ABSTRACT

HenPower is a programme that enables older people who live with dementia in care homes to take part in hen-keeping and hen-related creative activities. It was introduced into UK care homes to address evidence suggesting older adults who live with dementia in care homes can experience diminished personal wellbeing. This study aimed to 1) assess the impact of HenPower on people who have dementia who are living in a care home and 2) explore care home staff views and experiences of the HenPower programme. A nested qualitative design was adopted, utilizing observation of 29 older people who live in a care home and 25 staff individual and small-group interviews. Five themes emerged: ongoing meaningful engagement with hens, self-expression through creative activities, improved mood and participation, improved social interaction, and enhanced living environment. HenPower offers potential wellbeing benefits to older people living in care homes, many of which echo with existing evidence on non-pharmacological approaches.

Introduction

Pharmacological approaches to manage behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia are available, yet many offer side effects and limited efficacy. This suggests the importance of non-pharmacological approaches (Zucchella et al., Citation2018). Such approaches include a variety of techniques, including music (Ueda et al., Citation2013), physical exercise (Forbes et al., Citation2015), and reminiscence (Woods et al., Citation2005) therapy. They also often focus on improved management of behavioral problems (Dyer et al., Citation2018). Within such approaches, methods which have used creative arts (Dunphy et al., Citation2019), or the process of art making to help improve wellbeing, and animal-assisted approaches (Yakimicki et al., Citation2019), or the use of animals or pets to help improving wellbeing, have been found to offer a range of positive impacts. These include impacts on social behaviors, physical activity, dietary intake and relationships with carers. They are also seen as supporting a range of approaches which help combat negative stereotypes of aging and encourage positive aging (Yamamoto, Citation2021).

However, as the evidence base on non-pharmacological approaches to enhancing wellbeing in people experiencing changing cognitive abilities develops, it highlights a number of concerns. While recent systematic reviews (Emblad & Mukaetova-Ladinska, Citation2021; Shoesmith et al., Citation2020) reinforce the benefits of such approaches, they also illustrate methodological concerns over small sample sizes and limited study design, along with variability in requirements for success (such as session content, artistic ability, and the role of the facilitator). Similar concerns have been found in literature on animal-assisted approaches, where evidence highlighting the positive impacts (such as reduced loneliness) is limited again by methodological concerns (Batubara, Tonapa, Saragih, Mulyadi, & Lee, Citation2022; Brimelow & Wollin, Citation2017; Javaid, Citation2021) and variability in approaches (such as characteristics of the species and affordability concerns) (Ebener & Oh, Citation2017).

Although precise data are not available, it is felt that a large proportion of the UK’s care home population are likely to experience dementia (Care Quality Commission, Citation2010), with Alzheimer’s Society estimating that 70% of older people living in care homes will be experiencing the condition (Thraves, Citation2016). Meanwhile 53% of those who die with dementia do so in long-term care institutions (Sleeman et al., Citation2014). This clearly places a significant demand on such care homes, as they are required to manage the complex health, social and psychological needs of the people who reside there for long periods of time (Davies et al., Citation2014). In fact, the regulatory framework for such services both draws attention to the requirement for care homes to be stimulating environments, and also to be settings where staff assess the needs and aspirations of people who reside there, while also providing support for them to engage in a range of meaningful activities (Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE), Citation2006; National Institute of Clinical Excellence, Citation2013). Non-pharmacological approaches offer one possibility of creating such environments, and the resultant positive impacts for older people who live in a care home.

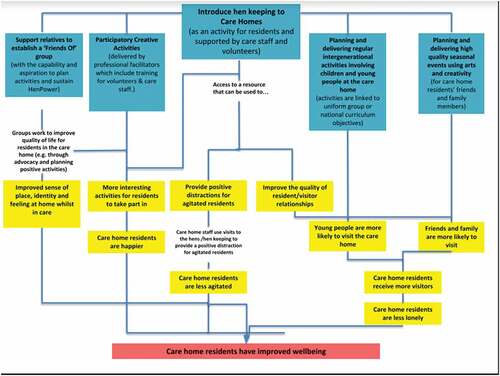

One such approach is the use of HenPower, which was established in 2012 by Equal Arts (Ludlow, Citation2016) and is underpinned by the theory of change modle illustrated in . This programme enables older people to take part in hen-keeping and hen-related creative activities, led by a trained artist, in the communities where they live. Since the launch of the programme in Northeast England, HenPower has been implemented across the UK (Cook, Cook, Thynne, & Chandler, Citation2013), and in Taiwan and Australia, particularly in care home services, with growing evidence suggesting positive impacts such as reducing stress and promoting calm (Spanswick, Citation2015). Older people are involved in the programme in two ways: as volunteers or programme participants. Older volunteers take a leading role in introducing HenPower to older people’s care settings, schools and universities, while all people residing in participating homes are invited to take part in hen-keeping and a range of hen-related arts activities. Thus, the HenPower programme offers a range of creative arts and animal-assisted approaches with the goal of improving wellbeing, particularly for participants with dementia. Little is known of the experience of HenPower in care home settings. Hence a theory of change model, presented in figure one, was developed by the programme managers. They proposed that the introduction of HenPower in a care home may imact older people who live in a care home’s personal wellbeing through different causal routes.

Figure 1. Theory of change highlighting changes that occur in a care home following the introduction of HenPower in a care home.

The potential influences on wellbeing presented in the theory of change model for HenPower informed the aims of the evaluation study. This paper represents the findings of a nested qualitative study within a broader mixed methods evaluation which aimed to 1) assess the impact of HenPower on people living with dementia in care homes and 2) explore care home staff views and experiences of HenPower on older people who live in a care home’s personal wellbeing.

Materials and methods

This article presents a nested qualitative study comprised of observations of care home residents and interviews with staff members, taken from the larger convergent parallel mixed method evaluation (Creswell & Plano-Clark, Citation2011) adopted to address the study’s overall aims. As aim one assessed impacts on people living with dementia, this was challenging due to the effect of dementia on an individual’s ability to discuss their experiences. Thus, the use of semi-structured and structured interviews could be limited as these approaches to data collection rely on abstraction, recall, and verbal reporting. Hence, observation and quantitative methods were selected to capture older people who live in a care home’s engagement with, and outcomes from, the HenPower programme. These included measurement of quality of life utilizing the Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit (ASCOT) CH3 tool, social contact data and agitation measures using the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI). However, this data is not included here due its incomplete nature following the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions in care homes.

Older people who live in a care home’s observations

Unstructured, non-participant observations were carried out over a two-hour period featuring a meal by researchers on participants as part of the ASCOT (CH3) (www.pssru.ac.uk/ascot) assessment. Observations focused on eight domains of personal cleanliness and comfort, accommodation cleanliness and comfort, food and drink, feeling safe, social participation, occupation, control over daily life and dignity. Data were recorded via fieldnotes. On reflection, the non-participant observation data provided an opportunity to note the participants spontaneously passing, noticing and commenting on the hens in their home, or using them as a focal point for their creative activities.

Staff interviews

Aim two was addressed through analysis of data generated through interviews with care home staff. Care home staff were invited to participate in semi-structured individual or small group interviews. Semi-structured interviews provided the opportunity for participants to describe experiences and views of HenPower, including the impact of this programme on older people who live in a care home. The different methods of interview enabled staff to participate whilst ensuring that sufficient staff were available to maintain care in the home.

Participants and sample sites

Care home sample

The recruitment of care homes occurred between December 2018 and September 2019. Care homes were selected based on the following criteria:

Agreement from care home managers that the care home will engage with the HenPower programme in the next two months.

The hens were not onsite at the time of baseline data collection.

The care home provided residential or nursing care for people with dementia.

Eight care homes were approached with six homes agreeing to participate in the study; two located in London and four in Northeast England. Attrition of one home occurred prior to baseline data collection and another during data collection. Reasons for attrition included delays implementing the HenPower programme and the lack of arrival of the hens by data collection. This resulted in four care homes being included in the study:

CH1: privately-owned care home in Northeast of England, with service specification for residential and residential dementia care, for 47 people in 43 rooms.

CH2: privately-owned care home in Northeast of England, with service specification for residential and residential dementia care, for 35 people.

CH3: privately-owned and provides care for residential and nursing needs for up to 64 young and older people with learning disabilities, physical disabilities and dementia in London.

CH4: privately-owned site based in London, offering care for up to 150 people experiencing mental and psychical conditions, including dementia.

Sample

A sample of older people who live in a care home were recruited if they resided at a site where the HenPower programme was implemented, were able to engage in HenPower activities and consent or have assent provided by their surrogate decision maker, in accordance with the Mental Capacity Act (2005). Potential participants were excluded if receiving palliative care or likely to experience distress by visitors to the care home.

34 older people who live in care homes were recruited to the study, of which 26 were female and 8 were male. Attrition occurred of 5 people due to no exposure to HenPower during data collection. Analysis was based on data from 29 participants.

A full breakdown of participants is included in .

Table 1. Participant breakdown

Staff sample

25 staff members completed 20 individual and 2 small-group interviews. Due to the quarantine requirements of the COVID-19 pandemic, one telephone interview was completed with the interviewer noting key discussion points. All other interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

In keeping with Mulhall (Citation2003), analysis of observation data began with simultaneous, subconscious analysis during fieldwork with the decision of what significant information to record. This was then supplemented by additional analysis where observations were grouped under the targeted domains for assessment.

Staff individual and group interviews were analyzed using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, Citation2006). Interview transcripts were independently coded by two team members (GC and HAB), using open coding, before codes were generated into themes. Final themes were presented at a data clinic with the full research team to ensure accuracy. The analysis was inductive, i.e. driven by data rather than theory.

Following analysis of the individual data sets, the findings were compared for similarities and differences. This enabled confirmation and expansion of themes, and identification of rich examples of the impact of the HenPower programme.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for this evaluation study was obtained from Northumbria University ethics committee (1.2.2019) and the Social Care Research Ethics Committee (13.2.2019). As the study involved people with moderate to severe dementia, the Mental Capacity Act (2005) was applied. Some older people with dementia could lack the ability to recall and understand information about the study, in which case personal and nominated consultees provided assent for study participation. Participants were able to withdraw at any point of data collection or if their condition deteriorated.

The person’s dignity and privacy were prioritized over data collection. Observations were not completed during personal care, when bedroom doors were closed or during private interactions between older people who live in a care home and staff. Data collection also ceased when older people who live in a care home appeared agitated or distressed with the presence of a researcher.

Results

Observation and staff interview data provided rich insights into the influence of the HenPower programme on older people who live in a care home. The following five themes provide a descriptive interpretation of these experiences: ongoing meaningful engagement with hens, self-expression through creative activities, improved mood and participation, improved social interaction, and enhanced living environment.

Ongoing meaningful engagement with hens

Staff participants drew attention to the way that some participants took a keen interest in the hens:

When she sits out, facing the chickens, she’s talking … She says, “Eh, look what they’re doing now.” And she talks about them. “Eh, look - can you see that? Can you see her coming out?” She’ll talk about the chickens like this to the other residents that are sitting with her. So, she starts the conversation. (CH1)

This carer commented how this older person who lived in a care home was fascinated by the hen’s actions and wanted to engage others in observing them. She was particularly interested in one hen. Other older people who live in a care home also demonstrated preference for certain hens, being attracted by features such as behavior, color, size and breed.

For some older people who live in a care home hen-keeping became an inherent aspect of daily life. Older people who live in a care home were observed taking part in hen-keeping by opening the henhouse in the morning, cleaning or feeding the hens. These activities provided an opportunity for older people who live in a care home to fulfil a meaningful role.

On a night-time he says “Oh, make sure the chickens are locked in.” He’ll not join in activities. But if I say to him “Oh, come and give me a hand to clean them up” he’ll come and he will clean them out. I would say the majority of residents try and do their best. It’s just a good thing for them. Interestingly, the ones that you wouldn’t think would hold the chickens – and they do. It’s great. Their eyes light up and their faces change. (CH2)

Others were observed to be less engaged in hen-keeping activities, and were more focused on petting the hens.

They get involved. Like, when they’re talking about the names of the chickens. And then telling them a story, and they’re interacting with the story. They like cuddling the hens and they might sing a song about the hens. (CH3)

Some residents don’t go outside, or leave their bedrooms. I’ve got one resident that does like me to bring the hen into her room. I bring a different one each time, and the hen sits on her table and she has a bit chat with it. She talks to it, talks about its eyes and stuff like that. (CH1)

HenPower provides both opportunities for group and one-to-one activities, which are evident in the above extracts. These individuals interact with other older people who live in a care home, the activities co-ordinator and the hens. Hence there is active engagement in individualized ways. Whilst many older people who live in a care home demonstrated curiosity about the hens, there were some that were reticent about touching them:

We used to have a lady who was quite down. When we first got them, she asked “Can you take me to the window? Can I go and have a look at them?” So, she would look at them through the window, and then I asked “Well, do you want me to fetch one in?” “Oh, no, no – I just want to look at them.” But then, after a week, “Go on, then – open the door and let one come in.” So, it was just baby steps. And then, at the finish, she’s, “Come on, then, go and get the chicken.” And she’s got a towel on her knee. “Give me it here.” And it sits on her knee. (CH2)

Self-expression through creative activities

The hens were a focal point of the HenPower programme, and were frequently described as “our hens” or part of “our family.” For some older people who live in a care home and staff, hen-keeping became an inherent aspect of daily life. These activities provided an opportunity to fulfil a meaningful role. Other older people who live in a care home adopted roles such as gift-maker for the hens, which provided a sense of purpose:

She’ll draw pictures, and it’s always about … It’s always a chicken. Her and a chicken, she’ll draw a picture of it. Then she comes down and she sticks them with BluTack onto the fence, where the chickens are. Giving them the pictures. Everything she does is for the chickens. The same as all the rest of them (other residents). But she does it differently. She likes to make them things. CH1)

Some older people who live in a care home took part in the building of the henhouse as an opportunity to use skills they had acquired throughout life:

Well, all of the men, particularly, had a go with the drill. They just wanted to keep going. They wanted to continue to build the house. The men just loved it. And, like I say, [Name] can barely stand up most days, and he was there with this drill. And it helped to get him focused. (CH2)

The creative activity aspect of the HenPower progamme was viewed as important. Older people who live in a care home were involved in designing and making henhouses, singing about hens, painting, and ceramics, and poetry, amongst other activities. These provided opportunities for older people of all abilities to participate, hence the programme was inclusive:

They get involved. Like, when the lady sits down and they’re talking about the names of the chickens. And then telling them a story, and they’re interacting with the story. They might sing a song about the hens. (CH3)

The observation sessions provided insight into the way that having a range of activities ensured that the diverse community of older people could use their various talents and skills. One carer described how she used her knowledge that one older person who lived in the care home had been a painter and decorator to encourage him to take part in an activity:

I said to him, “You used to be a painter and decorator - hold this paintbrush for me. Because you should be showing me how to do this and not the other way” … We had the music on, and then there were just a few brush strokes on a piece of paper to anybody else, but to me it was a masterpiece. He usually wouldn’t do anything. We’re having to assist him with his meals and he can’t walk anymore since he fractured his hip. But as soon as I said, “Come on, you need to show me what colours go where.” He was away. (CH2)

Whilst there is intrinsic value in doing something pleasurable, the staff participants highlighted the importance of older people who live in a care home having opportunities for self-expression and experiencing fulfillment in producing quality outcomes:

It’s been nice to have different materials for residents to work with. You know, they have produced some fantastic work. There’s quite a lot of them point out that “I did that.” Which has been really nice, it’s the ownership that they’ve got over something they produce which has been really good. (CH2)

Here, these older people who live in a care home were able to point to something that they had created, which transformed their cared-for experience to a life experience. They were able to share their artwork with relatives and take pride in their achievements.

Improved mood and participation

Staff observed the older people who live in a care home’s enjoyment when they were with the hens: they had “a spark,” “their eyes light up,” “they had a spring in their step” and “came back to life.” The following carer retold a story of a discussion she had had with a daughter who attributed the positive changes that she had observed in her mother’s demeanor to the presence of hens.

But the meaning it gives her, to her life, where she can actually smile. She can actually laugh, and her daughter, you know, said, “Thank you very much. You’ve done something that nobody else has done. You’ve made mum laugh. She’s seeing you lot running around and chasing the hens.” And it’s just brought something positive to her. And it was really nice. You know, out of a situation, something positive comes about it. She loves watching the hens. She sits by the window and watches them all day. (CH3)

Those that showed interest in the hens demonstrated their pleasure by smiling, pointing and talking about what the hens were doing. The hens appeared to have a calming effect on some individuals and provided a therapeutic distraction in times of heightened agitation.

They enjoy touching, stroking and feeling the animals. It relieves the tension and stress. It can be calming. It’s surprising what a difference it makes – when someone is distressed or agitated it helps to calm them. (CH4)

It was observed that older people who live in a care home who walked around the home appeared to purposefully pass by the henhouse and stop to watch with interest. One housekeeper was observed interacting with a male person living in the home when he was distressed by directing him to the henhouse. His behavior changed and he stopped to calmly watch the hens. The staff participants indicated that the hens were a positive facilitator of improved mood, and stated they had witnessed positive changes in social behavior within the care home community:

It’s to see their faces. Honestly. It’s unbelievable. I know when any dogs or anything comes in the home - you know, if any of the residents’ families bring dogs or anything in, they go wild. The chickens have even been more of a high – smiles and so much laughter. (CH3)

Improved social interaction

Previous quotations highlight how staff and older people who live in a care home interact with each other in fulfilling hen-keeping activities. People living in the homes were observed talking to each other about the hens. Staff participants also drew attention to the way the hens provided a conversation starter between people living there:

It’s like it’s part of the family and they’re … It’s a big conversation starter as well. Like, when the first egg was laid, it was like, “Whoah … ” It was like the crown jewels. [Name] was walking around and showing everybody … (CH1)

The hens provided a focus for individuals and a point of mutual interest. Hence it was suggested that having hens in the care home facilitated social interaction and, through increased interaction between older people who live in a care home, created opportunities for building social relationships. This was considered to be important for older people moving to the home.

A positive moment for me was when two female residents were sitting and chatting and I heard them say ‘lovely chicken, I love you.’ It was wonderful to hear. They had just moved into the home and they didn’t know each other. They made a connection together with this hen and that was the start of their friendship. It was wonderful. (CH4)

Others noted that staff interaction with people living there also changed. There was more spontaneous social discussion, rather than the focus being largely on the tasks of care.

The interaction is the most, now … Because they did help everyone to interact more. You know. I think it’s good how the interaction within the home has changed. (CH3)

There were other discussions that suggest that interaction with visitors also improved. The hens were of interest to young and old, hence older people who live in a care home now had pets that they could show their younger visitors. This provided something meaningful for older people who live in a care home to do with others. This manager commented:

It’s made a big difference to when grandchildren visit. They take their grandma to see the hens. When they come into the home they ask to go and see the hens. The kids love going to the chickens and picking up the eggs. It is something to do in the outdoors of the home. (CH4)

One of our residents – he had his grandchildren over. And they loved it. They thought it was great. It was like, “Granddad has got chickens!” It was really sweet, it’s lovely. (CH3)

Enhanced living environment

During the preparation for the arrival of hens there was much planning of where the henhouse would be positioned and what the henhouse could look like. Staff interviewees highlighted that this led to increased interest in the outdoor space of the care home. Changing the garden to accommodate the henhouse became a catalyst for a programme of development in the outdoor space of some care homes:

And, again, the chickens being here has made us think about how we use the outside areas. So, for example, we’ve got three separate seating areas, just outside here. During the summer, we turned it into a bit of a coffee shop. That previously wasn’t that. It was just a seating area where people went and had a cigarette. It’s now become much more … … an area where people can sit and relax and enjoy. (CH1)

Older people who live in a care home were observed walking in the fresh air with their visitors. The hens being present in their garden meant they had something of interest to show grandchildren and other visitors:

When people bring the grandchildren in, they tend to take them outside to see the hens now. We’ve even got a relative’s family who bring their dog and the dog has to go out and see the hens. (CH1)

Whilst these stories are positive reflections on the HenPower experience, staff also highlighted that the introduction of the programme to a care home necessitated consideration of safety issues:

That’s one of the things that we’re having to look at. Is the safety. So, we are looking at maybe taking the box away and making it a bigger area. And then having a nice seating area, so the residents can watch the hens more. We have them here at the windows, so they can watch them from in and out. (CH1)

In those homes where the henhouse was located in an area visible from the public lounge or people’s rooms, participants argued that this brought the outdoors, indoors. Staff suggested that this enabled older people who live in a care home to have a connection with nature and enjoy a feeling of being outdoors. Their observation of the positive experience of being outdoors and in touch with nature led one care team to consider ways that they could improve the internal environment of the care home, particularly for people who were unable or did not want to go outside:

We’ve definitely brought the outside in. We have an area upstairs where, at the moment, it is a seating area. We’re going to try and turn that area into a bit more of a sensory area. And the reason we’ve chosen that area is specifically for those residents who do not want to come downstairs. Or do not want to go outside. So we’re going to create an inside garden, in this little area. We’ve chosen that area so they can look over into the chickens. So, they will see directly where the chickens are. And hopefully that will have some long-term lasting impact on wellbeing. (CH1)

This staff team was motivated to use a variety of spaces for older people who live in a care home to connect with nature by simply enjoying the feeling of being outdoors in an indoor environment. Having HenPower in this care home was viewed as enhancing care provided in the home through offering meaningful activities as well as stimulating improvements to both the internal and external environments.

Discussion

Wellbeing benefits of HenPower in care home settings

The findings of this paper () illustrate the many possible wellbeing advantages of the non-pharmacological approach, HenPower, within the care home setting, several of which echo the existing literature (Zucchella et al., Citation2018). Examples of this include the improvements found in engagement, behavior and mood in tailored activity programmes (Gitlin et al., Citation2017) and music approaches (Cheong et al., Citation2016; Daykin et al., Citation2018). It similarly reflects many of the benefits of animal-assisted methods with people with dementia, and evidence of Ritchie’s et al.’s (Citation2019) underpinning mechanisms of the human-animal bond, relationship dynamics and responsibility of caring, were all found to be in evidence. Not only did older people who live in a care home care for the hens and show engagement with hen-keeping, they also named them and expressed daily concern for their wellbeing. This was even seen to be the case for those who were usually isolated, disinterested or previously unable to engage in activities. This increased engagement saw the hens becoming a part of the home’s “family” and routine, whilst giving purpose and caring responsibility to the older people who live in a care home. This provides an ideal example of the desired meaningful activities identified as necessary in policy for care homes (Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE), Citation2006; National Institute of Clinical Excellence, Citation2013).

Table 2. Summary of key findings

Practice benefits of HenPower in care homes

Added value was also provided by the artist sessions which coincided with the arrival of HenPower. These activities have been seen to be beneficial elsewhere in the literature, with studies on visual arts and dementia finding benefits of improved quality of life (Windle et al., Citation2018) and communication (Bartlett, Citation2015). Here, it was particularly noticeable that older people who live in a care home both engaged with arts activities, and were often proud of their outputs. There was even evidence of people who had previously displayed little interest in activities, or an inability to take part, using their interest in the hens as a gateway to participation in the sessions. This again chimes with the literature, as all of the HenPower’s art activities were rooted in Shoesmith’s et al.’s (Citation2020) elements of effective visual arts practices for people with dementia. By focusing on the hens, the arts sessions became more engaging for the older people who live in a care home in that they were on a topic that was of interest to them and already part of their meaningful activities.

Similar benefits were found in the area of communication between older people who live in a care home and staff. It is unsurprising that this is a regularly occurring theme in the literature, with communication often cited as a chief concern of staff caring for people with dementia (Smythe et al., Citation2017). Similarly, improvements in older person-staff communication have been found to produce related benefits for people living in care homes (McGilton et al., Citation2017). Staff here reported that the activities surrounding the hens both improved mundane communication and also shone a light on previously unknown biographical information about the people living there. This provided two main benefits. The first is the relevance of hen-keeping to the older people who live in a care home, via their current interests and/or a biographical history of animal keeping. This allowed the staff to take a personhood approach to communication (Alsawy et al., Citation2017) by basing their conversations on topics that were of deep relevance to the individual involved. Secondly, it facilitated communication that was valued as spontaneous and “in-the-moment” by older people who live in a care home and care staff (Windle et al., Citation2020), thus making it more meaningful. As such, it provided further evidence of the important role staff can play in increasing opportunities for participation in meaningful activities (Ranada & Osterholm, Citation2022).

Organizational benefits of HenPower

The benefits also extended beyond the older person-staff interactions and were felt in the environment of the home. The benefits of a stimulating care home environment are widespread (Abbott, Mary, & Meyer, Citation2016; Cunningham, Citation2019). Gains here included improvements to indoor shared areas and also outdoor environments, which could potentially bring the benefits of increasing the older people who live in a care home’s connection to nature (Anderson, Citation2019; Evans et al., Citation2019). There were also wider benefits to the home environment, particularly the increased inter-generational engagement brought about by the introduction of the hens. Increased interest from family members, particularly grandchildren, could therefore indicate the advantages of inter-generational care for this population, such as the reduction in stigma (Department of Health, Citation2016) and increased sense of purpose and social contact (Galbraith et al., Citation2015).

Conclusion

Although these findings suggest positive outcomes, this study does include several limitations which may impact its relevance. Firstly, it must be acknowledged that this study was small and qualitative in nature, and further research on this topic using a variety of methodologies will be required for a full investigation. It thus reinforces the call elsewhere for future research on the subject to increase sample size and methodological rigor. Secondly, the authors acknowledge the importance of capturing the voice of those with dementia in research (Cottrell, Citation2008) and, although participants in this study were included via observations and discussions with staff who knew them well, more participatory research on this topic would be beneficial. Thirdly, the focus on the benefits of non-pharmacological approaches also does not mean they were used to replace existing antipsychotic treatment, the dangers of which have been outlined elsewhere (Ballard et al., Citation2017). Instead they were used alongside other treatments in the context of the homes. Finally, although the findings were largely positive, it is important to stop short of suggesting that HenPower had similar impacts on all members of the home. There are likely to have been other older people who live in a care home and staff who were less engaged with the approach, further reinforcing the importance of a toolkit approach to non-pharmacological methods which identify appropriate techniques to help each older person in an individual and personalized manner (Cohen-Mansfield, Citation2018).

Even with these limitations in mind, HenPower offers a range of benefits, including those associated with both animal-assisted and visual arts methods, for older people living in a care home, staff and care home organizations. Its employment suggests not only wellbeing benefits for those living in the homes, but also the improved communication between older people and care home staff and better use of the home environment. This adds to the growing literature suggesting positive impacts of such approaches. Further high-quality research is warranted to further investigate these impacts.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the participating homes and those living and working there for giving their time and engagement in the study. The authors would also like to acknowledge the involvement of Equal Arts staff and artists in recruiting and implementing HenPower in care home sits.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abbott, S., Mary, B., & Meyer, J. (2016). The impact of improved environment in a care home. The Journal of Dementia Care, 24(6), 23–25.

- Alsawy, S., Mansell, W., McEvoy, P., Tai, S. (2017). What is good communication for people living with dementia? A mixed-methods systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics, 29(11), 1785–1800. doi:10.1017/S1041610217001429

- Anderson, K. (2019). The virtual care farm: A preliminary evaluation of an innovative approach to addressing loneliness and building community through nature and technology. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 43(4), 334–344. doi:10.1080/01924788.2019.1581024

- Ballard, C., Orrell, M., YongZhong, S., Moniz-Cook, E., Stafford, J., Whittaker, R., Woods, B., Corbett, A., Garrod, L., Khan, Z., Woodward-Carlton, B. (2017). Impact of antipsychotic review and non‐pharmacological intervention on health‐related quality of life in people with dementia living in care homes: WHELD—a factorial cluster randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 32(10), 1094–1103. doi:10.1002/gps.4572

- Bartlett, R. (2015). Visualising dementia activism: Using the arts to communicate research findings. Qualitative Research, 15(6), 755–768. doi:10.1177/1468794114567493

- Batubara, S. O., Tonapa, S. I., Saragih, I. D., Mulyadi, M., & Lee, B. O. (2022). Effects of animal-assisted interventions for people with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Geriatric Nursing, 43, 26–37. doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2021.10.016

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brimelow, R., & Wollin, J. (2017). Loneliness in old age: Interventions to curb loneliness in long-term care facilities, activities. Adaptation & Aging, 41(4), 301–315. doi:10.1080/01924788.2017.1326766

- McGilton, K. S., Rochon, E., Sidani, S., Shaw, A., Ben-David, B.M., Saragosa, M., … Pichora-Fuller, M. K. (2017). Can we help care providers communicate more effectively with persons having dementia living in long-term care homes? American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias, 32(1), 41–50. doi:10.1177/1533317516680899

- Care Quality Commission. (2010). Guidance about compliance: Essential standards of quality and safety. http://www.cqcguidanceaboutcompliance.org.uk/.

- Cheong, C. Y., Tan, J.A.Q., Foong, Y.L., Koh, H.M., Chen, D.Z.Y., Tan, J.J.C., Ng, C.J., Yap, P. (2016). Creative music therapy in an acute care setting for older patients with delirium and dementia. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders Extra, 6(2), 268–275. doi:10.1159/000445883

- Cohen-Mansfield, J. (2018). Non-pharmacological interventions for persons with dementia: What are they and how should they be studied? International Psychogeriatrics, 30(3), 281–283. doi:10.1017/S104161021800039X

- Cook, G., Cook, M., Thynne, E., & Chandler, C. (2013). An evaluation of “HENPOWER:” Improving wellbeing and social capital in care settings. Final Report. Northumbria University.

- Cottrell, P. (2008). Exploring the value of service user involvement in data analysis: “Our interpretation is about what lies below the surface. Educational Action Research, 16(1), 5–17. doi:10.1080/09650790701833063

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

- Cunningham, J. (2019). Creating a stimulating home. Nursing And Residential Care, 21(8), 445–448. doi:10.12968/nrec.2019.21.8.445

- Davies, N., Maio, L., Vedavanam, K., Manthorpe, J., Vernooij‐Dassen, M., Iliffe, S. and IMPACT Research Team (2014). Barriers to the provision of high-quality palliative care for people with dementia in England: A qualitative study of professionals’ experiences. Health Social Care Community, 22(4), 386–394. doi:10.1111/hsc.12094

- Daykin, N. Parry, B., Ball, K., Walters, D., Henry, A., Platten, B. & Hayden, R (2018). The role of participatory music making in supporting people with dementia in hospital environments. Dementia, 17(6), 686–701. doi:10.1177/1471301217739722

- Department of Health. (2016). Prime Minister’s challenge on dementia 2020: Implementation plan. Retrieved from: www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/215101/dh_133176.pdf

- Dunphy, K. Baker, F.A., Dumaresq, E., Carroll-Haskins, K., Eickholt, J., Ercole, M., … Wosch, T. (2019). Creative arts interventions to address depression in older adults: A systematic review of outcomes, processes, and mechanisms. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2655. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02655

- Dyer, S. Harrison, S.L., Laver, K., Whitehead, C. &Crotty, M. (2018). An overview of systematic reviews of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 30(3), 295–309. doi:10.1017/S1041610217002344

- Ebener, J., & Oh, H. (2017). A review of animal-assisted interventions in long-term care facilities, activities. Adaptation & Aging, 41(2), 107–128. doi:10.1080/01924788.2017.1306380

- Emblad, S. Y., & Mukaetova-Ladinska, E. B. (2021). Creative art therapy as a non-pharmacological intervention for dementia: A systematic review. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease Reports, 5(1), 353–364. doi:10.3233/ADR-201002

- Evans, S. C. Barrett, J., Mapes, N., Hennell, J., Atkinson, T., Bray, J., … Russell, C. (2019). Connections with nature for people living with dementia. Working with Older People, 23(3), 142–151. doi:10.1108/WWOP-01-2019-0003

- Forbes, D. Forbes, S. C., Blake, C. M., Thiessen, E. J., & Forbes, S. (2015). Exercise programs for people with dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (4).

- Galbraith, B., Larkin, H., Moorhouse, A., & Oomen, T. (2015). Intergenerational programs for persons with dementia: A scoping review. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 58(4), 357–378. doi:10.1080/01634372.2015.1008166

- Gitlin, L. N. Marx, K. A., Alonzi, D., Kvedar, T., Moody, J., Trahan, M. & Van Haitsma, K. (2017). Feasibility of the tailored activity program for hospitalized (TAP-H) patients with behavioral symptoms. The Gerontologist, 57(3), 575–584. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw052

- Javaid, S. N. (2021). The role of animal-assisted therapy in the management of people with dementia: A systematic literature review. BJPsych Open, 7(S1), S276–S276. doi:10.1192/bjo.2021.734

- Ludlow, D. (2016). Keeping residents stimulated needs to be a top priority. Nursing And Residential Care, 18(12), 645–647. doi:10.12968/nrec.2016.18.12.645

- Mulhall, A. (2003). In the field: Notes on observation in qualitative research. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 41(3), 306–313. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02514.x

- National Institute of Clinical Excellence (2013) Mental wellbeing of older people in care homes. Quality standard [QS50]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs50/chapter/Quality-statement-1-Participation-in-meaningful-activity

- Ranada, A., & Osterholm, J. (2022). Promoting active and healthy ageing at day centres for older people. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 46(3), 1–15.

- Ritchie, L. Quinn, S., Tolson, D., Jenkins, N. & Sharp, B. (2019). Exposing the mechanisms underlying successful animal-assisted interventions for people with dementia: A realistic evaluation of the Dementia Dog Project. Dementia, 20(1), 66–83. doi:10.1177/1471301219864505

- Shoesmith, E. Charura, D. & Surr, C. (2020). What are the required elements needed to create an effective visual art intervention for people living with dementia? A systematic review. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 46(2), 1–28.

- Sleeman, K. E. Ho, Y. K., Verne, J., Gao, W. & Higginson, I. J., (2014). Reversal of English trend towards hospital death in dementia: A population-based study of place of death and associated individual and regional factors, 2001-2010. BMC Neurology, 14(1), 59. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-14-59

- Smythe, A. Jenkins, C., Galant-Miecznikowska, M., Bentham, P. & Oyebode, J. (2017). A qualitative study investigating training requirements of nurses working with people with dementia in nursing homes. Nurse Education Today, 50, 119–123. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2016.12.015

- Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE). (2006). Dignity in care (Adult service practice guide 09). London, United Kingdom: SCIE.

- Spanswick, E. (2015) Pioneering HenPower project launched in London. https://www.carehome.co.uk/news/article.cfm/id/1570167/pioneering-henpower-project-launched-in-london

- Thraves, L. (2016). Fix Dementia Care: NHS and care homes. London, UK: Alzheimer’s Society.

- Ueda, T. Suzukamo, Y., Sato, M. & Izumi, S. I. (2013). Effects of music therapy on behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Research Reviews, 12(2), 628–641. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2013.02.003

- Windle, G. Joling, K.J., Howson-Griffiths, T., Woods, B., Jones, C.H., Van de Ven, P.M., .. Parkinson, C. (2018). The impact of a visual arts program on quality of life, communication, and well-being of people living with dementia: A mixed-methods longitudinal investigation. International Psychogeriatrics, 30(3), 409–423. doi:10.1017/S1041610217002162

- Windle, G. Algar-Skaife, K., Caulfield, M., Pickering-Jones, L., Killick, J., Zeilig, H. & Tischler, V. (2020). Enhancing communication between dementia care staff and their residents: An arts-inspired intervention. Aging & Mental Health, 24(8), 1306–1315. doi:10.1080/13607863.2019.1590310

- Woods, B. O'Philbin, L., Farrell, E.M., Spector, A.E. and Orrell, M. (2005). Reminiscence therapy for dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2.

- Yakimicki, M. L. Edwards, N.E., Richards, E. & Beck, A. M. (2019). Animal-assisted intervention and dementia: A systematic review. Clinical Nursing Research, 28(1), 9–29. doi:10.1177/1054773818756987

- Yamamoto, R. (2021). Improve as creative aging: The perceived influences of theatrical improvisation on older adults, activities. Adaptation & Aging, 45(3), 217–233. doi:10.1080/01924788.2020.1763075

- Zucchella, C. Sinforiani, E., Tamburin, S., Federico, A., Mantovani, E., Bernini, S., .. Bartolo, M. (2018). The multidisciplinary approach to Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. A narrative review of non-pharmacological treatment. Frontiers in Neurology, 9, 1058. doi:10.3389/fneur.2018.01058