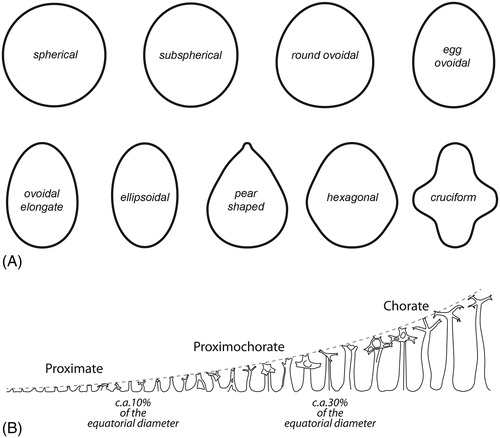

We base our terminology for cyst types on the length of ornamentation relative to the equatorial diameter of the central body (Fensome et al. Citation1996; Williams et al. Citation2000). Thus, in proximate cysts this value is about 10%; in proximochorate cysts it is ca. 10–30%; and in chorate cysts it is more than 30% (). Skolochorate cysts are those with processes alone or a combination of processes and shorter septa or ridges. Murochorate cysts have high sutural septa (cf. Williams et al. Citation2000). The terminology we use for the central body ambitus is shown in .

Figure 3. (A) Schematic illustrations of cyst ambitus shapes. (B) Categorizing of Spiniferites cysts according to their relative processes length.

Spiniferites species originally described with an apical boss are not rare. In contrast, species described as having no apical boss may nonetheless show an apical boss. This plasticity is also observed in genera close to Spiniferites such as Nematosphaeropsis Deflandre and Cookson Citation1955 or Impagidinium Stover and Evitt 1978 (e.g. Turon and Londeix Citation1988, pl.1, fig.5; pl.3, fig.8; pl.6, figs.10–11). When the presence of an apical boss was indicated in the original diagnosis, we have indicated it in the synopsis, but we want to warn the users of the key that this character cannot always be considered as discriminating.

We also do not use the presence of isolated holes on process stalks as a species characteristic. On the other hand we consider wall structure as an important specific criterion, indeed at generic level (i.e. when it is vesicular).

The measurements given are those of type material accompanying the original descriptions. They correspond to the equatorial width and to the length of the central cyst body as observed in optical section. Further information is provided in the R ratio: this is the ratio of the length of the processes (excluding antapical ones) to the equatorial width of the central body of cysts from the type material. When not given by the original description, we have calculated it from the original pictures. When the measurements were made on other specimens, this is also indicated in the text. The user of this key will find the original descriptions of the taxa in the Supplementary Descriptions, available with the supplementary online material.

Spiniferites Mantell Citation1850 emend. Sarjeant Citation1970 can be considered as the defining genus of the spiniferate dinoflagellate cyst genera (see Williams et al. Citation2000). Spiniferate genera occurring in the Quaternary besides Spiniferites are Achomosphaera, Nematosphaeropsis, Rottnestia and now Hafniasphaera. They have in common sutural processes with a simple stem of varying length and with a trifurcation arising at the same height, each branch sometimes being bifurcated. Spiniferites differs from Achomosphaera and Nematosphaeropsis respectively by the presence of septa and the absence of trabeculae. Rottnestia differs from Spiniferites by the presence of wide polar (antapical and sometimes apical) pericoels. Hafniasphaera differs from Spiniferites by its vesicular wall structure.

Achomosphaera andalousiensis Jan du Chêne Citation1977, p.112, pl.1, figs.1–4. Emendation: Jan du Chêne and Londeix Citation1988, p.239. Holotype: Jan du Chêne Citation1977, pl.1, fig.1. Lectotype: Jan du Chêne and Londeix Citation1988, pl.1, figs.1–3.

Synopsis

Skolochorate cyst with subspherical central body, often distorted due to the very thin wall. Simple wall with smooth to shagreenate surface on both central body and processes. Processes often hollow, characterized by their complex distal end: spines of the secondary furcation (bifurcation) characteristically connected to that of the neighboring bifurcation (). No intergonal processes. No septa.

See Figure F1, supplemental online material for photo stack of a topotype.

Dimensions

Central body width 34–44 µm, central body length 40–50 µm, length of processes 14–26 µm (Jan du Chêne and Londeix Citation1988); R = 0.36–0.59.

Comparison

Harland (Citation1983) considered Achomosphaera andalousiensis to be a taxonomic senior synonym of Spiniferites septentrionalis Harland Citation1977. However, Londeix et al. (Citation2009, p.67–68) retained Spiniferites septentrionalis. We also retain Spiniferites septentrionalis based on the following reasons from our own observations (of type and Middle Miocene material):

References to illustrations of typical forms of the species

Optical views: Jan du Chêne (Citation1977, pl.1, figs.1–2, 4; Late Miocene from Southern Spain), Jan du Chêne and Londeix (Citation1988, pl.1, figs.1–9; pl.2, figs.1–9; Late Miocene from Southern Spain), Head (Citation2007, figs.7g–i; Eemian from Baltic Sea); SEM: Jan du Chêne (Citation1977, pl.1, figs.1–2), Jan du Chêne & Londeix (Citation1988, pl.2, figs.10–13; pl.3, figs.1–3), Warny (Citation1999, pl.3, fig.2; Messinian from Southern Spain).

References to illustrations of atypical forms of the species

Optical views: Morzadec-Kerfourn (Citation1979, pl.31, figs.1–2, as ‘Achomosphaera perforata’; Late Pleistocene to Holocene from Western Mediterranean), Londeix et al. (Citation2009, pl.3, fig.9 as Achomosphaera cf. andalousiense; Holocene of Marmara Sea), Shumilovskikh et al. (Citation2013, pl.1, fig.1 as Achomosphaera cf. andalousiense; Holocene of Black Sea); SEM: Morzadec-Kerfourn (Citation1979, pl.35, figs.7–9, as Achomosphaera perforata; Quaternary from Mediterranean Sea).

Achomosphaera callosa Matsuoka Citation1983b, p.128–129, pl.11, figs.6a–c, 7a–b, 8; text-figs.15A–B. Holotype: Matsuoka Citation1983b, pl.11, figs.6a–c; See Figure F2, supplemental online material for photo stack of the holotype.

Synopsis

Skolochorate cyst. Subspherical central body with a thick (ca. 2 µm) simple wall. Surface of the central body coarsely granular, surface of the processes smooth to shagreenate. Ramosus-type processes. No intergonal processes. No septa but sutural ridges can be occasionally present.

Dimensions

Central body width 36–45 µm, central body length 36–53 µm, length of processes up to 15 µm. R = 0.33–0.41.

Comparison

Achomosphaera callosa differs from other Quaternary spiniferate species by its round shape and its moderately thick wall, whose surface is granular on the central body and smooth on the processes.

References to illustrations of typical forms of the species

Optical views: Matsuoka (Citation1983b, pl.11, figs.6–8; Pliocene-Pleistocene from Central Japan).

‘Achomosphaera’ granulata Mao Citation1989: see Hafniasphaera granulata comb. nov., emend.

Achomosphaera ‘perforata’ sensu Morzadec-Kerfourn Citation1979, p.224, pl.31, figs.1–4; pl.35, figs.7–9. Non Achomosphaera ramulifera subsp. perforata (Davey and Williams Citation1966a) Lentin and Williams Citation1973.

Remarks

The informal and invalid new status Achomosphaera ‘perforata’ proposed by Morzadec-Kerfourn (Citation1979, p.224) is herein rejected as well as her synonymy of Achomosphaera ramulifera var. perforata Davey and Williams Citation1966, Achomosphaera andalousiensis Jan du Chêne Citation1977 and Achomosphaera ‘septentrionalis Harland Citation1977’.

Dimensions

Central body diameter 39–42 µm, length of processes 16–18 µm; R = 0.41–0.43.

Comparison

Specimens of Achomosphaera ‘perforata’ sensu Morzadec-Kerfourn Citation1979 show processes whose distal ends are similar to those of Achomosphaera andalousiensis s.s. but the bifurcations are contiguous, and lack distal trabeculae ( shows Achomosphaera andalousiensis). Furthermore, the central body of these specimens appears more ovoidal than in Achomosphaera andalousiensis s.s.

References to illustrations of typical forms of the species

See above for atypical Achomosphaera andalousiensis.

Achomosphaera ramosasimilis (Yun Citation1981, p.14–15, pl.1, figs.1, 8; text-fig.3b) Londeix et al. Citation1999, p.86. Holotype: Yun Citation1981, pl.1, fig.1; text-fig.3b; reillustrated in Fensome et al. (Citation1991, figs.1–2 – p.719, fig.4 – p.721).

Synopsis

Skolochorate cyst with an ovoidal central body. Simple wall, surface smooth to microgranular. Ramosus-type processes, only gonal. No septa but crests can be occasionaly present in the cingular zone.

Dimensions

Central body width 30–32 µm, central body length 36–46 µm, length of processes 16–18 µm; R = 0.50–0.53.

Comparison

Although the type material is Cretaceous in age, we consider Achomosphaera ramosasimilis as a taxon differing from Spiniferites ramosus subsp. ramosus only in the absence of sutures and/or septa. Achomosphaera ramulifera (Deflandre Citation1937b) Evitt Citation1963 differs from Achomosphaera ramosasimilis by its ellipsoidal to rhomboidal central body and its apical and antapical processes that are distinctly different from the others. See also Spiniferites ‘ramuliferus’ sensu Reid Citation1974.

References to illustrations of typical forms of the species

Optical views: Yun (Citation1981, pl.1, figs.1, 8; Cenomanian from Germany), Mudie (Citation1987, pl.2, fig.3, as Achomosphaera ramulifera; Tortonian to Piacenzian from North Atlantic), Londeix et al. (Citation1999, pl.1, fig.1; Zanclean to Piacenzian from Sicily).

References to illustrations of atypical forms of the species

Optical views: maybe Reid (Citation1974, pl.4, figs.39–40, as Spiniferites ramuliferus; Recent from the British Isles).

Cyst of Gonyaulax baltica Ellegaard et al. Citation2002, p.776–782, figs.2J–N, 3A–F, 4G–I, 5. Holotype (motile cell): Ellegaard et al. Citation2002, fig.2A, inadvertently written fig.‘3A’.

Synopsis

Proximate to skolochorate cyst with a spherical to ovoidal central body. Wall simple. Surface smooth to slightly granulate. Processes solid, often hollow at their base, generally ramosus-type whereas shorter processes are often blunt distally. Intergonal processes rare. Septa low, but high septa joining the antapical processes are common.

Dimensions (for cysts of Gonyaulax baltica sensu lato)

Central body width 22–40 µm, central body length 28–45 µm, length of processes very variable, up to 14 µm; R = 0.05–0.42.

Remarks

Cysts of Gonyaulax baltica illustrated with the original description (Ellegaard et al. Citation2002, p.776–782) show a rather wide morphological range. They are not detailed in the synopsis, but are treated separately in the Identification Key. Each morphology refers to specimens depicted by Ellegaard et al. (Citation2002) and is here named Cysts of Gonyaulax baltica ‘K’ for specimens illustrated in figs.2J–N, Cysts of Gonyaulax baltica ‘B’ for specimens illustrated in figs.3A–C and figs.4G–I, Cysts of Gonyaulax baltica ‘E’ for specimens illustrated in fig.3E, Cysts of Gonyaulax baltica ‘F’ for specimens illustrated in fig.3F.

Comparison

Cysts of Gonyaulax baltica are extremely variable. They can resemble Spiniferites belerius Reid Citation1974, Spiniferites membranaceus or Spiniferites mirabilis when antapical processes are connected. However, they differ from Spiniferites mirabilis in lacking numerous intergonal processes and from Spiniferites membranaceus in having shorter antapical processes and a shorter flange. The type material of Spiniferites belerius appears smaller but a specimen referred to that taxon by Harland (Citation1983, pl.44, figs.1–2) looks much like cysts of Gonyaulax baltica ‘B’ (Ellegaard et al. Citation2002, figs.3A–C). Because of the variable morphology with processes and septa being almost absent and an apical boss and enhanced septa sometimes being present, this species is difficult to differentiate. Because of its wide morphological range, cysts of Gonyaulax baltica appears in several places in the key.

References to illustrations of typical forms of the species

Optical views: Ellegaard et al. (Citation2002, figs.4G–I, culture cysts produced at 20 °C/45 psu and 16 °C/33 psu), Head (Citation2007, figs.9a–d; Eemian from Denmark); SEM: Ellegaard et al. (Citation2002, fig.3F, Recent wild specimens; figs.3A–B, culture cysts produced at 20 °C/35 psu).

References to illustrations of atypical forms of the species

SEM: Matthiessen and Brenner (Citation1996, fig.10, as Spiniferites cf. bulloideus; Recent, Greifswald Bay, southern Baltic Sea), Ellegaard et al. (Citation2002, fig.3E, Recent wild specimens; figs.3J–N, culture cysts produced at 16 °C/10 psu, at 20 °C/15 psu, at 16 °C/20 psu and 20 °C/20 psu).

Hafniasphaera granulata (Mao Citation1989) comb. nov., emend. = Achomosphaera granulata Mao Citation1989, p.139, pl.28, figs.9–10 [Mao (Citation1989) gave the citation ‘Achomosphaera granurata sp. nov.’ (p.139) and ‘Achomosphaera granula’a sp. nov.’ (p.194) but ‘Achomosphaera granulata sp. nov.’ (p.216); the latter name has been retained by Fensome et al. (2004), what is done here as well]. Holotype: Mao Citation1989, pl.28, fig.10; reillustrated in Mao and Harland (1993, pl.1, fig.12) and in He et al. (Citation2009, pl.127, fig.14).

Emended description

Proximochorate to skolochorate spiniferate cyst, light brown to brown in color, ovoidal to pear-shaped central body often with a short apical horn (usually 3–5 μm high). A 5–7 µm wide cingulum separates the cyst into two parts of almost the same size. The wall is thick (about 2 µm) and two-layered. The structure of the wall is vesicular on both central body and processes, giving an uneven appearance to the outer surface. The processes are gonal, distally trifurcate, then sometimes slightly bifurcate. Process bases are wide then taper up sharply. The angle between the trifurcations and the process stems is often 90°. Ridges between adjacent processes are generally not developed, however, the paratabulation can be outlined by an alignment of vacuoles, particularly along the cingulum and around the archeopyle. The archeopyle is precingular of type P, formed by the loss of the paraplate 3″.

Discussion

The diagnosis of this species is emended to include reference to its vesicular wall structure of both the central body and the processes. As re-illustrated by Mao and Harland (1983, pl.1, figs.11–12) the type material shows that the granular surface initially described by Mao (Citation1989, p.139), which is at the origin of the species name, corresponds in fact to the optical surface expression of a vesicular wall structure. The holotype (Mao and Harland 1983, pl.1, fig.11) clearly shows partitioned processes and a central body with longitudinal lines in optical section (longitudinal section of vesicles). On the surface of the central body (transversal section) vesicles draw a reticulum.

We consider the species granulata assignable to Hafniasphaera Hansen 1977 because of its thick wall and the vesicular structure of both the central body and processes.

Remarks

Mao (Citation1989) considered her specimens the same as Achomosphaera sp. A of Matsuoka Citation1983b (pl.11, figs.1–5) from the Miocene of central Japan. The processes of the latter taxon have a smooth surface and do not present vesicles (see also Mertens et al. Citation2018, pl.2, figs.4–8). Therefore, the two taxa are distinct and we do not agree with their synonymization.

Synopsis

Proximochorate to skolochorate cyst with an ovoidal to pear-shaped central body. Apical boss often present. Wall thick (ca. 2 µm) and vesicular. Processes vesicular and gonal only. No septa.

Dimensions

Central body width 37–45 µm, central body length 45–53 µm, length of processes 10–13 µm; R = 0.27–0.29.

Comparison

This taxon differs from Hafniasphaera multisphaera (Price and Pospelova Citation2014) comb. nov. by its longer processes.

References to illustrations of typical forms of the species

Optical views: Mao (Citation1989, pl.28, figs.9–10; Quaternary from China), Mao and Harland (1993, pl.1, figs.11–12; same specimen), He et al. (Citation2009, pl.127, figs.13–14; same specimen).

Hafniasphaera multisphaera (Price and Pospelova) comb. nov. = Spiniferites multisphaerus Price and Pospelova Citation2014, p.7–13, fig.3, pl.1, figs.1–13; pl.2, figs.1–12; pl.3, figs7–9; pl.4, figs.4–9; pl.5, figs.4–11. Holotype: Price and Pospelova Citation2014, pl.1, figs.1–13; See Figure F12, supplemental online material for photo stack of the holotype.

Remarks

Because of its thick wall and the vesicular structure of both the central body and the processes, we assign this taxon to Hafniasphaera Hansen 1977.

Synopsis

Proximate to proximochorate cyst. Pear-shaped central body with a pronounced apical protuberance. Wall relatively thick (1.0–2.1 µm) and vesicular. Processes stubby and relatively short and also with a vesicular wall. Paratabulation clearly outlined by sutural alignments of bubble-like elements.

Dimensions

Central body width 36–51 µm, central body length 41–63 µm, length of processes 1.5–8 µm; R = 0.04–0.16.

Comparison

Hafniasphaera granulata comb. nov. and Spiniferites bentorii also possess a pear-shaped central body. The former differs from Hafniasphaera multisphaera comb. nov. by its longer processes and the latter by its simple wall structure. Hafniasphaera multisphaera comb. nov. differs from species of Spiniferites and Achomosphaera in having both a pear-shaped central body and a relatively thick and vesicular cyst wall.

References to illustrations of typical forms of the species

Optical views: Price and Pospelova (Citation2014, pl.1, figs.1–13; pl.2, figs.1–12; pl.3, figs.7–13; late Quaternary, Guaymas Basin, Gulf of California); SEM: Price and Pospelova (Citation2014, pl.4, figs.4–11; pl.5, figs.4–9).

‘Rottnestia amphicavata’ Dobell and Norris in Harland et al. Citation1980, p.218–220, figs.4A-N, 5–7. Holotype: Harland et al. Citation1980, text-figs.4A–C.

Remarks

Bujak (1984, p.191) considered ‘Spiniferites frigidus’ to be a taxonomic senior synonym of this species, however de Vernal et al. (1992, p.324) retained Rottnestia amphicavata. Van Nieuwenhove et al. (Citation2018) recommend treating Rottnestia amphicavata as a taxonomic junior synonym of Spiniferites elongatus.

Synopsis

Chorate to murochorate cyst with an ellipsoidal central body whose surface is smooth to microgranulate. Surface of processes smooth to shagreenate. Processes gonal only, membranous, of elongatus-type. Antapical processes higher than the others, characterized by two wide conical cavations extending from their bases up to almost their ends, or sometimes distally open. An apical process is also distinguished by a conical pericoel. Sutural septa well developed particularly at the antapex where the boundaries of plate 1⁗ are suturocavate.

Dimensions

Central body width 32–42 µm, central body length 50–68 µm, length of processes 13–16 µm; R = 0.38–0.41.

Remarks

When erecting this species, Dobell & Norris depicted two varieties we can consider as the extremes of the morphological range of this taxon.

Variety B is distinguished by having an antapical pericoel encompassing the plate 1⁗ as found in species of the genus Rottnestia.

Variety C differs from other morphotypes of the taxon in lacking well-developed sutural crests and gonal processes.

Each of these varieties is considered separately in the Identification Key.

Comparison

Although similar, Spiniferites elongatus and ‘Spiniferites frigidus’ differ from ‘Rottnestia amphicavata’ in lacking conical cavations.

References to illustrations of typical forms of the species

Optical views: Harland et al. (Citation1980, figs.4A–N, 5, 7; Holocene, Canadian Arctic), de Vernal et al. (1992, pl.5, fig.7; Quaternary, Labrador Sea), Rochon et al. (Citation1999, pl.7, figs.1–4; late Quaternary, North Atlantic Ocean), Radi et al. (Citation2001, fig.4, fig.7, as Spiniferites intergrade elongatus-frigidus; Recent, Bering Sea and Chukchi Sea), Radi et al. (Citation2001, fig.4, figs.8, 9, as Spiniferites frigidus), Ribeiro et al. (Citation2012, fig.3G; Holocene, Disko Bay, West Greenland), Heikkilä et al. (Citation2014, pl.1, fig.8, as Spiniferites elongatus s.l.; Recent, Hudson Bay); drawing: Harland et al. (Citation1980, figs.6, 9); SEM: Ellegaard et al. (Citation2003, figs.27, 30, as Gonyaulax elongata cyst; Recent).

References to illustrations of atypical forms of the species

Optical views: Harland et al. (Citation1980, figs.4O–P, 8), Ribeiro et al. (Citation2012, fig.3H; Holocene, Disko Bay, West Greenland); SEM: Harland et al. (Citation1980, fig.6), Ellegaard et al. (Citation2003, fig.30, as Gonyaulax elongata cyst).

Spiniferites alaskensis Marret et al. Citation2001, p.384–386, pl.1, figs.1–9 ex Marret in Fensome and Williams Citation2004, p.613. Holotype: Marret et al. Citation2001, pl.1, figs.7–9.

Synopsis

Skolochorate cyst with an ovoidal central body. Presence of a short apical boss. Wall thin with a finely scabrate to microgranulate surface. Paratabulation is well expressed by low septa. Processes solid, relatively long, robust, with a much-shortened distal trifurcation. Generally no bifid tips. Trifurcations make an angle ranging from 100° to 140° with the shaft axis. No intergonal processes.

See Figure F3, supplemental online material for photo stack of a topotype.

Dimensions

Central body width 23–32 µm, central body length 26–37 µm, length of processes 7.5–12.5 µm; R = 0.32–0.40.

Comparison

Spiniferites alaskensis differs from other species of Spiniferites by its peculiar processes, which are straight with a short distal trifurcation.

References to illustrations of typical forms of the species

Optical views: Marret et al. (Citation2001, pl.1, figs.4–6, 7–9; late Quaternary, Gulf of Alaska), Marret and Mertens (Citation2018, pl.1, figs.1–6; pl.2, figs.3–4; late Quaternary, Gulf of Alaska); SEM: Marret et al. (Citation2001, pl.1, figs.1–3), Marret & Mertens (op. cit., pl.1, figs.7–10; pl.2, figs.1–2, 5–6).

Spiniferites asperulus Matsuoka Citation1983b, p.131–132, pl.12, figs.2, 3a–b, 4; text-figs.17A–B. Holotype: Matsuoka Citation1983b, pl.12, fig.2; See Figure F4, supplemental online material for photo stack of the holotype.

Synopsis

Proximochorate to skolochorate cyst with a spherical to subspherical central body. Moderately thick wall (ca. 1.7 µm). Surface slightly granular on the central body and shagreenate to scabrate on the processes. Paratabulation more or less highlighted by very low granular ridges. Intergonal (bifurcate) processes occasionally present. Broad and membranaceous ‘sirwal-like’ pair of dorso-antapical processes.

Dimensions

Central body width 45–64 µm, central body length 48–69 µm, length of processes up to 16 µm; R = 0.25–0.33.

Comparison

The holotype of Spiniferites asperulus develops a ‘sirwal-like’ pair of wide and membranous antapical processes that are very like the equivalent processes in Spiniferites membranaceus and Spiniferites firmus. However, Spiniferites asperulus differs from Spiniferites membranaceus in having a microgranular surface body and processes. Spiniferites firmus differs from Spiniferites asperulus in having processes which are stout, hollow and smooth on the outer surface.

References to illustrations of typical forms of the species

Optical views: Matsuoka (Citation1983b, pl.12, figs.2, 3a–b, 4; Upper Miocene to Pliocene from Central Japan).

References to illustrations of atypical forms of the species

Optical views: Matsuoka (Citation1985, pl.4, figs.7–8; Recent from Nagasaki Bay).

Spiniferites belerius Reid Citation1974, p.596–598, pl.2, figs.12–13. Holotype: Reid Citation1974, pl.2, figs.12–13.

Synopsis

Proximochorate cyst with an ovoidal central body and an apical boss. Wall thin and smooth to very finely granular. Processes gonal only, however occasional intergonal processes can be present (Limoges et al. Citation2018). Paratabulation expressed by low clear septa that sometimes form crests. High antapical ‘trumpet’ shaped processes.

Dimensions

Central body width 28–37 µm, central body length 35–42 µm, length of processes 7–10 µm; R = 0.25–0.27.

Comparison

The characteristics that define Spiniferites belerius are: the relatively small body size (see above) and ovoid shape (with a relatively wide antapex), and short processes that are not well formed apically and variably membranous at the antapex. Spiniferites belerius resembles Spiniferites mirabilis in having an antapical protusion but Spiniferites mirabilis has numerous intergonal processes; it differs from Spiniferites membranaceus in having a trumpet shaped process rather than a ‘carpet-like’ flange antapically.

References to illustrations of typical forms of the species

Optical views: Reid (Citation1974, pl.2, figs.12–13; Recent from British Isles), Harland (Citation1977, pl.2, figs.7–10; late Quaternary from British Isles), Matsuoka (Citation1987a, pl.3, figs.7–8, as Spiniferites sp. cf. S. delicatus; Recent from North Japan), Turon and Londeix (Citation1988, pl.1, figs.13–15; late Quaternary from Alboran Sea), Marret et al. (Citation2009, pl.1, fig.14; Holocene from Black Sea).

References to illustrations of ‘atypical’ forms of the species

Optical views: Harland (Citation1977, pl.2, figs.25–27), Harland (Citation1983, pl.44, figs.1–2; Recent from North Atlantic), Rochon et al. (Citation1999, pl.6, figs.1–2; late Quaternary from North Atlantic), Londeix et al. (Citation2009, pl.2, fig.11; late Quaternary from Marmara Sea), Limoges et al. (Citation2013, pl.2, fig.12; Recent from Gulf of Mexico).

Spiniferites bentorii (Rossignol Citation1964, p.84–85, pl.1, figs.3, 3bis, 5–8; pl.3, figs.1–3; text-figs.A–F) Wall and Dale Citation1970, p.47–48.

- subsp. bentorii. Autonym. Holotype: Rossignol Citation1964, pl.1, figs.3, 7–8.

Synopsis

Skolochorate cyst characteristically pear-shaped, with a pronounced apical protuberance. Epicyst longer than the hypocyst which is typically hemispherical. Central body wall surface shagreenate to scabrate, rarely microgranular. Processes mainly solid, slender and delicate with a relatively wide and particularly curved base. Process trifucartions of Spiniferites bentorii bentorii are often V-shaped, generally with an angle from 130° to 140° to the shaft axis. This regular characteristic was not mentioned by Rossignol in the original description (1964, p. 84–85), but it is clearly depicted in her drawing (op. cit., pl.1, fig.3). Intergonal processes are occasionally present. Paratabulation is expressed by low parasutural septa.

See Figure F5, supplemental online material for photo stack of a characteristic specimen.

Dimensions

Central body width 45–63 µm, central body length 60–73 µm, length of processes 15–20 µm; R = 0.32–0.33.

Comparison

The large, pear-shaped central body and the concave process stems with V-shaped trifurcations are characteristic of this species. It differs from Hafniasphaera multisphaera comb. nov. by its simple wall, which is vesicular in the latter species.

Remarks

The cysts illustrated by Wall (Citation1965, figs.24–29), Wall and Dale (Citation1970, pl.1, figs.26, 28), and Pospelova et al. (Citation2005, fig.4, nos.2–3) as Spiniferites bentorii bear at least two intergonal processes between two gonal processes, and despite the presence of an apical boss are very close to Spiniferites hyperacanthus (Deflandre and Cookson Citation1955) Cookson and Eisenack Citation1974. Therefore, we prefer to consider them as questionably belonging to Spiniferites bentorii or to follow McMinn (Citation1991, pl.2, figs.15–16) who included them in Spiniferites hyperacanthus.

References to illustrations of typical forms of the species

Optical views: Rossignol (Citation1964, pl.1, figs.3, 3bis, 5–8; pl.3, figs.1–3; Quaternary from Israel), Wall (Citation1965, fig.3; Recent from Woods Hole region), Harland (Citation1978, pl.3, fig.5; late Quaternary from NW European continental shelf); Turon and Londeix (Citation1988, pl.3, fig.1; late Quaternary from Alboran Sea), de Vernal et al. (1992, pl.5, fig.10; late Quaternary from North Atlantic), Morzadec-Kerfourn (Citation2002, pl.1, fig.7; late Quaternary from Central Mediterranean), Mudie et al. (Citation2010, fig.3.20; late Quaternary from Black Sea), Pospelova and Kim (Citation2010, pl.1, fig.F; Recent from southern South Korea), Shumilovskikh et al. (Citation2013, pl.1, fig.12; Recent from Black Sea); SEM: Turon and Londeix (Citation1988, pl.7, fig.2).

References to illustrations of atypical forms of the species

Optical views: Wall (Citation1965, fig.4; Recent from Woods Hole region), McMinn (Citation1991, pl.2, figs.15–16, as Spiniferites hyperacanthus; Recent from Coast of New South Wales), Pospelova et al. (Citation2005, fig.4, nos.2–3; Recent from Buzzards Bay).

subsp. truncatus (Rossignol Citation1964, p.85, pl.1, figs.5–6; pl.3, fig.1) Lentin and Williams Citation1973, p.126. Holotype: Rossignol Citation1964, pl.1, figs.5–6; reillustrated in de Vernal et al. 1992 (pl.5, fig.9).

Synopsis

A typical Spiniferites bentorii with short, truncated processes. When present, trifurcations are short, with an angle from 120° to 140° to the shaft axis. No bifurcations.

Dimensions

Central body width ca. 50 µm, central body length ca. 60 µm, length of processes 4–8 µm; R = 0.08–0.16.

Remarks

We do not follow Reid (Citation1974, p.598) when considering Spiniferites nodosus (Wall Citation1967) Sarjeant Citation1970 a taxonomic junior synonym of Spiniferites bentorii. Harland (Citation1977, p.98, 99) considered ‘Leptodinium churchillii’ Harland 1968 a junior synonym of Spiniferites bentorii, what we accept when refering to Spiniferites bentorii subsp. truncatus.

References to illustrations of typical forms of the subspecies

Optical views: Rossignol (Citation1964, pl.1, figs.5–6; pl.3, fig.1; late Quaternary from Israel), Wall Citation1965 (figs.1–2, as Spiniferites bentori; Recent from Woods Hole region), Wall and Dale (Citation1966, fig.1; same specimen), Bradford and Wall (Citation1984, pl.6, fig.13; Recent from Gulf of Oman), Pospelova et al. (Citation2002, pl.6, fig.c, as Spiniferites bentorii; Recent from New Bedford Harbor), Pospelova et al. (Citation2005, fig.4.1; same specimen), Shin et al. (Citation2011, fig.2B, as Spiniferites bentorii; Recent from Southern coast of Korea), Attaran-Fariman et al. (Citation2012, fig.9, as Spiniferites sp.3; Recent from Southeast coast of Iran), Liu et al. (Citation2012, fig.3H; Recent from Yellow Sea), Price and Pospelova (Citation2014, pl.3, figs.1–6, as Spiniferites bentorii; late Quaternary from Gulf of California); SEM: Price and Pospelova (Citation2014, pl.4, figs.1–3; pl.5, figs.1–3, as Spiniferites bentorii; late Quaternary from Gulf of California).

References to illustrations of atypical forms of the subspecies

Optical views: Bradford and Wall (Citation1984, pl.3, figs.4–6, 8–9, 12–14; Recent from NW Arabian Sea), Liu et al. (Citation2012, fig.3K, as Spiniferites sp. cf. bentorii; Recent from Yellow Sea).

- var. globus Morzadec-Kerfourn Citation1979 p.222, 224, pl.31, fig.10. Holotype: Morzadec-Kerfourn (Citation1979, pl.31, fig.10).

Dimensions

Central body diameter ca. 60–62 µm, length of processes 16–19 µm; R = 0.28–0.37.

Remarks

This round variety of Spiniferites bentorii is not included in the Identification Key.

Spiniferites bulloideus (Deflandre and Cookson Citation1955, p.264, pl.5, figs.3–4) Sarjeant Citation1970, p.75. Holotype: Deflandre and Cookson Citation1955, pl.5, figs.3–4.

Synopsis

Skolochorate cyst with a small, spherical central body and a simple, smooth wall. The ramosus-type processes are simple and relatively long (1/3 to 2/5 of the equatorial diameter of the central body). Low but clear parasutural septa.

Dimensions

Central body diameter 30–37 µm, length of processes 10–15 µm; R = 0.33–0.41.

Comparison

As its name and the original description demonstrate, Spiniferites bulloideus has a spherical central body. This feature and its small size (30–37 µm) distinguish it from Spiniferites ramosus subsp. ramosus. These two criteria we retain for the Identification Key.

Remarks

Reid (Citation1974, p.600) raised the possibility that the outline of the holotype appears circular because it is a polar view. Otherwise, it would appear ovoidal in shape like those observed in recent sediments. This interpretation is supported by the fact that very few illustrated Quaternary specimens are round. The specimen illustrated by Turon and Londeix (Citation1988, pl.1, figs.10–12) is obviously circular in cross section but shows a polar orientation. The same probably goes for specimens illustrated by Bradford and Wall (Citation1984, pl.3, figs.16–18) and by McMinn (Citation1991) in pl.2, fig.7, but maybe not for the specimen shown by McMinn (Citation1991) in pl.2, fig.12. Specimens from surface sediments depicted by Matsuoka (Citation1985, pl.2, figs.4–6 and figs.7–9) appear very close to the holotype morphology (described from the Miocene of Australia).

Regardless of any stratigraphic consideration, sub-spherical cysts of relatively small size and having a Spiniferites ramosus subsp. ramosus type ornamentation are included in our Identification Key as Spiniferites bulloideus.

References to illustrations of typical forms of the species

Optical views: Deflandre and Cookson (Citation1955, pl.5, figs.3–4; Miocene), Reid (Citation1974, pl.2, figs.17–19; Recent), Bradford and Wall (Citation1984, pl.3, figs.16–18; Recent), Matsuoka (Citation1985, pl.1, figs.10–11, 12; pl.2, figs.4–6 and figs.7–9; Recent), de Vernal et al. (1992, pl.4, fig.4; late Quaternary), Rochon et al. (Citation1999, pl.9, figs.4–6, as Spiniferites ramosus; late Quaternary), Shin et al. (Citation2010, fig.4Q; Holocene); SEM: Morzadec-Kerfourn (Citation1984, pl.3, figs.13–14; late Quaternary).

References to illustrations of atypical forms of the species

Optical views: Wall (Citation1965, fig.6; Recent), Matsuoka (Citation1976a, pl.2, figs.12; Recent), Matsuoka (Citation1985, pl.1, figs.8–9; Recent, Japan), McMinn (Citation1991, pl.2, figs.2, 6; Recent, E Australia).

We do not consider specimens illustrated by Wall and Dale (Citation1968a, pl.1, fig.14, as Hystrichosphaera bulloidea; Culture), Matsuoka (Citation1985, pl.2, figs.1–3; Recent, Japan) and Bujak and Matsuoka (Citation1986b, pl.2, fig.11; Pliocene, Japan) as falling within the morphological range of Spiniferites bulloideus. The specimen illustrated by Wall and Dale (Citation1967, pl.1, fig.K then 1968a, pl.1, fig.15; Recent, NW Atlantic) as Hystrichosphaera bulloidea appears very close to Spiniferites ramosus in Wall and Dale (Citation1970, pl.1, figs.1–15; Culture).

Spiniferites cruciformis Wall and Dale in Wall et al. Citation1973, p.21–22, pl.1, figs.1–6; pl.2, figs.1–4. Holotype: Wall et al. Citation1973, pl.1, figs.2–3.

Synopsis

Proximate to skolochorate or murochorate cyst. Cruciform central body, moderately dorso-ventrally compressed. Central body surface shagreenate to microgranulate. Processes and flanges shagreenate to scabrate. Processes solid sometimes hollow at their base. When present, bifurcations are generally faint. Sutural ornamentation from very low to exuberant. Sutural flanges may be roughly and unevenly perforated.

See discussion in Mudie et al. Citation2018 and Figure F6, additional material for photo stack of a characteristic specimen.

Dimensions

Central body width 34–56 µm, central body length 46–65 µm, ornamentation extending up to 28 µm; R = 0.03–0.55.

Comparison

Despite a large morphological range, especially in the length of the processes and the development of wide, membranous sutural septa (see Wall et al. Citation1973, Mudie et al. Citation2001, Marret et al. Citation2004) this species is easily recognisable because of its cruciform body shape. The shape can however vary from almost rhomboidal (form 4 of Mudie et al. Citation2001 = morphotype C of Marret et al. Citation2004) to extremely cruciform.

References to illustrations of typical forms of the species

Optical views: Wall et al. (Citation1973, pl.1, figs.1–5; late Quaternary from Black Sea), Wall and Dale (Citation1974, figs.1A–H; late Quaternary, Black Sea), Eaton (Citation1996, pl.4, figs.1–5; Pliocene or younger, Black Sea), Kouli et al. (2001, pl.2, figs.4–6; pl.3, figs.1–3, 5–6; pl.4, figs.1–2; late Quaternary, Lake Kastoria, Greece), Mudie et al. (Citation2001, figs.9A–C; pl.1, figs.4–12; late Quaternary, Black Sea), Marret et al. (Citation2004, pl.4, figs.1–9; Recent, Caspian Sea), Sorrel et al. (Citation2006, fig.7, nos.5–14; Holocene, Aral Sea), Marret et al. (Citation2009, pl.1, figs.19–21; Holocene, Black Sea), Londeix et al. (Citation2009, pl.2, figs.1–3; late Quaternary, Marmara Sea), Verleye et al. (Citation2009, pl.3, figs.7–8; Holocene, Black Sea), Leroy and Albay (Citation2010, figs.3, nos.9, 13; Holocene, Lake Sapanca, NW Turkey), Mudie et al. (Citation2010, figs.4, nos.13, 18; late Quaternary, Black Sea), Shumilovskikh et al. (Citation2013, pl.2, fig.10; late Quaternary, Black Sea); SEM: Wall et al. (Citation1973, pl.2, figs.1–4), Kouli et al. (2001, pl.3, fig.4), Marret et al. (Citation2004, pl.5, fig.5), Sorrel et al. (Citation2006, fig.10, nos.4–6).

References to illustrations of atypical forms of the species

Optical views: Wall et al. (Citation1973, pl.1, fig.6), Kouli et al. (2001, pl.1, figs.1–6; pl.2, figs.1–3), Mudie et al. (Citation2001, pl.1, figs.2–3; fig.1; fig.9D), Marret et al. (Citation2004, pl.4, figs.10–11), Rochon et al. (Citation2002, pl.3, figs.1–3; late Quaternary, Black Sea), Mudie et al. (Citation2010, fig.4, nos.14, 22), Mudie et al. (Citation2011, pl.1, fig.9); SEM: Mudie et al. (Citation2001, fig.9E), Sorrel et al. (Citation2006, figs.7, 10).

Spiniferites delicatus Reid Citation1974, p.601–602, pl.2, figs.20–22. Holotype: Reid Citation1974, pl.2, figs.20–22; See Figure F7, supplemental online material for photo stack of the holotype.

Synopsis

Skolochorate cyst with a subspheridal to ovoidal central body. Wall structure simple and solid. Wall surface, including septa and processes, shagreenate to slightly microgranulate to microreticulate. Processes gonal only, may or may not be supported by skeletal rods; when present the rods rise up to the top of the shaft. Characteristic petaloid tips in plan view. Septa well developed, usually membranous and varying greatly in their development in individual specimens; they can be higher at the antapical pole.

Dimensions

Central body width 35–54 µm, central body length 40–60 µm, length of processes up to 29 µm; R = 0.42–0.54.

Comparison

Its massive processes with petaloid tips are characteristic of this species. Spiniferites ristingensis Head Citation2007 has processes of similar shape but has ‘a central body wall structure characterized by a pedium with radial fibres and a thin granular tegillum, whose surface appears microgranular to microreticulate’ (Head Citation2007), while the wall structure is simple in Spiniferites delicatus.

Remarks

Although the holotype has extremely high antapical septa, most of the specimens attributed to this taxon are devoid of such septa. The latter are considered below as ‘typical’ morphologies. There is a single ramosus-type, intergonal process on the holotype but intergonal processes are not common in this species.

References to illustrations of ‘typical’ forms of the species

Optical views: Harland (Citation1977, pl.2, figs.13–15; late Quaternary, off British Isles), Reid and Harland (Citation1977, pl.1, figs.13–14; Quaternary, North Atlantic), Harland (Citation1983, pl.44, figs.5–6; Recent, North Atlantic Ocean), Turon and Londeix (Citation1988, pl.2, figs.10–13; late Quaternary, Alboran Sea), de Vernal et al. (1992, pl.4, fig.5; Quaternary, North Atlantic Ocean), Rochon et al. (Citation1999, pl.6, figs.5–6; late Quaternary, North Atlantic Ocean), Kholeif and Mudie (Citation2009, pl.2, fig.8; late Quaternary, SE Mediterranean), Londeix et al. (Citation2009, pl.2, fig.6; late Quaternary, Marmara Sea), Shin et al. (Citation2011, fig.2A, as Spiniferites bulloideus; Recent, Southern Coast of Korea); SEM: Morzadec-Kerfourn (Citation1984, pl.3, figs.15–16; late Quaternary, off Rhône delta), Turon and Londeix (Citation1988, pl.6, fig.12; pl.7, fig.4; late Quaternary, Alboran Sea), de Vernal et al. (1992, pl.4, fig.7; Quaternary, North Atlantic Ocean), Ellegaard (Citation2000, pl.1, fig.9; Recent, Limfjord, Denmark).

Spiniferites elongatus Reid Citation1974, p.602–603, pl.3, figs.23–24. Holotype: Reid Citation1974, pl.3, figs.23–24; See Figure F8, supplemental online material for photo stack of the holotype.

Synopsis

Proximochorate cyst with an elongate central body. Simple cyst wall with smooth to scabrate surface. Processes free-standing to membranous, usually solid but often hollow at the base, with a smooth surface. Sutural septa varying in height on an individual specimen, and between specimens. Usually a higher sutural flange at the antapex and sometimes at the apex.

Dimensions

Central body width 26–42 µm, central body length 40–59 µm, length of processes 6–12 µm (12–16 µm for antapical); R = 0.19–0.29.

Comparison

The characteristic feature of this species is its elongate form. Even though the septa show considerable variation in height, Spiniferites elongatus differs from ‘Spiniferites frigidus’ in having processes that are clearly distinguishable from the septa, whereas the processes of ‘Spiniferites frigidus’ can be distinguished only from their distal tips sticking out of the septa. Although Spiniferites elongatus is sometimes suturocavate, it differs from ‘Rottnestia amphicavata’ by the absence of true pericoels in the antapical zone. Van Nieuwenhove et al. (Citation2018) no longer consider ‘Spiniferites frigidus’ and ‘Rottnestia amphicavata’ different species, but morphotypes at one end of the morphological spectrum of Spiniferites elongatus. Unlike Spiniferites lazus Reid Citation1974, Spiniferites elongatus does not have fenestrations at the base of the processes but it does have antapical ornamentation.

References to illustrations of typical forms of the species

Optical views: Harland (Citation1973, pl.1, figs.4–6; late Quaternary, off Newfoundland), Reid (Citation1974, pl.3, figs.23–24; Recent, off British Isles), Harland et al. (Citation1980, figs.2K–L; Recent, Beaufort Sea), Harland (Citation1982, pl.1, figs.9–10; Recent, Southern Barents Sea), Harland (Citation1983, pl.44, figs.7–8; Recent, North Atlantic Ocean), Harland and Sharp (Citation1986, pl.1, figs.1–8; Recent, Firth of Forth), Matsuoka (Citation1987a, pl.1, figs.1–3, as Spiniferites frigidus; pl.1, figs.9–10; Recent, off North Japan), Harland (Citation1988b, fig.3h; Quaternary), Turon and Londeix (Citation1988, pl.1, figs.16–18; late Quaternary, Alboran Sea), de Vernal et al. (1992, pl.5, figs.5–6; Quaternary, North Atlantic Ocean), Rochon et al. (Citation1999, pl.6, figs.7–10; late Quaternary, North Atlantic Ocean), Pospelova et al. (Citation2002, pl.6, fig.d; Recent, Apponagansett Bay), Ellegaard et al. (Citation2003, fig.18; Culture), Orlova et al. (Citation2004, fig.20; Recent, East coast of Russia), Head et al. (Citation2005, figs.9m–p; Eemian, SW Baltic Sea), Pospelova et al. (Citation2005, fig.4.4; Recent, Buzzards Bay), Londeix et al. (Citation2009, pl.2, fig.12; late Quaternary, Marmara Sea), Shin et al. (Citation2010, fig.4R; Holocene, off Korea), Price and Pospelova (Citation2011, pl.1, fig.7; Recent, Saanich Inlet), Liu et al. (Citation2012, fig.3D; Recent, Yellow Sea), Ribeiro et al. (Citation2012, fig.3F; Holocene, off West Greenland); SEM: Morzadec-Kerfourn (Citation1984, pl.3, figs.11–12; late Quaternary, off Rhône delta), Harland and Sharp (Citation1986, pl.2, fig.9; Recent, Firth of Forth), Harland (Citation1988a, pl.80, fig.6; Quaternary, North Sea), Ellegaard et al. (Citation2003, figs.23–24, 28, Culture).

References to illustrations of atypical forms of the species

Optical views: Harland (Citation1982, pl.1, figs.11–14; pl.2, figs.1–4, as Spiniferites cf. elongatus; Recent, Southern Barents Sea), Harland and Sharp (Citation1986, pl.1, figs.9–16; Recent, Norwegian Sea), Kholeif and Mudie (Citation2009, pl.2, fig.4; late Quaternary, SE Mediterranean), Heikkilä et al. (Citation2014, pl.1, fig.7; Recent, Hudson Bay).

Spiniferites firmus Matsuoka Citation1983b, p.134, pl.14, figs.4a–b, 5a–c. Holotype: Matsuoka Citation1983b, pl.14, figs.5a–c; reillustrated in He et al. (Citation2009, pl.131, fig.14); See Figure F9, supplemental online material for photo stack of the holotype.

Synopsis

Skolochorate cyst with a subspherical to ovoidal central body whose surface is shagreenate to scabrate. Processes hollow with smooth surface. Parasutural ridges are very low except at the dorsal side of the antapex where connected ‘sirwal-like’ processes may be present.

Dimensions

Central body width 38–50 µm, central body length 40–45 µm, length of processes 16–23 µm; R = 0.42–0.46.

Comparison

This species is very similar to Spiniferites membranaceus but according to Matsuoka (Citation1983b) differs in having weaker development of the parasutural septa. The holotype also differs in having many hollow processes. Spiniferites pacificus differs from Spiniferites firmus in having dorso-antapical processes that are distally open and somewhat less complex with a typical ‘trousers-like’ shape. The difference with Spiniferites falcipedius Warny and Wrenn 1997 is not clear, but might be based on the smaller central body of Spiniferites firmus.

References to illustrations of typical forms of the species

Optical views: Matsuoka (Citation1983b, pl.14, figs.4a–b, 5a–c; Early Pleistocene, off Central Japan).

‘Spiniferites frigidus’ Harland and Reid in Harland et al. Citation1980, p.213–216, figs.2A–J; text-fig.3. Holotype: Harland et al. Citation1980, figs.2G–J; reillustrated in Harland (Citation1983, pl.44, figs.9–10), de Vernal et al. (1992, pl.5, fig.8).

Remarks

Van Nieuwenhove et al. (Citation2018) recommend treating Spiniferites frigidus as a taxonomic junior synonym of Spiniferites elongatus.

Synopsis

Chorate to murochorate cyst with an elongate central body whose surface is smooth to microgranulate or micropunctate. Surface of processes smooth, not always visible as discrete structures since they often form part of the tall, membranous septa.

Dimensions

Central body width 19–50 µm, central body length 50–87 µm, length of processes 10–17 µm; R = 0.32–0.52.

Comparison

‘Spiniferites frigidus’ most closely resembles Spiniferites elongatus but possesses higher septa that are regularly distributed over the cyst, giving it a somewhat rectangular overall shape. However, all transitions between the two end-morphotypes are common and so consequently these species were often not separated. See Van Nieuwenhove et al. (Citation2018).

References to illustrations of typical forms of the species

Optical views: Reid and Harland (Citation1977, pl.2, fig.5; Quaternary, North Atlantic), Harland et al. (Citation1980, figs.2A–J; Recent, Beaufort Sea), Harland (Citation1982, pl.2, figs.7–8; Recent, Southern Barents Sea), Harland (Citation1983, pl.44, figs.9–10; Recent, North Atlantic Ocean), Bujak and; Matsuoka (Citation1986b, pl.1, fig.14; Late Cenozoic, W and N Pacific), Harland and Sharp (Citation1986, pl.2, figs.7–8; Recent, Barents Sea), Matsuoka (Citation1987a, pl.1, figs.4–8; Recent, Akkeshi Bay, North Japan), Harland (Citation1988b, fig.3e; Quaternary), de Vernal et al. (1992, pl.5, fig.8; Quaternary, North Atlantic Ocean).

References to illustrations of atypical forms of the species

Optical views: Harland (Citation1982, pl.2, figs.5–6, 9–16; Recent, Southern Barents Sea), Harland and Sharp (Citation1986, pl.2, figs.1–6; Recent, Barents Sea); SEM: Harland and Sharp (Citation1986, pl.2, figs.10–11; Recent, Barents Sea).

Spiniferites spp. ‘granular’

Remarks

Several species with a coarsely granular central body wall and ramosus-type processes are not always easy to distinguish, notably because the original descriptions do not always specify whether the surface of the processes and septa is smooth or granular. The informal name Spiniferites spp. ‘granular’ encompasses the Spiniferites forms with a strongly granular central body wall and ramosus-type processes. Spiniferites pachydermus (Rossignol Citation1964) Reid Citation1974 or Spiniferites ludhamensis Head Citation1996 can be excluded of that group since they are easier to identify, respectively by the thick wall and big size (ca. 3 µm; 50 × 60 µm), and by an invaginate wall (see Head (Citation1996) for figure and description).

Example

Optical views: Matsuoka (Citation2005, figs.4–5, as Spiniferites cf. scabratus; Recent, Galapagos).

Spiniferites hainanensis Sun and Song Citation1992, p.49, pl.1, fig.12; pl.2, figs.1–2. Holotype: Sun and Song Citation1992, pl.1, fig.12; reillustrated in He et al. (Citation2009, pl.133, fig.1).

Synopsis

Proximochorate to skolochorate cyst. Subspherical central body with smooth to finely granulate wall. Processes solid, ramosus-type, with small holes usually present at the base or middle part of each process. Sutural septa densely perforated.

Dimensions

Central body width 35–42 µm, central body length 43–49 µm, length of processes about 10.5 µm; R = 0.25–0.30.

Comparison

According to Limoges et al. (Citation2018) the distinctive features of Spiniferites hainanensis are the fenestrate, moderately elevated crests between the bases of the processes (op. cit., pl.4, figs.1–4). In this species, the number of intergonal processes differs from one specimen to another and even between sutures on the same specimen. Spiniferites hainanensis differs from Spiniferites hyperacanthus by the presence of occasional intergonal processes and fenestrate septa, and from Hafniasphaera mulstisphaera comb. nov. by not having a vesicular central body or vesicular processes.

References to illustrations of typical forms of the species

Optical views: Sun and Song (Citation1992, pl.1, fig.12; pl.2, figs.1–2; Pleistocene, Hainan Island, off China), Limoges et al. (Citation2018, pl.4, figs.2, 4–7); SEM: Limoges et al. (op. cit., pl.4, figs.1, 3).

Spiniferites hyperacanthus (Deflandre and Cookson Citation1955, p.264–265, pl.6, fig.7) Cookson and Eisenack, Citation1974, p.59. Holotype: Deflandre and Cookson Citation1955, pl.6, fig.7.

Remarks

Proposed by Matsuoka (Citation1985, p.35) the synonymy of Spiniferites hyperacanthus with Hystrichosphaera furcata var. multiplicata (now Spiniferites ramosus subsp. multiplicatus) is not accepted here.

Synopsis

Skolochorate cyst with a spherical to subspherical central body whose surface is smooth to faintly microgranulate. Surface of processes smooth. Both gonal and intergonal (at least 1, often 2 on each suture) processes present. Paratabulation weakly expressed by very low sutural ridges. See also Limoges et al. (Citation2018).

Dimensions

Central body diameter 54–59 µm, length of processes 13–20 µm; R = 0.24–0.34.

Comparison

The characteristic feature of Spiniferites hyperacanthus is the consistent presence of intergonal processes and the small or greatly reduced septa. Spiniferites hyperacanthus differs from Spiniferites mirabilis in not having an antapical crown-like flange; and from Spiniferites ramosus subsp. multiplicatus (sensu Londeix, see below) in having a more rounded central body and at least one intergonal process on each suture. See above for comparison with Spiniferites hainanensis.

References to illustrations of typical forms of the species

Optical views: Wall (Citation1967, pl.14, fig.3; late Quaternary, Caribbean Sea), Turon and Londeix (Citation1988, pl.2, figs.4–5; late Quaternary, Alboran Sea), McMinn (Citation1991, pl.2, figs.3, 8, 13; Recent, Coast of New South Wales), de Vernal et al. (1992, pl.4, fig.9; Quaternary, North Atlantic Ocean), Mao and Harland (1993, pl.2, fig.1; late Quaternary, South China Sea), Rochon et al. (Citation1999, pl.7, figs.8–10; late Quaternary, North Atlantic Ocean), Londeix et al. (Citation2009, pl.2, fig.7; late Quaternary, Marmara Sea), Liu et al. (Citation2012, fig.3F; Recent, Sishili Bay, Yellow Sea), Matsuoka (Citation1985, pl.3, figs.5–9; Recent, off Western Japan); SEM: Zhao and Morzadec-Kerfourn (Citation2009, fig.7a; late Quaternary, Izu-Bonin, NW Pacific).

References to illustrations of atypical forms of the species

Optical views: Wall (Citation1965, figs.24–29, as Spiniferites bentori; Recent, Woods Hole region), Reid (Citation1974, pl.4, fig.35; Recent, off British Isles), Matsuoka (Citation1985, pl.3, figs.5, 10–12; Recent, off Western Japan), Rochon et al. (Citation1999, pl.7, figs.5–7; late Quaternary, N Atlantic Ocean and adjacent seas), Kholeif and Mudie (Citation2009, pl.2, fig.1; late Quaternary, SE Mediterranean).

‘Spiniferites’ inaequalis Wall and Dale in Wall et al. Citation1973, p.22, pl.1, figs.7–8. Holotype: Wall et al. Citation1973, pl.1, figs.7–8.

Now Impagidinium according to Londeix et al. (Citation2009, p. 68). This taxon is no longer assigned to Spiniferites since it lacks processes, so it was not included in the Identification Key.

Spiniferites lazus Reid Citation1974, p.604–605, pl.3, figs.25–27. Holotype: Reid Citation1974, pl.3, figs.25–27.

Synopsis

Skolochorate cyst with an ovoidal-elongate central body. Moderately thick wall (ca. 1–1.5 µm). An apical boss is often present. Cyst surface (including processes) microgranular to reticulate. Processes have a conical and fenestrate base and frequent bifid recurved tips. Septa are rather low.

Dimensions

Central body width 31–42 µm, central body length 44–58 µm, length of processes 12–25 µm; R = 0.39–0.43.

Remarks

Spiniferites lazus was originaly described as having ‘A clear geminal process with a high fenestrate flange […] along the junction of 6‴ and 1⁗’ (Reid, Citation1974, p. 605). This antapical flange cannot be observed on the illustration of the holotype (op. cit., pl. 25–27) and has been noted only occasionally on other specimens of the species: thus, we do not include reference to this feature in the Identification Key.

Comparison

The ovoidal-elongate central body, the surface ornamentation and the processes that are fenestrate at their base and along their length make this species easily recognizable, although the orientation of some specimens makes them appear subspherical. It differs from Spiniferites septentrionalis by the lack of fenestrate distal process ends.

References to illustrations of typical forms of the species

Optical views: Reid (Citation1974, pl.3, figs.25–27; Recent), Harland (Citation1977, pl.1, figs.1–4; late Quaternary), Harland (Citation1983, pl.44, figs.11–12; Recent), Turon and Londeix (Citation1988, pl.2, figs.6–7; late Quaternary); Rochon et al. (Citation1999, pl.8, figs.1–4; late Quaternary), Kholeif and Mudie (Citation2009, pl.2, fig.2; late Quaternary); SEM: Harland (Citation1988a, pl.79, figs.5–6; Quaternary).

References to illustrations of atypical forms of the species

SEM: Harland (Citation1988a, pl.79, figs.3–4; Quaternary).

Spiniferites ludhamensis Head Citation1996, p.557, fig.12, nos.3–14; fig.13; fig.14, nos.1–3. Holotype: Head Citation1996, fig.12, nos.5–9; See Figure F10, supplemental online material showing photo stack of the holotype.

Synopsis

Proximochorate to skolochorate cyst with a round-ovoidal central body. Wall structure invaginate, appearing as with a bubble-string-like structure (see Head Citation1996 for figure and extensive description), giving the appearance of granulae on the surface. Processes hollow along their entire length including branched distal terminations. Surface of processes microgranulate (sensu Habib and Knapp Citation1982, p.344). Occasional intergonal processes. Sutures delineated by 1–2 µm high folds.

Dimensions

Central body width 34–41 µm, central body length 38–49 µm, length of processes 10–15 µm; R = 0.29–0.31.

Comparison

The distinctive wall structure of Spiniferites ludhamensis is also found in Spiniferites ristingensis, but the latter has delicatus-type processes (membranous and more or less solid; Head Citation2007, p.1012). Spiniferites ludhamensis differs from Hafniasphaera multisphaera comb. nov. in lacking the vesicular wall of both the central body and processes in the latter; and from Spiniferites pachydermus in not having smooth, almost solid, ramosus-like processes or a wall that is somewhat tectate (sensu Moore et al. Citation1991) or intragranulate (sensu Kremp Citation1965).

References to illustrations of typical forms of the species

Optical views: Head (Citation1996, fig.12, nos.3–14; fig.14, nos.1–3).

Spiniferites membranaceus (Rossignol Citation1964, p.86, pl.1, figs.4, 9–10; pl.3, figs.7, 12) Sarjeant Citation1970, p.76. Holotype: Rossignol Citation1964, pl.1, figs.4, 9–10.

Synopsis

Chorate cyst with a round ovoidal central body whose surface is smooth to scabrate, rarely microgranulate. Processes only gonal, ramosus-type. A characteristic antapical flange is present along the 4‴/1⁗ suture, with a ‘carpet-like’ shape in typical specimens. Paratabulation highlighted by low septa.

Dimensions

Central body diameter 50–57 µm, length of processes 20–25 µm; R = 0.40–0.44.

Remarks

Different morphologies are actually grouped under this name. We recommend including in Spiniferites membranaceus only specimens with a morphology close to that of the holotype, i.e. ramosus-type gonal processes, presence of a ‘carpet-like’ antapical flange characterised by depressed lateral borders and a simple distal edge; the stems of the two dorso-antapical processes bearing the flange are characteristically weakly expressed. Other specimens with an antapical flange like those depicted by Wall (Citation1967, pl.14, figs.14–15) from the Caribbean should be referred to as Spiniferites cf. membranaceus, since the antapical flange is supported by distinctly stout and rod-like processes unlike the holotype and the specimens mentioned below as typical.

Comparison

The distinctive feature of this species is its antapical, ‘carpet-like’ flange; to avoid misidentification, care must be taken that it is antapical since other species of Spiniferites have septa between cingular processes that often appear higher and might be confused with an antapical septum. Spiniferites membranaceus most closely resembles Spiniferites belerius but the latter has a trumpet shaped process rather than a flange. Spiniferites firmus also has an antapical flange but, according to Matsuoka (Citation1983b, p.134), Spiniferites membranaceus differs in having more conspicuous parasutural septa. The holotype of Spiniferites firmus also differs in having hollow processes (see supplementary online material, Figure F9). With its ‘sirwal-like’ pair of wide and membranous antapical processes Spiniferites asperulus is close to Spiniferites membranaceus and might be interpreted as a variant of the latter with the surface of the central body and processes being microgranular. Spiniferites membranaceus differs from Spiniferites mirabilis by the lack of consistent intergonal processes.

References to illustrations of typical forms of the species

Optical views: Rossignol (Citation1964, pl.3, figs.7, 12; late Quaternary, Israel), Reid (Citation1974, pl.3, figs.28–30, 31; Recent, off British Isles), Harland (Citation1977, pl.2, figs.11, 12; Recent and late Quaternary, off British Isles), Harland (Citation1977, pl.2, figs.9–10, as Spiniferites belerius), Reid and Harland (Citation1977, pl.1, fig.7; Quaternary, North Atlantic), Reid and Harland (Citation1977, pl.1, figs.9–10, as Spiniferites belerius), Harland (Citation1983, pl.45, figs.3–4; Recent, N Atlantic Ocean and adjacent seas), Harland (Citation1988a, pl.82, figs.7–8; Quaternary, North Sea), Turon and Londeix (Citation1988, pl.1, figs.6; late Quaternary, Alboran Sea), McMinn (Citation1991, pl.2, figs.1, 5, 11; Recent, Coast of New South Wales), Marret and de Vernal (Citation1997, pl.4, figs.4; Recent, southern Indian Ocean), Rochon et al. (Citation1999, pl.8, figs.5–9; late Quaternary, N Atlantic Ocean and adjacent seas), Pospelova et al. (Citation2005, fig.4.5; Recent, Buzzards Bay), Pospelova and Kim (Citation2010, pl.1, fig.E; Recent, southern South Korea); SEM: Turon and Londeix (Citation1988, pl.7, fig.3; late Quaternary, Alboran Sea), Lewis et al. (Citation1999, figs.1–4, 12; Recent; fig.9; Culture).

References to illustrations of atypical forms of the species

Optical views: Wall (Citation1967, pl.14, figs.14–15; late Quaternary, Caribbean Sea), Harland (Citation1977, pl.1, figs.11, 16; late Quaternary, off British Isles), Bradford and Wall (Citation1984, pl.4, figs.5–7; Recent, NW Arabian Sea), de Vernal et al. (1992, pl.5, fig.11; Quaternary, North Atlantic Ocean), Ellegaard et al. (Citation2003, fig.43; Recent/Culture); SEM: Lewis et al. (Citation1999, figs.5–8; Culture), Ellegaard et al. (Citation2003, fig.51; Recent/Culture).

We consider that the following specimens do not fall within the morphological range of Spiniferites membranaceus: Mao and Harland (1993, pl.2, fig.11; Pleistocene, South China Sea), Ellegaard et al. (Citation2003, figs.41–42, 44–45; Recent/Culture), Orlova et al. (Citation2004, fig.21; Recent, East coast of Russia), Pospelova et al. (Citation2005, fig.4, 6; Recent, Buzzards Bay), Verleye et al. (Citation2009, pl.3, fig.9; Holocene, Black Sea).

Spiniferites mirabilis (Rossignol Citation1964, p.86–87, pl.2, figs.1–3; pl.3, figs.4–5) Sarjeant Citation1970, p.76.

- subsp. mirabilis. Autonym. Holotype: Rossignol Citation1964, pl.2, figs.1–2.

Synopsis

Chorate cyst with a spherical to subspherical central body. Surface of both central body and processes smooth to microgranulate. Processes have generally a circular cross section. Intergonal processes numerous (usually 2 between precingular and postcingular boundaries) and typically bifurcate. The antapical area is ornamented (hence its name) by a suturocavate flange along the 4‴/1⁗ suture, and which sometimes extends along adjacent sutures. Paratabulation weakly defined by faint ridges (sometimes absent).