1. Introduction

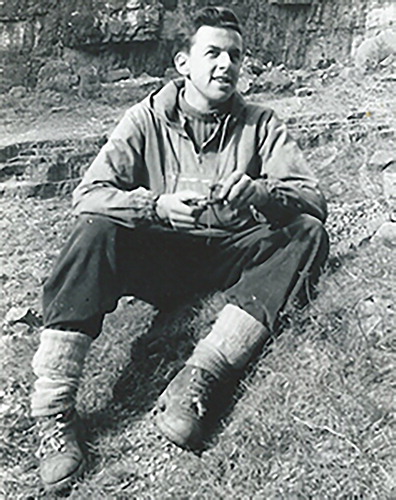

A photograph of Bernard Owens relaxing during an undergraduate field trip to the Yorkshire Dales during the late 1950s; note his trademark pipe.

The eminent Carboniferous palynologist Bernard Owens passed away on the 31st of July 2019 at the age of 80. He became enthused by the natural sciences at school, studied geology and researched in palynology at the University of Sheffield, UK, and undertook a postdoctoral research fellowship in Canada. Bernard then joined the Institute of Geological Sciences (now the British Geological Survey), where he worked for the majority of his career. He was an expert on the biostratigraphy, morphology and taxonomy of Late Palaeozoic miospores. While being a discipline group manager and researcher for the geological survey, Bernard also worked tirelessly for several volunteer organisations, most notably the Commission Internationale de Microflore du Paléozoïque. Bernard was also was a very enthusiastic conference organiser, editor and project manager. Many of his international collaborative projects were on the Palaeozoic and Mesozoic palynology of North Africa and the Middle East. This article documents his life, and the huge contribution Bernard made to the world of palynology (see also McLean et al. Citation2020).

2. Family background and early years (1938–1957)

Bernard Owens was born in Darlington, a large market town in County Durham, northeast England, on the 17th of November 1938. His parents were Fenwick Owens and Annie Owens (née Graham) and Bernard had an older brother, Gordon. Fenwick Owens was a mechanical engineer from Coundon, a mining village in County Durham. He installed and maintained rock processing plant in quarries. Unfortunately, Fenwick suffered an accident in Barrington Chalk Quarry, Cambridgeshire in which he lost an arm. Subsequently the family moved back north and set up home in Darlington before Bernard was born. Due principally to the quarry accident, Fenwick changed career and became an insurance agent.

Bernard was raised in Clifton Road and Hawthorn Street, immediately east of South Park, one of the several green areas in Darlington (Appendix 1 of the Supplemental Data, Figure 1). The immediate area is ∼1 km south of the town centre and is a solidly working class district of terraced houses. Most of the locals worked on the railways or at Cleveland Bridge and Engineering. The latter is a world famous bridge building and structural engineering company who, for example, helped to build the Forth Road Bridge in Scotland and the Humber Bridge in Yorkshire. The area where Bernard grew up is also very close to Darlington railway station and Feethams, the old home of Darlington Football Club near the banks of the River Skerne. The station and the football ground were both highly influential in Bernard’s life. The former was responsible for his lifelong interest in railways, together with Darlington’s place in railway history. The Stockton and Darlington Railway, designed by the engineer George Stephenson (1781–1848, the ‘Father of Railways’), was the first passenger railway in the world, transporting 550 passengers from Stockton-on-Tees to Darlington on the 27th of September 1825. Growing up so close to the home of Darlington Football Club, it was natural that Bernard became a keen supporter of his local team. Later in life he only very rarely attended matches but he always maintained an encyclopedic knowledge of the club’s fluctuating fortunes.

Bernard was born less than a year before the outbreak of World War II, and he was almost seven years old when the war ended. Hence his memories of the horror and privations of that time would have thankfully been relatively faint. Bernard attended his local primary school, Beaumont Street, which was demolished in the 1970s. Bernard’s father, Fenwick Owens, passed away in 1949, when Bernard was only 10 years old. At this very sad time, Bernard passed his Eleven-Plus examination at Beaumont Street School and was offered a place at a boarding school via a scholarship. Bernard started there, but hated the boarding school with ‘an absolute vengeance’ and soon transferred to Darlington Grammar School, his local secondary school. This was to be a pivotal move for Bernard because he was taught Ordinary Level geography and Advanced Level geography and geology by Jack Waltham and the late George Chapman. Several future geologists such as Malcolm Hart, Jack Pattison and John Varker, were also mentored by these two charismatic and inspirational teachers. Jack Waltham and George Chapman introduced Bernard to the geology of the Yorkshire Dales, and he undertook fieldwork in the Swaledale area while in the sixth form studying Advanced Level geology. Bernard immediately fell in love with this beautiful area, one of the most northerly dales in the Yorkshire Dales National Park. He continued to work on the Carboniferous strata of this region when he was at the University of Sheffield (Section 3). Jack Waltham and George Chapman habitually produced other future palynologists who studied and researched at the University of Sheffield, notably Rex Harland, George Hart and John Richardson (Hart Citation2008, p. 285). Jack Waltham is still alive, and Bernard met up with him in recent years.

As a teenager, Bernard obtained a part-time job at a local market garden just outside Darlington. It was there that he developed his lifetime love of gardening and horticulture, in particular the growing and propagating of chrysanthemums and dahlias. Perhaps this early passion for plants helped develop his later interest in the floras of the Devonian and Carboniferous. Bernard’s real sporting love was bowls (lawn bowls). This tricky sport uses balls that are roll-biased so that they take a curved path. Bernard excelled in this sport as a schoolboy and, before he left for the University of Sheffield in 1957, he was a bowls champion on the lawns of South Park in Darlington.

3. Undergraduate and Postgraduate student life in Sheffield (1957–1963)

Following the inspired teaching of geology by Messrs Waltham and Chapman at Darlington Grammar School, Bernard applied to read this subject at the University of Sheffield and was accepted. He began his studies in the autumn of 1957 and graduated in the summer of 1960 with an Upper Second (2.1) Honours Degree (Appendix 1 of the Supplemental Data, Figure 2). His undergraduate geological mapping dissertation was on the Carboniferous (Visean–Bashkirian) Yoredale Group of middle Swaledale, North Yorkshire and Bernard’s first paper was based on this unit, with emphasis on the chert horizons (Owens Citation1959).

Bernard had always been interested in palaeontology, and he became enthused with the idea of researching in palynology after he graduated. There may well have been an element of peer pressure because almost half of the undergraduates in the Sheffield Honours Geology class of 1960 undertook postgraduate research (Owens et al. Citation2019). The research interests of many of the staff of the Department of Geology at Sheffield were centred on the Carboniferous. This, combined with Bernard’s heritage from the coalfields in the northeast of England, meant that he had a natural affinity with Carboniferous geology. So Bernard stayed on at the University of Sheffield to undertake a PhD. The Head of the Department of Geology there, Professor Leslie Moore (1912–2003), was beginning to establish a school of palynology at Sheffield that would go on to train over 300 palynologists (Spinner et al. Citation2004, Sarjeant Citation1984, Spinner Citation1986, Wellman Citation2005).

Bernard was the first research student of Roger Neves who, at that time, was a relatively junior academic in the Department of Geology. In fact, Roger was awarded his PhD (An investigation into Namurian microflora of parts of the Southern Pennines Basin) in 1960, the same year that Bernard began his doctorate research. Roger was a fellow northerner, and was rapidly becoming a leading expert on Carboniferous miospores (e.g. Neves Citation1961). The data from his first paper (Neves Citation1958) were reinterpreted by Bill Chaloner, who coined the term ‘the Neves effect’ (Chaloner Citation1958, Riding et al. Citation2020). Bernard and Roger would have known each other very well from Bernard’s undergraduate days. The two were kindred spirits, and they worked together extremely well. Bernard’s research topic was the palynology of the Carboniferous strata outcropping around Stainmore, a remote rural parish in Cumbria, northwest England. The project was funded by the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research. Bernard completed his PhD in three years, graduating in 1963. The title of his thesis is A palynological investigation of the Namurian and Westphalian sediments of the Stainmore Outlier, Westmorland and his third paper, Owens and Burgess (Citation1965), is based on the PhD thesis. In this article, Bernard collaborated with his future colleague at the geological survey, Iain C. Burgess, to produce an integrated account of the lithostratigraphy, macropalaeontology and palynology of the Millstone Grit and the Pennine Coal Measures groups which form a major outlier of Carboniferous strata at Stainmore.

The Department of Geology at that time was based on the top floor of the Applied Science Building on Mappin Street. Bernard prepared his samples there and spent hours at the microscope with a highly eclectic (some would say eccentric!) set of colleagues which included Barrie Dale, George Hart, Tony Jenkins, Herbert Sullivan and Graham Williams. By all accounts they were a very lively bunch indeed. Convoluted and highly imaginative practical jokes were rife, normally with Bernard as the ringleader. It seems likely that this was around the time that Bernard acquired his nickname of ‘Jesse’, after the famous American track and field athlete Jesse Owens (1913–1980). Bernard met his wife, Pat Cunningham, who was completing her nursing training at Sheffield Royal Infirmary and midwifery training at Sheffield City Hospital, and they married on Thursday the 21st of November 1963. They had a very short honeymoon in Edinburgh.

4. Postdoctoral research in Canada (1963–1965)

With the experience of his PhD behind him, Bernard’s research trajectory on Late Palaeozoic miospores was set for life. He was offered a one-year postdoctorate research fellowship funded by the National Research Council of Canada to work with Colin McGregor at the Geological Survey of Canada in Ottawa, Ontario. Bernard and Pat travelled westwards to Canada in the immediate aftermath of the brutal and tragic assassination of US President John F. Kennedy in Dallas, Texas. The public slaying of this charismatic and highly popular world leader on Friday the 22nd of November 1963 was a politically seismic event. Transatlantic travel on that weekend in late November 1963 was a very uncomfortable experience indeed because fears were rife of possible impending international conflict resulting from the murders of Kennedy, Dallas Police Officer J.D. Tippit and the alleged presidential assassin, Lee H. Oswald (Summers Citation2013). Bernard and Pat travelled to Canada by sea on board the RMS Sylvania on the Liverpool to Halifax, Nova Scotia voyage. They boarded the ship on its interim stop at Greenock, west of Glasgow, following their brief honeymoon in Scotland (Appendix 1 of the Supplemental Data, Figure 3).

Colin McGregor was an eminent researcher on the Devonian miospores of North America (e.g. McGregor Citation1960, Citation1967, Citation1979); he retired some years ago. He was an excellent mentor and role model for Bernard, who worked on the Devonian miospores of Canada during his year in Ottawa (McGregor and Owens Citation1966). Bernard’s specific project was to work on material collected by Colin from the Middle and Upper Devonian strata of the Queen Elizabeth Islands, the most northerly group of islands in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago (Owens Citation1971).

Towards the end of the fellowship with Colin McGregor, Bernard began the task of finding a permanent position in palynology. He applied for a job with the Institute of Geological Sciences in the UK, and was offered the post. Hence, following an enjoyable and productive postdoctoral fellowship, Bernard and Pat returned to the UK in early 1965.

5. A scientific career at the Institute of Geological Sciences/British Geological Survey (1965–1998)

On the 1st of March 1965, Bernard Owens started work for the Institute of Geological Sciences (IGS) at the Leeds Office (Appendix 1 of the Supplemental Data, Figure 4). The IGS was previously known as the Geological Survey of Great Britain, and was rebranded in early 1965. Bernard and Pat’s first home back in the UK upon arriving back from Canada was a house on Valley Drive, Halton in east Leeds (Appendix 1 of the Supplemental Data, Figures 5, 6). It was a short walk from the IGS office on the Leeds Ring Road at Crossgates, and to Killingbeck and Seacroft hospitals where Pat worked part-time. Incidentally, Valley Drive was close to the outcrop of the Middleton Main coal seam and a parting of this coal was present under the soil in behind Bernard’s garage. Bernard quickly established a beautiful garden at Valley Drive, and also helped maintain the gardens of the elderly neighbours. The Owens family later moved to Elmete Drive near Roundhay Park in northeast Leeds during 1972 (Appendix 1 of the Supplemental Data, Figure 7), and stayed there before moving to Plumtree Park in Keyworth, Nottingham in 1985 when Bernard had to move to the Headquarters at Keyworth after the Leeds office was closed.

Bernard joined the Carboniferous palaeontologists Mike Calver and Bill Ramsbottom in the northern England branch of the IGS Palaeontology Department in Leeds; the majority of the palaeontologists were based on London. Bernard was the first palynologist to be employed by the geological survey since its inception in 1835. The Director of IGS at the time of Bernard’s recruitment was Sir Cyril James Stubblefield (1901–1999). Nineteen years later, IGS was renamed the British Geological Survey (BGS) in 1984. Bernard remained with the organisation until his formal retirement in 1998.

Bernard’s first boss (Chief Palaeontologist) was Richard V. Melville, who was based in London. Mike Calver was the head of the Leeds branch at the time, and he managed Bernard on a day-to-day basis. Bernard later worked under two more Chief Palaeontologists, Mike Calver (from 1971) and Bill Ramsbottom (from 1980). Between 1965 and the early 1980s, the numbers of palaeontologists in IGS steadily expanded, reaching 28 in 1981 (Appendix 1 of the Supplemental Data, Figure 8). Many of Bernard’s immediate colleagues in Leeds worked on Carboniferous macropalaeontology, supporting field mapping activities throughout northern England. These included Mike Calver, Murray Mitchell, Jack Pattison (a fellow Darlingtonian), Bill Ramsbottom and Nick Riley. Bernard worked hard at his scientific endeavours for IGS/BGS, and he rose rapidly through the ranks of the British scientific civil service. He was promoted to Principal Scientific Officer, the career grade for scientists at that time, in the summer of 1972. To rise to this level in just over seven years was a major achievement.

Bernard’s expertise on Carboniferous miospore biostratigraphy was much in demand. He worked on many projects, examining samples collected by field mappers, and material from the many onshore stratigraphical boreholes that were being drilled at this time. For example, during his first year at the survey, Bernard worked on the Carboniferous palynology of samples from the Boscastle and Macclesfield map sheets, the Canonbie Coalfield, and the Throckley Borehole. He worked on a deep borehole at Eyam in Derbyshire, (Dunham Citation1973). This small lead mining village is famous for the outbreak of bubonic plague there in 1665 and 1666. The entire village heroically quarantined themselves in an attempt to halt the spread of the plague (Paul Citation2012). From the early 1970s onwards, IGS/BGS undertook biostratigraphical work on offshore samples dredged or drilled by the Continental Shelf Department, and samples from North Sea oil and gas boreholes. Specifically, Bernard worked on material from the first North Sea exploration well and unexpectedly determined that Devonian strata had been penetrated. Clearly the North Sea exploration effort created substantially more work on microfossils, and BGS recruited more micropalaeontologists. Chief Palaeontologists Mike Calver and Bill Ramsbottom were very happy indeed for Bernard to informally manage this growing group of micropalaeontologists at IGS. Bernard thoroughly enjoyed this management role, which was never actually made official until he formally took over leading the entire BGS biostratigraphy/palaeontology group in 1985. He vigorously promoted and publicised micropalaeontology in IGS/BGS, and palynology in general (e.g. Owens Citation1980, Citation1981).

Bernard expanded micropalaeontology at the survey so that the organisation could handle all the varied demands for the biostratigraphy of mainly offshore samples. Over the years, BGS has tackled all the major microfossil groups with the exception of silicofossils. Nicky Hine and Alan Medd worked on calcareous microfossils and Mike Reynolds researched Carboniferous conodonts. The organisation employed several experts on foraminifera including Peter Bigg, Martin Brasier, Brenda Coleman, Diane Gregory, Murray Hughes and Angela Strank. Ostracods were handled by Ian Wilkinson. Of course palynology was Bernard’s pet topic, and he built up a comprehensive team of workers on organic microfossils. Palynologists at BGS from 1965 onwards who were of course all recruited by Bernard include Hugh Barron, Roger Davey, Rex Harland, Dick Lister, Aideen McNestry, Stewart Molyneux, Jim Riding, Mike Stephenson, Joanna Thomas, Bob Turner, Nick Turner, Geoff Warrington and Ron Woollam. The expertise of this group meant that the survey had the entire Phanerozoic Eon covered for the majority of Bernard’s career.

Bernard will be remembered for his decisive management style. He analysed situations very quickly and worked out solutions equally speedily. Bernard was never one for playing to the gallery; he did not shy away from making decisions for the common good which may have been unpopular. He was always very supportive of his team, and led the group with aplomb through good times and some very tough periods. One of the reasons that Bernard kept a sizeable team of palaeontologists together for such a long time was his almost evangelical entrepreneurial spirit and zeal. From the mid to late 1980s, the internal demand for biostratigraphy and palaeontology in BGS decreased substantially, and Bernard had to be creative in finding new work. He was very quick to identify new commercial opportunities in the outside world, and would attempt to exploit them wherever possible. BGS did not seriously start commercial work until this time. In fact, prior to the 1980s, Bernard’s efforts to undertake consultancy type work on behalf of the survey did not meet with the approval of the management culture of the time. How times have changed! However, when the climate was more conducive to commercial work, Bernard was responsible for one of the first of these endeavours by the organisation. This was the concept of the ‘biostratigraphical package’, a comprehensive illustrated identification guide to specific fossil groups and ages. The first one of these was a comprehensive, nine-volume, guide to British Jurassic dinoflagellate cysts successfully marketed to the oil industry in 1982 (Riding and Woollam Citation1982). This module sold out, and made a substantial operating surplus. Bernard’s innovative approach to earned income projects was unusual in the BGS of the early 1980s, but he was way ahead of the curve. The organisation had to generate more of its income from external sources due to falling revenues from the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC – the then parent body of IGS/BGS) and various government departments throughout this politically turbulent period (Allen Citation2003). Bernard led by example and undertook much commissioned research for oil companies exploring onshore UK, especially the East Midlands oilfield in the 1980s. This commitment to commercial work continued even after Bernard took over full management responsibility for the biostratigraphy/palaeontology group in 1985. He also promoted his team working for other NERC centres. In the late 1980s he instigated collaboration between BGS and its sister organisation the British Antarctic Survey (Duane et al. 1992).

When he was a PhD student at Sheffield, Roger Neves taught Bernard had how to pick and mount single-grain palynomorph slides. These are microscope slides with one (or several) individually picked specimens on them (e.g. Doher Citation1980, p. 27–28). Most evenings after work at IGS/BGS, Bernard would relax by producing single-miospore mounts, thereby producing thousands of high-quality reference slides. Many of these were distributed to colleagues and institutions all over the world, but most are curated at BGS in the ‘Bernard Owens Collection’ which covers Carboniferous miospores in the BGS Taxonomy Online web resource (Stephenson and Owens Citation2006).

Bernard worked with research students throughout his career. When he was at BGS, he co-supervised the PhD research of John Marshall at the University of Bristol. He was awarded Individual Merit status in 1989, which is a recognition of outstanding researchers throughout the scientific civil service.

6. The University of Sheffield (1996–2019)

Bernard was obliged by the old NERC contract system to formally retire from BGS on the 30th of November 1998, at the age of 60 after 33 years of service. He did, however, accept emeritus status with BGS, and was an Honorary Research Associate between December 1998 and 2003. Despite the emeritus position, Bernard felt, with justification, that he was at the top of his game at the time, and absolutely emphatically did not wish to formally retire. Happily for him, has was able to move back to the University of Sheffield as an emeritus Professor in 1996, and he commuted to his almer mater several times a week from then onwards. He was awarded a DSc by the university in 1998 (Appendix 1 of the Supplemental Data, Figure 9). This new endeavour meant that he effectively had two jobs for two years; a situation he absolutely relished. He was made Director of the Centre for Palynological Studies and an associated Industrial Palynology Unit. From the 2000–2001 academic year, these were hosted in the Department of Animal and Plant Sciences due to the Department of Geology having closed down. Bernard worked alongside David Jolley, Duncan McLean, Ted Spinner, who retired in 1997 (Owens et al. Citation2019), Charles Wellman and the laboratory technical staff. Bernard never left the University of Sheffield, retirement was simply not an option for him. This was a lifetime role, and he worked at Sheffield, although obviously not full-time, right to the end.

7. The scientific work of Bernard Owens (Citation1959–2019)

Bernard published consistently throughout his career; 103 items are listed in Appendix 2 of the Supplemental Data. The greater part of his output was during his 33-year career at IGS/BGS. However, his first three papers were published during his student days at Sheffield. Throughout the years, he concentrated on the biostratigraphy, classification, morphology and taxonomy of Carboniferous miospores. His contributions on this topic are many. Bernard initially focussed on the UK and Canada, including work covered in his PhD and his postdoctoral research fellowship (Owens and Burgess Citation1965, McGregor and Owens Citation1966, Neves and Owens Citation1966, Owens Citation1971). Some of his early papers written at IGS were on the Devonian, particularly the Devonian–Carboniferous transition (e.g. Owens and Streel Citation1967, Owens Citation1970a). During the 1970s, Bernard began to concentrate on the Carboniferous (Tournasian to Moscovian) palynology of UK and greater Europe (e.g. Owens et al. Citation1976). Some of these items were contributions to geological survey memoirs (e.g. Owens Citation1973). His first paper on Carboniferous stratotypes (section 8) was Calver and Owens (Citation1977). Also in the late 1970s, he began to investigate the correlation of Carboniferous miospore biozones beyond Europe (e.g. Owens et al. Citation1978). This style of work was continued throughout his career, and is exemplified inter alia by Podgainaya et al. (Citation1996) and Clayton et al. (Citation1998). Bernard’s first of several works on the Middle East was Owens and Visscher (Citation1981). By far his most extensively cited paper is Clayton et al. (Citation1977). However, Owens and Burgess (Citation1965), Neves and Owens (Citation1966), Owens et al. (Citation1976) and Owens et al. (Citation1977) also are frequently referred to by other researchers on Carboniferous palynology. Bernard did not strictly confine himself to the Devonian and Carboniferous; he published on the Lower Palaeozoic (Wadge et al. Citation1967), and on palynological techniques (e.g. Owens Citation1970b, Riding et al. Citation2007). His final publication issued during his lifetime was Owens et al. (Citation2019). However, shortly prior to his death Bernard completed his part of a new Carboniferous miospore biostratigraphy for the UK and Ireland.

8. The Subcommission on Carboniferous Stratigraphy (1963–2019)

Bernard attended the Fifth Congress of Carboniferous Stratigraphy and Geology in Paris, France in 1963. This began a lifelong association with Subcommission on Carboniferous Stratigraphy (SCCS), a specialist group under the aegis of the International Union of Geological Sciences. He was a corresponding member of the SCCS from 1984 until his death in 2019. He attended every Congress of Carboniferous Stratigraphy and Geology (subsequently the International Congress on Carboniferous and Permian - ICCP) up until the Fifteenth of these events in Utrecht, The Netherlands in 2003. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Commission Internationale de Microflore du Paléozoïque (CIMP) was an integral part of the SCCS. Much of the research undertaken by CIMP was related to miospores from the Carboniferous (and the Devonian–Carboniferous boundary), with alternate CIMP meetings being held within each Congress of Carboniferous Stratigraphy and Geology. This was hence a natural place for Bernard to develop his research activities and collaborations, and he contributed many papers at these conferences over the years (Appendix 2 of the Supplemental Data). Much of Bernard’s involvement with the SCCS involved describing boundary stratotypes. Bernard’s colleague at IGS, Bill Ramsbottom justifiably asserted that the UK and Ireland could be taken as representing a stratotype section for all but the youngest Carboniferous. Bernard provided the palynostratigraphical component to the arguments for establishing stratotypes in Britain (Ramsbottom Citation1981, Owens Citation1982, Owens et al. Citation1985; Citation1990, Riley et al. Citation1985; Citation1993). A culmination of this was when Bernard helped to organise a symposium entitled ‘Biostratigraphic Data for a Mid-Carboniferous Boundary’ in Leeds, UK in 1982 (Ramsbottom et al. 1982) which directly resulted in the formation of the Mid Carboniferous Boundary Working Group of the SCCS at the Tenth Congress of Carboniferous Stratigraphy and Geology in Madrid, Spain. Bernard became heavily involved in the eventually unsuccessful proposal to place the Mid-Carboniferous boundary in Stonehead Beck, Cowling, North Yorkshire in northern England (Lane et al. 1983, Riley et al. Citation1987; Citation1993, Varker et al. Citation1990). He voted against locating the Mid-Carboniferous Boundary in the shallow water carbonates of Arrow Canyon, near Las Vegas, Nevada, USA, preferring instead the deep water mudstones of the bleak Yorkshire Pennines near Leeds. Arrow Canyon was chosen as the Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) for the Mid-Carboniferous Boundary, but this succession was subsequently shown to include at least one major hiatus (Barnett and Wright Citation2008).

9. Commission Internationale de Microflore du Paléozoïque (1969–2002)

Bernard thrived on most aspects of his job at IGS/BGS, and that included his tireless work for volunteer-run scientific societies. Of the several groups that Bernard was associated with, he probably worked more (and for longer) for the Commission Internationale de Microflore du Paléozoïque (International Commission of the Palaeozoic Microflora - CIMP) than any of the others. This society was established in 1958 at the Fourth International Congress of Carboniferous Stratigraphy and Geology in Heerlen, The Netherlands by the French palynologist Boris Alpern. It is an international federation of palynologists interested in Palaeozoic palynology, and CIMP organises working groups and regular symposia on this topic (Streel Citation2017).

The CIMP normally holds symposia at every International Congress of Carboniferous Stratigraphy and Geology, and Bernard presented or co-authored at least one paper at each of these events. He also attended all the intervening CIMP meetings. These included CIMP conferences at Liège, Belgium in 1969 and León, Spain in 1977. Bernard helped arrange many others such as the joint meeting with the American Association of Stratigraphic Palynologists (AASP) in Dublin, Ireland in 1982, and the North Sea ‘90 conference in Nottingham, UK in 1990.

Bernard was involved in the CIMP Working Group on Devonian palynology from the early 1960s onwards (e.g. Owens and Streel Citation1970, Owens and Richardson Citation1972). CIMP underwent a major reorganisation at its ninth meeting during the International Congress of Carboniferous Stratigraphy and Geology in Krefeld, Germany in 1971 and Bernard was elected as Co-ordinating Secretary of the various stratigraphical and fossil-group subcommissions. By this time, Bernard had become the hub of CIMP. He was already active in several CIMP Working Groups. These included the Working Group on Dictyotriletes, which reported to the CIMP symposium during the International Congress of Carboniferous Stratigraphy and Geology in Moscow, Russia in 1975, and the Working Group on Vallatisporites. During the Subcommission on Carboniferous Stratigraphy (SCCS) meeting in Kraków, Poland in 1995, Bernard proposed the establishment of a multidisciplinary Working Group on the definition of the Viséan–Namurian boundary (now Viséan–Serpukhovian) and its global equivalents. This was consistent with the then objectives of the SCCS in establishing a stage boundary close to this intra-Mississippian transition. This Working Group reported to the CIMP Meeting in Lille, France in 2002.

Bernard was elected to the position of General Secretary of CIMP in 1978, and held this post until 1983. One of his duties was the production of the CIMP Newsletter; a major task prior to the digital revolution. When Maurice Streel retired as President of CIMP in 1985, Bernard was elected in his place. He served as President until 1991, and was re-elected for the period 1998 to 2002.

10. International CIMP collaborations (1980 onwards)

Under the aegis of CIMP, Bernard organised several major collaborative international projects on Palaeozoic and Mesozoic palynology. The first of these was represented by the several CIMP-sponsored sessions which formed part of the Fifth International Palynological Conference held at the University of Cambridge, UK in 1980. The resultant publication was co-edited by Bernard in a special volume of Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology (Owens and Visscher Citation1981). Throughout the early 1980s, he was instrumental in instigating and managing a large collaborative research project between palynologists in CIMP, the University of Garyounis in Benghazi, Libya and the Arabian Gulf Oil Company (AGOCO) to study the Cambrian to Cretaceous subsurface palynostratigraphy of the Cyrenaica region of northeast Libya. The inclusion of AGOCO was vital, not only because they provided operating funds, but also because they allowed access to superbly preserved borehole material. Preliminary results were presented in a special part of the Journal of Micropalaeontology co-edited by Bernard (Thusu and Owens et al. Citation1985) with more detail published later in a special volume published by Garyounis University (El-Arnauti et al. Citation1988). Again, Bernard acted as editor. In these volumes he is credited as a scientific advisor to the project, but his role was actually much more fundamental and wide-ranging.

Most of the biostratigraphical interpretations for northeast Libya in El-Arnauti et al. (Citation1988) were achieved by long-distance correlations with northwest Europe. This situation highlighted a scarcity in palynological data in the intervening areas, largely the northwestern Middle East and southern Europe. The CIMP International Symposium on Circum-Mediterranean Palynology held in Zeist, The Netherlands in 1988 was an attempt to begin to fill this gap in knowledge. Again, Bernard edited the symposium volume published in a special volume of Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology (Owens and Visscher Citation1990).

Having established the model, Bernard then moved on to set up a similar collaboration between Saudi Aramco and CIMP to study the Palaeozoic palynostratigraphy of the Arabian Plate. This was instigated in 1990, and proved to be much longer running; the project continues to this day. The first results of this endeavour were presented at a CIMP symposium at the Eighth International Palynological Conference in Aix-en-Provence, France in 1992, with papers published in a special issue of Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology co-edited by Bernard (Owens et al. Citation1995). Subsequently, the Saudi Aramco sponsored session became a regular part of all CIMP meetings and at larger conferences where CIMP had a presence. Later results were presented at the CIMP General Meetings in Pisa, Italy in 1988, Lille in 2002, Prague, Czech Republic in 2006, Warsaw, Poland in 2010 and Bergen, Norway in 2015. Further presentations were given at CIMP symposia during the 10th International Palynological Conference in Nanjing, China in 2000, the 11th in Granada, Spain in 2004, the 12th in Bonn, Germany in 2008, the 13th in Tokyo, Japan in 2012 and the 14th in Salvador, Brazil in 2016.

Between the quadrennial International Palynological Conferences, there were Saudi Aramco sessions at other conferences in the intervening years. These were: CIMP Spore and Pollen Subcommission meetings (Cork, Ireland in 2001 and Lisbon, Portugal in 2007); European Palaeobotany and Palynology Congresses (Padua, Italy in 2014 and Dublin in 2018); and AASP-The Palynological Society (AASP-TPS) Annual Meetings (Kentucky, USA in 2012, San Francisco, USA in 2013, Nottingham in 2017 and Ghent, Belgium in 2019). Bernard continued to encourage publication of the results, and he was involved in co-editing three special volumes (Al-Hajri and Owens 2000; Paris et al. Citation2007; Wellman et al. Citation2015). Publication of the latest volume, which is to be dedicated in Bernard’s honour, is anticipated during 2020. The CIMP industrial cooperations stand out as highly significant contributions to the science of Palaeozoic palynology. As well as serving the operational needs of the funding companies, they also produced a coherent research group who continue to be able to access superbly preserved material and who have published six special volumes of papers, many dealing with alpha-taxonomy.

11. The Micropalaeontological Society (1970–1982)

Bernard was a great supporter of the The Micropalaeotological Society (TMS). This association was instigated in 1970, as the British Micropalaeontological Group (BMG), by Professor Leslie R. Moore (1912–2003) of the University of Sheffield in order to further the study of micropalaeontology (Spinner et al. Citation2004). Bernard was a founding member of this society, but more importantly, he became the first Secretary in 1970, serving in this position until 1975. During his stint as Secretary Bernard also acted as Treasurer between 1970 and 1972 before the Secretary-Treasurer position was separated. His fellow Darlingtonian Malcolm B. Hart took over the finances in 1972. During 1975 the BMG was renamed the British Micropalaeontological Society (BMS). Bernard became Chairman of the BMS in 1980 and served in this position for two years until 1982. There was a further name change, this time to The Micropalaeontological Society (TMS) in 2001, to reflect the increasingly international membership and profile.

The serial publication of TMS, Journal of Micropalaeontology, was launched during Bernard’s tenure as Chair in 1982. The inauguration of this journal remains by far the biggest decision ever made by the society, and Bernard was wholeheartedly in favour of it. Together with Ray Bate, Bernard worked hard on this project and persuaded Lesley Sheppard to be the first editor. Bernard was a co-editor of a special volume of the Journal of Micropalaeontology (Thusu and Owens et al. Citation1985). At the time of writing, the Journal of Micropalaeontology is in its 39th volume and, in 2018, became the first micropalaeontology journal to become 100% open access (https://www.journal-of-micropalaeontology.net/).

12. Awards and Honours

Like most of his colleagues at Sheffield and IGS/BGS, Bernard was an enthusiastic member of the Yorkshire Geological Society (YGS), which he joined in 1963. Bernard sat on the YGS council between 1983 and 1985. He later acted as honorary auditor for this society, and co-authored six papers in the Proceedings of the Yorkshire Geological Society between 1977 and 2018 (Appendix 2 of the Supplemental Data). In 1998 Bernard was awarded the John Phillips Medal by YGS. This is the highest award given by the society, and is given to geologists who have made distinguished contributions to the stratigraphy and palaeontology of the north of England. The specific citation for Bernard stressed his ‘distinguished contributions to the understanding, correlation and classification of the Upper Palaeozoic rocks, work that started in the north of England but now extends beyond the boundaries of Europe’.

Bernard’s distinguished contributions to palynology were recognised by AASP-TPS by the award of Honorary Membership at the 44th Annual Meeting in Southampton, England in 2011 (Anonymous Citation2011). The citation for this award mentions ‘his life-long commitment to the Society and fostering the science of palynology worldwide, particularly his involvement in industry palynological activities in the Middle East and North Africa’. A special CIMP symposium on Palaeozoic palynology dedicated to Bernard was organised at this conference, with a Saudi Aramco-sponsored reception held in his honour.

Several colleagues have honoured Bernard by naming palynomorph species after him. These include the miospores Converrucosisporites owensii and Spelaeotriletes owensii named by Boris Alpern and Stanislas Loboziak in 1978, and Bob Ravn in 1991 respectively (Loboziak and Alpern Citation1978, Ravn Citation1991). Additionally, Ted Spinner established the megaspore Velumousspora owensii (see Spinner Citation1983.

13. Overview and later life

Bernard was a supreme facilitator, as evidenced by his management activities for IGS/BGS and at the University of Sheffield, together with his instigation and promotion of international collaborations. His stewardship of these major joint projects described in section 10, owed much to his personable manner and consummate skills as a mover and shaker. Bernard was very grounded, down to earth and refreshingly devoid of ego unlike many of his contemporaries. He also worked tirelessly for volunteer organisations, most notably CIMP. Bernard combined all this with a substantial scientific output. The latter included landmark publications on Devonian and Carboniferous palynostratigraphy and correlations, and somewhat more prosaic activities such as his single-grain picking and mounting. Like many of his generation he never fully embraced the digital revolution, especially in the early years.

This article makes abundantly clear that Bernard was absolutely dedicated to his career in geology. However, he was also devoted to his nearest and dearest and had a very happy and fulfilled family life (Appendix 1 of the Supplemental Data, Figures 5–7, 10–12). Bernard and Pat celebrated their Golden Wedding Anniversary in 2013 in the company of family and friends. He was a loyal and devoted father and supported Graham and Kathryn’s childhood extra-curricular activities. For example, he went along to Graham’s rugby matches throughout northern England, and provided much vocal encouragement from the touchline. Bernard always provided great council and support for all the big decisions that confronted his children as they grew into adulthood. Later, Bernard loved spending time with his two grandsons, Malachy and Ruairi Wallace.

As previously mentioned, Bernard never fully retired but he did reequilibrate work with family life, hobbies and holidays in later life. For example, after he retired from BGS he became a very active member of the Queen Ann Bowling Club, in The Park, Nottingham. Bernard helped with gardening at the club, providing many hand-reared plants from his greenhouse. He was able to spend more time in his garden, nurturing his beloved chrysanthemums and dahlias. Sadly, he developed Parkinson’s which affected him physically but absolutely not mentally. Despite his amazing resilience and spirit, Bernard succumbed to Parkinson’s-associated respiratory problems from which he died on 31st July 2019. His funeral was held in Keyworth on 20th August 2019.

In October 2019, the immediate Owens family met in the Yorkshire Dales and spread some of Bernard’s ashes over Grinton Moor, near Swaledale in North Yorkshire. This was an area that he loved, and knew intimately from his school and undergraduate studies. When Bernard was doing fieldwork in Swaledale as a student, he often slept rough in the old store buildings at Grinton Smelt Mill. This is the best preserved disused lead mine in the Yorkshire Dales and is located on Cogden Moor, south of the small village of Grinton. It operated throughout the 19th century, and closed in the late 1800s (Raistrick Citation1975). The area around Grinton Smelt Mill was a regular destination of the Owens family for walking and picnics. They last visited with Bernard in 2015 when he spent a very happy afternoon with his grandsons searching for baryte and galena specimens on the spoil heaps and in the stream bed of Cogden Gill.

Bernard Owens was a giant in the world of Palaeozoic palynology. His scientific efforts were many and varied, as well as being extremely impactful; he will be massively missed.

[email protected]

ORCID: 0000-0002-5529-8989

British Geological Survey, Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG, UK

Duncan McLean

MB Stratigraphy Limited, 11 Clement Street, Sheffield S9 5EA, UK

Charles H. Wellman

Department of Animal and Plant Sciences, University of Sheffield, Alfred Denny Building, Western Bank, Sheffield S1O 2TN, UK

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (52.1 MB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank the immediate Owens family, Pat, Graham and Kathryn, for their input to, and support of, this article. James B. Riding publishes with the approval of the Executive Director, British Geological Survey (NERC).

References

- Al-Hajri S, Owens B. editors. 2000. Stratigraphic palynology of the Palaeozoic of Saudi Arabia. Special GeoArabia Publication Vol. 1. Manama, Bahrain: Gulf PetroLink; 231p.

- Allen PM. 2003. A geological survey in transition. British Geological Survey Occasional Publication. 1:220p.

- Anonymous. 2011. Report on the 44th Annual Meeting, National Oceanography Center, Southampton, UK. AASP – The Palynological Society Newsletter. 44.4:16–18.

- Barnett AJ, Wright VP. 2008. A sedimentological and cyclostratigraphic evaluation of the completeness of the Mississippian–Pennsylvanian (Mid-Carboniferous) Global Stratotype Section and Point, Arrow Canyon, Nevada, USA. Journal of the Geological Society. 165(4):859–873.

- Calver MA, Owens B. 1977. Progress report of working group on proposed boundary-stratotypes for the Westphalian A, B and C. In: Holub VM, Wagner RH, editors. Symposium on Carboniferous Stratigraphy. The Geological Survey, Prague, Czechoslovakia; p. 65–68.

- Chaloner WG. 1958. The Carboniferous upland flora. Geological Magazine. 95(3):261–262.

- Clayton G, Coquel R, Doubinger J, Gueinn KJ, Loboziak S, Owens B, Streel M. 1977. Carboniferous miospores of western Europe: illustration and zonation. Mededelingen Rijks Geologische Dienst. 29:71.

- Clayton G, Manger WL, Owens B. 1998. Mississippian (Lower Carboniferous) miospores from the Cuyahoga and Logan formations of northeastern Ohio, USA. Journal of Micropalaeontology. 17(2):183–191.

- Doher LI. 1980. Palynomorph preparation procedures currently used in the paleontology and stratigraphy laboratories. U.S. Geological Survey. United States Geological Survey Circular. 830:29.

- Duane AM, Pirrie D. Riding JB. editors. 1992. Palynology of the James Ross Island area, Antarctic Peninsula. Antarctic Science. 4(3):257–368.

- Dunham KC. 1973. A recent deep borehole near Eyam in Derbyshire. Nature Physical Science. 241(108):84–85.

- El-Arnauti A, Owens B, Thusu B editors. 1988. Subsurface palynostratigraphy of northeast Libya. Benghazi, Libya: Garyounis University Publications; p. 275.

- Hart GF. 2008. Evolution and the future of Humanity: Homo sapiens’ galactic future. Boulder, CO: ScienceAnd Publishers; p. 293.

- Lane HR, Bouckaert J, Brenckle P, Einor OL, Havlena V, Higgins AC, Yang J-Z, Manger WL, Nassichuk W, Nemirovskaya T, et al. 1983. Proposal for an International Mid-Carboniferous Boundary. Compte Rendu, Dixième Congrès Internationale de Stratigraphie et de Géologie du Carbonifère, vol. 4. Madrid, Spain, 12th–17th Sept.; p. 323–339.

- Loboziak S, Alpern B. 1978. Le bassin houiller Viséen d’Agadès (Niger). III: Les Microspores. Palinología. Número Extraordinario. 1:55–67.

- McGregor DC. 1960. Devonian spores from Melville Island. Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Palaeontology. 3:26–44.

- McGregor DC. 1967. Composition and range of some Devonian spore assemblages of Canada. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 1(1–4):173–183.

- McGregor DC. 1979. Devonian miospores of North America. Palynology. 3(1):31–52.

- McGregor DC, Owens B. 1966. Illustrations of Canadian fossils. Devonian Spores of Eastern and Northern Canada. Geological Survey of Canada Paper. p. 66–30.

- McLean D, Riding JB, Wellman CH. 2020. Professor Bernard Owens (1938–2019). Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology.

- Neves R. 1958. Upper Carboniferous plant spore assemblages from the Gastrioceras subcrenatum horizon, north Staffordshire. Geological Magazine. 95(1):1–19.

- Neves R. 1961. Namurian plant spores from the Southern Pennines, England. Palaeontology. 4:247–279.

- Neves R, Owens B. 1966. Some Namurian camerate miospores from the English Pennines. Pollen et Spores. 8:337–360.

- Owens B. 1959. The Yoredale Series and chert deposits of Swaledale. Journal of the University of Sheffield Geological Society. 3:106–111.

- Owens B. 1970a. Recognition of the Devonian–Carboniferous boundary by palynological methods. Les Congres et Colloques de L’Université de Liège. 55:349–364.

- Owens B. 1970b. A review of the palynological methods employed in the correlation of Palaeozoic sediments. (Contributions to the Third C.I.M.P. Meeting on Palaeozoic Stratigraphy). Les Congres et Colloques de L’Université de Liège. 55:99–112.

- Owens B. 1971. Miospores from the Middle and Early Upper Devonian rocks of the Western Queen Elizabeth Islands, Arctic Archipelago. Geological Survey of Canada Paper. 157:70–38.

- Owens B. 1973. Contribution on palaeontology. In: Smith EG, Rhys GH, Goossens RF, editors. Geology of the country around East Retford, Worksop and Gainsborough. Memoirs of the Geological Survey of Great Britain (England and Wales). London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, p. 348.

- Owens B. 1980. Micropalaeontology - The IGS approach. The British Geologist. 6:111–113.

- Owens B. 1981. Palynology, its biostratigraphic and environmental potential. In: Illing LV, Hobson GD, editors. Petroleum Geology of the Continental Shelf of North-West Europe. London: Institute of Petroleum; p. 162–168.

- Owens B. 1982. Palynological zonation of mid-Namurian strata in northern England. In: Rambsottom WHC, Saunders WB, Owens B, editors. Biostratigraphic data for a Mid-Carboniferous boundary. IUGS Subcommission on Carboniferous Stratigraphy, Biennial Meeting, Leeds, UK, 1981; p. 22–26.

- Owens B, Burgess IC. 1965. The stratigraphy and palynology of the Upper Carboniferous outlier of Stainmore, Westmorland. Bulletin of the Geological Survey of Great Britain. 23:17–44.

- Owens B, Streel M. 1967. Hymenozonotriletes lepidophytus Kedo, its distribution and significance in relation to the Devonian–Carboniferous boundary. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 1(1-4):141–150.

- Owens B, Streel M. 1970. Palynology of the Devonian–Carboniferous boundary. Report on Project B of the Third C.I.M.P. Meeting on Palaeozoic Stratigraphy. Les Congres et Colloques de l’Université de Liège. 55:113–120.

- Owens B, Richardson JB. 1972. Some recent advances in Devonian palynology – a review, Report of C.I.M.P. Working Group No. 13B. Compte Rendu, Septième Congrès Internationale de Stratigraphie et de Géologie du Carbonifère Vol. 1. Krefeld, Germany, 23rd to 28th August 1971.; p. 325–343.

- Owens B, Visscher H. editors. 1981. Late Palaeozoic and Early Mesozoic stratigraphic palynology. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 34(1):135.

- Owens B, Visscher H. editors.1990. Circum-Mediterranean palynology. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 66:167–377.

- Owens B, Mishell DRF, Marshall J. 1976. Kraeuselisporites from the Namurian of northern England. Pollen et Spores. 18:145–156.

- Owens B, Neves R, Gueinn KJ, Mishell DRF, Sabry H, Williams JE. 1977. Palynological division of the Namurian of northern England and Scotland. Proceedings of the Yorkshire Geological Society. 41(3):381–398.

- Owens B, Loboziak S, Teteriuk VK. 1978. Palynological subdivision of the Dinantian to Westphalian deposits of northwest Europe and the Donetz Basin of the U.S.S.R. Palynology. 2(1):69–91.

- Owens B, Riley NJ, Calver MA. 1985. Boundary stratotypes and new stage names for the Lower and Middle Westphalian sequences in Britain. Compte Rendu, Dixième Congrès Internationale de Stratigraphie et de Géologie du Carbonifère Vol. 4. Madrid, Spain, 12th–17th September 1983; p. 461–472.

- Owens B, Varker WJ, Hughes RA. 1990. Lateral biostratigraphical consistency across the Mid-Carboniferous boundary in northern England. Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg. 130:237–244.

- Owens B, Al-Tayyar H, Van der Eem JGLA, Al-Hajri S editors. 1995. Palaeozoic palynostratigraphy of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 89:150.

- Owens B, Romano M, Wellman CH, Riding JB. 2019. Obituary. Edwin George (‘Ted’) Spinner (1938–2018). Palynology. 43:184–187.

- Paris F, Owens B, Miller MA editors. 2007. Palaeozoic Palynology of the Arabian Plate and Adjacent Areas. Revue de Micropaléontologie. 50(1):144.

- Paul D. 2012. Eyam: Plague Village. UK: Amberley Publishing; 160p.

- Podgainaya NN, Loboziak S, Owens B. 1996. Assemblages of Middle and Upper Carboniferous zonal miospores from the south-western Precaspian Depression, Russia. Bulletin Des Centres de Recherches Exploration-Production Elf-Aquitaine. 20:91–129.

- Raistrick A. 1975. The Lead Industry of Wensleydale and Swaledale. In: Volume I. The Mines. Buxton, UK: Moorland Publishing Company; 83p.

- Ramsbottom W. 1981. Field Guide to the Boundary Stratotypes of the Carboniferous Stages in Britain. Biennial Meeting of the Subcommission of Carboniferous Stratigraphy, Leeds, UK, August 25th–September 1 1981, 115p.

- Rambsottom WHC, Saunders WB, Owens B editors. 1982. Biostratigraphic data for a Mid-Carboniferous boundary. IUGS Subcommission on Carboniferous Stratigraphy, Biennial Meeting, Leeds, UK (1981), 156p.

- Ravn RL. 1991. Miospores of the Kekiktuk Formation (Lower Carboniferous), Endicott Field Area, Alaska North Slope. American Association of Stratigraphic Palynologists Contributions Series 27:173.

- Riding JB, Woollam R. 1982. British Jurassic dinoflagellate cysts. Institute of Geological Sciences Biostratigraphic Package. Institute of Geological Sciences, Leeds, UK. Nine volumes, 612p, 350 plates (unpublished).

- Riding JB, Kyffin-Hughes JE, Owens B. 2007. An effective palynological preparation procedure using hydrogen peroxide. Palynology. 31(1):19–36.

- Riding JB, Scott AC, Collinson ME. 2020. A biography and obituary of William G. Chaloner FRS (1928–2016). Palynology. 44(1):127–166.

- Riley NJ, Razzo MJ, Owens B. 1985. A new boundary stratotype section for the Bolsovian (Westphalian C) in northern England. Compte Rendu, Dixième Congrès Internationale de Stratigraphie et de Géologie du Carbonifère vol. 1, Madrid, Spain, 12th–17th September 1983;p. 35–44.

- Riley NJ, Varker WJ, Owens B, Higgins AC, Ramsbottom WHC. 1987. Stonehead Beck, Cowling, North Yorkshire, England: a British proposal for the Mid-Carboniferous boundary stratotype. Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg. 98:159–177.

- Riley NJ, Claoué-Long J, Higgins AC, Owens B, Spears A, Taylor L, Varker WJ. 1993. Geochronometry and geochemistry of the European mid-Carboniferous boundary global stratotype proposal, Stonehead Beck, North Yorkshire, UK. Annales de la Société Géologique de Belgique. 116:275–289.

- Sarjeant W. 1984. Charles Downie and the early days of palynological research at the University of Sheffield. Journal of Micropalaeontology. 3(2):1–6.

- Spinner E. 1983. Velumousspora, a megaspore genus from the Namurian of northern England. Journal of Micropalaeontology. 2(1):67–70.

- Spinner EG. 1986. Sheffield’s worldwide palynologists. Journal of the University of Sheffield Geological Society. 8:222–227.

- Spinner E, Owens B, Lunn P. 2004. Obituary. Professor Leslie Rowsell Moore 1912–2003. Journal of Micropalaeontology. 23(1):1–2.

- Stephenson MH, Owens B. 2006. Taxonomy Online 2: The ‘Bernard Owens Collection’ of single grain mount palynological slides: Carboniferous spores part I. British Geological Survey Research Report RR/06/05; 80p.

- Streel M. 2017. The origin of CIMP or how to increase international contacts between Paleozoic palynologists during the second part of last century. CIMP Newsletter. 86:21–22.

- Summers A. 2013. Not in your lifetime: the assassination of JFK. London, UK: Headline Publishing Group, 656p.

- Thusu B, Owens B editors. 1985. Palynostratigraphy of north-east Libya. Journal of Micropalaeontology. 4(1):182.[Mismatch

- Varker WJ, Owens B, Riley NJ. 1990. Integrated biostratigraphy for the proposed Mid-Carboniferous boundary, Stonehead Beck, Cowling, North Yorkshire, England. Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg. 130:221–235.

- Wadge AJ, Owens B, Downie C. 1967. Microfossils from the Skiddaw Group. Geological Magazine. 104(5):506–507.

- Wellman CH. 2005. Half a century of palynology at the University of Sheffield. In: Bowden AJ, Burek CV, Wilding R. editors. History of Palaeobotany: Selected Essays. Vol. 241. London: Geological Society London Special Publications. p. 259–279.

- Wellman CH, Breuer P, Miller MA, Owens B, Al-Hajri S. editors. 2015. Palaeozoic palynostratigraphy of the Arabian plate [a joint project between Saudi Aramco and the Commission Internationale de Microflore du Paléozoïque (CIMP)]. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 212:1–2.