ABSTRACT

Mobile apps are omnipresent due to the proliferation in the adoption of smart mobile devices and the widespread availability of the Internet, which represent two key enablers for the acceptability of mobile apps. Although there are many mobile apps available that cater to diverse needs, including those of older adults, there is a lack of understanding on the usability aspects that affect the acceptability of mobile apps among older adults. Even though many studies have evaluated older adults’ perceptions toward mobile apps, they are predominantly conducted in developed countries using factors deductively derived from existing theories and hypothetical scenarios without an actual prototype for evaluation. To address these noteworthy gaps, this study adopts a qualitative case study approach (i.e. inductive) to explore the usability aspects of a mobile application (or app) that supports the mobility of older adults (i.e. mobility app) using the TakeMe app (i.e. prototype) and a sample of Malaysian older adults over the age of 60 (i.e. developing country) as a case. Through this study, the findings suggest that including older adult-friendly usability features can boost the adoption of mobility apps among older adults, and that these features span across the domains of learning (e.g. guided in-person by close ones such as children, partner, relatives), usefulness (e.g. variety of services), ease of use (e.g. simplicity), and security (e.g. authenticity of services, privacy protected).

Introduction

We live in a technological world, from the televisions we watch to the mobile phones that we carry to the means (e.g., apps) we use to acquire information for decision making (Díaz-Bossini & Moreno, Citation2014). According to Thamutharam et al. (Citation2021), the population of older adults will increase from 350 million to 1.5 billion by 2050, making them more dependent on the pervasiveness of mobile technology. Hence, older adults are no exception; they are progressively embracing various sorts of mobile-mediated technology in their life (Thamutharam et al., Citation2021). According to Nasir et al. (Citation2008), the percentage of older adults who own a smartphone is low, dropping significantly to 8.7%. This continues to be true over time as the adoption rates of mobile technology continue to be low among older adults as compared to their younger counterparts (Mitzner et al., Citation2019). Noteworthily, older adults appear to be a disregarded user group in the development of mobile devices and services even though the prerequisites for creating a well-functioning solution for them are well acknowledged (Wang et al., Citation2019). Although the current percentage of older adults who own a smartphone remains low, there is a growing need to ensure that this growing demographic is not left behind in the rapidly evolving digital landscape (Lim & Bowman, Citation2022a; Lim et al., Citation2023). To close the existing digital gap, it is essential to comprehend and tackle the obstacles preventing technology adoption by older adults (Ardelean & Redolat, Citation2023; H. -J. Chen, Citation2023; H. J. Chen, Citation2023; Morrison et al., Citation2022). Mobile apps can provide crucial services and assistance to older adults, including healthcare access (Karlin & Weil, Citation2023; Mishra & Pandey, Citation2023; Sahoo et al., Citation2023) and social interaction opportunities (Oyinlola, Citation2022; Talmage et al., Citation2021). Investigating the user experience of mobile apps for older adults is vital for determining their unique needs and preferences, which will help improve app design and usability, and ultimately, encouraging the adoption of these apps, enhancing their well-being, and promoting digital inclusion (Chua et al., Citation2022).

Older adults over the age of 60 use smart mobile devices for various reasons, such as emergency calls or instant messaging (Low et al., Citation2021). Through smart mobile devices, mobile apps enable not only ubiquitous communication (H. -J. Chen, Citation2023; H. J. Chen, Citation2023) but also instant access to opportunities and services that facilitate the autonomy of older adults (Lee et al., Citation2020; Tang et al., Citation2022; Thamutharam et al., Citation2021). In this regard, these solutions provide older adults with a sense of independent living because they can be accessed at any time and from any location (Peek et al., Citation2016), thereby enhancing their capability and capacity to age in a place of choice (Lim & Bowman, Citation2022b). The importance of these solutions is further accentuated in recent times as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has led to a new normal that highlights the importance of community participation and social activity while placing technology-mediated mobile solutions at the forefront (e.g., physical contactless social connectivity) (Bowman & Lim, Citation2023; Lim, Citation2021, Citation2022).

However, Thamutharam et al. (Citation2021) found that the adoption of mobile apps among older adults remain challenging as they often avoid employing more sophisticated functions, non-user-friendly menu layouts, and confusing instructions on how to identify and utilize a certain feature, as well as overpriced services. Noteworthily, older adults encounter many challenges (e.g., cognitive challenges, frailty) (Laver et al., Citation2022; Lazarus & Soejono, Citation2022; Tang et al., Citation2022), which may not necessarily be experienced by their younger counterparts. Thus, the simplicity of use and the genuine necessity of solutions are critical elements because with this, solutions will truly assist independent life, and older adults will be eager to use them (Low et al., Citation2021).

Much comparative research has been conducted on the factors of technology adoption in the older adult population by incorporating existing theories such as the technology acceptance model (TAM), unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT), and innovation diffusion theory (IDT), among others, but little work has been made to examine the quality of older adults’ experiences in using new technology (Alturki & Gay, Citation2019). One possible reason is the overreliance on existing theories, where factors are deductively derived and thus remain confined to those espoused by those theories. In this regard, the use of inductive techniques (e.g., interviews) can revealed new insights that go beyond those predefined by existing theories, thereby leading to potentially new discoveries, if not, a reaffirmation or redefining of existing understanding. This is in line with Androutsou et al. (Citation2020) and Özsungur (Citation2021), who showcased the value of inductive research. Indeed, the potential of inductive research has also gained prominence recently. For example, login details, new interfaces, safety, and privacy concerns, as well as declining health conditions, have been found to be the main hurdles limiting older adults’ continuous use of technology (Androutsou et al., Citation2020). Further research in this direction, particularly from the mobile app perspective, is therefore promising, especially given that mobile technology is becoming increasingly pervasive in life (Özsungur, Citation2021).

Most studies on older adults’ usability evaluations of mobile apps have also been conducted in general (e.g., mention of ride-hailing apps) (Talmage et al., Citation2021). Without actual interaction with the app itself, the specific aspects or reasons that mitigate the usability of such solutions may not be ascertained adequately. Additionally, most studies in the area are concentrated in developed countries, as evidenced by the bibliometric findings in Tajudeen et al. (Citation2022). Though scholars have begun to examine older adults’ interactions with mobile apps using a prototype (e.g., MemoryUp) in developed countries (e.g., the Netherlands) (Klaming et al., Citation2023) and albeit more generally (e.g., Facebook) in developing countries (e.g., Nigeria) (Oyinlola, Citation2022), additional efforts remain necessary to gain a deeper understanding of older adults’ perceptions toward mobile apps developed to enhance their quality of life. Without in-depth information on users and the specific issues that they encounter when they interact with an actual technological prototype, the theorization of older adults’ usability evaluations toward such solutions may be limited (i.e., theoretical gap) and technology developers may be unable to design technologies that will be useful and user-friendly for older adults (i.e., practical gap) (Lee et al., Citation2020).

Given the above, this study aims to address the extant gaps in understanding older adults’ usability evaluations of mobile apps (i.e., lack of validity without prototype, lack of representation from developing country perspective, lack of participant voice from deductive approach). To do so, this study adopts an inductive case study approach by interviewing older adults in a developing country (Malaysia) who had the opportunity to interact with a mobile app (TakeMe) that promotes and supports mobility. In particular, this study is interested to explore older adults’ experiences with the TakeMe app to add to our understanding of older adults’ perceptions of the usability of mobile apps. Through this study, a list of older adult-friendly usability features that can boost the adoption of mobile apps for greater mobility among older adults will be identified, which has the potential to initiate discussions and bring planners, scholars, health practitioners, educators, residents, developers, as well as local, national, and international governments. This will in turn inform future planning and the development of older adult-friendly technology. The work presented here is also significant and multidisciplinary as it contributes to the fields of gerontology, social sciences, technology, and health.

In the next section, a brief literature review is provided on the ways in which technology can serve the aging population alongside the features of older adult-friendly technologies. Following that, the method of an inductive case study approach and the ensuing findings are reported, incorporating older adults’ voices on various technology features of an older adult-friendly mobility app.

Literature review

Several prior studies concur that mobile apps are developed for older adults to assist with their everyday lives, with the majority of them being utilized for health management (Ventola, Citation2014). However, Gordon et al. (Citation2019) found that older adults’ use of such mobile solutions was strictly limited, which might be attributable to a variety of factors including (1) challenges with user interface design, (2) a lack of digital competence among older adults, and (3) technological affordability. Evidently, if a mobile app lacks older adult-friendly features, it is likely to be abandoned by older adult users (Gordon et al., Citation2019). Several researchers have attempted to identify the usability features that could enhance the acceptance of mobile apps among older adults (Androutsou et al., Citation2020; Gordon et al., Citation2019; Thamutharam et al., Citation2021).

Harrison et al. (Citation2013) define mobile app usability as the measure of the ease of using mobile apps. The usability of mobile apps is critical for their adoption among users, particularly older adults (Harrison et al., Citation2013). According to Aryana and Clemmensen (Citation2013), smartphones have essential functions, such as making and receiving calls, and nonessential functions, such as calendars, address books, notes, reminder alarms, and handling emergencies, which can assist in making life easier for older adults.

The usability of apps may not necessarily have the same usability components (Alturki & Gay, Citation2019). There have been numerous works that examined the usability of apps for a wide range of users. The majority of these focused on efficiency (Aryana & Clemmensen, Citation2013; Harrison et al., Citation2013), satisfaction (Aryana & Clemmensen, Citation2013; Harrison et al., Citation2013), effectiveness (Harrison et al., Citation2013), learnability (Aryana & Clemmensen, Citation2013; Harrison et al., Citation2013), errors (Harrison et al., Citation2013), memorability (Harrison et al., Citation2013), and cognitive load (Harrison et al., Citation2013).

Thamutharam et al. (Citation2021) stated that features such as visual and memory aids as well as features to minimize user errors and safeguard users will be helpful to older adults. Taking a checklist approach, Díaz-Bossini and Moreno (Citation2014) propose a set of features that developers should consider when developing mobile apps for older adult users, as shown (adapted) in .

Table 1. Díaz-Bossini and Moreno’s Older Adult-Friendly Mobile Apps Features Checklist.

Despite the numerous older adult-friendly features available on mobile apps, older adult acceptance of these apps remains low (Wildenbos et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, little research has been undertaken to assess the perceptions of older adults when utilizing specially built mobile apps. The present study advances existing work in the field, specifically by taking the recommendations from existing work (Díaz-Bossini & Moreno, Citation2014) as input guidelines for developing an actual prototype of an older adult-friendly mobile app to promote and support greater mobility. The usability of the app is then evaluated using an inductive case study approach by interviewing older adults who had the opportunity to interact and provide feedback about the mobile app. In doing so, the insights herein this study go beyond the proposed checklist and shed more light on the actual categories of usability features that older adults perceive and evaluate when they interact with a mobile app for adoption.

Methodology

In this study, we adopt a qualitative case study approach to investigate older adults’ perceptions of mobile app usability, using the TakeMe app as a case. A qualitative case study is a research approach that allows for an in-depth exploration of a particular case or phenomenon within a real-life context (Alam, Citation2021; Baškarada, Citation2014). This approach is particularly relevant for our research because it enables us to gain a comprehensive understanding of the experiences, needs, and preferences of older adults in Malaysia, a developing country in the Global South. By focusing on the TakeMe app, a mobility app developed by researchers from Monash University Malaysia (Chua et al., Citation2022; Fang et al., Citation2022), we can examine how older adults perceive the usability of an app designed to help them plan their transportation options and book trips (e.g., to the bank, local market) with and without the assistance of volunteers.

To conduct our qualitative case study, we employed semi-structured telephone (including video call) and face-to-face individual interviews from May 2021 to December 2021. This method allowed us to gather rich, detailed data from a sample of older adults in Malaysia. The semi-structured format facilitated an open-ended discussion between the interviewers and the individual participants (Striepe, Citation2021), in this case, about their experiences and perspectives on mobile app usability. The combination of telephone (including video call) and face-to-face interviews was necessary to cater to the preferences of participants in light of the COVID-19 pandemic (Dodds & Hess, Citation2020; Lim & Bowman, Citation2022a). Individual interviews were preferred over focus group interviews to gain personalized insights and mitigate potential bias from group dynamics (Baxter & Jack, Citation2008). One interview was conducted for each participant, with an average of 60 to 90 minutes per participant. As Malaysia is a multiracial country, the interviewers and individual participants communicated across the common mix of English, Malay, and Chinese languages, wherein the latter languages were translated back to English, with the translation reviewed, refined, and ratified by at least two multilingual members of the project team in line with Ozolins et al. (Citation2020). Therefore, this qualitative case study approach provides the opportunity to gain valuable insights into the unique challenges and opportunities faced by older adults when using mobility apps, which can inform the design and development of future apps that cater to their specific needs.

Participants

Purposive sampling is a strategy extensively employed in qualitative research to identify and choose information-rich samples to make the most use of limited resources (Palinkas et al., Citation2015). Hence, this study used purposive sampling, where older adults who were also smartphone users were deliberately recruited. They were also requested to try the prototype app that was specifically designed for them. This explains why it is important for the participants to have some prior experience in using smartphones to facilitate mobile app acceptance.

The participants in this case study consisted of 127 older adults aged 60 and above and were recruited located throughout Malaysia using purposive sampling from two channels: Transforming Cognitive Frailty into Later-Life Self-Sufficiency (AGELESS) Longitudinal Study Cohort and new recruitment from advertisements, nongovernment organizations (NGOs), and community centers (Tang et al., Citation2022). The AGELESS project is a five-year longitudinal study involving Malaysian older adults aged 60 and above. This research was formed by combining two Malaysian aging studies, known as the MELoR and TUA studies, that were conducted between 2013 and 2016. below shows the description of the participant profile for this study.

Table 2. Participant Profile Descriptions.

Ethical considerations

The Monash University Research Ethics Committee Review (Reference Number: 2021–28448–63849) approved the planned research before the researchers contacted or involved any potential participants. Moreover, guiding principles (e.g., participant consent and anonymity, safeguarding research data storage and usage) were established when designing this research based on the regulations for the ethical conduct of research as agreed by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee.

Analysis method and procedure

This study adopted a case study research design, which allows researchers to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the research phenomena (Baxter & Jack, Citation2008). The case study approach allows researchers to explore data in depth within a particular context, and in most circumstances, the procedure involves a specific geographical region or a small number of persons to analyze (Zainal, Citation2007). In this regard, case studies analyze and investigate actual real-life phenomena through the extensive contextual examination of a limited number of occurrences or situations and their interactions (Alam, Citation2021; Baškarada, Citation2014).

The participants were initially asked to watch two videos on the purpose of the TakeMe app and the functions and steps on how to use the app, which took approximately five minutes. The links to these videos were sent to participants for telephone interviews (with the call resumed as soon as participants indicated they finished watching the videos) while participants in face-to-face interviews viewed these videos in person. Following a virtual experience with the app, the participants were given a live demo of the app and questions about it, which took approximately 10 minutes. The live demo of the app for telephone interviews took place using video call while the same demo was done in person for face-to-face interviews. This was aimed at collecting more information regarding their perceptions of using the TakeMe app in terms of its usability. The questions were based on four probes that evaluated the participants’ perceptions of the usability of the developed app, which is shown in .

Table 3. Interview Questions.

Open coding, axial coding, and selective coding were conducted to systematically identify, categorize, and organize recurring patterns and themes that emerged from the interview data (Williams & Moser, Citation2019). To ensure the reliability and validity of the coding process, two members of the research team were involved in the data coding process, wherein each member initially coded a subset of the data independently before a meeting was convened to discuss, compare, and refine the codes, resolving any discrepancies through consensus, thereby ensuring inter-coder reliability and mitigating personal biases (Gligor & Autry, Citation2012; Strauss & Corbin, Citation1990). The research team also engaged in peer debriefing through regular discussions with researchers who were not directly involved in this research (e.g., internal and external presentations), who provided feedback about the research, including data interpretation, which, in turn, further mitigates the potential of personal bias (Baxter & Jack, Citation2008; Spall, Citation1998).

Findings

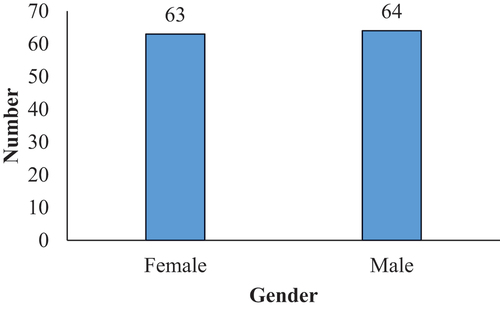

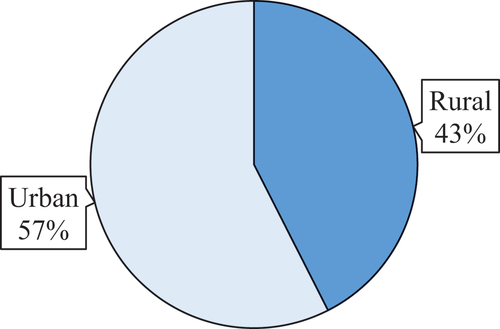

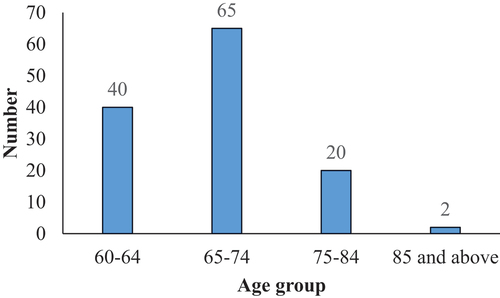

shows the number of males and females involved in this study followed by the percentage of rural and urban areas in . shows the number of participants by age, the highest number being from the age group of 65 to 74 years.

Figure 2. Percentages of rural and urban participants.

Figure 3. Number of participants by age group.

The findings from the interviews reveal four major themes regarding older adults’ perceptions and evaluations of the usability of mobility apps such as the TakeMe app. These themes span across the features of learning (e.g., guided in-person by close ones such as children, partner, relatives), usefulness (e.g., variety of services), ease of use (e.g., simplicity), and security (e.g., authenticity of services, privacy protected). These themes are discussed in the next subsections.

Usability through the lens of learning

The first theme relates to older adults’ learning preferences of new technology, which was uncovered by Probe 1 (i.e., the TakeMe app prototype video instructions) and presented in . There appears to be a negative sentiment regarding the duration of the video, “If it is too complicated, too long, too many things, then it is a bit troublesome, [It needs to be] short and good, very simple” (T008, 68, female, urban), indicating that many of the older adults would prefer to have short and simple instruction videos, which may not always be possible with service-rich mobile apps. Meanwhile, the statement “I prefer somebody beside me to help me. If videos, sometimes a bit difficult. Because you [will need] to go back to recall it. But if you got somebody beside you, it’s easy [because they can answer your questions right away]” (T014, 65, male, urban) shows that older adults prefer to have someone by their side to teach them how to use new apps such as the TakeMe app. They tend to prefer to have their children, spouse, or relatives to help them understand such technology: the statement “Have them to walk through the [children] to tell their parents. Because if you give talks, they won’t be able to come” (T079, 76, male, urban) showed that majority of older adults prefer to learn new things from people close to them, and having others to do so may not be workable if older adults cannot attend the talk. Another comment stated that “some might not [able to] catch up so fast you know … you talk to them, show some pictures diagram how you going to do all this. Very easy person-to-person talks much better [for] old people” (T093, 64, female, urban), reaffirming the need for personal and personalized explanation. The majority of older adults preferred face-to-face interactions when it comes to learning new things, as it is easier for them to understand and ask questions.

Table 4. Main Thematic Findings from Probe 1.

Usability through the lens of usefulness

The second theme highlights older adults’ willingness to use new technology as a result of the technology’s usefulness, which was revealed by Probe 2 and is presented in . The findings indicate that older adults provided positive statements on the usefulness of the TakeMe app as well as its functions. Older adults are willing to use the TakeMe app once they understand its purpose and function, as it provides them the usefulness they can implement into their daily activities. One example of a positive statement was given by a participant as follows:

Table 5. Main Thematic Findings from Probe 2.

I need this kind of help … if let’s say [for a] medical checkup … [it’s] difficult to go there … it’s difficult to park, there is no parking space. So, if we have this kind of app … ask the app to send us there … we don’t have to worry about the car park. (T010, 67, male, urban)

Most older adults indicated that the TakeMe app can provide them convenience in terms of assistance in traveling to certain places, which shows that the older adults understand the purpose of the app and the value of the app in assisting them in their daily living (i.e., enabling them to be mobile out of the home environment and thus being able to live and participate independently in society). Another participant stated that they can get assistance when carrying things or buying necessities especially for those who are from rural areas:

Very good because we are old people, our kids [are] unable to bring us around as they are busy working … if [we] have this app, it will be very good for [us] to go out [to] buy things for the village needs here. We [can] buy medicine or anything [that we need]. (T042, 66, female, rural)

Usability through the lens of ease of use

The third theme highlights older adults’ willingness to use new technology due to the technology’s ease of use, which was uncovered through Probe 3 and is presented in . The majority of the older adults said TakeMe was simple to use. One participant mentioned, “The app itself is perfect. You can just download it and use it” (T010, 67, male, urban), showing that it is easy to understand the app’s user interface; the buttons and steps to use the app are easy and simple. Participants also claimed that the app is user-friendly and that they can use it immediately, as evidenced by the following statements:

Table 6. Main Thematic Findings from Probe 3.

I believe this is quite simple and user-friendly … The steps are quite simple. (T014, 65, male, urban)

With a very simple one or two step, I can now proceed [to go around easily]. (T015, 60, male, urban)

Usability through the lens of security

The fourth theme indicates that older adults’ willingness to use new technology may be influenced by security concerns, which was revealed by Probe 4 and is presented in . Without repeating the perceptions shared in the previous three probes, the additional finding from this probe shows that there appears to be negative statements regarding the aspect of security. The words scam and cheated were mentioned by almost all participants, as illustrated in the following:

Table 7. Main Thematic Findings from Probe 4.

I supposed everybody is worried because of all these scams and cons … if I [must] give my details to something like that literally unknown, that just raises my alarm, red flag so to speak. Security-wise, there are just too many things out there that could possibly go wrong especially with seniors … because seniors are vulnerable to all these scams. (T050, 61, male, urban)

When we see somebody trying to help us, give us a hand, we [may] just fall into their hands. We just let them do it. That’s how many elderlies get cheated [easily]. (T052, 61, male, urban)

Other findings revealed that older adults were primarily concerned about the app’s service – the trustworthiness of the service given by volunteers. For example:

I’ve been thinking about it since I saw the video. What if the person is not trustworthy, what happens next? (T081, 69, female, urban)

Another participant indicated that it is crucial for older adults to have records of volunteers such as car numbers, names, identification cards (IC), and other information. This is to demonstrate that the volunteers’ services are legitimate and trustworthy, as illustrated in the following statement:

You have a record [to prevent] any unforeseen circumstances … when I use taxi … I [will] always ask for a receipt even though I can’t claim it. Why? I just want to have a record of the taxi number and the time … it is more important to assure [older adults go] through your system to [show] that you don’t have to worry … [and] assure that you have vetted those volunteers thoroughly. Trust, especially in this country, [is important]. (T095, 66, male, urban)

Discussion

The technology acceptance model is a foundational theoretical lens for understanding the factors that influence individuals’ adoption and usage of technology, wherein the core tenets of model posit that the ease of use and usefulness of a technology play a critical role in determining the extent to which people, including older adults (Lee et al., Citation2020; Teh et al., Citation2017), will adopt and use that technology (Davis, Citation1989). The present study offers insights that extend the theoretical generalizability of the technology acceptance model and the implications that could be derived specific to the aging population and their interaction with mobile apps.

Theoretical implications

The present study offers two noteworthy findings for theory that (1) reaffirm past understanding and (2) contribute new understanding about older adults’ perception and evaluation of the usability of mobile apps using the case of a mobility app in the form of the TakeMe app.

In particular, the present findings reaffirm the importance of ease of use and usefulness of new technology as usability factors that influence the adoption of new technology among older adults. Although these findings are not new, the fact that they emerged inductively (naturally) rather than deductively (informed by theory) provides fresh evidence that highlights the importance of the core tenets of technology acceptance theories in explaining the adoption of new technology (Lim, Citation2018), particularly among older adults (Özsungur, Citation2021), including those in developing countries, as the present study evidences. When taken together with the findings of prior studies from developed countries (Tajudeen et al., Citation2022), the findings of this study suggests that the core of older adults’ usability evaluations of new technology may not be very different – they still hold the ease of use and usefulness of new technology as key usability factors in high regard.

Moreover, the present study shows that learning preferences and security concerns influence the usability of new technology among older adults, wherein the former highlights an enabler that needs to be addressed in order for older adults to truly understand how to use and navigate new technology, whereas the latter points out the importance of reassuring older adults of their privacy and safety when using new technology. These findings reaffirm the importance of learning and security in influencing technology adoption among older adults (Jin et al., Citation2019; Kavandi & Jaana, Citation2020; Kumar & Chand, Citation2019) while making a seminal appearance as part of usability factors rather than independent factors in the field of technology adoption. Noteworthily, the tenets of learning (e.g., guided in-person by close ones such as children, partner, relatives) and security (e.g., authenticity of volunteers) revealed herein this study also points to the existence of social influence (Lim, Citation2022), which could be explained from a cultural perspective, as developing countries in the Global South like Malaysia have a strong collectivist (interdependent) rather than individualist (independent) culture (Zong et al., Citation2023).

Taken collectively, these findings are highly important as they shape the way in which usability factors should be considered, whereby ease of use and usefulness represent the core usability factors of the technology itself (as espouse by technology acceptance theories), whereas learning and security represents the enabler and barrier, respectively, in making that technology truly usable (adopted) among users (as extended tenets of usability governing technology acceptance), in this case, older adults.

Managerial implications

The present study also several implications for consideration as part of managerial practice. It should nonetheless be noted that these suggestions remain preliminary due to the nature of qualitative research, which is focused on uncovering existential nuances rather than empirical generalizability. Yet, the pragmatic logic that emerges from the interpretation of participant voices could be potentially useful and meaningful in supporting further exploration and experimentation among researchers and technology developers alike.

From the learning perspective of usability, this study found that older adults are unable to rely solely on instruction videos as they lose their interest and easily forget (short memory). The video was about five minutes in length, covering detailed steps about the features of the mobility app. This points out the importance for messages to be sharp and succinct, making it easy for older adults to capture the important details. The use of interactive videos that will pause and encourage the follow-through of older adults when it comes to app instruction might also be useful. Another concern related to learning was that older adults are not familiar with learning new things virtually, especially those related to technology. This is because older adults are only comfortable and find it easy to understand when they were taught by their close others in-person, such as by their partner, children, or relatives. This points out the importance of informal learning, which provides convenience for older adults to seek help whenever they encounter issues when using the app. In addition to virtual learning concerns, there could be a lack of communication reliability. For example, an older adult may misinterpret a message via video. Hence, face-to-face interactions allows communication reliability, as it enhances learning. In this regard, a societal approach may be required to strengthen older adults’ learning of new technology, thereby highlighting the importance of getting close others on board when attempting to persuade older adults about the usability of new technology and their propensity to adopt that technology.

From the usefulness perspective of usability, this study found that older adults are satisfied with the purpose of the services and intended to use the mobility app. This is because services such as accompanying older adults for medical checkups, carrying things, and so on are beneficial and can be implemented in their daily activities. Such services also allow older adults to be independent in their daily living, enabling them to live and participate in society without having to wait for family members’ availability to provide them with assistance. Therefore, older adults are willing to use the app and might see it fit to make some adjustments to incorporate the app into their daily activities. In this regard, this study highlights the importance of incorporating useful features in mobile apps targeted to older adults, wherein usefulness relates to the extent to which older adults derive value that resonate with their needs in daily activities.

From the ease of use perspective of usability, the design of the app was surprisingly acceptable among older adults to whom the app was shown, as they did not raise any issues in terms of the buttons, display, colors, menus, or functions in the TakeMe app prototype. This may be due to the study’s leverage of existing guidelines such as the checklist by Díaz-Bossini and Moreno (Citation2014) for developing older adult-friendly mobile apps, thereby highlighting the importance of looking back into the literature for guidance before developing new technology. More importantly, the results of this study imply that the features of a mobile app need to be simplified as much as possible when its target users are older adults; that is, it must have age-friendly features. For example, an older adult can use a mobile app more easily when the sign-up and verification procedures are automated, such as having the mobile app to automatically detect the retrieval (as opposed to manually locating) of a one-time password (OTP) where a secure PIN code is sent to the user via SMS. In addition, the results of this study showed positive comments on the app’s design where the app was easy for users to identify, download, install, and use on their mobile devices.

From the security perspective of usability, the findings indicate that mobile apps may raise privacy and safety concerns among older adults. Noteworthily, older adults are acutely aware of the possibility of being scammed by strangers as the TakeMe app provides volunteer services that older adults can use to support their daily activities and functioning in society. This points out the importance of considering everyday technology as a possible security concern in the community. In addition, older adults may not be able to trust a stranger (volunteer) that requests them to make choices by pressing buttons when trying to accept volunteer services. They are skeptical when providing their home address or IC details in the prototype app. This is because older adults are hesitant to provide such information, which can lead to an undesirable situation such as being cyber-hacked (e.g., identify theft, misuse of personal information). Hence, mobile apps, when targeted to older adults, will need to be highly secure, both from a digital (privacy) and physical (safety) perspective, wherein the responsibility for ensuring security is not only assumed by the technology organization (e.g., app developer) but also the organization managing the app (e.g., app owner) or providing support services to the app (e.g., association of volunteers).

Conclusion

To this end, this study contributes to a better understanding of the usability factors that older adults perceive and evaluate when pose with a new technology targeted to improve their quality of life, in this case, a mobile app that supports their daily activity mobility needs for seamless living and functioning in society. Noteworthily, this study highlights that older adult-friendly usability features spanning across the domains of learning (e.g., guided in-person by close ones such as children, partner, relatives), usefulness (e.g., variety of services), ease of use (e.g., simplicity), and security (e.g., authenticity of services, privacy protected) can boost the adoption of mobility apps among older adults. More importantly, these findings contributes to reaffirm and extending our theoretical understanding of the usability of mobile apps targeted to older adults, as well as the managerial practice in developing and managing such technological solutions. Indeed, the discovery of profound usability features is critical to ensuring that older adults do not shy away from the benefits of technological innovation from mobile apps. A better understanding of the needs and capabilities of these features, which enhance the usability of mobile apps, allows developers and designers to offer more practical apps while also promoting changes in the way older adults view mobile apps so that they, as well, can implement these into their everyday life.

Notwithstanding the contributions of this study, several limitations exist. First, this study is limited to usability insights from a single prototype (i.e., TakeMe app). Given the promising insights that were inductively reveal through this study, future research is encouraged to develop prototypes for user evaluation in order to gain insights that may reaffirm and/or extend the insights from the present study. Noteworthily, future research should consider the practical recommendations herein as well as that of prior studies so as to address the known issues beforehand – this approach was proven beneficial, particularly on the ease of use aspect of usability, as indicated in the discussion of managerial implications. Second, this study is limited to insights from older adults taken as a collective. While sociodemographic information was collected (e.g., age group, gender, location), further delineation of insights were not possible as no observable differences in responses were found. This highlights the potential value of a deductive approach, which could be adopted and implemented via a quantitative study in the future. Third, this study is limited to insights from a single developing country (i.e., Malaysia), and thus, future research – including quantitative research – in other developing and developed countries is encouraged to extend, support, and/or refute the generalizability of the insights herein. Finally, this study is limited to a single source of data (i.e., individual interviews), and thus, future research could engage in multiple sources of data (e.g., focus group, neuroscience, participant observation, survey) to facilitate triangulation.

Acknowledgments

This research is under the AGELESS research program that was funded by the Ministry of Higher Education Long Term Research Grant Scheme (LRGS/1/2019/UM/01/1/1). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alam, M. K. (2021). A systematic qualitative case study: Questions, data collection, NVivo analysis and saturation. Qualitative Research in Organizations & Management: An International Journal, 16(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1108/QROM-09-2019-1825

- Alturki, R., & Gay, V. (2019). Usability attributes for mobile applications: A systematic review. In Recent trends and advances in wireless and IoT-enabled networks (pp. 53–62). Springer.

- Androutsou, T., Kouris, I., Anastasiou, A., Pavlopoulos, S., Mostajeran, F., Bamiou, D. E., Genna, G. J., Costafreda, S. G., & Koutsouris, D. (2020). A smartphone application designed to engage the elderly in home-based rehabilitation. Frontiers in Digital Health, 2, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdgth.2020.00015

- Ardelean, A., & Redolat, R. (2023). Supporting behavioral and psychological challenges in Alzheimer using technology: A systematic review. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2023.2172900

- Aryana, B., & Clemmensen, T. (2013). Mobile usability: Experiences from Iran and Turkey. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 29(4), 220–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2013.765760

- Baškarada, S. (2014). Qualitative case studies guidelines. The Qualitative Report, 19(40), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2014.1008

- Baxter, P., & Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report, 13(4), 544–559.

- Bowman, C., & Lim, W. M. (2023). The secrets to aging well: Animal interactions, social connections, volunteerism, and more. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 47(2), 107–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2023.2207282

- Chen, H. J. (2023). The different value of Facebook for Taiwanese older adults. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2023.2172877

- Chen, H. -J. (2023). Older adults and social app use: A subjective well-being perspective. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2023.2173119

- Chua, C. S. W., Lim, W. M., Teh, P. L., & Pedell, S. (2022, December). Older adults’ evaluations of mobile apps: Insights from a mobility app-based solution. In IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, (pp. 1159–1163). IEEE.

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

- Díaz-Bossini, J. -M., & Moreno, L. (2014). Accessibility to mobile interfaces for older people. Procedia computer science, 27, 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2014.02.008

- Dodds, S., & Hess, A. C. (2020). Adapting research methodology during COVID-19: Lessons for transformative service research. Journal of Service Management, 32(2), 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-05-2020-0153

- Fang, B., Chong, C. Y., Teh, P. L., & Lee, S. W. H. (2022, June). Assessing the needs of mobility solution for older adults through living lab approach: An experience report. In Cross-Cultural Design. Applications in Business, Communication, Health, Well-being, and Inclusiveness: 14th International Conference, CCD 2022, Held as Part of the 24th HCI International Conference, HCII 2022, Virtual Event, Proceedings, Part III (pp. 321–336). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Gligor, D. M., & Autry, C. W. (2012). The role of personal relationships in facilitating supply chain communications: A qualitative study. The Journal of Supply Chain Management, 48(1), 24–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2011.03240.x

- Gordon, M. L., Gatys, L., Guestrin, C., Bigham, J. P., Trister, A., & Patel, K. (2019). App usage predicts cognitive ability in older adults. Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

- Harrison, R., Flood, D., & Duce, D. (2013). Usability of mobile applications: Literature review and rationale for a new usability model. Journal of Interaction Science, 1(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/2194-0827-1-1

- Jin, B., Kim, J., & Baumgartner, L. M. (2019). Informal learning of older adults in using mobile devices: A review of the literature. Adult Education Quarterly, 69(2), 120–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741713619834726

- Karlin, N. J., & Weil, J. (2023). Need and potential use of telemedicine in two rural areas. Activities, Adaptation & Aging.

- Kavandi, H., & Jaana, M. (2020). Factors that affect health information technology adoption by seniors: A systematic review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 28(6), 1827–1842. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13011

- Klaming, L., Robbemond, L., Lemmens, P., & Hart de Ruijter, E. (2023). Digital compensatory cognitive training for older adults with memory complaints. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 47(1), 10–39.

- Kumar, B. A., & Chand, S. S. (2019). Mobile learning adoption: A systematic review. Education and Information Technologies, 24(1), 471–487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-018-9783-6

- Laver, K., Yannelis, F., Flatman, S., Block, H., & Rahja, M. (2022). Identifying sensory preferences in people with changes in cognition: The SPACE tool. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 47(2), 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2022.2044988

- Lazarus, G., & Soejono, C. H. (2022). Unsupervised home-based exercise for rural frail elderly: An evidence-based case-report. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 46(3), 218–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2022.2028052

- Lee, L. Y., Lim, W. M., Teh, P. L., Malik, O. A. S., & Nurzaman, S. (2020). Understanding the interaction between older adults and soft service robots: Insights from robotics and the technology acceptance model. AIS Transactions on Human-Computer Interaction, 12(3), 125–145. https://doi.org/10.17705/1thci.00132

- Lim, W. M. (2018). Dialectic antidotes to critics of the technology acceptance model: Conceptual, methodological, and replication treatments for behavioural modelling in technology-mediated environments. Australasian Journal of Information Systems, 22. https://doi.org/10.3127/ajis.v22i0.1651

- Lim, W. M. (2021). History, lessons, and ways forward from the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Quality and Innovation, 5(2), 101–108.

- Lim, W. M. (2022). Toward a theory of social influence in the new normal. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 46(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2022.2031165

- Lim, W. M., & Bowman, C. (2022a). Aging and COVID-19: Lessons learned. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 46(4), 279–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2022.2132602

- Lim, W. M., & Bowman, C. (2022b). Aging in a place of choice. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 46(3), 183–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2022.2097806

- Lim, W. M., Kumar, S., Pandey, N., Verma, D., & Kumar, D. (2023). Evolution and trends in consumer behaviour. Insights from Journal of Consumer Behaviour Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 22(1), 217–232. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.2118

- Low, S. T. H., Sakhardande, P. G., Lai, Y. F., Long, A. D. S., & Kaur-Gill, S. (2021). Attitudes and perceptions toward healthcare technology adoption among older adults in Singapore: A qualitative study. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.588590

- Mishra, A., & Pandey, N. (2023). Global entrepreneurship in healthcare: A systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis. Global Business and Organizational Excellence. https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.22193

- Mitzner, T. L., Savla, J., Boot, W. R., Sharit, J., Charness, N., Czaja, S. J., & Rogers, W. A. (2019). Technology adoption by older adults: Findings from the PRISM trial. The Gerontologist, 59(1), 34–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny113

- Morrison, L., McDonough, M., Won, S., Matsune, A. J., & Hewson, J. (2022). Older adults’ physical activity and social participation during COVID-19. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 46(4), 320–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2022.2094658

- Nasir, M. H. N. M., Hassan, H., & Jomhari, N. (2008). The use of mobile phones by elderly: A study in Malaysia perspectives. Journal of Social Sciences, 4(2), 123–127. https://doi.org/10.3844/jssp.2008.123.127

- Oyinlola, O. (2022). Social media usage among older adults: Insights from Nigeria. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 46(4), 343–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2022.2044975

- Ozolins, U., Hale, S., Cheng, X., Hyatt, A., & Schofield, P. (2020). Translation and back-translation methodology in health research–A critique. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 20(1), 69–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737167.2020.1734453

- Özsungur, F. (2021). The effects of successful aging in the workplace on technology acceptance and use behaviour. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 45(2), 159–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2020.1744826

- Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(5), 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

- Peek, S. T., Luijkx, K. G., Rijnaard, M. D., Nieboer, M. E., van der Voort, C. S., Aarts, S., van Hoof, J., Vrijhoef, H. J., & Wouters, E. J. (2016). Older adults’ reasons for using technology while aging in place. Gerontology, 62(2), 226–237. https://doi.org/10.1159/000430949

- Sahoo, S., Sahoo, J., Kumar, S., Lim, W. M., & Ameen, N. (2023). Distance is no longer a barrier to healthcare services: Current state and future trends of telehealth research. Internet Research. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-10-2021-0774

- Spall, S. (1998). Peer debriefing in qualitative research: Emerging operational models. Qualitative Inquiry, 4(2), 280–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780049800400208

- Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Sage.

- Striepe, M. (2021). Combining concept mapping with semi-structured interviews: Adding another dimension to the research process. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 44(5), 519–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2020.1841746

- Tajudeen, F. P., Bahar, N., Maw Pin, T., & Saedon, N. I. (2022). Mobile technologies and healthy ageing: A bibliometric analysis on publication trends and knowledge structure of mHealth research for older adults. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 38(2), 118–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2021.1926115

- Talmage, C. A., Knopf, R. C., Wu, T., Winkel, D., Mirchandani, P., & Candan, K. S. (2021). Decreasing loneliness and social disconnectedness among community-dwelling older adults: The potential of information and communication technologies and ride-hailing services. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 45(2), 89–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2020.1724584

- Tang, K. F., Teh, P. -L., Lim, W. M., & Lee, S. W. H. (2022). Perspectives on mobility among older adults living with different frailty and cognitive statuses. Journal of Transport & Health, 24, 101305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2021.101305

- Teh, P. L., Lim, W. M., Ahmed, P. K., Chan, A. H., Loo, J. M., Cheong, S. N., & Yap, W. J. (2017). Does power posing affect gerontechnology adoption among older adults? Behaviour & Information Technology, 36(1), 33–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2016.1175508

- Thamutharam, Y. N., Musthafa, F. N., Mustafa, M. B. P., & Tajudeen, F. P. (2021). Usability features to improve mobile apps acceptance among the senior citizens in Malaysia. ASM Science Journal, 16, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.32802/asmscj.2021.686

- Ventola, C. L. (2014). Mobile devices and apps for health care professionals: Uses and benefits. Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 39(5), 356–364.

- Wang, S., Bolling, K., Mao, W., Reichstadt, J., Jeste, D., Kim, H. C., & Nebeker, C. (2019). Technology to support aging in place: Older adults’ perspectives. Healthcare, 7(2), 184–217. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7020060

- Wildenbos, G. A., Peute, L., & Jaspers, M. (2018). Aging barriers influencing mobile health usability for older adults: A literature based framework (MOLD-US). International Journal of Medical Informatics, 114, 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2018.03.012

- Williams, M., & Moser, T. (2019). The art of coding and thematic exploration in qualitative research. International Management Review, 15(1), 45–55.

- Zainal, Z. (2007). Case study as a research method. Jurnal Kemanusiaan, 9, 1–6.

- Zong, X., Ingoglia, S., Lo Coco, A., Tan, J. P., Inguglia, C., Liga, F., & Cheah, C. S. (2023). Evaluating the filial behaviour scale across three cultural groups using exploratory structural equation modelling. International Journal of Psychology, 58(1), 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12880